Andrew Simpson and Noi Thammasathien

18.1 Introduction

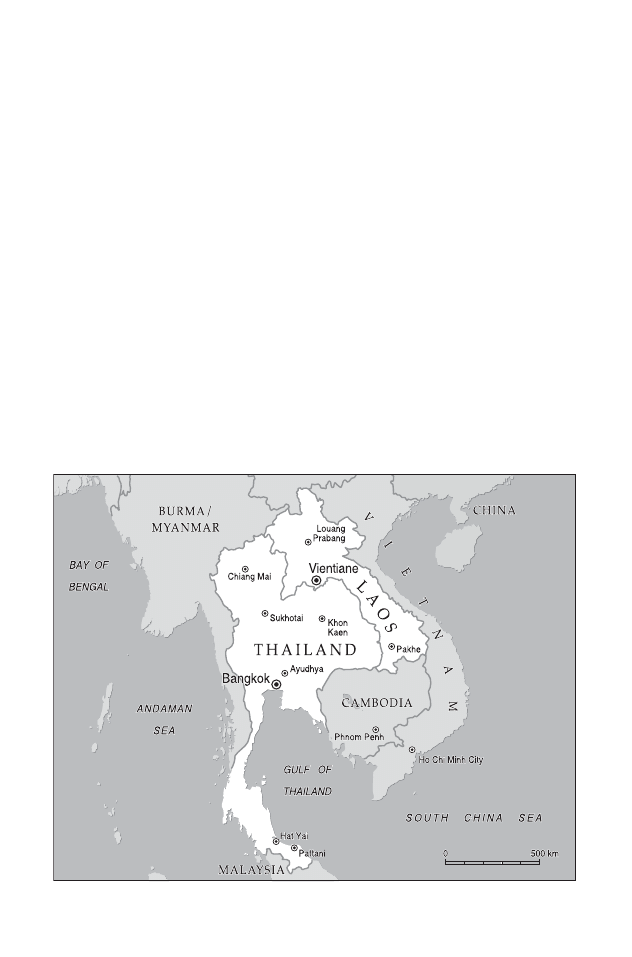

This chapter examines language and national identity issues in Thailand and also

Laos. These two neighbouring states are grouped together here for the reason that

both contain heavily dominant ‘Tai’ populations and have a long history of interaction

with each other. The term ‘Tai’ itself refers to a particular group of languages which

form a language family distinct from other major language families of east and

southeast Asia such as the surrounding Sino-Tibetan, Austro-Asiatic and Austronesian

groups. Speakers of the Tai group of languages originated in southeast China but

migrated far and wide during the seventh to thirteenth centuries, reaching Assam in

the west, northern Vietnam in the south, and modern-day Thailand and Laos in the

southwest, where the greatest concentration of Tai speakers is still to be found, with

57 million in Thailand (90 per cent of the population), and 4 million in Laos (66 per

cent of the population). The term ‘Thai’ (pronounced with an aspiration on the initial

consonant which is absent from the pronunciation of ‘Tai’) is normally used to refer

just to the inhabitants of Thailand, both as formal citizens of the country and as

members of a single ethnic group identiWed by a largely shared language and culture.

It is also frequently used to refer to the standardized variety of speech which has been

strongly promoted within Thailand – Standard Thai. The term ‘Lao’ performs a

similar function within the People’s Democratic Republic of Laos, being used to

refer to citizens of the country and also to the particular sub-variety of Tai language

and culture which is found throughout signiWcant parts of the country. As will later be

seen, both the terms ‘Thai’ and ‘Lao’ have been of considerable importance in

attempts to mould national identities within the two countries.

As the chapter will note, modern Thailand stands out in southeast Asia as a country

which seems to be remarkably homogeneous from a linguistic and ethnic point of

view, yet the obvious dominance of Thai language and culture in the country actually

overlays a complex patchwork of some sixty other languages which are regularly used

by the inhabitants of Thailand, generally without the occurrence of major language/

ethnic group-related disturbances. Such apparent ‘unity amongst diversity’ which

distinguishes Thailand from various other countries in the region has been commen-

ted on in many works (Keyes 1989, Smalley 1994, Reynolds 1991b) and is the clear

result of a hundred years of state-controlled language-planning initiatives in conjunc-

tion with sustained and highly successful eVorts at nation-building. Thailand is also

remarkable for being one of the few Asian countries not to have experienced the

traumas of colonization by a Western power. By way of contrast, Thailand’s neigh-

bour to the northeast, Laos, was indeed subjected to Western colonization, and

formally came into being as the result of unnatural borders being created by treaties

between the colonizing power, France, and other countries in the region. One

particularly signiWcant eVect of such treaties was to strand almost 80 per cent of the

total ethnic Lao population within the borders of the northeast of Thailand, a

situation which remains to this day and which adds to the complexity of national

identity issues in both Thailand and Laos. Due to severe diYculties in internal

communication in Laos caused by mountainous terrain, as well as the presence of

substantial numbers of non-Tai ethno-linguistic groups in the country and the chaos

of a protracted post-colonial civil war, the development of national identity in Laos

has faced quite diVerent challenges to those in Thailand, and the success of establish-

ing a language-related unifying national identity is considerably less apparent than in

Laos’ larger neighbour to the southwest. Both countries, however, raise interesting

Thailand and Laos

392

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

and diVerent questions about the use of language in the process of nation-building and

the degree to which linguistic pluralism may or may not be possible within linguis-

tically diverse populations.

The structure of the chapter is as follows. Because an understanding of the present

linguistic situation in Thailand and Laos requires an appreciation of how these polities

initially evolved and were then deliberately formed as nation-states, section 18.2 begins

with a consideration of the development of the early Tai kingdoms into modern

nations, with a particular focus on the period of intense nationalism which occurred

in Thailand in the Wrst half of the twentieth century. Section 18.3 then concentrates on

the current situation of language–state relations in Thailand and the relation of Standard

Thai to the many other languages spoken in the country, as well as noting certain

changes which are beginning to manifest themselves. Finally section 18.4 returns to

Laos and focuses both on its recent colonial and post-colonial past, and the way that the

country has attempted to unify its many diVerent linguistic groups as a single nation.

18.2 Nation-building and the Construction of National Identity

18.2.1 From Muangs to Kingdoms

When the Tais initially migrated out of southern China and into the areas of modern

Thailand and Laos, they organized themselves in small groups of fortiWed villages

known as muang, which served as social, economic, and defensive units of organiza-

tion characteristic of Tai groups wherever these have settled. Later on in the thir-

teenth century, however, a number of larger kingdoms emerged, which connected up

the territories of the smaller, scattered muang. In the area corresponding to the north

of modern Thailand the kingdom of Lan Na (‘a million rice-Welds’) developed around

the centre of Chiang Mai, and to the east, in the area of modern Laos, the kingdom of

Lan Xang (‘a million elephants’) began to build together a signiWcant amount of

connected territory. To the south of Lan Na, a further, third kingdom appeared in the

large plain of central Thailand, and was known as Sukhotai. Although this latter

kingdom did not have a long existence, it is commonly portrayed as marking the real

beginning of the history of Thailand, and is described as being an important, golden

age in which the arts and culture Xourished, and the system of writing Thai was

signiWcantly invented.

Following the decline of Sukhotai, a much longer-lasting kingdom then arose to its

south, Ayudhya, and came to dominate the central plains area right up until the

eighteenth century. The kingdom of Ayudhya was particularly important because it

was here that a Tai social and political culture and population emerged which was

clearly diVerent from those in the other Tai kingdoms further to the north and east.

