Language Testing, Migration

and Citizenship

Advances in Sociolinguistics

Series Editor: Professor Sally Johnson, University of Leeds

Since the emergence of sociolinguistics as a new field of enquiry in the late 1960s,

research into the relationship between language and society has advanced almost beyond

recognition. In particular, the past decade has witnessed the considerable influence of

theories drawn from outside of sociolinguistics itself. Thus rather than see language as a

mere reflection of society, recent work has been increasingly inspired by ideas drawn

from social, cultural, and political theory that have emphasized the constitutive role

played by language/discourse in all areas of social life. The Advances in Sociolinguistics

series seeks to provide a snapshot of the current diversity of the field of sociolinguistics

and the blurring of the boundaries between sociolinguistics and other domains of study

concerned with the role of language in society.

Discourses of Endangermen: Ideology and Interest in the Defence of Languages

Edited by Alexandre Duchêne and Monica Heller

Globalization and Language in Contact

Edited by James Collins, Stef Slembrouck and Mike Baynham

Globalization of Language and Culture in Asia

Edited by Viniti Vaish

Linguistic Minorities and Modernity: A Sociolinguistic Ethnography, 2nd edition

Monica Heller

Language, Culture and Identity: An Ethnolinguistic Perspective

Philip Riley

Language Ideologies and Media Discourse: Texts, Practices, Politics

Edited by Sally Johnson and Tommaso M. Milani

Language in the Media: Representations, Identities, Ideologies

Edited by Sally Johnson and Astrid Ensslin

Language and Power: An Introduction to Institutional Discourse

Andrea Mayr

Multilingualism: A Critical Perspective

Adrian Blackledge and Angela Creese

Semiotic Landscapes Language, Image, Space

Adam Jaworski and Crispin Thurlow

The Languages of Global Hip-Hop

Edited by Marina Terkourafi

The Language of Newspaper: Socio-Historical Perspectives

Martin Conboy

The Languages of Urban Africa

Edited by Fiona Mc Laughlin

Language Testing, Migration and Citizenship: Cross-National Perspectives on

Integration

Regimes

Edited by Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

Language Testing,

Migration and

Citizenship

Cross-National Perspectives on

Integration Regimes

Edited by

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and

Piet Van Avermaet

Continuum International Publishing Group

The Tower Building

80 Maiden Lane

11 York Road

Suite 704, New York

London SE1 7NX

NY 10038

www.continuumbooks.com

© Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet and contributors 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying,

recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission

in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-8470-6345-8 (Hardback)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

Typeset by Newgen Imaging Systems Pvt Ltd, Chennai, India

Printed and bound in Great Britain by MPG Biddles Ltd, King’s Lynn, Norfolk

Contents

Acknowledgements vii

Notes on contributors

viii

INTRODUCTION

1 Testing regimes for newcomers

1

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

PART I CASE STUDIES IN EUROPE

2 The politics of language and citizenship in the Baltic context

35

Gabrielle

Hogan-Brun

3 Language, migration and citizenship in Sweden:

still a test-free zone

57

Lilian

Nygren-Junkin

4 Inventing English as convenient fiction: language testing

66

regimes in the United Kingdom

Adrian

Blackledge

5 Language, migration and citizenship in Germany:

87

discourses on integration and belonging

Patrick Stevenson and Livia Schanze

6 One nation, two policies: language requirements for

107

citizenship and integration in Belgium

Piet Van Avermaet and Sara Gysen

7 Testing regimes for newcomers to the Netherlands

125

Guus Extra and Massimiliano Spotti

8 Regimenting language, mobility and citizenship in

148

Luxembourg

Kristine

Horner

9 Spanish language ideologies in managing immigration and

167

citizenship

Dick Vigers and Clare Mar-Molinero

PART II CASE STUDIES ABROAD

10 The language barrier between immigration and citizenship

189

in the United States

Tammy

Gales

vi

11 Canada: a multicultural mosaic

211

Lilian

Nygren-Junkin

12 The spectre of the Dictation Test: language testing for

224

immigration and citizenship in Australia

Tim

McNamara

13 Citizenship, language and nationality in Israel

242

Elana Shohamy and Tzahi Kanza

Index

261

Contents

vii

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to Karin Berkhout at Babylon,

Centre for Studies of the Multicultural Society (Tilburg University,

the Netherlands) for her support in preparing the manuscript for this

Volume.

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and

Piet Van Avermaet

Editors

viii

Piet Van Avermaet

Centre for Diversity and Learning, Director

Ghent University

Belgium

e-mail: Piet.VanAvermaet@UGent.be

Adrian Blackledge

Professor of Bilingualism

School of Education

University of Birmingham

United Kingdom

e-mail: a.j.blackledge@bham.ac.uk

Guus Extra

Professor of Language and Minorities

Department of Language and Culture Studies

Tilburg University

The Netherlands

e-mail: guus.extra@uvt.nl

Tammy Gales

Washington Program Graduate Fellow

Linguistics Department

University of California, Davis

USA

e-mail: tgales@ucdavis.edu

Sara Gysen

Researcher

Linguistics Department

University of Leuven

Belgium

e-mail: sara.gysen@arts.kuleuven.be

Gabrielle Hogan-Brun

Senior Research Fellow

Graduate School of Education

Notes on contributors

ix

Notes on contributors

University of Bristol

United Kingdom

e-mail: g.hogan-brun@bristol.ac.uk

Kristine Horner

Lecturer in German and Sociolinguistics

Director of Postgraduate Studies in German/Russian

School of Modern Languages and Cultures

University of Leeds

United Kingdom

e-mail: K.Horner@leeds.ac.uk

Tzahi Kanza

Program in Applied Linguistics

School of Education

Tel Aviv University

Israel

e-mail: tzahi@hla.co.il

Clare Mar-Molinero

Modern Languages/Centre for Transnational Studies

School of Humanities

University of Southampton

United Kingdom

e-mail: F.C.Mar-Molinero@soton.ac.uk

Tim McNamara

Professor of Applied Linguistics

School of Languages and Linguistics

University of Melbourne

Australia

e-mail: tfmcna@unimelb.edu.au

Lilian Nygren-Junkin

Researcher and Senior Lecturer

Department of Swedish

University of Göteborg

Sweden

e-mail: lilian.nygren.junkin@svenska.gu.se

Livia Schanze

Doctoral student in Modern Languages

x

Notes on contributors

School of Humanities

University of Southampton

United Kingdom

e-mail: l.schanze@gmx.de

Elana Shohamy

Chair, Language Education Program

School of Education

Tel Aviv University

Israel

e-mail: elana@post.tau.ac.il

Massimiliano Spotti

Researcher

Babylon, Centre for Studies of the Multicultural Society

Tilburg University

The Netherlands

e-mail: m.spotti@uvt.nl

Patrick Stevenson

Professor of German and Linguistic Studies

Modern Languages

School of Humanities

University of Southampton

United Kingdom

e-mail: P.R.Stevenson@soton.ac.uk

Dick Vigers

Research Fellow

Centre for Transnational Studies

School of Humanities

University of Southampton

United Kingdom

e-mail: R.C.Vigers@soton.ac.uk

INTRODUCTION

This page intentionally left blank

3

1.1 Historical context

The face of migration in Europe has changed quite dramatically after

1991. Prior to the fall of the Berlin wall, which announced the end of

the Cold War, migrant groups were easily identifiable groups (in Europe,

mostly people from the Mediterranean basin). Such groups often became

sedentary in their host country, forming recognizably immigrant minor-

ity groups, which after having consolidated their presence became

‘ethnic’ communities in their own right. Traces of this group migration

are clear everywhere across Europe, and it would be unthinkable to

picture large European urban areas without them. This relatively trans-

parent migration pattern enabled the emergence of a research tradition

that focused on the histories of these groups, their language rights, their

(often underachieving) educational success, the language diversity that

typified their presence, their position on the labour market and, last but

not least, their civil and political participation. When the label ‘migra-

tion research’ is used in Europe, it generally refers to this kind of

research.

The aftermath of 1991 saw a new pattern of migration emerging.

