This article was downloaded by: [Uniwersytet Warszawski]

On: 24 January 2014, At: 05:09

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Scandinavian Journal of History

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/shis20

The Cult of St Nicholas in the Early

Christian North (c. 1000–1150)

Ildar H. Garipzanov

Published online: 26 Aug 2010.

To cite this article: Ildar H. Garipzanov (2010) The Cult of St Nicholas in the Early

Christian North (c. 1000–1150), Scandinavian Journal of History, 35:3, 229-246, DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2010.481990

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

“Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever

or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or

arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at

Ildar H. Garipzanov

THE CULT OF ST NICHOLAS IN THE EARLY

CHRISTIAN NORTH (C. 1000

–1150)

The cult of St Nicholas spread in Scandinavia and northern Rus

’ in approximately the same

period, namely in the last decades of the 11th and the first decades of the 12th centuries. In

spite of such a correspondence, the dissemination of the cult in the two adjacent regions has

been treated as two separate phenomena. Consequently, the growing popularity of the cult in

Scandinavia has traditionally been dealt with as an immanent part of the transmission of the

Catholic tradition, and a similar phenomenon in northern Rus

’ has been discussed with

reference to the establishment of Orthodox Christianity. By contrast, the evidence analysed in

this article shows that the establishment of the cult of St Nicholas in the two regions was an

intertwined process, in which the difference between Latin Christendom and Greek Orthodoxy

played a minor role. The early spread of this particular cult thus suggests that, as far as some

aspects of the cult of saints are concerned, the division between Catholicism and Orthodox

Christianity in Northern Europe was less abrupt in the 11th and 12th centuries than has been

traditionally assumed. This was due to the fact that the medieval cult of saints was not

limited to the liturgy of saints, but was a wider social phenomenon in which political and

dynastic links and cultural and trading contacts across Northern Europe often mattered more

than confessional differences. When we leave the liturgy aside and turn to kings, princes,

traders and other folk interacting across the early Christian North, then the confessional

borders are less useful for our understanding of how some aspects of Christian culture were

communicated across Northern Europe in the first two centuries after conversion.

Keywords St Nicholas, cult of saints, Northern Europe

The cult of St Nicholas spread in Scandinavia and northern Rus

’ in approximately the

same period, or in the last decades of the 11th and the first decades of the 12th century. In

spite of such a correspondence, the dissemination of the cult in the two adjacent regions

has been treated as two separate phenomena. Consequently, the growing popularity of

the cult in Scandinavia has traditionally been dealt with as an immanent part of the

transmission of the Catholic tradition, and a similar phenomenon in northern Rus

’ has

been discussed in relation to the establishment of Orthodox Christianity. The separate

treatments have been based on the traditional assumption that Western and Eastern

Christianity became profoundly different by the 11th century, and that the schism of

1054 simply confirmed this religious division in formal terms. But, how wide was this

divide? As Paul Magdalino has noted,

‘it is true that the twelfth century saw the

Scandinavian Journal of History Vol. 35, No. 3. September 2010, pp. 229

–246

ISSN 0346-8755 print/ISSN 1502-7716 online

ª 2010 Taylor & Francis

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

DOI: 10.1080/03468755.2010.481990

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

deepening of the ecclesiastical schism between Greek East and Latin West. Yet the

schism deepened in a context of growing, not diminishing, contacts at all social levels

’.

1

In a similar vein, I will argue that the culture of sanctity in 11th- and 12th-century

Northern Europe was not abruptly divided along the borders created by confessions and

liturgical languages. A number of universal saints known in the Christian East and West

began to be venerated in Scandinavia and northern Rus

’ in those centuries, and the

establishment of the cult of some universal saints in these regions developed as closely

related processes.

2

The establishment of the cult of St Nicholas in Scandinavia and

northern Rus

’ provides a good example of such a coterminous process, one in which

the differences between Latin Christendom and Greek Orthodoxy played a minor role.

1.

The transmission of the cult of St Nicholas in the early medieval

West (the 9th-11th centuries)

The traditional view on the transmission of the cult of St Nicholas in early medieval

Europe, established after the works of Karl Meisen and Werner Mezger, can be

summarized as follows:

3

it appeared first in Byzantium in the early Middle Ages and

then penetrated southern Italy. By the 9th century, the cult was transmitted to the

territories with a Latin rite and became known in papal Rome, and the first Roman pope

with such a name, Nicholas I, is an obvious testimony to the growing popularity of the

saint in Western Europe. In the same century, St Nicholas was already mentioned in

several Carolingian martirologia, most of which were produced in eastern Frankish

territories. Furthermore, his relics were venerated in Fulda as late as 818, and

his name was included in the litany of saints written in Lorsch in the mid-9th century

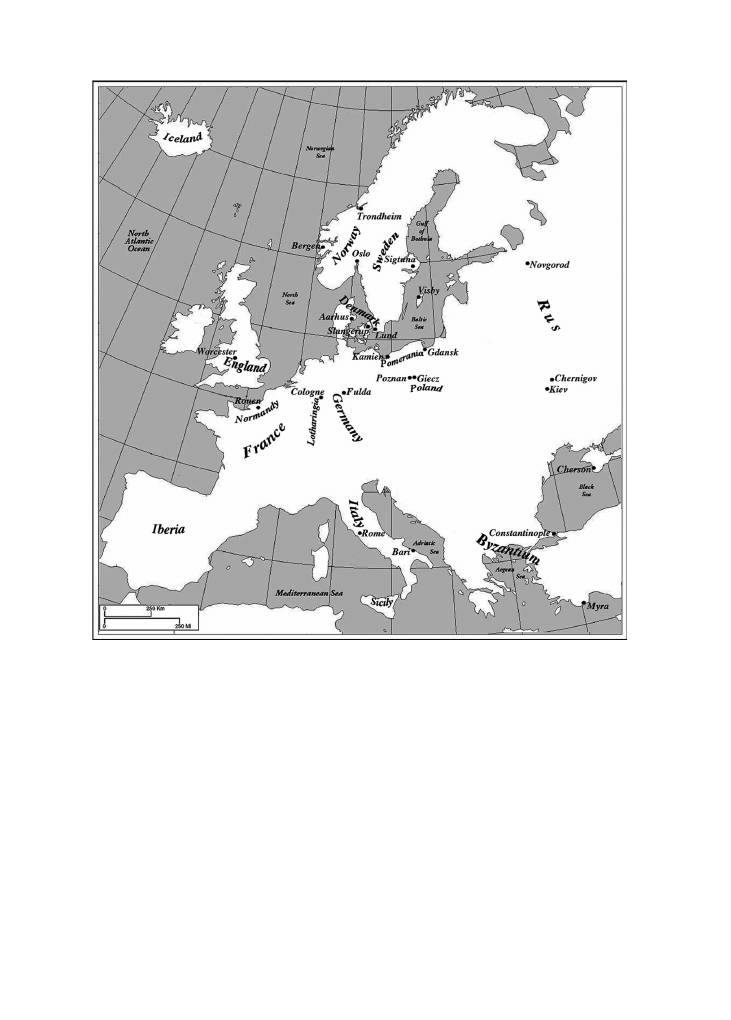

(Figure 1 provides a map of the key locations mentioned in this article). It is noteworthy

that

– as pointed out by Byzantine scholars – around the same time, in the first half of the

9th century, the cult of St Nicholas had spread to Constantinople; in 880, Emperor Basil I

founded the Nea Church, a palatine church partly dedicated to St Nicholas.

4

A century later, the cult became well established in Ottonian Germany, and the

connection between the Ottonian and Byzantine courts, personified by Empress

Theophano, might have contributed to this development. The new Latin Lives of St

Nicholas, written by Reginald of Eichstätt between c. 966 and 991 and by Otloh of

Emmeram in the first half of the 11th century, exemplified the importance of Ottonian

Germany for the dissemination of the cult around the year 1000.

