Behaviour Change | Volume 27 | Number 4 | 2010 | pp. 251–264

Dialectical Behavioural Therapy

and Borderline Personality Disorder:

Effects on Service Utilisation

and Self-Reported Symptoms

Sarah E. Williams,

1

Margaret D. Hartstone

2

and Linley A. Denson

1

1

School of Psychology, University of Adelaide, Australia

2

Central Northern Adelaide Health Service, Australia

In a pilot evaluation study, effectiveness of a 20-week dialectical behavioural ther-

apy (DBT) skills training group program was explored for adult clients with bor-

derline personality disorder (BPD; N = 140). Subjective ratings of depression,

anxiety and BPD symptomatology were obtained pre and post group therapy.

Objective measures of service utilisation levels were obtained for the 6 months

prior to group therapy, the duration of therapy, and the 6 months following ther-

apy. Group completers (n = 68) showed reductions in depression, anxiety and BPD

symptomatology, as well as in the number of emergency department attendances.

Completers with previous high service utilisation had decreases in telephone

counselling calls and inpatient days during therapy, and fewer emergency depart-

ment attendances post therapy. Completers had larger decreases in service utilisa-

tion than noncompleters (n = 72). Simultaneous engagement in individual DBT

was related to higher group completion than was individual therapy as usual, but it

did not impact on level of service utilisation or psychological functioning. This

quasi-experimental pilot study suggests that DBT groups may improve psychologi-

cal functioning and decrease service utilisation for BPD clients, particularly those

with high service utilisation. The treatment warrants systematic evaluation.

■

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, dialectical behaviour therapy, group

therapy, outpatient program, treatment, psychosocial functioning

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) has a strong impact on utilisation of health

and mental health services and is of significant interest to a wide range of clinicians

(Hulbert, Jackson & Jovev, 2008). BPD is characterised by emotional lability,

intense and unstable interpersonal relationships, fear of perceived or actual aban-

donment, recurrent suicidal and self-harming behaviours, impulsivity, identity dis-

turbances, persistent feelings of emptiness, dissociation, and/or stress-related

ideation according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-

IV; American Psychiatric Association, 2004). Occurring in approximately 1–2% of

the population in the United States (Oldham, 2004) and in Australia (Andrews,

Henderson, & Hall, 2001), BPD is associated with very high levels of use of crisis

services, with BPD clients representing 10% of outpatients and 20% of psychiatric

Address for correspondence: Dr Linley Denson, School of Psychology, University of Adelaide, North Terrace,

Adelaide SA 5005, Australia. E-mail: linley.denson@adelaide.edu.au

251

inpatients (Salsman & Linehan, 2006; Sipos & Schweiger, 2003). Approximately 8

to 10% of people with BPD commit suicide (Tanney, 2000). People with BPD usu-

ally present in late adolescence or young adulthood (McCormick, Blum, & Hansel,

2007), and BPD is three times more commonly diagnosed in females (Skodol &

Bender, 2003).

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is considered an effective treatment for

BPD (Linehan & Dimeff, 2001). DBT was developed by Linehan as a team-pro-

vided psychosocial treatment for chronic parasuicidal behaviours (Linehan,

Armstrong, Suarez, Allmon, & Heard, 1991) and typically spans a period of 12

months with three simultaneous components: a weekly skills training group for 2+

hours, weekly individual therapy, and structured support phone counselling

(Linehan et al., 1991; 1993). DBT aims to help people regulate their own emotions

using cognitive, behavioural, mindfulness and acceptance techniques. These skills

are combined within a dialectical view of the world where people are encouraged to

accept and tolerate tensions that arise, while learning to change the way they think

about those tensions (Feigenbaum, 2007). The original study (Linehan et al., 1991)

randomly assigned parasuicidal women with a diagnosis of BPD to either DBT (n =

22) or treatment as usual (TAU; n = 22) for a period of 12 months. DBT comprised

individual, group and telephone support, whereas TAU involved community-pro-

vided treatment. After 12 months DBT was related to a lower number of parasuici-

dal behaviours, less severe parasuicidal behaviours, and lower number and length of

hospital inpatient admissions than TAU. Participants in DBT were more likely to

remain in therapy than those in TAU. However, DBT was no more effective in

decreasing depression symptomatology than TAU. DBT was also related to fewer

parasuicidal behaviours than TAU at 6 months post therapy, and to fewer days spent

in inpatient hospital care at 12 months post therapy.

Subsequent studies have replicated and extended the Linehan et al. (1991)

study. DBT has been found to be related to higher therapy completion rates than

TAU in randomised control trials (RCTs) (Koons et al., 2001; Linehan, Comtois, &

Murray, 2006; Verheul, van den Bosch, & Koeter, 2003) and other studies

(Prendergast & McCausland, 2007; Rathus & Miller, 2002; Sunseri, 2004).

Improvements have been found in suicidal and parasuicidal behaviours over and

above that for other therapies or expert provided therapy (Koons et al., 2001;

Linehan et al., 1991; Linehan Tutek, Heard, & Armstrong, 1994; Linehan et al.,

2006; Low & Duggan, 2001; Verheul et al., 2003). Linehan et al., (1994) replicated

their original finding that DBT and TAU were equally effective in improving psy-

chological functioning. As a result, they concluded that although clients behave

better after DBT they are still miserable. However, preliminary post-DBT data of

many subsequent studies has shown significant temporary and long-term improve-

ments in psychological functioning, including improvements in quality of life,

global functioning, depression, and global distress (Ben-Porath, Peterson, & Smee,

2004; Dams, Schommer, & Ropke, 2007; Nee & Farman, 2005; Prendergast &

McCausland, 2007) over and above that of TAU controls (Koons et al., 2001).

