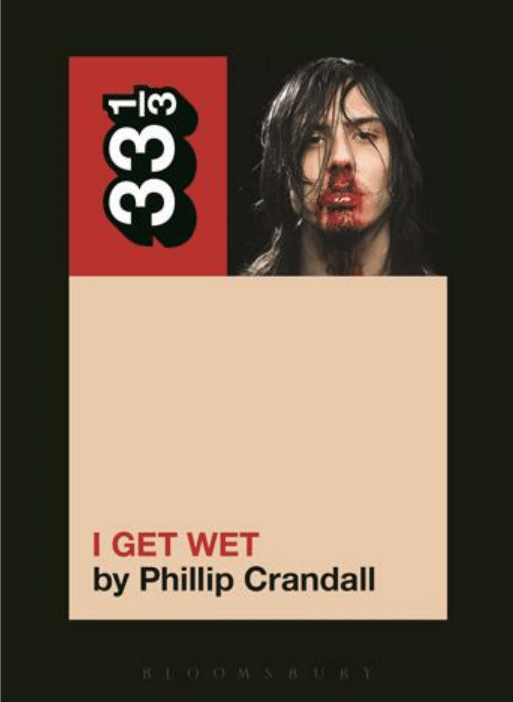

I GET WET

Praise for the series:

It was only a matter of time before a clever publisher realized that there

is an audience for whom Exile on Main Street or Electric Ladyland are as

significant and worthy of study as The Catcher in

the Rye or Middlemarch … The series … is freewheeling and

eclectic, ranging from minute rock-geek analysis to idiosyncratic personal

celebration — The New York Times Book Review

Ideal for the rock geek who thinks liner notes

just aren’t enough — Rolling Stone

One of the coolest publishing imprints on the planet — Bookslut

These are for the insane collectors out there who appreciate fantastic

design, well-executed thinking, and things that make your house look

cool. Each volume in this series takes a seminal album and breaks it

down in startling minutiae. We love these.

We are huge nerds — Vice

A brilliant series … each one a work of real love — NME (UK)

Passionate, obsessive, and smart — Nylon

Religious tracts for the rock ’n’ roll faithful — Boldtype

[A] consistently excellent series — Uncut (UK)

We … aren’t naive enough to think that we’re your only

source for reading about music (but if we had our way …

watch out). For those of you who really like to know everything

there is to know about an album, you’d do well to check

out Continuum’s “33 1/3” series of books — Pitchfork

For reviews of individual titles in the series, please visit

our blog at

333sound.com

and our website at

http://www.bloomsbury.com/musicandsoundstudies

Follow us on Twitter: @333books

Like us on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/33.3books

For a complete list of books in this series, see the back of this book

Forthcoming in the series:

Selected Ambient Works Vol. II by Marc Weidenbaum

Smile by Luis Sanchez

Biophilia by Nicola Dibben

Ode to Billie Joe by Tara Murtha

The Grey Album by Charles Fairchild

Fresh Fruit for Rotting Vegetables by Mike Foley

Freedom of Choice by Evie Nagy

Entertainment! by Kevin Dettmar

Live Through This by Anwyn Crawford

Donuts by Jordan Ferguson

My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy by Kirk Walker Graves

Dangerous by Susan Fast

Definitely Maybe by Alex Niven

Blank Generation by Pete Astor

Sigur Ros: ( ) by Ethan Hayden

and many more …

Andrew W.K.’s

I Get Wet

Phillip Crandall

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.

1385 Broadway

50 Bedford Square

New York

London

NY 10018

WC1B 3DP

USA

UK

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a registered trade mark of Bloomsbury

Publishing Plc

First published 2014

© Phillip Crandall, 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information

storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from

the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization

acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this

publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-1-62356-550-3

Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham,

Norfolk NR21 8NN

I Get Wet

Andrew W.K.

1.

“It’s Time to Party

” (1:30)

2. “

Party Hard”

(3:04)

3. “

Girls Own Love”

(3:13)

4. “Ready to Die” (2:54)

5. “Take It Off” (3:10)

6.

“I Love NYC”

(3:11)

7. “

She is Beautiful

” (3:33)

8. “

Party Til You Puke

” (2:34)

9.

“Fun Night”

(3:22)

10.

“Got to Do It”

(3:54)

11.

“I Get Wet”

(3:23)

12. “

Don’t Stop Living in the Red

” (1:40)

•

vii

•

Contents

Puke (Preface) viii

Ink (Introduction)

1

1. Perilymph

14

2. Juice

37

3. Sweat

60

4. Smoke

84

5. Blood

109

6.

ˈkəm 126

Ice (Interviews and Sources) 146

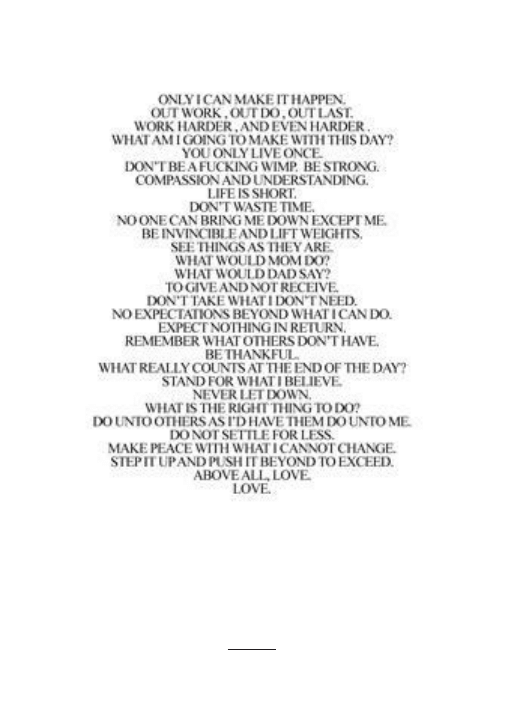

Stop Bath (Photographs) 152

Champagne (Acknowledgments) 156

9781623567149_txt_print.indd 7

26/11/2013 12:20

•

viii

•

Puke

Isn’t that fun?

—Wendy Wilkes

Andrew is standing on his Los Angeles kitchen floor,

but he could topple over in a projectile-heaving daze

any second now. Seeing his wobbly reaction playing out

exactly to script, Wendy Wilkes is ready with Step 2 of

her devious master plan.

As a girl growing up in northern California’s Bay Area,

Wendy spent 360-some days of her year ticking off boxes

until the next Walnut Festival. Commencing as summer

turns to autumn in Walnut Creek, the festival officially

celebrates the beloved crop whose groves replaced area

vineyards during Prohibition. Whatever the reasoning, it

was young Wendy’s opportunity to enjoy rides that only

got more twisty, twirly, and exciting with each passing

year. Wendy went on to study English during the Lew

Alcindor-era at UCLA, and, after graduation, train as a

paralegal during that profession’s infancy. There, she met

Jim Krier, a professor of law who would later co-write the

preeminent casebook, Property. In Jim, she would find love,

happiness, and a life confined to lame merry-go-rounds.

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

ix

•

“I quickly found out that this guy was not going on

any ride with me ever unless it stayed on the ground,”

Wendy says. “I was doomed.”

So when Wendy gave birth to Andrew in May

1979—“I was delighted to have a son,” Jim says, “[and] I

went home and told the dog we had a boy in the family,

then three hours later went off to teach”—the mother

saw, among many adorable first-child traits, a partner

in rollercoaster-riding. Shortly after Andrew learned to

walk, Wendy put her plan into action.

Wendy led Andrew into the kitchen and picked him

up, placing her arms under his tush and his arms around

her neck. Holding his body tightly against hers, she

began twirling around, hoping some vertigo would shake

his equilibrium to the diaper-donning core. After three

or four intense spins, Wendy bent down to stand Andrew

up on the kitchen floor.

If body language is any indication, this kid has no clue

what’s happened or why his body is responding accord-

ingly. He looks to his mom, who, as the spinner, created

this internal mayhem and perhaps has an explanation

as to why the dishtowels are waving. In this instance,

the dosage of spin needed to carry out Step 1—getting

a toddler dizzy—would not impair the spinner’s ability

to carry out the second and most important step of this

plan.

