from the association

Position of the American Dietetic Association:

Functional Foods

ABSTRACT

All foods are functional at some phys-

iological level, but it is the position of

the American Dietetic Association

(ADA) that functional foods that in-

clude whole foods and fortified, en-

riched, or enhanced foods have a po-

tentially beneficial effect on health

when consumed as part of a varied

diet on a regular basis, at effective

levels. ADA supports research to fur-

ther define the health benefits and

risks of individual functional foods

and their physiologically active com-

ponents. Health claims on food prod-

ucts,

including

functional

foods,

should be based on the significant sci-

entific agreement standard of evi-

dence and ADA supports label claims

based on such strong scientific sub-

stantiation. Food and nutrition pro-

fessionals will continue to work with

the food industry, allied health pro-

fessionals, the government, the scien-

tific community, and the media to en-

sure that the public has accurate

information

regarding

functional

foods and thus should continue to ed-

ucate themselves on this emerging

area of food and nutrition science.

Knowledge of the role of physiologi-

cally active food components, from

plant, animal, and microbial food

sources, has changed the role of diet

in health. Functional foods have

evolved as food and nutrition science

has advanced beyond the treatment

of deficiency syndromes to reduction

of disease risk and health promotion.

This position paper reviews the defi-

nition of functional foods, their regu-

lation, and the scientific evidence

supporting this evolving area of food

and nutrition. Foods can no longer be

evaluated only in terms of macronu-

trient

and

micronutrient

content

alone. Analyzing the content of other

physiologically

active

components

and evaluating their role in health

promotion will be necessary. The

availability of health-promoting func-

tional foods in the US diet has the

potential to help ensure a healthier

population. However, each functional

food should be evaluated on the basis

of scientific evidence to ensure appro-

priate integration into a varied diet.

J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:735-746.

POSITION STATEMENT

All foods are functional at some phys-

iological level, but it is the position of

the American Dietetic Association

(ADA) that functional foods that in-

clude whole foods and fortified, en-

riched, or enhanced foods have a po-

tentially beneficial effect on health

when consumed as part of a varied

diet on a regular basis, at effective

levels. ADA supports research to fur-

ther define the health benefits and

risks of individual functional foods

and their physiologically active com-

ponents. Health claims on food prod-

ucts,

including

functional

foods,

should be based on the significant sci-

entific agreement standard of evidence

and ADA supports label claims based

on such strong scientific substantia-

tion. Food and nutrition professionals

will continue to work with the food

industry, allied health professionals,

the government, the scientific commu-

nity, and the media to ensure that the

public has accurate information re-

garding functional foods and thus

should continue to educate themselves

on this emerging area of food and nu-

trition science.

F

unctional foods are an exciting

current trend in the food and nu-

trition field (

). However, the

term functional foods has no legal

meaning in the United States. It is

currently a marketing, rather than a

regulatory, idiom. The rapidly evolv-

ing trend of functional foods creates

significant new issues and opportuni-

ties for public health, especially in

providing reliable information. In

1753, Lind suggested in “A Treatise of

the Scurvy,” that limes might prevent

scurvy in British sailors. His recom-

mendations to the Royal Navy physi-

cian were not incorporated until ap-

proximately 40 years later, even

though some people continued to die

due to scurvy (

). Nutrition research

progressed slowly until the 1940s,

when many deficiency diseases and

the nutrients to “cure” them were the

central focus. During this golden age

of biochemistry, Nobel Prize winners

and others discovered nutrients that

were responsible for many life-threat-

ening medical conditions. Throughout

World War I and II, many potential

soldiers failed military physicals due

to protein and vitamin/mineral defi-

ciencies. The US government re-

sponded by establishing the first Rec-

ommended Dietary Allowances and

initiating a health era emphasizing

the

importance

of

nutrition

for

growth (especially protein) and devel-

opment. In the 1960s, the pendulum

swung to the other side, when exces-

sive (fat, cholesterol, sodium), and or

imbalanced (lack of calcium, dietary

fiber) nutrient intakes started to be

recognized as related to chronic dis-

eases such as heart disease, cancer,

diabetes, osteoporosis, diverticulosis,

and others. The US government be-

came involved again, but this time

with an emphasis on reducing fat and

increasing

complex

carbohydrates.

Twenty years later the focus shifted

toward essential and a few nonessen-

tial nutrients and their possible ben-

efit in treating disease, such as fiber;

vitamins A, C, and E; and the mineral

selenium in cancer chemoprevention.

An American cereal company collabo-

ration with the National Cancer In-

stitute to market a bran cereal as a

functional food broke new regulatory

ground and led to a radical change in

food labeling laws, including Food

0002-8223/09/10904-0018$36.00/0

doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.02.023

© 2009 by the American Dietetic Association

Journal of the AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION

735

and

Drug

Administration

(FDA)

health claims regulations (

Dietary supplement companies also

experienced rapid economic growth as

they promoted links between n-3

fatty acids and heart disease, lyco-

pene and prostate cancer, probiotics

and certain gastrointestinal condi-

tions, and other nutrient-health con-

nections. Functional food and dietary

supplement companies, focused on in-

creasing their profit margins, began

to collide with researchers calling for

scientific proof. Natural food stores

grew in such numbers and strength

that they began to spawn larger chain

stores that started competing with

mainstream grocery stores (

). In

1998, official recognition of the alter-

native proactive health path sup-

ported by functional foods was fur-

ther solidified by the formation of the

National Center for Complementary

and Alternative Medicine within the

National Institutes of Health, which

funded university-associated research

centers. The path of nutrition science

had come full circle back to the tenet

Hippocrates espoused more than 2,500

years ago: “Let food be thy medicine

and medicine be thy food.”

Registered dietitians (RDs) follow

in Hippocrates footsteps by recom-

mending food as medical nutrition

therapy (MNT) to treat myriad health

conditions and/or to maintain, re-

store, and optimize health. As a re-

sult, defining and utilizing functional

foods is an important component of

their practice. They are consumers’

bridge between evidence-based re-

search and optimal health. RDs will

continue working to update MNT in

terms of incorporating functional food

information into academic curricula

and

evidence-based

practice.

The

number of functional food products

will continue to expand. It is critical

that RDs understand how these foods

reach the marketplace and are pro-

moted. RDs must work to ensure that

all the necessary steps and regulatory

procedures are followed.

DEFINING FUNCTIONAL FOODS

What exactly is a functional food?

There is no FDA or universally ac-

cepted definition of this evolving

food category (

). Several working

definitions

used

by

professional

groups and marketers have been

proposed by various organizations

in several countries as outlined be-

low along with the American Die-

tetic Association’s (ADA’s) definition

of functional foods.

ADA’s Definition

As the largest organization of food

and nutrition professionals in the

United States, ADA classifies all

foods as functional at some physiolog-

ical level (

) because they provide nu-

trients or other substances that fur-

nish

energy,

sustain

growth,

or

maintain/repair vital processes. How-

ever, functional foods move beyond

necessity to provide additional health

benefits that may reduce disease risk

and/or promote optimal health. Func-

tional

foods

include

conventional

foods, modified foods (ie, fortified, en-

riched, or enhanced), medical foods,

and foods for special dietary use (

United States’ Definition

Functional foods are not officially rec-

ognized as a regulatory category by

the FDA in the United States. How-

ever, several organizations have pro-

posed definitions for this rapidly

growing food category, most notably

the International Food Information

Council (IFIC) and the Institute of

Food Technologists. The IFIC consid-

ers functional foods to include any

food or food component that may have

health benefits beyond basic nutrition

(

). Similarly, a recent Institute of

Food Technologists expert report (

defined functional foods as “foods and

food

components

that

provide

a

health benefit beyond basic nutrition

(for the intended population). These

substances provide essential nutri-

ents often beyond quantities neces-

sary for normal maintenance, growth,

and development, and/or other biolog-

ically active components that impart

health benefits or desirable physio-

logical effects.”

