Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

Published online 25 February 2010 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/cpp.684

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Dialectic Behavioural Therapy Has

an Impact on Self-Concept Clarity

and Facets of Self-Esteem

in Women with Borderline

Personality Disorder

Stefan Roepke,

1

* Michela Schröder-Abé,

2

Astrid Schütz,

2

Gitta Jacob,

3

Andreas Dams,

1

Aline Vater,

1

Anke Rüter,

1

Angela Merkl,

1

Isabella Heuser

1

and Claas-Hinrich Lammers

1

1

Department of Psychiatry, Charité-University Medicine Berlin, Campus

Benjamin Franklin, Berlin, Germany

2

Department of Psychology, Personality Psychology and Assessment,

Chemnitz University of Technology, Chemnitz, Germany

3

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Freiburg Medical

Centre, Hauptstrasse, Freiburg, Germany

Identity disturbance and an unstable sense of self are core criteria of

borderline personality disorder (BPD) and signifi cantly contribute

to the suffering of the patient. These impairments are hypothesized

to be refl ected in low self-esteem and low self-concept clarity. The

objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of an inpatient dia-

lectic behavioral therapy (DBT) programme on self-esteem and self-

concept clarity. Forty women with BPD were included in the study.

Twenty patients were treated with DBT for 12 weeks in an inpa-

tient setting and 20 patients from the waiting list served as controls.

Psychometric scales were used to measure different aspects of self-

esteem, self-concept clarity and general psychopathology. Patients in

the treatment group showed signifi cant enhancement in self-concept

clarity compared with those on the waiting list. Further, the scales

of global self-esteem and, more specifi cally, the facets of self-esteem

self-regard, social skills and social confi dence were enhanced signifi -

cantly in the intervention group. Additionally, the treatment had a

signifi cant impact on basic self-esteem in this group. On the other

hand, the scale of earning self-esteem was not signifi cantly abased

in patients with BPD and did not show signifi cant changes in the

intervention group. Our data provide preliminary evidence that DBT

has an impact on several facets of self-esteem and self-concept clarity,

and thus on identity disturbance, in women with BPD. Copyright ©

2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

* Correspondence to: Dr Stefan Roepke, Department of Psychiatry, Charité-University Medicine Berlin, Campus Benjamin

Franklin, Berlin, Germany.

E-mail: stefan.roepke@charite.de

Impact of DBT on identity disturbance in BPD

149

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

Key Practitioner Message:

• Self-concept clarity, which refers to the BPD criterion identity dis-

turbance, and facets of self-esteem, are impaired in patients with

BPD compared with reference data from healthy controls.

• Our study replicates that depressive symptoms and general psycho-

pathology are improved after a 12-week DBT programme in BPD

patients compared with a waiting list.

• The 12-week inpatient DBT treatment programme shows signifi cant

enhancement in self-concept clarity and facets of self-esteem com-

pared with the waiting list.

• Thus, in BPD patients, self-esteem and the diagnostic criteria iden-

tity disturbance, captured by self-concept clarity, can be infl uenced

with short-term psychotherapy.

Keywords:

Self-Esteem, Self-Concept Clarity, Borderline Personality

Disorder, Dialectic Behavioural Therapy, Identity Disturbance

INTRODUCTION

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is character-

ized by a pervasive pattern of instability in inter-

personal relationships, self-image and affect as

well as by marked impulsivity (APA, 1994). Iden-

tity disturbance and an unstable sense of self con-

stitute one of the nine criteria for BPD in DSM-IV

(APA, 1994). The criterion of identity disturbance

is based on the psychoanalytic theory of identity

diffusion in borderline personality organization

(Kernberg, 1975). There is little empirical research

on the criterion of identity disturbance in BPD. The

few existing studies focus on whether this crite-

rion is specifi c to BPD (for a review see Jørgensen,

2006). In our study, we empirically measured

aspects of identity and related constructs of the

‘self’ in BPD patients (see also Schröder-Abé et al.,

under submission), and empirically assessed the

impact of an evaluated psychotherapeutic treat-

ment programme for BPD on these measures.

As existing theories vary in describing the term

‘self’, we followed the concept as defi ned by

Baumeister (1999; see Schütz, 2005, for a review)

describing the self-concept as ‘your ideas about

yourself’, identity as ‘who you are’, and self-esteem

(SE) as ‘how you evaluate yourself’. More specifi -

cally, self-concept is defi ned as a cognitive schema,

an organized knowledge structure that contains

traits, values and episodic and semantic memories

about the self, and that controls the processing of

self-relevant information (e.g., Greenwald & Prat-

kanis, 1984). Self-concept clarity (SCC) overlaps

with the construct of identity and refers to the

structural aspect of the self-concept: the extent to

which the contents of an individual’s self-concept

are clearly and confi dentially defi ned, internally

consistent and temporally stable (Campbell et al.,

1996). However, identity comprises more complex

sets of elements than SCC. They are rather dif-

fi cult to assess empirically (Campbell et al., 1996).

Thus, SCC is characteristic of people’s beliefs about

themselves and may be considered an empirically

assessable aspect of identity (Campbell et al., 1996).

Self-esteem is the evaluative dimension of the self-

concept, the ‘positivity of a person’s evaluation of

self’ (Baumeister, 1998). Various constructs are used

to describe different aspects of SE. In terms of ana-

lytical theories, basic self-esteem can be compared

with an individual’s ego-integrated libidinous and

aggressive drives as well as their derivates (Forsman

& Johnson, 1996). The concept is free of references

to perceived skills, competencies, family relations

or others’ appraisal. Instead, it refers to attitudes

that are regarded as the end result of the success-

ful merging of libidinous and aggressive emotions

into the ego, for example, warm and gratifying rela-

tions with others, the freedom to experience and

express emotions, including sexual impulses and a

sense of security and integrity (Forsman & Johnson,

1996). By contrast, earning self-esteem is defi ned

as the need to earn SE by competences and others’

appraisals (Forsman & Johnson, 1996), which means

that earning SE represents a less-adaptive aspect of

SE. Individuals high in earning self-esteem experi-

ence their sense of self-esteem as being conditional,

especially upon competence and success, and upon

the praise and approval of others. They strive hard

to do well and to be perfect (Forsman & Johnson,

1996). The hierarchical facet model of SE devel-

oped by Shavelson, Hubner and Stanton (1976) and

advanced by Fleming and Courtney (1984) states

that SE is a multidimensional construct. With an

additional subdivision of social SE into social con-

150

S. Roepke et al.

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

fi dence and social skills, Schütz and Sellin (2006)

presented a modifi ed version of the Fleming and

Courtney (1984) model and differentiated six

factors: self-regard, social skills, social confi dence,

performance SE, physical appearance and physi-

cal abilities. Measures of SE have several clinical

implications. SE is positively related to indicators of

subjective well-being and psychological health (see

Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003, for

a review). High SE is associated with various posi-

tive outcomes such as optimism (Taylor & Brown,

1988), life satisfaction (e.g., Diener & Diener, 1995)

and low levels of depression (e.g., Tennen & Herz-

berger, 1987; Watson, Suls, & Haig, 2002). Further-

more, emotional instability, which is characteristic

of BPD (Ebner-Priemer et al., 2007), is negatively

related to SE (Judge, Erez, Bono, & Thoresen, 2002;

Robins, Hendin, & Trzesniewski, 2001). In addi-

tion, individuals with high SE are less prone than

others to experience stress and negative affect when

confronted with negative events (Brown & Dutton,

1995; DiPaula & Campbell, 2002). Interestingly, BPD

patients show more emotional reactivity to daily life

stress (Glaser, Mengelers, & Myin-Germeys, 2007).

Only a few studies have examined SCC and SE

in relation to features of personality disorders.

However, in normal samples, low SCC has been

shown to be related to dysfunctional personal-

ity characteristics, such as high neuroticism, low

agreeableness and low SE (Baumeister, 1998;

Campbell, 1990). Very little empirical research

has been done on the self and identity in BPD.

Wilkinson-Ryan and Westen (2000) have found a

pattern of identity disturbance that distinguishes

BPD patients from other patients and normal con-

trols. In another study, BPD patients’ mood has

been correlated with a negative view of themselves

(De Bonis, De Boeck, & Lida-Pulik, 1998). Only one

study so far has examined SCC in BPD patients.

