Representations of

Non-Suicidal Self-Injury

in Motion Pictures

Christopher Trewavas, Penelope Hasking, and Margaret McAllister

The aim of this study was to investigate representations of non-suicidal self-injury

(NSSI) in popular media. Forty-one motion pictures were viewed, coded, and ana-

lyzed. NSSI was correlated with mental illness, child maltreatment, and substance

abuse. NSSI was generally portrayed as severe, habitual and covert. Further, depic-

tions of NSSI were often sensationalized and featured prominently. NSSI was less

likely to be associated with completed suicide than other psychological factors, but more

closely associated with suicide than NSSI is in the community. Although NSSI was

associated with psychiatric illness, few characters were receiving psychiatric care at the

time of NSSI. However a significant proportion received support after engaging in

NSSI. The portrayal of NSSI is generally accurate regarding correlates and function,

but is inaccurately associated with suicide. Implications of the relatively accurate

portrayal of NSSI are discussed in light of the potential for imitation, and the possi-

bility of using cinematherapy to promote effective problem resolution.

Keywords

film, media representations, non suicidal self injury, self harm, self injury

Non-suicidal self-injury is a prevalent and

acute psychological health concern. Corre-

lated with multiple risk factors, NSSI is

defined as the deliberate direct self-inflicted

damage of body tissue, and is differentiated

from suicidal behavior by the absence

of suicidal intent (Nock, 2009). Although

NSSI is a risk factor for suicide, it is more

aptly characterised as a coping mechanism,

engaged as a method of affect regulation

(Klonsky, 2007; Welch, Linehan, Sylvers

et al., 2008), interpersonal regulation (Nock

& Prinstein, 2004, 2005), or physiological

arousal (Nock & Mendes, 2008).

Consistent with the phenomenon of

suicide contagion (Bollen & Phillips, 1982;

Hassan, 1995; Martin, 1998; Phillips, 1974,

1985; Romer, Jamieson, & Jamieson, 2006),

preliminary research reveals that media

depictions of drug overdose influence

imitative acts of self-poisoning (Hawton,

Simkin, Deeks et al., 1999). Although not

directly examined, media depictions of

NSSI might also prompt imitative behavior.

However, media depictions of NSSI may

also serve as a useful clinical tool, if

effective problem resolution is depicted.

Thus, it is important to understand how

NSSI is portrayed in popular media culture,

and to consider the possible effects of its

portrayal on audiences.

Nature and Extent of NSSI

In order to determine whether the

portrayal of NSSI in motion pictures is

accurate, it is first necessary to summarize

the current state of knowledge concerning

Archives of Suicide Research, 14:89–103, 2010

Copyright # International Academy for Suicide Research

ISSN: 1381-1118 print=1543-6136 online

DOI: 10.1080/13811110903479110

89

NSSI. Although prevalence estimates of

NSSI vary according to the definition used

and means of assessment, studies prompt-

ing participants to recall specific forms of

NSSI (including cutting, burning wound

interference, head banging, etc.) suggest

the prevalence may be as high as 46.5%

(Lloyd-Richardson, Perrine, Dierker et al.,

2007) for community samples of adoles-

cents, 43.6% (Hasking, Momeni, Swannell

et al., 2008) for community samples of

adults (aged 18–30 years) and 38% in col-

lege students (Gratz, Conrad, & Roemer,

2002). Studies using a more stringent

approach, suggest the prevalence may be

between 10% and 20% (DeLeo & Heller,

2004; Ross & Heath, 2002). Correlated with

maladaptive

cognitions

(Muehlenkamp,

2006), peripheral serotonin levels (Crowell,

Beauchaine, McCauley et al., 2008), dis-

sociation (Armey & Crowther, 2008), bor-

derline personality type (Welch, Linehan,

Siylvers et al., 2008), deficits in problems

solving ability (Nock & Mendes, 2008),

child abuse (Glassman, Weierich, Hooley

et al., 2007), post-traumatic stress (Weierich

& Nock, 2008), and alcohol abuse (Hasking,

Momeni, Swannell et al., 2008; Williams &

Hasking, in press), NSSI is motivated by a

combination of interacting physiological,

interpersonal

and

intrapsychic

factors

(Crowell, Beauchaine, McCauley et al., 2008;

Heath, Toste, Nedecheva et al., 2008; Nock

& Mendes, 2008). Klonsky (2007) identified

affect regulation and self-punishment as the

most commonly reported functions of

NSSI, and Hilt, Cha, and Nolen-Hoeksema

(2008) recently reported affect regulation as

the primary function of NSSI among

adolescent women.

The Werther Effect

Extant research indicates that media

may play a role in the decision to engage

in NSSI, either by direct modeling or

in conjunction with pre-existing contribu-

ting factors such as suicidal ideation or

psychological distress. Nixon, Cloutier

and Jansson (2008) reported that 29% of

a community sample of adolescents (mean

age ¼ 15.2 years) had gained the idea to

engage in NSSI from friends, 15.1% from

television or movies, and 11.8% from read-

ing material. Hawton, Simkin, Deeks et al.

(1999) reported a 17% increase in cases

of overdose (including paracetamol and

non-paracetamol overdoses) after the airing

of a television program featuring scenes of

paracetamol overdose.

The phenomenon of copycat suicidal

behavior, commonly referred to as the

‘‘Werther effect,’’ indicates the influence

of media imagery on human behavior. Such

a phenomenon needs to be taken into

account

when

exploring

triggers

that

exacerbate the incidence and risk of NSSI.

Despite a dearth of literature on the influ-

ence of media portrayals of NSSI on

self-injurious behavior and attitudes to

self-injury, the ‘‘Werther effect’’ has been

substantiated by empirical research, parti-

cularly in cases involving celebrities (Stack,

2005) or where suicide method is explicitly

described (Martin, 1998). The ‘‘Werther

effect’’ is believed to be more likely

depending on how suicide is portrayed in

the media (Gould, Wallenstein, & Davidson,

1989; Motto, 1970; Phillips & Carstensen,

1988). There is an increased risk of

imitative suicide when non-fictional acts

of suicide are glorified (Martin, 1998), sen-

sationalized (Stack, 2003), portrayed repeat-

edly, or featured prominently in popular

media culture (Hawton, Rodham, & Evans,

2006; Martin & Koo, 1997; Pirkis & Blood,

2001). Accordingly, sensationalist media

coverage of suicidal behavior is now con-

sidered unethical, and is subject to litigation

(Martin, 1998; Pirkis & Blood, 2001; Stack,

2003). However, despite the likelihood that

media coverage of NSSI may similarly

impact on the attitudes and behavior of

viewers, specific guidelines for the appro-

priate reporting of NSSI are apparently

yet to be formulated.

NSSI in Motion Pictures

90

VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1 2010

Similarly, social cognitive theory holds

that people can learn vicariously by model-

ing the behavior of others (Bandura, 1986).

In cases where individuals identify with a

model, the risk of imitating that model’s

behavior is increased. Thus, individuals

are more likely to identify with, and subse-

quently imitate, the behavior of realistic or

non-fictional representations of suicidal

behavior (Stack, 2003, 2005), and arguably

NSSI. A key component of social cognitive

theory is the expectation of a dose-

response effect (Pirkis & Blood, 2001).

That is, the likelihood of imitative NSSI

is theoretically proportionate to the num-

ber of models shown engaging in NSSI,

and how often their self-injurious behavior

is publicized. However, the risk of imitative

NSSI is also determined by the perceived

consequences of the model’s actions (Ban-

dura, 1977, 1986). Thus, media images that

depict NSSI as being rewarded or rein-

forced may increase the likelihood that

viewers who are vulnerable to self-injurious

behavior will engage in NSSI.

