Structures of literature

Linguistics as a model for

literary studies

Signification

• Structuralist methodologies draw on linguistic theory:

• Ferdinand de Saussure (1857 – 1913) a Swiss linguist whose

ideas laid a foundation for many significant developments in

linguistics in the 20th century, one of the fathers of 20th-century

linguistics

• Charles Sanders Peirce

(1839 –1914) an American pragmatist,

logician, mathematician, philosopher, and scientist, coined the

term "pragmatism" in the 1870s.

What is signification?

What are the fundamental concepts for generating meaning?

• Signification (word meaning) is a tripartite relation of:

- signifier

(the word in the graphic - written or phonic - spoken

form),

- signified

(the concept attached to the word) united in the

sign.

- referent

(the item to which the sign refers.)

• >> 3 elements united in a sign

• To simplify: there is a word together with a concept and an

object

What is signification?

• ‘a chair’ ,

• ‘a piece of furniture’

• an object

What is signification?

Where does the meaning reside?

• in a form of the signified – concepts - which function within the

system of signification.

• Meaning does not exist in isolation, a linguistic item means

because it is a part of a system where meaning is generated.

• The linguistic sign is arbitrary – there is no natural relation

between the signifier (sound-image) and the signified (the

concept).

But:

the only non-arbitrary examples

• Sound relation: onomatopoeia

• Image relation: Chinese ideograms, sign language, ‘@’

• The meaning focuses on the present uses of a given word. The

historical usage does not imply the contemporary usage.

What is structuralism?

• Structuralism - the nature of social universe expressed by the linguistic

idea of systems

• >> entities are made of smaller systems, which in turn comprise

smaller and smaller structures, like going from ‘text’ to ‘phoneme’- the

smallest meaningful unit.

What is phoneme?

• It is the smallest meaningful unit which is meaningful only in the

context of a complex system.

• Its meaning resides in its negative distinction of what it is not - binary

opposition between /p/ and /b/.

• 45 phonemes in English are capable of generating an infinite number of

signs.

What is language?

• Language is a complex, interdependent and finite system where the

smallest unit is responsible for creating meanings.

• It is independent of the decisions of the individual user.

• Language is governed by sets of rules and regulations which a user

must conform to.

What is structuralism?

How to apply these findings to literary methodologies?

• Literature is yet another linguistic system,

• It is constructed as a framework of structures complete in

themselves

• It has its own internal laws and does not admit any external

influences from outside the system like ‘history’ or ‘context’

The macro-level: grammars

F. Saussure’s distinction between:

• la langue (a particular language, an underlying system, „grammar”)

• la parole (the speech of that language, an individual speech act or

utterance, which is creative on the basis of the rules and

forms of la parole)

How can we apply it to literary studies?

• a parole literary production (an individual act)

• a langue the social existence of literature

(the whole which creates a coherent system)

• >>A possibility of formulating a theoretical ‘grammar’ of literature

which can be observed on the basis of particular realisations of literary

texts.

• The possible grammar of literature could provide us a tool to understand

what the text might mean by analysing its forms and structures.

The macro-level: grammars

Roland Barthes (1915- 1980)

a French literary theorist, philosopher, linguist,

critic, and semiotician. Barthes' ideas explored a diverse range of fields

and he influenced the development of schools of theory

includingstructuralism,semiotics, anthropology and post-structuralism

• Roland Barthes :by searching meaning of a text he means ‘reconstruction

of the rules and constraints (‘grammar) upon that meaning’s elaboration.

• He looks for a model which determines all kinds of literary outputs.

• It is not men who create literary structures, it is the structures which men

adopt to state something

• For a structuralist, form is content and meaning is the structure which

generates it.

• Relation between grammar and texts - macro level

Grammar of texts:

- excludes external elements such as context and history, class, race and

gender differences

-it is universal, it accounts theoretically for the generation of texts in a

given genre

The micro-level: syntax of texts

micro-level – relation between sentence and an individual text

It was a glorious April morning when

Edith Brown

decided to finish her young life and plunge

down the rocky cliffs of Moher into the cold waters of

the ocean.

-

a syntactic analysis of a sentence shows an analogy to certain

elements in a story:

• nominal phrase a protagonist of a story

• predicate an event, a plot

• adjuncts of time chronology

• adjuncts of place setting

• active > passive voice plot transformations

• the form of the story is transformed into content while paradoxically

the content itself is ignored.

Structural analysis of

narratives

• Narratology has been one of successes of structuralism.

• Features of a narrative:

>

it possesses a story and a plot (which transforms the events by

combining temporal succession with cause)

> time in narrative is not always linear as it is in reality

>a narrative is told from a particular point of view = narration. (The

story behind the narrative is already transformed when we read it as a

text)

• the texts operates as a move from a certain state to another. (poor>

rich, unmarried >married) in which the latter is always the inversion of

the former.