Nowadays, this involves a far more diverse population from Eastern

Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America. The pattern of migration differs

from the previous one for two reasons. First, migration is not supported

anymore by fairly liberal labour policies, like those that characterized

Northern Europe during the 1960s and the early 1970s, and Southern

Europe during the late 1990s. Second, migrants themselves are well

aware that Southern Europe is only the beginning of yet another migra-

tion trajectory that often takes them to Northern Europe. In the same

way, the motives for and the forms of migration have changed. People,

when permitted to enter European countries, arrive not only as tradi-

tional labour migrants but also as refugees, short-time migrants, transi-

tory migrants, highly educated work forces and so forth. This topping

up of the original diversity brought about by the migratory flux before

1991 causes difficulties in popular conceptions of the ‘other’. It becomes

more and more difficult to grasp what a migrant is, and to characterize

Testing regimes for newcomers

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and

Piet Van Avermaet

1

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

4

his legal and administrative presence. Furthermore, the post-1991 migrant

seeks housing and shelter in existing, authentic ‘migrant’ neighbour-

hoods, and so the latter become densely layered and very complex

communities that go beyond the circumscribed ethnic communities

that majorities were used to before 1991 (see Wright 2000 for a compre-

hensive overview).

The effect of this blending of ‘old’ and ‘new’ migration produces a

new form of diversity in Europe, one for which the term ‘super-diversity’

has been coined (Vertovec 2006: 1–2). This type of diversity is of a more

complex kind in which neither the origin of people, nor their presumed

motives for migration, nor their ‘careers’ as migrants (sedentary versus

short-term and transitory), nor their socio-cultural and linguistic fea-

tures can be presupposed. The cosy (dis)comfort of the old migration,

where migrants, their trajectories and their lives were understood, or at

least acknowledged by majority group members, has disappeared and

is replaced by a form of complexity that is presenting itself unequivo-

cally at Europe’s doors. This raises critical questions about the rationale

and the future of nation-states in Europe, about their dense and fast-

moving urban spaces and about the embedded and still omnipresent

supremacy of the (white) majority’s perspective within those institutions

that regulate the streaming of migrants (Stead-Sellers 2003; Blommaert

2008). It also raises practical issues of the first order. The presence

of these very diverse groups of people has effects on the capacity of

bureaucracies to handle cases successfully and brings politicians to

cogitate upon new methods to determine who can access the territory

and who cannot (a process in which language issues play a critical

role). Research has not yet addressed this new form of complexity, other

than in a fragmentary manner. There is also a strong need for addressing

these issues from both cross-national and crosslinguistic perspectives,

in order to get a deeper understanding of conceptual presuppositions

surrounding the public and political debate on these issues (Heller

2003; Shohamy 2007).

Against this background, a Working Group on Testing Regimes was

established in 2006 at the University of Southampton, aiming at cross-

national cooperation between four partner universities: Southampton

(Clare Mar-Molinero, Patrick Stevenson, Euan Reid), Bristol (Gabrielle

Hogan-Brun), Tilburg (Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti) and Ghent

(Piet van Avermaet). The project title Testing Regimes contains a delib-

erately chosen ambiguity and refers both to the regimes of testing and

to the testing of regimes. On its website (www.testingregimes.soton.

ac.uk/partners), the rationale of the project was motivated by the ‘EU

enlargement and the ongoing rise in the rate of migration into and

across Europe: both phenomena suggest that the salience of these issues

Testing regimes for newcomers

5

is likely to continue to grow.’ The project has led to two major book

publications, with a mix of same and different contributors (Hogan-

Brun, Mar-Molinero and Stevenson 2008; this Volume). The topic itself,

the public discourse and the political and legal regimes surrounding it

are in flux, generally moving in the direction of more restrictive regimes

over time across nation-states.

The present Volume comes to wrestle with new patterns of testing

regimes. Rather than exploring these from the perspective of the migrant

(Pavlenko and Blackledge 2004; Block 2006; Shohamy 2008), the Volume

takes the perspective of the nation-states’ machinery. It goes into both

the rites of passage that either allow or prevent newcomers from access-

ing a country and for the measures that are imposed on the immigrant

population at large in terms of societal and linguistic integration. More

specifically, the Volume takes stock, discusses and evaluates the very

regimes of testing that, primarily across Europe, are currently working

towards societal and linguistic integration. This introductory chapter

gives an outline of the link between the concepts of nation-states, lan-

guage and identity (Section 1.2) and goes into the European public and

political discourse on foreigners and integration (Section 1.3). Next, an

outline is given of the Common European Framework of Reference and

its (mis)use and (mis)interpretation in testing language skills of immi-

grants (Section 1.4). Finally, the structure and contents of this book are

presented (Section 1.5).

Much longer histories and documented experiences of testing

regimes are available outside Europe in contexts in which European

immigrants at least initially played a major role in establishing such

regimes. This is the rationale for our focus in the Volume on eight care-

fully selected European case studies without neglecting comparative

views on a selection of four non-European states that are referred to as

immigrant countries par excellence from an early European perspec-

tive of emigration (see Section 1.5).

1.2 Nation-states, language and identity

It may seem odd, but contrary to a widespread belief the concepts of

‘nation’ and ‘nation-state’ are relatively recent phenomena. In the con-

text of the reference that we make to nation-states in this Volume, we

also have to draw another distinction, that between nationality and

citizenship. Although these two concepts may often be used as syn-

onyms nowadays, we should be aware of their historical and contextual

difference in denotation (Guiguet 1998). Nationals belong to a nation-

state but they may not have all the rights linked to citizenship (e.g.,

voting rights). In this sense, citizenship is a more inclusive concept than

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

6

nationality, and as such it is key to the testing regimes that are dealt

with in this Volume. Barbour (2000) discusses the distinction between

the two concepts in terms of a legally defined entity, citizens, and an

(ethnic) population, respectively. Nations have frequently developed

from ethnic groups, but the two do not coincide. Ethnic groups are

either subsets of nations or they function as collective entities across

nation-state borders. It is through their construction and consolidation

that nation-states have also promoted yet another two (erroneous) pop-

ular beliefs: that of the existence of a national language common to all

fellow nationals and that of the primacy of the standard variety of this

same national language over other territorial language varieties (see

Blackledge, this Volume). The first belief, as it were, has made a lan-

guage correspond to a nation-state, as a consequence of which this lan-

guage was elected as a core value of an imagined community of fellow

nationals which then calls itself a nation (Anderson 1991; Brubaker

1996). On top of this, the second belief has resulted in a situation where

fellow nationals who master the standard variety of the national lan-

guage hold more powerful positions than those who do not (McColl

Millar 2005). The consequences of these two beliefs have been huge for

Europe, for its modern history, for its inhabi tants and for those indi-

viduals who want to enter its territory and legally reside in one of its

nation-states. The equation of a standard national language with a

national identity is the tangible product of a long-established ideologi-

cal industry of exclusion (Piller 2001). It is on this very ideological

industry that the testing regimes that we analyse in this Volume are

firmly grounded. Language standardization is one of the key features

that have provided the cultural back-up for aspiring polities to be rec-

ognized as nation-states ipso facto (see Fishman 1973: 39–85, 1989:

105–175, 270–287; Edwards 1985: 23–27; Joseph 2004: 92–131; Gal

2006: 13–27; for historical overviews). It is also the key feature that

authorizes those who live within a nation to ask those who want to

access their country and aspire to become citizens to learn the national

language.

A tangible example of the above is the equation of German and

Germany, as a reaction to the rationalism of the Enlightenment and

based also on anti-French sentiments. The concept of nationalism

emerged at the end of the eighteenth century; the concept of nationality

only a century later. Romantic philosophers like Johan Gottfried Herder

and Wilhelm von Humboldt laid the foundation for the emergence of a

linguistic nationalism in Germany on the basis of which the German

language and nation were conceived of as superior to the French. The

French, however, were no less reluctant to express their conviction that

the reverse was true. Although every nation-state is characterized by

Testing regimes for newcomers

7

heterogeneity, including linguistic heterogeneity, nationalistic move-

ments have always invoked this classical European discourse in their

equation of language and nation (cf. revitalized references in Germany

to such concepts as Sprachnation and Leitkultur; see also Stevenson,

this Volume). For recent studies on language, identity and nationalism

in Europe, we refer to Barbour and Carmichael (2000) and Gubbins and

Holt (2002), and for a comparative study of attitudes towards language

and national identity in France and Sweden to Oakes (2001).

The USA has not remained immune to this type of nationalism either.

The English-only movement, US English, was founded in 1983 out of a

fear of the growing number of Hispanics on American soil (Fishman

1988; May 2001: 202–224). This organization resisted bilingual Spanish-

English education from the beginning because such an approach they

felt would lead to ‘identity confusion’. Similarly, attempts have been

made to give the assignment of English as the official language of the

USA a constitutional basis. This was done on the presupposition that

the recognition of other languages (in particular Spanish) would under-

mine the foundations of the nation-state. This nationalism has its roots

in a white, protestant, English-speaking elite (Edwards 1994: 177–178).

