Don Giovanni

Il dissoluto Punito

“Don Juan, The Rake Punished”

A dramma giocoso

Italian opera in Two Acts

by

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Libretto by Lorenzo da Ponte

Premiere in Prague, 1787

Adapted from the

Opera Journeys Lecture Series

by

Burton D. Fisher

Story Synopsis

Page 2

Principal Characters in the Opera

Page 2

Story Narrative with Music Highlights

Page 3

Mozart and Don Giovanni

Page 12

Opera Journeys Mini Guide Series

Published ©Copywritten by Opera Journeys

www.operajourneys.com

Don Giovanni Page 1

Story Synopsis

The opera story involves a 24-hour period in which

Don Giovanni’s attempts at seduction encounter

interference from avenging victims of his misdeeds: they

all seek divine retribution and punishment for the

dissolute rake.

Don Giovanni has surreptitiously entered the

apartment of Donna Anna. Her screams bring forth her

father, the Commendatore, who challenges the intruding

stranger to a duel. Don Giovanni kills the Commendatore,

and the grieving daughter, Donna Anna, swears revenge.

Country villagers celebrate the forthcoming marriage

between Zerlina and Masetto. Don Giovanni hosts a party

for the villagers so that he can have an opportunity to

seduce Zerlina, but he is thwarted in his attempts by the

arrival of the avenging Donna Anna, her fiance Don

Ottavio, and Donna Elvira, one of his earlier conquests

whom he later abandoned.

Leporello, in his master’s disguise, courts Donna

Elvira so that Don Giovanni can seduce her maid, but a

group of vengeful villagers foil his adventure.

Don Giovanni and Leporello escape to a cemetery

where a Stone Statue of the dead Commendatore arises

and demands that the licentious womanizer repent for

his sins.

Don Giovanni invites the Stone Statue to dinner,

refuses the Commendatore’s demand to repent, and

unable to free himself from the grasps of the Stone Statue,

is engulfed by the flames of Hell.

Principal Characters in the Opera

Don Giovanni,

a licentious Spanish nobleman

Baritone

Leporello, his servant

Baritone

Donna Anna, a noble lady

Soprano

The Commendatore, Donna Anna’s father Bass

Don Ottavio, Donna Anna’s fiance

Tenor

Donna Elvira, a noble lady from Burgos,

abandoned by Giovanni

Soprano

Zerlina, a peasant girl

Soprano

Masetto, Zerlina’s fiance

Baritone

TIME and PLACE: Seville, the 17

th

Century

Don Giovanni Page 2

Story Narrative with Music Highlights

Don Giovanni’s Overture begins highly dramatically

with solemn, imposing music that foretells the tragedy:

it is the music of the Commendatore’s death and the Stone

Statue; in the finale of the opera, the Commendatore

arrives at Giovanni’s banquet and leads him into the fires

of Hell. Musically, an andante emerges from the key of

D minor and develops into a brilliant allegro in D major,

establishing the opera’s subtle balance between comedy,

humor, and tragedy: the Overture suggests musically

that justice is in pursuit of the mercurial seducer.

Act I – Scene 1: Outside Donna Anna’s house at night

Don Giovanni, a noble of Spain, has set forth on a

daring adventure and has broken into the house of Don

Pedro, the Commandant of Seville, (the Commendatore),

intending to seduce his daughter, Donna Anna.

Leporello waits outside, doing sentry duty for his

master, and with rebellious indignation, comments on

his dreadful fate as a servant to his picaresque master.

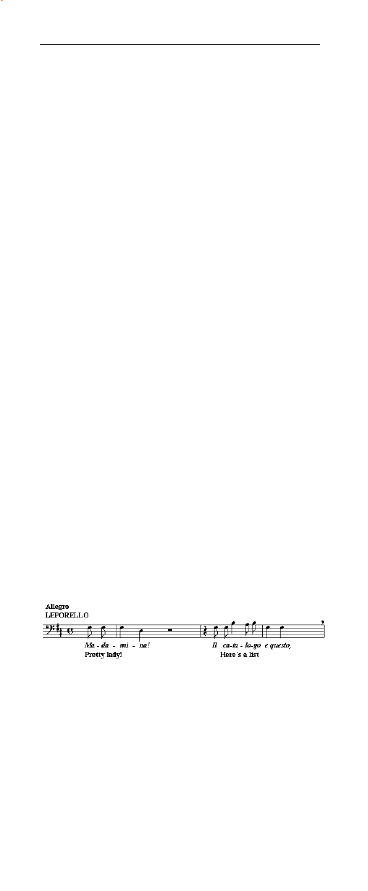

“Notte e giorno faticar” (“Night and day I am tortured”)

Don Giovanni is seen fleeing the palace, pursued by

Donna Anna who is desperately trying to unmask the

seducer, swearing he will pay dearly for his

transgression. After hearing Donna Anna’s screams, the

Commendatore appears sword in hand to defend his

daughter. The Commendatore challenges the stranger,

and in reluctant self-defense, Giovanni mortally wounds

the Commendatore. Seemingly unmoved by the corpse

on the ground, Giovanni flees the scene.

Donna Anna, horrified by her father’s death, joins

with her fiance, Don Ottavio, to swear revenge against

the murderer, both expressing their relentless

determination to pursue the unknown criminal and bring

him to justice. Donna Anna expresses her revenge and

condemnation of her assailant.

Donna Anna: “Fuggi crudele”

Don Giovanni Page 3

Act I - Scene 2: A street at dawn

Don Giovanni and Leporello roam the city in search

of new conquests. Donna Elvira is seen alighting from

a coach and is heard expressing sadness, hope, and

eventually outrage as she laments the treachery of her

faithless lover, Don Giovanni. She is determined to find

him, force him to return to her, and if she fails, she

threatens to inflict terrible torture on him. Elvira

comments about her betrayal and her obsessive mission:

“Ah! Chi mi dice mai quel barbaro dov’é?” (“Ah! How

shall I discover where this barbarian lives?”)

Don Giovanni, unaware of the woman’s identity,

approaches the lady in distress, and before he can offer

her consolation, finds to his consternation that she is

none other than Donna Elvira of Burgos, the woman he

had spurned some time ago; likewise, Elvira recognizes

Giovanni.

Giovanni tries to persuade her that he had justifiable

reasons for abandoning her, but Elvira refuses to believe

her betrayer nor accept his explanations. Giovanni

manages to escape the scene, leaving Leporello to provide

Elvira with an explanation.

Leporello pleads with the spurned woman to dispel

her anger: she is far from the first nor the last woman to

be jilted by his master. With pride, Leporello reads her

his master’s bulky catalogue of conquests and seductions:

in Italy 640, Germany 231, France 100, Turkey 91, but

in Spain 1003.

Leporello: “Madamina! Il catalogo è questo”

Leporello further explains to Donna Elvira that all

women appeal to his master, young or old, portly or

slender. “It’s his mission to win them all. And you, O

lady, are aware that he succeeds!”

He tries to persuade Donna Elvira that his master is

unworthy of her passion, and then runs off, leaving the

spurned and disheartened Elvira alone in grief.

Don Giovanni Page 4

Act I - Scene 3:

In the countryside near Don Giovanni’s palace

Country folk sing, dance, and praise the joys of life

and love. Don Giovanni learns of the approaching

marriage between Zerlina and Masetto, and generously

decides to place the marriage under his “protection.”

Giovanni has become enamored with Zerlina,

envisions her as his next conquest, and invites all the

peasants to his castle, including the bridegroom,

Masetto. Discretion becomes the better part of valor for

the protesting Masetto as Leporello escorts him away.

Masetto vents his frustration as he accedes to authority:

“ Ho capito, Signor, sì” (“Yes, my lord, I understand

you.”)

Alone with Zerlina, Giovanni tries to seduce her with

a serenade, surprising her with his suggestion that he

would marry her, and then suggests that they go to a

little house on the estate where they can be alone.

Giovanni and Zerlina:

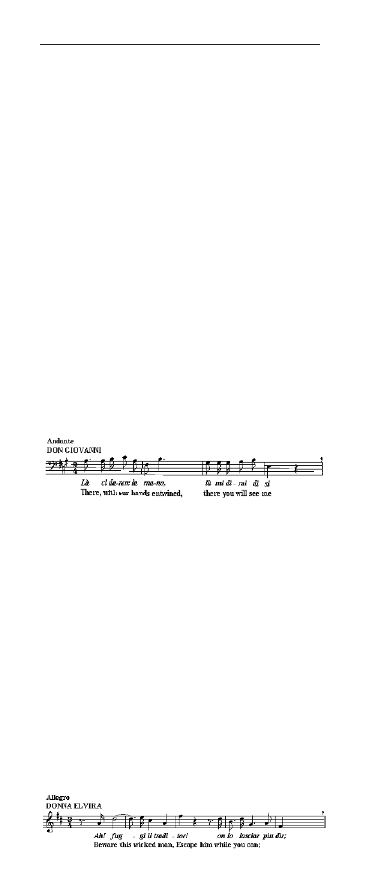

“Là ci darem la mano, là mi dirai di si”

Just as Zerlina is about to surrender to the seductive

charms of Don Giovanni, Donna Elvira suddenly

appears. She congratulates herself on arriving at such

an opportune time to save an innocent girl, and proceeds

to denounce the profligate Giovanni.

