PTSD, GUILT, AND SHAME AMONG RECKLESS DRIVERS

TAMAR LOWINGER and ZAHAVA SOLOMON

School of Social Work, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel

This study examines posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), guilt, and shame among men

convicted of having caused death through reckless driving. It also examines the contribution of

sociodemographic variables, accident-related variables, and punishment-related variables to

these outcomes. Seventy-¢ve men participated in the study, 38 who accidentally caused the death of

another in a road accident and 37 matched controls. Findings show that drivers who accidentally

caused the death of another are a high-risk group for PTSD and accident-related guilt.The ¢nd-

ings also reveal that PTSD and guilt are associated with severity of the punishment, degree of

responsibility the driver assumes for the accident, and the driver’s sense that he could have

prevented the accident. Clinical implications are discussed.

Road accidents are recognized as traumatic events (Kinzie, 1989) and

have been implicated in driving phobia, agoraphobia (Parker, 1977), anxi-

ety (e.g., Mayou, 1992; Mayou et al., 1993), depression (e.g., Blanchard

et al., 1991; Foeckler et al., 1978; Goldberg & Breznitz, 1982; Malt, 1988),

and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Bryant & Harvey, 1996;

Feinstein & Dolan, 1991; Kessler et al., 1995). Yet, almost all of the literature

on the pathogenic e¡ects of such accidents deals with persons who were

injured in the accident and tends to ignore the drivers who caused the

death of others. The few studies of drivers involved in fatal accidents con-

sist mainly of clinical reports (e.g., Kogan, 1990). The present study thus

focuses on drivers who caused the death of another person in an auto

accident that they themselves survived.

The research that bears most closely on the issue at hand consists of two

studies of policemen who were involved in shooting incidents in the line of

Received 1 March 2004; accepted 2 May 2004.

Address correspondence to Zahava Solomon, Adler Research Center, School of Social Work,Tel Aviv

University, Ramat Aviv, Tel Aviv, Israel 69978. E-mail: Solomon@post.tau.ac.il

Journal of Loss andTrauma

, 9: 327^344, 2004

Copyright # Taylor & Francis Inc.

ISSN: 1532-5024 print=1532-5032 online

DOI: 10.1080/15325020490477704

327

duty in which citizens were killed or seriously injured. One study (Stratton

et al., 1986) found that a third of the policemen su¡ered from severe post-

traumatic residuals and that another third su¡ered from subclinical PTSD.

The second study (Gersons, 1989) found that about 78% su¡ered from

PTSD, although none of the policemen who were involved in a fatal shooting

incident sought professional help on their own initiative.

However, policeo⁄cers who kill in the line of duty di¡er markedly from

drivers who unintentionally kill in a road accident. Policeo⁄cers carry

weapons, are trained for violent encounters, and shoot to hit. Drivers who

cause death have no conscious intention of killing or injuring their victim;

they often know the victim and, in some cases, were close to the victim; and

they are viewed by the law as reckless.

Manmade catastrophes have been found to be grounds for severe guilt

feelings. Guilt is de¢ned as an emotional state stemming from an individual’s

awareness that he or she violated moral, social, or ethical principles. In this

state, individuals who su¡er from guilt view their speci¢c past behaviors

negatively, regret those behaviors, and feel the need for punishment to pay for

the injury they caused (Kugler & Jones, 1992; Tangney, 1990, 1991, 1992;

Tangney et al., 1989; Wolman, 1973).

Guilt feelings are an inherent part of trauma. Persons who su¡er from

posttraumatic residue describe guilt feelings both regarding their own survi-

val when others died in the catastrophe (survivor guilt) and regarding their

conduct at the time of the traumatic event, in that they did not do enough to

prevent it and its results (Glover, 1984; Jano¡-Bulman & Wortman, 1977).

In every traumatic event in which individuals feel extreme threat, fear, and

helplessness, there is an inherent tendency to feel that, in a way, they are being

deservedly punished. The tendency to feel guilt in the wake of a traumatic

event sometimes constitutes an externalization of feelings of fear and is

anchored in feelings of powerlessness and loss of control at the time of the

catastrophe (e.g., Hendin & Haas, 1984).When one was not only exposed to a

traumatic event but was also involved in causing it, the sense of guilt can be

expected to be even more intense.

The association between guilt anchored in a traumatic event and depres-

sion has been found among male soldiers and civilian women who underwent

physical torture (Kubany et al., 1995). In both groups, the more responsibility

the victims assumed for having caused the traumatic event, the more they

viewed their behavior as wrong and unjusti¢ed, the more they believed that

their conduct violated their personal values, and the more they believed that

they could have and should have prevented the traumatic event, the higher

328

T. Lowinger and Z. Solomon

the level of PTSD symptoms and depression from which they su¡ered

(Kubany et al., 1995).

The study of guilt and posttraumatic residuals among persons who cause

death or injury has focused primarily on soldiers and policemen, where there

is an intention of and sometimes also legitimization for injuring another. The

issue has not been examined among other populations of perpetrators or in

other traumatic situations, among them motor vehicle accidents (MVAs).The

present study aims to increase our understanding and knowledge of the

subject.

Furthermore, after an accident, along with deep feelings of anger and sad-

ness and often the reproach of the relatives of the dead, the legal system is also

involved. Another feeling that has been found to be related to PTSD is the

feeling of shame. Gilbert (1998) views shame as associated with beliefs that

others look down on oneself and see one as inferior, inadequate, disgusting, or

weak in some way. Jackley (2001) examined the relationship between self-

reported symptom distress and shame in regard to the postwar adjustment of

combat veterans. The study showed a signi¢cant and positive relationship

between shame and PTSD, depression, trait anxiety, and vulnerability.

Similar ¢ndings have been reported among battered women (Street & Arias,

2001).