Europe’s identity is to a great extent determined by cultural and lin-

guistic diversity. Although the same holds at the level of European

nation-states, nationalistic movements still call upon the equation of

language and nation in claiming their right of primacy on national

grounds. Table 1.1 serves to illustrate the heterogeneity – often disguised

as homogeneity because of the close connection between nation-state

references and official state language references – present among the 30

EU (candidate) nation-states with their estimated populations (ranked

in decreasing order of millions) and official state languages (Haarmann

1995).

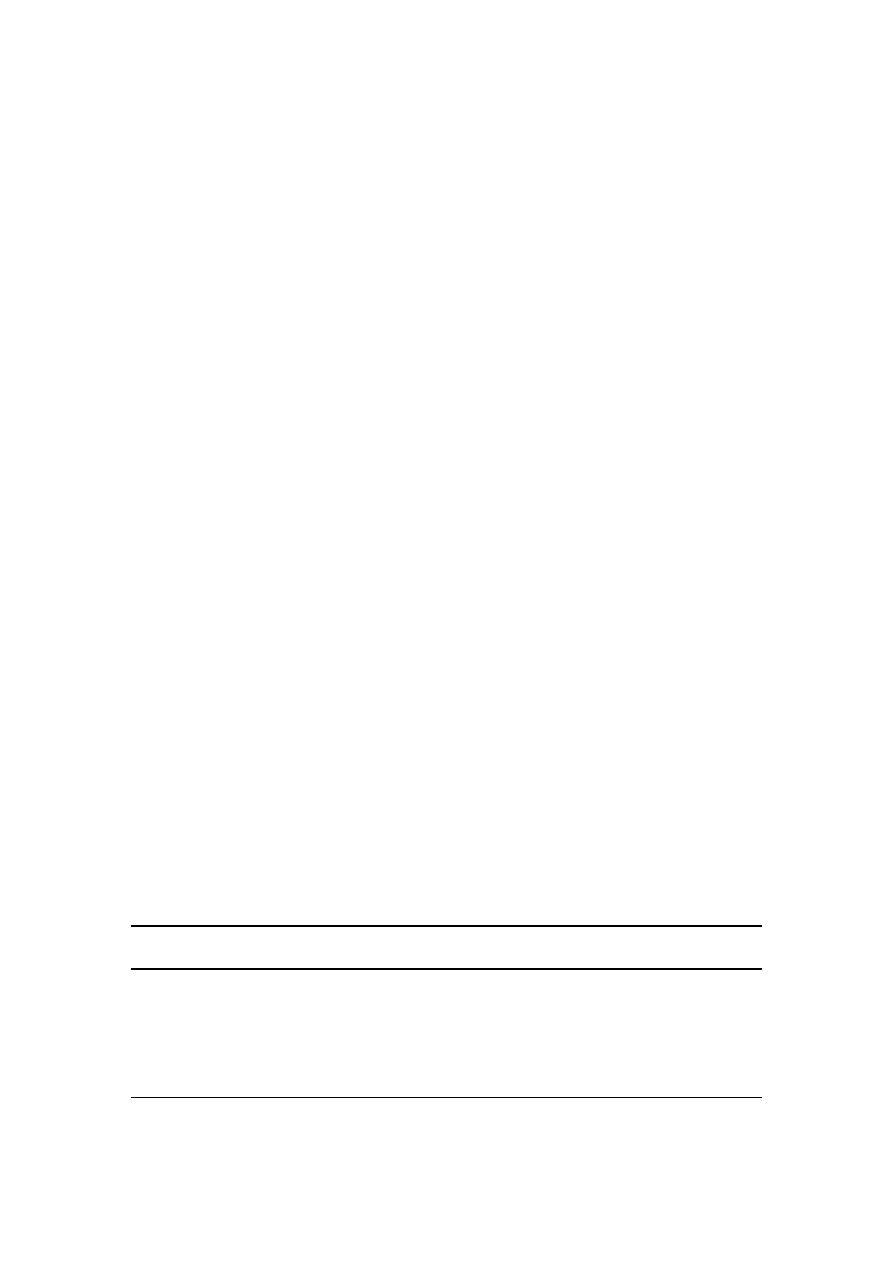

As Table 1.1 makes clear, there are large differences in population

size among EU nation-states. German, French, English, Italian, Spanish

and Polish belong to the six most widely spoken official state languages

in the present EU, while Turkish would come second to German in a

further enlarged EU. Table 1.1 also shows that – with the exceptions of

Belgium, Austria and Cyprus – in 27 out of 30 cases, distinct official

state languages are the clearest feature used by state enterprises to dis-

tinguish themselves from their neighbours and so to claim their national

authority (Barbour 2000). This match between nation-state references

and official state language references obscures the very existence of

other languages that are actually spoken across European nation-states.

Many of these languages are indigenous minority languages with a

regional base, but there are many others that stem from abroad and are

characterized by another territorial link. Extra and Gorter (2001, 2008)

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

8

refer to these ‘other’ languages as regional minority (RM) and immi-

grant minority (IM) languages, respectively. Their downgraded status is

in line with the equation of language and nation-state. However, the

traditional nation-state model that acknowledges only official state lan-

guages cannot offer an adequate basis for societal belonging in this age

of globalization and migration (Castles 2005: 314).

Table 1.1

Overview of 30 EU (candidate) nation-states with estimated popu-

lations and official state languages (EU figures for 2007)

Nr

Nation-states

Population

(in millions)

Offi cial state language(s)

1

Germany

82.5

German

2

France

60.9

French

3

United Kingdom

60.4

English

4

Italy

58.8

Italian

5

Spain

43.8

Spanish

6

Poland

38.1

Polish

7

Romania

21.6

Romanian

8

The Netherlands

16.3

Dutch (Nederlands)

9

Greece

11.1

Greek

10

Portugal

10.6

Portuguese

11

Belgium

10.5

Dutch, French, German

12

Czech Republic

10.3

Czech

13

Hungary

10.1

Hungarian

14

Sweden

9.0

Swedish

15

Austria

8.3

German

16

Bulgaria

7.7

Bulgarian

17

Denmark

5.4

Danish

18

Slovakia

5.4

Slovak

19

Finland

5.3

Finnish

20

Ireland

4.2

Irish, English

21

Lithuania

3.4

Lithuanian

22

Latvia

2.3

Latvian

23

Slovenia

2.0

Slovenian

24

Estonia

1.3

Estonian

25

Cyprus

0.8

Greek, Turkish

26

Luxembourg

0.5

Luxemburgisch, French, German

27

Malta

0.4

Maltese, English

Candidate

nation-states

Population

(in millions)

Offi cial state language

28

Turkey

72.5

Turkish

29

Croatia

4.4

Croatian

30

Macedonia

2.0

Macedonian

Testing regimes for newcomers

9

Europe displays significant differences when looked at from a supra-

national institutional angle and when looked at in terms of a geogra-

phical unit (Gal 2006: 24). Both angles, though, converge when Europe

echoes a set of meanings that contrast with who and what is there out-

side of its territory. These who’s and what’s are world regions with their

own temporal connotations, but they are also people who try to access

Europe and who are characterized by social, cultural and linguistic

diversity. With the post-1991 migration flux, Europe’s scope and refer-

ence have changed considerably. The relationship between language,

nation-states and national identities has become less static, and changes

have occurred in three different arenas (Oakes 2001):

In the national arenas of the EU member-states: the traditional iden-

tity of these nation-states has been challenged by major demographic

changes (in particular in urban areas) as a consequence of processes

of international migration and intergenerational minorization.

In the supranational arena: the concept of a European identity has

emerged as a consequence of increasing cooperation and integration

at the European level.

In the global arena: our world has become smaller and more interac-

tive as a consequence of the increasing availability of new forms of

information and communication technology.

Major changes in each of these three arenas have led inhabitants of

Europe to no longer identify exclusively with singular nation-states.