Zerlina anxiously asks Giovanni if Elvira’s

accusations are true, and he explains that the poor

unfortunate woman is in love with him, and because he

is kindhearted and selfless, he must humor her with the

pretense that he loves her.

Elvira warns Zerlina to beware of this man who will

betray her with lies and worthless promises. With

indignation, Elvira seizes Zerlina and leads her away

under her protection, warning her that she must defend

her honor against the lecherous nobleman.

Donna Elvira: “ Ah! Fuggi il traditor!”

Don Giovanni Page 5

Don Ottavio and Donna Anna arrive, but Anna does

not recognize her assailant from the night before and

unwittingly solicits Giovanni’s help and friendship. But

before Giovanni can ask the reason for her request,

Donna Elvira suddenly reappears, crying out

dramatically: “So, I find you again, perfidious monster!”

Elvira proceeds to warn Anna not to have faith in this

man who would betray her: “Non ti fidar, o misera” (“Do

not have faith in this miserable man.”)

Donna Anna and Don Ottavio become moved by

Donna Elvira’s tears: Giovanni tells them in an aside

that the poor woman is mad, and perhaps he can calm

her. But Donna Anna and Don Ottavio become confused

and do not know whom to believe. Elvira storms away,

and Giovanni quickly announces that he must follow the

poor unfortunate woman: his excuse to bid farewell to

Anna and Ottavio.

Donna Anna has a revelation and is now convinced,

through Giovanni’s voice and manner, that she recognizes

her assailant and her father’s murderer from the night

before. She proceeds to narrate the details of the evening

to Don Ottavio, and then beseeches Ottavio to join her

in revenge.

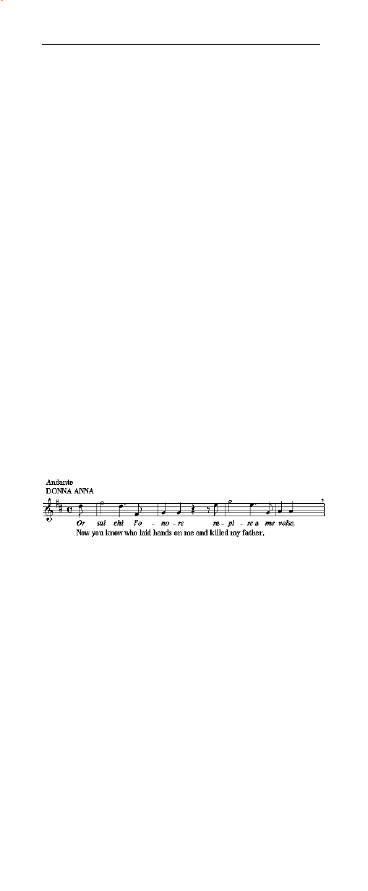

Donna Anna: “Or sai chi l’onore rapire a me volse”

After Anna’s furious proclamations of vendetta,

revenge, she storms away, leaving Ottavio alone to

reflect. He has never heard of a cavaliere capable of so

black a crime, and swears by his duty as lover and friend

to vindicate Donna Anna’s honor: “Dalla sua pace la

mia dipende” (“On her peace of mind mine too depends;

what pleases her gives joy to me.”)

Act I - Scene 4: A terrace before Don Giovanni’s castle

Don Giovanni, obsessed in his pursuit of Zerlina,

has invited all the peasants to his castle for a night of

merriment.

Giovanni, in the exuberant Champagne aria,

commands Leporello to round up the guests for the party.

Don Giovanni Page6

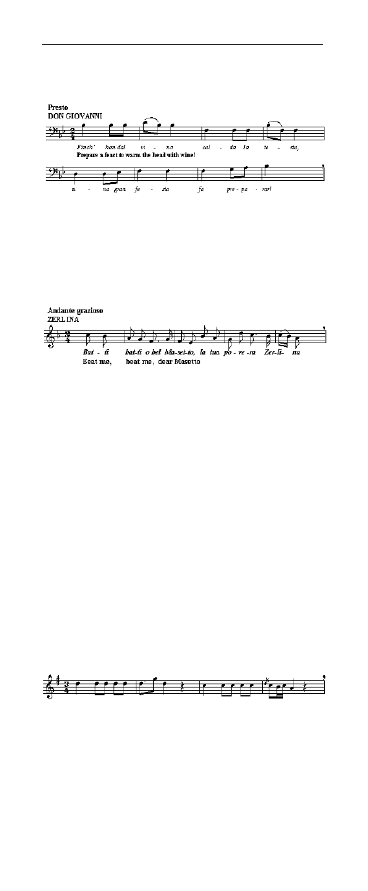

Don Giovanni: “Finch’han dal vino calda”

Meanwhile, Zerlina and Masetto argue, her fiance

accusing her of being unfaithful and abandoning him on

their wedding day. Zerlina claims innocence, and tries

to pacify her outraged and jealous fiance.

Zerlina: “Batti, batti, o bel Masetto”

Don Giovanni arrives in an expansive and hospitable

mood, finds Zerlina, and persuades her to disappear with

him into the arbor, but his intrigue is thwarted when he

finds the implacable Masetto hiding there. In frustration,

Giovanni escorts them both to his ball in the castle.

Suddenly, a trio of masked avengers arrives: Donna

Anna, Don Ottavio, and Donna Elvira, all determined to

invade the ball, capture Don Giovanni, expose his

wickedness, and punish him. Leporello, believing that

the three figures are guests in masquerade, on Giovanni’s

instructions, welcomes them in to the ball.

Act I - Scene 5:

The ballroom in Don Giovanni’s castle

The Minuet:

The three masked avengers have joined the dancing

at the ball. Don Giovanni becomes preoccupied with his

attempt to seduce the apprehensive Zerlina, coerces her,

and both disappear through one of the doors of the

ballroom. When Zerlina screams, the dancing stops, the

peasants hurriedly leave the scene, and the three masked

avengers break down the door to rescue Zerlina. Zerlina

is returned to safety and the avengers advance upon Don

Don Giovanni Page 7

Giovanni, crying out: “Tremble! Soon the whole world

will know of your black and terrible deed and of your

inhuman cruelty. Hark to the thunder of vengeance!”

Giovanni firmly announces that he fears nothing and

nobody, forces his way past the avengers, and escapes

with his faithful servant Leporello.

Act II - Scene 1: In front of Donna Elvira’s house

In a moment of pleading righteousness, Leporello

threatens to leave Giovanni’s service, urging his master

to give up his wasteful existence, but Giovanni’s

philosophical explanation that seduction is the bread of

his life, together with money, assuage the rebellious

servant.

Don Giovanni has now become fascinated with

Donna Elvira’s maid. To clear the way for this new

adventure, he must draw Elvira away: Giovanni and

Leporello exchange cloaks and hats; in the disguise of

his master, Leporello will court Elvira.

Elvira appears at her window, and reflects on her

bewildered feelings, praying that her heart stops yearning

for the man she knows is a liar and deceiver, but whom

she still loves and cannot give up.

Giovanni takes a position behind Leporello, now

dressed in his master’s cloak and hat, and Giovanni, the

voice behind Leporello, answers the vulnerable Elvira

with seductive flattery and endearments, prayers for

forgiveness, and promises of true love. Elvira falls into

Giovanni’s trap, and imagines the voice she hears belongs

to the figure she mistakes for Giovanni: her resistance

and defenses break down, and she descends from her

balcony to join the man she thinks is her lover.

Elvira passionately embraces her lover (Leporello);

the servant thoroughly enjoying the charade and the

impersonation of his master. Giovanni creates a

disturbance, Leporello’s cue to flee with the frightened

Elvira. With Elvira gone, Giovanni is left alone to

serenade Elvira’s maid in peace.

Don Giovanni: “Deh vieni alla finestra, o mio tesoro”

Don Giovanni Page 8

Don Giovanni’s attempted romantic escapade with

Elvira’s maid is interrupted by a band of armed peasants

in search of him: their leader is the pistol-waving

Masetto. But Giovanni, still in the disguise of his servant,

Leporello, is taken into their confidence and proceeds to

give them false directions to find the rascal: the peasants

proceed to scatter throughout the city in search of

Giovanni.