The literature points to considerable variance in survivors’ psychological

responses to traumatic events. At least part of this variance may be explained

by situational, social, cultural, and personality variables. Many studies have

found that the features of the traumatic event make a special contribution to

its psychological impact (e.g., Green et al., 1985). For instance, Lifton (1967)

found that survivor’s guilt was related to the extent of the physical and emo-

tional closeness to the victim. The more the survivor felt close to the person

who was killed, the higher the intensity of guilt. Jano¡-Bulman andWortman

(1977) found that the more people believed that they could have prevented the

accident, the more they blamed themselves, and the more time that had

passed since the traumatic event, the more they tended to cast the blame on

environmental factors. They also found that those who blame themselves are

divided into two groups. One group consists of people with trait self-blaming,

who tend to feel global guilt out of their belief of being incapable persons, and

the other group consists of people with behavioral self-blaming, who feel

guilty as a result of a speci¢c experience.

The reaction of society has also been found to contribute to adaptation in

the aftermath of trauma. A study of rape victims (Frieze et al., 1987) pointed

to the problematic situation such victims were caught in.Their self-esteem was

PTSDAmong Reckless Drivers

329

negatively a¡ected, and they had to deal with feelings of guilt and shame

resulting from social judgment. Similarly, reckless drivers are criticized and

highly judged by their society for what they have done.

We hypothesize that reckless drivers experience intense negative feelings as

a result of the accident. Thus, our aims in the present study were to (a)

examine PTSD, global guilt, event-speci¢c guilt, and shame among drivers

who accidentally caused the death of others; (b) assess changes in the intensity

of the drivers’ PTSD and sense of guilt after the accident and in the course of

the legal process; (c) examine the association between PTSD, speci¢c guilt;

and global guilt; and (d) assess the contribution of variables associated with

the accident (acquaintance with the victim, seeing the corpse, emotional

relation with the victim) and variables associated with the legal process (type

of punishment, assessment of the severity of the punishment, admission of

guilt) to PTSD, guilt, and shame.

Method

Procedure and Subjects

After receiving permission from the Adult Probation Services (APS) to carry

out the study, we identi¢ed 65 persons who had caused the death of people as a

result of reckless driving and who were sent to the APS by court order so that a

report could be obtained about them. In the second stage, we held conversa-

tions with their individual therapists, following which nine persons who were

regarded as unsuitable for the study, mainly because of psychiatric problems,

were removed. After obtaining informed consent from the drivers to partici-

pate in the study, we mailed two sets of questionnaires to all of the subjects, one

set for them and one set for the prospective controls. Each subject was asked to

complete the set meant for the drivers and to give the other set to a friend of his

own age, gender, education, and marital status who had not been in a road

accident. These friends served as control subjects. Seventy-eight sets of ques-

tionnaires were sent to the persons identi¢ed for the study group. Seventy-six

questionnaires were returned by mail, constituting a 97.4% response rate.

Seventy-¢ve men in two groups participated in the study. The study group

(N

¼ 38) consisted of drivers involved in fatal MVAs who were found guilty of

causing death through reckless driving.These subjects had been referred to the

APS by the court. Members of the control group (N

¼ 37) were matched with

the study group on age and education but had not been involved in an MVA.

330

T. Lowinger and Z. Solomon

About a third of the subjects (37.3%) had graduated high school; another

third (32.1%) had a post^ high school education, and the remaining third

(30.7%) had an elementary school or partial high school education. Most of

the subjects (76%) were in the 19-to 30-year age range; about half (57.3%)

were single.

Questionnaires

The background questionnaire

tapped age, gender, education, military service,

professional occupation, family status, and religious attitudes. The PTSD

Inventory

(Solomon, 1993) is based on DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Asso-

ciation, 1994) criteria for the diagnosis of PTSD. It consists of 17 statements,

each describing a PTSD symptom. Subjects were asked to indicate whether

they had experienced each symptom at ¢ve points of time: (a) in the previous

month, (b) before the accident, (c) from the day of the accident to the start of

the trial, (d) from the start of the trial to the day of the verdict, and (e) from

the day of the verdict to the day of ¢lling out the questionnaire.

The control group was also asked to indicate whether they had experienced

a traumatic event in the past. Those who replied that they had were asked to

indicate what it was and when they experienced it. This questionnaire has

been widely used in trauma studies and has proven psychometric qualities.

The internal consistency (Cronbach alpha) among the 17 items was .89, and

the scale was found to have high convergent validity when compared with

diagnoses based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R

(Solomon et al., 1993).

In addition to these 17 statements, two symptoms relating to guilt were

queried. A distinction was made between ‘‘survivor guilt,’’ de¢ned as a deep

sense of guilt that the person had survived while others were killed in the

accident, and ‘‘event-speci¢c guilt,’’de¢ned as guilt feelings about the person’s

behavior at the time of the accident.

Guilt and shame were assessed via Tangney et al.’s (1989) Test of Self Con-

scious A¡ect

(TOSCA).This test consists of 15 short vignettes (10 negative and 5

positive) accompanied by 5 possible responses that point to a tendency toward

shame, guilt, externalization, dissociation, and pride. With regard to each

vignette, the respondents were asked to indicate the degree to which they

would respond on a 5-point scale ranging from ‘‘not at all likely’’ (1) to ‘‘most

likely’’ (5). Previous studies (Tangney,1990,1992; Barash-Kishon,1996) found

the shame and guilt factors to have good internal consistency. In the present

study, Cronbachs alpha were .70 for shame and .73 for guilt.

