IN G U N N L U N D E

Хвалити и птьти и прославляти: Epideictic Rhetoric

and Cyril of Turov’s Metadiscursive Reflections

Das Geheimnis der Anziehungskraft der christlichen

Predigt und eine wichtige Bedingung ihres Erfolges lag,

neben dem Wirken des von Christus ausgehenden

Geistes, in dem einen und vielen, das sie von Anfang an

umfaßte. [...] Sie war neu und alt, jenseitig und

diesseitig zugleich; sie war hell und durchsichtig und

wiederum tiefsinnig und geheimnisvoll; sie war

statutarisch und doch über jedes Gesetz erhaben; sie

war eine Lehre und doch keine Lehre, eine Philosophie

und doch etwas anderes als eine Philosophie.

Adolf von Hamack, Die Mission und Ausbreitung des Christentums

Among Aristotle’s speech genres the epideictic (genos epideiktikon) occu

pies a special position. It presents specific problems of definition and char

acterisation, and has generally not found favour with critics. If, however,

the epideictic genre may seem to have been restricted to a rather narrow

field (the oratory o f praise and blame) in early rhetorical theory, in rhetor

ical practice it had actually moved far beyond such generic limits. Modem

assessments have become increasingly aware of the broader implications of

the epideictic. “Aus rhetorischer Perspektive,” says Stefan Matuschek, “ist

alle Dichtung E[pideiktische Beredsamkeit].”1 The relationship between

the epideictic and literature (and poetry in particular) is no doubt both im

portant and revealing, but it is also problematic and not easily defined. The

connection between them is particularly emphasised in Theodore C. Bur

gess’ Epideictic Literature (1902), as is already evident in the title o f the

book. Laurent Pemot, the author of a recent two-volume study of the eulo

gy in the Greco-Roman world (1993), justly questions Burgess’ wide defi

1 Stefan Matuschek, “Epideiktische Beredsamkeit,” Historisches Wörterbuch der Rheto

rik, vol. 2, ed. G. Ueding, Tübingen 1996, col. 1259.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

ow

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stellen

bo

sch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

nition o f the epideictic (“a style of prose in which omateness is introduced

in a conscious effort to please”),2 but emphasises in his own exposition the

historical continuity between the Greek poetic tradition and epideictic rhet

oric, a continuity which, he explains, is partly due to direct influence (imi-

tatio) and partly to their common intention (“la célébration”).3 A general

point o f contact between epideictic rhetoric and the rather vague notion of

“poetry” is, to my mind, that they both imply a specific type o f verbal ap

proach. In this respect, it is probably more correct to speak o f a predomi

nantly “poetic” use o f language in the Jakobsonian meaning o f the term,

and not of “poetry.”

In this essay, I shall focus on a few characteristic aspects o f epideictic

rhetoric, with a view to establishing the significance o f the epideictic within

the homiletic context. I am concerned here not so much with the historical

development o f the epideictic genre and its relation to the forensic and de

liberative; rather, for my present purposes, I have chosen to view the epi

deictic as a set o f characteristic rhetorical features at work in texts which

may belong, in principle, to a number o f different genres or literary forms.

In the second part o f the article, I present an analysis of “metadiscursive

statements” in the twelfth-century Russian bishop Cyril o f Turov’s ser

mons. The purpose o f the analysis is twofold: against the background o f the

various theories and views o f epideictic rhetoric discussed in the first part,

1 w ill try to define, on the one hand, what metadiscursive statements may

reveal about the content and intentions of the sermon as seen by Cyril, and

to see, on the other, if they fulfil any particular functions in Cyril’s rhetoric

when taken in the context o f the orator’s overall rhetorical design.

E p id eictic rhetoric

In his classification o f different types or classes (eide) o f rhetoric, Aristotle,

whose Rhetoric represents the earliest attempt at a systematic description

o f “the art of persuasion” from a functional point of view, identifies several

characteristic features o f the genos epideiktikon.4 Aristotle’s constant atten

2 Theodore C. Burgess, Epideictic Literature, (= Chicago Studies in Classical Philology,

3), Chicago 1902, p. 215. Cf. Laurent Pemot, La rhétorique de l ’éloge dans le monde

Gréco-Romain, (= Collection des Études Augustiniennes, Série Antiquité, 138), Paris

1993, pp. 10-11,41.

3 Pemot 1993, p. 636.

4 References are given in the text. I have used Rudolf Kassel’s edition, Aristotle, Ars rhe-

torica, ed. Rudolf Kassel, Berlin 1976. English translations are taken, with minor altera

tions, from Aristotle 'On Rhetoric’: A Theory o f Civic Discourse, transi, with introduction,

notes, and appendixes by George Kennedy, New York and Oxford 1991.

98

Ingunn Lunde

Scando-Slavica, T om us441998

D

o

w

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stellen

bo

sch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

Cyril o f Turov and Epideictic Rhetoric 99

tion to the functional aspect of rhetoric is evident from the fact that his dis

tinction between the three classes is made on the basis of the hearers’

(akroatai) position (13 , 1358a-1358b). Whereas the listener o f the forensic

and deliberative genres acts as “a judge,” a krites, the audience o f the epi

deictic is defined as theoroi, a term variously translated as “observers,” “on

lookers,” or “spectators” (I 3, 1358b).5 His or her role may still resemble

that of a krites, but the theoros o f epideictic oratory does not judge the le

gitimacy or truthfulness o f the subject, but how it is presented (1 3, 1358b;

П 1 8 ,1391b).6 Attention is thereby directed towards the speech act; in mod

ern terms, one might say that the performative aspect o f epideixis focuses

on the text/expression itself {установка на текст/выражение). This

has led to the view mentioned above o f the epideictic as the literary, or even

poetic genre p er se, but also to a seemingly biased focus on the ornamental

qualities o f the epideictic,7 which, in turn, has given rise to the tendency of

5 Cf. the discussion of the term in Christine Oravec, “Observation in Aristotle’s Theory of

Epideictic,” Philosophy and Rhetoric 9, 1976, pp. 162-174. Oravec studies the possible

meanings of the term theoria and concludes that it can imply a combination of several

functions which epideictic rhetoric may have on the listener: “the aesthetic function of epi

deictic is the audience’s perception of the sensory qualities of the speech itself; [...] the

judgmental function is the audience’s critical apprehension of the artistic and intellectual

abilities of the speaker in his presentation of praiseworthy and blameworthy objects; [...]

the comprehensive function occurs when the audience receives new insights from the

speaker’s application of audience-supplied maxims and values to events and persons within

their own experience”; Oravec 1976, p. 163.