Giovanni remains behind with Masetto and invites

him to show him his weapons. When the naïve Masetto

hands over his musket and pistol, he is defenseless, and

Giovanni thrashes him before disappearing into the night.

Zerlina arrives and discovers an unhappy Masetto

groaning in pain. She gives him solace, and promises

him a cure that will restore him to health: the cure is her

love.

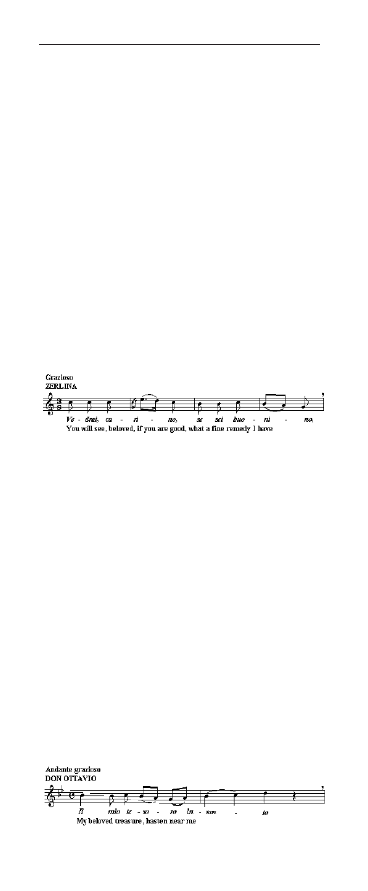

Zerlina: “Vedrai, carino, se sei bonino”

Act II - Scene 2:

A courtyard before Donna Anna’s house

Leporello leads the apprehensive Elvira into a

darkened courtyard to seek refuge from their pursuers.

Donna Anna, Don Ottavio, and then Zerlina and Masetto

appear, all of them still in search of Don Giovanni. They

believe they have discovered him (Leporello in disguise)

and demand death to the perfidious villain. They are

about to kill the unfortunate servant, but with terrified

pleas and supplications, Leporello dissuades them, and

then miraculously escapes.

Alone, Don Ottavio vows to comfort his beloved by

bringing Don Giovanni to justice.

Don Ottavio: “Il mio tesoro”

Don Giovanni Page 9

Donna Elvira returns, and in a moment of self-pity,

again expresses her sadness: Mi tradi quell’anima

ingrata, “I was betrayed by that ungrateful soul.”

Act II - Scene 3: A cemetery with equestrian statues,

among them the marble statue of the Commendatore

Don Giovanni and Leporello, fugitives from all the

avengers, meet in the safety of a cemetery. Suddenly,

they are interrupted by a sinister voice coming from a

Stone Statue: “Your jests will turn to woe before

morning!”

Looking around, Giovanni notices the

Commendatore’s equestrian statue and commands

Leporello to read its inscription: “Vengeance here awaits

the villain who took my life.” Giovanni instructs

Leporello to invite the Stone Statue to supper. The Statue

nods its head in acceptance, and then Giovanni personally

extends the invitation: the Statue accepts with a solemn

“yes.”

Don Giovanni, burning with defiance, goes home to

prepare for the arrival of his strange guest. Leporello

accompanies him, sensing a forewarning of doom.

Act II - Scene 4: A room in Donna Anna’s house

Donna Anna continues to mourn for her father,

advising the consoling Don Ottavio that they cannot wed

until her father’s murder has been avenged. Ottavio

interprets her postponement as cruelty.

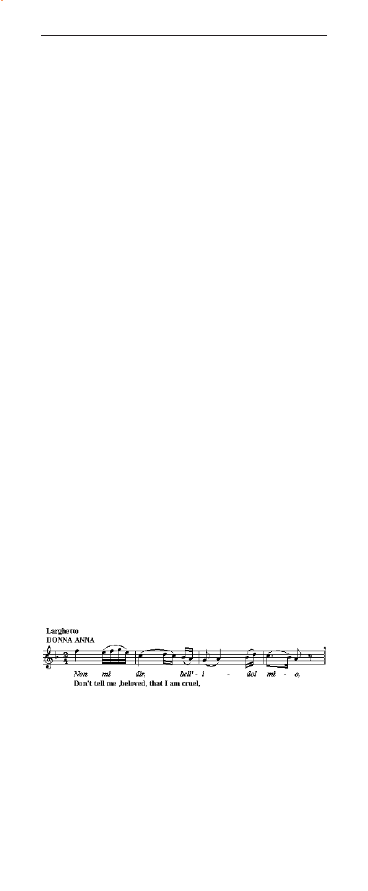

Donna Anna: “Non mi dir, bell’ idol mio”

Act II - Scene 5: The dining hall in Don Giovanni’s

palace.

In an expansive and hospitable mood, Don Giovanni

prepares for a terrifying confrontation with his guest.

Donna Elvira, agitated and desperate, appears to

warn her beloved that he is in danger, further proving

Don Giovanni Page10

her love for him by forgiving him, and begging him to

change his life. Elvira falls on her knees, and pleads with

him to repent, but Giovanni loses patience with her, and

excuses her: now spurned again, she curses him as a

“horrible example of iniquity.”

A knocking is heard at the door and a fearful

Leporello hides under a table. Giovanni opens the door,

and returns followed by the Stone Statue of the

Commendatore: the Stone Statue’s entrance is

accompanied by the music from the first bars of the

Overture.

The Stone Statue refuses Giovanni’s offer to dine

with him, but grasps Giovanni’s hand and urges him to

mend his ways and repent. Giovanni struggles frantically

and in vain to free himself from the Statue’s grip,

defiantly refusing to repent.

Flames envelop the hall and voices of demons are

heard: the forces of damnation denounce Don Giovanni,

and with a final cry of despair, Don Giovanni is

swallowed up by the fires of Hell.

Epilogue:

The entire group of avengers arrive: Masetto and Zerlina,

Don Ottavio and Donna Anna, and the lonely Donna

Elvira, all unanimous in their lustful eagerness to show

their contempt and hatred for the perfidious Don

Giovanni. Leporello proceeds to provide the bloodthirsty

avengers with a detailed account of the demise of his

master.

Donna Anna and Don Ottavio suggest that all their

troubles have been resolved by divine intervention, and

she advises Ottavio that she will remain in mourning for

an entire year: her marriage to Ottavio will therefore be

postponed and be reconsidered afterwards.

Donna Elvira announces that she will retire to a

convent. Zerlina and Masetto decide to return home: to

dine. Leporello declares that he has but one practical

alternative: he will go to the tavern and seek a new

master.

All join and celebrate the demise of the wrongdoer:

divine justice has been victorious!

Don Giovanni Page11

Mozart and Don Giovanni

W

olfgang Amadeus Mozart – 1756 to 1791 - was

born in Salzburg, Austria. His life-span was brief,

but his phenomenal musical achievements have

established him as one of the most important and inspired

composers in Western history: music seemed to gush

forth from his soul like fresh water from a spring. With

his death at the age of thirty-five, one can only dream of

the musical treasures that might have materialized from

his music pen.

Along with Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van

Beethoven, Mozart is one of those three “immortals” of

classical music. Superlatives about Mozart are

inexhaustible: Tchaikovsky called him “the music

Christ”; Haydn, a contemporary who revered and idolized

him, claimed he was the best composer he ever knew;

Schubert wept over “the impressions of a brighter and

better life he had imprinted on our souls”; Schumann

wrote that there were some things in the world about

which nothing could be said: much of Shakespeare,

pages of Beethoven, and Mozart’s last symphony, the

forty-first.

Richard Wagner, who emphasized orchestral power

in his music dramas, assessed Mozart’s symphonies: “He

seemed to breathe into his instruments the passionate

tones of the human voice ... and thus raised the capacity

of orchestral music for expressing the emotions to a

height where it could represent the whole unsatisfied

yearning of the heart.”

Although Mozart’s career was short, his musical

output was tremendous by any standard: more than 600

works that include forty-one symphonies, twenty-seven

piano concertos, more than thirty string quartets, many

acclaimed quintets, world-famous violin and flute

concertos, momentous piano and violin sonatas, and, of

course, a legacy of sensational operas.

Mozart’s father, Leopold, an eminent musician and

composer in his own right, became, more importantly,

the teacher and inspiration to his exceptionally talented

and incredibly gifted prodigy child. The young Mozart

demonstrated a thorough command of the technical

resources of musical composition: at age three he picked

out tunes on the harpsichord; at age four he began

composing; at age six he gave his first public concert;

by age twelve he had written ten symphonies, a cantata,

Don Giovanni Page12

and an opera; at age thirteen he toured Italy, where in

Rome, he astonished the music world by writing out the

full score of a complex religious composition after one

hearing.

