9 Investigating the Faunal Record from Bronze

Age Cyprus: Diversification and Intensification

Matthew Spigelman

Abstract

This paper uses data from published faunal reports to reconstruct strategies of faunal

exploitation practiced in Cyprus during the Early Cypriot – EC, Middle Cypriot – MC and Late

Cypriot – LC periods of the Bronze Age. Paul Croft published the data for Sotira and Marki (1996,

2003, 2006), David Reese for Alambra and Athienou (1996, 2005), Brian Hesse, Anne Ogilvy

and Paula Warnish for Phlamoudhi-Melissa and Vounari (1977, 1978), Rita Larje for Nitovikla

(1992) and Nils-Gustaf Gejvall for Kalopsidha (1966). The basic comparison of represented species

presented here between the EC and MC assemblages has also recently appeared in Paul Croft’s

discussion of the faunal assemblage from Marki (2006). My contribution in this paper has been to

bring together data from the EC, MC and LC periods, in terms of both species diversity and kill

patterns, and to contextualize these findings within models of animal husbandry practices and social

systems.

This paper consists of two sections. The first compares data on species diversity found at sites

of the EC and MC periods with that from the LC period. It is shown from these data that EC and

MC inhabitants practiced a diversified faunal strategy, utilizing a suite of animal resources, both wild

and domesticated. This diversified local economy contained inherent buffering mechanisms against

resource failure. It is argued that these internal buffering mechanisms obviated the need for large-scale

storage or extended social networks.

This diversified faunal economy is sharply contrasted by the LC data. LC data reveals a shift

to a faunal strategy focused upon a limited number of domesticated species, utilized primarily for their

secondary products. This intensified economic strategy allowed for higher productivity but removed the

internal buffering mechanisms provided by a diversified economy. It is argued that LC inhabitants

developed strategies of social and/or physical storage to buffer against the increased risks of catastrophic

resource failure from this intensified strategy.

The second section of the paper investigates the kill patterns for sheep and goats in the EC

through MC and the LC periods. Strategies of herd management can be reconstructed through an

analysis of the ages at which animals are killed (Silver 1963; Crabtree 1989). It is found that in the

EC through MC periods sheep and goats were utilized for both meat and secondary products. In the

LC period, however, herd management strategies shifted to the intensive production of secondary

products.

Species Diversity at EC and MC

Period Sites

Sizeable faunal assemblages have been

recovered and published from the EC

through MC period sites of Sotira,

Marki and Alambra. These assemblages

correlate well with each other for

species diversity (the number of species

represented) and richness (the relative

proportions of these species to one

120

another). Species variability found at

each site is measured using number of

identifiable specimens, or NISP. The

NISP measurement counts every bone

that can be assigned to a specific

element and species. As such it is well

suited to smaller assemblages, such as

some of the ones incorporated here.

The alternative measure of minimum

number of individuals, or MNI, was not

used as it can give distorted results for

small assemblages. The size of the

assemblages is listed on the chart below

the site names. Assemblage size is

determined by bone preservation,

recovery techniques, volume of

excavated material and habits of the site

inhabitants. No attempt has been made

here to disentangle these processes.

Moving chronologically, we will first

look at the EC assemblages from Sotira

and Marki. Both assemblages show the

utilization of sheep and goat, cattle, wild

deer and pig, in that order. These

similar patterns of species use

demonstrate that a common strategy of

faunal exploitation was practiced in the

EC period. The location of Sotira and

Marki in different regions of the island

suggests that this strategy was present

over a wide geographical area. The site

of Marki spans the EC and MC periods.

The faunal assemblages from these two

periods show continuity in both species

diversity and richness.

The MC assemblage from Marki can be

compared with the contemporary one

from Alambra. Here too we find

comparable species diversity. The

assemblage from Alambra, however,

contrasts slightly with those from Sotira

and Marki in richness, as deer are better

represented than cattle. At all three EC

and MC site, Sotira, Marki and Alambra,

we see a consistent pattern of species

diversity suggesting a common strategy

of exploitation that spanned great

temporal and geographical distances.

