Identity and Adolescent Adjustment

Laura Ferrer-Wreder

Barry University

Aleksandra Palchuk

University of California, Davis

Senel Poyrazli

The Pennsylvania State University

Meg L. Small and Celene E. Domitrovich

The Pennsylvania State University

This article is the report of an investigation of relations among identity coherence/

identity confusion, the ego strength of competence, antisocial behavior, academic

competence, and perceptions of school environment in a sample of 574 adolescents.

The primary results of this cross-sectional study suggest significant associations be-

tween identity-related constructs and indicators of adolescent adjustment. Study im-

plications are discussed in terms of identity-related interventions.

Identity development involves making sense of, and coming to terms with, the per-

sonal and social worlds one inhabits, recognizing choices and making decisions

within contexts, and finding a sense of unity within one’s self while claiming a

place in the world (Erikson, 1968). A positive or mature identity is one that is

self-selected, unified, competent, and, in a civil society, prosocial. A prolonged

negative or immature identity leaves a young person not optimally prepared for the

future.

Rosenthal, Gurney, and Moore (1981) developed the Erikson Psychosocial

Stage Inventory (EPSI) to measure a global “sense of identity.” The EPSI identity

Identity: An International Journal of Theory

and Research, 8:95–105, 2008

Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 1528-3488 print/1532-706X online

DOI: 10.1080/15283480801938143

Correspondence should be addressed to Laura Ferrer-Wreder, Barry University, Department of

Psychology, 11300 N.E. 2nd Avenue, Miami Shores, FL 33161–6695. E-mail: lwreder@mail.barry.edu

subscale, which is of particular interest in the present study, offers a snapshot of

where a person perceives he or she is in terms of identity coherence/identity confu-

sion. Identity coherence is defined in this study as “a workable and internally con-

sistent sense of identity” (Schwartz, Pantin, Prado, Sullivan, & Szapocznik, 2005,

p. 394) and identity confusion is defined as a lack of clarity regarding who one is,

including roles and belief systems (see Schwartz, Mason, Pantin, & Szapocznik,

this issue).

In this study, we viewed identity coherence/identity confusion as a single di-

mension, with identity coherence and confusion at opposing ends of this dimen-

sion (e.g., Gray, Ispa, & Thornberg, 1986; Morrison, Ispa, & Thornburg, 1994).

There is disparate empirical evidence regarding the most appropriate factor struc-

ture for the EPSI identity scale (c.f., Gray et al., 1986; Morrison et al., 1994;

Schwartz et al., 2005). Because this is an empirical question, other conceptualiza-

tions of this construct may be appropriate (see Schwartz et al., this issue).

Erikson (1968) and contemporary identity researchers have placed consider-

able value on the benefits of going through a process that results in (at least tempo-

rary) the successful resolution of one’s identity crisis. The extant research litera-

ture, although small with regard to identity coherence/identity confusion as

measured by the EPSI, generally has supported this theoretical stance (e.g., Moore

& Boldero, 1991; Rosenthal, Moore, & Taylor, 1983).

Focusing more closely on the specific indicators of adjustment in the present

study, significant relations have been found in cross-sectional studies between

identity coherence/identity confusion and adolescent behavior problems. For ex-

ample, youth (predominately White early adolescents living in urban, economi-

cally disadvantaged communities) with a well-developed identity were more likely

to have a lower level of self-reported delinquent behavior than youth with a rela-

tively less developed identity (De Haan & MacDermid, 1999). A parallel associa-

tion was demonstrated in a study by Arehart and Smith (1990) who found that, in

comparison to a mainstream, ethnically diverse sample of secondary school stu-

dents, youth detained for delinquent behavior were less likely to have resolved

their psychosocial crises. Another cross-sectional study with a sample of predomi-

nately Hispanic immigrant early adolescents living in urban economically disad-

vantaged communities showed significant associations, in theoretically expected

directions, between identity confusion/identity coherence and behavior problems

(Schwartz et al., 2005).

