Il Trovatore Page 1

Il Trovatore

“The Troubadour”

Italian opera in four acts

Music by Giuseppe Verdi

Libretto by Salvatore Cammarano,

after El Trovador (1836), a tragedy by

the Spanish

playwright, Antonio García Gutiérrez

(The final libretto was completed by Emmanuele

Bardareafter Cammarano’s premature death.)

Premiere at the Teatro Apollo, Rome,

January 1853

Adapted from the

Opera Journeys Lecture Series

by

Burton D. Fisher

Story Synopsis

Page 2

Principal Characters in the Opera

Page 4

Story Narrative with Music Highlights Page4

Verdi and Il Trovatore

Page 17

the Opera Journeys Mini Guide Series

Published/Copywritten by Opera Journeys

www

.operajourneys.com

Il Trovatore Page 2

Story Synopsis

The Il Trovatore story takes place in

Spain during the early 15

th

century: a civil

war rages between the armies of the Duke

of Urgel, a pretender to the throne, and King

Juan I of Aragon: Manrico is allied with

Urgel, and the young Count di Luna with

the King; these two enemies in war are

also rivals for Leonora, a beautiful lady-in-

waiting to the Queen of Aragon.

Fifteen years before the opera story

begins, an old gypsy was accused of

bewitching the elder Count di Luna’s infant

son, and thus causing the child’s subsequent

deathly illness: afterwards, the gypsy was

burned at the stake. Her daughter, Azucena,

to avenge her mother’s execution, kidnapped

the di Luna infant, intending to cast him into

the fires. But in her deranged state of mind,

she accidentally cast her own son into the

fires. Azucena escaped with the di Luna child,

named him Manrico, and raised him as her

own son.

In Act I, “The Duel,” Manrico, a

troubadour, serenades Leonora from the

palace garden. His rival, Count di Luna,

confronts him. A duel ensues and Manrico

triumphs, but spares di Luna’s life.

In Act II, “The Gypsy Mother,” Manrico’s

surrogate mother, the gypsy Azucena,

relates the events of her mother’s horrible

execution by the elder di Luna. Manrico,

shocked at the cruelty, joins his mother and

vows revenge against the di Luna family.

Il Trovatore Page 3

Leonora believes that Manrico died in

battle and escapes to the convent of Castellor

to take her vows. Di Luna attempts to

kidnap Leonora, but retreats after Manrico

and Urgel’s soldiers overwhelm him.

In Act III, “The Gypsy Woman’s Son,”

di Luna prepares to attack the fortress of

Castellor to re-kidnap Leonora. Azucena is

captured by di Luna’s army. In panic, she

calls for Manrico’s help. Di Luna is delighted

that he has captured his enemy’s mother: he

vows double vengeance.

Inside Castellor, just as Manrico and

Leonora are about to be wed, Manrico learns

that di Luna captured Azucena and plans to

execute her at the stake. Manrico rushes

off to rescue his mother.

In Act IV, “The Torture,” Manrico and

Azucena have been captured and are

imprisoned awaiting execution. Leonora

offers to sacrifice herself to di Luna to save

Manrico: di Luna agrees, but Leonora

secretly takes poison.

Leonora arrives at the prison to tell

Manrico that he is free: di Luna sees Leonora

in Manrico’s arms, realizes he has been

betrayed, and orders the immediate execution

of Manrico and Azucena. Leonora dies from

the poison. After Manrico is executed,

Azucena reveals to di Luna that he has killed

his own brother: she shrieks with joy that at

last she has fulfilled her life’s obsession; her

mother has been avenged.

Il Trovatore Page 4

Principal Characters in the Opera

Leonora, a Lady-in-Waiting to the

Queen of Aragon

Soprano

Count di Luna, a noble

Baritone

Manrico, a soldier and troubadour Tenor

Azucena, a gypsy Mezzo Soprano

Ferrando, a captain of

di Luna’s guard

Bass

Inez, Leonora’s attendant

Soprano

Ruiz, Manrico’s lieutenant

Tenor

Soldiers of Urgel and Aragon, gypsies, nuns

of Castellor

TIME:

the year 1409

PLACE:

Spain, the provinces

of Biscay and Aragon

Story Narrative with Music Highlights

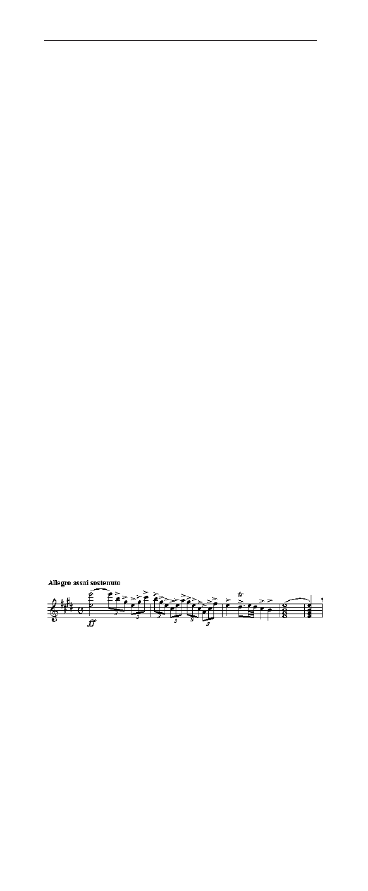

A twice repeated drum roll is followed by

a burst of trumpets, a chivalric yet ominous

introduction to the forthcoming tragedy.

Opening music:

ACT I: “ The Duel”

Scene 1 - Midnight at the Palace of Aliaferia

in Aragon, Spain

The Queen is in residence in the di Luna

palace of Aliaferia. The young Count di Luna

passes the night before the window of the

woman he passionately loves, the Queen’s

beautiful lady-in-waiting, Leonora. The Count

has become consumed with jealousy and has

Il Trovatore Page 5

ordered his soldiers to be on guard for a

mysterious, unknown rival who serenades

Leonora by night.

The soldiers huddle around a fire.

Ferrando, a captain in di Luna’s guard,

narrates the gruesome story that occurred

fifteen years ago when the Count’s baby

brother, Garzía, disappeared.

Garzía’s nurse awoke one morning to find a

sinister old gypsy hag in sorcerer’s robes

hovering over the baby’s cradle, her bloodshot

eyes staring fixedly on the child. The nurse

screamed, help arrived, and the gypsy was

seized, protesting that she had only come to tell

the baby’s fortune. The gypsy was released, but

afterwards, the child became deathly ill with a

lingering fever. All thought that he would die,

believing that his affliction was caused by an

“evil-eye” curse laid on the child by the old

gypsy. Di Luna’s soldiers pursued the gypsy in

the mountains of Biscay, apprehended her,

accused her of witchcraft, and then executed

her at the stake.

