Comment

www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 15 March 2014

249

a phase 1 study to establish the maximum tolerated

dose of the combination;

8

this phase 2/3 trial measured

progression-free survival as the primary endpoint.

Since only 267 patients were recruited—of whom

only 259 actually received the study drugs—the trial

was underpowered and thus, perhaps unsurprisingly,

there was no signifi cant diff erence in progression-

free survival between groups. Median progression-

free survival was 9·7 months (95% CI 8·1–14·5) in

the FOLFOX group, and 9·4 months (8·1–10·6) in the

fl uorouracil and cisplatin group (HR 0·93, 95% CI 0·70–

1·24; p=0·64). There were also no signifi cant diff erences

between groups in any of the secondary endpoints of

overall survival, proportion of endoscopic complete

responses, time to treatment failure, or occurrence of

grade 3 or 4 toxicities. The authors conclude that the

similar effi

cacy outcomes between the two treatment

regimens have implications for the potential use of

FOLFOX combination in cisplatin-intolerant patients.

Previously, cisplatin-intolerant patients have been

treated with radiotherapy alone, or with combinations

of radiotherapy and non-platinum-containing

regimens. However, most of these treatments have

worse survival outcomes when compared with standard

chemotherapy. Additionally, because of the high

inpatient and outpatient admission rates associated

with cisplatin as a result of patients requiring suitable

hydration, there is a potential cost benefi t to not

including cisplatin in a treatment regimen.

Thus, despite not improving progression-free

survival, this study has potentially shown an

improvement in the therapeutic ratio by increasing the

treatment options for cisplatin-intolerant patients,

and reducing the burden of treatment cost through

a less time-consuming and easier to administer

regimen—and thus, potentially, improving quality

of life for patients. I commend the authors for

completing this multicentre trial given its implications

for the future management strategies for oesophageal

cancer. It sets the scene for further randomised

trials designed to test similar endpoints with other

treatment regimens that contain platinum, such as a

regimen of carboplatin, paclitaxel, and radiotherapy,

which has been eff ective in the neoadjuvant

treatment of operable oesophageal carcinoma, and

has low toxicty.

9

Finally, I urge the authors of this trial

to publish their quality-of-life data. A study of this type

would be more complete with this additional data,

which could enhance the argument for replacement of

cisplatin with oxaliplatin.

Bryan Burmeister

Department of Radiation Oncology, Princess Alexandra Hospital,

Brisbane, QLD 4102, Australia

bryan_burmeister@health.qld.gov.au

I declare that I have no competing interests.

1

Al-Sarraf M, Martz K, Herkovic A, et al. Progress report of combined

chemoradiotherapy versus radiotherapy alone in patients with esophageal

cancer: an intergroup study. J Clin Oncol 1997; 1: 277–84.

2

Wong R, Malthaner R. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (without

surgery) compared with radiotherapy alone in localized carcinoma of the

esophagus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 1: CD002092.

3

Kohler RE, Sheets NC, Wheeler SB, et al. Two-year and lifetime

cost-eff ectiveness of intensity modulated radiation therapy versus

3-dimensional conformal radiation therapy for head and neck cancer.

Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013; 87: 683–89.

4

Crosby T, Hurt CN, Falk S, et al. Chemoradiotherapy with or without

cetuximab in patients with oesophageal cancer (SCOPE1): a multicentre,

phase 2/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 627–37.

5

Conroy T, Galais M-P, Raoul J-L, et al. Defi nitive chemoradiotherapy with

FOLFOX versus fl uorouracil and cisplatin in patients with oesophageal

cancer (PRODIGE5/ACCORD17): fi nal results of a randomised, phase 2/3

trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; published online Feb 18. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70028-2.

6

Mauer AM, Kraut EH, Krauss SA, et al. Phase II trial of oxaliplatin, leucovorin

and fl uorouracil in patients with advanced carcinoma of the esophagus.

Ann Oncol 2005; 16: 1320–25.

7

Chiarion-Sileni V, Innocente R, Cavina R, et al. Multi-center phase II trial of

chemo-radiotherapy with 5-fl uorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin in

locally advanced esophageal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2009;

63: 1111–19.

8

Conroy T, Viret F, Francois E, et al. Phase I trial of oxaliplatin with

fl uorouracil, folinic acid and concurrent radiotherapy for oesophageal

cancer. Br J Cancer 2008; 99: 1395–401.

9

van Hagen P, Hulschof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative

chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;

366: 2074–84.

