Drawing

Newsletter

April 2005

© All rights reserved.

the

1-800-427-2468

TEETH: Drawing the Skull –

Part 3

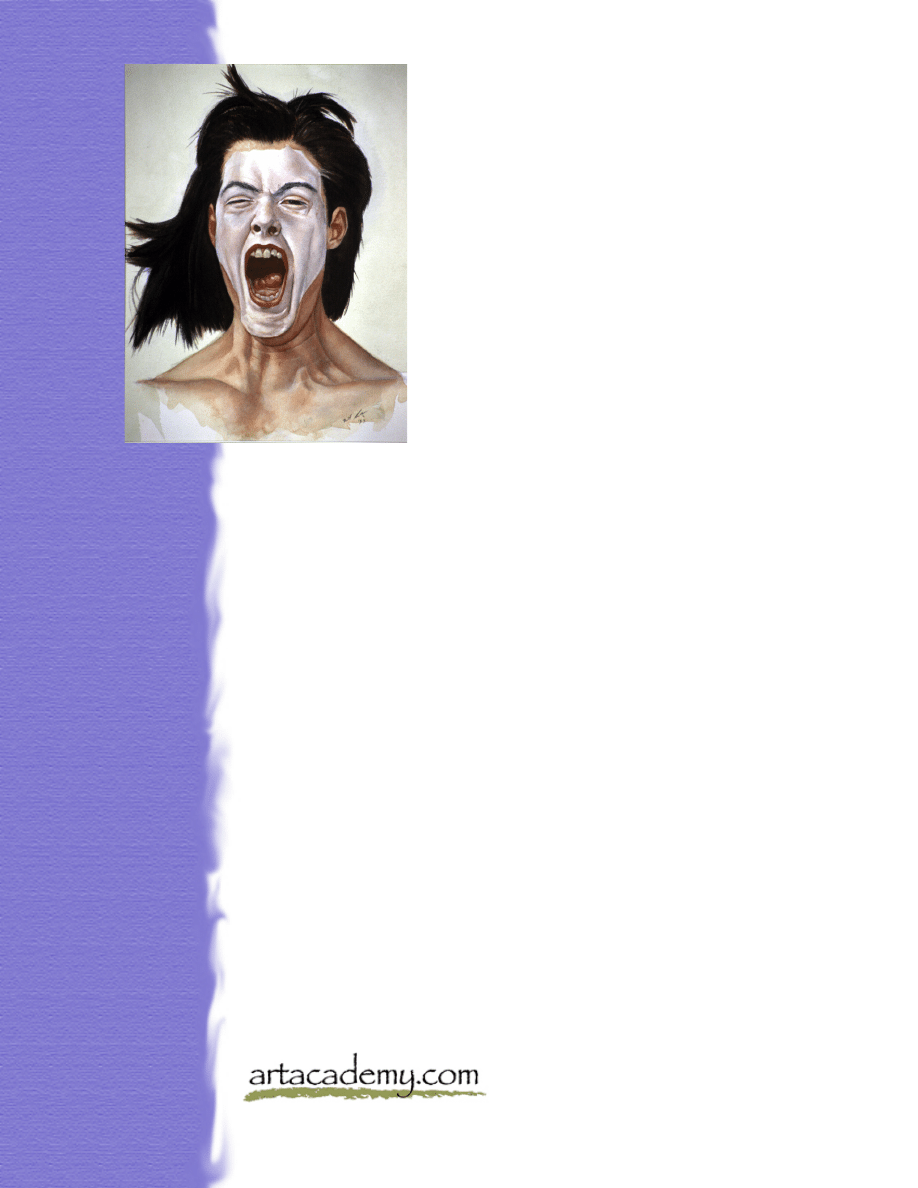

Most portraits are drawn with the mouth closed, yet rendering the face

with a slightly opened mouth allows for a greater range of expression –

from a relaxed intimacy to a raging howl. Whatever the expression, the

teeth should not be the primary focus for the viewer.

This requires two considerations: first, the teeth must be drawn correctly

and proportioned; this requires plumbing and aligning each tooth within

the facial arena. Poorly drawn teeth will draw unnecessary attention to

them. Second, teeth will invariably fall into shadow that is both cast from

the lips and the fact that the teeth are recessed into the mouth. In paint-

ing, teeth are never white. At their brightest they are a mother-of-pearl

gray. Subtlety and understatement are the keys to rendering teeth.

