SPINE Volume 27, Number 8, pp E207–E214

©2002, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc.

Interexaminer Reliability of Low Back Pain Assessment

Using the McKenzie Method

Sinikka Kilpikoski, MSc,* Olavi Airaksinen, MD, DmedSci,†

Markku Kankaanpa¨a¨, MD, DmedSci,†‡ Pa¨ivi Leminen, PT,*

Tapio Videman, MD, DmedSci,

§ and Markku Alen, MD, DmedSci*†

Study Design. A test–retest design was used.

Objective. To assess interexaminer reliability of the

McKenzie method for performing clinical tests and clas-

sifying patients with low back pain.

Summary of Background Data. Clinical methods and

tests classifying patients with nonspecific low back pain

have been based mainly on symptom duration or ex-

tent of pain referral. The McKenzie mechanical diagnos-

tic and classification approach is a widely used nonin-

vasive, low-technology method of assessing patients

with low back pain. However, little is known about the

interexaminer reliability of the method, previous stud-

ies having yielded conflicting results.

Methods. For this study, 39 volunteers with low back

pain, mean age 40 years (range, 24 –55 years), were

blindly assessed by two physical therapists trained in the

McKenzie method. The variability of two examiners for

binary decisions was expressed by the kappa coefficient,

and by the proportion of observed agreement, as calcu-

lated from a 2

⫻ 2 contingency table of concordance.

Results. On the basis of pure observation alone,

agreement among clinical tests on the presence and

direction of lateral shift was 77% (

⫽ 0.2; P ⬍ 0.248)

and 79% (

⫽ 0.4; P ⬍ 0.003), respectively. Agreement

on the relevance of lateral shift and the lateral compo-

nent according to symptom responses was 85% (

⫽

0.7; P

⬍ 0.000) and 92% (

⫽ 0.4; P ⬍ 0.021), respec-

tively. Using the repeated movements and static end-

range loading strategy to define the centralization phe-

nomenon and directional preference, agreement was

95% (

⫽ 0.7; P ⬍ 0.002) and 90% ( ⫽ 0.9; P ⬍ 0.000),

respectively. When patients with low back pain were clas-

sified into the McKenzie main syndromes and into specific

subgroups, agreement was 95% (

⫽ 0.6; P ⬍ 0.000) and

74% (

⫽ 0.7; P ⬍ 0.000), respectively.

Conclusions. Interexaminer reliability of the McKen-

zie lumbar spine assessment in performing clinical

tests and classifying patients with low back pain into

syndromes were good and statistically significant when

the examiners had been trained in the McKenzie method.

[Key words: agreement, classification, low back pain as-

sessment, McKenzie method, reliability] Spine 2002;27:

E207–E214

The origin of low back pain (LBP) remains unknown in

most cases. Even after careful clinical assessment and

specific measurements, the precise cause of the symptoms

may be identified in only 15% of cases.

24

Previous clas-

sifications used to subgroup these patients with “nonspe-

cific” LBP have mainly been based on symptom duration

or extent of pain referral.

24

This has been a major weak-

ness in etiologic research, and also in preventive and

treatment interventions.

Good interexaminer reliability is crucial for any clas-

sification of patients with LBP. Tests that could identify

etiopathogenetically separate subgroups would assist re-

lated research. It has also been suggested that patients

with LBP who undergo specific management based on an

assigned classification do better than patients whose

treatment is not based on their pretreatment classifica-

tion.

20,24

Therefore, the use of physical signs and symp-

tom behavior as criteria for classifications of LBP is an

important and promising area in clinical decision making

and trials.

3,5,11,14 –17,20,24

The McKenzie mechanical diagnostic and classifica-

tion approach is a noninvasive, low-technology, inex-

pensive method of assessing patients with LBP that uses

physical signs, symptom behavior, and their relation to

end-range lumbar test movements to determine appro-

priate classification and treatment (Table 1, Appendix

1). The McKenzie method classifies mechanical LBP into

three main syndromes: postural, dysfunction, and de-

rangement (Appendix 1).

15–17

Interexaminer reliability of the McKenzie approach in

performing clinical tests and classifying patients with

LBP into syndromes has been previously investi-

gated.

4 –7,9,13,18,19,23,25,26

Kilby et al

13

suggested that the

“McKenzie algorithm” is reliable in the examination of

pain behavior and pain response with repeated move-

ments, but unreliable in the detection of end-range pain

and lateral shift. Riddle and Rothstein

23

found that the

McKenzie approach was unreliable when physical ther-

apists classified patients into McKenzie syndromes. They

suggested that a potential source of unreliability was in

determining whether the patient had a lateral shift and, if

so, in which direction, and whether the patient’s pain

centralized or peripheralized during test movements.

23

From the *Department of Health Sciences, University of Jyva¨skyla¨,

Jyva¨skyla¨, Finland, the †Department of Physical Medicine and Reha-

bilitation, Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland, the ‡Univer-

sity of Kuopio, Department of Physiology, Kuopio, Finland, and the

§Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton,

Canada.

