Generation Y female

consumer decision-

making styles

Cathy Bakewell and

Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

Introduction

Generation theorists propose that as the

macro-environment changes, there are

concomitant and distinctive changes in

patterns of consumer behaviour (Strauss and

Howe, 1999). The recent acknowledgement

and exploration of a new sizable market

segment known as ‘‘Generation Y’’

(Newborne and Kerwin, 1999; American

Demographics, 1995) has been stimulated by a

recognition that they have been socialised into

consuming earlier than previous generations

(TRU, 1999) and have greater disposable

income (Tomkins, 1999). As consumer

attitudes, behaviour and skills are acquired via

socialisation agents such as family, peers,

school and the mass media (Moschis, 1987),

the proliferation of media choices including

television, the Internet and magazines has

resulted in greater diversity of product and

lifestyle choices for Generation Ys and

marketing and retailing to this cohort requires

a different approach (Phelps, 1999).

Generation Ys have been brought up in an

era where shopping is not regarded as a

simple act of purchasing. The proliferation of

retail and product choice has resulted in a

retail culture where acts of shopping have

taken on new entertainment and/or

experiential dimensions (Lehtonen and

Maenpaa, 1997). For example, Levi’s stores

in the USA now have D.J. Towers, ‘‘chill out’’

zones and moveable fixtures (Craik, 1999).

To this end, US-style shopping malls, and

their European equivalents, have become

essentially giant entertainment centres

bringing together a whole new combination of

leisure activities, shopping and social

encounters (Chaney, 1983). Consequently,

Generation Ys are likely to have developed a

different shopping style compared with

previous generations. Despite this, there have

been very few academic studies, which focus

on shopping styles of Generation Y

consumers and offer guidelines to marketers

and retailers on how these consumers make

their choices. Previous work on shopper types

(e.g. Stephenson and Willett, 1969; Moschis,

1976; Darden and Ashton, 1975; Westbrook

and Black, 1985; Bellenger and Korgaonker,

1980) has not attempted to look at specific

age cohorts, yet the importance of this group’s

differences suggested a need to investigate

their decision-making styles. The present

study examines Generation Y consumers’

The authors

Cathy Bakewell is a Lecturer in Marketing at

Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK.

Vincent-Wayne Mitchell is Professor of Marketing

at Manchester School of Management, UMIST,

Manchester, UK.

Keywords

Consumer behaviour, Customer profiling, Women,

Segmentation, United Kingdom

Abstract

Since environmental factors have influenced Generation Y

shoppers (those born after 1977) to make them different

from older groups, this study examines the decision

making of Adult Female Generation Y consumers using

Sproles and Kendall’s (1986) Consumer Styles Inventory

(CSI). The study uses the CSI as a basis for segmenting

Generation Y consumers in to five meaningful and distinct

decision-making groups, namely: ``recreational quality

seekers’’, ``recreational discount seekers’’, ``trend setting

loyals’’, ``shopping and fashion uninterested’’ and

``confused time/money conserving’’. Implications for

retailers and marketing practitioners targeting Generation

Y consumers are discussed.

Electronic access

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is

available at

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is

available at

http://www.emeraldinsight.com/0959-0552.htm

95

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . pp. 95-106

# MCB UP Limited . ISSN 0959-0552

DOI 10.1108/09590550310461994

shopping styles using Sproles and Kendall’s

Consumer Styles Inventory (1986). Although

Sproles and Kendall’s original studies were

designed to profile individuals on the traits

they possessed (Sproles, 1985; Sproles and

Kendall, 1986), the next logical step is to

cluster individuals on their trait scores to

identify groups of Generation Y shoppers.

This linkage of decision-making traits to

segments has seldom been done before,

despite the usefulness of a typology of

Generation Y shoppers for retailers to gain

the benefits of tailoring marketing

programmes to specific emerging segments

(Pine et al., 1995).

Consumer decision-making styles,

shopping typologies and gender

The underlying determinations as to how and

why people shop has been a topic of study for

many years, with early work on shopping

orientations developing a typology of

shopping styles from a sample of 124 female

department store shoppers (Stone, 1954).

Although Darden and Reynolds (1971) found

support for Stone’s shopping orientations,

other researchers have found different

typologies by examining slightly different

aspects of shopping (Stephenson and Willett,

1969; Moschis, 1976; Darden and Ashton,

1975; Westbrook and Black, 1985; Bellenger

and Korgaonker, 1980; McDonald, 1993).

The diverse array of shopper types found is

perhaps not surprising in view of the diversity

of research approaches and contexts[1].

However, these studies have been successful

in demonstrating that some shoppers display

consistent shopping orientations that can be

diametrically opposed, e.g. the ‘‘recreational’’

shopper versus the ‘‘apathetic’’ shopper, but

they do not explicitly address the question of

how to measure the consumer decision-

making styles that lead to these divisions.

Work by Sproles (1985) and Sproles and

Kendall (1986) developed the Consumer

Styles Inventory (CSI) which represented the

first systematic attempt to create a robust

methodology for measuring shopping

orientations and behaviour.

Sproles and Kendall (1986, p. 267) define

consumer decision-making style as, ‘‘a mental

orientation characterising a consumer’s

approach to making choices’’, and propose

that consumers adopt a shopping

‘‘personality’’ that is relatively fixed and

predictable in much the same way as

psychologists view personality in its broadest

sense. The CSI was developed and validated

from a sample of 482 US high-school

students, late Generation X consumers, who

were asked about their decision-making style

for personal products (i.e. clothing, cosmetics

and hairdryers). In total 40 items pertaining

to affective and cognitive orientations in

decision making are the basis from which

eight potential styles or traits affecting

behaviour can be identified (see Table I).

Although some theorists propose that

shopping is both of interest and performed

equally by men and women (see for example,

Otnes and McGrath, 2000), many studies of

shopping behaviour have employed all-female

samples (e.g. Stone, 1954). This practice

reflects a widely held view that gender is

fundamental to understanding and predicting

shopping behaviour. One study that focussed

on gender differences, concluded that women

hold diametrically opposed values regarding

‘‘effective’’ shopping compared with men

(Falk and Campbell, 1997). In essence, these

differences manifested in terms of the time

spent browsing and researching choices.

Women enjoyed the process and were happy

to spend considerable time and mental

energy, while men sought to buy quickly

and avoid it as much as possible. Other

studies have confirmed the ‘‘shopping as

leisure’’ dimension for women (e.g.

Jansen-Verbeke, 1987) and that women do

shopper for longer and are more involved

than men (Dholakia, 1999).

Generation Y and their consumption

habits

Cohort generations are argued to share a

common and distinct social character shaped

by their experiences through time (Schewe

and Noble, 2000). Generation Y are the

children of the ‘‘baby boomers’’ generation

or ‘‘Generation X’’ (Herbig et al., 1993)[2].

In the USA alone, there are approximately

60 million Generation Ys (Newborne and

Kerwin, 1999) and in the UK the number of

15-21 year olds is growing (Baker, 2000).

When Generation Ys come of age they will

have experienced unprecedented purchasing

power (for example, US teenagers spend

$97.3 billion annually) of which two-thirds

96

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

goes on clothing and almost 10 per cent on

personal care (Ebenkamp, 1999) and will

have more involved in family decision

making than other generations (Phelps,

1999).

