“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and

Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania,

1941–1944

Björn M. Felder

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen

During World War II the Nazis sponsored the practice of

“euthanasia” (the

killing of medical patients) outside Germany as well as within the Reich.

While responsibility for the starvation of psychiatric patients and other

medical abuses in Lithuania resides primarily with the Reichskommissariat

Ostland

—the German civil administration in the Baltics—the 1,200 to 1,500

patients who died from malnutrition in Lithuania between 1941 and 1944

were simultaneously victims of Lithuanian health of

ficials, physicians, and

others. The author

’s research demonstrates that many Lithuanian professio-

nals not only condoned and helped to administer Nazi

“euthanasia,” but

that they also rendered their own signi

ficant contribution by conducting

medical experiments on already starving patients.

After suffering a seizure in public, 41-year-old epileptic Feliksas Garicˇas was taken by

the police to the Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital at 5 Vasaros Street on February 24,

1942. By October 14 Garic

ˇas was dead.

1

His patient

file says he died because of a

“weak heart.” Indeed, Garicˇas was one of 384 “mentally ill” persons in that institution

who did not survive 1942. Typically, there were between 250 and 350 institutionalized

patients at the hospital. Available records show that from July 1941 to April 1944, 695

patients died at that facility alone; basing themselves on materials available immedi-

ately after the war, Soviet of

ficials seem to have counted 875 deaths. Altogether,

I have been able to document at least 1,018 cases of psychiatric patients who fell

victim to Nazi euthanasia in Lithuania;

2

if we include all Lithuanian psychiatric facili-

ties, there is reason to believe that as many as 1,200 to 1,500 may have died.

In Lithuania, the Nazis generally did not kill institutionalized patients by shoot-

ing or gassing (some appear to have been shot): the majority were slowly starved by

Lithuanian administrators and medical personnel. As in Germany, in Lithuania lower-

level and local actors played an important role.

Feliksas Garic

ˇas wasted away, going from sixty-eight to fifty-two kilograms.

3

But

this wasn

’t simply starvation: Garicˇas was administered electroshock therapy—

invented in 1937 and during the war still widely regarded as the latest word in psychi-

atric therapy. As of August 1942, Garic

ˇas had received electroconvulsive shocks every

doi:10.1093/hgs/dct025

Holocaust and Genocide Studies 27, no. 2 (Fall 2013): 242

–275

242

third day and already had lost eleven kilograms. After that, doctors decreased the

frequency of these

“treatments,” the last one being documented on September 25,

1942

—three weeks before Garicˇas’s death. It might appear strange that a patient so

weakened by malnutrition received a therapy that causes devastating convulsions;

even then it was quite unusual to treat epilepsy with electroshocks.

4

Yet Garic

ˇas was

no rare exception: nearly every patient at the Vilnius psychiatric facility was so treated.

Many died as soon as the day after their last session, or even while still undergoing

treatment. Moreover, patients received other forms of shock therapy, including those

employing drugs such as insulin or cardiazol ( pentylenetetrazol). Pyrotherapy (arti

fi-

cially inducing fever) was also employed; this entailed vaccinating patients with

malaria or other pathogens. More bizarre, physicians at the Vilnius facility also used

strychnine and typhus bacteria

—quite unorthodox in the history of shock- and even

pyrotherapy. All this suggests that psychiatrists at Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital,

then under the directorship of Antanas Smalstys, tested new forms of therapy on

human experimental subjects. Perhaps knowing their patients were doomed anyway

made it easier for these physicians to rationalize their efforts.

Heretofore, the story of Nazi-sponsored killing of

“mental” patients in Lithuania

from 1941 to 1944 has received scant attention. My work analyzes Nazi strategies,

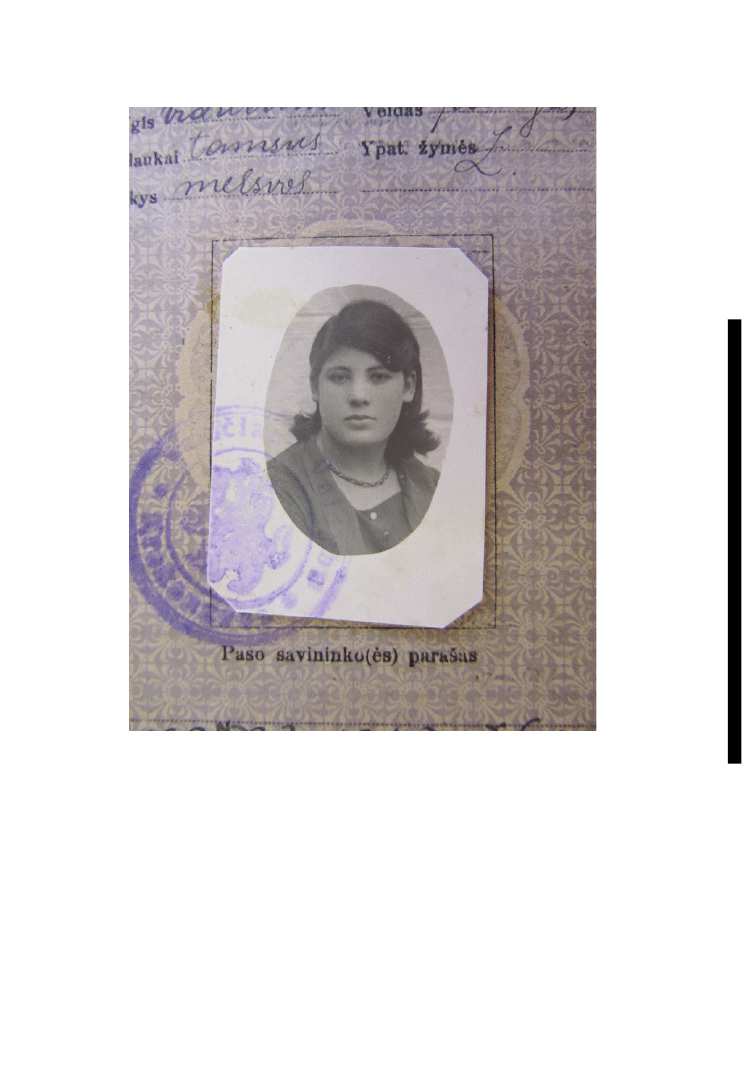

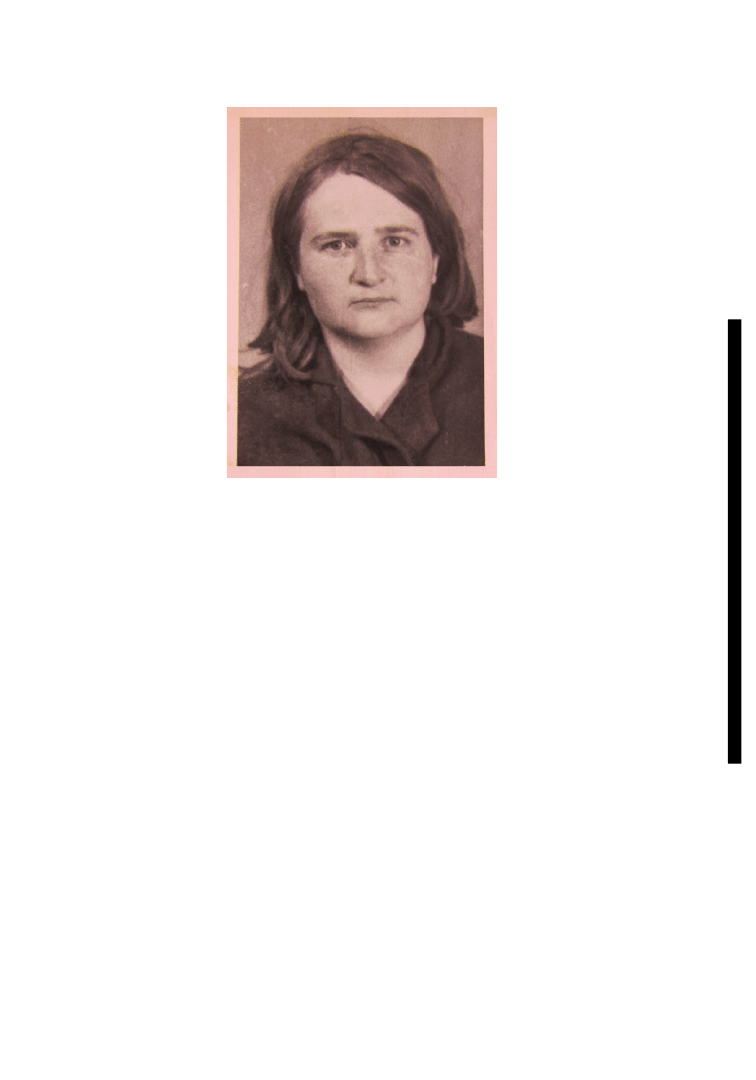

Jadvyga Mikelionyte

˙ , 25-year old Lithuanian epileptic admitted to Vilnius Psychiatric Hospital December

1940. Given

“sleep therapy” with morphine and luminal. Housed for some time in colony. October 22,

1942 death ascribed to

“weak heart.” Courtesy Lietuvos Centrinis Valstybe¯s Archyvas.

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

243

actors, and decision-making structures, and explores the role of local actors such as

physicians and health of

ficials, in this deadly process. The following looks closely at

human experiments conducted at the Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital and contextu-

alizes events within their regional and historical framework.