Instead, they show multiple affiliations that range from transnational

ones to both global and local ones. The notion of a European identity

is a tangible product of these changes. Formally expressed for the first

time in the Declaration on European Identity of December 1973 in

Copenhagen, numerous European institutions and policy documents

have propagated and promoted this idea ever since, culminating in the

(rejected) proposal for a European Constitution in 2004. In discussing

the concept of a European identity, Oakes (2001: 127–131) emphasizes

that the recognition of the concept of multiple transnational identities

is a prerequisite rather than an obstacle. Such recognition not only

occurs among the traditional inhabitants of European nation-states but

also among members of IM communities across Europe (Phalet and

Swyngedouw 2002). Apart from identifying with ethno-religious fea-

tures that link them to their country of origin, IM communities also

hold ties with their host country. Key to a European identity is the abil-

ity to deal with increasing cultural and linguistic heterogeneity, thus

presenting multilingualism as an asset rather than a burden for twenty-

first century ‘Europeans’ (Van Londen and De Ruijter 1999; Brumfit

2006). Taken from the perspective that migrants are characterized by

z

z

z

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

10

a transnational mindset, a transnational identification and multilingual

competencies, IM community members across Europe could be consid-

ered as role models instead of ‘deficit groups’ for the development of

a European identity. The prevalent public, political and educational

discourses in Europe’s nation-states, however, still picture them as

outsiders. They neither receive the trophy of transnationality’s role

models within the official EU discourse, nor are they included in the

nation, lan guage and identity equation. Rather, both national and supra-

national discourses address the linguistic and cultural heterogeneity

of newly arrived migrants, of IM community members and of their

descendants as undermining the national (common) order. As such,

although immigrants might have embraced several different forms of

truncated multilingualism (Blommaert et al. 2000), they remain differ-

ent from indigenous majority and minority nationals and still have a

long way to go to citizenship.

1.3 The European discourse on foreigners and

integration

When going through the jargon used in the European public and poli-

tical discourse to refer to IM groups and to their languages, two major

characteristics emerge (Extra and Barni 2008). First, IM groups are often

referred to as non-national residents (allochtonen, étrangers, Ausländer,

foreigners, depending on the country taken into consideration). The

same connotation of not belonging to the nation also applies to their

languages addressed as non-territorial, non-regional, non-indigenous

or non-European. In the current European discourse, this conceptual

exclusion instead of inclusion derives from a restrictive interpretation

of the notions of citizenship and nationality. From a historical point of

view, such notions are commonly shaped by a constitutional jus san-

guinis (law of the blood), in terms of which nationality derives from

parental origins, in contrast to jus soli (law of the soil), in terms of

which nationality derives from the country of birth. When European

emigrants left their continent in the past and colonized countries

abroad, they legitimized their claim to citizenship by spelling out jus

soli in the constitutions of these countries of settlement. Good exam-

ples of this strategy can be found in English-dominant immigration

(sub)continents like the USA, Canada, Australia and South Africa (see

Johnson et al. 1999 for an analysis of the concepts of naturalization and

citizenship in the USA; see also Gales, this Volume). In establishing the

constitutions of these (sub)continents, no consultation took place with

indigenous peoples, such as native Americans, Inuit, Aboriginals and

Zulus, respectively. At home, however, Europeans predominantly upheld

Testing regimes for newcomers

11

jus sanguinis in their constitutions and/or perceptions of nationality

and citizenship, in spite of the growing numbers of newcomers who

strive for an equal status as citizens (Extra and Yag˘mur 2004: 11–24).

The second major characteristic is the overarching focus on integra-

tion and the call on newcomers, and more generally on IM populations,

to integrate. Although extremely popular nowadays, the call for inte-

gration stands in sharp contrast to the jargon of exclusion reported

above. The notion of integration remains vague and therefore politically

popular as well. Integration may refer to a wide spectrum of underlying

concepts that vary across nation-states’ discourses of belonging, being

variation over space, and within their discourses of belonging, being

variation over time. Miles and Thränhardt (1995), Bauböck et al. (1996),

Kruyt and Niessen (1997), Joppke and Morawska (2003), Böcker et al.

(2004) and Michalowski (2004) are good examples of comparative case

studies on the notion of integration in a variety of EU countries that

have been faced with increasing immigration since the early 1970s. The

extremes of the conceptual spectrum range from assimilation to multi-

culturalism. The concept of assimilation is based on the premise that

cultural differences between IM groups and established majority groups

should and will disappear over time in a society which is proclaimed

to be culturally homogeneous from the majority point of view. At the

other end of the spectrum, the concept of multiculturalism is based on

the premise that such differences are an asset to a pluralistic society,

which actually promotes cultural diversity in terms of new resources

and opportunities. While the concept of assimilation focuses on unilat-

eral tasks for newcomers, the concept of multiculturalism focuses on

multilateral tasks for all inhabitants in changing societies. In actual

practice, established majority groups often make strong demands on IM

groups to assimilate and are commonly very reluctant to promote or

even accept the notion of cultural diversity as a determining character-

istic of increasingly multicultural societies.

Residence in a country does not necessarily imply citizenship, as many

newcomers to a nation-state find out soon enough. Across European

nation-states, there are variable demands on newcomers for obtaining

citizenship with all its rights and obligations. In their European Inclu-

sion Index, Leonard and Griffith (2005) offer the following checklist of

indicators for citizenship and inclusion:

What is the legal basis for citizenship of the member state?

Is dual nationality allowed?

How efficient/lengthy is the processing of citizenship applications?

How much does it cost the applicant?

What are the refusal rates?

z

z

z

z

z

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

12

Does the applicant have a right to know the reasons for refusal?

How many years of legal residence does it take to become naturalized?

What civic/language requirements do member states impose for

citizenship?

Do governments provide language sessions? If so, how many hours

are provided free of charge?

Are citizenship lessons/tests a requirement?

Is language tuition provided?

What is the temperature of public opinion towards third-country

nationals, immigrants and minorities?

Is the government putting in place programmes aimed at shifting

public opinion?

In cooperation between the British Council and the Migration Policy

Group, both posted in Brussels, Citron and Gowan (2005) made a first

large-scale attempt to collect, analyse and present comparative cross-

national data in each of the 15 ‘old’ EU member-states on the following

five policy areas of civic citizenship and inclusion: labour market

inclusion, long-term residence, family reunion, nationality and anti-

discrimination. On the basis of the outcomes for each of these areas,

an Index was developed for the status quo of policies in each of the

member-states, measured against a European standard. As a follow-up

to this pilot European Civic Citizenship and Inclusion Index, Niessen et

al. (2007) together with the same partners developed what they have

recently come to refer to as a Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX)

for each of the more recent 26 EU member-states plus Switzerland

and Canada. In addition to the five areas referred to above, policies on

political participation were included in the comparative analyses. The

resulting country profiles are based on the outcomes of 140 indicators

for the six areas of study. In a cumulative proportional overall Index,

Sweden (88), Portugal (79), Belgium (69) and The Netherlands (68) take

up top-positions in the EU ranking, whereas Greece (40), Austria (39),

Cyprus (39) and Latvia (30) end up in bottom-positions. The 26 EU

countries score worst on policies for access to nationality and policies

for political participation. The MIPEX database is publicly available for

secondary analyses on the MIPEX website (www.integrationindex.eu).

Although the MIPEX data offer fascinating visualized cross-national

perspectives on the status quo of policies for all of the six areas

referred to above, they raise quite a number of methodological questions.

There is the problem of the definition and comparability of the concept

of ‘migrants’ across nation-states, the absence of a perspective on differ-

ent ethnocultural groups and the questionable reliability and validity

of scores obtained for each domain of analysis. In addition, the data

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

z

Testing regimes for newcomers

13

presented are based on evaluated policies on paper (i.e., document

analyses), which do not necessarily coincide with policies in practice.

Most importantly, however, the concept of ‘integration’ remains prob-

lematic, as was outlined before. It is interesting to compare the underly-

ing assumptions of ‘integration’ in the European public and political

discourse on IM groups at the national level with the assumptions made

at the level of cross-national cooperation and legislation. Across the EU,

politicians are eager to stress the importance of a proper balance between

the loss and maintenance of ‘national’ norms and values. A prime con-

cern in the public debate on such norms and values is cultural and

linguistic diversity, mainly in terms of the national languages of the EU.

National languages are often referred to as core values of cultural iden-

tity. Paradoxically, in the same public discourse, IM languages and cul-

tures are commonly conceived of as sources of problems and deficits

and as obstacles to integration, while national languages and cultures

in an expanding EU are regarded as sources of enrichment and as pre-

requisites for integration.

The public discourse on the integration of IM groups in terms of

assimilation versus multiculturalism can also be noticed in the domain

of education. Due to the growing numbers of IM pupils, schools are

faced with the challenge of adapting their curricula to this trend. Cur-

ricular modifications may be inspired by a strong and unilateral empha-

sis on learning (in) the dominant language of the majority in society,

given the significance of this language for success at school and on the

labour market, or by the awareness that the response to emerging mul-

ticultural school populations cannot be reduced to monolingual educa-

tion programming (Gogolin 1994). In the former case, the focus is on

learning (in) the national standard language as a second language, in

the latter case on offering more languages in the school curriculum. For

comparative European studies on this theme we refer to Barni and Extra

(2008), Extra and Gorter (2008) and Extra and Yag˘mur (2004).

