Networks and leadership development: Building linkages for

capacity acquisition and capital accrual

Kathryn M. Bartol

a,

⁎

, Xiaomeng Zhang

b,1

a

Robert H. Smith School of Business, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742-1815, United States

b

American University, Kogod School of Business, Washington, DC 20016-8044, United States

Abstract

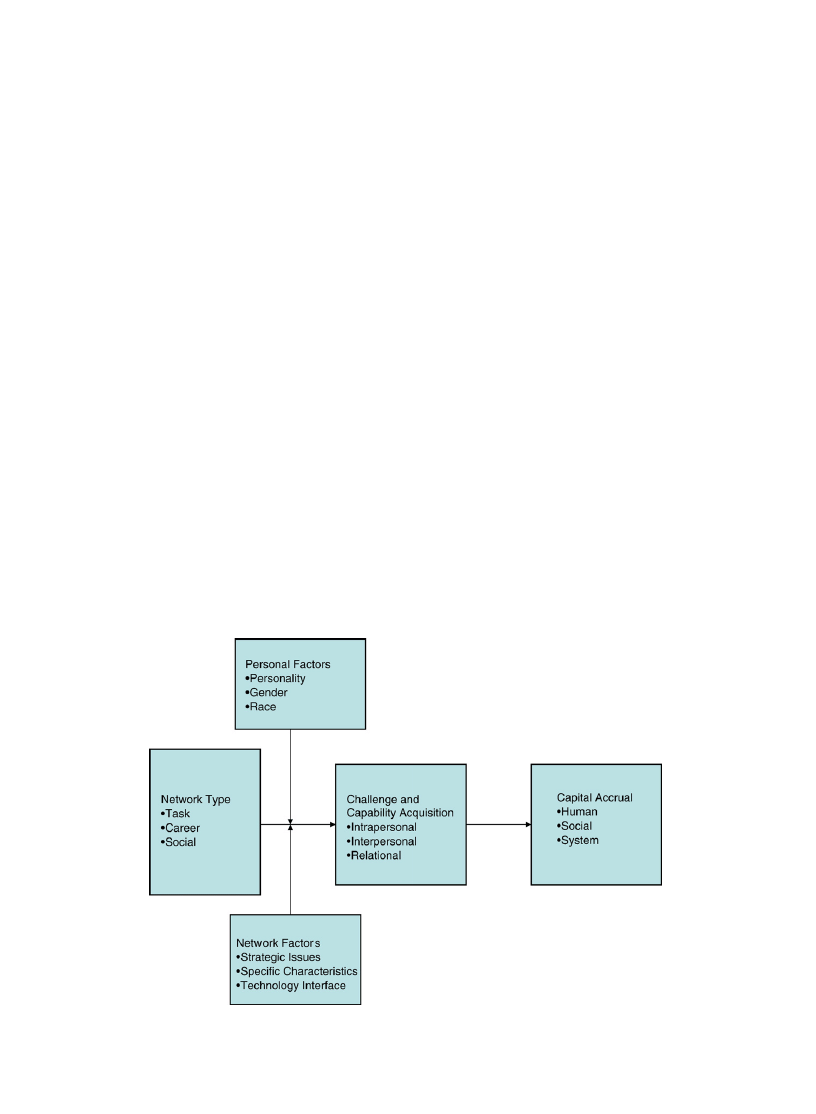

Social networks can aid the leadership development process through facilitating access to important developmental assignments

and the acquisition of capabilities to handle associated challenges. Although much of the traditional focus of leadership

development has been on building intrapersonal capabilities, functioning effectively as a leader necessitates the development of

interpersonal capabilities associated with dyadic ties and relational capabilities associated with patterns of ties within networks.

Such capabilities allow aspiring managers to accrue not only human capital, but social and system capital as well. Aspiring

managers can tap task, career, and friendship/support networks to aid developmental and career success. Structure factors,

including strategic choices, network characteristics, and the technological interface moderate the ability of managers to convert

potential network contacts into significant leadership development and capital accrual. Personal factors also influence leadership

development prospects. Overall, there are many ways in which network concepts associated with dyadic and relational levels of

analysis can facilitate addressing the challenges that are key to leadership development.

© 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Social networks; Leadership development; Managerial careers; Leader ties

1. Introduction

Although the need for leaders to engage in networking has been long recognized (

relatively little attention has focused on the potential of networking as a means of leadership development. Leadership

development refers to the expansion of an individual's capacity to engage in effective leadership roles and processes

(

Van Velsor, McCauley, & Moxley, 1998

). Leadership roles may involve positions with formal authority or informal

roles without authority. Related leadership processes address the strategies and steps associated with encouraging

individuals to work effectively together.

When considering leadership development, it is important to differentiate between leader development and lea-

dership development (

Day, 2000; Day & O'Conner, 2003

). The former focuses on building intrapersonal competencies,

whereas the latter requires a consideration of interpersonal and relational development. Leadership is essentially an

influencing process (

), through which leaders interact with others (e.g., followers, peers) to affect individual,

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

⁎ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 301 405 2249; fax: +1 301 314 8787.

E-mail addresses:

(K.M. Bartol),

(X. Zhang).

1

Tel.: +1 301 789 1385; fax: +1 301 314 8787.

1053-4822/$ - see front matter © 2007 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:

www.elsevier.com/locate/humres

team, and organizational performance. For most managers, career success ultimately depends on what they are able to

achieve in connection with others. Therefore, in contrast to the traditionally heavy focus of leadership development on

the capacities of the individual,

have argued recently that leadership can best be viewed as a

social process that involves those connected via social systems. One means of gaining insight into leadership

development as a social process is through the lens of networks. Thus, a social networks perspective provides a useful

framework for addressing the importance of social relationships on leadership development (

).

For the purposes of this paper, we define a network as a set of actors and the set of ties representing some

relationship, or lack thereof, between the actors (

).

have noted that the

emerging network paradigm highlights the advantages of considering individuals as embedded in a web of

relationships whose meaning is dynamically translated by the interacting parties. In this paper, we argue that networks

can help leaders develop leadership capacities both through leveraging existing network connections and working to

build new ones. We also consider important potential moderators of network and capability expansion processes. An

overall conceptual framework is shown in

.

2. Networks types

argues that networks are important to being able to accomplish work, gain upward mobility, and

develop personally and professionally. She posits that three types of networks are especially important to individuals in

managerial positions. Each of these types is particularly relevant to leadership development processes:

Task networks can help leaders accomplish work, including that which involves new challenges. Task networks

facilitate the exchange of resources aimed at accomplishing tasks. Such resources may include information, expertise,

materials, and task-related political access.