Canada’s Definition

Health Canada defines functional

foods as “similar in appearance to, or

may be, a conventional food, is con-

sumed as part of a usual diet, and is

demonstrated to have physiological

benefits and/or reduce the risk of

chronic disease beyond basic nutri-

tional functions” (

Europe’s Definition

The European Commission Concerted

Action on Functional Food Science in

Europe regards a food as functional if

it is satisfactorily demonstrated to af-

fect beneficially one or more target

functions in the body, beyond ade-

quate nutritional effects, in a way

that is relevant to either an improved

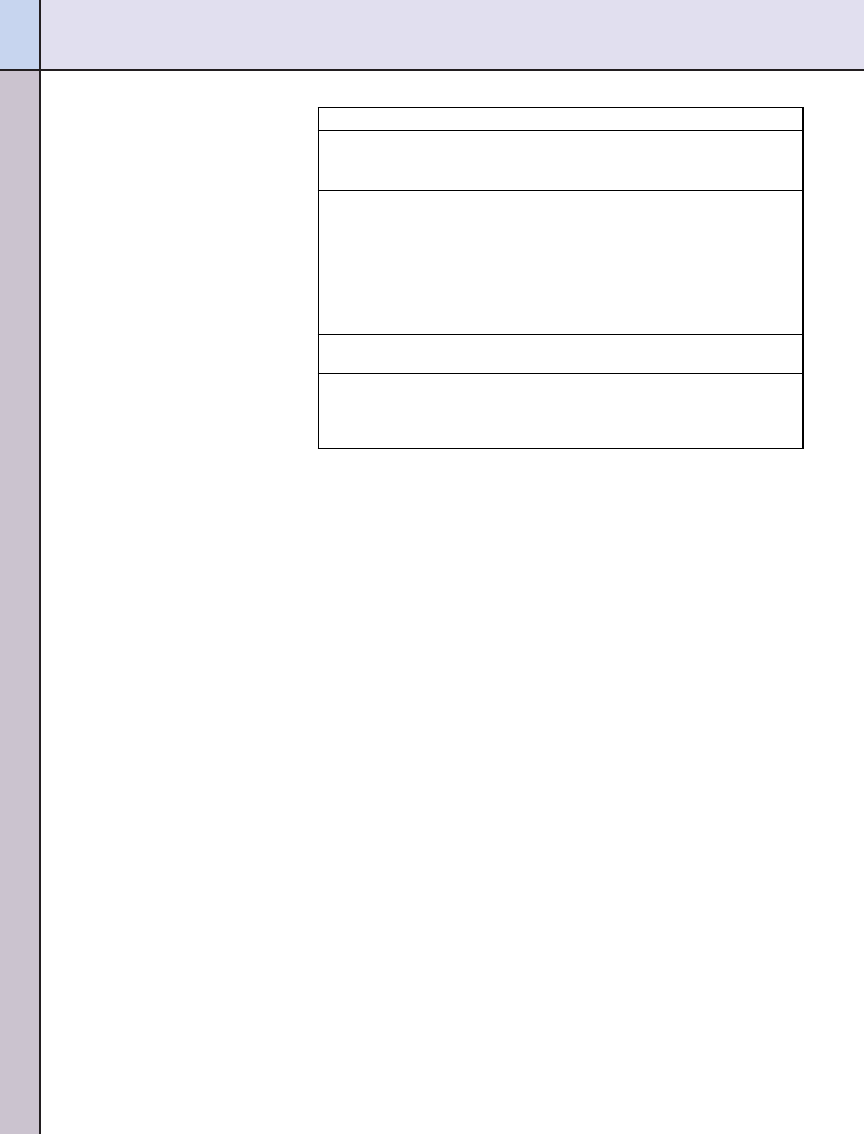

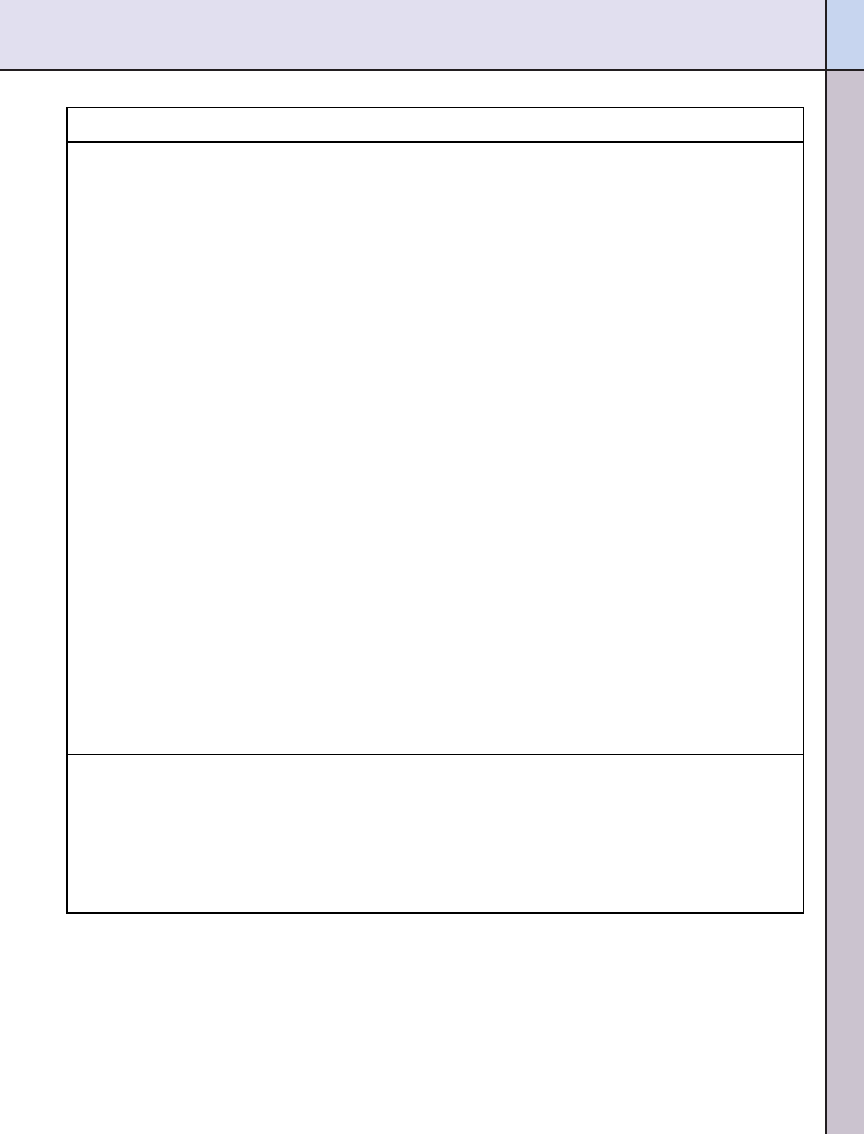

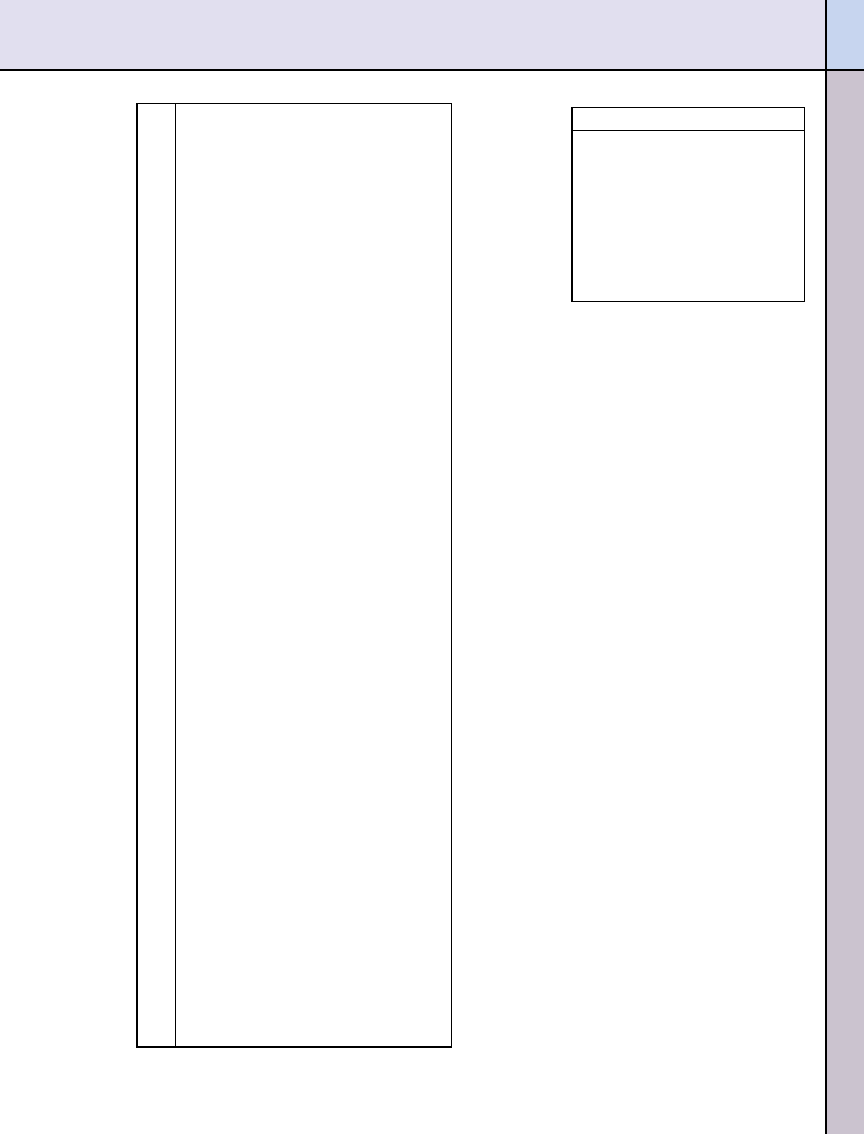

Functional food category

Selected functional food examples

Conventional foods (whole foods)

Garlic

Nuts

Tomatoes

Modified foods

Fortified

Calcium-fortified orange juice

Iodized salt

Enriched

Folate-enriched breads

Enhanced

Energy bars, snacks, yogurts, teas, bottled water,

and other functional foods formulated with

bioactive components such as lutein, fish oils,

ginkgo biloba, St John’s wort, saw palmetto,

and/or assorted amino acids

Medical foods

Phenylketonuria (PKU) formulas free of

phenylalanine

Foods for special dietary use

Infant foods

Hypoallergenic foods such as gluten-free foods,

lactose-free foods

Weight-loss foods

Figure 1. Functional food categories along with selected food examples.

736

April 2009 Volume 109 Number 4

state of health and well-being and/or

reduction of risk of disease. In this

context, functional foods are not pills

or capsules, but must remain foods

and they must demonstrate their ef-

fects in amounts that can normally be

expected to be consumed in the diet

(

Japan’s Definition

The functional food concept first de-

veloped in Japan in the late 1980s

when

the

Japanese

Ministry

of

Health and Welfare devised a regula-

tory framework for a category of foods

that provided specific health benefits,

clearly separating them from drugs.

Japan is the only country that recog-

nizes functional foods as a distinct

category, and the Japanese functional

food market is now one of the most

advanced in the world (

). Known as

Foods for Specified Health Use, these

are foods composed of functional in-

gredients that affect the structure

and/or function of the body and are

used to maintain or regulate specific

health conditions, such as gastroin-

testinal health, blood pressure, and

blood cholesterol levels (

Functional Foods vs Dietary Supplements

The Dietary Supplement Health and

Education Act of 1994 specifically de-

fines a dietary supplement as a spe-

cial category of food, but excludes any

product that is “represented for use as

a conventional food or as a sole item of

a meal or the diet” (

). In other

words, dietary supplements are le-

gally classified as foods, but not con-

sidered conventional foods consumed

in a diet such as a fruit or an entire

meal. ADA supports the FDA’s regu-

latory definition of dietary supple-

ments as foods, as long as they meet

the following criteria outlined in the

Dietary Supplement Health and Ed-

ucation Act: a product (other than to-

bacco) that is intended to supplement

the diet, which contains one or more

of

the

following

dietary

ingredi-

ents—a vitamin, a mineral, an herb

or other botanical, an amino acid, a

dietary substance to supplement the

diet by increasing the total daily in-

take, or a concentrate, metabolite,

constituent, extract, or combinations

of these ingredients; is ingested in

pill, capsule, tablet, or liquid form; is

not represented for use as a conven-

tional food or as the sole item of a

meal or diet; and is labeled as a “di-

etary supplement.”