At the EU level, the European Council meeting of Ministers of the

Interior/Integration, held in June 2003 in Thessaloniki, stressed the

importance of developing cooperation and exchange of information with

the newly established National Contact Points on Integration. At a follow-

up European Council meeting in November 2004 in The Hague, a series

of common basic principles were approved including the following:

integration is a dynamic two-sided process;

integration presupposes respect for the basic values of the EU;

basic knowledge of the language, history, and institutions of the

country of settlement is indispensable for integration;

employment plays a key role in the integration process.

z

z

z

z

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

14

Moreover, a Handbook on Integration for policy-makers and practi-

tioners (www.europa.eu.int/comm/justice_home) was presented, pre-

pared by Jan Niessen and Yongmi Schnibel of the Migration Policy Group,

on behalf of the European Commission (DG for Justice, Freedom and

Security), as an official publication of the European Communities,

Luxembourg 2004. According to the publishers, this Handbook offers

best experiences learned from 26 EU member-states on the following

themes: introduction courses for newly arrived immigrants and recog-

nized refugees, civic participation and indicators. It was developed in

close cooperation with the above-mentioned National Contact Points

on Integration and aims to promote the creation of a coherent European

framework on integration by facilitating the exchange of experience

and information. The Handbook is addressed to policy makers and

practitioners at the local, regional, national and EU levels.

In many cases across Europe, it is language that fulfils the role of

lubricant of the integration machinery and that works as a gatekeeper

of the national order. Although differences in national approaches can

be observed, it cannot be denied that a proliferation of integration tests

and courses is spreading across Europe through policy emulation

(Leung and Lewkowicz, 2006; Foblets et al. 2008). At the beginning of

2007, a small-scale study was conducted in cooperation with the Asso-

ciation of Language Testers in Europe (ALTE, www.alte.org) to compare

integration and citizenship policies across Europe. Data were collected

by ALTE members in 18 countries. Although an earlier ALTE survey in

2002 showed that 4 out of 14 countries (29 per cent) had language con-

ditions for citizenship, the 2007 survey showed that five years later this

number had grown to 11 out of 18 countries (61 per cent). Some coun-

tries, like Italy, which in 2007 did not have language requirements for

integration and citizenship, are in the process of revising their integra-

tion policy in the direction of such requirements. For a detailed com-

parison of European countries’ integration policies in this domain, we

refer to Van Avermaet (2008) and Van Oers (2006). In a small-scale com-

parative study of immigration policies in ten European countries, Dispas

(2003) revealed that in most of these countries the word ‘assimilation’

tends to be replaced by the supposedly politically correct concept of

‘integration’. A subsequent, more in-depth analysis of these integration

policies, however, reveals that, over a period of ten years, a shift can be

observed from policies that acknowledge cultural pluralism to policies

that emphasize the actual assimilation into the ‘host country’. This

means that in these cases the word ‘integration’ is not used in its mutu-

ally inclusive sense.

While the process of setting up stricter immigration conditions with

a strong emphasis on language is fairly common across Europe, the

Testing regimes for newcomers

15

developed policies and discourses at nation-state level do differ and

hidden agendas evidently feature in immigration policies across Europe.

In some cases, these policies are used as a mechanism for exclusion

(Extra and Spotti, this Volume). In others, they function as a mechanism

for controlled immigration. The discourse and the policies themselves

are often an expression of the dominant majority group. A policy may

be chosen as a firm defence against ‘Islam terrorism’ and be embedded

in a discourse that takes advantage of the ‘fear’ brought on by the possi-

bility of a terrorist attack. To some extent, these immigrant policies

have to be seen as a token of the revival of the nation-state, with its tra-

ditional paradigm of one language, one identity, and one uniform set of

shared societal norms and cultural values. This is supposed to instil

people with a feeling of national security, confidence and order. This

revival of the nation-state stands in stark contrast to the processes of

globalization and the enlargement of the EU on the one hand and the

increasing importance attached to regions, localities, cities and neigh-

bourhoods on the other, referred to as processes of glocalization (De Bot

et al. 2001).

1.4 The common European framework

of reference

Integration – whether societal or linguistic – is not only a word in the

mouths of the many who employ it when confronted with ‘others’ or

with how ‘others’ make the headlines, mostly in terms of what they

lack rather than what they own and may contribute. More particularly,

the concept of integration finds support in a battery of instruments pro-

moted at the European level. Europe’s main institutions, the Council

of Europe and the European Union, are major actors in promoting a

multilingual Europe and in promoting plurilingualism of all its citizens

(Extra and Gorter 2008). Many European countries have adopted the

Council of Europe’s Common European Framework of Reference for

Languages (henceforth CEFR, 2001) as a basic instrument for the devel-

opment of language policies for admission, residence and/or citizen-

ship of immigrants. The CEFR defines levels of language proficiency

that allow learners’ progress to be measured at each stage of learning

and on a life-long basis.

The major aim of the CEFR is to offer a frame of reference, a meta-

language. It wants to promote and facilitate co-operation among educa-

tional institutions in different countries. It aims to provide a transnational

basis for the mutual recognition of language qualifications. A further

aim is to assist learners, teachers, course designers, examining bodies

and educational administrators to co-ordinate their efforts. And a final

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

16

aim is to create transparency in helping partners in language teaching

and learning to describe the levels of proficiency required by existing

standards and examinations in order to facilitate comparisons between

different systems of qualifications. It is important to emphasize that

the CEFR is not a prescriptive model or a fixed set or book of language

aims.

The CEFR consists of two underlying dimensions. On the one hand,

it has a quantitative dimension with concepts like domains (school,

home, work), functions (ask, command, inquire), notions (south, table,

father), situations (meeting, telephone), locations (school, market), top-

ics (study, holidays, work), and roles (listener in audience, participant

in a discussion). The qualitative dimension, on the other hand, expresses

the degree of effectiveness (precision) and efficiency (leading to com-

munication) of language learning. Scales are provided for many of the

parameters of language proficiency. This makes it possible to specify

differentiated profiles for particular learners or groups of learners.

The descriptive scheme has been defined as follows:

Language use comprises the actions performed by persons who as

individuals and as social agents develop a range of competences,

both general and in particular communicative language competences.

They draw on the competences at their disposal in various contexts

under various conditions and under various constraints to engage

in language activities involving language processes to produce and/

or receive texts in relation to themes in specific domains, activating

those strategies which seem most appropriate for carrying out the

tasks to be accomplished. (Council of Europe 2001: 9)

The key elements that can be distinguished in the descriptive

scheme are communicative language competence, language activities and

domains. The chapter on communicative language competence con-

sists of a description of linguistic competences, sociolinguistic compe-

tences and pragmatic competences. In addition, an in-depth description

of language activities is provided. Instead of the traditional four skills

of reading, writing, speaking and listening, the CEFR is based on a more

dynamic, interaction-oriented approach of describing communicative

skills. It distinguishes between reception, including listening compre-

hension and reading comprehension; interaction, including spoken

interaction and written interaction; production, which includes spoken

production and written production and finally mediation. The third

key element within the descriptive scheme chapter consists of domains.

Language activities are contextualized within domains. These may be

very diverse themselves, but for most practical purposes in relation to

language learning the CEFR classifies them into four domains, being

the public, personal, educational and occupational domain.

Testing regimes for newcomers

17

Next to the descriptive scheme, the CEFR formulates a number of

common reference levels. A set of six defined criterion levels (A1, A2,

B1, B2, C1, C2) are distinguished for use as common standards (see

Appendix). These common standards are intended to help the provid-

ers of courses and examinations to relate their products such as course

books, teaching courses and assessment instruments to a common ref-

erence system, and hence, indirectly, to each other.

As mentioned before, the cornerstone of integration policies in most

European countries is language. Language here has to be read as the

national or standard language of the dominant group in a particular

country. Knowledge of this national language at particular levels is the

main condition for those who want to apply for admission, residence

and citizenship. To realize this monolingual policy, many European

countries use the CEFR as a tool. This raises a number of questions.