Allowing for the dizzy effect to make just enough of

an impression on the young brain, Wendy looks Andrew

in the eyes and, in a gesture quite opposite to bringing

him to barf’s edge, lays some comforting mother-voice

on thick.

“Isn’t that fun?”

I G E T W E T

•

x

•

The child, reassured by his mother’s acknowledgment

and approval of the feeling, laughs.

“Don’t you love that?”

The child, not unlike one who falls but cries only

upon being coddled with sad reactionary faces, laughs

some more. “Do it again!” Andrew commands.

The plan has worked. Little Andrew yearns to push

the limits of dizzying intensity again and again in that

kitchen. As boxes keep ticking, they take the game to

their new kitchen in Ann Arbor, Michigan. From there,

they’ll take it outside, where Wendy will hold Andrew

by the outstretched hands and spin until the earth blurs

below.

“Isn’t that even more fun,” she asks. “That’s so much

more fun than twirling with Mom holding you! You can

twirl way out there really fast.”

The child, instinctively now, laughs some more. And

when the child gets a baby brother, Wendy will repeat

the process.

“Each boy, same thing,” Wendy says, proud

of her efforts and thankful for a life not spent on

merry-go-rounds.

“They are perfect. They go on everything.”

•

1

•

Ink

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points

out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of

deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to

the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred

by dust and sweat and blood … who at the best knows in

the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the

worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that

his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls

who neither know victory nor defeat.

—Theodore Roosevelt, “

Citizenship in a Republic

”

Hey you, let’s party!

—Andrew W.K.,

“It’s Time to Party”

Andrew Wilkes-Krier is sitting in his wheelchair, ready

to puke, sweat, bleed, or pulverize even more unsus-

pecting bones if this live TV performance calls for it.

The network exec, seeing the energetic musician he

booked in this lame position, puts the kibosh on the

entire thing.

The accident happened weeks earlier on the

600-square-foot stage of the House of Blues, Los Angeles,

I G E T W E T

•

2

•

where Andrew W.K. was taking advantage of every

square-inch, running around joyously and carelessly as

usual. The band—consisting of the mic-clutching and

occasional keyboard-pounding Andrew, three guitarists,

a bass player, and only one drummer for now because

they wouldn’t get around to adding a second until the

following spring—is in the midst of its third circling of

the United States in six months, but the first full tour

(and West Coast show) since the follow-up to

I Get Wet

was released. Hyperactive as ever, Andrew is growling

the chorus to “Your Rules,” a song on the latest release,

but from Andrew’s earliest demos, that, when performed

on Late Night with Conan O’Brien weeks earlier, was

introduced by Andrew as a song “for anybody who has

ever believed in music.”

“We will never listen to your rules,” shouts the leader,

uniting an L.A. crowd that, throughout the set, will climb

up onto the stage and prance about the ever-shrinking

hallowed ground in a frenzied scene, still a trademark of

AWK shows. Chorus completed, Andrew leaps around

some more, charging himself up for his second-verse cue.

In doing so, he accidentally wraps his microphone cable

around his leg. As he explained on his website days later:

“That happens all the time, and I usually just dance my

way out of it, but this time when I came down from the

last jump … I got more tangled in his bass cable and I got

my foot pulled out from under me. At the same time that

happened my foot got rolled and crushed and twisted

and I fell over.”

Feeling a sharp pain but thinking nothing of

it—“twisted my ankle,” he wrote, “happens to me every

now and then”—Andrew powers through the rest of the

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

3

•

concert on pure adrenaline; no one the wiser, no song the

sufferer. It’s only when the lights come up and the rush

wears off that the subtle pain becomes a siren. Partying

produces yet another battle scar, joining on-stage head

injuries for the sake of the show and on-demand hemor-

rhaging for the sake of the legend.

Loaded into the ambulance, the hobbled showman

keeps the driver idling so he can sign every last autograph

request, a common post-show gesture he would later

push to its extreme in a 24-hour marathon signing

session in Japan. Once at the hospital, X-rays show he

shattered his right foot. His options: cancel the tour’s

remaining shows and rest at home for two months, or

perform while confined to either a bench, crutches, or

a wheelchair. Gnarly stage-wheelies are envisioned, and

shows, including Anaheim’s, less than 24 hours later, only

get rowdier.

“I just lock the wheels, and then hold on for dear life

as I try to whip myself back and forth with all the power

I have,” he would explain on his site. Fans who didn’t see

him seated in concert got to witness this wild ride on

Andrew W.K.’s live concert DVD,

Who Knows?

Edited

in a process called sync-staking, where clips from many

different shows were spliced together to create what

sounds like one seamless performance, the interwoven

wheelchair antics feel like a compilation of greatest spins,

slams, and spasms. Viewers who tuned in for the 2003

Spike Video Game Awards show were set to see it, but

then that exec stepped in.

“When they saw I was in a wheelchair they just

wanted me to cancel,” he told the

Guardian

in the United

Kingdom in this unedited, clearly British-ized interview.

I G E T W E T

•

4

•

“They said: ‘No it doesn’t look good, there’s a reason

why you don’t see people in wheelchairs performing on

telly!’ I was just baffled by that and then I realized, holy

smoke, you really don’t see people in wheelchairs on

television! Why the fuck is that?”

The network relented, and the national audience did

get to see the band crank through a medley that gets its

largest response when Andrew declares, “When it’s time

to party, we will party hard”—the inviting intro line to

his debut’s breakout anthem, “

Party Hard

.” His charis-

matic vessel, compacted by his own reckless abandon,

develops an even stronger gravitational pull.

“Afterwards the guy apologized, he said he was wrong,

the show was amazing and thanks for doing it,” Andrew

told the

Guardian

. “I realized if you’re injured it’s not just

getting around that changes, it’s the whole way you’re

treated.”

No rock cliché—lesson learned the hard way,

collateral bodily damage, the show having to go on—has

ever resulted in such incredible footage. “I didn’t know

if people we’re going to like it,” he confessed on his

site, “but me and the band just slammed it as hard as we

possibly could. In honor of everyone who never gets the

chance. In honor of everyone who has to be in a wheel-

chair forever.”

“In honor of all those left out and discriminated

against and told no, we slammed.”

***

“

It’s Time to Party,

” the first track off

I Get Wet

, opens

with a rapid-fire guitar line—nothing fancy, just a couple

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

5

•

of crunchy power chords to acclimate the ears—repeated

twice before a booming bass drum joins in to provide a

quarter-note countdown. A faint, swirling effect inten-

sifies with each kick and, by the eighth one, the ears

have prepped themselves for the metal mayhem they

are about to receive. When it all drops, and the joyous

onslaught of a hundred guitars is finally realized, you’ll

have to forgive your ears for being duped into a false

sense of security, because it’s that second intensified drop

a few seconds later—the one where yet more guitars and

instruments manifest and Andrew W.K. slam-plants his

vocal flag by screaming the song’s titular line—that really

floods the brain with endorphins, serotonin, dopamine,

and whatever else formulates invincibility.

***

A pianist sits down to his instrument and plays an

original piece. When the song is over, a man approaches

the pianist and says, “Tell me about the song and what it

means to you.” Without saying a word, the pianist simply

begins playing the song again.

It’s one of a few parables Andrew has offered when

asked about his music’s meaning. Perhaps “playing the

song again” is his practical, albeit less punchy, spin on

that dancing-about-architecture chestnut. Or perhaps it’s

gentlemanly tact directed toward an enquirer who wants

to know what a song entitled

“Party Til You Puke”

truly

means.

The purpose of this book will be to provide context

for the

I Get Wet

experience as a whole, not to interpret

or over-intellectualize its individual songs. The album

I G E T W E T

•

6

•

was a polarizing sensation when it debuted, first in

Europe in 2001 and then in North America in 2002.

It didn’t capture the zeitgeist of rock at the turn of the

century; it captured the timeless zeitgeist of youthfulness,

energized, awesome, and as unapologetically stupid as

ever, and that created immediate deriders. Implying

some unspoken political message to each song’s lyrical

text wouldn’t reaffirm polarized positions; it would drive

both polarized camps to disgust.

***

Andrew tells me this album isn’t about him, a perfect

sentiment reaffirming both the feelings I brought in and

the ideal I wanted to uphold. As a fundamental principle,

I wanted to avoid telling my story in this book; to put it

another way, I wanted to avoid the word “I.” His mother’s

story about rollercoaster-prep and dizzying context made

me reconsider.

