“To Sustain Illusion is All

That is Necessary”: The

Authenticity of Song

Performance in Early

American Sound Cinema

To Sus tain Illusion is All That is Necessary

Katherine Spring

I

n the second half of Radio Rhythm, a one-reel film

released by Paramount Pictures on 10 August

1929, popular radio crooner Rudy Vallee and his

band, the Connecticut Yankees, launch into a

performance of the number “You’re Just Another

Memory”. The popular song had been recorded by

Vallee and released on the Victor record label in June

of that year, and, as in that recording, Vallee in Radio

Rhythm takes up a solo on the clarinet. His onscreen

solo performance is rendered through formal strate-

gies typical of musical shorts produced during the

coming of sound: frontal staging, medium-to-long

shot scales, and minimal editing strengthen our un-

derstanding of this passage as an unadulterated

presentation of a musical performance, a direct tran-

scription of a pro-filmic event that transpired and was

recorded on a sound stage with minimal mediation.

1

Yet toward the end of the solo, our impression of an

unmodified performance comes under threat when,

after Vallee removes the instrument from his lips and

places it on the ground beside him, the sounds of the

clarinet continue on the soundtrack for nearly five

seconds.

This brief fissure in the synchronization of im-

age and audio nonetheless eludes the attention of

most audience members and in so doing fulfills the

objectives of what likely is playback, a technique

employed during the transition to sound that entailed

the prerecording of a song to which a performer

lip-synched during shooting. Playback had been

used

in

the

production

of

cinema’s

earliest

(pre–1920) sound films, but its introduction to Holly-

wood studios can be dated to October 1928, when

Douglas Shearer, a sound engineer at MGM, was

given producer Irving Thalberg’s blessing to institute

the practice during production of The Broadway

Melody.

2

Although playback became the conven-

tional method for recording song numbers in musical

films of subsequent decades, it was only one of three

practices of non-synchronous recording that Ameri-

can studios employed during the coming of sound.

The other two were dubbing, in which a voice was

added in post-production to a recorded image, and

voice-doubling, in which an actor lip-synched to a

song sung simultaneously by a vocalist located be-

yond the purview of the camera’s viewfinder but

within earshot of the microphone. Although each of

these three practices entails a different temporal

relationship between the recording of sound and that

of the image, they all produce the same pair of

illusions: embodiment, the illusion that the body seen

onscreen is the source of the voice emanating from

Katherine Spring is an Assistant Professor in the

Department of English and Film Studies at Wilfrid

Laurier University in Waterloo, Canada. Her book,

Saying it with Songs: Popular Music and the Coming

of Sound to Hollywood Cinema, is forthcoming through

Oxford University Press.

Correspondence to kspring@wlu.ca

Film History, Volume 23, pp. 285–299, 2011. Copyright © 2011 Indiana University Press

ISSN: 0892-2160. Printed in United States of America

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 285

the soundtrack, and simultaneity, the illusion that the

filming of the image and the recording of the voice

occurred concomitantly and in the same space.

3

The

combined effect of these illusions is an impression

of a performance’s authenticity; the final film is

deemed to have respected the spatial and temporal

integrity of a preexisting, pro-filmic event.

4

Notwithstanding the importance of the theo-

retical questions generated by practices of non-syn-

chronous recording (exemplified by the writings of

Michel Chion and Mary Ann Doane), the illusion of

authenticity served an important commercial func-

tion during the transition to sound, when the avowed

capacity for sound film to represent a preexisting

event constituted a vital component of marketing the

new medium.

5

Studio publicity and the films them-

selves positioned and promoted the singing star’s

voice as an attraction unto itself, a strategy especially

pronounced in musical shorts, whose commercial

appeal and aesthetic form derived from the onscreen

presentation of songs performed by established vo-

calists and musicians. The allure of what Donald

Crafton has dubbed “virtual Broadway” – the “simu-

lacrum of an in-person appearance” – yielded a set

of formal strategies for the translation of stage per-

formances into onscreen filmic renditions that could

circulate across the country.

6

While others have articulated these strategies

especially as they differ from the feature-length film’s

tendency to “harness” song performances to narra-

tive fiction, I am interested in considering more spe-

cifically how they position the onscreen presentation

of songs as authentic transcriptions of celebrity vo-

calists and musicians, and how the stylistic strate-

gies developed for the short film were modified to suit

the demands of feature-length narrative films that did

not necessarily showcase musical talent. Two ques-

tions guide this study. First, what formal techniques

of the medium were deployed in the service of signi-

fying the authenticity of musical performances? To

answer this question, I have selected for study a

sample of musical shorts produced by Paramount

Pictures between 1929 and 1931, primarily shot at

the company’s studio in Astoria, Queens. The prox-

imity of the studio to Broadway facilitated the casting

of musical personalities in early sound shorts, and

the resulting corpus of films suggests that the formal

devices described by Charles Wolfe in his study of

Vitaphone shorts were characteristic industry-wide

norms.

7

Like the Vitaphone shorts, the Paramount

films were organized around discrete, self-contained

song performances, what I call “star-song attrac-

tions”. This aesthetic, which I have elsewhere argued

profited the film and popular music industries alike,

was imported by feature-length films belonging to

musical and non-musical genres.

8

The translation of the star-song attraction to

non-musical features was not unproblematic, how-

ever, for the dramatic actors who starred in these

films did not perforce possess musical talents. In

order to accommodate the musical shortcomings of

dramatic actors, feature films necessarily violated the

conditions of performative authenticity deemed so

essential to song performances in short subjects.

With this in mind, my second question considers how

audiences responded to violations of authenticity

normally attributed to the star-song attraction. Here

the focus is not the failure of the illusion of simulta-

neity, as is the case in the aforementioned passage

of Radio Rhythm, but rather that of embodiment. If,

as scholars have claimed, the suppression of audi-

ence knowledge of technology is essential to main-

taining the illusions of embodiment and simultaneity,

one would expect a scandal of sorts to emerge

following the revelation of that technology to the

public.

9

Historians who describe the public’s anxiety

over practices of lip-synching and voice-doubling

during the transition to sound often cite a pseudo-ex-

posé titled “The Truth about Voice Doubling”, pub-

lished in the July 1929 issue of Photoplay and

revealing a handful of cases in which doublers were

used on Hollywood sets.

10

However, a case study of

a broader sample of public discourse, represented

by newspaper clippings in the Richard Barthelmess

scrapbook collection at the Margaret Herrick Library

in Los Angeles, illuminates a more heterogeneous

set of responses offered up by reviewers and fans.

Clippings extracted from local and syndicated news-

papers ranging from the Portland Oregonian to North

Carolina’s Greensboro Record demonstrate not only

filmgoers’ acquiescence to the practice of voice-

doubling but also their conviction in the value of

narrative plausibility and coherence over the discrete

star-song attraction, at least where non-musical fea-

ture-length films were concerned.

11

A number in narrative: the star-song

attraction

Following the release of Radio Rhythm, a reviewer for

Variety wondered “why Rudy Vallee dropped [his

trademark] megaphone to sing straight” in the film.

The answer is obvious: the film’s appeal lies in its

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 286

286

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

Katherine Spring

alleged transmission of the star’s image and voice,

the latter seemingly unhampered by visible appara-

tuses such as the megaphone.

12

Heard, ostensibly,

is Vallee’s “true” voice, a cultural ideal that, as Neepa

Majumdar points out, derives from modern concep-

tions of the human voice as the “key to the interiority

or to the ‘true’ self of the speaker”.

13

The transmission

of a celebrity’s authentic voice possessed commer-

cial value as well, demonstrated by the culture of the

star vocalist cultivated by media industries during the

early twentieth century across a variety of platforms,

notably Broadway, vaudeville, phonograph record-

ings, and radio. By the late 1920s, the proven appeal

of the singing star meant that, as Richard Koszarski

notes, celebrity vocalists were “better prospects for

screen stardom” than were other kinds of musicians,

like bandleaders.

14

Paramount’s musical shorts capitalized on the

established appeal of the singing star by utilizing a

range of formal devices to highlight the star-song

attraction, a self-contained unit of performance that

translated into material formats for sale (sheet music

and phonograph records) beyond the movie theater.

The prototypical approach for rendering the star-

song attraction preserved visual and sonic continuity

by way of long takes, medium-long shots, and frontal

staging.

15

A fastidious example is the one-shot film,

Favorite Melodies Featuring Ruth Etting, released 16

March 1929.

16

At the time of its release Etting was

known as the “Sweetheart of Columbia Records”,

having recorded numerous top-selling songs for the

label. Since November 1928 she had been starring

alongside Eddie Cantor in the Broadway hit,

Whoopee!, at the 1800-seat New Amsterdam Thea-

tre, where she introduced the torch song, “Love Me

or Leave Me”.