In terror, the old gypsy’s daughter vowed to

avenge her mother’s brutal death: she kidnapped

the di Luna infant, Garzía, from his cradle. After

his disappearance, a frantic search ensued, but

all that was found was a small half-charred

skeleton smoldering on the exact spot where

the old gypsy had been burned. The Count di

Luna was broken-hearted, but was never fully

convinced that his infant son was dead. Soon

thereafter, while the Count was on his deathbed,

he made his other son, the present Count di

Luna, swear that he would be unceasing in his

search for his brother.

The executed gypsy’s daughter vanished.

However, it is believed that she still lives in

Biscay and roves the countryside: Ferrando

is certain that he would immediately recognize

her savage face if he saw her again.

After hearing Ferrando’s tale about gypsy

sorceresses and the di Luna family misfortunes,

Il Trovatore Page 6

the soldiers shiver with superstitious dread.

The midnight bell sounds, and they all depart

and enter the palace for the night.

ACT I - Scene 2: A terrace of the palace.

Leonora, a lady-in-waiting to the Queen of

Aragon, strolls on the garden terrace with her

attendant and confidant, Inez, heedless to Inez’s

reminder that the Queen calls her from inside

the palace. Leonora has come to this secluded

corner of the palace garden hoping to meet her

secret lover, Manrico, the troubadour who has

been visiting the palace at night and serenades

her from the garden.

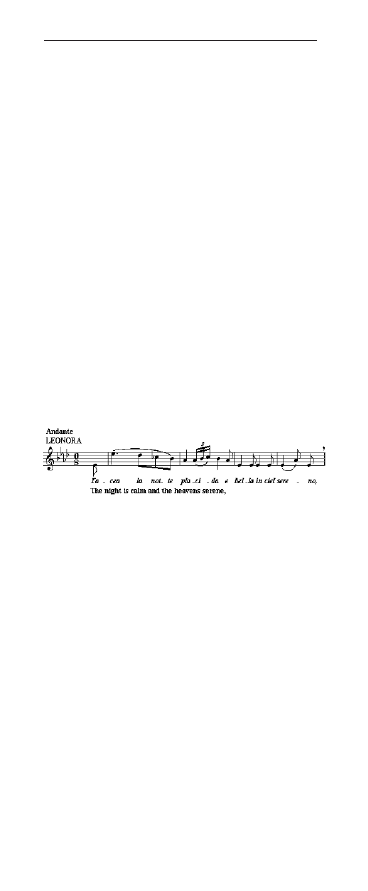

Leonora: Tacea la notte

Leonora confides to Inez that she met

Manrico when he was participating in a jousting

tournament. He was an unknown knight in black

who won every joust, and she had the honor to

bestow the victory crown upon him. After the

outbreak of the civil war, the mysterious knight

vanished.

But suddenly he has reappeared, serenading

her at night and invoking her name in beautiful

song. Inez tries to dissuade Leonora, fearing

that her lover is an enemy of Aragon in the

civil war; her passion for him can only lead

to sorrow and anguish. Nevertheless, Leonora

has become captivated and enraptured by the

mysterious knight: she affirms her intense love

for him and vows that she would gladly die for

him.

Il Trovatore Page 7

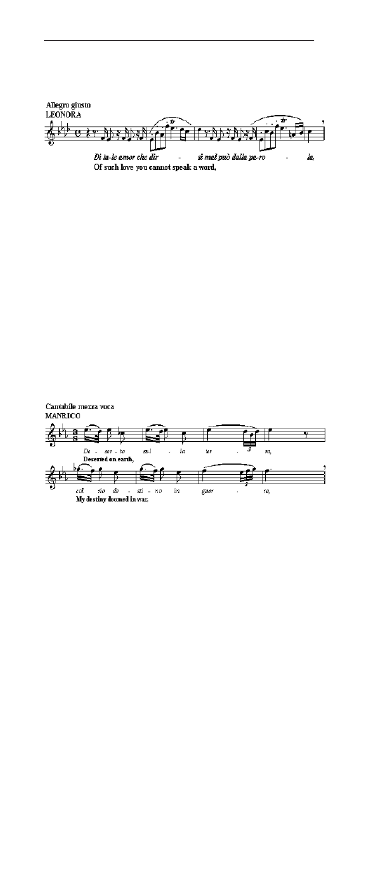

Leonora: Di tale amor che dirsi…

After Leonora and Inez enter the palace, the

Count di Luna appears in the shadows. As he

expresses his obsessive passion for Leonora,

he is suddenly interrupted by the sound of a lute:

his rival for Leonora has evaded his guards and

is presently in the palace garden.

The troubadour’s serenade laments his sad

destiny: he is lonely on earth, and is doomed to

fight in wars. .

Manrico’s Serenade: Deserto sulla terra…

When Leonora hears the troubadour’s

serenade, she rushes from the palace to greet

her lover, but in the darkness, she mistakenly

embraces the Count di Luna. The troubadour

then appears, raises his knight’s visor and reveals

his identity: “I am Manrico,” further announcing

that he is an officer in the Urgel’s army.

The Count erupts into a frenzy of jealousy

and anger, incriminating the troubadour as an

outlaw and his enemy in the civil war. Passions

reach a furious climax as Manrico and the

Count di Luna, now bitter rivals in love and

war, duel in mortal combat: Manrico is

victorious but spares di Luna’s life; Leonora

faints.

Il Trovatore Page 8

ACT II: “The Gypsy Mother”

Several months later. A gypsy camp in the

mountains of Biscay.

The warfare between Urgel and Aragon

continues unabated. Manrico, severely wounded

in the recent battle at Pelila, is recovering in

the gypsy camp where he is cared for by his

mother, Azucena.

In medieval times, many gypsies were

tinkers by trade: they are seen in their mountain

retreat working at their anvils.

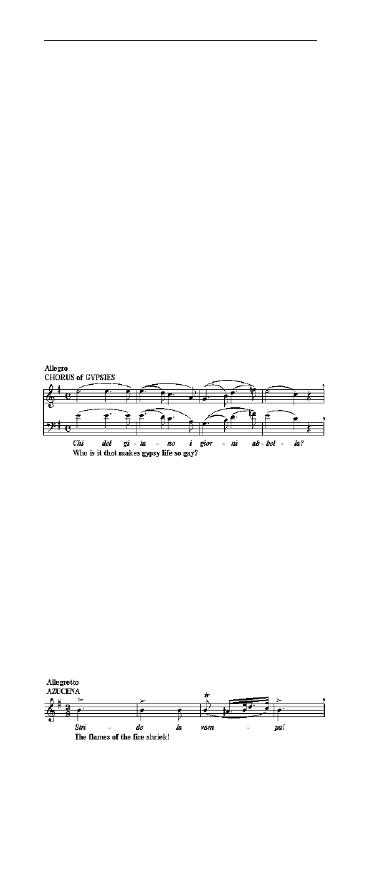

Chorus: Anvil Chorus

Azucena is a wild and hideous creature,

prematurely aged, and seemingly shattered in

her wits. Nevertheless, with her son Manrico,

she characterizes true motherly love,

tenderness, and affection.