During the late eighteenth-century, a musician’s

livelihood depended solidly on patronage from royalty

and the aristocracy. Mozart and his sister, Nannerl, a

skilled harpsichord player, frequently toured Europe

together, and performed at the courts of Austria, England,

France, and Holland. But in his native Salzburg, Austria,

he felt artistically oppressed by the Archbishop and

eventually moved to Vienna where first-rate

appointments and financial security emanated from the

adoring support of both the Empress Maria Thèrése, and

later her son, the Emperor Joseph II.

Opera legend tells the story of a post-performance

meeting between Emperor Joseph II and Mozart in which

the Emperor commented: “Too beautiful for our ears

and too many notes, my dear Mozart.” Mozart replied:

“Exactly as many as necessary, Your Majesty.”

M

ozart said: “Opera to me comes before everything

else.” During the late eighteenth-century, opera

genres consisted primarily of the Italian opera seria,

opera buffa, and the German singspiel.

Opera seria defines the style of serious Italian operas

whose subjects and themes dealt primarily with

mythology, history, and Greek tragedy. In this genre, the

music drama usually portrayed an heroic or tragic

conflict that typically involved a moral dilemma, such

as love vs. duty, and usually resolved happily with due

reward for rectitude, loyalty, and unselfishness.

Opera buffa was an Italian genre of comic opera

that, like its predecessor, the commedia dell’arte,

presented satire and parodies about real-life situations:

the commedia dell’arte was a theatrical convention that

evolved during the Renaissance and had been performed

by troupes of strolling players; their satire and irony

would ridicule every aspect of their society and its

institutions through the characterization of humorous or

hypocritical situations involving cunning servants,

scheming doctors, and duped masters.

In Mozart’s time, opera buffa was perhaps the most

popular operatic form, its life continuing well into the

nineteenth century in the hands of Rossini and Donizetti.

German singspiel, similar to Italian opera buffa, was

specifically comic opera but with spoken dialogue.

Social upheavals and ideological transitions were

Don Giovanni Page13

brewing in Mozart’s time as the end of the eighteenth

century would become inspired by the Enlightenment,

and would later witness the American and French

Revolutions. Mozart delighted in portraying themes in

which the common man fought for his rights against the

tyranny and oppression of the aristocracies. In particular,

his opera buffa, The Marriage of Figaro, portrays

servants more clever than their selfish, unscrupulous,

and arrogant masters. Napoleon would later conclude

that Marriage, both the Mozart and source Beaumarchais

play, was the “Revolution in action.”

Opera buffa provided a convenient theatrical vehicle

in which the ideals of democracy could be expressed in

art. Whereas the aristocracy identified and became

flattered by the exalted personalities, gods, and heroes

portrayed in the pretentious pomp and formality of the

opera seria, the satire and humor of opera buffa,

provided an arena to express the frustrations of the lower

classes of society.

Mozart wrote over eighteen operas, among them:

Bastien and Bastienne (1768); La finta semplice (1768);

Mitridate, Rè di Ponto (1770); Ascanio in Alba (1771);

Il Sogno di Scipione (1772); Lucio Silla (1772); La Finta

Giardiniera (1774); Idomeneo, Rè di Creta (1781); Die

Entführung aus dem Serail (The Abduction from the

Seraglio) (1782); Der Schauspieldirektor (1786); Le

Nozze di Figaro, (The Marriage of Figaro) (1786); Don

Giovanni (1787); Così fan tutte (1790); Die Zauberflöte

(The Magic Flute) (1791); La Clemenza di Tito (1791).

D

uring Mozart’s time, the Italians set the international

standards for opera: Italian was the universal

language of music and opera, and Italian opera was what

Mozart’s Austrian audiences and most of the rest of

Europe wanted most. Therefore, even though Mozart

was an Austrian, his country part of the German Holy

Roman Empire, most of Mozart’s operas were written

in Italian.

His most popular Italian operas were: The Marriage

of Figaro, “Le Nozze di Figaro,” an opera buffa that

represented his first collaboration with his most famous

librettist, Lorenzo Da Ponte; Don Giovanni, technically

an opera buffa but designated a dramma giocoso, a

“humorous drama” or “playful play,” essentially a

combination of both the opera buffa and opera seria

genres; Così fan tutte, “Thus do all women behave,”

another blend of the opera seria with the opera buffa,

Don Giovanni Page14

and Mozart’s last opera, La Clemenza di Tito, “The

Clemency of Titus,” an opera seria commissioned to

celebrate the coronation in Prague of the Emperor

Leopold II as King of Bohemia. Nevertheless, Italians

have historically shunned Mozart’s Italian works,

claiming they were not “Italian” enough; a La Scala

production of a Mozart “Italian” opera is a rare event.

Mozart’s most popular German operas are: Die

Zauberflöte, “The Magic Flute,” and Die Entführung

aus dem Serail, “The Abduction from the Seraglio.” Both

operas are stylistically singspiel works. Mozart’s operas

receive the same extravagant praise as his instrumental

music, but Mozart’s characterizations are considered to

capture a sublime unity of both the smiles and tears of

life. To some, Don Giovanni is the finest opera ever

written; some prefer The Magic Flute; and still others

choose The Marriage of Figaro, and nothing could be

more praiseworthy than the musicologist William Mann’s

conclusion that Così fan tutte contains “the most

captivating music ever composed.”

The world of Mozart addicts will argue vociferously

about which is his best opera: Così fan tutte, considered

to be his most exquisite, sophisticated, and subtle work;

The Marriage of Figaro, sometimes called the perfect

opera buffa, and his most inspired because of the comic

effectiveness of its political and social implications; or

Don Giovanni, because of its alternation of the light and

comic with the darker colors of genuine tragedy.

M

ozart was unequivocal about his opera objectives:

“In an opera, poetry must be altogether the

obedient daughter of the music.” Nevertheless, he indeed

took great care in selecting that poetry, hammering

relentlessly at his librettists to be sure they produced

words that could be illuminated and transcended by his

music. To an opera composer of such incredible genius

as Mozart, words performed through music expressed

what language alone had exhausted.

Musically, Mozart’s works epitomize the Classical

style of the late eighteenth-century, the goal of which

was to conform to specific standards and forms, to be

succinct, clear, and well balanced, while at the same time,

developing ideas to a point of emotionally satisfying

fullness. As a quintessential Classicist, Mozart’s music

combines an Italian taste for graceful melody with a

German proclivity for formality and contrapuntal

ingenuity.

Don Giovanni Page15

Mozart is considered the consummate master of

translating “dramatic truth” into his music: that is the

vital element in his music, a language which ingeniously

portrays complex human emotions, passions, and

feelings. Opera, or “music drama,” by its very nature, is

essentially an art form concerned with the emotions and

behavior of human beings: the success of an opera lies

in its ability to convey a realistic panorama of human

character through its music. Mozart understood his

fellow human beings, and ingeniously translated that

insight through his musical language.

Mozart’s ingenious ability to bare the soul of his

characters was almost Shakespearean: his musical

characterizations are truthful representations of universal

humanity; in those characterizations, we sense virtues,

aspirations, inconsistencies, peculiarities, flaws and

foibles. Mozart virtually tells it like it is, rarely suggesting

any puritanical judgment or moralization of his

characters’ behavior and actions, prompting Beethoven

to lament that in Don Giovanni and Marriage, Mozart

had squandered his genius on immoral and licentious

subjects.

Nevertheless, that spotlight on the individual makes

Mozart a bridge between eighteenth and nineteenth

century operas. Before him, in the opera seria genre,

operas portrayed abstract emotion. But Mozart was

anticipating the transition to the Romantic movement

and its accent on sentiments and feelings that was to

begin soon after his death. As such, Mozart’s

characterizations made opera come alive by endowing

his characters with definite and distinctive musical

personalities.

In earlier works, like Gluck’s opera serias, the

dramatic form would imitate the style of the Greek

theater: an individual’s passions and the dramatic

situations would generally transfer to the chorus for either

narration, commentary, or summation. But Mozart

replaced those theatrical devices, and brilliantly

portrayed the interaction between the characters

themselves, particularly in his ensembles: his ensembles

are almost symphonic in grandeur, moments in which

an individual character’s emotions, passions, feelings,

and reactions stand out in high relief.

Mozart was therefore the first composer to perceive

clearly the vast possibilities of the operatic form as a

means of musically creating characters: great and small

characters who moved, thought, and breathed on the

human level; Mozart’s characters discard the masks of

Don Giovanni Page16

Greek drama and appear as individuals with recognizable

personalities. Those extraordinary, insightful, musical

characterizations, are ingenious portrayals of real and

complex humanity in their conduct and character. As a

consequence, audiences have been enthralled for over

two-hundred years with his characterizations: Don

Giovanni’s Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, Zerlina, Masetto,

Leporello, and Don Giovanni himself; The Marriage of

Figaro’s Count and Countess, Cherubino, Susanna, and

Figaro. All Mozart characters are profoundly human:

they act with passion, yet they retain those special

Mozartian qualities of dignity and sentiment.