Published

Online

February 13, 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S1470-2045(14)70073-7

See

Articles

page 315

Filling a gap in cervical cancer screening programmes

Cervical screening remains important, despite the long-

term promise of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination.

HPV testing is more sensitive than cytology for detection

of cervical pre-cancer and cancer, providing increased

reassurance and allowing extended screening intervals.

1

Nonetheless, the pace and manner of implementation

of primary HPV testing has varied substantially. In the

USA, HPV testing is recommended in conjunction with

cytology, whereas in the Netherlands, it is recommended

as one primary test.

2,3

In many places, it is not used at all.

Comment

250

www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 15 March 2014

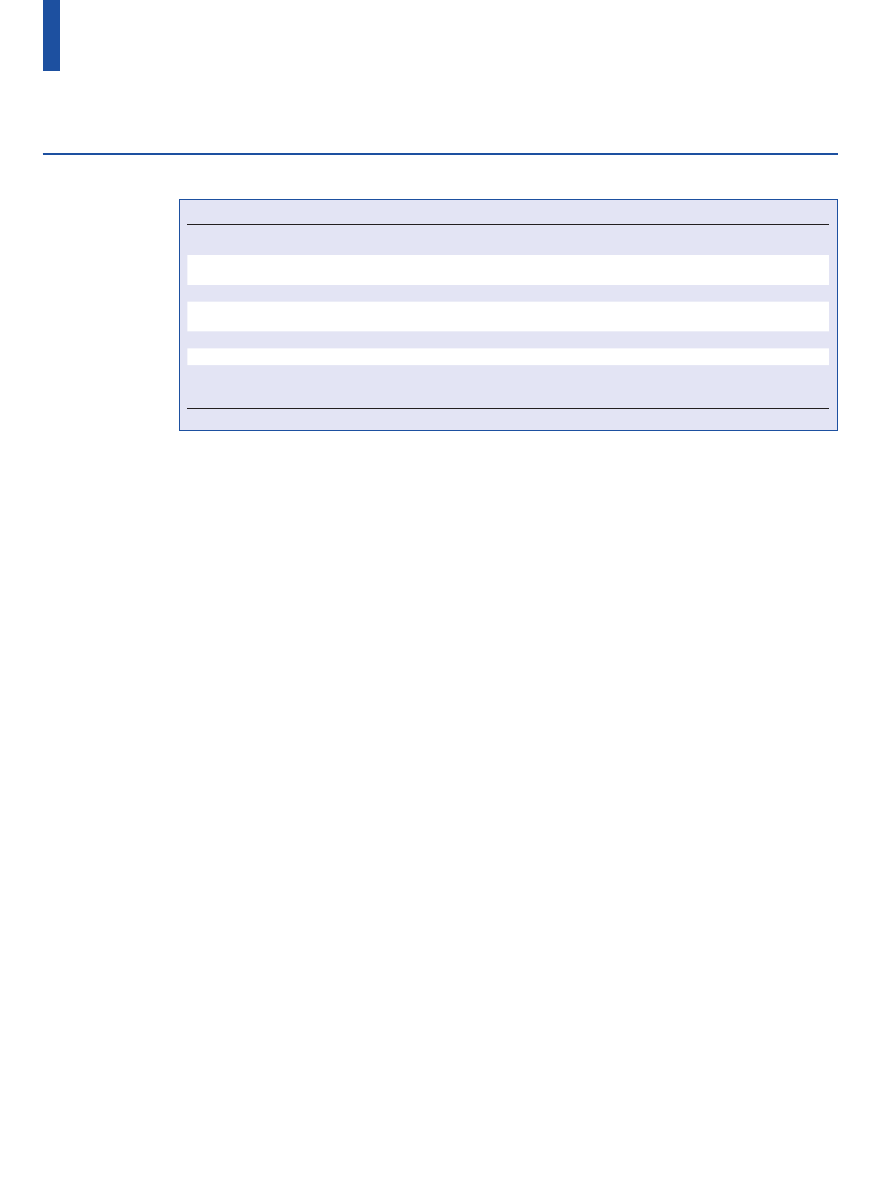

The successful introduction of HPV testing into

cervical cancer screening needs more than a sensitive

primary screening test (table). New programmes need

to be built around HPV testing. The major goal of

cervical screening programmes is to fi nd pre-cancers

that can be treated to prevent invasive cancers. A

diagnosis of pre-cancer needs colposcopic assessment

with cervical biopsies. Most HPV infections are transient;

a HPV-positive woman has a low risk of progressing

to pre-cancer and cancer. Thus, if HPV testing is used,

secondary (triage) tests are needed to decide who in

the HPV-positives needs to be referred to colposcopy. A

common suggestion is to move cytology into the role of

triage. New molecular assays such as p16/Ki-67 cytology

have higher sensitivity at comparable specifi city to

cytology.