The EC to MC faunal assemblages

briefly described here are characterized

by species diversity. Species diversity is

a risk averse strategy that seeks to

buffer the effects of resource failure by

relying on a suite of resources. The

diverse EC-MC faunal assemblages

show evidence for two quite different

mechanisms of risk aversion. The first

of these is the keeping of a range of

domestic animals: sheep, goats, cattle

and pigs. Resource failure in any one

species would have been buffered

against by increased exploitation of the

others.

The second risk averse behavior is the

hunting of wild deer. Hunting would

have taken place outside of the agro-

pastoral economy. The regular

exploitation of wild resources by agro-

pastoral economies often serves as a

means of providing additional resources

during the period(s) of the year when

stored resource are running low and the

next season’s crop is not yet ready for

harvest (Stein 1989). The hunting of

wild deer may have served this purpose

in the EC-MC economy. Agro-pastoral

groups also exploit wild resources

during times of extreme resource

failure. Hunting most likely served

both of these roles in the EC-MC

economy. Hunting is a high skill

activity and as such must be maintained

and passed on to subsequent

generations on a regular basis. If

hunting is expected to form a buffering

mechanism in times of dire need then

the necessary skills must be maintained

on a regular, most likely yearly, basis.

Species Diversity at LC Period Sites

Moving chronologically forward into

the LC period we can investigate faunal

121

assemblages from the sites of Nitovikla,

Phalmoudhi-Melissa and Vounari,

Athienou-Pampoularis and Kalopsidha.

The plotting of species percentages for

LC sites reveals a shift to a faunal

economy focused almost exclusively on

sheep and goats. Sheep and goats make

up over 90% of the assemblages at all

sites save for Nitovikla. Cattle are

found in all faunal assemblages but at

exceedingly low levels. The hunting of

wild deer is only attested to at

Athienou, and only in very small

amounts. Pig remains are similarly

sparse, only seen by a small number of

bones at Melissa.

In contrast to the EC and MC periods,

the LC faunal economy is neither

diverse nor rich. It is instead

characterized by the intensive

exploitation of a limited number of

species, namely sheep and goats. This

dramatic shift reveals the abandonment

of the buffering mechanisms inherent in

a diversified economy. Sheep and goat

now dominate the pastoral sector, and

the practice of hunting wild deer has

been all but abandoned. An intensified

economy offers the prospect of more

efficient use of resources, both human

effort and grazing land, but sacrifices

security.

The shift to an intensified LC faunal

economy necessitated the development

of new mechanisms for buffering

resource failure. Increased physical

storage is evidenced at this time

through the appearance of storage

pithoi (Pilides 1996). Physical storage

can take place within social structures

that range from egalitarian to highly

ranked. The development of social

storage, however, requires the

formation of long distance

relationships. These relationships can

be called upon during times when

resource failure affects one local but not

another. Increased interaction between

communities leads to, and is aided by,

the development of distinct local

identities. This process of identity

formation represents the development

of horizontal social structure between

communities.

Herd Management Strategies at EC

and MC Period Sites: Sheep and

Goat Kill Patterns

The shift from the EC and MC to the

LC faunal economy also witnesses

changes to the strategy of sheep and

goat exploitation. In this second

section of the paper these shifting

strategies are modeled using evidence of

kill patterns as derived from data on

epiphysial fusion. Variable states of

epiphysial fusion provide a means of

assessing the age at which an animal

was killed. The ends of bones, the

epiphyses, fuse to the shaft of the bone

at a given point in the maturation

process. Some epiphyses are already

fused at birth while others do not fuse

until the animal reaches maturity. Using

known ages of epiphysial fusion for

specific bones the presence of unfused

bones provide a terminus ante quem for

the age of the animal at death (Silver

1963). Bones are grouped into early,

middle and late fusing elements

corresponding to 0-1 year, 1-2.5 years

and 2.5-3 years (Crabtree 1989). A kill

pattern for an assemblage can be

constructed by graphing the ratio of

fused and unfused bones for each of

these groups. At the left of the graph

the herd starts at 100%. The first data

point shows the percentage of the herd

killed before reaching 1 year of age.

The second data point shows the

percentage of animals killed before

reaching 2.5 years and the third data

point shows those killed before 3 years.