6 “A spectator is concerned with the ability [of the speaker]” (ο δέ ττερί της δυνάμ,εω«; δ

■θεωρός, I 3, 1358b). Some editors (e.g. Kassel) take this sentence as an insertion into the

text by a later reader. In the introduction to chapter 18 of book II (most of which Kassel

also regards as interpolated), Aristotle returns to the question of the hearer's position and

holds that in epideictic rhetoric, the speech is composed for the spectator as a judge (Π 18,

1391b). The problem of the hearer as “judge” is not essential to my argument here, how

ever; the crucial point is that attention is drawn towards the speech itself. Whatever one

makes of the verb epideiknymi (active voice) or epideiknymai (medium/passive voice) —

whether it is understood as referring to the rhetorician, who demonstrates his own ability as

a speaker, to the rhetorical effect of the speech itself, or to the representation of the charac

ters or objects (e.g. a city) portrayed in the speech— the function of the logos of epideictic

rhetoric is other than in both deliberative and forensic speech.

7 Cicero relates the genus demonstrativwn to delectare, rather than to movere or docere,

defining it as “a show-piece designed to give pleasure” (ad inspiciendum delectationis

causa. Orator, 11, 37). Cicero, however, clearly acknowledges the significance of the

genre; as his meticulous German commentator, Wilhelm Kroll remarks, “Die beiläufige

Ausführung der Gründe, wovon das γένος έτηδεικτικόν von keinem Redner vernachläs

sigt werden dürfe, dehnt sich so aus, daß die abgebrochene Konstruktion [i.e., non quo

neglegenda sit, est enim...] nicht wieder angeknüpft wird.” Cicero, Orator, ed. O. Jahn,

commentaries W. Kroll, Berlin 1913, p. 45.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus441998

D

o

w

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stellen

bo

sch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

100 IngunnLunde

disregarding its possible significance for the advancement and production

o f meaning.

These two tendencies are, to a certain extent, reinforced by Aristotle’s

definition and characterisation of the object of the speech (telos, 1 3 , 1358b)

and, by implication, o f its subject matter. The epideictic, in contrast to the

forensic or deliberative genres, does not deal with questions o f justice and

politics, that is primarily with what is right or wrong, reasonable or unwise,

but with the noble or virtuous (to kalon) and its opposite, the wicked or

shameful (to aischron, 1 3, 1358b). The actions (praxeis, 1 9; 1368a) of the

characters portrayed are already “agreed upon” (homologoumenai, I 9,

1368a); they are, in a sense, a priori “true,” whilst the orator’s task consists

in representing them to the audience in the best possible manner, “to clothe

the actions with greatness and beauty,” as Aristotle puts it (19 , 1368a). Fur

thermore, while forensic speech deals with past actions, and deliberative

rhetoric with the future, in epideictic oratory the focus is on the present (1 3,

1358b), and by implication, on the very moment when the speech is deliv

ered. As for what is being said, the epideictic orator is free, as it were, o f

the quest for “originality” and “creativity” in the conventional sense o f

these terms. In the words o f Isocrates, “we should admire and honour [...]

not those who seek to speak on subjects on which no one has spoken be

fore, but those .who know how to speak as no one else could (τούς ούτως

έττισταμένους ει/ττεΐν ώς ούδείς α ν ά λ λ ο ς δΰναιτο).”8 Against this

background w e should not be surprised to learn that the most important rhe

torical device of epideictic speech, according to Aristotle, is auxesis, or am-

plificatio (1 9, 1368a; II 18, 1392a). Significantly, amplificatio is regarded

by Aristotle first o f all as a form o f argumentation, not as mere ornament.

The aesthetic aspect o f epideictic discourse is doubtless one of its most im

portant features, but this should not lead us to regard the epideictic as being

deprived o f content or meaning, as “une sorte de gastronomie de la pa-

role.”9 Pemot’s characterisation, “L’éloquence épidictique est non seule

ment une fête des mots, mais aussi une fête du sens moral, esthétique et

8 Isocrates, Panegyricus, 10, (transi. George Norlin, Loeb Classical Library, 209). I do not

suggest that Isocrates is here alluding to the idea that we find in Aristotle of the audience; as

a “judge”; he rather presents his view of how “the philosophy which has to do with ora

tory” (την περί τους λόγους φιλοσοφίαν) could make its greatest advance (namely “if

we should admire and honour...”). Isocrates is apparently speaking of oratory in general,

' and not explicitly of epideictic rhetoric in particular. However, his ideals of “the highest

kind of oratory” (4), as he calls it, are clearly those of the epideictic, cf. Norlin’s general

introduction to his translation, p. xxiv.

9 Pemot’s expression, but not his view; cf. Pemot 1993, p. 660.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

ow

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stellen

bo

sch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

Cyril o f Turov and Epideictic Rhetoric

101

religieux,”10 is interesting in this respect because it emphasises, on the one

hand, the combination of possible moral, aesthetic, and religious (but not

“Christian” in this context) functions, whilst it retains, on the other hand,

the element of epideixis and the performative and celebratory functions by

referring to the delivery o f the speech as a “fête.”11

Christian hom iletics

The question of how to understand and define the nature o f the two ele

ments discussed above— the homologoumena, or a priori “truth,”12 o f the

subject matter o f the speech, and amplificatio as its main rhetorical tool—

are of crucial importance when we turn to Christian homiletics. “Christian

homiletics” is far from being a precise, agreed-upon label applied to a def

inite genre, or corpus o f texts. I am concerned in this instance, however, not

with “the history o f Christian preaching,” but with the rhetorical character

istics o f what w e may call, following Averil Cameron, a Christian dis-

10 Pemot 1993, p. 662.

11 As mentioned earlier, “celebration” is also one of the aspects (the intention) which,

according to Pemot (1993, p. 636), links the epideictic to the poetic tradition.

