A VIDEO TEL PRODUCTION

NAVIGATING IN ICE

A u th o r: N IG E L K IT C H E N

i I IVIDEO TEL

V I D E O T E L P R O D U C T I O N S

8 4 N E W M A N S T R E E T

L O N D O N W I T 3 E U , U K

T : + 4 4 ( 0 ) 2 0 7 2 9 9 1 8 0 0

F: + 4 4 ( 0 ) 2 0 7 2 9 9 1 8 18

• •

'

V

NAVIGATING IN ICE

A VIDEOTEL PRODUCTION

The Producers would like to acknowledge the assistance of:

The M a s te rs , O ffic e rs an d C rew s o f

M V Berge N o rd , M V O tso an d M V Purple S ta r, M V A tla n tic K in g fis h e r

A n d ro m e d a M a n a g e m e n t Ltd

A tla n tic T o w in g L im ite d

Bergesen d.y. ASA

The B ritis h A n ta rc tic Survey

B ritis h Film In s titu te

Finnish In s titu te o f M a rin e Research

Finnish M a ritim e A d m in is tra tio n

Finnish In s titu te o f M a ritim e Research

G auss m bH

H a n s e a tic S h ip p in g Co. Ltd

In d o C h in a Ship M a n a g e m e n t (U K ) Ltd

In te ro rie n t N a v ig a tio n Co. Ltd

In te rn a tio n a l M a ritim e O rg a n iz a tio n

K v a e rn e r M a sa -Y a rd s A r c tic T e ch n o lo g y (M A R C )

O C IM F

T E S M A H o ld in g

T ho re se n & Co. (B a n g k o k ) Ltd

U N IC O M M a n a g e m e n t services

C O N S U LT A N T S :

S ir W illia m C o d rin g to n

S tu a rt Law rence

PRODUCERS:

Robin Jackson

Peter W ild e

W RITER / DIRECTO R:

A n d y H u m p h re ys

P R IN T A U T H O R :

N ig e l K itc h e n

W a rn in g :

A n y u n a u th o ris e d c o p y in g , h irin g , le n d in g , e x h ib itio n d iffu s io n , s o le , p u b lic p e rfo rm a n c e o r o th e r e x p lo ita tio n o f th is v id e o is s tr ic tly p ro h ib ite d a n d m a y

re s u lt in p ro s e c u tio n .

© C O P Y R IG H T V id e o te l 2 0 0 5

T h is v id e o is in te n d e d t o re fle c t th e b e s t a v a ila b le te c h n iq u e s a n d p ra c tic e s a t th e tim e o f p ro d u c tio n , it is in te n d e d p u re ly a s c o m m e n t. N o re s p o n s ib ility

is o c c e p te d b y V id e o te l, o r b y a n y fir m , c o rp o ra tio n o r o rg a n is a tio n w h o o r w h ic h h as b e e n in a n y w o y c o n c e rn e d , w ith th e p ro d u c tio n o r a u th o ris e d

tr a n s la tio n , s u p p ly o r s o le o f th is v id e o fo r a c c u ra c y o f a n y in fo r m a tio n g iv e n h e re o n o r fo r a n y o m is s io n h e re fro m .

C O N T E N T S

1.

IN T R O D U C T IO N - T H E NEED FOR T H IS BO O K

6

2.

A B O U T T H IS B O O K _______________________________________________________________ 6

2.1

W ho is th e tra in in g package for?

2.2

Key m essages to be understood

2.3

U sing th e tra in in g package

2.4

Preparing fo r ru n n in g tra in in g sessions

2.5

R unning th e tra in in g sessions

3.

TH E D AN G ER OF ICE

7

3.1

T he d iffe re n t types o f ice

3.2

Icebergs

4.

VO YA G E PREPARATION: W H A T TYPE OF VO YAG E IS IT?

11

4.1

W ill you be e n te rin g an ice zone?

4.2

T he M a ste r

4.3

T he C h ie f O ffic e r

4.4

T he C h ie f Engineer

4.5

O th e r checks

ICE C O N D IT IO N A N D M E T E O R O L O G IC A L REPORTS

5.1

Ice N a v ig a tio n in C a n a d ia n W aters

5.2

Finnish M a ritim e A d m in is tra tio n

W H A T IS TH E SHIP'S C A P A B IL IT Y ?

7.1

W ho requires an Ice Class?

7.2

Types o f ship

7.3

Ice c la s s ific a tio n

7.4

C rite ria fo r in s ta lle d p ro p u lsio n pow er

4

aaa§0

7.5

W h a t are the Finnish-Sw edish Ice Classes?

7.6

C e rtific a te s

7.7

Engine room m a ch in e ry (p ro p u ls io n )

7 .8

T rim an d s ta b ility

W H A T T O L O O K O U T FOR: KEEPING A KEEN W A T C H

8.1

Iceberg m o n ito rin g

8 .2

Pack ice

W H A T T O DO W H E N A P P R O A C H IN G ICE

9.1

W h y fo llo w in g procedures is im p o rta n t

9.2

S afety checks

9.3

E lim in a te o r reduce p o te n tia l hazards

10.1

S h ip -h a n d lin g rules

10.2

C o m m u n ic a tio n w ith e n g in e room

10.3

Entering th e ice

10.4

Use o f engines and rudde r

10.5

R am m ing and b a ckin g

10.6

Freeing a tra p p e d ship

11.

W O R K IN G W IT H A N ICEBREAKER

24

11.1

C o m m u n ic a tio n s

11.2

H ow the ice b re a ke r breaks the ice

11.3

F o llow ing the iceb re a ke r's p ath

11.4

Em ergencies

1.

INTRODUCTION - TH E NEED FOR TH IS BOOK

Ice floes and icebergs obstruct shipping lanes, delaying transit and creating hazards for

both the ships and those on board. These environm ental conditions have caused some of

history's m ost famous m aritim e disasters - most notably, the sinking of the Titanic off the

coast of Newfoundland in April 1912.

Sea ice is treacherous and dangerous. Ernest Shackleton, the renowned British explorer,

found out just how dangerous when his ship, the Endurance, became trapped in pack ice

at the start of the 1914 expedition to Antarctica. Over the subsequent few weeks his ship

was slow ly crushed and destroyed leaving him and his crew stranded having to wait

nearly 18 m onths fo r rescue.

Today, rescue operations are less risky, but the wise m ariner w ill always treat ice w ith the

utm ost respect and observe the understood principles of operating safely and

successfully in ice zones during the (Winter) m onths when sea ice is to be expected.