If the graph were extrapolated to the

122

right it would eventually reach zero

upon the death of all animals. The

graph represents an average of the kill

pattern for the entirety of the period in

which the assemblage was formed.

Kill patterns can be interpreted using

known lifecycle events and animal

husbandry practices, as observed

through ethnoarchaeological research.

Lifecycle events, such as age of

reproductive maturity, maximum meat

yield and decline in female fertility,

occur at predictable ages. The killing of

an animal either before or after any

such lifecycle event provides insight

into the goals of the exploitation

strategy.

Sheep and goats are notable in that they

can be utilized for both their meat as

well as for their secondary products,

such as milk and wool or hair. Sheep

and goats approach their maximum

meat yield at some time between 2.5

and 3 years of age (Redding 1981). An

animal killed before this point will

provide less meat while an animal

allowed to live past it will continue to

consume resources with little to no

additional meat yield. Animals that are

kept beyond 3 years of age indicate their

use in producing secondary products

and/or in maintaining the demographic

security of the heard through the

production of offspring.

The kill patterns of sheep and goats at

the EC and MC period sites of Sotira,

Marki and Alambra all show 10 to 20%

of animals dying before reaching one

year of life. These early deaths can be

attributed to natural causes and are

most likely an underestimate as fragile

infant bones are less likely to have

survived. Ethnographic accounts

indicate that on average 30% of sheep

and 45% of goats die of natural causes

within their first 6 months of life

(Redding 1981).

These same kill patterns show only a

small percentage, less than 5%, of the

herd killed between the ages of 1 and

2.5 years. This low amount is to be

expected in a meat producing economy,

as these juvenile animals have not yet

reached their maximum weights. The

kill patterns, however, change drastically

after 2.5 years, with one quarter to one

third of the herd killed between the ages

of 2.5 to 3 years. It is during this brief

period that killing an animal for its meat

is most efficient (Redding 1981).

The kill patterns from Marki and

Alambra indicate that 45 to 60 percent

of sheep and goats lived past the age of

three, reaching full maturity. Because

of the small size of the Sotira

assemblage it is not possible to know

what percentage of animals lived to

maturity there. Mature animals

provided both the reproductive capacity

to continue the herd and a source of

secondary products. Female sheep and

goats give birth for the first time at two

years of age and every year thereafter

until the age of 6 or 7, at which point

female fertility begins to decline. Milk

production is triggered in pregnant

females. Young animals require

mother’s milk until the age of 2 to 3

months of age at which point they can

be weaned and the milk taken for

human consumption. Additionally,

sheep would have provided wool and

goats hair, both usable for textile

production.

Similar exploitation strategies at all three

sites, Sotira, Marki and Alambra,

reinforce the view of self-reliant

settlements utilizing sheep and goat for

their meat and their milk, wool and hair.

There is no evidence for the over or

under production of any one of these

123

products, and as such there is no

evidence for the import or export of

goods. This finding does not

demonstrate that EC through MC

settlements were egalitarian

communities per se but it does indicate

an absence of mechanisms for the

production of significant amounts of

surplus through faunal exploitation.

Herd Management Strategies at LC

Period Sites: Sheep and Goat Kill

Patterns

Of the LC faunal assemblages only

those from Athienou and Melissa

contain sufficient evidence to

reconstruct the kill patterns of sheep

and goats.

The settlement site of Melissa shows a

kill pattern that indicates the intensive

exploitation of sheep and goats for their

secondary products. The kill pattern

reveals 20% of the herd dieing within

their first year of life, a similar

percentage to those found in the EC

and MC. A new pattern of exploitation

is revealed by the killing of some 30%

of the herd between the ages of 1 and

2.5 years. Equally dramatic is that all

animals that reach 2.5 years of age are

allowed to reach full maturity.

The killing of juvenile animals, under

2.5 years of age, sacrifices meat yields,

as these animals have not yet begun to

approach their maximum weight. The

killing of young animals, however,

serves to free up resources for the older

mature animals. These older animals

are the primary producers of secondary

products. If milk production by goats is

the goal then adult females are needed

and young males are culled. For wool

production by sheep, castrated adult

males are most productive so young

females are culled. These culling

practices allowed for the more efficient

converting of resources into secondary

products, however, they produce

skewed herd profiles (both for sex and

age) increasing the risk of demographic

collapse due to sickness or accidental

deaths.