17

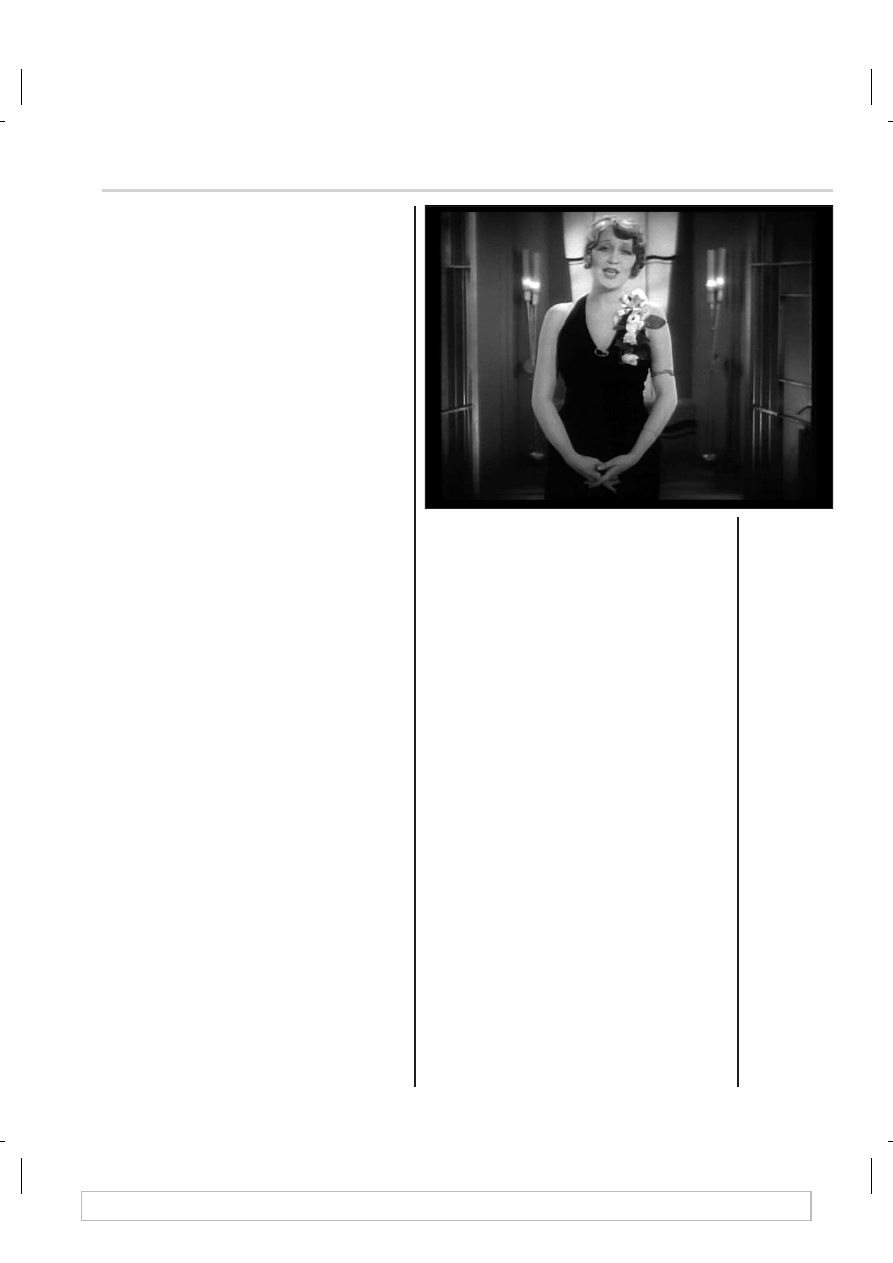

The filmic presentation of Etting’s

vocal performance seems to be the sole purpose of

the six-minute Favorite Melodies, which consists of a

single take that frames the star in a doorway of a

sparsely decorated set. The camera tracks briefly

toward her before settling on a medium-long shot,

where it rests for the short’s remainder. Singing in

direct address to the camera, and with minimal ges-

tures of her hands and arms, Etting performs two

songs: a ballad titled “My Mother’s Eyes” (which

audiences likely recognized as vaudevillian George

Jessel’s theme song) and a peppy dance tune,

“That’s Him Now”. During a brief pause between the

songs, Etting clears her throat, a gesture that draws

attention to the source of the film’s sound at the same

time that, in its capacity as a sonic “blemish” on the

soundtrack, it augments the impression of authentic-

ity inherent to the star-song attraction. While the

visual austerity with which the star-song attraction is

presented in Favorite Melodies might have been

owed in part to the studio’s attempt to prevent Etting

– a musical performer who never promoted herself

as an actress – from dialogue-based acting, it also

demonstrated a tendency to promote popular songs

as self-contained, purchasable commodities, a point

underscored by a reviewer for Film Daily who noted

that Etting “knows how to sell the numbers”.

18

Although the absence of even a token narrative

framework in Favorite Melodies defines the film as a

model star-song attraction, the integration of song

numbers into narrative contexts rarely threatened

their articulation of authenticity. For example, in Ethel

Merman in Her Future (released 6 September 1930),

self-contained song performances are flimsily moti-

vated by a fiction that casts Merman as a nameless

defendant in a courtroom occupied by a prosecutor,

defense attorney, and a judge whose bench towers

impossibly high above Merman’s character. The

courtroom setting gives pretext to the introduction of

two songs. The first is prompted when the defense

attorney requests of the judge, “May I ask [the de-

fendant] to tell the court in her own way just why she

is here?” The judge turns to Merman and states,

“Defendant, proceed”, and Merman launches into

“My Future Just Passed”, the lyrics of which provide

at best a feeble explanation for her ending up in a

courtroom. When she finishes singing, the judge

orders Merman’s release and adds, “Before you go,

I want you to tell me how you intend facing life. What

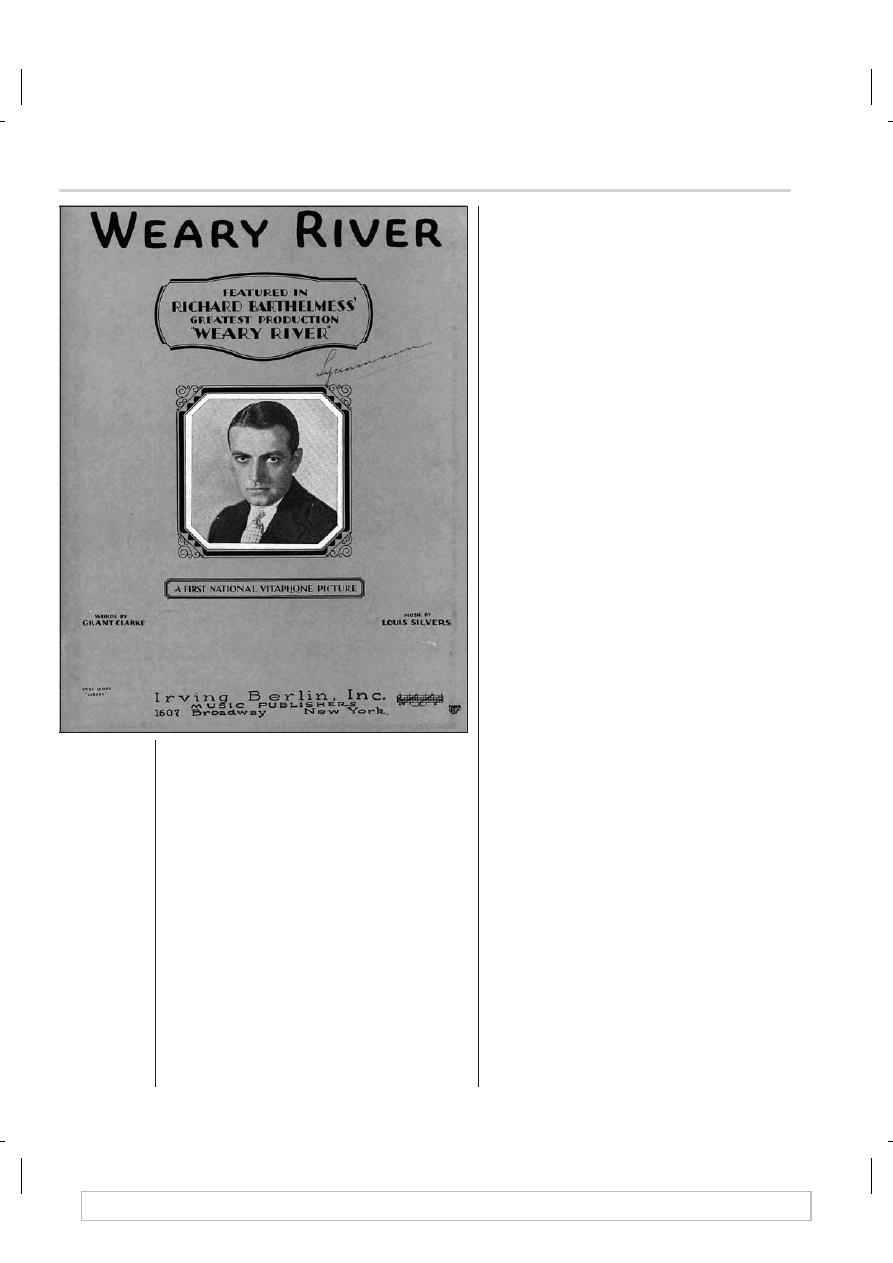

Fig. 1. The

camera in the

one-shot Favorite

Melodies

Featuring Ruth

Etting

(Paramount,

1929) records

the star from a

single vantage

point.

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 287

“To Sustain Illusion is All That is Necessary”

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

287

will you do? Where will you go?” Merman answers in

song with the lyrics, “Gonna take a train …” – an

improvised introduction to her performance of “Sing,

You Sinners”.

19

Throughout both song perform-

ances, any semblance of a subjectified narrative

space is attenuated by a static camera set-up that

frames Merman in a medium-long shot and planar

staging. Half of the film’s eight-minute duration is

rendered through this single set-up. During “My Fu-

ture Just Passed”, the film cuts to a slightly longer

shot for twelve seconds before it reverts to the origi-

nal camera position, and no editing is used through-

out the entirety of “Sing, You Sinners”. Notably, the

film also avoids cutting to images of the three char-

acters whom we assume are witnessing Merman’s

performance, resulting in the further weakening of a

narrative space that was tenuous to begin with. Fol-

lowing the performance of “Sing, You Sinners” the

short ends abruptly with a fade to black and the

appearance of the end title card without ever return-

ing to an establishing shot of the courtroom. In these

ways, the form of Ethel Merman in Her Future clearly

demarcates the boundary between the discrete star-

song performance and its narrative container.

In films that attempted to better integrate song

performances within narrative frameworks, the use of

different stylistic strategies contrasted those frame-

works with the star-song attraction as a discrete unit

of performance imbued with authenticity (and laid the

groundwork for the formal distinction between narra-

tive and numbers in musical films of ensuing dec-

ades). An illustrative example is Office Blues

(released 22 November 1930), in which Ginger Ro-

gers, then the nineteen-year-old star of the Broadway

musical comedy Girl Crazy, plays a stenographer

pining for the affections of her boss. The 29-shot film

alternates two stylistic patterns: an edited construc-

tion of narrative space, motivated mostly by the pres-

ence of an office coworker, and static long takes and

planar staging that are reserved for song perform-

ances (even when these performances are seated).

The film’s first minute, wherein Miss Gravis (Rogers)

is accosted by her coworker, Gregory (E.R. Rogers),

comprises eight shots with an average shot duration

of seven seconds and editing that is consistent with

norms of analytical and continuity editing. When Gre-

gory invites Gravis to lunch, for example, the film cuts

to her reaction in a more closely scaled medium shot.

A brief appearance by Gravis’s boss, Jimmy (Clair-

borne Bryson), gives the stenographer sufficient rea-

son to launch into “We Can’t Get Along”.