12 The concept of (a) “truth” is complex, and, of course, not unambiguous. According to

George Kustas, Studies in Byzantine Rhetoric, (= Analecta Vlatadon, 17), Thessaloniki

1973, in the development of early Byzantine rhetoric, one may observe a shift from dealing

with the probable or feasible (eikota) to dealing with “truth,” a shift which he regards as

essential for the “transformation of the function of oratory” (Kustas 1973, p. 26) with the

Christian preachers. The theoretical support for this transformation, Kustas states, is found

in the Stoics’ view of rhetoric as “the art of speaking well” (episteme tou eu legein), by

which they meant “speaking the truth” (to alethe legein; this maxim has been preserved in

a number of rhetorical and philosophical texts, see Kustas 1973, p. 27, n. 1 for specific ref

erences). This definition also represents a departure from (or at least a shift in emphasis

from) the Aristotelian stress on clarity (sapheneia) as the main virtue of rhetorical speech.

Kustas 1973, pp. 26, 63-100, regarding asapheia (obscurity) as a “key principle of Byzan

tine rhetorical theory,” seems to overstate his case, cf. the critical remarks in Margaret Mul-

lett, Theophylact o f Ochrid: Reading the Letters of a Byzantine Archbishop, (= Birming

ham Byzantine ând Ottoman Monographs, 2), Aldershot 1997, p. 156. Mullett, quoting

John Sikeliotes’ cautious statement “not every form of obscurity (asapheia) is blame-wor

thy” (Christian Walz (ed.), Rhetores Graeci, Stuttgart 1832-1836, vol. 6, 203.5, quoted in

Mullett 1997, p. 156) concedes, however, that “there is some evidence for an increased

interest in asapheia in the tenth and eleventh centuries and an awareness of its literary pos

sibilities”; Mullett 1997, p. 156. What is interesting in this from our present point of view

' is precisely what Mullett calls the “literary possibilities” of an aesthetics where rhetorical

devices traditionally associated with the concept of asapheia (for example, catalogues or

clusters of parallelisms and synonymic couplings) are seen as decisive for the creation of

meaning in a text.

_

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

102 Ingunti Lunde

course,13 and in particular with aspects o f epideictic rhetoric which may

contribute to our understanding and adequate analysis o f Cyril o f Turov’s

sermons.

“Christian discourse,” according to Cameron, “is about revelation: it ap

peals to hidden truths.”14 The Christian orator is constantly confronted with

the problem o f referring to and representing divine or sacred reality by

means o f a human discourse. Christian writers, wrestling with the question

o f human language’s capability of “describing the indescribable,” are fully

aware o f the linguistic problem of representation. At the same time, w e can

observe their intense preoccupation with the necessity o f verbal interpreta

tion, definition, and description.

The problem o f representation may, o f course, be used creatively, and

explored as a means o f intensifying the rhetorical effect, in fact, as a meth

od o f amplification. By describing and depicting Christ, God, or other cen

tral elements o f the Christian faith, while at the same time presenting the

utterance itself as inadequate, the orator may successfully exploit the pow

erful “rhetoric o f paradox,” expressing the inexpressible, praising the one

who exceeds all praise. But the ultimate aim of this intense activity of in

terpretation, definition, and description, however imperfect, is to give

meaning or meaningfulness to the mysteries and paradoxes o f Christianity.

Incidentally, as Jaroslav Pelikan has observed, negative theology and the

language o f apophaticism implied not only a limitation on but also a liber

ation o f the mind, allowing, for instance, the Cappadocians to explore a

number o f possible ways o f knowing God.15

The possible cognitive aspect of rhetoric has often been ignored;16 not

without reason, it seems, since it has proved to be rather problematic to de

13 For a comprehensive study of this broad, yet fruitful concept, see Averil Cameron,

Christianity and the Rhetoric of Empire: The Development of Christian Discourse,

(= Sather Classical Lectures), California 1991.

14 Cameron 1991, p. 47.

15 Jaroslav Pelikan, Christianity and Classical Culture: The Metamorphosis o f Natural n

Theology in the Christian Encounter with Hellenism, (= Gifford Lectures at Aberdeen,

1992-1993), New Haven and London 1993, pp. 57-73. On some implications of the

apophatic approach as reflected in Christian rhetoric, cf. my forthcoming “The Rhetoric of

Apophaticism,” (presented as a paper at a symposium on “Apophaticism in Theology,

Rhetoric, and Literature,” Bergen 1997), to be published in a conference volume edited by

Henny Fiski Hagg.

16 See, however, two recent attempts, which treat rhetoric consistently as a “way of know

ing” and as capable of meaning-generation: George Kalamaras, Reclaiming the Tacit

Dimension: Symbolic Form in the Rhetoric of Silence, New York 1994; and Rodney

Kennedy, The Creative Power of Metaphor: A Rhetorical Homiletics, Lanham 1993.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

Cyril o f Turov and Epideictic Rhetoric

103

scribe and to analyse. It is clear that we are dealing with a kind of knowl

edge distinct from the traditional logical or philosophical experience. The

tendency to regard rhetoric as the opposite o f philosophy, or o f faith,17 typ

ical in early Christian writers and their pagan contemporaries, as well as in

their modem interpreters, has certainly not facilitated the study of the role

o f rhetoric in Christian homiletics. However, it is interesting to note that

most Christian writers arguing for the primacy o f faith over both logic and

rhetoric18 do so in an eminently rhetorical fashion. This is not only an illus

tration of how the discrepancy between rhetorical theory and practice is fre

quently overlooked; it is also o f significance for the analysis of rhetoric in

Christian homiletics, where the role played by other, prior texts, which pro

vide standards o f writing, is often neglected in the study o f the transmission

and implementation o f rhetorical techniques. More importantly, one must

bear in mind the special character of the cognitive activity involved. Chris

tian orators are, by and large, not anti-intellectuals, whatever they proclaim

about themselves and their relation to (secular) learning. In their theologi

cal inquiry, however, they do not seek to define and describe sacred matters

in a way that would impose limits and boundaries on the subject o f inves

tigation or representation. Rather, they proceed by way o f revelation and

disclosure, presenting religious truth in the form of symbols, metaphors,

and paradoxes.19

At the root o f this approach lies an awareness o f the fundamental differ

ence between “the facts” and “the names.”20 The “facts” or “meanings” are

what w e seek, but the “names” or “words” can never provide exact knowl

edge about them. The orator’s task is to present to the audience glimpses o f

truth, o f sacred reality. Meanwhile, the idea o f language as a system of

signs gives additional force to the significance and role o f rhetorical devic

es such as metaphors, symbols, or paradoxes. These devices are all part o f

the amplificatio at work in Christian homiletics. Rhetorical amplification

must be understood here not solely as a stylistic device, but as an essential

17 For a comprehensive and insightful discussion of the problem, see Frederick W. Norris,

“Of Thoms and Roses: The Logic of Belief in Gregory Nazianzen,” Church History 53,

1984, pp. 455-464, and, more recently, Frederick W. Norris, Faith Gives Fullness to Rea

soning: The Five Theological Orations of Gregory Nazianzen, introduction and commen

tary F.W. Norris, transl. L. Wickham and F. Williams, Leiden 1991, esp. pp. 17-39.