PTSDAmong Reckless Drivers

331

The Features of the Event Questionnaire

was constructed for the present study

based on clinical knowledge gathered by therapists treating persons who have

caused the death of others in MVAs through negligence. The questionnaire

contains 32 items on the circumstances of the accident, the trial, and the

punishment. The ¢rst part gathered information about the driversfor

example, their age and occupation at the time of the accident, whether or not

they sought professional help, and whether they discussed their feelings with a

close person. The second part contained questions and items about the trial

and sentence, including whether the driver admitted his guilt immediately

after the accident, whether he had a trial where evidence was brought, how

much time elapsed between the accident and the verdict and between the

verdict and the date of answering the questionnaire, whether the driver had

his driving license revoked, whether he was sentenced to prison, and his feel-

ings about the sentence. The third part of the questionnaire contained details

about the victims (age, identity) and the subjects’ relationship with them

(degree of prior acquaintance and feelings toward them).

Attributions of responsibility for the accident were examined via four

questions derived from the Questionnaire on Speci¢c Guilt (Jano¡-Bulman, 1989).

The questions were adapted to the study population and focused on the dri-

vers’ perceptions of the causes of the accident. The drivers were asked how

much they blamed themselves, others, the surroundings, and bad luck for the

accident and death and the degree to which they believed they could have

prevented the accident and the death.

Results

Group Di¡erences

First, we examined di¡erences between the study group, consisting of the

reckless drivers, and the matched control group with regard to PTSD, guilt,

and shame.

PTSD

In the study group, 76.3% of the subjects were classi¢ed as su¡ering from

PTSD after the accident; 44.7% of them still su¡ered from PTSD up to the

time of the study. In contrast, among the control subjects, 13% were classi¢ed

as su¡ering from PTSD following an event that they termed traumatic,

and only 5.5% were classi¢ed as su¡ering from the disorder in the present.

Chi-square tests indicated that these group di¡erences were signi¢cant both

332

T. Lowinger and Z. Solomon

immediately after the accident, w

2

(1)

¼ 29.84, p < .001, and at the time of the

study w

2

(1)

¼ 15.33, p < .001.

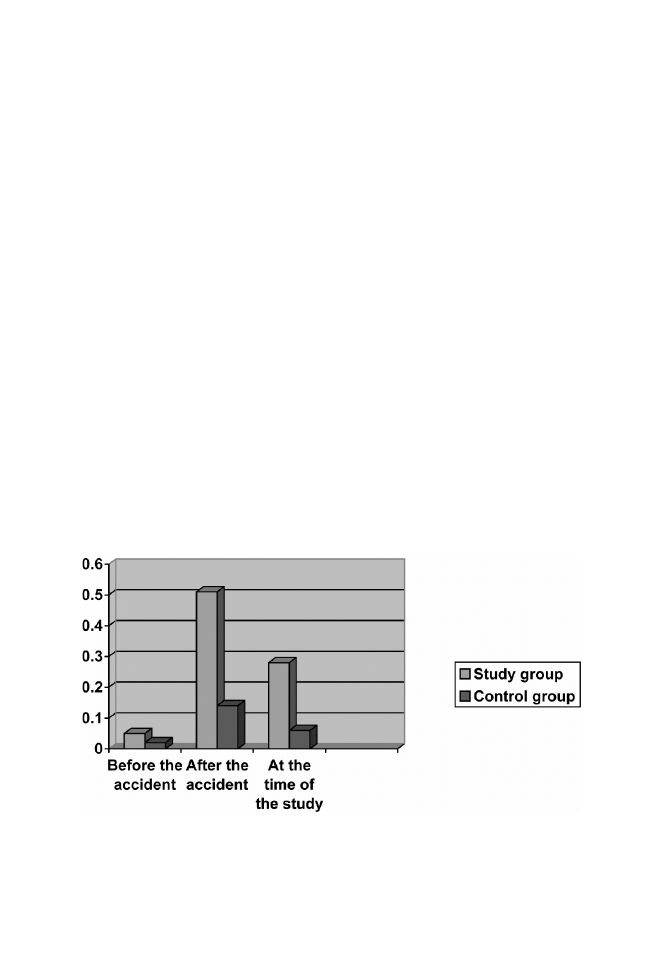

To assess the severity of the disorder, we examined group di¡erences in

number of PTSD symptoms at three points in time: before the accident, after

the accident, and at the time of the study. A one-way multivariate analysis of

variance (MANOVA) showed a signi¢cant group di¡erence over the three

periods, F(3, 67)

¼ 13.23, p < .01. Means and standard deviations for number

of PTSD symptoms in the two groups are presented in Figure 1.

Before the event, no group di¡erences were found. Yet, while the control

group continued to report the same low level of symptoms in the subsequent

two periods, the study group reported a signi¢cant increase in symptoms after

the event, followed by a decline in symptoms at the time of the study. At both

latter points, the study group reported signi¢cantly more symptoms than the

controls.

A 2

3 analysis of variance (Group Time) with repeated measures showed

a signi¢cant interaction, F(2,138)

¼ 18.76, p < .001. A test of simple main e¡ects

carried out to determine the source of the interaction showed a signi¢cant

di¡erence in time only in the study group.

Shame and Guilt

A MANOVA carried out to compare event-speci¢c guilt in the two

groups after the event and at the time of the study showed a signi¢cant group

FIGURE 1 The means of the number of PTSD symptoms in the two groups during three

periods of time.

PTSDAmong Reckless Drivers

333

di¡erence over the two times, F(2, 66)

¼ 22.02, p < .001. As expected, the

reckless drivers reported greater event-speci¢c guilt than the controls both

immediately after the event (drivers: M

¼ 2.27, SD ¼ 0.77; controls: M ¼1.19,

SD

¼ 0.54) and at the time of the study (drivers: M ¼1.73, SD ¼ 0.77; con-

trols: (M

¼1.09, SD ¼ 0.39).

Moreover, as with PTSD symptoms, the means showed a decline in guilt

feelings between the period immediately following the event and the time of

the study. An analysis of variance with repeated measures showed a sig-

ni¢cant di¡erence in event-speci¢c guilt feelings after the event and at the

time of the study, F(1, 67)

¼ 10.48, p < .01. Moreover, a signi¢cant interaction

was found between group and time, F(1, 67)

¼ 10.48, p < .01.The di¡erence in

the two groups’ current guilt was smaller than that at the time of the event.