Career networks involve relationships with actors who can facilitate career progress by providing career advice,

offering mentoring and sponsorship, aiding in the securing of key developmental assignments, facilitating career-

enhancing visibility, and engaging in advocacy for promotions.

Friendship/social support networks at work address relationships that are based more on closeness and trust than on

task-related needs. These usually emerge from common backgrounds and/or interests and tend to be more informal

Fig. 1. Networks and leadership development conceptual framework.

389

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

linkages based on emergent friendship than patterned along formal structural lines. Such networks, however, often

facilitate work accomplishments and can be helpful to leaders.

As shown in

, each of the three types of networks can be considered in terms of one-on-one interpersonal

sources of development aid (dyadic ties). They can also be viewed more broadly from a relational perspective,

considering the web of multiple relationships in which an individual is embedded as a set of potential developmental

resources. For example, with task-related concerns, individual advisors may be helpful in facilitating task

accomplishment, but task advice conceived as a network phenomenon points to building broader knowledge of

who can aid the process and, equally important, potential access to the who (

). In recognition of the

network potential for facilitating task accomplishment, a number of organizations have set up communities of practice,

which essentially are networks of potential advisors whose expertise can be shared in a more relational way (

). With career-related development, considerable emphasis has been placed on mentor

–protégée relationships

(

Kram, 1985; Kram & Isabella, 1985

). However, more recent research findings suggest that individuals might more

productively think in terms of multiple, less intense relationships, which can be conceptualized as a network of

sponsors (

Higgins & Kram, 2001; Seibert, Kraimer, & Liden, 2001

). Finally, while social support can be considered in

terms of one-on-one relationships, it may be useful to think of social linkages as encompassing a system or network of

support that may potentially be helpful to leadership development processes. Leaders must understand their role within

social networks in order to strengthen existing relationships and establish new connections between individuals,

groups, and other entities (

). However, little research has focused on how social network

patterns or characteristics influence the leadership development process.

In considering relationships with others,

argue that such linkages in the development

process can fulfill three major developmental functions through providing assessment, facilitating access to or the

handling of challenging developmental assignments, and offering support. Within these three broad functions,

McCauley and Douglas further delineate a number of specific roles. For assessment, the roles are: feedback provider,

sounding board, point of comparison, and feedback interpreter. For challenge, the roles are: dialogue partner,

assignment broker, accountant (monitoring goal progress), and role model. For support, the roles are: counselor,

cheerleader, reinforcer, and cohort (others facing similar challenges). In

, we outline the types of aid that match

well to the three network types, recognizing that there is considerable overlap in the roles that each network type can

play in the developmental process. Thinking of leadership development in terms of multiple linkages and types of aid

can be helpful in pointing to the types of links that upwardly mobile leaders need to cultivate. It also offers the potential

for organizations to facilitate the development of at least task and advice networks. Of course, friendship networks are

more difficult for organizations to directly influence in behalf of aspiring leaders. However, organizations can be

catalysts for the formation of such networks through structural changes, work flows, physical location, and work

assignments (

Brass et al., 2004; Borgatti & Cross, 2003; Cross & Pruzak, 2002

).

3. Major development challenges and development opportunities

McCauley, Ruderman, Ohlott, and Morrow (1994)

have posited that there are five broad sources of challenge in

developmental jobs: job transitions, creating change, high levels of responsibility, nonauthority relationships, and

obstacles. One might think of these as issues that a leader needs to learn to address effectively, yet each new

developmental assignment by definition brings added challenges. In this next section, we discuss the usefulness of

Table 1

Types of network and aid with sources of development aid

Type of network

a

Sources of development aid

Type of aid

b

Interpersonal

Relational

Task

Individual advisors

Advice networks;

communities of practice

Task adviser, task sounding board,

task feedback provider

Career

Mentors

Mentors/sponsors

Career sounding board, career feedback provider,

cheerleader

Friends/support

Dyadic support

System of support

Supporter, cheerleader, reinforcer

a

Based on

.

b

Based on

390

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

network concepts to address challenges inherent in leadership development.

summarizes our approach. We do

not posit that the materials in

are comprehensive in covering all development opportunities related to leaders

and leadership; rather they are illustrative of developmental opportunities available across the intrapersonal,

interpersonal, and relational domains for each of the potential development challenge sources. In the discussion below,

we will place the most emphasis on issues of networks and interpersonal and relational development. Networks involve

consideration of dyadic ties and also patterns of such relationships.

3.1. Job transitions

Job transitions that are developmental typically involve taking on new duties that are much different, broader in

scope, and/or much larger than previously handled. There is also usually an element of proving oneself to a variety of

constituencies. While intrapersonal elements such as technical task mastery and role clarity are necessary, they are

unlikely to be sufficient to ensure success. Instead, leaders making job transitions, at a minimum, will need to forge

positive interpersonal relationships, or ties, with at least some key subordinates via leader

–member exchange

relationships (LMX;

Graen & Scandura, 1987; Uhl-Bien, Graen, & Scandura, 2000

). Often building rapport with a new

boss will also be part of the transition challenge. Thinking more broadly in network terms, however, job transitions are

likely to proceed more smoothly if the new leader can tap into a network of individuals with relevant knowledge about

the new context and/or with experience with similar transitions. It is possible that, if the transition leader does not

already have existing ties with some key individuals in the new context, such resources may be tapped indirectly

through existing ties to others who have ties within the new context. The probability of being able to leverage current

network ties in this way is more likely when upwardly mobile leaders build a diversity of relationships. Moreover,

transition leaders are more likely to be successful when they not only proceed to build relevant ties within their unit, but

also across units with which the work interfaces (

).