One unofficial moniker for dietary

supplements in the United States is

“nutraceuticals.” Health Canada has

officially defined nutraceuticals as “a

product isolated or purified from

foods, and generally sold in medicinal

forms not usually associated with

food and demonstrated to have a

physiological benefit or provide pro-

tection against chronic disease” (

Functional Food Categories

In response to the increasing num-

bers of consumers interested in max-

imizing their health, the food indus-

try now offers an unprecedented

variety of new functional food prod-

ucts (

). The term functional food

should not be used to imply that there

are good foods and bad foods, but

rather that all foods can be incorpo-

rated into a healthful, varied diet.

The functional food categories defined

by ADA are now further explained:

Conventional Foods.

Unmodified whole

foods or conventional foods such as

fruits and vegetables represent the

simplest form of a functional food. For

example, tomatoes, raspberries, kale,

or broccoli are considered functional

foods because they are, respectively,

rich in such bioactive components as

lycopene, ellagic acid, lutein, and sul-

foraphane. Interestingly, the IFIC

2007 Consumer Attitudes Toward

Functional Foods/Foods for Health

survey found that fruits and vegeta-

bles were the top functional foods

identified by consumers (

). A few of

the many examples of emerging evi-

dence that links conventional foods to

health benefits include cancer risk re-

duction. Cruciferous vegetables re-

duced risk of several types of cancer

in experimental and epidemiologic

studies (

). Tomato products rich in

lycopene may reduce the risk of pros-

tate, ovarian, gastric, and pancreatic

cancers (

). Citrus fruit may reduce

the risk of stomach cancer (

). For

heart health, dark chocolate im-

proved endothelial function (

), and

tree nuts and peanuts reduce the risk

of sudden cardiac death (

). For in-

testinal

health

maintenance,

fer-

mented dairy products (probiotics)

may improve irritable bowel syn-

drome (

); and for urinary tract

function, cranberry juice reduced bac-

teriuria (

Modified Foods.

Functional foods can

also include those that have been

modified through fortification, enrich-

ment, or enhancement. These include

calcium-fortified

orange

juice

(for

bone health), folate-enriched breads

(for proper fetal development), or

foods enhanced with bioactive compo-

nents, such as margarines containing

plant stanol or sterol esters (for cho-

lesterol lowering), and beverages en-

hanced with energy-promoting ingre-

dients marketed to consumers such

as ginseng, guarana, or taurine. How-

ever, some of these beverages, as well

as various snacks containing such bo-

tanicals as St John’s wort, kava kava,

and echinacea, have been criticized

for making fraudulent medical claims

and safety concerns (

). As a result,

some commercially sold functional bo-

tanical products have been removed

from the market (

). Modifying foods

through biotechnology to improve

their nutritional value and health at-

tributes may also bring new func-

tional foods to the marketplace, such

as n-3 fatty acid enhanced or no-

trans-fat oils (

), although the topic

remains controversial.

Medical Foods.

The term medical food,

as defined by the Orphan Drug Act is

“a food which is formulated to be con-

sumed or administered enterally un-

der the supervision of a physician and

which is intended for the specific di-

etary management of a disease or

condition for which distinctive nutri-

tional requirements, based on recog-

nized scientific principles, are estab-

lished by medical evaluation” (

Examples of medical foods include

oral supplements in the form of phe-

nylketonuria formulas free of phenyl-

alanine, and diabetic, renal, and liver

formulations. Claims determine the

regulatory status of a product. For

example, a canned or bottled oral sup-

plement used under medical supervi-

sion, is a medical food; however, it

becomes a food for special dietary use

when sold to consumers at the retail

level.

Foods for Special Dietary Use.

The Fed-

eral Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

[Section 411(c)(3)] defines “special di-

etary use” as “a particular use for

which a food purports or is repre-

April 2009

● Journal of the AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION

737

sented to be used, including but not

limited to the following: 1. Supplying

a special dietary need that exists by

reason of a physical, physiological,

pathological, or other condition . . . ;

2. Supplying a vitamin, mineral, or

other ingredient for use by humans to

supplement the diet by increasing the

total dietary intake. 3. Supplying a

special dietary need by reason of be-

ing a food for use as the sole item of

the diet . . .” (

). Examples of such

foods include infant foods, hypoaller-

genic foods such as gluten-free foods

and lactose-free foods, and foods of-

fered for reducing weight.

FACTORS DRIVING THE GROWTH OF THE

FUNCTIONAL FOODS CATEGORY

The health and nutrition paradigm

has changed significantly during the

past 2 decades. Today, food is not

merely viewed as a vehicle for essen-

tial nutrients to ensure proper growth

and development, but as a route to

optimal wellness. According to IFIC,

85% of consumers agree that certain

foods have health benefits that may

reduce the risk of chronic disease or

other health concerns (

). This food

as medicine paradigm will continue to

be driven by several key factors, in-

cluding:

●

increased consumer interest in con-

trolling their own health;

●

demographics including increases

in elders and ethnic subpopula-

tions;

●

escalating health care costs;

●

highly competitive food market with

small profit margins;

●

advances in technology, such as bio-

technology and nutrigenomics;

●

changes in food regulations; and

●

evidence-based science linking diet

to chronic disease risk reduction.

It is well established that poor di-

etary practices are linked with the

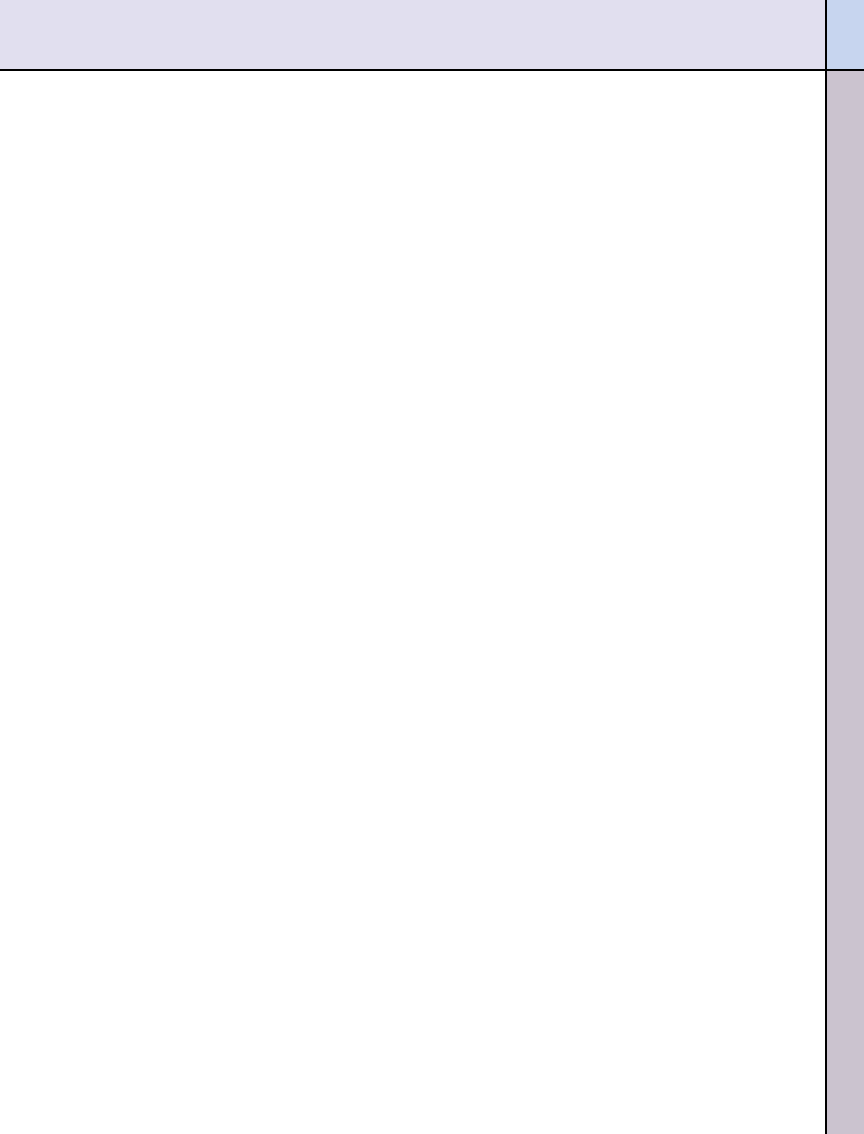

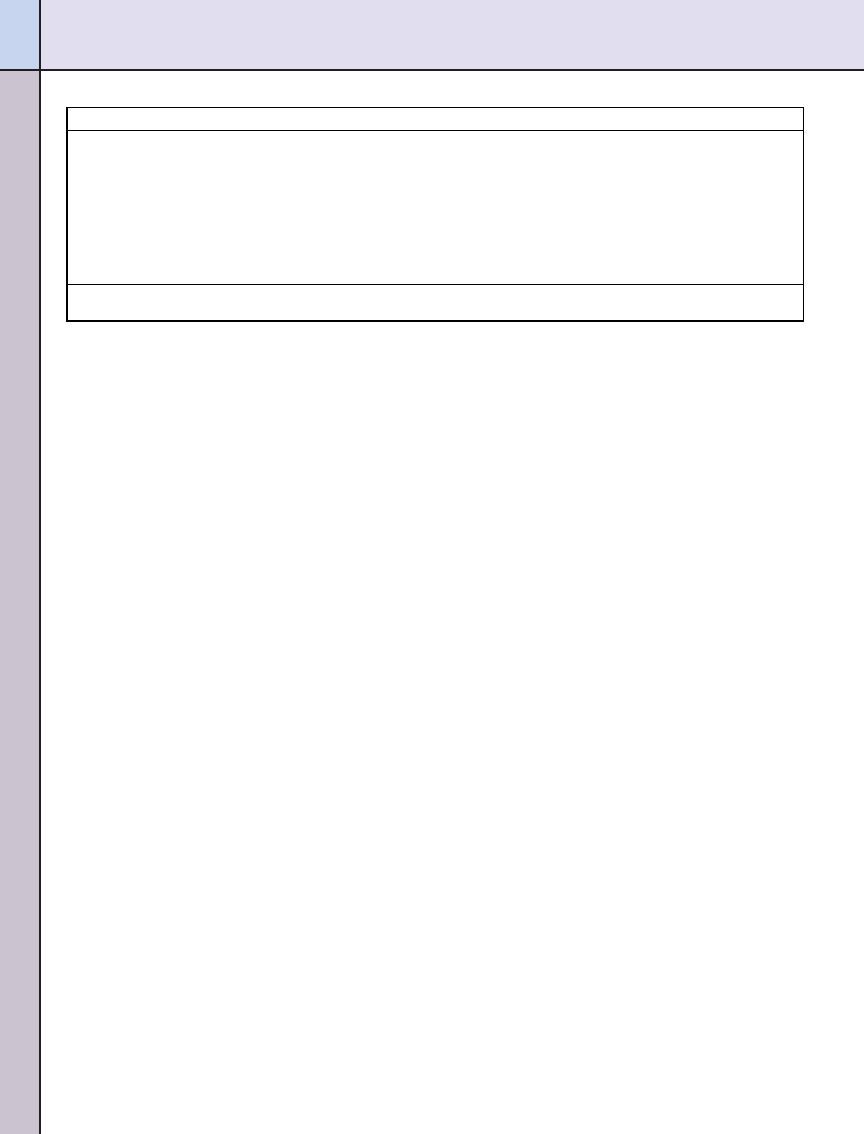

Figure 2. Schematic detailing how the Food and Drug Administration defines significant scientific agreement. Source:

