DAVID RIDGWAY

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

In memory of Stuart Piggott

Summary.

Bronze cheese-graters have been found in three 9th-century

warriors’ graves at Lefkandi in Euboea. The presence of a similar item in a

socially elevated male (and military) context is attested in the Iliad (xi, 628–

643), when it is used in the preparation of a kykeon (mixture) in Nestor’s depas

(cup) that apparently revives a wounded hero. ‘Nestor’s cup, good to drink

from’ is mentioned in an inscription from a grave (c. 725–700) at Euboean

Pithekoussai on the Bay of Naples; and a number of bronze (occasionally

silver) graters occur in 7th-century Orientalizing princely graves along the

Tyrrhenian seaboard. Unlike that of the better-known 8th-century Euboean

‘pre-colonial’ skyphoi there, the distribution of 7th-century graters extends as

far north as the metal-bearing area of Tuscany. It is suggested that a particular

kind of ‘heroic’ drinking may have been introduced to the local Etruscan

‘princes’ by Euboeans negotiating for supplies of the Tuscan ores that are

known to have been used at Pithekoussai; the presence c.700–690 of a high-

ranking Etruscan xenos (guest) at nearby Cumae, recently postulated on

epigraphic grounds, may be significant in this respect.

The reports on recent excavations in the

Toumba cemetery at Lefkandi in Euboea

have provided summary details of three 9th-

century cremation burials accompanied by

weapons and by a simple device of bronze

that is reasonably identified as a cheese-

grater:

1

TOMB

79B

(niche):

S[ub]-P[roto-]

G[eometric] II (c.875–850); Popham and

Lemos 1995, 154 fig. 6 (the cremation of

‘a Euboean warrior-trader’

2

); Popham and

Lemos 1996, pls. 78, B2 and 146d. 16

6.5 cm.

PYRE 13: SPG II (c.875–850); Popham et

alii 1982, 229 no. 8, pl. 28 no. 8; Popham

and Lemos 1996, pl. 48 no. 8. Two large

non-joining fragments, each 6.5

5 cm.

PYRE 14: SPG IIIa (c.850–800); Popham

et alii 1989, 118 fig. 2 (‘a warrior who had

been cremated with his sword’); Popham

and Lemos 1996, pls. 87 no. 18 and 146c.

c.16

7 cm.

One early 9th-century association of a

grater with weapons could mean anything or

nothing, and two need be no more than a

coincidence. Now that there are three, how-

ever, it is legitimate to enquire if there is any

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY 16(3) 1997

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997, 108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JF, UK

and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA.

325

particular use, custom or tradition that re-

quired the contents of the 9th-century war-

riors’ graves listed above to include this

humble utensil. In the Classical and later

periods, literature and archaeology combine to

suggest that, very much as we should expect,

the proper place for a cheese-grater is the

kitchen:

3

Cooking utensils are enumerated by Ana-

xippus in The Harp-singer thus: ‘Bring a

soup ladle, a dozen skewers, a meat hook,

mortar, small cheese scraper [sic: turok-

nestin], skillet, three bowls, a skinning

knife, four cleavers. First bring, won’t you,

you abomination in the eyes of the gods,

the small kettle and the things from the

soda shop. Late again, are you? Bring also

the axe and the rack of frying-pans.’

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae iv, 169b–c

tr. C.B. Gulick (Loeb vol. 2, 1928, 267–69)

In earlier centuries, however, the presence

of graters in military and/or socially elevated

male contexts is by no means confined to SPG

Lefkandi. It is attested in Homer; and a

number of graters have long been known

along the Tyrrhenian seaboard of Italy, where

they are first encountered in the Orientalizing

‘princely’ and other rich tombs of the 7th

century. The following notes have been

compiled in the hope that these relatively

familiar instances may shed light not only on

the life-style of 9th-century Euboean warriors,

but also, and more particularly, on certain

wider issues that are of considerable current

interest. Throughout, I am assuming that the

function of the graters treated here corre-

sponds to that of the Homeric knestis (see

below) and of the later Greek turoknestis: and

that accordingly, when they occur in the

archaeological record, these intriguing arte-

facts denote the real (or conceivably sym-

bolic) activity of grating cheese.

THE CONTENTS OF NESTOR’S CUP

Cheese is grated on a bronze grater at a

crucial juncture in the grim and violent

narrative of Iliad xi. Amidst the general

Achaean rout, Nestor rescues the wounded

Machaon and takes him to his hut. They are

eventually joined there by Patroclus (who

will die before the day is out), and meanwhile

Nestor’s lovely companion Hecamede duti-

fully prepares what is clearly regarded by

those present as refreshment appropriate to

the circumstances:

She first moved up a table for them, a

beautiful polished table with feet of dark

blue enamel, and on it she placed a bronze

dish with an onion as accompaniment for

the drink, and fresh honey, and beside it

bread of sacred barley-meal. Next a most

beautiful cup, which the old man had

brought from home — it was studded with

rivets of gold, and there were four handles

to it: on each handle a pair of golden doves

was feeding, one on either side: and there

were two supports below. Another man

would strain to move it from the table

when it was full, but Nestor, the old man,

could lift it with ease. It was in this cup

that the woman, beautiful as the god-

desses, mixed them their drink out of

Pramnian wine, over which she grated

goat’s cheese on a bronze grater, and

sprinkled white barley: and when the toddy

was prepared, she told them to drink. Now

when both had drunk and quenched their

parching thirst, and were enjoying the

pleasure of their conversation . . .

Iliad xi, 628–643

tr. M. Hammond (Penguin Classics 1987,

209; emphasis added)

Nestor’s depas, as ‘the only cup accorded a

detailed description in Homer’ (Lorimer

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

326

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

1950, 328), has attracted a good deal of

attention for a variety of reasons that need

not concern us here. Its typology and precise

function — mixing bowl and drinking cup?

krater and depas?

4

— are less important to

our present purposes than what it contained

by the time Hecamede had finished with it.

Attempts to convey in English translation

some idea of the recipe she uses have been

too many and too varied to inspire much

confidence. The most recent translation that I

have consulted (above) calls the end product

‘toddy’; the most recent commentary cites

‘frumenty or furmity’ (a` la mode de Caster-

bridge), ‘potage’, and ‘stimulating porridge’

(Hainsworth 1993, 293); and it would

probably not be difficult to extend this list

of more or less appetizing Hyperborean

regional beverages. The actual word that

Homer uses is kykeon, which need mean no

more than ‘mixture’:

any form of mixture of grain (alphi) and

liquid (water, wine, milk, honey, oil),

often seasoned with herbs (pennyroyal,

thyme, mint, etc.). It belongs to an

intermediate stage between that of eating

the grains (or offering them to the gods)

whole, and the introduction of fine milling

and baking (Richardson 1974, 344).

The same word is used by a number of later

writers, and often denotes a mixture with

medicinal properties (references and com-

ments: Richardson 1974, 344–48); it is

interesting to see that the medical aspects of

the Iliad passage cited above were empha-

sised by Plato.

5

Most notably, perhaps

(although not necessarily relevant here),

kykeon is the word used to denote the sacred

potion imbibed by the initiates at Eleusis

(Delatte 1955). In this connection, there have

been suggestions that the barley-meal com-

ponent was fermented; or, if afflicted by

fungal growth, that it might acquire psy-

choactive and/or hallucinogenic properties —

a possibility that has indeed been extended to

the Homeric passage above (Tsavella-Evjen

1983, 188; so too Hijmans 1992, 31).

It has been remarked that, after their fast,

the initiates at Eleusis might have needed

simply to be soothed, refreshed and sustained

for what lay ahead, and that this effect could

have been achieved by modern peppermint

tea (Richardson 1974, 345). Machaon’s

circumstances, on the other hand, surely call

for something stronger. He is a hero (who is

also a healer himself and therefore capable of

appreciating his own condition); a terrible

battle is raging, and he has been wounded in

it. His injury, caused by a three-barbed arrow

in the shoulder, is probably not in itself life-

threatening, but it is bound to be extremely

painful — and when he has been assisted to

Nestor’s hut, Hecamede can probably guess

(even if he cannot) that he must also steel

himself for a lecture; in the event, it was

Nestor’s longest. Like any good hostess, she

saw instantly that this was not an occasion

merely for light refreshment (or an aperitivo,

as Blanck 1987, 113): and we are surely

meant to infer that the mixture she prepared

instead had the desired effect. It is not clear

whether that effect was literally halluci-

nogenic, narcotic or otherwise psychoactive:

we are simply told that it was thirst-

quenching, and we are surely justified in

assuming that it was also analgesic. It may be

relevant to note that Machaon’s wound is not

even washed until the beginning of Iliad xiv

(1–8), when Nestor goes back to the battle-

field to see what has been going on while he

has been lecturing.

More than anything else, in fact, the

mixture that Hecamede prepared for Ma-

chaon seems to have the characteristics of an

effective pain-killer; and it seems most likely

that in terms of liquid volume its principal

DAVID RIDGWAY

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

327

ingredient was Pramnian wine. ‘Pramnos’ is

not attested as a toponym, which is all the

stranger in view of the fact that its wine had a

certain reputation throughout antiquity. An

anthology of comments compiled c.200 AD

tells us that Pramnian wine is

neither sweet nor rich, but dry, hard, and

of extraordinary strength . . .

Pramnian wines, which contract the eye-

brows as well as the bowels . . .

[it is] called by some ‘medicated’ . . .

the vine which bears the Pramnian of

Icaros . . . is called by foreigner ‘sacred’,

but by the natives of Oenoe ‘Dionysias’ . . .

Didymus declares that Pramnian gets its

name from a vine called Pramnia; others

say that it is a special term for all dark

wine, while some assert that it may be

applied in general to all wine of good

keeping qualities, as if the word were

paramonion (‘enduring’); still others ex-

plain it as ‘assuaging the spirit’ (pray¨non-

ta), since drinkers of it are mild tempered.

Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae i, 30b–e

tr. C.B. Gulick (Loeb vol. 1, 1927, 133–35)

These and other ancient comments (Dalby

1996, 100f.; 254 note 51) leave us with the

impression of a drink that, although ulti-

mately derived from the grape (like brandy

and grappa), nevertheless has properties

quite unlike those of, say, the Lemnian that

the Achaean troops were able to purchase on

at least one occasion (Iliad vii, 472), or the

Thracian

vin ordinaire that was being

shipped in to them daily (Iliad ix, 72). The

taste was probably its worst feature: but this

could be mitigated by the addition of other

strongly flavoured elements. Grated goat’s

cheese clearly does not spring to the modern

mind for this purpose,

6

and neither for that

matter does ‘an onion as accompaniment’ (or

relish: Dalby 1996, 22–24): but both invari-

ably make their presence felt in one way or

another, and in ancient terms had the obvious

virtue of being at least as readily available

as, say, barley — cheese also keeps well, and

is easy to carry. Whether anyone, ancient or

modern, would find the taste of the resulting

mixture to be pleasant is a moot point: but if

this kykeon was ‘strong’ in the basic

alcoholic sense, one can imagine that the

effects might be perceived as on the whole

very pleasant. So much so, in fact, that some

might wish to indulge for purposes other

than the strictly medicinal. Nestor himself is

a case in point: he has not been wounded,

and he carries on drinking until the begin-

ning of Iliad xiv. But then, as Andrew

Sherratt has recently reminded us,

. . . the availability of psychoactive pro-

ducts is a constant temptation to ‘misuse’

— a term that implies less a medical

judgement than a social one, in the sense

of an unrestricted (and possibly habit-

forming) hedonism. Few cultures allow

this privilege to more than a fraction of

their members, whether this fraction is

defined by gender, status, wealth, or a

combination of all three (A. Sherratt 1995,

15).

We might recall, too, that on another

memorable Homeric occasion, precisely the

same mixture as that prepared in Nestor’s hut

was so welcome to some of Odysseus’

companions that Circe could use it as the

vehicle for the sinister pharmaka that enabled

her to change Eurylochos’ group into pigs

(Odyssey x, 229–243, esp. 234f). We are not

told that Circe used a grater: is this simply

the luck of the poetic draw, or would it have

been out of place for her to possess a utensil

associated in the audience’s mind with the

field of battle rather than the kitchen? In

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

328

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

either case, it is worth remembering that, as

Susan Sherratt has pointed out, it is compara-

tively rare in Homer for wine to be mixed

with other substances, psychoactive or other-

wise: and that although men drink the results,

the mixtures are invariably concocted by

foreign or ‘strange’ women — Hecamede is a

Trojan captive, Circe (Hijmans 1992) is the

daughter of Helios.

7

I agree that this might

imply a connection between such potions and

a non-Greek cultural ethos — indeed, I think

it almost certainly does; but the combination

of exotic females and unusual (doctored?)

drinks is also one that young seafarers and

soldiers have been warned against by their

fathers since the beginning of time, and

surely were at the outgoing and cosmopolitan

centre that was 9th-century Lefkandi.

At this point, it seems reasonable to ask,

and to attempt to answer, the ‘chicken or egg’

question: which came first? On the restricted

front treated here, does the presence of

bronze cheese-graters among the grave goods

of 9th-century Euboean warriors at Lefkandi

mean that life is copying Homer, or that

Homer is copying life? I am aware both that

similar questions have been discussed else-

where (e.g. Whitley 1991, 34–39; Hurwit

1993), and that in recent years the idea of a

special relationship between Euboea and the

Homeric epics has gained a good deal of

ground:

[i]f there was anywhere where eastern

mythological poetry might have run up

against Greek in the generations before

Homer, it was Euboea — just where . . .

the old Greek heroic tradition was entering

a marvellous new creative phase between

the late tenth and the mid eighth century

(M.L. West 1988, 170f.; cf Winter 1995,

261f.).

It would be hard to find an historical

audience that fits more closely what we

can infer from the poems than the affluent,

seafaring Euboians . . . Homer’s tale of

international warfare waged on a plain

would have special meaning to men who

fought the first historical war in Greece,

on the Lelantine Plain . . . The Odyssey’s

theme of longing for home after dangerous

adventure in the far West would also have

special relevance to men who actually

travelled to the far West . . . (Powell 1991,

231; and see Powell 1993).

. . . la rotta di Ulisse pare proprio disegnare

la mappa archeologica dei siti di ritrova-

menti euboici sulla rotta dell’occidente

(Braccesi 1993, 15).

The Euboeans who settled on Ischia (and

soon afterwards founded Cumae on the

mainland) were the carriers of a powerful

virus — the Ionian (and now panhellenic)

epic tradition (Wiseman 1995, 35).

And so on. There is undoubtedly a certain

charm in the thought of real-life warriors (or

warrior-traders) at Lefkandi packing graters

into their kit bags after hearing a recitation of

Iliad xi: but, as in the better known case of

the Lefkandi horse-burials (Popham 1993,

22), this degree of deliberate imitation of

Homeric practice is not really convincing. It

is, I believe, much more likely that the bards

who recited the Homeric poems at home and

abroad made it their business to capture and

keep their audiences’ attention by means of

references to the material circumstances and

traditions of their own time.

8

In other words,

the version of the Homeric poems that has

come down to us will contain allusions that

could have been formulated at any time in the

Bronze and Early Iron Ages, as in the case of

iron and iron tools (E.S. Sherratt 1994, 78–

80; and note too the appearance at Iliad xviii,

DAVID RIDGWAY

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

329

401 of a certain combination of bronze

personal ornaments that seems to have been

in use during the second half of the 8th

century at Pithekoussai: Ridgway 1994, 72).

On this reckoning, I submit that bronze

cheese-graters at Lefkandi make perfectly

good sense as part of a warrior’s personal

property. A grater could have been regarded

as essential both to the preparation of an

effective pain-killer and to the kind of serious

non-medicinal drinking that is not unknown

in military circles: if so, there would be two

reasons why mention of the key words in a

recitation would be likely to provoke an

appreciative audience reaction.

Athenaeus (above) locates the source of

Pramnian wine on the island of Icaros, mid-

way between Myconos and Samos; Pliny

(Nat. Hist. xiv, 6.54) associates it with

Smyrna. Either location would be well within

the geographical range covered by the

Euboean ‘warrior trader’ buried with a grater

in Tomb 79B in the Toumba cemetery at

Lefkandi, and by a good many of his

contemporaries (Popham 1994). This obser-

vation is not in itself affected by the

suggestion that the tomb in question might

in fact be the grave of an enterprising

easterner, Phoenician or Cypriot, whose

status in life at Lefkandi would have been

that of a ‘resident alien’ — perhaps (though I

think this highly unlikely) one of ‘the

progenitors of the later metics of the Greek

polis’ (Papadopoulos 1996, 159 with further

references). Did early Phoenicians and Cy-

priots grate cheese?