Azucena stands by a fire on the very spot

where her mother was executed: She seems

mesmerized by the fire and craves revenge.

Azucena: Stride la vampa…

Azucena is obsessed, haunted, and

tormented by the memory of her mother’s

execution by the old Count di Luna. With

Manrico at her side, she relates the grim and

horrifying details of that dreadful moment.

Il Trovatore Page 9

Azucena’s tale begins where Ferrando’s

earlier story left off. Her mother was led to

the stake by the old Count’s soldiers, and she

followed behind while carrying her infant son

in her arms. Several times she tried to approach

her mother, but was driven off by di Luna’s brutal

soldiers. It was then, seething with revenge, that

she kidnapped the infant Garzía. She stood

before the pyres bearing both infants: her own,

and di Luna’s. Her mother was placed on the

pyres, barefoot and disheveled, and just before

her death, decreed her last words to her

daughter: Mi vendica, “Avenge me,” a grieving

plea that has remained eternally engraved in

Azucena’s soul.

Manrico asks Azucena: “And did you avenge

her?” Azucena reveals that in her heartbroken

and tormented state, she obeyed her mother’s

command for revenge, and flung the infant into

the flames. But in her delirium, dazed with hate

and grief, she made a terrible mistake and threw

her own son into the fire. When the horror

faded, there, lying beside her, was the Count di

Luna’s infant son, Garzía: Azucena murdered

her own child! Manrico reacts to her story with

shock and horror.

However, Azucena’s story bewilders

Manrico. If Azucena mistakenly cast her own

son into the fire, then who is he? Azucena

retracts her story and excuses herself,

explaining that she was overcome with a

momentary delirium; when she recalled those

gruesome events of her mother’s execution,

she became confused. Azucena immediately

reassures Manrico that she is indeed his mother,

and reminds him that after he was reported dead

at the battle of Pelila, she hastened there to give

him a proper burial, and when she found him

severely wounded, she nursed him back to

health with maternal devotion, care, and

tenderness.

Il Trovatore Page 10

After Azucena’s dreadful story ends,

Manrico, with soldierly pride, proceeds to

relate the details of his duel with the Count di

Luna. He reveals that he could have dispatched

him with ease, but some mysterious instinct

held him back, perhaps a voice from heaven

preventing him from striking the fatal blow.

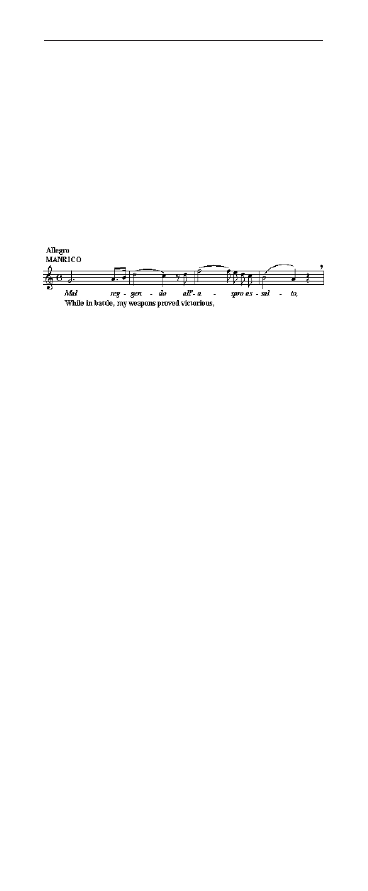

Manrico: Mal reggendo all’aspro assalto,

However, after Manrico hears his mother’s

tale about the horrors the di Lunas have

inflicted on her mother, he turns to sympathy

and sorrow, and vows revenge on the Count.

Azucena exults: Manrico has become her

instrument to fulfill her longed for revenge;

Manrico will exact justice for her mother’s

execution by the old Count di Luna.

Ruiz, Manrico’s lieutenant, announces that

the Count di Luna is planning to abduct Leonora.

Leonora believed that her beloved troubadour

had died in the battle of Pelila, and in her futility,

decided to enter a convent and take her vows.

Di Luna became aware of her intentions and

plans to kidnap her from the very threshold of

the convent. Manrico decides to gather his

troops and rescue Leonora.

Azucena becomes fearful and anxious. She

tries to dissuade Manrico with tears and

protests, appealing to him not to risk his life

while he is still weak from his wounds.

Nevertheless, Azucena is tormented by her

inner conflicts: Manrico has become her

instrument for revenge, and she fears that

losing him would defeat her life’s passion; at

the same time, she loves Manrico as a son,

and she fears for his safety.

Il Trovatore Page 11

Act II - Scene 2: The Cloister of the Convent

at Castellor

The Count di Luna believes Manrico died

in battle, therefore, all obstacles to possessing

Leonora have been removed. He plans to abduct

Leonora from the convent before she takes her

vows.

The Count reflects on his passionate love

for Leonora.

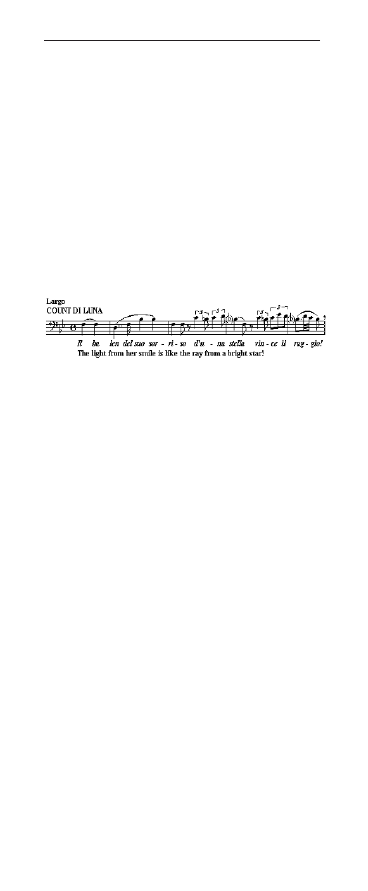

Di Luna: Il balen del suo sorriso…

A chorus of nuns solemnly condemn the

vanity of earthly possessions. Leonora, about

to take her vows and join the sisterhood,

expresses her hope that she may meet her

beloved Manrico among the souls in Heaven.

Count di Luna and his soldiers arrive to

abduct Leonora, and almost immediately

thereafter, Manrico appears to challenge him.

Suddenly, Manrico’s lieutenant, Ruiz, arrives

with soldiers of Urgel, overwhelm di Luna, but

all judiciously and respectfully avoid a

confrontation in the convent.

Leonora abandons her vows and

ecstatically falls into Manrico’s arms. Manrico

is given command of Castellor as di Luna

departs in a maniacal frenzy of frustration,

defeated passion, and disgrace: both enemies

curse each other and vow to continue their

rivalry until death.