The Tai of Ayudhya adopted and adapted many sophisticated ideas concerning the

organization of state and society from systems developed in the powerful Khmer

kingdom of Angkor to the southeast. The kingdom of Ayudhya also had a more

Thailand and Laos

393

cosmopolitan make-up than Lan Na and Lan Xang, and incorporated many people of

Mon, Khmer, and Chinese descent as well as the dominant Tai. The blending of these

peoples within a highly structured society inXuenced by Khmer and Indic principles of

government led to a distinctive and ambitious Tai kingdom which neighbouring

powers began to refer to as ‘Siam’, introducing a name for the kingdoms of this

central plains area that would continue to be used (primarily by outsiders) until 1939.

Elsewhere, to the northeast of Ayudhya, the kingdom of Lan Xang also experienced

considerable development and a golden age in the seventeenth century, encompassing

most of the area of modern Laos and more. In the eighteenth century, however, Lan

Xang disastrously split up into three rival kingdoms, Luang Prabang in the north,

Vientiane in the centre, and Champassak in the south, and remained troubled by

W

ghting and competition between the three kingdoms right up until colonization of

large amounts of Lao territory by the French in the twentieth century. For much of

the last three centuries, the areas inhabited by Lao–Tai people have therefore suVered

from being disunited and have also been subject to periodic and regular subordination

by more powerful neighbours and invaders.

In its turn, Ayudhya also fell and was completely destroyed by the Burmese in 1767.

Out of the ashes of Ayudhya, however, quickly grew a new Siamese kingdom which

remarkably brought under its control more territory than had been governed by

Ayudhya, including Lan Na to the north, the Lao kingdoms of Luang Prabang,

Vientiane, and Champassak, Cambodia to the east, and various Malay states in the

south. With a new capital city founded in Bangkok and an aggressive policy of

expansion, the territory under Siam’s control subsequently came to take on more

of the administrative form of an empire rather than a kingdom, with the relation of

subordinate territories to the centre of power changing as the distance from Bangkok

increased. Those areas furthest away from Bangkok were less integrated in the

Siamese world and functioned simply as vassal states submitting annual tribute to

Bangkok. Other regions closer in and more closely bound to Siam also submitted

manpower for defence and construction works but were nevertheless still directly

ruled over on a day-to-day basis by local powerful elites. The important picture that

emerges then in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries is of a powerful

Siam governing an extremely diverse population, in which local rulers play an

important part in the hierarchical structure of the empire, and there is no uniform

sense of culture or identity/belonging within the widespread territories of the empire.

18.2.2 From Kingdoms/Empire to Modern State and Nation

Into this picture in the mid-nineteenth century then came a highly signiWcant new

pressure on Siam in the form of the advancing forces of the West, and the expansion of

British control in Burma and the Malay states to the south, and French expansion in

Indochina. Concerned that Britain and France might try to colonize Siam as well,

King Mongkut and later King Chulalongkorn responded with an eVective programme

394

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

of diplomatic accommodation in which new treaties both facilitated and improved

trading access for the Western powers and also conceded large amounts of peripheral

Siamese territory demanded by Britain and France. King Chulalongkorn began

reforming and modernizing the country in many ways, so as to project the image

of a civilized, stable modern state that the West could safely and proWtably conduct

business with without the need for colonization. In the process, Siam actually lost half

of the total territory it had previously controlled, but successfully avoided any

attempts by Britain and France at colonization of the heartland of Siam itself. This

loss of territory combined with Chulalongkorn’s dramatic reform of state bureaucracy

then had an important eVect on the way that Siam was internally governed. By

replacing the authority of local rulers with a new system of government ministries

with country-wide powers, Chulalongkorn eVected a tremendous centralization of

power, and from an empire-like situation in which the population of outer regions felt

constrained to give their allegiance to local ruling families, there emerged a new

modern state run by bureaucrats from Bangkok in which all of the population felt

governed by the same central state apparatus. Such a centralization of power would

not have been possible within the sprawling, vast, uneven territory of Siam prior to

the treaties, and now for the Wrst time established a modernized state with the

potential for country-wide uniformity and a new feeling of belonging to a single

national body. However, as noted in Bunbongkarn (1983), at that time: ‘National

consciousness, a psychological force which uniWes diVerent segments into a nation did

not prevail among the Thais in remote provinces although they were not ethnically

and culturally diVerent from those in the central plains.’ In order to consolidate the

new state of Siam and to legitimize centralized rule from Bangkok, it became

apparent that the notion of a shared national culture was now necessary.

The individual who spearheaded and championed Siam’s transformation from a

state into a nation, at least at the level of the growing new elite, was the new king

Vajiravudh, the Wrst monarch to have been educated in the West, where he had gained

considerable exposure to Western ideas of nationalism. Vajiravudh vigorously pro-

moted the idea of the Thai nation and indicated that the three most important

concepts to be upheld by inhabitants of the country were the Nation, Religion, and

the Monarch. Underlying Vajiravudh’s nationalism was a clear secondary desire to

protect and strengthen his own position as king. However, there also seemed to be a

genuine wish to generate a greater sense of unity and collective identity in the nation.

Potentially challenging such unity of identity, and another motivation for the new

calls for nationalism, was the identiWcation of an increasing Chinese ‘problem’ within

Siam, and two of Vajiravudh’s writings, ‘The Jews of the Orient’ and ‘Wake Up Siam’

were criticisms of the Chinese dominance of the economy in Siam. Prior to the 1920s,

large-scale Chinese immigration into Siam had not been perceived as particularly

disruptive or divisive, as the majority of the Chinese males who immigrated as

labourers subsequently married local Thai women and assimilated into Siamese

society. However, in the 1920s more and more Chinese women also immigrated

Thailand and Laos

395

into Siam and the incidence of assimilation became less and less. As the economic

power of the Chinese rose dramatically (to the point of controlling 80 per cent of

commerce within Siam), the non-integration of this sizeable foreign group, which had

grown to over 10 per cent of the population, came to be seen as a considerable

potential threat to the new unity of Siam, and so became a regular target of nationalist

speeches made by Vajiravudh.

Elsewhere Vajiravudh began the implementation of a drive towards a new, hom-

ogenized national identity with the introduction of schooling in a standardized form

of Thai based on the elite-spoken dialect in Bangkok. Literacy was taught through this

Standard Thai and signiWcantly it came to be used in place of other local scripts and

dialects. Vajiravudh was also keenly aware that the method of presentation of the

nationalist ide´e was critical for its wide success and depended on the careful manipu-

lation of language adapted for widespread consumption. He therefore ensured that

the language of his speeches and his plays was simple and easy to understand, so that

they allowed for eVective, large-scale dissemination to a broad nationwide audience.

The nationalist programme initiated by Vajiravudh was continued with increased

vigour by others in the 1930s. In 1932, aspirations for greater democracy amongst the

growing Western-educated elite led to the overthrow of the absolute monarchy and

the conversion of the country into a constitutional monarchy in which the king had

much reduced powers. In the decade that followed this, two individuals played a

particularly important role in the further development of nationalism and national

identity in Siam: Phibun Songkhram, a military oYcer who became prime minister in

1938, and Luang Wichit Wathakan, a writer and academic. The latter became the

Director General of the Fine Arts Department and used this institution to produce

and disseminate a mass of nationalist propaganda building up the myth of a single

Thai people with a long, uniWed history. This took the form of stirring historical plays,

songs, and musical dramas which were widely broadcast on the radio and performed

throughout the country by a new national acting and dance troupe established by

the Fine Arts Department. The dramatic increase of published materials available in the

1930s also assisted greatly in the spread of Wichit’s nationalist propaganda, as did the

growth and availability of compulsory education, which was critically transmitted by

the use of Standard Thai alone. School children throughout the land consequently

received the same curriculum of ‘national’ history and culture in the same ‘national’

language, and furthermore had to adopt that language in order to proceed through

the educational system. Through the 1930s the public, young and old, were therefore

constantly exposed to the idea of a Thai national identity in a far more extensive way

than in Vajiravudh’s reign, and the government-endorsed promotion of a unifying

national culture successfully embedded the idea of a single Siamese/Thai nation

among signiWcant numbers of people in the country.