Reductions have continued to be found in mental health service utilisation post

DBT, including number of telephone support utilisations, outpatient service utilisa-

tions, and inpatient days (Brassington & Krawitz, 2006; Prendergast &

McCausland, 2007; Rathus & Miller, 2002). Whereas the original RCT (Linehan et

al., 1991) found a decrease in annual inpatient days of up to 31 days, an uncon-

trolled trial found a decrease of 0.57 to 0.2 inpatient days per month during the 6

Sarah E. Williams, Margaret D. Hartstone and Linley A. Denson

252

Behaviour Change

months of DBT (Brassington & Krawitz, 2006). The reduction in hospital stays has

been estimated to produce savings of $US 9,000 per client per year (Gabbard, Lazar,

& Hornberger, 1997). This is important because of the high proportion of BPD clients

in the mental health system and the high level of cost associated with these services

(Gabbard et al., 1997; Salsman & Linehan, 2006; Sipos & Schweiger, 2003).

Organisations sometimes modify DBT programs, reducing costs, time, and

resources (Black, Blum, & Pfohl, 2004; Prendergast & McCausland, 2007). One ver-

sion used by organisations consists of a DBT skills-training group that is run addi-

tionally to existing treatment usual (TAU) rather than concurrently with standard

DBT individual therapy and telephone support (Black et al., 2004; Prendergast &

McCausland, 2007). Little is known about whether this single-component version of

DBT is as effective as the standard multi-component version, or whether it is effec-

tive enough to be worthwhile in organisations where resources are minimal.

However, it has been suggested that it is the whole DBT program, not its individual

components, that makes DBT effective for use with people with BPD (Black et al.,

2004). Exploration of the effectiveness of DBT groups is important so that current

patient quality of care is optimised, and so that more practical and cost-effective

methods of treatment can be made available to organisations. Some researchers have

begun to explore the benefits of DBT with fewer than the standard three compo-

nents (group, individual and telephone support). Rathus and Miller (2002) evaluated

a shortened 12-week version of DBT consisting of individual and group therapy, and

found that it was more effective than TAU in reducing service utilisation, reducing

suicidal and parasuicidal acts, and increasing completion rates of suicidal adolescents

with BPD. Soler et al. (2005) demonstrated that a 12-week version of DBT that

included DBT telephone support, group DBT, and a placebo drug, was associated

with an equal amount of improvement on self-reported depression and anxiety and

frequency of impulsive aggressive behaviours as a matched group receiving the same

psychotherapy with the addition of olanzapine, an atypical antipsychotic. However,

neither of these studies sought to isolate or explore the impact of one specific ele-

ment of standard DBT for clients with BPD. In addition, they lacked longitudinal

data to demonstrate ongoing benefits of specific DBT components.

The present study proposed that a DBT skills-training group program would be

beneficial in decreasing BPD-related symptoms and functioning, and in decreasing

longitudinal service utilisation. It was also proposed that the substitution of individ-

ual DBT therapy for individual TAU would improve retention rates, and further

improve symptoms and service utilisation post treatment, particularly in high ser-

vice utiliser subgroups.

Method

Participants

Each participant (N = 140) attended a DBT skills training group held between June

2002 and July 2008. Approximately 12 people began each group. Each participant

either commenced individual DBT sessions or continued individual treatment with

their usual therapist (individual TAU). Informed consent for participation and per-

mission for the use of self-report and service utilisation data were obtained from

clients. Research participation was voluntary and not required for admission to the

group. Conduct of the study was approved by The Queen Elizabeth Hospital

Groups for Borderline Personality Disorder

253

Behaviour Change

(Central Northern Adelaide Health Service) and University of Adelaide Research

Ethics Committees.

Design

The design was quasi-experimental with a repeated measures evaluation. One-way

ANOVA, mixed ANOVA and chi square tests were used to compare DBT group

completers and non-completers. A series of paired samples t tests, one-way ANOVA

and mixed ANOVA were used to compare high and low service utilisers, and indi-

vidual DBT and individual TAU clients, on the psychometric tests and service utili-

sation at two data-points (pre and post group therapy). The general linear model

was used to assess main and interaction effects. Several measures of effect size exist

for ANOVA (Dancey & Reidy, 1999): Cohen’s d was selected because it is often

used in clinical research.

Measures

Several self-report psychometric scales were completed at the first and final DBT

group sessions:

• The K10+ (Kessler & Mroczek, 1994) is a 14-item self-report measure (10 psy-

chological distress items and 4 impairment items) measured on a 5-point Likert

scale referring to the previous 4 weeks. It has good construct validity (Cronbach

α = 0.92) and internal consistency (Cronbach α = 0.93) and excellent reliabil-

ity for the total score although its sensitivity to change has not been formally

evaluated (Andrews & Slade, 2001; Pirkis, Burgess, Kirk, Dodson, & Coombs,

2005). There are fewer K10+ scores than for other measures because it was

included in later years of the study.