The European Dimension of Nazi

“Euthanasia”

A large number of scholarly works have examined Nazi

“euthanasia”—the so-called

“Operation T4”—under which patients of German psychiatric facilities fell victim to a

centrally organized killing program starting in autumn 1939.

5

After news of this secret

killing program leaked, there were some public protests, especially by prominent

church leaders. Hitler then

“officially” stopped the operation on August 24, 1941—

although only the centralized killing operation actually ceased, the policy being

quietly decentralized to less visible institutions. In fact, the euthanasia killings contin-

ued all the way to the end of the war. Altogether, Operation T4 enabled the killing by

starvation, injection, or gassing of about 100,000 psychiatric patients in Germany.

6

The connection of euthanasia to the Holocaust is quite obvious. Besides chro-

nology

—the Holocaust began with the attack on the Soviet Union, just two months

before Operation T4 was publicly halted

—there was also a transfer of techniques and

personnel to the extermination camps in occupied Poland.

7

And of course the killing

of both the

“mentally ill” and the Jews was rationalized by Nazi “racial science” and

the ideology of

“racial hygiene”: both the mentally ill (as well as people suffering from

other disabilities) and the Jews were seen as

“inferior” and thus as a threat to the Nazi

racial vision. This was bio-politics in Foucault’s sense at its worst: following the radical

interpretation of eugenic ideas by purging society of the

“genetically inferior” in order

to engineer an improved

“master race.”

8

Despite this, the killing of the mentally ill has remained in the shadow of

popular and scholarly perceptions of the Holocaust. It remains even less well known

that Germany exported the practice of killing psychiatric patients to the countries it

occupied or dominated. Shortly after the occupation of Poland, the Einsatzgruppen of

the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) started liquidating psychiatric hospitals by

killing their patients.

9

The Einsatzgruppen carried out mass shootings of psychiatric

patients in the occupied territories of Soviet Belorussia and Ukraine. In Belorussia the

SS exploited psychiatric patients for experiments testing the lethality of poisons, explo-

sive devices, and gas wagons.

10

The northern Russian cities of Luga, Gatchina, and

other Leningrad suburbs witnessed the killing of psychiatric patients in the summers

of 1941 and 1942.

11

In Latvia similar events occurred. By the end of 1942, approximately 2,500 psy-

chiatric patients had been killed by Einsatzgruppe A and Latvian auxiliary units of the

German security police, the so called

“Arajs-Kommando.”

12

The murders started in

the town of Aglona on August 22, 1941, when Karl Jäger

’s Einsatzkommando 3 (sub-

ordinate to Einsatzgruppe A) shot 484 psychiatric patients and sixty orphans from

244

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Dünaburg (Daugavpils).

13

In the next round, Jewish patients were selected from psy-

chiatric hospitals and executed in autumn 1941

—a development probably more

appropriately associated with the general killing of Latvia

’s Jews at that time.

14

The

majority of Latvia

’s mentally ill were shot in spring and autumn 1942, when their

facilities were transformed into military hospitals. This occurred, for example, at the

Sarkankalns Psychiatric Hospital in Riga

—Latvia’s largest—which became a hospital

for the Waffen-SS.

15

Throughout the Baltics, the Germans killed primarily by shooting

—the fate that

most of the Jews, Communists, and other target groups suffered. In Estonia the men-

tally ill of Jewish origin shared this fate. Doora Kroon

“was taken away by the police”

from the Psychiatric Clinic of the University of Tartu on September 3, 1941, which

suggests that this also happened to other Jewish psychiatric patients.

16

Surprisingly,

though, in Estonia there were no mass shootings of the mentally ill until near the end

of the war.

17

While we do not know the exact number of surviving Estonian psychiatric

patients, the majority who perished fell victim to malnutrition. There is evidence that

the starvation of the mentally ill in Estonia was based on a systematic strategy applied

by the German civil administration, the Reichskommissariat Ostland.

18

In the vast literature on the Holocaust in Lithuania works on the killing of

Roma, Communists, and Soviet prisoners of war are numerous. But Nazi-sponsored

and Nazi-inspired euthanasia have been mentioned seldom and researched even less

frequently.

19

Soviet-period scholarship on psychiatry during the Nazi occupation

mentions the subject, but neither of the two dissertations devoted entirely to it was

published.

20

After the war, Dr. Balys Matulionis, wartime head of the Lithuanian

administration

’s health department (in Kaunas, de facto capital under the German

occupation) under the

“Generalrat,” or Council, of the Interior, published several

apologetic articles on the issue.

21

Matulionis claimed that he personally prevented the

killing of patients in 1942. The only recently published article on Nazi

“euthanasia” in

Lithuania, written by psychiatrists Aurimas Andriu

šis and Algirdas Dembinskas,

politely follows Matulionis, admitting that killings by starvation may have occurred but

offering no numbers.

22

My research allows us to correct misunderstandings of

Matulionis, in particular assumptions in

fluencing the work of Andriušis and

Dembinskas; this not only affords us a new picture of Nazi euthanasia in Lithuania,

but speci

fies the role of Lithuanians in that crime.

The Debate over Eugenics and Euthanasia in Prewar Lithuania

To evaluate the reaction of Lithuanian actors

—primarily health officials and physi-

cians

—to Nazi euthanasia, it is important to survey earlier public and professional dis-

course. The place of euthanasia in the debate over the

“inferiority” of racially and

genetically

“defective” humans emerged in the late nineteenth century in the context

of a broader discussion of

“degeneration.”

23

Euthanasia was certainly the most radical

means of implementing eugenics, an ideology advocated as a

“scientific” means for

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

245

“improving” the human race by eliminating defective or “deviant” individuals such as

the mentally ill or those who suffered from allegedly hereditary diseases. Even liberal

eugenicists argued for the segregation of the

“inferior” from mainstream society, or

for preventing them from reproducing by institutionalizing them, banning their mar-

riage, or even sterilizing them. Especially after the First World War eugenics came to

be seen as a means by which scientists and government of

ficials—now cast as social

engineers

—could maximize the health of the “national body.” Such a bio-politics

jibed easily with the idea of

“purifying” and homogenizing “the nation” via ethno-

nationalistic means.

24

Lithuanian elites took part in this discourse. As of the late 1930s and early

1940s, many of them had been educated at universities in St. Petersburg, Tartu,

Western Europe, or the U.S., where they certainly would have become familiar with

eugenics. In St. Petersburg and Tartu, eugenics, and in particular German notions of

“racial hygiene,” had been discussed widely before the First World War.

25

In 1926 the

young psychiatrist Juozas Bla

žys, director of the Taurage (later Kalvarijas) Psychiatric

Hospital, advocated government-mandated sterilization and abortion.

26

Later, as a

professor of psychiatry at the University of Kaunas, Bla

žys lobbied for eugenic legisla-

tion until his premature death in 1939. He was convinced that there might be approxi-

mately 15,000

“mental defectives” in Lithuania, of whom 300 ought to be sterilized

every year.

27

Bla

žys was far from the exception. A large group of eugenicists among

Lithuanian bio-medical professionals were calling for eugenic sterilizations.

28

The

National Congress of Lithuanian Physicians urged eugenics legislation in 1937.

Considering the breadth of the discussion at the academic level, one is tempted to

conclude that the majority of the bio-medical elite supported one or another form of

“negative” eugenics, and in particular the German-Scandinavian-American-British

approach of imposing abortions and sterilizations. Vocal objections were few.

Criticism came primarily from devoted Catholics.

29

Still, Bla

žys, like many other

European eugenicists, questioned euthanasia as a method.

30

But in contrast to other

Catholic countries such as Italy, where Catholicism did in

fluence, or even restrain,

eugenicists, in Lithuania and Poland the majority of the bio-medical elite resisted

Catholic pro-natalist strictures.

31

Eugenic perspectives permeated

“bio-politics.” In the 1930s a form of ethno-

nationalism based on

“biological” definitions of “The Nation” spread throughout and

even beyond Europe.

“Blood” and “race” appeared frequently in public statements

and government documents of Lithuania

’s Smetona regime.

32

Facing a problematic

relationship with the Catholic Church, however, Smetona hesitated to give in entirely

to the medical elites. The regime refused to implement eugenics programs recom-

mended by the academy. But this was only a half-hearted rejection, as Smetona

approved a new medical law that tolerated eugenic abortion under the rubric of

“medical indication” in 1935. In medical periodicals regime publicists did not distance

246

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

the government even from radical means such as sterilization, and they attacked the

Catholic Church for its anti-eugenics agenda, which would

“jeopardize the Lithuanian

nation.

”

33

At least one private

“eugenics counseling bureau” was in fact opened in

Kaunas in 1934.

34

In any case, when the Nazis later conquered Lithuania they were

not entering a space free of eugenic patterns of thought or of widespread belief in the

inferiority

—and thus dispensability—of the mentally ill and the disabled. The case of

Lithuania illustrates how people of this mindset reacted when the radical and

inhuman policy of Nazi racial hygiene opened up new opportunities.

The German Administration and the Organization of Euthanasia

through Hunger

The German occupation authorities included two separate hierarchies: the civil adminis-

tration of the Reichskommissariat Ostland; and the forces that the RSHA formed,

namely the Einsatzgruppen (Special Tasks Groups) with their subordinate

Einsatzkommandos, and the Sicherheitsdienst (Security Of

fice) and Sicherheitspolizei.