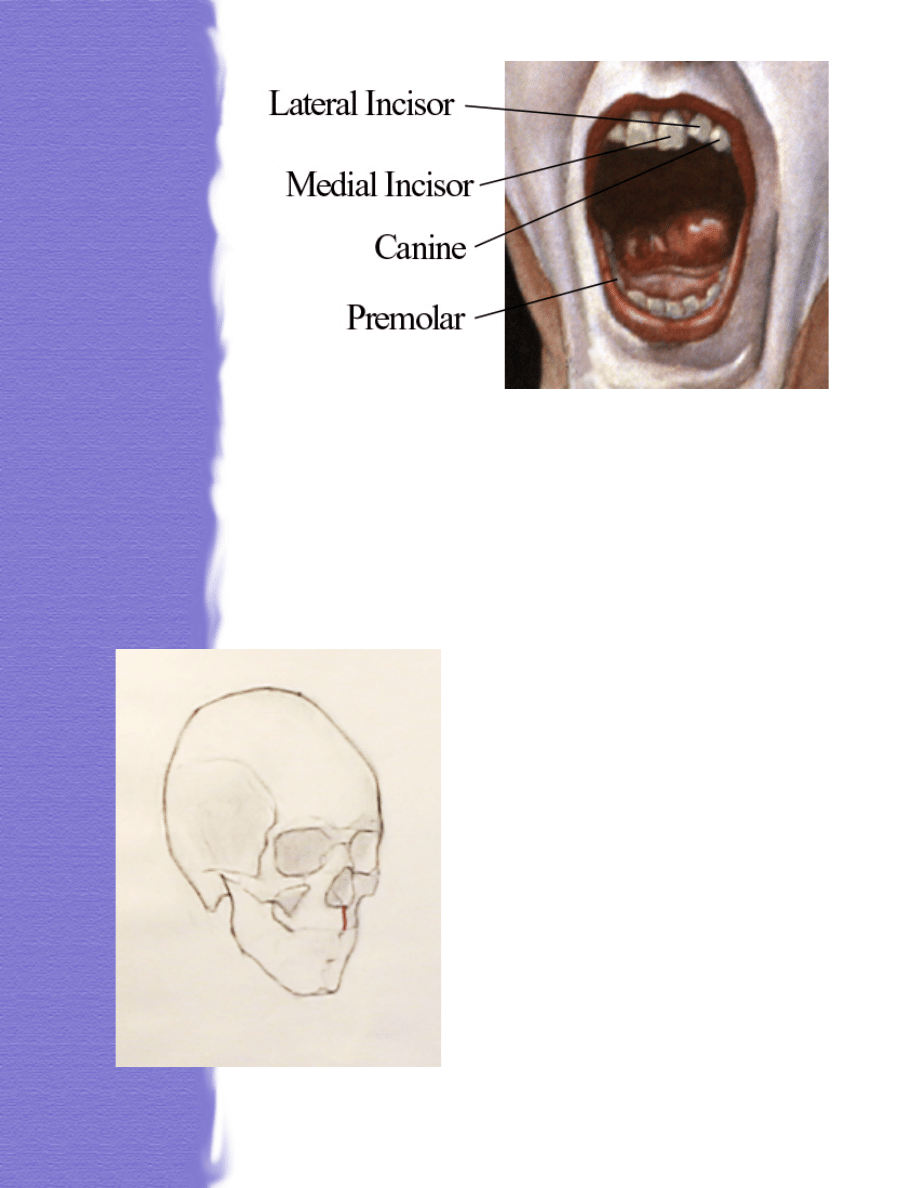

In most people the upper teeth close over the lower teeth: this is the ‘bite’.

With very few exceptions the only teeth visible in an open mouth will

be the incisors and canine teeth. The premolars will usually just peek

out from behind the cheeks. The top of the molars may subtly be seen

in the lower denture.

Natural teeth are hardly ever perfectly straight blocks. Each tooth will

have its own characteristics. The incisors are broad and chiseled –

designed to cut. Most people will have a slightly chipped medial incisor.

Look for a slightly askew lateral incisor, again,

it is a common element. The canine (eye tooth)

is generally the longest and is pointed; be care-

ful not to exaggerate it. Otherwise your portrait

will have a vampire-like effect.