2.

ABO U T TH IS BOOK

This w orkbook aims to raise awareness and im prove ice navigation safety procedures. It

covers a w ide range o f issues associated w ith navigating in ice including:

• the different types of ice and icebergs;

• preparing the voyage;

• your ship's capabilities;

• how to ensure safe passage through ice; and

• how to w ork w ith an icebreaker.

The training package w ill help make your crew aware of the dangers they may meet and

w ill also help you train them to fo llo w the correct safety measures at all times.

2.1

WHO IS THE TRAINING PACKAGE FOR?

The training package is aimed at the entire crew of any ship that is to sail into ice-prone

zones, but is specifically targeted at Masters, Deck and Engineering Officers.

2.2

KEY MESSAGES TO BE UNDERSTOOD

• How to recognise different types of ice

• The obstacles the different types of ice present

• How to work the ice w ith o u t damaging the ship

• The necessity fo r hull strength

• Reliable and adequate propulsion

6

' J W

1

Jv Z T 'ir

----------

2.3 USING THE TRAINING PACKAGE

This workbook and video have been designed to be used together. Both are equally

im portant. The video does not have to be shown in its entirety as it has been produced as

a series of modules, which can be viewed individually.

If you use the workbook as a training manual to run training sessions w ith the crew, you

should appoint a designated trainer (usually yourself or one of your Officers). The

workbook w ill help the Training Officer and crew to understand the im portant messages

in the video.

2.4

PREPARING FOR RUNNING TRAINING SESSIONS

Trainers should watch the video, read the workbook, and test themselves using the

questionnaire at the end of the book. They must be satisfied that they have familiarised

themselves w ith the correct procedures before commencing training sessions.

Watch the video again w ith other Officers and make sure everyone understands the

messages in the video. Discuss it together and make sure everyone agrees on which

safety procedures your crew needs to be trained to follow.

Make sure all the crew understand w hat the inform ation in the video means fo r your

specific type of vessel.

2.5

RUNNING THE TRAINING SESSIONS

Clear up any misconceptions at the beginning! First, explain to the group what the

purpose of the training session is and how they w ill benefit from it. Next, show them the

video, stopping it at the end of each of the main sections.

After each section, have a discussion about what the group has seen in that section. It is

im portant that the crew are always kept alert to the need for extra safety measures, and

how these extra measures should be put in place. Encourage the crew to think of the ship

as

Their Ship.

It w ill be helpful if they can share their experiences. A lot can be learned

from 'near misses' and real-life experiences.

3.

TH E DANGER OF ICE

3.1

THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF ICE

There are various types of sea ice, according to its stage

of development. W ithin each of the stages listed below,

there are also sub-types, depending on the internal

structure of the ice.

7

N ew Ice

Recently form ed ice composed of ice crystals that are only weakly frozen together (if at

all). They have a definite form only w hile they are afloat.

Nilas

A thin elastic crust of ice (up to 10 cm thick), easily bending on waves and swell; under

pressure it grow s in a pattern of interlocking 'fingers' (finger rafting).

Young Ice

Ice in the transition stage between nilas and first-year ice, 10-30 cm thick.

First-year Ice

Sea ice of not more than one W inter's grow th, developing from young ice, w ith a

thickness of 30 cm or greater.

Old Ice

Sea ice that has survived at least one Sum m er's melt. Its topographic features generally

are sm oother than first-year ice.

Ice form ation

There is a clear cycle of form ation and deform ation of sea ice. This process can be broken

down into four steps:

1. Formation

2. Growth

3. Deformation

4. Disintegration

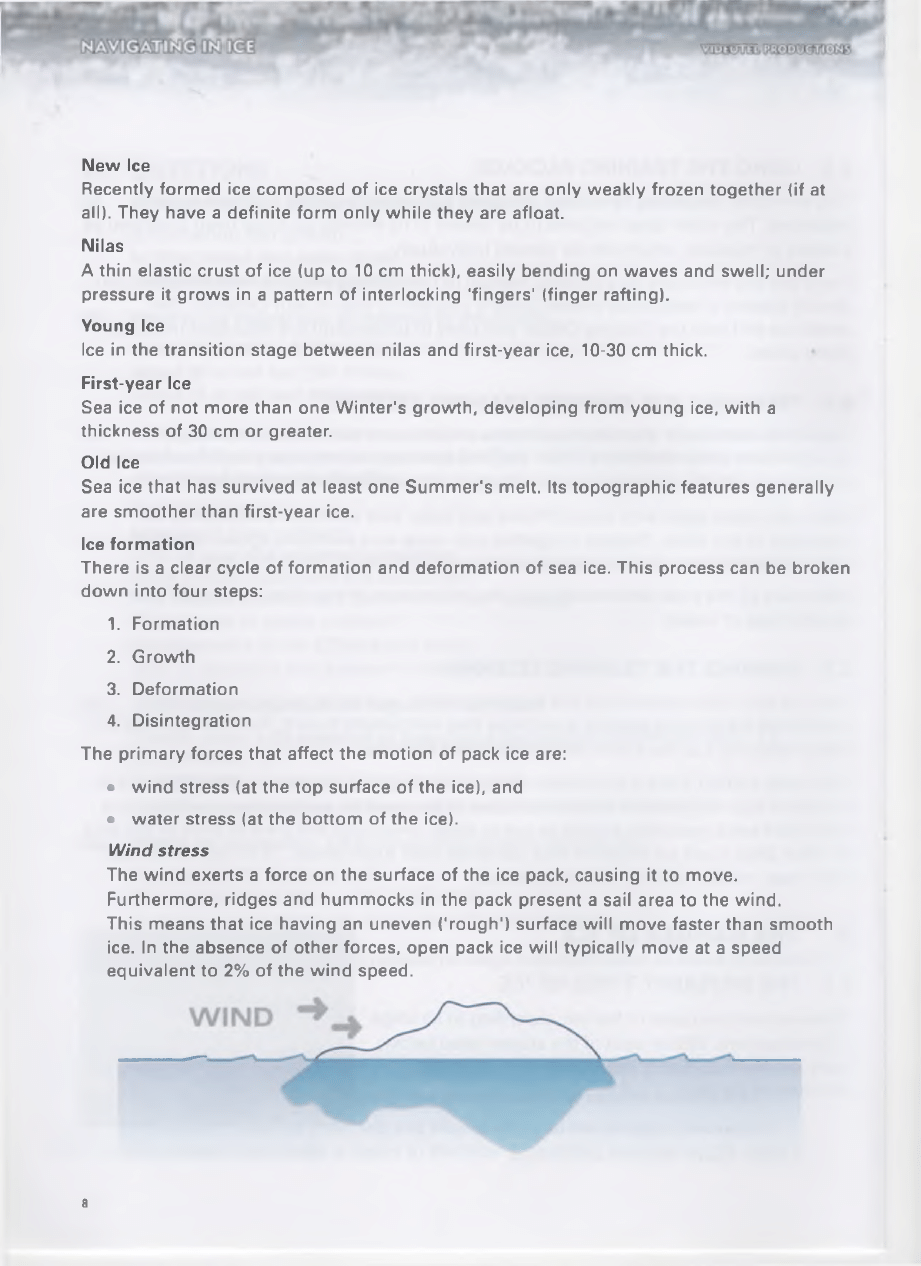

The prim ary forces that affect the m otion of pack ice are:

• w ind stress (at the top surface of the ice), and

• water stress (at the bottom of the ice).

W ind stress

The w ind exerts a force on the surface of the ice pack, causing it to move.

Furthermore, ridges and hum m ocks in the pack present a sail area to the wind.

This means that ice having an uneven ('rough') surface w ill move faster than smooth

ice. In the absence of other forces, open pack ice w ill typically move at a speed

equivalent to

2%

of the w ind speed.

8

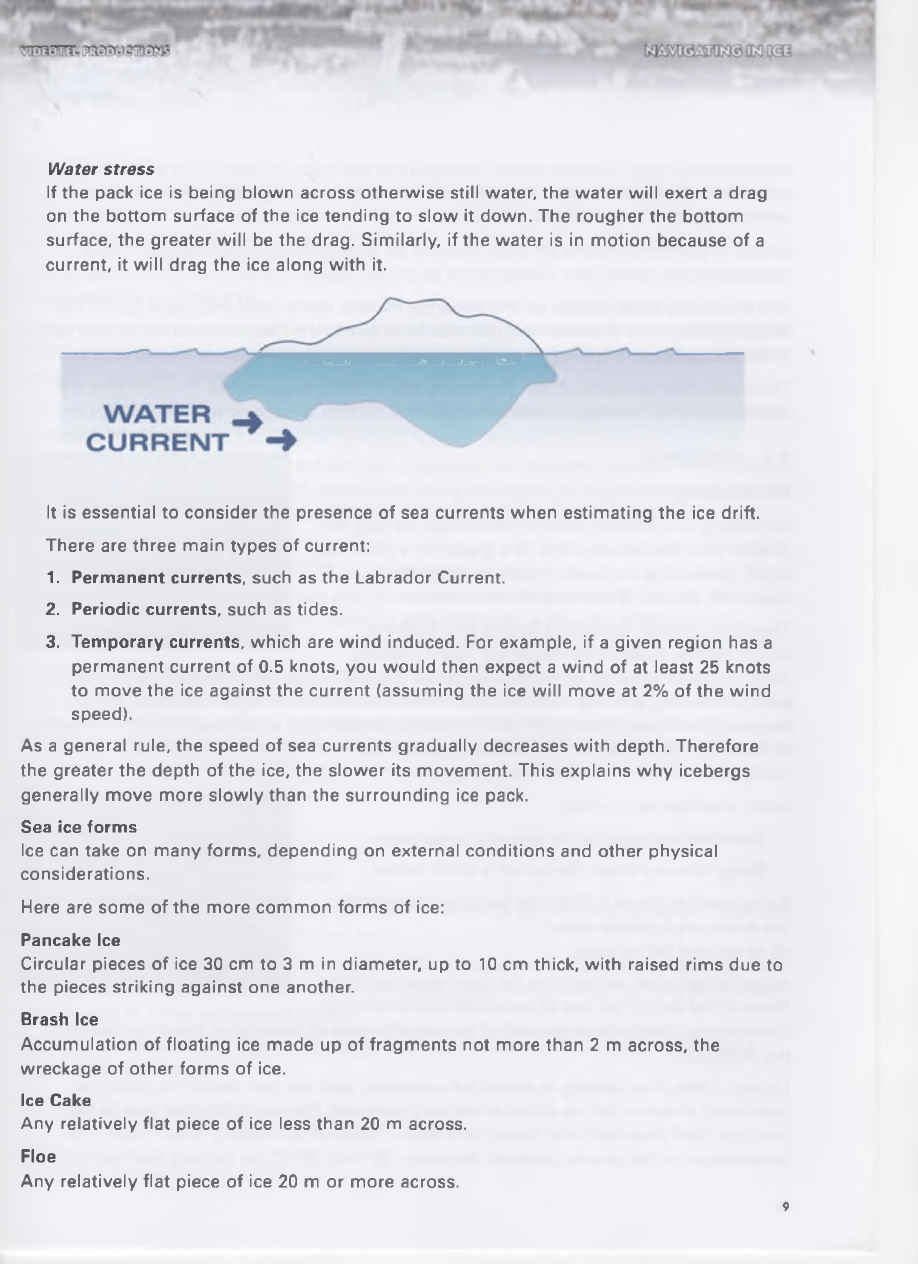

Water stress

If the pack ice is being blown across otherwise still water, the water w ill exert a drag

on the bottom surface of the ice tending to slow it down. The rougher the bottom

surface, the greater w ill be the drag. Similarly, if the w ater is in m otion because of a

current, it w ill drag the ice along w ith it.

It is essential to consider the presence of sea currents when estim ating the ice drift.

There are three main types of current:

1. Permanent currents, such as the Labrador Current.

2. Periodic currents, such as tides.

3. Temporary currents, which are w ind induced. For example, if a given region has a

permanent current of 0.5 knots, you w ould then expect a w ind of at least 25 knots

to move the ice against the current (assuming the ice w ill move at 2% of the w ind

speed).

As a general rule, the speed of sea currents gradually decreases w ith depth. Therefore

the greater the depth of the ice, the slower its movement. This explains w hy icebergs

generally move more slow ly than the surrounding ice pack.

Sea ice form s

Ice can take on many form s, depending on external conditions and other physical

considerations.

Here are some of the more com m on form s of ice:

Pancake Ice

Circular pieces of ice 30 cm to 3 m in diameter, up to 10 cm thick, w ith raised rim s due to

the pieces striking against one another.