Being such a nascent potential market

segment, there are no empirical studies that

specifically focus on Generation Ys.

However, it is likely that Generation Ys will

hold differing attitudes/values/behaviour

regarding shopping vis-aÁ-vis other cohorts,

because of technological/socio-cultural/

economic and retail changes during the last

10 to 20 years. Childhood and adolescence

appear to be crucial periods for acquiring

enduring consumption related orientations

(Moschis and Cox, 1989) and Table II

provides an overview of perspectives

regarding environmental change and their

likely impact on Generation X and Ys

(Herbig et al., 1993; Schor, 1998; Roberts

and Manolis, 2000; Ger and Belk, 1996;

Roberts, 1998; Damon, 1988; Wolburg and

Pokryvczynski, 2001).

‘‘To have is to be’’; the need for material

goods and the rise of the perfectionist

shopper

Each generation it seems becomes more

conspicuous in its consumption compared

with previous cohorts (Herbig et al., 1993) and

it is unlikely that Generation Ys are any

different. Moschis and Churchill (1978) report

a positive association between television

viewing and materialism among adolescents

and viewing in Generation Y households is

around seven hours a day (Nielsen, 1995)

making them one of the most television

acculturated generations ever. Schrum et al.

(1991) propose that television programmes

convey a wealth of information with respect to

consumption and that as television viewing

increases, an individual’s consumption

perceptions more closely reflects the ‘‘reality’’

of the television world. Commonly, the

characters and objects portrayed in television

are associated with an affluent lifestyle (e.g.

O’Guinn and Shrum, 1997; Wells and

Anderson, 1996) and this has been claimed to

be on the increase since the 1980s (Schor,

1998). O’Guinn et al. (1985) argue that

contemporary television portrays and therefore

reinforces the belief that material goods and

opulence are a good thing.

In addition to television, Generation Ys have

been acculturated into a materialistic and

consumer culture more so than other

generations as a result of technological

innovations. Ger and Belk (1996) note how

the proliferation of communication

technologies, mass media, international travel

and multinational marketing campaigns has

played a major part in promulgating the

‘‘American Dream’’, i.e. the notion that

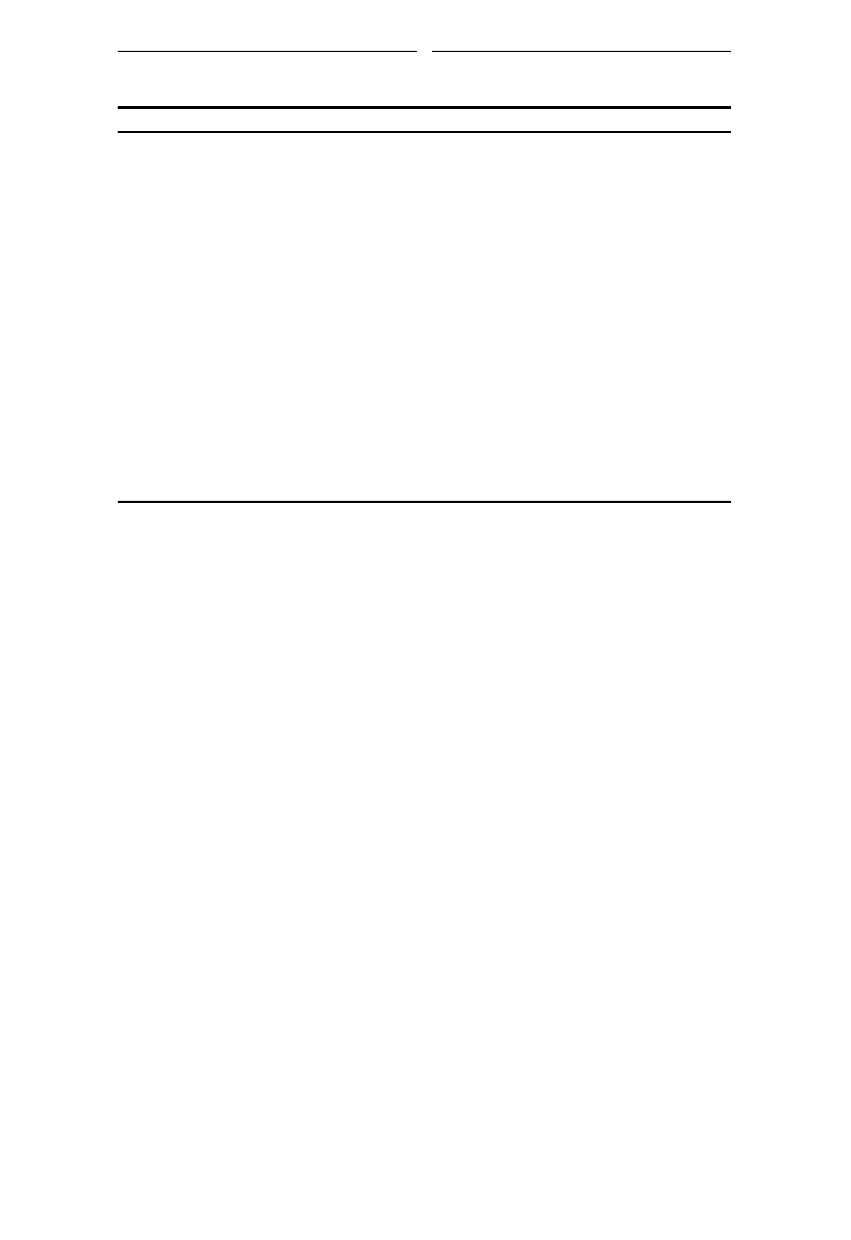

Table I Characteristics of eight consumer decision-making styles

Decision style

1. Price/value consciousness: decision style that is concerned with getting lower prices. The presence of this trait

means that the consumer is conscious of sale prices and aims to get the best value for their money

2. Perfectionism: decision style that is concerned with quality. Consumers with this decision-making style will not

compromise with products classified as ``good enough’’

3. Brand consciousness: decision style that is concerned with getting expensive, well-known brands. Consumers

with this style believe that the higher the price of a product, the better the quality. These consumers also prefer

best selling advertised brands

4. Novelty/fashion consciousness: decision style for seeking out new things. This trait reflects a liking of innovative

products and a motivation to keep up to date with new styles and fashion trends

5. Habitual/brand-loyal: decision style for shopping at the same stores and tendency to buy the same brands each time

6. Recreational shopping consciousness: decision style that views shopping as being enjoyable per se. Shoppers

with this trait enjoy the stimulation of looking for and choosing products

7. Impulsive/careless: decision style that describes a shopper who does not plan their shopping and appears

unconcerned with how much he or she spends. Consumers with this style can regret their decisions later

8. Confused by overchoice: decision style that reflects a lack of confidence and an inability to manage the number

of choices available. Consumers with this trait experience information overload

Source: Sproles and Kendall (1986)

97

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

material things and opulence are good and

desirable. These developments may help to

explain the fact that there is a steady increase

through the generations of the importance of

having lots of money (Mitchell, 1995). It has

also been found that younger generations are

more likely to associate higher prices per se with

improved quality and worth, and are more

motivated to ‘‘trade up’’ compared with older

generations (Roberts and Manolis, 2000).