The kill pattern for sheep and goats at

Athienou has a similar shape to that of

Melissa, however, it is located at the

base of the graph, as it is almost

exclusively comprised of young

individuals. The Athienou kill pattern

reveals that a full 85% of the sheep and

goats were killed before reaching 1 year

of age. Additionally, over 95% of the

animals were killed before reaching 2.5

years of age. Viewed on its own the

Athienou kill pattern represents an

unsustainable herd management

strategy. Interpreted in conjunction

with the Melissa data, however, it

reinforces the model of a faunal

economy focused on the intensive

production of secondary products at the

expense of meat production. The

young animals killed at Athienou would

have further helped to create a herd

composed of wool producing mature

male sheep and milk producing mature

female goats.

The assemblage from Athienou is dated

to the LC II period, however, a similar

assemblage of predominately juvenile

sheep and goats was excavated at

Kalopsidha-Trench 9 and is dated to

the LC I period. This assemblage was,

unfortunately, published without data

on epiphysial fusion, however, it was

stated that 77% of the animals were

“infantile or subadult” (Gejvall 1966).

While this method of classification

makes the reconstruction of a kill

pattern impossible, the high percentage

of young animals suggests that the

pattern shown at Athienou in the LC II

period can be extrapolated back into the

LC I at Kalopsidha.

124

As previously stated, the kill patterns of

sheep and goats at Kalopsidha and

Athienou represent an unsustainable

herd management strategy if viewed in

isolation. They are sensible, however, if

viewed as the transport of young sheep

and goats from other sites to specialized

– non-settlement – locations for

slaughter. This pattern raises the

possibility that Athienou and

Kalopsidha were aggregation localities

where members of different

communities came together to build

relationships between their

communities. We see at Athienou and

Kalopsidha an intersection of the duel

needs of the intensified LC economy:

the killing off of young sheep and goats

to conserve resources and the building

of long distance relationships to

facilitate the buffering mechanism of

social storage.

To summarize, the faunal economy of

the EC through MC periods is

characterized by the exploitation of a

diverse range of species in a risk averse

manner. This strategy included both

domesticated and wild animals. Each

site was able to provide its own internal

mechanisms of buffering resource

failure. The LC period sites show the

intensive exploitation of sheep and

goats for their secondary products.

This strategy was more efficient but

removed the buffering mechanisms

inherent in the earlier system. The

development of new buffering

mechanisms required increased contact

between settlements and strengthened

local identities. The new non-

settlement sites first seen in this period,

such as Athienou and Kalopsidha, could

have served as the location of inter site

interaction, facilitating the development

of social storage networks.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my advisors Rita

Wright and Pam Crabtree for their

helpful comments on this paper and

New York University for the Student

Travel Grant that has allowed me to

attend these meetings.