Examining an even wider array of adolescent adjustment indicators, a handful

studies have dealt with links between identity coherence/identity confusion and

academic achievement, substance use, and sexual behavior. Results from the

aforementioned De Haan and MacDermid (1999) study indicated a significant

positive relation between identity coherence and self-reported grades. Notably, no

significant association was found between the study’s identity indices and self-re-

ported substance use (De Haan & MacDermid).

96

FERRER-WREDER ET AL.

In one of the few, if not only, longitudinal studies on the subject, Schwartz et al.

(this issue) found that as identity confusion increased over time so did the proba-

bility of cigarette and alcohol use and sexual behavior. In this study, a group of

early adolescents, who were predominately Hispanic immigrants living in urban

economically disadvantaged communities, were followed for three years. As in a

previous cross-sectional study (Schwartz et al., 2005), identity confusion was

found to partially mediate the relation between family functioning and adjustment.

In this study, we sought to illuminate the associations between identity coher-

ence/identity confusion and several indices of adolescent adjustment. We sought to

do so in an ethnically diverse sample of adolescents that included high school-aged

adolescents, thereby expanding the extant identity development literature and add-

ing to the evidence base for identity-related intervention efforts (see Archer, p. 89,

this issue; Kurtines & Montgomery, 2008). Ethnicity was not included in the study

hypotheses and analyses because the ethnic composition of the sample was pre-

dominately African American (70%) with too few participants in other ethnic

groups for contrast analyses with sufficient statistical power.

Primary hypotheses in this study were as follows: Participants with low re-

ported levels of antisocial behavior would be characterized by greater identity co-

herence, relative to those who reported higher levels of antisocial behavior (e.g.,

Arehart & Smith, 1990; De Haan & MacDermid, 1999; Schwartz et al., 2005).

Low academic competence would be associated with low identity coherence (e.g.,

De Haan & MacDermid, 1999).

An ancillary hypothesis was that low levels of the ego strength of competence

would be associated with low identity coherence because the successful resolution

of psychosocial crisis is thought to give rise to ego strengths (Erikson, 1968). The

resolution of the psychosocial, industry, and inferiority crisis in school-aged youth

establishes the ego strength of competence as the basis for mastery and skills de-

velopment and better prepares a person to successfully address his or her identity

crisis (Markstrom, Sabino, Turner, & Berman, 1997). The ego strength of compe-

tence was defined in the present study as a young person’s global evaluation of his

or her own abilities. We could not locate a published study that examined how the

ego strength of competence relates to identity coherence/identity confusion as

measured by the EPSI. We therefore felt it worthwhile to examine whether compe-

tence does indeed relate to the resolution of identity crises in expected ways.

An ancillary research question concerned possible relations between adoles-

cents’ perception of the school environment and identity coherence/identity confu-

sion and the ego strength of competence. Perception of the school environment

was defined as a construct consisting of adolescents’ views on student and teacher

respect, school quality, and students’ sense of belongingness and engagement in

their school (Mitra, 2004). Although we could not locate a published study that ex-

amined the specific relation between these constructs, we felt that this was a key

research question because of the importance of school for adolescents.

IDENTITY AND ADOLESCENT ADJUSTMENT

97

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

Over the course of three years, 6th- through 12th-grade students in an urban school

district in the northeastern United States participated annually in a student survey.

Students completed a confidential paper-and-pencil survey in either their

homeroom or English classroom, taking approximately one hour. Institutional re-

view board approval and a certificate of confidentiality were obtained for these

survey administrations. Across the three years of survey administrations, annual

participation, on average, involved 2,791 students who received parental or guard-

ian consent, assented to participate, and returned a survey (i.e., 71% average re-

sponse rate).