In part, the ability to buy more expensive

lines and brands can arguably be attributed

inter alia to more recent environmental

factors, namely, the loosening of credit

restrictions and the rise of designer labels.

Since the 1980s, there has been a steady

increase in the availability of credit cards

marketed to young adults (Kara et al., 1994)

and retailers have introduced their own store

cards and interest-free periods. Moreover, the

UK Government invites indebtedness

through the availability of student loans and

Generation Ys have been socialised in to a

world where debt is used rather than savings

to finance consumption (Ritzer, 1995). It is

known that access to credit is a contributory

factor in the practice of trading-up and

overspending (Roberts and Manolis, 2000).

Generation Ys have been brought up with

designer labels such as Donna Karan and

Armani, which at one time would have been

associated with perhaps 1-5 per cent of

potential consumers, but since the 1990s

there has been a steady branching out into the

lower-priced designer label segments through

retail outlets such as DKNY and Emporio

Armani. Discount designer label outlets, such

as TK Max and Matalan, as well as

independent factory villages, are likely to have

shaped some Generation Ys practice of

upscale emulation. This leads to our first

proposition that: many Generation Y

shoppers are likely to show a materialistic/

opulent shopping style.

‘‘Born to shop’’; Generation Y, the

ultimate Homo Consumeriscus?

A number of authors have commented on the

use of shopping as a form of recreation (e.g.

Hirschmann and Holbrook, 1982; Bloch et al.,

1991) and it would seem that for many,

shopping is their principal and most enjoyable

hobby. Unlike previous age groups, Generation

Ys have been acculturated into an environment

that provides more opportunities and reasons to

shop than ever before. Within the retailing

environment there has been the introduction of

Sunday shopping and opening hours more

similar to the USA, i.e. post 6 p.m. closing.

Additionally, television, the Internet as well as

the more traditional catalogue based shopping

forms offer additional consumption

opportunities. Many Generation Ys have been

brought up in households where both parents

work and have learnt to shop and make brand

decisions sooner compared with previous

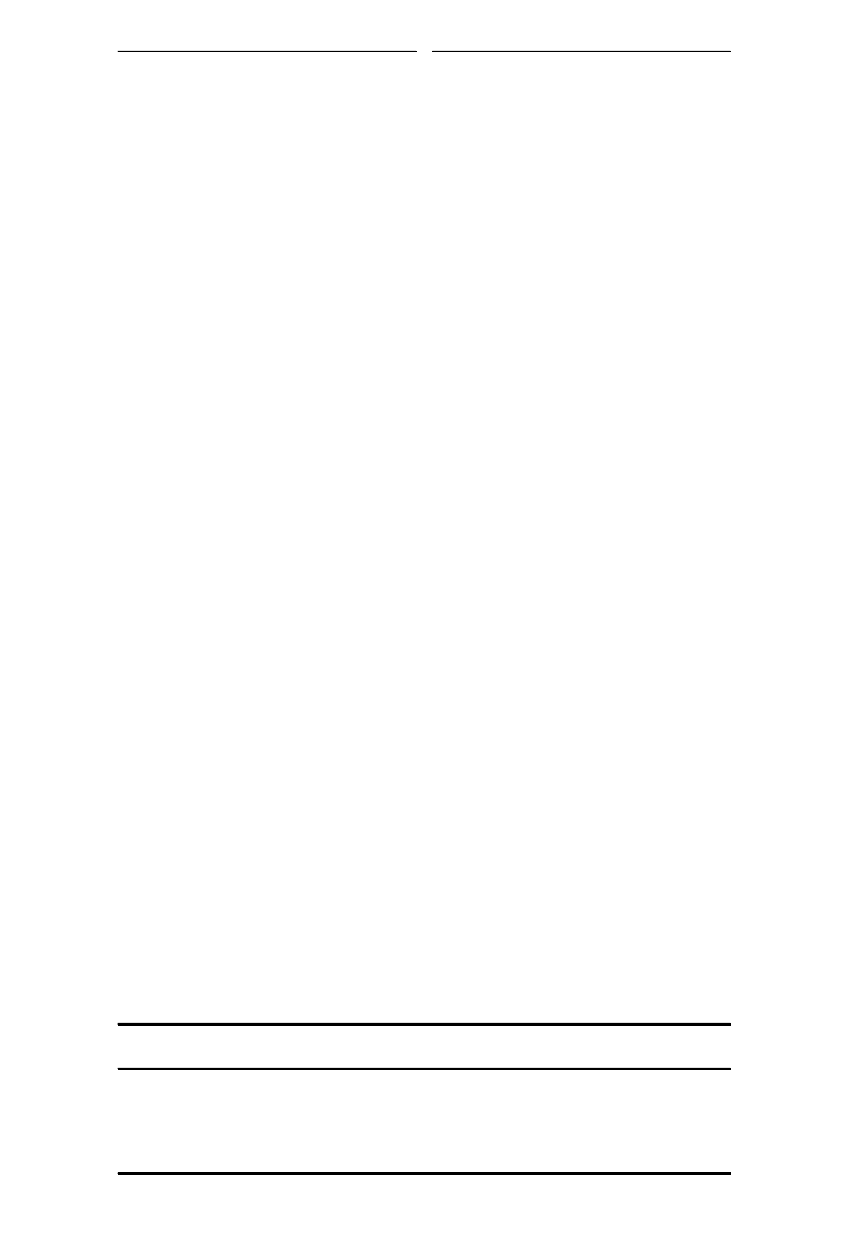

Table II Comparison of childhood environmental influences on Generation X and Ys

UK Generation X

UK Generation Y

Fewer and conventional shopping channels and restricted

shopping hours

Many shopping channels and unrestricted shopping

hours. Socialised in to newer retailing formats such as

factory outlets, designer discount villages, Internet

Environment of restricted credit

Environment of unrestricted and creative credit

opportunities e.g. interest free periods, deferred payments,

cash back, multiple credit and store cards, short-term loans

Acculturated into an environment of less materialism/

income inequality, social class judged by what a person

does

Postmodern culture where goods and services rather than

occupation increasingly important in defining social

standing. Acculturated by television/magazines in to

revering and envying opulent lifestyles e.g. Hello

Magazine, Dynasty, Beverly Hills 90210

Receive advertising and marketing information from

traditional media

Advertising and marketing information from ever increasing

sources e.g. cable/digital TV, mobile phones, e-commerce

Fewer gender-role blurrings, i.e. females interested in and

shop for personal goods and clothing, males interested in

and shop for cars, home maintenance goods

More gender-role blurrings, i.e. females buying cars/

home-maintenance products, males buying clothes and

personal care goods

More likely to have grown up in traditional family unit

with greater socialisation from parents

More likely to grow up in non-traditional family units

with greater socialisation from peers

98

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

generations. For example, more than half of

teenage girls and more than one-third of

teenage boys do some food shopping for their

family (TRU, 1999). Likewise Generation Y

consumers have been socialised into shopping

as a form of leisure. Indeed, the average US

female teenager spends 11 hours per week at

shopping malls (Herbig et al., 1993) and US

teenage mall shoppers make more annual trips

(76 visits compared with 54) and spend more

time in the mall per trip (90 minutes versus 76)

compared with other shoppers. They also go to

browse rather than specifically to purchase

(International Council of Shopping Centres,

1997). In part, this is attributed to the high

levels of single parent households and/or

working mothers (Newborne and Kerwin,

1999; Phelps, 1999). This leads to our second

proposition, namely: many Generation Ys will

show a recreational shopping style.