Brash Ice

Accum ulation of floating ice made up of fragm ents not more than 2 m across, the

wreckage of other form s of ice.

Ice Cake

Any relatively flat piece of ice less than 20 m across.

Floe

Any relatively flat piece of ice 20 m or more across.

9

V ID E O.TiE L.P.R O D U C T IO N S

Fast Ice

Ice which form s and remains fast along the coast. Fast ice higher than 2 m above sea

level is called an ice shelf.

Except in sheltered waters, an even sheet of ice seldom form s im mediately. This is

because:

The thickening slush breaks up into separate masses under w ind and wave action, the

masses taking on a characteristic pancake form due to the fragm ents colliding w ith each

other.

The slush layer dampens down the waves, and if freezing continues, the pancakes w ill

adhere together, form ing a continuous sheet.

3.2

ICEBERGS

Pic of iceberg

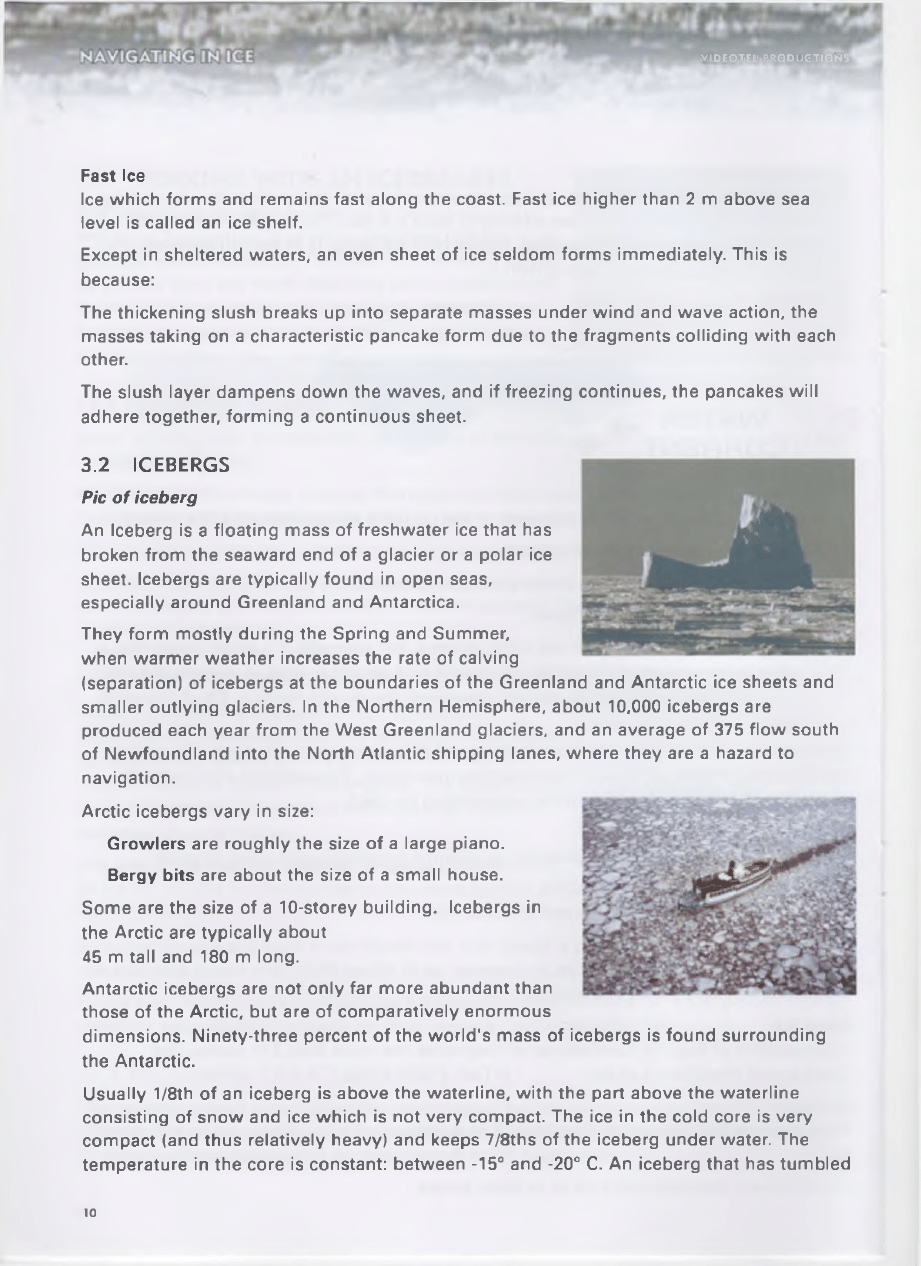

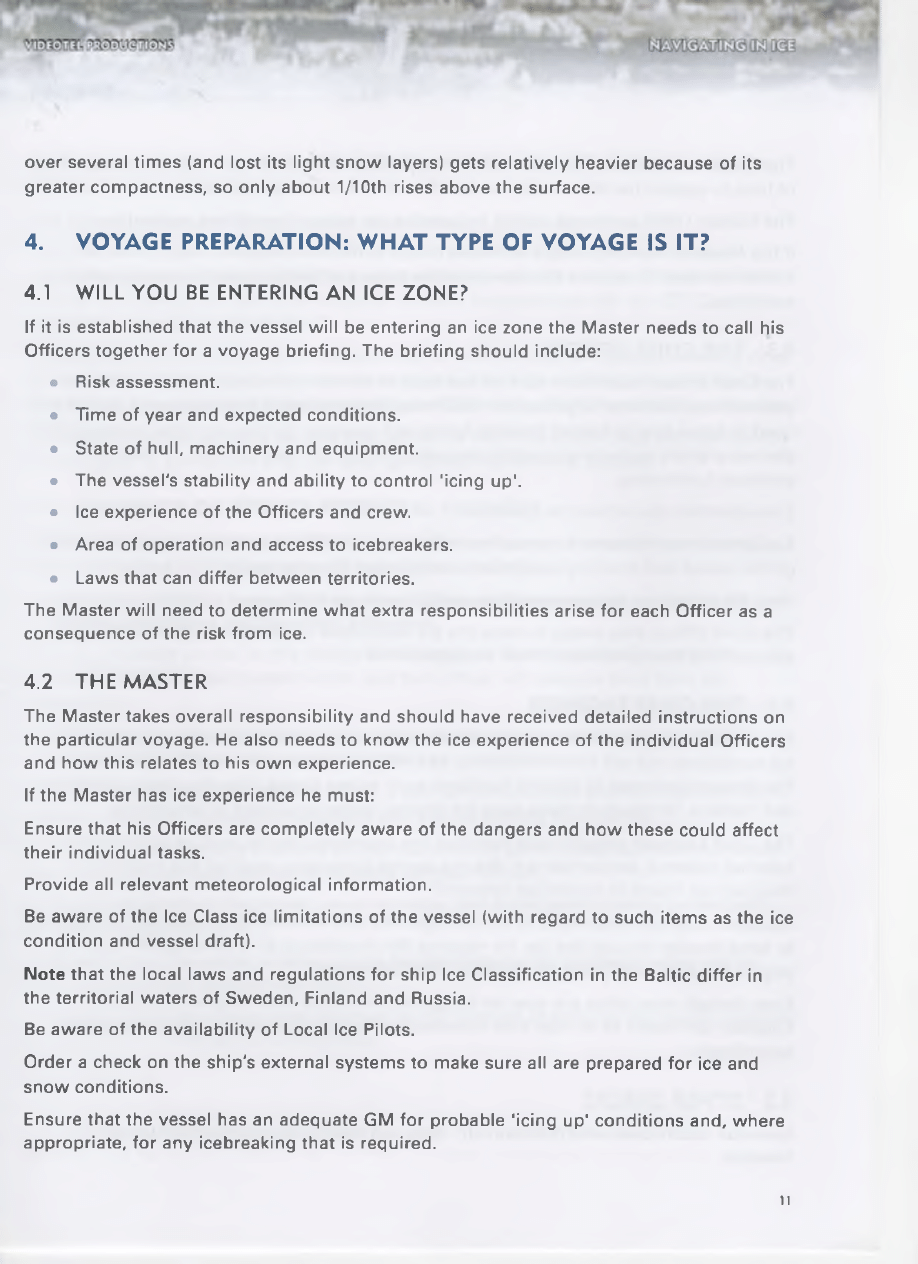

An Iceberg is a floating mass of freshwater ice that has

broken from the seaward end of a glacier or a polar ice

sheet. Icebergs are typically found in open seas,

especially around Greenland and Antarctica.

They form m ostly during the Spring and Summer,

when w arm er weather increases the rate of calving

(separation) of icebergs at the boundaries of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets and

sm aller outlying glaciers. In the Northern Hemisphere, about 10,000 icebergs are

produced each year from the West Greenland glaciers, and an average of 375 flo w south

o f Newfoundland into the North Atlantic shipping lanes, where they are a hazard to

navigation.

Arctic icebergs vary in size:

icebergs is found surrounding

G row lers are roughly the size of a large piano.

Bergy bits are about the size of a small house.

Some are the size of a 10-storey building. Icebergs in

the Arctic are typically about

45 m tall and 180 m long.

Antarctic icebergs are not only far more abundant than

those of the Arctic, but are of com paratively enorm ous

dimensions. Ninety-three percent of the w orld's mass of

the Antarctic.

Usually 1/8th of an iceberg is above the waterline, w ith the part above the waterline

consisting of snow and ice which is not very compact. The ice in the cold core is very

compact (and thus relatively heavy) and keeps 7/8ths of the iceberg under water. The

tem perature in the core is constant: between -15° and -20° C. An iceberg that has tum bled

10

over several tim es (and lost its light snow layers) gets relatively heavier because of its

greater compactness, so only about 1/10th rises above the surface.

4.

VOYAGE PREPARATION: WHAT TYPE OF VOYAGE IS IT?

4.1

WILL YOU BE ENTERING AN ICE ZONE?

If it is established that the vessel w ill be entering an ice zone the Master needs to call his

Officers together fo r a voyage briefing. The briefing should include:

• Risk assessment.

• Time of year and expected conditions.

• State of hull, m achinery and equipm ent.