The Lithuanian government that constituted itself during the

first days of the occupa-

tion was replaced by the Germans in August 1941 with the Generalrat, not a govern-

ment per se, but rather a

“self-administration” for the implementation of German policy

by locals.

35

Because of the

“polycratic” character of the Nazi system—“totalitarian,” but

with competing loci of authority

—individuals could sometimes play significant roles fur-

thering or resisting speci

fic policies, since agencies often behaved as rivals rather than

cooperating. Even within speci

fic agencies personal rivalries, and often feuds, formed

the context of much decision-making.

This phenomenon was especially marked within the Reichskommissariat

Ostland. Generalkommissar of Lithuania Theodor Adrian von Renteln (in Kaunas),

answered to Reichskommissar Ostland Hinrich Lohse (in Riga), who was in turn

responsible to Alfred Rosenberg, Reichsminister for the Occupied Eastern

Territories. The main problem for the Ostland administration was that it had little

independent executive power. The Holocaust was carried out in the Baltic states pri-

marily by the organs of the RSHA. Between July and October 1941, the greater part

of rural Baltic Jewry was killed. Only in the larger cities did small pockets survive,

rounded up into ghettos for slave labor. By the end of 1941, almost all Baltic Jews had

been annihilated as victims of the

“first wave” of the Holocaust, as Raul Hilberg

termed the killings by shooting in front of open pits, long before the Wannsee

Conference and the gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau.

36

Civil servants in the

Ostland administration eagerly, but unsuccessfully, sought to gain control over this

process.

In the killing of the mentally ill, however, the situation was different. In princi-

ple, civil servants had more to offer here, as the health sector lay within their

field of

activity. Even so, in many places the killing of the mentally ill in fact was initiated and

conducted by the Einsatzgruppen, for instance in Latvia, where the

first victims—in

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

247

Daugavpils

—were executed while the Ostland administration was still being formed.

It is not clear whether there was any

“Führerbefehl” (supreme order from the

Führer) to exterminate the mentally ill in all the

“Eastern territories,” but it is clear

that the Einsatzgruppen soon began doing so in occupied Eastern Poland and contin-

ued in the occupied Soviet territories.

In Latvia, the killing of the mentally ill was organized in December 1941 and

January 1942 by bureaucrats under Generalkommissar Otto-Heinrich Drechsler. A

commission consisting of Dr. Henry Marnitz, head of the German administration

’s

Department for Health and National Welfare and a physician himself, other of

ficials

of the department, and representatives of the Sicherheitspolizei decided which

psychiatric patients to kill

—as Marnitz reported to Drechsler in early 1943; the

civilians contributed, but the main tasks of planning, selecting, and killing remained

to the security police.

37

In early 1942, Latvian hospital personnel were required to

fill

out forms concerning patients

’ diagnoses, duration of stay, and other information.

38

Still, Marnitz made it clear that both the initiative and

final decisions lay with the

Sicherheitspolizei. Thus, in December 1942, Dr. Rudolf Lange, Kommandant der

Sicherheitspolizei for Latvia, ordered the killing of the patients in the department for

psychiatric diseases of the Libau Hospital and in Riga

’s Aleksandra Augstums

Psychiatric Hospital. In neither case did his of

ficials solicit cooperation from the civil

administration or even inform them. Marnitz was in fact outraged, though more about

not being informed than about the killings themselves.

39

It is worth noting that the

relationship between Marnitz and Lange had soured earlier.

In Lithuania, too, Einsatzkommando 3 murdered many psychiatric patients

during the early,

“wild” phase of the killings. Karl Jäger had 109 Jewish patients from

the Kalvarija Psychiatric Hospital shot on September 1, 1941.

40

The event thus took

place simultaneously with the general killing of Jews in Latvia and Lithuania. But

Jäger seems to have made a special effort to kill the mentally ill. He was responsible

for the liquidation of the psychiatric hospital in Daugavpils in August 1941, and later

had psychiatric patients killed in the town of Mogutovo, near the Russian city of Luga

(during the wild killings phase, actions often were not con

fined within national

borders). Actually a weak personality, Jäger projected the image of a perfect

SS-officer by carrying out actions before being ordered. In justifying his initiative in

killing the mentally ill, Jäger cited the Wehrmacht

’s need for hospital space, and the

danger that the mentally ill, some of them allegedly armed by local Communists,

posed to public order.

41

The second argument at least is clearly nonsense. One has

the impression that Jäger killed simply because he was a convinced National Socialist:

to Nazis, the mentally ill not only posed a danger to the future of the Aryan

Volksgemeinschaft (people

’s community) but constituted an economic burden as

“unproductive eaters.” Some German physicians had been allowing patients to starve

since early in the Nazi regime, and killing them outright became part of policy in

1939.

42

Another target was Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital, where on February 9

248

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

and 10, 1942, more than twenty patients were

“released” at seven o’clock in the

morning.

43

Andriu

šis wrote about such killings.

44

It seems, however, that at this time

most of the victims were Russians, Poles, and other non-Lithuanians.

Despite the shootings, the majority of the 1,200 to 1,500 psychiatric patients

who died in Lithuania between July 1941 and April 1944

—in my estimate, and not

including Jews

—starved to death. Food was a general problem, and the German civil

administration controlled rationing. Lithuanian of

ficials lodged formal protests (as did

their Latvian counterparts) against the meager norms and the differentials between

those for Germans and those for locals. They argued that children, pregnant women,

and the ill might not be able to survive.

45

In a communication to Generalkommissar

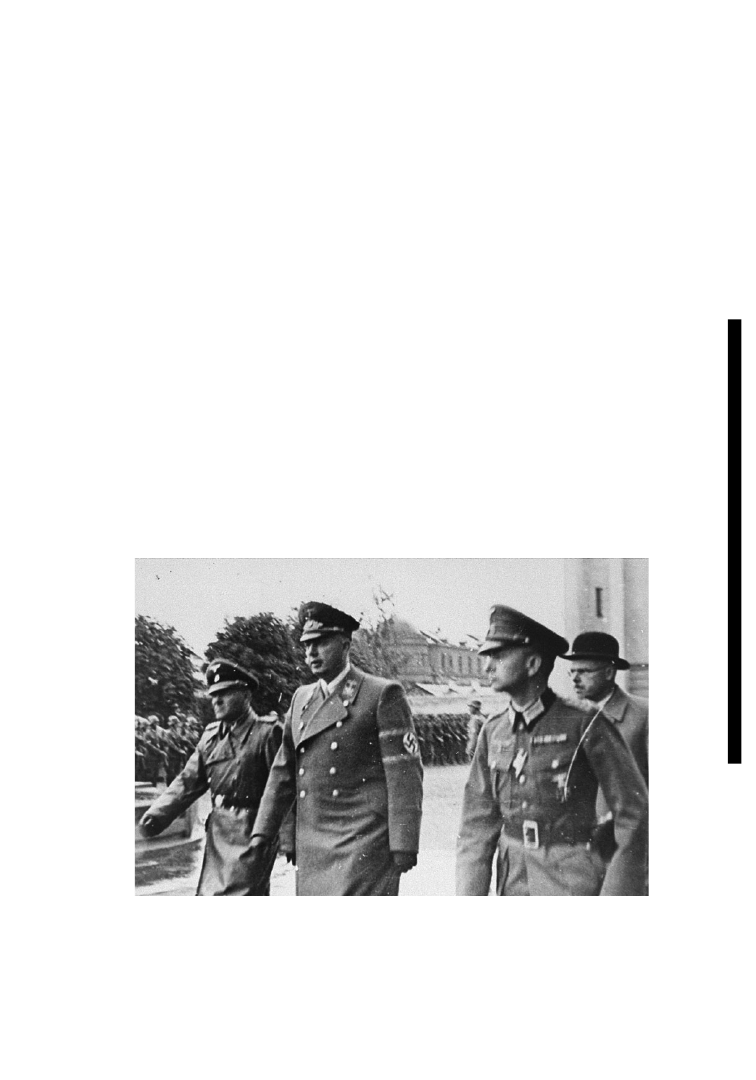

Left to right: Otto Heinrich Drechsler, Generalkommissar Lettland; SA-Obergruppenführer Hinrich Lohse,

Reichskommissar Ostland; Alfred Rosenberg, Reichsminister für die besetzten Ostgebiete; and

Walter-Eberhard von Medem, Gebietskommissar Mitau (Latvian Jelgava). Dobele (Gm. Doblen), Latvia,

1942. Wikimedia Commons, courtesy of the Bundesarchiv.

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

249

von Renteln, Matulionis stressed that the situation was severe for hospital patients,

though he wisely left out any mention of psychiatric patients.

46

In 1942 ordinary hos-

pital patients received a food ration worth 3.5 Reichsmarks per day, psychiatric

patients less than half of that: 1.5 Reichsmarks.

47

Without the help of relatives, the

latter were doomed.

The German administration was fully cognizant of this situation. As early as

August 1941 they had requested information on the numbers of psychiatric patients in

Lithuania,

48

and in August 1942 von Renteln made it clear to Matulionis that there

would be no additional food for them.

49

By all appearances, for von Renteln, starving

the mentally ill was more than simply a

“pragmatic” solution to wartime food scarcity;

he acted as if it were his National Socialist duty to kill them. Such

“genetic cleansing”

of the Baltics was in the end just another step in the planned process of colonizing

the region for Germanic settlers under

“Generalplan Ost.”