Proliferation of choice, postmodernism,

fragmentation and chaos; are

Generation Ys likely to be more

confused?

Generation Y has been subjected to more

targeted marketing programmes and has been

brought up with more retailing formats and

product/brand choices compared with

previous generations (TRU, 1999). The rise

of the phenomenon known as ‘‘smart

shopping’’, i.e. ‘‘a tendency for consumers to

invest considerable time and effort in to

seeking and utilising promotion-related

information to achieve savings’’ (Mano and

Elliot, 1997, p. 504), may be a new shopping

style amongst Generation Ys that has been

hitherto missed. For example, Saatchi and

Saatchi (1999) found that digital media have

given Generation Y unprecedented means to

connect with each other and the world;

allowing this generation to explore more the

importance and power of knowledge. Almost

two-thirds of US Generation Ys with Internet

access buy or research products on-line

(Cravatta, 1997) and by 2002, it is estimated

that the e-commerce dollar impact of

Generation Y will be $1.3 billion and that

there will be 38.5 million Internet users

(Cravatta, 1997; Heckman, 1999).

Conversely, if we are living in postmodern

society[3], customer confusion and other

shopping concomitants such as apathy and poor

decision making would seem likely phenomena

to observe. Generation Ys have been brought

up with unprecedented choice amongst most

consumer goods and services (Quelch and

Kenny, 1994), e.g. 75 different kinds of

toothbrush and 240 shampoos in Boots the

Chemist and 347 separate varieties of Nike

trainer (Fielding, 1994). Other sources of

confusion identified include: the introduction of

more brand me-too products, and uncertainty

about product environmental and health

claims. This leads to our third proposition,

namely that: many Generation Ys will show

customer confusion and/or behaviours to cope

with over-choice, e.g. apathy and brand loyalty.

Methodology

The instrument

Despite the CSI being developed in an English

speaking country, a number of alterations were

needed to the question wording in order to aid

the comprehension of UK respondents. First, in

Sproles and Kendall’s original format, the verb

often appears at the end of sentences, e.g. ‘‘the

more expensive brands are usually my choice’’.

For the purpose of this study, the statements

were re-phrased to reflect the style of English

more commonly used in the UK, i.e. ‘‘I usually

choose the more expensive brands’’. Second,

the original inventory contains ambiguous

words such as ‘‘best’’ and ‘‘perfect’’. This

creates problems because it is unclear whether

‘‘best’’ refers to: price, image, durability or

suitability. In order to reduce the potential for

measurement error, some items were

rephrased, e.g. ‘‘A product doesn’t have to be

perfect, or the best, to satisfy me’’ became, ‘‘A

product doesn’t have to be exactly what I want,

or the best, to satisfy me’’. In total, 38 CSI

items were included and rated on a five-point

agree-disagree Likert scale. The items were

placed in two different orders so as to minimise

order effects and items expected to load onto a

single factor were separated.

The sample

In general, generation cohorts can be described

as, ‘‘matures’’ (1909-1945) age

55-91; ‘‘baby boomers’’ (1946-1964) age

36-54; ‘‘Generation X (1965-1976) age 24-35

and ‘‘adult female Generation Y’’ (1977-1994)

age 6-23. The questionnaire was administered

to a non-probability sample of female

undergraduate students aged between 18 and

22, which resulted in 244 usable responses. The

99

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

emphasis on the top third of the adult female

Generation Y bracket was due to: their greater

experience of being adult female Generation Y;

their increased purchasing power; their relative

freedom from potential parental intervention in

exercising their shopping style and their greater

appropriateness for the questionnaire

methodology employed, as well as consistency

with most previous studies e.g. Sproles and

Kendal (1986), where a student sample was

used because they were seen as benefiting from

relative homogeneity and reduced the potential

for random errors compared with a sample

from the general public (Calder et al., 1981).

Although demographic and socio-psychological

(e.g. status consciousness, conservatism,

dogmatism) criticisms of student populations’

representativeness have been made, these

criticisms are inappropriate given this cohort is

the target population for the study. The sample

were asked to complete the questionnaire with

reference to the purchasing of ‘‘personal goods’’

i.e. clothes, cosmetics, footwear and jewellery.

Analysis

Cluster analysis was conducted in order to

identify decision-making groups. Following

Punj and Stewart’s (1983) recommendation,

Ward’s method of analysis was used and the

results suggested a six-cluster solution.

Discriminant analysis was then carried out to

identify the discriminating variables between

these clusters. The chi-squared statistics were

significant and the canonical correlations for

all the functions were high (see Table III) and

the classification matrix showed 97.26 per cent

of cases were correctly classified in the analysis

sample (holdout sample, 54.79 per cent).

Results

Five segments were found (see Table IV):

(1) Recreational quality seekers (33 per cent)

form the largest group of shoppers and

are characterised by the traits;

‘‘recreational/hedonistic’’,

‘‘perfectionism’’ and ‘‘brand

consciousness’’. These shoppers enjoy

shopping and exert extra effort in order to

get quality products. They show a degree

of brand loyalty and will pay extra for

brand names. This group is not attracted

to lower prices or discounts and they

disagree with the statement, ‘‘I buy as

much as possible at sale price’’.

(2) Recreational discount seekers (16 per cent) are

associated with the ‘‘bargain seeking’’ trait,

as they agree with the item, ‘‘I buy as

much as possible at sale price’’. This group

also displays the trait of ‘‘fashion/novelty

consciousness’’. However, in spite of

quality concerns, this group differs from

the ‘‘recreational quality seekers’’ in that

they are less ‘‘brand conscious’’ and more

‘‘price/value conscious’’.

(3) Shopping and fashion uninterested (16 per

cent) are confident shoppers who are

associated with the traits of ‘‘time energy

conserving’’ and ‘‘price/value

consciousness’’ and the statements, ‘‘ I

normally shop quickly, buying the first

product or brand that seems good enough’’

and, ‘‘I usually buy the lower-price

products’’. Shoppers belonging to this

cluster do not find shopping pleasurable

and they are not associated with the

‘‘novelty/fashion consciousness’’ trait as

they disagreed with three of the statements

e.g. ‘‘Fashionable, attractive styling is very

important to me’’, which are associated

with this trait.