Supported by the McKenzie Institute, Robhauptery, Germany.

Acknowledgment date: March 8, 2001.

First revision date: June 18, 2001.

Second revision date: September 12, 2001.

Acceptance date: November 6, 2001.

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical

devices.

No funds were received in support of this study.

E207

However, in a previous study,

18

interexaminer reliability

between two therapists trained in the McKenzie method

seemed to be high for classifying patients with LBP into

McKenzie syndromes, and excellent for judging pain sta-

tus change, including the centralization phenomenon,

during examination of the lumbar spine.

9,18,19

Donahue et al

4

found that the McKenzie method was

unreliable for detecting the presence of a lateral shift, but

that a relevant lateral component could be reliably de-

tected using symptom response to repeated movements.

On the other hand, Tenhula et al

25

showed a significant

relation between positive results on a contralateral side-

bending movement test and a lumbar lateral shift, indi-

cating that the former is a useful clinical test for confirm-

ing the presence of a lateral shift in patients with LBP.

The obvious discrepancies among earlier studies on

agreement and reliability of the McKenzie method

prompted this study.

This study aimed to assess the interexaminer agree-

ment among physical therapists trained in the McKenzie

method as they performed clinical tests and classified

patients with LBP. The specific aims of the study were to

test interexaminer reliability 1) in determining the pres-

ence and direction of lateral shift by using pure observa-

tion alone, the relevance of lateral shift and the lateral

component as noted by symptom responses to repeated

movement, and the centralization phenomenon and di-

rectional preference in relation to the repeated move-

ment end-range test pattern, and 2) in classifying patients

with LBP into the main McKenzie syndromes and their

specific subgroups (Table 1, Appendix 1).

Methods

Participants.

For this study, 39 volunteers with LBP, mean age

40 years (range, 24 –55 years), with or without radiation to the

lower limb, randomly drawn from a randomized ongoing

wider study

12

at Kuopio University Hospital, participated in

this study (Table 2). Participants were recruited through the

Kuopio Occupational Health Center (Kuopio, Finland), where

they had sought medical attention for LBP. The participants

had experienced chronic low back disorder with symptom du-

ration longer than 3 months and moderate functional disability

that enabled them to work with only occasional absences. In

the initial clinical examination at the health center, the cause of

the back pain was confirmed to be nonspecific. Patients with

radicular symptoms (radiating pain below the knee, loss of

sensation, muscle dysfunction, or loss of reflexes), disc pro-

lapse, severe scoliosis, spondyloarthrosis, previous back sur-

gery, and other specific and serious causes of back pain were

excluded from the study.

12

Examiners.

The examiners, two physical therapists, possessed

a high level of training, averaging 5 years of clinical experience

in the McKenzie method. They were diploma and examination

credential holders in spine mechanical diagnosis and therapy.

Table 1. Definitions and Operational Terms of the McKenzie Method

Presence and direction of lateral shift

“Lateral displacement or deviation of the trunk, in relation to the pelvis in the frontal plane, viewed from

behind (C7–S1), while the patient is in the standing position. If the trunk is shifted to the right, relative

to the pelvis, this is a right shift.

16,18

Deformity

“Deformity may be a feature of some acute derangements (Appendix 1). The patient has a sudden loss of

movement that corresponds to the onset of pain. This loss of movement is severe enough to cause the

patient to be unable to actively move out of that abnormal posture. Depending on the direction of the

blockage of the movement, patients may present with the deformity of kyphosis (unable to straighten

up), deformity of increased lordosis (unable to bend forward), or lateral shift (unable to cross the

midline in frontal plane). A deformity is relevant only when attempted correction influences the

symptoms.”

5,18

Relevance of lateral shift

“A shift that is related to the patient’s present symptoms, ie, patient’s symptoms centralize to the lumbar

spine while attempt is made to correct the deformity of the lateral shift.”

16,18

Relevant lateral component

“This term is used for patients with unilateral or asymmetrical symptoms who do not centralize by

movements in sagittal plane. Centralization can only be achieved with asymmetrical lateral movements

such as side-glides or rotations. If symptoms can be resolved simply by performing extension in the

sagittal plane, the lateral component is considered to be insignificant.”

16,18

Centralization phenomenon

“Describes the phenomenon by which distal limb pain emanating from, though not necessarily felt in

spine, is immediately or eventually abolished in response to the deliberate application of loading

strategies. Such loading causes a decrease or abolition of peripheral pain which appears to

progressively retreat in a proximal direction. As this occurs there may be a simultaneous development

or increase in proximal symptoms. The phenomenon occurs only in derangement syndrome (Appendix

1).”

6,7,9,15–17,26

Directional preference

“Used to describe the phenomenon of preference for movement in one direction, which is a characteristic

of the derangement syndrome (Appendix 1). It describes the situation when movements in one direction

will improve pain and the limitation of range, whereas movements in the opposite direction cause signs

and symptoms to worsen.”