18 The latter understood chiefly as a negative notion.

19 Cf. Clement of Alexandria’s famous statement in Stromateis, 4.4.21.4: “all the theo

logians [...] have presented the truth in riddles, symbols, allegories, and metaphors” (ττάν-

τες οί ■θεολογήσαντες [...] την δέ άλήθειαν’ αίνίγμασι και συμβόλοις άλλη-

γορίαις τε α ί και μεταφοραϊς τταραδεδώκασι), quoted in Kustas 1973, p. 170, n. 1.

20 See Norris 1991, p. 33-34 for examples from Gregory of Nazianzus.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

o

w

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stellen

bo

sch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

constituent in the process o f making aspects of the truth visible and mean

ingful to the audience. “A good metaphor,” in Richard Lockwood’s words,

“makes a forceful new connection, and that new connection is a new

knowledge.”21

When taken together with the fundamental problems and prerequisites

o f linguistic representation discussed above, such a view of the metaphor,

I would argue, is illustrative o f the function o f rhetoric in Christian homi

letics as a whole. The aim o f the homiletic text is to convey to the audience

a wealth o f different meanings, which together add up to the best possible

representation, albeit an imperfect one, o f the elements of Christian faith.

A wealth o f meanings does not imply the promotion of any meaning. It

goes without saying that there are more or less established limitations and

conventions as for what meanings may and should be advanced within the

context o f a sermon; the essential thing for our present purpose is the fact

that meaning is not a fixed entity.22

Christian literature and Christian discourse make Christians,” says

Averil Cameron.23 When Cyril of Turov was composing his cycle of Pas

chal sermons, Kievan Rus' had already been Christian for nearly two hun

dred years, and w e must assume that although not every member o f the

l\iro v congregation would be a zealous believer, he or she would certainly

define him- or herself as a Christian. Consequently, the orator’s task is not

primarily to convert people, but to nourish their belief. Thus the sermon in

itself has an “amplificatory” aim: it makes Christians “more Christian.”

Dale L. Sullivan has given an excellent characterisation o f the listener’s re

sponse to epideictic oratory, referring to the New Testament notion o f meta-

noia, which is usually translated as “repentance,” but which has the literal

meaning o f a “change o f mind.” What occurs among the audience o f Chris

tian homiletics is “a change o f mind, but the change o f mind here is not a

shift in opinion.”24 Rather, it is “a change of mind in which a new vision of

104 Ingunn Lunde

21 Richard Lockwood, The Reader’s Figure: Epideictic Rhetoric in Plato, Aristotle, Bos-

suet, Racine and Pascal, (= Histoire des idées et critique littéraire, 351) Geneva 1996, p. 87.

22 That many different meanings can be found in a text is not a problem, since the inspira

tion of the scriptures contains far more meaning than we can ever fathom,” George

Kennedy, paraphrasing Origen, On First Principles, 4.3.14, cf. George A. Kennedy,

“Christianity and Criticism,” The Cambridge History o f Literary Criticism, vol. 1: Classi

cal Criticism, ed. G. A. Kennedy, Cambridge 1989, pp. 331-332, p. 334.

23 Cameron 1991, p. 46.

24 Dale L. Sullivan, “Kairos and the Rhetoric of Belief,” The Quarterly Journal o f Speech

78 (3), 1992, p. 328.

Scando'Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

o

w

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stelle

nb

osch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

Cyril o f Turov and Epideictic Rhetoric 105

life replaces an old one,” a favourite topic of Christian orators, drawing on

2 Corinthians, 5,17: “old things are passed away; behold, all things are be

come new.”

M etadiscursive reflections

One of the fundamental characteristics of the epideictic is its strong incli

nation towards self-reflection. Epideictic speech frequently includes com

ments on itself, metadiscursive statements about the content, the functional

aspects or intentions o f the speech.25 Even in Cyril, whose texts are not con

cerned with the theoretical aspects of rhetoric, w e find similar statements.

In the following discussion, I shall take a closer look at these passages.

In Cyril, metadiscursive statements are usually found in the opening or

in the closing passages o f the sermon. Less often, they occur at transitional

points in the text. An example o f the latter is the following passage from the

Sermon on Christ’s Ascension: “But let us leave these things and discourse

on the ascension o f Christ and on the things that happened on the Mount of

Olives” (145); Н ъ си оставльше, о възнесении Христов^ побЪсЪдуим

и яже быша на горЪ ЕлеоньстЬй (V II341, 31-32).26 This kind of state

ment, which is rather infrequent,27 can be o f a very “technical” nature, as

may be seen from my next example, where Cyril concludes the angel’s long

speech to the women visiting Christ’s empty tomb with his own comment:

“Here we have related all that was said by the angel to the spice-bearing

women concerning Christ” (125); Си ж е вся от ангела реченая к мюро-

носицам о ХристЬ съказахом (IV 424, 22-23).

Metadiscursive statements found at the beginning or at the end o f the

sermons are, for our present purpose, more revealing. These self-reflecting

comments are characterised by two general traits: firstly, they often take on

the form of a traditional captatio benevolentiae, and secondly, they serve

25 Lockwood (1996, pp. 69-76) holds that the specific problem of defining the epideictic

and its aim may be one of the underlying reasons for this characteristic feature of the genre.

76 Cyril’s sermons are quoted from Igor P. Eremin, “Literatumoe nasledie Kirilla Tbrov-

skogo,” Trudy otdela drevnerusskoj literatury 13,15,1957/58, pp. 409-426,331-348. Ref

erences are given in the main text with page and line numbers indicated in brackets;

Roman numerals indicate the number of the sermon (I-VIII) according to Eremin’s edi

tion. English translations are taken, with minor alterations, from Simon Franklin, Sermons

and Rhetoric of Kievan Rus', (= Harvard Library of Early Ukrainian Literature, English

Translations, 5), Cambridge, Mass. 1991.