3.2. Creating change

Creating change involves being responsible for initiating something new, which may range from dealing with

inherited problems to creating and developing a significant innovation. The more uncertain and complex the change,

Table 2

Major development challenges and development needs/opportunities

Major development challenges

a

Illustrative major development needs/opportunities

Challenges

Nature of challenge

Intrapersonal (Self)

Interpersonal (Dyadic)

Relational (Multiple)

Job transition

Unfamiliar responsibilities,

proving oneself

Task mastery; role

clarity

Establishing leader

–member

exchange (LMX) and other

dyadic

relationships

Building network of

relevant ties; tapping

existing ties for advice/

help

Creating

change

New directions; fixing

inherited problems

Change process

knowledge

Influence and persuasion

skills

Coalition building

High levels

of responsibility

High stakes; business

diversity; job overload;

external pressure

Cross-functional business knowledge;

problem solving; coping with stress

Delegating; handling

interpersonal conflict;

impression management

Adding to and leveraging

network of ties; building

power

Nonauthority

relationships

Influencing without

authority

Reciprocity/exchange concepts;

analyzing dependencies and structure

Building one-on-one

relationships with peers,

people in higher

positions, external

parties, key others;

mutual influence

Building network of key

internal and external

contacts

Obstacles

Adverse business

conditions; lack of top

management support; lack

of personal support;

difficult boss

Self-awareness

Social awareness

System awareness

a

Based on

391

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

the higher the potential for development (

), but also the higher the potential for missteps. From an

intrapersonal point of view, a leader would be aided by acquiring knowledge of change processes, such as

eight steps for creating change, and learning more about influence processes (

). However, the

possession of explicit knowledge regarding change processes and related influence processes does not guarantee that a

leader will be successful in actually implementing change, a notoriously difficult task (

). Instead,

there is much to gain by development processes that target the actual acquisition of interpersonal influenced skills, such

as communication and persuasion. Change processes of significance, however, are likely to require more than thinking

in terms of one-to-one relationships. While such dyadic ties may be useful in terms of building pieces of a coalition,

leaders also need to learn to conceptualize and act more broadly through thinking in terms of diffusion of change

messages indirectly through the ties of coalition members (

Brass & Krackhardt, 1999; Krackhardt & Kilduff, 2002

Change challenges often involve complex problems and constituencies. Managers may be able to alter the pattern of

networks to aid the change process through such means as structural changes that facilitate individuals acting as links

among others (

3.3. High levels of responsibility

The challenges associated with taking on higher levels of responsibility typically encompass higher stakes,

increased business diversity/complexity, and greater need to address external pressures, along with the possibility of the

job becoming overwhelming. From an intrapersonal point of view, knowledge about cross-functional aspects of the

business, strong problem solving skills, and the ability to cope with stress are often helpful. At the interpersonal level,

leaders taking on high levels of responsibility must consider delegating more to the individuals who work for them.

Such leaders are also likely to be required to handle more interpersonal conflict situations due to the wider span of

control (

). Moreover,

have argued for the importance of impression management

skills for effective leadership. They particularly delineate the processes involved in creating and maintaining identities

as charismatic leaders. At the relational levels, advice networks again can be helpful for obtaining counsel regarding

how to function effectively with significantly more responsibility. Such networks are unlikely to be in place unless the

leader has been building networks with an eye toward upward mobility. Such networks need to be reasonably diverse.

found that CEOs with firms registering relatively low performance tended to seek

counsel from executives from other firms who were friends or were similar to them, rather than from acquaintances and

individuals who were dissimilar to them. This tendency led to a lower probability of making necessary strategic

changes and contributed to a downward spiral in performance. Thus, leaders need to learn to develop multiple types of

networks, including social networks for support and task networks for advice. While overlap is possible, upwardly

mobile leaders need to differentiate between individuals who can provide support and those who might make better

task advisors. Mentors/sponsors in high places also can provide insight in attempting to take on higher levels of

responsibility (

3.4. Nonauthority relationships

Gaining the cooperation of individuals who are not in one's reporting chain constitutes a different type of challenge.

Such situations include working with peers, customers, and individuals in other organizations. Cross-function teams are

another context in which one must attempt to influence without direct authority. While understanding reciprocity and

exchange concepts, as well as being able to analyze areas of dependency on others can be helpful, ultimately leaders

need to be able to develop one-on-one relationships with peers, individuals at higher levels outside one's own chain of

command, key others at lower levels, and a variety of external parties.

note a variety of

organizational

“currencies” that can be used to help gain “influence without authority.” Others, such as

, have also addressed

“how to lead when you're not in charge.”

point to possibilities

for shared leadership in which mutual influence processes among team members allow for shifts in the agent and target

of influence depending on the characteristics of the specific task and the knowledge, skills and abilities of team

members. Such an approach offers possibilities for the development of leadership skills among a broader segment of the

organization (

Pearce & Conger, 2003; Pearce & Sims, 2000, 2002

). From a relational point of view, leaders potentially

have much to gain in building networks of individuals whose influence is needed to carry out necessary tasks and

individuals whose expertise, advice and support can be helpful. Research by

points to the value of inter-

392

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

unit connections and group effectiveness. Building networks involving nonauthority relationships is helpful for leaders

to further develop their use of reciprocity and exchange, which are crucial elements in successful network relationships.

3.5. Obstacles

Overcoming obstacles constitutes another major type of developmental challenge. Obstacles are associated with

contextual aspects that make achievement more difficult unless some way is found to remove or otherwise overcome

these impediments to progress. Common obstacles, such as dealing with a difficult boss, facing unsupportive peers, or

confronting adverse economic conditions, can undermine the self-efficacy and morale of developing leaders.

points out that success in overcoming obstacles not only provides experience in dealing with difficult situations,

but also helps leaders develop perseverance and confidence. Yet, she notes that leaders often do not perceive the

positive aspects of dealing with obstacles until they are thinking about the situations in retrospect. By seeking the

advice of mentors and supporters, leaders facing obstacles are likely to be better positioned to deal with the obstacles

both intellectually and emotionally. Moreover, being able to tap a broader network enhances possibilities for

uncovering more useful information to aid in removing, neutralizing, or surmounting obstacles.

4. Capital accrual

Leadership development can be conceptualized as involving three types of capital (

): human,

social, and system. Human capital refers to the knowledge, skills, and abilities that individuals possess that have value to

organizations. Within a leadership development context, the main focus of human capital is on the development of

intrapersonal capabilities. A strong focus on intrapersonal capabilities can help build leader capabilities, but to address

actual leadership capabilities, greater focus on influence processes with people is needed (

). In contrast, social

capital accrues from direct ties to various individuals based on reciprocity and social exchange. Through building positive

relationships and helping others, one accrues good will and some sense of exchange. For example, building positive

leadership relationships with subordinates in the form of leader

–member exchange has been shown to have positive

influences on job related attitudes and behaviors (

). System capital refers to the ability to draw on and

leverage a network of ties, accessing not only one's own direct ties, but, indirectly, the ties of others to tap the resources of a

broad network. Thus, networking is a major way to enhance both social and system capital in an organization because

much of the capital is embedded within networks of mutual acquaintance. Networks of relationships are critical to

conducting business affairs, providing actors with collectively owned capital (

Day, 2000; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998

).