A one-way multivariate analysis of covariance carried out to examine

group di¡erences in shame and global sense of guilt yielded no signi¢cant

di¡erences.That is, the drivers who caused death did not feel greater shame or

a stronger global sense of guilt than the controls.

In summary, examination of the di¡erences between the two groups clearly

showed that reckless drivers are a high risk group for PTSD and that their

symptoms may persist for a long period of time.The ¢ndings also clearly show

that this group is characterized by a relatively large number of PTSD symp-

toms and a high level of event-speci¢c guilt feelings.

Changes in Drivers’PTSD and Guilt Feelings OverT|me

We also examined changes in PTSD and guilt over time in the drivers’

group. The following points in time were measured: between the accident

and the start of the trial, between the start of the trial and the verdict,

between the verdict and the completion of the questionnaires, and in the

previous month.

PTSD

A total of 76.3% of the drivers were classi¢ed as having PTSD between the

accident and the start of the trial; 71.1% during the trial and before senten-

cing; 55.3%, after sentencing; and 44.7%, in the month prior to their ¢lling

out the questionnaire.

To examine changes in PTSD over time, we also calculated the average

number of PTSD symptoms in each period. Findings showed that, before the

accident, the drivers had very few PTSD symptoms. Following the accident,

the number of symptoms they reported rose sharply and then gradually

334

T. Lowinger and Z. Solomon

declined to a moderate level at the time of the study. An analysis of variance

with repeated measures showed signi¢cant di¡erences between the periods,

F

(4, 140)

¼ 59.51, p < .001.T tests for dependent samples carried out between

each pair of adjacent periods revealed signi¢cant di¡erences in the intensity of

PTSD in all of the periods within an overall pattern of decline. Sign-test

analyses (Sigel, 1956) performed to examine the di¡erences in the number of

persons classi¢ed with PTSD in the four periods revealed signi¢cant di¡er-

ences between the period covering the time between the accident and the start

of the trial and that covering the time between the start of the trial and sen-

tencing, as well as between sentencing and the time of the study. However, no

signi¢cant di¡erence was found between the two earlier periods and between

the two later periods.

Guilt

Similar time comparisons were carried out on the drivers’ guilt feelings.

The changes in guilt corresponded with those found for PTSD symptoms.

That is, the greatest guilt was reported in the period between the accident and

the sentencing. After that, the guilt feelings declined, reaching their lowest

level at the time of the study. Here too an analysis of variance with repeated

measures showed signi¢cant di¡erences in the four time periods, F(3,

102)

¼ 12.64, p < .001. Paired-comparison t tests showed a signi¢cant di¡er-

ence between all of the periods except for the ¢rst two (between the accident

and the start of the trial and between the start of the trial and the sentencing).

Features of the Accident, PSTD, and Guilt

The drivers were asked about their acquaintance with the victim, whether

they saw the corpse after the accident, and their feelings toward the victim. Of

the drivers, 44.27% knew the victim before his or her death. In 16.7% of these

cases, the victim was a family member; in the remaining 83.3%, the victim

was a friend or acquaintance. Fourteen percent of the drivers saw the corpse,

and most of the drivers (72%) reported positive feelings toward the victim.

Chi-square tests showed no signi¢cant association between any of these

variables and either PTSD or guilt feelings.

Sense of Responsibility for the Accident, PTSD, and Guilt

The respondents were asked how much they blamed themselves for having

caused the death, how much they believed that they could have prevented the

PTSDAmong Reckless Drivers

335

accident, and how much responsibility they believed that luck, circumstances,

some other factor, and they themselves bore for the accident.

The majority (54.4%) of the drivers viewed themselves as responsible for

the accident; 18.2% attributed the responsibility to the circumstances; 11.7%

attributed it to others; and 15.7% blamed luck. The degree of reported self-

blame was relatively high (M

¼ 3.42, SD ¼1.32) on a 5-point scale. Their

assessment that they could have prevented the accident was moderate

(M

¼ 2.76, SD ¼1.28).

Pearson correlations were carried out to examine the associations between

the responsibility variables, PTSD, and guilt.The coe⁄cients are presented in

Table 1.

As can be seen, signi¢cant positive correlations were found between self-

blame (the driver’s belief that he could have prevented the accident and his

attribution of the cause of the accident to himself ) and (a) PTSD symptoms

after the accident and (b) event-related guilt after the accident and at the time

of the study. Similarly, negative correlations were found between attribution

of the cause of the accident to other people and PTSD symptoms and event-

speci¢c guilt feelings. The more the drivers saw themselves as responsible for

the accident, the more PTSD symptoms they reported, and the more severe

their event-speci¢c guilt. On the other hand, no signi¢cant correlations were

found between these variables and intensity of PTSD at the time of the study.

A positive correlation was found between the driver’s belief that he could have

prevented the accident and his feelings of shame, and a negative correlation

was found between attribution of the accident to luck and feelings of global

guilt. Drivers who attributed the accident to luck felt less guilt.