27 In Cyril’s exegetical commentaries they are more frequent; for example, at the points

where Cyril switches from Scriptural quotation to interpretation.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

as a kind o f reference to Cyril’s source(s). These two traits determine what

I shall call the primary functions of the metadiscursive statement in Cyril.

The passage below may serve as an illustration o f a captatio benevolen-

tiae formula in its plainest form:

Мы же, груби суще разумомь и нищи словомь, не по чину, нъ щербо-

похваление вашему празднику списавше, [...] (УШ 348, 30-31)

But we are coarse in our understanding and poor in word, as we write this pal

try praise for your festival [...] (157)

Similar phrases are often combined with a reference to the Scriptures, as in

the next example, which refers to the Gospel text:

Нъ не от своего сердца сия изноппо словеса— в души бо грЬшыгЬ ни

дВло добро, ни слово пользьно ражаеться,— нъ творим повЪсть, възем-

люще от святаго ЕваньгЬлия, почтенаго нам ныня от Иоана Фелога,

самовидьця христовых чюдес. (V I336,5-8)

Yet I do not bring forth these words out of my own heart: for neither good

deeds nor profitable words are bom in the heart of a sinner. No: I take my

story from the holy Gospel of John the Theologian, whom we now revere, and

who was an eyewitness to Christ’s wonders. (135)

The reference to St. John is authentic enough; Cyril goes on to retell the

Gospel account o f the man bom blind according to St. John 9, 1-41. We

find similar examples in other sermons. References to the authority of

St. John, however, or to the “blessed prophet Zacharias,” who is invoked by

Cyril in the Sermon on Christ’s Ascension and asked to “come now in spirit

[...] and provide us with a beginning for our homily” (143); Приди ныня

духомь, священый пророче Захарие, начаток слову дая нам (VII 340,

1), are, o f course, not primarily motivated by any particular attention to bib

liographical detail on the part o f the medieval orator. Cyril may occasionally

(intentionally or not) modify or even misattribute his quotations, and m ay "

expand on biblical passages, or develop them into dramatic dialogues. The

purpose o f the references, when combined with the author’s own captatio

benevolentiae appeal to the audience, is rather the demonstration o f the au

thor’s adherence to the tradition. This, by implication, gives additional au

thority to his own discourse.

106 Ingunn Lunde

Scando-Slanca, Tomus44 1998

D

ow

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stelle

nb

osch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

Cyril o f Turov and Epideictic Rhetoric

107

Cyril’s manner o f referring to the authority o f the Scriptures, or to the

fathers,28 reminds us o f the general significance and role o f tradition in

these texts, and in Orthodox faith as a whole. Yet there are instances where

such traditional formulae seem to have additional functions. In the passage

just cited, John is referred to as “an eyewitness to Christ’s wonders”

(самовидьця христовых чюдес), whilst in the next example, the prophets

and the apostles referred to as Cyril’s sources “bore witness to the living

God” (послушьствоваша о бозъ живі):

Святыя ж е пророкы и преподобный праведники с собою на небеса в

святый в ъ в одт ъ град,— их ж е влаз от богодъхновеньных скажем книг.

Мы бо слову нЬсм творци, нъ пророчьскых и апостолскых въслЪдующе

глагол, иже послушьствоваша о бозгъживтъ, им ж е дух святый въписати

тако повелЪ: верующим на спасение, а неверующим на погыбЪль. (VII

3 4 1 ,1 4 -1 9 )

And Не leads with Him into heaven, to His holy city, the holy prophets and

the blessed holy men, whose entry thereto we shall relate from the divinely

inspired books. For I m yself do not create this narration, but rather follow the

words o f the prophets and o f the apostles, who bore witness to the living God,

and who were bidden to write thus by the Holy Spirit: for the salvation of

believers, and for the destruction o f unbelievers. (144)

The criterion of the eyewitness is a commonplace in historiographical writ

ing from Thucydides onwards. The need to distinguish between fact and fic

tion may, o f course, be relevant in a homiletic context as well. I should like

to suggest, however, that the references in Cyril’s texts to the accepted au

thorities as eyewitnesses form part of his rhetorical strategy o f making his

28 Cf. the opening passage of the Sermon on Low Sunday (ІП): “The Church requires a

great teacher and a wise interpreter to adorn the feast” (108); Велика учителя и мудра

сказателя требуеть церкви на украшение праздника (III 415, 1-2). The passage has

been taken as a reference to Gregory of Nazianzus, whose famous ekphrasis on the renewal

of the spring Cyril adapts and develops in the same sermon. This may well be the case. The

captatio benevolentiae which follows immediately upon this reference, however, “But we

are poor in word and dim in mind, and we lack the fire of the Holy Spirit to compose words

to benefit the soul” (108); Мы же нищи есмы словом и мутни умом, не имуще огня

святаго духа на слажение душеполезных словес (ГО 415,2-4) should not, in my view,

be taken as a proof that Cyril’s has “failed” in his rendering of the spring motif (cf. André

Vaillant, “Cyrille de Turov et Grégoire de Nazianze,” Revue des Études Slaves 26,1950, p.

50). In Vaillant’s view, Gregory is the one who possesses just the “fire of the Holy Spirit”

which Cyril declares to lack. This, I believe, is to read into a traditional formula meanings

which are not there.

Scando-Slavico, Tomus 44 2998

D

o

w

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stelle

nb

osch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

listeners behold the sacred events, persons and places, as if they were them

selves witnesses. The listener of the epideictic is, we recall, a theoros, which

may also be translated as “a witness.” In the rhetorical situation o f the ser

mon, the traditional historiographical eyewitness criterion is transformed

into a device employed by Cyril as a means of overcoming the distance be

tween the here and now of present of reality and the sacred nunc of the holy

events. His ultimate goal is to make his audience participate in and witness

the events which are commemorated “on this day.”29 In Cyril’s homiletic

rhetoric this is accomplished through various means of rhetorical amplifica

tion (rhythmical, semantic, etc.), through the orator’s particular manner of

quotation, through his establishing connections or parallels between central

words and concepts, the rhetorical and poetic effect of which is to make the

audience see the connections and gradually gain insight into their meaning

or meaningfulness. The scope of this essay prevents me from demonstrating

this in detail; let m e confine m yself here to illustrating my point by quoting

the passage which comes immediately before Cyril’s reference to St. John;

here the audience is apostrophised in an amplificatory catalogue culminat

ing in “sons o f light, and partakers in the heavenly kingdom”:30

Милость бож ию и человеколюбие господа нашего Исуса Христа,

благодать ж е святаго духа, дарованую обильно человЪчьскому роду,

сказаю вам,

братие, добрии христолюбивии послушъници, чада цер-

ковъная, сынове свтыпа и причастъници царствия небеснаго.