Depending on what you’re bringing to this author–

reader endeavor—and, in the truest spirit of this album,

all readers regardless of backgrounds are invited—the

stories within this book may offer twists and twirls you

feel uncomfortable with. That could be as innocent as

references made to unfamiliar people, bands, or genres,

or as disorienting as entire topics that have little to do

with your

I Get Wet

enjoyment. I’m not just spinning you

around the kitchen now; I’m actually pointing out things

to look at on the side. I’m curating someone else’s life

and work (Andrew’s) and contextualizing someone else’s

experience (yours). You should probably know two things

about your spinner:

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

7

•

1) I snatched my car keys the moment the “Party

Hard” video credits rolled so I could go buy the CD. And

the first time I saw Andrew W.K. play, I was so overtaken

and lost in euphoria that, afterwards, I couldn’t remember

a single between-song sentiment Andrew shared with us,

only the added bonus excitement that context instilled.

Those feelings are sacred and that context incredible,

and this book shall henceforth lean heavily toward the

latter.

2) I have no room in this book or reason in my heart

for showy prose or superfluous reference making. If a

passage seems daunting, I assure you it’s there for the

bigger picture or some pending payoff. As one who reads

these books hoping for the same courtesies, I’ve always

felt the only place a dredging of this magnitude can come

from is out of love in its purest form.

***

Pitchfork

gave

I Get Wet

an abysmal 0.6 rating when

it came out—“Maybe Y2K really was Armageddon,”

the reviewer wrote, “and maybe Andrew W.K. is just

the first of four pending horsemen”—then, at the end

of the decade, named it one of its Top 200 Albums of

the 2000s. (In a review packing the phrase mea culpa

in the first sentence,

Pitchfork

gave the 2012 reissue an

8.6.) Talking about Andrew W.K. bred polarization and,

interestingly, self-reflection. Three gentlemen debated

“the death of irony” for

Ink 19

shortly after

I Get Wet

’s

release. Christopher R. Weingarten, the topic’s broacher

and eventual 33 1/3 author, asked: “If he is indeed being

ironic, should he be reviled for being a gimmicky jape?

I G E T W E T

•

8

•

Or revered for being a brilliant appropriation artist? If

he is indeed as serious as he says, should he be lauded for

creating visceral body music? Or derided for cock-rock

arrogance?” The rebuttals painted Andrew’s music as

“icky bubblegum metal (with umlauts over the ‘u’)”

and unworthy of any conversations, period. Eventually,

the debate broke down over its impenetrable layers of

arguing about irony arguments—“I made no argument

whatsoever as to whether the work of AWK is or is not

ironic,” wrote rebutter M. David Hornbuckle. “My main

point is that he sucks”—but Weingarten’s questions

about post-modern enjoyment based on artist context

are still interesting, especially since Andrew’s celebrity

only got larger in the decade that followed

I Get Wet

.

Andrew W.K. sends out “Party Tips” to his social-media

followers. He helped a fan throw a birthday party on one of

the television series he hosted. He opened a nightclub called

Santos Party House in New York City. He gives slightly

re-phrased, often verbose mission statements to anyone

who will give him a platform (“My personal mission, my

goal, my life’s work is to not only discover myself, but to

discover what that self of my own is meant to do,” he told

a Pepperdine newspaper, “and so far, and I could be wrong,

but so far it is to party”) then resorts to ALL CAPS simplicity

for his online profiles (“ANDREW W.K. = PARTY”). If the

man didn’t have such a defined outer shell—unwashed

white jeans, unwashed white T-shirt, unwashed hair—you’d

envision him wandering the streets with nothing but a

megaphone and a sandwich board, “Party Party Party”

spray-painted in blood red on both sides.

What makes Andrew’s “play the song again” anecdote

such an odd, yet beautiful sentiment is that he does

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

9

•

have a crystal-clear message outside the confines of the

I Get Wet

vinyl groove, one he’s absolutely hell-bent on

sharing with the world. Man-at-the-piano Andrew is in

the camp that music should speak for itself, regardless of

context, but to even be aware of that opinion, you would

have had to read an interview with the artist, the mere

intake of which is proof that artist-contextualization

is unavoidable. The only music without any context

comes on some universal, unlabeled medium, left at your

doorstep by an anonymous stranger.

Andrew’s extracurricular activities have been consistent

and complementary to the

I Get Wet

spirit, with charisma

in lieu of melody driving the message home. Asking

whether that drive is serious or ironic says more about

listener expectations than artist intent.

***

“The true book of the meaning of life has one blank

page.”

Oh, there are paradoxes aplenty in the Andrew W.K

story. This book will shine light on a few of them, while

paradoxically providing one of its own.

At some point you will put this book down, be it

after the next damned brain-wrinkle or when the final

word on the final page is read. Regardless of when that

happens, rest assured that this book did not nor can

it tell the definitive history of Andrew W.K. and the

making of

I Get Wet

. As your trusted curator, I’ll admit

up-front that we—that is myself, Andrew, and all of his

family and friends quoted within—didn’t discuss every

aspect of Andrew’s art and life, to say nothing of the

I G E T W E T

•

10

•

choices I alone made about which discussed aspects

were highlighted and which were deemed expendable.

Throughout these highlights, I’ve taken particular care

to qualify statements and credit sources out of respect for

the subjects discussed, the person quoted, and collateral

parties who might be unable or unwilling to verify each

and every account.

There will surely be detail oversights and ideas under-

developed, and it’s a shock that any book would claim

success in telling a complete story. No one wants to be

easily summarized, and the above disclaimer is as close

as I can get to extending the luxury to an artist and an

album so befitting and deserving. If I may try to wrap

Andrew W.K.’s personality up in a nice little bow, it is

one resolute on destroying nice little bows from within.

(It’s also one of complete generosity; he volunteered his

time and energies for this project in humbling ways, and

was beyond candid way more than 93 percent of the

time.)

I couldn’t help but think about my historian hang-ups

when I first read that blank-page, meaning-of-life quote;

it was buried in an article about Scream 2 in Andrew’s

WOLF “Slicer” Magazine, a creation of genius we will get

to in due time.

***

The first two chapters will cover some of the art Andrew

created prior to

I Get Wet

, including his teenage efforts

in Ann Arbor and the EPs he made in New York City

that would hint at the bedlam to come, while the third

chapter takes an in-depth look at this album’s recording.

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

11

•

Andrew told

Rolling Stone

, “Thousands of hours were put

into making sure that the songs didn’t sound like they

had thousands of hours put into them.” What resulted

was a focused, singular sound that never decrescendos,

with effects and overdubs more ambitious and far

cleaner than the metal genre had ever heard. Ionian and

mixolydian scales have been used to pop-ify music for

years, but

I Get Wet

’s unrelenting use of bright keyboards

and piles of guitars to carry the blissful melodies is its

irresistible signature. Its layered sound confronts with

volume and texture, but not in gruff distortion, face-

contorting guitar solos, or false machismo. It gets labeled

as metal, but there’s clearly something distinct about

his particular brand that seems to eschew the defining

guidelines. The derider in the

Ink 19

debate called it

“icky bubblegum metal,” and if you ignore the subjective

four-letter adjective, one could rationalize the longer one.

The bubblegum descriptor carries with it damning

connotations of being easily consumed and disposed,

appealing to those with yet-to-develop tastes and

overflowing piggy banks. That’s not necessarily an

incorrect sentiment, but it disarms the word of any

redeeming qualities, of which

I Get Wet

boasts many.

“Unlike all the astral-planing acidwreck dreck you were

soon burning out to, bubblegum laid all its cards out, not

disguising itself as anything (i.e. ‘smart’) it wasn’t,” wrote

Chuck Eddy in the pages of an 1987 issue of Creem.

“You didn’t have to study these hooks paramecium-like

under a microscope or anything; they were so blatantly

cute on the surface you just wanted to tickle ‘em under

the chin. Which is fine, because rock’s not supposed to

require much thought.” Andrew’s chin may be soaked

I G E T W E T

•

12

•

with blood, but the urge to jump up on his shoulders and

take in—and take on—the world from his point of view

is just as alluring.