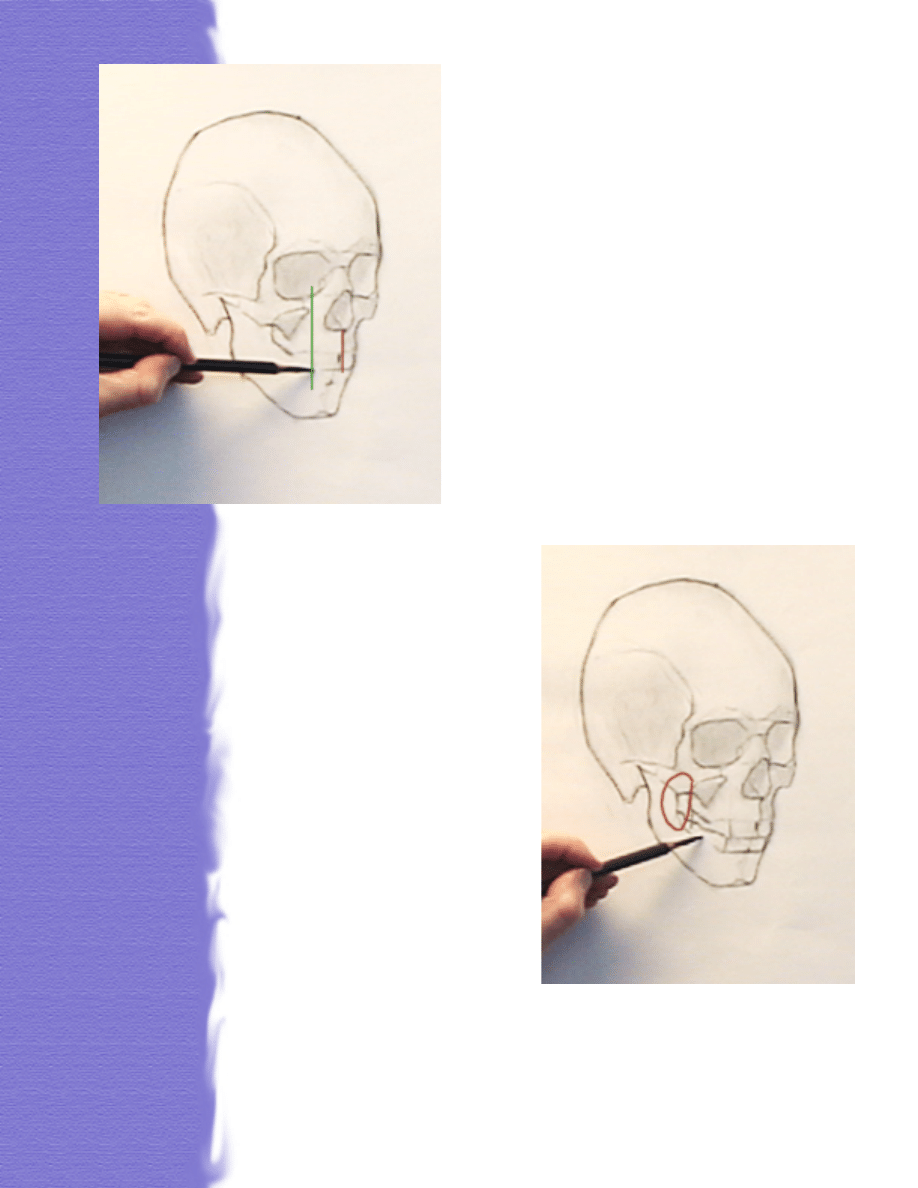

When drawing from your skull (which, if you

are serious about developing your drawing skills

you really should own one) the alveolar process

must first be ascertained. The alveolar process

is the horseshoe shaped ‘denture’ that contains

the sockets for the teeth. The small measure

(the red line) from the anterior nasal spine to

the alveolar process is too small to be measured.

It must felt. As I’ve said many times, this tactile

sensibility (the ‘felt’) is a learned skill requiring

both practice and knowledge.

Several elements must know be established

and fixed into place. First is the lower border

of the alveolar process (the lower teeth’s gum

line). Again, feel you way down from the

upper gum line and double check by feeling

your way up from the chin’s mental process.