50

The same conviction pre-

dominated among German civil servants in the Ostland administration. Walter-

Eberhard Freiherr von Medem, Gebietskommissar (district commissioner) of Mitau

(Jelgava), Latvia, was committed to the principle. He apparently tried to persuade

Latvian physicians to approve the killing of the patients at the psychiatric hospital in

Jelgava; he failed to gain the assent of the locals, so the Germans simply shot the

patients themselves in January 1942.

51

Marnitz never questioned the killing of the

mentally ill.

Systematic starvation of the mentally ill took place in Estonia as in Lithuania.

In the four Estonian psychiatric facilities

—the Seewald Psychiatric Hospital in Reval

(Tallinn), the Psychiatric Clinic of the University of Tartu, the Jämejala Psychiatric

Hospital near Viljandi, and the Pilguse Hospital on the island of Ösel (Saaremaa)

—

food allotments were reduced in late summer 1941 to less than 1,000 calories per day.

The Estonian administration

’s budget for 1943 assigned a mere 0.45 RM per day to

psychiatric patients,

52

resulting in a high mortality rate at all four institutions; the

same administration did approve 3,015 RM for the burial of inmates of psychiatric

facilities in 1943 (the amount for other kinds of clinics, orphanages, and other places,

was less than a thousand).

53

In Dorpat (Tartu) most of the chronic patients had died

by 1945: only nineteen survived out of a 1939 population of 110 (the number of

patients was actually much higher, as others were brought in throughout the war; we

do not know how many were actually released). According to postwar Soviet publica-

tions, the number of patients in Tallinn dropped from 1,065 in 1942 to 435 in 1944.

54

The Ostland administration

’s drastic reduction of food rations for psychiatric patients

was intended to cause the death, away from public view, of most; Ostland itself did not

have the authority to order the patients shot. (In neighboring northern Russia, eutha-

nasia killings were carried out through hunger, lethal injection, and shootings; the

main actor was the Sicherheitspolizei, but killings there also may have involved the

Wehrmacht.)

250

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Killing the Mentally Ill in Lithuania

Jewish psychiatric patients in Lithuania were killed right away, but on genocidal

grounds having nothing to do with euthanasia. In addition to the aforementioned 109

Jewish patients of the Kalvarijas Psychiatric Hospital killed on September 1, 1941,

patients in the unit for mental diseases of the Jewish Hospital in Vilnius were shot in

October 1941 by a squad under the command of SS-Obersturmführer Joachim

Hamann.

55

Other psychiatric facilities delivered their Jewish patients to the German

authorities no later than the beginning of October. The patient register of Vilnius

State Psychiatric Hospital documents the

“release” between September and

mid-October 1941 of sixty-one Jews to the ghetto.

56

If one considers the harsh living

conditions there, one imagines most did not live long. Any who survived were likely

among the

first victims of shootings by the German security police. After the war,

Soviet state security assumed that those Jewish patients had been shot.

57

On August 15, 1941, the director of the Clinic for Neurological and Mental

Diseases at the University of Kaunas, Dr. Viktoras Vaic

ˇiuˉnas, reported to the

Lithuanian health department on the mentally ill in Lithuania; this report obviously

also was intended for the occupiers, as it was written in German. Vaic

ˇiuˉnas assumed

that there might be 6,000 mentally ill and 15,000

“feeble-minded” in Lithuania;

approximately 1,240 of the mentally ill, not including 100

“chronically feeble-minded”

were institutionalized

—a total of 1,340 individuals.

58

Vaic

ˇiuˉnas listed eight institutions

providing beds for permanently institutionalized patients: the Kalvarijas State

Psychiatric Hospital (500); the Clinic for Neurology and Internal Diseases in Vilnius

(100); Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital (300); the Savic

ˇio Hospital in Vilnius (100);

the psychiatric

“colony” (hereafter asylum) at Kaire˙nai (100); the psychiatric asylums

(collectively) of Ve

˙kšniai, Valkininkai, and Ve˙drai (100); the Home for Mentally

Defective Children in Kaunas-Vilijampole˙ (100); and the Clinic for Neurological and

Psychiatric Diseases at the University of Kaunas (40).

The fact that the number of institutionalized patients

fluctuated complicates any

calculation of the number of victims. Patients were released and admitted, while

others died. One cannot simply subtract the number for one month from that for the

previous to determine the number of dead. We need full and reliable numbers.

Unfortunately today we have information for only four of the eight institutions, and

even that is fragmentary.

The Kalvarijas State Psychiatric Hospital, which was founded during the First

World War and served as the main clinic for the mentally ill during the interwar

period, had about 535 institutionalized patients in January 1941; in June

—still under

the Soviet occupation

—only 217 remained; in August, now under the Germans, there

were 189, and in October, again 189. By December the number had dropped to 86,

59

but in January 1942 Matulionis reported to von Renteln that the number of patients in

the Kalvarijas hospital was 215.

60

In April 1942 the hospital had 251.

61

In 1943 and

1944, under the direction of Dr. Viktoras Tekorius, the number shrank to around

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

251

100,

62

and by the end of the war in November 1944, only 49 patients remained.

63

Interestingly, we have a report that during the autumn of 1942 the clinic was comman-

deered as a hospital for prisoners of war (Kriegsgefangenenlazarett) under the

Wehrmacht, suggesting that few mental patients remained.

64

The of

ficial number of

dead for 1942 was 160. For the period from January 1943 to March 1944, we can

con

firm 69 dead. Altogether, there were at least 229 victims of Nazi “euthanasia” at

Ita-Feiga Dembaite

˙ (b. 1911), Jewish schizophrenic admitted to Vilnius Psychiatric Hospital January 1941.

Underwent insulin therapy starting May 1941 and then electro-shock treatment.

“Released” to ghetto

October 8, 1941. Courtesy Lietuvos Centrinis Valstybe¯s Archyvas.

252

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

the Kalvarijas Psychiatric Hospital, but we do not have any numbers for 1941, as only

postwar patient registers and

files seem to have survived.

The Clinic for Neurology and Psychiatric Disorders in Vilnius, under the direc-

tion of Dr. Jonas Kairiu

ˉkštis, included non-psychiatric as well as psychiatric patients.

Judging by its rations, it appears to have been categorized as a general hospital.

Moreover, the death rate there was lower than in other psychiatric facilities. The

number of institutionalized patients averaged about eighty. From November 1941 to

May 1944, seventy-one registered deaths occurred.

65

There also were deaths not

necessarily caused by malnutrition, but, for instance, by cancer or meningitis; it is

dif

ficult therefore to judge the extent to which “euthanasia” contributed to the overall

death rate.

The situation at the Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital is clearer. In 1941 the

number of institutionalized patients dropped from 420 in May to 388 in November.

In the following years it

fluctuated between 250 and 350, with lows of 202 in

December 1943 and 235 in May 1944.

66

For the summer and early autumn of 1941

only fragmentary data survived, indicating that 73 patients died. Another record indi-

cates 89 deaths for the period November and December 1941. In 1942 the deaths of

388 patients were reported, yielding a death rate of nearly 100 percent, while in 1943

an additional 120 deaths were reported, and 27 more in the

first three months of

1944.

67

These

figures result in an incomplete number of 695 dead in less than three

years; after the war, Soviet authorities tabulated approximately 875 dead, a plausible

figure under the circumstances.

68

We also have information on the Clinic for Neurological and Psychiatric

Diseases of the Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas for 1942, according to which

the hospital provided beds for about 50 institutionalized patients and treated a total of

415 patients, 188 of them for mental illnesses. The number of institutionalized

patients

fluctuated between 45 and 70. The hospital counted 23 dead in 1942, half of

them diagnosed as mentally ill; the overall death rate for institutionalized patients was

about 50 percent.

69

Surviving documents for the four institutions (the hospital in Kalvarija, the

clinic in Vilnius, the hospital in Vilnius, and the clinic in Kaunas) leave us with the

incomplete number of 1,018 dead. We have no information pertaining to the other

four institutions. Such a large toll clearly suggests killing by hunger. In fact, the

figure

is higher than the total number of mental patients who died at all institutions in

Lithuania between 1920 and 1939 (and thus without the two in Vilnius, which then

belonged to Poland).

The fate of the psychiatric asylums, where less severe cases were located, reveals

another window onto the issues. The asylums were connected to both the Kalvarijas

and Vilnius psychiatric hospitals. Care here allowed more freedom of movement, and

patients performed agricultural work

—some even living with local families and

farmers, who were paid for boarding them. A similar asylum in Latvia was dissolved in

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

253

December 1941; some of its patients were killed by the security police, the rest trans-

ferred to other psychiatric hospitals.

70

Unfortunately, the surviving information on the

Lithuanian asylums is quite contradictory. Vaic

ˇiuˉnas put the number of residents at

200 in 1941. By contrast, in February 1942 Vilnius Psychiatric Hospital reported to

the health department a

figure of 315 patients at its asylums in Valkininkai and

Ru

ˉdiške˙s. In June 1942, Smalstys reported that 250 patients remained in the asylums

attached to Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital.

71

There is no information on the

asylums in Kaire

˙nai that were attached to Kalvarija. An article by Dr. Vaicˇiuˉnas on

mental health care in Lithuania in 1943 fails to mention the asylums at all. At least

some of the asylum patients were transferred to the Vilnius State Psychiatric

Hospital.

72

It seems clear that the asylums were drastically reduced after autumn

1941, and it seems just as obvious that asylum patients were sent to Vilnius to die.