Interestingly, the album shares some of bubblegum

music’s more subterranean, shadowy characteristics

as well. The genre exploded in the late 1960s with

songs like “Sugar, Sugar,” created by faceless writers

and musicians who could remain hidden behind the

cartoonish characters—literally and figuratively—

that made up the bands (in this case, The Archies).

Abbreviations and amazing aliases abound throughout

I Get Wet

’s liner notes, effectively staging the first

dominos that, some say, cast shadows on Andrew the

Artist. Those who crack this spine asking only the banal

questions may not find the shade of some of the answers

as satisfying as I do.

The fifth chapter will look at the bonds created in I

Get Wet’s aftermath, and the sixth will put this album,

those bonds, and this shared experience in a perspective

that will hopefully prove both fulfilling and full of

potential, more than any blank page ever could.

***

Every time, without fail, the brain has to weather the

same flood of sound, chemicals, and emotions when

confronted with that first

“It’s Time to Party”

decla-

ration. As it takes a second to find its aural orientations

in the head, his chant becomes even more insistent. “Hey

you, let’s party!” With this invitation, you, the listener,

have hereby joined forces with Andrew W.K. on the

party front. And you are not alone.

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

13

•

Despite the first-person singular pronoun in the

album’s title, the

I Get Wet

experience is a shared one

between artist and audience. You’ve been invited right

off the bat and, in the first verse, told “we’re gonna have

a party tonight.” This isn’t an us-versus-them narrative

dynamic; it’s an inclusive, “we” for the sake of “we,”

potential-filled promise that finds its way into most

tracks literally and all tracks spiritually. And it’s the only

kind of party and fun we want.

“We” isn’t a revolutionary narrative device, but in the

hands of Andrew W.K. there is no exclusivity to who

can join. In a 2009

New York

magazine profile of Santos

Party House, Andrew W.K. revealed he’d much rather be

the party’s organizer than the reveler: part of the group

as opposed to the literal life of the party. And while

party may be an all-purpose, universal word applied to

whatever topic Andrew W.K. happens to be talking about

in and outside of the music, “we” is not. “We,” even in all

its inclusive openness, is specific.

“We” are those that find our place with the daring,

non-timid souls who only know victory.

•

14

•

1

Perilymph

The inner ear … consists of the bony (osseous) labyrinth, a

series of interlinked cavities in the petrous temporal bone, and

the membranous labyrinth of interconnected membranous

sacs and ducts that lie within the bony labyrinth. The gap

between the internal wall of the bony labyrinth and the

external surface of the membranous labyrinth is filled with

perilymph, a clear fluid with an ionic composition similar to

that of other extracellular fluids …

—Gray’s Anatomy, on the inner ear

Jesus’ return is supposed to be heralded with the sound

you’ve never heard that you can’t describe that is the

sound that changes everything. This sounded like the

end of the world.

—Andrew Wilkes-Krier, on a noise he made

When Andrew was four years old, Jim took piano lessons

from an acquaintance at the University of Michigan law

school. Andrew had already shown interest in the brown

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

15

•

upright sitting in the family living room, pulling himself

up to a standing position before he was able to walk and

blindly poking any white key he could reach. Jim’s teacher

began staying an extra 15 minutes after each lesson,

playing along with Andrew to make musical impressions

upon him rather than bestow any technical instruction.

That same year, the University of Michigan’s music

school started a program to match community youths

with Master’s-seeking students who needed teacher

training. Andrew’s parents wanted to enroll him when

he was six, but first he’d have to try out in one of those

closed-room, no-moms, we’ll-call-and-let-you-know

auditions against older children, some of whom could

read both music and words.

“The director called me back and said, ‘What we

were so impressed with is that he made up music,’”

Wendy says. “He didn’t play ‘Mary Had a Little Lamb’

or ‘Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star’—he’d just start making

music. We’d say ‘Where did you learn that?’ and he’d go,

‘I made it up. I have another one!’”

The director told Wendy that Andrew, with

his advanced ear, might find learning to read music

frustrating. Eventually, years of regular classes and

hourly flashcard practices and pressure-packed classical

recitals did catch up, all but burning Andrew out by the

time he was in junior high. The director decided to take

Andrew on personally rather than have him quit the

program. At the time, she was preparing to play piano for

a production of Jesus Christ Superstar, and the sounds of

Andrew Lloyd Webber found their way into her lessons.

“This huge music pounding him—it was like the light

bulbs went on,” Wendy says. “We also had this recording

I G E T W E T

•

16

•

of Hooked on Classics. It’s just this up-tempo classical music,

and he would play it so loud, then run around the house to

these huge sounds. That took him over the hump.”

Hooked on Classics also took Andrew into a realm of

physical happiness beyond being happy and his brain

feeling good. “It’s where it sends to every version of

your senses,” he says, “and then even beyond into your

soul and then into the world around you. When you’re

in that state, everything looks cool, everything seems

more interesting, and you’re more enchanted by your

surroundings, like the world has improved.”

***

Andrew’s childhood home in Ann Arbor is a center

hall colonial built in the late 1920s, with wood floors

that creak with every tiptoe, never mind resonate with

every disco-pop interpretation of Bach concertos or the

reactionary freak-out. (The owners prior to Andrew’s

family actually brought in a local band called The Iguanas

to play their daughter’s sweet 16th birthday party—and

one can only imagine the raw power a full band had

on those floor panels.) The black Yamaha piano that

replaced the brown upright when Andrew was five sits

in the corner of the open, bookshelf-lined living room

on the first floor, where it projected rehearsed scales,

on-demand Christmas carols, and inspired improvisa-

tions for all to hear from basement to attic. Andrew’s

younger brother Patrick says 55 Cadillac, Andrew’s 2009

album of piano improvisations, “reminds me of home,

because it’s just Andrew on the piano doing whatever—

it’s exactly what the house used to sound like.”

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

17

•

The basement ultimately became the noise-emitting

epicenter in Andrew’s musical world, but first it was a

playground for Patrick and his friends … and laboratory

for young Andrew’s creativity. “Andrew’s birthday parties

were pretty normal,” Wendy says, “but Patrick’s birthday

parties were not normal because Andrew ran them.”

Patrick remembers him and his friends embracing their

guinea-pig roles, crawling through winding, interlocking

cardboard-box tunnels, each box with a different gory

mask or frighteningly lit horror scene that was “very

realistic and scary and intense for a little kid,” Patrick

says, “but a lot of fun.”

***

Ann Arbor’s musical history doesn’t begin and end with

The Stooges’ debut album—after all, the MC5 released

their debut album first, and the Michigan student who

wrote that first Paul Is Dead article did so just after The

Stooges came out in 1969—but to many, Iggy Pop and

his band are the rock gods by which all others shall be

compared. Andrew W.K. doesn’t know a single song.

“I still don’t,” he says. “I’m not proud of that and

it’s not meant personally, but in Ann Arbor and in

Michigan in general, groups and acts from that region—

especially legendary ones—they took up a lot of space.”

So much space, in fact, that Andrew’s own living room

isn’t immune to the saga. Before Iggy was Iggy, he was

James Osterberg, playing sweet 16 house parties with the

band from which his nickname derives.

***

I G E T W E T

•

18

•

“We’d say ‘Oh, the Stooges suck,’ just to be assholes,”

says Jim Magas, who, alongside Pete Larson, co-founded

the band Couch.

Examine any scene and you’re bound to find a backlash.

Wait for the ebb to flow and you’ll witness a revival that

counter-attacks that backlash. Zoom in closer and you’ll

notice crossed arms awaiting the revival, perhaps with some

of those original scenesters split between the camps. Get

distracted by some all-encompassing, planet-misaligning

sound from the side and that’s where you’d find Magas,

Larson, and—from all accounts—the tens of kids that kept

Ann Arbor neighborhoods noisy in the 1990s.

“We never thought the Stooges sucked by any stretch

of the imagination,” Magas clarifies. “It was really just a

sense of making fun of everything and totally lampooning

everybody, from the promising bands in Ann Arbor to

the sacred cows.”

