PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

This article was downloaded by:

[Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield]

On:

5 February 2011

Access details:

Access Details: [subscription number 928381337]

Publisher

Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-

41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Norwegian Archaeological Review

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713926118

Defusing Dualism: Mind, Materiality and Prehistoric Art

Vesa-Pekka Herva; Janne Ikäheimo

Online publication date: 05 November 2010

To cite this Article

Herva, Vesa-Pekka and Ikäheimo, Janne(2002) 'Defusing Dualism: Mind, Materiality and Prehistoric

Art', Norwegian Archaeological Review, 35: 2, 95 — 108

To link to this Article: DOI:

10.1080/002936502762389729

URL:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/002936502762389729

Full terms and conditions of use:

http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or

systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or

distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents

will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses

should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss,

actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly

or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Defusing Dualism: Mind, Materiality and

Prehistoric Art

V

ESA-

P

EKKA

H

ERVA AND

J

ANNE

I

KA¨HEIMO

How do archaeologists assign meanings to prehistoric art objects? Ancient art

is often understood in terms of communication and expression, whereas other

than purely visual meanings of art are seldom promulgated. Art is often

associated with survival, religion and identity — the ‘big issues’ of social life

— but some art objects may have been specimens of everyday material

culture. In this article it is shown that the rejection of the dualistic mode of

thinking — dichotomies between medium/message and symbolic/practical —

opens up an alternative perspective on the meaning of prehistoric art.

INTRODUCTION

Prehistoric art is consistently understood in

terms of expression, as a re ection of the

world understanding of ancient people.

Therefore, the decoding of visual images

embodied by art objects is often the focus of

archaeology. The purpose of this paper,

however, is to highlight the importance of

art objects as material things instead of

treating them as references to something else.

With this perspective on art, we do not seek to

replace the more familiar ‘images as mes-

sages in society’ approach (Nordbladh 1978),

but to demonstrate that the aforementioned

approach does not adequately cover the

multitude of roles material culture may play

in society.

It is being recognized that the dualistic

mode of thinking prevents us from properly

understanding non-Western societies (e.g.

Descola & Pa´lsson 1996, Bru¨ck 1999, Ingold

2000a). As to the interpretation of prehistoric

art, dualistic notions — the medium/message

and symbolic/practical dichotomies in par-

ticular — are equally relevant. As an indirect

result of dualism, prehistoric art is more often

than not related to the ‘big issues’ of social

life in the past, particularly to religious beliefs

and ritual practices (cf. Coles 1995). It will be

argued here, however, that the dualistic mode

of thinking may result in misconceptions

about life in ancient societies.

In the following discussion, the need for a

shift from the expressive paradigm of art to a

material-culture perspective is explained.

Then, the relevance of this approach is

demonstrated through the interpretation of a

small elk-head gurine recovered from a

Bronze Age dwelling site of Hangaskangas,

located in Northern Ostrobothnia, Finland.

However, the present paper is more of an

exercise in developing an alternative perspec-

tive on prehistoric art than a painstaking

attempt to assign a meaning to a single object.

MODERN AND PREHISTORIC ART

In archaeology, it is readily acceptable that

prehistoric ‘art objects’, i.e. artefacts incor-

porating visual images, differ from the

modern works of ‘ ne art’. Attempts have

Vesa-Pekka Herva and Janne Ika¨heimo, Department of Archaeology, University of Oulu, Finland.

E-mail: maherva@paju.oulu.fi ; janne.ikaheimo@oulu.f i

Norwegian Archaeological Review, Vol. 35, No. 2, 2002

ARTICLE

# 2002 Taylor & Francis

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

been made to de ne the idea of art (Gell

1996:15–17, Carroll 1999:206–266), but re-

gardless of the preferred de nition, there still

seems to be a stark contrast between the post-

Renaissance, or rather post-18th century art

and prehistoric art. In general, art is asso-

ciated with aesthetic value and individual

ingenuity — art pursues novelty. But as this

conception of art emerged only in the 18th

century (Shiner 2001), prehistoric art objects

evidently operated within another frame of

reference. Although this is widely acknow-

ledged today (e.g. Conkey 1987:413, Hays

1993:89, Renfrew 1994:265–266), the rela-

tion between modern and prehistoric art is far

from being a clear one.

The modern conception of prehistoric art is

built largely on straightforward notions of

cultural evolution. The customary thought in

archaeology and art history is that all art

before the Renaissance was functional, as

opposed to aesthetic, and that prehistoric art,

in particular, served ritual and religious

purposes (e.g. Hall 1983:3, Salo 1984:177,

Barasch 1985:45–46, Crowley 1989:2–3,

Huurre 1998:278). Hence, the current under-

standing of prehistoric art is heavily over-

shadowed by the modern idea of art. To put it

simply, prehistoric art is polarized to modern

art. Because ‘aestheticity’ and ‘secularity’ are

the values assigned to modern art, prehistoric

art is designated as ‘functional’ and ‘religi-

ous’. From today’s perspective, the develop-

ment of artistic expression appears to have

been linear and seemingly predictable —

from ‘craft’ to ‘Art’ — all the way from the

Middle/Upper Palaeolithic transition (cf.

Taylor 1994:251–252, Danto 1997, Ingold

2000b: 130–131). However, Art with a capital

A was invented in the 18th century, and craft

is also a value-laden Western construction.

Hence, the conceptual polarization between

the two is a product of modernity (Shiner

2001).

None the less, prehistoric art is commonly

described as ‘functional’ and ‘religious’, but

are these designations of any analytical

value? Interpretations of Palaeolithic cave

art, for instance, tend to stress its functionality

by connecting the images with complex

religious/metaphysical,

i.e.

‘symbolically

practical’ purposes. The logic of strictly

functional interpretations of cave art seems

to be the following: if art was not bene cial in

terms of survival, it would not have been done

in the rst place, not at least to any

remarkable extent. But the reason for reject-

ing the ‘art for art’s sake’ hypothesis may be

the scholarly desire to link cave art to the ‘big

issues’ of Palaeolithic life, the desire to

illuminate the key issues of the distant past

through art. The ‘art for art’s sake’ inter-

pretation of Palaeolithic art, on the other

hand, neither implies that Palaeolithic art

should be viewed similarly as ne art nor that

art was utterly non-functional, but it chal-

lenges the nature of functionality. The making

of cave art could have been a kind of play that

was related to the development of cognitive

abilities (Halverson 1987).