6,7,15–17

Table 2. Characteristics of Subjects

Mean (Range)

No. (%) of Study

Participants

Gender

Women

15 (38)

Men

24 (62)

Age (yr)

40 (24–55)

Symptom duration, yr

14 (1–38)

Symptoms at study entry

Symptom free

2 (5)

Acute:

⬍7 days

5

(13)

Subacute:

⬎7 days ⬍7 weeks

9 (23)

Chronic:

⬎7 weeks

23 (59)

No. of previous episodes

1–5

16 (41)

6–10

7 (18)

⬎10

16 (41)

E208 Spine

•

Volume 27

•

Number 8

•

2002

Procedure.

After receiving an oral and written explanation of

what would be required of them, the participants all signed an

informed consent.

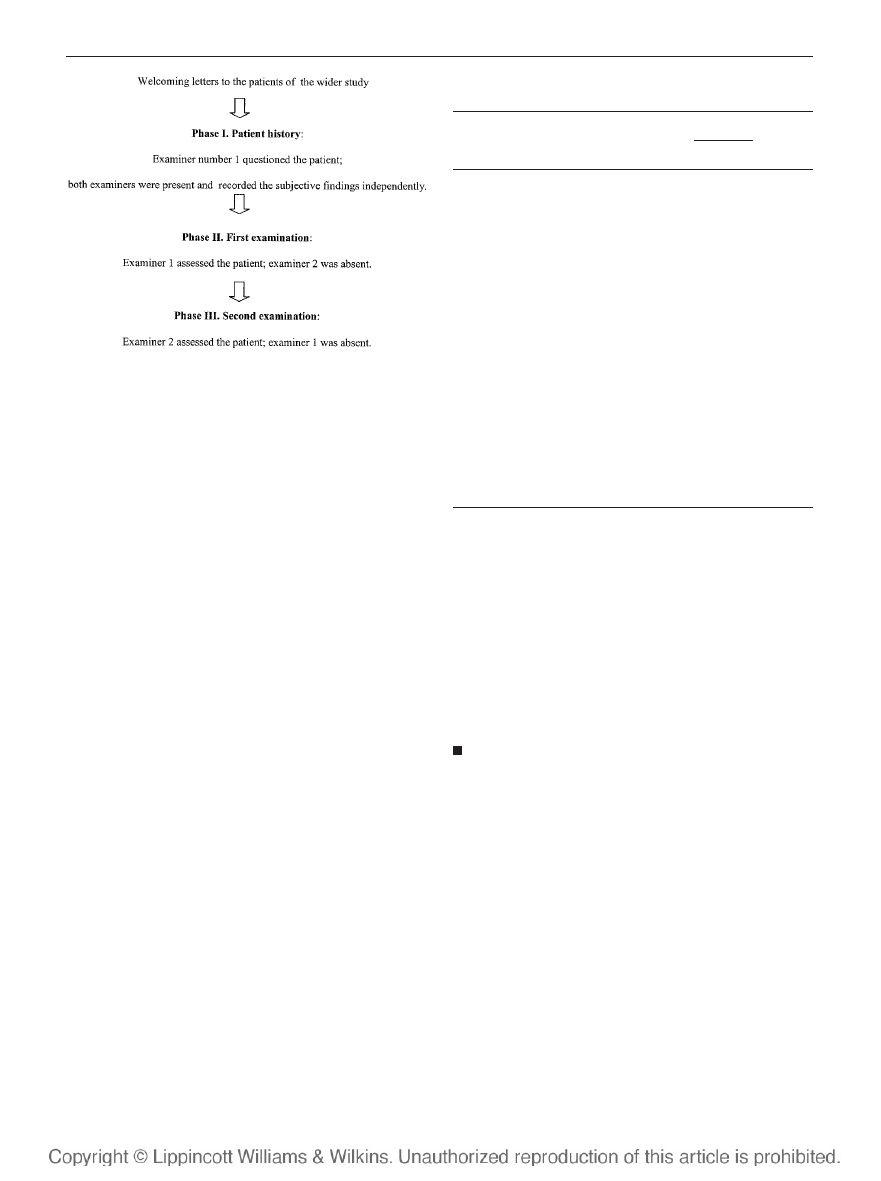

The clinical assessment procedure is shown in Figure 1. In

brief, before entering the current study, the patients with LBP

were assessed medically, first by a general practitioner, and

second by a specialist in physical and rehabilitation medicine.

Patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria were randomly selected

to participate in this clinical assessment.

12

The participants

were examined independently by two physical therapists in

succession (the duration of an assessment session was approx-

imately 1

1

⁄

2

hours). The examiners were randomly assigned to

be examiner number 1 and examiner number 2 so that each

was examiner number 1 in 50% of the cases.

The data were collected using the McKenzie lumbar spine

assessment form.

16

The assessment consisted of taking a his-

tory (verbally), observing the spinal range of motion, and com-

pleting specific test movements. The subjects were allowed to

communicate only with examiner number 1 during the history-

taking period. During the questioning, leading questions and

verbal clues were avoided.