Adding network concepts to more conventional ways of thinking about leadership development allows for the

identification of multiple forms of capital that would-be leaders can advantageously accrue. From an organizational

point of view, it is possible to think in terms of aiding aspiring leader's efforts to accrue social capital through such

measures as developing mentoring programs that are more networks of mentors than individual one-on-one

relationships, encouraging the formation of advice networks, and facilitating the development of cross-organizational

peer relationships through conferences and training programs that not only build human capital, but allow the

formation of systems capital.

5. Network structural factors

In exploring the implications of networks for leadership development, it is also useful to consider a number of

relevant network structural factors. The ability of aspiring leaders to translate the three types of networks

–task, career,

and social

–into capability acquisition is dependent on a number of such factors. Here we first discuss important

strategic considerations before addressing more specific network characteristics likely to influence leadership

development success. Finally, we consider the impact of technology on network building and maintenance for

leadership development purposes.

5.1. Strategic issues

As several researchers on networks have noted, leaders do not possess infinite amounts of time to expend in pursuit

of building and maintaining networks. Therefore, they must make strategic choices with respect to relationships (

393

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

). More time investment is required to build strong ties than weak ties; and there is the question of how many

ties to build.

research on job search suggested that there was strength in weak ties, owing to the

greater amounts of information inherent in more extensive, but weaker ties. In contrast, few stronger ties led to

redundancy of information. Building on this notion,

has argued that the crucial issue is positioning oneself

to fill structural holes. Structural holes are missing links between two individuals who have ties to the aspiring leader.

By acting as the link, the leader is able to gain advantage both by controlling information between the two individuals,

and also having access to information gleaned from the two individuals (and others they are differentially connected

to).

research showed that male managers who positioned themselves to fill structural holes were more

successful in terms of early promotions.

found that weak ties and structural holes led to greater

career success in terms of high salaries, more promotions, and greater career satisfaction. Work by

also pointed to career advantages of large, more diverse networks. A contrasting view from

argues that it is useful to build a dense network of close ties who themselves have other connections that can be

leveraged for mutual benefit. Borrowing from both views, a smaller set of strong ties may make sense for friendship/

support networks, while having broader weak tie networks may be particularly helpful in the task and advice realms.

5.2. Network characteristics

social network theory focuses on relationships between actors, who are embedded in a web of

networks. Network characteristics (e.g., centrality, strength, size, etc.) provide context, determine social structure, offer

opportunities, and constrain actor behaviors, thus influencing leader roles and affecting leader development in

networks. Among the variety of network characteristics, we identify three categories of network characteristics that are

particularly relevant to the leadership development process: individual actor characteristics within a network, dyadic tie

characteristics, and entire network characteristics (

5.2.1. Individual actor relationships within networks

Since a network is defined as relationships among a set of actors, characteristics of individual actor relationships

within networks (e.g., degree, closeness, and status) are fundamental to exploiting networks to aid leadership

development processes. Here we consider three characteristics that research has shown are important to leadership:

centrality (degree), closeness, and status of contacts.

Network centrality refers to the extent to which an actor is central to a network. It is measured a number of different

ways, with one of the most important being degree (the number of direct links with other actors within a network).

Centrality implies greater access to and control over valued resources (

). Studies suggest that network centrality

is positively related to increased power and is predictive of informal leadership (

) and promotions

). Centrality aids incumbent leaders because being in a central position makes it easier for leaders to influence

others and achieve greater work unit stability. In addition, centrality in social networks positively predicts individual work

place performance (

Mehra, Kilduff, & Brass, 2001; Sparrowe, Liden, Wayne, & Karimer, 2001

Related to centrality, closeness is one of the measures often used as an indicator of centrality (

Closeness refers to the extent to which an actor can easily reach all the other actors in the network

—i.e., the extent

Table 3

Network categories and characteristics

Network

category

Network characteristics

Individual actor

♦ Centrality: the extent to which an actor is central to a network

♦ Closeness: the extent to which an actor is close to, or can easily reach all the other actors in the network

♦ Status: level of position (hierarchical position) of contacts; or the relative standing of an actor in a social system based on some

measure of prestige

Dyadic ties

♦ Strength: amount of time, emotional intensity, intimacy, and reciprocal services between actors

♦ Symmetry (reciprocity): extent to which relationship is bi-directional

Entire network

♦ Cohesiveness: actors' affinity for one another and their desire to remain part of the group

♦ Density: ratio of number of actual links to the number of possible links in the network [n(n−1)/2]

♦ Size: number of actors in the network

Source: Adapted from

394

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

to which the most direct paths to reach each of the other actors in the network are short or long (

).

The closer an actor is to others, the easier it is for the actor to access different channels of information and to establish

mutual trust and norms (

). Closeness makes the actor less dependent on others because there

are a number of channels through which a leader can reach others in the network (

). Thus, closeness can be a source of social capital, facilitating information exchange and knowledge transfer

among network members, while also reducing dependence.

Another important network characteristic is the hierarchical level or status of one's contacts. Several studies show

that having contacts at higher levels in the hierarchy is associated with greater career success. For example,

found that higher level contacts led to greater access to information and more career sponsorship, which

then translated into greater career success in terms of salary and promotions.

results showed that

hierarchical status (e.g., the hierarchical level of network members) is a predictor of organizational knowledge, task

mastery, and role clarity, all of which are significant indicators of learning.

suggest that the

level of position is the most important structural characteristics in relation to leadership emergence, stability, and

change because it is closely related to access to power (

) and social capital (

). High

status contacts can also create prestige for the actor. Research by

showed that the

perception of a friendship link to a prominent person in an organization was associated with an increase in an

individual's performance reputation.

Overall, network centrality, closeness, and contact status all help individual actors expand their capacities to

effectively engage in leadership roles and processes, thus facilitating leadership development. For leadership roles,

centrality and status predict leadership formation and change, either by strengthening the stability of existing leader

positions, or by facilitating leader emergence without formal authority. For leadership processes, closeness and status

assist network actors in building mutual trust and promote mutual learning.

5.2.2. Characteristics of dyadic network ties

Actors are major components of social networks, but it is dyadic ties that make the connections and represent the

relationships, or lack of relationships, between the actors. Thus, the characteristics of dyadic ties (e.g., tie strength,

symmetry) are an important consideration in attempting to exploit the advantages of networks for leadership

development purposes.