9

Whatever the answer to

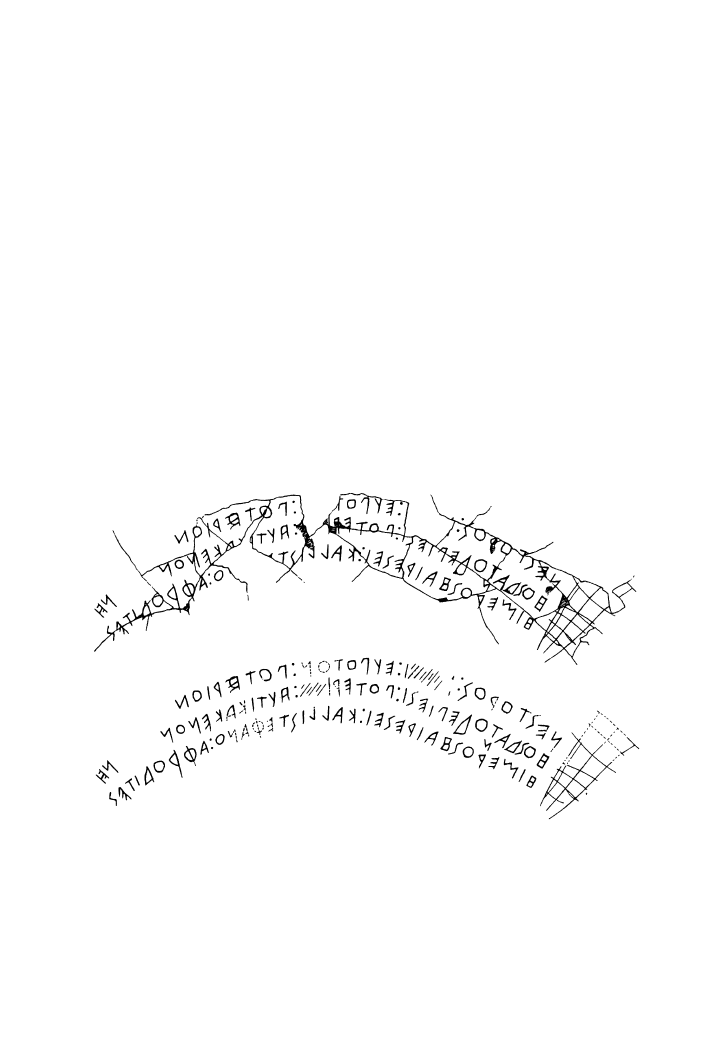

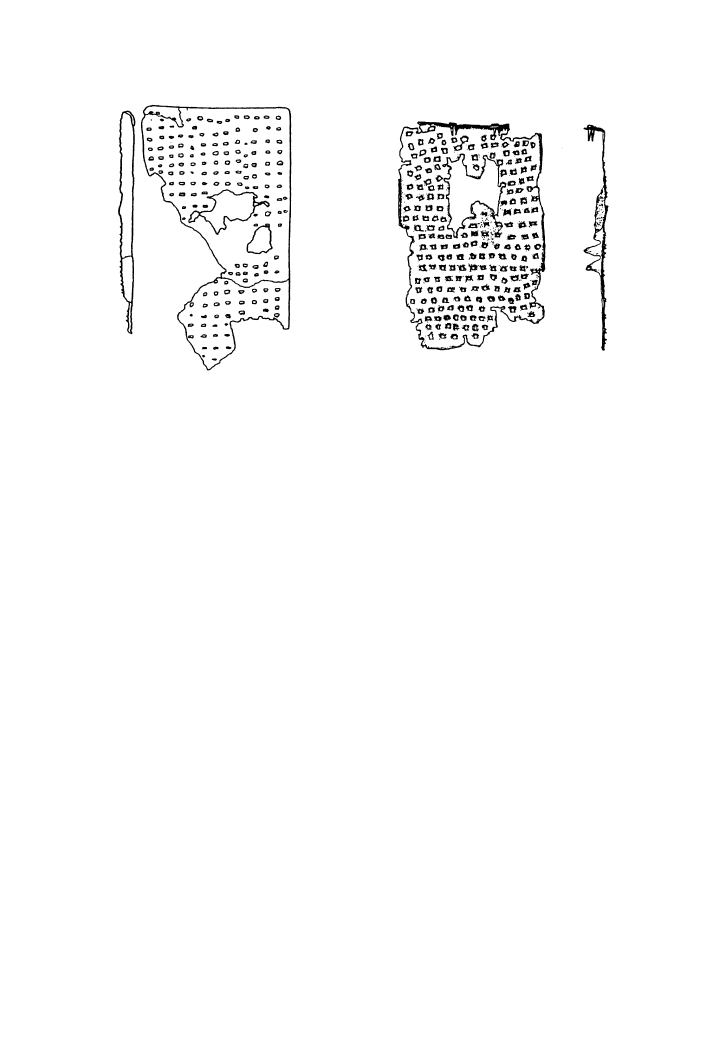

Figure 1

Surviving fragments (above) with integrations (below) of the retrograde metrical inscription from Pithekoussai grave

168 (Buchner and Ridgway 1993, pl. 73; c. 725–700 BC): ‘Nestor’s cup was good to drink from, but anyone who

drinks from this cup will soon be struck with desire for fair-crowned Aphrodite’.

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

330

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

this not entirely rhetorical question, it has

been acutely noted that the geographical

denomination of wines (such as Lemnian

and Thracian) could itself be a natural

consequence of increased portability (Dalby

1996, 95). How much Homeric kykeon was

consumed from the pendent semicircle sky-

phoi (drinking cups) associated with the

bronze graters in the other two SPG contexts

listed above? — and in the other Euboean

skyphoi like them that eventually found their

way to the West (d’Agostino 1990; more

recently Peserico 1995; von Hase 1995)?

Although we shall presumably never be

able to answer this question, it seems safe to

assume that at least some of the first Western

Greeks knew about Hecamede’s mixture.

Quite independently of the archaeological

considerations expounded here, the majority

of literary specialists seem to be in no doubt

that the famous metrical inscription (Figure

1) on the Rhodian Late Geometric kotyle

(drinking cup) from tomb 168 (c.725–700) at

Euboean Pithekoussai (Ischia) on the Bay of

Naples alludes to the Hecamede-Machaon

episode in Nestor’s hut.

10

In fact, the first

few words could hardly be more explicit:

Nestoros . . . eupoton poterion — ‘Nestor’s

cup, good to drink from.’ Or ‘that does you

good’? — or both? (Pithekoussan humour is

a serious business: Hansen 1976). And — as

luck would have it! — while this paper was

being written (Summer 1996), two bronze

graters were discovered in a 7th-century

domestic context during further excavation

of the Greek farmstead site at Punta Chiarito

on the southwest coast of Ischia, c.12 km as

the crow flies from the acropolis of Pithe-

koussai.

11

CAMPANIA, LATIUM, SOUTHERN ETRURIA AND

TUSCANY

Many graters have come to light in Italy

since a passage in Aristophanes prompted

compilation of the first list more than 60

years ago (Jacobsthal 1932). It is now known,

for example, that a particularly fine specimen

(1. 16 cm.; BM inv. GR 1975.8–4.20) was

acquired by Sir William Hamilton at Trebbia,

near Capua, from a tomb he caused to be

opened there in 1766. The handsome corredo

(Figure 2) of which it is part has survived in

the British Museum, and is well-supplied

with drinking equipment — notably a bowl,

wine-strainer and wine-ladle, all of bronze: it

also includes two iron swords, and is dated to

the decades 440–420 BC by an Attic red

figure bell-krater, attributed to the Lykaon

Painter and depicting four symposiasts (Jen-

kins and Sloan 1996, 141–43 no. 25a–i).

Other individual specimens from Italian sites

have attracted useful comments and further

lists of occurrences.

12

The chronological

range extends from Orientalizing to the 3rd

century; the geographical distribution even-

tually covers the Etrusco-Italic areas (Etruria

itself; Etruria padana; the Etruscan[ized]

centres in Campania; Picenum; Apulia) and

Sicily — where it was long ago remarked

that a handsome iron grater, 20

7 cm, from

a Middle Corinthian tomb at Syracuse was

‘the largest of the many held by the Museum’

(Orsi 1925, 186). A constant feature of these

graters is their uncompromisingly functional

appearance — ‘la parvenza di appartenere

ancora alla vita, quasi fosse pronto per l’uso,’

as a modern scholar has remarked (Zancani

Montuoro 1983, 5), in very much the same

words that D’Hancarville had used about the

Trebbia grater two centuries earlier (Jenkins

and Sloan 1996, 143). This engaging feature

inhibits the a priori attribution to specific

centres or centuries of unprovenanced speci-

mens like the following:

COPENHAGEN, National Museum (De-

partment of Near Eastern and Classical

DAVID RIDGWAY

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

331

Antiquities): inv. ABa 465; ‘bought in

Italy 1846;’ cited by Blinkenberg 1931,

215 as a parallel for an example from

Lindos; noted by Jacobsthal 1932, 5

(‘1864’; 18

8.2 cm’); otherwise unpub-

lished. 22

7.5 cm (Figure 3).

VATICAN CITY, Gregorian Etruscan

Museum: inv. 11175; Buranelli 1992, 77

cat. no. 43 (first publication; but see

Robinson 1941, 191 note 18; and now

Popham and Lemos 1996, pl. 158c). 18

9.8 cm.

All told, I estimate that a complete Italian

Corpus Radularum Antiquarum would now

run to several dozen entries; it will not be

attempted here, and neither will any kind of

typology. I limit myself to the earliest Italian

examples that I have been able to locate in the

literature, all of bronze (with two exceptions)

and all in graves of the 7th century (within

which a closer estimate has been accepted or

attempted as appropriate). The following list,

arranged from South to North (Figure 4) has

no pretence at completeness:

Campania

1

PONTECAGNANO,

tomb

928:

c.675–650; d’Agostino 1977, 15 no. R68,

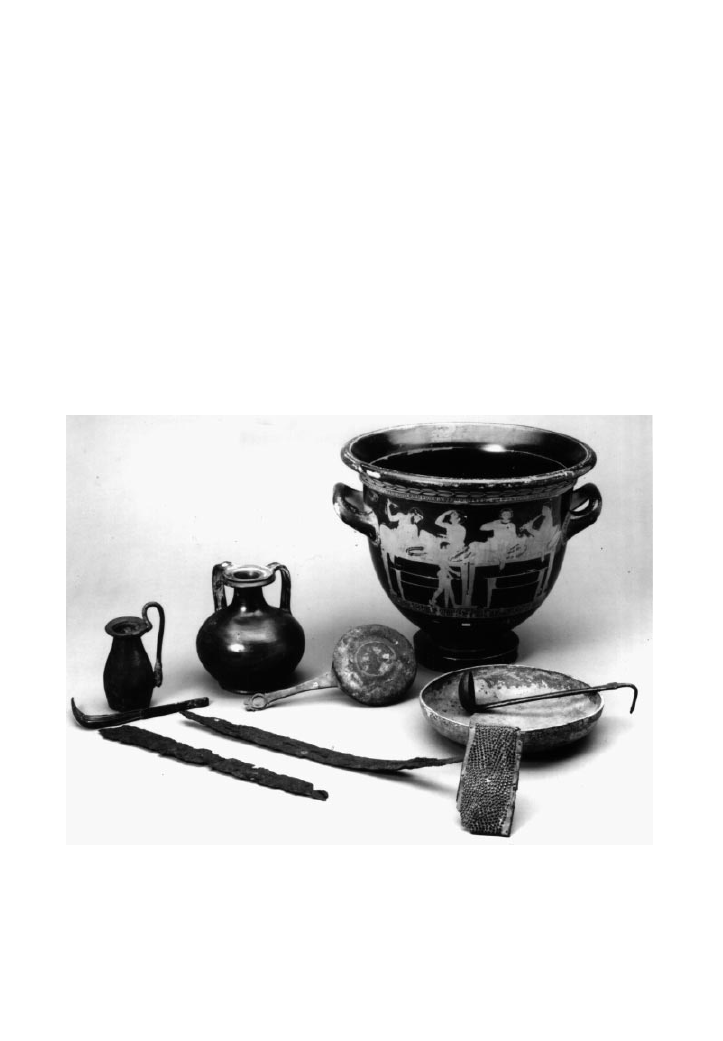

Figure 2

Grave-group with grater from Trebbia, Campania, acquired by Sir William Hamilton in 1766; now in London

(Jenkins and Sloan 1996, 142 no. 25a–i; c.440–420 BC). Photo courtesy of the Trustees of the British Museum.

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

332

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

53, 100 fig. 22, pl. 18e. Fragment;

dimensions not stated.