The physical examination was performed twice, once by

each examiner. The participants were asked to stand in their

normal relaxed position, with their feet approximately 20 cm

apart, on a marked line. A plumbline passing through C7 to S1

assisted in identifying the presence and direction of a lateral

shift.

The examiners completed the lumbar spine assessment

forms and data collection forms, which were based on the orig-

inal McKenzie form. The syndrome categories were expanded

to subgroups, and the category “other” included inconclusive

mechanical pain patterns and nonmechanical conditions, in

which pain was not presumed to originate from the spine (Ap-

pendix 1). After completing the forms, the examiners sealed

them in envelopes for storage pending data analysis.

Ethics.

The study was approved by the Kuopio University

Hospital Human Ethics Committee.

Statistical Methods.

The variability of the two examiners in

binary decisions was expressed by the kappa (

) coefficient, and

by the proportion of observed agreement. The kappa statistic

provides an index of chance-corrected agreement. Together,

these indexes offer a single expression that summarizes the re-

sults from a 2

⫻ 2 contingency table of concordance.

1,2,8,10

The data were analyzed using SPSS Version 9.0 for the Win-

dows program. Two-sided significance was defined as a P value

less than 0.05. The verbal translations of the kappa scores are

as follows: 0 to 0.20 (poor agreement), 0.21 to 0.40 (slight

agreement), 0.41 to 0.60 (moderate agreement), 0.61 to 0.80

(good agreement), and 0.81 to 1 (very good/excellent

agreement).

1

Results

Lateral Shift and Lateral Component

Visual agreement on the presence and direction of lateral

shift was 77% (

⫽ 0.2; P ⬍ 0.248) and 79% ( ⫽ 0.4;

P

⬍ 0.003), respectively (Tables 3 and 4). The examiners

agreed that the shift was to the right in 15 (54%) of 28

cases. Agreement on the relevance of lateral shift and the

lateral component according to symptom responses was

85% (

⫽ 0.7; P ⬍ 0.000) and 92% ( ⫽ 0.4; P ⬍

0.021), respectively (Table 3).

Centralization Phenomenon and

Directional Preference

Among 34 (87%) patients, whose pain was centralizing,

agreement was 95% (

⫽ 0.7; P ⬍ 0.002) on the central-

ization phenomenon and 90% (

⫽ 0.9; P ⬍ 0.000) on

directional preference. The agreed-on primary direction

was side-gliding to left in 16 patients (47%), and to right

in 9 patients (26%), and extension in 7 patients (21%)

(Tables 3 and 4).

Figure 1. Assessment flow chart for a patient with low back pain.

Table 3. Results of Clinical Tests and McKenzie Main

Syndrome Classification

Examiner 1

Examiner 2

Total

⫹

⫺

Presence of lateral shift (N

⫽ 39)

⫹

28

3

31

⫺

6

2

8

Total

34

5

39

Relevance of lateral shift (N

⫽ 39)

⫹

22

2

24

⫺

4

11

15

Total

26

13

39

Relevance of lateral component (N

⫽ 39)

⫹

1

2

3

⫺

1

35

36

Total

2

37

39

Centralization phenomenon (N

⫽ 39)

⫹

34

1

35

⫺

1

3

4

Total

35

4

39

Directional preference (N

⫽ 39)

⫹

32

1

33

⫺

3

3

6

Total

35

4

39

McKenzie main syndromes (N

⫽ 39)

⫹

35

1

36

⫺

1

2

3

Total

36

3

39

E209

Interexaminer Reliability of the McKenzie Method

•

Kilpikoski et al

Main Syndromes According to the

McKenzie Approach

In classifying patients with LBP into the main syn-

dromes, agreement was 95% (

⫽ 0.6; P ⬍ 0.000). Both

examiners assigned the patients mainly into the derange-

ment syndrome group (90%; 35 of 39 patients). Two

patients were symptom free. The examiners disagreed in

two (5%) cases (Table 3).

Specific Subgroups According to the

McKenzie Approach

In classifying patients with LBP into specific subgroups,

agreement was 74% (

⫽ 0.7; P ⬍ 0.000). The examiners

agreed in defining the same derangement subgroups for

27 (69%) patients. They disagreed about 11 (28%) pa-

tients (Table 5). Of these 11 cases, 9 were classified as

“posterior derangement syndromes,” but into different

subgroups, as shown in Table 5, and 2 were assigned to

a totally different subgroup. One case was classified as

“posterior derangement syndrome 3” by Examiner 2 and

as “extension dysfunction syndrome” by Examiner 1,

and one case was classified as “posterior derangement

syndrome 4” by Examiner 1 and as “mechanically incon-

clusive” by Examiner 2. These two patient groups were

not included into the 2

⫻ 2 contingency table by classi-

fication, but were coded as symptom-free/other group

(value

⫽ 0) to avoid asymmetry in the 2 ⫻ 2 contingency

table (Table 5).