• The vessel's stability and ability to control 'icing up'.

• Ice experience of the Officers and crew.

• Area of operation and access to icebreakers.

• Laws that can differ between territories.

The Master w ill need to determ ine what extra responsibilities arise fo r each Officer as a

consequence of the risk from ice.

4.2 THE MASTER

The Master takes overall responsibility and should have received detailed instructions on

the particular voyage. He also needs to know the ice experience of the individual Officers

and how this relates to his own experience.

If the Master has ice experience he must:

Ensure that his Officers are com pletely aware of the dangers and how these could affect

their individual tasks.

Provide all relevant m eteorological inform ation.

Be aware of the Ice Class ice lim itations of the vessel (with regard to such items as the ice

condition and vessel draft).

Note that the local laws and regulations fo r ship Ice Classification in the Baltic differ in

the territorial waters of Sweden, Finland and Russia.

Be aware of the availability of Local Ice Pilots.

Order a check on the ship's external systems to make sure all are prepared fo r ice and

snow conditions.

Ensure that the vessel has an adequate GM fo r probable 'icing up' conditions and, where

appropriate, fo r any icebreaking that is required.

n

The Master w ill need inform ation on the availability of icebreakers and an understanding

of how to captain his ship under the direction of the icebreaker captain.

The Master / Pilot exchange should include the ice precautions where applicable.

If the Master's own experience is lim ited then it is his own responsibility to take all

necessary steps to acquire the relevant knowledge and skills needed to remain in full

command.

4.3 THE CHIEF OFFICER

The Chief Officer m ust make sure he has read all the relevant docum entation and the

International M aritim e Organization (IMO) recom m endations fo r navigating in ice. He w ill

need to know how to ballast the ship for ice and m aintain its trim and how to ensure that

the many ship's systems exposed to tem perature change are protected so they w ill

continue functioning.

Consideration should also be given to:

Equipment m anufacturer's instructions w ith regard to W inter precautions (e.g. hydraulic

oil fo r cranes and m ooring equipm ent and the deck IG w ater seals).

How the vessel can be prepared to accept a tow by an icebreaker

The Chief Officer also needs to know the ice experience of his fe llo w Officers and be

assured that they understand their responsibilities.

4.4 THE CHIEF ENGINEER

The Chief Engineer's job is to make sure the ship's engines and systems are prepared for

ice conditions and w ill keep functioning as conditions worsen. He needs to be aware of

the dangers ice poses to specific functions such as sea chests, bow thrusters, propellers

and rudders. He needs to make sure the internal w ater circulation is functioning.