Tie strength refers to the amount of time, emotional intensity, intimacy, and reciprocal services between network

actors.

discusses the weakness of strong ties and indicates that when passed through weak ties

rather than strong ties, whatever is to be diffused can reach a larger number of people and traverse greater social

distance (i.e., path length). Thus, from an actor's point of view, weak ties provide more information because weak ties

enable an actor to connect to diverse groups, while strong ties limit the potential solutions to problems due to their

constraints on the breadth of information and input (

). Similarly,

found that

network tie strength was negatively related to the acquisition of organizational knowledge, thus forestalling personal

development. Therefore, weak ties generally offer greater opportunities for aspiring leaders in a network to expand

their capacities than do strong ties.

Symmetry, or reciprocity, refers to the extent to which the relationship is bi-directional. This means that one actor's

choice of another is reciprocated. For example, one actor reports to be the friend of another actor, and that other actor

makes a corresponding choice, which evidences the acknowledgement and mutual esteem between the two (

).

Brass, Butterfield, and Skaggs (1998)

suggest that unethical behaviors in organizations, such as illegal

brokerage transactions or embezzlement, are most likely to occur in an asymmetric relationship because asymmetric

ties indicate that the trust and emotional involvement of one actor is not reciprocated by another actor. This leaves the

trusting party at risk due to the potential for exploitation by the non-trusting and emotionally uninvolved relationship

actor in the pair. Developing leaders need to be able to build symmetrical ties with key individuals who are critical for

success with respect to a particular development challenge.

5.2.3. Characteristics of entire network

Individual actor network characteristics and dyadic tie characteristics influence actors' leadership development in an

organization as discussed above. However, those characteristics do not take place in isolation, but have meanings only

in the context of broader relational networks (e.g., teams, groups, or an entire organization). Cohesiveness, density, and

size are typical measures used to describe larger (beyond dyadic) network characteristics (

395

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

Cohesiveness refers to actors' affinities for one another and is a measure of the attraction of the members to the

group, the sense of group spirit, and the willingness of the group members to coordinate their efforts. Thus, group

cohesiveness provides insight into how a network functions because a group represents the context of the rational

network (

). High-cohesiveness in a group has been shown to lead to greater intra-group communication

(

), lower perceptions of inter-group conflict (

), and more

favorable interpersonal evaluations within groups (

). Thus, compared with members of a low-

cohesion group, those in a high-cohesion group often are more satisfied with the group, are more cooperative and

friendly with each other, and are likely to be more effective in achieving the aims members set for themselves.

However, high cohesiveness tends to encourage redundant ties and less access to outside information, creating

dilemmas for leaders.

Network size and density are interrelated network characteristics. As mentioned previously, network scholars have

suggested that, for network actors to accomplish tasks and achieve career-related success, a larger network with non-

redundant informational contacts is more effective than a small network in which the parties are highly interconnected

(

Singh, Hybels, and Hills (2000)

indicated that network size is significantly and

positively related to the number of opportunities recognized.

suggested that high density networks

(many connections among ties) are negatively related to the learning of general organizational knowledge, because of

the redundancy of information typically inherent in dense networks. Therefore, larger size networks (numerous

connections) with low density (the absence of many connections among ties) provide more diverse information access

possibilities, which facilitate leadership development.

All in all, network characteristics differentially facilitate or impede the development of interpersonal and relational

skills, while affecting information access, organizational learning, problem solving and opportunity identification. As

pointed out, individuals do not have unlimited time and, therefore, must make careful choices regarding

network ties to cultivate. He argues that seeking to bridge structural holes is an effective strategy. Thinking in terms of

the overall structure of one's networks is important for leaders. The structure may differ for task, advice, and friendship/

support networks. Even following a strategy of fewer ties, but ones that span structural holes, may lead to mundane

thinking unless these contacts also maintain diverse ties.

5.3. Information technology interface

Increasingly, information and communication technologies (ICTs) are being used to facilitate communication within

and across organizations. While such technologies allow for greater reach in terms of networking, they also offer

challenges as a networking interface. For example, ICTs limit the nonverbal cues that aid assessing attentiveness,

interest, and warmth-factors involved in building relational links (

Martins, Gilson, & Maynard, 2004; Gibson &

). Yet ICTs are increasingly used to facilitate the use of virtual teams, enable individuals engaging in

telework, and foster interorganizational connectivity (

). Leadership development in what has been

called the

“digital economy” must incorporate capabilities for interfacing and networking with new technology tools. In

fact,

suggest that technology is considered an important factor influencing network

structure. They found that some employees increased their power and network centrality following a change in

computer technology. More specifically, early adopters of the new technology increased their power and centrality to a

greater degree than later adopters because early adopters were able to reduce uncertainty for others. Thus, aspiring

leaders would do well to stay up on emerging technologies, and aim some of their efforts towards learning how best to

use ICTs to facilitate interpersonal and relational ties. Information technologies enable the maintenance of a broader set

of relationships, though the development of a strong friendship group aimed at support may be difficult to develop on-

line.

At the same time, the use of technology has a role in leadership development programs offered by universities,

communities, and professional organizations (

). On-line programs of various sorts are offered by a

multiplicity of vendors, and organizations themselves are harnessing technology to offer programs via intranets or the

Internet, particularly aimed at increasing intrapersonal capabilities of leaders. Advanced information technologies

include e-mail, message boards, groupware, as well as collaboration tools, techniques, and knowledge, that can

facilitate multiparty participation. Such advances offer new possibilities for leadership development interactions

(

). For example,

argue that technology can enable e-mentoring,

which allows mentoring to transcend the constraints of geographical location and time. Thus, information technology

396

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

provides a number of means that developing leaders might use to access not only intrapersonal development materials,

but also to facilitate network building and opportunities for on-line interactions through emerging group collaboration

software.

6. Personal characteristics

People are social beings who create significant ties with others like themselves to establish identity and friendship

). In organizational settings, different people use different ties for task accomplishment,

career achievement, and social support. For example, the presence of mentors and the availability of a broader network

of supporters are critical factors that may influence an individual's progress and career success (

). However, many researchers have suggested that these sources of support in an organization may not be equally

accessible to diverse groups of people (

Ibarra, 1993; Ragins & Cotton, 1991

). More specifically, the personal

characteristics of individuals, such as gender, race, age, personality, and educational background may have a significant

impact on access to and involvement in networks (

McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001

Research on the social networks in organizations has indicated the importance of categories such as gender and race

as bases for network formation and personal development (e.g.,

Hughes, 1946; Ibarra, 1993; Mehra et al., 1998

). Thus,

we especially focus on gender and race as potential contingencies that moderate the effects of networks on leader skill

acquisition and capital accrual in an organization.