738

April 2009 Volume 109 Number 4

major causes of morbidity and mortal-

ity, including cardiovascular disease,

hypertension, type 2 diabetes, over-

weight and obesity, and osteoporosis

(

). Certain types of cancer are also

strongly linked to diet as emphasized

in the second Expert Report from the

World Cancer Research Fund and the

American Institute for Cancer Re-

search: Food, Nutrition, Physical Ac-

tivity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A

Global Perspective (

). As the re-

search supporting the role of diet in

disease prevention and health promo-

tion continues to grow, the breadth

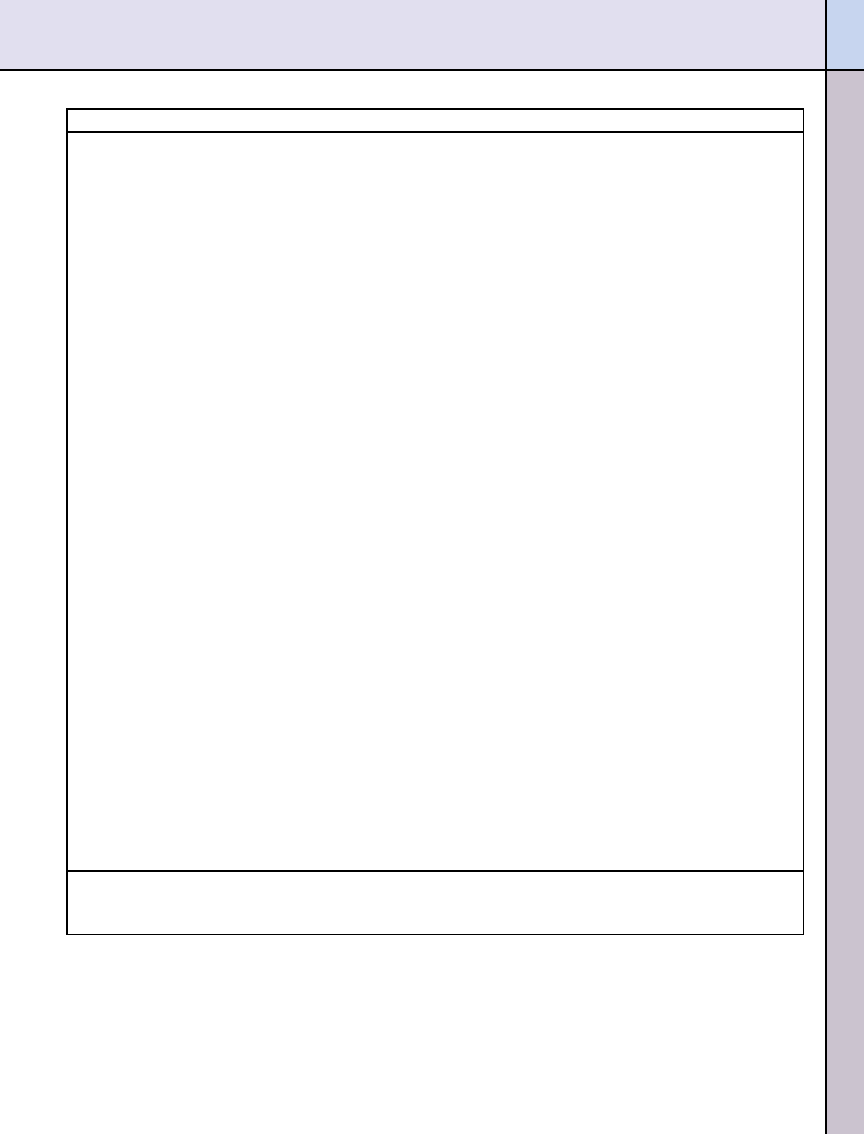

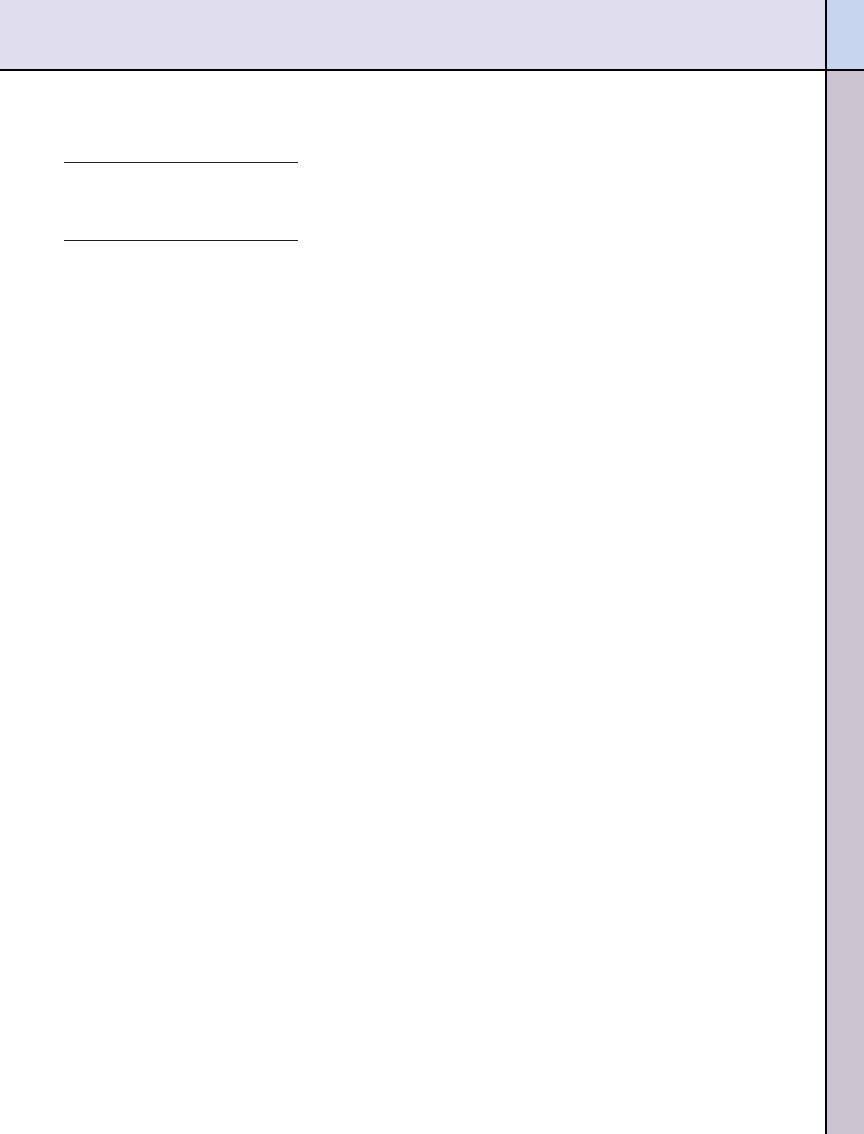

Dietary component

Disease

Petitioner

Clinical trial

support

Allowed health claim

Effective level

Sugar alcohols

Dental caries

NA

a

(in vivo

studies)

Frequent eating of foods high in sugars and

starches as between-meal snacks can

promote tooth decay. The sugar alcohol

[name of product] used to sweeten this

food may reduce the risk of dental

caries.

NA

Whole oat soluble

fiber

CHD

b

The Quaker Oats

Company

c

37 submitted

33 reviewed

d

17 priority

e

Diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol

that include soluble fiber from whole

oats may reduce the risk of heart

disease.

3 g/d; 0.75 g/serving

four times/d

Psyllium seed husk

soluble fiber

CHD

Kellogg Company

f

21 submitted

21 reviewed

17 priority

Soluble fiber from foods such as [name of

food], as part of a diet low in saturated

fat and cholesterol, may reduce the risk

of heart disease. A serving of [name of

food] supplies [x] grams of the soluble

fiber necessary per day to have this

effect.”

7g/d; 1.7 g/serving

four times/d

Oatrim

g

CHD

The Quaker Oats

Company

c

and

Rhodia, Inc

h

5 submitted

1 reviewed

Diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol

that include soluble fiber from Oatrim

may reduce the risk of heart disease.

0.75 g/serving

Barley soluble fiber

CHD

National Barley

Foods Council

11 submitted

5 reviewed

Soluble fiber from foods such as [name of

food], as part of a diet low in saturated

fat and cholesterol, may reduce the risk

of heart disease. A serving of [name of

food] supplies [x] grams of the soluble

fiber necessary per day to have this

effect.

3 g/d

Soy protein

CHD

Protein Technologies

International, Inc

i

43 submitted

41 reviewed

14 priority

Diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol

that include 25 g soy protein a day may

reduce the risk of heart disease. One

serving of [name of food] provides 6.25

g soy protein.

25 g/d; 6.25g/serving

Plant sterol esters

CHD

Lipton Tea Company

j

15 submitted

9 reviewed

8 priority

Plant sterols: Foods containing at least 0.65

g per serving of plant sterols, eaten

twice a day with meals for a daily total

intake of at least 1.3 g as part of a diet

low in saturated fat and cholesterol, may

reduce the risk of heart disease. A

serving of [name of food] supplies [x] g

vegetable oil sterol esters.

1.3 g/d; 0.65

g/serving

Plant stanol esters

CHD

McNeil Consumer

Healthcare

k

24 submitted

15 reviewed

14 priority

Plant stanol esters: Foods containing at

least 1.7 g per serving of plant stanol

esters, eaten twice a day with meals for

a total daily intake of at least 3.4 g, as

part of a diet low in saturated fat and

cholesterol, may reduce the risk of heart

disease. A serving of [name of food]

supplies [x] g plant stanol esters.