20

With the

exception of a three-second cutaway to an image of

Gregory gazing at Gravis as she sings, the entirety

of the song’s duration (2:09) is presented through a

single medium shot of Gravis.

The second song sequence removes us fur-

ther from the narrative space established in the film’s

opening minutes. Alone in the office after Gregory

leaves for lunch, Gravis begins to sing a fantasy

letter, “Dear Sir”, and the film dissolves to a surreal

set displaying a chorus line of women standing on a

stage built to resemble a notepad. In medium-long

shot, Gravis sings while standing in front of the

women; Jimmy then enters from stage left, singing

“Dear Miss, I just received your note”, and joins in the

fantasy song that codes romance as a business

transaction (“I’d like to take your tip and form a

partnership”). At the end of the song, the couple

kisses and the film dissolves back to Gravis seated

at her desk. As though to suggest that her fantasy

was shared with the object of her affection, Jimmy

appears with a letter in hand and, after some confu-

sion on Gravis’s part, announces, “Perhaps we’d

better discuss this in my office”. The couple exit and

– in a move that betrays the film’s pre-Code vintage

– we cut to the film’s final image, a door sign that

reads, “Busy Dictating”. The resolution provided by

this final event, in which Gravis’s wishes are fulfilled,

imparts a degree of dramatic unity that resonates

with the classical, unified construction of feature-

length films. But couched within this unified frame-

work resides a stylistic template for maintaining the

illusion of authenticity of song performance.

Signature instruments: musical

tools of authenticity

The early soundtrack comprised not just singing, of

course, but also the sounds of musical instruments,

and those sounds aided in the construction of

authenticity. An oft-cited account penned by Max

Steiner recalls the necessary onscreen depiction of

musical instruments whose sounds were heard on

the soundtrack:

Music for dramatic pictures was only used

when it was actually required by the script. A

constant fear prevailed among producers, di-

rectors and musicians, that they would be

asked: Where does the music come from?

Therefore they never used music unless it

could be explained by the presence of a

source like an orchestra, piano player, phono-

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 288

288

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

Katherine Spring

graph or radio, which was specified in the

script.

21

Steiner’s recollection was shared by film histo-

rian Irene Kahn Atkins:

[The coming of sound marked] the beginning

of the era of a shot that was to be repeated in

countless films: when an excuse for music was

needed, someone was seen turning on a pho-

nograph, putting the needle on the record, and

listening as the appropriate song or instrumen-

tal was heard on the soundtrack.

22

Perhaps because they did not operate under

the demands of classical narration, musical shorts

seem to have been exempted from the requisite

onscreen depiction of instruments. For example, al-

though the sounds of a piano and strings are heard

clearly on the soundtrack of Favorite Melodies Fea-

turing Ruth Etting, nary an instrument is seen; the

same observation holds for Office Blues and Ethel

Merman in Her Future, even when a relatively full

orchestration appears on the soundtrack. Instru-

ments also are absent from the images of Insurance

(August 1930), an Eddie Cantor sketch set in an

insurance office, although the star’s presentation of

“Now That the Girls Are Wearing Long Dresses” is

accompanied by the sounds of a jazz orchestra

including a string and horn section.

Since they did not necessarily supply a visual

pretext for music heard, what functions did musical

instruments serve when they appeared onscreen in

musical shorts? I suggest two, each of which en-

hanced the authenticity of song performance. First,

the display of instruments on screen facilitated audi-

ence identification with celebrities whose star perso-

nas were predicated at least in part on their use of

instruments. Like the voice, the musical instrument

could serve to signify a star’s authentic presence.

Radio Rhythm is a case in point. By the time the film

was released in August 1929, Vallee had become a

radio sensation, having signed earlier that year an

exclusive contract with NBC that resulted in weekly

national broadcasts sponsored by Fleischmann’s

Yeast. On the Fleischmann’s Yeast Hour program,

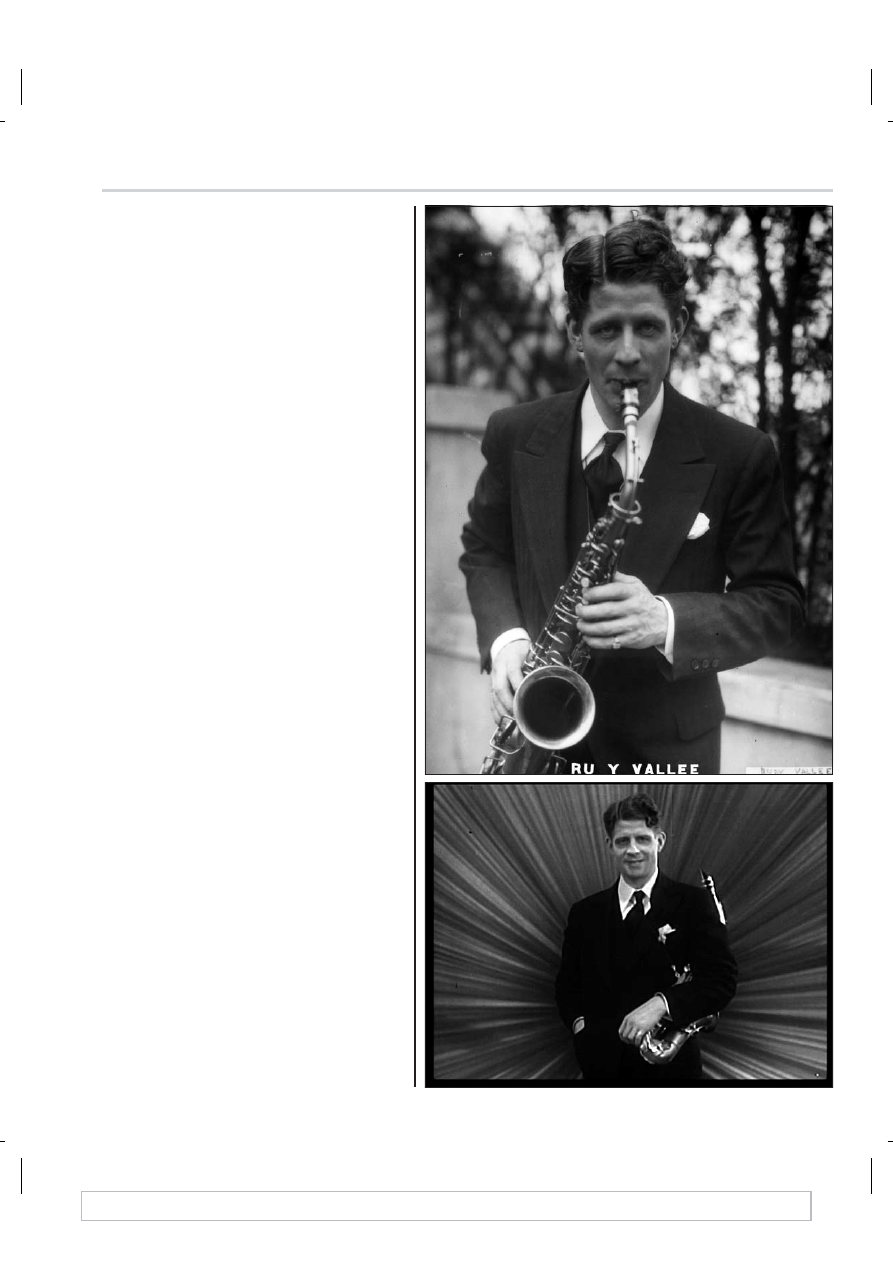

Fig. 2(upper). Rudy Vallee poses with saxophone for a news

photographer, ca. late 1920s/early 1930s. [Courtesy Library of

Congress.]

Fig. 3(lower). Rudy Vallee faces the camera in direct address

in the third shot of Radio Rhythm (Paramount, 1929).

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 289

“To Sustain Illusion is All That is Necessary”

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

289

Vallee distinguished himself not only by emphasizing

vocal solos more than any other bandleader but also

by developing a breathy, soothing style of singing –

crooning – that fans quickly interpreted as his expres-

sion of sincere emotion.

23

Vallee’s saxophone was a

defining element of his public persona, as evidenced

by its frequent citation (sometimes by Vallee himself)

in accounts of his musical education prior to star-

dom.

24

In addition, Vallee’s distinctive style of singing

owed to his emulation of techniques for playing the

saxophone – specifically, the technique of vibrato,

which he discovered was “particularly effective in

conveying emotional involvement”.

25

Vallee’s voice,

coupled with his adept handling of the saxophone

(and to a lesser degree, the clarinet), served as

immediate signifiers of his “true” presence.