The Influence of Motion Pictures

The cinema is a definitive model of

contemporary media culture and, given

the global distribution and accessibility of

the medium of film, movies featuring

scenes of NSSI have the potential to

exert a wide-ranging and potent influence

(Wedding & Niemiec, 2003). To illustrate,

Zahl and Hawton (2004) investigated the

influence of audiovisual media (e.g., tele-

vision, the internet, motion pictures) on

deliberate self-harm (self-poisoning and self-

injury) among a clinical sample who had

recently engaged in deliberate self-harm,

and reported that scenes of self-harm fea-

tured in the films Girl Interrupted (Mangold,

2000) and The Virgin Suicides (Coppola,

1999) had directly incited episodes of actual

self-harm. Although not explicitly examin-

ing the effect of movies on NSSI, these

findings suggest that the manner in which

NSSI is represented in motion pictures has

the potential to influence how NSSI is

conceptualized, to affect how those who

engage in NSSI are perceived and treated,

and to expose who is most vulnerable to

identifying with and subsequently imitating

representations of NSSI.

As noted above, accurate portrayals of

NSSI may also have a positive therapeutic

utility. Originating in bibliotherapy and

designed to encourage clients to see their

problems from an alternative and more

objective perspective, cinematherapy utilizes

the narrative power of popular motion pic-

tures to facilitate or supplement therapeutic

processes; the logic being that people

sometimes understand themselves better

when they see themselves reflected in the

fictional lives of others (Hesley & Hesley,

2001; Sharp, Smith, & Amykay, 2002). If

a character is shown seeking professional

help for underlying psychiatric concerns

or NSSI, this can be effectively modeled

among those reluctant to seek help. In

those who have sought professional help,

the portrayal of problem resolution and

effective coping may also be modeled. To

date, however, no study has extensively

examined the representation of NSSI in

contemporary motion pictures.

The Current Study

The aims of the current study were: 1.

to explore how NSSI is represented in

modern cinema; 2. to determine if NSSI

is represented as being associated with its

empirically established correlates and func-

tions; and 3. to explore help-seeking among

characters who engage in NSSI.

METHOD

Design and Procedure

Forty-one movies (63.4% drama, 7.3%

action, 2.4% science fiction, 17.1% thriller,

C. Trewavas et al.

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

91

7.3% biography, 2.4% comedy) featuring

scenes of NSSI were identified (see

Appendix A). To build a catalogue of rel-

evant movies, a list of potentially suitable

films was compiled by entering terms

such

as

‘‘self-mutilation,’’

‘‘self-harm,’’

‘‘self-injury,’’ ‘‘self-inflicted injury’’ and

‘‘parasuicide’’ into the IMDB (internet

movie database) and Google search engines,

the results of which were supplemented by

informal discussion with media and enter-

tainment

industry

professionals,

com-

munity members, and academic staff

involved in research on self-injury. In cases

where films known to depict self-injury

were not identified by these methods,

searches for each missing film were con-

ducted separately and the search terms

associated with them re-entered in order

to ensure all appropriate search terms were

used to identify all relevant films. In total,

128 candidate movies were identified, to

which exclusion criteria were subsequently

applied.

Movie genres considered too unrealis-

tic or featuring characters and situations

with which audience members would not

readily identify (i.e., horror, science fiction,

animation) were excluded from the cata-

logue. Exceptions were made, however, in

cases where films depicting fantastic, sur-

real or unrealistic plotlines nevertheless fea-

tured scenes of self-injury that were

realistic in isolation. Gladiator (Franzoni,

2000), for example, features a scene where

the lead character deliberately carves off his

own tattoo in order to disavow his associ-

ation with the Roman military; and The

Abyss

(Cameron, 1989) features a scene

where a naval officer suffering psychosis

deliberately cuts himself.

Consistent with the empirical definition

of NSSI, movies featuring scenes of cultu-

rally sanctioned or socially acceptable forms

of self-injury (e.g., body-piercing, tattooing,

binge-drinking, substance use, smoking)

were excluded from the catalogue. Likewise,

films made prior to 1975 were excluded

from the catalogue, as were non-English

language films, and any films made exclus-

ively for television.

One code sheet, containing 57 vari-

ables, was completed per film, and data

were coded as the film was being watched.

Data included in the coding sheet were

selected based on the functions (e.g.,

physiological

arousal,

emotional

self-

regulation, self-punishment), antecedents

(e.g., post-traumatic adaptation, perceived

threat of loss) and correlates (e.g., problem-

solving deficits, child maltreatment, psy-

chiatric history) of NSSI identified in the

literature. To ensure reliability of coding,

25% of films were dual coded by inde-

pendent raters. Inter-rater reliability was

sound for all variables (Kappa ¼ 0.79).

Character Demographics

. Demographic data

(gender, age, socioeconomic status, occu-

pation, marital status and sexual orien-

tation) were coded for each character

shown to engage in NSSI. Socio-economic

status was measured according to portrayed

living conditions and explicit references to

the character’s standard of living, material

resources and employment status. Age

was coded according to the age at which

characters first engaged in NSSI. However,

since the character’s exact age was often

not explicitly revealed, it was coded into

one of six categories: young adolescent

(13 to 14 years), middle adolescent (15 to

16 years), late adolescent (17 to 19 years),

young adult (20 to 30 years), middle adult

(30 to 45 years), and late adult (45 years

and above).

NSSI Behavior

. In cases where more than

one method of NSSI (e.g., cutting, burning,

etc.) was portrayed, the method most often

shown was recorded. In cases where the

method of NSSI could not be easily classi-

fied (e.g., chewing through body tissue), the

method was coded as ‘‘other.’’ In cases

where more than one character was

depicted engaging in NSSI, the character

NSSI in Motion Pictures

92

VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1 2010

whose NSSI was most explicit or most

frequently depicted was selected. In cases

where NSSI was implied rather than

explicitly

shown,

method

was

coded

according to the information provided

(i.e., visible scarring or explicit reference

to a particular method of self-injury).

Additional data were coded according to

the context in which NSSI occurred (e.g.,

at home, at work, institutional setting,

religious setting). NSSI was considered sen-

sationalized in cases where self-injury was

depicted in a gratuitously graphic, glorified

or melodramatic manner.

Correlates

. As there were often multiple

correlates of NSSI contained in a single

motion picture, predominant themes were

separately coded as primary correlates.

Data related to portrayed psychiatric diag-

nosis were either inferred by implicit refer-

ence in the movie’s script=dialogue to

particular

psychiatric

symptoms

(e.g.,

depressive

symptoms,

dissociation)

or

determined by explicit reference to (or rep-

resentation of) a specific mental disorder

(e.g., BPD, schizophrenia). In cases where

no mental disorder was specified or appar-

ent, the entry was coded as ‘‘none.’’ In

cases where a mental disorder was apparent

but unspecified, the entry was coded as

‘‘unspecified mental disorder.’’

The portrayed relationships shared

between the character depicted engaging

in NSSI and other characters (e.g., family

members, friends, people in immediate

environment) were coded according to

the overall quality of the relationships,

and assessed by observing the reactions

of other characters to NSSI (i.e., supportive

or unsupportive). After coding, a proxy

measure of social support was created by

summating three variables measuring the

quality of the character’s portrayed family

(i.e., relationships with family members)

and social (e.g., relationships with friends,

relationships with people in immediate

environment) relationships on a scale

ranging from 1 ¼ very good, to 4 ¼ very

poor. Since it contained less than 10 items,

the reliability of the social support scale was

tested using mean inter-item correlation,

and found to have sound internal consist-

ency (Briggs & Cheek, 1986): mean

inter-item correlation ¼ .38.