3.4 g/d; 1.7g/serving

a

NA

⫽not applicable.

b

CHD

⫽coronary heart disease.

c

Chicago, IL.

d

The FDA conducts its own independent review of the literature.

e

The FDA excludes studies that do not meet critical study design criteria.

f

Battle Creek, MI.

g

The soluble fraction of

␣-amylase hydrolyzed oat bran or whole oat flour.

h

Cranbury, NJ.

i

St Louis, MO.

j

Unilever USA, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

k

Johsohn&Johnson Services, Inc, New Brunswick, NJ.

Figure 3. Health claims authorized under the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) between 1997 and 2006 resulting from Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) review of industry or trade association petitions.

April 2009

● Journal of the AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION

739

and variety of functional foods on the

market will also increase. Consumers

interested in self-care and self-medi-

cation will increasingly seek diet-

based solutions to health and well-

ness. According to a recent IFIC

survey, 60% or more of Americans ei-

ther somewhat or strongly believe

that certain foods and beverages can

provide multiple health benefits and

more than 80% say they are currently

consuming or would be interested in

consuming foods and/or beverages for

such benefits (

Aging Baby Boomers will continue

to seek functional foods tailored for

specific health needs, including heart

disease, bone and joint health, cogni-

tive function, and eye health. This

personalized approach to nutrition

will become more feasible as the tech-

nology associated with nutrigenomics

continues to develop (

). In a recent

IFIC survey, more than two thirds

(71%) of Americans were favorable to-

ward the idea of using genetic infor-

mation to provide nutrition and/or di-

et-related

recommendations

Functional foods are viewed as one

option available to Americans seek-

ing cost-effective, preventative ap-

proaches to health care and im-

proved

health

status,

and

will

continue to transform the food sup-

ply of the 21st century.

REGULATION OF FUNCTIONAL FOODS IN

THE UNITED STATES

The boundaries between what is a

food and what is a medicine have

been challenged by both consumers

and manufacturers since the mid-

1980s. This has led to dramatic

changes in food regulations that have

fueled a so-called functional foods

revolution (

). The FDA has no spe-

cific definition for functional foods

and, unlike Japan, has no regulatory

framework for foods being marketed

as such. A functional food can be reg-

ulated as a conventional food, a food

additive, dietary supplement, drug,

medical food, or food for special di-

etary use depending on how the man-

ufacturer chooses to market the prod-

uct and, in particular, the type of

claims used on the package label or in

labeling. Thus, the regulation of func-

tional foods remains confusing and

has been criticized by a public advo-

cacy group (

). In response, in Octo-

ber 2006 the FDA announced a public

hearing to solicit information and

comments from interested persons on

how the FDA should regulate these

foods (

Three Claim Categories

There are currently three categories

of claims that food and dietary sup-

plement manufacturers can use on la-

bels to communicate health informa-

tion to consumers:

●

nutrient content claims;

●

structure/function claims; and

●

health claims.

Without question, most of the activ-

ity and controversy surrounding US

food regulations during the past 25

years has centered on health claims

(

), defined as statements that de-

scribe a relationship between a food

substance and a disease or other

health-related condition authorized

under the Nutrition Labeling and Ed-

ucation Act (NLEA) of 1990 (

The NLEA enables a product to

bear a health claim following the

FDA’s extensive review of the scien-

tific evidence summarized in petitions

submitted to the agency. Such claims

are authorized only if significant sci-

entific agreement exists among ex-

perts qualified to evaluate the totality

of the publicly available evidence re-

lated to the proposed claim. A scheme

outlining the significant scientific

agreement standard is shown in

Health claims must be authorized by

the FDA before they can be used on

food labels. Currently, health claims

that meet the significant scientific

agreement standard are allowed for 12

diet– disease relationship categories

(

). Substantial clinical efficacy is ab-

solutely essential for the approval of a

health claim under the NLEA.

More specifically, several well-de-

signed,

randomized,

placebo-con-

trolled intervention trials published

in

highly

regarded

peer-reviewed

journals are a critical component of a

health claim petition to the FDA. For

example, 11 clinical trials were in-

cluded in the petition submitted by

the National Barley Foods Council to

the FDA requesting a health claim

linking barley soluble fiber to reduced

risk of coronary heart disease (

). However, the FDA also conducts

its own rigorous review of the litera-

ture supporting a proposed health

claim when a petition is submitted. In

the case of the barley health claim,

the FDA excluded six of the 11 clinical

trials due to various design flaws (

Due to the strong scientific substanti-

ation required for health claims au-

thorized under the NLEA, ADA sup-

ports the use of such preauthorized

claims on food products, including

functional foods.

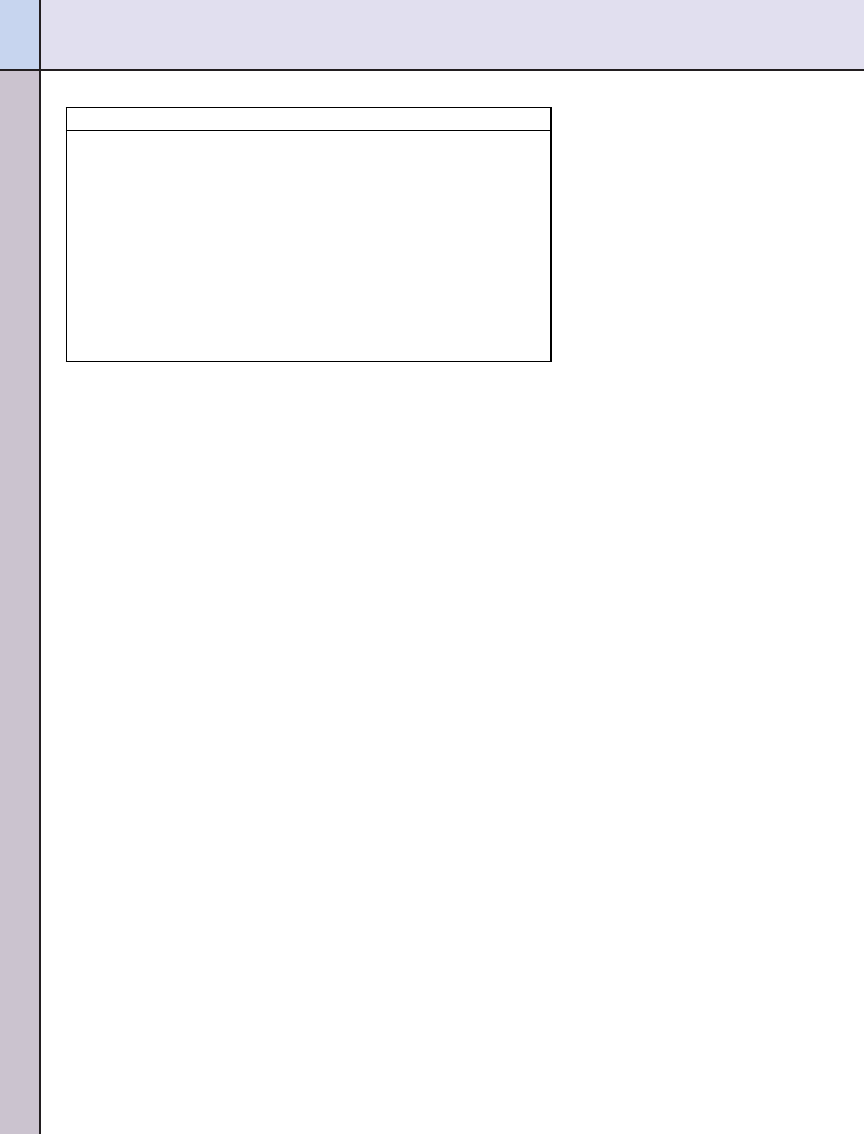

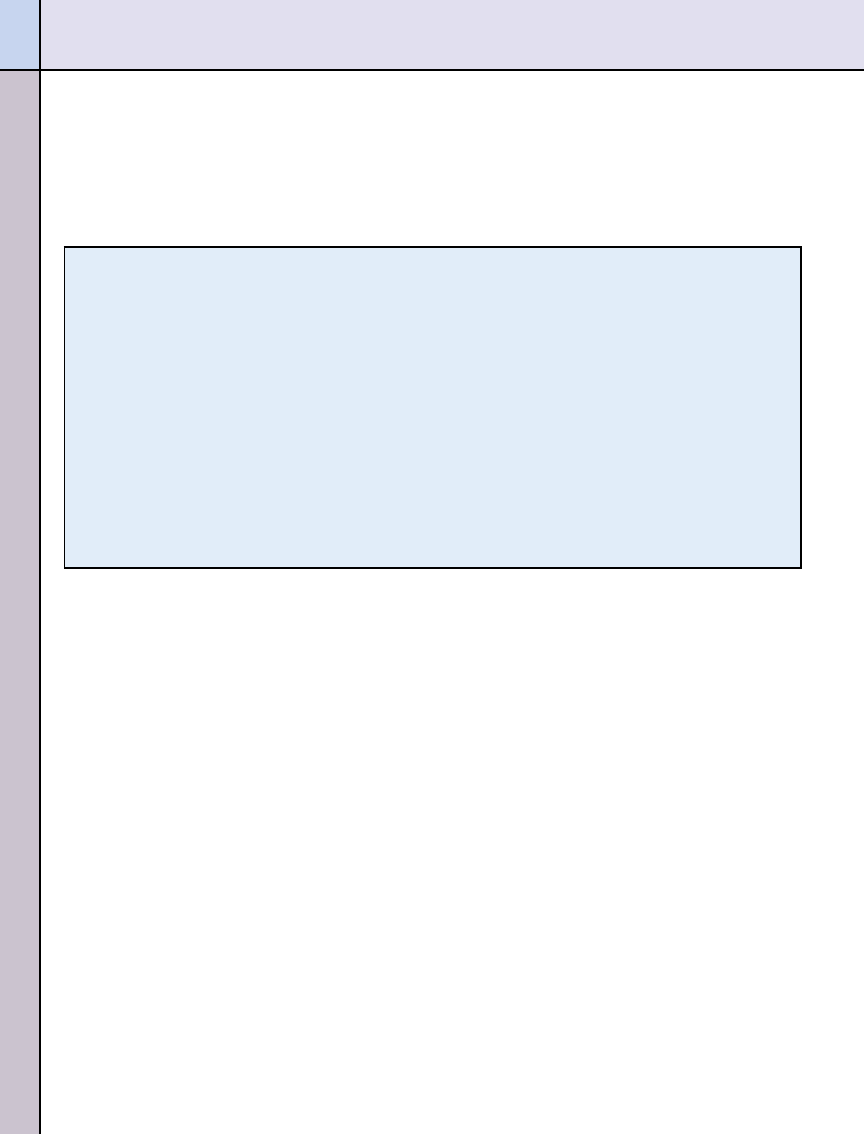

Scientific ranking

Level of scientific evidence

FDA

a

category

Proposed qualifying language

First level

High

A

Category A health claims are unqualified claims that meet

the current standard of significant scientific agreement

b

Second level

Moderate/good

B

“Scientific evidence suggests but does not prove . . .”