Magas describes Couch as a “strange, kind of weirdo

rock band.” Bent on outbursts of abstract intensity

more than they were hooks, choruses, or any of the

other stereotypical song-trappings, Couch found both

friends and enemies in nearby Chicago’s no-wave

scene. Quintron, a musician who ran (and lived in)

a ramshackle Chicago theater, remembers the band’s

first show there being so polarizing that a couple broke

up over “whether Couch sucked or not.” Chicago,

Quintron says, was “more driven by people in art

school, and I liked the Michigan noise scene better

because it was freer and funnier. Couch was hands-

down the king of that whole spirit.”

***

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

19

•

Back when he was a kitchen-spinning toddler in California,

Andrew’s family lived next to a couple and their two

college-aged sons. The two young men took a shine to

their little neighbor, and especially got a kick out of calling

him Andy. “It was like calling him ‘Sue,’” his mother says.

“He didn’t know that’s a nickname for his name. He would

just ignore them and they were dumbfounded.” And, like

that, a more subtle Wendy mission had succeeded: “I hate

that name,” she says of Andy, “and I figured if Andrew

introduced himself as Andrew, then he’s not even going to

respond if you don’t call him by his name.” Early on in his

elementary school career, he and a child named Andrew

Cohen were in the same class, and neither were blinking

in the settle-on-Andy stare-down. The teacher ultimately

dubbed them Andrew W-K and Andrew C. (Later in life,

when Andrew C. began his musical career, he would call

himself Mayer Hawthorne.)

In second grade, Andrew approached a child in his

class named Toby Summerfield. “I’m weird,” Andrew

declared. “Are you weird?”

“I can’t be sure, but I bet I brought my guitar

over to his house the first time I came over to play,”

Summerfield says of their friendship which grew around

musical discovery. “All 13-year-old boys in Ann Arbor

were issued the first Mr. Bungle record. We went to

Schoolkids’ Records, and asked for ‘more like this.’”

Andrew and Summerfield were shown John Zorn’s

production credit on Mr. Bungle and directed to his Naked

City work, from which Summerfield says Andrew’s path

veered toward Zorn’s harsher, more aggressive metal,

while his followed other Naked City members. Along his

way, Andrew was introduced to a Couch 7-inch.

I G E T W E T

•

20

•

***

Each semester, Larson would apply for an emergency

loan from the university, pleading he couldn’t pay a bill

or whatever other outrageous claim they’d buy. In 1993,

he used a loan to co-create Bulb Records with Magas.

Their first release, Couch’s four-song 7-inch, shows both

members bespectacled and suited-up: Larson leaning

back with a cigarette and Magas with his chin buried

in his schoolboy knot. Magas says it was catalogued as

BLB-026 because the rookie label-heads didn’t “want it

to look like we didn’t know what we were doing,” and

because he was 26 at the time.

Aaron Dilloway, who would drum for Couch years

later, remembers seeing the band live with his friends

Nate Young and Twig Harper in the 11th grade. “Couch

was just another step further into chaos and strangeness

and we’d never seen anything like it,” he says. “I was

thinking it was free-form, then I got the 7-inch at

Schoolkids’ and was like, holy shit, this is the exact same

thing—this is actually structured chaos.”

***

Andrew saw Larson and Magas around town, but was too

starstruck to talk to them. Larson worked at an upscale

grocer—“it was like going to the store and having Frank

Sinatra at the cash register,” Andrew recalls—and one

day Andrew built up the courage to direct his dad’s cart

down Larson’s lane. “His dad wanted to get a case price

for wine,” Larson says. “They were the same brand, but

the wine varieties were different. I told him he couldn’t

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

21

•

do it and he got completely enraged.” Andrew says there

were “swears toward the end” and he left absolutely

devastated.

Magas worked at Schoolkids’, lining up in-store

shows and indulging his own interest in Japanese noise

(and bulk-purchase prices) by recommending albums

to neighborhood kids who adored him. “There’s one

Masonna CD,” Magas says, “and I don’t know how they

did it, but it was ten times louder than any CD you’d ever

heard. It had this weird mastering thing, and I remember

that having an impact on Andrew.”

Once, Andrew handed Magas a tape of what he’d been

working on, and Magas said it didn’t have that “Earth-

destroying whoosh.” Andrew, again, was devastated.

However, Magas would introduce Andrew to Dilloway,

whom Magas considered a ringleader with a lot of

the kids getting into noise. Andrew knew of Dilloway

through his band Galen, and, even though Dilloway was

only a few years older, Andrew idolized him too. “He

was aware of some of my recordings I was bothering Jim

with,” Andrew says, “but Aaron had the warmth and the

courage—the boldness, the not-shyness—to invite me

to come over to his house that day. This was like getting

to go to an icon’s house. Like, wow, dreams could come

true.”

***

For a while Dilloway lived at the Huron House, one

of a few Ann Arbor residences that could colloquially

be called the punk-rock house. Fred Thomas lived in

a closet there. Steve Kenney lived in a closet across the

I G E T W E T

•

22

•

room from Thomas’, and remembers a time when two

people—who were not a couple—shared that closet.

Across town, near the university’s Institute for

Social Research, was another punk-rock house called

the Jefferson House. Thirteen-year-old Andrew was

terrified of the place because of “the threat of something

disgusting or awful happening,” but says he was simul-

taneously drawn to it because of those very dangers.

Eventually, he was struck by the residents’ commitment

to that life and to music. He told the

Ann Arbor Observer

in 2003 that they “lived the way they wanted to live, and

it was so on their own terms and so free that anything

seemed possible.”

Allow one-time resident Twig Harper to give the

grand tour: “There were homeless people living on the

porch … we painted the kitchen completely head-to-toe

blue … we had a rotting deer carcass someone found in

the dumpster, like, hanging off the front tree. … It was

one of those situations where someone comes over and

they give you a lot of LSD and you’re convinced possibly

that they could be an agent and the whole house you live

in is some sort of social control experiment.”

***

Andrew and Fred Thomas saw each other at Huron

House shows and around town, but the elder Thomas

says he didn’t really get to know the high-schooler

until they worked together at a costume shop in nearby

Ypsilanti.

“I’m going to go down to the store,” Andrew said one

day. “Do you want anything?”

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

23

•

Thomas, being a self-admitted young, broke punk kid

living in a closet, took out all his cash.

“I’m starving,” Thomas said. “Get me as much food as

you can with this dollar.”

Envisioning a candy bar or soft drink or some standard

convenience-store fare, Thomas was not expecting an

explanation, which was the first thing Andrew offered

upon his return.

“OK, I will take this back if you get mad,” Andrew

said, “I did exactly what you told me to do.”

And with that, Andrew presented a three-pound bag

of oyster crackers, “technically and literally the most

food he could have bought me for a dollar,” Thomas

says. He was taken by Andrew’s thought process that

was “equal parts sublime and ridiculous,” and that, more

impressively, he had food for the next week.

Andrew and Thomas became obsessed with extremity,

from the outrageous Japanese fashion magazines they’d

pore over to the breakneck black metal that they listened

to so loudly and so frequently that it seemed to slow

down. At some point, the two devised a plan where

Andrew would tell his parents that Thomas was a foreign

exchange student—“France or Norway or something,”

Thomas says—so he could live in the upstairs attic.

Instead, Andrew simply asked his parents if his friend

from work could move in. Thomas wouldn’t find out he

could drop the routine for a few uncomfortably silent days.

***

Thomas’ Westside Audio Laboratories label released

a cassette in 1996 entitled Plant the Flower Seeds,

I G E T W E T

•

24

•

a compilation capturing local musicians when they

were 13 or younger and their prolific fires were

just sparking. A squeaky-voiced Andrew Wilkes-Krier

introduces his entry, “Mr. Surprise,” as the theme

song to the reappearing titular character, before what

sounds like a carnival calliope run on cotton candy

kicks in and the whimsical tale of an ever-mutating

creature is told.

The song had originally appeared on a tape Andrew

made called Mechanical Eyes, complete with color-pencil

drawings he had color-copied at Kinko’s. He made about

ten tapes, selling a few and passing the rest around to

friends.

Andrew has said this tape is his first released-

for-public-consumption effort. To trace every tape

(commercial or otherwise) and name-drop each of

Andrew’s bands since isn’t so much daunting as it is

impossible. Bands in Ann Arbor could be as short-lived

as they were incestuous, configured quickly for kicks or

conjured hypothetically, also for kicks. “Everybody was

doing things with their friends at all times,” Thomas

says. “Highly collaborative. There could be six people

and that could be, at any given time, 12 different bands.”