In the end, like Shakespeare, Mozart’s

characterizations have become timeless representations

of humanity. His opera characterizations are as

contemporary in the twentieth-century as they were in

the later part of the eighteenth century, even though

costumes, and even some customs may have changed.

So Count Almaviva, in The Marriage of Figaro,

attempting to exercise his feudal right of droit du

seigneur, may be no different than a wealthy twentieth

century chief executive living in his Connecticut

mansion: legally forbidden to bed his illegal alien

housekeeper against her wishes.

To achieve those spectacular results in musical

characterization, Mozart became a magician in

developing and using various techniques in his musical

language in order to portray and communicate passions

such as envy, revenge, or noble love. He expressed those

qualities through distinguishing melody, through the

specific qualities of certain key signatures, through

rhythm, tempo, pitch, and even through accent and

speech inflection.

Mozart excels in his genius for using musical keys

for effect; often, G major is the key for rustic life and

the common people; D minor, appearing solemnly in

the Overture and final scene of Don Giovanni, is his key

for Sturm und Drang, (storm and stress); A major, the

seductive key for sensuous love scenes. When characters

are in trouble, they sing in keys far removed from the

home key: as they get out of trouble, they return to that

key, reducing the tension.

Mozart’s theatrical genius in his ability to express

those truly human qualities in music endows his character

creations with a universal and sublime uniqueness; in

the end, an incomparable immortality for both composer

and his achievements.

Don Giovanni Page17

The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così

fan tutte, were composed during the late eighteenth

century social and political upheavals. This Da Ponte-

Mozart trilogy satirically deals with despicable aspects

of human character whose transformation was the very

focus of the Enlightenment idealism which precipitated

the French Revolution itself.

The engines that drive the plots of The Marriage of

Figaro and Don Giovanni are the moral foibles and

peccadillos of aristocratic men: Count Almaviva and

Don Giovanni are the nobility who can almost be

perceived by modern standards as criminals: men who

are unstable, wildly libidinous, and men who feel

themselves above the law. Similarly, in Così fan tutte,

the actions of the women can be perceived as

transcending moral law.

The themes of all three works focus on seduction:

seduction that ends in hapless failure: On Mozart’s stage,

these flawed individuals stand in the center of a symbolic

ideological bridge between the eighteenth century

Enlightenment and nineteenth century Romanticism, so

the actions of these despicable men represent a subtle

forecast to those social upheavals and perhaps the

greatest ideological transition in Western history: the

demise of the ancien regime.

In Mozart’s Don Giovanni and The Marriage of

Figaro, social classes clash on the stage with sentiment

and insight: Mozart’s musical characterizations range

in his operas from underdogs to demigods, but when he

deals with peasants and the lower classes, he is subtle,

compassionate, and loving. So Mozart’s heroes become

those bright characters who occupy the lower stations,

those Figaros, Susannas, and Zerlinas, characters whom

he ennobles with poignant musical portrayals of their

complex personal emotions, feelings, hope, sadness,

envy, passion, revenge, and eternal love.

T

he commission for Don Giovanni followed the

triumphant productions of The Marriage of Figaro

in both Vienna and Prague in 1786. Although those Don

Juan plays, which had derived from legends, were

considered by the aristocracy to have descended to the

level of vulgarity, Prague was not directly under the

control of the imperial Hapsburgs. Therefore, censorship

and restriction of underlying elements of its story was

limited, if nonexistent.

Don Giovanni Page18

For Don Giovanni, Mozart again chose as his

librettist that peripatetic scholar and entrepreneur, the

man who had supplied the texts for The Marriage of

Figaro, and later Così fan tutte, Lorenzo da Ponte, that

erstwhile crony of the notorious Casanova de Seingalt,

reputedly his assistant for selected sections of the Don

Giovanni libretto.

Da Ponte was born in Italy in 1749, and died in

America in 1838. He was born Emmanuel Conegliano,

converted from Judaism, and was later baptized, taking

the name da Ponte in honor of the Bishop of Ceneda. Da

Ponte would take holy orders in 1773, but seminary life

failed: his subsequent picaresque life as described in his

biography bears an uncanny resemblance to that of his

libertine romantic hero, Don Giovanni.

Da Ponte was always involved in scandals and

intrigues, at one time banished from Venice, and later

forced to leave England under threat of imprisonment

for financial difficulties. In 1805, he came to the United

States, taught Italian at Columbia University where he

introduced the Italian classics to America, and later

became an opera impresario who in 1825, may have been

the first to present Italian opera in the United States.

In Da Ponte’s haughty Extract from the Life of

Lorenzo Da Ponte (1819), he explains why Mozart chose

him as his inspirational poet: “Because Mozart knew

very well that the success of an opera depends, first of

all, on the poet…..that a composer, who is, in regard to

drama, what a painter is in regard to colors, can never

do without effect, unless excited and animated by the

words of a poet, whose province is to choose a subject

susceptible of variety, movement, and action, to prepare,

to suspend, to bring about the catastrophe, to exhibit

characters interesting, comic, well supported, and

calculated for stage effect, to write his recitativo short,

but substantial, his airs various, new, and well situated;

and his fine verses easy, harmonious, and almost singing

of themselves…..”

Certainly, in Da Ponte’s librettos for Mozart operas,

he indeed ascribed religiously to those literary and

dramatic disciplines and qualities he so eloquently

described and congratulated himself for in his

autobiography.

G

oethe testified to the popularity and drawing power

of the Don Giovanni stories among the common

people when he witnessed an opera on the subject in

Rome in 1787: “There could not have been a soul alive

Don Giovanni Page19

(in Rome, right down to the greengrocer and his children)

who had not seen Don Juan roasting in Hell, and the

Commendatore, as a blessed spirit, ascending to

Heaven.”

Don Juan legends and myths trace their genesis, like

the Faust story, to the exploits of a personage who

actually lived. The tale concerns itself with Don Juan, a

member of the noble Tenorio family who in the fourteenth

century, is reputed to have been a perpetrator of plots

against all of the womanhood of Seville.

The first play to reach the stage was by the Spanish

dramatist, Gabriel Tellez (1584-1648), who wrote under

the pseudonym Tirso de Molina: his play, El Burlador

de Sevilla y Convivado de Piedra, “The Rake of Seville

and the Stone Guest.” In the play’s finale, Don Juan

brazenly invites the Stone Guest to dine with him, and

to his consternation, the statue accepts and bids that they

dine in a nearby chapel: the dishes at their supper contain

scorpions and snakes, the wine is gall and verjuice, the

table music a penitential psalm, and then the statue

vanishes, and Don Juan is consigned to Hell.

Also providing underlying fabric for the ultimate

Da Ponte/Mozart story are Molière’s Le Festin de Pierre

(1665), “The Feast of Stone,” or its equivalent, Righini’s

Il convitato di pietra ossia Il dissoluto punito (1776),

the German Comödie Das steinerne Gastmahl (1760),

and Gluck’s pantomime ballet Don Juan, ou Le festin

de pierre (1761). Moliére’s play, in particular, aroused

great controversy owing to the religious and social

questions explored: Don Juan’s atheism and lack of

gallantry toward the poor was deemed to be un-Catholic

and un-Spanish, not to mention his sins of rape and

seduction.

The eighteenth-century plays of the very popular

Carlo Goldoni were noted for their wit and skill in

satirizing social pretension, and Goldoni himself treated

the subject in his play, Don Giovanni Tenorio, o sia Il

dissoluto (1736), his particular innovations that Donna

Anna was betrothed to Don Ottavio against her will, and

the introduction of Donna Elvira, the presumably mad

woman who continuously interferes with the

protagonist’s seductive adventures.

However, Da Ponte’s basic framework for his

libretto for Mozart’s opera was Bertati’s contemporary

one-act opera, Don Giovanni, or sia il convitato di pietra

(1787), musically scored by Giuseppe Gazzaniga, a

highly prolific and esteemed opera composer.

Don Juan stories about the libertine rake of legend

Don Giovanni Page 20

were from their very beginnings extremely popular

medieval morality plays. Certainly, during the God-

centered Middle Ages when society literally lived

between hell and damnation, it became a popular vehicle

for strolling puppet theaters whose audiences relished

its allegorical struggle and conflict between the forces

of good and evil.