The analyses conducted in the present study center on two cohorts of 11th grad-

ers (N = 574) with the following demographics. The percentage of boys in the sam-

ple was 47% (n = 270) and the percentage of girls was 52% (n = 296; 1% missing, n

= 8). The average age was 16.5 years, with participants ranging in age from 15 to

19 years old. The sample was predominately African American/Black (70%, n =

399) and Latino/Hispanic (12%, n = 69), with the remainder of the sample endors-

ing one of the following ethnic identifiers: American Indian/Native American,

Asian, White/Non-Latino, or Other (16%, n = 95; 2% missing, n = 11).

Measures

Demographic survey.

Participants were asked to provide information on

their gender, age, grade, and ethnicity.

Identity.

The EPSI (Rosenthal et al., 1981) is a 72-item self-report question-

naire rated on a 5-point Likert scale. For the purposes of this study, only the iden-

tity subscale was used. On this subscale, six items are indicative of identity coher-

ence and six items represent identity confusion. A sample item for coherence is “I

know what kind of person I am”; for confusion, “I feel mixed up.” Response op-

tions ranged on a Likert scale from 1 (hardly ever true) to 5 (almost always true).

Identity confusion items were reverse coded. The total identity score (TOT-I) con-

sisted of the average of 12 items, with higher scores denoting greater identity co-

herence. The Cronbach alpha reliability coefficient for TOT-I in this sample

was .74.

Ego strength of competence.

A subscale of the Psychological Inventory

of Ego Strengths (PIES; Markstrom et al., 1997) was used to measure the ego

strength of competence. A sample item is the following: “I have strengths that help

me to be effective in certain situations.” Response options ranged on a Likert scale

98

FERRER-WREDER ET AL.

from 1 (not descriptive of me) to 5 (very descriptive of me). The total ego strength

of competence score (TOT-ES) was comprised of the average of eight questions,

with higher scores indicating lower ego strength of competence. The Cronbach al-

pha reliability coefficient for the TOT-ES in the present sample was .68.

Antisocial behavior.

The Communities That Care Youth Survey (CTC Sur-

vey; Arthur, Pollard, Catalano, & Baglioni, 2002) taps into 19 validated indicators

of risk and 11 validated indicators of protective factors. For this study, 12 items

were selected from the CTC Survey’s scales and averaged to provide an overall in-

dex of students’ self-reported antisocial behavior. A sample item is the following:

“How many times in the past year (12 months) have you: been arrested?” Response

options ranged on a Likert scale from 0 (never) to 8 (40 or more times). Higher

scores indicated more antisocial behavior. The Cronbach alpha reliability coeffi-

cient for this subscale in the study sample was .85.

Academic competence.

The academic competence scale (derived from

Chen, Anthony, & Crum, 1999; Harter, 1982) is a six-item questionnaire rated on a

4-point Likert scale, with response options differing across items. A sample item is

the following: “Some people finish their schoolwork very quickly. Others take a

long time to finish. Do you finish your schoolwork: ‘very quickly,’ ‘pretty quickly,’

‘a bit slowly,’ or ‘very slowly’?” The total academic competence score (TOT-AC)

represents the average of the six items, with higher scores denoting lower aca-

demic competence. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient for the TOT-AC in the

present sample was .58.

Perceptions of school environment.

Four subscales from the Student

Voice Survey (Mitra, 2004) were used to measure participants’ perceptions of their

school environment. The items (e.g., “students help to make important school de-

cisions”; “this school is always trying to improve”) were answered with a Likert

scale, ranging from 0 (disagree a lot) to 3 (agree a lot). The total school environ-

ment score (TOT-ENV) represents the average of four subscales, with higher

scores indicating more favorable perceptions of the school environment.

Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for these subscales in this study sample

ranged from .56 to .78.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Dummy coding.

Adolescent responses to the CTC Survey’s antisocial be-

havior subscale have been characterized by limited variability in past statewide ad-

IDENTITY AND ADOLESCENT ADJUSTMENT

99

ministrations of this instrument. Therefore, we conceptualized antisocial behavior

(Ab) as a categorical, dummy variable created by using a dummy coding proce-

dure. Participants with less than .49 average antisocial behaviors were classified as

reporting low levels of Ab and those with .5 and higher average reported antisocial

acts were considered as reporting elevated levels of Ab.

