Italian Tour Lecture Notes

Subtleties,

Boldness

&

Misdirection

Barrie Richardson

Shreveport, Louisiana USA

Fall, 2002

Table of Contents

I. Introduction

1

II. Routines

Challenge Card to Pocket

3

Word Flight – Revisited

11

Third Card Rising

15

A Game of Intuition

19

Everyone

a

Winner

25

Quartet

31

Another

World

35

Rounders

43

Devious Deck Switch

45

Barrie Richardson

620 Delaware Street

Shreveport, Louisiana 71106

USA

Tel: 318/865-8502

Fax: 318/868-9587

Email: richardsonbarrie@netscape.net

Challenge Card to Pocket

Introduction

This is an effect, which can be done at any time without any preparation. It

can be done with a borrowed deck for one person or on a platform for a large

audience.

Effect

The performer invites a woman to think of a card. She is handed a deck of

cards and asked to remove the card she is thinking of.

The performer retrieves the pack, and the card is returned to the deck. The

deck is handed over to the spectator with the instructions to hold the deck,

between her hands.

The performer steps back. First he says, “I will tell you your card.” He does

this by dramatically revealing the card that is in her mind.

Next he says, “I will tell you where your card is located. Watch closely.”

The performer – whose hands have never entered his pocket – challenges the

audience to watch him.

His left hand is turned upward and shown empty before it enters his left

trouser pocket. A card is removed. It is the woman’s card.

Explanation

Notice: All the illustrations show the deck being held face-up, so that you

can see more clearly what is happening. The deck you use to perform will

be, of course, face down.

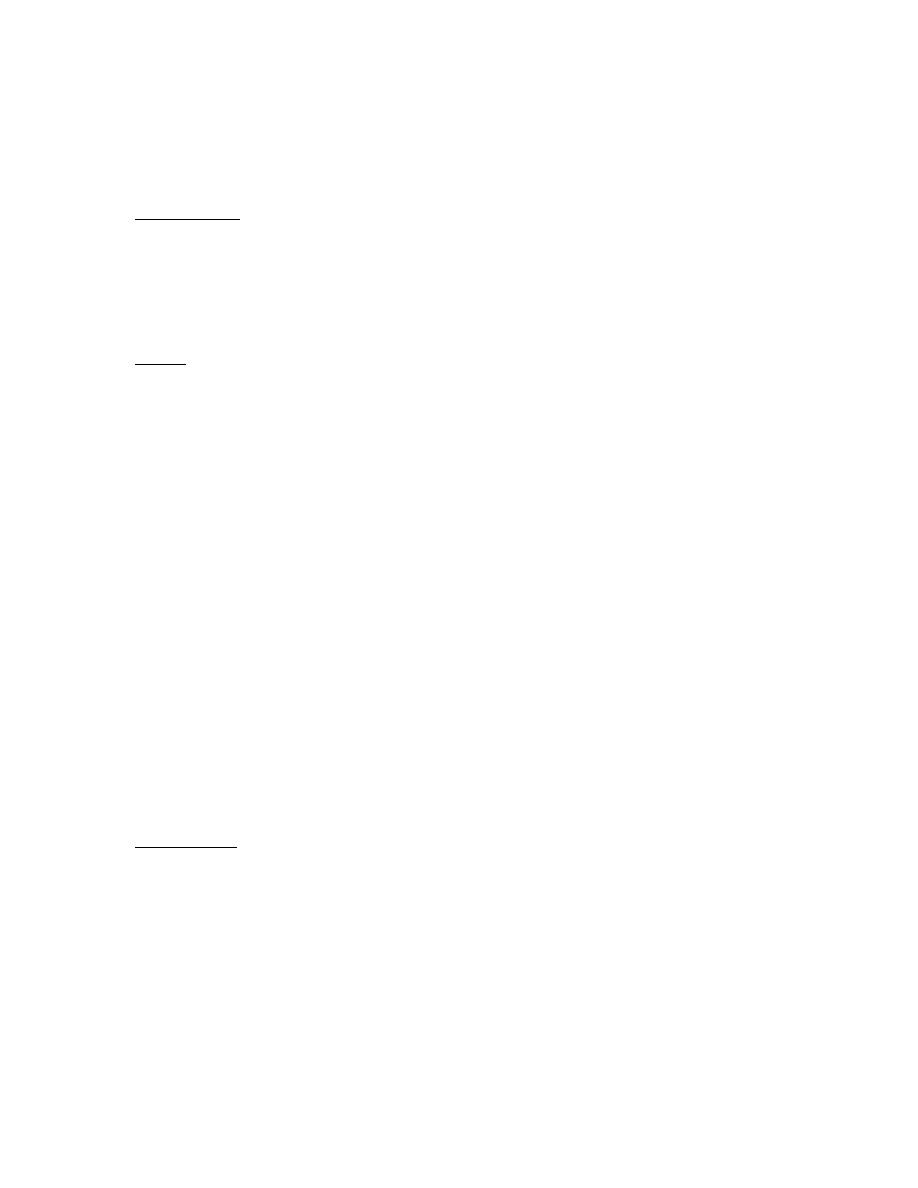

Figure 1. This is a Fred Robinson move. The selected card is returned to

the deck near the center. It is out-jogged about two inches then pushed into

the deck with fingers of the right hand. However, in reality, it is twisted

3

slightly to the right at the outer end. This situation is concealed by the right

hand, which is on top of the deck.

Figure 2. This is a deceptive move I learned from Fred Robinson. The left

thumb runs up the long side of the deck. This pushes the card flush. As this

meticulous squaring action is happening, you can easily peek the selected

card.

Figure 3. The deck is returned to the left hand and the jogged card is

squeezed with the first finger of the left hand, and the selected card is pushed

out of the back of the deck.

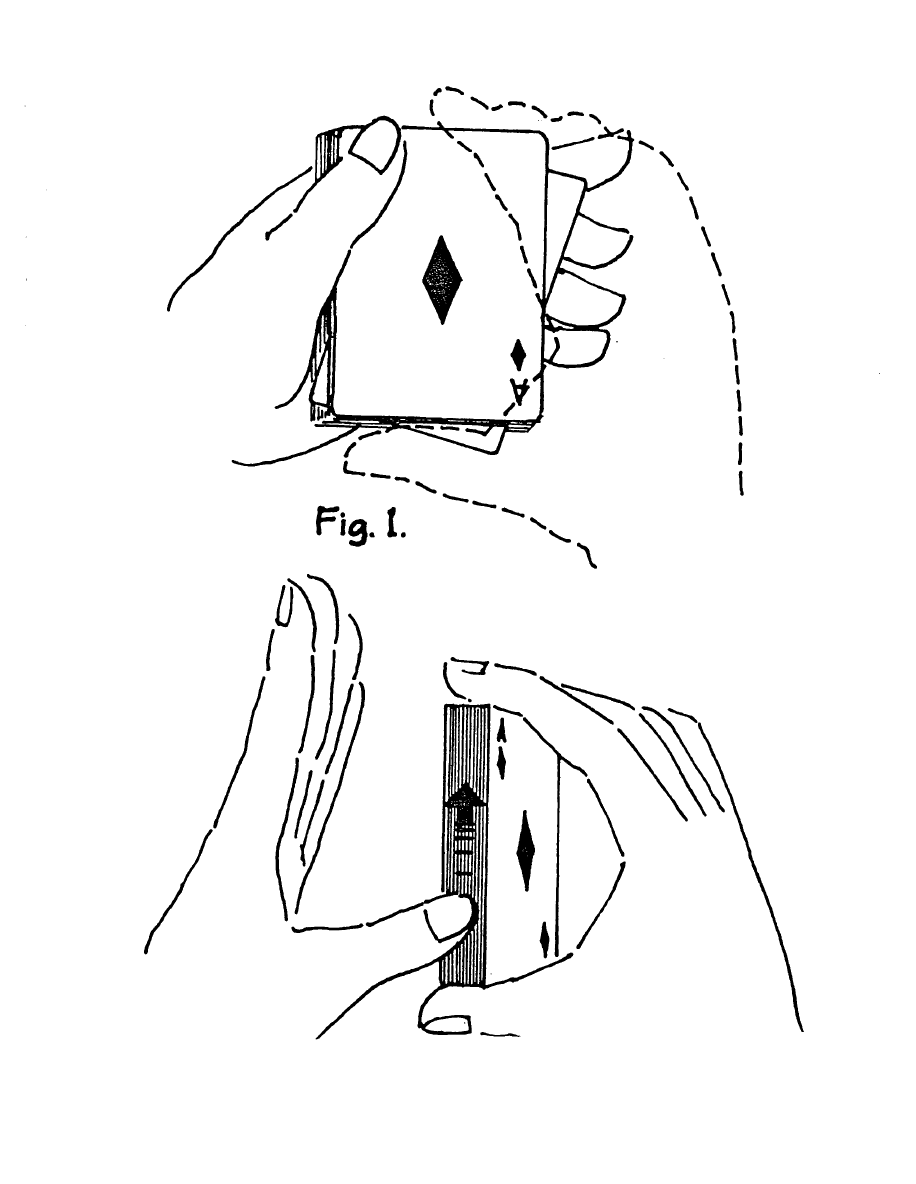

Figure 4. The card will now be stolen. The left fourth finger swivels the

out-jogged card to the left. Once this occurs, the right hand adjust its grip,

seizing the outer right corner of the pack with the thumb on top and the first

finger and second fingers below.

