Gentlemen

Praise for the series:

It was only a matter of time before a clever publisher realized

that there is an audience for whom Exile on Main Street or

Electric Ladyland are as significant and worthy of study as

The Catcher in the Rye or Middlemarch…. The series … is

freewheeling and eclectic, ranging from minute rock-geek

analysis to idiosyncratic personal celebration—The New York

Times Book Review

Ideal for the rock geek who thinks liner notes just aren’t

enough—Rolling Stone

One

of

the

coolest

publishing

imprints

on

the

planet—Bookslut

These are for the insane collectors out there who appreciate

fantastic design, well-executed thinking, and things that make

your house look cool. Each volume in this series takes a

seminal album and breaks it down in startling minutiae. We

love these. We are huge nerds—Vice

A brilliant series…each one a work of real love—NME (UK)

Passionate, obsessive, and smart—Nylon

2

Religious tracts for the rock ‘n’ roll faithful—Boldtype

[A] consistently excellent series—Uncut (UK)

We … aren’t naive enough to think that we’re your only

source for reading about music (but if we had our way …

watch out). For those of you who really like to know

everything there is to know about an album, you’d do well to

check out Continuum’s “33 1/3” series of books.—Pitchfork

For reviews of individual titles in the series, please visit

our

website

at

and

3

Also available in this series:

Dusty in Memphis by Warren Zanes

Forever Changes by Andrew Hultkrans

Harvest by Sam Inglis

The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society by

Andy Miller

Meal Is Murder by Joe Pernice

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn by John Cavanagh

Abba Gold by Elisabeth Vincentelli

Electric Ladyland, by John Perry

Unknown Pleasures by Chris Ott

Sign O’ the Times by Michaelangelo Matos

The Velvet Underground and Nico by Joe Harvard

Let It Be by Steve Matteo

Live at the Apollo by Douglas Wolk

Aqualung, by Allan Moore

OK Computer by Dai Griffiths

4

Let It Be by Colin Meloy

Led Zeppelin IV by Erik Davis

Armed Forces by Franklin Bruno

Exile on Main Street by Bill Janovitz

Grace by Daphne Brooks

Murmur by J. Niimi

Pet Sounds by Jim Fusilli

Ramones by Nicholas Rombes

Endtroducing… by Eliot Wilder

Kick Out the Jams by Don McLeese

Low by Hugo Wilcken

In the Aeroplane Over the Sea by Kim Cooper

Music from Big Pink by John Niven

Paul’s Boutique by Dan LeRoy

Doolittle by Ben Sisario

There’s a Riot Goin’ On by Miles Marshall Lewis

Stone Roses by Alex Green

5

Bee Thousand by Marc Woodworth

The Who Sell Out by John Dougan

Highway 61 Revisited by Mark Polizzotti

Loveless, by Mike McGonigal

The Notorious Byrd Brothers by Ric Menck

Court and Spark by Sean Nelson

69 Love Songs by LD Beghtol

Songs in the Key of Life by Zeth Lundy

Use Your Illusion I and II by Eric Weisbard

Daydream Nation by Matthew Stearns

Trout Mask Replica by Kevin Courrier

Double Nickels on the Dime by Michael T. Fournier

People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm by

Shawn Taylor

Aja by Don Breithaupt

Rid of Me by Kate Schatz

Achtung Baby by Stephen Catanzarite

If You’re Feeling Sinister by Scott Plagenhoef

6

Let’s Talk About Love by Carl Wilson

Swordfishtrombones by David Smay

20 Jazz Funk Greats by Drew Daniel

Horses by Philip Shaw

Master of Reality by John Darnielle

7

8

Gentlemen

Bob Gendron

9

10

2008

The Continuum International Publishing Group lnc

80 Maiden Lane, New York, NY 10038

The Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd

The Tower Building, 11 York Road, London SE1 7NX

www.continuumbooks.com

33third.blogspot.com

Copyright © 2008 by Bob Gendron

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by

any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying recording,

or otherwise, without the written permission of the publishers

or their agents.

Printed in Canada on 100% postconsumer waste recycled

paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gendron, Bob, 1975-

Gentlemen / Bob Gendron.

p. cm. - (33 1/3)

eISBN-13: 978-1-4411-4625-0

1. Afghan Whigs (Musical group) 2. Alternative rock

musicians—United States. 3. Alternative rock music—United

States—History and criticism. I. Title. II. Series.

11

M1.421.A326G46 2008

782.42166092’2-dc22

2008022030

12

13

15

Dedicate It

Many thanks to David Barker for taking the chance,

believing, and viewing music as art still worthy of meaningful

prose. Grazie mille to the original members of the Afghan

Whigs (Greg Dulli, John Curley, Rick McCollum, Steve

Earle) for agreeing to oft-lengthy interviews and, in Greg and

John’s case, giving me contacts, personal tours, valuable face

time, and honest responses; without their participation, this

book would not have been possible. Merci to Lee Heidel, for

contacts and music, and to Robert-Jan van der Woud, Keith

Hagan, and Chris DeVille, for contacts.

Journalistic integrity, diligent reporting, and historical context

are too often absent from the agenda-promoting opining that

today passes for music criticism. For setting and maintaining

an irreproachable standard, and being a good friend, sincere

thanks to Greg Kot. His writing has always been and remains

a primary inspiration. Thanks as well to my friend and

colleague Andy Downing for lending an ear and taking an

interest. And many thanks to my editors past and present

—Jonathan Valin, Robert Harley, Chris Martens, Heidi

Stevens, Lou Carlozo, Kevin M. Williams, Carmel Carrillo,

Emily A. Rosenbaum, Scott L. Powers—for their expertise,

advice, and guidance.

Danke, to Jeannette Chernin for being a caring sister. Extra

thanks to Michael L. Miller for constant support and kind

words; a better friend doesn’t exist. Utmost gratitude to my

mother, Nanette, who always permitted my music obsessions

and allowed me to work at an indie record store and travel to

16

concerts long before I was old enough to drive. Most of all,

supreme love and thanks to my beautiful wife, Ann, for all of

the love, encouragement, faith, laughter, and patience—and

for going to the fateful Whigs concert with me in Austin one

week before our wedding. This book is for you, and in loving

memory of George J. and Leona Gendron.

And thank you, the reader, for purchasing this book—or at

least, browsing through it long enough to encounter this

passage. Like it? Hate it? Email me thoughts or questions at

. I will reply.

Unless otherwise noted, all factual information and quotes are

from the author’s interviews or experiences witnessed

firsthand.

17

18

Intro

Hard Time Killing Floor

Greg Dulli lies motionless on his left side. His body is

crumpled, his eyelids shut. The singer’s expression is blank,

his mind unconscious. His wavy black hair mashes up against

a pillow. Wrapped up in white sheets, Dulli looks limp and

frail, particularly in the eerie pall cast by the yellow-haze

sunlight filtering through the window. The bumpy outline of

his physique, like an ancient mummy, seems small and

insignificant. If not for the methodical blip of heart monitors

tracking his breathing, one could easily presume him dead.

He almost is. Dulli is in the midst of a fifty-hour coma that,

before it ceases, will see the singer flatline and receive Last

Rites.

As the Afghan Whigs frontman remains stationary on a bed in

an Intensive Care Unit at a downtown Austin hospital, bassist

John Curley slowly paces outside the room’s door, staring

down at the floor in disbelief. His solemnity has nothing to do

with the group’s future, which, as an active band, will

effectively be over within a year. He’s concerned

about whether or not Dulli will survive—and if he does,

whether he’ll recover without suffering brain damage or

related health issues.

Hours before being forced into traction, Dulli led his

Cincinnati ensemble through a sweaty, revue-style concert in

front of a packed house on December 11, 1998, at Liberty

Lunch. Teasing out songs with impromptu banter and

snippets of Prince, James Booker, and Beatles tunes, the

19

Afghan Whigs were again proving themselves the most

riveting live rock act going—a band so formidable onstage,

Dulli was able to convince Columbia Records to pony up the

money to allow the group to travel with horn players, backup

singers, and a pianist. Persuasive, smooth, and confident, he’s

someone who doesn’t easily take no for an answer or back

down from a challenge. Particularly when his friends are

involved or his ambitions questioned.