5

Scholars disagree on the way the cult was transmitted after the year 1000.

Traditionally, the foundation of the Norman state in southern Italy has been considered

crucial for the popularity of the cult in Normandy in the first half of the 11th century.

Thereafter, as the holy patron of sailors and merchants, St Nicholas became the tutelary

saint of the Normans, and they became the main agents popularizing his cult in England

and Scandinavia.

6

At the same time, Charles Jones has emphasized an original connection of

St Nicholas

’s liturgy to Lower Lotharingia, and has pointed to local cathedral culture

in the second half of the 10th century as the place where the cult of St Nicholas was

developed under a Byzantine influence, to be transmitted to England and France after the

year 1000.

7

A teutonicus Isembert, an abbot in Rouen (1033

–54) and chaplain of the

Norman Duke Robert, was the person linked to the promotion of St Nicholas

’s cult in

Normandy in the 1030s and 1040s; his German origin corroborates the significance of a

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

230

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

German influence for the growing popularity of the saint in Normandy in the second

quarter of the 11th century.

8

Véronique Gazeau has even suggested that Isembert might

have brought a relic of St Nicholas from Germany, which could have boosted the saint

’s

cult in Normandy.

9

The manuscript tradition of the Anglo-Saxon litanies of saints, in which St Nicholas

was first included in the mid-11th century, seems to corroborate the original connection

of the cult in England to the middle Rhine region, rather than Normandy. The saint is

listed in litanies in two Cambridge Corpus Christi College manuscripts written in the

middle of the 11th century, Mss. 163 and 391. The names of the local saints mentioned in

Ms. 163 link it directly to Cologne. The second codex, Ms. 391, is of Worcester

provenance.

10

Another manuscript produced for the Worchester Cathedral c. 1060

(British Museum, Ms. Cotton Nero E. 1) contains the Office of St Nicholas and Jones has

pointed to Bishop Wulfstan as the main promoter of the cult in Anglo-Saxon England.

11

FIGURE 1 Europe (c. 1000–1150).

THE CULT OF ST NICHOLAS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN NORTH

231

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

E. M. Treharne agrees with Jones and presents other liturgical evidence from England

–

the early vitae of St Nicholas and prayers addressed to the saint

– showing that the cult of

St Nicholas was first established in Worcester and other major religious centres in the

west of England just before the Norman Conquest.

12

It is important to note in this regard

that Jones has also presented evidence for direct contacts between Worcester and Lower

Lotharingia at that time.

13

Notwithstanding that Charles Jones must have been correct in stressing that

St Nicholas

’s cult penetrated Normandy and Anglo-Saxon England initially from

Ottonian Germany, it is only after the Norman Conquest and under the influence of

Normans that the saint began to be repeatedly chosen as a titular saint for churches and

abbeys in England, especially among Norman ecclesiastical foundations.

14

This fact corre-

sponds to the leading role of Normans in the propagation of the cult in Western Europe in

the second half of the 11th century. The most influential event in this process was, of

course, the translation of the relics of St Nicholas from Myra to Bari in 1087, undertaken by

Italian Normans,

15

which led to the establishment in 1089 of the Catholic feast on 9 May

dedicated to this event. As a result of these developments, St Nicholas became a popular

saint all around Europe during the 12th century, when the number of Latin manuscripts

with the hagiographic works dedicated to the saint increased considerably.

16

2.

The spread of the cult of St Nicholas in early Rus

’ (c. 1000–1150)

2.1.

The cult in southern Rus

’ in the 11th century

The cult of St Nicholas in early Rus

’ has been presented within the above-mentioned

‘divided West and East’ paradigm as shaped exclusively by a Byzantine influence. So,

Western scholars like Meisen and Jones have uncritically referred to the entry from the

Primary Chronicle

that mentions a church of St Nicholas in Kiev in its record of the year

882.

17

Yet, in this entry, a church of St Nicholas is mentioned in an early-12th-century

narrative in order to identify for the author

’s contemporary readers the place where the

mythical Viking leader Askold had been buried more than two centuries earlier.

18

Kievan

Rus

’ was officially converted by Prince Vladimir the Great more than a century after 882,

when St Nicholas was unknown in both Rus

’ and Scandinavia. Hence, this reference

should be taken for what it is, namely an act of remembrance of the distant past at a time

when the cult of St Nicholas became popular in Rus

’ in the late 11th and early 12th

centuries. This misunderstood reference apart, surviving evidence suggests that the cult

of St Nicholas began to spread in early Rus

’ at approximately the same time as in

Normandy and England.

It is beyond doubt that the knowledge and veneration of St Nicholas were brought to

early Rus

’ along with the Byzantine cult of saints. His feast on 6 December was

celebrated in the early Russian liturgy in accordance with the Byzantine tradition,

19

and there is ample evidence that the saint was highly respected in 11th-century Kiev. For

instance, St Nicholas was depicted together with the most venerated church fathers in the

apse of St Sophia in Kiev in the 1040s.

20

St Nicholas

’s popularity in southern Rus’ in the

mid-11th century can be corroborated by the fact that Sviatoslav Jaroslavich, prince of

Chernigov from 1054 to 1073 and grand prince of Kiev from 1073 to 1076, became the

first Rurikid to choose the name of St Nicholas as a baptismal name and to place it along

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

232

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

with the image of the patron saint on his princely seals.

21

Moreover, the Life of Feodosij,

written by Monk Nestor in the Kievan Caves Monastery in the mid-1080s, mentions that

the mother of this first monastic saint (d. 1074) in early Rus

’ was admitted by a local

princess to a convent of St Nicholas in Feodosij

’s lifetime – that is, in the third quarter of

the 11th century.

22

Yet, the existence of such a convent cannot be corroborated by other

written evidence. Furthermore, in his Lesson on St Boris and St Gleb written approxi-

mately between 1075 and 1085, Nestor stresses the importance of St Nicholas

’s feast day

on 6 December in the description of a posthumous miracle of the holy brothers, which

suggests the importance of the saint

’s cult in Kiev at the time and in the Kievan Caves

Monastery in particular. In the same miracle, Nestor also mentions a church of St

Nicholas,

23

which might have been founded in Kiev by Prince Sviatoslav, occupying

the Kievan throne from 1073

–76. Such a foundation would have corresponded to the

pattern displayed by Sviatoslav

’s brothers. When ruling in Kiev, they founded churches

dedicated to their own patron saints, correspondingly, Iziaslav to St Michael (1070) and

Vsevolod to St Andrew (1086).

24

The church of St Nicholas mentioned by Nestor may

also well be the same one as referred to in the Primary Chronicle in its record of 882.

2.2.

The growing popularity of the cult in Novgorod in the late 11th and the first half of

the 12th centuries

In contrast to Kiev in the south, St Nicholas seems to have been slightly less popular at the

time in Novgorod. At least, he is not mentioned in a list of major liturgical feasts of autumn

and early winter written on a birch-bark letter (no. 913) found in the early administrative

headquarters of Novgorod in the layer of the third quarter of the 11th century. Meanwhile,

this list mentions such popular holy figures as St Demetrios, St Cosma and St Damian,

St Barbara and St Michael the Archangel.

25

It seems that the less-prominent position of

St Nicholas in Novgorod compared to Kiev mirrored the influence that the clan of Iziaslav, a

brother of Sviatoslav Jaroslavich, exercised in that northern town in the 1050s and 1060s.