The CEFR has been developed for the learning, teaching and assessing

of foreign language skills and not for a context of second language

learning. However, most immigrants learn the language of their host

country from scratch. The CEFR descriptors at the lower levels clearly

imply an already existing basic knowledge and literacy. This is prob-

lematic when they are used for integration and citizenship programmes

and for tests where a large part of the target group are either function-

ally illiterate or have low literacy skills. The CEFR descriptors at higher

levels presuppose higher levels of education. Lower- and semi-skilled

people who have no higher education background or do not study at a

higher level are not part of the target group. Moreover, the CEFR descrip-

tors mainly refer to adults and adolescents; they are less appropriate

for children or young learners. And yet, in some European countries

the CEFR is used in primary and secondary education for both young

and old ‘newcomers’, being for newly arrived immigrants and their

children.

The misuse or misinterpretation of the CEFR becomes even more

problematic once we take into account the consequences attached to

language courses and tests for immigrants. On the basis of being unsuc-

cessful at a language test that was never intended for these purposes,

people are refused citizenship, residence or even admission. Policy

makers determine a level of language proficiency required for admission,

residence or citizenship of immigrants by using the CEFR six-level sys-

tem with the global scale as outlined in the Appendix to this chapter.

This approach looks user-friendly, straightforward and simple. However,

often without any rationale or validation, a particular CEFR level of

language proficiency is chosen when developing a language policy for

integration of immigrants. This is clearly illustrated by the variation

in CEFR levels chosen for admission, residence or citizenship across

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

18

Europe (Van Avermaet 2008). In Denmark, the level of language profi-

ciency set for citizenship is B2; in The Netherlands it is A2. Moreover,

the level descriptors in the CEFR are often used as the basis for test

development. However, many of the descriptors lack both precision

and specificity, as a result of which test development for a specific lan-

guage at a specific level and for a specific purpose is not so straightfor-

ward as it may seem at first sight. The uncertainty increases when we

expect empirical evidence for a claim of a test at a certain CEFR level.

There is no real empirical evidence for what a language learner can

actually do at a certain level (Chapter 4 of the CEFR) nor for what the

given competencies of a learner are at a certain level (Chapter 5 of the

CEFR). Furthermore, there is no theory in the CEFR for what language

proficiency actually is and certainly not for L2 acquisition. However,

our main concern in the context of this Volume is that the CEFR, which

is essentially meant as a tool to promote plurilingualism, is used by

some policy makers as a scientific justification to promote monolin-

gualism in official state languages and to focus more on what newcom-

ers lack than on what they might be able to contribute and add in terms

of resources to a more diverse society (see also Stevenson, this Volume).

It is clear that the CEFR is not to blame for all of this, but it is important

to warn against its misinterpretation or misuse.

1.5 Structure and contents of this book

As it is impossible to deal with all aspects of testing regimes in cross-

national perspectives, we selected a total of 12 case studies for this

Volume. These case studies are grouped into two parts, 8 cases within

and across Europe and 4 cases outside Europe. Whereas Europe has

shifted from a continent of emigration to a continent of immigration,

immigrants from primarily European source countries have established

themselves in the nation-states in our selected cases abroad. The selec-

tion of European cases relies on the geographical spread of – larger

and smaller – EU countries and their official state languages from

Northern to Southern Europe. Furthermore, the cases selected cover

a wide spectrum ranging from rather liberal to very strict regimes of

admission, integration and (single or dual) citizenship, both across

countries (cf. Sweden vs. the Netherlands) and within countries (cf.

Flanders vs. Wallonia in Belgium). The selection made shows that the

testing regimes’ machinery varies not only in terms of geographical

space but also in terms of time (cf. the increasingly restrictive changes

in the access to citizenship in Australia). The common pattern across

nation-states is the emergence of increasing and increasingly complex

Testing regimes for newcomers

19

formal demands on knowledge of a/the national language and knowledge

of society. Key issues in all the contributions to this Volume are the

following:

which knowledge in these two domains is demanded by whom and

from whom?

how is this knowledge tested?

what are the implications of failure to pass?

Going from Northern to Southern Europe, the first part of this Volume

starts with an integrated chapter on the three Baltic Republics, all of

them being newcomers to the EU and having a historical contextuali-

zation which is very different from our other EU cases. What follows is

the Nordic example of Sweden with its rather liberal testing regime.

The United Kingdom and Germany are dealt with next and are followed

by three successive chapters on the BENELUX, Belgium, the Netherlands

and Luxembourg, respectively. The case of Belgium constitutes the

internally drawn crossing line between EU countries where Germanic

versus Romance languages are dominant. The Netherlands belongs to

the EU countries with the most complex and restrictive testing regimes

for newcomers, Belgium is a federal state with divergent integration

policies in Dutch-dominant Flanders and French-dominant Wallonia,

and Luxembourg is home to the highest proportion of foreign residents

in the EU, making up nearly half of the present population. The last

European case is Spain, an EU country with a recent and rapid shift

towards immigration after centuries of emigration. In the second part

of this Volume, we move to four non-European countries with a strong

history of immigration, in particular and at least initially from European

source countries. The USA and Australia are examples of English-

dominant immigration countries. Canada portrays itself as a bilingual

English-French immigration country with corresponding language

regimes. Finally, Israel is a Hebrew-dominant immigration country with

highly ideologically charged regimes on admission, integration and

citizenship as a consequence of the equation of (Jewish) ethnicity, reli-

gion and the concept of nation-state.

In her opening chapter, Gabrielle Hogan-Brun illustrates in great

detail how the language and citizenship laws that were enforced shortly

after the independence gained by the Baltic Republics in 2004 became

instrumental in determining citizenship applications based on an exam-

ination of language competence and cultural knowledge. By drawing

on a set of data taken from Latvia’s divided press, being both Russian-

and Latvian-medium, the author concludes that innocuous values –

generally based on recognition of norms relating to human rights and

z

z

z

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

20

tolerance for others – have quite an influence on the expectations the

majority of the people have with respect to minorities. That is, minori-

ties ought to conform to and be examined in their knowledge of the core

values of the Latvian nation-state.

The chapter on the Baltic Republics is followed by Lilian Nygren-

Junkin’s updated landscaping of the regulations surrounding immi-

gration, language and citizenship in Sweden. Because of an enduring

acquaintance of centuries with labour market immigration which has

left its marks on the Swedish language, and contrary to the more

general European trend, immigration and citizenship have only recently

become the subject of heated debate in Swedish politics. After having

secured permanent resident status – and with no serious governmental

attempt to ascertain citizenship through language testing – staying in

Sweden eventually brings the migrant to a stage where he or she can

file an application for citizenship.

In contrast to the more liberal Swedish approach to immigration,

Adrian Blackledge’s chapter considers the recently emerged symbiosis

among debates on English language and debates on immigration in the

United Kingdom. Blackledge ascertains that proficiency in English for

all UK residents together with fostering respect for and knowledge of

‘life in the United Kingdom’ are both seen as essentials for social cohe-

sion and modernist promulgation of national identity. Through a fine-

grained analysis of the recent discourse in the debate on language

testing for immigrants in the United Kingdom, Blackledge condemns

the fact that legislation does not draw a distinction between testing for

language proficiency on the one hand and language learning on the

other. Furthermore, he points out that legislation avoids any explicit

reference to the linguistic resources which immigrants bring along

upon their arrival on UK soil.

Patrick Stevenson and Livia Schanze’s chapter on Germany shares

Blackledge’s preoccupation with language debates and curricula aimed

at paying lip service to the nation-state integration agenda. The authors

explore the consequences of German unification by charting the ways

in which knowledge of German, the official language of a ‘modern’

country of immigration, has been called upon in migration and citizen-

ship debates. Their analysis acknowledges a significant shift in public

and political discourses in Germany with respect to the use of such

concepts as integration and inclusive citizenship. However, the authors

also point out that the newly drawn-up integration plan in Germany

still has to prove its adequacy in meeting its noble aims. The plan has

to prove whether it will manage to move away from an emphasis on

migrants’ deficiencies towards an emphasis on the potential they bring

in as new citizens.