Most of them passed away within months of arrival. About 194 came to Vilnius in

autumn 1941 and winter 1941/1942

—in any case that number has been documented,

though there may have been more. By the summer of 1942, 180 were dead, with only

a few surviving into 1943. Fourteen had been released in September and October

1941, seven of them Jews transferred to the ghetto.

73

The in

flow to Vilnius Psychiatric

Hospital helps clarify why the high death rate never fully emptied the clinic. It seems

that by the end of the war all psychiatric asylums had been emptied, with the majority

of their patients dead. Considering the large number of victims, and the scale of

killing by hunger in particular, the 1,018 psychiatric patients whose deaths have been

documented probably represent only a portion of a larger total, especially as the popu-

lation of the asylums might have been much higher than the 200 that Vaic

ˇiuˉnas

assumed in 1941. Realistically, the number of victims must be between 1,200 and

1,500. Vaic

ˇiuˉnas provided the above-mentioned figure of 1,340 psychiatric patients in

1941; this, plus gaps in the literature, permits us to guess that the death toll was con-

siderably higher than the number we can document.

Lithuanian Reactions to Nazi

“Euthanasia”

The involvement of local actors in, and local perceptions of, these events make it clear

that the murder of the mentally ill bore at least one similarity to the mass crimes of

the Holocaust: while both were initiated and organized by the German occupying

power, both left options for responses, choices, and initiatives by Lithuanians.

A key actor on the Lithuanian side was the above-mentioned Matulionis, head

of the health department. He had direct contact with Generalkommissar von Renteln

and knew the situation in Lithuanian psychiatric hospitals well. Moreover, it is almost

certain that his superior, Gen. Petras Kubiliu

ˉnas, Generalrat of the Interior (in effect

head of the administration), was also well informed. After the war Matulionis claimed

to have saved many mentally ill patients. When Dr. Eberhard Obst, responsible for

health issues at the Generalkomissariat Litauen at Kaunas, told him in summer 1942

about plans to murder the remaining mentally ill patients, Matulionis supposedly

254

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

mobilized a coalition of church of

ficials, intellectuals, and others to oppose this, by

force of arms if necessary:

I told [the Germans] in great detail how much they would materially, politically, and

morally lose in Lithuania [if they killed 300 chronic patients who were dependant on the

state]. I reminded them of the inevitable and uncompromising condemnation of their

actions by the Catholic Church and indicated its negative impact on food levies, paid by

Lithuanian farmers, desperately needed by their army. It was a long speech, about forty

minutes. In conclusion, I suggested they . . . reconsider and drop their plans to extermi-

nate mental patients. . . . The Generalkommissar even thanked me for such a thorough

analysis of the issue.

74

Whether in response to this or to other considerations, von Renteln decided to put

a stop to this Aktion, notifying the Reichsministerium in Berlin, which supported his

decision.

I have found no archival proof to corroborate Matulionis

’s account. In 1942 an

armed resistance was already in place, but it didn

’t work closely with the Lithuanian

administration. For his part, von Renteln seems not to have been timid, so it is hard to

believe that he would have left such a challenge unanswered. He often spoke of

Lithuanians as

“stupid, lazy, and cowardly.” For example, in 1943 when Lithuanian

of

ficials objected to and resisted recruitment of their countrymen into the Waffen-SS,

Theodor Adrian von Renteln, Generalkommissar Litauen (center); and former chief-of-staff Gen. Petras

Kubiliu¯nas (in bowler hat), Generalrat des Inneren (Secretary of Interior, de facto head of Lithuanian

administration). Kaunas, August 1941. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Eliezer

Zilberis.

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

255

he arranged for the Sicherheitspolizei to arrest leading members of the Lithuanian

elite (as early as January 1942, organs of the RSHA had arrested members of the

nationalist resistance).

75

As for the story about von Renteln and Rosenberg

’s

Reichsministerium, the murder of the mentally ill in any case was organized and con-

ducted by the Einsatzgruppen; the ministry had little or no in

fluence on this sort of

decision-making

—except over reducing food rations, which it in fact did. Bearing in

mind the strong rivalry between the RSHA and the Ostministerium, it is quite

improbable that the latter would have been negotiating with Lithuanian of

ficials over

what the Sicherheitspolizei should and should not do.

Responding in August 1942 to a request by the director of the hospital that

treated venereal diseases in Kaunas for greater food supplies, Matulionis conveyed to

him the German point of view:

“There will be no additional food rations for mental

patients and patients who suffer from chronic and venereal disease in Lithuania, as

such patients in Germany are also not provided with additional food.

”

76

This may

seem to express Matulionis

’s neutrality, but the latter had himself forwarded the

request to von Renteln, and had very frankly reiterated the Germans

’ hunger policy,

belying any notion that he was a critic of Nazi euthanasia. Indeed, archival evidence

provides a contrary picture: on January 23, 1942, as the mass starvation of mental

patients already was under way and some hundreds already were dead in Vilnius

alone, Matulionis wrote to the Generalkommissar:

“Enclosed I send you the list of the

mentally ill . . . patients at the psychiatric hospital in Vilnius and in the asylums in

Ru

ˉdiškes-Valkininkai. [These] are from various places in Poland (Warsaw, Posen,

Sosnovitz, etc.) and from the Soviet Union (who arrived in 1941). I ask the

Generalkommissar if he would like to order that all patients (foreigners) who are not

from Lithuania be transferred to their earlier living places as the food and health care

of the ill involves large expenditures.

” The attached lists included forty-four patients

from Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital and an additional sixty-seven from the asylums—a

total of 111.

77

Obviously, Matulionis wanted to get rid of unwanted

“eaters,” or at

least was willing to do so in order to gratify the Nazis.

Since all the listed patients were non-Lithuanians, it would seem that

Matulionis had in mind a de facto ethnic cleansing. Vilnius Psychiatric Hospital

housed many non-Lithuanians patients at this time because Vilnius had become part

of Poland in 1920 and only in 1939 had returned to Lithuania. It seems clear that

even if Matulionis did not explicitly request the killing of the patients, he was openly

inviting this in his communication with the Generalkommissar. On October 9 and 10,

1942, about twenty patients from Matulionis

’ list still remaining alive were “released”;

it is quite probable that these

“foreign” patients were taken away by the

Sicherheitspolizei to be killed, a delayed result of the January 23 communication.

78

All of these twenty had been on the list of 111, and it remains uncertain how many out

of the original 111 had died, been released, or escaped as of fall 1942.

256

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Other actors played signi

ficant roles. For example it was Antanas Smalstys,

79

the

director of Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital, who originally had written about the

non-Lithuanian patients—to Matulionis—asking in December 1941 for their “trans-

fer.

” Smalstys stressed two considerations. First, the foreign patients would “occupy

places needed for Lithuanians

”; and second, treating foreign patients would be too

expensive.

80

I shall return to Smalstys

’s role, but we should note here that his and

Matulionis

’s efforts to ethnically cleanse the mentally ill reflect a general attitude on

the part of Lithuanian actors eager to make their country more homogeneous. This

sentiment was just as typical in the other Baltic nations.

81

Most historians agree that

only a limited number of Lithuanians were directly involved in the Holocaust as police

or administrative of

ficials, but that no small part of Lithuanian society at the time

approved, if not the killing of the Lithuanian Jews, then the ethnic cleansing that

resulted from it.

82

This antisemitism was the result of traditional Catholic

anti-Judaism, the misperception of the Soviet occupation of 1940–1941 as “Jewish”

rule, and the contemporary drift throughout Eastern Europe toward the pursuit of

ethnic homogenization. Turning over

“foreign” psychiatric patients to the German

authorities, however, was not merely a contribution to ethnic cleansing, but also a con-

scious act of murder.

In neighboring Latvia, Nazi euthanasia became a public issue as citizens asked

the Latvian administration in 1943 about relatives in psychiatric facilities (these inqui-

ries likely related to killings carried out in December 1942; I have not yet discovered

documentation of earlier inquiries). The Latvian administration decided to admit that

these people

’s loved ones had been handed over to the Sicherheitspolizei.

83

The

murder of the mentally ill was openly criticized in a 1943 book on eugenics by a

Latvian psychiatric health of

ficial, Teodors Upners, himself an advocate of other

radical eugenic measures such as forced sterilization.

84

Upners rejected euthanasia,

however

—although not because it was uncivilized, but rather because the killing of

psychiatric patients might undermine popular acceptance of eugenics, and therefore

of the national eugenics program Latvia had initiated in 1937.

85

Ironically perhaps,

the publication of Upner

’s book was nonetheless a sign of rising Latvian resistance to

the German occupation.

Euthanasia became a public issue in Lithuania as well, at least among the more

educated section of the population. Starvation of the mentally ill had been justi

fied in

medical journals as acceptable during wartime.

86

However, we know of no incidents

indicating rising interest on the part of relatives. In the May

–June 1943 issue of the

scienti

fic journal Lietuviškoji Medicina, the main medical and public health periodical

in Lithuania, Dr. Jonas

Šliuˉpas published an article entitled “What Do We Need?”

advocating euthanasia as a means to ease the suffering of the mentally ill:

“incurable

patients (the bedridden, syphilitics, consumptives, the insane, alcoholics, et cetera)

who suffer a great deal and are unable to enjoy their lives. [These] often call for the

reaper with his poisonous sting, but he does not come. In such cases, a medical

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

257

commission should be appointed to assess and con

firm the intractable nature of the

patient

’s condition. . . . A doctor should be allowed . . . to inject the patient . . . to

send him/her to eternal sleep.