• The Behaviour and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-32; Eisen, Dill, &

Grob, 1994), a broad measure of wellbeing and quality of life, elicits self-report

responses on five subscales: Relation to Self/Others, Daily Living/Role

Functioning, Depression and Anxiety, Impulsive/Addictive Behavior, and

Psychosis using a 5-point Likert scale. The instrument is sensitive to change

with good concurrent and discriminant validity: scores successfully discriminate

between patients with different diagnoses, employment status and frequency of

hospitalization (Eisen, Dill, & Grob, 1994; Klinkenberg, Cho, & Vieweg; 1998;

Eisen, Wilcox, Left, Schaefer, & Culhane; 1999).

• The Beck Depression Index II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) is a 21-item

scale examining levels of depressive symptoms and severity during the previous 2

weeks, based on a 4-point Likert scale. Validated against the BDI-I, other

depression measures and DSM-IV it has good convergent and discriminant

validity for clinical depression and anxiety, a test–retest correlation of 0.93, and

a mean coefficient alpha of 0.86 for internal consistency (Beck et al., 1996).

• The Borderline Syndrome Index (Conte, Plutchik, Karasu, & Jerrett, 1980),

designed as a quick assessment tool for clinicians, screens for global BPD-related

symptoms and criteria using 52 forced choice Yes or No questions. The initial

study found good discrimination between BPD and other syndromes and con-

trols, but subsequent research showed a correlation with mood symptoms,

detracting from its usefulness as a diagnostic tool (Marlowe, O’Neill-Byrne,

Lowe-Ponsford & Watson, 1996; Remington, 1993).

Sarah E. Williams, Margaret D. Hartstone and Linley A. Denson

254

Behaviour Change

255

• The McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-

BPD; Zanarini et al., 2003), also included in later years of the study, has 10 Yes or

No questions based on the DSM-IV criteria for BPD. It has good test–retest relia-

bility (Spearman’s rho = 0.72, p < .0001) and internal consistency (Cronbach

α

= 0.74). When diagnosing BPD in adults aged 18 to 25 using a cut-off score of 7,

it has sensitivity of 0.81 and specificity of 0.85 (Zanarini et al., 2003).

Mental health service utilisation was collected from the Community Based

Information System (CBIS) database that is used by public mental health services.

Data included number of psychiatric inpatient days, number of presentations to public

hospital emergency departments (ED), and number of telephone support calls to a 24-

hous, 7-days-per-week emergency Assessment and Crisis Intervention Service (ACIS)

6 months prior to, the duration of, and 6 months post group DBT.

The group evaluation invited responses concerning venue and time, whether the

content was useful, and whether other aspects of the group were useful or problematic.

Procedure

The group component of DBT outlined in Linehan’s Skills Training Manual for Treating

Borderline Personality Disorder (Linehan, 1993) was delivered over 20 weeks of 2-hour

sessions addressing the key components: Emotional Regulation, Interpersonal

Effectiveness, Core Mindfulness, and Distress Tolerance. Inclusion criteria were (a)

DMS-IV-TR diagnosis of borderline personality disorder made by the referring clini-

cian; (b) attendance at individual TAU or DBT therapy sessions throughout group

DBT; and (c) residence within the service catchment area, a suburban region of

South Australia, with a population of 300,000+. Criteria were reviewed by clinical

psychologists prior to group admission. Exclusion criteria were (a) current, severe and

uncontrolled psychotic illnesses; (b) severe substance abuse; and (c) significant

aggressive or antisocial traits that may compromise the group process. Group comple-

tion was defined as (a) attendance of at least 70% of sessions; (b) never missing more

than 2 consecutive sessions; and (c) attendance at the final group session.

Groups were run by a government agency providing community-based health and

mental health care to an urban and rural region of Australia. Group facilitators — clini-

cal psychologists trained in DBT — followed Linehan’s program outline. Individual

DBT therapists were also clinical psychologists trained in DBT. Individual TAU was

provided by a range of mental health professionals. Regular consultation team meetings

were held for facilitator support and development. DBT telephone support was not

available but clients were notified of the availability of ACIS for telephone support

during or post group DBT. Most clients receiving DBT individual therapy had been

referred to the community mental health service for anxiety and/or depression, and sub-

sequently identified as meeting BPD diagnostic criteria.

Minor adaptations to Linehan’s group program included discussion during the

first session about the characteristics of BPD, celebration of group completion

during the final session, and development of a crisis management plan by each

client in the final session.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