It’s a recipe for documentarian disaster, and an errand

this fool believes takes away from the spirit fueling the

effort. Rather than attempt a doomed-to-fail compre-

hensive listing, I present these early, mostly Michigan,

pre-

I Get Wet

efforts for what it is: not definitive, not

chronological, not entirely fleshed-out, and compiled

strictly for narrative’s-sake.

***

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

25

•

In either late elementary school or early junior high,

Andrew and Summerfield were in a two-person band

called Slam. (Summerfield claims the proper name was

“Slam: A Two-Person Band.”) They drew up cassette

tape labels and had a song called “Ode to Bolga,”

where the two sang the lyrics, “Ode to Bolga / death

to Bolga.” That band evolved into Reverse Polarity,

which Summerfield says leaned grunge. Reverse Polarity

became Sam the Butcher, and at some point between

the two incarnations—where lineup changes and experi-

mentation had Andrew on bass, on drums, and at the

mic at various times—they played the local Unitarian

church, a venue where Andrew would see some of the

bands that influenced him most, from local favorite

Jaks to Dilloway’s band Galen to Twig Harper’s band

Scheme. The church was in a residential neighborhood

right around the corner from where little brother Patrick

had gone to nursery school, so Andrew’s mother had no

problem with Andrew going to shows there despite, as

Andrew says, “the whole right side of the venue (being)

sliding glass doors, and at almost every show, one of them

was broken if not someone flying all the way through it.”

***

Andrew would watch a grindcore band named Nema

rehearse in Huron House’s basement. “Andrew was a

really good drummer, and was one of the only people we

knew who could really play black metal with any kind of

authority,” says Nema vocalist Jeff Rice, who would join

Andrew’s band Kathode. “Once people in Nema heard

him play, everybody wanted to start a band with him.”

I G E T W E T

•

26

•

Kathode was all about “playing as fast as possible and

growling as most inhumanly possible,” Rice says. When

time came to record a demo, they all of a sudden had to

come up with words, so he and Andrew split the task,

with Rice’s leaning left-wing radical and Andrew’s lyrics

being “your standard non-conformist theme,” according

to Rice.

Rice remembers Andrew and a friend executing what

he calls an “art annoyance project”; Andrew says he was

simply trying to make something intense happen that

normally didn’t.

Andrew and the friend propped a huge PA speaker

in the ground-level window of that friend’s downtown

apartment, plugged it into a keyboard, taped all the

keys down, cranked every available knob, laced up their

running shoes, and went for a jog. “This was so much

louder than we thought it would ever be,” Andrew says.

“Like, Jesus’ return is supposed to be heralded with the

sound you’ve never heard that you can’t describe, that is

the sound that changes everything. This sounded like the

end of the world.”

When Andrew and his jogging partner returned,

they found a mass of people banging on the front door.

“We were like, ‘Oh my god, what’s going on in there?’”

Andrew remembers. “‘Did you leave the blender on?

Maybe the radiator’s gone haywire?’”

***

Andrew’s super-progressive Community High School

offered a class where a local expert would come in and

voluntarily teach a course. One year, Andrew enrolled in

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

27

•

an Asian cinema course being taught by Pete Larson. (“I

showed Drunken Master 2, but at that time not a whole

lot of people knew who Jackie Chan was,” Larson says.

“All of the 2s are amazing. Swordsman 2, God of Gamblers

2 … .”) Larson was also playing guitar in a Judas Priest-

channeling band called the Pterodactyls. Dilloway,

as Pterodactyl Man, dressed up as he envisioned a

Pterodactyl Man would and blabbed improvised lyrics at

live shows. Steve Kenney was the Pterodactyls’ original

drummer, but Larson eventually got Andrew to replace

him. Promoted on Bulb’s site as being from Germany,

the Pterodactyls’ 1996 release,

Reborn

, shows Andrew in

a studded leather jacket, credited as L.A. Ellington for

drums and “look.” The front-cover banner has the band’s

name as the Pterodactys, without the “L” — an ode to

when Kenney forgot to include the letter on a demo-tape

spelling. The band was set to go on a tour that spring

break, but Andrew was grounded for not waking up in

time for class; Kenney was invited back.

Larson, Dilloway, Kenney, and Andrew are all

credited—Andrew, by his full name—on a Mr. Velocity

Hopkins album released in 1999. “I don’t think I’m

actually on that, but I’m listed as being on it,” says Steve

Kenney, whose first and last name is spelled incorrectly

on the liner notes.

***

Andrew was creating T-shirts for his band Lobotomy,

but he misspelled it Labotomy. Lab Lobotomy was born.

On bass was Allan Hazlett, who remembers first

getting acquainted with Andrew because “there was

I G E T W E T

•

28

•

an Arby’s really close to his house, and since he knew

that I went to Arby’s a lot, it became convenient for me

to give him a ride home.” Hazlett remembers sipping

on a vanilla milkshake the first time he heard Andrew

play piano. It was “Hey Jude.” Andrew was singing, and

Hazlett thought he sounded better than Paul.

Playing guitar was Jaime Morales (who Andrew

credits with introducing him to that Couch 7-inch) and

Alex Goldman. Hazlett says they’d plan out a few licks,

but the different influences each member brought to

the table resulted in constant direction-shifts. “Almost

ambient and slow, plodding along,” he says, “then frantic,

and then white noise, etc.” At one afternoon outdoor

show, Hazlett hoisted an aged vacuum cleaner up to the

mic and it “chocked and died and belched out all this old

dust.”

Sometimes, when Goldman wasn’t there, the others

would go hillbilly and become The Rusty Bucket Group,

a super-distorted bluegrass group. “It was high-pitched

screaming,” Goldman says of their tape he’s since lost,

“and they’d be grumbling and hacking in-between

songs.”

“Andrew, more than anybody, really reveled in that

kind of thing,” Goldman says.

***

The Portly Boys was Andrew and a group of overweight

inner-city youths who sang fun chants to demonstrate

their take-no-shit bond.

“Portly Boys Bounce / BOUNCE BOUNCE

BOUNCE BOUNCE

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

29

•

Portly P- Portly / BOUNCE BOUNCE BOUNCE

The Port! Ly! Boys! / WHAT?!

The Port! Ly! Boys! / PICK IT UP!”

The Portly Boys were on an Ann Arbor label called

Rockside BK, alongside bands like Hot Milk, Bedazzler,

Hype Obesity, and Stormy Rodent and the Malt Lickers.

Only one Portly Boys tape was ever sold.

“My friend Jamie has the only copy,” Rice says. “He

had no idea it wasn’t a real band when he bought it.”

Rice says Kathode practices would usually devolve

into everyone inventing ideas for bands—“probably the

best thing about Kathode.” The thing that separates

teenage Andrew from the millions of other kids playing

this parlor game is, as Rice says, “where most people stop

it at the bullshitting phase, Andrew would actually do it.”

“Andrew came up with a fake tape label called Rockside

BK.” Rice says. “He made a catalog of all these bands that

didn’t exist, wrote descriptions of all of them, and made

them as outlandish as possible, and, if somebody actually

bought a tape, he would write and record the entire

album himself, posing as a band. It was a made-to-order

record label.”

Haunted Elegance, the only other Rockside BK tape

Andrew says he made, had a “vacuum-cleaner guitar

tone … these really thin drums, and then a sort of Louis

Armstrong vocal.”

***

When Andrew was 12, he successfully sold a forgery

of a collector’s item—an item that, in 2008, sold for

$2.8 million.

I G E T W E T

•

30

•

Andrew’s childhood home showcases his art on

many surfaces, from a pencil-sketching of his father to

an abstract S&M painting above an upstairs toilet, to

framed school assignments on the walls, including one

of a road-raging, three-headed wolf meant to reference

the hot-rod style of artist Coop. (Andrew signed his

“Poop.”) Andrew created and sold X-rated cards to a

comic store in town that, according to his mother, wasn’t

allowed to sell the cards back to the underage Andrew.

Long before he met Andrew, Goldman bought a bizarre

comic from that store which he envisioned some weird

50-year-old guy in town creating. Later, when Goldman

brought up the odd find and shared that impression,

Andrew told him, “Thanks—that’s what I was going

for.” Patrick’s favorite items were the collector cards

showcasing graphic torture scenes, such as a man’s face

with a hook and chain pulling at his eyeballs. “They were

cartoony,” the brother says, “so it was kinda funny at the

same time as being disgusting.”