The authenticity of this presence in Radio

Rhythm is strengthened by formal means. Vallee

appears first when a large circular panel, designed

to resemble the radio speaker seen in the previous

shot, parts down the center and recedes to reveal the

star standing and smiling, one hand in his jacket

pocket and the other cradling an alto saxophone that

hangs from his shoulder. A cut to a medium shot

briefly highlights the star before the film returns to the

initial camera set-up. After minimal editing around

three vantage points, Vallee introduces the song

“Honey”, a hit ballad that he and his orchestra had

recorded for Victor six months prior to the film’s

release. Vallee’s singing is rendered through a static

medium shot that ends only when “Honey” enters

into an instrumental break, followed by a seamless

segue into a second song, “You’re Just Another

Memory”. Now Vallee picks up his clarinet and starts

to play, and the film remains in the medium-long shot

set-up until Vallee begins warbling a verse. The pat-

tern established so far – a medium-long shot for

instrumental breaks, medium shots for vocal pas-

sages – changes only during the third song, the

peppy dance number titled “You’ll Do It Someday,

So Why Not Now?” With band members singing in

chorus and effecting synchronized hand gestures,

the film cuts to a medium shot when Vallee begins a

solo on the alto saxophone. That the film denies a

medium shot of a subsequent soloist, the tenor saxo-

phonist, and instead remains fixed on an establishing

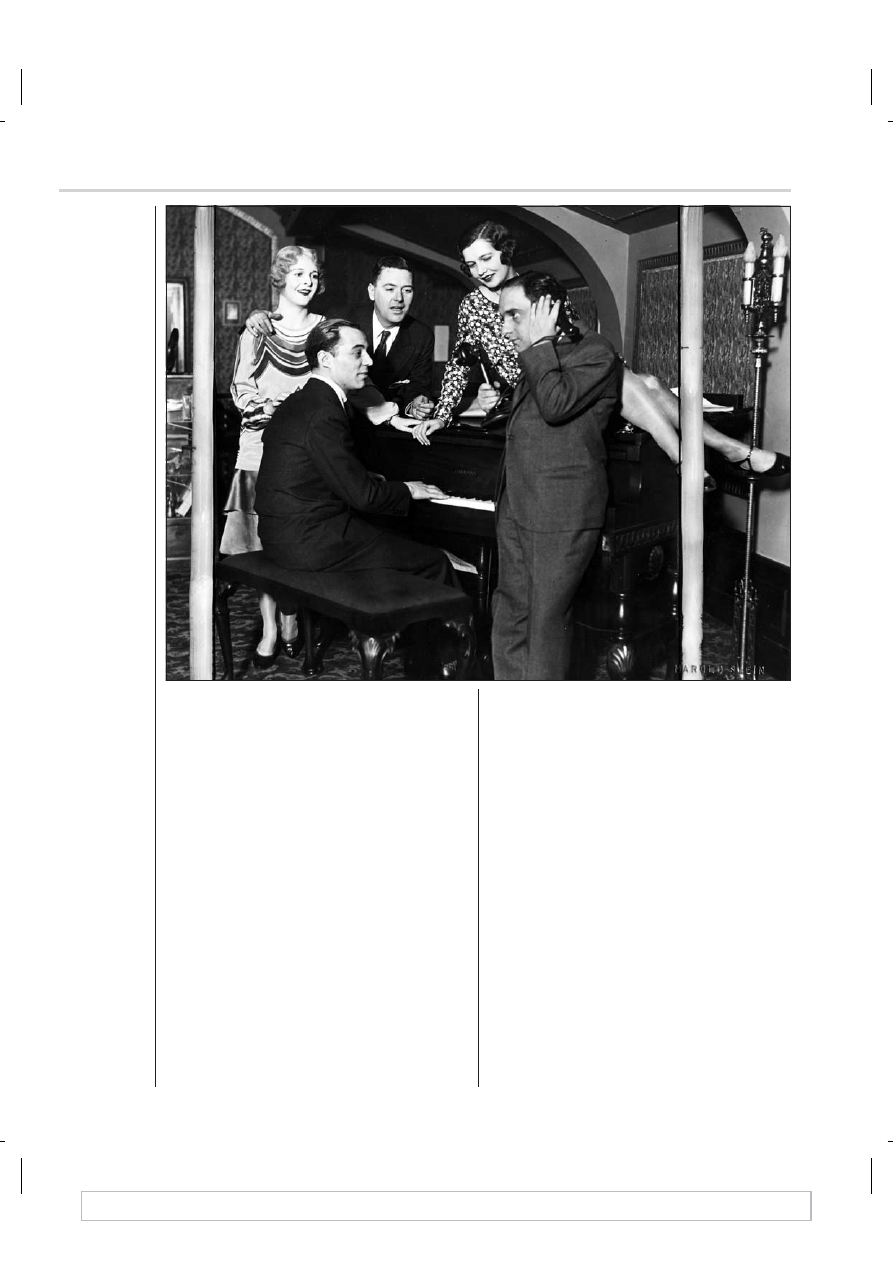

Fig. 4. A

publicity photo

snapped during

production of the

Broadway show

Present Arms

(1928) captures

Richard Rodgers

on his usual

perch at the

piano. Shown

from left, back

row: Flora Le

Breton, Charles

King, Joyce

Barbour; front

row: Richard

Rodgers, Lorenz

Hart.

[Courtesy

Photofest.]

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 290

290

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

Katherine Spring

shot is indicative of a formal pattern: Radio Rhythm

reserves medium shots exclusively for the attraction

constituted by Vallee singing and performing solos

on his signature alto saxophone. This shot scale,

combined with long takes and frontal staging, main-

tains audience attention on the star’s performing

body.

The onscreen appearance of hallmark instru-

ments as a means of conveying the authenticity of

embodiment was not exclusive to films starring vo-

calists. For example, in Makers of Melody (June 1929)

– a short in which famed songwriters Richard Rodg-

ers and Lorenz Hart offer a fictionalized account of

their songwriting inspirations – Rodgers first appears

seated at a piano, a position he tended to occupy in

publicity photographs. Nor was the practice confined

to Paramount’s earliest sound films. In A Rhapsody

in Black and Blue, released in September 1932, Louis

Armstrong is introduced singing and playing his sig-

nature muted trumpet (albeit in an utterly surrealist

fantasy setting), and the second shot of Bundle of

Blues (September 1933) begins with a close-up of a

pianist’s hands and tracks back until Duke Ellington

is revealed to be conducting his orchestra from his

customary perch on the piano bench.

All of these examples suggest that just like the

human voice, musical instruments functioned as ex-

ternal signifiers of a musician’s interior state, a point

underlined by philosopher Lydia Goehr in The Quest

for Voice. “At the moment of musical playing”, she

writes, “[the instrument’s] physicality, we could say,

becomes inseparable from the pure expressiveness

of our ‘souls’”.

26

Indeed, the attention accorded by

film form to the depiction of instruments in musical

shorts seems to function less to preclude the sort of

audience confusion that Steiner (and later Atkins)

identified and more to buttress the illusion of embodi-

ment. By showing stars playing their instruments, the

films foreclose the threat of “the mysterious”, as

Michel Chion has described it: “The face of a musi-

cian in the process of playing a piano, violin, harp or

any other instrument that does not involve the mouth

or breath is a mystery. It’s like a closed box, and we

cannot know if the hands are moving with or without

the participation of the mind and emotions.”

27

The

foregrounding of a star’s non-vocal musical talents

facilitated the illusion of embodiment.

As to their second function, musical instru-

ments also served to establish a diegetic setting, but

they frequently did so by exploiting ethnic and racial

stereotypes. Because the use of iconic musical in-

struments to code diegetic space in ethnic or racial

terms would become a conventional technique of

musical scoring in later feature-length films, it de-

serves brief consideration here. A good example is

found in Ol’ King Cotton, a baldly racist short that

starred among its African American cast the bass-

baritone

vocalist

George

Dewey

Washington

(dubbed the “colored Al Jolson”).

28

Released 27

December 1930, the short opens on a long shot of

what is presumed to be a Southern plantation; in the

background can be seen an expansive cotton field.

In the mid-foreground, Washington slouches at the

base of a sycamore tree, flanked on the right by a

banjo player and on the left by a man sitting with his

back to the camera and playing what appears to be

either a tenor guitar or banjo. Remaining in this

position, Washington sings the title song, a folk blues

number whose lyrics lament the hardship of picking

cotton (“I get so weary/ Of pickin’ and a-pickin’/ That

ol’ king cotton / Ain’t nothin’ but the weary blue”).

While he sings, the sounds of a jazz orchestra can

be heard on the soundtrack (including a violin, a

double-bass, a muted trumpet, and drums), but the

only instruments that appear in the image are the

banjo and tenor guitar (or tenor banjo) – two folk

instruments common enough in jazz bands of the

1920s and 1930s but also generally associated with

African American music thanks to the banjo’s appro-

priation by minstrel shows of prior decades and the

tenor guitar’s role in blues music.

29

The only other

instrument that appears in the film is a harmonica,

which a boy plays in accompaniment to Washing-

ton’s reprisal of “Ol’ King Cotton”, sung in the back-

room of a warehouse where Washington has taken

a job after traveling to a city “in the North”. Now the

song has acquired connotations of the character’s

nostalgia for home “down South”, and these conno-

tations find appropriate musical underscoring by the

harmonica, an instrument that Harold Courlander

called in his 1963 work, Negro Folk Music, U.S.A.,

“probably the most ubiquitous of Negro folk instru-

ments”.

30

The presence of instruments commonly

identified with African American culture of the early

twentieth century here helps to signify the authenticity

of Washington’s performance.

Not quite a scandal: responses to

the revelation of voice-doubling

The star-song attraction was valuable in both aes-

thetic and commercial terms. It packaged song per-

formances as discrete, authentic transcriptions

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 291

“To Sustain Illusion is All That is Necessary”

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

291

addressed to audiences who were given occasion

not only to enjoy celebrity performances through

filmic “virtual Broadway” but also to purchase sheet

music, piano player rolls, and phonograph records

in order to sustain the pleasure of the star-song

attraction beyond the movie theater. The perceived

significance of the star-song attraction in musical

shorts helps to explain its frequent incorporation into

feature-length, non-musical films of the transitional

era, including melodramas, westerns, and come-

dies.

31

However, whereas the established talents

and personas of the stars of musical shorts guaran-

teed audience confidence in the authenticity of song

performances, feature-length films conscripted dra-

matic actors into roles that required singing and/or

musical aptitudes – talents that did not generally

constitute the actors’ public personas and therefore

gave audiences reason to doubt the authenticity of

the song presentations. There was also the problem

of song motivation. The classical norms of narration

that the feature-length sound film had inherited from

the period of late silent cinema meant that, unlike in

musical shorts, the integration of self-contained song

performances required plausible motivation. One so-

lution came by way of writing musical tendencies into

a character, a technique that was easily assimilated

when a silent film star demonstrated an ability to sing.

In Sunny Side Up (1929), as Richard Maltby reminds

us, Janet Gaynor’s character is shown early on to be

an individual “given to expressing her innermost feel-

ings lyrically”, which justifies her character’s pen-

chant for breaking into song throughout the film.

Fortunately, Gaynor was deemed to possess at least

a tolerable singing voice.

32

But whereas numerous

silent stars succeeded in making the transition from

silence to speech, fewer proved capable of shifting

to the far more specialized act of singing. Their

deficits inspired the practices of playback, dubbing,

and voice-doubling.

When voice-doubling was used for dialogue,

as Donald Crafton points out, many fans accepted

the practice “simply as a component of Hollywood’s

trickery, not as false advertising or malicious deceit”,

but rather analogous to sound effects or make-up.

33

But song performances raised the stakes of authen-

ticity because the act required specialized skills and

also capitalized on the culture of the singing star.

How did audiences of early sound films respond to

the revelation of musical voice-doubling?