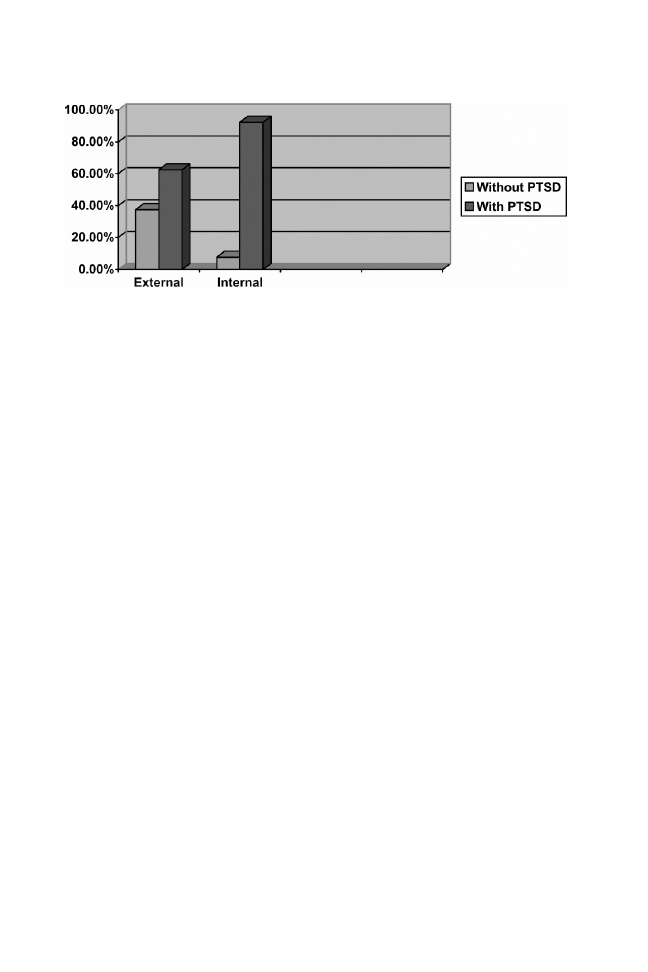

The drivers were asked to assess the reasons for the accident. Their answers

were grouped into two categories: internal reasons (e.g., my careless driving)

and external reasons (e.g., the car malfunctioned, weather conditions). Chi-

square tests carried out to determine whether there was any association

between causal attribution for the accident and PTSD after the accident and

at the time of the study showed signi¢cant di¡erences between drivers who

attributed the accident to external factors and those who attributed it to

internal ones in regard to PTSD at the time of the study, w

2

ð1Þ ¼ 3:80, p < .05,

and PTSD after the accident, w

2

ð1Þ ¼ 4:38, p < .05. Figure 2 presents the

¢ndings with regard to PTSD after the accident.

As can be seen, the PTSD drivers were more inclined to attribute the acci-

dent to internal causes than to external ones. At the time of the study, although

the number of PTSD drivers declined, those who attributed the accident to

external factors still tended to report fewer PTSD symptoms than those who

336

T. Lowinger and Z. Solomon

TA

B

L

E

1

P

ears

o

n

C

o

rr

el

a

tions

Be

tw

een

R

esp

o

n

si

b

il

ity

v

a

ri

a

b

le

s

a

nd

P

T

S

D

a

n

d

G

ui

lt

B

la

ming

the

self

for

ca

using

d

ea

th

Bel

ie

f

tha

t

the

a

cci

d

en

t

could

h

av

e

been

p

rev

en

te

d

L

u

ck

Ex

ternal

ca

use

s

Ot

h

er

pe

o

p

le

S

elf

P

T

S

D

sy

m

p

to

ms

at

ti

m

e

of

st

u

d

y

.2

2

.2

0

7

.28*

.0

3

7

.0

1

.1

7

P

T

S

D

sy

m

p

to

ms

aft

er

the

a

cci

d

en

t

.42*

*

.28*

7

.0

1

7

.0

1

7

.4

7

*

.3

2

*

S

peci

fi

c

g

u

il

t

at

ti

m

e

of

st

u

d

y

.4

8

*

*

.5

1*

*

7

.2

4

7

.0

8

7

.2

6

.3

7

*

S

peci

fi

c

g

u

il

t

aft

er

the

a

cci

d

en

t

.4

7*

*

.42*

*

7

.1

3

7

.1

1

7

.3

5

*

.3

8

*

S

h

a

m

e

.29

*

.29

*

7

.1

7

.1

0

7

.0

9

.1

1

Gl

o

b

al

gu

il

t

.0

9

.1

4

7

.28*

.2

2

7

.0

2

.07

*

p

<

.0

5;

*

*

p

<

.0

1.

337

attributed it to internal factors. In other words, the more the driver saw him-

self as responsible for the accident and the more he believed that he could have

prevented it, the more likely he was to su¡er from PTSD.

LegalVariables, PTSD, and Guilt

The subjects who accidentally killed persons were asked a number of questions

about the legal process, for example, whether they admitted their guilt and

the severity of their punishment (e.g., prison, community service, suspended

sentence). About 60% of the drivers had admitted their guilt to the police.

Most (62.5%) received community service. About a ¢fth (21.9%) received

prison sentences, and only 15.6% received suspended sentences. Close to half

(45.5%) felt that their punishment ¢t their crime. Over a third (36.4%) felt

that it was too severe. Only 18.2% felt that it was too lenient.

Chi-square tests revealed no signi¢cant association between these variables

and PTSD rates, either after the accident or at the time of the study. None-

theless, signi¢cant associations were found between the length of time for

which the person’s driving license was revoked and both his level of symptoms

after the accident (r

¼.40, p < .01) and his event-speci¢c guilt after the acci-

dent (r

¼.44, p < .01). Persons whose driving license was revoked for longer

periods reported higher levels of symptoms.

To examine the association between the legal process and feelings of guilt, t

tests were carried out on admission of guilt, and one-way analyses of variance

were carried out on perceived severity of the punishment. These analyses

showed no di¡erences with regard to admission of guilt and the judge’s

FIGURE 2 The distribution of drivers with and without PTSD after the accident according

to attribution of accident.

338

T. Lowinger and Z. Solomon

assessment of the punishment. But several signi¢cant di¡erences were found

in regard to subjects’assessment of the severity of the punishment.

Those who regarded their punishment as too lenient seemed to di¡er from

the two other groups on all of the measures. They reported more guilt and

more PTSD in the present, though the di¡erence did not reach signi¢cance.