Testing regimes for newcomers

21

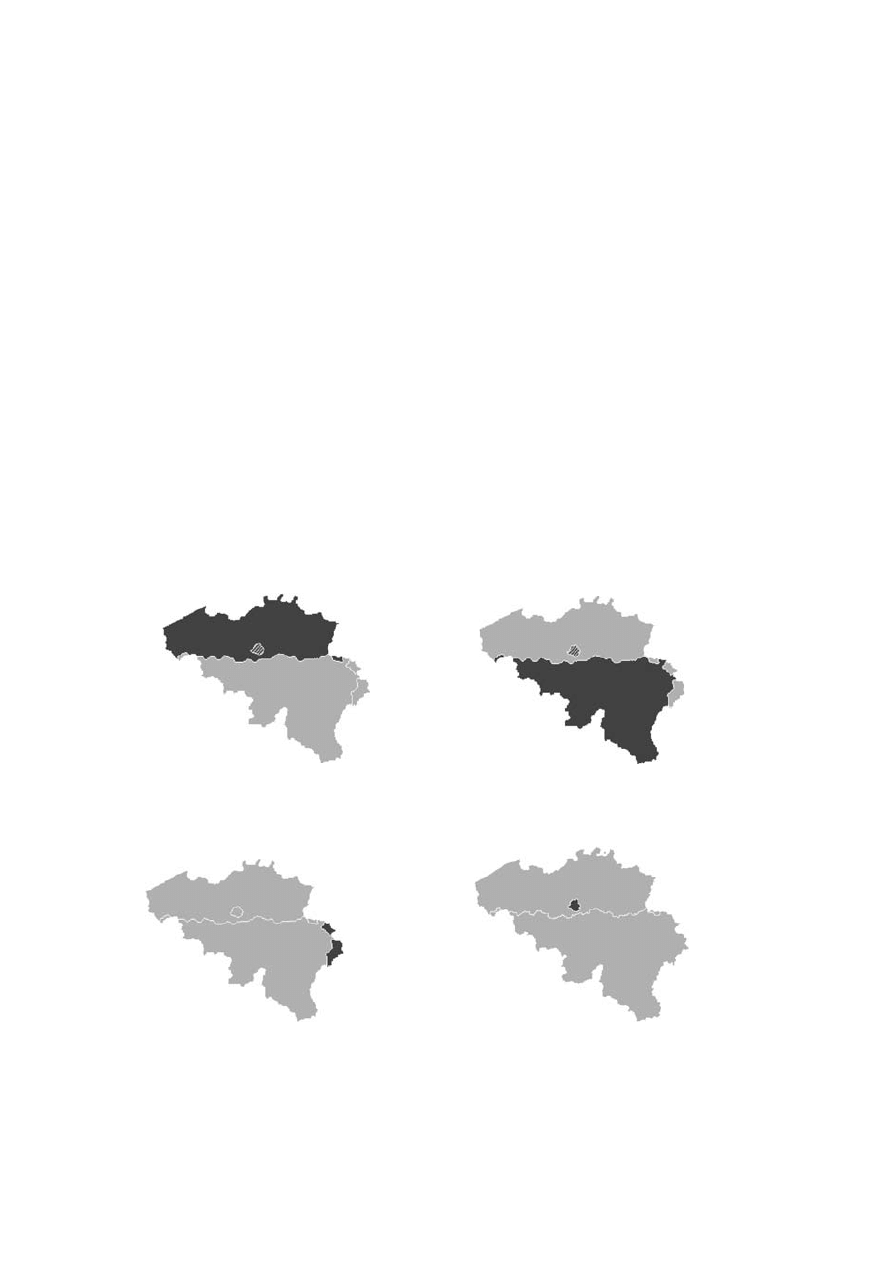

The United Kingdom and Germany are followed by Van Avermaet

and Gysen’s chapter, which analyses policies for integration and citi-

zenship of immigrants in the context of Belgium and of its three con-

stituent regions: Flanders, Wallonia and the Brussels Capital Region.

Although officially trilingual and indicated as a country with a high

level of linguistic consciousness, Belgium displays a deep diversity in

the approaches and responsibilities of its government bodies in terms

of immigration, integration, naturalization and citizenship. In their

chapter, it becomes very clear that instead of a unified Belgian model

for integration, we find two rather different approaches. More specifi-

cally, there is a difference in integration policies between the two major

regions as there is in the emphasis put on language proficiency as pivotal

to successful integration. The emphasis on integration and language

proficiency is stronger in Flanders than in Wallonia. This phenomenon

reflects a more Latin universalistic approach to language, migration

and territory for Wallonia and a more Anglo-Saxon differentialistic

approach for Flanders. A shift can thus be detected from language learn-

ing as a right towards language learning as an obligation. From what-

ever angle it is tackled, however, the burden of integration rests on the

shoulders of the immigrant.

The burden brought on by testing regimes weighs heavily on the

migrant’s shoulders in the chapter by Extra and Spotti that deals with

rites of passage that newcomers face from the very moment they wish

to enter the Netherlands up to the point where they may wish to apply

for citizenship. The authors venture into the jargon of Dutch civic inte-

gration that together with the political discourse before and after 2007

appears to have set the trend for many European countries and their

immigration policies. The authors also point out that what is demanded

from newcomers in terms of knowledge about Dutch society is not com-

mon knowledge shared by the ‘average’ Dutch citizen. Furthermore,

many native Dutch people still consider tolerance and openness as

characteristics that are part of their national identity. The view that

foreign observers have on these matters points to the opposite. As a

consequence of the strict measures and discourses adopted by its gov-

ernment, the Netherlands as a country is losing its image of tolerance

and cosmopolitanism.

Language, mobility and citizenship are again the focus of attention

in Kristine Horner’s chapter, in which she analyses the situation of the

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. In so doing, she presents a comprehen-

sive overview of the language debate that has characterized the Grand

Duchy’s history and the ideologies that have escorted Luxembourgish to

hold the number one position as the country’s national language. Further,

Horner outlines that Luxembourg is home to the highest proportion of

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

22

foreign residents in the EU, the majority of whom are holders of EU

passports. This compositional diversity of its population provides a

glimpse of the linguistic heterogeneity Luxembourg is confronted with

at present. Such embedded diversity stands in sharp contrast, however,

to the Luxembourg state approach to legal citizenship. Luxembourgish

and/or the emphasis on a trilingual ideal are instances of competing

indexical, or even iconic, features of authentic ‘Luxembourgishness’.

While the previous chapters were all focused on debates surround-

ing admission, integration and citizenship in countries with a relatively

long history of immigration, the chapter by Dick Vigers and Clare Mar-

Molinero widens the discussion to Spain, a country acquainted mainly

with emigration. The fact that Spain has faced a historical challenge

in the acknowledged coexistence of different languages spoken on its

territory is a well-known matter. Less known is the potential clash of

paradigms and destabilization that IM languages currently bring to the

Spanish sociolinguistic landscape, to its conception of language rights

and to its relationship with national identity. The authors argue that it

is for these reasons that the Spanish state has preferred adopting a more

reserved standpoint in matters of eligibility for citizenship and require-

ments for learning the so-called ‘national’ language.

Moving away from the European legacy presented in Part I of this

Volume, Part II grapples with matters of language testing for citizenship

outside Europe in contexts in which European immigrants at least ini-

tially played a major role in establishing such regimes. As a result, much

longer histories and documented experiences of testing regimes are

available in our case studies selected outside Europe. These histories

and experiences enhance our understanding of the conceptual presup-

positions surrounding the public and political debate on these issues

(see also Section 1). Tammy Gales, Lilian Nygren-Junkin, Tim McNamara,

Elana Shohamy and Tzahi Kanza confront the reader with language

testing for citizenship in non-European states that are often addressed

in the literature as immigrant countries par excellence from an early

European perspective of emigration: the United States of America, Canada,

Australia and Israel.