While they give no indication of prior turmoil during their

two-hour-plus show, upon arriving at the now-leveled Texas

venue, the Whigs are met with good-old-boy attitude. Along

with Dulli, opening act Alvin Youngblood Hart and

tour-support vocalist Steve Myers, both African-American,

customarily pound on the metal fire door in order to gain

entrance for soundcheck. An angry redneck greets them:

“Niggers.” The remark sends Dulli into frenzy. He grabs the

hick by his billy-goat beard, yanking him around as a pit bull

would a chew toy. After learning of the incident, Liberty

Lunch managers pledge to remove the offending employee.

The concert goes off as planned. But this being Austin—land

of George W. Bush, and the very city where the Whigs were

sued by a girl who was accidentally nicked by a water pitcher

passed around in the crowd—Texas-style justice is about to

be served.

Long after finishing the closing “Miles Iz Ded,” and at the

end of a scheduled after-show meet and greet, Dulli enters the

men’s restroom to urinate. The last thing he remembers is

washing his hands. It’s probably best that he not recall the

specifics of being hit from behind, smacked with what he

believes was a 2 x 4 before being kicked twice in the head

while he was already down. Or that he recollects his assault at

20

the hands of a loser named Teitur, the same rube who rudely

answered the door and learned that Dulli isn’t someone to

take lightly before milling about in the club so he, with

assistance from fellow bouncer “Porkchop,” could blindside

his target and fracture his skull. Or that Dulli relives hitting

the Lunch’s unforgiving concrete floor, headfirst, with no

chance to react—let alone fight back. Or that he reflects on

his pool of blood being left on the floor by Liberty Lunch

management, which concocted a false defense and protected

Teitur and Porkchop by sneaking the tandem out a side door

before police arrived and started asking questions. Or that he

knows that as news of the attack hits the wires, haters light up

Internet message boards saying the singer deserved his fate.

It takes a rare breed of artist to inspire such reactions. Keeper

of a radiant aura and mojo hand, Dulli knows this. He’s no

stranger to arousing passions, inciting opinions, and

provoking responses. Suave and debonair, the magnetic

front-man worked stages with a self-assured sensibility and

larger-than-life presence that went unrivaled during the

90s—an era when unkempt grunge noisemakers, punk-pop

pretenders, and cartoonish rap-rock oafs dominated, leaving

soul, style, and sensuality by the wayside. Dulli is a man’s

man—the type who assists a male fan by doing the awkward

prom-dance asking for him, and the very next moment steals

away an undeserving

dude’s girlfriend, all the while taunting her date. “Does he

love you? Because if he doesn’t, then meet me backstage,” he

exclaimed with regularity during the Whigs’ 1965 tour, only

half-kidding. Dressed in a dark suit, puffing on Camels, and

sauntering as a casual playboy, he was the center of attention

every guy wanted to be and the sex symbol every tumed-on

girl wanted to fuck.

21

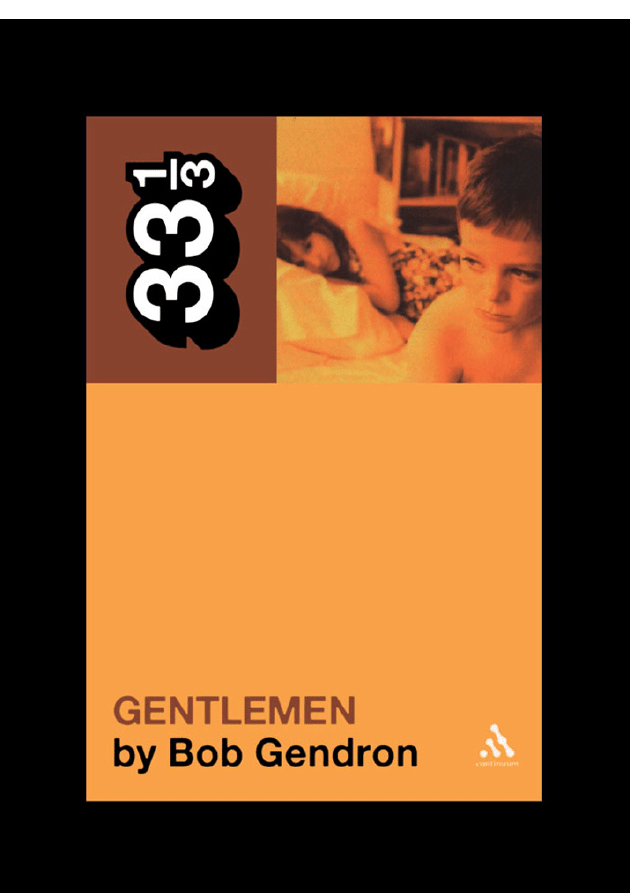

And on Gentlemen, in he swaggers, the chain-smoking

assassin who has a dick for a brain, invading our dark

subconscious and secretive past. Like no record before or

since, Gentlemen is fraught with the psychological warfare,

bedroom drama, Catholic guilt, reprehensible deception, and

uncleansable shame that coincide with relationships gone

seriously wrong. Its seemingly thick skin is rife with

argument, infection, claustrophobia, temptation, accusation,

illness, addiction, blood, scourge, and spite. Certainly, the

album’s psychoanalytic posturing, vindictive blame, and

sinister betrayal offer sanctuary for self-loathing romantics

and catharsis for unrepentant sinners. Yet behind the

bulletproof veneer and cocksure innuendo reside anguish,

sickness, pain, and disgust, emotions mirrored on the record’s

suggestive cover—where two children, playing the grown-up

parts of embittered lovers, depict obvious disconnect, the

twisted image a potent metaphor for the album’s themes of

anger, hurt, confrontation, disappointment, and contempt.

And then there’s the music. Dulli’s liquor-cabinet confessions

are chased with some of the blackest-sounding rock ever

committed to tape by a white band. Hopped-up on primal

energy, the mesmerizing R&B, funk, slide-blues, garage, and

chamber-pop strains are tied to a come-hither soulfulness

perfumed with hyssop and stained with nicotine.

To this day, Gentlemen remains as cursed as its controversial

narrator, an album out of time even in its time. Released on

October 5, 1993, it has sold 162,000 copies, a respectable

number, but far fewer than works by many “alternative”

bands of the day. The situational ironies run deep. The

Afghan Whigs were the second non-Seattle and first

East-of-Denver artist signed to Sub Pop, the very imprint

whose meteoric rise helped launch countless coattail-riding

22

groups

with

flannel

shirts

and

four-day-old-growth

beards—the same bands whose in-vogue distortion and

soft-loud songs ran contrary to the Whigs’ loose, sexy

dynamic. Gentlemen was the Whigs’ major-label debut, and

still it bore the hip black-and-white Sub Pop logo. Not that it

mattered. MTV’s fleeting flirtation with “Debonair” mirrored

radio’s widespread disinterest. Despite glowing reviews and

feverish tour support, Gentlemen faded from view. And yet it

remains dearly beloved to almost everyone who’s heard it,

taking its place amidst Richard and Linda Thompson’s Shoot

Out the Lights, Marvin Gaye’s Here, My Dear, and Bob

Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks as one of the rawest, most

searing break-up records in history.

This book is about Gentlemen and how it came to be—via a

polarizing frontman whose fierce bravado, GQ appearance,

and gloves-off exuberance concealed deep-rooted mental

depression and chemical dependency; and the invaluable

contributions and chemistry of a driven quartet, whose

differing personalities, backgrounds, and tastes comprised a

band that truly sounded like no other. It’s about

boundaries—between North and South, black and white, rock

and soul, personal and private. Rivers and hills provide

Cincinnati with natural borders, but Dulli, Curley, guitarist

Rick McCollum, and drummer Steve Earle were too curious

to stay on their side

of the tracks, too obsessed with how blues, booze, drugs, and

sex—strictly taboo in their conservative hometown—could

ignite a groove, seduce a girl, and stroke the ego. It’s a story

about what happens when intellectual sophistication and blunt

reflection are star-crossed with outspoken braggadocio, a

charismatic mixture that managed to alienate the mainstream

horde and arms-folded scenesters while, for good measure,

23

instigated outsider jealousy, condescending rumors, and,

ultimately, insider sabotage.

Now.

24

25

I. Back from Somewhere

“When the end of the world comes, I want to be in Cincinnati

because it’s always twenty years behind the times.”

—Mark Twain (attributed)

Cincinnati is nestled in the Southwest corner of Ohio, a

geographical location that stirs debate about whether or not

it’s a North or South city—or, for that matter, Midwest, East,

or West. Notoriously conservative and highly segregated,

most residents tend to stay within their own neighborhoods

and are very slow to adopt changes. Rolling green hills,

hidden enclaves, and wooded areas afford a bucolic setting

uncommon to most metro areas. It is beautiful country, and

nature makes its presence known everywhere you turn.