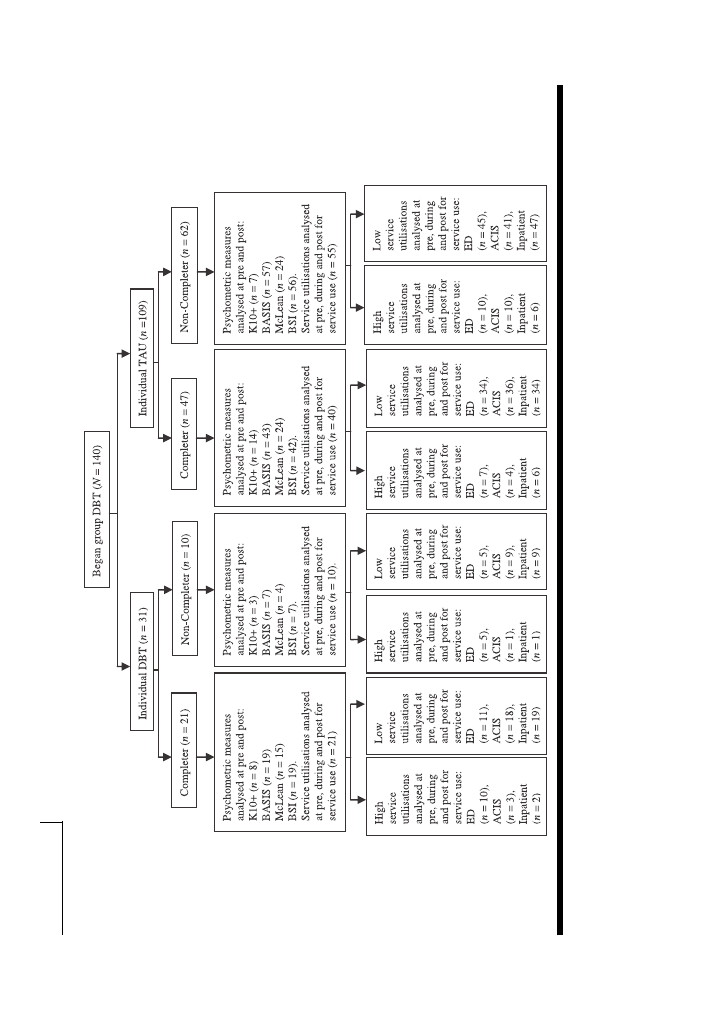

Figure 1 is a flow chart of client recruitment and study participation. Of the 140

participants, 68 completed the group program (13 males and 55 females aged

Groups for Borderline Personality Disorder

Behaviour Change

Sarah E. Williams, Margaret D. Hartstone and Linley A. Denson

256

Behaviour Change

FIGURE 1

Flow chart of participants in the study (

N

= 140).

257

between 19 and 59 years, M = 35.59, SD = 10.02). Seventy-two participants

attended at least one session but did not complete the program (7 males and 65 females

aged between 19 and 60 years, M = 36.24, SD = 11.16).

Consent to access service utilisation data was given by 127 participants. High and

low service utilisation subgroups were separated as suggested by the data distribution:

ED: low = less than 20 attendances in the previous 6 months, high = 20 or more; ACIS:

low < 3 calls in the previous 6 months, high = 3+; Inpatient days: low < 2 days in the

previous 6 months, high = 2+. During the 6 months prior to group DBT, 21% of partici-

pants spent one or more days in psychiatric inpatient care (range 1–69 days), 66% pre-

sented to an emergency department (range 1–80 attendances), and 37% of the

participants made one or more calls to ACIS (range 1–31 calls).

Completers and Non-Completers of Group Therapy

At the beginning of group therapy there were no significant differences between

completers and non-completers for age, gender, pre psychometric scores or service

utilisations in the 6 months prior to group therapy.

Changes in service utilisation during and after group therapy are summarised in

Tables 1 (for DBT group completers vs. non-completers) and 2 (for individual DBT

vs. TAU recipients).

Individual DBT was related to a higher completion rate than individual TAU,

χ

2

(1) = 5.86, p = .02, with 68% of people with individual DBT completing and 43%

of people with individual TAU completing.

ED attendances decreased during group DBT and post group DBT for non-com-

pleters with previous high service utilisation, t(14) = 2.59, p = .01, Cohen’s d = .93;

t(13) = 2.54, p = .01, d = .99.

ACIS calls decreased during group therapy for completers with high utilisation,

t(11) = 3.45, p < .01, d = 1.50. There were no significant decreases for ACIS sub-

groups at other time-points.

Groups for Borderline Personality Disorder

Behaviour Change

TABLE 1

Pre and Post Group DBT Treatment Means (M), Standard Deviations (

SD ), Relationships,

Effect Sizes, and Differential Effects for Completers and Non-Completers

Pre; Post M (

SD)

Completer

Non-completer

Differential effects

p value Cohen’s d (CI95)

p values: Time;

Cohen’s

d (CI

95

)

Time*Group

Group

ED

13.06; 7.87

9.36; 6.56

.01*; .44

(17.77; 11.26)

(14.34; 15.56)

.25

.01*

.11

.35 (-.01, .70)

.19 (-.16, .53)

ACIS

1.30; 1.54

1.77; 3.46

.12; .63

(2.50; 4.13)

(3.65; 11.44)

.31

0.14

0.12

-.07 (-.42, .29)

-.20 (-.54, .15)

Inpatient length

2.79; .81

1.38; .57

.08; .46

(10.21; 4.24)

(5.02; 1.87)

.32

0.09

0.12

Note: *

p < .05, one-tailed

Number of inpatient days decreased significantly during group DBT for com-

pleters overall, t(60) = 1.83, p = .04, d = .31, and for both completers and non-com-

pleters with high service utilization, t(10) = 2.50, p = .02, d = 1.08; t (6) = 2.36, p =

.03, d = 1.13. These decreases were significant post therapy for non-completers with

high utilisation, t(6) = 2.35, p = .03, d = 1.28, but not for other subgroups. That is,

service utilisation decreased regardless of completion or non-completion of group

DBT, but more decreases occurred for people who completed the program.