Discussion

In this study, concurrence on certain clinical tests based

on patients’ symptom behavior was found to be moder-

ate to excellent. The study is among those that describe

the proportion of those responding to extension and lat-

eral forces. Donelson et al

6

found that 40% of their study

group had a directional preference for extension. In our

study 64% of the patients responded to lateral forces,

whereas only 18% responded to extension. On the basis

of these responses, patients were classified into the Mc-

Kenzie syndromes with a moderate to good level of

agreement. The reliability was best in defining the cen-

tralization phenomenon, directional preference, and rel-

evance of lateral shift, good in determining main syn-

dromes and subgroup classification, and moderate in

defining the lateral component. Reliability was accept-

able also for defining direction of lateral shift.

The three main mechanical syndromes are postural,

dysfunction, and derangement. “They are characterized

by completely different patterns of mechanical and

symptomatic responses when LBP patients are examined

by a structured repeated end-range movement and static

loading strategy. Each syndrome response to repeated

movement is different from that of other syndromes.”

17

(Appendix 1) “Clinically, patients with pain of postural

syndrome are not often seen.”

17

In fact, no case in the

current study was classified primarily as “postural syn-

drome,” as would be expected of patients with chronic

low back disorder.

As found in the current study, “most patients develop

pain and seek assistance as a result of derangement.”

15

(Tables 3 and 5). This would account for the absence of

Table 4. Distribution of Lateral Shift Directions and

Directional Preferences

Examiner 1

Examiner 2

No shift

Left shift

Right shift

Total

Direction of lateral shift (N

⫽ 39)

No shift

2*

3

3

8

Left shift

2

7*

2

11

Right shift

1

4

15*

20

Total

5

14

20

39

Examiner 1

Examiner 2

No

Extension

SGL Right/

Extension

SGL Left/

Extension

Total

Directional preference (N

⫽ 39)

No

3*

1

0

0

4

Extension

0

7*

0

2

9

SGL

right/

extension

0

0

9*

0

9

SGL left/

extension

1

0

0

16*

17

Total

4

8

9

18

39

Table 5. Distribution of McKenzie Specific Subgroups

Examiner 1

Examiner 2

Symptom Free/Other

Der 1

Der 2

Der 3

Der 4

Der 5

Der 6

Total

Symptom free/other

2*

0

0

1‡

0

0

0

3

Der 1

0

3*

0

1

1

0

0

5

Der 2

0

0

2*

0

0

0

0

2

Der 3

0

0

0

1*

3

0

0

4

Der 4

1†

0

0

0

14*

0

1

16

Der 5

0

0

0

0

0

1*

0

1

Der 6

0

0

0

1

1

0

6*

8

Total

3

3

2

4

19

1

7

39

Der

⫽ derangement syndrome group.

† Includes extension dysfunction syndrome (n

⫽ 1).

‡ Includes “mechanically inconclusive” (n

⫽ 1).

E210 Spine

•

Volume 27

•

Number 8

•

2002

the other syndromes in such a small patient population.

Only one patient was assigned primarily to the “dysfunc-

tion syndrome” group by Examiner 2, and one was “me-

chanically inconclusive” (Appendix 1, Table 5).

This study had certain limitations. The observation

that most patients fell into the derangement category

accords with McKenzie’s original description of this me-

chanical syndrome as occurring most frequently in those

who seek care. It also is consistent with the findings of a

recent study.

15,18

However, the result from having a

sample that is too homogeneous may be overinflation of

the kappa value. Another limitation of this study was the

rather small study population and the use of only two

examiners.

21–23

Despite these limitations, agreement

was statistically significant, which strengthens the

results.

To ensure internal validity, both examiners per-

formed the physical examination of each patient inde-

pendently. In this way, both examiners could make an

independent judgment about the clinical tests and syn-

drome classification. Repetition of the physical examina-

tion may have caused a problem in examining reliability

because of baseline differences in patients tested twice

consecutively. The symptoms reported by patients could

vary between the initial test situation and the second test

trial. Thus, differences in baseline descriptions could af-

fect classification judgment. This problem also was noted

in previous studies,

5,13,18,19

and may explain some dis-

crepancies between examiners.

Despite the limitations of the study, several conclu-

sions agree with those of previous studies.

3,5,9,13,18,19,25

The findings of poor reliability on observational tests is

replicated in earlier studies.

4,13

The interexaminer agree-

ment in classifying patients into the main McKenzie syn-

dromes and the subgroups was good (Tables 3 and 5).

These results are supported by Kilby et al,

13

who showed

that the “McKenzie algorithm” is reliable for the exam-

ination of pain behavior and pain response with repeated

movements on the basis of clinical evaluations by two

physical therapists partially trained in the McKenzie

method. In addition, Razmjou et al

18

demonstrated that

the intertester reliability between two therapists trained

in the McKenzie method is high for classifying patients

with LBP into the McKenzie syndromes. In contrast,

Riddle and Rothstein,

23

in a large group of patients eval-

uated by multiple therapists, found poor intertester reli-

ability in classifying patients into McKenzie syndromes.