Downtown, the Ohio River separates the Queen City from its

nearby Kentucky neighbors of Covington and Newport. Both

are a one-minute ride away.

Settled in the late 1700s, Cincinnati was an abolitionist town

and stop on the Underground Railroad. For slaves lucky

enough to escape, freedom was potentially just a half-mile

swim away. Conversely, for those seeking vices, a jaunt over

to the Bluegrass State offered what the increasingly

moderating Cincinnati climes lacked: liquor, prostitutes,

drugs, and gambling. With such narrow borders separating sin

from temperance, and slavery from freedom, pronounced

tensions and divisions quickly developed.

26

Bounty hunters camped in Cincinnati, hoping to recapture

slaves before they permanently disappeared into the North.

Abolitionists stumped there as well, risking their lives for

those of others. A major race riot erupted in 1829. And while

a majority of residents sided with the Union in the Civil War,

a number headed south in favor of the Confederacy. In the

same way it divided racial opinions, the city’s straddling

bearings caused cultural clashes, with country bumpkins and

progressive urbanites claiming the same territory and further

muddling identity issues.

Today, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center

sits off the Ohio River’s banks in lower downtown. The base

of the John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge looms in front of

the south entrance. Opened to pedestrians in 1866, the

stone-tower span served as the prototype for the Brooklyn

Bridge—also designed by Roebling—and remains the

primary pathway for automobiles and pedestrians traveling

between Covington and Cincinnati. Fittingly, the sound of a

car driving across the Suspension Bridge—the demarcation of

social, racial, and political boundaries—marks the beginning

of Gentlemen.

John Curley doesn’t say a word as he drives his station wagon

across the Roebling overpass. He doesn’t have to. In the

background, one can detect the haunted intro to Gentlemen’s

opening “If I Were Going.” It’s a hot mid-May afternoon, and

the rubber grooves of the Mercedes’s tires are dancing across

the bridge’s metal grates, creating a buzzing sound that’s

reminiscent of an agitated hornet’s nest. Most drivers

unconsciously tune it out. But listen closely, and the noise

produces uncomfortable, claustrophobic tones. It was here in

April 1993 that Curley hung a microphone out of his car

27

while Dulli drove, capturing the perfect noir prelude to an

aurally cinematic drama.

Curley was bom March 15, 1965, in Trenton, New Jersey.

Save for his senior year of high school, he was raised in a

nuclear family environment in Delaware before moving to

Cincinnati for a photography internship at the Cincinnati

Enquirer. He hasn’t left since. Solidly built and slightly

chunky, he now looks like a barrel-chested teddy bear.

Salt-and-pepper whiskers sprout like weeds throughout his

formerly all-black beard. He wears a plaid button-down shirt

over a white T-shirt, khaki pants, and Ray-Ban pilot

sunglasses. Bedhead hair rounds out his informal demeanor.

When Curley grins, a small gap between his upper left teeth

appears and adds to his laid-back charm. Eyebrows dominate

his forehead when he thinks. Calm and collected, he speaks

with a slight drawl. He currently plays in the Staggering

Statistics and runs Ultrasuede Studios, a red-carpeted spot

that would be right at home on the Partridge Family. Yet

everything about him confirms his primary occupation as a

devoted husband and father of two children.

“I remember really liking music since about the time I was in

the first grade,” Curley recalls, as Tom Petty’s “American

Girl” plays on a Sirius Radio amidst the whooshing air

conditioning. “I got a cassette player and would record my

favorite songs off the radio. I think it’s always been the twin

interests of music and recording. And I think photography

also falls into that because it’s using machines to be creative.”

For a musician whose posture, physique, and approach evoke

those of John Entwistle, it’s only apropos that Curley’s

motivation to pick up a bass at age fifteen came after hearing

28

the Who’s Quadrophenia. “It was like hearing the bass for the

first time,” he admits. A music teacher who forced him to

learn exercises and repeatedly practice taught him the basics.

Later, some cooled-out stoner jazzheads opened his mind up

to musical theory and improvisation. Absorbing the music of

Earth, Wind & Fire, Attractions bassist Bruce Thomas, the

Beatles, and Jesus Christ Superstar did the rest.

“With the Whigs, I draw on stuff that I know will work. Greg

and Rick are more natural—they don’t have the intermediate

step of having to remember what works with what. They just

go there. I knew enough to be able to thread the gap, and

connect with the drums. So musically, that helped us. And

then, of course, having a singer like Greg.”

Greg Dulli was born May 11, 1965, in Hamilton, a town

about twenty-five miles northwest of Cincinnati. It’s where

he’d spend his entire young life. Since his mother was a soul

fanatic and only eighteen years old when she delivered him,

Dulli’s childhood was filled with music. He recalls

purchasing his first single (the Jackson Five’s “I Want You

Back”) when he was four and remembering his mom spin

Stevie Wonder, Temptations, Supremes, Lee Dorsey, Al

Green, and the like on the turntable. On visits to his

grandparents’ house in West

Virginia, he soaked up the country sounds of Conway Twitty,

Loretta Lynn, George Jones, and Kitty Wells. Neighborhood

kids exposed him to rock, with Led Zeppelin, Rolling Stones,

Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Kiss being favorites.

“I was in Kiss Army. I probably still am—never did get my

discharge,” Dulli cracks, a shit-eating grin washing over his

face

as

he

lounges

in

the

living

room

of

his

29

late-eighteenth-century house on a sultry August day in New

Orleans. For a moment, his expression—cute, curious,

mischievous—resembles that of an eleven-year-old who just

snuck a long peek at a gorgeous woman in the shower. It’s a

look that repeats every time he has a good idea, turns wise, or

talks about what makes him happy.

Casually dressed in a blue polo shirt, shorts, and sandals,

Dulli exudes breezy California cool. His frame is more filled

out than it was a decade ago. Specks of gray color his tousled

hair. He gulps iced tea by the gallon and lights incense for

ambience. Yet aside from a mellower disposition, Dulli

possesses all of the savvy charm, contagious energy,

straight-shooting candor, and biting humor that have made

him a permanent part of alt-rock folklore. As he talks about

his upbringing and takes an extended drag from one of the

countless cigarettes he’ll inhale during the next nine hours, a

History Channel show about the Antichrist airs on a muted

television that’s always left on to ward off wrongdoers. As if

picking up on the show’s unpleasant vibe, the conversation

steers to Dulli’s strict father.

Unlike his supportive mother, Dulli’s music-alienated dad

refused to allow the singer to take any sort of lessons. But that

didn’t hinder Dulli’s passion. A Catholic altar boy, he sang in

church but would occasionally accompany his neighbors to

their Baptist church. “It was fun. They’d throw-down

and people would start rolling their eyes in the back of their

heads and fall on the ground and speak in tongues. I’m like,

Well you’re fucking nuts,’ but there’s the joyousness of it.”

He also took up the drums, heading over to friends’ houses to

practice and pick up what he could. Other outsider

influences—Hunter

S.

Thompson,

Keith

Richards,

30

Cincinnati’s uptightness—fed his early desire to experiment

with marijuana and cocaine. Religion had already lost its

hold, though its precepts would haunt Dulli for years.

“I stopped going to Catholic church in the eighth grade

because I began to have philosophical differences. I found it

hypocritical. I told my mother, who was very Catholic, that I

didn’t want to go to church anymore. She told me if I stated

my reasons in an essay, she’d read it and decide if it was

okay. I wrote a three-page essay stating my reasons I wanted

to leave the Catholic church and left it on her dresser. When I

came home from school the next day, she sat me down. She

was crying. But she said I had stated my reasons and that I

wouldn’t have to go to church anymore. I never went again.”

At fifteen, Dulli joined his first band as the vocalist for Helen

Highwater—named by Lynyrd Skynyrd guitarist Allen

Collins. While the group originally played Stones, Kinks,

Who, and Doors covers, a guitarist suggested that it become a

Skynyrd tribute act. Dulli bristled, leading to a betrayal that

shaped how he would view band organization and discipline.

Rather than being fired, Dulli discovered he’d been replaced

by a Ronnie Van Zandt look-alike after hearing music waft

out of his old guitarist’s house and spying his former band

jamming in the basement. The experience devastated him. “It

was like catching your wife fucking somebody else. It broke

my heart. I was like, ‘I’m not doing this anymore.’”