2

SAN MARZANO, tomb 164. Unpub-

lished; mentioned by Gastaldi 1979, 23.

3

CALES (Calvi), tomb 1: c.625/620;

Chiesa 1993, 35 no. 16, 68–69, pls. 4, 33.

Incomplete; 12.5

7 cm preserved (Fig-

ure 5, left).

Latium vetus

4

LAVINIUM (Pratica di Mare), tomb

under the ‘heroon of Aeneas:’ c.660; CLP

1976, 310 cat. no. 102/34 (P. Sommella),

pl. 79 no. 34. Incomplete; 8

5.4 cm

preserved.

5

CASTEL DI DECIMA, tomb 152:

c.690; CLP 1976, 273 cat. no. 84/31 (F.

Zevi). Fragment, not illustrated; 6.6

3.5 cm.

6

PRAENESTE,

Tomba

Bernardini:

c.675; Canciani and von Hase 1979, 42

no. 33, pl. 20 no. 3; Alimentazione 174 cat.

no. 68. Silver; 12.5

8.7 cm.

Southern Etruria

7

CAERE, Montetosto tumulus: unpub-

lished (not mentioned in Rizzo 1989);

listed by Cristofani 1980, 24 n. 48. Silver.

8

MAZZANO ROMANO, tomb 63:

Pasqui 1902, 595 fig. 1. 14.8

7.2 cm.

Tuscany

9

MARSILIANA D’ALBEGNA, Bandi-

tella cemetery, tomb 10: c.675–650 (Bag-

nasco Gianni 1996, 225); Minto 1921, 49,

pl. 37 no. 3. Trapezoidal; length 11 cm.

10–11

POGGIO

BUCO.

Tomb

B:

c.675–650; Matteucig 1951, 29 no. 66,

pl. 23 no. 3. Incomplete; dimensions not

stated.

Tomb V: c.650; Bartoloni 1972, 63 fig. 28

no. 21, 64 no. 21, pl. 31d. 11

7 cm

(Figure 5, right).

Figure 3

Grater ‘bought in Italy;’ now in Copenhagen. Photo

courtesy of the National Museum, Copenhagen.

DAVID RIDGWAY

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

333

12

SOVANA: unpublished; listed by

Cristofani 1980, 24 note 48.

13

VETULONIA, Tomba

del

Duce,

‘fourth group:’ c.650 (Bagnasco Gianni

1996, 246); Camporeale 1967, 96 no. 54,

pl. 17e. Fragment; 4.2

3.5 cm preserved.

14–17

POPULONIA. Tomba dei Flabel-

li:

13

Minto 1931, 301f., 341f., pl. 10 nos.

2, 6, 8. Three incomplete: 11.5

5.5 cm;

11

5.5 cm; 9 7 cm.

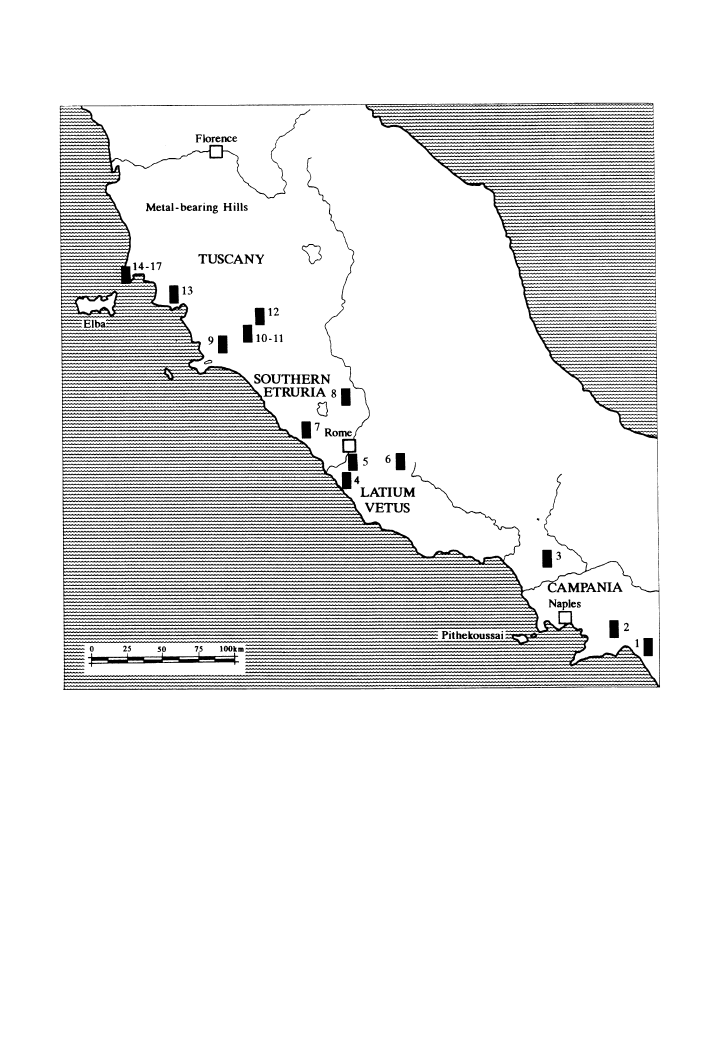

Figure 4

Distribution map of graters in 7th-century graves in CAMPANIA (1, Pontecagnano; 2, San Marzano; 3, Cales),

LATIUM VETUS (4, Lavinium; 5, Castel di Decima; 6, Praeneste), SOUTHERN ETRURIA (7, Caere; 8, Mazzano

Romano) and TUSCANY (9, Marsiliana d’Albegna; 10–11, Poggio Buco; 12, Sovana; 13, Vetulonia; 14–17, Populonia)

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

334

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

Tomb 30: De Agostino 1961, 88 no. 1.

12.5

6 cm.

Three features of this list call for comment.

Firstly, all the graters listed above come from

corredi that are ‘rich’, and in some cases

extremely so. Two of them, containing nos. 6

and 13, have indeed been cited on many

occasions as classic Orientalizing tombe

principesche (‘princely graves’) of the first

half of the 7th century; the context of no. 1 is

clearly in the same class, and so too are those

of nos. 7 and 14–16. Grater no. 2 comes from

an unpublished tomb that, we are told, is ‘una

delle sepolture ‘‘principesche’’ in localita`

‘‘Castello’’ di S. Marzano che ha restituito

il corredo maschile piu` ricco fra le tombe

dell’Orientalizzante’ (Gastaldi 1979, 23).

Cheese was thus grated in 7th-century

Tyrrhenian contexts at the highest level of

indigenous society, and this activity was

deemed to be worth recording in the graves

of men whose other grave goods regularly

included — for whatever reason (Frederiksen

1984, 71–74) — magnificent arms and

armour (e.g. nos. 6 and 14–16, and the

chariot-burial no. 9) and sophisticated uten-

sils of precious metal and imported pottery

for feasting and drinking. Secondly, in view

of the ‘Lefkandi connection,’ we might have

expected the distribution of bronze graters in

the 7th century to have rather more in

common than it does with that of the

Euboean ‘pre-colonial’ types of skyphos that

had begun to reach the West early in the 8th:

in the event, the latter are relatively plentiful

in Campania and Southern Etruria (e.g. at

Villanovan Veii: Ridgway 1988, whence

Figure 6), and conspicuous by their complete

absence from the area immediately to the

north, corresponding to modern Tuscany

(maps: Peserico 1995, 431 Abb. 9; 435

Abb. 13) — which provides just over half

(nos. 9–17) of the 17 graters collected here.

14

Thirdly, and without exception, the thirteen

centres involved were, and remained, ‘native’

rather than ‘Hellenized’.

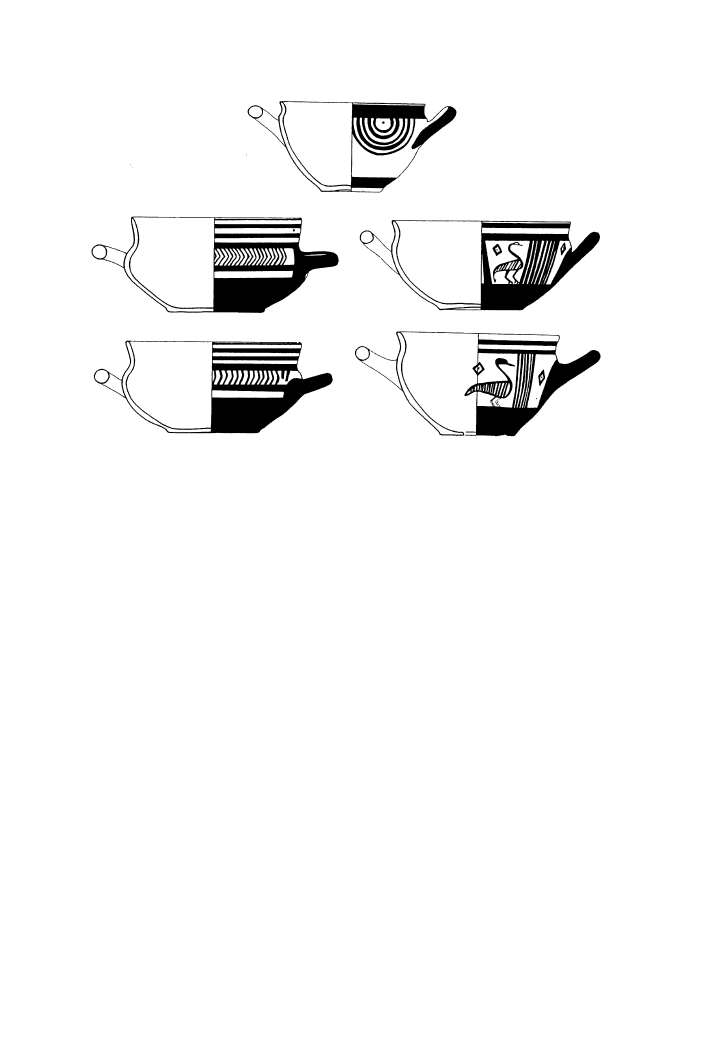

The Orientalizing centres listed above

Figure 5

Left: bronze grater from tomb 1, Cales, Campania; Fig. 4, 3 (Chiesa 1993, pl. 4 no. 16; c.625/620 BC). Right: bronze

grater from tomb V, Poggio Buco, Tuscany; Fig. 4, 11 (Bartoloni 1972, 63 fig. 28 no. 21; c.650 BC).