6.1. Gender as a contingency

Although there has been increasing awareness of gender and upward mobility issues in academia and business

organizations, research still indicates that females have not obtained status, influence, and benefits comparable to their

male counterparts (

). In investigating the reasons, considerable research has examined gender discrepancies

in access to and use of networks (e.g.,

Brass, 1985; Ibarra, 1992; Rothstein & Davey, 1995

). Research indicates that

men and women have significantly different network characteristics (e.g., status, centrality, the amount of support

received), which contribute to differential benefits accruing from their networks (

A number of studies have identified a homophily effect with respect to networks, which refers to a tendency for

individuals to interact and develop ties with individuals that are similar to them on such characteristics as gender and

race. For example,

indicated that women tend to interact more with women and men tend to interact more

with men in their interpersonal networks.

found that women were not well-integrated into men's

networks, and vice versa. Since men's networks in organizations often include the organization's dominant coalition,

gender-segregated networks may be disadvantageous to women. Thus, the lack of equal access to informal interactions

and communications may be one reason that females are still underrepresented in high level positions in organizations

(

Bartol, 1978; Bartol, Martin, & Kromkowski, 2003; Brass, 1995

Associated with the homophily effect, women usually have ties to network members with lower status relative to men

because the positions women occupy limit their access to and ability to attract powerful employees as contacts

(

). With their low status, women tend to have low levels of network centrality, which significantly and

negatively impacts their prospects for leadership development and promotions (

), as well as informal

leadership and authority formation (

).

found that female faculty

realized the importance of social support more than male counterparts did, and, therefore, expended more effort than

men to extend their networks in order to obtain higher levels of support.

, however, notes women and new

leaders may have a difficult time breaking into important established networks and may need to seek mentors in order to

do so. Such a strategy, though, has the disadvantage of accessing network connections indirectly (through the mentor), at

least in the short run.

found that high potential women more so than high potential men tended to rely on

close ties and relationships outside of their work subunits, suggesting a potential alternative strategy for women.

Overall, although considerable progress has been made in the access of women to higher level managerial positions

), there is still evidence that females experience difficulty in building contacts and gaining access to the

networks of dominant coalitions in organizations and, therefore, face more challenges in accruing the benefits of

networking in business organizations. Low status, lack of informal networks, low levels of centrality and less support

received from upper levels, all restrain females' intrapersonal, interpersonal, and relational network formation, thereby

reducing the significant opportunities for major leadership development for women.

397

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

6.2. Race as a contingency

Lack of informal interactions and communication is also one of the major reasons that racial minorities are still

underrepresented in leadership positions, and especially in upper-management ranks (

). The homophily effect

with race is even stronger than with gender (

). Compared to majority group members, racial

minorities are more likely to make within-group identity and friendship network contacts (

). Although

these same-race homophilous ties may provide valuable sources of mutual support, the decreased network diversity greatly

restricts racial minorities' access to information networks and related resources in organizations (

). Yet, informational networks are significant indicators of familiarity with organizational knowledge, task mastery,

and role clarity, all of which are closely related to organizational learning and personal development (

).

In addition, research also indicates that minority members tend to have network contacts with lower status because

majority members usually occupy the organization's dominant coalition (

).

found that minority members of boards of directors were more influential as board members if they had direct

or indirect social network ties to majority directors through common memberships on other boards. Such ties enabled the

minority board members to create the perception of similarity with the majority, thus avoiding out-group biases.

Overall, several studies have suggested that networks of information and support in an organization are not equally

accessible to minority managers as compared with majority managers. Because of the relatively small number of

minority managers at high levels in organizations, minority managers tend to have fewer opportunities to form high

status ties and thus have limited access to their organization's dominant coalition. The resulting restricted information

channels, in turn, impede task development and career advancement of minorities.

6.3. Personality as a contingency

Emerging evidence suggests that personality may impact the structure of networks and individuals' positions in

them. For example,

found that high self-monitors were prone to occupy more central positions in

social networks than were their low self-monitoring counterparts. The high self-monitors tended to move into more

central positions as their tenure in their organizations increased, while this was not the case with low self-monitors.

Both high self-monitoring and central position had independent effects on performance. The high-self monitors were

more likely to occupy positions that spanned social divides, thereby allowing them access to a more diverse set of

resources. The authors noted that one challenge for high self-monitors might be how to avoid accepting too many

challenging responsibilities, which might be difficult to carry out while also maintaining a more expansive social

network. Ibarra suggests that individuals who are high self-monitors might be more flexible in making changes that

allow them to fit into different types of positions and social milieu. Thus, high self-monitors may have an edge in using

social networks for development purposes and in facilitating their upward mobility.

Klein, Lim, Saltz, and Mayer (2004)

also provide evidence indicating that personality impacts centrality in team

social networks. More specifically, emotional stability predicted centrality in all three types of networks under study:

high centrality in advice and friendship networks and low centrality in adversarial networks. Openness to experience

was negatively related to centrality in friendship networks and positively related to adversarial centrality, suggesting

that individuals engaged in leadership development need to gauge carefully how they approach attempting to bring

about change so as not to produce adverse reactions.

found that extraversion was related to

centrality in advice and support networks within teams.

7. Conclusions

Networks can aid the leadership development process through facilitating the handling of challenges and the acquisition

of capabilities particularly in the interpersonal and relational realm. Although much of the traditional focus of leadership

development has been aimed at the acquisition of intrapersonal capabilities, functioning effectively as a leader necessitates

the development of interpersonal and relational capabilities. Such capabilities allow aspiring managers to accrue not only

human capital, but social and system capital as well. Aspiring managers can tap task, career, and friendship/support

networks to aid in acquiring and effectively handling challenging assignments, thus facilitating the likelihood of enhanced

career success. Structure factors, including strategic choices, network characteristics, and the technological interface,

moderate the ability of managers to convert potential network contacts into significant leadership development and capital

398

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

accrual. Personal factors also influence leadership development prospects. Organizations can encourage aspiring leaders to

develop appropriate types of networks and can facilitate the integration of functions, such as feedback, coaching, and

mentoring (

), into existing networks. Training programs, conferences, and strategically developed meetings can

also encourage linkages that aid leadership development. Job rotations and related career development programs can be

designed with a network frame in mind. Overall, there are many ways in which network concepts associated with dyadic

and relational levels of analysis can facilitate addressing the challenges that are key to leadership development. Task,

career, and friendship/support networks can all be helpful in differential ways.

References

Avolio, B. J., & Kahai, S. (2003). Placing the

“E: in E-leadership: Minor tweak or fundamental change. In S. E. Murphy & R.E. Riggio (Eds.), The

future of leadership development Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bartol, K. M. (1978). The sex structuring of organizations: A search for possible causes. Academy of Management Review, 3, 805

−815.