(4) Trend setting loyals (14 per cent) are

fashion and style conscious. They agree

with the statement, ‘‘I keep my wardrobe

up to date with changing fashions’’. They

also have a tendency to visit the same

stores and buy the same brands. Shoppers

in this group, however, are not

perfectionists and they disagreed with the

statement, ‘‘The higher the price of the

product, the better its quality’’. Instead,

Table III Canonical discrimination functions for Generation Y consumer decision-making clusters

Function

Eigenvalue

Percentage

of variance

Cumulative

percent

Canonical

correlations Chi-squared

Degrees of

freedom

Significance

325.74

104

0.00

1

4.65

34.70

34.70

0.91

227.93

75

0.00

2

3.96

29.54

64.24

0.9

137.5

48

0.00

3

2.74

20.46

84.70

0.86

62.98

23

0.00

4

2.04

15.30

100.00

0.82

100

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

Table IV Summary of Generation Y adult female consumer decision-making segments

Cluster 1: Recreational, quality seekers (33 per cent)

Agree:

I enjoy shopping, just for fun

Disagree:

Shopping is not a pleasant activity to me

Once I find a product I like, I buy it regularly

I really don’t give my purchases much thought or care

In general, I try to get the best overall quality

I usually buy the lower price products

I have favourite brands I buy every time

I buy as much as possible at sale price

Fashionable, attractive styling is very important to me

I make a special effort to choose the very best quality products

I usually buy the more expensive brands

I usually buy well-known brands

I prefer buying the best selling brands

Cluster 2: Recreational discount seekers (16 per cent)

Agree:

Shopping is very enjoyable to me

Disagree:

Shopping is not a pleasant activity to me

It’s fun to buy something new and exciting

I normally shop quickly, buying the first product or brand I find that

seems good enough

I look very carefully to find the best value for money

I spend little time deciding on the products and brands I buy

I buy as much as possible at sale prices

Sometimes it’s hard to decide in which stores to shop

To get variety, I shop in different stores and buy different brands

The higher the price of the product, the better its quality

A product doesn’t have to be exactly what I want, or the best on the

market to satisfy me

The most advertised brands are usually good choices

I should spend more time deciding on the products and brands I buy

Cluster 3: Shopping and fashion uninterested (16 per cent)

Agree:

I go to the same stores each time I shop

Disagree:

I get confused by all the information on different products

Sometimes it is hard to decide in which stores to shop

I usually have at least one outfit of the newest style

I usually buy the lower-price products

I keep my wardrobe up to date with the changing fashions

I normally shop quickly, buying the first product or brand I find that seems

good enough

The most advertised brands are usually good choices

Shopping is not a pleasant activity to me

There are so many brands to choose from, that I often feel confused

Shopping in different stores is a waste of time

Shopping is very enjoyable to me

I enjoy shopping, just for fun

To get variety, I shop in different stores and buy different brands

Fashionable, attractive styling is very important to me

Cluster 4: Trend-setting loyals (14 per cent)

Agree:

I have favourite brands I buy every time

Disagree:

The higher the price of the product, the better its quality

I keep my wardrobe up to date with the changing fashions

Shopping in different stores is a waste of time

I usually have at least one outfit of the newest style

I prefer buying the best selling brands

I go to the same stores each time I shop

The most advertised brands are usually good choices

I usually buy the lower price products

A product does not have to be exactly what I want, or the best on the

market to satisfy me

Sometimes it is hard to decide in which stores to shop

The more I learn about products, the harder it seems to choose the best

There are so many brands to choose from, that I often feel confused

Cluster 5: Confused, time/money conserving (21 per cent)

Agree:

I carefully watch how much I spend

Disagree:

I usually buy the more expensive brands

The more I learn about products, the harder it seems to choose the best

I make a special effort to choose the very best quality products

I spend little time deciding on the products and brands I buy

Good quality department and speciality stores offer the best products

I get confused by all the information on different products

I usually buy well-known brands

101

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

they are associated with ‘‘price/value

consciousness’’ and do not believe that

brands have to be well known to be a

good choice. This group was also

associated with the ‘‘confused by

over-choice’’ trait.

(5) Confused time/money conserving

(21 per cent) shoppers are associated with

the ‘‘confused by overchoice’’ and ‘‘price/

value consciousness’’ traits. They agreed

that, ‘‘I get confused by all the

information on different products’’ and,

‘‘I carefully watch how much I spend’’.

Y shoppers in this cluster are not drawn

to the more prestigious and higher priced

brands/stores, preferring instead lower

prices to higher quality. They also spend

little time deciding between options.

Discussion

Support for our first proposition, that ‘‘many

Generation Y shoppers are likely to show a

materialistic/opulent shopping style’’ was

found in so far as almost one in three

belonged to the ‘‘recreational quality seekers’’

segment. Furthermore, the ‘‘recreational

discount seekers’’ (16 per cent) also professed

to believe that ‘‘the higher the price of the

product, the better its quality’’. This finding

was unsurprising given that adult female

Generation Ys have been acculturated by

media that portray affluent and opulent

lifestyles. Likewise, as generations become

more accustomed to intensive and

sophisticated marketing practices, it is not

surprising that ‘‘quality’ is sought after. The

fact that these shopping types seem divided

into either straight forward ‘‘quality seekers’’

or those pursuing quality through price

reductions suggests that the identification of

the ‘‘economic’’ (e.g. Stone, 1954) or ‘‘value’’

shopper (e.g. McDonald, 1993) is more

complicated for adult female Generation Ys.

In this regard, the ‘‘recreational discount

seekers’’ may be further evidence of the

‘‘smart shopper’’ phenomenon.

Support for our second proposition, that,

‘‘many Generation Y shoppers will show a

recreational shopping style’’ was even greater in

so far as almost half the sample belonged to the

segments ‘‘recreational quality seekers’’ and

‘‘recreational discount seekers’’. This finding

might indicate that adult female Generation Ys

enjoy shopping more than previous age cohorts

and/or that they are responding appropriately

to the efforts of retailers to provide more

‘‘entertaining’’ shopping experiences (Jones,

1999). However, the predominance of this trait

might also be attributed to the fact that adult

female Generation Ys have been socialised into

a shopping culture at an earlier age (TRU,

1999). Others propose that the willingness and

enjoyment associated with shopping is an

inevitable consequence of a more secular,

uncertain and less family-oriented environment

(Minsky, 2000; Mellon, 1995). Fischer and

Gainer (1991) see shopping as being an

integral part of the social construction of

women’s identity and a means through which

they can experience of ‘‘flow’’ (Csiksentmihalyi,

1975)[4]. Falk and Campbell (1997) see

shopping as being as important to women’s

lives, in terms of its capacity to create a sense of

self and the ownership of space, just as the

world of work has been historically to men.

Furthermore, in an increasingly consumerist

society in which possessions are perceived as

being inexorably linked to self-identity and

status (Belk, 1985), it is perhaps unsurprising

that many shoppers find even mundane psychic

acts such as looking in shop windows

significant in their psychic lives (Bocock,

1993). Interestingly, the identification of

‘‘recreational discount seekers’’ may be further

evidence of the ‘‘smart shopper’’ phenomenon

and suggests the schism between utilitarian and

hedonic shopping (Hirschman and Holbrook,

1982) is outdated.

Support for our final proposition that

‘‘many Generation Ys will show customer

confusion and/or behaviours to cope with

over-choice, e.g. apathy, brand loyalty’’ was in

evidence as almost one in five adult female

Generation Ys adopt a shopping style that is

confused (confused time/money conserving).

According to Mitchell and Papavassilliou

(1999) one of the principal reasons why

customers may be more confused than ever

relates to attempts by marketing practitioners

to meet consumer needs in an increasingly

competitive world. The combined traits of

confusion and time/money conserving has not

been established in previous shopping

typologies and may be a result of the amount

of products, channels and information that

adult female Generation Y are exposed to and

must process.