DAVID RIDGWAY

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

335

constitute a representative cross-section of

precisely the chronological, cultural and

social ambiente that, following the rapid

decline of Pithekoussai at the end of the 8th

century, was crucially affected by the role of

‘Euboean’ Campania (particularly Cumae) in

the transmission of new wares — and

sometimes their makers — to the emerging

indigenous e´lites of Latium and Etruria (e.g.

Rizzo 1989, 154, 161; Ridgway 1992, 140–

44). With the wares came the Greek alphabet,

and hence Etruscan literacy: an Etruscan

name is attested epigraphically, in Greek, at

Pithekoussai itself by c.700, and it has been

authoritatively argued that the well-known

Tataie and the notoriously enigmatic hisa-

menetinnuna (c.700–690) inscriptions at Cu-

mae represent two more early Etruscans

there, of which the latter — Hisa Tinnuna

— was, pace Frederiksen 1984, 119 and

Cassio 1993, using the Euboean version of

the Greek alphabet to write, or to have

something written, in his own language

(Colonna 1995). Five of the ten centres north

of Campania in the above list have yielded a

total of 24 Etruscan inscriptions that are

earlier than c.650; and three of them indeed

have graters in direct association with such

inscriptions.

15

As in contemporary Greece

(Powell 1991, 123–58), the majority of these

pieces of early writing are ‘short;’ a few are

longer, but need not detain us here; and one,

from the sumptuously appointed ‘Circolo

degli Avori’ at Marsiliana d’Albegna, vir-

tually contemporary with the context of

grater no. 9, is a well-known Etruscan model

alphabet inscribed round the edge of a

miniature ivory writing tablet. This remark-

able artefact was found with other writing

implements (styluses and erasers), and the

Figure 6

Euboean ‘pre-colonial’ skyphoi (drinking cups) from the Quattro Fontanili Villanovan cemetery at Veii, Southern

Etruria (Ridgway 1988, 491 fig. 1)

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

336

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

alphabet it bears has long been regarded as a

later version of a Cumaean alphabet related

to that employed in the ‘Nestor cup’ inscrip-

tion from Pithekoussai.

16

As I have already hinted, it is not at all

easy, at first sight, to relate the geographical

distribution of the grater list above either to

the ‘pre-colonial’ phenomenon in general or

to the establishment, by 750 at the very latest,

of the first Western Greek base on the island

of Ischia — although the associations of the

San Marzano grater, no. 2 above, are said to

include a cup of Protocorinthian type that

‘per le caratteristiche dell’argilla potrebbe

essere pitecusana’ (d’Agostino 1979, 64).

Should we attribute the material diffusion of

graters on the Italian mainland to the

activities of craftsmen (many of Euboean

descent) from a now greatly diminished

Pithekoussai, eager to exploit the new

markets brought into being by the social

aspirations of the newly-rich indigenous

e´lites in Latium and Etruria? Maybe: these

highly skilled men were, after all, responsible

to a significant degree for the outward

appearance of much that we call Etruscan

Orientalizing. But it is hard to feel wholly

confident that it was acceptable for a foreign

craftsman to introduce a ‘prince’ to a new

kind of drink and the frankly improbable

equipment necessary for its preparation.

Accordingly, I suggest that the 7th-century

distribution of Greek-style cheese-graters

along the Tyrrhenian seaboard is most likely

to have been achieved on the basis of

previous experience of their purpose and of

their associations. Graters nos. 9–17 come

from centres in and around the mineral rich

zone of Tuscany that is traditionally sup-

posed to have attracted the Greeks to the

West in the first place (e.g. Dunbabin 1948,

7f.): and Populonia (nos. 14–17), the only

Etruscan ‘coastal’ centre that is actually on

the coast, is its principal port. We have

already seen that there are no ‘pre-colonial’

Euboean skyphoi in this area; nor, it must be

admitted, is there any conventional (i.e.

ceramic) evidence for contact between Tus-

cany and Euboean Pithekoussai in the second

half of the 8th century — a period to which,

as it happens, hardly any corredi at Populo-

nia can safely be attributed (Romualdi 1994,

171). But the finds from the Pithekoussan

‘suburban industrial complex’ in the Mazzola

area of Lacco Ameno d’Ischia (Ridgway

1992, 91–96) confirm that iron was worked at

the first Western Greek base from the mid-

8th century onwards: the successive floor

levels of this intriguing site have yielded

many pieces of bloom and iron slag. Tuscany

is the nearest source of iron ore (of which

these are the waste products); and analysis of

a regrettably undatable piece of actual iron

mineral from another of the component sites

of Pithekoussai has demonstrated unequivo-

cally that it was mined on Elba (opposite

Populonia: Buchner 1969, 97–98). It might

be that the nine graters from Tuscany listed

above were the first ones to find a place in

corredi: the drinking custom they represent

could have been imported to the local

‘princes’ towards the end of the 8th century.

A suitable scenario might easily involve

Euboean negotiators seeking to ensure a

steady supply of iron ore from the hills of

Tuscany to the Bay of Naples — very much

as their Roman successors did (see Diodorus

Siculus v, 13 on the merchants who com-

muted between Aithalia [Elba] and Dicearch-

ia [Puteoli=modern Pozzuoli]). Is there,

perhaps, a role here for the newly-identified

Hisa Tinnuna (above) and others like him?

He was an Etruscan who used his own

formula (mene=make [gift]) on his contribu-

tion to a corredo at Cumae c.700–690. His

use, especially in this solemn context, of his

own language could mean that he was not a

permanent

and

fully-integrated

resident,

DAVID RIDGWAY

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

337

while the fact that he has not only a personal

name (Hisa) but also a family name (Tinnu-

na) — this is the oldest attested example in

Etruscan of the two-name formula — sug-

gests that he was recognized at Euboean

Cumae as a person of rank among his own

people. In Greek terms, he was certainly not

a mere metic: he seems rather to be an

honoured guest (xenos: Colonna 1995, 340.

Cf Frederiksen 1984, 119: ‘an Etruscan

presence in Cumae so early would be of

some importance’).

CONCLUSION

Bronze cheese-graters were used and

seemingly highly prized in 9th-century Lef-

kandi. Two centuries later, the same is true of

the no less affluent and well connected

societies of Early Orientalizing Campania,

Latium vetus, Southern Etruria and Tuscany.

There is nothing very surprising, or new,

about this situation. It has long been apparent

that some aspects of the archaeological

record of the Protogeometric heroon at

Lefkandi, including the geographical range

of contacts indicated by its more exotic

contents, recall the Italian ‘princely tombs’

discussed in the previous section. Have we,

then, arrived at the ultimate source of what

some would still call the ‘Hellenization of the

barbarians’? Perhaps: whatever its implica-

tion for the date of the Iliad in something like

its present form (Seaford 1994, 145), knowl-

edge, doubtless limited in scope and effect, of

Nestor’s Cup (and of the pleasant effects of

drinking from it) had reached the Bay of

Naples well before the end of the 8th century.

On a more mundane level, however, it

seems that the 9th-century cheese-graters

from Lefkandi have made it possible to

propose part of the answer — not necessarily

a large part, but more than we have had

before — to a question that is not asked as

often as it should be (but see below): what

were the first Western Greeks able to offer

the early Etruscans (who were not barbar-

ians) in exchange for access to the mineral

resources of Tuscany? My answer, ‘a drink,’

is hardly a novelty. Aegean kraters and

drinking vessels in ‘princely’ Cypriot tombs

are well known (Attic Middle Geometric at

Salamis,

Euboean

Late

Geometric

at

Amathus: Coldstream 1983; cf Luke 1994,

25); and the Cesnola krater from Kourion,

created c.750, has long been recognized as a

‘compendium’ for the Euboean potters at

Pithekoussai (with interesting consequences

for their colleagues in Etruria; see most

recently Coldstream 1994; and in general

Gisler 1995). As Murray (1994, 54) has

observed of the far-flung distribution of

Euboean skyphoi with pendent semicircles

and other motifs: ‘the function of the pottery

attests the diffusion of a social custom.’ I

have tried to show that the same has a good

chance of being true of cheese-graters in

Etruscan Orientalizing male tombs of the

highest social level — just as it is of the

better known and more obviously prestigious

metal and other vessels with which they are

associated there. We should not forget that

J.N. Coldstream, in reply to a question from

Paul Courbin (‘The kraters were gifts ex-

changed for what?’), proposed ‘possibly

access to metalliferous areas. This might

explain . . . the more surprising exports to the

far west . . .’ (Coldstream 1983, 207); or that

the only Euboean skyphos directly associated

with Western metallurgical activities is a fine

example of the type with pendent concentric

semicircles (similar to Figure 6, top) that

currently ‘has some sort of claim to be

regarded as the oldest known ‘‘pre-colonial’’

Greek vase in the West . . .’ (Sant’Imbenia,

Sardinia: Ridgway 1995, 80; 81 fig. 5).