Ultimately, both ‘functionality’ and ‘re-

ligiousness’ fail adequately to characterize

prehistoric art. First, all art, modern or pre-

modern, serves a myriad of purposes; func-

tionality is a matter of de nition. Second, all

objects and activities are ‘religious’ or

‘cosmological’ in the sense that they neces-

sarily preserve one’s conceptions of ef cient

action, re ecting/reproducing the world-view

in general. But to accept this is quite different

from claiming that ‘religious beliefs’ primar-

ily promoted the manufacture and use of

prehistoric art objects.

THE EXPRESSIVE PARADIGM OF ART

The dominant tradition in art history and

aesthetic philosophy has conceptualized art

objects

as vehicles of communication and

expression (Preziosi 1998:15) and privileges

the ‘message’ conveyed by art. This concep-

tion also prevails in archaeology, and thus the

interpretation of prehistoric art tends to be

iconocentric. The archaeology of art focuses

on the decipherment of the visual code that

images are presumed to embody. One might

96 Vesa-Pekka Herva and Janne Ika¨heimo

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

expect archaeologists, who usually operate

with material remains, to treat a prehistoric art

object primarily as a thing in itself, not as a

reference to something else. This is seldom

the case (Taylor 1994:252) and the conse-

quences are far from being insigni cant.

The linguistic paradigm of art operates at

two levels. While images are thought to

constitute a visual language, the ‘linguistic

turn’ in the social sciences made it possible to

treat material culture in general as a system

of signs. The latter idea has been heavily

in uenced by the development of semiotics

(Miller 1987:95–96). Within this linguistic

paradigm, expression is considered to be the

primary function of both modern and pre-

historic art. The only difference is in the type

of conveyed messages. Modern art is thought

to express the ideas, values, emotions, etc., of

an individual artist, whereas prehistoric art is

assumed to manifest the values and ideas

collectively shared by all members of

society.

But art is not solely about symbolic

communication, as it has also a practical

mediatory role in social interaction (Gell

1998). Still, art can be thought in terms of

expression or communication because, ob-

viously, people often attach meanings to

artefacts. Objects do have sign-values, but

they are differently signi ed from words and

sentences. In principle, words have xed

meanings, whereas objects and images can

be seen either as signs or concrete things. The

spectator chooses the aspect that is relevant in

a given situation (Barasch 1997:83–86).

Objects can also combine several, even

mutually contradictory, meanings in a so-

cially accepted fashion. An artefact may be a

status object to some and a source of ridicule

to others (Miller 1987:107–108). In brief, the

Peircean theory of the sign that emphasizes

the role of the interpreter appears to model the

signifying process of material culture better

than the Saussurean theory, which eliminates

the signi cance of the individual (cf. Potts

1996, Preucel & Bauer 2001). As to the

interpretation of visual images, the usefulness

of linguistic analogy is limited by the fact that

images cannot be divided into units in the

same way as a text can be split up into words

and phrases. In all known systems of visual

representation the relation between visual

designs and their meanings does not match

with the close relation of words and their

meanings (Potts 1996:22).

An unfortunate consequence of the me-

dium/message dualism is the decontextual-

ization of prehistoric art (Last 1998). Images

are conceptually detached from objects and

objects are violently detached from their

archaeological contexts. The dominant ap-

proach to prehistoric art, iconographic analy-

sis, operates with detached images and thus

tends to neglect archaeological context and

sequence (Whitley 1991:18–19). Because

images are considered to re ect collective

ideas and values, no special signi cance is

attributed to the fact that images embodied by

different types of artefacts may be recovered

from a variety of archaeological contexts.

The problem with the Western iconocen-

trism is that sometimes images lack an

expressive dimension. The Za maniry of

Madagascar, for example, carve the wooden

parts of their houses in geometrical patterns

(Bloch 1995). These carvings, which were at

rst thought to express indigenous mythologi-

cal narratives, did not comprise a system of

iconographic meanings at all. The purpose of

the carvings is to make the wood beautiful.

They do not refer to or signify anything as

such; rather, ‘the carvings are a celebration of

the material, and the building and of a

successful life which continues to expand

and reproduce’ (Bloch 1995:215). Rather than

representing a social process, the carvings

formed an essential part of it. Only the

making of carvings gave them meaning.

The richly carved Trobriand canoe prow-

boards serve as another example. Although

these decorated boards are not intended to

represent or refer to anything, they are still

powerful social agents (Gell 1992). The

boards constitute a psychological weapon in

Kula exchanges, as they are the rst things the

Mind, Materiality and Prehistoric Art

97

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

Trobriand’s trading partners see of the com-

ing otilla. The purpose of the impressive

carvings is to demoralize the potential

opposition through powerful magical associa-

tions and to gain better bargains. ‘A prow-

board is an index of superior artistic agency,

and it demoralizes the opposition because

they cannot mentally encompass the process

of its origination’ (Gell 1998:70–71). As

demonstrated by these examples, the meaning

of art objects is not always obvious.

BEYOND EXPRESSION AND THE

SYMBOLIC

Prehistoric art objects are often treated as

inherently religious artefacts. Animal-headed

objects, for instance, have atmospherically

been described as

the most human pieces of evidence reflecting both

the skilful hands and plastic forming, but besides

aesthetic aims very probably also the rites of

society, worship and pantheon, that is, such

mental dimensions we cannot observe from blades

or potsherds. These sacred objects reflect the

cosmology of the hunter, which remained the

same for several millennia (Salo 1984:177, our

translation).

The success of this idea depends, again, on

the dualistic mode of thinking. Pots and axes

are thought of in terms of practical engage-

ment in the world, whereas art objects are

seen to operate in the domain of the symbolic.

There is a tendency to assume that function-

ality is, at least in most cases, obvious: we see

tools like a knife and instantly know what it is

for (Graves-Brown 1995:10). A ‘symbolic’ or

‘expressive’ function is assigned to art objects

because — unlike scrapers, adzes, axes, etc.

— they appear to lack a ‘practical’ function.

Necessarily, then, the activities clustering

around art objects are also designated as

‘symbolic’ and ‘expressive’ of nature. Such

practices are usually associated with ‘ritual’,

but there are two important objections to this

conception.

First, the function of art objects is not self-

evident, as the cases of Za maniry houses and

Trobriand canoes indicate. Notions of func-

tionality regulate the actions employing

artefacts; give a modern gadget to ancient

Joe Average and he would probably conceive

it as a non-utilitarian object. Similarly, most

non-Americans would not gure out what a

chip clip (a clip used to re-seal an opened bag

of chips) was actually designed for because

the thing only makes sense in a speci c social

context. It is less obvious, however, that the

functions of all objects are historically or

socially speci c despite the fact that familiar

forms persuade us to assign familiar functions

to them (see Graves-Brown 1995:14). In a

sense, prehistoric art objects deceive us by

virtue of their iconicity:

In sum, because optically illusionistic pictures

stand as paradigmatic exemplars of all ‘Art’ for

us, and those exemplars have an iconic content,

iconicity assumes and overlarge place in the

unconscious assumptions we make when looking

at other humans’ artefacts we have designated

‘Art’. (It is also true, I am sure, that when we

survey the artefacts produced by other human

cultures, we tend to select those with an iconic

content over and above those without it to

designate as ‘art’). Once selected, we tend to read

them as though their iconic content were their

main mode of meaning in the world. Hence

iconocentrism works overtime to inhibit our

understandings of the other ways that humans’

artefacts may mean (Errington 1991:270) .