Held this way, the pack can be stripped away leaving the selected card

behind in a palm position. The card can be pushed further back in the left

hand than shown in the illustration if there are no people on your left.

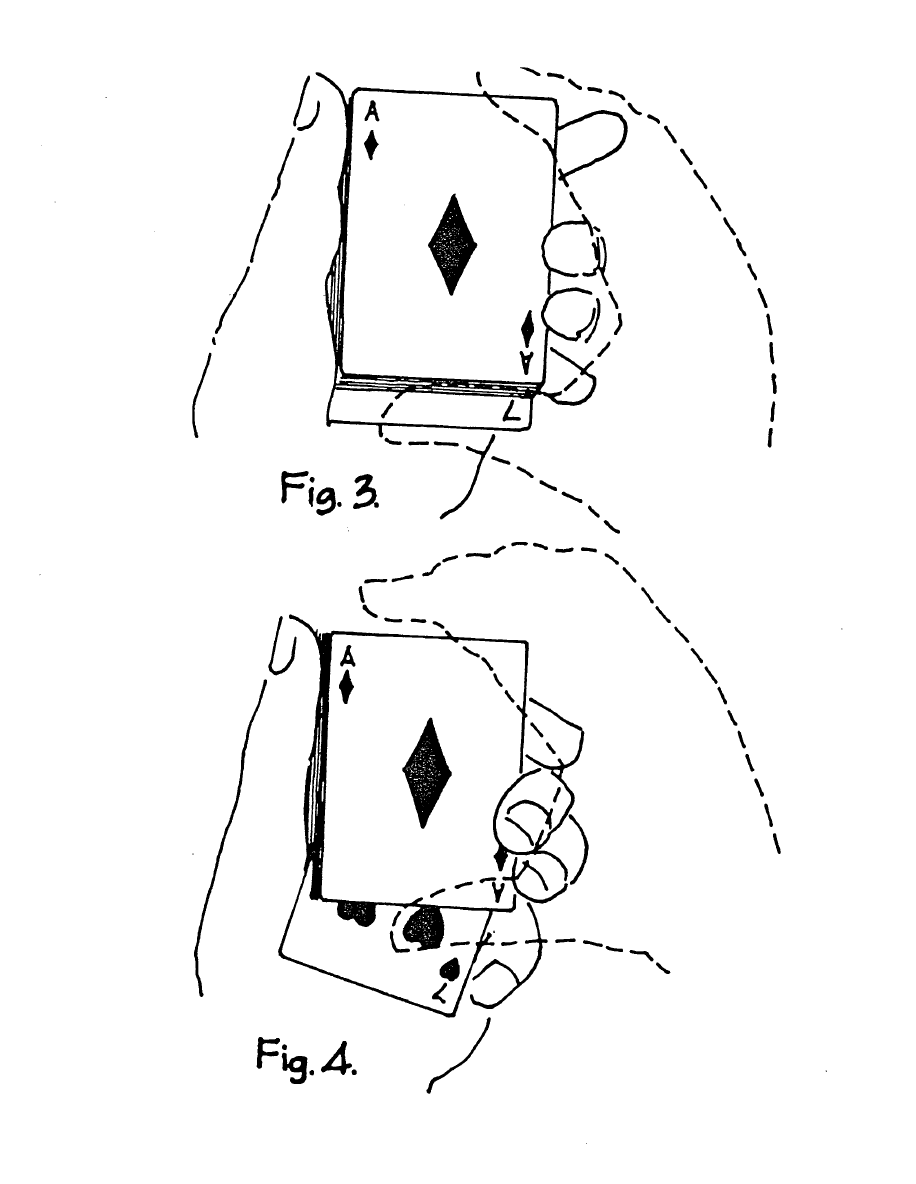

Figure 6. The left hand hangs casually at your side. Note how the fingers

are curled and relaxed. The audience can see through the tunnel in your

hand. You will be in this position for a few minutes during the process of

revealing the name of the card. This pause and relaxed position is a major

deception.

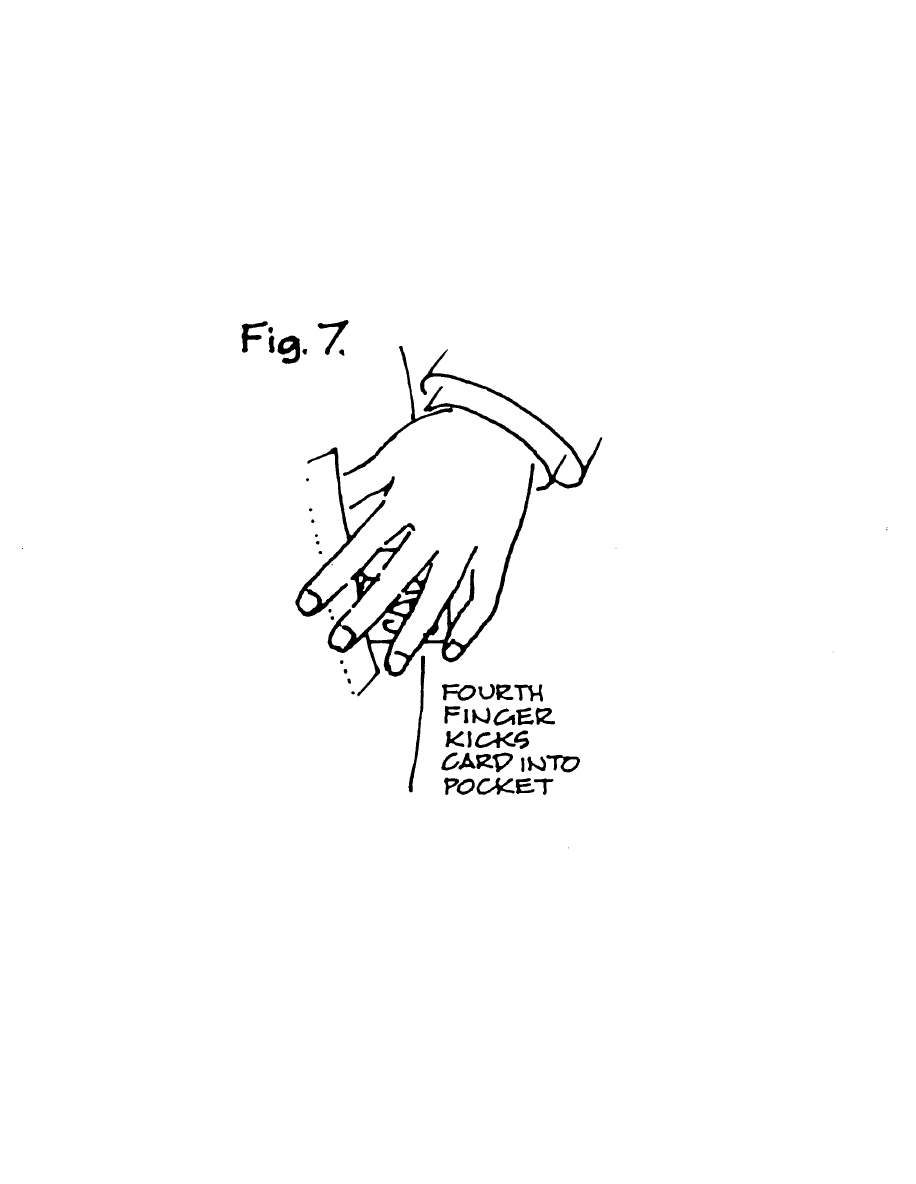

Figure 7. This shows how the palm card is inserted. The left hand moves up

along the trousers and the left thumb presses against the card holding it

against the palm. The fingers can be opened. The outer tip of the card is

slipped into your pocket when your left thumb enters.

Then your fourth finger of your left hand swivels the card and in so doing,

the card slips into the side pocket. Not shown is that once the cad is secretly

kicked into the pocket, the left hand with the finger still in the pocket is

turned over and seen to be empty. The open left hand can now slide up and

down the entrance to the side pocket, which is a clear demonstration of an

innocent procedure.

4

This process of loading is an extension of the work of my British friend

Gordon Bruce. Ed Marlo also has a method to load a card from the

gambler’s palm.

Good Luck!

Barrie Richardson

5

6

7

8

9

Word Flight – Revisited

Introduction

In Theater of the Mind (p.245), I published one of my favorite mind-reading

effects. I have been surprised by how many magicians I have met since then

who think the effect is unworkable or that the person involved will feel like

a stooge.

Some professional magicians have asked, “What do you do when it doesn’t

work?” I respond not with arrogance, but with truthfulness that it always

works. Furthermore, the person is as mystified as is everyone else.

The Bare Bones

For those persons who are interested in the presentation of this routine, you

many want to refer back to Theater of the Mind.

Basically, this is what happens. A woman is invited to tear up a sheet of

newspaper into small pieces – possibly the size of a business card. She

freely selects a piece and is asked to hold the paper between both hands with

arms outstretched.

She is told to shut her eyes tightly – very tightly – and when the performer

counts to three, she is to open her eyes and let one word float up into her

mind. After she has a word, she is to immediately close her eyes and crush

the piece of paper in her hand and drop it to the floor.

The performer, standing at a distance, invites her to open her yes. He then

dramatically reveals the word she is thinking of.

It must be real mind reading.

Explanation

The solution is simple, bold, and deceptive.

A single word is cut out of a newspaper with sharp scissors (not torn).