• Characters can be reduced to ‘functions’ thus a structuralist analysis

focuses not on the emotional life of the protagonist but as a

participant to the story.

Structural analysis of

narratives

Algirdas Julien Greimas (1917- 1992),

the most prominent of the

French semiologists. With his training in linguistics, he added to

the theory of signification and laid the foundations for the Paris

School of Semiotics.

•

narratives are seen as aspects of human life

•

actants = the characters of a narrative are not what they

are but what they do.

•

two actants generate essential actions, participate in

three main semantic areas: communication, desire (quest)

and ordeal.

•

their choice is bound by the paradigmatic structure

(subject/object, donor/receiver, helper/opponent), which is

projected along the narrative.

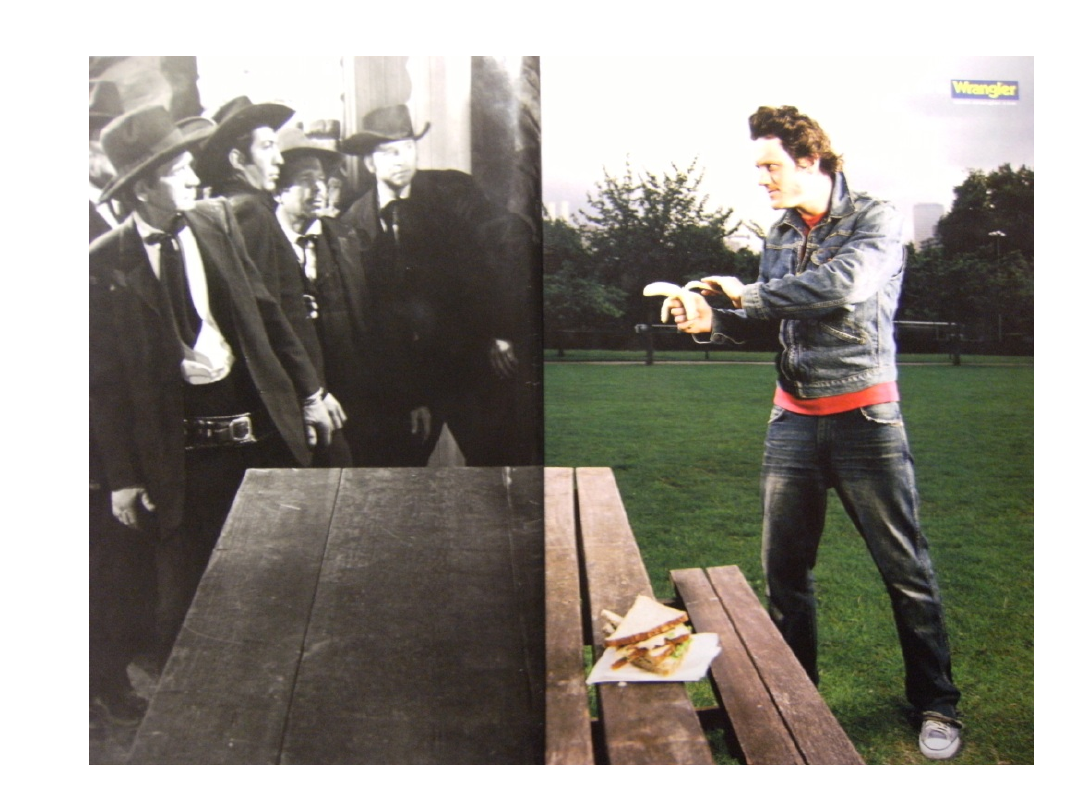

Semiotics

•

Semiotic analysis is the most common form in which

structuralist criticism is encountered.

•

Semiotics approaches popular culture where ‘texts’ are

less likely to be literary works than advertisements,

movies, TV programmes, magazines, etc.

•

It equates popular culture with high culture

•

Images treated as signs - the visual image is intelligible

to a group of people who do not have to speak the

same language. (signified has various signifiers)

Semiotics

• Advertising - an audience of consumers make meaningful connections

between apparently disparate signifiers and signifieds.

(e.g. sexualised adverts of sweets, cigarettes etc. a bar of chocolate

becomes a phallic symbol)

• Adverts take into account both the attributes of the products and the

possible meanings.

>> the attributes of the chocolate Flake are its distinctive shape and

texture > made to mean sexual desire and satisfaction.

• Meanings are not obviously stated , they require the participation of

the consumer to make appropriate connections. It is the consumer

who invents various signifieds through the suggestions of the signifiers

used in an advert.

• Adverts are treated as visual texts, a narrative sequence (character

functions interact and create meaning by differentiation as in the

hero/villain binary in a narrative.