Third level

Low

C

“Some scientific evidence suggests . . . however; FDA has

determined that this evidence is limited and not

conclusive.”

Fourth level

Lowest

D

“Very limited and preliminary scientific research suggests . . .

FDA concludes that there is little scientific evidence

supporting this claim.”

a

FDA

⫽Food and Drug Administration.

b

Note that “significant scientific agreement” is equivalent to First Level, High, or FDA Category A.

Figure 4. Scientific ranking, level of scientific evidence, and proposed language for qualified health claims.

740

April 2009 Volume 109 Number 4

FDA can also authorize health

claims under the Food and Drug

Administration

Modernization

Act

(FDAMA) of 1997. Such claims are

based on current, published authori-

tative statements from “a scientific

body of the United States with official

responsibility for public health pro-

tection or research directly related to

human nutrition” such as the Na-

tional Institutes of Health, the Na-

tional Academy of Sciences, and the

Dietary component(s)

Qualifying source

Qualified health claim language

Claim level

Folic acid, vitamins

B-6 and B-12

Supplements containing vitamin

B-6, B-12, and/or folic acid

As part of a well-balanced diet that is low in saturated fat

and cholesterol, folic acid and vitamins B-6 and B-12

may reduce the risk of vascular disease. The FDA

a

evaluated the claim and found that, although it is

known that diets low in saturated fat and cholesterol

reduce the risk of heart disease and other vascular

diseases, the evidence in support of the above claim is

inconclusive.

B

Almonds, hazelnuts,

some pine nuts,

peanuts, pecans,

and pistachios

Whole or chopped nuts

Scientific evidence suggests but does not prove that

eating 1.5 oz/d of most nuts such as [name of specific

nut] as part of a diet low in saturated fat and

cholesterol may reduce the risk of heart disease. [See

nutrition information for fat content.]

B

Walnuts

Whole or chopped walnuts

Supportive but not conclusive research shows that eating

1.5 oz/d walnuts, as part of a low-saturated-fat and

low-cholesterol diet and not resulting in increased

energy intake, may reduce the risk of CHD

b

. See

nutrition information for fat [and energy] content.

B

n-3 fatty acids

Fish, other conventional foods,

and supplements

Supportive but not conclusive research shows that

consumption of EPA

c

and DHA

d

n-3 fatty acids may

reduce the risk of CHD. One serving of [name of the

food] provides [x] g EPA and DHA n-3 fatty acids. [See

nutrition information for total fat, saturated fat, and

cholesterol content.]

B

Monounsaturated fat

from olive oil

Salad dressings, vegetable oil,

olive oil-containing food, and

shortenings

Limited and not conclusive scientific evidence suggests

that eating about 2 T (23 g) olive oil daily may reduce

the risk of CHD due to the monounsaturated fat in olive

oil. To achieve this possible benefit, olive oil is to

replace a similar amount of saturated fat and not

increase the total amount of daily energy intake. One

serving of this product contains [x] g olive oil.

C

Unsaturated fatty acids

from canola oil

Canola oil, vegetable oil

spreads, dressings for

salads, shortenings, and

canola oil-containing foods

Limited and not conclusive scientific evidence suggests

that eating about 1

1

⁄

2

T (19 g) canola oil daily may

reduce the risk of CHD due to the unsaturated fat

content in canola oil. To achieve this possible benefit,

canola oil is to replace a similar amount of saturated

fat and not increase the total amount of daily energy

intake. One serving of this product contains [x] g

canola oil.

C

Corn oil and corn oil-

containing products

Very limited and preliminary scientific evidence suggests

that eating about 1 T (16 g) corn oil daily may reduce

the risk of heart disease due to the unsaturated fat

content in corn oil. The FDA concludes that there is

little scientific evidence supporting this claim. To

achieve this possible benefit, corn oil is to replace a

similar amount of saturated fat and not increase the

total amount of daily energy intake. One serving of this

product contains [x] g corn oil.

D

a

FDA

⫽Food and Drug Adminstration.

b

CHD

⫽coronary heart disease.

c

EPA

⫽eicosapentaenoic acid.

d

DHA

⫽docosahexaenoic acid.

Figure 5. Qualified health claims for cardiovascular disease in terms of dietary component, qualifying source, language, and claim level. B, C, and

D level claims correspond, respectively, to moderate, low, and lowest level of scientific evidence as outlined in

April 2009

● Journal of the AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION

741

Centers for Disease Control and Pre-

vention (

). FDAMA provisions are in-

tended to expedite the process by which

the scientific basis for such claims is

established. Currently, one nutrient

content claim and five health claims

have been approved under the FDAMA

(

). ADA was actively involved in dis-

cussions surrounding the passage of

the FDAMA and continues to support

the need for all claims, regardless of

whether they are authorized via the

NLEA process or the FDAMA notifica-

tion process, to be based on significant

scientific agreement.

The significant scientific agreement

standard of evidence required under

the NLEA was radically altered with

the Consumer Health Information for

Better Nutrition Initiative issued by

the FDA in July 2003 (

). This ini-

tiative was FDA’s response to the

1999 Pearson v Shalala court deci-

sion, which successfully challenged

the rigid standards of evidence ap-

plied to NLEA health claims (

This decision clarified the need to al-

low health claims based on less scien-

tific evidence as long as the claims do

not mislead the consumer. As part of

this initiative, the agency established

interim procedures whereby qualified

health claims can be made for dietary

supplements and conventional foods

(

). The body of data required for a

qualified health claim does not meet

the significant scientific agreement

standard; rather it must demon-

strate, based on the totality of infor-

mation available, that the weight of

the scientific evidence supports the

proposed

claim.

Qualified

health

claims are intended to provide infor-

mation about diet-disease relation-

ships to consumers even though the

scientific support has not reached the

highest level of scientific evidence

(

A primary objective of qualified

health claims is to benefit consumers

by providing more information on food

labels concerning diet and health. Un-

fortunately, recent evidence suggests

that consumers are unable to distin-

guish the different categories of claims.

A survey conducted by IFIC in 2004

showed that consumers have difficulty

distinguishing among four levels of sci-

entific evidence, especially with lan-

guage-only claims (

). In addition, the

survey found that consumers rate the

scientific evidence and other attributes

of a product containing an unqualified

claim similar to those products contain-

ing a structure-function claim or a di-

etary guidance statement.

Currently qualified health claims

are allowed for six disease categories:

cancer, cardiovascular disease, cogni-

tive function, diabetes, hypertension,

and neural tube defects. Qualified

health claims for cardiovascular dis-

ease are presented in

and

demonstrate the difference in qualify-

ing language among B-, C-, and D-

level claims. Qualified health claims

for other diseases are shown in

. More than two dozen qualified

health claim petitions have been de-

nied by FDA.

ADA strongly supports the signifi-

cant scientific agreement standard of

evidence and believes all claims made

on conventional foods and dietary

supplements should meet this stan-

dard. However, given FDA’s mandate

to allow qualified health claims, ADA

recommends an evidence-based rank-

ing system to facilitate a thorough re-

view of scientific data that supports

both qualified and unqualified health

claims, as well as mechanisms to com-

municate strength of evidence more

clearly to the public.

SCIENTIFIC SUBSTANTIATION

Functional foods differ with regard to

the quantity and quality of evidence-

based science supporting their pur-

ported health benefits. As a result,

consumers can be confused about

which products are truly beneficial.

The strength of evidence is based on

the current cumulative summary of

all studies and is weighted by their

number, quality, and type of which

only the latter will be discussed. The

FDA’s system of substantiation that

serves as a guide for the industry has

been previously described (

Types of Research

The type of research used to deter-

mine the level of evidence can range

from “soft” to “hard” science and var-

ies from: in vitro (in the test tube)

studies, in vivo (in the living) animal

studies, and in vivo human studies.

Human studies can be further subdi-

vided into subjective sensory evalua-

tions; epidemiologic studies; migra-

tion studies; observational; cohort

studies; and finally randomized, pla-

cebo-controlled clinical trials, which

are the gold standard. All studies are

strengthened by including a control,

using a single- or double-blind or

cross-over design, and validating the

bioactive being tested or evaluation

tool being utilized. A meta-analysis is

conducted when smaller studies are

pooled to increase their statistical

power. However, sometimes only cer-

tain studies in a meta-analysis meet

the qualifying criteria and not all

studies are homogeneous in treat-

ment or measurable outcomes. Ulti-

mately, the weight of the evidence ob-

tained through literature reviews

should be based on a sufficient num-

ber of clinical trials. This information

is then used to make claims commu-

nicating the functional food’s benefit

to consumers.

Disease

Food component(s)

Qualifying source

Prostate, ovarian, gastric, and

pancreatic cancers

Tomatoes

Cooked, raw, dry, or canned

tomatoes

Colorectal cancer and polyps

Calcium

Supplements

Breast and prostate cancers

Green tea

Green tea and supplements

containing green tea

Certain cancers

Selenium

Supplements

Certain cancers

Antioxidant vitamins

Supplements

Cognitive function and

dementia

Phosphatidylserine

Supplements

Insulin resistance

Chromium picolinate

Supplements

Essential and gestational

hypertension and

preeclampsia

Calcium

Supplements

Neural tube defects

Folic acid

Supplements

Figure 6. Qualified health claims for various diseases based on food components and their

qualifying sources.