Il Trovatore Page 12

ACT III – Scene 1:

“ The Gypsy Woman’s Son”

In the fortress of Castellor, Manrico and

Leonora prepare to be married.

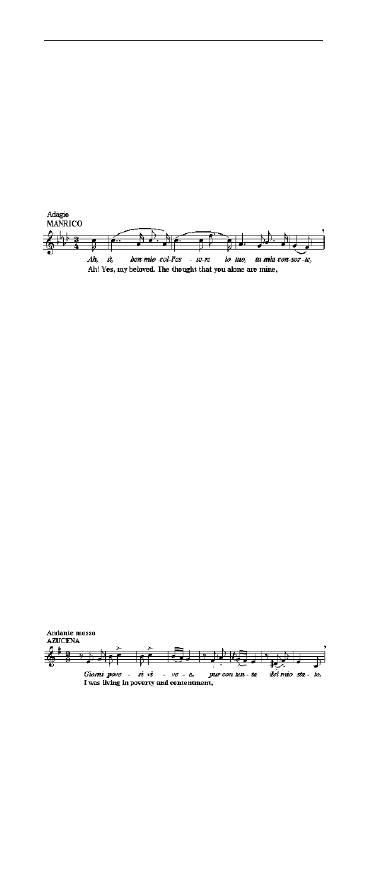

Manrico: Ah sì ben mio coll’essere io tuo,

Count di Luna and his soldiers have

surrounded the castle, intending to seize it and

capture Manrico and Leonora. In relishing his

victory, di Luna exults that he will have at his

mercy, Manrico, his enemy and rival, and finally,

Leonora, the woman for whom he lusts.

Azucena is captured while inadvertently

crossing through di Luna’s camp. Ferrando

interrogates Azucena, recognizes her, and is

fully convinced that she is their long desired

criminal, the gypsy’s daughter who kidnapped

the di Luna infant. Ferrando swears to di Luna:

“It is that wretched woman who committed the

horrid deed!” Azucena futilely tries to persuade

them that they are mistaken, but she is

condemned.

Azucena: Giorni poveri vivea,

Azucena is bound, and in desperation, cries

out to Manrico for help. The Count becomes

exultant when he realizes that he has captured

his rival’s mother. Without hesitation, he

orders Azucena to be executed on pyres to

be built in sight of his besieged enemy at

Castellor.

Il Trovatore Page 13

ACT III - Scene 2:

In Castellor, Manrico and Leonora are about

to be married, but they are suddenly interrupted

by Ruiz, who informs him that his mother

has been captured by di Luna’s forces and is

about to be burned on the stake. From a castle

window, Manrico becomes horrified when he

sees the fires being prepared. He summons his

troops, postpones his marriage, and informs

Leonora that his duty commands him to leave:

“I was a son before I became a lover!”

In an expanded moment of heroic resolution

and filial devotion, Manrico rushes off to

rescue his mother.

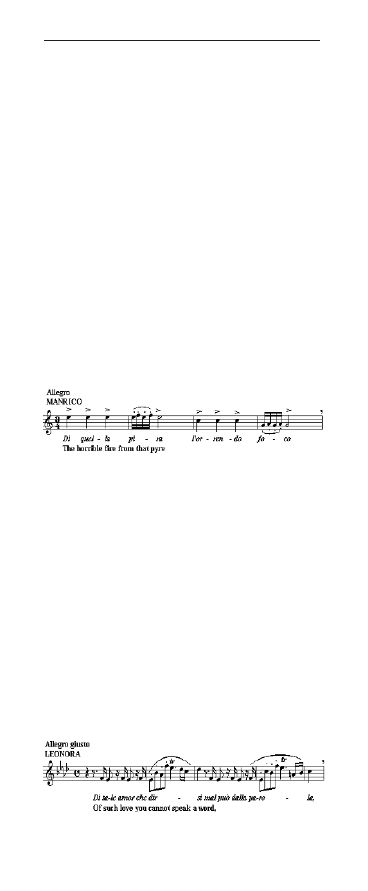

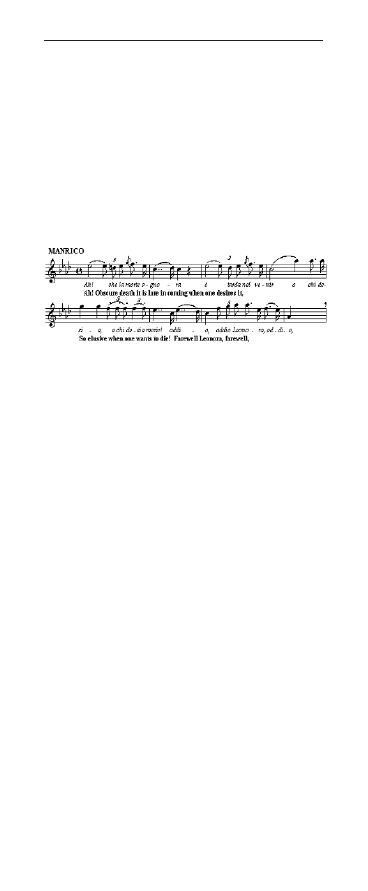

Manrico: Di quella pira…

ACT IV: - The Torture (or The Punishment)

Manrico failed in his efforts to save

Azucena. Castellor was overrun by di Luna

and his forces; Manrico was defeated and

captured, but Leonora escaped.

Manrico and Azucena are chained and

imprisoned in the tower of Aliaferia. Leonora

has come to Aliferia to negotiate with di Luna

to save Manrico: she will sacrifice her life for

Manrico; her ring contains poison.

Leonora: D’amor sull’ali rosee…

Il Trovatore Page 14

From outside the prison, chanting monks

pray for mercy for dying souls: the Miserere.

The troubadour is heard singing from his tower

cell: his last farewell to his beloved Leonora

and his desperate yearning for death to relieve

his agony. Leonora hears his passionate lament

and prays for mercy.

Manrico and Leonora: Miserere

The Count is seen relishing his victory at

Castellor: nevertheless, he is chagrined that he

failed to find Leonora. Suddenly, Leonora

appears before him.

Leonora pleads with di Luna to spare

Manrico’s life: in exchange, she offers herself

to him. Di Luna, overjoyed by his longed-for

victory, consents: “He shall live!” But Leonora

betrays him, and whispers aside: “You shall

possess me, but cold and lifeless!” Leonora

surreptitiously swallows a slow poison from

her ring. Nevertheless, di Luna is ecstatic: he

has finally won Leonora and satisfied his

passion, albeit without honor.

ACT IV – Scene 2: Inside the tower

Manrico soothes his weak, terrified, and

distraught mother. She has become crazed in

realizing that she is to be burned alive, and again

recalls the horror of her mother’s execution.

To avoid the reality of their doomed fate, they

nostalgically dream about returning to the

freedom in the mountains of Biscay.

Il Trovatore Page 15

Manrico and Azucena: Ai nostri monti..