Silk Cut advert by David Lodge: Nice Work

'I suppose so. Yes, why not?'

'Because it would look like a penis cut in half,

that's why.'

He forced a laugh to cover his embarrassment.

'Why can't you people take things at their face

value?'

'What people are you refering to?'

'Highbrows. Intellectuals. You're always trying to

find hidden meanings in things. Why? A cigarette is

a cigarette. A piece of silk is a piece of silk. Why

not leave it at that?

'When they're represented they acquire additional

meanings,' said Robyn. 'Signs are never innocent.

Semiotics teaches us that.'

'Semi-what?'

'Semiotics. The study of signs.'

'It teaches us to have dirty minds, if you ask me.'

'Why do you think the wretched cigarettes were

called Silk Cut in the first place?'

'I dunno. It's just a name, as good as any other.'

"Cut" has something to do with the tobacco,

doesn't it? The way the tobacco leaf is cut. Like

"Player's Navy Cut" - my uncle Walter used to

smoke them.'

'Well, what if it does?' Vic said warily.

'But silk has nothing to do with tobacco. It's a

metaphor, a metaphor that means something like,

"smooth as silk". Somebody in an advertising

agency dreamt up the name "Silk Cut" to suggest a

cigarette that wouldn't give you a sore throat or a

hacking cough or lung cancer. But after a while the

public got used to the name, the word "Silk"

ceased to signify, so they decided to have an

advertising campaign to give the brand a high

profile again. Some bright spark in the agency

came up with the idea of rippling silk with a cut in

it. The original metaphor is now represented

literally. Whether they consciously intended or not

doesn't really matter. It's a good example of the

perpetual sliding of the signified under a signifier,

actually.'

A typical instance of this was the furious argument

they had about the Silk Cut advertisement...

Every few miles, it seemed, they passed the

same huge poster on roadside hoardings, a

photographic depiction of a rippling expanse of

purple silk in which there was a single slit, as if

the material had been slashed with a razor. There

were no words in the advertisement, except for

the Government Health Warning about smoking.

This ubiquitous image, flashing past at regular

intervals, both irritated and intrigued Robyn, and

she began to do her semiotic stuff on the deep

structure hidden beneath its bland surface.

It was in the first instance a kind of riddle. That is

to say, in order to decode it, you had to know

that there was a brand of cigarettes called Silk

Cut. The poster was the iconic representation of

a missing name, like a rebus. But the icon was

also a metaphor. The shimmering silk, with its

voluptous curves and sensuous texture,

obviously symbolized the female body, and the

elliptical slit, foregrounded by a lighter colour

showing through, was still more obviously a

vagina. The advert thus appealed to both senual

and sadistic impulses, the desire to mutilate as

well as penetrate the female body.

Vic Wilcox spluttered with outraged derision as

she expounded this interpretation. He smoked a

different brand himself, but it was as if he felt his

whole philosophy of life was threatened by

Robyn's analysis of the advert. 'You must have a

twisted mind to see all that in a perfectly

harmless bit of cloth,' he said.

'What's the point of it, then?' Robyn challenged

him. 'Why use cloth to advertise cigarettes?'

'Well, that's the name of 'em, isn't it? Silk Cut. It's

a picture of the name. Nothing more or less.'

'Suppose they'd used a picture of a roll of silk cut

in half - would that do just as well?'

Document Outline

- Slide 1

- Slide 2

- Slide 3

- Slide 4

- Slide 5

- Slide 6

- Slide 7

- Slide 8

- Slide 9

- Slide 10

- Slide 11

- Slide 12

- Slide 13

- Slide 14

- Slide 15

- Slide 16

- Slide 17

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Lesley Jeffries Discovering language The structure of modern English

Prezentacja Master Of Hypnotic Learning 1 edycja

SCI03 Model Making Workshop Structure of Tall Buildings and Towers

1 Structure of employment of different countries

Prezentacja maturalna kobiety w literaturze, prezentacje

Theory of literature MA course 13 dzienni

The Importance of Literature vs Science

The Importance of Literacy

prezentacja - obraz szatana w literaturze, Wypracowania szkolne i prezentacje ustne

Prezentacja 01, PREZENTACJA MATURALNA, OGRÓD w literaturze, malarstwie i muzyce, prezentacja tematu

Internal Structure of the?rth

materialy z alkoholi Nomenclature and Structure of Alcohols

Materiały pomocnicze - cytaty, PREZENTACJA MATURALNA, OGRÓD w literaturze, malarstwie i muzyce, prez

Analysis of spatial shear wall structures of variable cross section

Theory of Literature Study Guide dzienni

Molecular structure of rubidium six

Lesley Jeffries Discovering language The structure of modern English

więcej podobnych podstron