Function of NSSI

. The functions of NSSI

were coded according to the portrayed

antecedents and consequences of NSSI,

and the explicit or implicit reasons provided

for acts of self-injurious behavior (e.g.,

self-punishment was coded in cases where

characters engaged in self-flagellation as a

part of a religious ritual to atone for

perceived sins).

Problem Resolution and Help-Seeking

. The

treatment status of the character was

recorded by noting whether the character

was an inpatient, outpatient, on medication

or in private therapy at the time of the

NSSI. In addition, the help-seeking beha-

vior of the character was recorded, as was

the form of help sought.

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

To determine how NSSI was represented,

preliminary

descriptive

analyses

were

designed to frame a demographic profile

of movie characters depicted as engaging

in NSSI. A total of 41 movie characters

were examined (male ¼ 24, female ¼ 17).

Data were analyzed using a series of chi-

square tests for independence. Assumption

testing was conducted to check for inde-

pendence of observations, sufficient sam-

ple size (n > 20), and minimum expected

cell frequency (n > 5 in 75% of cells). In

cases where small sample size resulted in

violations of the assumption of minimum

expected cell frequency (e.g., ethnicity, liv-

ing environment, sexual orientation), only

C. Trewavas et al.

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

93

descriptive analyses are provided. Dichot-

omous measures of age, occupational sta-

tus, and relationships status were created

in order to permit additional chi-square

analyses.

There was a significant gender differ-

ence for age: v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ 8.33, p ¼ .00,

Cramer’s V ¼ .51, with 4.2% of males and

47.1% of females being depicted as adoles-

cents. There were no significant gender

differences,

however,

for

relationship

status (v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ .00, p > .05), socio-

economic

status

(v

2

(1,

N

¼ 41) ¼ .99,

p >

.05),

living

arrangements

(v

2

(1,

N

¼ 41) ¼ 3.2, p ¼ .07), or employment sta-

tus (v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ .87, p > .05). As shown

in Table 1, both genders were usually

portrayed as being heterosexual and of

Caucasian ethnicity, and a higher pro-

portion of females depicted engaging in

NSSI were portrayed as living in an urban

environment.

Both

genders

were

more

often

portrayed to use cutting or burning as their

primary methods of NSSI (see Table 2).

Although the percentage of characters

depicted as using cutting as a method of

NSSI did not differ according to gender

(v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ 3.20, p ¼ .07), male char-

acters were depicted engaging in more

NSSI methods than females. The majority

of characters were covert in their practice

of NSSI, and no gender differences were

observed in whether the NSSI was public

or private (v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ .02, p > .05).

Characters were generally shown to self-

injure to the extent that first aid treatment

or medical attention was required, and to

engage in repeated rather than isolated

incidents of NSSI. NSSI was typically

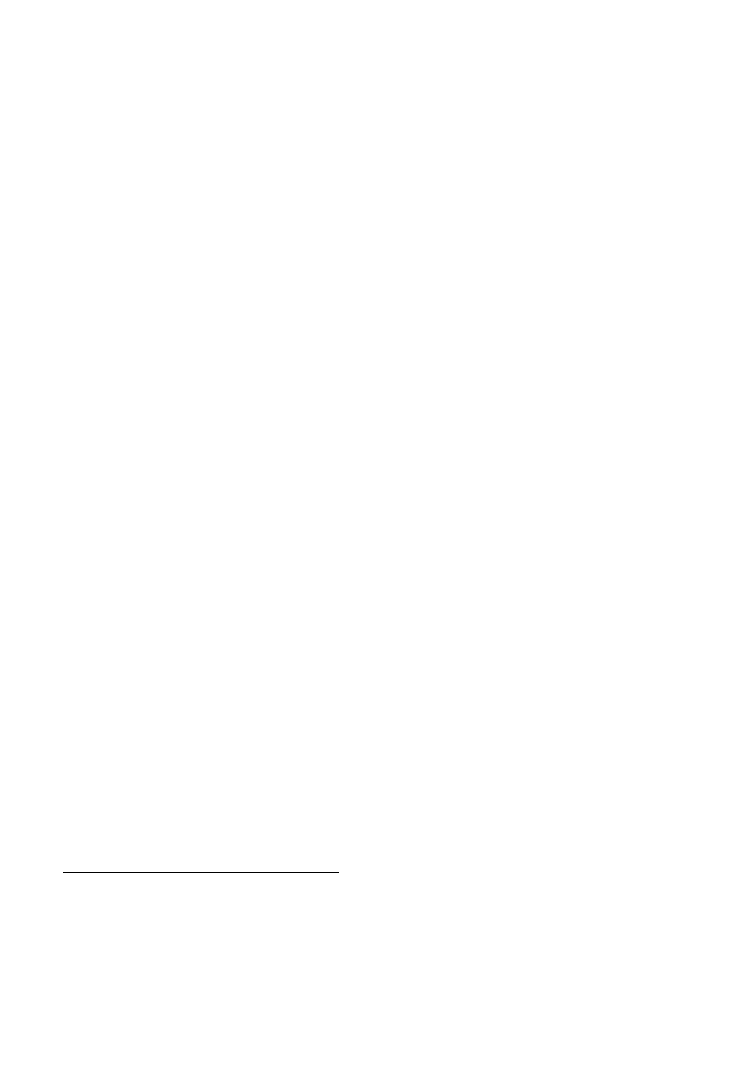

TABLE 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Characters Depicted in Movies Engaging in NSSI

Variable

% Males (n ¼ 24)

% Females (n ¼ 17)

Ethnicity (% Caucasian)

91.7 (n ¼ 22)

88.2 (n ¼ 15)

Age

Young adolescent

0.0

23.5 (n ¼ 4)

Middle adolescent

0.0

11.8 (n ¼ 2)

Late adolescent

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

11.8 (n ¼ 2)

Young adult

45.8 (n ¼ 11)

35.3 (n ¼ 6)

Middle adult

33.3 (n ¼ 8)

17.6 (n ¼ 3)

Late adult

16.7 (n ¼ 4)

0.0

Socioeconomic status (% High)

50.0 (n ¼ 12)

70.6 (n ¼ 12)

Occupational status

Unemployed

25.0 (n ¼ 6)

11.8 (n ¼ 2)

Student

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

41.2 (n ¼ 7)

Employed

70.8 (n ¼ 17)

47.0 (n ¼ 8)

Martial status

Single

50.0 (n ¼ 12)

52.9 (n ¼ 9)

Boy=girlfriend

29.2 (n ¼ 7)

35.3 (n ¼ 6)

Married

8.3 (n ¼ 2)

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

Sexual orientation (% Heterosexual)

87.5 (n ¼ 21)

88.2 (n ¼ 15)

Environment=setting (% Urban)

83.3 (n ¼ 20)

100.0 (n ¼ 17)

Living arrangements (% lives with other)

50.0 (n ¼ 12)

82.4 (n ¼ 14)

NSSI in Motion Pictures

94

VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1 2010

sensationalized (63.4%, n ¼ 26), in that

depictions were considered gratuitously

graphic, glorified or melodramatic.

Correlates of NSSI

Chi-square analyses were conducted

to investigate which correlates of NSSI

were evenly distributed across age, gender

and socioeconomic status (SES). Several

dichotomous variables were created to

allow for analyses of portrayed NSSI corre-

lates: psychiatric status (mentally ill or not

mentally ill

), maltreatment as a child (mal-

treated

or not maltreated), substance abuse

(abuse or no abuse) socioeconomic status

(SES; high or low); method (cutting or other);

and functions: affect regulation (affect regu-

lation

or

other

),

self-punishment

(self-

punishment

or other). No violations of

chi-square assumptions were noted when

data were categorized in this way.