Individual DBT was related to a significant decrease in number of overall ED

attendances, t(30) = 2.93, p < .01, d = .50, especially for those with high ED utilisa-

tions, t (14) = 3.23, p < .01, d = .90. Among completers with individual TAU, high

ED service utilisers decreased their use, t(15) = 3.22, p < .01, d = 1.19, but overall

ED utilisations did not decrease significantly, t(94) = 1.38, p = .09, d = .18.

Neither type of individual therapy was related to decreases in ACIS calls, but indi-

vidual DBT and TAU were both related to significant decreases in inpatient days for

high utilisers (t (3) = 4.49, p = .01, d = 3.18; t (11) = 2.37, p = .02, d = 1.04).

Sarah E. Williams, Margaret D. Hartstone and Linley A. Denson

258

Behaviour Change

TABLE 3

Group Completers’ Psychometric Scores Before and After Group DBT

M (SD)

Pre

Post

p value

Cohen’s

d

CI95

K10+

34.20 (8.70)

23.73 (8.15)

< .01*

1.24

.58, 1.86

Basis 32

74.57 (24.19)

51.35 (28.42)

< .01*

.88

.51, 1.24

McLean

8.35 (2.02)

5.69 (3.30)

< .01*

.97

.49, 1.43

BSI

34.96 (8.92)

24.07 (12.27)

< .01*

1.02

.63, 1.39

BDI-II

35.11 (14.30)

24.18 (15.87)

< .01*

.72

.35, 1.09

Note: *

p < .05

TABLE 2

Service Utilisation Levels Before and After Group DBT: Means (M), standard deviations

(SD), Relationships, and Effect Sizes, by Type of Individual Therapy, and Differential Effects

Type of therapy*

Individual DBT

Individual TAU

Differential effects

utilisation M: Pre;

p-values Time;

Post (SD: Pre; Post)

Time*Group

p-value, Cohen’s d (CI

95

)

Group

ED

18.74; 10.26

8.72; 6.21

<.01*;

(19.41; 14.28)

(14.22; 13.27)

0.1

< .01*

0.09

.01*

.50 (-.01, 1.00)

.18 (-.08, .45)

ACIS

1.21; 3.29

1.58; 2.60

.11;

(1.97; 7.19)

(3.42; 9.60)

.59

0.06

0.16

.89

-.39 (-.89, .11)

-.14 (-.41, .12)

Inpatient Length

.61; .43

2.55; .77

.29;

(1.64; 2.08)

(9.14; 3.56)

.39

0.37

.04*

.23

.10 (-.40, .59)

.26 (-.01, .52)

Note: *

p < .05

259

Psychometric Test Scores for Completers

Participants reported significant symptoms associated with depression, anxiety, dis-

tress and BPD prior to attending the DBT skills group. Group completers reported

symptom reductions on all psychometric measures post therapy, as well as improved

functioning (see Table 3).

Regardless of whether participants received individual DBT or individual TAU,

their mean scores on all psychometric measures decreased (see Table 4). There were

no main effects of type of individual therapy on psychometric measures: decreases in

psychometric scores were not attributable to type of individual therapy received.

Evaluation of DBT Group

The participants’ evaluation of the group DBT program demonstrated that

Completers thought the group: was at a suitable venue (100%), suitable time

(89%), had useful content (100%), had other useful aspects (100%), and did not

have any other problems (60%). A few completers disliked the ‘slow pace’ and a few

cited disagreements between other group members as problematic.

Summary of Results

This pilot evaluation study supported the hypotheses that group DBT would be

related to decreases in psychometric scores, and that individual DBT would improve

retention rates more than individual TAU. The hypothesis that group DBT would be

related to decreases in service use was partially supported. Previous high service utilis-

ers of each service subgroup decreased service use during and/or post DBT and ED

utilisation decreased significantly for individual DBT recipients. Although Individual

DBT was associated with a higher rate of program completion, both groups showed

similar reductions in self-reported symptomatology and dysfunction.

Discussion

The pilot study aimed to explore the effects of a DBT group skills training program on

a range of variables for people with BPD. Results must be interpreted with caution,

Groups for Borderline Personality Disorder

Behaviour Change

TABLE 4

Changes in Group Completers’ Psychometric Scores by Individual Therapy Type

Individual DBT

Individual TAU

Differential effects

Pre M (SD); Post M (

SD )

Pre M (SD); Post M (

SD )

p values Time;

p value; Cohen’s d (CI95)

p value; Cohen’s d (CI

95

)

Time*Group Group

K10+

34.83 (11.84); 22.67 (6.62)

34.38 (6.84); 25.38 (9.53)

< .01*; .64

.02*; 1.27 (.31, 2.13)

.01*; 1.09 (.42, 1.71)

0.92

Basis 32

73.00 (22.59); 49.47 (21.65)

75.37 (26.77); 54.57 (32.60)

< .01*; .96

< .01*; 1.07 (.47, 1.63)

< .01*; .70 (.41, .98)

0.71

McLean

8.62 (1.33); 6.31 (3.20)

8.00 (2.50); 5.47 (3.48)

< .01*; .73

.01*; .94 (.25, 1.59)

< .01*; .84 (.41, 1.24)

0.29

BSI

34.41 (7.27); 24.88 (9.28)

35.70 (10.13); 25.20 (13.76)

< .01*; .54

< .01*; 1.14 (.54, 1.71)

< .01*; .87 (.57, 1.16)

0.95

BDI-II

32.88 (14.37); 25.24 (13.03)

37.16 (14.06); 24.81 (17.84)