The authors reported lower SCC in BPD patients

as compared with the general population (Pollock,

Broadbent, Clarke, Dorrian, & Ryle, 2001). In one

of our own studies, we have found the same result

of lower SCC and lower SE in women with BPD

(Schröder-Abé et al., under submission).

The present study was aimed at investigating

effects of dialectic behavioral therapy (DBT) on SE

and SCC in women with BPD. Studies investigat-

ing psychotherapeutic interventions to improve

SE in various mental disorders have yielded con-

tradictory results. Two studies (Chen, Lu, Chang,

Chu, & Chou, 2006; Knapen et al., 2005) found cog-

nitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to improve SE

in depressed patients, whereas two other studies

(Hyun, Chung, & Lee, 2005; Reynolds & Coats,

1986) found no signifi cant improvement of SE in

depressed patients. To our knowledge, however,

the possible improvement of SE and SCC through

psychotherapeutic intervention in patients with

BPD has not been studied yet. DBT was specifi cally

developed as an outpatient treatment programme

for chronically suicidal individuals meeting the cri-

teria for BPD (Linehan, Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon,

& Heard, 1991; Linehan, Heard, & Armstrong,

1993). To date, DBT has demonstrated effi cacy in

a number of randomized controlled trials for BPD

in inpatient and outpatient settings (Lynch et al.,

2007). DBT treatment strategies aim to enhance

emotion regulation by increasing awareness and

acceptance of the emotional experience, and by

changing negative affect through new learning

experiences (Linehan et al., 1993). The treatment

aims at reducing dysfunctional behaviour in four

high-priority target areas: suicidal behaviours,

intentional self-injuries, behaviours that interfere

with treatment and behaviours that prolong hospi-

talization. Randomized clinical trials revealed that

DBT reduces incidences of parasuicide and medi-

cally severe parasuicides, improves adherence to

individual therapy, and diminishes inpatients’

psychiatric days (Linehan et al., 1993).

Based on theoretical considerations and previous

empirical data, we hypothesize that DBT utilizes

different techniques that improve SE, clarify the

self-concept and thus improve identity disturbance

in BPD. Accordingly, we expected improved SCC

and SE and an overall reduction of symptoms after

12 weeks of inpatient DBT treatment in patients

with BPD.

METHOD

Participants

Forty-fi ve women with BPD were consecutively

enrolled and participated in the study. Five patients

dropped out of the study and were excluded from

analysis, two from the DBT group and three from

the waiting list group. Data from 20 patients who

completed a 12-week inpatient DBT programme

were compared with data from 20 patients from

a waiting list. All BPD patients from the interven-

tion group (DBT) were on a waiting list before

participating in the DBT programme. Patients from

the control group (waiting list) were not included

in the DBT-treatment arm of the study, but com-

pleted the DBT programme after study participa-

tion. Also, patients from the control group (waiting

Impact of DBT on identity disturbance in BPD

151

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

list) continued treatment as usual in an outpatient

setting while waiting for the DBT programme.

Treatment as usual was not assessed more specifi -

cally. Sociodemographic characteristics, psycho-

tropic medication and comorbidity on axis I and II

of the sample are presented in Table 1.

All participants met the DSM-IV (APA, 1994)

criteria for BPD on the Structured Clinical Inter-

view for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (SCID-II;

First, Spitzer, Gibbon, Williams, & Benjamin, 1997;

Fydrich, Renneberg, Schmitz, & Witchen, 1997).

Axis I comorbidity was assessed with the Mini

International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI.;

Ackenheil, Stotz-Ingenlath, Dietz-Bauer, & Vossen,

1999; Sheehan et al., 1998). Lifetime diagnosis of

schizophrenia, bipolar I or II disorder, substance

abuse within the last 6 months or mental retardation

were exclusion criteria. Prior psychiatric or psycho-

therapeutic treatment was not assessed systemati-

cally and thus not included in further analyses.

Measures

Questionnaires

Psychometric Scales Assessing Self-Esteem and the

Self-Concept. Facets of self-esteem were measured

using the 32-item Multidimensional Self-Esteem

Scale (MSES; Schütz & Sellin, 2006), the modifi ed

German version of the scale by Fleming and Court-

ney (Fleming & Courtney, 1984). The question-

naire comprises six subscales: self-regard, social

skills, social confi dence, performance SE, physical

appearance and physical abilities. Two of the sub-

scales capture different aspects of SE in social con-

texts: The social skills scale captures the perception

of a person’s own capacity to interact with others,

whereas the social confi dence scale captures the

ability to handle criticism from others. The sub-

scale self-regard captures the emotional compo-

nent of SE, the emotional evaluation of the self.

The performance scale captures the perception of

technical and professional abilities. All subscales

consist of fi ve items, except for self-regard, which

consists of seven items. Additionally, the subscales

are combined to form a Global SE index, which

comprises all subscales. Responses were made on

7-point scales with endpoints labelled not at all (1)

and very much (7) or never (1) and always (7), respec-

tively. Previous research indicated internal con-

sistency reliabilities in a healthy sample between

0.75 and 0.87 (Cronbach’s alpha; Schütz & Sellin,

2006). Values for internal consistency in the present

sample are presented in Table 2. Test–retest reli-

abilities of MSES sum and subscales were between

0.46 and 0.86 (Schütz & Sellin, 2006).