The therapists used in their study had limited or no pre-

vious experience with the McKenzie method, and for

many, their only training was an abbreviated version

provided by the study authors. It is unclear whether the

lack of reliability they found was a product of poorly

trained and inexperienced therapists or an intrinsic un-

reliability of the method itself. In comparison, the find-

ings from the current study and other work

13,18

suggest

that a higher level of training in the McKenzie approach

is a significant factor in achieving reliability among

therapists.

In conclusion, the results of this study suggest that

interexaminer reliability in performing clinical tests and

classifying patients with LBP into the main McKenzie

syndromes seems to be high when the therapists have

been trained in the McKenzie method. Future research

should involve a larger patient population that is more

l i k e l y t o c o n t a i n e n o u g h r a r e m e c h a n i c a l

syndromes.

15–18

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Stephen May, BA, MCSP, Dip MDT

MSc, for his valuable assistance in preparing this article.

Key Point

●

The McKenzie method seems to be a reliable pre-

treatment method for classifying patients with non-

specific low back pain into ethiopathogenetically

separate subgroups.

Appendix 1

The McKenzie syndromes, subgroups, and their clinical

presentation

Postural Syndrome

Definition

Pain is caused by mechanical deformation of normal soft

tissues or vascular insufficiency arising from prolonged

positional or postural stresses, affecting any articular or

contractile structures.

15–17

Clinical Presentation

●

Age: usually not over 30 years

●

Poor posture; no movement loss

●

Intermittent, local pain

●

Better when on the move

Test Movements

●

“Repeated movements” do not reproduce the

pain originating from postural syndrome

●

Pain can be reproduced only by sustained posi-

tions or posture

●

Not progressively worse; no rapid changes in

symptom

16,18

Dysfunction Syndrome

Definition

Pain is caused by mechanical deformation of structurally

impaired soft tissues. These abnormal tissues may be the

product of previous trauma, or inflammatory or degenera-

tive process. These events cause contraction, scarring, ad-

herence, or adaptive shortening. Pain is felt when the ab-

normal tissue is loaded. Dysfunction may be located in

articular or contractile tissue.

15–17

E211

Interexaminer Reliability of the McKenzie Method

•

Kilpikoski et al

Flexion Dysfunction Syndrome

Clinical Presentation

●

Age: usually over 30 years, unless trauma or de-

rangement is the causative factor

●

May present with poor posture, and the patient

always has a loss of movement or function

●

Intermittent pain, only at the end of the range of

flexion

●

No pain during movement; no radiation

Test Movements

●

Repeated movements reproduce pain at the end-

range of flexion, but pain not worse as a result of

repeated flexion

●

Not progressively worse; no rapid changes in

symptoms

16,18

Extension Dysfunction Syndrome

Clinical Presentation

●

Age: usually exceeds 30 years, unless trauma or

derangement is the causative factor

●

Poor posture; patient always presents with a loss

of movement or function

●

Intermittent pain only at the end of the range of

extension

●

No pain during movement; no radiation

●

Difficulties while sleeping in prone position

Test Movements

●

Repeated movements reproduce pain at the end

range of extension; symptoms not worse as a result

of repeated extension

●

Not progressively worse; no rapid changes in

symptoms

16,18

Side-Glide Dysfunction Syndrome

Clinical Presentation

●

Age: usually exceeds 30 years unless trauma or

derangement is the causative factor

●

Poor posture; patient always presents with a loss

of movement or function

●

Intermittent pain only at the end of the range of

side-glide

●

No pain during movement; no radiation

Test Movements

●

Repeated movements reproduce pain at the end

range of side-glide, but pain not worse as a result of

repeated side-glide

●

Not progressively worse; no rapid changes in

symptoms

16,18

Multidirectional Dysfunction Syndrome

●

Clinical presentation and principles of treatment

dependent on the direction of dysfunction (see sin-

gle-plane dysfunction subsyndromes)

Adherent Nerve Root Syndrome

Clinical Presentation

●

Intermittent sciatica

Test Movements

●

Flexion in standing produces leg pain, which

stops on return to the upright position

●

Flexion in lying has no effect on symptoms

●

Repeated extension has no effect on symptoms

●

Leg symptoms are produced at end range of flex-

ion in standing

●

Symptoms do not remain worse after the test

movements are stopped

16,18

Derangement Syndrome

Definition

Internal dislocation of articular tissue, of whatever ori-

gin, that causes a disturbance in normal resting position

of the affected joint surfaces. This deforms the capsule

and periarticular supportive ligaments resulting in pain,

which will remain until such time as the displacement is

reduced or adaptive changes have remodelled the dis-

placed tissues. Internal dislocation of articular tissue ob-

structs movement attempted towards the direction of

displacement. In spinal column derangement syndrome

is caused by internal disruption and displacement of the

fluid nucleus/anulus complex of the outer innervated

anulus fibroses and/or adjacent soft tissues resulting in

back pain alone or back pain and referred pain depend-

ing on the degree of internal displacement and whether

or not this causes compression of the nerve root.