< .01*; .29

.05*; .56 (-.01, 1.10)

< .01*; .77 (.48, 1.06)

0.83

Note: *

p < .05

given the study’s limitations. The design was quasi-experimental and did not include a

control group, comparison therapy, or any form of randomisation, nor were potential

clients who refused DBT group treatment followed up. Thus causality of the group

element of DBT could not be demonstrated, and it is possible (though unlikely)

that people without any form of therapy would have had the same decreases in psy-

chometric scores and service utilisation found in this sample. Also, because group

facilitators were committed to DBT therapy and to offering treatment to this

underserviced group, the study was vulnerable to allegiance factors, where a thera-

pist’s allegiance to a specific type of therapy may influence therapeutic benefits

(Luborsky et al., 1999). Third, because non-completers were no longer in therapy,

post-therapy psychometric scores were not collected. Thus it is not possible to

determine whether the amount of group DBT received was related to the levels of

improvement in psychological functioning. Lastly, although utilisation data were

obtained from public hospitals and mental health services in and surrounding the

catchment area for the study, it is possible that people also attended other services.

The comprehensiveness of the utilisation data is not guaranteed. Nevertheless,

this exploratory and naturalistic pilot study produced some interesting findings,

suggesting directions for future research and practice.

The overall retention rate was 49%, lower than those found by authors using

the standard multicomponent DBT approach, that is, 100% in Linehan et al.’s

(1991) original study, 77% by Koons et al. (2001), and 70% by Soler et al. (2005).

Retention rates were higher for clients receiving individual DBT (68%) than for

those receiving individual TAU (43%). These results support previous findings

(Koons et al., 2001; Linehan et al., 1991; Linehan et al., 2006; Prendergast &

McCausland, 2007; Rathus & Miller, 2002; Sunseri, 2004; Verheul, van den

Bosch, & Koeter, 2003). The proportion of males among participants was higher

than in some other studies, perhaps because participants with some other Axis II

diagnoses were not excluded and because some studies only included female partic-

ipants (Prendergast & McCausland, 2007; Linehan et al., 1991; Verheul, van den

Bosch, & Koeter, 2003). However, the proportion of males included in the current

study (17%), and particularly the proportion of males who completed group treat-

ment (24%), were reasonable reflections of the number of males diagnosed with

BPD in the general population (25%; Skodol & Bender, 2003).

There were no significant differences in age, gender, psychometric scores, or

levels of service utilisation between group DBT completers and non-completers

prior to group commencement. These results suggest that the individual therapy

component of standard DBT contributes to retention and completion rates for

group DBT.

There was a decrease in self-reported symptoms of depression, anxiety and BPD

post DBT group completion. Individual DBT was not superior to individual TAU

in decreasing these symptoms. These findings support previous studies that have

demonstrated that modified DBT programs consisting of fewer than the standard

three elements of DBT (group, individual and telephone support) can be effective

in reducing self-reported psychological and behavioural dysfunction (Rathus &

Miller, 2002; Soler et al., 2005). The findings call into question Black’s (2004)

suggestion that it is the whole DBT program, not its individual components, that

make DBT effective for use with people with BPD. The next step would be an

RCT design to test this assumption.

Sarah E. Williams, Margaret D. Hartstone and Linley A. Denson

260

Behaviour Change

261

There was a significant reduction in ED attendances for completers 6 months

post group therapy (13.06 to 7.87 attendances), especially for high ED service

utilisers (35.53 to 14 attendances). Non-completers did not have a significant

decrease in ED attendances overall, but the high ED service utiliser subgroup of

non-completers significantly decreased their ED use post therapy (33.40 to 16.47

attendances).

Completers with high ACIS service utilisations had a significant decrease in

ACIS calls during the DBT group (5.33 to 1.25 calls), but not post therapy (5.30

to 2.40 calls). This result may be because clients were encouraged to call ACIS,

which is set up specifically for emergency mental health assistance, rather than

overloading ED or inpatient services.

There was a significant decrease in number of inpatient days during group ther-

apy for group completers (2.79 to .57 days). This was accounted for by a significant

decrease in the number and length of hospital stays for previous high service utilis-

ers (16.18 to 1.36 days). In the 6 months post group this decrease in days, though

large from the perspective of cost savings, merely approached statistical signifi-

cance (17.56 to 3.33 days; p = .06).

The addition of individual DBT was not superior to the addition of individual

TAU in reducing levels of service utilisation for either high or low ACIS or inpa-

tient service utiliser subgroups, but was superior in reducing overall ED atten-

dances. Given the greater number of decreases in service utilisation during group

DBT, it is important for organisations to consider the possibility of having booster

sessions for group completers because this may help individuals to retain signifi-

cant decreases in service utilisations post group therapy.

The finding that group DBT completion is related to improvements in the

number of outpatient, telephone support, and inpatient service utilisations during

or post therapy is consistent with the literature (Brassington & Krawitz, 2006;

Linehan et al., 1991; Prendergast & McCausland, 2007; Rathus & Miller, 2002;

Sunseri, 2004). The finding that completers had a larger decrease in service utili-

sations than non-completers is not surprising given that they had more exposure

to group skills training. There were no differences between the completers and

non-completers on baseline psychometric scores or service utilisation, suggesting

that the group component itself impacted these decreases. However, other partici-

pant attributes could have accounted for this difference, including motivation and

endurance.