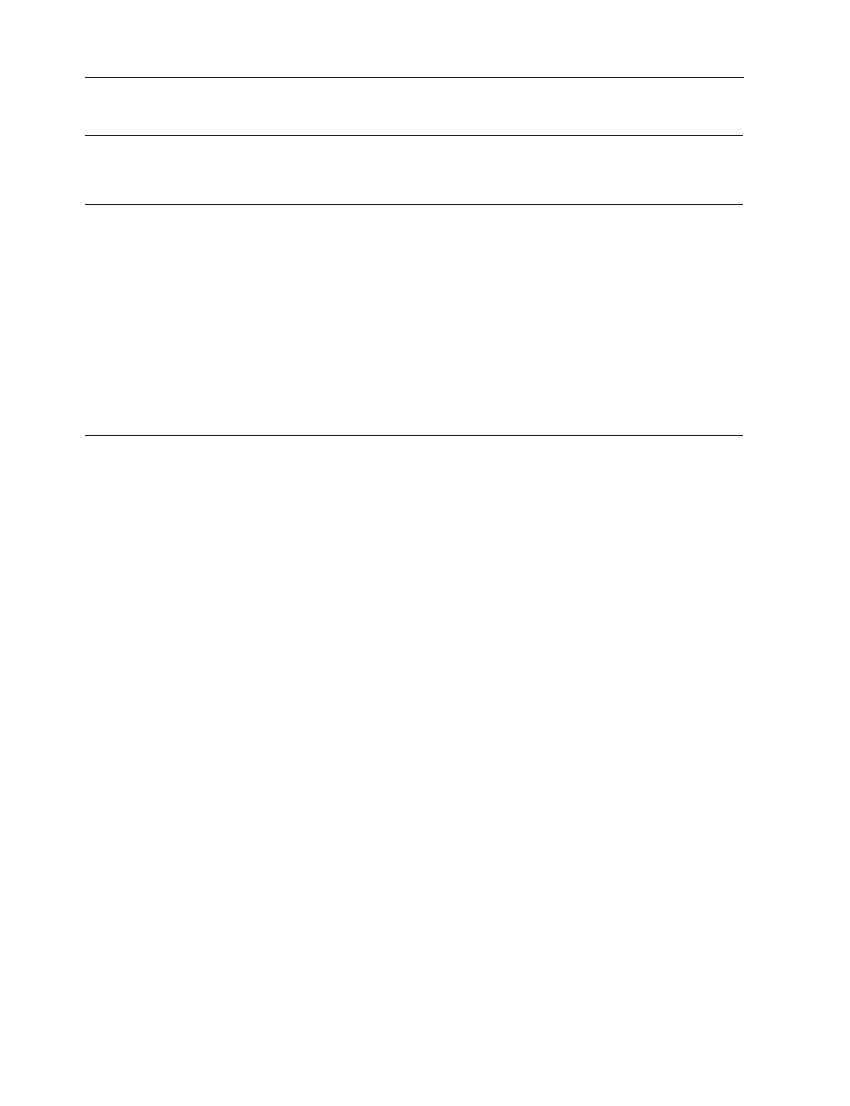

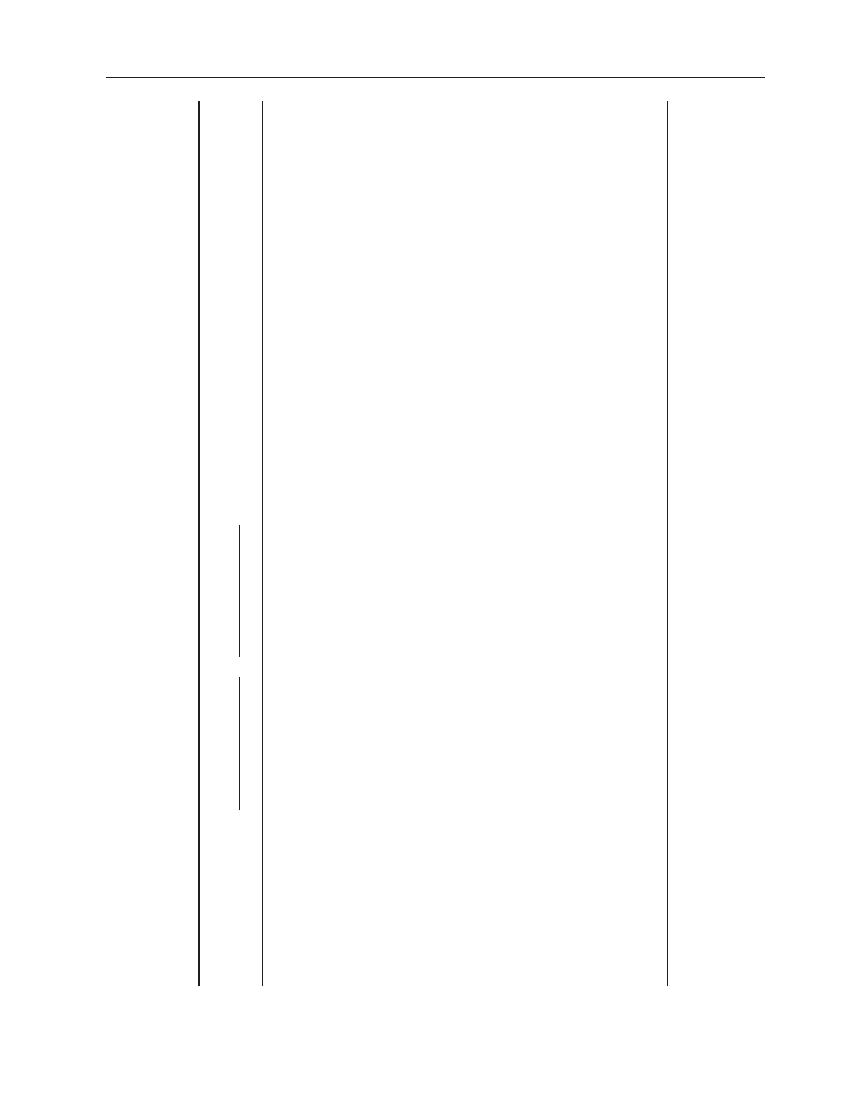

Table 1. Socioedemographic data, psychotropic medication and comorbidity of patients in the intervention group

(DBT) and control group

DBT

CG

t test

M (SD)

M (SD)

Age

27.7 (6.7)

32.5 (7.5)

t

= −2.1, df = 38, p = 0.04*

frequency (%)

frequency (%)

χ

2

-tests

Psychotropic med.

16 (80)

14 (70)

χ

2

= 0.53, df = 1, p = 0.47

SSRI

16 (80)

11 (55)

χ

2

= 2.85, df = 1, p = 0.09

aNL

6 (30)

7 (35)

χ

2

= 0.11, df = 1, p = 0.74

Axis I

Depression, lifetime

8 (40)

8 (40)

χ

2

= 0.00, df = 1, p = 1

Dysthymia

9 (45)

8 (40)

χ

2

= 0.10, df = 1, p = 0.75

PTSD

6 (30)

5 (25)

χ

2

= 0.13, df = 1, p = 0.72

Substance abuse

6 (30)

5 (25)

χ

2

= 0.13, df = 1, p = 0.72

Eating disorder

10 (50)

5 (25)

χ

2

= 2.67, df = 1, p = 0.10

Axis II

Avoidant PD

5 (25)

8 (40)

χ

2

= 1.03, df = 1, p = 0.31

Dependent PD

3 (15)

1 (5)

χ

2

= 1.11, df = 1, p = 0.29

Paranoid PD

1 (5)

3 (15)

χ

2

= 1.11, df = 1, p = 0.29

Histrionic PD

1 (5)

0 (0)

χ

2

= 1.03, df = 1, p = 0.31

* p

< 0.05.

M

= mean. SD = standard deviation. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. PD = Personality Disorder. SSRI = selective serotonin

reuptake inhibitor. aNL

= atypical neuroleptic. DBT = DBT intervention group (n = 20). CG = control group (n = 20).

152

S. Roepke et al.

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

Basic self-esteem was assessed by the 38-item

Basic Self-Esteem Scale (BSE; Forsman & Johnson,

1996; e.g., ‘I can freely express what I feel’).

Responses were made on a 5-point scale, ranging

from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Cron-

bach’s alpha internal consistency reliability was

reported as 0.92 in the validation study of the scale

(Forsman & Johnson, 1996). Internal consistency of

the scale in the present study is reported in Table 2.

Earning self-esteem was measured by the

28-item Earning Self-Esteem (ESE) Scale (Forsman

& Johnson, 1996; e.g., ‘If people say that they like

me, my self-esteem is strengthened quite a lot’).

Responses were made on a 5-point scale, ranging

from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Inter-

nal consistency reliability was reported as 0.76

(Cronbach’s alpha) in the validation study of the

scale (Forsman & Johnson, 1996). Values for the

reliability of the present sample are reported in

Table 2. The test–retest reliabilities of ESE (0.723)

and BSE (0.735) were calculated from the control

group of the present study as data were not pro-

vided in the validation study of the scales (Forsman

& Johnson, 1996).

Self-concept clarity (SCC) was measured using

the German version of the 12-item Self-Concept

Clarity Scale (Campbell et al., 1996; Stucke, 2002).

Participants responded to each item using a 5-point

scale with endpoints 1 (strongly disagree) and 5

(strongly agree). Internal consistency reliability was

reported as 0.86 (Cronbach’s alpha) on average in

the validation study of the scale (Campbell et al.,

1996). Reliability of the scale in the present sample

is reported in Table 2. Test–retest reliability of the

scale was reported as 0.79 in the validation study

of the scale (Campbell et al., 1996).

Psychometric Scales Assessing Severity of Psycho-

pathological Symptoms. The German version of the

21-item Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck,

Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961; Hautz-

inger, Bailer, Worall, & Keller, 1994) was employed

to assess severity of depression. Test–retest reli-

ability of the BDI was reported as 0.93 (Beck, Steer,

Ball, & Ranieri, 1996).

The SCL-90-R was used to assess current subjec-

tive experience of symptoms (Franke, 1995). The

Global Severity Index (GSI), which comprises all

subscales of the SCL-90-R, was used to measure

global psychopathological impairment. Responses

were made on 5-point scales with end points

labelled not at all (0) and very much (4). Test–retest

reliability of the GSI of the SCL-90-R was reported

as 0.92 (Franke, 1995).