Outliers.

Using non-model-based techniques, data for the continuous vari-

ables were evaluated for multivariate outliers by examining leverage indices for

each individual and defining an outlier as a leverage score four times greater than

the mean leverage score. Seven outliers were detected. There were no coding er-

rors and the outliers proved to be inconsequential for the analysis. All major con-

clusions remained intact when they were omitted from the analysis. The analysis

reported here therefore includes these outlier cases.

Non-model-based outliers were detected using a limited information approach

in which a single indicator for a given endogenous variable was regressed onto a

single indicator of all variables that directly influenced that variable in the model.

The endogenous variable was regressed onto the predictor variables and the stan-

dardized df beta coefficients were examined for each individual (e.g., outlier = ab-

solute standardized df beta coefficient greater than 1).

Nonnormality.

Multivariate normality was evaluated using statistical meth-

ods in AMOS 5.0 based on Mardia’s test for multivariate normality (Mardia,

1970). The multivariate kurtosis score was 5.74 (significant). An examination of

univariate indices of skewness and kurtosis for all continuous study variables re-

vealed no skewness or kurtosis values above an absolute value of 2.0.

Missing data.

Listwise deletion was used for the 8% of the sample that had

missing data on at least one study variable.

Analyses for the Study Hypotheses and Research Question

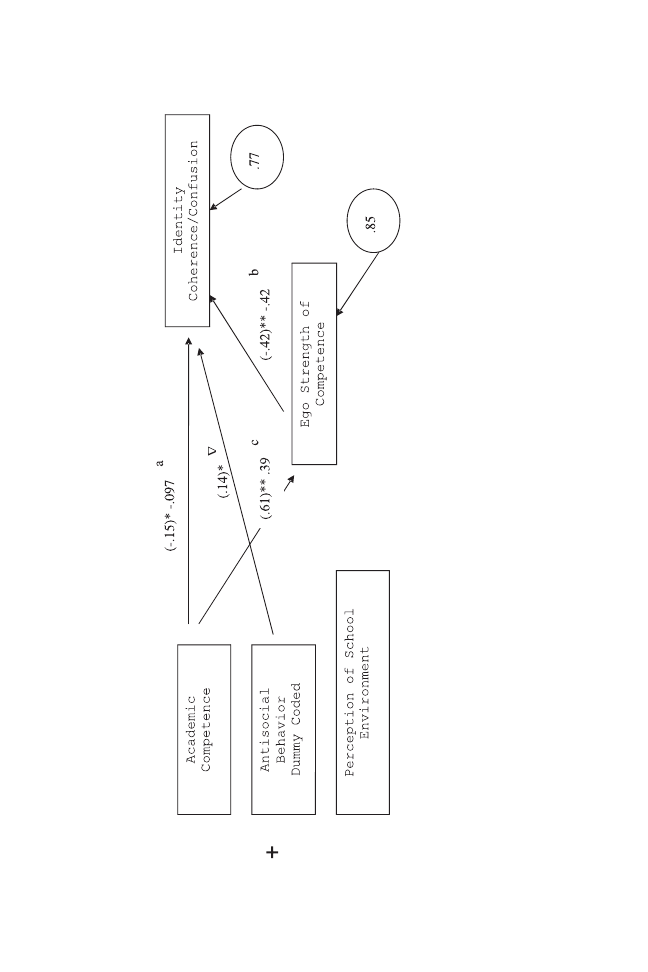

The fit of the model in Figure 1 was evaluated with AMOS 5.0 (Arbuckle &

Wothke, 2004) using the sample covariance matrix as input and a maximum likeli-

hood solution. Criteria for good model fit for global fit indices were: a comparative

fit index (CFI) of .95 or greater, a root mean square error (RMSEA) value less than

.08, a p value for close fit test greater than .05, a goodness of fit index of .90 or

greater, and a standardized root mean residual value less than .05. Criteria for good

model fit for focused fit indices were: modification indices less than 10 and stan-

dardized residual values less than 2.