”

87

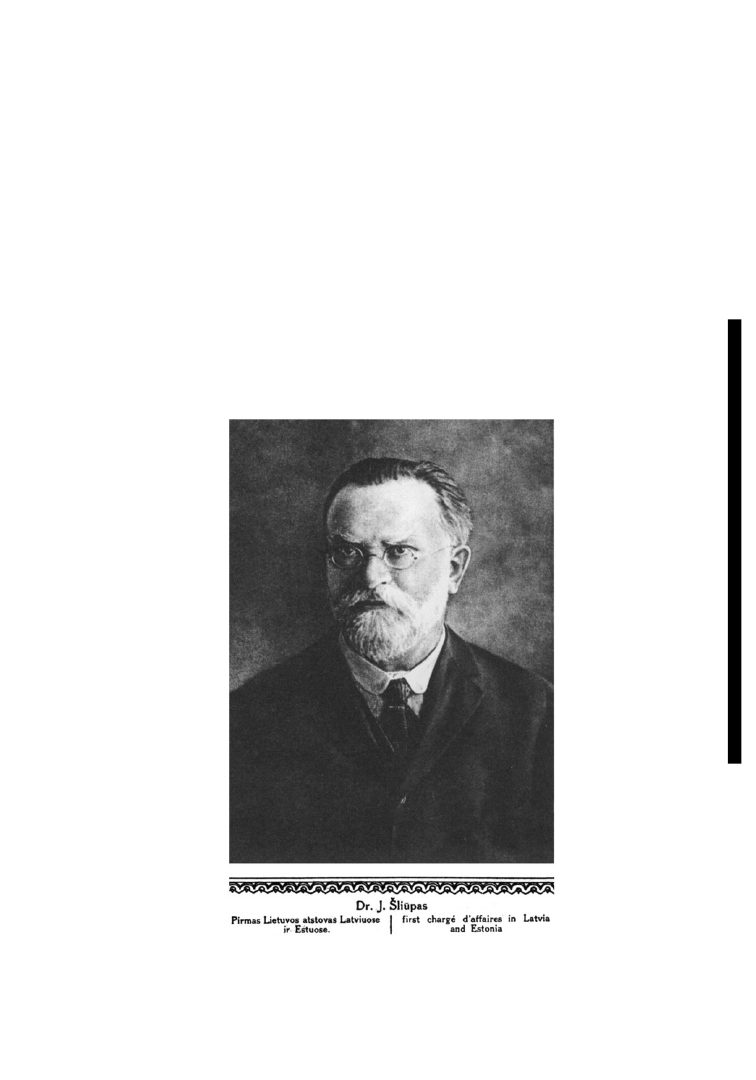

This open call for euthanasia is remarkable even if the majority of psychiatric

patients were already dead. The 81-year-old Šliu

ˉpas was a national icon, a kind of

secular saint of the Lithuanian nation. It is dif

ficult to judge whether his article was an

act of opportunism or genuinely expressed his point of view. Though an important

member of the Lithuanian national movement before the First World War and a

founder of the Republic in 1918,

88

Šliuˉpas seems to have embraced various aspects of

Nazi ideology, writing approvingly, for example, of the deportation of Lithuania

’s Jews

in an unpublished manuscript of 1941.

89

He had become a true believer in eugenics

long before that.

90

Šliuˉpas had studied medicine at the turn of the century in the U.S.,

where eugenics was thriving. Euthanasia was being discussed there even before the

1920 publication of Binding

’s and Hoche’s book on the subject in Germany;

91

Šliuˉpas

most likely had become a supporter of eugenics by the end of his studies in America,

though of euthanasia only after 1941.

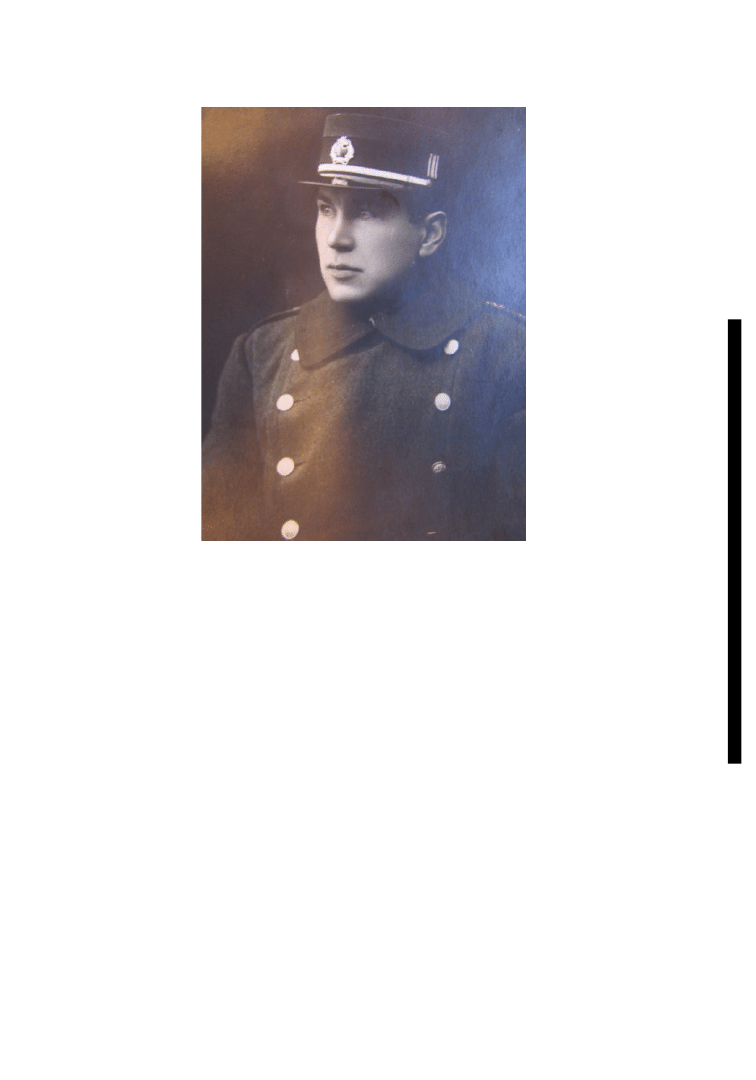

Antanas Smalstys (1889

–1971) during military service, 1922–1923. Director Vilnius Psychiatry from 1939

(takeover from Poland) until arrest December 1944. After Vorkuta forced labor camp (1944

–1954)

returned to Lithuania, appointed director psychiatric clinic in Utena 1957. Photo from KGB

file; courtesy

of Lietuvos Ypatingasis Archyvas.

258

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Not that

Šliuˉpas’s article went unchallenged. Psychiatrist Viktoras Vaicˇiuˉnas pro-

tested in the next issue of Medicina from an ethical point of view,

92

emphasizing the

“unlimited power of medicine” and predicting that the future would bring more effec-

tive ways of relieving the suffering of the mentally and chronically ill while preserving

their lives. Vaic

ˇiuˉnas’s article reproduced a resolution by an August 23, 1943 confer-

ence of physicians, lawyers, social workers, and others at the Vytautas Magnus

University in Kaunas, organized in part to criticize

Šliuˉpas’s praise for euthanasia:

“Dr. Jonas Šliuˉpas’ proposals regarding the elimination of incurable patients are

inconsistent with human morals . . . and inconsistent with medical ethics and with the

goals of medical science.

”

93

Vaic

ˇiuˉnas’s contribution was followed by an open letter from the Metropolitan

Archbishop of Kaunas, Juozapas Skvireckas, to the dean of Vytautas Magnus

University, who as an of

ficial of the Lithuanian church also condemned euthanasia.

94

Jonas

Šliu¯pas as Lithuanian chargé d’affaires in Latvia and Estonia, 1919–1920. Wikimedia Commons.

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

259

It is no surprise the Catholic Church opposed euthanasia, but the movement

’s con-

demnation by the conference attested to a wider rejection among the Lithuanian elite

as well. Still, there may have been contrary opinions that were not published, espe-

cially among those who af

firmed the Nazi occupation or at least sympathized with

National Socialist ideas.

We should bear in mind that in 1943 a much stronger national resistance move-

ment against the Nazi occupation was developing in Lithuania than in Latvia or

Estonia. The Lithuanian administration managed to thwart establishment of a

Lithuanian unit of the Waffen-SS (one was formed in Latvia and one in Estonia),

although they could not prevent mobilization into the Wehrmacht.

95

Opposition to

euthanasia, a program clearly connected to Nazi racial hygiene, may have been an

articulation of a national consensus: protecting all ethnic Lithuanians against the

Germans. This attitude may have constituted a stronger motivation than ethics alone.

Still, many Lithuanian physicians continued to dissent from the medical-ethical values

expressed at the Vytautas Magnus University conference.

Selection for Starvation and the Question of Human

Experimentation

Facing dramatic reductions in food rations, directors of psychiatric hospitals had to

institute a de facto selection process. In Estonia, the Health Administration explicitly

urged hospitals to do so. Such a grisly responsibility could be represented as saving

some patients, but in the

final analysis it reinforced the eugenicist and racist programs

of the occupiers and their collaborators.