Thus, it is misleading to assume a priori that

the understanding of prehistoric art objects is

achieved through the decoding of iconic

content. One tends to assume that art objects

gain meaning because they are looked at

rather than, say, touched.

The second objection concerns the overall

meaningfulness of the symbolic/practical and

ritual/secular dichotomies. Anthropologists

and archaeologists tend to cast non-Western

societies in a Western mould by taking these

divisions for granted. In many societies,

symbolic and expressive social practices, as

we understand them, are considered as

perfectly logical and practical ways of affect-

98 Vesa-Pekka Herva and Janne Ika¨heimo

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

ing on the world. Only in modern Western

society, which privileges mechanical causal-

ity, is ritual separated from rationality and

effective from expressive action (Bru¨ck

1999). In the context of secularized academia,

beliefs seems to constitute the essence of

religion, but when religion does not form a

separate discourse of life, people are con-

cerned with practice rather than beliefs and

the symbolic (Miller & Slater 2000:174–175).

Religion in non-Western societies is best

understood as a form of technology (Gell

1988), and ‘ritual’ practices should not be

categorically separated from other activities.

This does not imply homogeneity of all social

practices, but emphasizes the need to strive

for the indigenous categories of activities

(Bru¨ck 1999).

HUMAN/ANIMAL RELATIONS IN

PREHISTORIC FENNOSCANDIA

The interpretations of Fennoscandian prehis-

toric animal representations, most notably

rock imagery, are mainly built on the

expressive paradigm of art. Rock art is often

comprehended as an expression of prehis-

toric religion and social organization, while

osteological data are treated in terms of

rational economy (e.g. Higgs & Jarman

1975, Siiria¨inen 1981). For example, in Fin-

land, the bone remains of Mesolithic sites are

predominantly those of elk, beaver and seal

(Huurre 1998:154–156), while in the Neo-

lithic period (cal. 5100 BC–1900 BC) —

marked by the introduction of pottery rather

than agriculture — the percentage of elk bones

becomes greatly decreased in coastal sites as

the seal begins to dominate the osteological

record (Matiskainen 1989:49). Although this

change may imply that the elk population had

been exploited almost to extinction (Siiria¨i-

nen 1981), coastal societies may also have

specialized in sealing because of its high

productivity (Huurre 1998:154–156). It is

equally possible, however, that the ways of

treating killed elk changed to some extent.

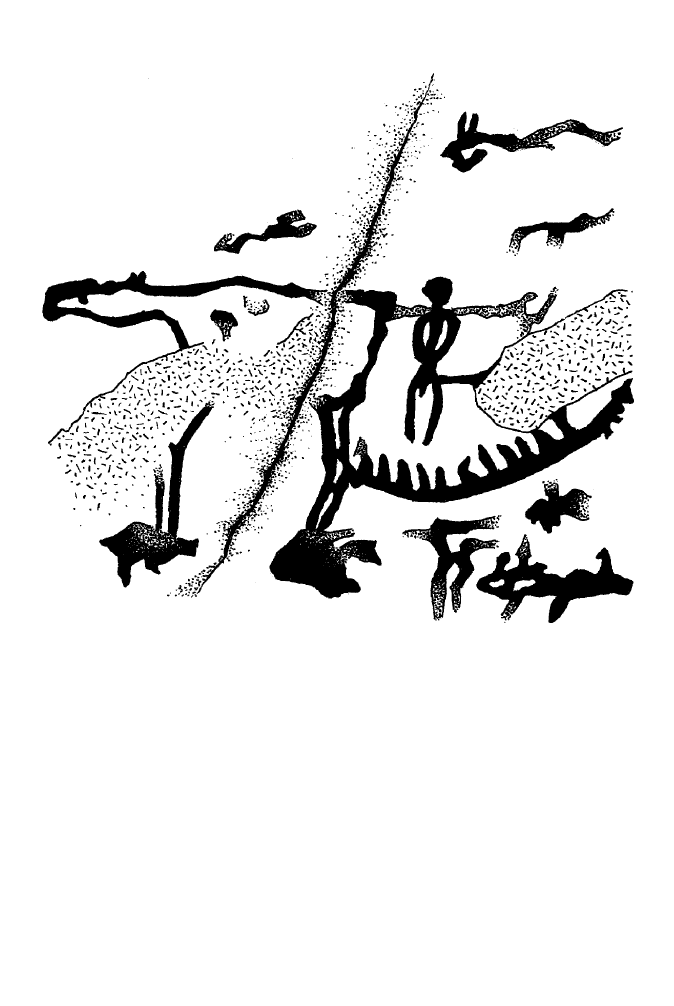

In Finnish rock art, which at present

consists exclusively of paintings, the elk and

the human are the most frequently repre-

sented motifs (Fig. 1). Human representations

comprise approximately 40%, elk about 25%

of the total number of motifs (Miettinen

2000:49–56). All other motifs appear far

more infrequently, the proportion of the third

common motif, the so-called boat, is approxi-

mately 10%. The dominance of human/elk

imagery has usually been seen as a document

of hunting magic and the central position of

this animal in the Stone Age cosmology (e.g.

Taavitsainen 1978). For example, the use of

rock art panels as targets of ritual shooting

offers a convenient explanation for the two

prehistoric arrowheads found under water in

front of the Astuvansalmi rock painting at

Ristiina, Eastern Finland (see Gro¨nhagen

1994). Still, the idea of sympathetic magic

is not greatly favoured today.

In addition to hunting magic, totemism

and shamanism are the other two broad

frames of reference in the interpretation of

prehistoric art. The totemic interpretation, in

turn, has recently gained support in Scandi-

navia (e.g. Hesjedal 1994, Sognnes 1994),

and the relation between totemism and rock

art has been discussed also in Finland (e.g.

Siiria¨inen 1981:26–27, Autio 1995). None

the less, hunting magic hypothesis and

shamanistic interpretation of rock art (e.g.