Procedure

The study was conducted at the Borderline

Research Unit of the Department of Psychiatry

and Psychotherapy, Charité, University Medicine

Berlin, Campus Benjamin Franklin. The interven-

tion group was treated with a 12-week DBT pro-

gramme following Linehan’s DBT manual adapted

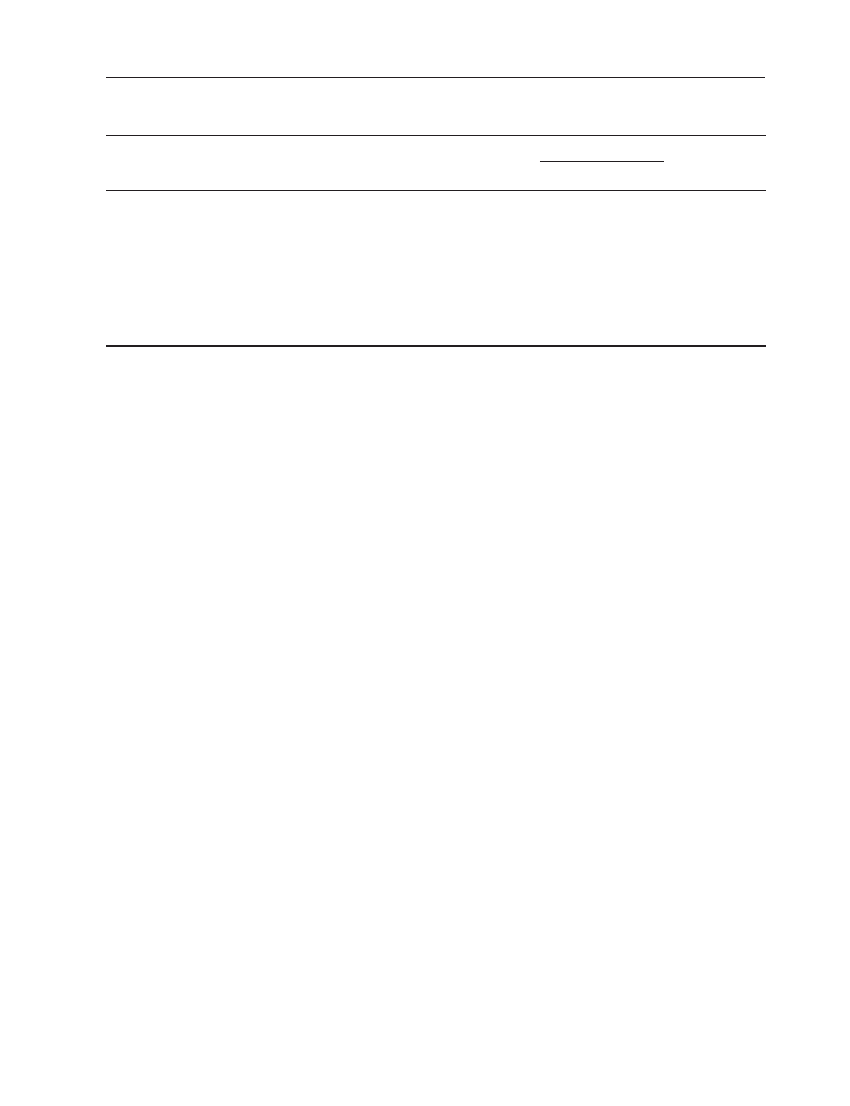

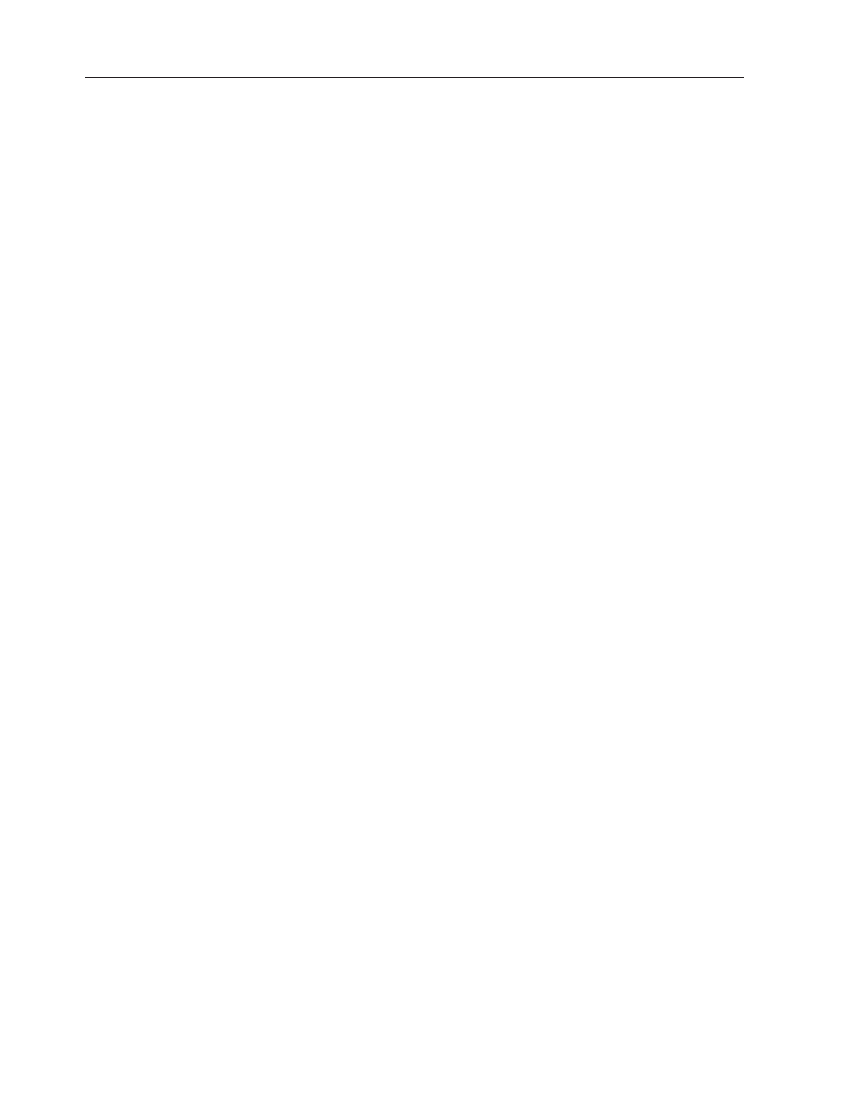

Table 2. Self-esteem and self-concept clarity in the total group of patients with BPD prior to intervention and

comparison with reference data from healthy samples

Chronbach’s

alpha

Study group,

n

= 40

M (SD)

Reference data

d-value

n

M (SD)

SCC

0.76

1.98 (0.62)

126

†

3.74 (0.94)

−2.21*

BSE

0.72

2.21 (0.34)

26

‡

3.59 (0.39)

−3.77*

ESE

0.81

3.64 (0.44)

26

‡

3.51 (0.36)

0.32, n.s.

††

MSES global SE

0.88

2.54 (0.72)

214

§

4.74 (0.95)

−2.61*

MSES self-regard

0.79

2.53 (0.84)

231

§

5.21 (1.11)

−2.72*

MSES social skills

0.78

2.52 (1.08)

234

§

5.01 (1.30)

−2.08*

MSES social confi dence

0.84

2.31 (1.07)

227

§

5.65 (1.42)

−2.66*

MSES performance SE

0.72

3.02 (1.18)

225

§

5.08 (1.02)

−1,87*

MSES physical appearance

0.88

2.24 (1.16)

231

§

4.51 (1.34)

−1.81*

MSES physical abilities

0.73

2.64 (1.16)

228

§

3.97 (1.36)

−1.05*

*

= p < 0.05.

†

Data from the total sample in Stucke (2002).

‡

Data from the healthy control group in Schröder-Abé et al. (unpublished data).

§

Data from the female healthy norm sample in Schütz and Sellin (2006).

††

Higher ESE values indicate a less stable self-esteem, Cronbach’s alpha: data from both groups before treatment/waiting list.

M

= mean. SD = standard deviation. SCC = Self-concept clarity. BSE = Basic Self-Esteem Scale. ESE = Earning Self-Esteem Scale.

MSES

= Multidimensional Self-Esteem Scale.

Impact of DBT on identity disturbance in BPD

153

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

for inpatient treatment (Bohus et al., 2004). The

inpatient DBT programme included the following

components: individual therapy (1 hour/week),

group skills training (3 hours/week), mindfulness

groups (2 hours/week), group psychoeducation (1

hour/week), peer group meetings (2 hours/week),

individual body-oriented therapy (1.5 hours/

week) and therapist team consultation meetings (2

hours/week). The individual therapy, skills train-

ing, and therapist team consultation meetings fol-

lowed Linehan’s DBT manual (Linehan et al., 1993).