11

This word should be a common word, preferably a noun. For example,

woman, money, church, picture, soldier. The word selected should be a

common word and probably not more than eight letters. Never select a

foreign word or a word that might embarrass the person. In short, you want

a fairly bland non-controversial word that is easy to remember and to spell.

The word you cut out should also be of a slightly larger and darker print, but

it should not be too much larger or bolder. (See example)

This single word cut out of the newspaper is going to be stuck on the scrap

of newspaper selected by the person assisting you. Invisible tape is the best

tape to use since it will not be seen.

The word is put on the underside – the sticky side – with about one-half inch

overhand. The tape dispenser can be loaded with several words and rolled

back to its original position.

The only preparation is to pull off a small piece of tape and hold it stuck at

its edge on your second finger. In this position, you can move and act quite

normally until it is time to stick the small piece of tape to the selected scrap

of paper.

This action takes place while the scrap selected is on the table. You should

use the same action as putting a stamp on an envelope. However, the word

is put on ‘upside down’ relative to the print on the page. The whole process

seems fair so far, and the dirty work is over before you start.

Some additional hints and ideas

1. Your instructions must be clear, and you must be serious. This is an

experiment, and you explain you want your assistant to be successful.

2. Situate the paper in her hands so that the text is upside down. Do this as

you ask her to hold paper in both hands and extend her arms. Now have her

shut her eyes – very, very tightly. When she opens her eyes, her vision will

be blurred. The only word she can possibly see is the word that you have

glued to her scrap of paper.

12

The word does seem to appear out of a fog, and the person will later claim

this is the word she had thought of.

It is imperative to command the environment and to get the person a little

nervous about the experiment and eager to please.

3. Rather than telling the audience the word she has in her mind, I like to

say that I am reading her eyes. She thinks just of the first letter. I call off

the 26 letters of the alphabet and find the first letter. I continue for one or

two more letters, pause and reveal the word.

This is a lot of entertainment for one ‘postage stamp’ move.

Good Luck!

Barrie Richardson

13

14

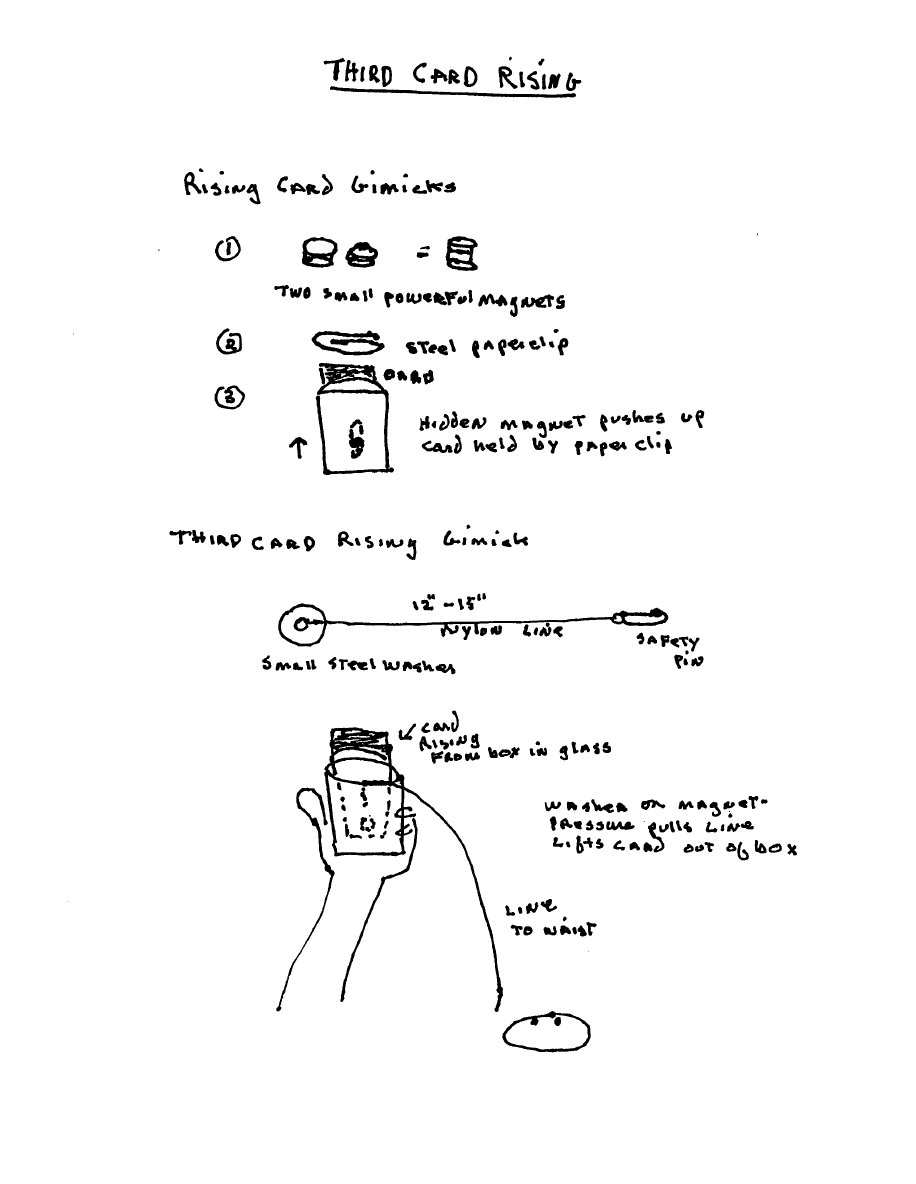

Third Card Rising

Background

In the summer 1996 issue of Club 71, I published an effect called

Impromptu Rising Card. I basically thought of the trick as a rather informal

method to do the rising card effect. During my lectures to magic societies, I

was surprised to discover the audience of magicians applauding this trick,

and then they gave even more applause when I explained the simple

gimmick used.

Both the effect and method are easy to understand. Three cards are selected.

The performer secretly puts a steel paperclip around these cards. When the

borrowed cards (only half the deck is used) is replaced in the card box, the

performer – obviously unknown to the audience – places a small powerful

magnet on the outside of the box where it adheres through the box and

several cards on top of the deck to the metal paper clip. When the magnet is

pushed upward, the clip carrying the cards rise out the deck. The cards

behind the face card is secretly pushed back down as the risen card is

removed. The process is repeated for the second card.

What follows is a way to make the third card rise in an even more stunning

fashion than the first two cards. The card case is placed in a large coffee

mug, which is held on the performer’s open hand. The third card rises in an

eerie manner.

Extensions and Explanation

Since publishing this Impromptu Rising Card effect, I have developed a few

additions and extensions.

They make the trick less impromptu, because you need another gimmick, but

the effect can still be performed in almost any setting – on a platform, at a

table or standing in a living room.

First of all I have found that it is worth the effort to cover the front side of

the paper clip with a small piece of playing card. The obviously restricts

your capacity to use borrowed cards. The small, glued piece keeps the shiny

surface of the paper clip from flashing, and it hides the metal clip so the

cards can be handled quite freely.

15

Secondly, I now locate the paper clipped cards four or five from the top

rather than much deeper in the pack. This action obviously increases the

magnetic attraction and thereby makes the card rising more secure.

After the card case is placed in a wide-mouth coffee mug, the mug is placed

on the palm of the left hand, and the right hand can circle the mug to

demonstrate that there are no threads or wires.

The card rising out of the mug is much more astounding to the audience than

when the card case is held in your hand.

How does the card rise? The answer is that there is a hidden thread that

pulls the magnet upward which in turn causes the card to rise.

I use a fifteen-inch piece of two-pound nylon line. This is used for fly

fishing, I believe.

One end of the line is tied to a steel washer, and the other end is wrapped

around a small piece of putty or Blue Tac. The putty is then firmly attached

to a large paper clip. If you choose to forego the putty, you can tie the line

directly to the large paper clip.

This paper clip is stuck into the waistband of your slacks behind your belt.

The washer attached to the line is put in your left pant pocket where it can be

secured when needed.

After the first two cards rise, go to the table and pick up the mug and show it

to be quite innocent, and at the same time, secretly get hold of the washer.

If you look at the illustration, you will see how easy it is to get the threaded

washer into your left hand without going into your pocket.

The left thumb loops under the thread and with a slight extension of the left

hand, the washer is pulled out of your pocket into your hand.

This action occurs while the coffee mug is being shown to the audience.

Now comes the most difficult part of the routine. The magnets – I now use

two small magnets one on top of the other – are so strong that when the

washer in your right hand comes close to the deck that you are now holding

16

in your left hand, that it will jump over to the magnet with a loud clicking

noise. This is not acceptable.

The way I prevent this noise is to cover the washer completely with my left

thumb and when my hands come together, I place the edge of the washer on

the magnet and then remove my left thumb. This action cushions the

attachment process and does away with the clicking sound. This explanation

will be quite clear if you experiment.

The illustration shows the situation which now exists. The cup is on the left

palm, and the line runs almost vertically from where it is anchored to your

slacks over the lip of the cup and then down to the magnet which is near the

bottom of the card box.

I have found that a little pull on the string will loosen the remaining card and

get it ready to rise cleanly.

Now you can move your right hand all around the cup since the string passes

backwards near your left arm.

The third card will rise if you move your left hand slightly forward giving

the needed tension. I do not move my hand. Rather, I push out my stomach

and make the line taut and then when I suck in my stomach, the card rises

with no apparent movement.