4

Additional molecular markers such as host

methylation and HPV methylation are also being

investigated.

5–7

Irrespective of which screening and triage tests

are chosen, the crucial problem of non-participation

remains. A substantial proportion of cervical cancers in

developed countries arise in women who participate in

screening irregularly, or not at all.

8

Findings of previous

trials from the Netherlands have shown that the off er

of self-sampling for HPV testing to non-responders,

instead of an offi

ce visit, can increase participation.

9

As

with all HPV testing, women found to be HPV positive

by self-sampling need a triage test to decide who needs

colposcopy. However, self-collected samples are not

suitable for cell-based assays, such as cytology or p16/

Ki-67, so an additional collection is needed.

In The Lancet Oncology, Verhoef and colleagues

6

report the results of a randomised trial addressing

this gap in their screening programme. Investigators

enrolled initially non-participating women, found to be

HPV positive upon self-sampling, who were followed

up with two diff erent triage strategies: cytology from

physician-collected samples or methylation testing

of two genes, MAL and miR-124-2, from the self-

collected sample. The researchers found that the

clinical performance of methylation testing from the

self-collected specimen was equivalent to physician-

collected cytology. Because the assay was run from the

same specimen collected at baseline in HPV-positive

women, an additional offi

ce visit for most women

was avoided.

The Dutch team should be commended as pioneers

in the creation of an integrated HPV-based cervical

cancer screening programme. The approach described

by Verhoef and colleagues further improves the safety

net of their programme. As one possible caveat, the

participants in the trial generally reported being

screened before, and had a very high compliance

after they were included in the study, suggesting that

they were so-called soft refusers. The self-sampling

strategy might not apply as well to the fi rm refusers

who have never been screened before, putting them at

highest risk.

How do these results apply to cervical cancer

screening in other places? Findings of a recent meta-

analysis

10

showed that self-sampling has slightly

lower sensitivity compared with physician-collected

samples;in most resource-rich settings, self-sampling

is not approved as a fi rst-line alternative. The off er

of self-sampling for non-responders is especially

attractive for organised screening settings, but is

diffi

cult to implement in countries with opportunistic

screening like in the USA. Moreover, the methylation

Cytology

HPV

Co-testing (cytology and HPV)

Technology

Pap smear or liquid based cytology;

manual or computer-assisted assessment

Clinician collected or self-collected

Co-collection or separate collection

Relative repeat interval

for negative screen

Shortest (lowest negative predictive

value)

Longer (greater negative predictive

value)

Longest (greatest negative predictive value)

Triage test needed

For equivocal cytology results

For all positive results

For all HPV-positive, cytology-negative results

Triage test options

HPV or repeat cytology or p16/Ki-67

Cytology or HPV genotyping or

p16/Ki-67 or methylation

Repeat co-test or HPV genotyping or

p16/Ki-67 or methylation

Triage test sampling

Refl ex triage or separate collection

Refl ex triage or separate collection

Refl ex triage or separate collection

Diagnostic test

Colposcopy and biopsy

Colposcopy and biopsy

Colposcopy and biopsy

The three major primary screening options are cytology, HPV testing, or a combination of the two (co-testing). Not considered here is visual inspection, a screening method

under consideration for low-resource regions.

Table: Options for cervical cancer screening programmes

Comment

www.thelancet.com/oncology Vol 15 March 2014

251

assay used in the present study has not been approved

for clinical use, is not available as a kit, and has not

been assessed outside of the laboratory included in the

Dutch screening trials.

Our understanding of HPV and the natural history of

cervical cancer has brought great methods for cervical

cancer prevention, including vaccines for primary

prevention, HPV testing for screening, and various

molecular assays, including methylation markers, for

detection of cervical pre-cancers. Presented with many

HPV-related preventive options, high-resource countries

are considering various combinations; no one winning

strategy has emerged. However, low-resource countries

cannot aff ord the complex programmes established or

under development in industrialised countries. A triage

test that can be done out of self-sampling material like

the methylation assay described here could extend the

options for cervical cancer screening in low-resource

settings, where cytology programmes rarely exist

and colposcopy capacity is very restricted. However,

development of a robust, cheap methylation assay is

paramount to achieve this goal.