The psychoeducation group included instructions

in Linehan’s bio-behavioural theory of BPD com-

bined with information on theory and research

on BPD. The mindfulness group was an extended

version of the mindfulness segment of DBT skills

training. The body-oriented therapy included

education classes about psychomotor interaction

and individually tailored exercises focusing on

improvement of the body concepts. The therapists

and the staff were trained and supervised regu-

larly by a senior DBT trainer (Christian Stiglmayr).

All DBT therapists were certifi ed psychologists or

psychiatrists. All completed or were in the fi nal

course of DBT certifi cation. DBT certifi cation addi-

tionally included 96 hours of theory training in

DBT, at least one supervised therapy case (for at

least 1 year), leading a supervised skills group for

at least 6 months and a fi nal oral examination by a

senior DBT therapist.

Structured interviews (SCID II and MINI)

were administered by trained, master-level psy-

chologists, and confi rmed by a clinical inter-

view performed by the last author (CHL, senior

psychiatrist).

Patients from the intervention group adminis-

tered all self-report scales at two different times:

at admission for the 12-week DBT programme

and after 10 weeks of DBT, to avoid effects due to

hospital discharge. Patients in the control group

were also assessed twice with approximately 10

weeks in between (M

= 9.7, SD = 3.6) while they

were waiting for DBT. The study was approved by

the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine

of the Charité-University Medicine Berlin. Written

informed consent was obtained from all patients

before they entered the study.

Statistical Analyses

All analyses were conducted with the Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences SPSS, version 14.0

(SPSS, Chicago, USA). Baseline differences between

patients and the control group were analyzed with

independent t tests or chi-square tests when appro-

priate. Time and group effects were calculated with

ANCOVAs. The signifi cance level in all of the tests

was set at 0.05 (two-tailed). Effect size d for baseline

variables and references for healthy subjects from

the literature were calculated according to Cohen

(1977). Effect sizes of main effects and interactions

for ANCOVAs were reported as eta-squared. Clini-

cal signifi cance was calculated with the reliable

change index (RCI; Jacobson & Truax, 1991). RCI

>

1.96 was considered improvement.

RESULTS

Self-Concept Clarity

Women with BPD showed signifi cantly impaired

SCC compared with reference data from healthy

subjects (Table 2). The ANCOVA model for SCC

with age as a covariate revealed a signifi cant inter-

action effect between time and group, indicating

signifi cant improvement of SCC in the interven-

tion group (Table 3), but no signifi cant changes

in the waitlisted control group. The effect size for

SCC was the largest of all variables measured in

the present study. Fifteen out of 20 patients (75%)

improved as calculated by the RCI.

Self-Esteem

Measures of basic self-esteem and all six facets of

self-esteem from the MSES scale were signifi cantly

lower in the BPD sample than in healthy controls

(Table 2). The ANCOVA model for BSE revealed

a signifi cant interaction effect between group and

time, indicating signifi cant improvement in the

intervention group (Table 3), but no signifi cant

changes in the waitlisted control group. Seven out

of 20 patients (35%) improved in BSE (according

to the RCI). The ANCOVA model for the MSES

global score and the six subscales showed signifi -

cant interactions of group and time for the global

score and the subscales of self-regard, social

skills and social confi dence, indicating signifi cant

improvement in the global score and the men-

tioned subscales in BPD patients who had been

treated with DBT. As calculated by the RCI: Eight

(40%) patients improved on the global score, six

(30%) on the self-regard scale, seven (35%) on the

social skills scale, nine (45%) on the social confi -

dence scale, two (10%) on the performance scale,

two (10%) on the physical appearance scale, three

(15%) on the physical abilities scale of the MSES

out of the 20 subjects in the intervention group.

154

S. Roepke et al.

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

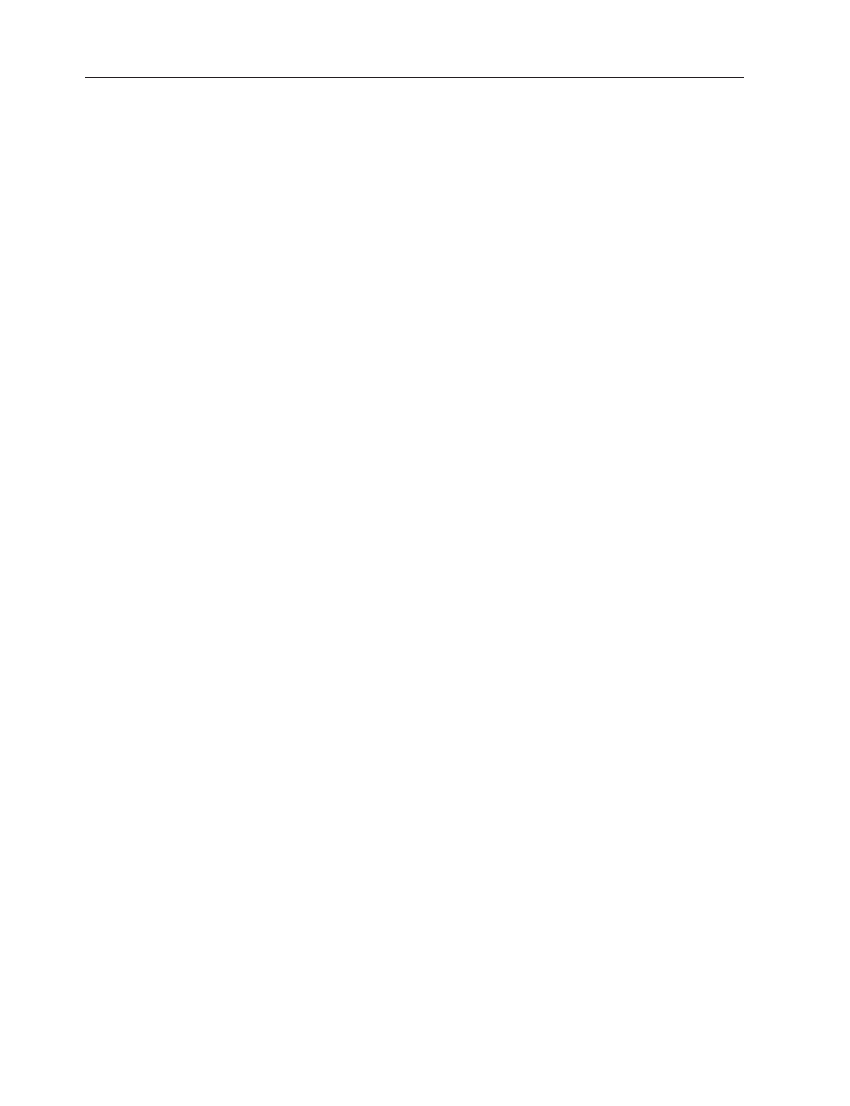

T

able 3.