But once Dulli enrolled at the University of Cincinnati, band

life beckoned. He started the Black Republicans as a

freshman before dropping out and moving to Los Angeles.

After his mother got sick and needed him to serve as his

sister’s legal guardian, Dulli returned to Cincinnati and

31

reformed the Black Republicans, which became a going

concern by 1985. Around that time, Dulli began noticing a

“weird, older dude” he thought to be about forty coming out

to the shows. Finally, at the end of one gig, the seemingly

out-of-place fan came up to talk to him. It was Curley, who

made it a point to tell the vocalist he was a better bassist than

the one in the Black Republicans. Dulli took the bait. “I said,

‘Well, come on out. Let’s see what you got.’ I knew our

[bassist] was going back to college. And he was great. To this

day, my favorite bass player I’ve ever played with.”

The two had actually met once before, at an apartment, under

less-auspicious circumstances. Dulli was writing somebody’s

term papers and got distracted by the sounds of the Allman

Brothers Band’s “One Way Out” being blared at loud,

shaking-the-pictures-off-the-wall levels from across the hall.

Ironically, Dulli was a fan of the band and the album (Eat a

Peach) but insists the volume was unbearable. “I went to

knock on the door and said, ‘You’ve got to turn that down,

man.’ The guy who answered was the dude who came to our

gigs. And I remember peaking in the door and seeing some

freakish long-haired dude sucking on a bong who turned out

to be Rick.”

Rick McCollum was born July 14, 1964, in Louisville,

Kentucky. Like Dulli, he was brought up Catholic and started

playing drums in junior high. But he soon switched to guitar,

self-learning from playing records back at half-speed.

McCollum’s mother died when he was just twelve, and his

father, who passed ten years later, was already on his way to

an early grave via alcohol abuse. Understandably shy and rail

thin, McCollum admits to having been a loner throughout his

32

childhood and tenure in the Whigs. His mysterioso reticence

inspired the nickname Moon Maan.

“Greg gave it to me because I’m a smart guy but at the same

time I was very quiet and hard to pinpoint,” says McCollum,

talking on the phone from his home in Minneapolis. “I didn’t

really get close to anybody. Nobody could ever bond with me

and I kept a shield around me from everyone. I didn’t put too

many opinions out just because that’s the way I was; it hides

your personality.”

“He’s super quiet, very polite, and pretty inward,” confirms

Dulli. “I could tell he was one of those in-his-room kids, had

no friends, and played guitar twelve hours a day. And that’s

exactly what he turned out to be: a savant.” Not that

McCollum’s Type B personality meant that he was someone

to pick on. “Rick is like tightly wound cable,” cautions Dulli,

who often introduced McCollum onstage by saying, “Folks,

you don’t have to do heroin. You just have to look like you do

heroin.”

“He has no body fat even though he just piles donuts in his

mouth. I remember when Steve Earle took him on. Earle went

from upright to on his back in less than a second. It was

fucking Matrix-type shit—swift and surreal. In that

half-second that he went down, I made a mental note: Don’t

fuck with Rick.”

Even though he grew up in Kentucky, McCollum remained

mostly unaware of Southern Rock until his college years and

didn’t play slide guitar until Dulli later tasked him with the

challenge. Instead, McCollum’s tastes gravitated to 70s R&B

such as Earth, Wind & Fire, Bootsy Collins, and

33

Brick—music that focused on the grooves and beats first and

foremost, and riffs and vocals second. “It’s a soul music type

of thing. It might be geographical, where, the further south

you go, the more prevalent it is.”

After the Black Republicans broke up, McCollum continued

to jam with Curley. Dulli relocated to the Arizona desert,

where he worked a midnight shift, taught himself guitar, and

wrote half of the songs for what became the Whigs’

self-released and roughly amateurish debut, 1988’s Big Top

Halloween. He joined a band called Bakersfield Mistake—the

moniker referencing VD the bassist caught while gallivanting

in Bakersfield—whose lifespan was cut short after said

bassist screwed the drummer’s girlfriend. Aptly, a sexual

liaison led to the advent of the Afghan Whigs.

Bored and without a band, Dulli moved back to Cincinnati

with the intent of starting his own group. He was also sitting

in with Curley and McCollum, who were trying out

drummers. Dulli explains: “They didn’t get any drummers

that were as good as me. I said, ‘Don’t get that guy. Don’t get

that guy, either.’ Then Rick put up an ad and Steve Earle

answered. Steve was a great drummer. That’s when I was

like: ‘This could be cool.’ So maybe I’ll stay as the second

guitar player and singer.”

Steve Earle was born March 28, 1966, in Cincinnati. Raised

by Protestant-Catholics, he became enamored with the drums

after attending a ninth-grade sock-hop dance at which he

noticed the drummer’s double-bass kit. “It sounded so

powerful,” he says on the phone from his home in Ohio. “I

loved the way it looked and seeing how much fun the guy was

having. That’s pretty much it: It’s loud, it’s cool, I’ll do it.”

34

Primarily influenced by Keith Moon, John Bonham, and

Ringo Starr, and a fan of some heavy metal, Earle took

lessons from an old-school jazz hound that steered him

toward Louie Bellson, Buddy Rich, and Philly Joe Jones. His

tolerant parents—-who appear in leather in the Whigs’

“Debonair” video—allowed band practices in their basement.

Earle had attended University of Cincinnati for two years

when he tried out for the Whigs. The audition consisted of

playing the Temptations’ “Psychedelic Shack,” Zeppelin’s

“Rock and Roll,” and the Church’s “One Day” (McCollum

had a flair for goth), as well as a few other covers. By

Halloween 1986, the quartet was loosely rehearsing.

Christened by Curley as a play on the name Black

Republicans, the Afghan Whigs performed their first show at

Jockey Club in December 1986.

From the start—they quickly became a regular attraction at a

local lesbian pool hall—it was clear the Whigs weren’t going

to be a typical college-rock band. The members claimed

disparate personalities, interests, and backgrounds, and yet,

these differences—and some common bonds—melded into a

distinctive being. Dulli also possessed uncommon vision and

organizational skills. Determined not to repeat the errors of

his previous groups, and inspired by the machine-like

precision of James Brown, Lynyrd Skynyrd, and Berry

Gordy, he took charge and put the band through boot camp.

Two other influences weighed heavily on Dulli’s progressive

shaping of the Whigs into an explosive act that appealed to

both sexes. “I saw the Zen Arcade tour and it changed my

life. Hüsker Dü was something primal, really intelligent, and

overwhelmingly powerful and beautiful. I also remembered

that at lots of the punk rock shows I went to, there was a

35

preponderance of dudes. I remember thinking: ‘There are a lot

of dudes here. There’s got to be some way to have there be

not so many dudes.’ The answer to that was black music,

because you could dance to it. Girls liked it, pretty girls liked

it, pretty girls will stand in front of the dudes. That’s what you

want. A lot of hardcore and punk lacked sexuality. And I like

sexuality. And I like sensuality. When I first saw Prince, I

was [blown away]. I’d say the 1999 and Zen Arcade

tours—which I saw around the same time—while divergent,

were wildly similar and equally inspirational. You could say I

spent the rest of my life trying to reconcile those two

experiences.”

Before such enterprising ambitions took hold, the Whigs got

their ya-yas out. Stages doubled as spaces for wrestling

matches. Multiple occasions found members too liquored-up

to play. Equally stubborn, Curley and Dulli knew exactly how

to annoy each other. In Montana, they stopped the van on the

side of the road, got out, and brawled. At a show at Bunratty’s

in Boston, Curley smacked Dulli upside the head with the

headstock of a bass. Dulli retaliated by taking off his guitar

and dropping Curley with one punch. The melee continued

backstage, where the promoter informed them they hadn’t

fulfilled their contractual commitments and needed to

continue if they wanted their pay. The Whigs had no choice.

No money meant they’d be marooned.

And as they did that night in Massachusetts, the group split up

countless times. Even as Dulli was leaning on the band to get

serious, uncertainty ruled. “No one was paying attention, but

we broke up right before we got the call [to do the

seven-inch single] from Sub Pop,” recalls Dulli. “We went to

play one more gig.” That concert—a Wednesday night Rock

36

Against Depression show at Chicago’s Metro, which by then

had already made certain the band was a regular part of its

schedule—saved the Whigs.