Siikala 1980, Nu´n˜ez 1995, Lahelma 2000)

seem to prevail. Apart from few exceptions

(e.g. Lahelma 2000), prehistoric art has so

far been studied rather unsystematically in

Finland, where, more often than not, differ-

ent frames of reference are merged. Yet

human/animal relations in totemic societies

differ fundamentally from human/animal

relations in animistic societies. The contrast

is also re ected in the meaning of animal

representations (Ingold 2000b). For exam-

ple, the activity of making depictions is

important to totemic Australian Aboriginal

societies and the ‘ nished artifact’ is under-

stood as a static locus of power. By contrast,

the making of animal depictions is a quick

process in Alaskan animistic societies and art

Mind, Materiality and Prehistoric Art

99

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

objects come to life only when ‘ nished

artifacts’ are used in ceremonies (Ingold

2000b:127–130).

Conventional iconocentric approaches to

prehistoric art certainly have some merits, but

unfortunately they clearly reduce art objects

to mere re ections of world-understanding

and social order. Art is seen to mirror the ‘big

issues’ of prehistoric life, and to some degree

this is what art does. The expressive paradigm

of art, however, is essentially reductive in

neglecting situated practice for the sake of

social superstructure. Although the elk un-

doubtedly had a position in Fennoscandian

prehistoric cosmologies, it makes little sense

to claim that all elk representations aimed to

reproduce some normative conceptions re-

lated to this animal.

Fig. 1. A detail of the Astuvansalmi rock painting showing the three most characteristic motifs in

Finnish rock art: an elk, an anthropomorphi c figure and a ‘boat-motif’. This painting, which is dated to

the Neolithic/Bronze Age, is among the largest in Finland (15 £ 3 m) and contains approximately 65

figures. Scale ca. 1:10. Drawing: V.-P. Herva (after Kivika¨s 1995:56)

.

100 Vesa-Pekka Herva and Janne Ika¨heimo

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

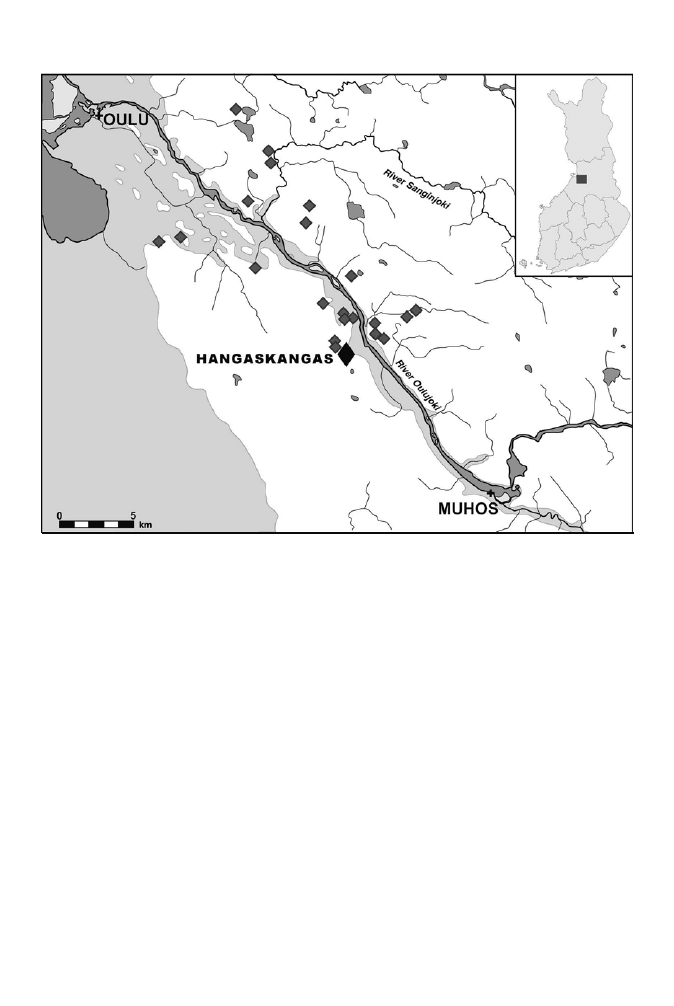

UNDERSTANDING THE

HANGASKANGAS ELK

The object used as an example to illustrate the

multifaceted nature of prehistoric art in this

study comes from Muhos Hangaskangas, an

Early Bronze Age site, some 20 km SE of the

city of Oulu (Fig. 2). The site was rst

discovered in 1926, when the constructors of

the Oulu–Kajaani railroad found a stone adze.

Cooperation between the Museum of North-

ern Ostrobothnia and the Department of

History at Oulu University led to archae-

ological excavations being set up at the site in

1968. The result of a nine-day campaign was

a rich collection of artefacts including several

fragments of a clay crucible and four

fragmentary straight-based arrowheads, while

the majority of nds represented lithic debris.

A piece of chewing resin (National Museum

of Finland 17646:163) found in the 1968

excavations has recently been dated using the

AMS-method to the Early Bronze Age (Hela–

154, BP 3420 § 105, cal. 1860–1580 BC).

In 1998–1999 and 2002, the site was

chosen as the focus of the Archaeological

Test Excavation Group formed under the

supervision of the Department of Art Studies

and Anthropology, University of Oulu. The

total extent of these three small-scale cam-

paigns was just 35 m

2

, as opposed to some

140 m

2

excavated in 1968. Still, despite

Fig. 2. The location of Muhos Hangaskangas and other dwelling-sites in the lower Oulujoki River valley

at the end of the Bronze Age, ca. 500 BC, when the sea level was at a 20-m altitude above the present.

Drawing: J. Ika¨heimo

.