In the 1060s and 1070s, the two brothers were fighting for the Kievan throne, with the

result that Iziaslav and his family had to flee to Poland and Germany in 1073 and remain

abroad until the death of Sviatoslav in 1076. It is known that a son of Sviatoslav, Gleb, was

prince of Novgorod from c. 1068 to 1078. Hence, the birch-bark calendar must have been

written before c. 1068, when Iziaslav

’s clan promoted his patron saint, St Demetrios and

the patron saint of his son Sviatopolk, St Michael, but must have discouraged the promotion

of the patron saint of his rival relative, St Nicholas. This antagonism must have faded away

after Gleb became prince of Novgorod c. 1068, and another birch-bark letter (no. 914)

found at the same site and probably written in the 1070s mentions St Nicholas along with

St Clement and St Demetrios.

26

Novgorod became much more important for the cult of St Nicholas in Rus

’ in the

12th century, and the saint became more popular in the north of medieval Rus

’ than in

the south.

27

A stone church dedicated to St Nicholas was founded in Novgorod in 1113,

becoming the second largest in the town after the Episcopal Cathedral of St Sophia, which was

located on the other side of the Volkhov River dividing the city into two parts.

28

The precise

location of this newly built church of St Nicholas also emphasized its importance: it was built

adjacent to Novgorod

’s market, which was the centre of both trade and social life.

29

A later legend connected this event to the discovery of a miraculous round icon of St

Nicholas floating along the Volkhov River. This story relates to the fact that the earliest

THE CULT OF ST NICHOLAS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN NORTH

233

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

surviving icons of the saint were produced in northern Rus

’ in the 12th century, and

fragments of a bronze frame for an icon of St Nicholas were found in Novgorod, in a layer

dated to between 1125/30 and 1185/90.

30

Such references to icons are significant, since

in the Orthodox Church miraculous icons of saints played a role similar to saints

’ relics in

the West. So, a vibrant cult of a saint could have been established around a miraculous

icon, even without authentic relics.

It is important to emphasize again that the growing popularity of St Nicholas in

Novgorod corresponds to the period when the town was no longer controlled by the

clan of Iziaslav. The church of St Nicholas was founded by a grandson of Vsevolod

Jaroslavich, Mstislav (prince of Novgorod from c. 1091 to 1095

31

and 1096 to 1117 and

grand prince of Kiev from 1125 to 1132) and completed by his son Vsevolod (prince of

Novgorod from 1117 to 1136). From the time of its foundation, that church was closely

linked with Novgorodian princes; for example, in 1136, amidst a civil conflict between the

Novgorodians and princes, the Novgorodian bishop Nifont refused to perform the marriage

ceremony of Prince Sviatoslav Olgovich in St Sophia, and the prince instead had his wedding

ceremony performed by his own priests in the Church of St Nicholas. This connection of the

cult of St Nicholas with Novgorodian princes was further confirmed by the foundation of

another church dedicated to this saint at the princely residence in 1165.

32

At the same time, the Novgorodian urban elite also began to patronize the cult of St

Nicholas in Novgorod, which became especially important from the late 1130s onwards,

due to diminished princely authority in the town. The First Novgorod Chronicle did not fail to

mention that posadnik (the head of the Novgorodian civil administration) Dobrynia died in

1117 on 6 December; that is, on the feast day of St Nicholas.

33

Furthermore, in 1135

–36, a

powerful Novgorodian boyar and/or merchant, Irozhnet, demonstrated his dedication to

the cult by founding a church of St Nicholas in the Nerevskij konec.

34

It is exactly in this

decade (the 1130s), when we have clear evidence of the popularity of St Nicholas among

the urban elite engaged in international trade, that the First Novgorod Chronicle notes some

trading expeditions of Novgorodians to the western shores of the Baltic Sea.

2.3.

The translation of the relics of St Nicholas to Bari and early Rus

’

The growing popularity of St Nicholas in Novgorod in the first half of the 12th century

corresponds to a similar process in Northern Europe, which raises the question of to what

extent the Novgorodian development was linked to the West. The Catholic feast on

9 May, dedicated to the translation of the relics of St Nicholas from Asia Minor to Bari in

southern Italy, was hardly acceptable to the Byzantine Church. By contrast, the new

Western feast was incorporated into the early Kievan liturgy almost immediately (the

feast of Nikola veshnij)

– probably between 1089 and 1093

35

– testified to by the original

early Russian text, a sermon on the translation of the relics of St Nicholas to Bari,

composed soon after this event.

36

On the one hand, the Kievan archbishop Nicholas

(c. 1091

–1104) could have had a personal interest in the promotion of the feast of his

namesake.

37

On the other hand, Nazarenko suggests that the tight contacts of early Rus

’

and its rulers with Western Europe must also have contributed to the introduction of the

feast in Kiev. In his opinion, Grand Prince Vsevolod Jaroslavich had a hand in the

promotion of the new Western feast at the time when the Kievan archbishopric was

vacant.

38

It is important to stress in this regard that in the 1060s and 1070s, Vsevolod was

always on the side of his brother Sviatoslav, and his possible promotion of the new feast

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

234

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

dedicated to the patron saint of his brother would correspond to his earlier political

actions. One way or another, the adoption of this Western feast in early Rus

’ indicates, as

Sophia Senyk puts it,

‘that in the late eleventh century there was as yet no consciousness

of a schism in the Christian Church

’.

39

In this wider European perspective, the dynastic links of Prince Mstislav

Vladimirovich, whom the Novgorodian chronicle credited with founding the first stone

church of St Nicholas in 1113, are quite interesting. His mother was Gytha of Wessex, a

daughter of the last Anglo-Saxon king, Harald; she had fled to Flanders and thereafter to

Denmark to King Sven Estridsen before she married Prince Vladimir Monomakh

(c. 1075).

40

In the West, Mstislav was known as Harald; his mother most likely gave

him this name after his Anglo-Saxon grandfather, in addition to the princely name. She

was a devoted Christian, as illustrated by her probable participation in the first Crusade

and her death in Palestine in 1098/99; and she must have influenced the religious views of

her son, with whom she probably stayed in the final years of her life. Nazarenko has

shown that her close ties with the cloister of St Pantaleon at Cologne led to the

promotion of the saint

’s cult in Novgorod to the extent that Pantaleon became the

patron saint of Mstislav

’s son, Iziaslav. Nazarenko has also suggested that the miracle of St

Panteleon involving Harald

–Mstislav, which can be dated to the 1090s and which was

written down in the cloister of St Panteleon in the early 12th century, influenced the

legend describing the foundation of the church of St Nicholas in Novgorod in 1113.

41

This

evidence is especially significant since, as mentioned above, Cologne was one of the few

centres in Lower Lotharingia that promoted the cult of St Nicholas across Northern

Europe. Gytha

’s connections thus clearly show one of the channels by which the growing

popularity of St Nicholas in Northern Europe might have contributed to the further

promotion of the saint in Novgorod.

3.

The early cult of St Nicholas in Denmark and Norway

(c. 1100

–1130)

3.1.

Medieval Denmark

The cult of St Nicholas began to spread in late 11th-century Denmark, around the time

when Gytha stayed there before her marriage to Vladimir Monomakh in the early

1070s.

42

This can be evidenced by the fact that at that time a son of King Sven

Estridsen, Niels (king of Denmark from 1104 to 1134), was named after the saint.

Thus, the name of Nicholas was introduced into the Danish royal dynasty almost at the

same time as in the dynasty of the Rurikids. The earliest cathedral church of Aarhus has

been traditionally described as dedicated to St Nicholas from the time of its foundation.

43

Based on its architectural features, Hubert Krins has suggested that the church must have

been constructed in the 1070s or 1080s. Krins has also argued that the type of crypt in the

Aarhus Cathedral follows prototypes from the Lower Rhine region, where similar

architectural structures were built up to the middle of the 11th century. Moreover,

the type of church, Saalkirche mit Krypten, is quite rare; another such example is the

church of St Pantaleon in Cologne (dedicated in 980).