742

April 2009 Volume 109 Number 4

Consistent Reporting Standards

Although randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled clinical studies

are the gold standard for determin-

ing efficacy, a person can potentially

compare results of multiple studies

involving functional foods when re-

searchers and/or the journal editors

ensure that a standard check list of

information is reported. Such infor-

mation would include, but is not

limited to subject (ie, type, number,

and age), use of a control, dosage

form (ie, pill, powder, plant part,

plant genus and species, liquid, or

solvent), standardized source (ie,

compositional verification via chro-

matographic analysis or some other

standardization test, including ge-

nus, species and variety/accession

for plants/herbs, or supplier identi-

fication),

frequency,

and/or

even

measurable outcomes dependent on

quantitative end points.

presents an example of a study with

thorough reporting of critical pa-

rameters (

). Measurable outcomes

must also relate to the hypotheses

proposed in the study design when

evaluating the efficacy of functional

foods. This is necessary to safeguard

the scientific advancement of com-

plementary and alternative medi-

cine. Comparison or duplication of

research results is not possible with-

out this critical information that

should be included in all publica-

tions, including abstracts.

Ideally, measurable outcomes or

end points for any research topic

should be standardized. Whenever

possible, researchers should choose

well-defined

bioactives

), biomarkers (often laboratory

Study

author,

year

Subjects

Design

Dosage

(substance,

form,

amount,

frequency)

Standardized

source

Duration

End

points

Jenkins

and

colleagues,

2008

(46)

27

healthy

men

and

postmenopausal

women

with

hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia

defined

as

elevated

low-density

lipoprotein

cholesterol

(⬎

158

mg/dL

[⬎

4.1

mmol/L])

Randomized

cross-over

design

(subjects

served

as

own

controls)

Each

1-mo

diet

phase

separated

by

a

minimum

2-wk

washout

period

Substance/form:

whole

raw

unblanched

almonds

daily

for

4

wk

in

the

form

of

muffins

Three

1-mo

diet

phases:

1)

Treatment

-

full

dose

almonds

in

muffins

(73

g/dL)

2)

Treatment

-

half-dose

almonds

in

muffins

(37

g/dL)

3)

Control.

No

almonds

in

muffins

Almond

source

(brand)

not

specified

1

mo

for

each

of

the

three

diet

phases

Total

serum

cholesterol

concentration

was

significantly

lower

in

half-

and

full-dose

almond

treatments

compared

to

controls

(P

⬍

0.05).

Serum

low-density

lipoprotein

cholesterol

was

lower

and

serum

high-density

lipoprotein

cholesterol

was

higher

in

full-dose

almond

group

compared

to

controls

(P

⬍

0.05).

Full

dose

almonds

reduced

serum

malondialdehyde

concentrations

(P

⫽

0.040)

and

creatinine-adjusted

urinary

isoprostane

output

(P

⫽

0.026).

No

significant

difference

occurred

in

serum

triglyceride

concentrations.

Figure

7.

Suggested

comprehensive

data

to

report

when

publishing

results

of

clinical

trials

on

functional

foods.

Bioactive ingredient

Lignans

Polyphenols

Anthocyanins

Ellagitannins

Flavonoids

Proanthocyanidins

Gallotannins

Phenolic acids

Stilbenoids

Triterpenoids

Figure 8. Selected classes of bioactives found

in berries, namely, blackberries, black raspber-

ries, blueberries, cranberries, red raspberries,

and strawberries. Data from reference

April 2009

● Journal of the AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION

743

tests such as serum cholesterol, blood

pressure, and prostate specific anti-

gen) or clinical endpoints (myocardial

infarction, bone fractures, tumors,

metastasis, overall survival, or polyp

size and number) to evaluate their

hypotheses (

). However, it is not

always feasible to evaluate all mea-

surable outcomes due to financial con-

straints that limit the type and

amount of data collection.

Another problem facing evidenced-

based research in the substantiation of

a functional food claim is that clear

cause and effect relationships are not

always easily deciphered in the com-

plex web of individual variability and

human physiology. Differences among

population subgroups further compli-

cate the identification of clear cause

and effect relationships. Increasingly,

evidence for functional foods is based

on well-designed clinical trials.

TAKE HOME MESSAGE FOR FOOD AND

NUTRITION PROFESSIONALS

The landscape of the food and nutri-

tion field changes constantly. Foods

are no longer solely viewed in terms of

macro- or micronutrients or even nu-

trient deficiencies or excesses. The

possibility of other potential health-

promoting components found in foods

has created a new wave of functional

food information that will continue to

expand.

Staying Informed

There are many ways for food and nu-

tritional professionals to keep well in-

formed about this growing field within

the food and nutrition arena. Recent

research can be accessed either directly

through PubMed or the Journal of the

American Dietetic Association’s re-

search abstracts in the back of each

issue called “New in Review,” reading

science-based books on the subject,

and/or the Daily News from ADA’s

Knowledge Center, which is “a daily

newsletter informing ADA members of

news affecting food, nutrition and

health.” (To get the Daily News via e-

mail each day, go to

). It may also be helpful to

stay current with functional food ad-

vancements in other countries. Other

avenues of staying connected include

joining the ADA’s Nutrition in Comple-

mentary Care dietetic practice group

where functional foods are part of their

scope. Additional resources for re-

search and/or regulations are the Na-

tional Center for Complementary and

Alternative Medicine, Natural Medi-

cines Comprehensive Database, Co-

chrane Reviews, and FDA.

MNT Client Education

Enhancing the health of the individ-

ual can occur by continuing to incor-

porate functional food information

into the current mainstream MNT

contained in ADA’s Nutrition Care

Manual. ADA’s Evidence Analysis Li-

brary (

is also a unique source of information

that will continue to be expanded. It

is the role of RDs and researchers to

search the literature and incorporate

solid evidence-based scientific sup-

port into the manual. RDs familiar

with the three current categories of

health claims can now start incorpo-

rating such foods into the diets of pa-

tients with certain medical conditions

and or optimizing the health of clients

interested in disease prevention and

health promotion.

Consumer Education

Consumers need to be advised on the

appropriate intake of functional foods

in the context of a healthful diet to

optimize their health. Their major

source of information on this topic

should be through RDs and dietetic

technicians, registered, knowledge-

able about functional foods.

Corporate Consulting

Food and nutritional professionals fa-

miliar with functional foods can con-

sult corporations on the latest or pos-

sible future trends in functional

foods. Working in research and devel-

opment departments will enable RDs

to be involved in the formation of new

functional foods that maximize the

potential health benefits to consum-

ers. Learning how a functional food

product is brought to market allows

RDs to do the same or assist both

small and large corporations starting

to enter the market.

Research

It is also the role of food and nutri-

tion professionals conducting re-

search to continue expanding the

knowledge base of functional foods

and/or complementary medicine to

provide high-quality evidence-based

research. Promoting a standardized

reporting method that includes sub-

ject type, study design (preferably

double-blind,

placebo-controlled),

dose (ie, source and amount), dura-

tion, and measurable outcomes or

endpoints is crucial. Research find-

ings then need to be translated into

practical information for both con-

sumers and clinicians.

Government Policy

Functional food regulation is para-

mount to public policy formation in-

volving foods that may optimize human

health. The role of RDs is to safeguard

the public by protecting the definition,

use, and regulation of functional foods.

Getting involved politically through

ADA and Congress is key to developing

and enhancing regulatory standards

for functional foods. Ensuring their

safety and making sure label claims

and marketing are based on scientifi-

cally sound data are critical.

The functional foods category is

just one aspect of complementary

medicine that is increasingly recog-

nized in the history of food and nutri-

tion as an advance toward optimizing

health. Food and nutritional profes-

sionals play important roles in edu-

cating new RDs, clients, consumers,

corporations, and public policy mak-

ers about functional foods and their

roles in human health.

CONCLUSIONS

In 1907 an editorial appeared in the

Journal of the American Medical Asso-

ciation calling for practicing physicians

“to give [e]special attention to the study

of dietetics so that he may appropriate

and put to practical use the latest de-

velopments of physiological research”

(

). One hundred years later, the

study of how diet impacts disease pre-

vention and health promotion is more

important than ever. Consumer inter-

est in the health benefits of foods and

food components is at an all time high

and will continue to grow. Food and

nutrition professionals are uniquely

qualified to interpret scientific findings

on functional foods and translate such

findings into practical dietary applica-

tions for consumers, other health pro-

fessionals, policy makers and the me-

dia. Food and nutrition professionals

744

April 2009 Volume 109 Number 4

must continue to be leaders in this ex-

citing and ever-evolving area of food

and nutrition.

The authors thank the reviewers for

their many constructive comments

and suggestions. The reviewers were

not asked to endorse this position or

the supporting paper.

References

1. Sloan AE. The top 10 functional food trends.

Food Technol. 2008;62:24-44.

2. Cook GC. Scurvy in the British Mercantile

Marine in the 19th century, and the contri-

bution of the Seamen’s Hospital Society.

Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:224-229.

3. Fulgoni V. Health claims: A US perspective.

In: Hasler CM, ed. Regulation of Functional

Foods and Nutraceuticals. Ames, IA: Black-

well Publishing; 2005:79-88.

4. Wrick KL. The impact of regulations on the

business of nutraceuticals in the United

States: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. In:

Hasler CM, ed. Regulation of Functional

Foods and Nutraceuticals. A Global Perspec-

tive. Ames, IA: Blackwell Publishing; 2005:

3-36.

5. Ross S. Functional foods: The Food and Drug

Administration perspective. Am J Clin Nutr.

2000;71(suppl):1735S-1738S.

6. Position of The American Dietetic Associa-

tion: Functional foods. J Am Diet Assoc.

2004;104:814-826.

7. International

Food

Information

Council.

Functional foods: Attitudinal research. Inter-

national Food Information Council Web site.

http://www.ific.org/research/funcfoodsres02.

cfm.

Accessed January 9, 2009.

8. Institute of Food Technologists. Functional

foods: Opportunities and challenges. Insti-

tute of Food Technologists Web site.

members.ift.org/IFT/Research/IFTExpert

Reports/functionalfoods_report.htm.

Ac-

cessed January 9, 2009.

9. Policy paper—Nutraceuticals/functional foods

and health claims on foods. Health Canada

Web site.

http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/fn-an/label-

etiquet/claims-reclam/nutra-funct_foods-nutra-

fonct_aliment-eng.php.

Accessed January 9,

2009.

10. European Commission Concerted Action on

Functional Food Science in Europe. Scien-

tific concepts of functional foods in Europe.

Consensus document. Br J Nutr. 1999;

81(suppl 1):S1-S27.