The Chief Engineer should make sure that the necessary checks, such as to the ship's

external systems, are carried out. Are the correct lubrication and fuel oils available so

they w ill not freeze or crystallise onboard?

He needs to know w hat levels of ice are expected and w hether the vessel w ill be required

to force its way through the ice. He requires this knowledge so that he can be sure the

engine has sufficient power to maintain m anoeuvrability.

Even though m ost ships are now on bridge control of the main engine, the Chief

Engineer still needs to be kept fu lly inform ed so he can allocate his lim ited manpower

accordingly.

4.5 OTHER CHECKS

Have the radars been well maintained? - they w ill need to run constantly to avoid

freezing.

12

In calm or relatively calm conditions radar is reliable fo r the detection of most icebergs

up to a range of between 12 and 15 miles, bergy bits from 6 to 12 miles and grow lers

from 1 to 3 miles, but it must be noted that even in these conditions some grow lers - of a

size that could seriously damage the vessel - may not be detected.

In rough conditions it is unsafe to rely on radar when sea clutter extends beyond 1 mile

for all but the detection of larger icebergs.

W hile radar and sonar - where fitted - are useful tools in looking fo r icebergs, they must

not be relied upon. Their signals can be refracted or absorbed by the conditions. Even the

angle of the iceberg may provide a weak signal.

Check that all other navigation equipm ent such as GPS or DGPS is functioning properly.

If sonar is fitted, it is im portant to m onitor the sea tem perature as this and salinity can

prevent the sonar signal from reaching a nearby object.

The ship w ill need to be in the right trim and ballast for ice navigation - it is im portant

that the propellers are kept below the ice level.

Some method of avoiding freezing condensation on bridge w indow s w ill need to be

used. Navigation light glasses can be smeared w ith Vaseline.

A check should be made on all de-icing arrangements.

5.

ICE CONDITION AND

M ETEO ROLO GICAL REPORTS

An essential part of the briefing is the meteorological

inform ation. All the Officers on board must be aware

not only of the types of ice conditions to be experienced,

but also the prevailing weather forecasts.

Countries that depend on m aintaining traffic lanes

during ice conditions have agencies that provide detailed

m eteorological reports together w ith substantial inform ation on ice conditions based on

m onitoring and analysis. Two key agencies are the Canadian Coast Guard

and the Finnish M aritim e A dm inistration

The Master is

recommended to make contact w ith such authorities at any tim e he is approaching the

national (Coastal State) waters.

The Canadian governm ent places a prem ium on studying and understanding the

dynamics of sea ice form ation and drift. The Ice and Marine Services Branch (IMSB), a

branch of the Meteorological Service of Canada, provides the Canadian Coast Guard

(CCG) and the United States Coast Guard, through partnership w ith the National Ice

Centre in W ashington, w ith accurate and tim e ly reports of sea ice conditions fo r the east

coast of Canada and the Canadian Arctic. Headquartered in Ottawa, the purpose o f the

IMSB is to im prove m aritim e navigation in Canadian and international waters and

provide crucial environm ental inform ation on pack ice in Canada’s northernm ost regions.

13

5.1

ICE NAVIGATION IN CANADIAN WATERS

Every ship of 100 tons gross tonnage or over, navigating in Canadian waters in which ice

may be encountered, is required to carry and make proper navigational use of the

Canadian Coast Guard publication Ice Navigation in Canadian Waters. The docum ent is in

tw o parts. Part I, 'Operating in Ice', pertains to operational considerations such as

com m unications, reporting, advisories, and icebreaker support. Part II, 'Additional

Inform ation fo r Navigation in Ice-Covered Waters', is educational in nature, w ith

inform ation provided to help fam iliarise watchkeepers w ith the Canadian ice

environm ent, navigation procedures in ice, and vessel performance in ice.

The docum ent is available in both official languages from any authorised Canadian

Hydrographic Service (CHS) Chart Dealer. The catalogue num ber is T31-73/1999E; the

ISBN num ber is 0-660-17873-7. A list of dealers is available on the CHS website at

http://www.charts.gc.ca/chs/en/.

Note: The 1999 version of Ice Navigation in Canadian W aters is the most current version

and there have been no amendments. As the inform ation does not vary from year to

year, the docum ent does not require frequent revisions. Canadian Hydrographic Services,

as distributor of the publication, w ill maintain a m ailing list fo r those who purchase the

publication, including those w ho were on the list of their previous distributor. Any

amendments w ill be sent out autom atically whenever required.

5.2

FINNISH MARITIME ADMINISTRATION

The Finnish M aritim e A dm inistration is the authority responsible fo r m aritim e safety,

W inter traffic assistance, fairw ay maintenance, VTS and pilotage, hydrographic charting

and the provision of ferry services to the archipelago com m unities. The Adm inistration

ensures that the basic operational conditions fo r merchant shipping and sea transport are

m aintained and continually im proved, taking into account safety and economic aspects,

as well as environm ental consequences. The activities aim to ensure safe and efficient

m erchant shipping, meeting both society's and customers' needs.

6.

SA FETY GEAR

As part of the check on the ship's external systems, safety gear should be inspected.

Are the searchlights and illum ination fu lly functioning?

Does the vessel have an adequate supply of one of the proprietary com mercial de-icing

compounds?

W ill the crew have access to adequate protective clothing, harnesses and safety lines?

Foul weather/high visib ility clothing: should be w orn on all external operations during

foul weather. If foul weather gear does not have built-in high visib ility sections, suitable

gear (such as armbands) should be w orn so those w orking can be seen more easily.

14

5.1

ICE NAVIGATION IN CANADIAN WATERS

Every ship of 100 tons gross tonnage or over, navigating in Canadian waters in which ice

may be encountered, is required to carry and make proper navigational use of the

Canadian Coast Guard publication Ice Navigation in Canadian Waters. The docum ent is in

tw o parts. Part I, 'Operating in Ice', pertains to operational considerations such as

com m unications, reporting, advisories, and icebreaker support. Part II, 'Additional

Inform ation fo r Navigation in Ice-Covered Waters', is educational in nature, with

inform ation provided to help fam iliarise watchkeepers w ith the Canadian ice

environm ent, navigation procedures in ice, and vessel performance in ice.

The docum ent is available in both official languages from any authorised Canadian

Hydrographic Service (CHS) Chart Dealer. The catalogue num ber is T31-73/1999E; the

ISBN num ber is 0-660-17873-7. A list of dealers is available on the CHS website at

http://www.charts.ac.ca/chs/en/.