Finally, it is not clear to me whether the

Etruscans could produce a vintage with the

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

338

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

special characteristics of Homeric Pram-

nian:

17

but I am not sure that they would

have wanted to. In the social circumstances

that I envisage, the practical relevance of the

analgesic properties appropriate to the battle-

field will long ago (perhaps at Pithekoussai?)

have been overtaken by the significance of

heroic antecedents and pleasurable effects (cf

A. Sherratt 1995, 15, quoted above): for we

are approaching the world of the Etruscan

banquet, in which more than drinking is

involved (Rathje 1990 and 1994; Small

1994). Before we take our (reclining) places,

there is no need for us to cite more recent

historical uses of ‘firewater’ in the exploita-

tion of indigenous populations and their

natural resources by technologically (though

not always culturally) superior incomers. We

might with advantage think rather of the later

European Iron Age milieu of the Vix krater

(Wells 1980), and reflect that the specialized

equipment required for the preparation and

consumption of rare, precious and intoxicat-

ing liquids has a most appropriate role to play

when the universal obligations of gift-ex-

change come into force between different

cultures.

Acknowledgements

Nobody but myself should be blamed for any

mistakes of fact, judgement and taste in this paper.

That said, I gratefully acknowledge that I would not

have written it if my Edinburgh colleague Irene Lemos

had not drawn my attention to the Lefkandi graters and

wanted to know more about their Italian cousins. She,

Nicolas Coldstream, Annette Rathje, Francesca R. Serra

Ridgway, Gillian Shepherd and Andrew and Susan

Sherratt have most generously answered my appeals for

advice and information, and I thank them for saving me

from error and for encouraging me to proceed — as did

Giovanna Bagnasco Gianni and Alfonso Mele, of whom

the latter responded from the floor more kindly than I

deserved to the tentative notes on Euboean and Etruscan

cheese-grating that I incorporated in a paper to the

‘Orientale-Be´rard-Edinburgh’ Euboean conference in

Naples (November 1996). It is a pleasure to recall that

this paper was drafted in successive visits to Annette

Rathje’s incomparable Institute in Copenhagen, where

the good offices of Bodil Bundgaard Rasmussen

(National Museum) ensured that I was both aware of

and able to illustrate the grater shown here as Fig. 3.

Nearer home, Judith Swaddling (British Museum)

performed the same service in respect of the fine

corredo in her care that appears as Fig. 2; Gordon

Thomas (Department of Archaeology, University of

Edinburgh) drew the map, Fig. 4: my best thanks to

them all.

I dedicate these pages to the memory of Stuart

Piggott (1910–1996), Abercromby Professor Emeritus

of Prehistoric Archaeology in the University of

Edinburgh. I do so in deep and lasting gratitude for

his friendship, and for the unswerving support and trust

that he accorded my endeavours at Pithekoussai from

the day I joined his Department in 1968. In the crucial

years for archaeology between then and his retirement

in 1977, I count myself fortunate indeed to have had a

Head of Department who never tried to convince me

that the first Western Greeks’ first Western base was

‘inhabited not by human beings — stinking likeable

witless intelligent incalculable real awful people — but

by the pale phantoms of modern theory, who do not

live, but just cower in ecological niches, get caught in

catchment areas, and are entangled in redistributive

systems’ (Antiquity 59, 1985, 146).

University of Edinburgh

Department of Classics

David Hume Tower

George Square

Edinburgh EH8 9JX

NOTES

1

The chronological attributions given in the list that

follows are those of Popham and Lemos 1996; see p. vii

for the new subdivision of SPG III; and ch. 12, Tables 1

and 2, for the contents and dates of the individual tombs

and pyres. I am grateful to Dr Lemos for her advice on

these matters, for providing the dimensions of the

Lefkandi graters, and for confirming that the three

graters assigned on Table 1 to Tomb 79A are the result

of a misprint.

2

It has been suggested that ‘this well-appointed tomb

DAVID RIDGWAY

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

339

could as easily be the grave of an easterner buried in

Greek lands:’ Papadopoulos 1996, 159. I am happy to

leave discussion of this apparently delicate matter to

others; see meanwhile Winter 1995.

3

Aristophanes, Wasps (presented in 422 BC) 938,

963; Birds (414 BC) 1579; Lysistrata (411 BC) 231, on

which see Jacobsthal 1932. Sparkes 1962, 132, 136 no.

56 is a homely Boeotian terracotta model of the early

5th century; Robinson 1941, 191–194 with pls. 48, 49

illustrates a number of fine specimens from Olynthus

s.v. ‘Household Furnishings’, dating ‘mostly from the

first half of the 4th century;’ Daremberg-Saglio IV, 2

s.v. radula is still informative. Etruscan kitchens and

their equipment: Blanck 1987 (graters: 113); Barbieri

1987; Buranelli 1992, 65–77.

An iron (sic) grater is reported from a rare pre-

Classical domestic context (but see note 11 below:

Pithekoussai): the latest level in a house at Malthi in

Messenia. Waldbaum 1978, 31 assigns it to the 11th

century (Late Submycenaean — Early Protogeometric);

Susan Sherratt, to whom I am indebted for my

knowledge of this piece, suggests that a date in the

‘10th century at the earliest’ is more probable.

4

‘Whereas the drinking cup of a prince is known as

aleison, depas or kupella, that of a swineherd is called

skyphos, and instead of the krater used by princes to

mix wine, the swineherd has a kissubion, a bowl of ivy-

wood:’ van Wees 1995, 150 with note 5 — where it is

observed that at Odyssey ix, 346 the Cyclops drinks

straight from a kissubion ‘(which is not to say it is

meant to be a drinking cup).’ On the wider significance

of krater-use: Luke 1994.

5

At Ion 538c, Socrates asks Ion whether a doctor or a

rhapsode is the best person to decide whether Homer’s

description of the Hecamede-Machaon episode is

reasonable or not; and Ion (a rhapsode) replies ‘a

doctor.’ I am grateful to my Edinburgh colleague Keith

Rutter for directing me to this passage.

6

‘Pilbrow was chuckling to himself.

‘‘Much better than the poor old Achaeans —’’ I

distinguished among the chuckles. We asked what it

was all about, and Pilbrow became lucid:

‘‘I was reading the Iliad — Book XI — again in bed

— Pramnian wine sprinkled with grated goat’s cheese

— Oh, can anyone imagine how horrible that must have

been?’’’ (C.P. Snow, The Masters [1951], chapter xii:

emphasis in original).

7

I am extremely grateful to Dr Sherratt for allowing

me to see the text of the unpublished lecture in which

she made this interesting point: ‘Pots and potions:

cultures of consumption in the Mediterranean Bronze

Age,’ read at Rewley House, Oxford in March 1995.

8

This statement represents a cautious attempt to build

on what seems to be the consensus that is emerging

from the extensive recent discussion of the point at

issue: ‘Only those elements of the tradition which, for

technical or contextual reasons, are most resistant to

restructuring preserve remnants of previous creation.

These act as fossilized traces of the successive contexts

which formed the epics as we know them, and which

can themselves be read in the archaeological record’

(E.S. Sherratt 1990, 821); ‘[The oral] tradition was not

static or merely custodial, but underwent episodes of

active generation, incorporating features of each period

while at the same time retaining elements from the

Bronze Age. Though the poems as we have them may

be the product of a particular poet in a particular time,

they owe their material to the entire period in which

they were under formation’ (Antonaccio 1995, 6); ‘Our

conclusion must be that the setting of the Homeric epics

has intimate links with the contemporary world of the

poet. On the other hand, there are a number of

components in the epics which originate in earlier

periods, such as traces of the Mycenaean dialect present

in Homeric formulas or the mentioning of Mycenaean

artefacts (such as Meriones’ boar’s tusk plated helmet

or Nestor’s dove cup)’ (Crielaard 1995, 274; emphasis

added).

9

Graters are not to be confused with strainers, like the

remarkable devices in Tomb 49 at Palaepaphos-Skales

(Karageorghis 1983, fig. 1xxxviii, nos. 9 and 197),

which could conceivably be used in the preparation or

serving (pouring) of the ‘deadly pottage’ healed by

Elisha at II Kings 4.38–41.

‘Asia Minor’ (‘6th-5th centuries BC’) is said to be

the provenance of a bronze grater incorporating a goat

in the Norbert Schimmel collection (Muscarella 1974,

no. 22 [H. Hoffmann]; ht. 7.7 cm.); it is cast in one piece

with a solid rectangular base, under which a separate

grating sheet is attached by rivets and folded edges. I

suppose that this would be rubbed on the cheese, using

the goat as a handle, rather than the reverse; cf

Jacobsthal 1932, 3 Abb. 2 (Camiros; 5th century) and

Beil 2 no. 2 (lion; Boston 10.163).

10

Buchner and Ridgway 1993, 212–223 with pls. 67–

75 and cxxvi–cxxx; and see 751–759 (O. Vox) for

bibliography of the 165 relevant items published 1955–

1991. On the Homeric connections see most recently

Powell 1991, 163–67 (‘Europe’s first literary allusion’);

S. West 1994, 9; Cassio 1994, 55; Murray 1994, 50 (in a

treatment of the inscription as offering ‘the earliest

evidence for a distinctively sympotic life-style:’ 51).

The vase that bears this famous inscription was

produced in the first phase of the Rhodian Late

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

340

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

Geometric Bird-kotyle workshop defined by J.N. Cold-

stream (1968, 277), and is thus a direct predecessor of

the Rhodian Subgeometric bird bowls referred to in note

14 below; at Pithekoussai, it is associated with no fewer

than four kraters (and one wonders how much kykeon

was mixed in them).

11

I am most grateful to Giorgio Buchner for this

information, and to Costanza Gialanella for showing me

the Pithekoussai graters during a memorable visit to the

Naples

Superintendency’s

Pozzuoli

storerooms

in

November 1996. See Ridgway 1995, 83 for a brief

account of previous work at Punta Chiarito; to the

references there cited add now Gialanella 1996.

12

Bailo Modesti 1980, 16–17; Cristofani 1980, 24

note 48 — the main source for the Tyrrhenian list that

appears below; Zancani Montuoro 1983, 5–8 with notes

7–8 — a characteristically incisive discussion of the

Homeric connection; Bellelli 1993, 90–91 (Nocera; one

of the graters is included in the impressive display of

5th-century aristocratic banqueting equipment illu-

strated by De Caro 1994, 45).