In the first model tested, causal

1

paths were defined from exogenous variables

to endogenous variables based on the study hypotheses and research question. Ex-

100

FERRER-WREDER ET AL.

1

The term causal path is used strictly in the statistical sense.

101

FIGURE

1

Structural

equation

model

examining

relationships

among

identity

coherence/identity

confusion,

the

eg

o

strength

of

competence,

antiso-

cial

beha

vior

,academic

competence,

and

perception

of

school

en

vironment.

Note:

+

=

Exogenous

v

ariables

are

assumed

to

be

correlated;

*

p

<

.05;

**

p

<

.01;

Ñ

this

path

represents

a

mean

dif

ference

=

.142,

estimated

standard

error

=

.063,

p

<

.05;

a

=

for

ev

ery

2

Lik

ert

scale

point

increase

on

the

academic

competence

scale

(i.e.,

high

numbers

or

increases

are

indicati

v

e

of

lo

wer

academic

competence),

identity

coherence

w

as

predicted

to

decrease

by

.30

Lik

ert

scale

points

;b

=

for

ev

ery

2

Lik

ert

scale

point

increase

on

the

eg

o

strength

of

competence

scale

(higher

numbers

or

increases

are

indicati

v

e

of

lo

wer

eg

o

strength),

identity

coherence

is

predicted

to

decrease

by

.84

Lik

ert

scale

points

;

c

=

for

ev

ery

2

Lik

ert

scale

point

increase

on

the

academic

compe-

tence

scale

(higher

numbers

or

increases

are

indicati

v

e

of

lo

wer

academic

competence),

eg

o

strength

of

competence

is

predicted

to

increase

(higher

n

um-

bers

or

increases

are

indicati

v

e

of

lo

wer

eg

o

strength)

by

1.22

Lik

ert

scale

points.

ogenous variables were assumed to be correlated. Global fit indices for this model

indicated bad fit. Modification indices showed that fit could be improved if a

causal path was defined from academic competence to the ego strength of compe-

tence. Theoretically, such a connection was reasonable and a causal path was de-

fined between these variables. The revised model was reanalyzed.

For the final model, a variety of indices of model fit were evaluated. The

chi-square test of model fit was statistically nonsignificant (

c

2

= 2.687(3), p <

0.442). The RMSEA was 0.000 with a 90% confidence interval of .000 to 0.068.

The p value for the test of close fit was 0.843. The CFI was 1.00 and the goodness

of fit index was 0.998. The standardized root mean square residual was 0.0174. All

indices pointed toward good model fit. Inspection of the residuals and modifica-

tion indices revealed no significant points of ill fit in the model. Figure 1 presents

the final model with relevant standardized and unstandardized (in parentheses) pa-

rameter estimates.

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to contribute to the knowledge base on how identity co-

herence/identity confusion relates to adolescent adjustment. Only a handful of re-

searchers have examined the same or similar phenomena in either predominately

African American, Latino/Hispanic, or both adolescent samples. The present

study makes a significant addition to this literature by investigating these links in a

sample of middle to late adolescents who were predominately African American

and Latino/Hispanic. This study also widens the generalizability of previous re-

search findings with other samples.

The main findings of this study reaffirm previous research that has shown bene-

fits associated with identity coherence or, conversely, risks connected to identity

confusion. Specifically, for the first primary study hypothesis, participants with

lower levels of antisocial behavior had higher levels of identity coherence in com-

parison to those with more elevated antisocial behavior. This finding is consistent

with previous research (e.g., Arehart & Smith, 1990; De Haan & MacDermid,

1999; Schwartz et al., 2005). We also found that, as academic competence de-

creased, so did identity coherence (e.g., De Haan & MacDermid, 1999).