From 1939 on, the government led by Phibun then issued a series of State

Conventions (Barme´ 1993: 144–60, Wyatt 1984: 252–6) which both announced oYcial

new ‘national’ policies and also urged various changes in behaviour by the public in

396

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

relation to common national objects and the national image. In the Wrst State

Convention announced by Phibun on National Day 1939, it was declared that the

name of the country was oYcially being changed from Siam to Thailand (in Thai from

prathet Sayam

to prathet Thai). The word ‘Thai’ had long been in use to refer to the Tai

people living in Siam, but ‘Siam’ had been conventionalized as the name of the country

in treaties and other dealings with foreign countries. The motivations ascribed to the

change in oYcial name were that Wrst of all it emphasized that the Tai, and not the

economically dominant Chinese, were the real owners of the country, and secondly it

highlighted the common Tai linking between the inhabitants of Siam and the ethnic-

ally Tai peoples in neighbouring countries, in particular French-occupied Laos. Ever

since the ‘annexation’ by France of Lao territories previously controlled by Siam, there

had been a desire to seize back these ‘lost provinces’, and with the accelerated rise of

nationalism in the late 1930s, Wichit, Phibun, and others began to imagine a new pan-

Tai empire led by Thailand, uniting Tai peoples in Laos, Burma, and possibly even

further aWeld. It was also publicly noted that the word ‘Thai’ had the additional

meaning ‘free/independent’ and that this well matched the fact that Siam/Thailand

was the only non-colonized/independent country in eastern Asia apart from Japan.

Following on from the change of the name of the country from Siam to Thailand,

the government proclaimed in a second State Convention that all the inhabitants

of Thailand would now be referred to as Thai (people), however they may have

previously called/identiWed themselves. Long-standing ethnic identity labels were

therefore replaced by ‘a new, oYcially sanctioned historical-cultural identity’

(Barme´ 1993: 151), and it was even ordered by Wichit that ethnic terms such as

‘Lao’ and ‘Shan’ should be replaced in current and traditional popular songs by the

word ‘Thai’. The fourth State Convention also discouraged the use of any regional or

ethnic/religious modiWer of the word ‘Thai’, so that terms such as ‘southern Thais’,

‘northeastern Thais’, and ‘Islamic Thais’ should not be used, and instead all inhabit-

ants of the country should be simply referred to as ‘Thais’ in a fully uniform way.

In 1940 the government then proclaimed a State Convention on Language, and

announced that: ‘All Thais must consider their Wrst duty as good citizens is to study the

Thai language, so that at least they must be able to read and write. . . . Thais are not to

give undue consideration to their particular place of residence or their birth-place or to

the diVerence in accent of the language as indicative of separation. Everyone must

consider that he is born Thai, he naturally possesses Thai blood and talks Thai

irrespective of birth-place or pronunciation.’ (Quoted in Barme´ 1993: 155.) This

particularly targeted groups which spoke non-Tai languages, such as the Chinese and

the Malay-speakers in the south. It also essentially instructed speakers of Lao and other

Tai-varieties that they had a civic duty to learn Standard Thai and that they should

consider themselves to be bound to the nation by their knowledge of and ability in Thai.

In their push for a new national unity, what many of the Conventions eVectively did

was to promote the culture and language of the most powerful ethnic group in

Thailand, the Thais living in the central area of the country, and there was a clear

Thailand and Laos

397

attempt to smother (or at least fail to acknowledge as signiWcant) the existence of

other cultures and languages within the country. Reacting in particular to the

perceived ‘threat’ to national identity posed by the Chinese, who were seen to be

increasingly sympathetic to the growing nationalism in China (heightened by the

invasion of China by Japan in 1937), the Thai government closed down large numbers

of Chinese schools and stopped the printing of Chinese newspapers, considerably

impeding the successful transmission of Chinese to the younger generation, and

triggering a long-term process of language shift from Chinese into Thai (Morita 2004).

Further State Conventions aimed at modernizing the public image of Thailand, by

calling upon people to dress in a civilized way (with men encouraged to wear coats,

shirts, and ties, and women hats and gloves), and at instilling respect for symbols of

the nation such as the national Xag and the national anthem (with citizens being

required to stand at attention in public places whenever the Xag was raised or lowered

to the playing of the national anthem).

Finally, the irredentist movement reached its peak in 1940/41, when Thailand went

to war with France to retrieve the lost provinces of Tai speakers in Laos that had

belonged to Siam in the nineteenth century. During this period of high nationalist

fervour which received wide and ardent support from the public, the Thai Depart-

ment of Defence even went as far as to assert that Laotians, Khmers, and Vietnamese

were ‘of the same nationality’ as the Thai and were distant (younger) siblings being

rescued from the oppressive colonial domination of France (Reynolds 1991b).

18.2.3 From World War II to the Present: Defending the National Identity

Following the end of World War II and a brief period of occupation by Japanese forces,

the Thai government continued on with its programme of promotion of the ‘national’

identity through the advancement of central Thai language and culture. Phibun

initiated a fresh campaign against the Chinese, with new restrictions on Chinese

participation in the economy, further reduction of the possibility of use of Chinese

within education, and a near halt on immigration from China. In the south of

Thailand, the army and the air force were called in to put down resistance from

Muslim Malay speakers to the imposition of the State Conventions on language and

behaviour, and education in Malay came to be forbidden. Later on, in the 1960s and

1970s the country experienced further internal unrest in a period of insurgency which

was centred in the northeast of the country and associated with communists and

foreign support from Indochina. All throughout this time, the notion of a uniWed

national culture was strongly transmitted by the government through education and

the media, and ‘traditional’ values and institutions were championed as being of great

necessary importance for the country and its people. Though internal resistance to

the state homogenization of language and culture did occur in parts (e.g. in the far

south and for a time in the northeast), generally there was passive acceptance of the

state’s promotion of a national Thai image and identity, and also much enthusiasm for

398

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

it in certain areas, especially when the monarch was reintroduced and vigorously

promoted as a major symbol of national unity from the 1960s onwards. Critical in the

post-WWII (further) state engineering of a national Thai identity and its acceptance

by the population was the fact that Thailand underwent an economic boom from the

mid-1960s until the 1990s and stood out as the modernizing success story of southeast

Asia, fuelled by much US aid and military presence during the Vietnam war years. The

inhabitants of Thailand therefore came to experience a certain collective pride in the

progress of their country when compared with that of their neighbours, and this was

continually bolstered by the observation that Thailand had maintained its independ-

ence when all those around it had succumbed to Western colonization. The idea of

belonging to a single, successful nation was therefore easier to instil amongst the still

varied population as Thailand indeed seemed to be a nation which was prospering like

other ‘real nations’ elsewhere in the world.

Considered as a whole, the history of Thailand can be seen as the incremental

consolidation of a modern nation through a series of fairly discrete, segmentable

stages. Out of an initial period in which the area of modern Thailand and Laos was

occupied by numerous small, disconnected muang there emerged a number of

diVerent Tai kingdoms with a more clearly deWned, broader area of domination.