96

Since the late nineteenth century, the

ongoing discourse on biological

“degeneration” predisposed medical authorities—and

especially psychiatrists

—toward a particular view of the handicapped. In Lithuania

eugenicists such as Juozas Bla

žys categorized the mentally ill and the “feeble-minded”

as dangers to the future of The Nation. In Latvia some psychiatrists termed the men-

tally ill a

“burden” on society. The cost of caring for them was frequently empha-

sized.

97

In fact, the mentally ill constituted a category of less-valued humans in

Europe generally, not least in the eyes of the medical elite. In Lithuania in 1940 hospi-

tal directors labeled psychiatric patients

“socially dangerous,” doing so, it should be

noted, while the country was under the Soviets.

98

Many medical scientists viewed psy-

chiatric patients rather as objects of research than humans needing treatment; for

them, scienti

fic prestige often was a more powerful motivation than medical ethics.

Surviving

files of the Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital document the starvation

of patients: weights fell dramatically after July 1941 (patients often had gained weight

in treatment facilities prior to the Nazi occupation). One patient lost about 30 kg.

from January to autumn 1941, though the average loss for those months was 10 to 12

kg. In some cases, the weight loss occurred very rapidly, over a mere one or two

weeks. Shortly before their deaths, many patients weighed under 40 kg. (female) or

50 kg. to 60 kg. (male). The situation was similar in other Lithuanian psychiatric

260

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

facilities. Estonian institutions record the same trend.

99

Starvation offered convenient

cover for administrators: since hunger weakens the immune system, simple infections

could be recorded as the cause of death.

But malnutrition and

“defective” immune systems were not the only causes of

death at Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital.

“Medical treatment” also played a pro-

nounced role. In general, the treatment of psychiatric patients during the

first half of

the twentieth century was very rough. Even as the

“reform psychiatry” movement of

the nineteenth century freed patients in mental asylums from chains and blatant phys-

ical cruelty, the perception remained that mental patients were more animal than

human. And there were continuities in brutality. For example, early twentieth century

psychiatry held that

“shock therapy” might “shake up” the minds of patients. In the

1930s several new methods were developed. In 1933 Manfred Sakel contributed

insulin shock therapy to the set of treatment options; it subsequently achieved world-

wide use and remained a common therapy until the 1960s. Patients injected with

insulin fell into an arti

ficial coma, to be brought back to consciousness later.

According to Sakel

’s followers, this treatment was successful in treating schizophrenia,

at least in the disease

’s early stages. Unfortunately, the treatment subjected patients to

severe health risks ranging from permanent brain damage to death; under the best of

circumstances, it was physically exhausting.

100

Shock was also induced with pharmaco-

logical agents such as camphor or cardiazol

—a therapy invented by Ladislaus von

Meduna in 1936

101

—inducing heavy convulsions similar to epileptic seizures. One

year later, Ugo Cerletti developed a

“treatment” that required no medication per se:

electroshock therapy, some forms of which are still in use today.

102

Electroshock had

effects similar to those of cardiazol therapy, and was therefore also called

“electrocon-

vulsive therapy.

” I will not discuss the medical foundations of such therapies here,

though it should be mentioned that no scienti

fic evidence has ever demonstrated con-

clusively that they work. They might, however, be experienced as forms of torture

—

an impression con

firmed by patients who experienced them.

And electroconvulsive treatment was being administered not only at Vilnius but

also at other psychiatric hospitals in Lithuania, among them the Clinic for

Neurological and Mental Diseases at the University of Kaunas.

103

In fact, the majority

of patients who died by 1944 had been treated with electroconvulsive therapy.

We know that in some cases physicians used electroshock

“therapy” to punish or

intimidate patients.

104

Such abuse was all the more likely because shock therapy was

never targeted at any speci

fic neurological or physiological conditions. Indeed, psy-

chiatrists had only limited knowledge of what really happened when patients under-

went any form of shock therapy, let alone what caused mental disease. Such therapies

remained in the experimental stage, and even then were controversial among many

specialists.

None of this prevented these treatments from reaching the Baltics as soon as

they were developed.

105

In the 1920s Julius Wagner von Jauregg invented (in Vienna)

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

261

a therapy to cure progressive paralysis resulting from syphilis, a condition then under-

stood as psychiatric. Wagner von Jauregg

’s treatments involved vaccinating patients

with malaria. The malaria seizures and accompanying high fever were expected to

stimulate the immune system, enabling it to

fight the syphilis (while quinine could be

used to address the malaria). Wagner von Jauregg was in fact awarded the Nobel Prize

in Medicine in 1927 for this work. His form of pyrotherapy was soon imitated in Baltic

psychiatric facilities, including in Lithuania. Insulin, malaria, and electro-convulsive

shock therapies were all in use at Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital before World War

II. Wartime shortages led to the abandonment of insulin therapy, but electro-shock

and pyrotherapies remained terrible secrets of Vilnius Psychiatric Hospital, where in

spite of patients

’ dramatic weight losses, these methods were practiced—often in con-

junction with each other

—throughout the war. Considering the physical toll these

procedures took, it seems likely that they accelerated the death of many patients;

there are several recorded cases of patients who died shortly after undergoing them.

Abraomas Galenci

žekas, a thirty-year-old Jew, was brought from the asylum in

Valkininkai to Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital in November 1940 after having been

diagnosed with schizophrenia. He was treated with electroconvulsive therapy in

December 1940, in February 1941, and

finally from August 1941 until his death on

September 18

—officially caused by a “weak heart.”

106

Galenc

ˇižekas entered the

Marija Bociarskaite

˙ , 27 year-old Lithuanian schizophrenic admitted to Vilnius Psychiatric Hospital August

1940. Housed in colony October

–November 1941. Starting May 1941 received insulin therapy and then

electro-shock treatment; died March 12, 1942. Courtesy of Lietuvos Centrinis Valstybe¯s Archyvas.

262

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

hospital weighing 57 kg. and weighed 68 kg. as late as December 1940; in August

1941, he again weighed 57 kg., but he quickly lost 13 kg. during the two weeks pre-

ceding his death in September. During these two weeks he was subjected to electro-

shock every three days, the last time on September 13. In spite of Galenc

ˇižekas’s

dramatic loss of weight, the therapy was not stopped. It is possible there was a

racist agenda involved, but by no means were all Lithuanian citizens who died under

electroshock Jews or members of other minorities.

For instance, the police brought Teodors Ovc

ˇinikovas to Vilnius State

Psychiatric Hospital on July 16, 1942, a

“schizophrenic” who had been classified

“socially dangerous.” He received daily electroshock treatments from July 20 to July

24 and from July 27 to July 31. On the last day he died during treatment. A postwar

report by Soviet state security notes that relatives had told hospital staff that the

patient was epileptic, not schizophrenic

—so there had been no indication for using

electroshock, but somehow this information failed to reach the medical personnel.

107

In a September 1940 case, the police brought Kazys Jaura to the Vilnius State

Psychiatric Hospital, where he was diagnosed with dementia praecox, then considered

interchangeable with schizophrenia. Jaura was sent to the asylum in Valkininku

˛, but

then on September 6, 1941 brought back, receiving electroconvulsive treatment regu-

larly until December 27. He died one month later, on January 25, 1942, weighing

only 44 kg.; his patient

file indicates no cause of death.

108

Kajetonas Krik

štanas

arrived at Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital in August 1942 with progressive paralysis

resulting from syphilis. He was administered fever-inducing typhus vaccinations and

the anti-syphilis medication neosalvarsan. He died on November 8, 1942, having lost

some 13 kg. and weighing a mere 40.

109

Stranger still is the case of an anonymous Polish man who had been

“found” by

the police and diagnosed at Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital as

“feeble-minded.”

After a term at the Ru

ˉdiškiai asylum he was taken back to the hospital on August 19,

1941 (for reasons unknown); although described as

“physically healthy,” he was

treated with pyrotherapy (vaccinated with both malaria and typhus), and died on

February 24, 1942.

110

Since pyrotherapy originally was developed to treat syphilis, a

bacterial disease, one is tempted to wonder whether it was imposed in this case for sci-

enti

fic or sadistic purposes.

The

“treatments” discussed here were in effect experiments on non-consenting

subjects. Not only were there no established medical protocols for them, but multiple

pharmaceutical agents and techniques were administered simultaneously. Thus Petras

Dambrauskas was treated with electroshocks and later cardiazol in spring 1941, that

is, before the arrival of the Germans; he also received a cocktail of caffeine, strych-

nine, and other drugs typically used to return patients from the arti

ficial coma

induced by insulin therapy (though without the insulin this amounted to testing a new

form of shock therapy).

111

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

263

It is clear that such human experiments were being conducted at Vilnius State

Psychiatric Hospital before the war (including under the Soviets). Even the Nazi

policy of killing by starvation could not deter psychiatrists from taking the opportunity

first to subject patients to these therapies. Perhaps these physicians continued to do so

in order to test patients

’ physical resistance; perhaps for them these unfortunate

people were already doomed, and thus no longer proper objects of pity. Rumors that

Antanas Smalstys conducted strange experiments on patients circulate among psychia-

trists in Lithuania even today.

Therapies conducted in Lithuanian psychiatric facilities were discussed in scien-

ti

fic proceedings. Smalstys, seen as a “pioneer” in electroconvulsive therapy after

having introduced it in Lithuania in 1939, gave a demonstration (whether on a live

subject remains unknown) at a meeting of Lithuanian physicians in 1942.