44

Thus, the architectural features

of the earliest Aarhus cathedral connect it to Lower Lotharingia, which was pivotal in the

early dissemination of the cult of St Nicholas in Normandy and Anglo-Saxon England.

THE CULT OF ST NICHOLAS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN NORTH

235

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

Yet, this data must be treated with circumspection, since it is only in later medieval

sources that this cathedral church is mentioned as connected to St Nicholas earlier: for

example, the Life of St Niels describes the cathedral as dedicated to the saint in the late

12th century.

45

Furthermore, its later assumed re-dedication to St Clement looks

strange, considering that in Scandinavia St Nicholas became a more popular saint than

St Clement from the 12th century onwards.

46

We are on much safer chronological ground with another early dedication to

St Nicholas in Denmark, namely the Slangerup nunnery on Sjælland, which was one of

the earliest monastic foundations in Denmark and was founded by King Erik Ejegod (king

of Denmark from 1095 to 1103) around the year 1100.

47

Erik Cinthio has suggested that

King Erik acquired precious relics of the saint on his trip to Rome and Bari in 1098,

48

after which the king founded the Slangerup nunnery to host them. The mid-13th-century

Knýtlinga saga

describes him meeting Pope Paschal II and making donations to various

ecclesiastic institutions, and supports this evidence by quoting some stanzas from Markús

Skeggjason

’s poem Eiríksdrápa from c. 1104.

49

Although the saga does not mention Erik

’s

acquisition of relics on this trip, his visit to Bari

– along with references to his generous

donations, which might have been reciprocated with relics

– makes Cinthio’s proposition

quite possible.

By contrast, in the early 13th century Saxo Grammaticus reports a legendary story

that, when King Erik went on his pilgrimage to the Holy Land via Rus

’, he visited

Constantinople and received a collection of relics from the Byzantine emperor. Most of

the relics were sent to Roskilde and Lund, but the relics of St Nicholas and a splinter of

the Holy Cross were sent to the place of Erik

’s birth, Slangerup.

50

The text indicates that

the relics of St Nicholas were treated as the most precious in the collection, but it is less

certain that they reached Slangerup from Constantinople. By the time of Erik

’s pilgrim-

age in 1103, the relics of St Nicholas had already been translated from Myra to Bari,

although some relics of a saint as popular as St Nicholas must have been kept in

Constantinople, close to the imperial palace; for example, in the Nea Church, which

before 1204 was in possession of

‘a great treasure of sacred relics’.

51

This church must

have had relics of the saint to whom it was partly dedicated. All in all, although Saxo

’s

story is impossible to verify, the Byzantine provenance of St Nicholas

’s relics in Slangerup

remains a possibility as plausible as the south Italian one. At the same time, the entire

story might have been invented by Saxo in his attempt to glorify the ancient and recent

Danish kings, presenting them as equal to Roman and Byzantine emperors.

After the foundation of the Slangerup nunnery, almost a dozen churches (eight or

nine) dedicated to St Nicholas were founded in 12th-century Denmark, including the see

of the Danish archbishopric, Lund.

52

If we leave the dubious case of Aarhus aside, none of

these churches were cathedrals. So the Danish evidence shows that the early cult of the

saint in Denmark was promoted by kings like Sven Estriden and Erik Ejegod, with the

open possibility of an influence from Lower Lotharingia, which was so important for the

dissemination of the cult in North-Western Europe. As to the relics of the saint, they

were most likely acquired in Bari or Byzantium.

3.2.

Norway

In Norway, the early cult of St Nicholas can be dated to approximately the same time as

in Denmark.

53

Here the feast of the saint was included in the lists of the most important

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

236

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

holidays in the Gulating Law (Chapter 18) and Eidsivating Law (Chapter 9), most likely

in the first half of the 12th century. This textual evidence corresponds to the earliest

church dedications to St Nicholas in Trondheim and Oslo, which are dated to the early

12th century. The introduction of the cult of St Nicholas in Norway has traditionally been

connected to an English influence, which corresponds to the fact that the earliest

fragment with a part of St Nicholas

’s Office found in the diocese of Nidaros was written

in the west of England

– the main centre of the saint’s cult at the time of the Norman

conquest

– in the early 12th century.

54

At the same time, it is noteworthy that, similar to

the Slangerup nunnery, the earliest church dedications to St Nicholas were connected to

Norwegian royalty. Haakon Christie has stated that the parish church of St Nicholas in

Oslo was built by the year 1100 near the royal castle, although he has not provided any

evidence for such an assertion, and the earliest written reference to this church is dated to

the mid-13th century.

55

The erection of the church in Trondheim can be dated more precisely. According to

saga evidence, the church, embellished with much artwork, was founded in the royal

palace by King Eystein Magnusson, while his brother, Sigurd Jorsalfar (1103

–30),

travelled to Jerusalem and visited England, Iberia, Sicily, Byzantium (including

Constantinople) and Germany from 1108 to 1111.

56

Still, it is possible that the church

in question was founded by Sigurd upon his return to Norway, since if some of the relics

of St Nicholas were deposited at the time of foundation, then they must have been

brought by Sigurd, not Eystein. Sagas report, for instance, that Sigurd brought a splinter

of the Holy Cross from his voyage. Moreover, St Nicholas was popular in most of the

regions Sigurd visited, which might have influenced his choice of church dedication. He

might also have acquired a relic of St Nicholas on his voyage

– for example, in

Constantinople. In addition, later sources from Bergen state that King Eystein founded

a church of St Nicholas in that town, which may explain the later confusion with a similar

dedication in Trondheim. The church of St Nicholas in Bergen is mentioned in written

sources as existing in the late 12th century and the late-19th-century excavations of its

remains showed a Romanesque stone structure of the 12th century.

57

It is known that

Eystein founded the Munkeliv monastery in Bergen, dedicated to St Michael. A marble

royal head with the inscription Eystein rex has been found there and dated to the second

quarter of the 12th century. According to Knut Helle, this is an artefact without any

parallel in medieval Norwegian art, and King Eystein is presented here wearing a crown

of the Byzantine type.

58

So, similar to Erik Ejegod

’s possible acquisition of St Nicholas’s

relics in Constantinople, a Byzantine link might have been of some significance in the case

of the Norwegian kings Sigurd and Eystein.

Another important fact is that in the years following his southbound voyage, Sigurd

married Malmfrid, a daughter of Prince Mstislav, the prince who as mentioned above

founded the stone church of St Nicholas in Novgorod in 1113, at approximately the same

time that a similar church was founded in Trondheim. Thus, it is difficult to avoid

the conclusion that a dynastic connection between the two royal families in Norway and

Rus

’ might also have been somehow involved in these parallel dedications. It is also

noteworthy that a Varangian church of St Olaf, whose cult was focused on Trondheim

(the main town of Sigurd

’s realm), was built in Novgorod, most likely in the early

12th century.

59

Moreover, the mother of Malmfrid was Kristina, the daughter of King Ingi

Steinkelsson of Sweden; Malmfrid

’s sister was Ingeborg, who married Knud Lavard, a

THE CULT OF ST NICHOLAS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN NORTH

237

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

son of Erik Ejegod.

60

Finally, after the death of Sigurd in 1130, Malmfrid married Erik

Emune, who soon thereafter defeated King Niels (Nicholas) and became king of

Denmark. This short overview of the tight matrimonial ties between the ruling families

in early-12th-century Norway, Denmark, Sweden and northern Rus

’ suggests that the

promotion of St Nicholas by one family would have easily become known to the others

and would have encouraged them to make similar church dedications. Thus, regardless of

whether or not a Byzantine influence or the role of a

‘Sigurd–Mstislav’ connection is

true, the presented evidence points to the crucial role of royal families and their dynastic

contacts in the early spread of the cult of St Nicholas in Scandinavia.

4.

The early church dedications to St Nicholas in the Baltic region

(the 12th century)

4.1.