Expanding the conceptual aspect of the model beyond the identity coherence/

identity confusion–adjustment connection, a theory-based hypothesis was pro-

posed (Erikson, 1968); namely, that low levels of the ego strength of competence

would be associated with low identity coherence. This proposition was supported

by parameter estimates which suggested that, for every unit ego strength of compe-

tence decreased, identity coherence also decreased by approximately half a unit.

Interestingly, parameter estimates indicated that as academic competence de-

creased, so did predicted levels of the ego strength of competence. It is notable that

102

FERRER-WREDER ET AL.

academic competence appears to be connected to both identity coherence/identity

confusion and the ego strength of competence. Previously published research has

not identified these specific relations. Yet, such relations are consistent with theory

(Erikson, 1968).

The study findings provided no support for a significant association between

adolescents’ perception of the school environment and identity coherence/identity

confusion and the ego strength of competence. Fit indices, modification indices,

and standardized residual values in the initial and final model did not call for

causal paths to be defined among these variables. Despite the lack of significance

for this variable in the present study, future research should continue to explore re-

lations between contextual variables and indices of identity development (see

Schwartz et al., this issue). Certainly, the total percentage of variance accounted

for in identity coherence/identity confusion and the ego strength of competence in

the final model highlights the need to explore more complex models that include

other key variables.

It is notable that identity-related variables were connected to academic com-

petence, but not adolescent perceptions of the school environment. Future re-

search should closely examine which kinds of school environments or experi-

ences are associated with positive identity development. Qualitative research

exploring potential connections between the meaning of school and the daily

experience of the school and community environments in relation to identity

development may prove important for the next generation of identity-related

interventions.

The study design was cross-sectional. Therefore, causality cannot be assumed

for any of the identified associations. Longitudinal and intervention studies should

continue to be conducted to provide more insight into the relations identified in

this study. An additional limitation was that this study was not, at the outset, de-

signed in a way that lent itself to the ideal use of structural equation modeling

techniques.

Further, the total percentage of variance accounted for in the identity coher-

ence/identity confusion and the ego strength of competence variables suggests that

more variance could be accounted for by exploring increasingly complex models

that include other potentially key latent constructs. Despite its limitations, this

study contributes to what is known about identity coherence/identity confusion

and adolescent adjustment. This and other salient descriptive studies have rele-

vance to the intervention field (see Archer, this issue).

Life span developmental research should be used systematically as a founda-

tion for intervention efforts. Interventions can also further our understanding of

fundamental developmental processes (Kurtines et al., in press). There is a broad

historical evidence base that has linked several indicators of identity development

to adjustment. In addition to this wider literature, a small but growing number of

descriptive studies also have pointed to key connections between identity coher-

IDENTITY AND ADOLESCENT ADJUSTMENT

103

ence/identity confusion and multiple adolescent problem behaviors and positive

youth development in ethnically diverse participant samples.

How can we make use of identity coherence/identity confusion or the ego

strength of competence constructs in an intervention framework? These constructs

represent potentially valuable proxy markers that offer an indication of how

psychosocial development is proceeding at a given point in time. Behind these

proxies are the mechanisms of identity development and other coinciding lines of

human development at work. Research should continue to explore and develop

ways to influence the mechanisms of identity development and examine how po-

tential proxy markers relate to these mechanisms. However, what is clear from the

present study and other related research is that there are direct and significant con-

nections between identity development and adolescent adjustment. Also, when we

advocate ameliorating multiple adolescent problem behaviors and promoting posi-

tive youth development, attention to adolescent identity development can inform

these efforts in a meaningful—and perhaps necessary—way.

REFERENCES

Arbuckle, J., & Wothke, W. (2004). AMOS release 5.0 [Computer software]. Chicago: Small Waters.

Arehart, D. M., & Smith, P. H. (1990). Identity in adolescence: Influences of dysfunction and

psychosocial task issues. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 19, 63–72.

Arthur, M. W., Pollard, J. A., Catalano, R. F., & Baglioni, A. J. (2002). Measuring risk and protective

factors for substance use, delinquency, and other adolescent problem behaviors—The Communities

That Care Youth Survey. Evaluation Review, 26, 575–601.