The clean-up is not too hard. The card is removed, but before it is taken

from the deck, the left hand pulls the magnet away. The paper clip will be

attached to the bottom of the final card, and this is easily removed as the

cards and mug are given for inspection. The clip is put on the magnet in the

left hand and ditched in a side pocket. You are now ready to repeat the

effect.

An alternate clean-up is to steal the magnet away and squeeze the card case

so that the paper clip is left behind when the card is removed.

Good Luck!

Barrie Richardson

17

18

A Game of Intuition

Introduction

This is an old and wonderful effect. A spectator is given five cards each

with a different design. The performer holds a matching set. The performer

places one face down on the table and the participant is asked to look over

her cards – which only she can see – and place the one she believes matches

the card the performer put on the table. She places her card on the top of the

one on the table. This is repeated four times with lots of opportunity for by

play with the person.

When the cards are turned over, all the designs are paired. Is it luck?

I have not been able to discover who first developed this effect. However,

the basic concept of “being one behind” has a very long history. This effect

has used several different methods. Many of the methods for doing this

perplexing stunt require sleights or specially prepared cards.

This approach does not use printed ESP cards, but rather regular business

cards are employed. There are no sleights or misdirection needed in this

particular presentation.

Is this solution better than the other approaches? From the audience’s point

of view, I doubt it. Yet the seemingly informal nature of the experiment and

its simplicity of method has a certain attraction – at least to me.

Synopsis of the Presentation

After a discussion of ‘woman’s intuition,’ a woman is invited to participate

in an experiment.

The performer removes a fairly large block of his business cards from his

wallet and openly displays them. The cards, the performer points out, have

five different drawings on the blank sides. He shows that these drawings are

repeated on the other cards. He also holds a few business cards which have

no drawings. Five cards, each with a different drawing, are given to a

19

woman along with two blank cards. The performer holds the remainder

seven.

The performer now explains the experiment. He tells the woman it is her job

to match his card.

“For example, if I put a blank card down like this, you would put yours on

top of mine.”

She does this.

“Let’s do it one more time so you are totally clear about the procedure.”

Once again, the performer puts down a blank card, and the woman puts hers

on top.

“Now our experiment gets interesting. I will put my card down first, but

face-down, and you will use your intuition to match it. You will put your

choice face-down on mine. We will do all five cards and then see how well

your intuition is working today.”

The four blank cards are picked up and returned to the performer’s hand. He

now holds nine cards.

The performer places one of his cards picture-side down on the table, and

the spectator is asked to use her intuition to match this card. She is asked to

place one of her cards face-down on top of the performer’s. She is reminded

that the performer always places his card first, and he never sees the face of

the cards she puts down.

The procedure continues. It appears guileless and straight forward, because

it is.

There are now four sets of cards on the table which the performer has kept in

a fairly neat arrangement in that each pair overlaps the previous pair.

The performer puts a fifth card down on this group of pairs, and the

spectator drops her remaining card on top.

20

The performer slowly and openly – using both hands – assembles the cards.

In so doing, he openly slips the remaining cards in his left hand under the

cards as they are made into a neat pile.

He leans back. Nothing is in his hands. The business cards are there in the

center of the table.

The participant is invited to see how well she has done. The top two cards

are removed.

They match, and so do all the other pairs.

The remaining cards in her hands are blank.

Some people really are intuitive.

Explanation

The five pairs of cards have different drawings. I personally try to stay away

from ESP patter, so I prefer drawings such as a smiling face, an ice cream

cone, a tree, a house and a flower. Each of these five simple drawings are

draw in in the same way on two cards.

The printed side of the cards are marked with a pencil dot placed in a way

that each marking represents a number – one through five. Each of the five

pictures is assigned a number which is easy to recall. For example, the

smiling face (one circle) is the number one; the ice cream cone, two sections,

is two, and so on.

I have tried many subtle markings over the years. My eyes are not strong,

and often I am in dim lights when I perform in a close-up situation. I find

that a definite pencil mark works best for me. I also place the mark so the

orientation of the card will not cause me to hesitate. In any case, all the

pairs are marked in the same way so that so long as you give the person five

different cards, you can read the backs – the side with printing.

You also need four more blank business cards, and then you are ready to do

a memorable demonstration without any special preparation.

21

What follows is a standard procedure with one change that makes the effect

self-working.

After a careful explanation of what this experiment is about (this is

important and should not be rushed), the performer places a card face-down

on the table. Initially the performer is holding nine cards. Five have

drawings and four are blank. The first card placed down is a blank card.

The spectator – following your instructions – put her selection face down on

top of the card you have placed down on the table. After determining the

identity of the card she has placed down – let’s assume an ice cream cone –

the performer fans out the cards in his hand, thinks for a few seconds and

places his card with the picture of an ice cream cone picture-side down on

the table. Let’s assume she puts a card on top, and you know by the

marking, it is a flower. You then place a flower down as your next

selection. This process continues until the fourth pair is placed down.

The spectator now has one card left. You have two cards with pictures and

three white-backed cards.

The two remaining picture cards will be squeezed together and held as one.

The match of the woman’s fourth card – the one on the top of the pile – will

be the card on the bottom of the two cards you place down as one.

The placement of the two cards held as one on the pile is easy to do. When

you casually place your final card(s) on the stepped row of cards, you upset

the cards slightly causing a little unnoticed optical confusion. Remember,

the experiment is almost over. The person has a final card to place down,

and all the actions have been totally fair. The last card is of little concern.

The situation is this. All the cards are now in matched pairs since you

always matched the spectator’s selection, and the cards have the exact same

drawings. There is one problem. There are eleven cards on the table. The

bottom card has no drawing.

Rather than palm this card off or hide it somehow in the process of

displaying the cards, the blank card is made irrelevant.

22

In the process of carefully assembling the cards, the remaining three blank

cards in you left hand are casually placed under the tabled cards and the

completed stack is left on the table.

There it is. No preparation, no special cards, and no sleight of hand.

Good Luck!

Barrie Richardson

P.S. I now use only four sets of cards. This is still stunning and quite

believable. I need only carry eleven cards.

23

24

Everyone a Winner

Introduction

In most ‘bank night’ type effects, the performer ends up the winner, and the

spectators are ‘losers.’

This is a straight-forward and easy-to-understand effect in which there are

no losers – yet there is still a mystery.

The whole effect is dependent on one move. This is not a hidden sleight, but

an open maneuver much like Paul Curry’s ‘switch move’ that he does with

cards.

This deceptive procedure was taught to me over 50 years ago by Victor

Torsberg on a Saturday morning at the counter of the National Magic

Company. It was called the ‘two-card monte’ move, and it is basically so

deceptive that it often fools me. Dr. Daily published a similar move,

‘Daily’s Delight,’ in Phoenix #220, p. 881. In any case, I have slightly

modified the move and applied it to this demonstration.*

Effect

The performer puts six pay envelopes on the table.

He picks up two – one in each hand – and he invites a person to participate

in a guessing game.

“In one of these envelopes, there is a valuable coin. Actually, it is not too

valuable,” he says with a smile. “It is a dime. In the other envelope, there is

a piece of paper.”

The performer crosses his hands at the wrist and indicates that the envelope

in his right hand will be the spectator’s, and the one in his left hand will be

the performer’s.

25

“Do you want to take this envelope or do you want to switch? You know

you have a 50-50 chance. But once you declare your decision, you can not

change. What do you say, keep it or switch?”

“Switch,” she says.

The performer uncrosses his hands and places the envelope in his left hand

down on the table next to her.

The procedure is repeated, but this time she does not switch envelopes. The

third time she asks to have the envelopes switched.

The performer explains that the probability of getting one coin is quite high,

but the probability of getting three coins is higher than most people would

guess – it is once out of eight times.

Let’s see how well you have done.

The first envelope is squeezed open, and a coin falls out.

“Lucky you.”

The second envelope is opened, and another coin is dropped on the table in

front of the helper.

“Are you psychic,” he asks.

Remember, only one out of eight times do you select all three coins.”

The third envelope is opened, and the coin joins the others.

“Congratulations, you are a winner, and the coins are yours to keep as a

memento.

“Let’s look at your rejects.”

The first envelope is opened.

“There is a piece of paper – true, but it is a $1 dollar bill.”

26

The second envelope has a $10 dollar bill, and the third, a $100 dollar bill.

The performer remarks, “’Guess I am lucky that you are so good at picking

winners.”

Explanation

The envelopes are ungimmicked. Three envelopes each contain a coin.

Bills are placed in the other three envelopes.

A small pencil mark on the envelope allows you to identify each of the

envelopes with bills and their denominations.