11. Yamaguchi P. Japan’s nutraceuticals today—

Functional foods Japan 2006. NPIcenter Web

site.

http://www.npicenter.com/anm/templates/

Accessed January 9, 2009.

12. Arai S, Morinaga Y, Yoshikawa T, Ichishi E,

Kiso Y, Yamazaki M, Morotomi M, Shimizu

M, Kuwata T, Kaminogawa S. Recent trends

in functional food science and the industry

in Japan. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;

66:2017-2029.

13. Dietary Supplement Health and Education

Act of 1994, 21 USC §321.

14. Hsieh YH, Ofori JA. Innovations in food

technology for health. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr.

2007;16(suppl 1):65-73.

15. Consumer attitudes toward functional foods/

foods for health—Executive summary. Inter-

national Food Information Council Web site.

http://www.ific.org/research/funcfoodsres07.

cfm.

Accessed January 9, 2009.

16. Moriarty, Naithani R, Surve B. Orgaosulfur

compounds in cancer chemoprevention. Mini

Rev Med Chem. 2007;7:827-838.

17. Kavanaugh CJ, Trumbo PR, Ellwood KC.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s

evidence-based review for qualified health

claims: Tomatoes, lycopene, and cancer.

J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1074-1085.

18. Bae J-M, Lee AJ, Guyatt G. Citrus fruit

intake and stomach cancer risk: A quantita-

tive systematic review. Gastric Cancer.

2008;11:23-32.

19. Faridi Z, Njike VY, Dutta S, Ali S, Katz DL.

Acute dark chocolate and cocoa ingestion

and endothelial function: A randomized con-

trolled crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;

88:58-63.

20. Kris-Etherton PM, Hu FB, Ros E, Sabate J.

The role of tree nuts and peanuts in the

prevention of coronary heart disease: Multi-

ple potential mechanisms. J Nutr. 2008;

138(suppl):1746S-1751S.

21. Quigley EM. Bacteria: A new player in

gastrointestinal motility disorders-infec-

tions, bacterial overgrowth, and probiotics.

Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;6:735-

748.

22. Nowack R. Cranberry juice—A well-charac-

terized folk-remedy against bacterial uri-

nary tract infection. Wien Med Wochenschr.

2007;157:325-330.

23. Center for Science in the Public Interest.

Functional food named in the Center for Sci-

ence in the Public Interest’s complaints to the

Food and Drug Administration. Center for Sci-

ence in the Public Interest Web site.

www.cspinet.org/reports/funcfoodcomplaint.

htm.

Accessed January 9, 2009.

24. Jacobson MF, Silverglade B, Heller IR.

Functional foods: Health boon or quackery?

West J Med. 2000;172:8-9.

25. Pew Initiative on Food and Biotechnology. Ap-

plication of biotechnology for functional foods.

Pew Charitable Trusts Web site.

pewagbiotech.org/research/functionalfoods/.

Accessed January 9, 2009.

26. Food and Drug Admnistration. Orphan

Drug Act (as amended).

Accessed January 9, 2009.

27. Tailoring your diet to fit your genes: A global

quest. International Food Information Council

Web site.

http://www.ific.org/foodinsight/2006/

Accessed January 9, 2009.

28. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005.

US Food and Drug Administration Web

site.

Accessed January 9, 2009.

29. World Cancer Research Fund, American

Institute for Cancer Research. Food, nutri-

tion, physical activity, and the prevention

of cancer: A global perspective. Diet and

Cancer

Report

Web

site.

Accessed

January 9, 2007.

30. 2008 Food and health survey: Consumer

attitudes

toward

food,

nutrition,

and

health. International Food Information

Council

Web

site.

research/foodandhealthsurvey.cfm.

Ac-

cessed January 15, 2009.

31. Fogg-Johnson N, Kaput J. Moving forward

with nutrigenomics. Food Technol. 2007;61:

50-57.

32. Heasman M, Mellentin J. The Functional

Foods Revolution: Healthy People, Healthy

Profits? London, UK: Earthscan Publi-

cations Ltd; 2001.

33. Citizen ptition 2002P-0122, petition for rule-

making on functional foods and request to

establish an advisory committee. Center for

Science in the Public Interest Web site.

www.cspinet.org/reports/funcgaopt_032102.pdf.

Accessed January 22, 2009.

34. Conventional foods being marketed as “func-

tional foods”; public hearing; request for

comments. Food and Drug Administration

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutri-

tion

Web

site.

Accessed January

9, 2009.

35. Taylor CL, Wilkening VL. How the nutrition

food label was developed, Part 2: The pur-

pose and promise of nutrition claims. J Am

Diet Assoc. 2008;108:618-623.

36. Nutrition Labeling and Education Act. USC

343(4)(3)(B)(i), implemented at 21 CFR

§101.14.

37. Label claims: Health claims that meet sig-

nificant scientific agreement. US Food and

Drug Administraiton Center for Food Safety

and Applied Nutrition Web site.

Ac-

cessed January 9, 2009.

38. Food labeling: Health claims; soluble dietary

fiber from certain foods and coronary heart

disease. US Food and Drug Administration

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutri-

tion

Web

site.

Accessed January 15,

2009.

39. Guidance for industry: Notification of a

health claim or nutrient content claim based

on an authoritative statement of a scientific

body. US Food and Drug Administration

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutri-

tion

Web

site.

Accessed January 9,

2009.

40. Label claims: FDA Modernization Act of

1997 (FDAMA) claims. US Food and Drug

Administration Center for Food Safety and

Applied Nutrition Web site.

Ac-

cessed January 9, 2009.

41. Consumer Health Information for Better Nu-

trition Initiative. Task force final report. US

Food and Drug Administration Center for

Food Safety and Applied Nutrition Web site.

Accessed January 9, 2009.

42. Pearson v Shalala. Bureau of National Af-

fairs

Web

site.

Accessed January

9, 2009.

43. Consumer Health Information for Better

Nutrition Initiative: Task force final report:

Attachment E—Interim procedures for qual-

ified health claims guidance: Interim proce-

dures for qualified health claims in the la-

beling of conventional human food and

human dietary supplements. US Food and

Drug Administration Center for Food Safety

and Applied Nutrition Web site.

Ac-

cessed November 5, 2008.

44. Qualified health claims consumer research

project executive summary. International

Food Information Council Foundation Web

site.

http://www.ific.org/research/qualhealth

Accessed January 9, 2009.

45. Guidance for industry and FDA: Interim ev-

idence-based ranking system for scientific

data. US Food and Drug Administration

April 2009

● Journal of the AMERICAN DIETETIC ASSOCIATION

745

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutri-

tion

Web

site.

Accessed January 9,

2009.

46. Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Marchie A, Josse

AR, Nguyen TH, Faulkner DA, Lapsley KG,

Blumberg J. Almonds reduce biomarkers of

lipid peroxidation in older hyperlipidemic

subjects. J Nutr. 2008;138:908-913.

47. Seeram NP. Berry fruits for cancer preven-

tion: Current status and future prospects. J

Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:630-635.

48. Weber P, Fluhmann B, Eggersdorfer M. De-

velopment of bioactive substances for func-

tional foods—Scientific and other aspects.

In: Heinrich M, Muller WE, Galli C, eds.

Local

Mediterranean

Food

Plants

and

Nutraceuticals (Forum of Nutrition). Vol 59.

Basel, Switzerland: Karger; 2006:171-181.

49. Anonymous. Diet and health. J Am Med As-

soc. 1907;198:2687.

ADA Position adopted by the House of Delegates Leadership Team October 16, 1994 and reaffirmed on September

7, 1997; June 15, 2001; and June 11, 2006. This position is in effect until December 31, 2012. ADA authorizes

republication of the position, in its entirety, provided full and proper credit is given. Readers may copy and distribute

this paper, providing such distribution is not used to indicate an endorsement of product or service. Commercial

distribution is not permitted without the permission of ADA. Requests to use portions of the position must be

directed to ADA headquarters at 800/877-1600, ext 4835, or

Authors: Clare M. Hasler, PhD, MBA (Robert Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science, University of

California, Davis); Amy C. Brown, PhD, RD (Department of Complementary and Alternative Medicine, John A

Burns School of Medicine, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu).

Reviewers: Sharon Denny, MS, RD (ADA Knowledge Center, Chicago, IL); Mary H. Hager, PhD, RD, FADA (ADA

Government Relations, Washington, DC); Oncology dietetic practice group (Kathryn Keifer Hamilton, MA, RD,

Morristown Memorial Hospital, Morristown, NJ); Andrea Hutchins, PhD, RD (University of Colorado at Colorado

Springs, CO); Rosalyn Franta Kulik, MS, RD, FADA (Rosalyn Franta Kulik Consulting, Tampa, FL); Esther Myers,

PhD, RD, FADA (ADA Scientific Affairs, Chicago, IL); Leila Saldanha, PhD, RD, (President, NutrIQ LLC, Alexan-

dria, VA); Research dietetic practice group (Kim S. Stote, PhD, MPH, RD, State University of New York, College at

Oneonta, Oneonta, NY); Jennifer A. Weber, MPH, RD (ADA Government Relations, Washington, DC); Robert

Wildman, PhD, RD (Demeter Consultants LLC, Pittsburgh PA, and Kansas State University, Manhattan). Associ-

ation Positions Committee Workgroup: Helen W. Lane, PhD, RD (chair); Debe Nagy-Nero, MS, RD; Suzanne

Hendrich, PhD (content advisor).

746

April 2009 Volume 109 Number 4

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Ground green coffee beans as a functional food

L 3 Complex functions and Polynomials

3 ABAP 4 6 Basic Functions

Aging skin and food suplements Nieznany (2)

Functional Origins of Religious Concepts Ontological and Strategic Selection in Evolved Minds

Applications and opportunities for ultrasound assisted extraction in the food industry — A review

MEDC17 Special Function Manual

FOOD AND DRINKS, SŁOWNICTWO

Verb form and function

Food ćwiczenia angielski Starland 1 module 8

food

dpf doctor diagnostic tool for diesel cars function list

Euler’s function and Euler’s Theorem

Attitudes toward Affirmative Action as a Function of Racial ,,,

nutritional modulation of immune function

moto suzuki motorbike scanner with bluetooth function list

NMR in Food

Changes in passive ankle stiffness and its effects on gait function in

Functional improvements desired by patients before and in the first year after total hip arthroplast

więcej podobnych podstron