“Sometimes you just get so excited about a band, or someone

in a band, or what they are doing as a band, that you work

hard to support and help and plan and plot and co-conspire,”

gushes Metro owner and early Whigs convert Joe Shanahan.

“We were like, ‘How much more can we do for these guys?

This has to continue.’”

Shanahan got his wish. Soon after having after-show drinks at

Smart Bar with Curley, Shanahan, and former Metro booking

agent Fred Darden, Dulli phoned Sub Pop co-owner Jonathan

Poneman: “Okay, we’ll do the single.” Days before, Dulli had

actually told the Seattle tastemaker no.

37

38

II. Bandwagonesque

Were the Whigs to emerge in today’s entertainment-obsessed

and information-overloaded age, they wouldn’t remain

unknown for long. Nowadays, a band, no matter how good or

bad, has to strive for anonymity or obscurity. And even then,

given the preponderance and enthusiasm of bloggers, they’re

unlikely to succeed.

But during the late 80s, attracting attention was a slow,

arduous process. No Internet meant that underground groups

didn’t have the fortune of happening upon a record deal,

posting a Myspace page, or being crowned Spin’s Artist of

the Day. Affordable home recording wasn’t yet an option.

Venues were scarce. Funds were nonexistent. Word-of-mouth

buzz, regional touring, and demo tapes did the heavy lifting.

A small network of sympathetic promoters, club owners,

managers, and labels was only beginning to develop.

“At the time, it was only Bob Lawton, Steve Carl, and our

agency,” remembers former Bulging Eye promoter Scotty

Haulter, who became the Whigs’ first manager shortly after

Dulli gave him a cassette at a concert. “There weren’t venues

in every town. People would rent out VFW halls or do shows

on whatever money they could scrounge up. It was really

exciting. You did it for a lot of different reasons.”

If anything, the challenging conditions weeded out lesser

bands given the fact that groups were forced to earn their due

rather than rely on unsubstantiated hype drummed up by

publicity teams. At the time Sub Pop first got word of the

39

band, the Whigs were getting about $100 per show, a case of

beer and, if they were lucky, a floor on which they could

crash. Not that they expected much.

At home in Cincinnati, every member save Curley roomed at

a mangy four-bedroom house at 2340 Flora Street. Doubling

as party central for the surrounding area, the Whigs’ version

of Fulton Street mirrored a low-rent frat house. A single light

bulb illuminated the porch. Rickety wooden stairs led to the

front door. Empty beer bottles littered the lawn. Rent totaled

$300 a month. And even with five guys—Haulter and a

rotating cast of associates bunked there to help keep bills to a

minimum—one man was always short his $60 share.

Amazingly, the accommodations represented a step up for

Dulli and McCollum, who had previously shared an

efficiency apartment.

The Whigs’ practice space was equally econo. Looking to

vacate Earle’s parents’ basement, they were invited by a

bohemian couple to play in a tarpaper house on the comer of

Luckey and Vinton. Despite the structure’s leaning angles,

broken

windows,

and

rotting

wood,

the

setback

location—snuggled in a hollow—was ideal. No one

complained about volume levels as the band worked up the

chops necessary to secure better time slots at local venues

such as Sudsy Malone’s, Jockey Club, and Bogart’s.

It was at one such show in 1988 when the Whigs scored an

opening gig for the Fluid, a Denver act that at the time was

the only non-Pacific Northwest band on Sub Pop’s roster. As

was typical for the cash-starved imprint, Fluid drummer

Garrett Shavlik served as one of the label’s unofficial talent

scouts. Liking what he’d heard at the concert, he mentioned

40

the Whigs to label honcho Jonathan Poneman, who told

Haulter to send off a demo tape. Despite agreeing with

Shavlik’s taste, Sub Pop didn’t act immediately. The label

wanted to keep its exclusive Northwest focus. Striking a deal

with the Whigs would compromise the balance.

Finally, an intern convinced the powers-that-be that

something needed to be done. A 45-RPM single for Sub

Pop’s Singles Club made the most sense. Poneman extended

the offer, which came with an invite to play a show at

Seattle’s now-defunct Squid Row club. While most bands

would’ve drooled over such an opportunity, the Whigs took a

wait-and-see approach. A sizing-up courtship dance between

the broke label and the equally broke, little-known band

ensued.

“I think all parties involved wanted to see what the other had

to offer,” admits Poneman. ‘“So you’re Sub Pop, huh? What

the fuck’s up with you?’ ‘You guys are hot shots from

Cincinnati? What the fuck are you all about? And why the

fuck do you live in Cincinnati?’ It wasn’t anything hostile.

Everyone just wanted to see what the other party had to

offer.”

“We did the single [‘I Am the Sticks,’ limited to 1,500

copies] and went out and played,” says Dulli. “And those

guys are like, ‘You should move to Seattle.’ And we’re like,

‘No.’ And they’re like, ‘Maybe we’ll call you.’ And we’re

like, ‘Alright.’ I think [it was] the fact that we said no at first

and then said we won’t move out there. It probably was basic

human nature:

41

Our resistance made us more interesting.” That and a potent

show in front of just twenty people led to a Sub Pop deal—the

first for a band east of the Rockies.

“The thing that sold me was passion, great songwriting, a

very spirited vocal delivery, and a fucking incredibly intense

live performance,” explains Poneman. “[And] Greg’s

song-writing. He was and remains a great lyricist and the sort

of singer, particularly in the live context, which is riveting.

He really had a soulfulness. Not soulful in an R&B context,

but something where you felt like he was really exorcizing

some demons and really pouring out his heart in his vocal

delivery. It was somewhat evident in those early demos but it

was so completely front-and-center when we saw them

perform. They were very much a band with a point of view

and cohesion. Those guys, early on, really were like

brothers.”

The bond extended to how the band coughed up the money

for a lawyer at the contract signing. “Part of the payment was

a bag of quarters—literally. Unrolled. But we put rollers in

there, so he could do it,” laughs Dulli, who was then working

odd jobs as a painter, roofer, cook, photo technician, and

cabbie. “Those quarters might have come from Earle, who

took them from his dad, who did candy machines for a living.

Then we had a bag of quarters in the back of the van to beat

somebody in the head with in case they tried to steal our shit.

We were fucking classy.”

Classy enough to meld in with an enviable roster of misfits

that included a lanky quartet singing about a girl named

Sickness being hounded by crotch-sniffing dogs (Mudhoney),

a butcher howling about drunkards driving a pickup on a

42

barely frozen lake (Tad), and a band bemoaning a broken

heart while lauding masturbation (Nirvana). Fitting

in with the label’s grunge sound would be another matter.

Like nearly every Sub Pop album made in the late 80s, the

Whigs’ Up in It was cut with the label’s inhouse producer,

Jack Endino. During the week in September 1989 when the

band recorded at Reciprocal Recording studios, everybody

slept on Poneman’s floor. Noisy and boozy, the record

confirmed the group’s Midwestern rock/post-punk influences

and effort to blend in with Sub Pop’s murky rawness. Still,

there are faint hints of the soulful and lyrical elements that

would later blossom. And right from go, the Whigs played

more notes—and more dynamically—than their peers.

“I was trying to fit in with the Sub Pop sound,” admits Dulli.

“So things got faster, things got heavier. Although a couple of

songs—’Son of the South’ and ‘Southpaw’—Sub Pop hated.

They were like, ‘You can’t put those on there.’ I’m like,

‘Fuck you, man. Watch.’” Sounding apart from anything Sub

Pop had ever released, “Ciaphas” was a tune Dulli didn’t even

try to sneak by the style police. Endino warned the band

ahead of time. “We tried to record it for Up in It and Endino

said, ‘There’s no way they’ll go for this.’” The song would

reemerge four years later with new words and a new title:

“My Curse.”

“Up in It was very consciously a Sub Pop—styled grunge

record,” says Poneman. “They had a lot of other things going

on musically but recording with Endino, the whole

presentation was something they had tailormade to fit our

vibe. That’s not to say the songs wouldn’t have been that way

anyway; they were more conscious about that sort of thing.

43

With the later records the R&B thing really started to emerge.

The one thing I remember about the Afghan Whigs and Up in

It in particular is that we had, up to that point, really nailed it

with our graphic identity.”

Frequently

distinguished

by

Charles

Peterson’s

black-and-white jacket photos and symbolic cover art, Sub

Pop albums were instantly identifiable and of the moment.