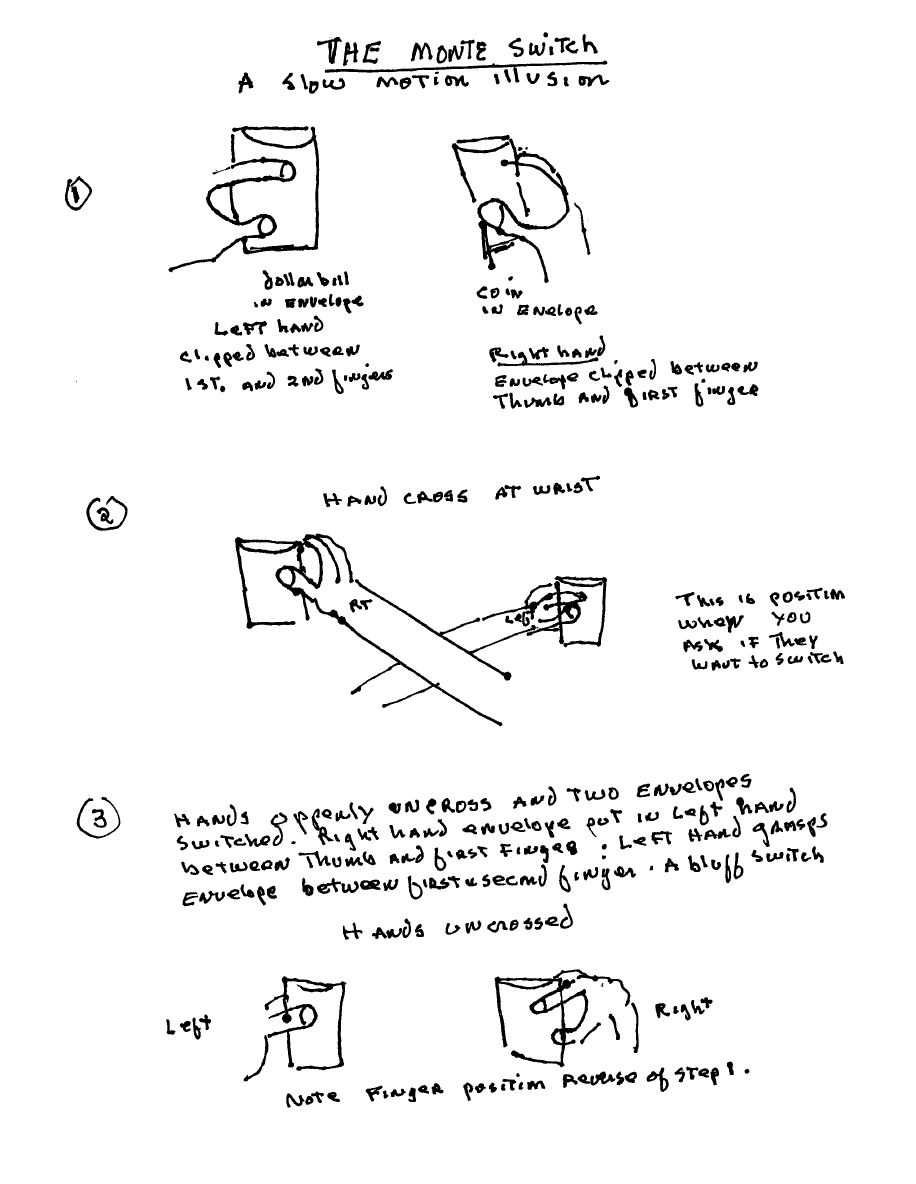

The envelope with the coin is always held in your right hand, clipped

between the first finger and thumb.

The envelope with the bill is always held in the left hand, but, in this case, it

is clipped between the first and second fingers.

The drawings are self-explanatory.

What happens is that as the hands are being uncrossed, the envelope in your

right hand is placed between the thumb and first finger of the left hand, and

at the same time, the envelope in your left hand is clipped between the first

and second fingers of the right hand.

The whole procedure seems above-board and fair. In reality, the envelope in

your right hand – the one with the coin – is not moved over to the other side,

but picked up by the left hand as the hands uncross.

You must be calm and not fumble. It should appear as if you openly

switched envelopes in your hands and placed them down. It is the

uncrossing of the wrist at the same time that creates the appearance of the

switch of positions. The envelopes are openly switched – but they are kept

in their location with the uncrossing of the wrist.

Try this with two face-down playing cards, and you will see why it was

called the ‘two-card monte move.’

Of course, you could use four or five envelopes, but maybe three is enough.

27

The same switching routine could be done with face-down photographs – i.e.

a man finds all the beauty queens or for children where a child selects the

cartoon characters that he likes.

Another option – and this is quite an attractive one – is to do the switching

process so you get all the coins. Open each of your envelopes, and let the

coins drop and clink in a glass. You have apparently won. Then invite the

person to open his envelopes. He finds three five-dollar bills that he happily

keeps.

I have a strong preference for tricks that have ‘no moving parts’ such as this

one. I think they are elegant both in terms of clarity of effect and the

disguised method.

* For the origin of what Daily calls ‘A Sleightless Sleight,’ see Phoenix

#22, p.887. Dr. Dailey’s Delight

28

29

30

Quartet

Introduction

In Theater of the Mind, I published a memory stunt called “Quasi-

Memorized Deck.” This effect is a more challenging and dramatic variation

of that trick.

Presentation

Four persons are invited to the platform. Two are situated on the left of the

performer and two on his right.

A deck of cards is mixed by the performer and then cut in half. A portion is

given to a man on his left, the other to a man on his right. The cards are

thoroughly mixed by these helpers.

Then the performer splits these ‘half decks’ in half again and gives a packet

to the other two men. Now all four person have packets which they shuffle.

The performer explains to the audience that he is going to try to locate all the

cards after he retrieves them. This, he explains, is like visiting a four-room

house in which there is a party going on. After looking in each room, he

might have a good idea where all the people at the party are located.

He retrieves a packet of cards from one person and looks at each card for a

second or less. He does the same process with the other three packets. He

then invites his helpers to segregate the cards they are holding by suit.

Standing like a choir director, the performer calls the cards in the diamond

suit and as he calls each card, he points to a person. The person lifts the card

up, shows it to the audience, and drops it to the floor.

The performer locates all the diamonds. Then at a faster and faster pace, he

finds the clubs and the hearts. After a pause to catch his breath, he quickly

identifies all the spades.

31

Explanation

First of all, the performer knows who holds which cards before he ever looks

at the cards. The cards, even though shuffled, are ‘unshuffled’ unknown to

the audience. The same packet of cards will always be given to the person

standing in the same position.

This being the case, you must find a way to memorize the location of fifty-

two cards, and practice this until you know it cold.

I use the same sequence as my memorized deck; however, if I were to start

fresh, this is what I would do.

First take the thirteen diamonds. Sort them into four groups. Now, with no

memory codes, practice for thirty minutes every day for a few days until you

have absolute command of where these thirteen cards are situated in the

quartet. You may find ‘runs,’ i.e. three, four and five of diamonds, then the

six and seven and so on. This memory task is not as daunting as you may

think.

Next do the same with clubs. This will probably go faster because you will

now sense a rhythm of sequence with the distribution.

Now arrange the hearts and spades so that they have the same sequence as

the diamonds and clubs. Now rotate these packets by one location. This

means you will start your counting one person over, but follow the exact

same sequence as you did for the other suits.

Now, how do you get all the cards to the right persons after all the shuffling?

The system I use is called ‘rounders.’ These are cards that behave the same

as stripper cards, but have two advantages. First of all, you never miss a

card. One ‘squeeze’ along the edges, and they all divide. Secondly, the

cards can be turned end-for-end (unlike strippers), and they still work

perfectly.

The deck consists of two sections. Section A will go to the left side and

Section B will go to the right side. Section A will be shuffled fairly and then

divided. In the process of dividing the cards, they are unshuffled. Then a

known packet of cards is given to each of the men standing on your left.

32

The same action is followed on your right.

It appears that you shuffled the cards – you can actually shuffle the first

twenty or so cards – divided the cards which were fairly shuffled, and then

divided them again for another fair shuffle.

This stunt takes some good acting. The audience must not think of this

demonstration as a magic trick, but rather a demonstration of an astounding

memory.

Good Luck!

Barrie Richardson

33

34

Another World

The Mt. Kenya Paradox Revisited

Introduction

Several years ago, I published an effect called The Mt. Kenya Paradox.* I

liked the patter, but I thought the routine deserved a stronger effect.

One of the most powerful effects in all of magic is Paul Curry’s “Out of This

World.” There have been many variations developed over the years. One

that is particularly elegant was developed by Tony Bartolotta (Outworlder)

and was published in Karl Fulves Discoverie (Issue #7), 2002.

His brilliant presentation involves two persons sitting across a table. A tray

is placed on the table, and each person is instructed to distribute the portion

of the face-down deck they are given into red and black piles. When the

cards are tallied, both persons have amazingly sorted the cards by color.

There are no sleights. The performer never touches the cards.

This version uses Bartolotta’s two-persons-at-a-card-table approach, but I

have done away with the tray and the pencil and paper counting ploy he

utilizes.

The Stage Setting

I will present this effect as if I were performing on a platform in front of a

fairly small group.

On the platform, there is a card table and two chairs. The chairs are opposite

each other and arranged so that the audience has a side view of both chairs.

The table is empty.

Presentation and Effect

“This evening I would like to relate an astonishing experience that happened

in Kenya in the summer of 1995.

35

“My wife and I were on a photographic safari and as we were moving from

one game preserve to another, we crossed the equator. Our driver stopped

our van at a place where an entrepreneurial person had set up an exhibit for

travelers next to his small stall.

“We gathered around him as he took a large bucket of water to one side of a

yellow stripe he had painted across the road, denoting the exact location of

the equator. He dipped a smaller bucket into the one filled with water, but

this smaller bucket had a hole in the bottom. The water came out of the

smaller bucket the way that water flows out of a sink. We looked into the

bucket, and the water swirled around in clockwise fashion. Next he moved

ten yards on the other side of the equator line, and this time, the water

swirled in a counter clockwise fashion. Then he picked up his large bucket

and moved it directly on top of the yellow line. He filled the smaller bucket

with water, and this time the water did not swirl at all, but ran straight out.

“But strange and provocative as the water demonstration was, something

happened to us that night that was even more perplexing.