Means and standar

d deviations of all outcome variables and

ANCOV

A

r

esults with all outcome measur

es as dependent varia

bles and age as

covariate

Pr

e

M (SD)

Post

M (SD)

ANCOV

A

IG

CG

IG

CG

Main ef

fect gr

oup

Main ef

fect time

Interaction gr

oup*time

SCC

1.95 (0.64)

2.02 (0.60)

3.35 (1.92)

1.92 (0.67)

F

=

18.0;

df

=

1, 36;

p

< 0.001**,

η

p

2

=

0.33

F

=

0.02;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 0.89,

η

p

2

=

0.001

F

=

30.4;

df

=

1, 36;

p

< 0.001**,

η

p

2

=

0.46

BSE

2.21 (0.34)

2.20 (0.36)

2.60 (0.49)

2.18 (0.40)

F

=

2.44;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 1.22,

η

p

2

=

0.06

F

=

0.16;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 0.69,

η

p

2

=

0.01

F

=

14.0;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 0.001*,

η

p

2

=

0.28

ESE

3.71 (0.41)

3.57 (0.47)

3.60 (0.26)

3.56 (0.50)

F

=

0.67;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.42,

η

p

2

=

0.02

F

=

0.63;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.43,

η

p

2

=

0.02

F

=

2.5;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.12,

η

p

2

=

0.07

MSES global SE

2.46 (0.45)

2.62 (0.92)

2.90 (0.80)

2.45 (0.94)

F

=

0.09,

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.77,

η

p

2

=

0.002

F

=

0.01;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.93,

η

p

2

=

0.00

F

=

9.6;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.004*,

η

p

2

=

0.21

MSES self-r

egar

d

2.62 (0.51)

2.44 (1.08)

2.96 (0.77)

2.24 (1.03)

F

=

1.2;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.28,

η

p

2

=

0.03

F

=

0.19;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.67,

η

p

2

=

0.005

F

=

4.9;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.033*,

η

p

2

=

0.12

MSES social skills

2.49 (1.09)

2.54 (1.09)

3.16 (1.22)

2.51 (1.10)

F

=

0.94;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.34,

η

p

2

=

0.03

F

=

0.29;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.59,

η

p

2

=

0.008

F

=

4.9;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.034*,

η

p

2

=

0.12

MSES social confi

dence

1.99 (0.80)

2.64 (1.23)

2.93 (1.16)

2.57 (1.61)

F

=

0.1

1;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.75,

η

p

2

=

0.003

F

=

0.9;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.77,

η

p

2

=

0.002

F

=

10.0;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.003*,

η

p

2

=

0.22

MSES performance SE

2.86 (0.92)

3.17 (1.40)

2.93 (1.10)

2.75 (1.51)

F

=

0.01;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.92,

η

p

2

=

0.000

F

=

0.07;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.79,

η

p

2

=

0.002

F

=

1.8;

df

=

1, 37;

p

= 0.19,

η

p

2

=

0.045

MSES physical apperar

ence

2.22 (0.96)

2.25 (1.37)

2.59 (1.34)

2.19 (1.16)

F

=

0.02;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 0.89,

η

p

2

=

0.001

F

=

0.92;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 0.34,

η

p

2

=

0.025

F

=

3.3;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 0.076,

η

p

2

=

0.085

MSES physical abilities

2.52 (0.95)

2.75 (1.34)

2.82 (1.38)

2.44 (1.1

1)

F

=

0.002;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 0.97,

η

p

2

=

0.000

F

=

0.6;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 0.45,

η

p

2

=

0.02

F

=

1.6;

df

=

1, 36;

p

= 0.22,

η

p

2

=

0.04

BDI

32.2 (9.23)

33.6 (1

1.5)

20.9 (12.0)

32.7 (1

1.5)

F

=

2.1;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.16,

η

p

2

=

0.06

F

=

6.2;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.02*,

η

p

2

=

0.15

F

=

7.3;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.01*,

η

p

2

=

0.17

SCL-90-R GSI

1.79 (0.52)

1.99 (0.60)

1.29 (0.72)

1.87 (0.76)

F

=

2.5;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.13,

η

p

2

=

0.07

F

=

0.92;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.34,

η

p

2

=

0.03

F

=

7.1;

df

=

1, 35;

p

= 0.01*,

η

p

2

=

0.17

*

p

< 0.05, **

p

< 0.001.

IG

= Intervention gr

oup (

n

=

20). CG

= Contr

ol gr

oup (

n

=

20). M

= mean. SD

= standar

d deviation. SCC

= Self-concept clarity

. BSE

= Basic self-esteem scale. ESE

= Earning

self-esteem scale. MSES

= Multidimensional self-esteem scale. BDI

= Beck depr

ession inventory

. SCL-90-R

= Symptom checklist 90 r

evised. GSI

= Global severity index.

Impact of DBT on identity disturbance in BPD

155

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

Scores of ESE for BPD patients were not signifi -

cantly different from those of the healthy controls

(Table 2). The ANCOVA model for ESE did not

show signifi cant main effects and no interaction

effect between time and group (Table 3), indicating

no signifi cant modifi cation of ESE in either group.

Also, no patient improved as calculated by the RCI

in the intervention group.

Changes in Psychopathology and Depression

Depressive symptoms measured by the BDI and

general psychopathology measured by the GSI

of the SCL-90-R were not signifi cantly different

between the two groups at baseline (Table 3).

The BDI and the GSI of the SCL-90-R showed a

signifi cant interaction effect of time and group

in the ANCOVA model, indicating a signifi cant

improvement after a 10-week DBT programme on

both scales (Table 3), but no signifi cant changes

in the waitlisted control group. Thirteen out of

19 patients (68%) improved as calculated by the

RCI on the BDI scale. On general psychopathol-

ogy measures (GSI), 11 out of 19 patients (58%)

improved as calculated by the RCI.

DISCUSSION

We tested the impact of a 12-week inpatient DBT

programme on SE and SCC of BPD patients. We

had hypothesized that participants treated with

the DBT programme would show (a) an enhan-

cement in SCC, and thus an improvement of

identity disturbance; (b) an enhancement in SE;

and (c) an overall reduction of psychopathological

symptoms.

Within the limitations that are discussed later, all

of our hypotheses were confi rmed. We found that

SCC was signifi cantly enhanced after 10 weeks of

DBT, 75% of patients fulfi lled criteria of clinical

improvement as calculated by the RCI. This result

is of special interest as SCC overlaps with the con-

struct of identity (Campbell et al., 1996), which

indicates that DBT directly improves the degree

of the criterion ‘identity disturbance’, in DSM-IV

(APA, 1994). To our knowledge, the present study

is the fi rst to empirically demonstrate that short-

term psychotherapy is able to improve identity

disturbance in BPD patients.

DBT comprises different strategies that are can-

didates for improving identity disturbance. Thus,

validation strategies can be conceptually under-

stood to enhance the stability of the patient’s

sense of self (Lynch et al., 2006). Validation can

be considered to be steady, self-verifying feedback

from the therapist, thus leading to a perception of

coherence (Lynch et al., 2006, Swann et al., 2003).

Further, analysis and modifi cation of dysfunctional

behaviour (e.g., by chain analysis) and cognitions

(e.g., by dialectic strategies to reduce polarization)

are hypothesized to reduce BPD symptomatology

(Lynch et al., 2006) and probably improve the sense

of self, and thus SCC and identity disturbance. Fur-

thermore, mindfulness, a technique related to the

quality of awareness within a present experience

aims to improve participating and ‘becoming one’

with experience (Chapman & Linehan, 2005) could

be a candidate to improve the experience of coher-

ence and thus identity.

DBT treatment furthermore resulted in a sig-

nifi cant increase in global and basic SE of BPD

patients. Nevertheless, only 35% of patients ful-

fi lled criteria of clinical improvement on the BSE

and 45% of patients on the MSES sum score, as

calculated by the RCI. Differentiating the facets of

SE using the MSES (Schütz & Sellin, 2006), revealed

that only self-regard and the two facets of social SE,

social skills and social confi dence, improved sig-

nifi cantly after 10 weeks of DBT. Clinical improve-

ment of these facets (RCI) was found in 30–45% of

patients in the intervention group. This result sug-

gests that the improvement of global and basic SE

can be mainly attributed to pronounced changes

within the emotional and social domains of SE.

The improvement in social SE can be explained as

an effect of the intensive training of social skills

that BPD patients receive during DBT. Social dys-

function is characteristic of BPD (Hill et al., 2008),

and without social skills it is impossible to main-

tain stable interpersonal relationships, pursue long

term goals or gain self-respect in social situations.

Therefore, an increase of social skills and compe-

tence is an important source of improved SE for

patients with BPD.

Changes in the emotional domain of SE could

be attributed to specifi c techniques used in DBT

as emotion regulation is one central focus in

that therapy and is directly linked to the bioso-

cial theory of BPD (Linehan, 1993). DBT aims to

enhance emotion regulation, and thus, the teaching

of emotion regulation skills is a core intervention

(Linehan, 1993). Further, mindfulness, conceptu-

alized as an internal state for the acquisition of

various emotional and behavioural responses

(Lynch et al., 2006), could infl uence emotional

experience. Findings of activation of brain areas

related to positive affect after mindfulness train-

156

S. Roepke et al.

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

ing point in that direction (Davidson et al., 2003).