Suddenly, Leonora arrives at the prison and

announces that Manrico is free. Manrico turns

to rage when he speculates on the price she

paid for his freedom; his honor is offended.

However, Leonora reveals her sacrifice, telling

him that “Rather than live for another, I chose

to die for you”: Manrico’s joy turns to despair.

Count di Luna appears at the cell, sees

Leonora and Manrico embraced, and bitterly

realizes that she betrayed him. Suddenly,

Leonora dies from the poison: Manrico is

ordered to his execution, and bids a last farewell

to his mother.

The Count drags Azucena to the tower

window and forces her to watch her son’s

execution. As the blade falls, Azucena cries out:

“He was your brother!” Di Luna shrieks with

horrified anguish at the headless body of the

man he has just executed: his brother, Garzía di

Luna. Fratricide becomes di Luna’s final horror

as he shouts in terrified torment: “Yet I am

still alive.”

Azucena’s obsession for revenge has

destroyed the spirit and soul of Count di Luna.

Deliriously, she proclaims her victory, the

triumph of her irrational passion: “Mother, you

are avenged!”

Il Trovatore Page 16

Il Trovatore Page 17

Verdi…..……………………and Il Trovatore

A

t mid-point in the nineteenth century, the

37 year-old Giuseppe Verdi had become

acknowledged as the most popular opera

composer in the world: his operas were the

opera box office rage, and some concluded

that he single handedly had all of Italy - and

the world – singing his music. Verdi’s operas

were Italian to the core, dutifully preserving

the great legacy and traditions of his immediate

predecessors, the bel canto giants, Rossini,

Bellini, and Donizetti: In Verdi’s operas, voice

and melody remained the supreme core of

the art form.

Viewing the opera landscape at mid-century,

Rossini had retired almost 20 years earlier,

Bellini died in 1835, Donizetti died in 1848,

the premiere of Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète took

place in 1849, and Wagner’s Lohengrin

premiered in 1850. Seemingly, the only active

opera composer whose works were capable

of mesmerizing audiences was Verdi.

Between the years 1839 and 1850, Verdi

composed 15 operas. His first opera, Oberto

(1839), indicated promise for the young, 26

year-old budding opera composer, but his

second opera, the comedy, Un Giorno di

Regno (1840), was not only received with

indifference, but was a total failure.

Verdi’s third opera, Nabucco (1842),

became a sensational triumph and catapulted the

him to immediate world-wide critical and

popular acclaim. He proceeded to follow with

one success after another: I Lombardi (1843);

Ernani (1844); I Due Foscari (1844);

Giovanna d’Arco (1845); Alzira (1845); Attila

(1846); Macbeth (1847); I Masnadieri (1847);

Il Corsaro (1848); La Battaglia di Legnano

(1849); Luisa Miller (1849); and Stiffelio

(1850).

Il Trovatore Page 18

Verdi’s early operas all contained an

underlying theme: his patriotic mission for the

liberation of his beloved Italy from oppressive

foreign rule: particularly, France and Austria.

Verdi, with his operatic pen, sounded the alarm

for Italy’s freedom: The underlying stories in

his early operas were disguised with allegory

that advocated individual liberty, freedom, and

independence for Italy; the suffering and

struggling heroes and heroines in those early

operas were metaphorically his beloved Italian

compatriots.

In Giovanna d’Arco (“Joan of Arc” 1845),

the French patriot Joan becomes a martyr after

she confronts the oppressive English, the

French monarchy, and the Church: the heroine’s

plight, synonymous with Italy’s struggle against

oppression. In Nabucco (1842), the biblical

story of Nebuchadnezzar, the suffering

Hebrews, enslaved by the Babylonians, were

allegorically the Italian people themselves,

similarly in bondage by foreign oppressors.

Verdi’s Italian audience easily understood

the underlying messages subtly injected

between the lines of his text and nobly

expressed through his musical language. At

Nabucco’s premiere, at the conclusion of the

Hebrew slave chorus, Va Pensiero, the

audience stopped the performance for 15

minutes with wildly inspired shouts of Viva

Italia: an explosion of nationalism that, in

order to prevent riots, forced the authorities

to assign extra police to later performances

of the opera. The Va Pensiero chorus became

the emotional and unofficial “Italian National

Anthem,” the musical inspiration for Italy’s

patriotic aspirations. Even the name V E R D

I had a dual meaning: homage to the great

maestro expressed as Viva Verdi, and the

letters V E R D I denoted Vittorio Emanuelo

Re D’ Italia: The return of King Victor

Emmanuel was synonymous with Italian

liberation and unification.

Il Trovatore Page 19

As the 1850s unfolded, Verdi’s creative

genius had arrived at a turning point in terms

of his artistic inspiration, evolution, and

maturity. He felt satisfied that his objective

for Italian independence was soon to be

realized: the Risorgimento of 1861 made

Italian nationhood a fait accompli.

Verdi now decided to abandon the heroic

pathos and nationalistic themes of his early

operas. He began to seek more profound

operatic subjects: subjects that would be bold

to the extreme; subjects with greater dramatic

and psychological depth; subjects that accented

spiritual values, intimate humanity, and tender

emotions. He became ceaseless in his goal to

express the human soul on the operatic stage

more profoundly that it had ever been realized.

The year 1851 inaugurated Verdi’s “middle

period,” a defining moment in his career in

which his operas started to contain heretofore

unknown dramatic qualities, a profound

characterization of humanity, and an exceptional

lyricism. Verdi’s creative art began to flower

into a new maturity with operas that would

eventually become some of the best loved

works composed for the lyric theater: Rigoletto

(1851); Il Trovatore (1853); La Traviata

(1853); I Vespri Siciliani (1855); Simon

Boccanegra (1857); Aroldo (1857); Un Ballo

in Maschera (1859); La Forza del Destino

(1862); Don Carlos (1867); and Aïda (1871).

As Verdi approached the twilight of his

prolific operatic career, he was supposed to be

relishing his “golden years.” It was a time when

the fires of ambition were supposed to become

extinguished, and a time when most people

become spectators in the show of life rather

than its stars. However, the great opera

composer defied the natural order and

epitomized the words of Robert Browning’s

Rabbi Ben Ezra: “Grow old along with me. The

best is yet to be.”

Consequently, Verdi overturned the

Il Trovatore Page 20

equation and transformed his old age into a

glory: “The best is yet to be” became his last

two operatic masterpieces, Otello (1887), and

Falstaff (1893), both composed respectively

a the ages of 74 and 80. These operas are

unprecedented in their integration between

text and music and in their internal,

architectural organic integration: they are

considered by many to be the greatest Italian

music dramas and tour de forces in the entire

canon. Verdi eventually composed 28 operas

during his illustrious career, dying in 1901 at

the age of 88.

I

n 1851, Verdi was approached by the

management of La Fenice in Venice to write

an opera to celebrate the Carnival and Lent

seasons. In seeking a story source for the opera,

Verdi turned to the new romanticism of the

French dramatist, Victor Hugo, a writer whose

Hernani he successfully treated in his opera

Ernani seven years earlier in 1844.