Mind, Materiality and Prehistoric Art

101

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

improved archaeological research methods,

no evidence of actual dwellings was discov-

ered at the site. Furthermore, the livelihood of

the inhabitants remains somewhat obscure, as

the osteological data are limited to a few

severely deteriorated lumps of bone. In all,

the some 2500 nds made during the recent

campaigns are practically identical to the

material recovered in the 1968 excavations,

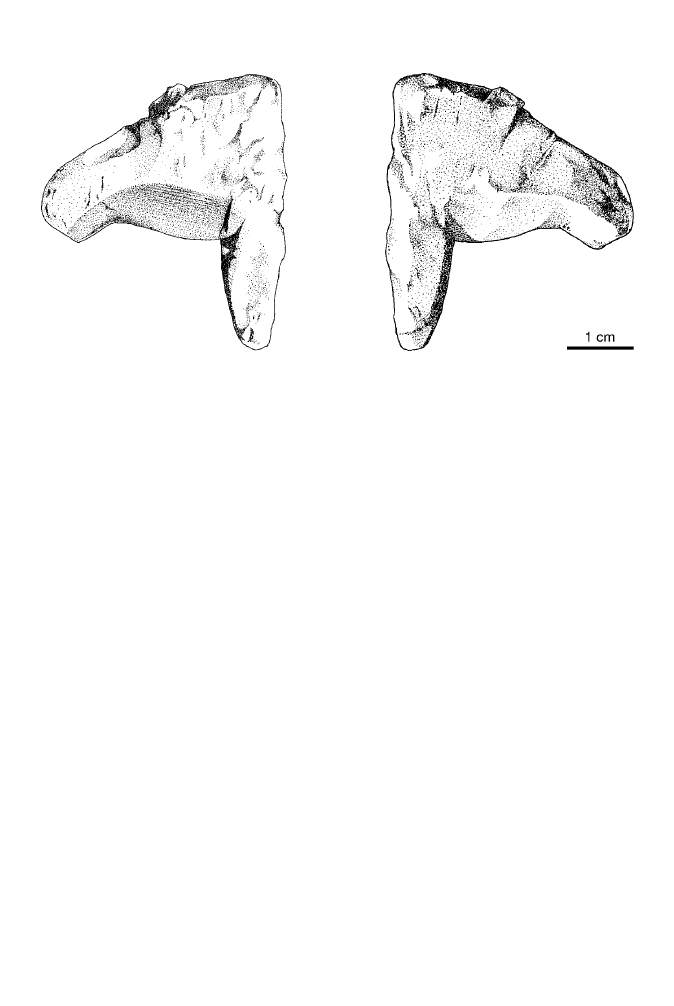

with one exception: a miniature elk-head

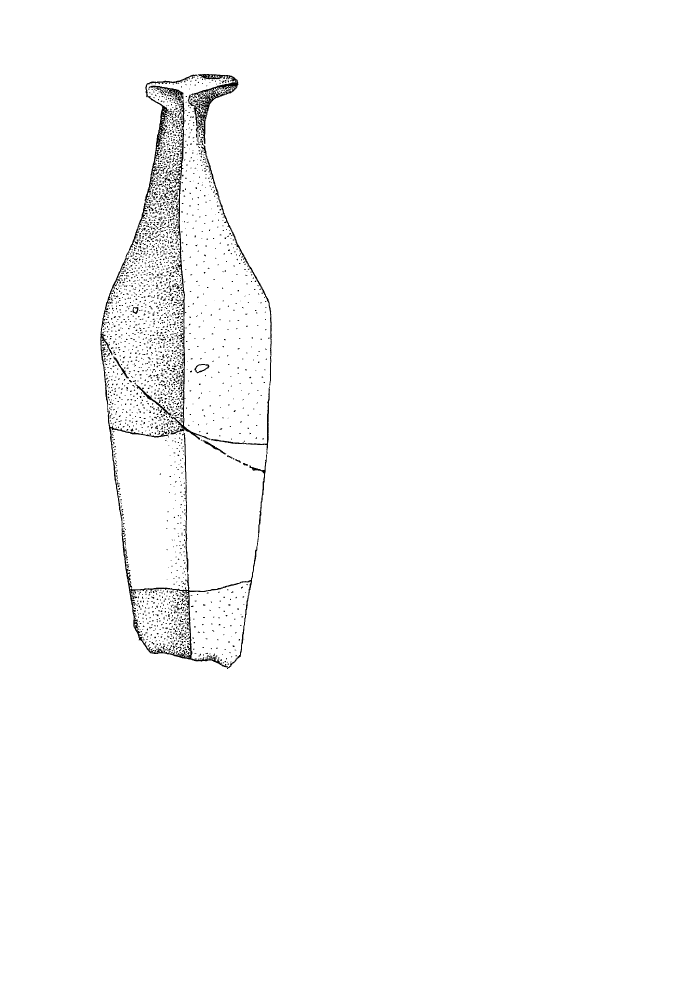

carved from a piece of talc (Fig. 3). The

gurine seems to be fairly complete; there is

no indication that it formed a part of an elk-

headed knife or other utilitarian object.

Dozens of plastic animal representations —

which often decorate axes, knives, spoons or

other ‘utilitarian’ objects (Fig. 4) — have

been found in the geographical area extending

from Fennoscandia to the Urals (e.g. Mei-

nander 1964, Carpelan 1974, 1977), usually

interpreted as ‘status symbols’ or ‘parapher-

nalia’ (e.g. Huurre 1998:293). These repre-

sentations are usually carved in stone, but

wood, antler, clay, bronze and amber have

also been used. The majority are random

nds, but some have been recovered from the

excavations of dwelling sites (Carpelan

1974:32–34). The earliest examples date to

the Mesolithic, but most pieces are probably

Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (Carpelan 1974).

Despite the relative abundance of plastic

animal representations, there are no proper

parallels to the Hangaskangas elk in the

Finnish archaeological record. In principle,

the Hangaskangas elk could have been a part

of an (un nished) animal-headed stone-knife

(cf. Meinander 1964), but the shape (and raw

material) of the item does not support this

hypothesis. Hence, the elk-head must be

treated as a complete artefact in itself. In

comparison to anthropomorphic gurines,

animal gurines are remarkably rare in Fin-

land (Fig. 5). The elk is represented in one

clay gurine only. A snake, a bear and a few

unidenti ed clay gurines are also known

(Huurre 1998:294–295). In addition, an

amber gurine, possibly depicting a bear,

was found during the underwater excavations

at the Astuvansalmi rock art site (Gro¨nhagen

1994). Finally, there are some schematic

Fig. 3. The modest dimensions (41 £ 31 £ 16 mm) of the Muhos Hangaskangas elk-head, certainly

qualifies it as a miniature object. Talc is very soft and easy to carve, and a suitable raw material for

figurines of this kind. Its style is somewhat impressionistic—an incorrect but illuminative metaphor —

because the object has been executed with a few rapid strokes and lacks polished surfaces. As the object

is flat, the depiction of the elk takes shape only when viewed from the side. Drawing: V.-P. Herva

.

102 Vesa-Pekka Herva and Janne Ika¨heimo

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

animal-heads carved in stone (Edgren 1984:

61–62).

The rough appearance is the only formal

feature connecting these artefacts to the

Hangaskangas elk, but, on the other hand,

the sketchy form may actually be the key to

understanding the artefact. It is interesting to

note that the other schematic animal repre-

sentations are believed to have been deposited

as a result of ritual action (Edgren 1984:61–

62). This interpretation is based on the idea

that ‘symbolic’ objects did not need to be

embellished, but the ritual deposition of an

animal-head object cannot be accepted unless

it is supported by the archaeological context

(Fig. 6). The question arises, then, whether or

not the Hangaskangas elk should be consid-

ered as a religious or ritual object.