NSSI was associated with child mal-

treatment (41.5%, n ¼ 17), substance abuse

(68.3%, n ¼ 29), and mental illness (65.9%,

n

¼ 27). Although no significant gender

(v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ 2.49, p > .05) or SES

(v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ 2.48, p > .05) differences

were observed among characters who had

a history of child maltreatment, there was

a significant difference for age, v

2

(1,

N

¼ 41) ¼ 4.49, p ¼ .03), Cramer’s V ¼ .39,

with 77.8% (n ¼ 7) of adolescents and

31.2% (n ¼ 10) of adults being portrayed

as having experienced child abuse. No

significant gender (v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ .54,

p >

.05), SES (v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ .01, p >

.05), or age (v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ .00, p > .05)

differences were observed among those

portrayed as having substance abuse issues.

Likewise, the percentage of characters

depicted as being mentally ill did not signifi-

cantly differ according to their gender, v

2

(1,

N

¼ 41) ¼ 0.00, p > .05, or portrayed age,

v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ 1.28, p ¼ .26. However,

significant differences were observed for

the relationship between portrayed psychi-

atric status and SES: v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ 7.87,

p

¼ .01, Cramer’s V ¼ .44, with 41.18%

(n ¼ 7) of characters of low SES and

83.33% (n ¼ 20) of characters of high SES

portrayed as having a mental illness.

The frequencies of specific psychiatric

diagnoses associated with NSSI according

to character gender and are presented in

Table 3. Overall, both genders were more

often portrayed as having some form of

mental disorder than none at all. However,

although both genders were portrayed as

having similar rates of psychosis, comorbid-

ity, mood and substance use disorders, no

female characters were portrayed as being

affected by post traumatic stress disorder,

anxiety disorder, or antisocial personality

disorder; and no male characters were

portrayed as being affected by an eating

disorder. Additionally, neither male nor

female characters were portrayed as having

borderline personality disorder. Although

portrayals of NSSI were more often

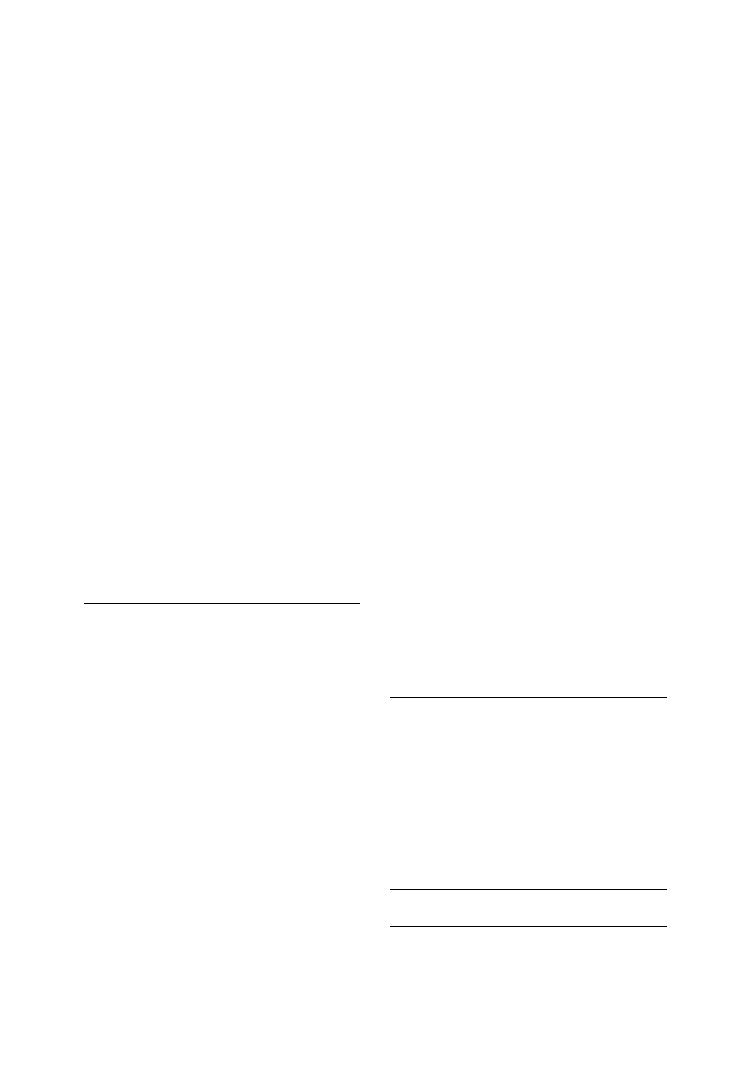

TABLE 2.

NSSI as Depicted in Motion Pictures

Variable

% Males

(n ¼ 24)

% Females

(n ¼ 17)

Type of NSSI

Cutting

45.8 (n ¼ 11)

76.5 (n ¼ 13)

Burning

25.0 (n ¼ 6)

11.8 (n ¼ 2)

Self-flagellation

8.3 (n ¼ 2)

0.0

Extreme risk-taking

8.3 (n ¼ 2)

0.0

Skin picking

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

0.0

Self-mutilation

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

Self-hitting

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

Severity of NSSI

Superficial

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

Home first aid

50.0 (n ¼ 12)

52.9 (n ¼ 9)

Medical attention

41.7 (n ¼ 10)

29.4 (n ¼ 5)

Life-threatening

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

11.8 (n ¼ 2)

Frequency of NSSI

Isolated incident

50.0 (n ¼ 12)

23.5 (n ¼ 4)

Repeated NSSI

50.0 (n ¼ 12)

76.5 (n ¼ 13)

Concealment of NSSI

Overt=public

33.3 (n ¼ 8)

35.3 (n ¼ 6)

Cover=private

66.7 (n ¼ 16)

64.7 (n ¼ 11)

C. Trewavas et al.

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

95

associated with suicidal ideation, characters

depicted as engaging in NSSI were not

usually shown to commit (19.5%, n ¼ 8)

or

attempt

(29.3%,

n

¼ 12)

suicide.

Although characters depicted as engaging

in NSSI were more often main characters

(68.3%),

more

supporting

characters

(46.2%) than main characters (7.1%) were

portrayed

committing

suicide

v

2

(1,

N

¼ 41) ¼ 6.29, p ¼ .01, with a moderate

association

between

these

variables:

Cramer’s V ¼ .46.

The social support scale (range ¼ 3

to 12; M ¼ 7.14, SD ¼ 1.84) was analyzed

for differences in relevant demographic

variables and correlates. However, no

significant differences were found in scores

on the social support scale for portrayed

gender, age, ethnicity, socio-economic sta-

tus, psychiatric status, suicidal ideation, or

privacy of NSSI (all p > .05).