McDonald (1993) found both ‘‘loyal’’,

‘‘fashionable’’ and ‘‘value’’ segments in his

typology of mail-order shoppers. However,

102

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

our study shows that almost one in six adult

female Generation Ys (i.e. ‘‘trend setting

loyals’’) have elements of all three traits in

their shopping behaviour. Adult female

Generation Ys are known to be interested in

fashion (Phillips, 1997), plus they have a

desire to bolster their self-esteem through

having a ‘‘cool’’ look (Phelps, 1999).

However, higher loyalty can also be an

effective means for overcoming confusion.

Finally, a frequent finding in prior research

is the apathetic shopper, for whom shopping

held no intrinsic interest and constituted a

burden at best (e.g. Stone, 1954; Bellenger

and Korgaonker, 1980; Westbrook and Black,

1985) and this research confirms the adult

female Generation Y equivalent in the form of

the ‘‘shopping and fashion uninterested’

segment. This result could be attributed to

the degree of marketing cynicism that has

been seen with adult female Generation Ys

(Zollo, 1999; Newborne and Kerwin, 1999),

since they have been the target of more

marketing programmes and product choices

than any generation before them and almost

one in six adult female Generation Ys practice

this form of market ‘‘resistance’’. Shopping

apathy may also be the extreme end point

stemming from confusion.

Conclusions and implications

One of the key findings of this study is the

confirmation of shopping as a form of leisure

and enjoyment for adult female Generation Ys.

‘‘recreational quality seekers’’ and ‘‘recreational

discount seekers’’ enjoy shopping therefore

retailers should consider ways to improve the

leisure experience for this group. Some retailers

have begun to experiment with cafes and

beauty therapy experiences, e.g. nail

extensions, and our findings would suggest that

this is a prescient move. Retailers should

continue to look for ways in which they can

induce feelings of fun and leisure for

Generation Ys. Jones (1999) suggests that

there are four resources at the disposal of

retailers for producing entertaining shopping

experiences i.e. retail prices, selection, store

environment and sales people. Retailers

targeting the ‘‘recreational quality seekers’’

should supply a selection of prestigious brands

and emphasise the quality and fashion aspects

of their merchandise. ‘‘Recreational discount

seekers’’ are price-sensitive and, although

fashion conscious, they prefer sale and

discounted prices. This group of Y consumer

needs to be informed of future price reductions

and would favour marketing programmes that

lead to monetary savings. Likewise, our results

would suggest that resources put into sale staff

selection and training, store atmospherics and

design, plus introducing fun into the selection

process e.g. through multi-media, would be

worthwhile expenditure. ‘‘Game-boy’’

equivalents could be used in stores/

departments where customers are invited to

play for prizes redeemable in the store. Also,

electronic clothes fitting might act as a fun way

of providing information about clothing ranges

and styles.

The fact that almost one in two adult female

Generation Ys pursue quality, even if it implies

higher prices, confirms that the recent practice

of supplying quasi-designer labels e.g. Top

Shop’s TS range and joint ventures with

established designers is a prescient move.

Retailers should continue to improve the

‘‘quality’’ dimension to their own-labels and

introduce higher priced ranges.

‘‘Recreational discount seekers’’ are

interesting in that they seem to pursue

quality, but are more price sensitive. It would

appear that adult female Generation Ys with

this trait might be prepared to pay high prices

as long as they perceive it as being discounted

in some way. Retailers might make use of this

trait by developing an on-going discounting

strategy as a means of getting adult female

Generation Ys into their stores. Rather than

using fixed sale periods that by their nature

occur on an infrequent basis, retailers might

opt for devoting a part of their retail space to

‘‘discounted/sale’’ lines or a ‘‘bargain corner’’.

Smart shoppers are known to enjoy the

challenge of achieving price savings and/or

product gains giving rise to the speculation

that price interest has become a dimension to

characterise a new lifestyle (Groppel-Klein

et al., 1999). Far from being seen as a ‘‘tight

wad’’ or other such pejorative labels for

discount seekers, these consumers are

regarded as clever and trendy. Retailers

catering for this group therefore, should

employ lots of sales promotions, coupon

services offered through magazines and even

loyalty cards for gaining discounts.

‘‘Trend-setting loyals’’ are attractive

customers to retailers because once

preferences are established, patronage is

assured. However, the identification of this

103

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

trait also suggests that marketers and retailers

targeting adult female Generation Ys may

have a greater problem of getting their store

or brand into a consumer’s ‘‘evoked set’’ if

they are not already favoured. Retailers and

marketers, therefore, need to be more

imaginative in encouraging adult female

Generation Ys to at least sample products or

enter stores. Youth marketing programmes,

perhaps involving colleges and activities for

teenage girls, would seem to be an

appropriate strategy for companies to

establish brand preferences early. Retailers

targeting this segment should consider

customer loyalty programmes and might offer

additional services relating to fashion such as

in-store magazines and sales staff with

knowledge of forthcoming trends. Identifying

key items for the coming season would be

valued by this group and would imply having

strong links with up and coming designers.

‘‘Confused time/money conserving’’ Ys like

to shop quickly and depend on price to help

them, but they frequently feel confused.

Retailers catering for this group should focus

on two things. First, they should provide

information that either helps to make

monetary judgements, e.g. pence per gram, or

they could provide descriptions as to how the

product choice is economical, e.g. financial

benefits of durability. Second, retailers should

think about simplified store layouts and

payment services and a reduction in the

number product lines, etc. to speed up the

shopping process.

‘‘Shopping and fashion uninterested’’

consumers are the most market resistant of

the Y shoppers and would probably benefit

from e-commerce/catalogue shopping and/or

subtle forms of marketing promotion.

Retailers targeting this particular segment

would need to provide a range of goods that

were positioned as lower priced and not

fashionable.

Limitations and future research

Limitations of the present study provide

fertile ground for future studies. For example,

the use of students has limitations since the

degree to which education affects their

purchasing is uncertain. However, with

approximately one-third of this cohort

population in higher education and a

significant proportion of others studying

elsewhere, this limitation is only a problem for

generalising to other less educated

Generation Y consumers.

The study used a female-only sample and

future research should address whether the

decision-making styles and the shopper

typology are generalisable to male Generation

Ys. Many authors propose that gender has a

marked effect on shopping behaviour (e.g.

Fischer and Gainer, 1991; Campbell, 1997;

Buttle, 1992; Miller, 1998).

A major proposition of the research is that

shoppers change as a function of their

generation membership because of macro-

environmental influences. If true, items

pertaining to classify and measure shopping

practices/influences and values need to adjust

accordingly. The CSI was developed in the

1980s and we could argue that it fails to

capture emerging phenomena such as ‘‘smart

shopping’’. Future research needs to update

and test the CSI items in light of these

developments. Furthermore, the CSI was

developed to measure shopping attitudes and

behaviours for personal goods. We

acknowledge that our findings may be

influenced by the degree of involvement for

these goods and future studies could replicate

the study for staples such as groceries.