Because of the label’s aesthetic reputation, the Whigs

surrendered control of the artwork and almost immediately

regretted the decision. Perhaps confounded by the band’s

singularity, the label choked. Dulli recalls the ugliness.

“The arm was going sideways. It had not been airbrushed at

all. The back was an orange-and-black nightmare. The

lettering was orange on the front. We were fucking mortified.

I came up from Key West and we were starting the tour. I

remember calling [Sub Pop] from a pay phone and going, ‘I

fucking hate you. Look what you did to us.”’

Dulli quickly stepped in and orchestrated a redesign. While

some first-edition copies still circulate, the refurbished

cover—featuring a vertical arm on the front and, on the

flip-side, Curley’s bracing black-and-white snapshot of a

young, defiant black girl leaning on a stereo speaker standing

in front of a weathered Cincinnati building tagged with

FUCK YOU graffiti—prevented the Whigs’ debut from being

the worst-looking Sub Pop album in history.

No design problems plagued 1992’s Congregation, whose

commanding cover image—a nude African-American woman

holding a crying, white, equally naked baby girl while seated

on a dark red blanket—suited the band’s increasing

44

incorporation of black influences. The thought-provoking

picture (the flipside art depicts the same pair staring upward)

can be interpreted as a metaphor for black music existing as

the birth mother for every style that followed. It could also be

an extrapolation of the undefined albeit twisted relationship/

racial issues broached on the title track of the band’s 1990

“Sister Brother” single, a song whose twinkling piano accents

hinted at the group’s creative growth.

Less than two years removed from Up in It, Congregation

drastically improved upon the former in the areas of

songwriting, diversity, and subtlety. Without forsaking their

rambunctious rock roots, the Whigs latched on to the funk,

swagger, eroticism, and innuendo that would from then on

distinguish them from all comers. Arrangements reflect a

pronounced shift toward soul and McCollum’s riveting slide

guitar work. “I can’t recall yet if I’m black or if I’m white and

wrong,” Dulli staggers on the title track, the lyric seemingly

anticipating the passionate reactions that awaited the band’s

fusion of North and South via Southern soul smoothness,

garage bluster, and hip-swaying soul.

Congregation’s role in the Whigs’ evolution isn’t restricted to

the band’s gradual development of its own sound. Apparent

from the start of the brief mood-setting intro, the record

marks the beginning of the Whigs viewing albums as a

unified construct—a concept they enhanced and perfected on

Gentlemen. Dripping with hedonistic desires, Congregation

also witnessed the band’s brotherhood tighten via an unlikely

source.

McCollum explains: “The major bonding thing in

Congregation was that all three [Curley, Dulli, McCollum] of

45

us knew Jesus Christ Superstar. I listened to it a lot when I

was five or six. It was that Catholic thing. We were all

Catholic boys growing up. That suppression. At the same

time, we had the most evil thoughts in our heads but tended to

laugh about them. It was something that separated us from

other people and other bands.” That the band ironically

happened to rehearse Congregation’s lustful material at Our

Lady of Perpetual Help—a shuttered church/convent/school

complex located

directly across from a field where Pete Rose played Little

League—had to have only helped matters.

Like McCollum, Dulli also took to Jesus Christ Superstar as

a boy after hearing his babysitter play the record. The group’s

decision to cover the rock opera’s flea-market-evoking “The

Temple” on Congregation is concurrent with Dulli inhabiting

the guise of a glorified pusherman over the course of the

album’s thirty-nine-plus minutes. Here is where his oversized

ego and oversexed personality first appear. Like the

merchants in “The Temple” who believe they’re bigger than

Jesus, the singer embraces a bacchanal identity. Too much of

everything isn’t enough.

A stream of searing one-liners, titillating imagery, disposable

admissions, and lewd proposals make evident that Dulli has

settled into the role of devil’s plaything—and philanderer. His

intentions are illicit and insidious; scruples and morals don’t

enter his vocabulary. There’s no need or want for absolution.

As such, the predatory invitations (“Tonight”), submissive

behaviors (“I’m Her Slave”), dominating assertions (“Conjure

Me”), manipulative persuasions (“Let Me Lie to You”), and

scathing put-downs (“Dedicate It”) find him in control.

Dulli’s conscience is clear—or, at the least, any guilt is

46

couched too far back in his mind to matter. He’s too busy

making the rounds (“It was all just meat to me / You were

only meat to me,” he coos on “This Is My Confession”) to

ponder any personal culpability, embarrassing shame, or

equitable blame. After all, all is fair when playing the field.

However steeped in callous circumstances and cunning

maneuvers, Congregation is as compunction-free as the

frontman is lascivious. The self-loathing and self-reproach

would wait.

So would the band’s label—for a pair of eleventh-hour

additions, one of two similarly timed fateful twists that would

alter the group’s fortunes. “We’d already turned in the

artwork,” explains Dulli. “I remember calling Poneman and

saying, ‘I’ve got two songs I have to record. One of them has

to be on the record. It will just be uncredited at the end.’”

The feverish song, “Miles Iz Ded,” and its memorable “Don’t

forget the alcohol” chorus, served as the consummate finale to

an album that reintroduced carnal delights—and the enticing

prospect of getting into the opposite sex’s pants—back into

an indie-rock era primarily defined by angst, depression, and

downers. Dulli’s other last-minute idea, an invigorating cover

of the Supremes’ “My World Is Empty Without You,” had an

even greater impact. As the B-side to “Conjure Me,” it

became the band’s breakthrough in England.

In addition to the songs, the other unexpected albeit

unsurprising

development—Sub

Pop’s

dire

financial

straits—forced Dulli to change his address. While the band

recorded Congregation in July and August 1991 at a

professional studio in Woodinville, Washington, mixes and

overdubs were handled in California’s Sun Valley—an

47

outpost as sweltering as the town’s name implies. “That place

was like a jail cell,” says Curley. “Greg’s sentence was a little

longer than mine. I got paroled early back to Cincinnati.”

“That was right when Sub Pop ran out of money,” sighs Dulli,

who suddenly found himself stranded outside of Los Angeles.

“I was supposed to be able to get the money to go home but

they didn’t have any money for a plane ticket or a rental car. I

was stuck. I had to get a job. I moved in with my girlfriend.”

She would soon be immortalized.

48

49

III. Rebirth of the Cool

“The Congregation tour was the beginning of people coming

to see us and selling out places because the Afghan Whigs

were playing. We were starting to get something going:

getting good reviews, having a lot of good shows, going back

to places we had played before, and playing bigger places.”

Like every member of the Whigs, John Curley fondly recalls

the group’s late 1991 to mid-1993 tours. But the bassist

admits that they were on the road for so long—the band

crisscrossed Europe and the States multiple times—he can’t

remember specific details. Neither can Dulli. The vocalist

estimates that the Whigs played between 230 to 240

concerts—a staggering number considering that, save for a

few exceptions, the band, soundman Steve Girton, and a

manager tooled around in a van while towing a trailer full of

gear.

And nothing tests a band’s will like being cramped together in

a van for weeks at on end, always seeing the same faces,

killing down time between shows, and rarely getting any

privacy. When they could afford a cheap motel, logistics

dictated that only two people got their own beds. Under such

duress, a group’s bond either strengthens or everyone comes

out hating each other’s guts.

For Dulli and Curley, road life meant long shifts behind the

wheel. Earle only drove when supervised. In Oregon, he took

off from a gas station with the pump still attached to the

vehicle. On another occasion, the drummer landed in the

50

wrong state after everyone else had fallen asleep. McCollum

was permanently barred from chauffeur duties due to the fact

that he’d gotten in a wreck in his own driveway. That allowed

plenty of time for playing pitch, reading, and listening to the

radio, with Dulli absorbing tunes to work into the band’s

ever-evolving live sets.

While the Whigs never lacked for onstage chemistry, the

Congregation tour witnessed the band transform into the kind

of supremely taut—albeit spontaneously loose—well-oiled

machine that Dulli revered about James Brown’s old groups.

Such mastery only comes from collective experience and

playing in front of crowds night after night.

“You get to know each other so well, you can almost read

each other’s minds. It becomes almost telepathic,” says Earle

of the band’s knack for both flexible changes and tight

grooves. “That’s what I found what happened with John. It

also comes from growing up on some of the similar

influences and going where the other person would assume

you’d go with the riff.”