Function of NSSI

The primary motives of NSSI were

portrayed

as

affect

regulation

and

self-punishment (see Table 3). There were

no gender (v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ 1.0, p > .05),

age (v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ .89, p > .05), or SES

(v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ 3.0, p > .05) differences

observed for self-punishment. Likewise,

the proportion of characters depicted as

engaging in NSSI for the purpose of

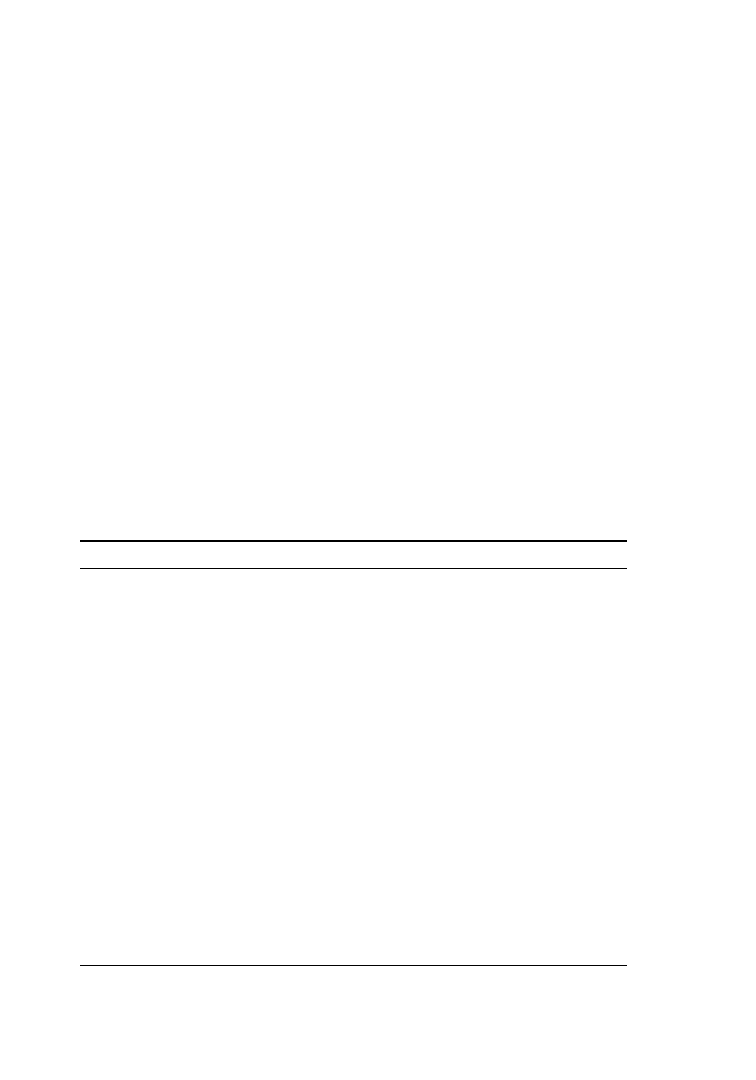

TABLE 3.

Correlates and Functions of NSSI

Variable

% Males (n ¼ 24)

% Females (n ¼ 17)

Correlates

Child maltreatment

29.2 (n ¼ 7)

58.8 (n ¼ 10)

Substance abuse

62.5 (n ¼ 15)

76.5 (n ¼ 13)

Mental illness

62.5 (n ¼ 15)

64.7 (n ¼ 11)

Anxiety disorder

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

0.0

Mood disorder

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

Psychosis

8.3 (n ¼ 2)

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

Anti-social personality

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

0.0

Dissociation

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

11.8 (n ¼ 2)

Eating disorder

0.0

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

Substance dependence

8.3 (n ¼ 2)

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

PTSD

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

0.0

Co-morbid conditions

8.3 (n ¼ 2)

11.8 (n ¼ 2)

Unspecified

16.7 (n ¼ 4)

17.6 (n ¼ 3)

Functions

Affect regulation

12.5 (n ¼ 3)

41.2 (n ¼ 7)

Self-punishment

33.3 (n ¼ 8)

17.6 (n ¼ 3)

Attention

8.3 (n ¼ 2)

11.8 (n ¼ 2)

Rite of passage

8.3 (n ¼ 2)

0.0

Social acceptance

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

0.0

Social communication

16.7 (n ¼ 4)

17.6 (n ¼ 3)

Manipulation of others

12.5 (n ¼ 3)

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

Escape unreality

0.0

5.9 (n ¼ 1)

Other

4.2 (n ¼ 1)

0.0

NSSI in Motion Pictures

96

VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1 2010

affect regulation did not differ according to

age (v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ .76, p > .05) or SES

(v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ .76, p > .05). However,

NSSI was more often portrayed as a mode

of affect regulation for females than

for males, v

2

(1, N ¼ 41) ¼ 6.10, p ¼ .01,

Cramer’s V ¼ .44.

Help-Seeking

The majority of characters were not in

any form of psychiatric treatment at the

time of NSSI (63.4%, n ¼ 26), however

many voluntarily sought support after the

NSSI

episode

(26.8%,

n ¼ 11).

An

additional 17.1% (n ¼ 7) were provided

help involuntarily, while no form of sup-

port was obtained by 31.7% (n ¼ 13) of

characters. Professional help was most

often obtained from psychiatrists (22.0%,

n ¼ 9), while friends or family were also

common sources of support (21.9%,

n ¼ 8). Family reactions to the character’s

NSSI were often not portrayed, although

31.7% (n ¼ 13) reacted in a positive and

supportive manner. The reaction of friends

was more often depicted. 46.3% (n ¼ 19)

were shown to be positive and supportive

of the character, while 19.5% (n ¼ 8) were

shown to be indifferent or unsupportive

of the character.

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to examine how NSSI is

depicted in motion pictures with a view

to determining whether the representations

are accurate in terms of the nature, corre-

lates and functions of NSSI. In addition,

problem resolution was explored by exam-

ining

help-seeking

among

characters.

Results indicated that NSSI was generally

sensationalized, featured prominently, and

depicted as covert, severe, and habitual.

Yet, overall, depictions of NSSI in motion

pictures were relatively consistent with

current literature on actual NSSI, although

important differences were also apparent.

Accuracy in Portrayal of NSSI

Movie characters depicted as engaging

in NSSI were typically male, Caucasian,

single, heterosexual, working adults of rela-

tively high socioeconomic status. Represen-

tations of women engaging in NSSI

conformed to a narrower pattern than for

that of men (i.e., women were depicted as

engaging in fewer methods of self-injury

and in association with fewer correlates).

This representation of NSSI in motion pic-

tures is partially consistent with research

findings on actual NSSI. Although some

research suggests that NSSI is more com-

mon in females (e.g., DeLeo & Heller,

2004), other reports suggest the gender dif-

ference may be relatively small, especially

when a range of NSSI behaviors (e.g.,

burning, hitting oneself) are assessed (e.g.,

Gratz, Conrad & Roemer, 2002; Hasking,

Momeni, Swannell et al., 2008). Further,

the fact that more films portrayed men

engaging in NSSI is not necessarily a reflec-

tion on the gender balance in the com-

munity, but rather an imbalance in what

the movie makers wish to portray. The

same is true of the over-representation of

people with high socio-economic status

classified as mentally ill or as engaging in

NSSI. Although recent reports suggest a

high incidence of NSSI among people of

high socio-economic status (Yates, Tracey,

&

Luthar,

2008),

usually

an

inverse

relationship is reported (e.g., Gratz, Con-

rad, & Roemer, 2006; Lipschitz, Winegar,

Nicolaou et al., 1999; Nada-raja, Skegg,

Langley et al., 2004; Whitlock, Eckenrode,

& Silverman, 2006).

As reflected in the findings on actual

NSSI

reported

by

Hilt,

Cha

and

Nolen-Hoeksema (2008), women were

portrayed as engaging in NSSI in order to

regulate their emotions. Consistent with

C. Trewavas et al.

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

97

some research findings (Klonsky, 2007;

Nixon, Cloutier & Jansson, 2008), cutting

was

the

most

frequently

represented

method of NSSI. However, burning was

more often represented in motion pictures

than is evidently reported in the literature,

while other types of NSSI commonly

reported,

such

as

severe

scratching

(Hasking, Momeni, Swannell et al., 2008;

Yates, 2004) were least often represented.