Amongst these, the kingdom of Ayudhya developed a particular sophistication in its

internal structure when adopting organizational principles from neighbouring Angkor

and the Khmers, and handed these on to the Thonburi/early Bangkok kings who

subsequently expanded the kingdom into an empire Wlled with many, diVerent

peoples. Governed directly by local rulers, there was little collective feeling amongst

such peoples or loyalty to the centre. Pressure from the West, however, forced a

reduction of territory in the empire and an eVective redeWnition of the internal

structure of the core of Siam as a modernizing state with strong centralized control

and elimination of the power of local rulers, but still no coherence as a nation with a

common identity. This identity as a nation has now been carefully forged and

constructed over the last hundred years by elite-driven policies focusing on the

advancement of central Thai language and culture, and a downplaying of regional

and other ethno-religious diVerences present in the country. The current results of

this process of the promotion of a dominant language and national identity and the

present status of Standard Thai and the many other languages which continue to be

heard in the country are now considered in section 18.3, postponing an examination

of the rather diVerent development of the linguistic situation in Laos to section 18.4.

18.3 Language and National Identity in Contemporary Thailand

18.3.1 The Dominance of Standard Thai

Since King Vajiravudh’s initial directives that Standard Thai should be used in school-

ing throughout the country, eighty years of eVorts in national language promotion

Thailand and Laos

399

have resulted in Standard Thai coming to hold an extremely prominent and dominant

position within Thailand. Standard Thai is a form of Central Thai based on the variety

of Thai spoken earlier by the elite of the court, and now by the educated middle and

upper classes in Bangkok. It incorporates many words of Pali and Sanskrit origin

(which are still used as source languages for the creation of new terminology), was

standardized in grammar books in the nineteenth century, and spread dramatically

from the 1930s onwards, when public education became much more widespread and

available.

Currently, Standard Thai is widely understood, primarily due to its dominance in

various areas of life. In the domain of education, it is oYcially decreed that all public

schooling has to be provided via the medium of Standard Thai, throughout the

country. Standard Thai also dominates the media, with the vast majority of television

and radio programmes being broadcast in Standard Thai, reinforcing its national

presence. It is also the oYcial language of government business, public speaking, and

functions as the language of economic advancement and social prestige (Diller 1991).

Finally, it is associated with a written form which has a long history and literature and

which is extremely visible throughout Thailand, having fully displaced other regional

forms of writing used until the mid-twentieth century. Because of its dominant

presence and continual promotion through the media and education, Standard Thai

is also perceived as an important national symbol, and alongside Theravada Buddhism

and the King is suggested to be one of the strongest symbols of national identity

present in the country, even for speakers who rarely use it in everyday life (Smalley

1994: 14).

18.3.2 Regional Tai Languages

While Standard Thai is indeed heavily dominant in education, the media, commerce,

and oYcialdom, many other languages are also widely spoken in Thailand in other

domains of daily life. These can be usefully divided into the major regional languages,

which are also Tai languages, and various other non-Tai languages spoken by about 10

per cent of the population in more scattered areas.

Standard Thai being a language which is primarily learned in school (or via the

television/radio), the vast majority of the population actually grow up speaking some

other language at home, and for nearly 90 per cent, this will be a form of one of

the four main regional languages. These are Central Thai, spoken in the area of the

central plains (including Bangkok), Northern Thai (also known as Kammuang, the

language of the old kingdom of Lan Na), Northeastern Thai (also known as Isan or

Lao), and Southern Thai (also known as Paktay). In their grammar, pronunciation,

and lexicon, these four varieties are about as diVerent from each other as members of

the Romance or Germanic family of languages, and are not mutually intelligible,

though speakers of one variety will feel that the other varieties are certainly related to

it and are not foreign languages in the way that Chinese or English are. The closeness

400

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

of the regional languages to Standard Thai is furthermore suYcient for texts written

in Standard Thai to be read aloud with the distinctive phonology of the regional

languages. Due to the general prominence of Standard Thai, more and more words

are being borrowed from Standard Thai into the other languages, especially by the

young, who are more competent in Standard Thai, and also when new technical

vocabulary has Wrst been coined in Standard Thai.

Amongst the four regional languages, a special word needs to be said about

Northeastern Thai/Isan. Historically, the northeast part of Thailand, which is

known as Isan, was Wrst part of the successful Lao kingdom of Lan Xang, and then

part of the smaller Lao kingdom of Luang Prabang. It was only one hundred years ago

that Isan actually became an oYcial part of Siam as the result of treaties signed with

the French which incorporated this ethnically Lao area into Siam. For the majority of

its history, therefore, Isan has been a Lao area more closely connected with the

population in modern Laos than with the Thais/Siamese. Although Thai and Lao

language and culture have much in common, the people of Isan are nevertheless

closer in their sub-variety of Tai language and culture with the inhabitants of modern

Laos, and the language which the people of Isan speak is indeed referred to as either

Isan or Lao, with the Thai government often dispreferring the latter term as it stresses

the potential link between the people of Isan and the modern state of Laos. This

ethnic and linguistic aYnity of the people of Isan with the Laos across the border

raises questions about loyalties and national identity which we will return to in

section 18.4.2. It should also be noted that the number of Isan/Lao speakers in

northeast Thailand is substantial and as much as a third of the total Thai population.

The balance of Lao speakers in Thailand and Laos is also quite uneven and perhaps

the opposite to what one might expect, with only 20 per cent of the total number of

Lao speakers living in Laos, and the remaining 80 per cent all being resident in Isan

(an indication of the arbitrariness of the borders of Laos established by the French

with the Siamese government).

18.3.3 Non-Tai Languages in Thailand

In addition to the Tai majority population (90 per cent), a large number of non-Tai

languages are spoken by the remaining 10 per cent of the population of Thailand. These

can be divided into two basic groups deWned in terms of the amount of time their

speakers have been present in the country: (a) ‘early residents’, and (b) ‘late arrivals’.

When the Tai people originally migrated into the area of modern Thailand, there

were already there scattered groups of speakers of Mon-Khmer languages, and

speakers of these languages continue to be present in the country. Many of these

groups descended from early residents of Thailand are now considerably small in size

and assimilating to the dominant Thai culture, with accompanying full loss of the

original language and cultural identity (Premsrirat 2001).

Thailand and Laos

401

The second group of ‘late arrivals’ into Thailand are speakers of a broad range of

Sino-Tibetan and Hmong-Mien languages (amongst which Karen, Akha, Lahu, Yao,

and Hmong) who migrated into north and northwest Thailand from the middle of

the nineteenth century. Because these people generally live at higher altitudes than

the Thai lowlanders, they have come to be referred to as the Hill Peoples/Tribes.

Traditionally, they tend to live by swidden farming which results in a migratory

pattern of life and the necessary search for new farming land every few years. Many

of them now also engage in the cultivation of opium as a cash-crop.

Because of the growth of the population in the upland areas and the reduction in

the amount of land available for swidden-style agriculture, these peoples have recently

had increasing contact with the lowland Thais and a number of them are coming to

acquire a secondary competence in either Standard or Northern Thai. Though

comparatively small in total number (650,000), the hill people are considerably visible

in Thailand, due in part to use of the ethnic diversity of the hill peoples in the

promotion of international tourism in Thailand, and also due to regular television

news footage of the king touring the area of the hill people. The king has been

concerned with alleviation of the poverty of the hill people and Wnding ways to

improve their income without the cultivation of opium. Generally, it is felt that the hill

peoples have not integrated themselves with the majority Thai culture, and there are

frequent negative attitudes towards the hill peoples as outsiders who are destroying

the forests of Thailand in order to produce opium.