“That evening we were staying at the Mt. Kenya Safari Club. This was the

only time on our excursion that we had to dress for dinner. Following a

leisurely and sumptuous meal, we were sitting in the lounge sipping an after-

dinner drink when a distinguished looking man in his sixties sat down near

us. We began to chat.

“We discovered that this man’s name was Charles Austin, and he was

Australian. He was a developer of shopping centers, both at home and in the

Middle East. His outside interests were photography and, of all things,

poker.

“Let me stop my story for a minute and try to reconstruct the experience we

had by inviting a man and a woman to come forward and sit opposite each

other at this table. As I progress with the story, they will act out the event

that occurred that night.”

A woman, Millie, and a man, Jeffrey, volunteer to help with the experiment,

and after being introduced, they are invited to sit at the table.

“Millie, I want you to play the role of my wife, Janie, and Jeffrey, will you

please pretend you are me. I will play the role of Charles Austin. Your task

36

is to act out the actions in the story as it unfolds. Do you understand your

roles?”

They nod in the affirmative.

“Have you ever seen the Mt. Kenya Paradox?” I ask, playing the role of

Charles Austin.

Millie and Jeffrey say “No.”

I produce a deck of cards and a small pouch. I give the cards to Millie and

then leave the pouch on the table.

“Please give the cards a good mixing.”

Millie does this.

“Jeffrey, please open the little purse and dump out the two red and two black

poker chips you will find inside. Please put a red chip in front of Millie’s

right hand and a black chip in front of her left. Good! Now, arrange the two

remaining chips in front of you in the same way.”

The deck of cards is divided in two and a packet placed face-down in front

of both of the helpers.

“Now I want you to pretend there is an imaginary line – the equator –

dividing the table. Millie, you are north of the equator, and Jeffrey, you are

south of the line.”

“Your task is to take the top card, face-down, off your packet and then

follow your intuition. If you think the card is black, place it face-down next

to the black chip, or if you think the card is red, start a red pile near the red

chip. You might want to keep the piles fairly even – but don’t try to

calculate. Just follow your hunches.”

Millie and Jeffrey follow these instructions and take this assignment

seriously. They distribute their cards and then tidy up their piles in front of

the colored poker chips.

“Do we all agree that you had free choice in distributing the cards?”

37

I ask.

“Yes,” the helpers agree, nodding affirmatively.

“Now we will cross the equator,” I say, in an ominous voice, supposedly

replicating that of Charles Austin.

Standing at one end of the table, I say to Millie, “Please do as I do. Be neat

and careful.”

I carefully pick up Jeffrey’s black pile of cards in my left hand, and then

cross my right hand over the imaginary equator line and pick up Millie’s red

cards in my right hand. I move my hands apart and carefully deposit the

cards on the table. Both piles have crossed the equator – their locations are

switched. I then pick up the poker chips and reverse their positions. The

colored chips follow their packets.

Millie duplicates this process with the other packets. She exchanges packets

and poker chips. Jeffrey’s cards are in front of her, and her cards are now in

front of Jeffrey. Both have crossed the imaginary equator line.

“Now, we will audit the results of crossing the equator. Each of you will

please go through the other’s person’s red cards and count the number of

black cards – or misses – in the pile.

Millie and Jeffrey each pick up the red pile of cards and count the misses –

the black cards which appear in that pile.

“Millie, how many did your partner miss?”

Millie says, “Only three.” She is wide-eyed.

“And, Jeffrey, how many did your partner miss?” He is stunned. “Just

one.”

This is the same amazing experience my wife and I had that night at the Mt.

Kenya Safari Club.

But there is more.

38

Charles said to us, “I must take your leave, but after I go, I would like you to

examine your remaining selections.”

He bowed in a dignified and friendly manner and bid us goodnight in

Swahili – “Lala Salama.”

We looked at each other and then with a strange sense of anticipation, turned

over the remaining piles of cards and spread them out on the table.

“Please do that now. What do you find?”

Millie blurts out “No Way!” as all the cards on the table are black cards.

“Do you think the equator has something to do with this?”

Explanation

The cards are honestly shuffled, and then the deck is unshuffled using the

‘Rounders Principle.’ The deck can instead be switched. The business of

opening the pouch and emptying the chips on the table gives superb

misdirection for the unshuffling procedure or for the deck switch.

The use of ‘rounders’ or a deck switch can be eliminated if this effect is

done in an informal setting, and you have a decent false shuffle. However,

the effect is stronger if the participants honestly mix the cards.

The cards are separated by color in the standard O.T.W. fashion. Assume

the red cards are on top. Take three black cards, and insert them in different

places among the top twenty-six red cards. Then place on red card in the all-

black section.

The reason for this is to create a few misses during the first revelations. Bob

Neale told me this was the approach Paul Curry used in his original

instructions.

Now assume two persons are sitting across from each other at a card table.

Assume Millie is north and Jeffrey is south.

39

The cards are spread and separated. Millie is given the top twenty-eight

cards (twenty-five red and three black), and Jeffrey is given the twenty-three

blacks and one red.

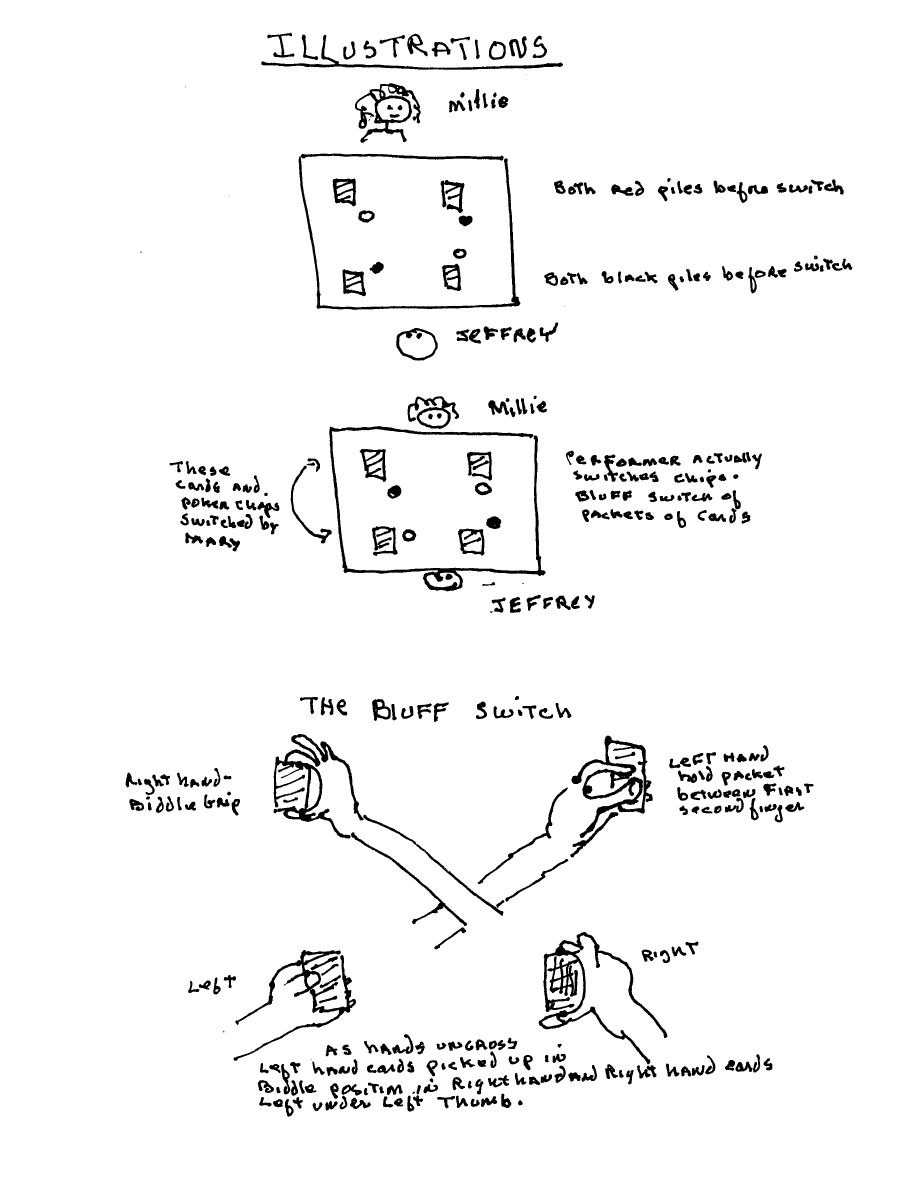

The poker chips are arranged so that the red chip is in front of Mary’s right

hand, and the black chip is in front of her left hand. The chips are placed

before Jeffrey in the same fashion. Right hand is red, and left hand is black.

(See diagram.)

Now the cards are distributed by both parties with instructions to make the

piles fairly equal.

The situation is that Millie has two piles – both of which are red (with a few

blacks in one pile) and Jeffrey’s piles are both all black cards with one

exception.

Here comes the only move. This is not a sleight. In Stuart James’ Lexicon,

a move is a subtlety that occurs and not a procedure like a pass or a top

change.

The piles of cards in front of the participants will apparently be switched.

The justification for this movement are two. First the equator crossing

maneuver is the theme of the story, and secondly, you are inviting the

partners to audit the other person’s results.

The switching of the packets in the performer’s hands never happens, while

the switch that the woman makes is fair. The result is that the piles are

relocated – deceptively – so that the surprising separation occurs.