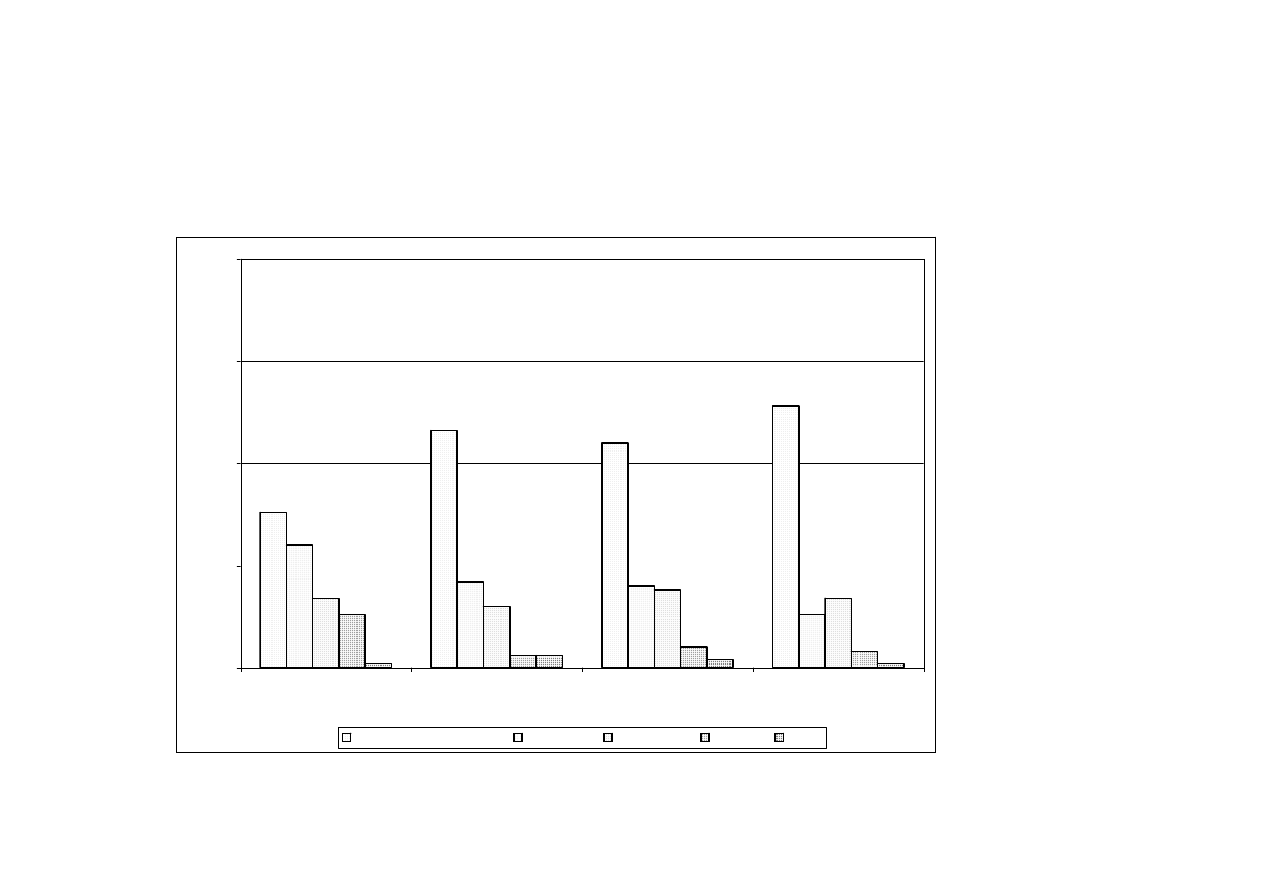

Figure 1 NISP for EC and MC period sites.

Data from Croft (1996, 2003, 2006) and Reese (1996).

0

25

50

75

100

Sotira-Kaminoudhia (EC)

(n=426)

Marki-Alonia (EC I-III)

(n=6107)

Marki-Alonia (MC I)

(n=4410)

Alambra-Mouttes (MC)

(n=991)

%

Ovis/Capra (Sheep/Goat)

Bos (Cattle)

Dama (Deer)

Sus (Pig)