Pomerania

The evidence from Denmark and northern Rus

’ shows that the cult of St Nicholas

was established on the western and eastern shores of the Baltic Sea at the turn of

the 12th century. In this perspective, the early church dedications to the saint in the

12th-century Baltic region are quite interesting. In northern and central Poland,

the earliest churches dedicated to St Nicholas seem to date to the 12th century; in

Giecz, the earliest structure of such a church has been dated to the late 11th century.

61

In

Poznan, a similar church existed in the 12th century.

62

The existing data also suggests

that church dedications to St Nicholas became very popular in Pomerania at the early

stage of Christianization; that is, in the 12th century.

63

The first evidence of this trend is

Gdansk, where, according to archaeological data, the church of St Nicholas seems to have

been one of the earliest churches and can be dated to as late as the second half of the 12th

century.

64

The second example is the town of Kamien in Western Pomerania, which

developed as a large fortified settlement in the 11th century, where a church dedicated to

the saint was probably founded in the 12th century.

65

It is important to notice that

Kamien was located on the trade route from northern Germany to the Novgorodian

territory. In both lands, the cult of St Nicholas became popular in the 12th century and

could thus offer a unifying patron saint for sailors and merchants involved in the trade

across the Baltic. In this role, St Nicholas might have easily appealed to townsfolk

involved in the Baltic trade, regardless of their confession. During their business

transactions, they could equally swear oaths by his name in different towns involved in

trade across the Baltic, such as Novgorod or Gdansk. The location of the earliest stone

church of St Nicholas in Novgorod, adjacent to its market, is quite telling in this regard.

4.2. Medieval Sweden

Sigtuna probably had the earliest church of St Nicholas in Sweden. This church was referred

to in written sources as early as 1304 and described in the 17th century as a Russian church.

It has been suggested that, in the Middle Ages, St Nicholas Church functioned as a private

church and the church of merchants. There are ongoing excavations around its place in

Sigtuna, and it seems that the stone church can now be safely dated to the second half of the

12th century.

66

At the same time, Sten Tesch argues that this church was erected in the first

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

238

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

half of the 12th century along with another six stone churches, built as a manifestation of the

new Christian power of the king, bishop and magnates. Indeed, the location of these

churches seems to suggest that there was some degree of coordinated effort in the process

of their construction. Upon completion, these churches created a new sacred street, which

must have been used for ceremonial processions from the church of St Peter to the church

of St Olaf.

67

The church of St Nicholas was right in the middle of that street. Unlike the

other churches, it has three even apses, a nave and two aisles, and reminds us of the

structures of Byzantine provincial churches. Therefore, all these features

– along with

the evidence that this church was known as Russian in the early modern period

– suggest

that it followed an Orthodox rite and that the cult of St Nicholas arrived in Sigtuna most

likely from Novgorod due to intensive political and trading contacts. That is why it has been

suggested that the church of St Nicholas in Sigtuna was founded and owned by Novgorodian

merchants, similar to the church of St Nicholas in Visby, which has been dated to the

second half of the 12th century.

68

Meanwhile, the assumingly Orthodox church seems to

have been built along with the churches following the Latin rite within one building project

supported by official authorities. This feature reminds us of a Byzantine connection and

royal involvement with regard to the early cult of St Nicholas in Denmark and Norway. It

also suggests that, as far as the cult of St Nicholas in Sigtuna is concerned, the distinction

between Latin and Byzantine rites was less important in the 12th century, and that the

churches following the two rites coexisted within a single religious landscape. After all, the

feast of this saint was celebrated in Western and Eastern Christianity on the same day: 6

December. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the saints to whom the early churches of

Sigtuna were dedicated also held prominent positions in Novgorod at the time. The

churches of St Olaf and St Peter following a Latin rite existed there and were owned

correspondingly by the Gotlandic and German merchants and St Peter along with St Paul

was especially venerated in northern Rus

’.

5.

Conclusions

In summary, the analysed evidence shows that, before the turn of the 12th century, the cult

of St Nicholas, originating from the Byzantine town of Myra in Asia Minor, was dissemi-

nated from the European south to the north via two main channels. On the one hand, a

western route connected 9th-century Italy with Carolingian Francia and Ottonian

Germany. In the first half of the 11th century, the cult spread further to Normandy,

and from the mid-11th century to Anglo-Saxon England. Lower Lotharingia and its

cathedral culture seem to have been a key factor in the promotion of the cult of St

Nicholas and its Latin liturgy in North-Western Europe in the 11th century, and it may

well be that the cult first arrived in Denmark in the late 11th century from Lower

Lotharingia. On the other hand, an eastern channel linked late 10th-century Byzantium

and newly converted Rus

’ and its major town, Kiev – with St Nicholas being imported

along with other Byzantine saints. In the 11th century, St Nicholas was also known in

northern Rus

’ and its main centre, Novgorod, but there is no evidence indicating his

popularity there.

The situation began to change at the turn of the 12th century, when these two

routes converged in Scandinavia and northern Rus

’. In the 1090s, the Latin feast

dedicated to the translation of the relics of St Nicholas from Asia Minor to Bari in Italy

was accepted in Kievan Rus

’, but not in Byzantium. Furthermore, in the first half of the

THE CULT OF ST NICHOLAS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN NORTH

239

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

12th century the cult of St Nicholas spread in Scandinavia and northern Rus

’ within one

single process. This growing popularity of St Nicholas was initially due to royal

patronage (especially in the first quarter of the 12th century) and royal dynastic

contacts among the members of the ruling families in Norway, Sweden, Denmark

and Rus

’. This royal involvement may also explain possible Byzantine links for the cult

of St Nicholas in Scandinavia at its earliest stage. At the next stage (probably from the

second quarter of the 12th century and certainly from the mid-12th century), the cult

of St Nicholas was ardently supported by trading elites in the Baltic Sea region,

regardless of their confessional affiliation. St Nicholas provided merchants and sailors

on the Latin and Orthodox shores of the Baltic Sea with a unifying patron saint, whom

they could beseech for holy protection and support on their trading expeditions across

Northern Europe. They could all celebrate the feast of their saint on the same day, 6

December

– unlike some other feasts of universal saints that were performed on

different days in the Latin and Orthodox Churches.

Thus, the material analysed in this article suggests that, as far as some aspects of the

medieval cult of saints are concerned, the confessional division between Catholicism and

Orthodox Christianity in Northern Europe

69

could not interrupt religious interactions

and exchange across the early Christian North until as late as the 12th century. Of course,

the liturgy of St Nicholas was performed differently and in different languages within the

two rites. Yet, the cult of saints was not limited to the liturgy of saints. The cult of saints

was a wider social phenomenon, in which political and dynastic links and cultural and

trading contacts across Northern Europe often mattered more than liturgical, theological

and ecclesiastical differences. When we leave the liturgy aside and turn to kings, princes,

traders and other folk interacting across the early Christian North, then an institutional

approach with its excessive emphasis on confessional borders is less useful for our

understanding of how some aspects of Christian culture were communicated across

Northern Europe in the first two centuries after conversion. It is these wider socio-

political, economic and cultural contexts that explain why St Nicholas was first promoted

by kings and princes in this region, and later became the patron saint par excellence of

sailors and merchants.

Notes

1

Magdalino,

‘Introduction’, xii.

2

For more details, see Haki Th. Antonsson and Garipzanov, Saints and Their Lives,

especially chapters 2

–5.

3

Meisen, Nicholauskult und Nicholausbrauch, 56

–88; summarized in Mezger, Sankt

Nikolaus

, 17

–22. On the convergence of Nicholas of Myra and Nicholas of Sion in

the early Byzantine cult of St Nicholas, see Sevcenko, The Life of St Nicholas, 18

–21.