In her chapter, Tammy Gales spells out clearly that for non-US born

individuals, the path for becoming a naturalized citizen has remained

fairly consistent since the late nineteenth century. In terms of language

requirements, in fact, the acquisition of citizenship asks for a basic abil-

ity to read, write and speak the English language while English is no

officially declared national language. As a test for immigration though,

there are other, more indirect, tests at work under the guise of official

language policies that affect non-English-speaking immigrants on an

ongoing daily basis. Permanent residents in the US who do not speak

Testing regimes for newcomers

23

English are increasingly subject to tests that limit their public and pri-

vate life spheres and are shadowed by feelings of being unpatriotic or,

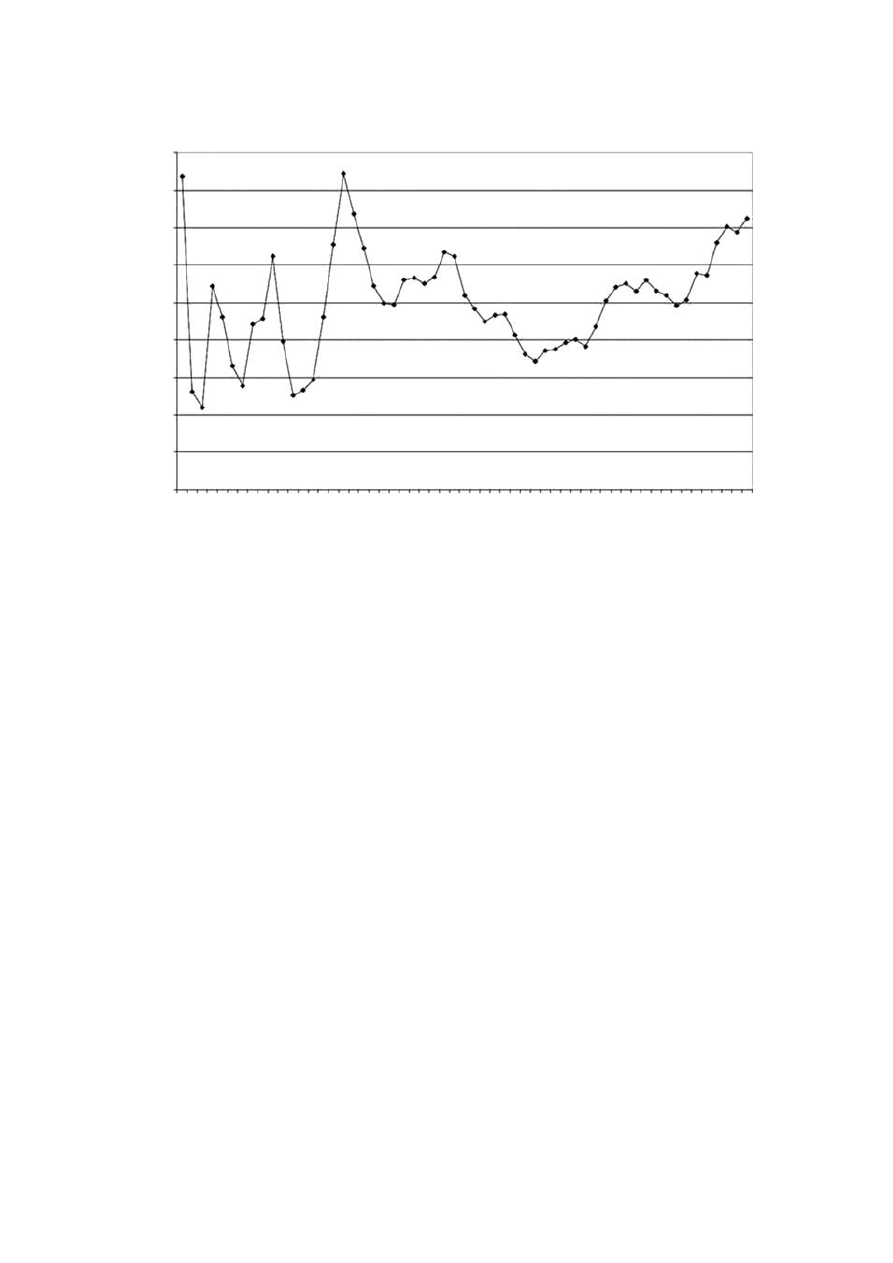

even worse, un-American.

As for Canada, Lilian Nygren-Junkin shows that Canadian citizenship

is based on the jus soli; having a Canadian father or mother, or both,

actually plays no role in conferring citizenship rights. Canadian multi-

culturalism makes for a generally tolerant and eclectic society. Nygren-

Junkin further explains that to become a Canadian citizen today, a

person must be someone who is legally entitled to permanent residence

and who has lived in Canada for at least three years without a criminal

record. The author then comments on recent developments of the

Canadian test for citizenship and teases apart the requirements a suc-

cessful applicant has to meet to be awarded citizenship.

In his chapter, Tim McNamara focuses on the policy shift and change

over time in test requirements in relation to immigration and citizen-

ship in Australia. More specifically, he focuses on the introduction of a

literacy requirement that has a suspicious precedent in other contexts,

that of the old Dictation Test. Although it is still early days to judge the

impact that the new test will bring, the response to its initial implemen-

tation and the controversy that has come along with it underscore the

role of Australian language testers. They, in fact, have much more criti-

cal soul searching to do as to whether and how they wish to participate

in the implementation of citizenship policies that involve overt and

covert language-based tests.

No better case than Israel could be taken as the conclusive chapter to

a Volume on language testing regimes. In their chapter, Elana Shohamy

and Tzahi Kanza discuss citizenship policies and their intermingling

with ethnicity and religion. Their chapter demonstrates how language

ideologies – the Hebrew language being a symbol of national and col-

lective identity of Jews in the creation of the state of Israel – serve

as conditions for citizenship and are adhered to even without official

tests. In the Israeli context, the authors argue for different levels and

different types of citizenship so that obtaining citizenship does not

entail complete social participation. The view of citizenship as essen-

tially ‘hollow’ also occurs with regards to immigrants for whom know-

ledge of Hebrew functions as a gatekeeper for full integration.

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

24

APPENDIX

Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), Council of Europe, Strasbourg

Understanding

Speaking

W

riting

Listening

Reading

Spoken

interaction

Spoken production

W

ri

ting

C2

I have no difficulty in

understanding any

kind of spoken

language, whether

live or broadcast,

even when

delivered at fast

native speed,

provided I have

some time to get

familiar with the

accent.

I can read with ease

virtually all forms of

the written

language, including

abstract, structurally

or linguistically

complex texts such

as manuals,

specialized articles

and literary works.

I can take part

effortlessly in any

conversation or

discussion and have

a good familiarity

with idiomatic

expressions and

colloquialisms. I

can express myself

fluently and convey

finer shades or

meaning precisely

.

If I do have a

problem I can

backtrack and

restructure around

the difficulty so

smoothly that other

people are hardly

aware of it.

I can present a clear

,

smoothly flowing

description or

argument in a

style appropriate

to the context and

with an effective

logical structure

which helps the

recipient to notice

and remember

significant points.

I can write clear

,

smoothly flowing text

in an appropriate

style. I can write

complex letters,

reports or articles

which present a case

with a effective

logical structure

which helps the

recipient to notice

and remember

significant points. I

can write summaries

and reviews of

professional or

literary works.

Testing regimes for newcomers

25

C1

I can understand

extended speech

even when it is not

clearly structured

and when

relationships are

only implied and

not signalled

explicitly

. I can

understand

television

programmes and

fi

lms without too

much effort.

I can understand long

and complex factual

and literary texts,

appreciating

distinctions of style.

I can understand

specialized articles

and longer technical

instructions, even

when they do not

relate to my fi

eld.

I can express myself

fluently and

spontaneously

without much

obvious searching

for expressions.

I can use language

flexibly and

effectively for social

and professional

purposes.

I can formulate ideas

and opinions with

precision and relate

my contribution

skillfully to those of

other speakers.

I can present clear

,

detailed

descriptions of

complex subjects

integrating sub-

themes,

developing

particular points

and rounding off

with an

appropriate

conclusion.

I can express myself in

clear

, well-structured

text, expressing points

of view at some

length. I can write

about complex

subjects in a letter

, an

essay or a report,

underlining what I

consider to be the

salient issues.

I can select style

appropriate to the

reader in mind.

(Continued

)

Guus Extra, Massimiliano Spotti and Piet Van Avermaet

26

Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR), Council of Europe, Strasbourg (Cond’d)

Understanding

Speaking

W

riting

Listening

Reading

Spoken

interaction

Spoken production

W

ri

ting

B2

I can understand

extended speech

and lectures and

follow even

complex lines of

argument provided

the topic is

reasonably familiar

.

I can understand

most TV news and

current affairs

programmes. I can

understand the

majority of films in

standard dialect.

I can read articles and

reports concerned

with contemporary

problems in which

the writers adopt

particular attitudes

or viewpoints. I can

understand

contemporary

literary prose.

I can interact with a

degree of fluency

and spontaneity that

makes regular

interaction with

native speakers

quite possible.

I can take an active

part in discussion in

familiar contexts,

accounting for and

sustaining my

views.

I can present clear

,

detailed

descriptions on a

wide range of

subjects related to

my field of

interest. I can

explain a

viewpoint on a

topical issue,

giving the

advantages and

disadvantages of

various options.

I can write clear

,

detailed text on a

wide range of subjects

related to my field of

interests. I can write

an essay or report,

passing on

information or giving

reasons in support of

or against a particular

point of view

. I can

write letters

highlighting the

personal significance

of events and

experiences.

Testing regimes for newcomers

27

B1

I can understand the

main points of clear

standard speech on

familiar matters

regularly

encountered in

work, school,

leisure, etc.

I can understand the

main point of many

radio or TV

programmes on

current affairs or

topics of personal or

professional interest

when the delivery is

relatively slow and

clear