Participants perceived the group DBT program as being at a suitable venue, at

a suitable time, useful in content, and useful in ‘other areas’. Although 40% of

people mentioned in the ‘other problems’ section of the questionnaire that they

had some issue with the group, only a few described the problem. This often

related to personal difficulties with the communication styles or opinions of other

group members, which is unsurprising because one symptom of BPD is intense and

unstable interpersonal relationships.

In the absence of higher levels of evidence, this pilot evaluation supports fur-

ther clinical practice and evaluation research. It suggests that DBT skills-training

group programs may improve psychological functioning and decrease symptoms for

individuals with a diagnosis of BPD, and decrease service utilisation, especially for

high service utilisers. These results suggest that individual DBT may improve com-

pletion rates for the group DBT program more than individual TAU, albeit alloca-

tion to DBT and TAU was naturalistic and non-random. Group completion is

Groups for Borderline Personality Disorder

Behaviour Change

important because decreases in service utilisation appear to be related to the

amount of exposure to group DBT.

These findings support ‘dismantling’ trials comparing the effects of the differ-

ent elements of DBT to each other, to control groups, and to other forms of ther-

apy, as well as systematic comparisons of the separate and combined effects of

group DBT and individual DBT and TAU attempting to control for total DBT

‘dosage’. Future studies should follow up non-commencing and non-completing

individuals in an ‘intention to treat’ study design, and evaluate motivations and

barriers to therapy commencement and completion. Such studies could continue

the development of time and resource-efficient versions of DBT tailored to the

varying needs of individuals with BPD.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2004). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th

ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Andrews, G., Henderson, S., & Hall, W. (2001). Prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service

utilisation: Overview of the Australian national mental health survey. British Journal of

Psychiatry, 178, 145–153.

Andrews, G., & Slade, T. (2001). Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 25, 494–497.

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. K. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory — second edition:

Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Ben-Porath, D.D., Petersen, G.A., & Smee, J. (2004). Intercession telephone contact with indi-

viduals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder: Lessons from dialectical behavior ther-

apy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 11, 222–230.

Black, D.W., Blum, N., & Pfohl, B. (2004). The STEPPS group treatment program for outpatients

with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 34, 193–210.

Brassington, J., & Krawitz, R. (2006). Australasian dialectical behaviour therapy pilot outcome

study: effectiveness, utility and feasibility. Australasian Psychiatry, 14, 313–319.

Conte, H.R., Plutchik, R., Karasu, T.B., & Jerrett, I. (1980). A self-report borderline scale:

Discriminative validity and preliminary norms. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 168,

428–435.

Dams, A., Schommer, N., & Ropke, S. (2007). Skill training and the post-treatment efficacy of

dialectic behavior therapy six month after discharge of the hospital. Psychotherapie

Psychosomatik Medizinische Psychologie, 57, 19–24.

Dancey, C., & Reidy, J. (1999). Statistics without math for psychology: Using SPSS for Windows (2nd

ed). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Eisen, S.V., Dill, D.L., & Grob, M.C. (1994). Reliability and validity of a brief patient-report

instrument for psychiatric outcome evaluation. Hospital Community Psychiatry, 45, 242–247.

Eisen, S.V., Wilcox, M., Left, H.S., Schaefer, E., & Culhane, M.A. (1999). Assessing behavioral

health outcomes in outpatient programs: Reliability and validity of the BASIS-32. Journal of

Behavioral Health Services & Research, 26, 5–17.

Feigenbaum, J. (2007). Dialectical behaviour therapy: An increasing evidence base. Journal of

Mental Health, 16, 51–68.

Gabbard, O.G., Lazar, S.G., & Hornberger, J.S.D. (1997). The economic impact of psychotherapy:

A review. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 147–155.

Hulbert, C., Jackson, H., & Jovev, M. (2008). Personality disorders. In E. Rieger (Ed.), Abnormal

psychology: leading researcher perspectives (pp. 335–378). Sydney, Australia: McGraw-Hill.

Kessler, R., & Mroczek, D. (1994). Kessler 10 measure. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center of

the Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

Klinkenberg, W.D., Cho, D.W., & Vieweg, B., (1998). Reliability and validity of the interview and

self-report versions of the BASIS-32. Psychiatric Services, 9, 1229–1231.

Sarah E. Williams, Margaret D. Hartstone and Linley A. Denson

262

Behaviour Change

263

Koons, C.R., Robins, C.J., Tweed, J.L., Lynch, T.R., Gonzalez, A.M., Morse, J.Q., et al. (2001).

Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy in women veterans with borderline personality disor-

ders. Behavior Therapy, 32, 371–390.

Linehan, M.M. (1993). Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. New York:

Guilford Press.

Linehan, M.M., Armstrong, H.E., Suarez, A., Allmon, D., & Heard, H.L. (1991). Cognitive-

behavioural treatment of chronically parasuicidal borderline patients. Archives of General

Psychiatry, 48, 1060–1064.

Linehan, M.M., Comtois, K.A., & Murray, A.M. (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and

follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs. therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and bor-

derline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 757–766.

Linehan, M.M., & Dimeff, L. (2001). Dialectical behavior therapy in a nutshell. The California

Psychologist, 34, 10–13.

Linehan, M.M., Tutek, D.A., Heard, H.L., & Armstrong, H.E. (1994). Interpersonal outcome of

cognitive behavioral treatment for chronically suicidal borderline patients. American Journal of

Psychiatry, 151, 1771–1775.