The di¡erence was signi¢cant only for shame (punishment too severe:

M

¼ 2.69, SD ¼ 0.48; punishment appropriate, M ¼ 2.79, SD ¼ 0.64; punish-

ment too easy: M

¼ 3.82, SD ¼ 0.42). A Sche¡e paired-comparison analysis

showed that the di¡erence was between those who believed that their pun-

ishment was too lenient and the other two groups. It thus seems that persons

who believed that their punishment was too lenient tended to feel more guilt

and shame and to report more PTSD symptoms than those who believed that

their punishment was appropriate or too severe.

Discussion

Consistent with the ¢rst hypothesis, we found that men who caused the death

of others through reckless driving su¡ered from high rates of PTSD and event-

speci¢c guilt. While this study showed that around 45% of reckless drivers

continue to su¡er from PTSD, two recent prospective studies showed that

32% of road accident victims in Israel had PTSD 6 (Sayag, 2000) and 12

months after the accident (Koren et al., 1999). These ¢ndings suggest that

road accidents can cause psychological damage in both the victims and the

reckless drivers and that the latter are at even more risk than the former.

Most of our knowledge of the pathogenic e¡ects in perpetrators comes from

clinical observations of soldiers with PTSD (Haley, 1978; Hendin & Hass,

1984; Lifton, 1973). Both the careless driver and the soldier cause the death of

others, though it is important to remember that the circumstances and

meanings in the two cases are very di¡erent. Wars and road accidents di¡er

from one another both in the legitimacy they provide for killing and in the

emotional readiness of the perpetrators to cause and be exposed to death.

Causing death without malicious intent can explain the high rates of event-

speci¢c guilt found among the study group. Drivers who caused death and

remain alive become a target for feelings of anger, aggression, accusations,

and helplessness from all social circles: the families of the victims, society, and

the legal system.Thus, they feel a lack of legitimacy to externalize and express

their distress openly. Thus, as in other traumatized populations under similar

constraints, these feelings are displaced into strong feelings of guilt. The

PTSDAmong Reckless Drivers

339

drivers reported two sources for their guilt feelings. The ¢rst related to killing,

and thus crossing the boundaries of moral and social laws and values. The

second was that they themselves survived while others, sometimes their

friends and family, died because of their actions. The combination of causing

death and surviving intensi¢ed their speci¢c feelings of guilt.

On the other hand, global guilt and shame were not characteristic feelings of

reckless drivers. Subjects in the two groups did not di¡er from one another on

these measures. These ¢ndings are similar to a study of concentration camp

survivors, who did not di¡er in the level of guilt they experienced in their daily

lives from controls who had not been exposed to the Holocaust (Lobel &

Yahia, 1985). That is, our ¢ndings do not support generalizing from event-

speci¢c guilt feelings to general guilt feelings. This points to the need to distin-

guish between guilt that is speci¢c to and focused on a particular event and

guilt that is global and represents a personality tendency (Tangney,1990,1991).

With regard to changes over time, the highest rates of both PTSD and

speci¢c guilt feelings were reported in the period between the accident and

the sentencing, and gradually declined with time. The period between the

accident and the end of the trial was characterized by intense psychological

distress as the drivers were exposed to stimuli resembling or symbolizing the

traumatic accident. Furthermore, during the legal process the drivers had to

deal with both the court’s accusations and their own personal guilt. Kubany

et al. (1995) found that the intensity of guilt that individuals feel after a trau-

matic event depends on the degree to which they view the results of the event

as negative, see themselves as responsible for the negative results of the event,

see their act as unjusti¢ed, and believe that they could have prevented the

event had they acted di¡erently. In a way, the legal system acts as the ‘‘other

voice’’ that continues to remind the driver that he could or should have acted

di¡erently.

Our ¢ndings are similar to those of Kubany et al. (1995), who found asso-

ciations between the intensity of event-speci¢c guilt feelings and the rate of

PTSD symptoms among both American soldiers who had fought inVietnam

and physically abused women. The subjects in the present study di¡ered from

these groups in terms of age, ethnic origin, culture, gender, and, of course,

type of traumatic event. Nonetheless, our ¢ndings reinforce Kubany et al.’s

(1995) contention that it is important to deepen and broaden the systematic

study of di¡erent types of guilt and of their implications for PTSD.

Contrary to expectation, our ¢ndings showed no signi¢cant correlation

between the features of the accident and the legal process (e.g., acquaintance

with the victim, seeing the corpse after the accident, feelings toward the

340

T. Lowinger and Z. Solomon

victim, type and severity of punishment) and PTSD or guilt feelings. Our

¢ndings are inconsistent with a previous study of soldiers who were involved in

atrocities committed against civilians and prisoners. They were found to be at

higher risk for PTSD and had stronger guilt feelings than soldiers who fought

an enemy army from a distance and without close personal contact (Hendin &

Haas, 1984). The ‘‘ceiling e¡ect’’ phenomenon could serve as an explanation

for our ¢ndings. The ceiling e¡ect occurs when a variable is rated very highly

across all study groups, and this lack of variability prevents one from obtain-

ing signi¢cant results. As we have seen, causing death give rise to very high

negative feelings among the reckless drivers, and so other associated variables

such as acquaintance with the victim did not enhance PTSD rates and guilt as

we had expected (e.g., Fatzinger, 1997; Parente, 2001).

Drivers who perceived their punishment as too easy reported more feelings

of guilt, shame, and PTSD symptoms at the time of the study than drivers

who regarded their punishment as appropriate or too severe. It seems that

severe punishments made the reckless drivers feel as though they were paying

for what they had done or getting what they deserved thus promoting a sense

of relief. However, more than half of the drivers in this study assumed

responsibility for causing the accident, while the other half divided the

responsibility in roughly equal proportions between the surrounding circum-

stances, luck, and other people.