18.3.4 The Chinese and the Sino-Thai

Two further non-Tai language groups residing in Thailand which deserve special

mention because of their links to (non-)assimilation and identity issues are the mainly

urban Chinese and the southern Malay-speakers.

As noted in section 18.2.2, both king Vajiravudh and Phibun saw the growing

identity of the economically dominant Chinese population with nationalism in China

rather than Siam as a potential threat to national unity, and moved to force greater

integration of the Chinese into the emerging Thai nation. This was essentially

achieved in two ways, Wrst, and most immediately, by economic measures which

made it signiWcantly more diYcult and costly for non-Thais to engage in commerce in

Thailand, and second through the eVective control of Chinese language in education,

a longer-term but nevertheless highly eVective means of stimulating integration.

Following the decree that all schools follow a standard Thai curriculum, there was

mass closure of private Chinese schools in the Phibun era, and new generations of

ethnically Chinese children began to experience their daily education in Standard

Thai, being presented with images of Thai culture and history rather than learning

Chinese language, culture, and history.

The result of so much sustained pressure on the Chinese community has been a

dramatic assimilation of the Chinese into Thai society. From the Phibun era onwards

402

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

there was increased intermarriage of Chinese men with Thai women, this producing

oVspring who grew up hearing and learning more Thai than Chinese. In order to

maintain their prominence in business, many Chinese also adopted Thai names and

Thai manners. Now, nearly seventy years since the economic and educational meas-

ures to encourage integration were put in place, the Chinese in Thailand have evolved

into a much more blurred community referred to as Sino-Thai, with 15–20 per cent of

the total Thai population being estimated to have signiWcant Chinese heritage. The

Sino-Thai are for the most part people who have a memory of being partly Chinese,

but whose daily life may involve Thai language and culture signiWcantly more than

Chinese, and there has been a signiWcant and clear loss in the ability of younger

generations to speak Chinese (Morita 2004). In comparative terms, the ‘Chinese’ in

Thailand are commonly described as showing the highest degree of assimilation that a

Chinese community has undergone anywhere in southeast Asia.

18.3.5 The Malay-speaking Muslims of the South

A strong contrast to the extensive assimilation of the Chinese is represented by

the weakly-integrated status of the Malay-speaking Muslim population living in

Thailand’s four southernmost provinces near the border with Malaysia. Numbering

approximately one million, these Malay speakers inhabit a set of territories which

were previously independent Malay states and which were fully incorporated into

Siam only in the nineteenth century. Being ethnically, historically, and linguistically

Malay rather than Tai, and by religion Muslim rather than Buddhist, the population

here continues to be signiWcantly distinct in many ways from that of the rest of

Thailand, and many amongst the Malay speakers feel that they have much more in

common with the inhabitants of Malaysia to the south than with the Thais to the

north.

Being very much aware of the obvious diVerences between the Malay-speaking

population of the south and the national identity promoted elsewhere in the country,

the Thai government of the Phibun era made vigorous, heavy-handed attempts to

assimilate the Malay speakers during the 1940s and 1950s. This, however, was met

with strong resistance and little success, unlike the successful assimilation of the

Chinese. Since the 1960s a more sensitive approach to the Malay-speaking south has

been adopted, but there has nevertheless been continual government pressure on

both language and schooling in the region, and a refusal to accept the existence of the

term ‘Malay’ as an ethno-linguistic label for reference to this group, oYcially replacing

the term ‘Malay-Thai’ with ‘Muslim-Thai’ as a designation of the population there.

Paralleling their approach to private Chinese schools, the government also insisted

that education in the Malay-speaking area be carried out in Standard Thai by teachers

with state-recognized teaching qualiWcations. Because most of the traditional Malay

teachers in the religious schools did not have the necessary state qualiWcations and

were also not proWcient in Thai, this resulted in their forced replacement by other

Thailand and Laos

403

Thai instructors, and the face of education in the Malay-speaking south changed

considerably, with the younger generation coming to be taught in Thai and exposed

to the national Thai culture on a much more regular daily basis than before.

However, despite the institutionalization of the Thai language in the Malay areas,

there has been only mixed success in the government’s hoped-for integration of the

Malay-speaking population, this occurring largely in the western provinces of Nar-

athiwat, Yala, and Sathun. In the eastern province of Pattani, there is still a widespread

feeling of not properly belonging to the Thai nation and its dominant culture, and

there is also resentment at the attempts of the government to control the use of Malay

in schools, Malay language being perceived by the inhabitants of the area as an

important component of their identity, alongside Islam and a Malay ethnic social

structuring diVerent from that of Thai society. Since the 1960s there has also been

periodic terrorist activity in the south, carried out by groups demanding independ-

ence for the Malay provinces. Though this has not attracted much in the way of broad

support from the population and has been sporadic in nature, in 2004 there was a

worrisome increase in the violence, and currently, the situation is quite volatile again.

Although there had been signs that more of the younger generation were beginning to

develop less negative attitudes towards Thai language and culture than in the past,

presently there is still a considerable feeling amongst much of the Malay-speaking

population that they are generally not treated as equal partners in the Thai nation and

its ongoing development, and are discriminated against on the basis of their language,

culture, and religion. Such perceptions are exacerbated by the poverty and under-

development of the region, and an increased Islamic revival on both sides of the

border of Thailand and Malaysia has also served to heighten the feeling of diVerence

between the Muslim Malay speakers and the predominantly Buddhist Thais further

north. The situation in the borderlands of the far south of Thailand therefore

continues to pose a challenge to the promotion and portrayal of a uniWed Thai

identity based on language, religion, and culture.

18.3.6 The Overall Picture

Considering the broad patterning of language use in Thailand, and abstracting away

from the special case of Malay described above, the general picture which emerges is

that of a single heavily dominant language (Standard Thai) occurring alongside an

array of other languages in a stable, diglossic-type situation: Standard Thai is used for

H-type functions, and either regional Tai languages or non-Tai minority languages are

used for everyday L-functions. What is often held to be remarkable about this

situation and Thailand in general is the surprising absence of resistance and protest

against the public dominance of Standard Thai. In other multilingual countries where

a single language has come to be dominant in such a way, there have frequently been

strong negative reactions and violent opposition by speakers of languages which have

been marginalized in the process, yet with the exception of unrest in the Malay south,

404

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

this does not seem to have happened in Thailand. The interesting question is therefore

why this might be.

The answers which can be given here are many and various and it is commonly

assumed that a conspiracy of factors has resulted in the current, generally unchal-

lenged position of Standard Thai. First, there has been no attempt to fully suppress

other languages in Thailand, and though Thailand is not a linguistically pluralistic

society in the way that Switzerland, Belgium, and Singapore are, it has always allowed

for the free use of Thailand’s ‘other’ languages in daily life. Second, a signiWcant 90 per

cent of the population actually speak a Tai language as their Wrst and home language,

and speakers of regional forms of Thai feel that their languages are clearly related to

Standard Thai. The latter is therefore not some foreign imposition or the language of

an obviously diVerent ethnic group. Third, the nationalist programme of promotion

of a national identity has in many ways been successful and instilled a clear sense of

national pride and belonging among the population of Thailand, and Standard Thai is

one (important) manifestation of this national identity. Fourth, the complications

introduced by the presence of a Western colonial language have not aVected Thailand,

and this has made it easier to promote a local variety of language as a national

standardized form. Fifth, for the ethnically non-Tai 10 per cent of the population,

there are clear pragmatic incentives for accepting the national dominance of Thai

language and culture, and Smalley (1994) reports that most minorities living along

Thailand’s borders see their future as economically brighter within Thailand than

within a neighbouring or independent new state (hence, Thailand’s Khmer popula-

tion show no signs of wishing to be absorbed into neighbouring Cambodia, and the

Shans in the north of the country have not joined those in Myanmar in their calls for

an independent Shan state). Finally, it is also sometimes suggested (Premsrirat 2001)

that people in Thailand accept the dominance of Standard Thai because hierarchical

relations of dominance are generally common within Thai society and control a range

of aspects of life in the country.