It is not clear why the portrayal of

women was narrower than that of men,

however demographic representations of

NSSI are dependent on the plot and charac-

ters revealed on screen. Although there was

no significant relationship between genre of

movie and gender of the character, story

lines involving women who engage in NSSI

tend to center on issues of psychological

distress and trauma (e.g., Girl Interrupted).

In such films, the stereotype of young

women who cut themselves for affect regu-

lation is readily apparent. Conversely, films

depicting men who engage in NSSI were

more likely to portray a broader range of

plot lines and thus a more diverse depiction

of NSSI. Although speculative, this might

explain the narrower range of NSSI

depicted for female characters.

Representations of NSSI were associa-

ted with correlates of NSSI identified

throughout the literature: affect regulation

(Hilt, Cha & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008;

Nock, Holmberg, Photos et al., 2007),

mental illness (Welch, Linehan, Sylvers

et al., 2008), substance abuse (Nock,

Holmberg, Photos et al., 2007), and child

maltreatment (Glassman, Weierich, Hooley

et

al.,

2007;

Gratz,

2006;

Lipschitz,

Winegar, Nocolaou et al., 1999; Weierich

& Nock, 2008). Interestingly, however,

despite their frequent association in the

literature

(Dellinger-Ness

&

Handler,

2006; Welch, Linehan, Sylvers et al., 2008;

Yates, 2004), NSSI was not correlated with

borderline personality disorder. However,

this may reflect that pop culture does not

engage deeply in psychiatric language,

rather than indicating a lack of diagnosis.

Consistent with the findings of Hasking,

Momeni, Swsannell et al. (2008), Nock

and Mendes (2008), and Yates (2004),

NSSI was depicted as helpful in reducing

negative affective states.

As few as 30% of young people who

self-harm seek professional psychiatric help

(DeLeo & Heller, 2004). Since professional

help-seeking is more likely among those

who self-poison than those who engage

in other forms of self-injury (Hawton,

Rodham, Evans et al., 2009), it is likely that

even fewer who engage in NSSI seek pro-

fessional help. Similarly, movie characters

were rarely in psychiatric care at the time

of self-injury. However in contrast to what

we know about help-seeking in the com-

munity, many of the movie characters

received support after NSSI. Approxi-

mately one quarter of the sample obtained

professional psychiatric care, however fam-

ily and friends were also approached for

support. These findings suggest that movie

depictions of NSSI may be useful in a

therapeutic context. Modeling of help-

seeking behavior may assist in effective

problem-resolution for young people in

the community or in clinical settings. How-

ever the reliance on family and friends also

mirrors reports that young people prefer to

seek informal support from friends (Evans,

Hawton & Rodham, 2005). Arguably,

accurate movie portrayals of NSSI may be

useful in education and training of the

wider community, who are more likely to

encounter someone who engages in NSSI.

It is unclear why the portrayals of

NSSI were relatively accurate when por-

trayals of suicide and suicidal behavior tend

to be inaccurate (Pirkis & Blood, 2001).

One possible explanation is that portrayals

of NSSI in motion pictures appear to be a

relatively recent phenomena, with the

majority of movies reviewed in this study

(43.9%) released after 2000. In recent dec-

ades efforts have been made to increase the

accuracy and sensitivity with which suicide

NSSI in Motion Pictures

98

VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1 2010

is reported in media. These efforts may

have generalized to portrayal of NSSI.

However, although the depiction of

NSSI generally matched the existing litera-

ture on correlates of NSSI, the portrayals in

motion pictures were more likely to be

linked to suicide attempts and completed

suicide than is the case in the literature.

NSSI in the movies was less likely to be

related to suicide than other psychological

correlates, but with 19.5% of movie charac-

ters

committing

suicide

and

29.3%

attempting suicide an association between

NSSI and suicide is made clear in the

motion pictures. Few prospective studies

have examined suicide among those who

have self-injured. Those that have suggest

between 5–7% of people who self-injure

will suicide within 9–10 years of the NSSI

(DeMoore & Robertson, 1996; Owens,

Horrocks & House, 2002), a figure much

lower than portrayed in the motion

pictures. This link portrayed in motion pic-

tures may influence opinions of the viewing

public and foster the myth that NSSI is

always a suicidal act. De-bunking such

myths is important in providing effective

and timely care to those who self-injure

and in fostering self-confidence among

those who work in schools and emergency

departments, who often report fear and

uncertainty when faced with a person

who engages in NSSI (Huband & Tantam,

2000; McAllister, Creedy, Moyle et al.,

2002). More accurate portrayal of the

relationship between NSSI and suicide in

motion pictures may be one way to better

educate the viewing public about this

relationship.

Implications

The accuracy of movie representations

of NSSI may be helpful in challenging

stigma, however, the more accurately NSSI

is portrayed, the greater its potential impact

on actual self-injurious behavior. Since

viewers are more likely to internalize and

subsequently imitate realistic or non-

fictional

media

imagery

(Stack,

2003,

2005), accurate portrayals of NSSI, in the

absence of positive problem resolution,

may

increase

the

risk

of

imitative

self-injurious behavior. Adding to the

increased risk of imitative self-injurious

behavior, NSSI was typically sensationa-

lized, featured prominently, depicted as

severe, and repeatedly portrayed as a ritual

coping mechanism. This is concerning

because imitative acts of NSSI are more

likely depending on how prominently acts

of self-injury are featured, particularly in

cases

where

NSSI

is

sensationalized.

Additionally, a dose-response effect for

imitative NSSI is more likely when acts of

self-injury are shown more often and, since

the risk of suicide contagion is increased in

cases where suicide method is explicitly

described (Martin, 1998), the explicit por-

trayal of severe NSSI may likewise increase

the risk of imitative acts of NSSI. More-

over, motion pictures feature celebrities

engaging in fictional acts of NSSI, arguably

a variation of a risk factor for the ‘‘Werther

effect’’ reported by Stack (2003, 2005).

These findings underscore the need for

the sensitive and responsible portrayal of

self-injurious behavior in motion pictures.

The often sensationalized portrayal of

severe NSSI in films, and the frequently

depicted strong association of NSSI with

mental illness and suicide, may stigmatize

people who engage in self-injury, reducing

the likelihood that they actively seek or

willingly engage assistance (Wedding &

Niemiec, 2003).

The current study has important impli-

cations for the treatment of NSSI. As an

auxiliary therapeutic medium, motion pic-

tures have the potential to deliver a sense

of connection with the stories of others,

to foster empathy and self-awareness, to

encourage novel perspectives, to facilitate

therapeutic discussion, and to reduce the

subjective perception of social isolation

C. Trewavas et al.

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

99

(Hesley & Hesley, 2001; Schulenberg,

2003). Films that feature NSSI could be

even more powerful if they included a dis-

course of hope and recovery. The films

accurately portrayed that the majority of

people who engage in NSSI do not seek

professional help, and that family and

friends are often the only source of support

(Evans, Hawton & Rodham, 2005). Such

films may also help to reduce stigma asso-

ciated with NSSI, remove the guilt that is

often associated with repeated NSSI, and

could improve clinicians’ willingness and

ability to care for those who self-injure.

Limitations and Suggestions

for Future Research

The current study was limited by some

methodological weaknesses. First, cultural

bias reduces the generalizability of these

findings. The catalogue of selected movies

was limited to English language films made

after 1975, most of which were produced

in the United States—perhaps indicating a

relatively recent recognition of NSSI in

mainstream American. A larger sample

taken from a more linguistically and cultu-

rally heterogeneous range of films may

have revealed cultural differences in por-

trayals of NSSI, and yielded results more

representative of global trends in portrayals

of NSSI. Furthermore, since people are

often exposed to multiple forms of media,

the inclusion of a broader range of media

(internet, television, print, radio) would also

enable a comparison of NSSI depictions

across different media types.