Other

126

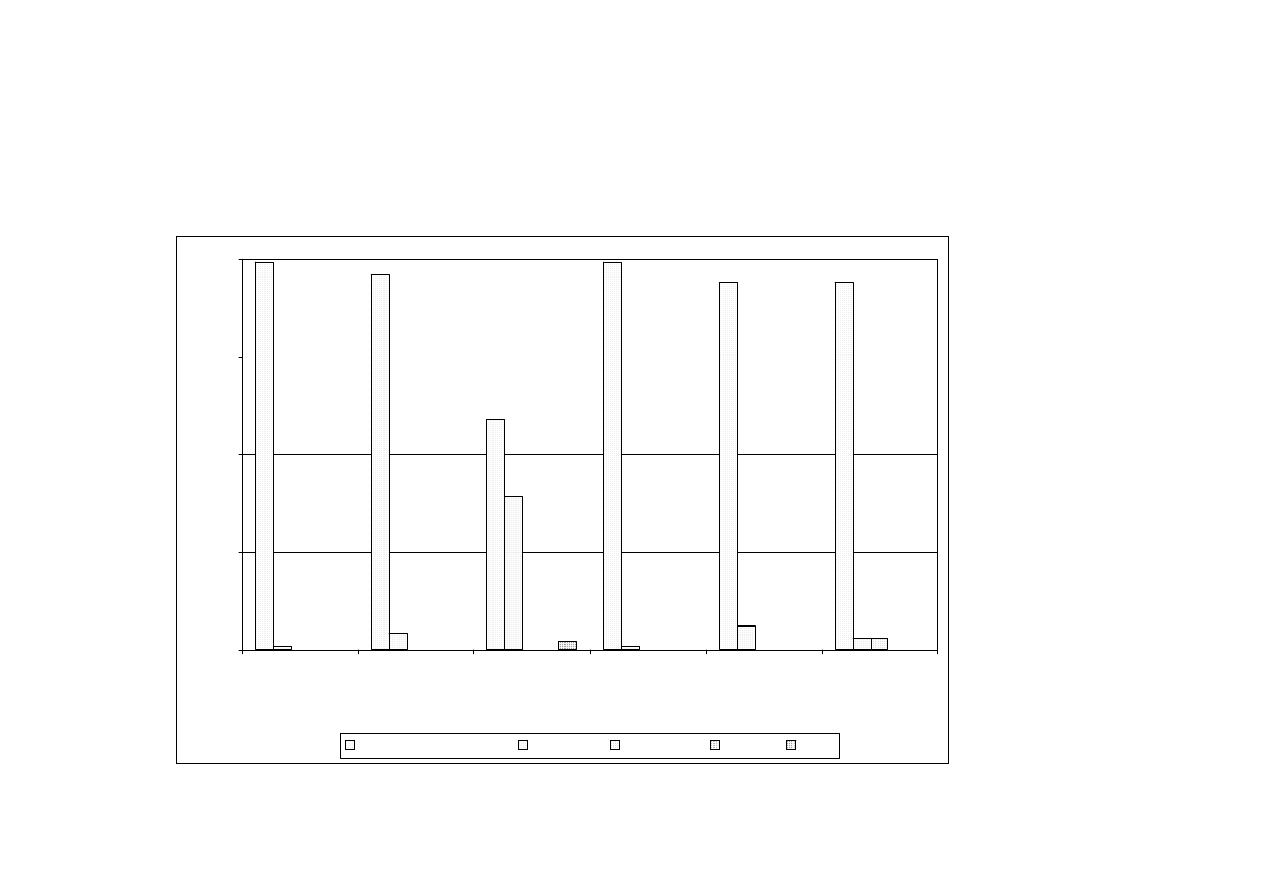

Figure 2 NISP for EC, MC and LC period sites.

Data from Gejvall (1966), Hesse et al. (1977, 1978), Larje (1992), Reese (2005).

0

25

50

75

100

Phlamoudhi-

Vounari (MC III -

LC I) (n=76)

Phlamoudhi-

Melissa (LC I)

(n=394)

Nitovikla (LC I)

(n=82)

Kalopsidha

Trench 9 (LC I-II)

(n=742)

Phlamoudhi-

Melissa (LC II)

(n=68)

Athienou-

Pampoulari (LC

II) (n=897)

%

Ovis/Capra (Sheep/Goat)

Bos (Cattle)

Dama (Deer)

Sus (Pig)