Note: The 1999 version of Ice Navigation in Canadian W aters is the most current version

and there have been no amendments. As the inform ation does not vary from year to

year, the docum ent does not require frequent revisions. Canadian Hydrographic Services,

as distributor of the publication, w ill maintain a m ailing list fo r those w ho purchase the

publication, including those w ho were on the list of their previous distributor. Any

am endm ents w ill be sent out autom atically whenever required.

5.2

FINNISH MARITIME ADMINISTRATION

The Finnish M aritim e A dm inistration is the authority responsible fo r m aritim e safety,

W inter traffic assistance, fairw ay maintenance, VTS and pilotage, hydrographic charting

and the provision of ferry services to the archipelago com m unities. The Adm inistration

ensures that the basic operational conditions fo r m erchant shipping and sea transport are

m aintained and continually im proved, taking into account safety and economic aspects,

as w ell as environm ental consequences. The activities aim to ensure safe and efficient

merchant shipping, meeting both society's and customers' needs.

6.

SA FETY GEAR

As part of the check on the ship's external systems, safety gear should be inspected.

Are the searchlights and illum ination fu lly functioning?

Does the vessel have an adequate supply of one of the proprietary com mercial de-icing

compounds?

W ill the crew have access to adequate protective clothing, harnesses and safety lines?

Foul weather/high visib ility clothing: should be w orn on all external operations during

foul weather. If foul weather gear does not have built-in high visib ility sections, suitable

gear (such as armbands) should be w orn so those w orking can be seen more easily.

14

Safety harnesses and lines: approved safety harness should be provided to each person

equired to go out on deck. A dditional harnesses should be available on request if

equired. The provision of a harness to each person should ensure that any operation

vhich requires

]

harness to be w orn w ill be carried out by a person wearing one. This should norm ally

)e the m ost experienced person.

Under no circumstances should any type of w o rk requiring th e w earing of a safety

harness be carried ou t w ith o u t the harness.

A rsons w orking in extreme weather conditions should feel to ta lly safe at all times.

Protective clothing and equipm ent m ust be issued to all those involved. The protective

Nothing should be com fortable, well m aintained and not lead to an increase in other

isks. Training is needed in its use.

Baltic Sea

Bay and G ulf of Bothnia, G ulf of Finland

Finnish?Swedish Ice Class Rules (FSICR)

G ulf of Finland (Russian territorial waters)

Russian M aritim e Register (RMR) Ice Class Rules (Non-Arctic sea area

requirements)

Arctic Ocean

Barents, Kara, Laptev, East Siberian and Chukchi Seas

Russian M aritim e Register (RMR) Ice Class Rules

Beaufort Sea, Baffin Bay, etc

Canadian Arctic Shipping Pollution Prevention Rules (CASPPR)

Ohkotsk Sea

Russian M aritim e Register (RMR) Ice Class Rules (Non-Arctic Sea Area

Requirements)

7

.

WHAT IS TH E SHIP'S CAPABILITY?

7.1

WHO REQUIRES AN ICE CLASS?

Coastal States w ith seasonal or year-round ice-covered

)ceans and seas.

Specific oceans and sea areas as well as applicable Ice

Classes:

15

P, R O DUG

i

T

i

IO N S

7.2 TYPES OF SHIP

W hether the ship is capable of operating safely in ice is largely dependent on her Ice

Classification, which is established according to the agreed standards of national and

international authorities. Am ong the most respected are the marine adm inistrations of

Sweden and Finland together w ith all members of the International Association of

Classification Societies.

Icebreaker assistance is given to ships that meet the requirem ents of the local Icebreaker

Management concerning Ice Class and size. In W inter navigation, passenger ships must,

at a m inim um , meet the requirem ents of Ice Class 1B.

7.3

ICE CLASSIFICATION

Fundamentally, the philosophy behind Ice Class is the safety of the hull and essential

propulsion m achinery and w hether there is sufficient installed power for safe operation in

ice-covered waters.

Strengthening merchant vessels fo r ice navigation does not im ply that they can break or

force ice. They are not themselves icebreakers.

Ice Classes 1A, 1B and 1C can only navigate in waters w ith ice floes of respective

thicknesses. They cannot enter fast ice and can only fo llo w icebreakers in such

conditions.

7.4 CRITERIA FOR INSTALLED PROPULSION POWER

M inim um power fo r m aintaining ship speed in re-frozen (brash ice) fairw ay navigation

channel (Finnish-Swedish Rules)

M axim um power fo r prevention of hull and propulsion system damage (Canadian Rules)

The Propulsion Requirements of any of the Members of the International Association of

Classification Societies.

7.5 WHAT ARE THE FINNISH-SWEDISH ICE CLASSES?

Ice Class 1AS

This is fo r ships built fo r severe ice conditions where ice floes of 1 m thickness are

anticipated. Their hulls are strengthened and are designed to be able to crack the ice.

Propeller and shafting arrangements are designed fo r im pact loads from ice pieces.

Installed propulsion power is suitable fo r maintenance of 5 knots ahead speed.

Ice Class 1A

This is fo r severe ice conditions w ith anticipated ice floes 0.8m thick.

Ice Class 1B

This is for medium ice conditions w ith anticipated ice floes 0.6m thick.

16

Ice Class 1C

This is for light conditions w ith ice floes 0.4m thick.

Class II

Class III

Ships w anting to enter ice zones such as the Baltic, where policing of Ice Class

Regulations is strict, w ill only be allowed in if their Ice Class meets the conditions they

are likely to encounter or the services needed fo r their safe navigation are available.

In the Baltic these services are free, whereas rescue is not. Ships w ith no Ice Class may

not be allowed to enter.

7.6 CERTIFICATES

Proof of the awarded Ice Class comes in the form of a Certificate and this needs to be

readily available to show to local authorities. If the local authorities are dissatisfied, they

have the power to prevent ships sailing into ice-infested waters.

The Finnish authorities have notified the classification societies that Ice Classifications are

now also dependent on the International Convention on Load Lines. The m inim um

engine output fo r which the notation for navigation in ice has been assigned is the

m inim um required power. This is because several ships which were ill-equipped fo r ice

and manned by inexperienced crews were trapped and damaged in the Baltic in

2002/2003, when the weather was particularly bad, requiring considerable assistance

from the local rescue services.