A few words on this devilish move are relevant. Dr. Daily published a move

(Daily’s Delight) in which one card was apparently switched for another in

an ace assembly card trick, but in fact, the switch never happens.

The way I apply this subtlety is a little different. Let me go through the

mechanics and then make a few comments. (See illustrations)

When you stand at one end of the table, your right hand picks up the packet

of cards on the right corner of the table. This packet has all black cards, but

there is a red chip next to it. These cards are openly placed by the right hand

between the first and second finger of the left hand.

40

Now the right hand crosses over the left wrist and picks up the packet of

cards on the left side. This packet has all red cards, but there is a black chip

next to it. The cards are held in biddle position – right thumb on the bottom

and right fingers on top.

Now the hands will be uncrossed in a calm and indifferent manner. You do

not look at your hand, but at the participants as you explain what they are to

do. When the hand meet, the right-hand cards are taken quietly by the left

thumb, and the right thumb and right fingers pick up the left pile and both

hands move apart and deposit their cards on the table.

This is one of those moves where you almost fool yourself.

There is no ‘heat’ on this procedure. No one knows what is going to happen,

and everyone is intrigued by the story.

You now pick up the poker chips – one in each hand – and the hands cross

back over and place the chips in front of their appropriate pile. The colored

chips are switched.

These moves are done in an innocent, natural fashion. The results are that

the colored chips now correctly indicate the colors of the cards next to them.

There it is. This small miracle is accomplished with one uncrossing of the

hands.

LaLa Salama! (In Swahili, “Sweet dreams!”)

And Good Luck!

Barrie Richardson

41

42

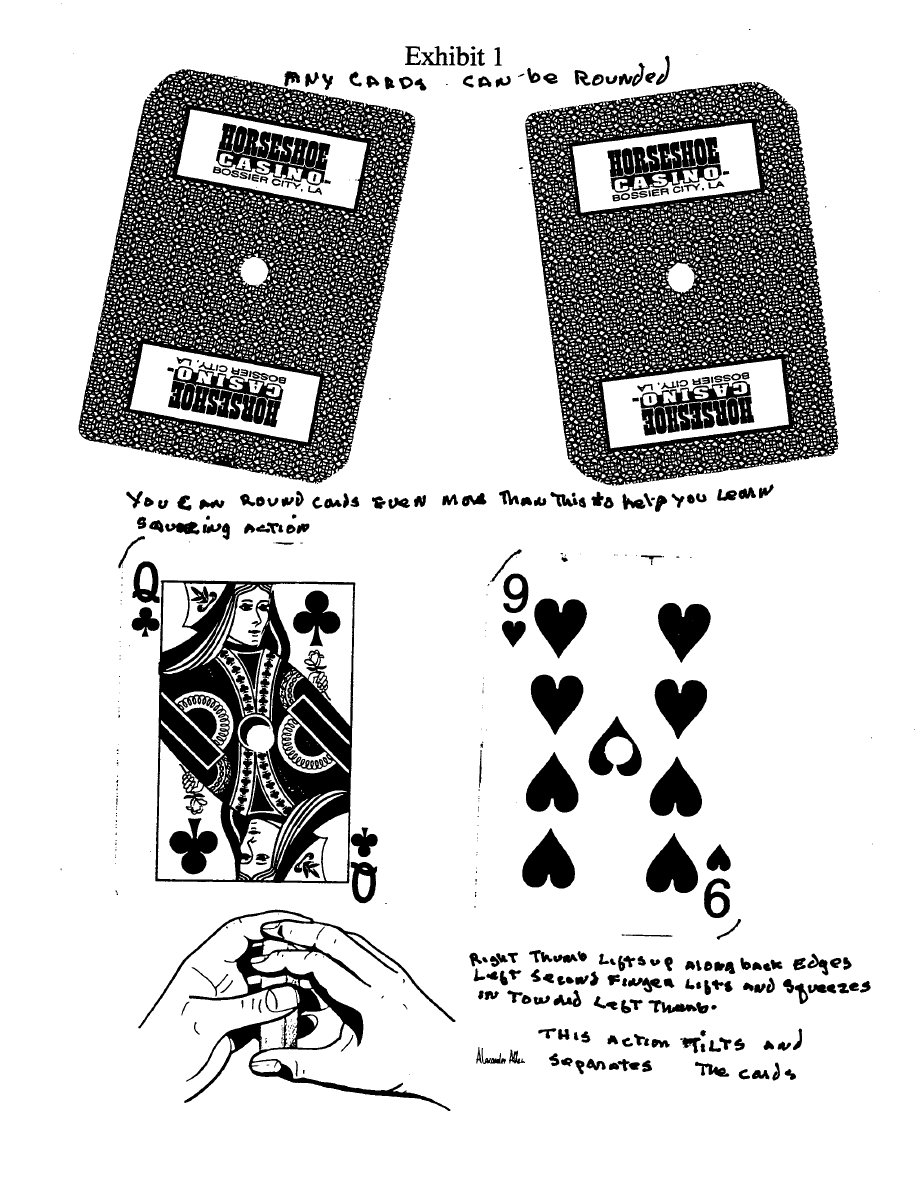

Rounders

A Technology for Unshuffling Cards

‘Rounders’ is the name I have given to cards whose corners have been

rounded off. The cards can be thoroughly shuffled, and then separated

cleanly in one motion that looks like you are cutting the cards.

You can prepare the deck of cards yourself. All the red cards are rounded on

one diagonal, and the black on another. This can be accomplished with a

pair of sharp scissors.

To make the separation, hold the cards vertically in the left hand with the

long sides horizontal (see illustration). Now, lift up the right hand and grip

the inner top corner with your right thumb and the outer corner with the tip

of the second finger.

A slight squeezing by the thumb and second finger will cause all the cards of

one color to move forward at a slight angle which you immediately feel. In

one clean action you will strip all these cards out. They can now be

overhand shuffled or if you wish, be given a cut.

Good Luck!

Barrie Richardson

43

44

Devious Deck Switch

Introduction

The deck switch I am about to describe was originally designed for platform

use, but to my surprise, I have found that it works equally well for standing

and for close up. The switch involves the card case, an approach that has

been used in the past, most notably by Al Koran, who described his method

in Professional Presentations. Mine is completely different. Her is how it

looks.

The Presentation

The performer hands out a pack for shuffling. While this is being done, he

stands and waits, casually holding the empty card box. When the pack is

returned, the performer seemingly places the box on the table and begins the

trick. However, in the process, the shuffled pack has been secretly switched

for a stacked one.