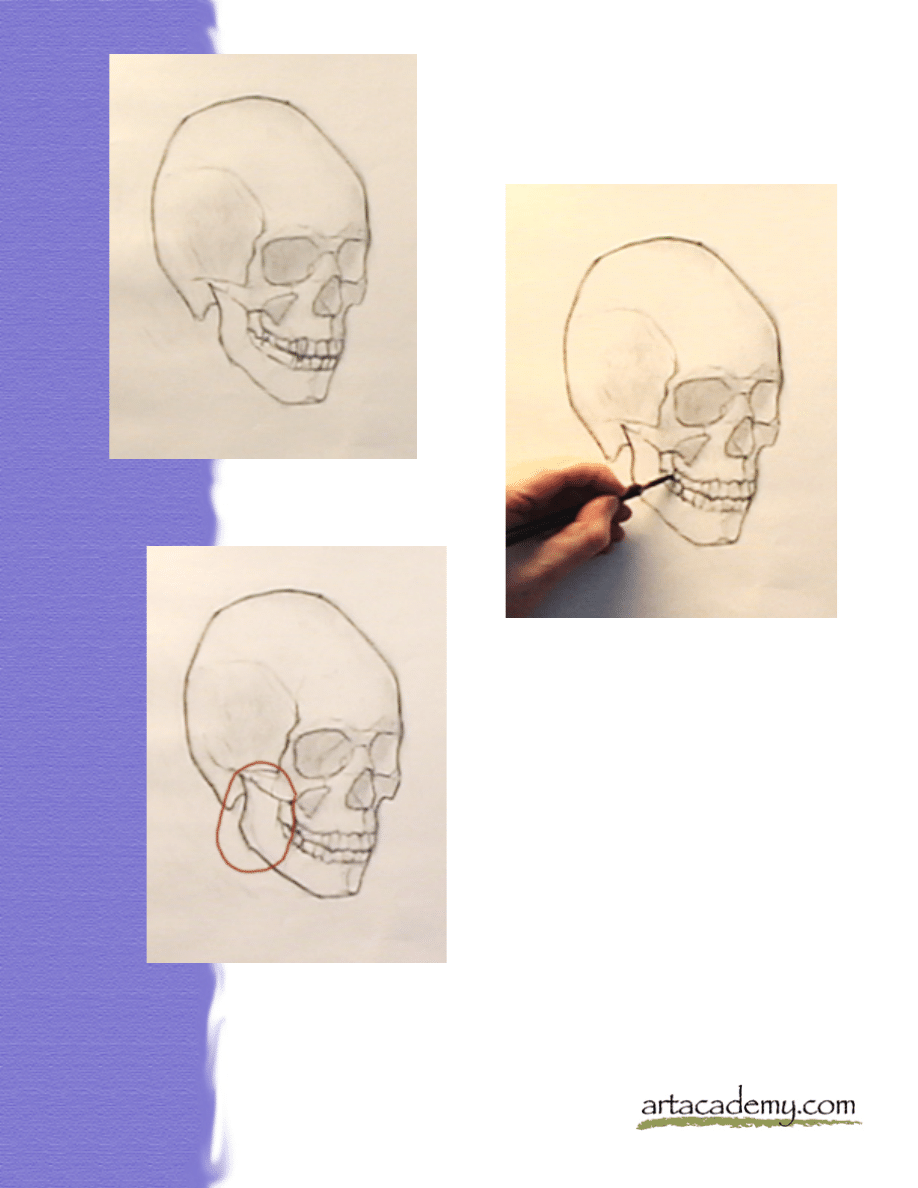

Second, mark the interstice where the upper

and lower medial incisive teeth meet. (The

upper teeth are usually larger than the lower.)

Third, the vertical division of the two front

medial incisors are placed by plumbing down

(the red line) from the anterior nasal spine.

Note that the vertical division of these two

front teeth are slightly to the left of the ante-

rior nasal spine. This is something to always

look for!

Fourth, the canine tooth is placed

by plumbing (green line) and

relating to either the zygomatic

process (it’s a bit to the right of it

here) or the eye socket. You are

looking for a viable landmark

that you believe is accurate.

As the teeth progress back to the

molars the interstice is always an

upwards angle until it meets the

coronoid process (circled in red).

You can almost feel the coronoid

process with you tongue – it is

just behind the wisdom teeth.

I think it best to first define the

teeth by carefully drawing the

interstice. Avoid the tooth-by-

tooth route.

Now is the time to sketch in the individual teeth

take note of each tooth’s individual character.

Avoid what I did – don’t exaggerate the canine.

But if you do it is easily fixed.

Now that I’ve corrected the errant canine I

softened the lines of the individual teeth so

that they are subtle and read pretty much as

teeth and not as a bunch of tooths (grammar

aside). I refined and slightly darkened the

interstice which emphasizes the bite.

Throughout the drawing of this skull a

small error managed to escape my detec-

tion. The ramus (circled in red) is off.

Totally. But it is easily fixed. The hard part

is detecting your errors. Usually it is a gut

feeling that something is amiss. The quick

way to check your drawing is by looking at

its reverse image in a mirror. It’s a brutal

method, but one that always illuminates the

errors of your drawing.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Drawing the Skull Part 1

Drawing the Skull Part 2

Making Robots With The Arduino part 1

Making Robots With The Arduino part 5

9 Ask?out the underlined part of the sentence

Battlestar Galactica Survivors of the Fleet Part 1

Nugent 5ed 2002 The Government and Politics in the EU part 1

7 Ask?out the underlined part of the sentence

Making Robots With The Arduino part 2

Burne Hogarth Drawing the Human head

Making Robots With The Arduino part 3

The Golden?lf Part 1

Making Robots With The Arduino part 1

Making Robots With The Arduino part 5

Howard, Robert E Kull The Skull of Silence

David Icke The New Mark Of The Beast Part 5

więcej podobnych podstron