Don Juan is a rebel against conventional morality,

a dissolute sinner, a promiscuous, treacherous, and

murderous man, who, by the demands of a morality play,

must receive divine justice and be punished. He is a

fatally flawed character, yet he is a compellingly

fascinating and commanding figure. Nevertheless, he is

a menace and danger to society, particularly in his

attractiveness to weak and vulnerable women; three of

those women appear in high-relief in the Mozart/Da

Ponte version, and each having her own particular

obsession with him, is aware of his evil, but is ready and

willing to surrender to him.

Don Giovanni boldly confronts his world: a Faust

committing the sin of curiosity, or a Carmen obsessed

with her freedom to love whom she wants.

Subconsciously, he can be viewed as an archetype of

every man or woman’s alter ego, who, in their tension,

desire, and craving for love, faces that eternal conflict

between reason and emotion, the spirit and the flesh, or

the sacred and the profane. Don Giovanni represents

those powerful, uncontrollable irrational forces, and his

ambivalent world confronts him in conflict: he can be

either a blessing or a curse.

Throughout its two-hundred year plus history, Don

Giovanni has been considered “the opera of all operas,”

possibly the most perfect opera ever written. It is a

monumental wonder of musical imagination, a work

containing towering music with unrivalled beauty, and a

plot whose dramatic essence contains timeless themes;

perhaps a most appropriate accolade attributable to this

immortal masterpiece would be “THE opera of the

second millennium.”

During the late eighteenth century, the opera buffa

genre was fast coming into prominence, but contrarily,

the opera seria genre was en route to obsolescence.

Mozart largely modeled Don Giovanni on the style of

The Marriage of Figaro: it is a synthesis of the opera

buffa comic style with the serious styles of opera seria.

Although librettist Da Ponte wanted his scenario to be

entirely comedic, a satire in the old classic tradition,

Mozart perceived an inner depth in the story, and was

Don Giovanni Page 21

determined to inject seriousness into the plot.

The designation dramma in Mozart’s time signified

the grander, heroic world of opera seria, while giocoso

denoted “gaiety” or “frolic.” Don Giovanni was

designated a dramma giocoso, a “humorous drama,” and

therefore represents the compromise between composer

and librettist, the resulting work containing a profound

seriousness melded with riotous comedy and humor.

Mozart himself would at times casually refer to the opera

as an opera buffa.

Don Giovanni is a tragicomedy in which boisterous

laughter becomes fused with serious tears, where

slapstick, farcical comedy, and humor fuse with the

supernatural might of avenging providence. The blending

of these two elements, in many respects, heightens the

poignancy and eeriness of the tragedy.

To heighten the effect of tragicomedy, like Marriage

and the later Così fan tutte, the plot continuously

alternates between the comic and satiric, and then quickly

plunges into the darker shades of genuine tragedy; Donna

Anna is a genuine opera seria personality, a woman of

driving passions who portrays profound grief for her

father’s death, and a relentless obsession for revenge

against Don Giovanni.

Donna Elvira is also essentially an opera seria

character: she is a spurned woman who alternates

between love, compassion, and revenge. Likewise, Don

Ottavio’s noble devotion and outpourings of love are pure

sentiments from the opera seria genre, and nothing could

be more derivative from the opera seria than the forces

of supernatural retribution when the Commendatore

comes to life and leads Don Giovanni to his ultimate

doom and eternal punishment.

But smiles, sublime humor, and the gaiety of opera

buffa are dutifully portrayed in the playful quarrels and

reconciliations of Masetto and Zerlina, the Don’s

thrashing of Masetto, and all of the traditional opera

buffa servant Leporello’s comic relief: his wit and humor

in the Catalogue aria: his charade and exchange of

clothes with his master and its ensuing catastrophe.

Don Giovanni is a man with a romantic compulsion,

a cold and insensitive adventurer living a tension

between desire and fulfillment. The profligate Don

Giovanni is governed by a single motivation: his flaunting

of society and its rules in the pursuit of sexual pleasure.

Leporello ironically tells Donna Elvira about his

Don Giovanni Page 22

master’s compulsions in the Catalogue, a moment of

laughter, yet a moment of tears for the vanquished:

“Women of every rank, fat or thin. Tall for majesty, small

for prettiness, old women for the list’s sake, poor girl,

rich girl, ugly girl, lovely girl so long as she’s a skirt,

you know what happens.”

Giovanni is an escapading antihero, an adventurer

whose charismatic personality captivates and

overwhelms all who encounter him: his victims remain

in awe or shock, yet his demonic engine continues to

grind steadily with a passionate ebullience and a forceful

vitality.

In our times, the classic Don Juan legends have

passed from the realm of drama into Freudian symbolism:

psychiatric jargon speaks repeatedly about the “Don

Juan” complex. The hero fails to recognize his true self

hiding behind his mask: there is a cold heart behind his

masquerade of obsessive sexuality and amorous passion.

Modern psychologists cite that his adventures hide an

unconscious male fantasy, an obsession for blissful

union, or reunion, with his mother. His unconscious

obsessions have driven him into sexual adventures that

are not the outcome of real feelings, but rather, illusory

manic obsessions with sex that are the chronic symptom

of a disease which is incomprehensible to him.

In that context, Don Giovanni is never capable of

experiencing true love, because he has erected a defense

for his fear and yearning that overshadows his narcissistic

selfishness and even selflessness. In effect, he is

defending himself against women, running no harder

after the next woman than he runs away from the last,

especially if she begins to look like a threat to his

defenses.

So behind that facade of the swashbuckling, boudoir-

hopping, serial sexist, lurks a perpetual adolescent

needing instant gratification; or perhaps a latent

homosexual actually hating women; or perhaps an

antihero intent on evil who slays an interfering father

(the Commendatore) and seduces one unsatisfactory

mother-image after another. It has even been suggested

that Don Giovanni himself is some incarnation of a

fertility god, so to attend a Don Giovanni performance

is to participate in the celebration of a ritual.

But in spite of modern psychological interpretations,

Don Giovanni is a classical morality play: good must

conquer evil. Don Giovanni cannot flaunt society’s norms

with his carefree pursuit of sexual pleasure, so in the

end, he must be punished and receive divine retribution;

Don Giovanni Page 23

it becomes the man he murdered, the Commendatore,

who appears to him in his metaphysical apparition, who

ultimately represents the embodiment of divine law and

destiny: the moral voice of righteousness. In the end,

Don Giovanni’s ultimate fate is horrible and gruesome,

yet he must be punished and Mozart’s genius elevates

his demise to an incomparable sublimity.

D

on Giovanni is the central catalyst who evokes all

of the responses and actions from the other

characters; when Don Giovanni acts, everyone else

reacts. He is an almost opaque hero who becomes defined

by those he pursues.

Yet in his picaresque world, we never really know

the inner soul of the hero; there are no Wagnerian-style

introspective moments in the text in which Don Giovanni

reveals the deep inner workings of his soul. Yet, he

instinctively and intuitively knows his surrounding world

and senses the vulnerability of the characters who

confront him: he will exploit all of them; all of them

will be humbled and humiliated; and in the process, each

one will become aware of his own weaknesses and

vulnerabilities.

All of the characters in this drama suffer from their

yearning and craving for love, but Mozart and Da Ponte

shift the “wages of sin” from sinner to the sinned against.

As a result, all of the characters provide a mirror in which

to view the human soul in all of its anxiety and pain.

In their defense, they all find a way to blame Don

Giovanni, and at times, their reaction is to accuse each

other of cruelty. But in truth, it is Don Giovanni who is

cruel; it is Giovanni who is steadfast and resolute in his

heartless and callous pursuits, and in the end, the pursued

will stand dumbfounded in wonder and awe. Mozart

ingeniously weaves these individual personalities for us

in his music, breathes life into them, and when their

heartbeats pound, we sense their feelings, sometimes

comic and sometimes serious, and sometimes both.

In the three female characters in Don Giovanni, the

spectrum of womanhood is rounded and rendered

complete: the great opera seria characters of the

avenging Donna Anna and the sentimental Elvira, and

the crafty but sympathetic opera buffa peasant girl,

Zerlina.

Donna Anna’s character shades the opera with both

Don Giovanni Page 24

darkness and romanticism, and it is Anna’s grief in her

father’s death that is a mainspring of the drama. Mozart

places total humanity in Donna Anna, the daughter of

an aristocratic nobleman, and a woman completely

possessed by passion.

It is never quite clear whether Donna Anna was

indeed seduced and raped, or willingly participated with

Giovanni, or silently invited their liaison. It is a most

dramatic episode when Donna Anna tells Don Ottavio

that she recognizes Don Giovanni, through his voice and

manner, as her father’s murderer, and her assailant from

the night before. To Mozart’s eighteenth century

audience, Don Giovanni had obviously taken his pleasure

for there are noticeable gaps and discrepancies in her

story: her explanation is far too much concerned with

the attack on her honor, and far too little of her

explanation is concerned with the killing of her father.