For the microphone-phobic McCollum, concerts became

outlets for self-expression. “I always stressed in the back of

my mind that there is nothing more boring that watching

someone holding a piece a wood and playing something.

After a certain point, the guitar has to be an extension. To be

able to

be lively onstage was the main thing I wanted to do. That’s

the only place I became extroverted: onstage with the guitar

on me. I had this little bubble around me but at the same time,

I’d connect with the audience and make it feel like I’m not

from this world. Not to have to look at your guitar when

51

you’re playing [becomes] second nature. This is a person up

here with just an extension of his body that’s playing and

writhing with the beats. It makes for a more interesting stage

show.”

“Rick really shines when he thinks no one is paying attention

to him,” adds Curley. “As soon as he thinks you’re paying

attention or looking at him, he starts doing it differently. But

when he’s just over there doing his thing and he thinks no one

is paying attention, it’s magic.” With McCollum surprising

from the shadows, Earle bringing up the rear, and Curley

functioning as the soldering agent, Dulli pushed it all over the

edge.

“You get good or you go home,” says the singer, describing

the Whigs’ anything-goes shows and cover-song mash-ups.

“You either evolve and make it fresh to yourself every night

or you’re fucking dead in the water. You’re a cover band. It

would be as simple as ‘I heard this song on the radio on my

way here and this kind of sounds like that. Or this would fit

over that.’ You’re sharing with the audience, who clearly

knows the song too. It’s as simple as making someone smile

out of recognition in the audience. You’re connecting.”

No two shows were the same. Performances reacted to the

crowd’s moods, the day’s headlines, and the city’s locale. As

the band’s interplay advanced, Dulli’s legend as an

uninhibited frontman who bantered with the crowd, took

requests, challenged hecklers, blew cigarette smoke in

people’s faces, called out lackadaisical concertgoers, quoted

popular song lyrics, dished on the history of rock and roll,

offered up opinions

52

on pop culture, and acted as the superlative ladies’ man began

to spread. So did the Whigs’ reputation for stringing together

smart medleys that sandwiched their own songs around

related covers.

The band’s affinity for Motown and Stax, as well as its

unabashed love for great pop hooks, surfaced nightly in

extended versions of “Turn on the Water” and “You My

Flower.” Partial renditions of tunes such as the Beach Boys’

“Surfer Girl,” the Shirelles’ (via Carole King and Gerry

Goffin) “Will You Love Me Tomorrow,” and the balladic

standard “Blue Moon” helped establish mood, underscore

irony, and eradicate tension. The soul music excursions,

seat-of-the-pants improvisations, and candid dialogues were

as foreign to the grunge/shoegazer era as the Whigs’ visual

appearance.

Never known for flying the flannel, the band made a

deliberate attempt to stand apart from the alt-rock scene,

whose fashions were already being exploited by national

retailers. For the Whigs, ripped jeans, tennis shoes, rumpled

T-shirts, cutoffs, and long hair were out. Formal

button-downs, suit coats, turtlenecks, the color black, and,

most noticeably, short hair were in. Just as grunge bands’

scraggly looks seemed congruent with their fuzzy distortion,

the Whigs’ stylish makeover paralleled their increasing

panache and sophistication.

Dulli recalls waking up one morning in Basel, Switzerland,

after having passed out drunk the night before. “There

obviously had been a party in my room. There was a naked

girl in bed with me. As I got up, there were booze bottles

everywhere. CD covers with smeary shit on them.

53

Overflowing cups of cigarettes. And a garbage can filled with

bottles with hair all over them. I’m like, ‘Wow, somebody cut

their hair.’

And then I went like this [brushes his hand through his hair],

and I’m like, ‘Oh god, it’s me!’

“I remember that it upset some people. Looking back on that

gang, I was kind of the first dude to cut his hair. I remember

thinking about David Bowie. He would be one thing and then

he would not be that. And then Prince. I’m like, ‘Let’s draw

the line between us and the flannel bands right now.’ It was

conscious and calculated. And entirely successful.”

The Whigs also benefited from the seemingly overnight sea

changes

occurring

within

the

music

industry.

The

Congregation tour overlapped with college rock’s categorical

mutation into alternative rock. Bands that had struggled to fill

small clubs were now headlining big theaters. Heavy metal,

butt rock, and overproduced pop died quiet deaths. MTV and

radio stations switched up their formats and playlists to

incorporate the new sounds, even though many of the day’s

leading bands—Soundgarden, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains,

Faith No More included—played a hard-rock style not far

removed from what was deemed outmoded. Seeking to cash

in on a trend and disguise their late-to-the-game ignorance,

major labels opened up their wallets and scrambled to fill

their rosters with acts that had any connection (real or

imagined) to Seattle. For artists being wooed by the big boys,

there was no better bartering chip than being tied to Sub Pop.

“Every label wanted to sign a grunge band from Seattle,” says

Curley. “They wanted a Sub Pop jewel in their crown. We

were straight with everybody, but those guys had so much

54

money. My god. The only time they spend it on you is when

they’re trying to get you to bed. Once you put the ring on, the

money stops and the accounting starts.”

Dulli was also mindful of the wining-and-dining stakes.

Not one to suffer fools, he recognized that the mad signing

spree was like nothing that had ever occurred in history and,

therefore, was unlikely to happen again.

“I was really conscious of the shelf life of that sort of

spending frenzy. I flew around for a while and talked to

everybody. I did a bunch of stuff I always wanted to do,” he

says, naming visits to swank hotels, meals at four-star

restaurants, and dugout seats at Yankee Stadium. “I wasn’t

being disingenuous. They were calling me, and I was the

manager of the band at that point. We had no manager. I did

all of the meetings. I helped draw out the contract. And I did

not take a percentage. That was my fringe benefit. There was

a degree of calculation going on. And it wasn’t a one-way

calculation—they were calculating too.”

In the end, Elektra won out over the other dozen-plus suitors

because of personnel, size, and repute. “We signed with

Elektra because we had somebody there that had been a fan of

the band for a long time and supported us coming up,”

explains Curley. “He had the support of the president, it was a

small company, and they had put out great rock records in the

past. We felt we were going to be part of something that was

going to continue to be what it was.”

Dulli concurs. “It was the smallest label. The other labels

were so massive. Getting lost in the shuffle was uninteresting

to me. Elektra did Ween, Metallica, the Cure, and Jackson

55

Browne. They were wacky. They had Björk! I liked the

eclectic nature of the label and it had a cachet. And I liked a

lot of the people on the staff.” Chief among those the band

admired was President and CEO Bob Krasnow, who, upon

arriving at Elektra in 1983, downsized the bloated talent

roster to ensure that every artist received dedicated attention.

Despite Elektra’s

major label status, the Whigs became just one of a few dozen

acts on the imprint.

“Nobody dealt with the situation in a classier manner than the

Afghan Whigs,” says Jonathan Poneman, talking about the

band’s split with Sub Pop. “I remember Greg saying to me, ‘I

was just a boy when I came to the label and now I’m a man.’

It’s kind of a corny thing to say but the sentiment behind it

was very true. They made a very fair deal. They treated us

with an enormous amount of personal and professional

respect.” It’s no coincidence that, fifteen years later, Dulli and

Sub Pop teamed up again.

Released as an EP in October 1992, the Whigs’ final

recording for Sub Pop, Uptown Avondale, epitomized the

band’s soulful maturation. Haunted interpretations of Freda

Payne’s “Band of Gold,” Percy Sledge’s “True Love Travels

on a Gravel Road,” the Supremes’ “Come See About Me,”

and Al Green’s “Beware”—all deep tracks that address the

ravages of romance—spoke to how deeply ingrained R&B

had become in the band’s sound. In their own way, the Whigs

were paying tribute to and reviving a dormant Cincinnati soul

tradition that began in the 1950s with King Records, a local

“race music” imprint that recorded crossover singer Hank

Ballard, boogie-woogie pianist Ivory Joe Hunter, unsung rock

56

pioneers Roy Brown and Wynonie Harris, and, most

famously, a young James Brown.

Queen City natives the Isley Brothers and Bootsy Collins

carried the torch into the 1970s.

And just as Uptown Avondale’s R&B flavors heralded a

major advance, the EP’s pronounced “shot on location”

credits—it was recorded in early August at Cincinnati’s

Ultrasuede Studios, then located in a loft space above a

pottery shop at 4046 Hamilton Avenue—affirmed that the

narrative organization alluded to on Congregation had come

full circle.