Other

127

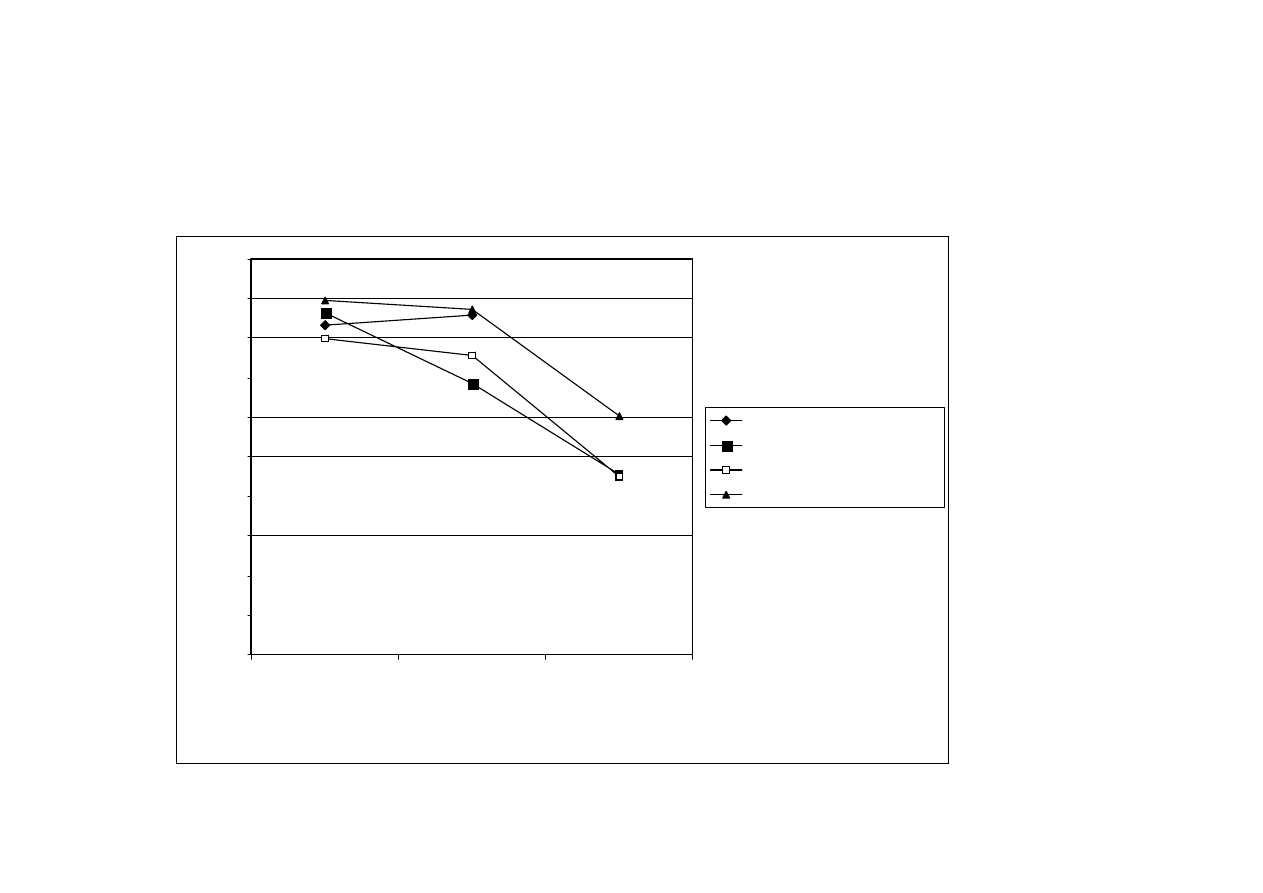

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

Early Fusing

(before 1 year)

Middle Fusing

(before 2.5 years)

Late Fusing

(before 3 years)

Anatomical Elements

%

F

u

sed

Sotira - EC (n=43)

Marki - EC I - EC III (n=697)

Marki - MC I (n=356)

Alambra - MC (n=231)

Figure 3 Kill patterns of sheep and goats at EC and MC period sites.

Data from Croft (1996, 2003, 2006) and Reese (1996).

References

Crabtree, P. 1989. West Stow, Suffolk: Early Anglo-Saxon Animal Husbandry. East Anglian

Archaeology Report No. 47. Suffolk: Suffolk County Planning Dept.

Croft, P. 1996. Animal Bones, in Frankel, D. and Webb, J. (eds.) Marki Alonia. An Early

and Middle Bronze Age Town in Cyprus. Excavations 1990-1994. Studies in

Mediterranean Archaeology, Volume 123. Goteborg: Paul Astroms Forlag.

Croft, P. 2003. The Animal Remains, in Swiny, S., Rapp, G. and Herscher, E. (eds.)

Sotira Kaminoudhia: An Early Bronze Age Site in Cyprus. Cyprus American Archaeology

Research Institute Monograph Series, Volume 4. Boston: The American Schools of

Oriental Research, 439-448.