It is also worth noting that motion

pictures cannot convey all relevant infor-

mation about a character. Specifically, fail-

ure to disclose diagnoses or treatment

history does not necessarily suggest that the

character was not imagined by the writers to

have a psychiatric or treatment history.

Consequently in viewing and reviewing

films it is important to acknowledge that

the data available for analysis are selected

by the writers and film makers. It would

be interesting in future to interview film

makers to ascertain their views on NSSI

and how it is portrayed in popular media,

as well as steps they make take in consider-

ing how to portray such behavior accurately

and sensitively.

Further studies into representations of

NSSI are needed in order to explore their

impact on viewers, and to investigate their

potential to reduce stigma. Although we

found that many of these films accurately

depict NSSI and that this may induce con-

tagion, there is as yet no evidence for this.

Indeed, it may be that plot devices within

the films actually reduce stigma and

enhance coping capacity. A study in which

participants view such films and record

their attitudes and beliefs before and after

viewing would be valuable. In addition,

examination of the use of cinematherapy

in treating people who engage in NSSI

would be a valuable step in improving the

care given to people who self-injure.

In summary, it appears that depictions

of NSSI in motion pictures are generally

accurate with respect to the correlates and

functions of NSSI often reported in the

literature. However links to suicide, and

the sensationalist presentation of NSSI

may have an adverse effect on some audi-

ence members. Accurate representation of

NSSI in motion pictures may increase the

likelihood of identification and imitation

of such acts, but may also offer a useful

mechanism for reducing stigma and model-

ing help-seeking behaviors.

AUTHOR NOTE

Special thanks are extended to Professor

Steven Stack, whose insightful suggestions

were helpful in determining coding para-

meters, and whose considerable experience

in the area of suicide research proved a

highly relevant and practical resource.

NSSI in Motion Pictures

100

VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1 2010

Christopher Trewavas and Penelope

Hasking, School of Psychology, Psychiatry

and Psychological Medicine, Monash Uni-

versity, Victoria, Australia.

Margaret McAllister, School of Health

and Sport Sciences, Faculty of Science,

Health and Education, University of the

Sunshine Coast, Maroochydore, Queens-

land, Australia.

Correspondence concerning this article

should be addressed to Penelope Hasking,

School of Psychology, Psychiatry and

Psychological Medicine, Monash Univer-

sity, Caulfield East VIC, 3145, Australia.

E-mail:

Penelope.Hasking@med.mona-

sh.edu.au

REFERENCES

Armey, M. F., & Crowther, J. H. (2008). A compari-

son of linear versus non-linear models of aversive

self-awareness, dissociation, and non-suicidal self-

injury among young adults. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology

, 76, 9–14.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and

action: A social cognitive theory

. Englewood Cliffs,

NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bollen, K. A., & Phillips, D. P. (1982). Imitative sui-

cides: A national study of the effects of television

news stories. American Sociological Review, 47, 802–809.

Briggs, S. R., & Cheek, J. M. (1986). The role of

factor analysis in the development and evaluation

of personality scales. Journal of Personality, 54,

106–148.

Cameron, J. (Writer) (1989). The Abyss. In R. Weiss

(Producer). United States: Twentieth Century-Fox

Film Corporation.

Coppola, S. (Writer) (1999). The Virgin Suicides. In F.

Fuchs (Producer). United States: Paramount

Pictures.

Crowell, S. E., Beauchaine, T. P., McCauley, E. et al.

(2008). Parent-child interactions, peripheral sero-

tonin, and self-inflicted injury in adolescents. Jour-

nal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

, 76, 15–21.

De Leo, D., & Heller, T. S. (2004). Who are the kids

who self-harm? An Australian self-report school

survey. Medical Journal of Australia, 181, 140–144.

Dellinger-Ness, L. A., & Handler, L. (2006).

Self-injurious behaviour in human and non-

human primates. Clinical Psychology Review, 26,

503–514.

DeMoore, G. M., & Robertson, A. R. (1996). Suicide

in the 18 years after deliberate self-harm: A pro-

spective study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 169,

489–494.

Evans, E., Hawton, K., & Rodham, K. (2005). In

what ways are adolescents who engage in

self-harm or experience thoughts of self-harm dif-

ferent in terms of help-seeking, communication

and coping strategies? Journal of Adolescence, 28,

573–587.

Franzoni, D. (Writer) (2000). Gladiator. In S.

Spielberg (Producer). United States: DreamWorks.

Glassman, L. H., Weierich, M. R., Hooley, J. M. et al.

(2007). Child maltreatment, non-suicidal self-

injury, and the mediating role of self-criticism.

Behaviour Research and Therapy

, 45, 2483–2490.

Gould, M. S., Wallenstein, S., & Davidson, L. (1989).

Suicide clusters: A critical review. Suicide and

Life-Threatening Behavior

, 19, 17–29.

Gratz, K. L. (2006). Risk factors for deliberate

self-harm among female college students: The role

and

interaction

of

childhood

maltreatment,

emotional inexpressivity, and affect intensity=

reactivity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76,

238–250.

Gratz, K. L., Conrad, S. D., & Roemer, L. (2002).

Risk Factors for deliberate self-harm among

college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,

72

, 128–140.

Hasking, P., Momeni, R., Swannell, S. et al. (2008).

The nature and extent of non-suicidal self-injury

in a non-clinical sample of young adults. Archives

of Suicide Research

, 12, 208–218.

Hassan, R. (1995). Effects of newspaper stories on

the incidence of suicide in Australia: A research

note. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry,

29

, 480–483.

Hawton, K., Rodham, K., & Evans, E. (2006). By

their own young hand: Deliberate self-harm and suicidal

ideas in adolescents

. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley

Publishers.

Hawton, K., Rodham, K., Evans, E. et al. (2009).

Adolescents who self harm: A comparison of

those who go to hospital and those who do not.

Child & Adolescent Mental Health

, 14, 24–30.

Hawton, K., Simkin, S., Deeks, J. et al. (1999). Effects

of a drug overdose on a television drama on

presentations to hospital for self-poisoning: Time

C. Trewavas et al.

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

101

series and questionnaire study. British Medical

Journal

, 318, 972–977.

Heath, N., Toste, J. R., Nedecheva, T. et al. (2008).

An examination of nonsuicidal self-injury among

college students. Journal of Mental Health Counseling,

30

, 137–156.

Hesley, J. W., & Hesley, J. G. (2001). Rent two films

and let’s talk in the morning: Using popular movies in

psychotherapy.

(2nd ed.). New York, NY: Wiley.

Hilt, L. M., Cha, C. B., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S.

(2008). Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent

girls: Moderators of the distress function relation-

ship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76,

63–71.

Huband, N., & Tantam, D. (2000). Attitudes to

self-injury within a group of mental health staff.

British Journal of Medical Psychology

, 7, 495–504.

Klonsky, D. E. (2007). The functions of deliberate

self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical

Psychology Review

, 27, 226–239.

Lipschitz, D. S., Winegar, R. K., Nicolaou, A. L. et al.

(1999). Perceived abuse and neglect as risk factors

for suicidal behaviour in adolescent inpatients.

Journal of Nervous and Mental Disorders

, 187, 32–39.

Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., Perrine, N., Dierker, L. et al.