“I began to see everything in a cinematic way where I’m

telling a story, whether it’s abstract or linear, it’s a personal

statement of cinema verite,” explains Dulli. “Coming from

my background of studying film and taking the viewer or

listener on some kind of journey, it started with Uptown. That

is the bridge between the two versions of the Whigs.”

Poneman agrees. “The Whigs went on to forge a unique

musical perspective. I think in the records that they did for

Sub Pop, they were really just starting out. Uptown Avondale

was just a segue between what they were doing on Sub Pop

and the more R&B-tinged stuff that was really going to define

who they were.”

To this extent, the band’s chilling reading of “Come See

About Me” served as a sonic harbinger. While Diana Ross’s

mood on the snappy Motown original is optimistic, the Whigs

shape her trio’s confident plea into a despondent call ridden

with dejection, loneliness, misery, and disgust. When Dulli

utters “hurry, hurry” at the coda, he barely manages to get the

57

words out of his mouth. He sounds as if he’s lying facedown

on the floor, overcome with defeat, and certain that his love

isn’t returning. He’s spurned, angry, crippled. Robbed of its

hopeful urgency, the song doubles as a disdainful

kissoff—albeit one on which the narrator, despite his wishes,

never gains the upper hand.

As “Come See About Me” intimates, absence may indeed

make the heart grow fonder but the endings aren’t always

happy. Too much time away stresses relationships by

triggering doubts, changing hearts, inviting temptations, and

hampering growth. Naturally, anyone that spends more than a

year away from home and tours the world is susceptible to

such circumstances and challenges. Succumbing to some

measure of debauchery is a foregone conclusion. Having the

foresight to understand the potential consequences isn’t

nearly as automatic. It may not even be part of human nature.

Dulli first met Kris in her native Louisville when she was

twenty. The two were smitten with each other at first sight.

She became his first adult love—and, ultimately, the first and

last girl he’d ever live with.

“We lived together for a year. But during that year I was gone

almost the whole time. Whereas my indiscretions were

random and on a semi-nightly basis, she was probably

seeking consolation with a bit more permanence. When I got

back from the third [leg of the] tour, that’s when she told me

she had hooked up with a new dude and he had been in our

apartment. ‘Wow.’ I think I reacted in the way someone

raised in a patriarchal family in Ohio would react. It was in

retrospect that I began a closer examination of my

contribution toward the dysfunction of the relationship and

58

the fact that I was being a hypocrite. I did what she did. I just

did it with numerous people and it was what it was. Then I

began to examine my own failings and why the thing went

down.”

59

60

IV. Now You Know

Sometimes you can go home again. After splitting with Kris,

Dulli moved back to Cincinnati and into a place on Stettinius

Avenue located across from the park. Withdrawn and

depressed, the singer entered a solitary soul-searching period

during which his cat served as his primary companion. He

upped his drug use, began to sketch out lyrics, and immersed

himself in the universes of Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks,

Marvin Gaye’s Here, My Dear, and Bob Dylan’s Blood on

the Tracks—not surprising given his fragile state.

Yet the record that received the heaviest amount of rotation in

Dulli’s apartment wasn’t a 33 1/3-RPM LP but an old-school

soul 45-RPM single seemingly lost to everyone but dusty

show deejays, R&B aficionados, and crate diggers. And even

then, the singer didn’t opt for the traditional A-side.

A chart-topping R&B smash and number-three pop hit in

May 1970, Tyrone Davis’s sweeping “Turn Back the Hands

of Time” is a song of longing, regret, and second chances.

Recorded for Dakar Records—a label that billed itself as

“The Sound of Chicago”—the tune is emblematic of Davis’s

enviable pairings of velveteen and vice, grit and groove.

Upon hearing his voice, you don’t need to see a picture of the

Mississippi-to-Chicago transplant to know that he was a

ladies’ man who proudly hung thick gold chains around his

neck, left his shirt unbuttoned at the chest, stuffed an oversize

handkerchief into the left pocket of his colorful smoking

jacket, and donned flashy pinky rings. According to producers

61

Leo Graham and Leo Sacks, despite his flamboyant

personality, Davis was a down-to-earth gentleman.

That helps explain why “I Keep Coming Back,” the B-side to

Davis’s biggest hit, sounds so sincere. On the surface, the

song (cowritten by Graham) is a crawling-back-to-you plea, a

tandem apology for mistreatment and declaration of true love.

Soul music is replete with myriad examples of such

confessions—the aural equivalent of a dozen roses and a box

of chocolate. But Davis’s on-his-knees proclamation goes

deeper. It speaks to a particular woman as an addiction that

the singer wants to drop but, like anyone caught in the throes

of a gripping dependency, lacks the willpower to quit.

Wasting no time, the song’s opening line—“I wanna leave

you / But I just can’t leave you”—clearly identifies the vexing

emotional push-pull, with the conflicted protagonist soon

opening up about having recurrent nightmares. It’s as if he’s

an alcoholic going cold turkey and sweating out the DTs.

Even though he knows better and wants to break free, his

candid reflections and vulnerable state cause him to realize

how badly he craves his partner. He knows that he screwed

up, but he’s not beneath begging, even screaming to return to

what he feels is home. Completely lovesick, he takes his most

serious oaths at the end of the song, swearing

his honesty and professing, “I lay down and die,” a sentiment

that can be read as both a barometer of pain and pledge of

selfless sacrifice.

Alternatively silky and ravaged, cool and embellished,

Davis’s performance makes it all utterly believable. Never

once does it seem that he’s going through the motions to

simply get back in his baby’s good graces as a way to bide

62

time while he continues to play the fool. Over a slinky guitar

motif, delicate brass accents, and Willie Henderson’s

sympathetic arrangement, Davis testifies like a junkie who

has hit rock bottom, mulled his mistakes, and is ready to

reform.

Dulli instantly bonded with the song’s message and vibe. “I

went to that song because it was my confessor, my friend in

the night. It was a comfort to me, a shoulder to lean on.” Not

that he had time for much consolation. The Congregation tour

placed the up-and-coming band back onto stages with little

room for any breaks. The demanding schedule also meant

that, for the first and only time in its career, the band would

have to write an album on the road. And while the foursome

had collaborated on all preceding projects, an unspoken

expectation within the group meant that the need for new

material fell to Dulli—a responsibility that, contrary to

perceptions and reports that made him out to be a self-serving

egomaniac, he didn’t invite.

“I never wanted to do that. I really didn’t. There was no

conscious ‘I’m taking over the band.’ To this day,

collaborating with people is one of my favorite things to do.”

Dulli hadn’t any premeditated plan or specific agenda when

he began writing for Gentlemen. While possessing such focus

helps shape concept albums, the approach also tends to

make them stiff, bloated, and restricted. Rather than come

together naturally, the results are forced to fit into a deliberate

schematic.

Spontaneity,

rebelliousness,

emotion,

and

looseness—bellwethers

of

great

rock

and

roll—are

compromised if not totally exhausted. For every Zen Arcade

63

and Southern Rock Opera there are a dozen Kilroy Was Here

and Music from ‘The Elder” debacles.

With the vocalist free from topical constraints, Gentlemen

revealed itself in an organic manner. The early emergence of

the title track functioned as the starting point to something

bigger. “I came up with the riff in Tampa and really liked it,”

recalls Dulli. “Everybody went to Clearwater to go

swimming. But I went back to the hotel and wrote, ‘Your

attention, please’ [the first line of the song] and all of that

stuff. I had a melody during the soundcheck and started

writing the words. I knew then that would be the album tide.”

Another verse was written en route to a hardware store; the

band was searching for a van part in swamp country.

“Fountain and Fairfax” soon followed. Dulli sensed that his

first batch of songs shared a similar vitriolic spirit, and

followed that muse when the band headed to Europe, where

he wrote a bulk of the album’s lyrics. By late August 1992,

the group was trying out early versions of “Gentlemen”

onstage. Trial runs often featured Dulli singing different

words or simply uttering gibberish to fill the space.

“A lot of times, I just scat lyrics,” he explains, accounting for

the sometimes-incomprehensible verses of yet-unreleased

songs heard on bootlegs. “It’s mostly phonetic sounds that

sound good to me. I write the words last. I come up with the

riff, I arrange the song, and then I’ll scat the melody on top of

the song. I’ve never written the words first in my life.

It’s all based on how the song is going to go, how am I going

to feel during the song.”

64

To anyone within earshot, there was no doubt about how or