Victor Hugo’s play, Le Roi s’amuse, “The

King Has a Good Time,” portrayed the libertine

escapades and adventures of François I of

France (1515-1547), the drama featuring as

its unconventional protagonist, an ugly,

disillusioned, hunchbacked court jester named

Triboulet: he was an ambivalent and tragically

repulsive character who possessed two souls;

physically monstrous, morally evil, and wicked

personality, but simultaneously, a

magnanimous, kind, gentle, and compassionate

man showering unbounded love on his beloved

daughter. Hugo’s Triboulet became Verdi’s title

character in his opera Rigoletto (1851), the

opera that inaugurated his “middle period,” that

monumental transitional period in his

compositional career in which he began to

develop more profound operatic subjects.

Verdi’s immediate triumph with Rigoletto

in 1851 inspired and propelled him forward.

Il Trovatore Page 21

Almost simultaneously, he began working on

the composition of his next two operas: Il

Trovatore (Premiere in January 1853), and La

Traviata (Premiere in March 1853). As a tribute

to Verdi’s genius, no two operas could be so

distinctly different in character and style. Il

Trovatore is a Romantic melodrama full of

“blood and thunder” musical explosions,

which owes much of its structural provenance

to the early 19

th

century bel canto traditions.

La Traviata is a magical and sublime musical

portrait of a tragic heroine, a bittersweet

symphonic-type of opera that sweeps like an

emotional tide as it conveys powerful moments

of emotional truth in each stage of the heroine’s

tragic plight.

I

l Trovatore is based on the 1836 play, El

Trovador, written by García Gutiérrez, a

renowned early 19

th

century Spanish romantic

playwright. Gutiérrez’s play was extremely

popular and inherently a perfect operatic

subject for Verdi: its flamboyant melodrama

is saturated with fantastic, complicated, and

bizarre incidents, together with extreme

passions of love and noble sacrifice. The

play’s intrigues provided Verdi with an

opportunity to fulfil his new ambitions to inject

novel, unconventional, unusual, and bizarre

themes into his opera stories.

In the Romantic era, most underlying opera

stories never strayed far from established well-

known plays and novels. Thus, many opera

stories during the period were adapted from

recognized great works: Schiller, Shakespeare,

Byron, Hugo, Scott, and Bulwer-Lytton. In

effect, opera stories in the Romantic era were

equivalent to the cinema of a 100 years later:

they satisfied the public’s thirst to have

successful books or plays transformed into a

different medium. Thus, Gutiérrez’s play, a

popular romantic melodrama that overflowed

Il Trovatore Page 22

with consuming passions, as well as

Alexandre Dumas fils’ equally popular novel,

La Dame aux Camélias, became Verdi’s

choices for the underlying stories for the

operas that would follow Rigoletto: Il

Trovatore and La Traviata.

Salvatore Cammarano became Verdi’s

personal choice to write the libretto for Il

Trovatore. He had written the libretti for

Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor (1835), and

earlier, Verdi’s own Alzira (1845) and La

Battaglia di Legnano (1849). Verdi

considered Cammarano a quintessential

operatic poet, in particular, a genius with a very

special flair for words: Cammarano was the

poet whom he hoped would later fulfill his life-

long ambition to bring Shakespeare’s King Lear

to the opera stage, a dream that never reached

fruition.

Cammarano’s literary genius skillfully

transformed the Gutiérrez El Trovador play

into a dramatically scintillating opera.

Nevertheless, the final libretto has become one

of the enigmas of the opera world. Many opera

aficionados and critics believe that no study of

Il Trovatore’s complicated plot can make it

coherent or intelligible: it reputedly took Verdi

21 days to complete Il Trovatore, but for

many, an intellient understanding of the story

has become a more time consuming feat.

Part of the difficulty in understanding the

Il Trovatore story arises from Cammarano’s

literary style: the poet relished the opportunity

to add variations and obscurities to the story.

But the real complication is attributed to his

penchant for flowery diction and pompous

prose, a style which owes its origin to the old

fashioned libretto Italiano tradition of the time.

Cammarano’s genius with words created a

language that at times seemed stilted and

monotonous: bells were never bells but “sacred

bronzes”; and midnight was traditionally the

Il Trovatore Page 23

“hour of the dead.” Adding to the later

coherence dilemma of Il Trovatore, many

later English translations of the story have

tended to err and blunder in their translation

and explanation of the plot.

W

hen the curtain rises on Il Trovatore, the

years 1409 and 1410, a murderous civil

war is being fought for the succession to the

Spanish throne. Manrico is the hero of the story:

he is a troubadour, one of those knightly poet-

musicians from Medieval times, the archetype

of courtly love. He is the “son” of the gypsy,

Azucena, and fights for the cause of the

pretender, the Duke of Urgel: the current

Count di Luna leads the armies of King Juan

I of Aragon. Manrico and di Luna, enemies

in war, are also rivals for the hand of Leonora,

a lady-in-waiting to the Queen of Aragon. The

underlying irony and ultimate tragedy of the

story revolves around the fact that these two

men, violent enemies in war and bitter rivals

in love, are unaware that they are brothers.

ll Trovatore is a fantastic horror tale in the

true Gothic genre. As such, its story hinges on

an incident that took place 15 years before

the curtain rises: the execution of the gypsy

Azucena’s mother by the old Count di Luna.

The engine that drives the entire Il Trovatore

melodrama is fueled by Azucena’s revenge

for her mother ’s execution. Azucena’s

character was so dominating in the original

Gutiérrez story that the English stage version

bore the title, The Gypsy’s Vengeance.

In the fifteenth century, the Spanish gypsy

population was a tiny minority that had drifted

from southern France. They were perceived by

society as a detested underclass, stereotyped

and denounced for licentiousness, treason,

and heresy, the kidnapping of children, and a

variety of unholy acts. Likewise, they were

Il Trovatore Page 24

hated and feared for their dark skins, their

silver earrings, and blanket-like garments, and

most of all, for their thievery. The Church

became paranoid with the gypsy population,

considering them sorcerers whose witchcraft

was condemned as heresy and blasphemy.

The Inquisition, created in 1480 (and

abolished some 350 years later in 1834)

persecuted the gypsy population as pagans

and witches; bishops even excommunicated

persons as heretics who let gypsies read their

palms.

The gypsies in the Il Trovatore story,

Manrico, Azucena, and her earlier executed

mother, would automatically have become

victims of those tides of hate where the

supreme punishment for their presumed

sorcery was execution at the stake. The stake

became the highly visible vehicle for

punishment and retribution against

blasphemers: the Czech reformer Jan Hus was

burned in 1415, and Joan of Arc was condemned

as a witch in 1431. According to the Il

Trovatore story’s time-frame, Azucena’s

mother would have gone to the stake in 1394,

15 years before the curtain rises, and

Azucena’s death would have taken place when

the curtain falls in 1410.