It can furthermore be noted that the general absence of language-related problems

in Thailand and the acceptance of some kind of national identity requires one to

understand that ‘national identity’ in Thailand may be adopted in two rather broad

ways. The Wrst can be characterized as self-identiWcation as Thai, through having the

prototypical properties ascribed to members of the Thai nation – speaking a form of

Thai, being Buddhist, conforming to Thai culture, and respecting the monarchy, etc.

This form of national identity permits a potentially strong and deep loyalty to the

nation, and is the kind of feeling deliberately fostered by the nationalist programme.

A second form of national identity, however, which is a weaker and potentially

more temporary form of allegiance is the identiWcation of Thailand as one’s appro-

priate homeland, and the feeling that Thailand is the place where one belongs, where

one can best be happy and prosper. The Wrst form of national identity is more easily

open to and adopted by those who are ethnically Tai in the country, and is bolstered

by feelings of pride that Thailand has been more successful than its immediate

Thailand and Laos

405

neighbours in recent economic development and international standing. The second

more pragmatically driven form of national identity is more regularly characteristic of

the non-Tai minorities in Thailand, who possess less of the typical properties of Thai

culture. Both types of allegiance to the country importantly underlie the relative

stability of Thailand in the present age and have led commentators such as Smalley

(1994) to talk of striking ‘national unity amongst linguistic diversity’.

18.3.7 Signs of Change in Recent Times

It is fairly clear that from the 1930s through until at least the 1970s the issue of national

identity has been closely linked with that of national security (Reynolds 1991b: 9).

UniWcation of the country via a shared language and culture was seen as a means to

ward oV the possibility of separatism and fragmentation of the state. The government

therefore spent much time and energy in setting up oYcial organizations such as the

Ministry of Culture and the National Identity Board to stimulate the growth of a Thai

national identity. In recent years, there has been a signiWcant reduction in potential

challenges to national security, yet the level of concern about Thai national identity

remains very high and there is constant public discussion of identity issues. This now

raises the question of why this should be so, and what there is in the modern climate

which should continue to make national identity a topical, hot issue in Thailand. In

addition to this, it is possible to note that there are many changes which are occurring

in relation to the perception and status of previously non-prestige languages and

culture. Here we will Wrst look at what these changes are, and then discuss why they

may be occurring, as well as how this relates to issues of national identity.

The interesting new development that has become more and more visible in the

last ten years is that there is a clear regrowth of interest in regional language and

culture, as well as Chinese, and a revival of languages that previously were sidelined

during the promotion of the national language. In the north of Thailand, for example,

people have been starting to learn how to write Kammuang again in the Lan Na

kingdom script form which was eliminated by the oYcial spread of Standard Thai.

This new ability to write the regional language in its original script complements the

ability of people to speak Kammuang and is being acquired in schools, language clubs,

and via private tuition. In the northeast of Thailand, a new pride in Isan/Lao is

appearing, and the language is now being taught as a subject in various schools and at

university level, together with courses on Isan literature and Isan dialects (Draper and

Chantao 2004). Elsewhere other local languages are starting to be taught in schools

where there are motivated teaching staV and this receives the approval of the school’s

director. Consequently, though Standard Thai was until quite recently the only

language permitted in education, now there is a clear relaxation of government policy

in allowing the teaching of other languages (though basically as subjects not as the

medium of instruction in state-run schools), and there is also an obvious new interest

in the learning of local/regional languages.

406

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

In addition to a revival of interest and pride in regional/local languages, there has

been renewed interest in learning Chinese and appreciating Chinese culture. Chinese

is now oVered as a subject in government schools and universities, and is being

promoted as a language useful for business, as contact and trade with China increases.

In terms of public image, the learning of Chinese is also well endorsed by the fact that

the Thai crown princess has sponsored a centre dedicated to the study of Chinese

language and culture at Mae Fa Luang University and herself has studied Chinese

language, calligraphy, and music, and even written books about China.

Quite generally, government politicians are also now publicly seen adding their

support to new initiatives promoting the teaching and use of local languages, and this

is reported in the media and shown on television. In the north of Thailand, local

authorities have encouraged people to use Kammuang both in everyday life and

sometimes in public speaking/broadcasts where Standard Thai would previously only

have been used (for example, public broadcasting in Kammuang was encouraged

during the traditional new year festival in Chiang Mai). On television and public

billboards too there is a clear increase in the variety of local language and dialects that

are used in commercials and the advertising of local products.

A Wrst question about these new developments is what is allowing for these

changes to occur, particularly within the educational system which has all along

been so closely guarded and directed by the government? The important o

Ycial

change has been that a new constitution introduced in 1997 has resulted in less

direct, centralized control of various aspects of life within Thailand, and allowed for

the development of decentralized local approaches to education and other issues via

the use of ‘local wisdom’. This change in government attitude which now allows for

and even encourages the preservation of cultural diversity for the beneWts it may

bring to the nation has technically permitted the introduction of regional and local

languages into schools within the new ‘local wisdom/local culture’ part of the

curriculum.

As to why these changes are occurring, the fundamental cause seems to relate to

the issue of identity in a changing, modernizing, and more aZuent Thailand. Both

the populace and the government are showing themselves to be seriously concerned

by the eVects of modernization, globalization, and Western inXuence on the life-

styles of the young and the growing, more aZuent middle class. The latter have been

seen to be adopting more commercially available symbols of a Western identity and

critics from both the public and the government have warned that many within

Thailand are in danger of losing their Thai identity. Such concerns rather than issues

of national security have resulted in the continued public discussion of national

identity in recent years, and the regrowth of local culture and language (‘local

wisdom’) seems to be occurring as a response to the cultural threat posed by

modernization and globalization. It can also be noted that the economic crisis of

1997 resulted in certain anti-Western sentiment among parts of the population, as

the crisis was perceived to have been precipitated by the West. The hardships and

Thailand and Laos

407

confusion which ensued led to considerable soul searching in Thailand and a back-

to-Thai/Asian-basics attitude incorporating the idea that Thailand would best be

served by not depending on outsiders and the West. There was much discussion of

achieving sustained development, of reviving traditional knowledge, and the country

saw a wide revival of much earlier culture and practices. Thailand therefore redis-

covered much of the cultural diversity which had been ignored for many years.

The new freedom allowed by the constitution of 1997 consequently arrived at a very

opportune time, allowing people to indulge their desires in promoting, learning, and

using traditional language and culture, which was signiWcantly permitted to be

regional rather than just oYcial national language and culture. Chinese language

and culture were also seen as representing valuable Asian values which were

potential alternatives to Western culture, and there have appeared numerous recent

writings by Sino-Thais which exhibit a new-found pride in Chinese ancestry and

connections.