Н ъ не от

своего сердца сия изнонпо словеса— в души бо грЪшьнЪ ни дбло добро,

ни слово пользьно ражаеться, — нъ творим повЪсть, въземлюще от

святаго ЕваньгЬлия, почтенаго нам ныня от Иоана Фелога,

самовидъця

христовых чюЪес. (V I336, 1-8)

I tell o f God’s mercy, and o f the lovingkindness o f our Lord Jesus Christ, and

o f the grace o f the Holy Spirit abundantly bestowed on humankind,

О my

brethren, О ye good and Christ-loving servants, offspring of the Church, sons

of light, and partakers in the heavenly kingdom.

Yet

I

do not bring forth these

words out o f my own heart: for neither good deeds nor profitable words are

bom in the heart o f a sinner. No:

I

take my story from the holy Gospel o f John

29 A recent attempt to describe this and similar features of the epideictic has successfully

drawn on ritual studies and anthropology, see Michael F. Carter, “The Ritual Functions of

Epideictic Rhetoric: The Case of Socrates’ Funeral Oration,” Rhetorica 9 (3), 1991, pp.

209-232.

c

30 This apostrophe of the congregation is remarkable and clearly motivated by the orator’s

rhetorical goal; in all other instances (twelve) of direct address in the sermons, Cyril con

fines himself to the conventional “brethren” (братие).

108 Ingunn Lunde

Scando-Slavica, Tomas 441998

D

o

w

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stellen

bo

sch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

the Theologian, whom we now revere, and who was an eyewitness to C hrist’s

wonders. (135)

The epithet “son o f light” is repeated subsequently with reference to the

blind man who was healed by Christ, an event which in a chain of tradition

al exegetical commentaries is interpreted by Cyril as representing the holy

baptism: the blind man is healed and gains sight, the man who is now able

to see (he is referred to as both проЗРЪ Вый and проСВЪТивый) is given

absolution through baptism and becomes a “son of light” (сын свЪта).

Through various rhetorical means — the structure o f the speeches o f the

protagonists, the style o f quotation, the repetition of the two key words

opening the sermon, милость and человтъколюбие — the mercy shown

to the blind man is generalised and shown to pertain to all people, who thus

become likewise “sons o f light” and “partakers in the heavenly kingdom.”

Finally, the main eyewitness in the narrative of this sermon, the blind man

who received sight, becomes a witness to Christ during their final encoun

ter (cf. John 9, 35-38), where in an extended speech structured as a creed

(with frequent repetitions o f вЪрую and ты еси) he testifies to Christ the

Messiah as prefigured in the Old Testament, incarnated as a human being

who will abolish the Law and bring Grace.

Our final example in this context may also be seen as a variation of the

eyewitness topos; this is how the invocation o f Zacharias, quoted above,

continues:

Приди ныня духомь, священый пророче Захарие, начаток слову дая нам

от своих прорицаний о възнесении на небеса господа бога и спаса

нашего Исуса Христа! Не бо притчею, нъ явгъ показал ecu нам, глаголя

[...] А о брани, бывъший на обыцаго врага диявола, от Исаия, сера-

фимъскаго видьца, разумеем. (V II340, 1-8)

Come now in spirit, О blessed prophet Zacharias, and provide us with a begin

ning for our homily, from your prophecies

9

f the ascension into heaven of our

Lord God and Savior Jesus Christ! For you showed this to us quite plainly,31

and not through a parable, saying [...] And regarding the battle which took

place against our common enemy the devil— o f this we can learn from Isaiah,

who himself witnessed the seraphim. (143)

31 The English “plainly” does not fully convey the sense of явЪ, which has also the mean

ing of “openly,” “clearly” (cf. явитися — “appear,” “manifest itself’). “Plainly” is, of

course, the chief meaning here, since it is opposed to “through parable.”

Cyril o f Turov and Epideietic Rhetoric

109

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

ow

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stellen

bo

sch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

This usage o f the reference topos may be regarded as a secondary function

o f the metadiscursive statement. Apart from its role as a reference to Cyril’s

source and its capacity to invoke the authority o f sacred texts, it enters, as

w e have seen, into the orator’s rhetorical system and becomes a means of

achieving a particular effect at the moment when the speech is delivered.

Similar, secondary functions of conventional, metadiscursive phrases

may be detected elsewhere in Cyril’s text. I shall consider an example from

the Sermon on the 318 Fathers, where Cyril employs the captatio benevo-

lentiae topos in an original way. The following passage concludes the in

troductory part o f the sermon:

Н ъ молю ваппо, братие, любовь, не зазрите ми грубости;

ничто же бо

от своего ума еде въписаю,

нъ проппо от бога дара слову на прославле

ние святыя троица; глаголеть бо: Отвьрзи уста своя и напълню я. ТВмь

приклоните ума вашего слухы, о ХристЬ бо начинаю слово, его ж е Арий

от бога отца отсЬщи мысляще. (VIII 3 4 4 ,1 9 -2 4 )

Yet I entreat your indulgence, О my brethren: do not despise my coarseness.

For here I write down nothing of my own invention.

Rather I beg from God the

gift o f the word for the glorification o f the Holy Trinity. For it is said: “Open

thy mouth wide, and I will fill it.” Therefore incline the ears o f your mind, for

I commence my homily on Christ, whom Arius sought to cleave from God the

Father. (150)

Here Cyril does not only indicate his inability to compose good sermons

and ask for assistance from God; he even stresses that the homily is not his

own invention, literally nothing is taken “from his own mind” (от своего

ума). The pronouncement is, very appropriately, confirmed by a Scriptural

quotation. The statement reminds us o f other, similar phrases in Cyril’s

texts: “Yet I do not bring forth these words out o f my own heart” (135);

“For I m yself do not create this narration” (144); Н ъ не от своего сердца

сия изношю словеса (V I 3 3 6 ,4-5); Мы бо слову иЬсм творци (VII 341,

1 6-17).32 In this case, however, the conventional phrase is re-functioned"

and becomes part o f the orator’s argumentation against Arius’ heresy.