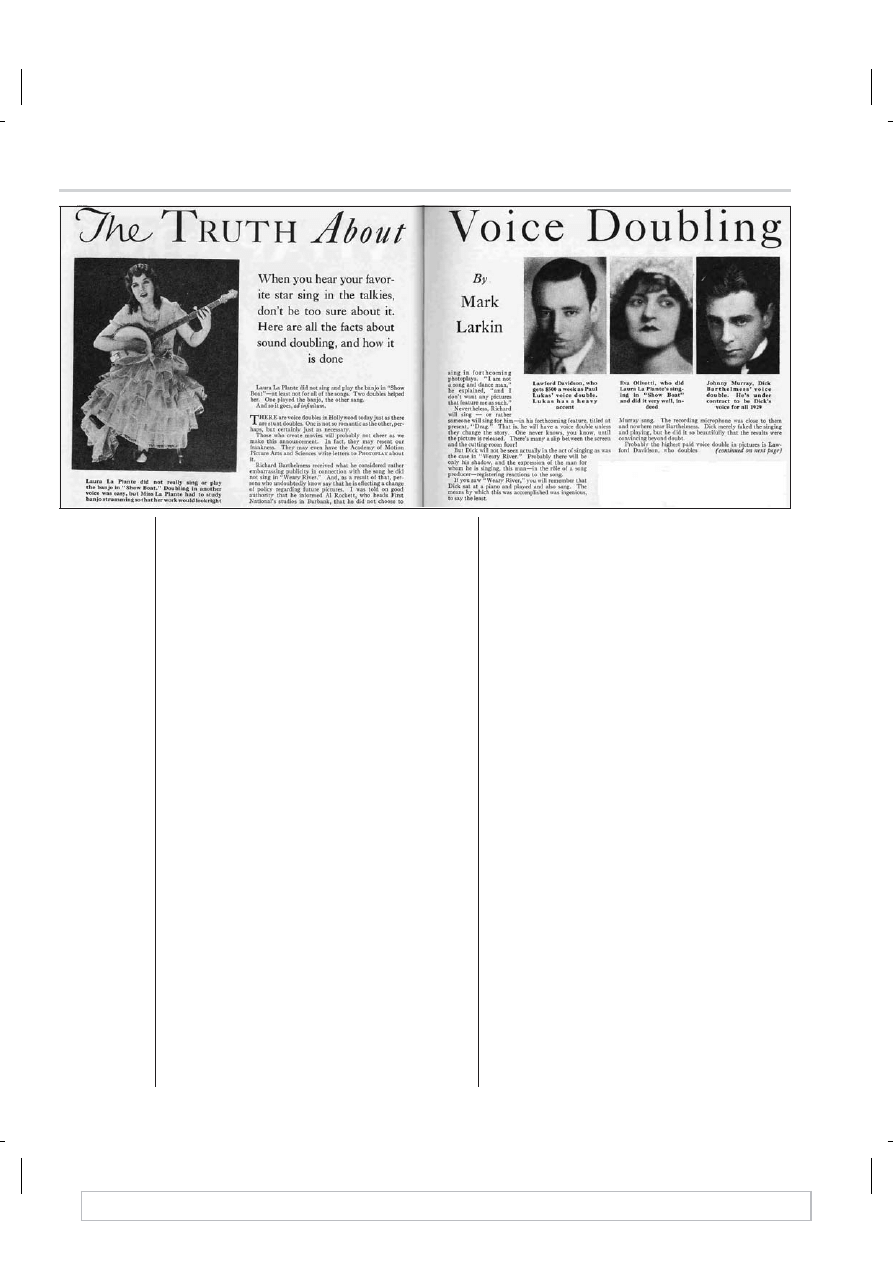

The most frequently cited article on this subject

is Mark Larkin’s aforementioned “The Truth about

Voice Doubling”, published in Photoplay in July 1929.

The four-page piece revealed what many filmgoers

already suspected: motion picture producers were

using voice-doublers (or “dubbers”) who sang off-

screen as the camera recorded the actors lip-

synching to songs – and they were doing the same

with off-screen instrumental musicians. Larkin’s

piece identified several actors who used doubles but

dedicated the most print to Richard Barthelmess,

star of the 1929 crime drama Weary River, about a

prisoner who warbles his way out the jailhouse and

into the limelight of the vaudeville stage. Elsewhere I

have discussed the commercial and narrative impor-

tance of popular songs in Weary River; Barthelmess’s

character sings the titular theme song four times over

Fig. 5. An

excerpt from the

article “The Truth

about Voice

Doubling’,

published in the

July 1929 issue

of Photoplay.

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 292

292

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

Katherine Spring

the course of the film, and each performance is

treated as a star-song attraction, though the individ-

ual responsible for singing in Barthelmess’s place

was Johnny Murray, a cornetist and vocalist who

worked at Hollywood’s Cocoanut Grove in the

1920s.

34

Although the Photoplay article poses as an

educational piece about details of studio practice

(“Here are all the facts about sound doubling, and

how it is done”, reads a subheading), the likelihood

that the magazine’s editors were banking on the

commercial value of letting the public in on a secret

is evidenced by the strategic timing of its appear-

ance: the article was published after several months

of speculation in the press and fan magazines about

the authenticity of Barthelmess’s singing voice.

The silent film star’s first sound film, Weary

River premiered in New York on 10 February 1929,

on the heels of a publicity campaign that promoted

the vocal talents of its star. An advertisement in Film

Daily situated the stern face of Barthelmess along-

side the caption, “You always knew he was the

screen’s greatest fighting lover …. You always knew

he was the greatest male star in pictures … but YOU

DON’T KNOW NOTHIN’ YET”, a bald reference to Al

Jolson’s legendary phrase from The Jazz Singer. In

a preview trailer, Barthelmess had even invited audi-

ences to hear him sing in his new production.

35

Suspicions that fakery was responsible for the star’s

singing voice surfaced in the weeks following the

film’s release, but the reviews were not all that dis-

paraging. In the 18 February edition of the Dallas

News, an author who signed off as “J.R. Jr.” claimed

that Barthelmess did not do his own singing, but that

the “Song Shenanigan [is] Really an Asset to ‘Weary

River’”.

36

The review instigated a swift defense from

Joseph E. Luckett, the Dallas branch manager of

First National, and James O. Cherry, owner of the

local Publix theater where the film screened. A com-

mittee of local musicians was appointed to analyze

and assess the matching of Barthelmess’s physical

performance with the sonic qualities of the voice on

the soundtrack. Meanwhile, the film’s release at the

Metropolitan Theatre in Houston generated similar

rumors, and another committee of musicians was

coordinated

there.

The

committees’

“studies”

yielded different opinions. Some insisted it was the

star’s voice they heard on the soundtrack, but others

were more skeptical. One member quipped, “If

Barthelmess actually does sing he should be in the

Smithsonian Institute. … The intensity of breathing so

essential to singing is entirely lacking”, and another

noted, “Barthelmess moves his lips with no move-

ment at all in his throat”.

37

But even committee mem-

bers who declared the singing fake observed that it

was so “well done that it does not detract from the

picture’s appeal”.

38

J.R. Jr. continued to defend the

practice of doubling on the grounds that it synthe-

sized for audiences two filmic diversions: a pleasant

voice and a “gorgeous face”.

39

The types of responses printed in the Dallas

News and Houston Chronicle were characteristic of

those that emerged in newspapers across the United

States. Various attitudes developed, only one of

which was admonishing of Barthelmess and/or First

National. A columnist for the Louisville Times warned,

“If (Barthelmess) doesn’t sing ‘Weary River’ then I,

for one, will never trust the screen again unless it

features someone like Al Jolson, who has already

been proved and found ‘not wanting’”.

40

A number

of fans were equally perturbed. Jean Betty Huber, of

Morris Plains, New Jersey, submitted this letter to the

editor of Picture Play magazine:

Please listen, you movie folk. We bow in hom-

age to your beauty and acting ability. We pay

hard-earned money to see your pictures – and

now to hear you speak as well – you who have

our complete admiration and support. Where

would you be without it? Now tell me that. If

these little Dick Barthelmess stunts are to con-

tinue, then here is one fan who is giving you a

fond farewell.

41

Later that year, Pearl H. McLaughlin, of Ham-

ilton, Ontario, wrote in to complain that the use of a

double in Weary River “entirely spoiled the picture”

for her. “My collecting days are over”, she an-

nounced, and “I think there is something wrong

somewhere and it does not lie with the star, but

perhaps in the studio system there is an error”.

42

When Bob Allen of Waynesburg, Pennsylvania, no-

ticed poor attendance at Barthelmess’s subsequent

film, Drag (1929), he submitted to Picture Play his

prediction that “the public is not going to put up with

Dick Barthelmess going through a picture on some-

body else’s shoulders”.

43

The complaints of a few disgruntled fans not-

withstanding, the majority of responses were gener-

ally supportive of the practice of voice-doubling –

though for different reasons. Numerous film review-

ers extolled the producers of Weary River for finding

a talented singer to substitute for Barthelmess’s

voice on the soundtrack. A columnist for the Hudson

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 293

“To Sustain Illusion is All That is Necessary”

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

293

Dispatch of Union City, New Jersey, confessed to not

knowing whether Barthelmess played the piano and

sang for the recording of the film, but added, “Who

cares. It is also well known that many of the most

charming foreign players in the talkies do not speak

the beautiful English that issues from the screen, and

it’s well for the ear that they don’t.”

44

Along similar

lines, in a piece titled “The Vocal Double”, an uniden-

tified author wrote, “That tenor [who sang for Barthel-

mess] must be safeguarded and kept on the job – it

would be disastrous if Mr. Barthelmess were to have

a different voice in each picture”.

45

These responses point up the doubled voice

as a feature that functioned at once as a source of

pleasure and a form of combined exchange value,

since profits could be derived from the commoditi-

zation of both star and song.

46

Similarly, the merged

value of star and voice was captured by extra-textual

consumer commodities generated by Weary River.

Sheet music for the theme song featured on its cover

an image of Barthelmess’s face, and phonograph

recordings were issued by no fewer than twenty

record labels in 1929 alone (including a Gene Austin

pressing for Victor).

47

The majority of recordings were

made on 1 February and served as well-timed adver-

tisements for the film set for premiere nine days later.