It is possible, of course, that the deposition

of the Hangaskangas elk was an occasion of

some special signi cance, but the context

actually implies that the object was either lost

or casually discarded. As one does not readily

lose one’s valuables, these possibilities sug-

gest that the artefact as a ‘ nished object’ was

of little value. Moreover, the rough appear-

ance of the artefact suggests that little energy

was invested in its making. The Hangaskan-

gas elk may have served, for example, as a

toy, which is the function suggested for some

gurines by many scholars (e.g. Meskell

1995:82, Huurre 1998:294). Another and

perhaps somewhat more appealing possibility

is that the meaning of the Hangaskangas elk

derived from the making-process itself, and

the resulting object was a mere ‘by-product’.

The making of the gurine could have been a

kind of ‘meditative’ act, which was important

because of personal, psychological reasons.

Following Le´vi-Strauss (1962), we would

assert — without any deeper implications —

that ‘animals are good to think’. Rather than

referring to the ‘external’ world, reproducing

it in a ‘symbolic’ fashion, the making of the

elk gurine may best be understood as a

means of pursuing a deeper knowledge of the

world in which the prehistoric ‘artist’ lived

(also cf. Ingold 2000b). Thus, the Hangas-

kangas elk can be seen to document an

essentially practical engagement in the world.

The Hangaskangas elk can be understood

in terms of everyday material culture, which

is ordinary and invisible, not actively calling

attention to itself (Att eld 2000:1–20). While

Fig. 4. A Late Neolithic slate knife from Tervola

To¨rma¨vaara, SW Lapland. The artefact is deco-

rated with a schematic elk-head, but contrary to

the Hangaskangas elk, all of its surfaces have

been polished. Scale ca. 4:5. Drawing: V.-P.

Herva (after Edgren 1984:62)

.

Mind, Materiality and Prehistoric Art

103

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

‘residually’ re ecting them, the Hangaskan-

gas elk — its making, use and deposition —

did not primarily articulate the matters of

survival, identity or power. This idea is

strengthened by the notion that artefacts that

play a marginal role in social interaction may

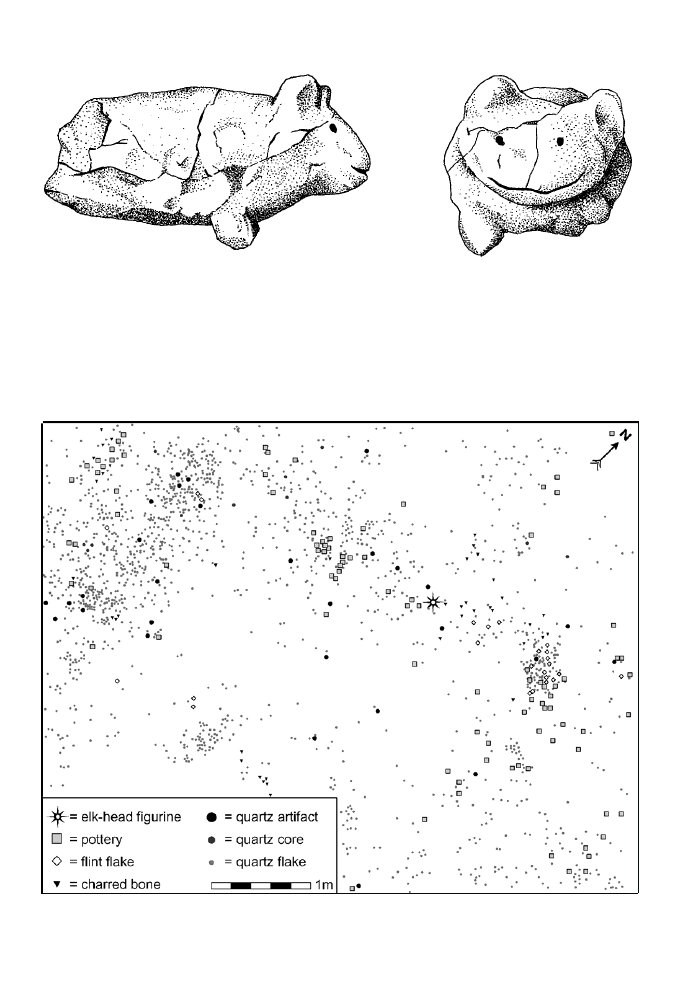

Fig. 5. A bear (?) figurine from Luopioinen (SW Finland) is one of the few clay animal figurines dated

to the Neolithic/Bronze Age. Scale ca. 2:1. Drawing: V.-P. Herva (after Huurre 1998:295)

.

Fig. 6. The Hangaskangas elk is associated with quartz flakes and potsherds, the typical debris at

Finnish Stone Age/Bronze Age dwelling sites. Drawing: J. Ika¨heimo.

104 Vesa-Pekka Herva and Janne Ika¨heimo

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

be less elaborated than those contributing to

the formation of self-image (Wiessner 1989,

1990). In our view, the artefact was not

important as a sign in a system of symbols. In

prehistoric Fennoscandia, cosmological con-

ceptions were certainly associated with the

elk, but it is simplistic to assume that all elk

representations were simply aimed at repro-

ducing some normative cultural ideas. Ob-

jects that are similar in form may have

different functions and meanings in any

society, as studies on prehistoric anthropo-

morphic gurines clearly indicate (e.g. Ucko

1968, Talaley 1993, Meskell 1995).

The case of the Hangaskangas elk serves

to illustrate that all art objects do not

primarily document the ‘big issues’ of social

life, even though the standard interpretations

of prehistoric art tend to emphasize the

opposite (see Coles 1995). Despite the

necessary cosmological allusions, neither

the gurine in itself nor the actions clustering

around it were of a ‘ritual’ or ‘religious’

nature. The contextual data and the formal

properties of the Hangaskangas elk propose

that the artefact was marginal to large-scale

social concerns. We suggest that the iconic

content was not the object’s main mode of

meaning, that is, the Hangaskangas elk was

not a characteristically expressive artefact,

whose ‘message’ was decoded through the

visual/intellectual act. Rather, the object

served the needs of the phenomenological

lived body in a speci c environmental/

cultural setting.

CONCLUSION

Our principal aim has been to challenge the

notion that prehistoric art primarily operates

in the domain of the symbolic. By presuming

that the encounters with art objects in

prehistory were characteristically visual/in-

tellectual acts of transferring messages that

the modern analyst is expected to decipher,

one probably misrepresents the meanings of

ancient art objects. We have argued that the

signi cance of the visual aspect of prehistoric

art may have been overly emphasized at the

expense of other modes of meaning.