There was no need for Cyril, bishop o f the twelfth-century provincial town

o f Turov, to get involved in complex theological pro et contra arguments

regarding the Arian controversy, the item at the top o f the agenda o f the

32 Such phrases have, not surprisingly, be taken as a proof of Cyril’s alleged lack of origi

nality; even the orator, or “compilator,” himself admits that he is not an original writer. In

my view, this is yet another example of reading into conventional phrases meanings or

intentions which are not there.

110 IngunnLunde

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

Cyril o f Turov and Epideictic Rhetoric

111

Council o f Nicaea (325). His account of the Council is rather a rhetorical

one; the outcome is, of course, clear (homologoumenon), and the orator’s

main object is the solemn praise o f the 318 fathers.

In Cyril’s text, once the fathers have assembled, Arius is invited to

present his doctrine first. He is immediately denounced by the fathers, who

apostrophise him in a catalogue o f 15 derogatory names. Then they formu

late their accusation:

Си от своего ума

, а не от святых книг извещал еси, и глаголеши

еже

твое сердце умысли

, а не еж е бог пророком и апостолом о своемь сыну

въписати повелЪ. (V III345, 33-35)

These things that you proclaim

are from your own mind,

not from holy Scrip

ture. You speak

that which your own heart has devised,

not that which God

ordered the prophets and the apostles to write down concerning His Son. (152)

What Arius is being accused o f is, in a sense, inventiveness and originality.

The wording is the same as in Cyril’s captatio benevolentiae phrase at the

beginning of the sermon, where he assures his audience that what he

preaches is not taken “from his own mind” (от своего ума). A highly con

ventional topos is, as it were, de-conventionalised and re-semantisised in

Cyril’s own rhetorical usage.33 Moreover, it forms part o f his overall rhe

torical strategy in this sermon, which follows two parallel strands — a

psogos o f Arius and an encomium of the fathers. In Cyril’s narrative, the

confrontation culminates in the speeches to each other o f the two conflict

ing camps at the Council. Whereas the arguments of the fathers are not tak

en “from their own minds,” but consist of a string o f Scriptural quotations,

Arius’ speech is represented as a distortion o f the divine authority in its

simplest form: through negation. In fact, his exposition of his doctrine takes

on the form o f a negated creed:

Что ся вам мнить о Христв, яко от

не

искони есть с богомь,

ни

едино-

сущьн богу отцю,

ни

равьн святому духу сущьствомь,

ниже

есть слово ’

бож ие в естьствЪ,

ни

тЬмь видимая створена бысть тварь,

ни

видим есть

33 The device is not found in Cyril’s two main sources for this sermon, a Slavonic account

of th Council principally based on George Hamartolus’ Cronicon breve, with additions

from elsewhere, and the prologue and a few other chapters from George’s chronicle, cf.

Francis J. Thomson, “Quotations of Patristic and Byzantine Works by Early Russian

Authors as an Indication of the Cultural Level of Kievan Russia,” Slavica Gandensia 10,

1983, p. 68, 80, n. 67.

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

D

o

w

n

lo

a

d

ed

by

[U

n

iv

er

si

ty

of

Stellen

bo

sch

]

at

09

:1

8

18

S

ep

te

m

b

er

2

0

1

3

отець сынови, ни въплътилъся есть бог в человЪче естьство, нъ вся

тварь небесная и земьная сьш божий речеться. (V III3 4 5 ,2 1 -2 6 )

You are deceived about Christ, for He was not with God from the beginning,

nor is He consubstantial with God the Father, nor is He equal in substance to

the Holy Spirit, nor is He God’s word in being, nor was all visible creation

made by Him, nor is the Father visible to the Son, nor was God made flesh in

human nature; but all creation in heaven and earth is simply called “God’s

son.” (152)

For Cyril’s audience these well-known phrases are, when negated, easily

identified as the “heresy” stemming from Arius’ own mind.

Finally, I shall consider a few instances which represent the closest

Cyril ever comes to commenting upon his own intentions and upon his own

view o f the sermon’s main objective. The following example is the begin

ning of the Sermon on the 318 Fathers, where Cyril, through an extended

comparison o f his task with that o f “the historians and the poets,” makes

several interesting remarks concerning his own efforts:

Яко ж е историци и вЪтия, рекше лЪтописьци и пЪснотворци, прикланя-

ють своя слухи в бывшая межю цесари рати и въпълчения, да украсят ь

словесы и възвеличатъ мужьствовавъшая крепко по своемь цесари и не

давъших в брани плещю врагом, и тЬх славяще похвалами втънчаютъ,

колми паче нам лЪпо есть и хвалу к хвалтъ приложити храбром и

великым воеводам божиям, крепко подвизавъшимъся по сынЬ божии,

своемь цесари, и господь нашемь ИсусЬ ХрисгВ. (V III3 4 4 ,1 -7 )

Since the historians and the poets —■

that is, the writers o f chronicles and the

makers o f songs — incline their ears to wars and battles that take place

between kings, that they may adorn with words and magnify those who fought

manfully for their kings and those who turned not their backs upon the foe on

the field o f battle, and that in praising such men they may crown them with

glory — how much more, then, does it behove us to heap praises upon the

great and. brave generals o f God who have striven manfully to follow their

King, God’s Son and our Lord Jesus Christ! (149-150)

Firstly, it is clear that Cyril sees his own speech, as w ell as that of “the his

torians and the poets” as an act, a rhetorical act, whose main goal is to

“crown with glory” the one whom he is eulogising in his sermon, that is, in

this case the fathers, but also the saints, holy men and, ultimately, Christ.