In the last two decades, substantial e¡orts have been made to study the

psychological e¡ects of traumatic events. In light of the proliferation of stu-

dies, the limited attention paid to perpetrators is salient. The high rates of

psychological distress found among the perpetrators in this study and in other

studies (e.g., Haley, 1978) raise the question of why these individuals receive

limited professional attention.

Haley (1978) pointed out the di⁄culties that therapists experience in

treating Vietnam veterans who had been involved in atrocities, suggesting

that these encounters challenge their values and give rise to feelings of vul-

nerability. Similar observations were documented in a study of o¡spring of

Nazi perpetrators conducted by Bar-On (1989; Bar-On & Charny, 1988).

Bar-On claims that both perpetrators and professionals use denial when they

are engaged in a dialogue. He suggested that there is a ‘‘double arrow’’

between perpetrators of death and clinicians and researchers: It is not only

that perpetrators ¢nd it di⁄cult to share their moral hesitations; professionals

also prefer not to ask and not to listen. The ‘‘double arrow’’ allows both the

perpetrator and the mental health professional to maintain their silence

(Bar-On, 1989; Bar-On & Charny, 1988).

PTSDAmong Reckless Drivers

341

Drivers who injure others evoke complex reactions. On the one hand, it is

impossible to ignore the terrible consequences of their carelessness; on the

other hand, the act occurred accidentally. It would seem that all drivers could

¢nd themselves in a similar situation, and no one is immune to being involved

in a fatal accident. In meeting a perpetrator of the Holocaust, for example,

people may think that they are ‘‘di¡erent’’ and would not have behaved like

the Nazis. But there is no such‘‘immunity’’ for reckless drivers.

Some claim that relating to perpetrators as victims is immoral. For exam-

ple, Alan Young (1995) objects to viewing a¥icted Vietnam veterans as vic-

tims. In his opinion, the victim label legitimizes the war and promotes

mobilization to help. He sees these soldiers as war criminals who committed

terrible acts. A possible result of such a claim is the delegitimization of

various traumatized populations (Witzum et al., 1996;Young, 1995) including

perpetrators such as reckless drivers.

Although the ¢ndings of this study are limited because it involved a small

sample and a retrospective design, our results point to the need to draw clin-

ical and research attention to populations at risk and in distress who have not

received appropriate professional attention as a result of social and legal

processes.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders

(4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barash, R. K. (1996). Factors associated with two facets of altruism inVietnamWar veterans

with post-traumatic stress disorder. Dissertation Abstracts International, 56(11-B), 6453.

Bar-On, D. (1989). Legacy of silence: Encounters with children of theThird Reich. Cambridge, MA:

Harvard University Press.

Bar-On, D. & Charny, I. W. (1988). Children of Holocaust perpetrators: How do they form

their own ‘‘moral self ’’? IsraelJournal of Psychology, 1, 29^38.

Blanchard, E. B., Hickling, E. J., & Taylor, A. E. (1991). The psychophysiology of motor

vehicle accident related posttraumatic stress disorder. Biofeedback & Self-Regulation, 16,

449^458.

Bryant, R. A. & Harvey, A. G. (1996). Initial posttraumatic stress response following motor

vehicle accidents. Journal ofTraumatic Stress, 9, 223^234.

Fatzinger, T. A. (1997). E¡ects of therapist self-disclosure on client perceptions of the ther-

apeutic alliance and session impact. Dissertation Abstracts International, 58(6-B), 3313.

Feinstein, A. & Dolan, R. (1991). Predictors of post-traumatic stress disorder following phy-

sical trauma: An examination of the stressor criterion. Psychological Medicine, 21, 85^91.

Foeckler, M. M., Garrard, F. H.,Williams, C. C.,Thomas, A. M., & Jones,T. J. (1978).Vehicle

drivers and fatal accidents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 8, 174^182.

342

T. Lowinger and Z. Solomon

Frieze, I. H., Hymer, S., & Greenberg, M. S. (1987). Describing the crime victim: Psycholo-

gical reactions to victimization. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 18, 299^315.

Gersons, B. P. R. (1989). Patterns of PTSD among police o⁄cers following shooting incidents:

A two-dimentional model and treatment implications. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 2, 247^

259.

Gilbert, P. (1998). Shame and humiliation in the treatment of complex cases. In N. Tarrier

et al. (Eds.), Treating complex cases: The cognitive behavioural therapy approach (pp. 241^271).

Chichester, England: Wiley.

Glover, H. (1984). Survival guilt and the Vietnam veteran. Journal of Nervous and Mental Dis-

orders

, 172, 393^397.

Goldberg, L. & Breznitz, S. (Eds.). (1982). Handbook of stress: Theoretical and clinical aspects.,

NewYork: Free Press.

Green, B. L., Wilson, J. P., & Lindy, J. D. (1985). Conceptualizing PTSD: A psychological

framework. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Trauma and its wake (pp. 53^69). New York:

Brunner=Mazel.

Haley, S. A. (1978). Treatment implications of post-combat stress response syndromes for

mental health professionals. In C. R. Figley (Ed.), Stress disorders among Vietnam veterans:

Theory, research and treatment

(pp. 254^267). NewYork: Brunner=Mazel.

Hendin, H. & Haas, A. P. (1984).Wounds of war:The psychological aftermath of combat inVietnam.

NewYork: Basic Books.

Jackley, P. A. (2001). Shame-based identity and chronic post-traumatic stress disorder in

help-seeking combat veterans. Dissertation Abstracts International, 61(9B), 4986.

Jano¡-Bulman, R. (1989). Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: Applications

of scheme construct. Social Cognition, 7, 113^136.

Jano¡-Bulman, R. & Wortman, C. B. (1977). Attributions of blame and coping in the ‘‘real

world’’: Severe accident victims react to their lot. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

35

, 351^363.