In the study of rock art, the shift from a

purely visual and iconocentric interpretation

to wider geographic and non-visual issues has

been an important development (e.g. Chippin-

dale & Tac¸on 1998, Bradley 2000, Ouzman

2001, Goldhahn 2002, Nash & Chippindale

2002), and this swing would be welcome in

the study of prehistoric art in general. In

particular, Ouzman’s (2001) work on San

rock art emphasizes the importance of non-

visual aspects of rock art, indicating that

touching images and hammering them to

produce sounds were signi cant, if not very

obvious, activities. Iconocentric approaches

to prehistoric art may have more to say about

modern preconceptions than indigenous

meanings of art objects. While there is no

need to deny the communicative aspect of

prehistoric art, it is of paramount importance

to recognize that the expressive paradigm of

art is a modern construction, which only

partially illuminates the central question of

the meaning of prehistoric art.

A fuller understanding of prehistoric art

objects requires that the role of situated

practice is acknowledged, and this is what

the expressive paradigm of art fails to do.

Textual interpretations of art tend to assume

that culture is a static collection of values and

symbols, exaggerating the local consensus of

meanings (MacClancy 1997:3; also see Saler

2000:41). Moreover, there is little to say about

artefacts like the Hangaskangas elk from the

perspective of the expressive paradigm; one

may quite freely use them to illustrate any

‘grand narrative’. But our interpretation of the

Hangaskangas elk does not deny the impor-

tance of the collectives. The archaeological

record can, and should, be interpreted on

various scales (Meskell 1999:50).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We salute Anu Hartta, Mikko Hietala, and

Tab Surlaw for invaluable assistance in the

preparation of this article.

Mind, Materiality and Prehistoric Art

105

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

REFERENCES

Att eld, J. 2000. Wild Things: The Material

Culture of Everyday Life

. Berg, Oxford.

Autio, E. 1995. Horned anthropomorphic gurines

in Finnish rock-paintings: shamans or some-

thing else? Fennoscandia Archaeologica 12,

13–18.

Barasch, M. 1985. Theories of Art: From Plato to

Winckelmann

. New York University Press, New

York.

Barasch, M. 1997. The Language of Art: Studies in

Interpretation

. New York University Press,

New York.

Bloch, M. 1995. Questions not to ask of Malagasy

carvings. In Hodder, I. et al. (eds.), Interpreting

Archaeology: Finding Meaning in the Past

.

Routledge, London.

Bradley, R. 2000. An Archaeology of Natural

Places

. Routledge, London.

Bru¨ck, J. 1999. Ritual and rationality: some

problems of interpretation in European archae-

ology. Eur. J. Arch. 2(3), 313–344.

Carpelan, C. 1974. Hirven- ja karhunpa¨a¨esineita¨

Skandinaviasta Uralille. Suomen Museo 81, 29–

88.

Carpelan, C. 1977. A¨lg- och bjo¨rnhuvudfo¨remacl

fracn Europas nordiga delar. Finskt Museum 82,

5–67.

Carroll, N. 1999. Philosophy of Art: A Contem-

porary Introduction

. Routledge, London.

Chippindale, C. & Tac¸on, P. 1998. The Archae-

ology of Rock-Art

. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge.

Coles, J. 1995. Rock art as a picture show. In

Helskog, K. & Olsen, B. (eds.), Perceiving Rock

Art: Social and Political Perspectives

. The Alta

Conference on Rock Art. Inst. for sammen-

lignende kulturforskning , Oslo.

Conkey, M. 1987. New approaches in the search

for meaning: a review of research in ‘Palaeo-

lithic art’. J. Field Arch. 14(4), 413–430.

Crowley, J. 1989. The Aegean and the East: An

Investigation into the Transference of Artistic

Motifs between the Aegean, Egypt, and the Near

East in the Bronze Age

. Studies in Mediterra-

nean Archaeology and Literature, pocket-book

51. Paul Acstro¨m fo¨rlag, Jonsered.

Danto, A. 1997. After the End of Art: Contempor-

ary Art and the Pale of History

. Princeton

University Press, Princeton.

Descola, P. & Pa´lsson, G. 1996 (eds.). Nature and

Society: Anthropological Perspectives

. Rout-

ledge, London.

Edgren, T. 1984. Suomen kivikausi. In Laaksonen,

E. et al. (eds.), Suomen historia 1. Weilin

‡ Go¨o¨s, Espoo.

Errington, S. 1991. Real artefacts: a comment on

‘conceptual art’. In Bryson, N. et al. (eds.),

Visual Theory: Painting and Interpretation

.

Polity Press, Cambridge.

Gell, A. 1988. Technology and magic. Anthro-

pology Today 4

, 6–9.

Gell, A. 1992. The technology of enchantment and

the enchantment of technology. In Coote, J. &

Shelton, A. (eds.), Anthropology, Art and

Aesthetics

. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Gell, A. 1996. Vogel’s net: traps as artworks and

artworks as traps. J. Material Culture 1, 15–38.

Gell A. 1998. Art and Agency: An Anthropological

Theory

. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Goldhahn, J. 2002. Roaring rocks: An audio-visual

perspective on the hunter-gatherer engravings in

Northern Sweden and Scandinavia. Norw. Arch.

Rev. 35(1)

, 29–61.

Graves-Brown, P. 1995. Stone tools, dead sheep,

saws and urinals: a journey through art and skill.

In Scho eld, A. (ed.), Lithics in Context:

Suggestions for the Future Direction of Lithic

Studies

. Lithic Studies Society Occasional

Papers No. 5. Lithic Studies Society, London.

Gro¨nhagen, J. 1994. Ristiinan Astuvansalmi,

muinainen kulttipaikkako? Suomen Museo 101,

5–17.

Hall, J. 1983. A History of Ideas and Images in

Italian Art

. John Murray, London.

Halverson, J. 1987. Art for art’s sake in the

Paleolithic. Curr. Anthropol. 28, 63–71.

Hays, K. 1993. When a symbol is archaeologically

meaningful?: meaning, function, and prehistoric

visual arts. In Yoffee, N. & Sherratt, A. (eds.),

Archaeological Theory: Who Sets the Agenda

?

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Hesjedal, A. 1994. The hunter’s rock art in

Northern Norway: problems of chronology and

interpretation. Norw. Arch. Rev. 27(1), 1–14.

Higgs, E. & Jarman, M. 1975. Paleoeconomy.

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Huurre, M. 1998. Kivikauden Suomi. Otava,

Helsinki.

Ingold, T. 2000a. The Perception of the Environ-

ment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill

.

Routledge, London.

Ingold, T. 2000b. Totemism, animism and the

106 Vesa-Pekka Herva and Janne Ika¨heimo

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

depiction of animals. In Ingold, T. (ed.), The

Perception of the Environment: Essays in

Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill

. Routledge,

London.