Bartol, K. M., & Liu, W. (2002). Information technology and human resources management: Harnessing the power and potential of netcentricity.

Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 21, 215

−242.

Bartol, K. M., Martin, D. C., & Kromkowski, J. A. (2003). Leadership and the glass ceiling: Gender and ethnic group influences on leader behaviors

at middle and executive managerial levels. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 9(3), 8

−19.

Borgatti, S., & Foster, P. C. (2003). The network paradigm in organizational research: A review and typology. Journal of Management, 29,

991

−1014.

Borgatti, S. P., & Cross, R. (2003). A relational view of information seeking and learning in social networks. Management Science, 49, 432

−445.

Brass, D. J. (1985). Men's and women's networks: A study of interaction partners and influence in an organization. Academy of Management

Journal, 28, 327

−343.

Brass, D. J. (1995). A social network perspective on human resources management. In G. R. Ferris (Ed.), Research in Personnel and Human

Resources Management (pp. 39

−79). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Brass, D. J., & Krackhardt, D. (1999). The social capital of 21st century leaders. In J. G. Human, G. E. Dodge, & L. Wong (Eds.), Out-of-the-box

leadership (pp. 179

−194). Stamford, CT: JAI Press.

Brass, D. J., Betterfield, K. D., & Skaggs, B. C. (1998). Relationships and unethical behavior: A social network perspective. Academy of Management

Review, 23, 14

−31.

Brass, D. J., Galaskiewicz, J., Greve, H., & Tsai, W. (2004). Taking stock of networks and organizations: A multilevel perspective. Academy of Management

Journal, 47, 795

−817.

Bryson, J., & Kelley, G. (1978). A political perspective on leadership emergence, stability, and change in organizational networks. Academy of Management

Review, 3, 713

−723.

Burkhardt, M. E., & Brass, D. J. (1990). Changing patterns or patterns of change: The effects of a change in technology on social network structure

and power. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35, 104

−127.

Burt, R. S. (1982). Toward a structural theory of action. New York: Academic Press.

Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural hole: The social structure of competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cartwright, R. D. (1968). Psychotherapeutic processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 19, 387

−416.

Cialdini, R. B. (1993). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. New York: Quill William Morrow.

Cohen, R. A., & Bradford, D. L. (1989). Influence without authority: The use of alliances, reciprocity, and exchange to accomplish work.

Organizational Dynamics, 17(3), 5

−17.

Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge, MA: Belknap/Harvard University Press.

Combs, G. M. (2003). The duality of race and gender for managerial African American women: Implications of informal social networks on career

advancement. Human Resource Development Review, 2, 385

−405.

Cox, J. G., Pearce, C. L., & Sims, H. P., Jr (2003). Toward a broader leadership development agenda: Extending the traditional transactional

–

transformational duality by developing directive, empowering, and shared leadership skills. In S. E. Murph & R. E. Riggio (Eds.), The future of

leadership development (pp. 161

−179). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Cross, R., & Prusak, L. (2002, June). The people who make organizations go-or stop. Harvard Business Review, 105

−112.

Day, D. V. (2000). Leadership development: A review in context. Leadership Quarterly, 11, 581

−613.

Day, D. V., & O'Connor, P. M. G. (2003). Leadership development: Understanding the process. In S. E. Murphy, & R. E. Riggio (Eds.), The future of

leadership development Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Fisher, R., & Sharp, A. (1998). Getting it done: How to lead when you're not in charge. New York: HarperCollins.

Gardner, W. L., & Avolio, B. J. (1998). The charismatic relationship: A dramaturgical perspective. Academy of Management Review, 23, 32

−58.

Gibson, C. B., & Manuel, J. A. (2003). Building trust: Effective multicultural communication processes in virtual teams. In J. W. Sons (Ed.), Virtual

teams that work (pp. 59

−86). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Graen, G. B., & Scandura, T. A. (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Research in organizational behavior, 9, 175

−208.

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360

−1380.

Hamilton, B. A., & Scandura, T. A. (2003). E-mentoring: Implications for organizational learning and development in a wired world. Organizational

Dynamics, 31, 388

−402.

Higgins, M. C., & Kram, K. E. (2001). Reconceptualizing mentoring at work: A developmental network perspective. Academy of Management

Review, 26, 264

−288.

399

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

Hill, L. A. (1992). Becoming a manager: How new managers master the challenges of leadership. Cambridge, MD: Harvard Business School Press.

Hill, N. S., & Bartol, K. M. (2005). Making the herd drink: The role of organizational efficacy for change in innovation implementation. Paper

presented at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting, Honolulu, Hawaii.

Hughes, E. C. (1946). The knitting of racial groups in industry. American Sociological Review, 11, 512

−515.

Ibarra, H. (1992). Homophily and differential returns: Sex differences in network structure and access in an advertising firm. Administrative Science

Quarterly, 37, 422

−447.

Ibarra, H. (1993). Network centrality, power, and innovation involvement: Determinants of technical and administrative roles. Academy of Management

Journal, 36, 471

−501.

Ibarra, H. (1995, March 01). Managerial networks. Harvard Business School Cases, 1

−5.

Ibarra, H. (1995). Race, opportunity, and diversity of social circles in managerial networks. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 673

−703.

Ibarra, H. (1997). Paving an alternative route: Gender differences in managerial networks. Social Psychology Quarterly, 60, 91

−102.

Kilduff, M., & Krackhardt, D. (1994). Bringing the individual back in: A structural analysis of the internal market for reputation in organizations.

Academy of Management Journal, 37, 87

−108.

Kilduff, M., & Tsai, W. (2003). Social networks and organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Klein, K. J., Lim, B., Saltz, J. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2004). How do they get there? An examination of the antecedents of centrality in team networks.

Academy of Management Journal, 47, 952

−963.

Kotter, J. P. (1982). The general managers. New York: Free Press.

Kotter, J. P. (1995, March

–April). Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review, 59−67.

Krackhardt, D., & Kilduff, M. (2002). Structure, culture, and Simmelian ties in entrepreneurial firms. Social Networks, 24, 279

−290.

Kram, K. E. (1985). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

Kram, K. E., & Isabella, L. A. (1985). Mentoring alternatives: The role of peer relationships in career development. Academy of Management

Journal, 28, 110

−132.

Labianca, G., Brass, D. J., & Gray, B. (1998). Social networks and perceptions of intergroup conflict: The role of negative relationships and third parties.