15–17

Derangement 1

Clinical Presentation

●

Central/symmetrical pain, rarely buttock or

thigh pain

●

No postural deformity

Test Movements

●

Repeated flexion usually increases; peripheral-

izes pain

●

Pain often remains worse as a result of repeated

flexion

●

Repeated extension usually reduces, centralizes,

and abolishes pain

●

Pain usually remains better as a result of repeated

extension

16,18

Derangement 2

Clinical Presentation

●

Usually constant central or symmetrical pain,

with or without buttock or thigh pain

●

Deformity of lumbar kyphosis

E212 Spine

•

Volume 27

•

Number 8

•

2002

Test Movements

●

Repeated flexion progressively increases and pe-

ripheralizes the pain

●

Pain usually remains worse as a result of re-

peated flexion

●

Time factor is important in Derangement 2 (cor-

rection of blockage in extension requires time for a

successful reduction)

●

Repeated extension, therefore, may not be pos-

sible initially

●

Sustained positioning is attempted if a major de-

formity of kyphosis exists

●

Pain initially decreases with prone lying in flexed

position; derangement reduces gradually by in-

creasing the extension in unloaded position

16,18

Derangement 3

Clinical Presentation

●

Unilateral or asymmetrical pain, with or without

buttock or thigh pain

●

No postural deformity

Test Movements

●

Repeated flexion usually increases; peripheral-

izes pain

●

Pain may remain worse as a result of repeated

flexion

●

Repeated extension usually reduces, centralizes,

and abolishes pain; if pain does not decrease or

centralize with extension, then side-glide with ex-

tension decreases the pain

16,18

Derangement 4

Clinical Presentation

●

Usually constant unilateral or asymmetrical

pain, with or without buttock or thigh pain

●

Deformity of sciatic scoliosis (lateral shift)

Test Movements

●

Repeated flexion and extension usually increases

and peripheralizes the pain

●

Symptoms usually remain worse as a result of

sagittal movements (flexion and extension) because

of lateral shift deformity

●

Correction of lateral shift decreases and central-

izes the pain

●

If the lateral shift can be successfully corrected,

extension procedures often complete the reduction

of the hypothesized derangement

16,18

Derangement 5

Clinical Presentation

●

Unilateral or asymmetrical pain, with or without

buttock or thigh pain

●

No postural deformity

●

Leg pain extending below knee joint (constant or

intermittent sciatica)

Test Movements

●

Repeated flexion usually increases; peripheral-

izes pain

●

Symptoms may remain worse as a result of re-

peated flexion

●

Repeated extension usually decreases, central-

izes, and abolishes pain; if unsuccessful, then side-

glide or rotation techniques decrease the pain

16,18

Derangement 6

Clinical Presentation

●

Unilateral or asymmetrical pain, with or without

buttock or thigh pain

●

Leg pain extending below the knee (usually con-

stant sciatica)

●

Deformity of sciatic scoliosis (lateral shift)

Test Movements

●

Repeated flexion and extension increase or pe-

ripheralize the symptom

●

Symptoms usually remain worse as a result of

sagittal movements (flexion and extension) because

of lateral shift deformity

●

Correction of lateral shift decreases and central-

izes the pain

●

If the lateral shift can be successfully corrected,

extension procedures often complete the reduction

of the hypothesized derangement

16,18

Derangement 7

Clinical Presentation

●

Symmetrical or asymmetrical pain, with or with-

out buttock or thigh pain

●

Deformity of accentuated lordosis

Test Movements

●

Repeated extension increases and may peripher-

alize the pain

●

Symptoms remain worse as a result of repeated

extension

●

Repeated flexion decreases and centralizes the

pain

●

Symptoms remain better as a result of repeated

flexion

16,18

Other

Nerve Root Entrapment Syndrome

Clinical Presentation

●

Longstanding, constant radicular-type pain or

paraesthesias

Test Movements

●

Repeated flexion may reduce the pain tempo-

rarily, but the patient is no better as a result

●

Range increases temporarily

E213

Interexaminer Reliability of the McKenzie Method

•

Kilpikoski et al

●

Repeated extension may increase symptoms tem-

porarily, but the patient does not remain worse

after testing.

16,18

Inconclusive Mechanical Pain Pattern

Behavior of mechanical presentation, for instance move-

ment loss, in response to particular loading strategy, but

conclusion of syndrome classification is still unclear or

inconclusive.

15–18

Nonmechanical Low Back Pain

Pain not of spinal origin such as SI joint dysfunction.

16,18

References

1. Bogduk N. Musculoskeletal Pain: Toward Precision Diagnosis. Proceedings

of the 8th World Congress on Pain. Prog Pain Res Manage 1997;8:507–25.

2. Cincchetti DV, Feinstein AR. High agreement but low kappa: II. Resolving

the paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43:551– 8.

3. Delitto A, Snyder-Mackler L. The diagnostic process: examples in orthopedic

physical therapy. Phys Ther 1995;75:203–11.

4. Donahue MS, Riddle DL, Sullivan MS. Intertester reliability of a modified

version of McKenzie’s lateral shift assessments obtained on patients with low

back pain. Phys Ther 1996;76:706 –16.