Kessler, R. C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., & Hughes, M. (1995). Posttraumatic stress disorder

in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52, 1048^1060.

Kinzie, D. J. (1989). Post-traumatic stress disorder. In J. I. Kaplan & D. J. Sadock (Eds.).,

Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry

. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins Co.

Kogan, I. (1990). A journey to pain. InternationalJournal of Psychological Analysis, 71, 629^639.

Koren, D., Arnon, I., & Klein, E. (1999). Acute stress response and post-traumatic stress

disorder in tra⁄c accident victims: A one-year perspective, follow up study. American

Journal of Psychiatry

, 156, 367^373.

Kubany, E. S., Abueg, F. R., Owens, J. A., Brennan, J. M., Kaplan, A. S., & Watson, S. B.

(1995). Initial examination of a multidimensional model of trauma-related guilt: Appli-

cations to combat veterans and battered women. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral

Assessment

, 17, 353^376.

Kugler, K. & Jones,W. H. (1992). On conceptualizing and assessing guilt. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology

, 62, 318^327.

Lifton, R. J. (1967). Death in life:The survivors of Hiroshima. NewYork: Random House.

Lifton, R. J. (1973). Home from the war:Vietnam veterans. Neither victims nor executioners. NewYork:

Simon & Schuster.

Lobel, T. E. & Yahia, M. (1985). Guilt feelings and locus of control of concentration camp

survivors. InternationalJournal of Social Psychiatry, 153, 810^818.

PTSDAmong Reckless Drivers

343

Malt, U. (1988). The long-term psychiatric consequences of accidental injury: A longitudinal

study of 107 adults. BritishJournal of Psychiatry, 153, 810^818.

Mayou, R. (1992). Psychiatric aspects of road tra⁄c accidents. International Review of Psy-

chiatry

, 4, 45^54.

Mayou, R. A., Bryant, B., & Duthie, R. (1993). Psychiatric consequences of road tra⁄c

accidents. British MedicalJournal, 307, 647^651.

Parente, D. (2001). Implicit and explicit memory in junior high and college students. Psycho-

logical Reports

, 88, 313^315.

Parker, N. (1977). Accident litigants with neurotic symptoms. Medical Journal of Australia, 3,

318^321.

Sayag, R. (2000). Course and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder following road accidents: Pro-

spective research

. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Tel Aviv.

Sigel, S. (1956). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. NewYork: McGraw-Hill.

Solomon, Z. (1993). Combat stress reaction:The enduring toll of war. NewYork: Plenum Press.

Solomon, Z., Benbenishty, R., Neria,Y., Abramowitz, M., Ginzburg, K., & Ohry, A. (1993).

Assessment of PTSD: Validation of the revised PTSD Inventory. IsraelJournal of Psychiatry

and Related Sciences

, 30, 110^115.

Stratton, J. G., Parker, D. A., & Snibbe, J. R. (1986). Post-traumatic stress: Study of police

o⁄cers involved in shootings. Psychological Reports, 55, 127^131.

Street, A. E. & Arias, I. (2001). Psychological abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder in

battered women: Examining the roles of shame and guilt.Violence and Victims, 16, 65^78.

Tangney, J. P. (1990). Assessing individual di¡erences in proneness to shame and guilt:

Development of the Self-Conscious A¡ect and Attribution Inventory. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology

, 59, 102^111.

Tangney, J. P. (1991). Moral a¡ect: The good, the bad, and the ugly. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology

, 61, 598^607.

Tangney, J. P. (1992). Situational determinants of shame and guilt in young adulthood.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin

, 18, 199^206.

Tangney, J. P., Wagner, P., & Gramzow, R. (1989).TheTest of Self-Conscious A¡ect. Fairfax,VA:

George Mason University.

Witzum, E., Goodman,Y., & Shalev, A. (1996). PTSD: Reality or imagination? IsraelJournal

of Psychotherapy

, 11, 19^26.

Wolman, C. B. (1973). Dictionary of behavioral science. NewYork: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Young, A. (1995). Reasons and causes for post-traumatic stress disorder. Transcultural

Psychiatric Research Review

, 32, 287^298.

Zahava Solomon, PhD, is the director of the Adler Research Center and professor of

Psychiatric epidemiology and social work at Tel Aviv University, Israel. She has pub-

lished over 200 scienti¢c articles and 6 books on man-made psychological trauma. Her

work focuses on war, captivity, the Holocaust, and terror. She is the recipient of

numerous grants and awards, including the ISTSS Laufer award for outstanding sci-

enti¢c achievement in the ¢eld of PTSD.

Tamar Lowinger works as a social worker in a psychiatric hospital and has worked

with reckless drivers inthe past. Shereceivedboth her B.A. and her M.A. fromthe School

of SocialWork atTel Aviv University, Israel.This article is based on her master’s thesis.

344

T. Lowinger and Z. Solomon

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Shame, Guilt, and identity An Essay

from guilt to shame auschwitz and after

Quality of life and disparities among long term cervical cancer suvarviors

Love and Sex Among the Inverteb Pat Murphy

Death and Designation Among the Michael Bishop

Cairns D , Honour and Shame Modern Controversies and Ancient Values

Carolyn J Hill, Harry J Holzer, Henry Chen Against the Tide, Household Structure, Opportunities, an

Shame and Guilt there is a way out v0 3

Embedded Linux Kernel And Drivers

A drunk bus driver and a?d?cident

[32] Synergism among flavonoids in inhibiting platelet aggregation and H2O2 production

Good?d and Ugly Drivers

Ir2111 High Voltage High Speed Power Mosfet And Igbt Driver

Natural Variability in Phenolic and Sesquiterpene Constituents Among Burdock

Embedded Linux Kernel And Drivers

Between Hope and Guilt

Variations in Risk and Treatment Factors Among Adolescents Engaging in Different Types of Deliberate

więcej podobnych podstron