(2007). Characteristics and functions of non-

suicidal self-injury in a community sample of

adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1183–1192.

Mangold, J. (Writer) (2000). Girl Interrupted. In W.

Ryder (Producer). United States: Columbia Pic-

tures.

Martin, G. (1998). Media influence to suicide: The

search for solutions. Archives of Suicide Research, 4,

51–66.

Martin, G., & Koo, L. (1997). Celebrity suicide: Did

the death of Kurt Cobain influence young suicides

in Australia? Archives of Suicide Research, 3, 187–198.

McAllister, M., Creedy, D., Moyle, W. et al. (2002).

Nurses’ attitudes to clients who self-harm. Metho-

dological Issues in Nursing Research

, 40, 578–586.

Motto, J. A. (1970). Newspaper influence on suicide:

A controlled study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 23,

143–148.

Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2006). Empirically supported

treatments and general therapy guidelines for

non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Mental Health

Counseling

, 28, 166–185.

Nada-Raja, S., Skegg, K., Langley, J. et al. (2004).

Self-harmful behaviours in a population-based

sample of young adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening

Behavior

, 34, 177–186.

Nixon, M. K., Cloutier, P., & Jansson, S. M. (2008).

Nonsuicidal self-harm in youth: A population

based survey. Canadian Medical Association Journal,

178

, 306–312.

Nock, M. K. (2009). Why do people hurt them-

selves? New insights into the nature and functions

of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological

Science

, 18, 78–83.

Nock, M. K., Holmberg, E. B., Photos, V. I. et al.

(2007). Self-injurious thoughts and behaviours

interview: Development, reliability and validity in

an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment, 19,

309–317.

Nock, M. K., & Mendes, W. B. (2008). Physiological

arousal, distress tolerance, and social problem-

solving deficits among adolescent self-injurers.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

, 76,

28–38.

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional

approach to the assessment of self-mutilative

behaviour.

Journal

of

Consulting

and

Clinical

Psychology

, 72, 885–890.

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2005). Contextual

features and behavioural functions of self-

mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal

Psychology

, 114, 140–146.

Owens, D., Horrocks, J., & House, A. (2002). Fatal

and non-fatal repetition of self-harm. British Journal

of Psychiatry

, 181, 193–199.

Phillips, D. P. (1974). The influence of suggestion on

suicide: substantive and theoretical implications of

the Werther effect. American Sociological Review, 39,

340–354.

Phillips, D. P. (1985). The Werther effect: Suicide

and other forms of violence are contagious. The

Sciences

, 7, 32–39.

Phillips, D. P., & Carstensen, L. L. (1988). The effect

of suicide stories on various demographic groups,

1968–85. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 18,

100–114.

Pirkis, J., & Blood, R. W. (2001). Suicide and the media:

A critical review

. Canberra: Commonwealth Depart-

ment of Health and Aged Care.

Romer, D., Jamieson, P. E., & Jamieson, K. H.

(2006). Are news reports of suicide contagious?

A stringent test in six U.S. cities. Journal of

Communication

, 56, 253–270.

Ross, S. & Heath, N. (2002). A study of the

frequency of self-mutilation in a community

sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and

Adolescence

, 31, 67–77.

NSSI in Motion Pictures

102

VOLUME 14 NUMBER 1 2010

Schulenberg, S. E. (2003). Psychotherapy and

movies: On using films in clinical practice. Journal

Contemporary Psychotherapy

, 33, 35–48.

Sharp, C., Smith, J. V., & Amykay, C. (2002). Cine-

matherapy: Metaphorically promoting therapuetic

change. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 15, 269–276.

Stack, S. (2003). Media coverage a risk factor in sui-

cide. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health,

57

, 238–240.

Stack, S. (2005). A quantitative review of studies

based

on

nonfictional

stories.

Suicide

and

Life-Threatening Behaviour

, 35, 121–133.

Wedding, D., & Niemiec, R. M. (2003). The clinical

use of films in psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical

Psychology

, 59, 207–215.

Weierich, M. R., & Nock, M. K. (2008). Posttrau-

matic stress symptoms mediate the relation

between childhood sexual abuse and nonsuicidal

self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psy-

chology

, 76, 39–44.

Welch, S. S., Linehan, M. M., Sylvers, P. S. et al.

(2008). Emotional responses to self-injury imagery

among adults with borderline personality disorder.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology

, 76,

45–51.

Whitlock, J. L., Eckenrode, J., & Silverman, D.

(2006). Self-injurious behaviour in a college popu-

lation. Pediatrics, 117, 1939–1948.

Williams, F., & Hasking, P. A. (in press). Emotion

regulation, coping and alcohol use as moderators

in the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury

and psychological distress. Prevention Science.

Yates, T. M. (2004). The developmental psychopath-

ology of self-injurious behaviour: Compensatory

regulation in posttraumatic adaptation. Clinical

Psychology Review

, 24, 35–74.

Yates, T. M., Tracey, A. J., & Luthar, S.S. (2008).

Nonsuicidal self-injury among ‘‘privileged’’ youth:

Longitudinal and cross-sectional approaches to

developmental practices. Journal of Consulting and

Clinical Psychology

, 76, 52–62.

Zahl, D., & Hawton, K. (2004). Media influences on

suicidal behaviour: An interview study of young

people. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 32,

189–198.

APPENDIX. LIST OF MOVIES ANALYZED

True Blue, Gothika, Gun Shy, The Abyss, My

First Mister, 28 Days, The Scarlet Letter, Fear,

The Good Girl, American Beauty, The Virgin

Suicides, Girl Interrupted, Stay, The Return, Stig-

mata, A Beautiful Mind, Control, Cape Fear, 21

Grams, Fatal Attraction, Blue Car, Fight Club,

Sid & Nancy, Gangs of New York, Good Will

Hunting, The Professional, Gladiator, Seven,

Heathers, Thirteen, Romper Stomper, Chopper,

Million Dollar Baby, Taxi Driver, Platoon, Sec-

retary, Prozac Nation, The Da Vinci Code,

Sex: The Annabel Chong Story, Man on Fire,

The Name of the Rose.

C. Trewavas et al.

ARCHIVES OF SUICIDE RESEARCH

103

Copyright of Archives of Suicide Research is the property of Taylor & Francis Ltd and its content may not be

copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written

permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Fraassen; The Representation of Nature in Physics A Reflection On Adolf Grünbaum's Early Writings

REPRESENTATION OF NATURE IN buddhist and western art

Representations of Power in Medieval Germany, 800–1500 review

Representations of the Death Myth in Celtic Literature

Mitchell Ut Pictura Theoria Abstract Painting and Repression of Language

Dracula s Women The Representation of Female Characters in a Nineteenth Century Novel and a Twentie

NSSI in Young Adolescent Girls Moderators of the Distress Function Relationship

Developing a screening instrument and at risk profile of NSSI behaviour in college women and men

Fixing Lolita Reevaluating the Problem of Desire in Representation

Han, Z H & Odlin, T Studies of Fossilization in Second Language Acquisition

Jacobsson G A Rare Variant of the Name of Smolensk in Old Russian 1964

Chirurgia wyk. 8, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Australia, Od Aśki, [rat 2 pos

Nadczynno i niezynno kory nadnerczy, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Austral

5 03 14, Plitcl cltrl scial cntxts of Rnssnce in England

Guide to the properties and uses of detergents in biology and biochemistry

Newell, Shanks On the Role of Recognition in Decision Making

Harmonogram ćw. i wyk, In Search of Sunrise 1 - 9, In Search of Sunrise 10 Australia, Od Aśki, [rat

więcej podobnych podstron