Low, G., Jones, D., & Duggan. (2001). The treatment of deliberate self-harm in borderline person-

ality disorder using dialectical behaviour therapy: A pilot study in a high security hospital

Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 29, 85–92.

Luborsky, L., Diguer, L., Seligman, D.A., Rosenthal, R., Krause, E.D., & Johnson, S. (1999). The

researcher’s own therapy allegiances: A ‘wild card’ in comparisons of treatment efficacy.

Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 6, 95–106.

Marlowe, M.J., O’Neill-Byrne, K., Lowe-Ponsford, F., Watson, J.P. (1996). The Borderline

Syndrome Index: A validation study using the Personality Assessment Schedule. British Journal

of Psychiatry, 168, 72–75

McCormick, B., Blum, N., & Hansel, R. (2007). Relationship of sex to symptom severity, psychi-

atric comorbidity, and health care utilization in 163 subjects with borderline personality disor-

der. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 48, 406–412.

Nee, C., & Farman, S. (2005). Female prisoners with borderline personality disorder: Some

promising treatment developments. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 15, 2–16.

Oldham, J.M. (2004). Borderline personality disorder: An overview. Psychiatric Times, 8, 1–8.

Pirkis, J., Burgess, P., Kirk, P., Dodson, S., & Coombs, T. (2005). Review of standardised measures

used in the National Outcomes and Casemix Collection (NOCC). Canberra: Australian Mental

Health Outcomes and Classification Network.

Prendergast, N., & McCausland, J. (2007). Dialectic behaviour therapy: A 12-month collaborative

program in a local community setting. Behaviour Change, 24, 25–35.

Rathus, J.H., & Miller, A.L. (2002). Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents.

Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 32, 146–157.

Remington, G.J. (1993). Discriminative validity of the Borderline Syndrome Index. Journal of

Personality Disorders, 7, 312–319.

Salsman, N.L., & Linehan, M.M. (2006). Dialectical-behavioral therapy for borderline personality

disorder. Primary Psychiatry, 13, 51–58.

Sipos, V., & Schweiger, U. (2003). Inpatient treatment for men and women with borderline per-

sonality disorder and comorbidity. Verhaltenstherapie & Verhaltensmedizin, 24, 269–287.

Skodol, A.E., & Bender, D.S. (2003). Why are women diagnosed borderline more than men?

Psychiatric Quarterly, 74, 349–360.

Soler, J., Pascual, J.C., Campins, J., Barrachina, J., Puigdemont, D., Alvarez, E., et al. (2005).

Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of dialectical behavior therapy plus olanzapine for bor-

derline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1221–1224.

Sunseri, P.A. (2004). Preliminary outcomes on the use of dialectical behavior therapy to reduce

hospitalization among adolescents in residential care. Residential Treatment for Children &

Youth, 21, 59–76.

Groups for Borderline Personality Disorder

Behaviour Change

Tanney, B.L. (2000). Psychiatric diagnoses and suicidal acts. In R. W. Maris, A. I. Berman & M.

M. Silverman (Eds.), Comprehensive textbook of suicidology (pp. 311–341). New York: Guilford

Press.

Verheul, R., van den Bosch, L.M.C., & Koeter, M.W.J. (2003). Dialectical behaviour therapy for

women with borderline personality disorder: 12-month, randomised clinical trial in The

Netherlands. British Journal of Psychiatry, 182, 135–140.

Zanarini, M.C., Vujanovic, A.A., Parachini, E.A., Boulanger, J.L., Frankenburg, F.R., & Hennen, J.

(2003). Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): A continuous

measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology. Journal of Personality Disorders, 17, 233–242

Sarah E. Williams, Margaret D. Hartstone and Linley A. Denson

264

Behaviour Change

Copyright of Behaviour Change is the property of Australian Academic Press and its content may not be copied

or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission.

However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Contrasting Clients in Dialectical Behavior Therapy for BPD Marie and Dean , Two Caseswith Diffe

Dialectical Behavior Therapy for BPD A Meta Analysis Using Mixed Effects Modeling

Stages of change in dialectical behaviour therapy for BPD

Making Contact with the Self Injurious Adolescent BPD, Gestalt Therapy and Dialectical Behavioral T

Dialectic Beahvioral Therapy Has an Impact on Self Concept Clarity and Facets of Self Esteem in Wome

Changes in personality in pre and post dialectical behaviour therapy BPD groups A question of self

Brief Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Suicidal Behaviour and NSSI

Differential Treatment Response for Eating Disordered Patients With and Without a Comorbid BPD Diagn

[30]Dietary flavonoids effects on xenobiotic and carcinogen metabolism

Changes in passive ankle stiffness and its effects on gait function in

Cognitive and behavioral therapies

Heavy metal toxicity,effect on plant growth and metal uptake

33 437 452 Primary Carbides in Spincast HSS for Hot Rolls and Effect on Oxidation

49 687 706 Tempering Effect on Cyclic Behaviour of a Martensitic Tool Steel

48 671 684 Cryogenic Treatment and it's Effect on Tool Steel

Genetic and environmental effects on polyphenols

[30]Dietary flavonoids effects on xenobiotic and carcinogen metabolism

Chung, Zhao Humor effect on memory and attitude moderating role of product

więcej podobnych podstron