Also, validation strategies, as core acceptance

strategies in DBT (Linehan, 1993), possibly reduce

emotional arousal (Lynch et al., 2006). Thus, self-

regard, which is the basic emotional dimension of

SE, may have been improved through the applica-

tion of these techniques in DBT.

The lack of improvement in performance and

physical ability self-esteem may be due to the fact

that DBT does not emphasize aspects related to

performance or physical ability self-concept. As

demonstrated in previous studies (Schröder-Abé

et al., under submission) earning self-esteem was

not signifi cantly impaired in BPD patients com-

pared with healthy controls. Thus, in contrast to

the improvement of global and basic SE, earning

self-esteem was not signifi cantly modifi ed after

DBT. General psychopathology and depressive

symptoms had also improved signifi cantly after

10 weeks of inpatient DBT, which dovetails with

results from previous studies (Bohus et al., 2004;

Linehan et al., 1991). Also, the percentage of

patients that clinically improved due to RCI cri-

teria were comparable to previous results, which

revealed clinical improvement in 45% of patients

after 3 months of inpatient DBT (Kleindienst

et al., 2009).

Besides specifi c DBT techniques as emotion

regulation and mindfulness, one also has to con-

sider the impact of cognitive interventions, which

are part of DBT, on SCC and SE. Self-devaluating

and self-denigrating ideas, which are expressions

of low SE, can be considered the most frequent

cognitions underlying behaviour typical of BPD.

The therapeutic correction of these dysfunctional

cognitions is also part of the DBT programme. On

the one hand, these interventions may clarify the

self-concept of BPD patients; on the other hand,

they may increase SE by reducing self-devaluat-

ing cognitions. The data showing improved SE in

depressed patients after CBT (Chen et al., 2006;

Knapen et al., 2005) argue for a positive impact

of these more general techniques on self-esteem.

Also, the successful completion of DBT therapy

and reduction of BPD symptoms may be consid-

ered general factors that lead to modifi ed SCC

and SE.

Limitations of the Study

One limitation of our study is the lack of random-

ization between the two groups. Further, the inter-

vention group was treated as inpatients, while the

control group spent that time period at home. Thus

we cannot exclude possible effects of hospitaliza-

tion and ‘unspecifi c’ intervention. In both groups,

most patients were on psychotropic medication,

thus we did not include this factor in the statistical

analysis. The effect of concomitant psychotropic

medication has to be assessed in further research.

Also, follow-up data need to be obtained in future

research to prove stability of the improvement

in SE and SCC. Depressive symptoms after DBT

(measured by the BDI) were still higher than in

other comparable studies (Linehan et al., 1993).

This could refl ect general impairment in the study

population, as inpatient programmes are especially

designed for severely disturbed patients. Neverthe-

less, depressive symptoms improved signifi cantly

in the intervention group, and previous studies

have shown that depressive symptoms are related

to low SE (Chen et al., 2006; Knapen et al., 2005),

thus improvements in SE can be directly related

to the reduction of depressive symptoms. Further

research should now provide a more fi ne-grained

analysis of the effect of CBT and specifi c therapies

such as DBT on SCC and SE in patients with BPD

and patients with major depression. Future studies

should also identify specifi c effi ciency factors of

DBT that help to improve SE and SCC in BPD

patients. Also, the impact of other specifi c proto-

coled psychotherapeutic treatments of BPD, e.g.,

transference-focused psychotherapy (Kernberg,

Yeomans, Clarkin, & Levy, 2008), mentalization-

based treatment (Bateman & Fonagy, 2009) and

the systems training for emotional predictability

and problem solving (Blum et al., 2008), on self-

concept clarity and facets of self-esteem needs to

be assessed. Finally, further studies are needed to

replicate our preliminary fi ndings and, even more

importantly, follow-up examinations are needed to

prove stability of the described impact of DBT on

self-concept clarity and facets of self-esteem.

In summary, within the described limitations,

our results indicate that a 12-week inpatient DBT

programme for women with BPD provides clini-

cally signifi cant improvement in SE and SCC.

Thus, the results of the present study argue that in

BPD patients, self-esteem and the diagnostic cri-

teria identity disturbance can be infl uenced with

short-term psychotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Birgit Baumkötter, Sandra Schauen,

Alisa Zukanovic and Martina Schickart for their

Impact of DBT on identity disturbance in BPD

157

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

help with data collection. We thank Mirja Petri

for her comments on an earlier version of the

manuscript.

REFERENCES

Ackenheil, M., Stotz-Ingenlath, G., Dietz-Bauer, A., &

Vossen, A. (1999). Mini International Neuropsychiatric

Interview (MINI), German Version 5.0.0. The develop-

ment and validation of a structured diagnostic psychi-

atric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Psychiatrische

Universitätsklinik, München, Germany.

American Psychiatric Association (APA) (1994). Diagnos-

tic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV.

Washington, DC: Author.

Bateman, A., & Fonagy, P. (2009). Randomized

controlled trial of outpatient mentalization-based

treatment versus structured clinical management for

borderline personality disorder. American Journal of

Psychiatry, 166, 1355–1364.

Baumeister, R. (1999). Self in social psychology: Essential

readings (Key readings in social psychology). Hove:

Psychology Press.

Baumeister, R.F. (1998). The self. In D.T. Gilbert, S.T.

Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds), The Handbook of social psy-

chology (pp. 339–374). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Baumeister, R.F., Campbell, J.D., Krueger, J.I., & Vohs,

K.D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better perfor-

mance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier

lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4,

1–44.

Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., Ball, R., & Ranieri, W. (1996).

Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories -IA and -II

in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assess-

ment, 67, 588–597.

Beck, A.T., Ward, C.H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., &

Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory of measuring depres-

sion. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–571.

Blum, N., St John, D., Pfohl, B., Stuart, S., McCormick, B.,

Allen, J., Arndt, S., & Black, D.W. (2008). Systems train-

ing for emotional predictability and problem solving

(STEPPS) for outpatients with borderline personality

disorder: A randomized controlled trial and 1-year

follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165, 468–478.

Bohus, M., Haaf, B., Simms, T., Limberger, M.F., Schmahl,

C., Unckel, C., Lieb, K., & Linehan, M.M. (2004). Effec-

tiveness of inpatient dialectical behavioral therapy for

borderline personality disorder: A controlled trial.

Behavior, Research and Therapy, 42, 487–499.

Brown, J.D., & Dutton, K.A. (1995). The thrill of victory,

the complexity of defeat: Self-esteem and people’s

emotional reactions to success and failure. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 712–722.

Campbell, J.D. (1990). Self-esteem and clarity of the self-

concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59,

538–549.

Campbell, J.D., Trapnell, P.D., Heine, S.H., Katz, I.M.,

Lavallee, L.F., & Lehman, D.R. (1996). Self-concept

clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cul-

tural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psy-

chology, 70, 141–156.

Chapman, A.L., & Linehan, M.M. (2005). Dialectical

behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder.

In M. Zanarini (Ed.), Borderline personality disorder (pp.

211–242). Florida: Taylor & Francis.

Chen, T.H., Lu, R.B., Chang, A.J., Chu, D.M., & Chou,

K.R. (2006). The evaluation of cognitive-behavioral

group therapy on patient depression and self-esteem.

Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 20, 3–11.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power for the behavioral sciences.

New York: Academic Press.

Davidson, R., Kabat-Zinn, J., Schumacher, J., Rosen-

kranz, M., Muller, D., Santorelli, S.F., et al. (2003).

Alternations in brain and immune function produced

by mindfulness meditation. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65,

564–570.

De Bonis, M., De Boeck, P., & Lida-Pulik, H. (1998). Self-

concept and mood: A comparative study between

depressed patients with and without borderline per-

sonality disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders, 48,

191–197.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross-cultural correlates

of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology, 68, 653–663.

DiPaula, A., Campbell, J.D. (2002). Self-esteem and per-

sistence in the face of failure. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 83, 711–724.

Ebner-Priemer, U.W., Kuo, J., Kleindienst, N., Welch,

S.S., Reisch, T., Reinhard, I., Lieb, K., Linehan, M.M.,

& Bohus, M. (2007). State affective instability in bor-

derline personality disorder assessed by ambulatory

monitoring. Psychological Medicine, 37, 961–970.