Don Giovanni is a man of the chase and the kill: he

has no concern for the carcass afterwards. It is speculated

that Donna Anna was indeed seduced, and willingly

welcomed their amorous episode, but like all of his

conquests, when it was over, it was over. So the death of

her father stands as a subterfuge for her more extreme

passions: her revenge against a perfidious lover.

Mozart’s supreme devotee, Ernst Theodor Amadeus

Hoffmann, an early nineteenth-century writer whose

obsession with Mozart and his opera Don Giovanni

compelled him to change his third name to Amadeus,

hypothesized Donna Anna’s character in one of his

fantastic tales, Don Juan (1813), republished as

Phantasiestucke in Callots Manier (1814). Hoffmann

called Donna Anna a “divine woman over whose pure

spirit evil is powerless.”

Hoffmann concluded that Donna Anna was a

profoundly sensuous woman who was secretly aflame

with desire for Don Giovanni; it is her distinct call for

revenge, Or sai chi l’onore, in which he suggests that

Donna Anna had been willingly seduced by Giovanni,

and was deeply in love with him. Hoffmann’s brilliant

fantasy would later receive comic treatment in Shaw’s

Man and Superman, interpreting Don Giovanni as the

incarnation of an evolutionary “life force,” with its hero,

a demonic and satanic force of evil who rises to challenge

God himself.

The unfortunate corollary to Hoffmann’s elevation

of Donna Anna in his fantastic tale is that he makes

Donna Elvira into something of a caricature, a less

voluptuous specimen of womanhood than Donna Anna:

Don Giovanni Page 25

Hoffmann introduces Elvira as the “tall, emaciated

Donna Elvira, bearing visible signs of great, but faded

beauty.” Da Ponte’s libretto specifies only that she be

young, and Baudelaire refers to her as “the chaste and

thin Elvira.”

Donna Elvira was the specific creation of Moliére’s

version of the legend in his Le Festin de Pierre (1665).

Elvira then became a strong minded woman with

complex, multidimensional, and perhaps the most

profound feelings of all the female characters. Mozart’s

musical portrait of Donna Elvira provides a delicate

balance between sympathy and rage for a mocked and

humiliated woman who is constantly tormented and

degraded. Yet, Elvira brings to the fore the paradox of

how quickly love and hate can be triggered: she becomes

obsessed with vengeance, but at the same time, she is

ever doting and willingly available as an easy conquest

for Giovanni.

Donna Elvira represents a magnificent portrait of a

classic spurned woman: she was a former nun who was

seduced by Don Giovanni while she was in a convent,

and the memory of that experience has become her life’s

obsession; she is determined to tear out Don Giovanni’s

heart unless he returns to her.

Donna Elvira is the only woman in the story who

openly expresses true fidelity to Don Giovanni, and in

that sense, she represents the real threat to his defenses,

perhaps the reason he fights her off so cruelly. (Da Ponte

even suggests that Don Giovanni married her since that

was the only way he could control her.)

Elvira pursues Don Giovanni with a passionate

single-mindedness, her love for him not just a merely

passing episode but a decisive passion. In that sense,

Donna Elvira, of all the women in the opera, is the one

character whose entire human essence is closest to that

of Don Giovanni. Like Giovanni, she is constantly in

pursuit of the ideal, craving and yearning for love.

Giovanni kindled a spark in Elvira, and she shares that

same consuming passion that burns in him.

Elvira’s Ah! Fuggi il tradito has a passionate and

fiery fury: they are cries that expose the tormented

misfortune in her soul, but her final outbursts of revenge

and hatred against Giovanni merely again confirm the

proximity of the passions of love and hate. Nevertheless,

she is determined to win back Giovanni’s love, even after

she recognizes the hopelessness of her quest.

Donna Elvira’s misfortune was that for her

Don Giovanni Page 26

apparently first and only love experience became none

other than the licentious Don Giovanni. It was for her,

an euphoric moment, and she wants to devote her whole

being, her life, love, and future to Don Giovanni, the

man she refuses to abandon. Donna Elvira is a tragic,

tormented figure who thirsts for tenderness, and passes

from outrage and indignation to powerless defeat,

despair, and illusion as she realizes that she will only be

able to find solace in her memories.

Don Ottavio is the great comforter and consoler,

Donna Anna’s husband-to-be, a man of admirable

sentiments who is constantly joining his beloved Anna

in sharing her suffering and solemnly offering her solace

by swearing revenge.

In Donna Anna’s recognition recitative, Ottavio says

that he never heard of a cavaliere capable of so black a

crime, and swears by his duty as lover and friend to

vindicate Anna’s honor, always listening open-mouthed

and with suitable sympathy to her commentary.

Ottavio is colorless, docile, yet worthy and well-

meaning: he appears as one of those dog-like followers

who invariably seem to accompany desirable and

voluptuous women. It appears to take him a long time to

reach his conclusion about Don Giovanni’s offenses

which Donna Anna reached through first hand

experience. Somehow, he interprets Giovanni’s guilt

based on the evidence of Giovanni’s unsuccessful

seduction of Zerlina and his beating of Masetto: none of

his conclusions would pass the test of the “smoking gun,”

and he certainly does not want to face the truth that his

Donna Anna had been violated.

Zerlina is ambivalent: she is either an innocent

country girl, or a saucy, wily, and ever-so-omniscient

flirt; Mozart’s music for her is always full of a sense of

guile and trickery.

When Don Giovanni sings his serenade to Zerlina,

“Là ci darem la mano,” Mozart’s music dissolves any

animosity toward Don Giovanni as he magically

characterizes his aristocratic bearing contrasted against

Zerlina’s pastoral shyness. It is a masterly instance of

Giovanni’s insincerity, but Zerlina nevertheless believes

all of his expansive talk about the “honesty painted in

their eyes.” Mozart’s cynical eighteenth century audience

would have certainly laughed at her innocence and

gullibility, but they would also have laughed as they

anticipated the villain’s discomfort.

Don Giovanni Page 27

“Là ci darem la mano” is a wonderfully sensuous

and exquisite musical scene in which both parties seem

to be irresistible to each other, both displaying subtle

explosions of physical attraction and chemistry. Zerlina

vacillates with indecision. She wants to, and doesn’t want

to, but feels herself weakening: their Andiam contains a

sense of sublime excitement and pleasure.

Zerlina later uses her irresistible charm to console

Masetto after his thrashing, and just like Giovanni, she

exploits his exaggeration of his injuries with irresistible

arguments: love will resolve everything. Zerlina’s “Batti,

batti o mio Masetto,” is a light and lovely moment of

supreme opera buffa.

Leporello can be viewed as a direct descendant of

the Commedia dell’arte tradition, the standard satirical

portrayal of the comic servant, and the supreme example

of the opera buffa character portraying mock anxieties:

his rebellious indignation when he complains

sarcastically and bitterly about the conditions of his

employment with his libertine master - irregular meals,

lack of sleep, constant waiting around in wind and rain;

his cynical congratulations to his master on successfully

concluding the seduction of a daughter and the

elimination of a father; his horror at the death of the

Commendatore, an eccesso, or excess that was provoked

and certainly the last thing he or his master ever intended;

his anxious patter combined with genuine pathos as he

begs for pity from Giovanni’s avengers; his compassion

for Elvira when he tries to persuade her – through the

Catalogue – of his master’s unworthiness, that she is

not the first nor the last of his master’s conquests; and,

of course, his pride in describing his master’s preferences

and adventures.

In his moments of righteous indignation, when he

tells his master point blank that he considers him to be

leading a wastrel’s life and he threatens to leave his

service, resolution and loyalty quickly return with

Giovanni’s bonus compensation.

But imitation is the greatest form of flattery, and

when Leporello is among the peasants, he imitates his

master’s habits and mannerisms, and is hopeful that

among so many young women, there might be something

for him too. He relishes his moments as a Don Giovanni

in training, although it is an exaggerated moment; he

obviously enjoys the charade and impersonation of his

master as he woos Donna Elvira: “Son per voi tutta foco”

(“I’m all fire for you.”)

The Leporello character is a magnificent blend of

Don Giovanni Page 28

wit, a fusion of the comic and serious, and quintessential

opera buffa.

The entrance of the three masked characters provides

a magnificent moment for ambivalent meaning, arcane

subtext, and variety in interpretation. As the three masked

characters – Donna Anna, Donna Elvira, and Don Ottavio

– arrive at Don Giovanni’s party, the music and text

explode with the strains of viva la libertà. (Da Ponte

withheld this portion of the opera when he submitted it

to the censors.)