Croft, P. 2006. Animal Bones, in Frankel, D. and Webb, J. (eds.) Marki Alonia. An Early

& Middle Bronze Age Settlement in Cyprus. Excavations 1995-2000. Studies in

Mediterranean Archaeology, Volume 123, number 2. Goteborg: Paul Astroms Forlag.

Gejvall, N-G. 1966. Osteological Investigations of Human and Animal Bone Fragments

from Kalopsidha, in Astrom, P. (ed.) Excavations at Kalopsidha and Ayios Iakovos in

Cyprus. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology, Volume 2. Lund: Paul Astroms Forlag,

128-132.

Heese, B., Ogilvy, A. and Wapnish, P. 1977. The Fauna of Phlamoudhi – Melissa: An

Interim Report. Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus, 5-29.

Heese, B., Ogilvy, A. and Wapnish, P. 1983. Report on the Fauna from Phlamoudhi

Vounari, in Al-Radi, S. (ed.) Phlamoudhi Vounari: A Sanctuary Site in Cyprus. Studies in

Mediterranean Archaeology, Volume 65. Goteborg: Paul Astroms Forlag, 116-118.

Larje, R. 1992. The Bones from the Bronze Age Fortress of Nitovikla, Cyprus, in Hult,

G. (ed.) Nitovikla Reconsidered. Medelhavsmuseet Memoir 8. Stockholm:

Medelhavsmuseet, 166-175.

Pilides, D. 1996. Storage jars as evidence of the economy of Cyprus in the Late Bronze

Age, in V. Karageorghis and D. Michaelides (eds.) The Development of the Cypriot Economy

from the Prehistoric Period to the Present. Nicosia.

Redding, R. 1981. Decision Making in Subsistence Herding of Sheep and Goats in the Middle

East. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Michigan.

Reese, D. 1996. Subsistence Economy, in Coleman, J., Barlow, J., Mogelonsky, M. and

Schaar, K. (eds.) Alambra: A Middle Bronze Age Settlement in Cyprus; Archaeological

Investigations by Cornell University. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology, Volume 118.

Goteborg: Paul Astroms Forlag, 217-226.

Reese, D. 2005. Faunal Remains from Israeli Excavations at Athienou-Pampoulari tis

Koukkouninas. Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus: 87-108.

129

Silver, I. 1963. The Ageing of Domestic Animals, in Brothwell, D. and Higgs, E. (eds.)

Science in Archaeology. New York: Praeger, 283-302.

Stein, G. 1989. Strategies of Risk Reduction in Herding and Hunting Systems of

Neolithic Southeast Anatolia, in Crabtree, P. and Campana, D. (eds.) Early Animal

Domestication and Its Cultural Context. MASCA Research Papers in Science and

Archaeology. Special Supplement to Volume 6, 1989. Philadelphia: The University

Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, 87-97.

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Understanding the productives economy during the bronze age trought archeometallurgical and palaeo e

BRONZE AGE ROCK ART AND BURIALS IN WEST NORWAY

A Samson, Offshore finds from the bronze age in north western Europe the shipwreck scenarion revisi

S Karg, Direct evidence of heathland management in the early Bronze Age (14th century B C ) from the

A F Harding, European Societies in the Bronze Age (chapter 6)

Palaikastro Shells and Bronze Age Purple Dye Production in the Mediterranean Basin

A F Harding, European Societies in the Bronze Age (chapter 12)

Inhibitory Effect of Dry Needling on the Spontaneous Electrical Activity Recorded from Myofascial Tr

Use and signifance of socketed axes during the late bronze age

RECHT Sacrifice in the bronze age Aegean and near east

An%20Analysis%20of%20the%20Data%20Obtained%20from%20Ventilat

Does the number of rescuers affect the survival rate from out-of-hospital cardiac arrests, MEDYCYNA,

On the Actuarial Gaze From Abu Grahib to 9 11

D Stuart Ritual and History in the Stucco Inscription from Temple XIX at Palenque

Investigating the Afterlife Concepts of the Norse Heathen A Reconstuctionist's Approach by Bil Linz

3 2 4 6 Packet Tracer Investigating the TCP IP and OSI Models in?tion Instructions

Understanding the misunderstood Art from different cultures

więcej podobnych podstron