112

Viktoras

Vaic

ˇiuˉnas, head of the Neurology and Psychiatric Disorders Clinic at the University

of Kaunas, demonstrated the treatment to colleagues

—on live subjects—in 1943.

There is evidence that he practiced this treatment on starving patients; indeed, he was

far from hiding this fact, and was proud his facility could conduct business as usual

under wartime conditions.

113

Another specialist with a scienti

fic interest in the field

was Dr. Napoleonas Indra

šius, Smalstys’s deputy chief. In 1942 Indrašius was a lec-

turer at the University of Vilnius, and he continued his career after the war. He wrote

his second book

—his 1949 habilitation—under Soviet rule, on the electroshock treat-

ment of schizophrenia.

114

Unfortunately, this work seems not to have survived, so we

do not know whether it relied on data from the experiments at Vilnius Psychiatric

Hospital, though this seems likely. One may speculate that Indra

šius’s human experi-

ments re

flected scientific ruthlessness and careerism rather than any pathological or

sadistic character per se; the available evidence makes it harder to say the same

regarding Smalstys.

After the war, both Smalstys and Indra

šius were prosecuted under Soviet law

after they were denounced by former colleagues. Smalstys was arrested in 1944 after

exposure by a Dr. Peskov, who had lost his job in 1941 and had been questioned as a

Communist sympathizer by the Sicherheitsdienst.

115

Smalstys was accused of enlisting

hospital staff in June 1941 to attack the Red Army and to arrest Communists and

Jews. He also was charged with surrendering Jewish patients to the Germans and for

killing patients with electroshock and morphine. In February 1945 he was convicted

under Article 58 (counterrevolutionary crimes) and sentenced to twenty years at hard

labor in the Vorkuta camp complex. He was released in 1955, though barred from

coming within 100 km. of Vilnius. In 1969 he was fully rehabilitated after a medical

commission consisting mostly of Lithuanian physicians concluded that even though

842 patients died during the Nazi occupation, only six did so immediately following

electroshock therapy, and that no clear evidence proved that this treatment was the

cause of their deaths.

116

The commission af

firmed that electroshock therapy accompa-

nied by morphine was a

“normal” procedure.

264

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

The case of Indra

šius was even more surprising. He was charged—only in 1950—

with having killed patients by electroshock and typhus therapy.

117

Denounced by a

Dr. Rubenstein, a former director of the Vilnius State Psychiatric Hospital and now a

Soviet health of

ficial, Indrašius spent a mere six months under arrest in Vilnius. The

evidence against him was contradictory: Smalstys, by then a prisoner in the Gulag, was

brought to Vilnius to give evidence, testifying that as a deputy senior physician

Indra

šius never administered electroshocks and declaring that such treatment was

administered only by himself and two other physicians. Two nurses, however,

reported witnessing Indra

šius administering electroshocks; at the same time, they said

that they never saw anybody die after this treatment. One medical expert con

firmed

that patients had died after electroshocks and vaccination with typhus; yet another

expert, from the Health Ministry of the Lithuanian SSR, stated that such therapies

had not been administered unnecessarily. A commission of doctors investigating the

case found that, even if patients at the hospital died because of this treatment, there

was no proof that Indra

šius was personally responsible, as other clinic personnel had

been involved in treating them.

Admittedly, court judgments under Stalinism did not always re

flect the judicial

norms prevalent in liberal democratic systems; yet in the foregoing cases they afforded

members of the Lithuanian medical elite the opportunity to defend colleagues.

Moreover, during the investigations neither the Nazi strategy of killing patients by

starvation nor inhumane treatment in general was mentioned; investigators did not

dwell on the low body weight of the patients. In general, Soviet security was more

eager to identify

“collaborators” than to punish Nazi-style crimes per se. Indeed,

shock- and pyrotherapies gained wide acceptance in postwar Soviet psychiatry,

of

ficially lauded by the health administration. Any show trial on human experiments

would not conform to propaganda aims: Soviet psychiatrists also experimented on

human subjects with various drugs.

118

Even charges of euthanasia by starvation risked

potential embarrassment, as Soviet psychiatric hospitals in the unoccupied territories

had witnessed high death rates, too: without any Nazi in

fluence the Soviets left psychi-

atric patients to become the

first victim of wartime food shortages (some Soviet

doctors in the occupied territories euthanized patients by injection).

119

After returning from Vorkuta, then, Smalstys was able to continue his career,

becoming director of a psychiatric clinic in Utena. The full, curious, history of

Lithuanian psychiatry remains to be written, and neither the role of Nazi euthanasia,

nor that of people such as Smalstys and Indra

šius, has been fully described.

Conclusions

In Lithuania as in Estonia, the Ostland administration

“euthanized” mental patients

by starving them

—a means that permitted Baltic healthcare practitioners not to think

of themselves as murderers and to present their deeds as unhappy concessions to

wartime necessity. To be sure, some non-Jewish mentally ill persons were shot in

“Euthanasia,” Human Experiments, and Psychiatry in Nazi-Occupied Lithuania, 1941–1944

265

Lithuania. In all, 1,200 to 1,500 mentally ill patients became victims of Nazi,

Nazi-inspired, or Nazi-enabled euthanasia there. The fact that many victims died

under the care of Lithuanian health care professionals and not at the hands of the

occupiers was strangely missed in the postwar testimony of Friedrich Jeckeln, former

“Höherer SS- und Polizeiführer” of the Ostland; Jeckeln assumed that his men had

shot all those martyred mentally-ill patients;

120

but in the end his misinformed admis-

sion re

flected the role of the Nazis not only as killers but also as enablers of a broader

(if not universal) European willingness

—and occasional eagerness—to kill those per-

ceived as dispensable. Several hundred Jewish inmates of both mental and general

hospitals in the Baltic were in fact simply shot by the Sicherheitspolizei, but that

really was part of the Holocaust. As for the others, the

“mentally ill” were widely per-

ceived throughout Europe as

“less valuable” humans, often even by their own families;

the fact that during World War I the institutionalized mentally ill had been allowed to

become the

first to starve served as a precedent for inter-war and World War II attitudes.

No

“Führerbefehl” to eliminate the mentally ill in the occupied Soviet territo-

ries survives. Yet what happened in Lithuania was clearly consistent with the paradigm

of Nazi

“racial hygiene” and with the sort of “improvement” of local populations envi-

sioned under

“Generalplan Ost.” To eliminate the mentally ill was practically a duty

for Nazi of

ficials: all the main Nazi actors in the Baltic were involved—the RSHA, the

Ostland administration, the Wehrmacht. One therefore must question the arguments

of Uwe Kaminsky and others that euthanasia in the occupied territories was a product

of a cruel but pragmatic clearance of space in hospitals for military needs rather than

an ideological goal in itself.

121

This argumentation is comparable to that of scholars

who have suggested that Nazi euthanasia was grounded more in economic than ideo-

logical considerations.

122

Such understandings, however, blur the fact that the notion

of the mentally ill as an economic

“burden” came directly from the eugenics and

social-Darwinist discourse of the late nineteenth century (money spent for social

welfare would

“weaken” society). Arguments of this sort discount the importance of

“racial hygiene” in Nazi ideology. Whatever the motivations, by the end of 1942 the

majority of the

“mentally ill” in the Baltic states had been killed by the

Sicherheitspolizei or by locals on the initiative of the Ostland administration; this sug-

gests an across-the-board German campaign manifesting forethought, planning, and

initiative from higher up. Numerous statements by of

ficials in both the civilian admin-

istration and the RSHA support this view.

One interesting question is why the mentally ill in Lithuania and Estonia were

not simply shot as were comparable patients in other occupied Soviet and Polish terri-

tories. Citing the example of Belorussia, Mary Seeman proposes that the racial catego-

ries of the Nazi occupiers provided the motif: The less

“value” a nation was seen to

have, the more likely it was that the killings there were ideological (i.e., automatic),

and not

“pragmatic” (up to the discretion of the local Nazis in charge).

123

But this

theory does not

fit the Baltic so well. The Nazis saw the Estonians as the most “racially

266

Holocaust and Genocide Studies

valuable nationality,

” and the Latvians as more “valuable” than the Lithuanians. And

yet psychiatric patients were shot almost out of hand in Latvia and starved in Estonia,

but allowed to linger in Lithuania (where they were allowed to starve).

124

Following

Seeman

’s logic, if anywhere the mentally ill should have been killed outright in

Lithuania.

Instead, I suggest taking into account the personal characteristics of the

German actors in charge, an approach that brings in the polycratic character of the

occupational order. Karl Litzmann, the Generalkommissar in Estonia

—characterized

by Anton Weiss-Wendt as one of the more

“humane” Nazi officials in the Ostland—

was at least interested in establishing a good relationship with the Estonian population,

a stance in

fluenced by his “racial” attitude toward the latter.

125

Signi

ficantly, Litzmann

maintained a good relationship with Martin Sandberger, the of

ficer in charge of the

Sicherheitspolizei in Estonia, who was no humanist at all

—but who was a strategic

planner interested in implementing policy with the assent of the Estonians. The

“quiet” killing of the mentally ill by hunger in Estonia fit both these Nazis’ policy of

not jeopardizing German-Estonian relations.

126

In Riga, Reichskommissar Lohse exhibited (as did Generalkommissar Lettland

[Latvia] Otto Heinrich Drechsler) the more peremptory attitude toward the mentally

ill that one would expect of representatives of the