One day, Andrew began working on creating baseball

cards. Patrick vividly recalls the meticulous processes

of Andrew removing perforation nubs, applying dirt,

burning it to make it appear weathered, then the

scratching off of some of the surface. When Andrew

wanted to sell the lot—a collection that included the

1909 T206 Honus Wagner baseball card, considered

the holiest of holy cardboard grails—he had an older-

looking friend take them to an Ann Arbor antique store.

They got $250.

No one is entirely sure how the owner got wise—or

why he’d pay anything if he knew all along they were

fake, which he claimed—but Andrew says he did confess

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

31

•

after the owner mentioned a friend in the FBI. As

punishment, Andrew says the owner demanded he give

his son art lessons.

Prompted by this and/or a separate incident where

Andrew created and distributed fake cease-and-desist

letters, he started seeing a child psychologist. “Why are

you here?” led to the immediate follow-up “And why

do you think your parents want you to come?” which

led to “And why did you get in trouble” and onto “And

why did you think it would be exciting?” and so on, for

months. Finally, the trained professional sat Andrew

and his parents down to discuss his ultimate conclusion:

“Andrew has a devilish side.”

“My Dad and I—but my Dad especially—thought it

was just hilarious and ridiculous,” Andrew says. “It was

such a strange, underwhelming conclusion. Almost like,

‘We knew that coming in—that why he’s here!’ But I

guess he was trying to say it more like, ‘You have to find

a better outlet for these impulses.’”

***

Ancient Art of Boar (aka AAB) began with Andrew

and his Lab Lobotomy-bandmate Jaime Morales, then

became Andrew’s solo project, which he soon invited

Dilloway to play in. Dilloway says years later when he

was focused on fashion, Andrew started an Ancient Art of

Boar clothing line, creating a dress that was “completely

black shreds, like super avant-garde.”

In the summer of 1996, Andrew wrote and recorded

an AAB album for Thomas’ Westside Audio Laboratories.

“You can see the seeds for what came afterwards,”

I G E T W E T

•

32

•

Thomas says of Bright Dole. “It’s melodic, but there’s

just something under the surface that’s already undoing

everything that’s been done by the rest of the music. …

We always had this thing where we really didn’t know

what goth music was, but we imagined what it was. This

pale, wailing voice, which didn’t have anything to do with

anything.”

Westside also released, among other tapes featuring

AAB, a 7-inch specifically for a September 1997 show.

The idea was that each band playing would be repre-

sented with a song. Ancient Art of Boar—that is,

Andrew—backed out of the performance, but not before

the 7-inch was pressed. The song isn’t labeled on the

sleeve, but if you drop the needle, you’ll hear the Ancient

Art of Boar cover of Coolio’s “Gangsta’s Paradise.”

Andrew and Thomas formed a gothic rap group called

Coffinz, featuring Andrew’s beats under Thomas’ rhymes

about John Coltrane and eating power bars. After I Get

Wet came out, Thomas was instructed to never play

Coffinz for anyone.

***

In 1996, Masonna—the legendary, prolific Japanese

musician who astounded both Magas and Andrew with

his louder-than-possible mastering a few years earlier—

recorded

Hyper Chaotic

, the first release for an upstart

label called V. Records. The label was initially going to be

called Voktagon, but Andrew, the label’s creator, thought

that was too much.

“I just wanted it to be a really anonymous and kind

of boring label name,” he says. “Of course, there was

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

33

•

another V that I found out about. I think I was in a

depression for several weeks when I found out about

that.”

At the same time Andrew was mailing Kathode demos

to potential Japanese labels, he was contacting Japanese

musicians for his own label, communicating through

an upstairs fax machine that, according to his mother,

would “start spitting things out at like 4 in the morning,

night after night.” After

Hyper Chaotic

, the label released

7-inches by the Japanese death metal band Hellchild

and by Aube, a Japanese musician much more restrained

and minimalist-leaning than Masonna. His Fast Tumbling

Blaze 7-inch was recorded with only a single voltage-

controlled oscillator and was going to be the first of two

Aube releases on V. Records. He recorded the music

for the follow-up as well as created all of the album’s

artwork, which he carefully sent to Ann Arbor.

“It wasn’t a disc or a file,” Andrew says. “It was actual

artwork and photographs laid out by hand. He sent it

full-size in this huge tube. Everything was hand-pasted,

every word was cut out by hand, but it didn’t look like a

collage; it was a masterpiece of graphic art. And this was

a moment where I intentionally chose to do the wrong

thing.”

The wrong thing was Andrew trashing Aube’s artwork.

The urge was no different from the same urges he had

in committing other crimes, and the intent, he says, was

entirely to be mean. “I was 16 at the time, so I don’t know

if he was aware of that or if he had any idea of who I was.”

In 2000, Aube released

Sensorial Inducement

on Alien8

Recordings. Tracks on the LP were, according to the

first line of the album’s notes, composed and recorded on

I G E T W E T

•

34

•

May 2, 1996. Aube could not be reached for comment, so

there’s no telling whether

Sensorial Inducement

was to be

the potential fourth and final release on V. Records.

Nothing, except that on the second line of the

album’s notes, it reads “Fuck & No Thanks to Andrew

Wilkes-Krier.”

***

As was standard operating procedure for so many tape

labels of the era, releases were often dubbed over officially

released or promotional cassettes from major labels.

When Dilloway began Hanson Records, he got much

of his stock from the record store where he worked.

“Usually they’d send us a box of 25 tapes of some new

artist,” he says, “but one time, for some reason, they sent

us 300 copies of these blue-shelled, ten-minute cassettes

by this band Skold, some mediocre industrial rock. We

ended up doing a cassette single series.”

Some of those blue Neverland / Chaos promo tapes

ended up being repurposed, Dilloway says, as the first

release credited solely to Andrew Wilkes-Krier: Room to

Breathe. “That was just one thing I made one afternoon

and gave to Aaron,” Andrew says. “It wasn’t put together

or planned out as some big release; I think he only made

five copies of it.” Another recording, entitled You Are

What You Eat, has a diner-style ice-cream sundae on the

cover and was limited to two copies.

Andrew has appeared on Hanson tracks by The Beast

People (with Dilloway, Harper, Nate Young, and, at

times, Kenney), Isis & Werewolves (with Dilloway and

Kenney), The Hercules (with Dilloway and Anthony

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

35

•

Miller aka Dirty Tony), Galen via Hercules (a band with

Dilloway, Dirty Tony, and Kenney that either descended

from or gave birth to The Hercules), as well as the

1998 Hanson vinyl compilation

Labyrinths & Jokes

that

features songs by, among others, Isis & Werewolves,

The Beast People, and Andrew Wilkes-Krier. Etched

onto Side 2 of

Labyrinths & Jokes

’ run-out groove is the

phrase “So I Met this Like Totally New Kind of Kid,”

which Dilloway acknowledges is a sentiment about the

kid Magas introduced him to years earlier. Andrew didn’t

know about the etching on the vinyl; he really didn’t like

the name on the sticker.

“I told Aaron that if anyone ever asks, I’m one of the

labyrinths, not one of the jokes,” Andrew says. “I hated

the idea of someone thinking, ‘Oh, Andrew’s tracks

on this compilation are a joke.’ I wanted mine to be a

labyrinth.”

The Beast People, to highlight one band, balanced

guttural animal growls, screams, and whimpers on top of

a building keyboard line. “They did this one show at a

gnarly bar in Detroit where Andrew was The Phantom,”

says Galen guitarist Justin Allen. “He had these leather

pants, big frilly shirt, the mask, and a really long wig. He’s

on stage playing The Phantom of the Opera soundtrack,

and then all of a sudden this pantomime horse comes

walking through the audience, bumping into people.

The horse then birthed The Beast People. I call it stupid

because that’s how you would probably classify it as far

as the realms of humor are concerned, but I think it’s

amazing.”

***

I G E T W E T

•

36

•

“This was a game I used to do as a kid,” says Dilloway,

describing a scene from a movie he and Andrew co-wrote

where the main character darts down a hill, prompting

a congregation of cows to give chase. “It was such a

magical thing that it happened while we were filming.