Secondly, the means through which this effect is achieved is an aesthetic

o n e— “to adorn with words.” Moreover, the main device is defined as am-

112 Ingunn Lunde

Scando-Slavica, Tomus 441998

Cyril o f Turov and Epideictic Rhetoric

113

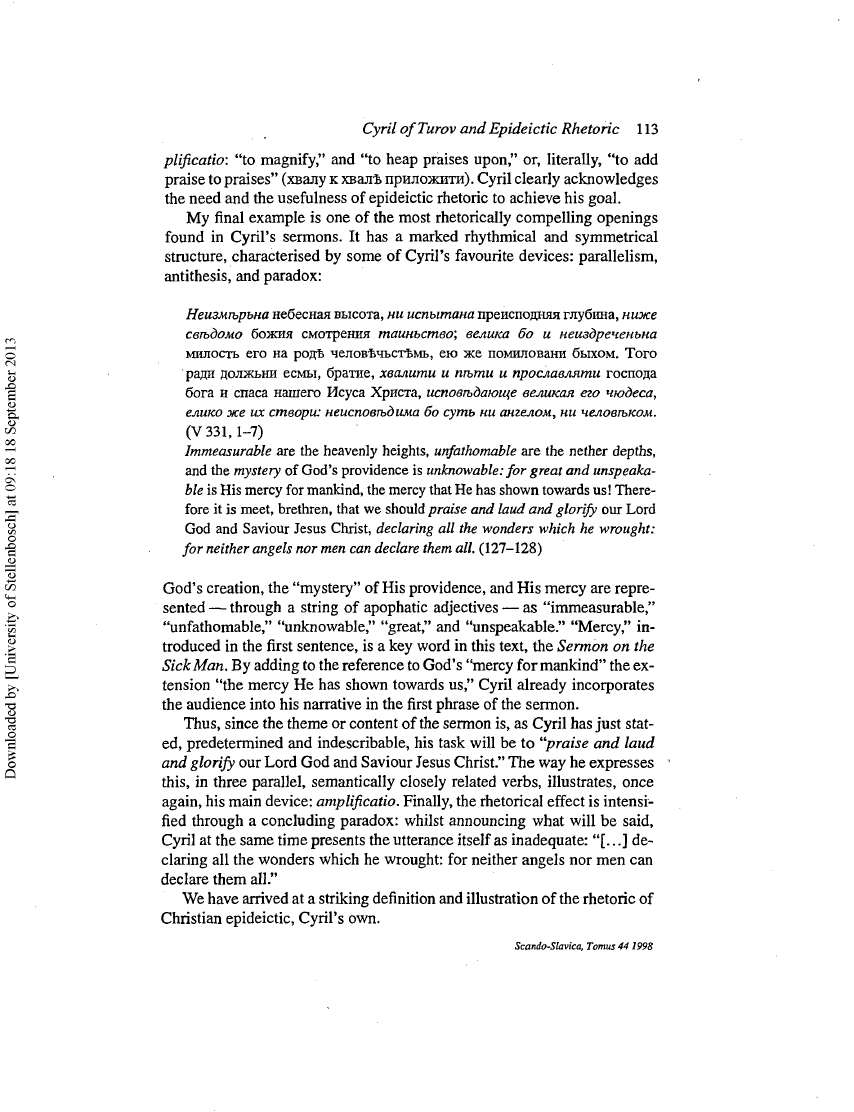

plificatio: “to magnify,” and “to heap praises upon,” or, literally, “to add

praise to praises” (хвалу к хвалі прилож ит). Cyril clearly acknowledges

the need and the usefulness o f epideictic rhetoric to achieve his goal.

My final example is one o f the most rhetorically compelling openings

found in Cyril’s sermons. It has a marked rhythmical and symmetrical

structure, characterised by some o f Cyril’s favourite devices: parallelism,

antithesis, and paradox:

Неизмтърьна

небесная высота,

ни испытана

преисподняя глубина,

ниже

свгъдомо

божия смотрения

таинъство; велика бо и неиздреченьна

милость его на родЬ челов'ЬчьстЬмь, ею ж е помиловали быхом. Того

ради должьни есмы, братие,

хвалити и тъти и прославляти

господа

бога и спаса нашего Исуса Христа,

исповтъдающе великая его чюдеса,

елико же их створи: неисповгъдима бо суть ни ангелом, ни человтъком.

(V 3 3 1 ,1 -7 )

Immeasurable

are the heavenly heights,

unfathomable

are the nether depths,

and the

mystery

o f God’s providence is

unknowable: for great and unspeaka

ble

is His mercy for mankind, the mercy that He has shown towards us! There

fore it is meet, brethren, that we should

praise and laud and glorify

our Lord

God and Saviour Jesus Christ,

declaring all the wonders which he wrought:

for neither angels nor men can declare them all.

(127-128)

God’s creation, the “mystery” o f His providence, and His mercy are repre

sented — through a string o f apophatic adjectives — as “immeasurable,”

“unfathomable,” “unknowable,” “great,” and “unspeakable.” “Mercy,” in

troduced in the first sentence, is a key word in this text, the Sermon on the

Sick Man. By adding to the reference to God’s “mercy for mankind” the ex

tension “the mercy He has shown towards us,” Cyril already incorporates

the audience into his narrative in the first phrase of the sermon.

Thus, since the theme or content o f the sermon is, as Cyril has just stat

ed, predetermined and indescribable, his task will be to “praise and laud

and glorify our Lord God and Saviour Jesus Christ.” The way he expresses

this, in three parallel, semantically closely related verbs, illustrates, once

again, his main device: amplificatio. Finally, the rhetorical effect is intensi

fied through a concluding paradox: whilst announcing what will be said,

Cyril at the same time presents the utterance itself as inadequate: “[...] de

claring all the wonders which he wrought: for neither angels nor men can

declare them all.”

We have arrived at a striking definition and illustration o f the rhetoric of

Christian epideictic, Cyril’s own.

Scando-Slavica, T om us441998

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Herrick The History and Theory of Rhetoric (27)

Contrastic Rhetoric and Converging Security Interests of the EU and China in Africa

A Way With Words I Writing Rhetoric And the Art of Persuasion Michael D C Drout

osogen zen and budo

ZEN tor Kartingowy

Osho Zen Tarot Transcendentalna gra zen (2)

Nothing Special Living Zen

Żeń-szeń opracowanie, 1. ROLNICTWO, Rośliny lecznicze

instructions for zen meditation 2GVX7YJXPQNLC74CRS3FJNXUAOIXYARA5IRHJXY

Osho (text) Zen, The Mystery and The Poetry of the?yon

Spr. 2 ZEN, POLITECHNIKA Rzeszowska

Osobowość zen, Wschód, buddyzm, cybersangha

Politicians and Rhetoric The Persuasive Power of Metaphor

Zen & the Art of Mayhem Optional Rules

Eugen Herrigel Zen w sztuce łucznictwa

Nukariya; Religion Of The Samurai Study Of Zen Philosophy And Discipline In China And Japan

Fundamentals of Zen Meditation

więcej podobnych podstron