The di Luna family in the Il Trovatore story

bear the customary suspicion of gypsies. After

the di Luna infant son became deathly ill, the

old Count was convinced that the child’s illness

was caused by an “evil eye” curse cast on him

by an old gypsy who had been seen nearby. The

gypsy was apprehended, condemned, and

immediately burned alive at the stake.

Her daughter, Azucena, witnessed her

mother ’s horrible execution, became

traumatized and delirious, and heeding her

mother’s last invocation, swore revenge

against the di Luna family. Azucena kidnapped

the sick di Luna infant, intending to exact

retribution by casting him into the smoldering

Il Trovatore Page 25

fire, but in her craze and frenzy of the

moment, she accidentally cast her own son

into the fire. The child whom she would

eventually escape with would actually be the

di Luna infant son, Garzía, the di Luna child

she would rear as her son, Manrico.

However, within this melodrama of

frenzied, irrational passions, there flowers an

almost transcendental love between Manrico

and Leonora: their love fuels a violent rivalry

between Manrico and di Luna for Leonora’s

hand. Nevertheless, the core of the story and

the engine that propels the melodrama, remains

Azucena’s lifelong obsession for vengeance

against the di Luna family: it is the gypsy

daughter ’s resolve which drives the Il

Trovatore to its ultimate, tragic conclusion.

L

eonora and Azucena, Il Trovatore’s principal

female characters, are brilliantly

contrasting characterizations, each of whom

inhabits opposite ends of the human spectrum.

Leonora is the heroine of the story, the

ultimate portrait of a woman capable of

profound love as well as unquestionable

religious faith. However, Leonora becomes a

victim of an incomprehensible and

imperceptible world surrounding her with

violent human hatred and brutality. She faces

that eternal conflict of the sacred vs. the

profane: she forgoes her vows at the convent

when Manrico suddenly appears, and in the end,

she commit suicide by taking poison,

sacrificing her life for her beloved Manrico.

Leonora is a noble heroine trapped in the

conflicts and tensions of her fate and destiny.

Verdi honors her through his sublime music,

providing her with melodies that seem to be

minted from pure musical gold. Leonora’s

music contains aspiring and inspiring qualities

with phrases that are rich, lavish, arching,

and soaring: her Act I aria, Tacea la notte, in

Il Trovatore Page 26

which she describes her first acquaintance

with Manrico; her Act II, Scene 2, Sei Tu

dal ciel, the glorious rescue ensemble; and in

Act IV, D’amor sull’ali rosee, her expression

of undaunted passion for Manrico before she

embarks on her doomed sacrifice.

Azucena is the keystone of the Il Trovatore

melodrama, and without her, the opera could

not exist: Azucena is the engine of vengeance

who drives the entire drama. Even more

profoundly than Leonora, Verdi musically

sculpted the character of Azucena with a

heretofore unknown depth.

Azucena was an entirely new figure in

Verdi’s female gallery of singers: up until Il

Trovatore, Verdi had never made significant use

or exploited the dramatic qualities of the

mezzo-soprano or contralto voice in a principal

role. The introduction of Azucena in Il

Trovatore represents the beginning in a glorious

line of darker female voices: Ulrica in Un Ballo

in Maschera, Eboli in Don Carlo, and Amneris

in Aïda.

Azucena’s bizarre character drives the plot

with her two great passions: her maternal love

for Manrico, and her obsessive passion to

avenge her mother’s execution. Azucena is a

swarthy and ominous character who swaggers

savagely as she recounts the vivid horror of

how her mother was led to execution, and in

her delirium, murdered her own infant son.

The tragedy of the story is that her vengeance

leads her to destroy Manrico, the one being

in the world whom she loves.

Azucena is the counterpart of another

grotesque character whom Verdi had created

only two years earlier in 1851: Rigoletto.

These two Gothic-type characters, Rigoletto

and Azucena, are repulsive outsiders, in many

respects, shocking forces to Verdi’s nineteenth

century audiences, who expected to see only

beautiful heroines and handsome heroes

Il Trovatore Page 27

onstage; villains could be ugly, but they were

only to be presented as secondary figures.

During Verdi’s “middle period,” he was at

a critical turning point in his operatic evolution:

he was seeking more profound

characterization and was willing to stretch the

imagination in his search for the bizarre; he

insisted on making major protagonists out of

Rigoletto, a mocked and cynical hunchback,

as well as Azucena, a reviled and

stereotypically ugly gypsy witch.

These two monstrous characters share

similar evil demons and destinies: Rigoletto

brings about the death of his own daughter,

murdered by the assassin he hired to murder

the Duke of Mantua; Azucena causes the death

of Manrico, the surrogate son she adores, first

by claiming under di Luna’s torture that she is

his mother, and secondly, and more importantly,

by hiding from di Luna the fact that he and

Manrico are actually brothers.

Azucena could have saved Manrico, but

possessed with revenge, she did not: she

becomes the horrible, immoral spirit of

destructive humanity. Rigoletto and Azucena

are, therefore, the male and female faces of

defeated revenge: revenge that ultimately

brings about fatal injustice and tragedy. Both

operas, Rigoletto and Il Trovatore, are

tragedies imbedded with irony. The final

horror for both Rigoletto and Azucena is that

they believe they are exacting justice.

Rigoletto proclaims: Egli è delitto, punizion

so io, “He is crime, I am punishment.”

Azucena, expressing the sinister leitmotif of

Il Trovatore, repeatedly proclaims her dying

mother’s decree: “Mi vendica, “Avenge me.”

Nevertheless, in the end, both see their beloved

children lying dead, the only difference

between them is that Rigoletto probably lives

on in agony, haunted by his misdeed; Azucena

surely died at the stake as did her mother.

Il Trovatore Page 28

T

emperamentally, Verdi was an idealist, a

true son of the Enlightenment, who

possessed a noble conception of humanity.

He abominated absolutism and deified civil

liberty, which ultimately resulted in his lifelong

manifesto and crusade against tyranny;

personal, social, political, or ecclesiastical. His

operas, Don Carlos (1867) and Aïda (1872),

if anything, resound with profound underlying

socio-political statements about the abuse and

corruption of power, and the inherent

impotence it inflicts on humanity.

Verdi was also a pessimist and skeptic who

perceived a cruel and unjust world, irrational,

and hypocritical in its promises of human

progress. Many experiences in his life were

recalled with much bitterness: as an infant, his

mother fled with him to escape vindicating

Russians who were venting their hatred against

Napoleon with blind slaughter; his two children

and young wife died early in his life; his mother

died the year before Il Trovatore; librettist

Cammarano died in the midst of writing the

libretto for Il Trovatore; and many of his noble

social, and political ideals seemed to be

degenerating in fin du siecle Europe.