Another

category

of

responses

praised

Barthelmess’s and the film’s accurate synchroniza-

tion for their capacity to conceal the process of

doubling. A month following the printing of Pearl

McLaughlin’s grievance against the studio system,

Picture Play ran a letter from a reader who came to

Barthelmess’s defense. “Only a Girl of Fifteen”, from

Branford, Connecticut, stated, “I think that he ought

to be given credit for fooling every one as he did in

‘Weary River’. In my opinion, it would be harder to

have a double than to do the work itself.”

48

Similar

appraisals emerged in Los Angeles papers when the

film premiered on the West Coast on 1 March. Col-

umnist Marquis Busby of the Los Angeles Times

wrote, “Whether or not Barthelmess actually sings

the song I do not know. If he does not the voice

doubling is amazingly perfect.”

49

The Hollywood

News printed, “Had it not been for the rumor that he

didn’t [sing the theme song], no one would have

known the difference so perfect is the synchroniza-

tion”.

50

An article titled “Film’s Theme Song Stirs

Controversy” appeared one month later in the Los

Angeles Examiner, insisting similarly that if Barthel-

mess did not sing, “the synchronization is unbeliev-

ably accurate”.

51

It may be tempting to attribute these echoed

statements to the press’s coordinated promotion of

the film industry, given that Warner Bros. took out

paid advertisements regularly in these same Los

Angeles papers. But emphatic praise for the film’s

accurate synchronization appeared in other newspa-

pers, too. The Cleveland Plain Dealer noted that if

Barthelmess is not singing, then “there is the most

nearly perfect job of film doubling the screen has ever

heard”, while a columnist with the Greensboro Re-

cord of North Carolina proclaimed, “All we’ve got to

say is that it was darn clever faking and we’ll never

be quite convinced of it until Dick himself tells us he

wasn’t warbling the melody of the popular dance

tune”.

52

In the Louisville Courier of Kentucky, a re-

viewer noted that Barthelmess “gives the illusion that

he sings admirably and that is all that is necessary.

To sustain illusion is all that is necessary”.

53

The

attitude exemplified by these reviews attests to what

Crafton has described as the public’s fascination

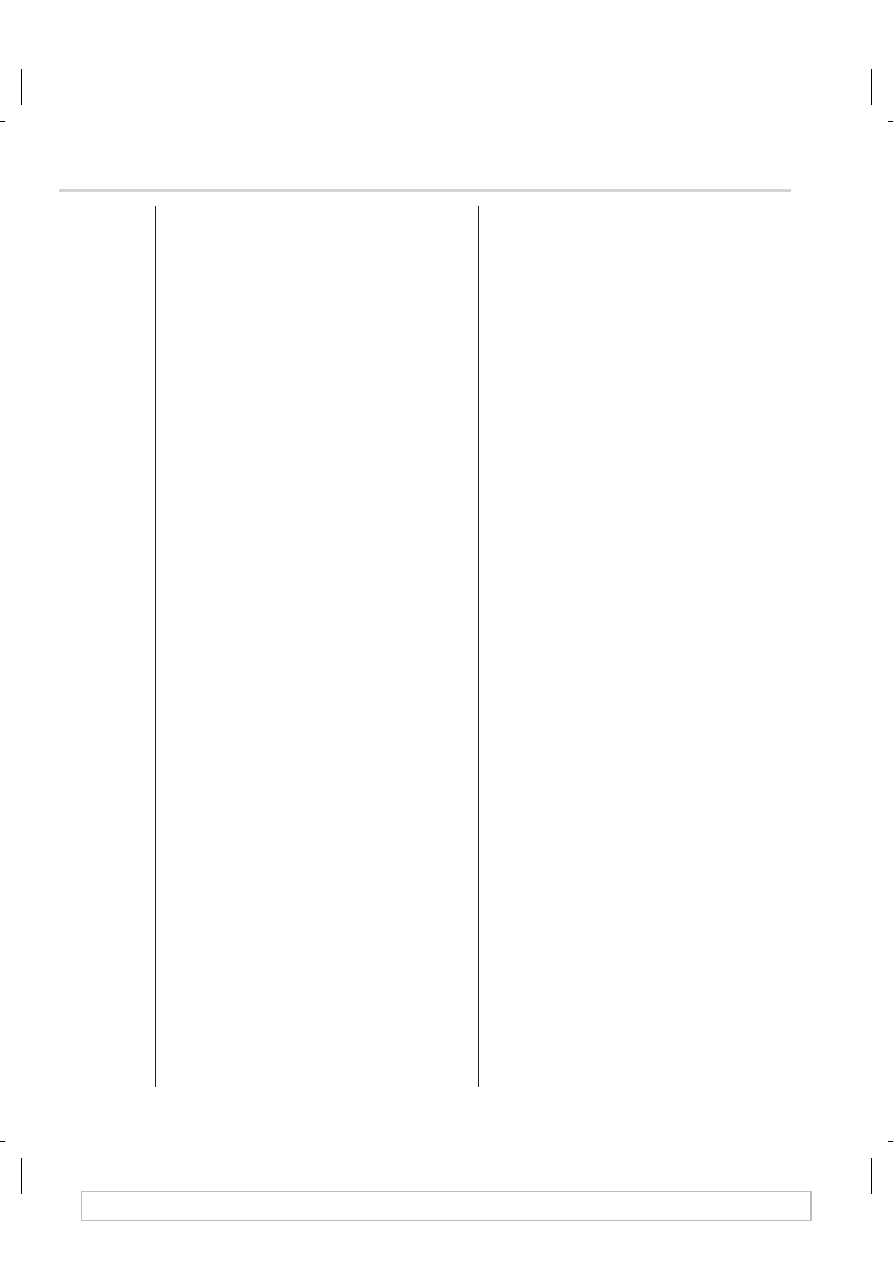

Fig. 6. Sheet

music of the title

song of Weary

River (1929)

features the

portrait of star

Richard

Barthelmess.

[Author’s

collection.]

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 294

294

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

Katherine Spring

with the new medium of synchronized sound: clearly

the marvel of electrical synchronization prevailed

over the potential threat posed by the practice of

doubling.

Yet another attitude resonates strongly with

Crafton’s observation of the public’s acceptance of

voice doubling as yet another element in the cin-

ema’s system of artifice. In the 12 May issue of the

Portland Oregonian, reviewer Stanley Orne asserted,

“In the matter of voice-doubling in the movies …

there can be only one crime, the crime of being

detected in your voice-doubling. The creed of the

dumb movie player might well be, Let not thy public

know what thy voice-double doeth”. Orne then ques-

tioned why audiences would complain about dou-

blers when they absolve filmmakers of other trickery:

It is well known that someone as obscure as

Tillie Plutz has such beautiful feet that hers are

invariably substituted in close-ups for face;

that the clothes which seem white in the pic-

tures actually are yellow in the Hollywood stu-

dios; that daredevils risk their lives to spare the

necks of handsome men who get screen credit

for bravery; that the movie magazines are

stuffed with stories written by journalists but

signed with the names of actors and actresses

who can’t write ten consecutive words sensi-

bly. Why, then, should we be squeamish over

the voice-doubling fraud? Frankly, I’m not.

54

Similarly, a reporter for the Cleveland News

wrote:

The great ocean liners we at times see being

tossed about by the terrific mid-Atlantic waves

are but toys bobbing about in a room about as

large as your home’s smallest bedroom.

Knowing this we still visualize the craft as being

an ocean liner on which maybe our hero and

heroine had gone aboard a short time before

as the great ship actually stood at its dock. …

Maybe if we did hear [Barthelmess’s] very best

vocalizing we’d be in something of a panic to

get the double back on the job.

55

The December 1929 issue of Picture Play

printed a letter from an individual residing in England

who pointed out that in Weary River, “the singing of

the convict had to be of such a quality as to cause a

sensation; a merely pleasant voice would have weak-

ened the conviction of the story”.

56

Voice-doubling of the star-song attraction was

understood by these filmgoers as an example of the

medium’s requisite dependency on artifice in the

name of narrative plausibility. In these terms, public

and press discourse mirrored a key debate about

sound recording that was transpiring among Holly-

wood studio technicians during this period. The de-

bate centered on two approaches to sound

recording: fidelity set as its goal “the perfectly faithful

reproduction of a spatiotemporally specific musical

performance (as if heard from the best seat in the

house)”, whereas intelligibility sought “legibility at the

expense of material specificity, if necessary”.

57

Fidel-

ity has been identified by scholars as the predomi-

nant goal during the initial phase of the transition to

sound, with intelligibility finally prevailing in the early

1930s. But, as James Lastra points out, the two

approaches actually worked in tandem with one an-

other; he cites Carl Dreher, a sound engineer at RKO

who maintained that, “since the reproduction of

sound is an artificial process, it is necessary to use

artificial devices in order to obtain the most desirable

effects. … This may entail a compromise between

intelligibility and strict fidelity.”

58

Although intelligibil-

ity was here conceived of as audibility of dialogue,

and not necessarily narrative plausibility, the ration-

ale behind Dreher’s insistence mirrored that which

underpinned some of the audience responses to

voice-doubling – namely, what one sacrificed in pure

fidelity (or authenticity) was gained in intelligibility (or

narrative plausibility).

In 1929, therefore, while some sound engi-

neers aspired to the representation of pure percep-

tual fidelity, audience members embraced film as a

medium subject to illusory codes both visual, as in

the use of daredevil stuntmen, and sonic, as in the

use of vocal-doubling. Their embrace was constitu-

tive of what Crafton has shown was the public’s faith

in the new technology of electric sound itself, which

the public made clear “would be acceptable in fea-

tures only if it did not interfere too much with the

traditional storytelling movie”.

59

The purchase on

authenticity made by sound in general, and the star-

song attraction in particular, could be sacrificed for

the sake of the preservation of classical narrative

coherence.

The fate of voice-doubling and

illusions of authenticity

In contrast with the feature film’s emphasis on narra-

tive plausibility, musical shorts authenticated star-

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 295

“To Sustain Illusion is All That is Necessary”

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

295

song attractions by using a set of stylistic techniques

that included long takes, frontal staging, and me-

dium-long shots. In so doing, the shorts facilitated

the illusions of embodiment and simultaneity, the two

conditions essential to creating the impression of

performative authenticity in sound cinema. When

star-song attractions translated to feature-length

films that showcased performances by dramatic

(and not necessarily musical) actors, the appear-

ance of authenticity was attained through practices

of voice-doubling and, with increasing frequency as

the sound era took hold, playback and post-dub-

bing. Indeed, by 1931, voice-doubling was all but

abandoned by Hollywood’s major studios, a shift that

might easily be attributed to a prudent reaction on

the part of producers toward disapproving fan mail

and journalistic assessments.