In addition to the above, various other perceived beneWts of the new revival of local

language and culture have stimulated its regrowth and visibility. Jory (2000) notes that

local politicians are beginning to make use of the expression of a regional identity to

win regional votes, that regional language and culture is being increasingly used in

advertising and seen to be an eVective marketing tool (because there are consumers

newly proud of their regional heritage), and that those involved in the tourist trade are

promoting regional diVerences in culture in order to attract both international and

(more and more) domestic tourists. Finally, it can be suggested that Thailand is

consciously following a global trend present amongst economically developed coun-

tries to protect and encourage indigenous minorities as sources of national cultural

richness, and that members of the government feel that Thailand will accrue a certain

esteem at the international level by participating in such egalitarian, liberal policies,

which are regularly associated with advanced economies.

Generally the fact that the government is prepared to let local languages grow

within the educational system and elsewhere is both a healthy and positive sign, and

also a clear indication of the conWdence that the government has in the basic strength

of the national identity. After years of careful promotion and reinforcement the latter

is now really very solidly grounded within Thailand (even if certain of the younger

generation do adopt Western fads and fashions), and expected to survive even when

placed alongside other revived local forms of language and culture. It should also be

noted that the current growth of interest in regional symbols of identity is not

perceived as a direct threat to national identity, as there are no obvious attempts

being made to replace the latter with new regional identities, and current changes are

rather moves to enrich the basic Thai national identity with additional local resources.

Certainly for the moment, national and regional identity are operating on diVerent

levels of hierarchical structure and are not in direct competition with each other. The

way this new relationship further unfolds and develops in the future will be interest-

ing to observe.

408

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

18.4 Laos in the Twentieth Century

18.4.1 The Development of Modern Laos and its Linguistic Groups

As noted in section 18.2.1, the Lao people in early and pre-modern times experienced

periods of both unity and division: initially being part of a single Lao Kingdom, Lan

Xang, from 1353–1694, the Lao later found themselves divided into three separate

rival kingdoms for two hundred years, until the arrival of the French, who established

the country’s modern borders in the twentieth century. The French originally arrived

in the area of Laos with the hope of Wnding a valuable new trading route to China, but

then seemed to lose interest in Laos’ potential and did not develop the country as they

did other colonies and protectorates. Following the end of World War II, Laos was

declared formally independent, but French military forces nevertheless remained, and

retained control of Lao foreign policy until 1954. The post-WWII period until 1975

was a time of continued internal division, with an armed leftist revolt against the new

government of Laos leading to civil war. This culminated in 1975 with victory by the

communist Pathet Lao forces and the creation of a new socialist state. Due to the

ensuing unpopular introduction of collective farms, the conWscation of property from

the wealthy, and a declining economy, as much as 10 per cent of the population then

X

ed the country as refugees, including most of the country’s educated and skilled

workers. In more recent years, however, the government has turned to a more relaxed

policy of pragmatic socialism and replaced its close links with Vietnam and the Soviet

Union with a rather diVerent orientation towards trading partners such as Australia,

Japan, and Thailand.

Currently, the population of Laos stands at 6 million, making it the least populated

country in the region, and also the most sparsely populated southeast Asian country,

with its inhabitants spread far and wide over a large area of mountains, forest, and

plains. Despite its comparatively small population, Laos is estimated as having one of

the largest numbers of diVerent ethnic groups in Southeast Asia. Formally, these are

classiWed as belonging to one of three basic groups whose naming reXects the type of

geographical terrain generally inhabited by members of the group – either the

lowland areas, the middle slopes of hills and mountains, or the highlands (hence

Lowland Lao, Midland Lao, and Upland Lao). The three-way categorization also

correlates with two other properties of the diVerent groups: (a) the language family

which the group belongs to, and (b) the time of arrival into the country of the group.

The Lowland Lao (Lao Lum) make up 65 per cent of the population and are Tai by

descent, having migrated into the area of modern Laos some time between the

seventh and thirteenth centuries. The Lao Lum have dominated the area of Laos

for most of its history and still continue to do so, and commonly refer to themselves

simply as ‘Lao’. The second group, comprising 25 per cent of the population, known

as the Midland Lao (Lao Theung) inhabit the middle slopes of Laos’ hills and valleys.

The Midland Lao are assumed to be the original inhabitants of the area and speak

Thailand and Laos

409

a large number of diVerent Mon-Khmer languages, with a total of thirty-seven

diVerent ethnic groups being categorized as belonging to this Midland Lao group.

The Midland Lao have often been looked down upon by the Lowland Lao and were

formally known as Kha ‘slaves’. The third division of the population is referred to as

the Upland Lao (Lao Soung), living mostly in the hills. Although the Upland Lao are

only 10 per cent of the total population, they are ethnically more distinct from each

other than the members of the other two groups, and consist in at least six ethnic

groups which migrated into Laos from China during the last 250 years. Speaking a

range of Sino-Tibetan languages (e.g. Hmong, Akha, Yao), they are strongly inde-

pendent people and are reported to feel themselves superior to the Lowland Lao, this

causing diYculties for national integration of the two groups.

18.4.2 Issues of Language and National Identity

Turning now to issues of language and national identity in modern Laos, in the two

hundred years prior to the twentieth century there was very little unity in the area

occupied by the Lao and certainly no single national identity, as the area was split up

into three separate kingdoms (which furthermore served as dominated vassal states to

other more powerful neighbours). The Wrst time that eVorts were made to instil

feelings of belonging to a single nation came during the late French colonial period

during World War II when the irredentist movement in Thailand was suggesting that

Laos should be annexed into Thailand. In order to counter claims from Thailand that

the Lao were very closely related to the Thai and so should be part of an enlarged Thai

nation, the French launched a nationalist campaign to attempt to create feelings of

national unity in Laos, and an identity distinct from that of the Thais. The campaign

included performances of Lao music and dance, the promotion of Lao literature, the

production of the Wrst Lao newspaper, and frequent rallies and parades all aimed at

convincing the population that it had a single, shared, national identity which was

grounded in a common history, unique culture, and shared language. It was also

continually stressed that this identity was signiWcantly diVerent from that of the Thais,

and speciWcally Lao. What such nationalist propaganda did was eVectively to take the

culture and language of the Lowland Lao alone and present this as the ‘national’

identity, suggesting that it characterized all of the large country and bound people

together in a unique way. Though this obviously was not true, given the diversity of

the population, there was nevertheless an anticipation that members of the other

ethno-linguistic groups could somehow be assimilated to the majority Lowland Lao

identity (Ivarsson 1999). However, despite the provision of more resources than in the

past, the programme of nationalism initiated by the French had no serious time to be

implemented on a nationwide scale and the peace of the country was soon inter-

rupted by prolonged internal conXict, continuing until 1975.

When the new socialist government established itself in 1975, there were clear

renewed attempts to create a feeling of national unity and identity among the diverse,

410

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

scattered population of Laos. One of the important, formal steps taken at this point

was the introduction of the three-way classiWcation of the population of Laos into

Lowland Lao, Midland Lao, and Upland Lao. The rationale for this kind of categor-

ization was that the use of geographical terms to label and encode diVerent groups

avoided the use of potentially more divisive labels based on fundamental diVerences of

language and culture (for example, a three-way grouping of Lao vs. Mon-Khmer vs.

Sino-Tibetan, or an even Wner-grained categorization according to the names of

individual languages). Such labelling was therefore an attempt to downplay the

diVerences of the population by grouping them simply according to which part of

the geographical landscape they inhabited. The use of the preWx ‘Lao’ in Lao Lum,

Lao Theung, and Lao Soung also endeavoured to indicate that there was a single ‘Lao’

cultural-identity component present with all of the three groups and hence a shared

national identity. Such labelling has, however, not been taken kindly to by various of

the Midland and Upland Lao because it obliges them to use the ethnic term ‘Lao’ in

self-reference and groups such as the upland Hmong do not feel ethnically Lao (Evans

1999b). There is consequently a feeling of resentment amongst many that the labelling

is being used to bolster the centrality of the Lowland Lao who have always been, and

still are, the local dominant majority, and who think of themselves as simply Lao, and

that it is the identity and culture of the Lowland Lao that is unfairly being used to

characterize the country of Laos. Furthermore, the use of geographical terms to

suggest three neat divisions in the population does not really disguise the existence of

great diversity within the Midland and Upland Lao categories, and there is far from

being a shared identity even within each ‘geographical’ group.