The characters in Il Trovatore represent

emotionally charged symbols of Verdi’s

pessimistic view an existential and hostile

world. The story possesses no redemptive

values, but rather, a profound and dramatically

truthful portrayal of irrational obsessions,

intense emotions and passions, pathos, and

despair. All the characters suffer intensely:

Manrico/Garzía is a lonely man, doomed to the

cruelty of war but momentarily redeemed

through Leonora’s love; he is executed

without ever knowing his real identity.

Leonora is unable to comprehend the hostility

and violence surrounding her: she sacrifices

herself, preferring a martyred death rather

than the lust-crazed di Luna. Di Luna is

irrational and virtually insane in his insatiable

Il Trovatore Page 29

lust for Leonora, the woman he tries to

possess but cannot: he ultimately transforms

his life into an obsession with hatred which

nurtures the story’s final horror and tragedy:

killing his own brother.

The true tragic character in Il Trovatore

is Azucena, the woman of powerful irrational

passions. She triggers the melodrama’s ultimate

tragedy by killing the man who had indeed

become her son; the son she could have saved

by revealing to di Luna that he was indeed his

brother. For Verdi, Azucena’s persona is the

essence of the underlying story of Il

Trovatore: she is the ultimate symbol of a

universe of cruel creatures; humanity

possessing destructive, irrational powers and

passions.

I

l Trovatore is saturated with melodic vitality,

energetic musical inventions, and an

explosion of eminently beautiful lyricism that

possess a driving, propulsive quality. The

opera’s characterizations are sharp and

contrasting, and together with its super-charged

emotions, it swiftly speeds from climax to

climax.

In retrospect, Il Trovatore is a 150 year old

phenomenon whose impact remains unique

and seemingly eternal in the world of Italian

opera, an overwhelmingly popular and

perennial favorite: of all of Verdi’s output, it

was the most loved opera in his own day.

At the time of Il Trovatore, Richard

Wagner’s theories of the Gesamtkunstwerk, the

ideal of the total artwork, began to infest the

European opera world. Those theories

idealized opera as music drama, a goal that

could be achieved through a synthesis and

fusion of text, music, and all other art forms.

As the second half of the 19

th

century

unfolded, Wagner and his theories eventually

revolutionized the opera art form: his theories

Il Trovatore Page 30

worked well for him; Verdi’s techniques

equally suited his own style as well as those

of his audiences.

Verdi’s Il Trovatore is a score saturated with

bel canto, “oom-pah-pah hit-parade” songs,

“organ grinder” music, and many of its

accompaniments locked to dance rhythms.

Theoretically, Il Trovatore represents the

antithesis of Wagnerism: it was the essence of

an intolerable Italianism in lyric drama, and the

devils were Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, and,

of course, Verdi; Wagner was obsessed to

rescue and redeem the world from their

artistic evil. Wagner introduced his music

dramas, the Ring cycle and Tristan and

Isolde. After Il Trovatore, Verdi’s style

progressed and matured to grander levels, and

his operas became more organically unified

in terms of their musical and dramatic

integration. Likewise, the Italian opera school

conceived its own music of the future: the

verismo style of Mascagni, Leoncavallo, and

Puccini.

Il Trovatore represents the end of a

particular era and genre of Italian opera: it is

the last of the great Italian Romantic

melodramas. However, it is a work which

evolved from early and mid-nineteenth century

opera styles: it represents the sum and

substance of Italian opera, because its focus

is voice and song, essential ingredients that

will survive until the whole structure of Italian

opera will have disappeared. Verdi himself

would eventually leave the Il Trovatore style

far behind him and eloquently advance toward

his own indelible musico-dramaticism in his

last four operas: Don Carlo, Aïda, Otello and

Falstaff. Nevertheless, his Il Trovatore

continues to remain a jewel in his operatic

crown.

But the ultimate greatness of Il Trovatore

is that it reverently and piously follows the

great Italian traditions in which the voice,

Il Trovatore Page 31

song, and melody, remain the supreme focus

of the opera. Verdi saturated this score with

unforgettable musical gems, which seem to

become brighter over time: Leonora’s Tacea

la notte, the Anvil Chorus, Azucena’s wild

ballad Stride la vampa, di Luna’s Il balen,

Manrico’s Mal reggendo, and Di quella pira,

and every note of the Tower Scene, Miserere,

and the final Prison Scene. These musical

inventions represent a magnificent legacy

which become imbedded in the mind just as

familiar sentences from literature become

catch-phrases and proverbs.

Since Il Trovatore, new currents and trends

have arisen in opera, and there are certainly

vastly more intelligible and cohesive opera

dramas. Nevertheless, Il Trovatore is firmly

rooted to the opera stage; its devoted audiences

continually hypnotized by the lyric splendor

Verdi provided for his troubadour of Aliaferia

whose serenades and last addio seem to

become engraved in memory not only after

the curtain falls, but for eternity.

Il Trovatore is one of Verdi’s most supreme

lyrical masterpieces, a work without parallel in

the entire operatic canon: a late flowering of

the great Italian romantic tradition. It is

saturated with masterful melodic inventions,

and lush and vividly beautiful music that are

fused with powerful dramatic passion and

power. This virtually unique opera runs like a

thoroughbred, breaks out of the gate, and

charges to the finish line where all of its

romantic agony and Gothic horror unite in

magnificent and thunderous lyric splendor: Il

Trovatore provides the sounds and furies of

towering passions. •

Il Trovatore Page 32

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Verdi Il Trovatore libretto

Verdi Leonora Il Trovatore IV Act

il gioco e di tutti

A2-3, Przodki IL PW Inżynieria Lądowa budownictwo Politechnika Warszawska, Semestr 4, Inżynieria kom

slajdy TIOB W27 B montaz obnizone temperatury, Przodki IL PW Inżynieria Lądowa budownictwo Politechn

francuski mieszkanie, il y a, przyimki

test z wydymałki, Przodki IL PW Inżynieria Lądowa budownictwo Politechnika Warszawska, Semestr 4, Wy

OPIS DROGI, Przodki IL PW Inżynieria Lądowa budownictwo Politechnika Warszawska, Semestr 4, Inżynier

Irek, Przodki IL PW Inżynieria Lądowa budownictwo Politechnika Warszawska, Semestr 4, Inżynieria kom

spr3asia, Przodki IL PW Inżynieria Lądowa budownictwo Politechnika Warszawska, Semestr 4, Wytrzymało

norme per il dottorato

slajdy TIOB W07 09 A roboty ziemne wstep, Przodki IL PW Inżynieria Lądowa budownictwo Politechnika W

ściaga - trzonowce, Budownictwo IL PW, Semestr 7 KBI, METAL3

ściąga - zbiorniki, Budownictwo IL PW, Semestr 7 KBI, METAL3

Wykonanie kładki dla pieszych D-opis, Przodki IL PW Inżynieria Lądowa budownictwo Politechnika Warsz

Calvino Il visconte dimezzato

więcej podobnych podstron