60

There was also the

problem of the cultural value associated with dou-

bling, articulated best by “sophisticate” filmmaker

Ernst Lubitsch in a syndicated article from Septem-

ber 1929. Lubitsch told the journalist:

No matter if the synchronization with the

player’s lips is mechanically perfect the effect

is bad. The feeling behind the words does not

coincide with the expression on the actor’s

face. Besides being artistically bad, I believe

that pictures in which doubles are used arouse

ill feeling on the part of audiences. If they know

that a double is speaking for an actor they

believe that they have been cheated. And they

have.

61

As the foregoing discussion has suggested,

however, these assessments do not accurately rep-

resent the scope of responses engendered by the

unveiling of voice-doubling to the public. Because

many filmgoers considered doubling a pleasurable

and even essential technique for some of Holly-

wood’s earliest sound films, it is perhaps more judi-

cious to attribute the eventual demise of the practice

not to negative reactions on the part of select fans or

filmmakers (like Lubitsch) but rather to institutional

practices, such as the studios’ cultivation of stables

of singing actors in the early 1930s, or their use of

new technologies that facilitated the much easier

process of post-production dubbing. That dubbing

quickly replaced voice-doubling as a norm of pro-

duction in Hollywood musicals thus underlines a

discrepancy that existed between the interests of

studio producers, whose goal of maintaining the

star-song attraction and the illusion of authenticity

through ever-efficient means precipitated the demise

of doubling and the adoption of post-production

dubbing, and the various expectations among audi-

ences.

In fact, varied responses and expectations with

respect to performative authenticity have resurfaced

in the recent history of popular music. Writing in 1992,

Steve Wurtzler observed the “scandals” associated

with contemporaneous revelations of lip-synching

among popular vocalists. In 1990, pop music duo

Milli Vanilli were found to have employed doubles for

the recording of their multi-million-selling album, Girl

You Know It’s True, and two years later, Luciano

Pavarotti “pulled a Milli Vanilli” in a performance in

Italy.

62

More recently still, audiences booed pop star

Ashlee Simpson off the stage of Saturday Night Live

when her lip-synched performance was laid bare to

the live studio audience (2004), and they chastised

Chinese organizers of the Summer Olympics for their

coordination of the lip-synching of a nine-year-old

performer (2008). Clearly, authenticity remains in

some domains a benchmark of value. On the other

hand, popular musicology has taught us that, from

the early 1990s through to today, many audience

members have adopted an ironic and knowing

stance (or “hipness”, as Lawrence Grossberg has

put it) with respect to the practice of lip-synching;

even the fans of Milli Vanilli remained unfazed while

around them buzzed music critics who cried foul.

63

Lip-synched musical performances at the Super

Bowl are now casually dismissed as convention;

previously unknown individuals attain celebrity stat-

ure on YouTube for their achievements in accurate

lip-synching to songs; and the use of pre-recorded

songs and post-production dubbing in film are widely

acknowledged and accepted practices. Considered

from this perspective, an account of the discourses

of authenticity of song performances in early sound

films provides us with a more accurate historical

context in which to assess claims about the novelty

of today’s so-called hip or ironic audiences.

Acknowledgements: The author wishes to thank Vincent

Bohlinger, Jinhee Choi, Lea Jacobs, Rob King, and Jeff

Smith for their insightful comments on earlier versions

of this paper. The author gratefully acknowledges that

financial support for this research was received from a

grant funded by Laurier Operating funds and the SSHRC

Institutional Grant award to Wilfrid Laurier University.

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 296

296

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

Katherine Spring

1.

In his seminal essay on Vitaphone shorts and The

Jazz Singer, Charles Wolfe distinguishes between

two aesthetic tropes situated at polar ends of a

spectrum of strategies used for the rendering of

musical performances in early sound films: the

“(filmic) presentation of a musical performance”,

which reiterated the techniques of contemporaneous

musical stage presentations (e.g. through direct

address); and the “harnessing of that performance

for a narrative fiction”, which entailed the repre-

sentation of a character’s (or characters’) subjecti-

fied space, an effect often achieved through the

codes of continuity editing. Charles Wolfe, “Vita-

phone Shorts and The Jazz Singer”, Wide Angle 12.3

(July 1990): 71.

2.

Richard Barrios, A Song in the Dark: The Birth of the

Musical Film (New York: Oxford University Press,

1995), 64–67; Mark A. Vieira, Irving Thalberg: Boy

Wonder to Producer Prince (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 2010), 92.

3.

Michel Chion dubs this combined effect “synchre-

sis”, which he defines as “the spontaneous and

irresistible mental fusion, completely free of any logic,

that happens between a sound and a visual when

these occur at exactly the same time”. For the pur-

poses of this paper, I find it useful to separate the

two misperceptions: one relating to the body that is

assumed to produce the sound, and another relating

to the temporal synchronization of sound and image.

Michel Chion, Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen

Claudia Gorbman (ed. and trans.) (New York:

Columbia University Press, 1994), 63.

4.

I hasten to qualify my use of the term authenticity.

First, I do not intend to evoke the ways in which the

word is used in scholarship of popular music and

music criticism, wherein it refers to “a socially

agreed-upon construct in which the past is to a

degree misremembered”, as Richard A. Peterson

has put it. Neither is my use of the term meant to

serve as a synonym for “fidelity”, a word that in

historical studies of film sound has come to represent

one of two approaches to sound recording – the

other being “intelligibility” – debated among sound

technicians working in Hollywood in the late 1920s

and early 1930s. For critical accounts of the models

of fidelity and intelligibility, see Rick Altman, “Sound

Space”, in Rick Altman (ed.), Sound Theory/Sound

Practice (New York: Routledge, 1992), 46–64; James

Lastra, Sound Technology and the American Cin-

ema: Perception, Representation, Modernity (New

York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 138–153;

Steve J. Wurtzler, Electric Sounds: Technological

Change and the Rise of Corporate Mass Media (New

York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 229–278.

See also Richard A. Peterson, Creating Country Mu-

sic: Fabricating Authenticity (Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1997), 5.

5.

Chion, Audio-Vision, 1–65 and passim; Mary Ann

Doane, “The Voice in the Cinema: The Articulation

of Body and Space”, Yale French Studies 60 (1980):

33–50. The marketing of sound film as a novelty is a

thread that weaves through Donald Crafton, The

Talkies: American Cinema’s Transition to Sound,

1926–1931 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons,

1997), and is especially pronounced in chapter 12,

“The New Entertainment Vitamin: 1928–1929”,

271–312.

6.

Crafton, The Talkies, 11, 63–88, 313–15.

7.

Wolfe, “Vitaphone Shorts and The Jazz Singer”.

8.

Katherine Spring, “Pop Go the Warner Bros., et al.:

Marketing Film Songs during the Coming of Sound”,

Cinema Journal 48.1 (Fall 2008): 68–89.

9.

For examples of this claim, see Michel Chion, The

Voice in the Cinema, Claudia Gorbman (trans.) (New

York: Columbia University Press, 1999), 128–136;

Doane, “The Voice in the Cinema”; Mary Ann Doane,

“Ideology and the Practice of Sound Editing and

Mixing”, in Teresa de Lauretis and Stephen Heath

(eds.), The Cinematic Apparatus (New York: St. Mar-

tin’s Press, 1980), 47–56; Rick Altman, “Moving Lips:

Cinema as Ventriloquism”, Yale French Studies 60

(1980): 67–79; Alan Williams, “Is Sound Recording

Like a Language?” Yale French Studies 60 (1980):

51–66.

10.

Wurtzler, Electric Sounds, 272–274; Neepa Majum-

dar, Wanted Cultured Ladies Only! Female Stardom

and Cinema in India, 1930s–1950s (Champaign, Ill.:

University of Illinois Press, 2009), 178. The Photoplay

piece has become a principal, if not exclusive, source

for scholars presumably owing to its accessibility in

Miles Krueger’s anthology of Photoplay documents

from the period. Mark Larkin, “The Truth About Voice

Doubling”, Photoplay (July 1929): 32–33, 108–110,

reprinted in Miles Kreuger (ed.) The Movie Musical

from Vitaphone to 42nd Street: As Reported in a Great

Fan Magazine (New York: Dover Publications, 1975),

34–37.

11.

One of the first entries into the Special Collections

at the Margaret Herrick Library, the Richard Barthel-

mess scrapbooks (hereafter RBS) were allegedly

compiled by Barthelmess’s mother, actress Caroline

Harris Barthelmess. Given the extraordinary quantity

of reviews and reports contained in the fifty-volume

set, it is more likely that the content was supplied by

a press clipping service working under the mother’s

employ.

12.

Quoted in Edwin M. Bradley, The First Hollywood

Sound Shorts (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland

& Co., 2005), 231.

Notes

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 297

“To Sustain Illusion is All That is Necessary”

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

297

13.

In European modernity, Majumdar argues, “the

human voice is associated with interiority, truth, and

authenticity. This philosophical position is articulated

forcefully by Hannah Arendt, who asserts that

through the act of speech, individuals “reveal actively

their unique personal identities”. Majumdar, Wanted

Cultured Ladies, 173, 178; Hanna Arendt, The Human

Condition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1998), 179. See also Charles Taylor, Sources of the

Self: The Making of the Modern Identity (Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1989), cited in

Amanda J. Weidman, Singing the Classical, Voicing

the Modern: The Postcolonial Politics of Music in

South India (Durham, NC: Duke University Press,

2006), 145–146.

14.

Richard Koszarski, Hollywood on the Hudson: Film

and Television in New York from Griffith to Sarnoff

(New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press,

1998), 202.

15.

Rick Altman attributes the “tyranny” of the continu-

ous, uninterrupted sound track to the reigning model

of perceptual fidelity. Altman, “Sound Space”, 256n4.

16.

The title of this film has elsewhere been cited as Ruth

Etting Sings Favorite Melodies and Favorite Melodies.

I use the title entered into the Library of Congress’s

Catalogue of Copyright Entries.

17.

“Love Me or Leave Me” was recorded by every major

record label company in the United States around

this period. Whoopee! ran through December 1929,

and Samuel Goldwyn’s film adaptation of the musical

comedy was released by United Artists in September

1930.