5. Donelson R. Reliability of the McKenzie assessment. J Orthop Sports Phys

Ther 2000;30:770 –3.

6. Donelson R, Grant W, Kamps C, et al. Pain response to sagittal end-range

spinal motion. A prospective, randomized, multicentered trial. Spine 1991;

16:S206 –12.

7. Donelson R, Murphy K, Silva G. Centralisation phenomenon: its usefulness

in evaluating and treating referred pain. Spine 1990;15:211–3.

8. Feinstein AR, Cincchetti DV. High agreement but low kappa: I. The prob-

lems of two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol 1990;43:543–9.

9. Fritz JM, Delitto A, Vignovic M, et al. Interrater reliability of judgements of

the centralisation phenomenon and status change during movement testing

in patients with low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:57– 60.

10. Gjorup T. The kappa coefficient and the prevalence of a diagnosis. Methods

Inf Med 1988;27:184 – 6.

11. Jensen IB, Bodin L, Ljungqvist T, et al. Assessing the needs of patients in pain:

a matter of opinion? Spine 2000;25:2816 –23.

12. Kankaanpa¨a¨ M, Taimela S, Airaksinen O, et al. The efficacy of active reha-

bilitation in chronic low back pain. Spine 1999;24:1034 – 42.

13. Kilby J, Stigant M, Roberts A. The reliability of back pain assessment by

physiotherapists using a “Mckenzie algorithm.” Physiotherapy 1990;76:

579 – 83.

14. McCombe PF, Fairbank JCT, Cockersole BC, et al. Reproducibility of phys-

ical signs in low back pain. Spine 1989;9:908 –18.

15. McKenzie RA. The Cervical and Thoracic Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis and

Therapy. Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal Publications, 1990.

16. McKenzie RA. The Lumbar Spine: Mechanical Diagnosis and Therapy.

Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal Publications, 1981.

17. McKenzie RA, May S. Human Extremities: Mechanical Diagnosis and Ther-

apy. Waikanae, New Zealand: Spinal Publications, 2000.

18. Razmjou H, Kramer JF, Yamada R. Intertester reliability of the McKenzie

evaluation in assessing patients with mechanical low back pain. J Orthop

Sports Phys Ther 2000;30:368 – 83.

19. Razmjou H, Kramer JF, Yamada R, et al. Author response. J Orthop Sports

Phys Ther 2000;30:386 –9.

20. Riddle DL. Classification and low back pain: a review of the literature and

critical analysis of selected systems. Phys Ther 1998;78:708 –37.

21. Riddle DL. Invited commentary. Intertester reliability of the McKenzie eval-

uation in assessing patients with mechanical low back pain. J Orthop Sports

Phys Ther 2000;30:384 – 6.

22. Riddle DL. Reliability of the McKenzie assessment. Author response. J Or-

thop Sports Phys Ther 2000;30:773–5.

23. Riddle DL, Rothstein JM. Intertester reliability of McKenzie’s classifications

of the syndrome types present in patients with low back pain. Spine 1993;

18:1333– 44.

24. Spitzer W. Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity-

related spinal disorders. Spine 1987;7S:S1–55.

25. Tenhula JA, Rose SJ, Delitto A. Association between direction of lateral

lumbar shift, movement tests, and side of symptoms in patients with low

back pain syndromes. Phys Ther 1990;70:480 – 6.

26. Werneke M, Hart D, Cook D. A descriptive study of the centralisation

phenomenon: a prospective analysis. Spine 1999;24:676 – 83.

Address reprint requests to

Sinikka Kilpikoski, MSc

Department of Health Sciences

University of Jyva¨skyla¨

P. O. Box 35, 40351 Jyva¨skyla¨

Finland

E-mail:sinikka.kilpikoski@kolumbus.fi

E214 Spine

•

Volume 27

•

Number 8

•

2002

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

(IV)A Preliminary Report on the Use of the McKenzie Protocol versus Williams Protocol in the Treatme

Association of low back pain

(IV)Intertester reliability of the McKenzie evaluation in assessing patients with mechanical low bac

(IV)The McKenzie approach to evaluating and treating low back pain

Categorizing patients with occupational low back pain by use of the Quebec Task Force Classification

The relationship of Lumbar Flexion to disability in patients with low back pain

low back pain

low back pain 2

Serum cytokine levels in patients with chronic low back pain due to herniated disc

Treating Non Specific Chronic Low Back Pain Through the Pilates Method

(IV)The diagnostic utility of McKenzie clinical assessment for lower back pain

(IV)Relative therapeutic efficacy of the Williams and McKenzie protocols in back pain management

(IV)McKenzie method and functional training in back pain rehabilitation A brief review including res

the!st?ntury seems to hale found an interesting way of solving problems OQ5R2UJ7GCUWHEDQYXYPNT2RBNFL

03 Electrophysiology of myocardium Myocardial Mechanics Assessment of cardiac function PL

Design Guide 10 Erection Bracing of Low Rise Structural Steel Frames

więcej podobnych podstron