4

For details, see Sevcenko, The Life of St Nicholas, 20

–1. Its primary dedication seems

to have been to St Michael the Archangel; see Majeska, Russian Travelers to

Constantinople

, 248.

5

For details and references, see Treharne, The Old English Life of St Nicholas, 34

–5.

6

Meisen, Nicholauskult und Nicholausbrauch, 89

–104; and Treharne, The Old English Life

of St Nicholas

, 35

–42.

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

240

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

7

See Jones, The Saint Nicholas Liturgy, 10

–13 and 64–89; and Jones, Saint Nicholas of

Myra

, 140

–4.

8

Jones, The Saint Nicholas Liturgy, 66

–73; and Jones, Saint Nicholas of Myra, 147–9.

9

Gazeau, Normannia monastica, vol. 1, 188

–9, 197.

10

Lapidge, Anglo-Saxon Litanies, 64, 79, 107, 245.

11

Jones, The Saint Nicholas Liturgy, 7

–41.

12

Treharne, The Old English Life of St Nicholas, 39

–40.

13

Jones, Saint Nicholas of Myra, 142

–4. St Nicholas is also included in the litany of the

saints in a Gallican psalter (Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Douce 296), on

paleographical grounds dated to the second quarter of the 11th century, but its

origin remains obscure: Lapidge, Anglo-Saxon Litanies, 78, 237.

14

For details and references, see Treharne, The Old English Life of St Nicholas, 42

–5.

15

On this event and connections between Normandy and the Normans in Apulia and

Calabria, see Chibnall,

‘The Translation of the Relics of Saint Nicholas’, 33–41.

16

See Philippart and Trogalet,

‘L’hagiographie latine du XI

e

siècle

’, 299.

17

Meisen, Nicholauskult und Nicholausbrauch, 57; Jones, Saint Nicholas of Myra, 85.

18

Povest

’ vremennykh let, 76–9.

19

Loseva, Russkije mesiatseslovy XI

–XIV vekov, 218.

20

See Lazarev, Mozaiki Sofiji Kievskoj, 34; and Lazarev, Old Russian Murals, 227

–9.

21

Janin, Aktovyje pechati Drevnej Rusi X-XV vv., vol. 1, 34

–5; Janin and Gaidukov, Aktovyje

pechati Drevnej Rusi X

–XV vv., vol. 3, 115–16.

22

See the Life of Feodosij in Hollingsworth, The Hagiography of Kievan Rus

’, 45.

Hollingsworth thinks that this princess may have been the wife or sister of Iziaslav

Jaroslavich, who was grand prince of Kiev from 1054 to 1073 and 1076 to 1078. On

the dating of the text and related historiography, see ibid., liv

–lx.

23

Lesson on the Life and Murder of the Blessed Passion-Sufferers Boris and Gleb

, in

Hollingsworth, The Hagiography of Kievan Rus

’, 28–9. For the discussion of its dating

and corresponding bibliography, see ibid., xxxv.

24

Povest

’ vremennykh let, 215, 243.

25

Zalizniak, Drevnenovgorogskij dialect, 281

–2.

26

Ibid., 283.

27

Uspenskij, Filologicheskije razyskanija, 31.

28

Novgorodskaja pervaja letopis

’, 20, 203.

29

Dejevsky,

‘The Churches of Novgorod’, 212.

30

See Medyntseva, Gramotnost

’ v drevnej Rusi, 127.

31

On the dates of the early reign of Mstislav, see Nazarenko, Drevniaja Rus

’, 548–50.

32

Novgorodskaja pervaja letopis

’, 24, 32, 209, 219.

33

Ibid., 20, 204.

34

Ibid., 23, 208. For details, see Dejevsky,

‘The Churches of Novgorod’, 215–18.

35

Nazarenko, Drevniaja Rus

’, 358, 557, 596; and Senyk, A History of the Church in Ukraine,

366

–7.

36

For details on this text and the time of its composition, see Cioffari, La leggenda di Kiev,

43

–71.

37

His seals have survived; see Janin, Aktovyje pechati Drevnej Rusi X

–XV vv., vol. 1, 48.

38

Nazarenko, Drevniaja Rus

’, 557–8.

39

Senyk, A History of the Church in Ukraine, 367.

40

See Bolton,

‘English Political Refugees’, 19–20.

41

Nazarenko, Drevnaja Rus

’, 585–616.

THE CULT OF ST NICHOLAS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN NORTH

241

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

42

See Franklin,

‘Kievan Rus’ (1015–1125)’, 91.

43

See Cinthio,

‘Heiligenpatrone und Kirchenbauten’, 168; and Michelsen and de Fine

Licht, Danmarks Kirker: Århus Amt, vol. 3, 1036

–7.

44

Krins, Die frühen Steinkirchen Danemarks, 88

–9.

45

De vita et miraculi beati Nicolai Arusiensis

, 400.

46

Bjørn and Gotfredsen, Århus domkirke, 29

–32.

47

Nyberg, Monasticism in North-Western Europe, 206; and Haki Antonsson,

‘Saints and Relics’,

64.

48

Cinthio,

‘Heiligenpatrone und Kirchenbauten’, 168.

49

Knýtlinga saga

, c. 74, in Danakonungasögur, 217

–20; Phelpstead, ‘Pilgrims,

Missionaries and Martyrs

’, 62; and Haki Antonsson, ‘Claims to Papal Canonizations

of Saints in Scandinavia and Elsewhere

’.

50

‘Et ne ortus sui locum locum veneratione vacuum sineret, Slagathorpiam cum Nicolai

sacratissimis ossibus divini patibuli particulam transtulit

’. Saxo Grammaticus, Gesta

Danorum

, XII.7,4, vol. 2, 80. Haki Antonsson,

‘Saints and Relics’, 64, seems to accept

the reliability of this account.

51

Majeska, Russian Travelers to Constantinople, 249. He adds that

‘by later Palaeologan

times all the relics seem to have been dispersed either in the West or among other

churches of Constantinople

’.

52

Beskow,

‘Kyrkededikationer i Lund’, 54.

53

Margaret Cormack shows that in Iceland, the cult of St Nicholas also spread during the

12th century, most likely around the mid-12th century, slightly after it spread in

Norway: Cormack, The Saints in Iceland, 14, 18, 21, 28, 47, 56, 134

–8.

54

Gjerløw, Antiphonarium Nidrosiensis Ecclesiae, 48.

55

Christie,

‘Old Oslo’, 48–50; and Dietrichson, Sammenlignede Fortegnelse, 6.

56

The Saga of the Sons of Magnús

, 699.

57

Helle, Bergen bys historie, vol. 1, 139

–40. I am thankful to Geir Atle Ersland for

pointing this out to me.

58

Ibid., 114, 662.

59

For details and references, see Jackson,

‘The Cult of St Olaf and Early Novgorod’.

60

The Saga of the Sons of Magnús

, 702.

61

The remains of the first church were found under the area of St Nicholas

’s church.

According to stratigraphical data, the earliest church is dated from the late 10th to

12th or 13th centuries. Teresa Krysztofiak believes that the building techniques

applied there suggest the late 11th century as a probable starting date. See Buko,

The Archaeology of Early Medieval Poland

, 319.

62

Poznan was an episcopal see in the 12th century, and at that time St Nicholas

’s church

existed inside the fortified area of Zagorze. See Kócka-Krenz, Kara, and Makowiecki,

‘The Beginnings, Development and the Character’, 161. In Wisliza, in southern

Poland, St Nicholas

’s church was founded probably as late as the mid-12th century;

Buko, The Archaeology of Early Medieval Poland, 292. According to Joanna Kalaga, this

church was founded in the second half of the 11th or early 12th century; see

Gassowsky,

‘Early Medieval Wisliza’, 345.

63

The bishopric of Wolin was founded in 1140 and subordinated to the Papal Curia. See

Blomquist, The Discovery of the Baltic, 138

–40.