More recently, since 1995, there has been a new move away from the description of

the people of Laos as falling into three discrete groups, and instead a public declar-

ation and even emphasis of the fact that there are as many as forty-seven ethnic groups

within Laos. One eVect of this recognition of ethnic diversity by the government

noted by Evans (1999b) is, interestingly, that it serves to further highlight the

importance of the Lowland Lao, as this single group stands out as very large when

compared to the size of the other ethnic groups, and much more prominent size-wise

than in the previous three-way classiWcation. Whether or not this is deliberate

manipulation of ethno-linguistic categorization in order to promote the centrality of

one, dominant group is not clear. However, the continued identiWcation of the name

of the country with the most populous and dominant ethnic group certainly seems to

focus attention away from the existence of the Mon-Khmer and Sino-Tibetan groups,

and suggest that national identity should be seen in ethnic Lao terms.

Generally, though, despite persistent government eVorts since 1975 to develop a

nationwide sense of shared Lao identity, the results of this are rather weak and there

has only been limited success in the stimulation of a national identity. Continually

thwarting attempts at nation-building in Laos are a number of diYcult obstacles

which relate both to the physical and the human composition of the country as well as

its location and linguistic make-up.

Thailand and Laos

411

A Wrst hindrance to the development of national identity (which theoretically might

be overcome) is the fact that there is still no formally established and easily recogniz-

able national standard language. The obvious contender for a national language

would be a form of Lao, varieties of which are spoken natively by two thirds of the

population. However, thus far there have not been any signiWcant attempts to create

and embed a national standard language throughout the country, and energetic

promotion of a national standard language as seen in Thailand has been largely absent

from the development of Laos. Amongst the various forms of Lao spoken in the

country, there is a good level of mutual intelligibility, and the pronunciation of the

elite living in the nation’s capital Vientiane functions as an unoYcial lingua franca in

much of the country as well as occurring heavily in national television and radio

broadcasts. However, EnWeld (1999) notes that Vientiane Lao generally rates poorly as

a national language because although it is widely understood, it is not enforced as the

language of instruction within education, and is not the sole language of government

business, public announcement, or religion. Those domains of life which in other

countries are used to build and reinforce a national language are signiWcantly not

dominated by any single language in Laos, and the result is that though Vientiane Lao

may be commonly used and heard, it nevertheless fails to have the symbolic unifying

power of a real national language. The same is not necessarily true of written Lao,

which is produced in a uniform way throughout the country and is distinct in

appearance from Thai and other neighbouring scripts. However, literacy levels remain

fairly low in Laos, and the provision of education which might raise literacy (and also

promote a standard language) is sporadic in much of the countryside and also not

carried out via any uniform national curriculum. The potential unifying power of

written Lao is therefore currently not exploited to its full.

A second, important obstacle to the formation of a uniWed nation in Laos is the

simple geography of the country. A large amount of Laos is made up of mountains

and heavily forested hills which make internal communication extremely diYcult.

Due to a general lack of economic development (Laos is one of the poorest countries

in Asia), the infrastructure to support movement around the country remains very

poor. There is no railway system, an unreliable, restricted network of roads, and being

fully landlocked, very little water-borne transportation for such a large country. The

result of this is that there is little contact and communication between people in

diVerent parts of the country and not enough dynamic interaction for the spread of a

nationwide collective identity. Instead, Laos remains a strongly rural country in which

villages are largely self-reliant and there is limited regional trade and interaction. The

loyalty and identiWcation of most of the population is therefore with its particular

village and local ethnic group, and there is little regular concern with larger units such

as the state.

A third diYculty for the construction of a national identity in Laos stems from the

fact that the borders of modern Laos have been established in a highly artiWcial and

unnatural way in treaties and agreements which France entered into with Thailand

412

A. Simpson and N. Thammasathien

and other neighbouring powers. The result of these treaties is that many ethnic

groups have been split by the borders into two adjacent countries and that Laos

also includes a very large number of ethnically diVerent people, making for an

extremely heterogeneous population. Laos is therefore sometimes suggested to be a

‘Wction of a nation’, invented but not thought through properly by the French colonial

government. A serious consequence of the very mixed nature of the population of

Laos is that there is an important lack of available symbols that can be used to

promote a national identity. There is no longer any king of Laos, no uniform religion

(only 50 to 60 per cent Buddhist, with the remainder being animist – Savada 1995), no

standard national language, and wider cultural variation amongst ethnic groups than

in Thailand.

Related to the above is the ‘complication’ of neighbouring Isan in Thailand, and the

fact that 80 per cent of the Lao ethnic group is actually located in Thailand rather than

Laos due to the unnatural border created by the treaties between Thailand and

France. Although the label ‘Lao’ for inhabitants of the northeast of Thailand was

oYcially suppressed for a while and replaced by ‘Isan’, the Lao of Laos and those in

Isan are really one ethnic group with a single basic language form (with various

mutually intelligible dialects). The only really distinctive diVerences in language

between the two Lao groups are that those in Laos have their own, special form of

writing, and that the Lao spoken in post-1975 Laos has been simpliWed by the removal

of deferential language encoding diVerences in social hierarchy. Otherwise, the Lao of

Laos and the Lao of Isan are still very close in culture and language, and there are

regular cross-border trading contacts between the two groups. Perhaps somewhat

surprisingly though, there is actually no drive from either Lao group to integrate itself

with the other and form a united Lao state. The Isan Lao are much more oriented

towards Bangkok and Thailand than Laos, and the Lao in Laos do not show any

indication of wanting to be part of Thailand. Consequently, the split cross-border

existence of the Lao is actually not a primary area of concern for those who might

hope to further the construction of a Lao national identity within Laos. Having noted

this, the separation of the Lao into two countries nevertheless does make it harder for

the government in Vientiane to construct a national identity which will successfully

distinguish its citizens clearly from the citizens of other neighbouring states.

A Wnal factor which is now interfering with the construction of a national identity

in Laos is the inXuence of nearby Thailand and the penetration of Thai language into

Laos. As television is becoming more widely received around the country, it is Thai

language channels (received from across the border) that are frequently being watched

rather than domestic Lao programmes. This is due to the simple fact that the

production quality of the Thai channels is superior to that of the Lao programmes

and the content is also seen to be more varied and engaging. Because of the linguistic

closeness of Thai and Lao, and the frequent exposure to Thai television and radio,

signiWcant numbers of Lao people can therefore now understand Standard Thai. The

possibility for the Lao government to use television as a means to spread a national

Thailand and Laos

413

form of Lao language and identity and compensate for the lack of communication

through the countryside is consequently being lost to the more attractive nature of

Thai television programming. Thai publications are also being increasingly read by

those with education and made use of (for example, to gain access to new technology)

when Lao equivalents are not available. There is consequently a signiWcant and

increasing input of Thai language into Laos and new concern as to how this may

inXuence the status of Lao over time. Concerning the previous role of French in Laos,

this did not have much signiWcant lasting inXuence on the country, perhaps because it

was never widely taught outside the few small urban centres that are present in the