Finally, further research should consider

the implications of a cohort where so many

enjoy shopping and pursue it as a form of

recreation. Recently, it has been noted that

there are a number of pathologies associated

with shopping, for example, addictive and

compulsive shopping (e.g. Scherhorn et al.,

1990; Faber and O’Guinn, 1988). Roberts

(1998) found that, amongst a sample of

Generation X students, 6 per cent were

classified as compulsive buyers. Given that

Generation Ys would seem to have even

greater opportunities to spend should be

studied to see whether their love of shopping

leads to this particular problem.

Notes

1 For an overview of shopping topologies and

research methodologies see Jarratt (1996).

2 There is some discussion about the exact years that

encompass Generation Y. Teenage Research

Unlimited defines the generation as those born

between 1979 and 1995 (TRU, 1999), while others

claim that the generation encompasses all those

born after 1977 (Bainbridge, 1999; Saatchi &

Saatchi, 1999; Walker et al., 1998).

104

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

3 For a description of the characteristics of a

postmodern environment see Firat and Schultz

(1997).

4 ``Flow’’ is described as an extremely pleasurable

state gained by experiencing challenge and control.

In the case of shopping, it has been proposed that

some consumers find the experience particularly

pleasurable because it is a controlled and safe

environment that also involves the challenge of

achieving the best possible purchase.

References

American Demographics (1995), ``The people, the places,

the money’’, February, pp. 26-9.

Bainbridge, J. (1999), ``Keeping up with Generation Y’’,

Marketing, 18 February, p. 37-8.

Baker, L. (2000), ``Youth obsessed retailers must look to

an older group of big spenders’’, The Independent,

25 April, p. 15.

Belk, R.W. (1985), ``Materialism: Trait aspects of living in

the material world’’,

Research, Vol. 12, December, pp. 265-81.

Bellenger, D.N. and Korgaonker, P.K. (1980), ``Profiling the

recreational shopper’’, Journal of Retailing, Vol. 56

No. 3, Fall, pp. 77-91.

Bloch, P.H., Ridgway, N.M. and Nelson, J.E. (1991),

``Leisure and the shopping mall’’, Advances in

Consumer Research, Vol. 18, pp. 445-52.

Bocock, R. (1993), Consumption, Routledge, London.

Buttle, F. (1992), ``Shopping motives constructionist

perspective’’, The Services Industry Journal, Vol. 12

No. 3, pp. 349-67.

Calder, B.J., Philips, L.W. and Tyhout, A. (1981),

``Designing research for application’’,

Consumer Research, Vol. 8, September,

pp. 197-207.

Campbell, C. (1997), ``Shopping, pleasure and the sex

war’’, in Falk, P. and Campbell, C. (Eds),

The Shopping Experience?, Sage, London.

Chaney, D. (1983), ``The department store as a cultural

form’’, Theory,

Culture and Society, Vol. 1 No. 3,

Craik, L. (1999), ``The rebirth of cool’’, The Guardian,

22 October, pp. 10-11.

Cravatta, M. (1997), ``Online adolescents’’,

American Demographics, August, p. 29.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975), Beyond Boredom and

Anxiety, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA.

Damon, J.E. (1988), Shopaholics: Serious Help for

Addicted Spenders, Price, Stern and Sloan,

Los Angeles, CA.

Darden, W.R. and Ashton, D. (1975), ``Psychographic

profiles of patronage preference groups’’, The

Journal of Retailing, Vol. 50, Winter, pp. 99-112.

Darden, W.R. and Reynolds, F.D. (1971), ``Shopping

orientations and product usage rates’’,

The Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 8,

November, pp. 505-8.

Dholakia, R.R. (1999), ``Going shopping: key determinants

of shopping behaviors and motivations’’,

International Journal of Retail & Distribution,

Vol. 27 No. 4.

Ebenkamp, B. (1999), ``Tipping the balance’’, Brandweek,

May 10, p. 4.

Faber, R.J. and O’Guinn, T.C. (1988), ``Compulsive

consumption and credit abuse’’, Journal of

Consumer Policy, Vol. 11, Spring, pp. 97-109.

Falk, P. and Campbell, C. (1997), The Shopping

Experience, Sage, London.

Fielding, H. (1994), ``Spoilt for choice in all the clutter’’,

Independent , 3 June, p. 23.

Firat, A.F. and Shultz, C.J. (1997), ``From segmentation to

fragmentation: markets and marketing strategy in a

postmodern era’’,

European Journal of Marketing,

Fischer, E. and Gainer, B. (1991), ``I shop therefore I am:

The role of shopping in the social construction of

women’s identities’’, in G.A. Costa (Ed.), Gender

and Consumer Behavior, University of Utah Press,

Salt Lake City, UT.

Ger, G. and Belk, R.W. (1996), ``Cross-cultural differences

in materialism’’,

Journal of Economic Psychology,

GroÈppel-Klein, A., Thelen, E. and Antretter, C. (1999),

’’The impact of shopping motives on store

assessment’’, European Advances in Consumer

Research, Vol. 14, pp. 63-72.

Heckman, J. (1999), ``Today’s game is keep-way’’,

Marketing News, 5 July, pp. 1-3.

Herbig, P., Koehler, W. and Day, K. (1993), ``Marketing to

the baby bust generation’’,

Marketing, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 4-9.

Hirschman, E.C. and Holbrook, M.B. (1982), ``Hedonic

consumption: emerging concepts, methods and

propositions’’, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 46,

Summer, pp. 92-101.

International Council of Shopping Centres (1997), Press

Release.

Jansen-Verbeke, M. (1987), ``Women, shopping and

leisure’’, Leisure Studies, Vol. 6, pp. 71-86.

Jarratt, D.G. (1996), ``A shopper taxonomy for retail

strategy development’’, The International Review of

Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, Vol. 6

No. 2, pp. 196-215.

Jones, M.A. (1999), ``Entertaining shopping experiences:

an exploratory investigation’’,

and Consumer Services, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 129-39.

Kara, A., Kaynak, E. and Kucukemiroglu (1994), ``Credit

card development strategies for the youth market’’,

International Journal of Bank Marketing, Vol. 12

No. 6, pp. 30-6.

Lehtonen, T.K. and Maenpaa, P. (1997), ``Shopping in the

East Centre Mall’’, in Falk, P. and Campbell, C. (Eds),

The Shopping Experience, Sage Publications, London.

McDonald, W.J. (1993), ``The roles of demographics,

purchase histories and shopper decision-making

styles in predicting consumer catalogue loyalty’’,

The Journal of Direct Marketing, Vol. 7 No. 3,

pp. 55-65.

Mano, H. and Elliot, M.T. (1997), ``Smart shopping the

origins and consequences of price savings’’, in

Brooks, M. and MacInnes, D. (Eds), Advances in

Consumer Research, Vol. 24, ACR, Provo, UT,

pp. 504-10.

Mellon, J. (1995), Overcoming Spending, Walker and Co.,

New York, NY.

Miller, D. (1998), A| Theory of Shopping, Blackwell

Publishers, Oxford.

105

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

Minsky, R. (2000), ``Consuming `goods’’’, in Baker, A.

(Ed.), Serious Shopping: Essays in Psychotherapy

and Consumerism, Free Association Books, London.

Mitchell, S. (1995), The Official Guide to Generations:

Who They Are, How They Live, What They Think,

New Strategist Publications, Ithaca, NY.