Academy of Management Journal, 41, 55

−67.

Lamertz, K., & Aquino, K. (2004). Social power, social status and perceptual similarity of workplace victimization: A social network analysis of

stratification. Human Relations, 57, 795

−822.

Lin, N. (1999). Social networks and status attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 467

−487.

Luthans, Fred. (1988). Successful vs. effective real managers. Academy of Management Executive, 2, 127

−132.

McCauley, C. D., & Douglas, C. S. (1998). Developmental relationships. In C. D. McCauley, R. S. Moxley, & E. Van Velsor (Eds.), The Center for

Creative Leadership handbook of leadership development (pp. 160

−193). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

McCauley, C. D., Ruderman, M. N., Ohlott, P. J., & Morrow, J. E. (1994). Assessing the developmental components of managerial jobs. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 79, 544

−560.

McDonald, M. L., & Westphal, J. D. (2003). Getting by with the advice of their friends: CEO's advice networks and firms' strategic responses to poor

performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 48, 1

−32.

McGuire, G. M. (2000). Gender, race, ethnicity, and networks: The factors affecting the status of employees' network members. Work and Occupation,

27, 501

−523.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415

−444.

Martins, L. L., Gilson, L. L., & Maynard, M. T. (2004). Virtual teams: What do we know and where do we go from here? Journal of Management,

30, 805

−835.

Mehra, A., Kilduff, M., & Brass, D. J. (1998). At the margins: A distinctiveness approach of the social identity and social networks of underrepresented

groups. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 441

−452.

Mehra, A., Kilduff, M., & Brass, D. J. (2001). The social networks of high and low self-monitors: Implications for workplace performance. Administrative

Science Quarterly, 46, 121

−146.

Mollica, K. A., Bray, B., & Trevino, L. K. (2003). Racial homophily and its persistence in newcomers' social networks. Organization Science, 14, 123

−136.

Morrison, E. W. (2002). Newcomers' relationships: The role of social network ties during socialization. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 1149

−1160.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23, 242

−266.

Neubert, M. J., & Taggar, S. (2004). Pathways to informal leadership: The moderating role of gender on the relationship of individual differences and

team member network centrality to informal leadership emergence. Leadership Quarterly, 15, 175

−194.

Oh, H., Chung, M., & Labianca, G. (2004). Group social capital and group effectiveness: The role of informal socializing ties. Academy of Management

Journal, 47, 860

−875.

Ohlott, P. J. (1998). Job assignments. In C. D. McCauley, R. S. Moxley, & E. Van Velsor (Eds.), The Center for Creative Leadership handbook of

leadership development San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Pearce, C. L., & Conger, J. A. (Eds.). (2003). Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Pearce, C. L., & Sims, H. P., Jr (2000). Shared leadership: Toward a multi-level theory of leadership. Advances in interdisciplinary studies of work

teams, 7, 115

−139.

Pearce, C. L., & Sims, H. P., Jr (2002). Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: An

examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leadership behaviors. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research,

and Practice, 6, 172

−197.

Podolny, J. M., & Baron, J. N. (1997). Relationships and resources: Social networks and mobility in the workplace. American Sociological Review,

62, 673

−693.

Powell, W. S., Koput, K., & Smith-Doerr, L. (1996). Interorganizational collaboration and the locus of innovation: Networks of learning in

biotechnology. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41, 116

−145.

400

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

Ragins, B. R., & Cotton, J. L. (1991). Easier said than done: Gender differences in perceived barriers to gaining a mentor. Academy of Management

Journal, 34, 939

−951.

Roland, E. K., Kevin, W. M., & Nathan, B. (1997). Cohesiveness and organizational citizenship behavior: A multilevel analysis using work groups

and individuals. Journal of Management, 23, 775

−793.

Rothstein, M. G., & Davey, L. M. (1995). Gender differences in network relationships in academia. Women in Management Review, 10, 20

−25.

Seibert, S. E., Kraimer, M. L., & Liden, R. C. (2001). A social capital theory of career success. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 219

−237.

Sidle, C. C., & Warzynski, C. C. (2003, Sept./Oct.). A new mission for business schools: The development of actor-network leaders. Journal of Education

for Business, 40

−45.

Singh, R. P., Hybels, R. C., & Hills, G. E. (2000). Examining the role of social network size and structural holes. New England Journal of Entrepreneurship,

3, 47

−59.

Sparrowe, R. T., Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Karimer, M. L. (2001). Social networks and the performance of individuals and groups. Academy of Management

Journal, 44, 316

−325.

Uhl-Bien, M., Graen, G. B., & Scandura, R. A. (2000). Implications of leader

–member exchange (LMX) for strategic human resource management

systems: Relationships as social capital for competitive advantage. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 18, 137

−185.

Van Velsor, E. V., McCauley, C. D., & Moxley, R. S. (1998). Our view of leadership development. In C. D. McCauley, R. S. Moxley, & E. Van Velsor

(Eds.), The Center for Creative Leadership handbook of leadership development (pp. 1

−25). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Webber, C. F. (2003). Technology-mediated leadership development networks: Expanding educative possibilities. Journal of Education of Administration,

41(2), 201

−218.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Westphal, J. D., & Milton, L. P. (2000). How experience and network ties affect the influence of demographic minorities on corporate boards.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 45, 366

−398.

Yukl, G. (2002). Leadership in organizations, Fifth Ed. Egnlewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

401

K.M. Bartol, X. Zhang / Human Resource Management Review 17 (2007) 388

–401

Document Outline

- Networks and leadership development: Building linkages for capacity acquisition and capital acc.....

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Mental Toughness for Peak Performance Leadership Development and Success

MalwareA Future Framework for Device, Network and Service Management

A neural network based space vector PWM controller for a three level voltage fed inverter induction

Piórkowska K. Cohesion as the dimension of network and its determianants

An Optically Isolated Hv Igbt Based Mega Watt Cascade Inverter Building Block For Der Applications

Global Production Networks and World City Network

From Stabilisation to State Building, (DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL?VELOPMENT)

van leare heene Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

taking stock of networks and organizations a multilevel approach

social networks and the performance of individualns and groups

Email networks and the spread of computer viruses

Production networks and consumer choice in the earliest metal of Western Europe

HP Networking and Cisco CLI Reference Guide June 10 WW Eng ltr

kraatz learning by association interorganizational networks and adaptation to environmental change

intra organizational networks and performance

social networks and planned organizational change the impact of strong network ties on effective cha

Social Networks and Negotiations 12 14 10[1]

managing collaboration within networks and relatioships

więcej podobnych podstron