18.

Bradley, The First Hollywood Sound Shorts, 53, 230.

19.

The remainder of Merman’s performance follows

more or less the lyrics of the song co-written by Sam

Coslow and W. Franke Harling (1930).

20.

The song was co-authored by Vernon Duke and

Edgar Y. (“Yip”) Harburg, regular songwriters for the

productions at Paramount’s Astoria studio.

21.

Max Steiner, “Scoring the Film”, in Nancy Naumberg

(ed.), We Make the Movies (New York: W.W. Norton

and Co., 1937), 218.

22.

Irene Kahn Atkins, Source Music in Motion Pictures

(East Brunswick, NJ: Associated University Press,

1983), 31.

23.

Part of this effect owed to Vallee’s use of a “close-up”

technique of singing, for which he brought his lips

very near to the microphone. Allison McCracken,

“‘God’s Gift to Us Girls’: Crooning, Gender, and the

Re-Creation of American Popular Song, 1928–1933”,

American Music 17.4 (Winter 1999): 373–378.

24.

For example, see “Soulful Mr. Vallee”, New York

Times (4 August 1929): X5; “Rudy Vallee Life Marked

by Successes”, Los Angeles Times (9 February

1930): B15; and Rudy Vallee, “Vagabond Dreams

Come True”, Milwaukee Journal (28 March 1930): 3.

25.

McCracken, “God’s Gift”, 376.

26.

Lydia Goehr, The Quest for Voice: On Music, Politics,

and the Limits of Philosophy (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1998), 122.

27.

Michel Chion, “Mute Music: Polanski’s The Pianist

and Campion’s The Piano”, in Daniel Goldmark,

Lawrence Kramer, and Richard D. Leppert (eds),

Beyond the Soundtrack (Berkeley: University of Cali-

fornia Press, 2007), 94.

28.

Crafton, The Talkies, 590n11.

29.

Jeffrey J. Noonan, The Guitar in America: Victorian

Era to Jazz Age (Jackson, Miss.: University Press of

Mississippi, 2008), 15–20.

30.

Harold Courlander, Negro Folk Music, U.S.A. (New

York: Columbia University Press, 1992 [1963]), 216.

31.

During the 1929–1930 season, for example, popular

songs appeared in vocal or instrumental form in more

than half of all feature films produced by the major

motion picture companies. Katherine Spring, “Say It

with Songs: Popular Music in Hollywood Cinema

during the Transition to Sound, 1927–1931” (Ph.D.

diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2007), 250.

32.

Film reviewer Mordaunt Hall reported in the New York

Times, “Miss Gaynor’s voice may not be especially

clear, but the sincerity with which she renders at least

two of her songs is most appealing”. Mordaunt Hall,

“The Screen”, New York Times (4 October 1929): 32.

For a more general discussion of silent film stars who

succeeded in early sound films, see Crafton, The

Talkies, 490–495.

33.

Crafton, The Talkies, 510–511.

34.

Spring, “Pop Go the Warner Bros.”, 76–81. In some

newspapers, the voice double was misidentified as,

variously, Grant Withers, Frank Withers, and Frank

Rivers. See, for example, Franc N. Dillon, “‘Voice

Doublers’ Reap Coin Talking for Movie Stars”, New-

ark Star-Eagle (16 February 1929): n.p., RBS; Jerome

A. Lischkoff, “Richard Sings in Jail”, Cincinnati Post

(8 April 1929): n.p., RBS; J.R. Jr., “Barthelmess Fails

to Sing Again Here”, Dallas News (30 March 1929):

n.p., RBS; untitled clipping, Charleston News (4 April

1929): n.p., RBS.

35.

Advertisements for Weary River, Film Daily (8 January

1929): 4; Film Daily (30 January 1929): 10–11;

Crafton, The Talkies, 509.

36.

J.R. Jr., “Song Shenanigan Really an Asset To ‘Weary

River’”, Dallas News (18 February 1929): n.p., RBS

(emphasis added).

37.

“Musicians Committee Declares Singing in ‘Weary

River’ Faked”, Houston Post (3 March 1929): n.p.,

RBS.

38.

Ibid.

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 298

298

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

Katherine Spring

39.

J.R. Jr., “Notes on the Passing Show”, Dallas News,

n.d., n.p., RBS.

40.

Untitled clipping, Louisville Courier (30 April 1929):

n.p., RBS.

41.

Jean Betty Huber, “Richard Barthelmess’s Decep-

tion”, Picture Play, clipping dated January 1929 (?),

RBS.

42.

“That ‘Weary River’ Double”, Picture Play (November

1929): n.p., RBS.

43.

“A Fan Loses Faith”, Picture Play (December 1929):

n.p., RBS.

44.

“Theme Song Effective In Next Stanley Film”, Union

City Hudson Dispatch (11 April 1929): n.p., RBS.

45.

Unidentified clipping, RBS.

46.

In her examination of dubbing practices in Hollywood

musicals and the soundtrack albums they spawned,

Marsha Siefert notes, “Dubbing just any image with

a beautiful voice would not do. It is the combination

of the exchange value of star and sound that made

the eventual industrialization and merchandizing of

song dubbing through soundtrack albums a suc-

cess”. Marsha Siefert, “Image/Music/Voice: Song

Dubbing in Hollywood Musical”, Journal of Commu-

nication 45.2 (Spring 1995): 46–47.

47.

The most accessible discography of recordings from

this period can be found at Tyrone Settlemier, The

Online Discographical Project, http://www.78dis-

cography.com/ (accessed 10 January 2011) and its

linked, searchable database at Honking Duck 78s,

http://honkingduck.com/mc/discography/

(ac-

cessed 10 January 2011).

48.

“Only a Girl of Fifteen”, Picture Play (December 1929):

n.p., RBS.

49.

Marquis Busby, “Film Based on Melody Appealing”,

Los Angeles Times (2 March 1929): 7.

50.

“Theme Song is Melody Hit”, Hollywood News (1

March 1929): n.p., RBS.

51.

“Film’s Theme Song Stirs Controversy”, Los Angeles

Examiner (7 April 1929): n.p., RBS.

52.

W. Ward Marsh, “About Girls and Curves, Barthel-

mess’ [sic] Voice and a Letter From John Royal”,

Cleveland Plain Dealer (24 February 1929): n.p., RBS;

“Did Dick Sing?” Greensboro Record (27 April 1929):

n.p., RBS.

53.

Untitled clipping, Louisville Courier (29 April 1929):

n.p., RBS.

54.

Stanley Orne, “Critic Makes Light of Voice Doubling”,

Portland Oregonian (12 May 1929): n.p., RBS.

55.

“Dick’s Voice? – No”, Cleveland News (1 March

1929): n.p., RBS.

56.

F.J. Raleigh, letter, Picture Play (December 1929):

n.p., RBS.

57.

Lastra, Sound Technology, 139.

58.

Ibid., 142–143, 189.

59.

Crafton, The Talkies, 226.

60.

Steve Wurtzler supplies evidence for this position in

a quote from a report by the Progress Committee of

the Society of Motion Picture Engineers, dated Feb-

ruary 1930, in which the authors cite a “public reac-

tion against” voice-doubling. Wurtzler, Electric

Sounds, 272.

61.

Dan Thomas, “Voice ‘Double’ Will Vanish Soon,

Lubitsch Predicts”, Pittsburgh Press (22 September

1929): 71.

62.

Doug Camilli, “Showcase”, Montreal Gazette (25

October 1992): D9, quoted in Christopher Martin,

“Traditional Criticism of Popular Music and the Mak-

ing of a Lip-synching Scandal”, Popular Music and

Society 17.4 (Winter 1993): 76–77. Martin provides

an excellent account of the construction of the Milli

Vanilli “scandal” and the discourse that helped to

define it.

63.

Martin, “Traditional Criticism”, 70–77. On the “hip-

ness” of contemporary music audiences, see

Lawrence Grossberg, We Gotta Get Out of This Place:

Popular Conservatism and Postmodern Culture (New

York: Routledge, 1992), 225–227.

Abstract: “To Sustain Illusion is All That is Necessary”: The Authenticity of

Song Performance in Early American Sound Cinema,

by Katherine Spring

In musical shorts, song performances were rendered through a set of stylistic techniques emphasizing

performative authenticity and synchronicity. By contrast, the integration of song performances into

feature-length films of the same period led to the use of non-synchronous recording practices, such as

voice-doubling, for dramatic actors who did not possess musical talent. Newspaper clippings in the

Richard Barthelmess scrapbooks (Special Collections, Margaret Herrick Library) indicate that film audi-

ences generally accepted voice-doubling as a necessary element of cinematic artifice.

Key words: Authenticity, Richard Barthelmess, Weary River, dubbing, Paramount Pictures, playback, voice

double.

FILM HISTORY: Volume 23, Number 3, 2011 – p. 299

“To Sustain Illusion is All That is Necessary”

FILM HISTORY Vol. 23 Issue 3 (2011)

299

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Garipzanov, The Cult of St Nicholas in the Early

54 767 780 Numerical Models and Their Validity in the Prediction of Heat Checking in Die

Illiad, The Role of Greek Gods in the Novel

THE IMPORTANCE OF SOIL ECOLOGY IN SUSTAINABLE AGRICULTURE

Catalogue of the Collection of Greek Coins In Gold, Silber, Electrum and Bronze

Changes in the quality of bank credit in Poland 2010

The Grass Is Always Greener the Future of Legal Pot in the US

FIDE Trainers Surveys 2013 07 02, Uwe Boensch The system of trainer education in the German Chess F

Oren The use of board games in child psychotherapy

The Extermination of Psychiatrie Patients in Latvia During World War II

Tilman Karl Mannheim Max Weber ant the Problem of Social Rationality in Theorstein Veblen(1)

Evidence and Considerations in the Application of Chemical Peels in Skin Disorders and Aesthetic Res

The Study of Solomonic Magic in English

Nathan J Kelly The Politics of Income Inequality in the United States (2009)

The Role of Medical Diplomacy in Stabilizing Afghanistan

Gerhard F Hasel The Theology of Divine Judgement in the Bible (1984)

The evolution of brain waves in altered states

The Problem of Internal Displacement in Turkey Assessment and Policy Proposals

więcej podobnych podstron