13

It must be admitted that the archaeological context

of these three graters, nos. 9–11 in the 7th-century

section of Cristofani’s list (note 12 above), is less than

satisfactory: the grave-goods associated with the four

depositions in the Tomba dei Flabelli, a chamber tomb,

are somewhat confused. Minto (1931, 363) rightly noted

the copious (‘la maggior parte’) similarities with the

grave-goods from the Regolini Galassi tomb at Caere

(c.675–650: Bagnasco Gianni 1996, 79, 347). Although

the full range seems to extend to c.575–550, there seems

to be rather more than a sporting chance that the three

graters nos. 14–16 belong to one of the pre-600 burials

— like e.g. the bronze shield of Strøm’s Orientalizing

Group B1, two Protocorinthian ovoid aryballoi and

many other items (Strøm 1971, 195). See also note 14

below.

14

Marina Martelli has noted a precisely similar

distinction between the distribution on the Italian

mainland of Rhodian Kreis- und Wellenbandstil ary-

balloi and the slightly later Subgeometric bird bowls.

Only the latter reach the more northerly area of Etruria,

where their distribution is mainly confined to Vetulonia

and Populonia. It includes one example each in the

contexts of nos. 13 and 14–16: Martelli Cristofani 1978,

154, 156–57 nos. 15 and 19 with pl. 76 figs. 2, 3 and 7,

8; both are of ‘Group II,’ c.675–640, in the classifica-

tion of Coldstream 1968, 299–301.

15

Direct associations: Praeneste, Tomba Bernardini

(no. 6; Bagnasco Gianni 1996, 303–304 no. 294; on a

silver cup; may be early Latin); Marsiliana d’Albegna,

Banditella 10 (no. 9; Bagnasco Gianni 1996, 225 no.

219; on a bronze tripod-bowl); Vetulonia, Tomba del

Duce, group 4 (no. 13; Bagnasco Gianni 1996, 246–248

no. 235: [1] on a relief-decorated kyathos of buccheroid

impasto; [2] on a fragmentary open vessel of silver). For

other Etruscan inscriptions in the c.700–650 range from

centres in the grater list see Bagnasco Gianni 1996,

346–347: Caere (ten more contexts; eighteen more

inscriptions); Poggio Buco (one more context; one more

inscription); Marsiliana d’Albegna (one more context;

three more inscriptions, including the model alphabet to

which reference is made in note 16 below).

16

The main issues raised by the Marsiliana model

alphabet can be pursued via Bagnasco Gianni 1996, 227

no. 221; see too G. and L. Bonfante 1983, 23 with 36

note 108 (styluses), 45 with 97 note 10, 106–107 with

figs. 10a, 11; and Powell 1991, 155–56 no. 55; 183 (‘too

small in size to be a real writing tablet, must be a model,

an amulet that carried the owner’s literacy into the other

world’).

17

The modern Chianti region is in the heart of

ancient Etruria; and Luni, on the border between

Tuscany and Liguria, was famous in antiquity for both

wine and cheese (Pliny, Nat. Hist. xi, 97.241; xiv, 8.68;

Martial xiii, 30).

ABBREVIATIONS

AIONArchStAnt: Annali, Istituto Universitario Orien-

tale, Napoli: sezione di Archeologia e Storia Antica.

Alimentazione: L’alimentazione nel mondo antico: Gli

Etruschi (Rome 1987).

REFERENCES

ANTONACCIO, C.M.

1995: Lefkandi and Homer. In

Andersen, Ø. and Dickie, M. (eds.), Homer’s world:

fiction, tradition, reality (Bergen) 5–27.

DAVID RIDGWAY

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

341

BAGNASCO GIANNI, G.

1996: Oggetti iscritti di epoca

orientalizzante in Etruria (Florence).

BAILO MODESTI, G.

1980: Cairano nell’eta` arcaica:

l’abitato e la necropoli (Naples).

BARBIERI, G.

1987: La Tomba Golini I e la cista di

Bruxelles: due rappresentazioni di ‘cucina.’ In Alimen-

tazione, 119–122.

BARTOLONI, G.

1972: Le tombe da Poggio Buco nel

Museo Archeologico di Firenze (Florence).

BELLELLI, V.

1993: Tombe con bronzi etruschi da

Nocera. In Miscellanea Etrusco-Italica 1 = Quaderni

di Archeologia Etrusco-Italica 22 (Rome) 65–104.

BLANCK, H.

1987: Utensili della cucina etrusca. In

Alimentazione, 107–117.

BLINKENBERG, C.

1931: Lindos 1 (Berlin).

BONFANTE, G.

and

L.

1983: The Etruscan language: an

introduction (Manchester).

BRACCESI, L.

1993: Gli Eubei e la geografia dell’Odissea.

Hesperı`a 3, 11–23.

BUCHNER, G.

1969: Mostra degli scavi di Pithecusa.

Dialoghi di Archeologia 3, 85–101.

BUCHNER, G.

and

RIDGWAY, D.

1993: Pithekoussai 1 =

Monumenti Antichi n.s. IV (Rome).

BURANELLI, F.

1992: The Etruscans: legacy of a lost

civilization from the Vatican Museums (exhibition

catalogue: Memphis, Tenn).

CAMPOREALE, G.

1967: La Tomba del Duce (Florence).

CANCIANI, F.

and

VON HASE, F.-W.

1979: La Tomba

Bernardini di Palestrina (Rome).

CASSIO, A.C.

1993: La piu` antica iscrizione greca di

Cuma e tin(n)umai in Omero. Die Sprache 35 [1991–

93] 187–207.

CASSIO, A.C.

1994: Keinos, kallistephanos, e la circola-

zione dell’epica in area euboica. AIONArchStAnt n.s. 1,

55–67.

CHIESA, F.

1993: Aspetti dell’Orientalizzante recente in

Campania: la tomba 1 di Cales (Milan).

CLP

1976: Civilta` del Lazio primitivo (exhibition

catalogue: Rome).

COLDSTREAM,

J.N.

1968: Greek Geometric pottery

(London).

COLDSTREAM, J.N.

1983: Gift exchange in the eighth

century BC. In Ha¨gg, R. (ed.), The Greek renaissance of

the eighth century BC: tradition and innovation

(Stockholm) 201–207.

COLDSTREAM, J.N.

1994: Pithekoussai, Cyprus and the

Cesnola Painter. AIONArchStAnt n.s. 1, 77–86.

COLONNA, G.

1995: Etruschi a Pitecusa nell’orientaliz-

zante antico. In Storchi Marino, A. (ed.), L’incidenza

dell’Antico = Studi in memoria di Ettore Lepore, 1

(Naples) 325–342.

CRIELAARD, J.P.

1995: Homer, history and archaeology:

some remarks on the date of the Homeric world. In

Crielaard, J.P. (ed.), Homeric questions (Amsterdam)

201–288.

CRISTOFANI, M.

1980: Reconstruction d’un mobilier

fune´raire archaı¨que de Cerveteri. Monuments Piot 63,

1–30.

D’AGOSTINO, B.

1977: Tombe ‘principesche’ dell’Or-

ientalizzante antico da Pontecagnano = Monumenti

Antichi ser. misc. II:1 (Rome).

D’AGOSTINO, B.

1979: Le necropoli protostoriche della

Valle del Sarno: la ceramica di tipo greco. AIONArch-

StAnt 1, 59–75.

D’AGOSTINO, B.

1990: Relations between Campania,

Southern Etruria and the Aegean in the eighth century

BC. In Descœudres, J.-P. (ed.), Greek colonists and

native populations (Canberra-Oxford) 73–97.

DALBY, A

. 1996: Siren Feasts: a history of food and

gastronomy in Greece (London).

DAREMBERG, C.

and

SAGLIO, E.

: Dictionnaire des Anti-

quite´s grecques et romaines (Paris [1875–1929]).

DE AGOSTINO, A.

1961: Populonia (Livorno). Scoperte

archeologiche nella necropoli, negli anni 1957–1960.

Notizie degli Scavi 63–102.

DE CARO, S.

(ed.) 1994: Il Museo Archeologico Nazionale

di Napoli (Naples).

DELATTE, A.

1955: Le Cyce´on. Breuvage rituel des

Myste`res d’E

´ leusis (Paris).

DUNBABIN, T.J.

1948: The Western Greeks (Oxford).

FREDERIKSEN, M.W.

1984: Campania (London).

GASTALDI, P.

1979: Le necropoli protostoriche della

Valle del Sarno: proposta per una suddivisione in fasi.

AIONArchStAnt 1, 13–57.

GIALANELLA, C.

1996: Pithecusae: le nuove evidenze da

Punta Chiarito. In De Caro, S. and Borriello, M. (eds.),

La Magna Grecia nelle collezioni del Museo Arche-

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

342

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

ologico di Napoli (exhibition catalogue: Naples) 259–

274.

GISLER, J.-R.

1995: Ere´trie et le Peintre de Cesnola.

Archaiognosia 8 [1993–94] 11–95.

HAINSWORTH, J.B.

1993: The Iliad: a commentary. Vol.

III: books 9–12 (Cambridge).

HANSEN, P.A.

1976: Pithecusan humour: the interpreta-

tion of ‘Nestor’s Cup’ reconsidered. Glotta 54, 25–53.

HIJMANS JR., B.L.

1992: Circe on Monte Circeo. Caeculus

1, 17–46.

HURWIT, J.M.

1993: Art, poetry and the polis in the age of

Homer. In Langdon, S. (ed.), From pasture to polis

(Columbia, Miss.-London) 14–42.

JACOBSTHAL, P.

1932: Leaina epi turoknestidos. Athe-

nische Mitteilungen 57, 1–7.

JENKINS, I.

and

SLOAN, K.

1996: Vases and Volcanoes: Sir

William Hamilton and his collection (exhibition catalo-

gue: London).