*Nicolas Wentzensen, Mark Schiff man

Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer

Institute, National Institutes of Health, Rockville,

MD 20892-9774, USA (NW, MS)

wentzenn@mail.nih.gov

MS has received HPV testing at no cost for NCI studies from Roche and Becton

Dickinson. NW and MS were supported by the Intramural Research Program of

the NIH, National Cancer Institute. The views expressed do not represent the

views of the US National Cancer Institute, the National Institutes of Health, the

Department of Health and Human Services, or the US Government. We declare

that we have no competing interests.

1

Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women

undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical

cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol

2011; 12: 663–72.

2

Health Council of the Netherlands. Population screening for cervical cancer.

2011. http://www.gezondheidsraad.nl/en/publications/prevention/

population-screening-cervical-cancer (accessed Feb 7, 2014).

3

Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society,

American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American

Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and

early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2012; 62: 147–72.

4

Wentzensen N. Triage of HPV-positive women in cervical cancer screening.

Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 107–09.

5

Mirabello L, Schiff man M, Ghosh A, et al. Elevated methylation of HPV16

DNA is associated with the development of high grade cervical

intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Cancer 2013; 132: 1412–22.

6

Verhoef VMJ, Bosgraaf RP, van Kemenade FJ, et al. Triage by

methylation-marker testing versus cytology in women who test

HPV-positive on self-collected cervicovaginal specimens (PROHTECT-3):

a randomised controlled non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; published

online Feb 13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70019-1.

7

Wentzensen N, Sun C, Ghosh A, et al. Methylation of HPV18, HPV31, and

HPV45 genomes and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3.

J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104: 1738–49.

8

Spence AR, Goggin P, Franco EL. Process of care failures in invasive cervical

cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev Med 2007; 45: 93–106.

9

Gok M, Heideman DA, van Kemenade FJ, et al. HPV testing on self collected

cervicovaginal lavage specimens as screening method for women who do

not attend cervical screening: cohort study. BMJ 2010; 340: 1040.

10 Arbyn M, Verdoodt F, Snijders PJ, et al. Accuracy of human papillomavirus

testing on self-collected versus clinician-collected samples: a meta-analysis.

Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 172–83.

Melanoma as a model for precision medicine in oncology

Published

Online

February 7, 2014

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S1470-2045(14)70059-2

See

Articles

page 323

Steve

Gschmeissner/Science Photo Library

Advances in the understanding of the molecular profi le

of tumour cells and progress in systems biology and

bioinformatics have led to the promise of precision

medicine for treatment of human cancer. Melanoma

has provided an opportunity for insights into both the

potential benefi t and limitations of precision medicine

for cancer.

In 2002, half of all human melanoma cells were

shown to harbour mutations in the BRAF gene,

1

the

product of which has an important role in cell division,

diff erentiation, and secretion through the MAPK or

RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK pathways. Mutations in BRAF

result in constitutive MAPK signalling and have been

associated with a number of tumour types. The ability

to detect mutations in BRAF from tumour biopsy

specimens and the availability of highly specifi c BRAF

inhibitors have begun to change the notion of the

clinical management of patients with melanoma.

In 2011, the BRIM-3 phase 3 trial,

2

comparing the

oral BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib with dacarbazine in

675 patients with BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma,

was reported. Vemurafenib was associated with a

signifi cant reduction in the risk of death (hazard ratio

[HR] 0·37, 95% CI 0·26–0·55; p<0·001).

2

Common

treatment-related adverse events included arthralgia,

rash, fatigue, keratocanthoma, and squamous-cell

carcinomas, with 38% of patients requiring dose

modifi cation. The results of this trial led to approval of

vemurafenib by the US Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) for patients with metastatic melanoma whose

Document Outline

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

European transnational ecological deprivation index and index and participation in beast cancer scre

Trend in cervical cancer screening in Spain

Increasing participation in cervical cancer screenin Telephone contact

Lower utilization of cervical cancer screening by nurses in Taiwan

New technologies for cervical cancer screening

Menagement Dile in cervical cancer

Alternative approaches to cervical cancer screening — kopia

New technologies for cervical cancer screening

Cost effectiveness of cervical cancer screening

Knowledge of cervical cancer and screening practices of nurses at a regional hospital in tanzania

Morbidity and mortality due to cervical cancer in Poland

The present ways in prevention of cervical cancer

Cytological screening for cervical cancer prevention — kopia

Perceived risk and adherence to breast cancer screening guidelines

Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer Knowledge health beliefs and preventive practicies

In vitro cytotoxicity screening of wild plant extracts

Fantasy and Reality in Nazi Work Creation Programs, 1933 1936

więcej podobnych podstron