Mitchell, V.W. and Papavassiliou, V. (1999), ``Marketing

causes and implications of consumer confusion’’,

The Journal of Product and Brand Management,

Vol. 8 No. 4. pp. 319-42.

Moschis, G.P. (1976), ``Shopping orientations and

consumer uses of information’’, Journal of Retailing,

Vol. 52, Summer, pp. 61-70, 93.

Moschis, G.P. (1987), Consumer Socialisation: A Lifestyle

Perspective, Lexington Books, Lexington, MA.

Moschis, G.P. and Churchill, G.A. (1978), ``Consumer

socialisation: a theoretical and empirical analysis’’,

Journal of Marketing, Summer, pp. 40-8.

Moschis, G.P. and Cox, D. (1989), ``Deviant consumer

behaviour’’, in Srull, T. (Ed.), Advances in Consumer

Research, Vol. 16, Association for Consumer

Research, Provo, UT, pp. 732-6.

Newborne, N. and Kerwin, K. (1999), ``Generation Y’’,

Business Week, 15 February, pp. 80-8.

Nielsen, A.C. (1995), Nielsen Report on Television,

A.C. Nielson Co., Northbrook, IL.

O’Guinn, T.C. and Shrum, L.C. (1997), ``The role of

television in the construction of consumer reality’’,

Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 23, March,

pp. 278-94.

O’Guinn, T.C., Faber, R.J. and Rice, M. (1985), ``Popular

film and television as consumer acculturation

agents. America 1900 to present’’, in Sheth, J.N.

and Tan, C.T. (Eds), Historical Perspectives in

Consumer Research: National and International

Perspectives, ACR, Washington, DC, pp. 297-301.

Otnes, C. and McGrath, M.A. (2000), ``Perceptions and

realities of male shopping behaviour’’,

Retailing, Vol. 77 , pp. 111-37.

Pine, J., Peppers, D. and Rogers, M. (1995), ``Do you want

to keep your customers forever?’’, Harvard Business

Review, March-April, pp. 103-14.

Phelps, M. (1999), ``The millennium kid’’, The International

Journal of Advertising and Marketing to Children,

14 June, pp. 135-9.

Phillips, A. (1997), ``The difficulty of discovering what

makes Euro-teens tick’’,

Punj, S.N. and Stewart, D.W. (1983), ``Cluster analysis

in marketing research: review and suggestions

for application’’, Journal of Marketing Research,

Vol. 20, May, pp. 134-48.

Quelch, J.A. and Kenny, D. (1994), ``Extend profits not

product lines’’,

Harvard Business Review, Vol. 72

Ritzer, G. (1995), Expressing America: A Critique of the

Global Credit Card Society, Pine Forge Press,

Thousand Oaks, CA.

Roberts, J.A. (1998), ``Compulsive buying among college

students: an investigation of its antecedents,

consequences and implications for public policy’’,

Journal of Consumer Affairs, Winter, Vol. 32,

pp. 295-308.

Roberts, J.A. and Manolis, C. (2000), ``Baby boomers and

busters: an exploratory investigation of attitudes

toward marketing, advertising and consumerism’’,

Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 17 No. 6,

pp. 481-97.

Saatchi & Saatchi, (1999), Landmark Study Discovers

Connexity Kids, Saatchi & Saatchi Press Release,

29 January.

Scherhorn, G., Reisch, L.A. and Raab, G. (1990),

``Addictive buying in West Germany: an empirical

study’’, Journal of Consumer Policy, Vol. 13,

pp. 355-87.

Schewe, C.D. and Noble, S.M. (2000), ``Market

segmentation by cohorts: The value and validity of

cohorts in American and abroad’’,

Marketing Management, Vol. 16, pp. 129-42.

Schor, J. (1998), The Overspent American: Upscaling,

Downshifting and the New Consumer, Basic Books,

New York, NY.

Schrum, L.J., O’Guinn, T.C., Semenik, R.J. and Faber, R.J.

(1991), ``Processes and effects in the construction of

normative consumer beliefs: the role of television’’,

Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 18,

Association for Consumer Research, Provo UT,

pp. 755-63.

Sproles, G.B. (1985), ``From perfectionism to daddism:

measuring consumers’ decision-making styles’’,

Proceedings American Council on Consumer Interest

Conference, Columbia, OH, pp. 79-85.

Sproles, G.B. and Kendall, E.L. (1986), ``A methodology for

profiling consumers’ decision making styles’’, Journal

of Consumer Affairs, Vol. 20 No. 2, pp. 267-79.

Stephenson, P.R. and Willett, R.P. (1969), ``Analysis of

consumers’ retail patronage strategies’’, in

McDonald, P.R. (Ed.), Marketing Involvement in

Society and the Economy, American Marketing

Association, Chicago, IL, pp. 316-22.

Stone, G.P. (1954), ``City shoppers and urban

identification: observations on the social psychology

of city life’’,

American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 60,

Strauss, W. and Howe, N. (1999), The Fourth Turning,

Broadway Books, New York, NY.

Tomkins, R. (1999), ``Step forward Generation Y:

advertisers are adopting alternative tactics to try to

appeal to today’s teenagers’’, The Financial Times,

28 December, p. 11

TRU (1999), Teenage Marketing and Lifestyle Study,

Press Release.

Walker, Smith, J. and Clurman, A.A. (1998), Rocking the

Ages: The Yankelovich Report on Generational

Marketing, Harperbusiness, New York, NY.

Wells, W.D. and Anderson, C.L. (1996), ``Fictional

materialism’’, in Corfman, K.P and Lynch, J.G. Jr

(Eds), Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 23,

Association for Consumer Research, Provo UT,

pp. 120-6.

Westbrook, R. A. and Black, W. (1985), ``A motivation

shopper based typology’’, The Journal of Retailing,

Vol. 61, Spring, pp. 78-103.

Wolburg, J.M. and Pokryvczynski, J. (2001), ``A

psychographic analysis of Generation Y college

students’’, Journal of Advertising Research,

September/October, pp. 33-52.

Zollo, P. (1999), Wise up to Teens: Insights into Marketing

and Advertising to Teenagers, New Strategist

Publications, New York, NY.

106

Generation Y female consumer decision-making styles

Cathy Bakewell and Vincent-Wayne Mitchell

International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management

Volume 31 . Number 2 . 2003 . 95-106

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Generacja sygnalow i generatory Nieznany

Generatory przebiegow niesinuso Nieznany

Generating CNC Code with Edgeca Nieznany

Local and general anaesthetics Nieznany

GENERATORY 1213 id 187311 Nieznany

generator impulsow id 187198 Nieznany

generator wodoru instrukcja id Nieznany

generalne perspektywy rynku usl Nieznany

Mechatronika nowa generacja mas Nieznany

generator funkcji (1) id 187188 Nieznany

BioGas Generator id 87121 Nieznany (2)

7 GENERATORY NAPIEC SINUSOIDAL Nieznany

generatory NM5WUF2Z3ZGPDIMV66A6 Nieznany

10 Generatoryid 10548 Nieznany (2)

6 WSPOLPRACA GENERATORA SYNCHOR Nieznany (2)

Badanie generatorow id 77136 Nieznany

Generatory przebiegow niesinuso Nieznany

więcej podobnych podstron