Chen, L. S., Anthony, J. C., & Crum, R. M. (1999). Perceived cognitive competence, depressive symp-

toms, and the incidence of alcohol-related problems in urban school children. Journal of Child and

Adolescent Substance Abuse, 8, 37–53.

De Haan, L. G., & MacDermid, S. M. (1999). Identity development as a mediating factor between ur-

ban poverty and behavioral outcomes for junior high school students. Journal of Family and Eco-

nomic Issues, 20, 123–148.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

Gray, M. M., Ispa, J. M., & Thornburg, K. R. (1986). Erikson Psychosocial Stage Inventory: A factor

analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 46, 979–983.

Harter, S. (1982). The perceived competence scale for children. Child Development, 53, 87–97.

Kurtines, W. M., Ferrer-Wreder, L., Berman, S. L., Cass Lorente, L., Silverman, W. K., & Montgomery,

M. J. (in press). Introduction to special issue on promoting positive youth development: New direc-

tions in developmental theory, methods, and research. Journal of Research on Adolescence.

Kurtines, W. & Montgomery (2008). (Eds.). Promoting positive youth development: New directions in

developmental theory, methods, and research. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23, 1–130.

Mardia, K. V. (1970). Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika,

57, 519–530.

Markstrom, C. A., Sabino, V. M., Turner, B., & Berman, B. C. (1997). The psychosocial inventory of

ego strength: Development and validation of a new Eriksonian measure. Journal of Youth and Ado-

lescence, 26, 705–732.

104

FERRER-WREDER ET AL.

Mitra, D. L. (2004). The significance of students: Can increasing “student voice” in schools lead to

gains in youth development? Teachers College Record, 106, 651–688.

Moore, S., & Boldero, J. (1991). Psychosocial development and friendship functions in adolescence.

Sex Roles, 25, 521–536.

Morrison, J. W., Ispa, J. M., & Thornburg, K. R. (1994). African American college students’

psychosocial development as related to care arrangements during infancy. Journal of Black Psychol-

ogy, 20, 418–429.

Rosenthal, D. A., Gurney, R. M., & Moore, S. M. (1981). From trust to intimacy: A new inventory for

examining Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10,

525–537.

Rosenthal, D. A., Moore, S. M., & Taylor, M. J. (1983). Ethnicity and adjustment: A study of the

self-image of Anglo-, Greek-, and Italian-Australian adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence,

12, 117–135.

Schwartz, S. J., Pantin, H., Prado, G., Sullivan, S., & Szapocznik, J. (2005). Family functioning, iden-

tity, and problem behavior in Hispanic immigrant early adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence,

25, 392–420.

IDENTITY AND ADOLESCENT ADJUSTMENT

105

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Identifcation and Simultaneous Determination of Twelve Active

Am I Who I Say I Am Social Identities and Identification

HYPERTENSION IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS AZ

Identity and the Young English Language Learner (E M Day)

Cruz Jansen Ethnic Identity and Racial Formations

Identification and fault diagnosis of a simulated model of an industrial gas turbine I6C

Cruz Jansen Ethnic Identity and Racial Formations

19657249 subaltern studies collective schizophrenic identity and confronted politics a revision

Generic Identity and Intertextuality

Borderline Personality Disorder and Adolescence

0415165733 Routledge Personal Identity and Self Consciousness May 1998

Akerlof Kranton Identity and the economics of organizations

identifying and discussing feelings 201

Variation in NSSI Identification and Features of Latent Classes in a College Population of Emerging

Susan B A Somers Willett The Cultural Politics of Slam Poetry, Race, Identity, and the Performance

Cultural Identity and Globalization Multimodal Metaphors in a Chinese Educational Advertisement Nin

Alpay Self Concept and Self Esteem in Children and Adolescents

Work motivation, organisational identification, and well being in call centre work

więcej podobnych podstron