KARAGEORGHIS, V.

1983: Palaepaphos-Skales: an Iron

Age cemetery in Cyprus (Konstanz).

LORIMER,

H.L.

1950: Homer and the monuments

(London).

LUKE, J.

1994: The krater, kratos and the polis. Greece

and Rome 41, 23–32.

MARTELLI CRISTOFANI, M.

1978: La ceramica greco-

orientale in Etruria. In Les ce´ramiques de la Gre`ce de

l’Est et leur diffusion en Occident (Paris–Naples) 150–

212.

MATTEUCIG,

G.

1951: Poggio Buco (Berkeley–Los

Angeles).

MINTO, A.

1921: Marsiliana d’Albegna: le scoperte

archeologiche del Principe Don Tommaso Corsini

(Florence).

MINTO, A.

1931: Le ultime scoperte archeologiche di

Populonia (1927–1931). Monumenti Antichi 34, 289–

420.

MURRAY, O.

1994: Nestor’s cup and the origins of the

Greek symposion. AIONArchStAnt n.s. 1, 47–54.

MUSCARELLA, O.W.

(ed.) 1974: Ancient art: the Norbert

Schimmel collection (Cleveland exhibition catalogue:

Mainz).

ORSI, P.

1925: Siracusa. — Nuova necropoli greca dei

sec. VII–VI. Notizie degli Scavi 176–208.

PAPADOPOULOS, J.K.

1996: Euboians in Macedonia? A

closer look. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 15, 151–

181.

PASQUI, A.

1902: Mazzano Romano. Scavi del principe

Del Drago, nel territorio di questo comune. Notizie degli

Scavi 593–627.

PESERICO, A.

1995: Griechische Trinkgefa¨sse im mittel-

tyrrhenischen Italien. Archa¨ologischer Anzeiger 425–

439.

POPHAM, M.R.

1993: The main excavation of the building

(1981–83). In Popham, M.R., Calligas, P.G., Sackett,

L.H., Lefkandi II,2: The Protogeometric building at

Toumba: the excavation, architecture and finds (Lon-

don) 7–31.

POPHAM, M.R.

1994: Precolonization: early Greek contact

with the East. In Tsetskhladze, G.R. and De Angelis, F.

(eds.), The archaeology of Greek colonisation (Oxford)

11–34.

POPHAM, M.R., CALLIGAS, P.G.

and

SACKETT, L.H.

1989:

Further excavation of the Toumba cemetery at Lefkan-

di, 1984 and 1986: a preliminary report. Archaeological

Reports for 1988–1989, 117–129.

POPHAM, M.R.

and

LEMOS, I.S.

1995: A Euboean warrior

trader. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 14, 151–157.

POPHAM, M.R.

and

LEMOS, I.S.

1996: Lefkandi III. The

Toumba cemetery: the excavations of 1981, 1984, 1986

and 1992–4. Plates (London).

POPHAM, M.R., TOULOUPA, E.

and

SACKETT, L.H.

1982:

Further excavation of the Toumba cemetery at Lefkan-

di, 1981. Annual of the British School at Athens 77,

213–248.

POWELL, B.B.

1991: Homer and the origin of the Greek

alphabet (Cambridge).

POWELL, B.B.

1993: Did Homer sing at Lefkandi?

Electronic Antiquity 1.2.

RATHJE, A.

1990: The adoption of the Homeric banquet

in central Italy in the Orientalizing period. In Murray,

O. (ed.), Sympotica: a symposium on the symposion

(Oxford) 279–288.

RATHJE, A.

1994: Banquet and ideology: some new

considerations about banqueting at Poggio Civitate. In

De Puma, R.D. and Small, J.P. (eds.), Murlo and the

Etruscans: art and society in ancient Etruria (Madison,

Wisconsin) 95–99.

RICHARDSON, N.J.

1974: The Homeric Hymn to Demeter

(Oxford).

DAVID RIDGWAY

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

343

RIDGWAY, D.

1988: Western Geometric pottery: new

light on interactions in Italy. In Proceedings of the Third

Symposium on ancient Greek and related pottery,

Copenhagen 1987 (Copenhagen) 489–505.

RIDGWAY, D.

1992: The first Western Greeks (Cam-

bridge).

RIDGWAY, D.

1994: Daidalos and Pithekoussai. AIO-

NArchStAnt n.s. 1, 69–76.

RIDGWAY, D.

1995: Archaeology in Sardinia and South

Italy 1989–94. Archaeological Reports for 1994–1995,

75–96.

RIZZO, M.A.

1989: Cerveteri: il tumulo di Montetosto. In

Atti II Congresso Internazionale Etrusco, Firenze 1985

(Rome) 153–161.

ROBINSON, D.M.

1941: Excavations at Olynthus, X: metal

and minor miscellaneous finds (Baltimore).

ROMUALDI, A.

1994: Populonia tra la fine dell’VIII e

l’inizio del VII secolo a.C.: materiali e problemi

dell’Orientalizzante Antico. In La presenza etrusca

nella Campania meridionale = Atti delle giornate di

studio, Salerno — Pontecagnano 1990 (Florence) 171–

180.

SEAFORD, R.

1994: Reciprocity and ritual: Homer and

Tragedy in the developing city-state (Oxford).

SHERRATT, A.

1995: Alcohol and its alternatives. Symbol

and substance in pre-industrial cultures. In Goodman, J.,

Lovejoy, P.E., Sherratt, A. (eds.), Consuming habits:

drugs in history and anthropology (London).

SHERRATT, E.S.

1990: ‘Reading the texts:’ archaeology

and the Homeric question. Antiquity 64, 807–824

[reprinted in Emlyn-Jones, C., Hardwick, L., Purkis, J.

(eds.), Homer: readings and images (London 1992)

145–165].

SHERRATT, E.S.

1994: Commerce, iron and ideology:

metallurgical innovation in 12th–11th century Cyprus.

In Karageorghis, V. (ed.), Proceedings of the Interna-

tional Symposium: Cyprus in the 11th century BC,

Nicosia 1993 (Nicosia) 59–106.

SMALL, J.P.

1994: Eat, drink and be merry: Etruscan

banquets. In De Puma, R.D. and Small, J.P. (eds.),

Murlo and the Etruscans: art and society in ancient

Etruria (Madison, Wisconsin) 85–94.

SPARKES, B.A.

1962: The Greek kitchen. Journal of

Hellenic Studies 82, 121–37.

STRØM, I.

1971: Problems concerning the origin and

early development of the Etruscan Orientalizing style

(Odense).

TSAVELLA-EVJEN, H.

1983: Homeric medicine. In Ha¨gg,

R. (ed.), The Greek Renaissance of the eighth century

BC (Stockholm) 185–188.

VAN WEES, H.

1995: Princes at dinner: social event and

social structure in Homer. In Crielaard, J.P. (ed.),

Homeric questions (Amsterdam) 147–182.

VON

HASE,

F.-W.

1995: A

¨ ga¨ische, griechische und

vorderorientalische

Einflu¨sse auf das tyrrhenische

Mittelitalien. In Beitra¨ge zur Urnenfelderzeit no¨rdlich

und su¨dlich der Alpen (Mainz) 239–286.

WALDBAUM, J.C.

1978: From Bronze to Iron: the

transition from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age in the

Eastern Mediterranean (Go¨teborg).

WELLS, P.S.

1980: Culture contact and culture change:

Early Iron Age central Europe and the Mediterranean

world (Cambridge).

WEST, M.L.

1988: The rise of the Greek epic. Journal of

Hellenic Studies 108, 151–172.

WEST, S.

1994: Nestor’s bewitching cup. Zeitschrift fu¨r

Papyrologie und Epigraphik 101, 9–15.

WHITLEY, J.

1991: Style and society in Dark Age Greece

(Cambridge).

WINTER, I.J.

1995: Homer’s Phoenicians: history, ethno-

graphy or literary trope? (a perspective on early

Orientalism). In Carter, J.B. and Morris, S.P. (eds.),

The ages of Homer: a tribute to Emily Vermeule

(Austin, Texas) 247–271.

WISEMAN, T.P.

1995: Remus: a Roman myth (Cam-

bridge).

ZANCANI MONTUORO, P.

1983: Resti di tombe del VI

secolo a.C. presso Sorrento. Rendiconti Lincei ser. viii,

38:3–4, 1–8.

NESTOR’S CUP AND THE ETRUSCANS

OXFORD JOURNAL OF ARCHAEOLOGY

344

ß Blackwell Publishers Ltd. 1997

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

David L Hoggan President Roosevelt and The Origins of the 1939 War

David Gunkel Žižek and the Real Hegel

Johnson, David Kyle Natural Evil and the Simulation Hypothesis

Lambert, David Curriculum thinking, ‘capabilities’ and the place of geographical knowledge in schoo

David Thoreau Walden (And the Duty of Civil Disobedience) (Ingles)

David Icke Hitler And The Rothschilds

David Bentley Hart Atheist Delusions The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies

David Icke Alice In Wonderland And The Wtc Disaster

Dr Who Target 039 Dr Who and the Leisure Hive # David Fisher

Dr Who Target 011 Dr Who and the Creature from the Pit # David Fisher

David Icke Mono Atomic Gold A Secret Of Shapeshifting And The Reptilian Control

99 Regulowany kielich, regulowany dźwięcznik i grzeszny siódmy stopień Adjustable cup, adjustable be

David E Levis Presidents and the Politics of Agency Design, Political Insulation in the United Stat

Linus Torvalds and David Diamond Just for FUN The Story of an Accidental Revolutionary

Mettern S P Rome and the Enemy Imperial Strategy in the Principate

Diet, Weight Loss and the Glycemic Index

Ziba Mir Hosseini Towards Gender Equality, Muslim Family Laws and the Sharia

pacyfic century and the rise of China

Danielsson, Olson Brentano and the Buck Passers

więcej podobnych podstron