64

Buko, The Archaeology of Early Medieval Poland, 253

–4. Paner, ‘The Spatial Development

of Gdansk

’, 23–7, states that the Romanesque church was built in the newly developed

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

242

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

settlement area in the second half of the 12th century, and the church of St Nicholas was

the second stone church in Gdansk after another one in the stronghold.

65

‘Outside its ramparts there was St. Nicholas’ Church with a biritual cemetery dated to

the 9th

–12th century’. Buko, The Archeology of Early Medieval Poland, 213. This

suggests the 12th century as the time when that church could have been founded.

66

For details and references, see Ros, Staden, kyrkorna, 172

–6; and Wikström, ‘Den

svårfångande kronologin

’, 226.

67

Tesch,

‘Kungen, Kristus och Sigtuna’, 253–4.

68

For details and references, see Ros, Staden, kyrkorna, 175. A silver capsule with the

images of St Nicholas and the Mother of God has been found in central Sweden (at

Almännige in Gästrikland) and provisionally dated to the late 11th century. Piltz, Det

levande Bysans

, 96

–7, considers it a Russian imitation of the Byzantine original, which

would also correspond to Novgorodian connections of the early cult of St Nicholas in

medieval Sweden.

69

For example, see Blomquist, The Discovery of the Baltic, especially 10

–11, who argues

for a profound civilizational division (based on cultural and religious differences)

between the Catholic and Orthodox countries in the Baltic Sea region.

References

Beskow, Per.

‘Kyrkededikationer i Lund’. In Nordens kristnande i europeiskt perspektiv, ed. Per

Beskow and Reinhart Staats, 37

–62. Skara: Viktoria, 1994.

Bjørn, Hans, and Lise Gotfredsen. Århus domkirke: Skt. Clemens. Aarhus: Århus Domsogns

menighedsråd, 2005.

Blomquist, Nils. The Discovery of the Baltic: The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the

European North (A.D. 1075

–1225). The Northern World, no. 13. Leiden: Brill, 2005.

Bolton, Michael.

‘English Political Refugees at the Court of Sveinn Ástrí∂arson, King of

Denmark

’. Mediaeval Scandinavia 15 (2005): 17–36.

Buko, Andrzej. The Archaeology of Early Medieval Poland: Discoveries

– Hypothesis – Interpretations.

East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450

–1450, no. 1. Leiden: Brill,

2008.

Chibnall, Marjorie.

‘The Translation of the Relics of Saint Nicholas and Norman Historical

Tradition

’. In Le relazioni religiose e chiesastico-giurisdizionali: Atti del II

o

Congresso inter-

nazionale sulle relazioni fra le due Sponde adriatiche

, 33

–41. Rome: Centro di studi sulla

storia e la civiltà adriatica, 1979.

Christie, Haakon.

‘Old Oslo’. Medieval Archaeology 10 (1966): 45–58.

Cinthio, Erik.

‘Heiligenpatrone und Kirchenbauten während des frühen Mittelalters’. In

Kirche und Gesellschaft im Ostseeraum und im Norden vor der Mitte des 13. Jahrhunderts

, Acta

Visbyensia, no. 3, ed. Sven Ekdahl, 161

–9. Visby: Museum Gotlands Fornsal, 1969.

Cioffari, Gerardo. La leggenda di Kiev: Slovo o pereneseniji moshchej Sviatitelia Nikolaja. Bari:

Centro Studi e Ricerche

‘S. Nikola’, 1980.

Cormack, Margaret. The Saints in Iceland: Their Veneration from the Conversion to 1400. Brussels:

Société des Bollandistes, 1994.

De vita et miraculi beati Nicolai Arusiensis

. In Vita sanctorum Danorum, ed. Martin C. Gertz,

398

–408. Copenhagen: G. E. C. Gad, 1908–12.

Dejevsky, Nikolai.

‘The Churches of Novgorod: The Overall Pattern’. In Medieval Russian

Culture

, ed. Henrik Birnbaum and Michael S. Flier, 206

–23. Berkeley and Los Angeles:

University of California Press, 1984.

THE CULT OF ST NICHOLAS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN NORTH

243

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

Dietrichson, Larentz. Sammenlignede Fortegnelse over Norges Kirkebygninger i Middelalderen og

Nutiden

. Kristiania: P. T. Malling, 1888.

Franklin, Simon.

‘Kievan Rus’ (1015–1125)’. In The Cambridge History of Russia. Vol. 1, From

Early Rus

’ to 1689, ed. Maureen Perrie, 73–97. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2006.

Gassowsky, Jerzy.

‘Early Medieval Wisliza: Old and New Studies’. In Polish Lands at the Turn

of the First and the Second Millenia

, ed. Przemys

ław Urban´czyk, 341–56. Warsaw:

Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.

Gazeau, Véronique. Normannia monastica. 2 vols. Caen: Publications de CRAHM, 2008.

Gjerløw, Lilli, ed. Antiphonarium Nidrosiensis Ecclesiae. Libri Liturgici Provinciae Nidrosiensis

Medii Aevi, no. 3. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 1979.

Haki Antonsson.

‘Saints and Relics in Early Christian Scandinavia’. Mediaeval Scandinavia 15

(2005): 51

–80.

———. ‘Claims to Papal Canonizations of Saints in Scandinavia and Elsewhere’. Mediaeval

Scandinavia

19 (2009): 171

–204.

Haki Th. Antonsson, and Ildar H. Garipzanov, eds. Saints and Their Lives on the Periphery:

Veneration of Saints in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe (c. 1000

–1200). Cursor Mundi, no.

9. Turnhout: Brepols, 2010 (forthcoming).

Helle, Knut. Bergen bys historie. Vol. 1, Kongssete og kjøpstad fra opphavet til 1536. Bergen:

Universitetsforlaget, 1982.

Hollingsworth, Paul, ed. The Hagiography of Kievan Rus

’. Harvard Library of Early Ukrainian

Literature, no. 2. Cambridge, MA: Ukrainian Research Institute, 1992.

Jackson, Tatjana

‘The Cult of St Olaf and Early Novgorod’. In Saints and Their Lives on the Periphery:

Veneration of Saints in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe (c.1000

–1200), ed. Haki Th. Antonsson

and Ildar H. Garipzanov, Cursor Mundi, no. 9, 145

–66. Turnhout: Brepols, 2010.

Janin, V. L. Aktovyje pechati Drevnej Rusi X

–XV vv. Vol. 1. Moscow: Nauka, 1998.

Janin, V. L., and P. G. Gaidukov. Aktovyje pechati Drevnej Rusi X

–XV vv. Vol. 3. Moscow:

Intrada, 1998.

Jones, Charles W. The Saint Nicholas Liturgy and its Literary Relationships (Ninth to Twelfth

Centuries)

. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1963.

———. Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend. Chicago, IL:

University of Chicago Press, 1978.

Knýtlinga saga

. In Danakonungasögur: Skjöldunga saga, Knýtlinga saga, Ágrip af sögu danakon-

gunga

, ed. Bjarni Gu

ðnason, 91–321. Íslenzk fornrit, no. 35. Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka

fornritafélag, 1982.

Kócka-Krenz, Hanna, Michal Kara, and Daniel Makowiecki.

‘The Beginnings, Development

and the Character of the Early Piast Stronghold in Poznan

’. In Polish Lands at the Turn of

the First and the Second Millenia

, ed. Przemys

ław Urban´czyk, 125–66. Warsaw: Institute

of Archaeology and Ethnology, 2004.

Krins, Hubert. Die frühen Steinkirchen Danemarks. Hamburg: Universität Hamburg, 1968.

Lapidge, Michael, ed. Anglo-Saxon Litanies of the Saints. London: Henry Bradshaw Society,

1991.