First, M.B., Spitzer, R.L., Gibbon, M., Williams, J.B.W.,

& Benjamin, L.S. (1997). Structured clinical interview

for DSM-IV personality disorders (SCID-II). Washington

DC: American Psychiatric Press.

Fleming, J.S., & Courtney, B.E. (1984). The dimension-

ality of self-esteem: II. Hierarchical facet model for

revised measurement scales. Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 46, 404–421.

Forsman, L., & Johnson, M. (1996). Dimensionality and

validity of two scales measuring different aspects of

self-esteem. Scandinavian Journal of Psycholology, 37,

1–15.

Franke, G.H. (1995). Die Symptom-Checkliste von Derogatis

(SCL-90-R). Göttingen: Beltz.

Fydrich, T., Renneberg, B., Schmitz, B., & Wittchen, H.U.

(1997). Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV.

Achse II. Persönlichkeitsstörungen (SKID-II). Göttingen:

Hogrefe.

Glaser, J.P., Os, J.V., Mengelers, R., & Myin-Germeys, I.

(2007). A momentary assessment study of the reputed

emotional phenotype associated with borderline per-

sonality disorder. Psychological Medicine, 30, 1–9.

Greenwald, A.G., & Pratkanis, A.R. (1984). The self.

In R.S. Wyer, & T.K. Srull (Eds), Handbook of social

cognition (pp 129–178). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Hautzinger, M., Bailer, M., Worall, H., & Keller, F. (1994).

Das Beck Depressionsinventar (BDI): Testhandbuch. Bern:

Huber.

Hill, J., Pilkonis, P., Morse, J., Feske, U., Reynolds, S.,

Hope, H., Charest, C., & Broyden, N. (2008). Social

domain dysfunction and disorganization in border-

158

S. Roepke et al.

Copyright © 2010 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 18, 148–158 (2011)

DOI

: 10.1002/cpp

line personality disorder. Psychological Medicine, 38,

135–146.

Hyun, M.S., Chung, H.I., & Lee, Y.J. (2005). The effect of

cognitive-behavioral group therapy on the self-esteem,

depression, and self-effi cacy of runaway adolescents

in a shelter in South Korea. Applied Nursing Research,

18, 160–166.

Jacobson, N.S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical signifi cance:

A statistical approach to defi ning meaningful change

in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology, 59, 12–19.

Jørgensen, C.R. (2006). Disturbed sense of identity in

borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality

Disorders, 20, 618–644.

Judge, T.A., Erez, A., Bono, J.E., & Thoresen, C.J. (2002).

Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of

control, and generalized self-effi cacy indicators of a

common core construct? Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 83, 693–710.

Kernberg, O.F. (1975). Borderline conditions and pathologi-

cal narcissism. Lanham: Jason Aronson.

Kernberg, O.F., Yeomans, F.E., Clarkin, J.F., & Levy, K.N.

(2008). Transference focused psychotherapy: Over-

view and update. The International Journal of Psycho-

analysis, 89, 601–620.

Kleindienst, N., Limberger, M.F., Schmahl, C., Steil, R.,

Ebner-Priemer, U.W., & Bohus, M. (2008). Do improve-

ments after inpatient dialectial behavioral therapy

persist in the long term? A naturalistic follow-up in

patients with borderline personality disorder. The

Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196, 847–851.

Knapen, J., Van de Vliet, P., Van Coppenolle, H., David,

A., Peuskens, J., Pieters, G., & Knapen, K. (2005).

Comparison of changes in physical self-concept, global

self-esteem, depression and anxiety following two

different psychomotor therapy programs in nonpsy-

chotic psychiatric inpatients. Psychotherapy and Psycho-

somatics, 74, 353–361.

Linehan, M.M., Armstrong, H.E., Suarez, A., Allmon,

D., & Heard, H.L. (1991). Cognitive-behavioral treat-

ment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients.

Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 1060–1064.

Linehan, M.M., Comtois, K.A., Murray, A.M., Brown,

M.Z., Gallop, R.J., Heard, H.L., Korslund, K.E., Tutek,

D.A., Reynolds, S.K., & Lindenboim, N. (2006). Two-

year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of

dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for

suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disor-

der. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 757–766.

Linehan, M.M., Heard, H.L., & Armstrong, H.E. (1993).

Naturalistic follow-up of a behavioral treatment for

chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives

of General Psychiatry, 50, 971–974.

Lynch, T.R., Trost, W.T., Salsman, N., & Linehan, M.M.

(2007). Dialectical behavior therapy for borderline

personality disorder. Annual Review of Clinical Psychol-

ogy, 3, 181–205.

Pollock, P.H., Broadbent, M., Clarke, S., Dorrian, A., &

Ryle, A. (2001). The Personality Structure Question-

naire (PSQ): A measure of the multiple self-states

model of identity disturbance in cognitive analytic

therapy. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 8, 59–

872.

Reynolds, W.M., & Coats, K.I. (1986). A comparison of

cognitive-behavioral therapy and relaxation training

for the treatment of depression in adolescents. Journal

of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 653–660.

Robins, R.W., Hendin, H.M., & Trzesniewski, K.H.

(2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct vali-

dation of a single item measure and the Rosenberg

Self-Esteem Scale. Personality and Social Psychology

Bulletin, 27, 151–161.

Schütz, A. (2005). Je selbstsicherer desto besser? Licht und

Schatten positiver Selbstbewertung. [Self-esteem—The

more the better? Positive and negative aspects of high self-

esteem]. Weinheim: Beltz.

Schütz, A., & Sellin, I. (2006). Die multidimensionale Selbst-

wertskala (MSWS) [The Multidimensional Self-Esteem

Scale, MSES]. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Shavelson, R.J., Hubner, J.J., & Stanton, G.C. (1976).

Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations.

Review of Educational Research, 46, 407–441.

Sheehan, D.V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K.H., Amorim,

P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., &

Dunbar, G.C. (1998). The Mini-International Neu-

ropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development

and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric

interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical

Psychiatry, 59, 22–33.

Stucke, T.S. (2002). Investigation of a German version

of Campbell’s self-concept clarity scale. Zeitschrift für

Differentielle und Diagnostische Psychologie, 23, 475–484.

Swann, W., Rentfrow, P., & Guinn, J. (2003) Self-

verifi cation: The search for coherence. Handbook of self and

identity. New York: Guilford Press.

Taylor, S.E., & Brown, J. (1988). Illusion and well-being:

A social psychological perspective on mental health.

Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193–210.

Tennen, H.J., & Herzberger, S. (1987). Depression, self-

esteem, and the absence of self protective attributional

biases. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52,

72–80.

Watson, D., Suls, J., & Haig, J. (2002). Global self-esteem

in relation to structural models of personality and

affectivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

83, 185–197.

Wilkinson-Ryan, T., & Westen, D. (2000). Identity distur-

bance in borderline personality disorder: An empiri-

cal investigation. American Journal of Psychiatry, 157,

528–541.

Copyright of Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy is the property of John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and its content

may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express

written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Wójcik, Marcin; Suliborski, Andrzej The Origin And Development Of Social Geography In Poland, With

Winlogon Notification Packages Removed Impact on Windows Vista Planning and Deployment

M Kernis Measuring Self Esteem in Context

Alpay Self Concept and Self Esteem in Children and Adolescents

the effect of water deficit stress on the growth yield and composition of essential oils of parsley

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy and BPD Effects on Service Utilisation and Self Reported Symptoms

Extending Research on the Utility of an Adjunctive Emotion Regulation Group Therapy for Deliberate S

Making Contact with the Self Injurious Adolescent BPD, Gestalt Therapy and Dialectical Behavioral T

Changes in personality in pre and post dialectical behaviour therapy BPD groups A question of self

Pancharatnam A Study on the Computer Aided Acoustic Analysis of an Auditorium (CATT)

An Essay on Mozambique

Impact On OIC Countries id 2122 Nieznany

Fossil Fuel Consumption CO2 and its impact on Global Climate

Ferguson An Essay on the History of Civil Society

Pain has an element of blank

więcej podobnych podstron