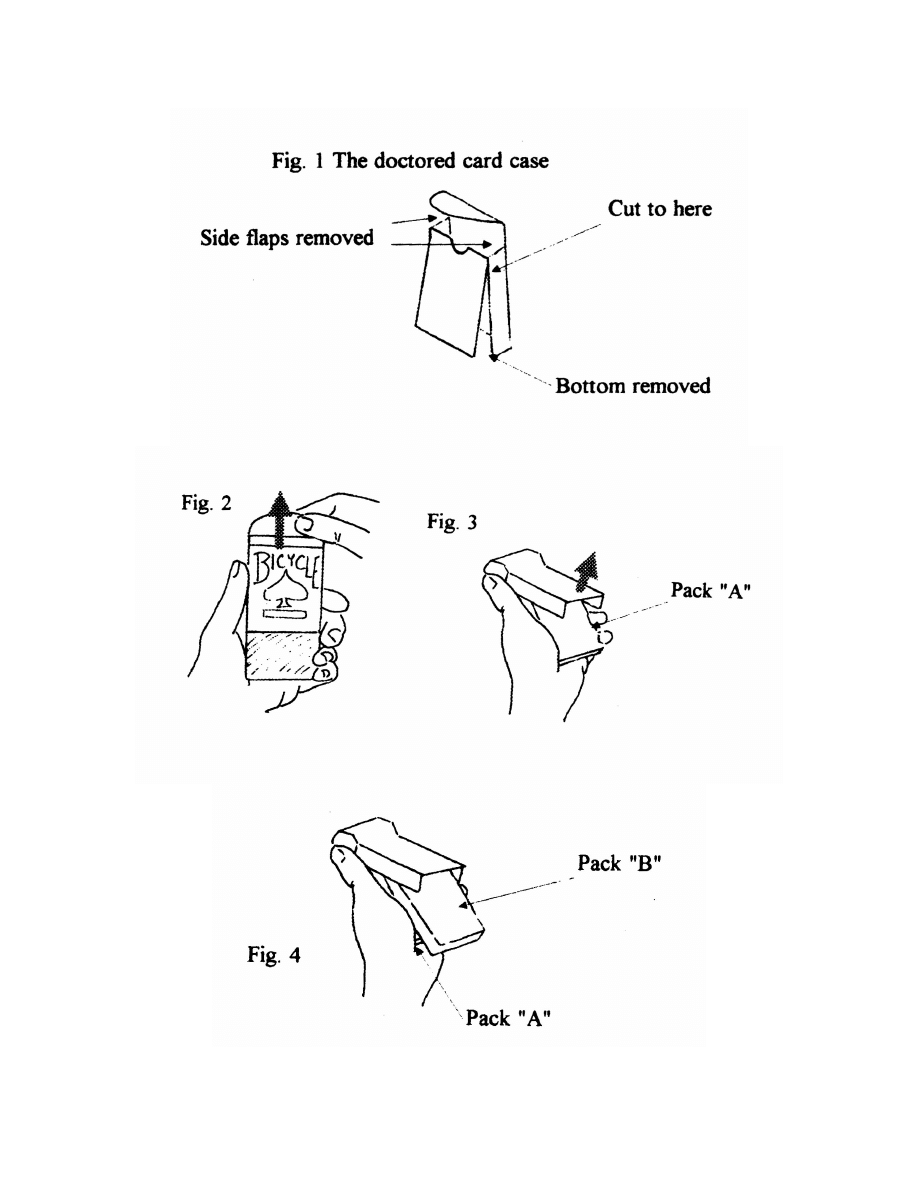

Explanation

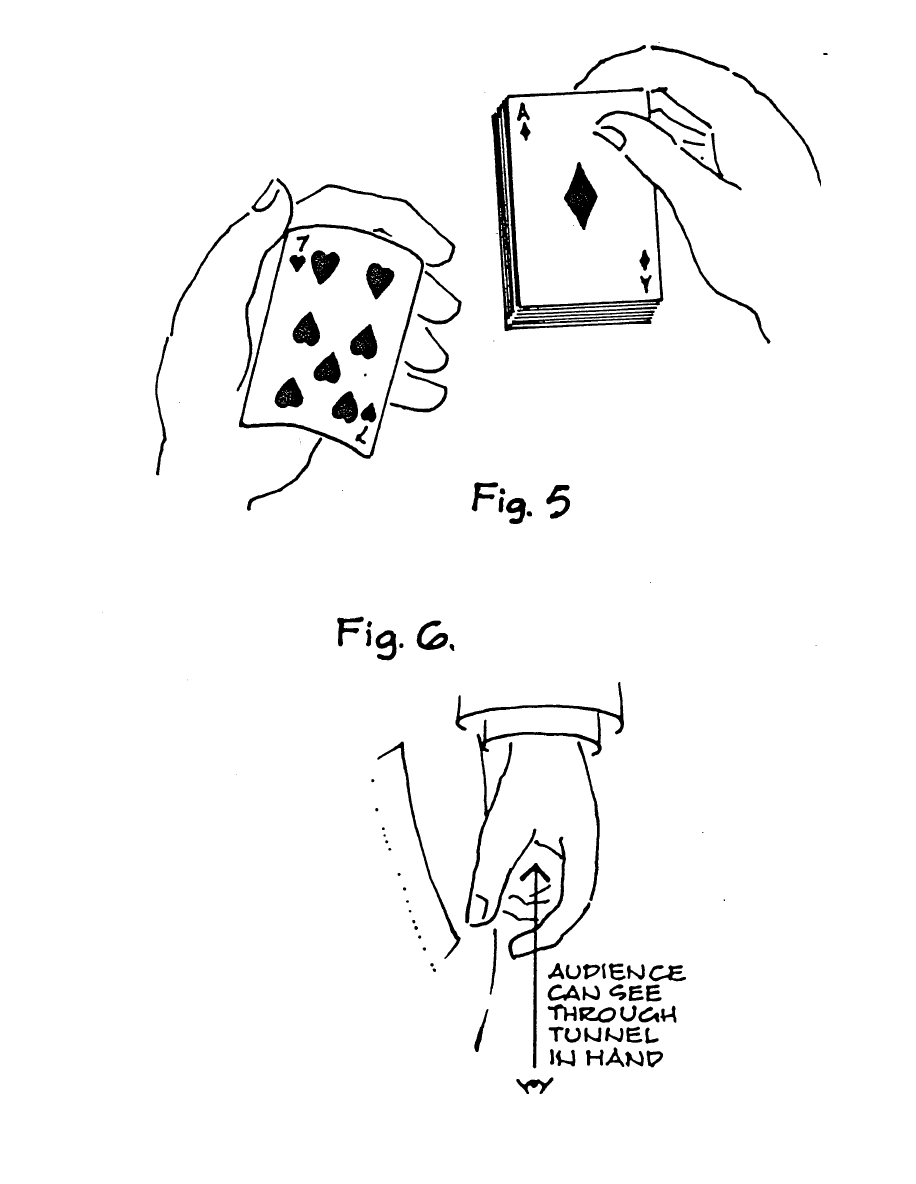

First I will explain how to doctor the card box. For the purposes of this

description, I will assume that you are using a pack of Bicycle Rider backs.

This is simply to enable me to refer to the various parts of the box. If you

examine such a box, you will note that:

1. The flap is attached to the front – the face with the ace-of-spades logo.

2. The rear – the part with the semicircular cut out – has a printed replica of

the card’s back design.

The first step in preparing the box is to cut off the two little folding side

flaps/tabs at the open end. When you have done this, neatly cut out the

entire bottom end of the box removing it completely. Next, turn the box so

the card-back-design side is upwards, and starting from the bottom, cut

along the folds at each long edge, stopping at a point about half an inch from

the open end. Figure 1 shoes the result.

45

If you hold this mutilated box as you normally would and insert a pack, the

said pack will slide/drop straight out at the other end, there being nothing to

retain it – not even any friction from the sides.

The case is now ready to use. Insert the pack that you wish to switch in (A).

Do not close the flap. Place the box on the table where it cannot be seen,

and then put the uncased pack (B) that will be shuffled on top of it.

While pattering, reach down with your left hand (unless you are left-handed,

in which case, you may want to use your right hand. Not being left-handed,

I do not know.) and pick up both packs together. Then take the loose one

(B) with your other hand, and pass it to a spectator to shuffle. Some people

may be tempted to make a pretence of tipping the cards from the box.

Experience has shown that this is not really necessary. People are not

burning your hands when you take out the pack. They see you pick

something up, begin to walk towards somebody, hand that person a pack of

cards and stand there holding the case. So, in their mind’s eye, they ‘saw’

the cards come out of it. Why else would it be there?

Ensure that when you pick up the case, you do so in such a way that it will

have the doctored back-design side nearest to your palm and the flap end

pointing away from you. Do not adjust the box’s position after you have

given the pack to the assistant. Doing so will draw attention to it and make

it seem important.

The following may appear to directly contradict what I have just said, but it

does not really. Having warned against adjusting the position of the box, I

am now going to tell you to do precisely that. However, the nature of the

adjustment is relaxed and appears to be no more than a casual toying with

the object while you await the return of the pack.

It does not look like a major repositioning in order to get ready for a move.

This is what happens. The hand holding the case turns palm inwards until it

is in a vertical plane. The other hand then takes hold of the flap between the

forefinger and thumb and pulls it upwards for two or three inches. Figure 2

shows the action taking place. Only the case moves; gravity causes the

cards to remain where they are. Note how the curled fourth finger stops

them from falling by pressure against the palm.

46

The hand drops casually to your side so that the box’s open end is pointing

directly towards the spectators. It appears empty because the white ends of

the cards simply look like the inside bottom of the case. Equally important

is that it sounds empty when it is touched.

Accept the returned pack (B) after shuffling. Take it from the spectator in a

Biddle grip, i.e. from above with the fingers at the outer short end and the

thumb at the inner. The situation now is that you apparently have the pack

in your right hand and the box in your left. You should be well away from

any tables.

Realize that you need to free your right hand on some pretext, e.g., to get

something from your pocket, shake hands with a spectator or whatever. In

order to do so, you will momentarily have to deposit the cards in your left

hand. As you bring the pack across, the right fingers accidentally bump

against the case at its outermost end. In fact, this action covers adjusting it

to the Figure 3 position. The second pack (A) is masked by your hand, and

all the audience can see is the box.

The right hand’s pack is apparently placed under the box. In fact, it is

inserted into the open bottom and held as in Figure 4. A perspective illusion

similar to that which makes the well-known tilt move possible gives the

impression that it is beneath. The right hand leaves it there and moves away

to do whatever overt action provided the excuse to temporarily deposit the

cards. Afterwards, it returns and apparently removes the empty box and gets

rid of it – either into the pocket or onto the table. In fact, what really

happens is that the right thumb rests against the inner end of the upper pack

(B) and the fingers against the outer end of the box – a sort of elongated

Biddle grip. Then, as the case is lifted away, the thumb pushes the pack (B)

inside, leaving the stacked pack (A) in full view on the left palm. The

switch is completed.

Good Luck!

Barrie Richardson

47

48

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Barrie Richardson Impromptu Card At Any Number

Barrie Richardson Astonishing Rice Jar Suspension

Barrie Richardson There Are Two Sides To Every Prediction

Barrie Richardson Impossible Knot Routine

Barrie Richardson Impromptu Card At Any Number

Barrie Richardson Optical Brainwave Slow Motion

Richards B., TECHNIK USŁUG KOSMETYCZNYCH, ZDROWIE

My ONI, Richard Hoggart

KUZG Poglady Richarda Floridy

barrier islands Reinson

Nie wolno czekać aż będzie za późno (rozmowa z Richardem Perle 08 03 2003)

21 Wyznaczanie pracy wyjścia elektronów z metalu metodą prostej Richardsona

spr0708, Oblicz metodą Romberga wykonując dwie iteracje ekstrapolacji Richardsona

emocje i motywacje - zajęcia 1, RICHARD J

Metoda dwupunktowa opiera się na odkryciach dwóch znakomitych lekarzy dra Richarda?rtletta

Lab 21, MIBM WIP PW, fizyka 2, laborki fiza(2), 21-Wyznaczanie pracy wyjścia elektronów z metalu met

Magia w dzialaniu Sesje NLP Richarda Bandlera magdzi

Opinie o totalitaryzmie od Richarda Pipesa, opinie historyków do matury (wypracowanie matura rozszer

adding subtle color pattern

więcej podobnych podstron