For each character, liberty may have a different

meaning. For Don Giovanni himself, liberty is perhaps

his right to exploit his surrounding world; he certainly

at that moment has accomplished his goal by inducing

everyone to his castle, if only for the opportunity to

seduce Zerlina.

For Leporello, liberty could define his freedom to

emulate the licentious actions of his master. For Zerlina,

liberty could mean a higher social status, something

she disingenuously believes she could achieve by

spending a night with the aristocratic Don Giovanni. For

Masetto, liberty could mean his right to fight for justice

and what is right.

And for those three masked characters, liberty is

their freedom to enter into Don Giovanni’s iniquitous

world and unmask, expose, and punish the horrible

seducer and murderer.

T

he banquet scene of Don Giovanni is a great tour-

de-force of the lyric theater. In a magnificent blend

of the comic and tragic, the Stone Statue of the

Commendatore invades Giovanni’s banquet; panic erupts

as Donna Elvira flees, and Leporello hides under the

table. Don Giovanni confronts the terrifying Statue with

ferocious courage. In this symbolic defining moment,

Don Giovanni stops running away from himself, and is

forced to look inward: he invites the Stone Statue to

dine with him.

When Don Giovanni grasps the Stone Statue,

symbolically, he feels an unmistakable coldness, perhaps

the inhuman coldness lurking within his subconscious.

And symbolically again, he cannot free himself from

the grasp of the Stone Statue, even as flames rise up

around him; nevertheless, Giovanni remains resolute and

will not repent his dissolute life.

Mozart’s music inventiveness, the scoring of this

moment in the chilling and frightening D minor key, the

Don Giovanni Page 29

same tragic sounding key and chords heard in the

Overture and when the Commendatore was mortally

wounded in Act I, provides a brilliant musical portrait

of that defining moment in which an eternal universal

sinner is about to receive divine retribution for his

transgressions.

Don Giovanni is doomed to Hell: he is supposed to

experience those same transforming fires that

mythological heroes and images of our collective

unconscious have passed in order to achieve a

transformation; a transcendence and epiphany, a return

to the world with new insight, understanding, awareness,

and compassion. In its moral sense, Don Giovanni must

repent in order to achieve a new understanding so that

he learns that stone symbolizes coldness and nothingness;

that within the interaction of humanity, there must be

warmth, feeling, true love, and compassion.

But Don Giovanni is resolute and does not

experience a transformation; therefore, his demise

becomes cathartic and one is purged and overcome with

pity. In its most compelling supernatural extreme,

avenging devils drag the unrepentant sinner to eternal

punishment.

Don Giovanni represented archetypal evil: he was

cruel, seductive, coarse, and arrogant. But Don

Giovanni’s appeal is that even though the dissolute

transgressor foresaw his irrevocable damnation, he

certainly was unequivocally courageous and resolute in

his refusal to repent, to become anything other than his

reprobate self. In the end, Don Giovanni’s final

damnation represents justice for all of his sins,

transgressions, and misdeeds. Mozart unhesitatingly

treats those forces of supernatural retribution with great

solemnity and seriousness: Don Giovanni, after all, in

so many senses represents the eternal tragedy of all

humanity.

Nevertheless, Mozart lightened the profound

seriousness of the final tragedy, and removed the sting

from the hero’s grotesque fate and descent into Hell: the

final sextet can be seen as either a vaudeville ending to

the tragedy, or a moralizing emphasis. The remaining

six characters arrive on stage and address the audience,

presumably announcing that with the demise of Don

Giovanni, life has returned to normalcy.

Don Giovanni was the classic sinner, the all-time

rake who challenged authority, challenged society, and

thus challenged God. The survivors tell us that justice

has been served, and society has been purged of his

Don Giovanni Page 30

seductive and destructive power. But Don Giovanni

achieved immortality: he may be gone, but he will never

be forgotten.

I

mitation is the greatest form of flattery. Don Giovanni,

more than any other opera except perhaps Tristan und

Isolde, has caught the imagination of artists, composers,

poets, philosophers, psychologists, men of letters, and

music lovers.

The Mozart-DaPonte Don Giovanni story has left a

legacy of inspired treatments from Byron, Baudelaire,

Mérimée, Pushkin, and Tolstoy. The overworked and

exploited Beethoven, in his Diabelli Variations, sneered

at his publishers with Leporello’s “Notte e giorno faticar”

(“Night and day I am worked to death.”) In the Prologue

to Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann, there is an underlying

suggestion that the whole work is on one level an

exegesis of Mozart’s opera.

Don Ottavio’s aria, “Il mio tesoro” (“My treasure”),

was an early recording sung by John McCormack that

supposedly became the most prominent early phonograph

recording. Beethoven and Chopin wrote variations on

the duet, “Là ci darem la mano”; Liszt includes this

music prominently in his Don Juan fantasy; in the film

version of Dorian Grey, the hero is compelled to hear

“Là ci darem la mano” as he embarks on his first

seduction; and in James Joyce’s Ulysses, the music

haunts the cuckolded Leopold Bloom after he hears his

wife singing it to her lover as they advance toward sexual

conclusion.

Mozart’s Don Giovanni was a spectacular triumph

in Prague, receiving more performances than The

Marriage of Figaro in 1786, and becoming, after Die

Entführung aus dem Serail, the Mozart opera most

performed in his lifetime. Since its premiere, nearly every

opera singer of note has been associated with one of the

main roles in Don Giovanni.

Rossini, upon seeing the Don Giovanni score for

the first time, fell to his knees, kissed the music, and

exclaimed of Mozart: “He was God himself.” Goethe

claimed that only Mozart, the man who had written Don

Giovanni, was capable of setting his masterpiece, Faust,

to music. Gounod, a composer who did set Faust to

music, said of Don Giovanni: “It has been a revelation

all my life. For me it is a kind of incarnation of dramatic

and musical perfection.” Wagner would ask: “Is it

Don Giovanni Page 31

possible to find anything more perfect than every piece

in Don Giovanni: Where else has music individualized

and characterized so surely?” Tchaikovsky famously

commented “Through that work I have come to know

what music is”; Bruno Walter confessed, “I discovered

beneath the playfulness a dramatist’s inexorable

seriousness and wealth of characterization. I recognized

in Mozart the Shakespeare of opera.” Shaw thought the

fine workmanship he found in Don Giovanni “the most

important part of my education.” Kierkegaard exclaimed:

“Immortal Mozart, you to whom I owe it that I have not

gone through life without being profoundly moved.”

E.T.A. Hoffmann called Don Giovanni the “opera of all

operas.”- that title unchallenged for two centuries..

At the beginning of Act II, Don Giovanni defends

his life of exploitation and seduction to his servant,

Leporello: “Don’t you know that they are more necessary

to me than the bread I eat, the very air I breathe.”

The essence of the entire opera concerns the tragedy

of sexual obsession. Although he is evil, Don Giovanni

is resolute in his aims and exploitations: he cannot resist

indulgence, deception, or the sheer joy of deception for

its own sake. For Giovanni, the thrill of the chase was

the excitement of life itself. Like his fellow libertine,

the Duke in Rigoletto, whose motto was “Questa o

quella” (“This woman or that woman,” Giovanni’s motto

was “quest’ e quella” (“This woman AND that woman.”)

Don Giovanni provides that great combination of

poignant sadness and emotional turmoil, together with

moments of lusty charm, comedy, gaiety, excitement, and

laughter.

The essential tragedy in this story of the great

seducer, owner of the famous catalog, is that he goes to

eternal damnation for no more vicious or inexcusable a

crime than the killing of an old man whom he tried his

hardest to dissuade from fighting, and, in fact, killed in

self-defense.

Nevertheless, with all of the story’s allusions and

moral fanfare, it does seem that another tragedy can be

interpreted within the Mozart/Da Ponte Don Giovanni

story: he was a recurrent failure in all of his seductions.

Thus we experience the intrigue and the excitement

of an opera that for two centuries has been considered

an extraordinary work of genius, and possibly the most

perfect opera ever written: “the opera of all operas.”

Don Giovanni Page 32

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

libretto Don Giovanni di W A Mozart

Da Ponte, Lorenzo Don Giovanni (Mozart, libretto opera)

Guareschi Giovanni Mały światek Don Camillo

Giovanni Guareschi [Don Camillo 01] The Little World of Don Camillo (pdf)

Sanczo Pansa.Don Kichote charakterystyka, filologia polska, Staropolska

Don Kichote, Streszczenia

Don Kichote Streszczenie

Morandi Don't look?ck

Don Kichot

don kichote konspekt lecji 5, szkolne, Język polski metodyka, To lubię, To lubię - scenariusze

Elwell, Don The Ganymeade Protocol pdf WP

I don t care whether it s HPV or ABC — kopia

Nowy folder

więcej podobnych podstron