Did you notice the lone horse?!”

Poltergeist stars Andrew, the farm owned by Dilloway’s

grandparents, and—yes, for a brief moment—a horse

that thinks it’s a dashing cow. Andrew also created the

soundtrack, a portion of which is his entry on the Labyrinths

& Jokes compilation. One vignette has Andrew slo-mo

leaping around what looks like pink-and-black-striped

pipes and panels (which Dilloway calls the Jumble Gym).

Andrew spent weeks creating the piece, getting paint all

over his father’s garage floor and eventually erecting it

in his backyard for passers-by to see. (Pictures of it—and

Andrew posing in front of it, looking like a Ramone—

appear in issues of a magazine Andrew later created and in

the booklet for his 2010

Mother of Mankind

album.)

Andrew’s parents—convinced their music-playing,

movie-making, comic-drawing, fashion-designing,

sculpture-creating, project-oriented teen might become

an artist—gave him the ultimatum that he had to at least

apply to art school. Andrew took the ACT on two hours

of sleep, presented his portfolio on Immediate Decision

day at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and

got accepted. Andrew’s pencil-sketch of his father was

drawn just before Andrew told him he’d rather move to

New York City instead.

“Everyone tells me, ‘Oh, you’re so brave that you

could let your son not go to college,’” Jim says. “Look, I

teach in college—it’s no big deal, believe me.”

•

37

•

2

Juice

You know, I just can’t believe things have gotten so

bad in this city that there’s no way back. I mean,

sure, it’s dirty, it’s crowded, it’s polluted, it’s noisy,

and there’s people all around who’d just as soon step

on your face as look at you. But come on! There’ve

got to be a few sparks of sweet humanity left in this

burned-out burg. We just have to figure out a way to

mobilize it.

—Ray Stantz, in

Ghostbusters 2

, right before our heroes

discover the New York City icon known less commonly

as “Liberty Enlightening the World” as that symbol

that, along with an uplifting soundtrack, could appeal to

the best in all of us.

I love New York City / Oh yeah, New York City

—Andrew W.K.,

“I Love NYC”

“Look what I did,” said an excited Andrew in Mark

Morgan’s Brooklyn living room.

I G E T W E T

•

38

•

Morgan, missing the forest for the suddenly displaced

trees, sees only rearranged furniture, the relocation of the

TV, sprawled-out newspapers on the ground, massive new

paintings hanging on the walls, and his (detuned) guitar

not in its rightful place. And, of course, the unsightly cot

that Andrew has been calling a bed for the last few months.

“What the fuck, man?” Morgan says. That may be the

question he asks, but the overwhelming question in his

mind is actually one of semantics: is Andrew the worst

roommate or the worst houseguest in the entire city?

“He was more like an extended period guest than a

roommate,” Morgan says. “He would attain roommate

status in your mind, but then he’d do something to piss

you off and he’d be back to extended guest. He drove me

fucking crazy.”

A Michigan native himself, Morgan and his

female roommate in that $750/month, two-bedroom

Williamsburg apartment were doing Andrew a favor as

he got settled in the city. Before Morgan’s, Andrew had

stayed at his sister’s friend’s place while the friend was

away, but Andrew opened a window to combat the heat

and the friend’s cat jumped out and ran away. He only

planned on crashing at Morgan’s for a weekend, but that

turned into one week (Andrew rearranges CD and book

collections), which snowballed into one month (Andrew

mistakes savory gourmet cheeses for rotten food and

trashes it), which avalanched into three months (Andrew

insists on occupying the computer in Morgan’s room

after he has told Andrew to get the fuck out so he can

sleep) and into four months (neighbors complain about

Andrew’s noise). This was all before Morgan learned that

his apartment had burned to the ground.

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

39

•

“I was working and I got this phone call,” Morgan

remembers. “There were all these sirens and people

yelling in the background. They were like, ‘Hello, is

this Mr. Morgan? We’re sorry to inform you, but your

building caught on fire and I’m afraid you lost everything.

There might be a few things here for you to salvage—you

should come here and take a look.’ I was like, ‘Holy shit!

I’ll be there in 20 minutes.’ Then, all of a sudden, the

sirens stopped and Andrew’s like, ‘Hey man.’ He probably

spent hours making this ludicrous background tape for a

two-minute prank call. I was like, ‘You’re a fucking piece

of shit—fuck you,’ and hung up the phone.”

Morgan says the day he was about to kick Andrew

out once and for all, Andrew informed him he had found

another place to live.

“We got along a lot better when he moved out,”

Morgan says. “I was seriously ready to kill him. I was

like, ‘You can’t be doing shit in the living room without

fucking telling me.’ He was like, ‘Well, I can move it back

if you want,’ and I was like, ‘Don’t do anything, it’s fine.’”

“I had to admit—it actually did look better.”

***

Morgan got Andrew a job at Mondo Kim’s, the home

entertainment mecca on Manhattan’s St. Mark’s Place.

“I remember him listening to Billy Joel really loudly,”

Morgan says. “I fucking hate Billy Joel—I can’t stand that

shit. It’s got pianos, so I guess maybe that’s why. I just

remember it providing much mirth in the store.”

Also working in the second-floor vinyl section was

Matt Quigley, whose band—an art-pop duo named

I G E T W E T

•

40

•

Vaganza—was about to release its debut album on a Geffen

subsidiary. (Prior to Vaganza, the New Jersey native had

played with his teenage buddies in Skunk, which put out

two releases on Twin/Tone.) Quigley saw a quiet, funny,

slightly effeminate, artsy kid in Andrew. One day, Quigley

played a test pressing of Vaganza over Kim’s speakers.

The horn-heavy glam opener with its ELO melodies was

followed by the rich piano-centered orchestration and

delicate harmonies of what was to be the album’s single,

“Everyday.” He showed Andrew a picture of the duo in full

extravagant regalia, and Andrew asked if he’d ever heard of

Sparks. “That’s how I bonded with Quigley,” Andrew says.

“I feel like Vaganza predicted what Sparks ended up doing.”

“Every time I came home,” Morgan says, “[Andrew]

was listening to Sparks. When his first record came out,

people were like, ‘Oh, this fucking hair-metal shitbag.’ I

think people got caught up with the signifiers of people

with long hair rocking out with fucking guitars. It didn’t

really sound like ’80s cock-rock to me. It sounded like

Sparks. The hooks were similar.”

Fred Thomas remembers Andrew latching onto Sparks

when they lived together, with Andrew getting so worked up

by their flamboyance, theatrics, and lyrics that his unending

insistence that Thomas needs to really listen to it did

nothing more than try Thomas’ patience. When Andrew

moved to New York, he’d similarly inundate Thomas with

Napalm Death’s Harmony Corruption. “I’d say, ‘It’s good, but

it’s fucking crazy grind metal—what do you want me to say?

I love it, but I’m also over here listening to Yo La Tengo, so

maybe we can talk in the middle.’”

***

P H I L L I P C R A N D A L L

•

41

•

As he’d record, Andrew would bring songs to Morgan

and Quigley. More than 15 years later, Andrew still

remembers Quigley’s reaction the first time he played

something for the Kim’s collective: “This is the music

that an insane person makes.”

The lyric-less “Airplanes,” which eventually evolved

into

I Get Wet

’s “

Got to Do It”

(after, Andrew says,

dumping a distinct Cure, “Boys Don’t Cry” vibe), had

an upbeat, major-key melody with what Quigley says

were “cheesy, pre-set, digital synth sounds.” He knew it

wasn’t techno pop, it wasn’t retro, and it certainly had no

connection to any underground sound of the times.

“It was utterly inscrutable by being so completely

not,” Quigley says. “I knew Andrew well enough to know

that this wasn’t cynical. There was nothing contrived

about the degree to which he was trying to be icono-

clastic. I said, ‘This is music made in a vacuum—you

don’t know that this is fucking weird.’ He came upon

things in a very peculiar way; I don’t even think he knew

what rules there were to break.”

***

Some of the late night work Andrew did on Morgan’s

computer was for WOLF “Slicer” Magazine, a ’zine-like

publication Andrew created and was quick to correct

when someone—like Morgan—called it a ’zine. Issues

featured pictures of him and the Jumble Gym, fake