Kivika¨s, P. 1995. Kalliomaalaukset: muinainen

kuva-arkisto

. Atena, Jyva¨skyla¨.

Lahelma, A. 2000. Landscapes of the Mind: A

Contextual Approach to Finnish Rock-Art.

Unpubl. MA thesis. Inst. for Cultural Research,

University of Helsinki.

Last, J. 1998. A design for life: interpreting the art

of C¸atalho¨yu¨k. J. Material Culture 3, 355–378.

Le´vi-Strauss, C. 1962. Totemism. Merlin Press,

London.

MacClancy, J. 1997. Anthropology, art and

contest. In MacClancy, J. (ed.), Contesting

Art: Art, Politics and Identity in the Modern

World

. Berg, Oxford.

Matiskainen, H. 1989. Studies on the Chronology,

Material Culture and Subsistence Economy of

the Finnish Mesolithic, 10 000–6000 b.p., Iskos

8

. Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys, Helsinki.

Meinander, C. 1964. Skifferknivar med djurhu-

vudskaft. Finskt Museum 71, 5–33.

Meskell, L. 1995. Goddesses, Gimbutas and New

Age archaeology. Antiquity 69, 74–86.

Meskell, L. 1999. Archaeologies of Social Life:

Sex, Class, Etc. in Ancient Egypt

. Blackwell,

Oxford.

Miettinen, T. 2000. Kymenlaakson kalliomaalauk-

set

. Kymenlaakson maakuntamuseo, Kotka.

Miller, D. 1987. Material Culture and Mass

Consumption

. Blackwell, Oxford.

Miller, D. & Slater, D. 2000. The Internet: an

Ethnographic Approach

. Berg, Oxford.

Nash, G. & Chippindale, C. 2002. European

Landscapes of Rock-Art

. Routledge, London.

Nordbladh, J. 1978. Images as messages in

society: prolegomena to the study of Scandina-

vian petroglyphs and semiotics. In Kristiansen,

K. & Paludan-Mu¨ller, C. (eds.), New Directions

in Scandinavian Archaeology. Studies in Scan-

dinavian Prehistory and Early History

, Volume

1. The National Museum of Denmark, Copen-

hagen.

Nu´n˜ez, M. 1995. Re ections on Finnish rock art

and ethnohistorical data. Fennoscandia Archae-

ologica 12

, 123–135.

Ouzman, S. 2001. Seeing is deceiving: rock art and

the non-visual. World Arch. 33, 237–256.

Potts, A. 1996. Sign. In Nelson, S. & Shiff, R.

(eds.), Critical Terms for Art History. Univer-

sity of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Preucel, R. & Bauer, A. 2001. Archaeological

pragmatics. Norw. Arch. Rev. 34(2), 85–96.

Preziosi, D. 1998. Art history: making visible

legible. In Preziosi, D. (ed.), The Art of Art

History: A Critical Anthology

. Oxford Univer-

sity Press, Oxford.

Renfrew, C. 1994. Hypocrite voyant, mon sembl-

able. Cambridge Arch. J. 4, 264–269.

Saler, B. 2000. Conceptualizing Religion: Imma-

nent Anthropologists, Trancendent Natives, and

Unbounded Categories

. Berghahn Books, New

York.

Salo, U. 1984. Suomi pronssikaudella. In Laakso-

nen, E. et al. (eds.), Suomen historia 1.

Weilin ‡ Go¨o¨s, Espoo.

Shiner, L. 2001. The Invention of Art: A Cultural

History

. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Siikala, A.-L. 1980. Mita¨ kalliomaalaukset kerto-

vat Suomen kampakeraamisen va¨esto¨n usko-

musmaailmasta? Suomen Antropologi 4/1980,

177–193.

Siiria¨inen, A. 1981. On the cultural ecology of the

Finnish Stone Age. Suomen Museo 87, 5–40.

Sognnes, K. 1994. Ritual landscapes: toward a

reinterpretation of Stone Age rock art in

Trøndelag, Norway. Norw. Arch. Rev. 27(1),

29–50.

Taavitsainen, J.-P. 1978. Ha¨llmaclningarna: en ny

synvinkel pac Finlands fo¨rhistoria. Antropologi i

Finland 4/1978

, 179–195.

Talaley, L. 1993. Deities, Dolls, and Devices:

Neolithic Figurines from Franchthi Cave,

Greece

. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

& Indianapolis.

Taylor, T. 1994. Excavating art: the archaeologist

as analyst and audience. Cambridge Arch. J. 4,

250–254.

Ucko, P. 1968. Anthropomorphic Figurines of

Predynastic Egypt and Neolithic Crete with

Comparative Material from the Prehistoric

Near East and Mainland Greece

. Royal Anthro-

pological Institute Occasional Papers 24.

Andrew Szmidla, London.

Whitley, J. 1991. Style and Society in Dark Age

Greece: The Changing Face of a Pre-Literate

Society 1100–700 BC

. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge.

Wiessner, P. 1989. Style and changing relations

between the individual and society. In Hodder,

I. (ed.), The Meanings of Things: Material

Mind, Materiality and Prehistoric Art

107

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

Culture and Symbolic Expression

. Harper-

Collins, London.

Wiessner, P. 1990. Is there a unity to style? In

Conkey, M. & Hastorf, C. (eds.), The Uses of

Style in Archaeology

. Cambridge University

Press, Cambridge.

108 Vesa-Pekka Herva and Janne Ika¨heimo

Downloaded By: [Optimised: University of Sheffield,University of Sheffield] At: 12:12 5 February 2011

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Notes on the 3 inch gun materiel and field artillery equipment 1917

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Art and culture - Art (tłumaczenie), Art and culture - Kultura i sztuka (569)

Owady żerujące na zwłokach jako alternatywne źródło ludzkiego materiału genetycznego AMSIK Art 2490

39 Raytrace Materials and Maps

Electronics 1 Materials and com Nieznany

Lista słówek - Art and culture, Art and culture - Kultura i sztuka (569)

!Program Guide Mind, Body and Spirit – Your Life in Balance!

Art and culture Art (143)

MKULTRA Materials and Methods

Eurocode 6 Part 2 1996 2006 Design of Masonry Structures Design Considerations, Selection of Mat

Paulo Coelho History and the Art of Riding a Bicycle

Wright Material and Memory Photography in the Western Solomon Islands

Academic Studies English Support Materials and Exercises for Grammar Part 1 Parts of Speech

Fritz Leiber The Mind Spider and Other Stories

Meta Physician on Call for Better Health Metaphysics and Medicine for Mind, Body and Spirit by Steve

Anatoly Karpov, Jean Fran Phelizon, Bachar Kouatly Chess and the Art of Negotiation Ancient Rules f

więcej podobnych podstron