Lazarev, V. N. Mozaiki Sofiji Kievskoj. Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1960.

——. Old Russian Murals & Mosaics from the XI to the XVI Century. London: Phaidon, 1966.

Loseva, O. V. Russkije mesiatseslovy XI

–XIV vekov. Moscow: Pamiatniki istoricheskoj mysli,

2001.

Magdalino, Paul.

‘Introduction’. In The Perception of the Past in 12th-century Europe, xi–xvi.

London: Hambledon, 1992.

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

244

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

Majeska, George. Russian Travelers to Constantinople in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries.

Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1984.

Medyntseva, A. A. Gramotnost

’ v drevnej Rusi: po pamiatnikam epigrafiki X – pervoj poloviny XIII

veka

. Moscow: Nauka, 2000.

Meisen, Karl. Nicholauskult und Nicholausbrauch im Abendlande: Eine kultgeographisch-

volkskundliche Untersuchung

. 1931. 2nd ed. Ed. Matthias Zender and Franz-Jozef

Heyen. Düsseldorf: Schwann, 1981.

Mezger, Werner. Sankt Nikolaus: Zwischen Kult und Klamauk: Zur Entstehung, Entwicklung und

Veränderung der Brauchformen um einen populären Heiligen

. Ostfildern: Schwabenverlag,

1993.

Michelsen, Vibeke, and Kjeld de Fine Licht, eds. Danmarks Kirker: Århus Amt. 3 vols.

Danmarks kirker, no. 16, 1

–3. Copenhagen: Nationalmuseet, 1968–76.

Nazarenko, A. V. Drevniaja Rus

’ na mezhdunarodnykh putiakh: Mezhdistsiplinarnye ocherki

kul

’turnykh, torgovykh, politicheskikh svjazej IX–XII vekov. Moscow: Jazyki russkoj kul’-

tury, 2001.

Novgoroskaja pervaja letopis

’ starshego i mladshego izvodov. Moscow: Akademija Nauk SSSR,

1950.

Nyberg, Tore. Monasticism in North-Western Europe, 800

–1200. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000.

Paner, Henryk.

‘The Spatial Development of Gdansk to the Beginning of the 14th Century:

The Origins of the Old and the Main Town

’. In Polish Lands at the Turn of the First and the

Second Millenia

, ed. Przemys

ław Urban´czyk, 15–32. Warsaw: Institute of Archaeology

and Ethnology, 2004.

Phelpstead, Carl.

‘Pilgrims, Missionaries and Martyrs: The Holy in Bede, Orkneyiga saga and

Knýtlinga saga

’. In The Making of Christian Myths in the Periphery of Latin Christendom (c. 1000–

1300)

, ed. Lars Bøje Mortensen, 53

–82. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum, 2005.

Philippart, Guy, and Michel Trogalet.

‘L’hagiographie latine du XI

e

siècle dans la longue

durée: données statistiques sur la production littéraire et sur l

’édition médiévale’. In

Latin Culture in the 11th Century: Proceedings of the Third International Conference on

Medieval Latin Studies, Cambridge, September 9

–12 1998, ed. Michael W. Herren,

C. J. McDonough, and Ross G. Arthur, vol. 1, 281

–301. Turnhout: Brepols, 2002.

Piltz, Elisabeth. Det levande Bysans. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur, 1997.

Povest

’ vremennykh let. In Biblioteka literatury drevnej Rusi. Vol. 1, XI–XII veka. Ed. D. S.

Likhachev, 62

–315. St Petersburg: Nauka, 2004.

Ros, Jonas. Staden, kyrkorna och den kyrkliga organisationen. Occasional Papers in Archaeology,

no. 30. Uppsala: Uppsala University, 2001.

Saxo Grammaticus. Gesta Danorum. Ed. Karsten Friis-Jensen and Peter Zeeberg. 2 vols.

Copenhagen: Det Danske Sprog- og Litteraturselskab & Gads Forlag, 2005.

The Saga of the Sons of Magnús

. In Snorri Sturlusson, Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway,

trans. Lee M. Hollander, 688

–714. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1964.

Senyk, Sophia. A History of the Church in Ukraine. Vol. 1, To the End of the Thirteenth Century.

Orientalia Christiana Analecta, no. 243. Rome: Pontificio Istituto Orientale, 1993.

Sevcenko, Nancy P. The Life of St Nicholas in Byzantine Art. Turin: Bottega d

’Erasmo, 1983.

Tesch, Sten.

‘Kungen, Kristus och Sigtuna – platsen där guld och människor möttes’. In Kult,

Guld och Makt

, ed. Ingemar Nordgren, 233

–57. Gothenburg: Kompendiet, 2007.

Treharne, E. M. The Old English Life of St Nicholas with the Old English Life of St Giles. Leeds

Texts and Monographs, new series, no. 15. Leeds: University of Leeds, 1997.

Uspenskij, Boris. Filologicheskije razyskanija v oblasti slavianskikh drevnostej. Moscow:

Iszdatel

’stvo MGU, 1982.

THE CULT OF ST NICHOLAS IN THE EARLY CHRISTIAN NORTH

245

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

Wikström, Anders.

‘Den svårfångande kronologin: Om gravstratigrafi och problem med

dateringen av Sigtunas tidigmedeltida kyrkor

’. Hikuin 33 (2006): 223–38.

Zalizniak, A. A. Drevnenovgorogskij dialect. 2nd rev. ed. Moscow: Jazyki slavianskoj kultury, 2004.

Ildar H. Garipzanov is Senior Researcher in Medieval History at the University of Bergen,

Norway; Kandidat of Historical Science (Kazan State University, 1991); MA in Medieval

Studies (Central European University, Budapest, 1998); and PhD in Medieval History

(Fordham University, New York, 2004). Among his recent publications are The Symbolic

Language of Authority in the Carolingian World (c. 751

–877) (Leiden: Brill, 2008), and ‘Frontier

Identities: Carolingian Frontier and the gens Danorum

’, in Franks, Northmen, and Slavs:

Identities and State Formation in Early Medieval Europe, ed. Ildar Garipzanov, Patrick Geary,

and Przemys

ław Urban´czyk, 113–42 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2008). Currently, he leads a

research project, entitled

‘The “Forging” of Christian Identity in the Northern Periphery

(c. 820

–1200)’, financed by the Norwegian Research Council. Address: Centre for Medieval

Studies, University of Bergen, PO Box 7800, 5020, Bergen, Norway. [email: ildar.

SCANDINAVIAN JOURNAL OF HISTORY

246

Downloaded by [Uniwersytet Warszawski] at 05:10 24 January 2014

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

The Gospel of St John in Relation to the Other Gospels esp that of St Luke A Course of Fourteen Lec

Antonsson, The cult of st Olafr

The Gospel of St Luke Ten Lectures given in Basle by Rudolf Steiner

Antigone Analysis of Greek Ideals in the Play

Analysis of Police Corruption In Depth Analysis of the Pro

Low Temperature Differential Stirling Engines(Lots Of Good References In The End)Bushendorf

86 1225 1236 Machinability of Martensitic Steels in Milling and the Role of Hardness

Formation of heartwood substances in the stemwood of Robinia

54 767 780 Numerical Models and Their Validity in the Prediction of Heat Checking in Die

Illiad, The Role of Greek Gods in the Novel

A Critique of Socrates Guilt in the Apology

Hippolytus Role of Greek Gods in the Euripedes' Play

Byrd, emergence of village life in the near east

THE IMPORTANCE OF SOIL ECOLOGY IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE

Catalogue of the Collection of Greek Coins In Gold, Silber, Electrum and Bronze

Chizzola GC analysis of essential oils in the rumen fluid after incubation of Thuja orientalis tw

Changes in the quality of bank credit in Poland 2010

The Grass Is Always Greener the Future of Legal Pot in the US

więcej podobnych podstron