The Master must therefore make sure that the Certificates, load lines markings and Ice

Class lines of the ship com ply w ith the regulations of the territorial waters in which he

intends to sail his ship. In the Baltic, ships may be in conflict w ith the Finnish Port State

Control if they show a Load Line Certificate that does not com ply w ith the Ice Class Marks

and the draught.

7.7

ENGINE ROOM MACHINERY (PROPULSION)

The ship's engine output means the m axim um power which the engine can sustain

continuously. If the engine output has been lim ited by technical measures or restricted by

regulations concerning the ship, the

lim ited

output power is taken to be the engine output

value.

An icebreaker can refuse to assist a ship w ith equipm ent that is not operational before

the assistance starts, or if the hull, engine power, equipm ent or manning is such that

there is cause to believe that navigation in ice endangers the safety of the ship or that the

ice-going characteristics of the ship are inferior to that norm ally required of ships of the

same Ice Class.

The engine power is governed by the intended role of the ship and w hether she is

intended to be able to force her way through ice and at w hat thickness.

17

7.8 TRIM AND STABILITY

The draught must be kept between the load line and the ballast line during navigation

in ice.

The ship m ust be ballasted and trim m ed so that the propeller is com pletely submerged

and is as deep as possible. Tanks should be no more than 90% full to accommodate

expansion if it freezes.

The vessel must have an adequate GM to allow fo r (a) the slack w ater in her ballast/fresh

water tanks, (b) the loss of GM due to 'icing up' of the upper works, (c) the virtual loss of

GM experienced when breaking ice floes (grounding).

8.

WHAT TO LOOK O UT FOR:

KEEPING A KEEN WATCH

As always, a proper lookout should be maintained, but if

an ice zone is to be encountered then the risk of meeting

obstacles is significantly raised. Picking a safe passage

through fields of ice, often shed by large icebergs, is a

cautious business. This means that the Officer of the

Watch should be aware of the different types of ice floes

and icebergs he is likely to encounter. He should be

fam iliar w ith the identification of ice, its type and form ation, sea ice, glacier ice, icebergs,

detection of pack ice, ice floes, and other ice types and relevant terms.

Every opportunity should be taken in clear weather to study the radar returns from all the

different types/concentrations of sea ice to assist the watchkeepers in their assessment in

reduced visibility.

A careful lookout must therefore be m aintained at m axim um levels at all times. Further,

constant vigilance m ust be paid to all ship systems such as radar, sonar and radio. The

bridge crew must be kept on full alert at all times.

When navigating in ice the Chief Mate w ill usually assist the Master in conning the vessel

from the bridge.

One mate and an able seaman may be posted (on the bow) externally as lookouts to

assist in the ice conning.

As navigating in ice may be a tim e-consum ing process, optim um use should be made of

the bridge team and all personnel on board and rest/work hours requirem ents should be

observed.

8.1 ICEBERG MONITORING

Icebergs can be difficu lt to see, so great caution is needed. They can be concealed in fog,

or blend in w ith the grey sky and sea. They can appear small above the surface but be

large beneath it. You may be underway at night tim e or during the long Arctic Winter.

18

*

n

L

igating

ODOQSB

British Meteorological Routing Charts are available to show the most likely ice zones and

iceberg routes. These help decide when to set up observation routines as the zones are

approached. There are many other agencies providing updated inform ation on ice and

sea conditions and the proxim ity of icebergs.

The United States and Canadian Coast Guards, the Finnish M aritim e A u th o rity and the

European Space Agency, among m any others, provide advice and the latest inform ation

on websites and radio com m unications. Their services are invaluable to mariners and are

very often free.

These authorities gather inform ation by satellite, tracking aircraft and other sensors, but

also rely on first-hand sightings from shipping. W henever an iceberg is spotted its

position, approxim ate size, speed and course m ust be relayed to the relevant authority

w ith in the area. This maintains up-to-date databases and helps other ships.

In the Arctic many icebergs originate in the glaciers of Greenland. As they break they

float south in the East Greenland current carrying them beyond Cape Farvel on the 60th

parallel and tow ards Newfoundland and the East Coast of North America.

Many more come from the glaciers of Baffin Bay and it is estimated that as many as

40,000 icebergs float here at any one tim e. Many run aground locally and go no further

but significant numbers slow ly d rift south w ith the Canadian and Labrador currents to

pose threats to shipping lanes south of the 48th parallel o ff Newfoundland. The numbers

vary each year but average over 200 per year, although they can reach up to 900. Usually

they float no further south than the 42nd parallel.

The Antarctic ice continent is much larger and deeper than the ice cap of the North Pole.

The ice zone around it spreads north to between the 58th and 62nd parallels and icebergs

are possible anywhere w ith in this area especially in the glacial areas of the Weddell and

Ross Seas.

However, it should be noted that it is not uncom m on to detect bergs well north of these

latitudes and they have been located north of the 40th Parallel in the South Atlantic.

An alert lookout is not restricted to using your eyes:

Listening for the sounds of breaking icebergs is im portant, as is the detection of waves

breaking over them.

The absence of sea in a fresh breeze could indicate a large object to w indw ard.

Thunderous sounds but no storm could suggest an iceberg breaking up.

Growlers and small pieces of ice could indicate a disintegrating iceberg.

If, on a dark night at slow speed ahead, you can hear the sound of breakers where no

land is expected, watch out fo r a large object to be avoided.

19

8.2

PACK ICE

Pack ice is easier to look out for, but it can still be difficu lt to see in certain conditions.

Pale sun, fog and m ist can create ice 'blink'. W ith blue skies, ice blink can appear as a

lum inous yellow haze on the horizon in the direction of the ice. W ith an overcast sky it

can appear as a w hite glare on the clouds.

Sure signs of the approach of an ice pack are the abrupt sm oothing of the sea and the

gradual lessening of the ordinary ocean swell. So too are small ice floes and certain types

of w ild life - including seals, walruses and birds.

9.

WHAT TO DO WHEN

APPROACHING ICE

9.1

WHY FOLLOWING PROCEDURES

IS IMPORTANT

As a general rule, ice is an obstacle. It is very strong and

com m ands great respect from mariners w ho must

understand its latent power and strength.

When ice is confirm ed the Master must be informed and his presence on the bridge is

now necessary. He m ust make a report to the local authorities. This also applies if the

vessel is in an ice zone and an iceberg is sighted.

The Master advises the authorities of the type of ice, its position, and the tim e and date of

the initial sighting. He must also pass on inform ation on air and sea temperature if below

freezing. The authorities w ill need to know the direction and force of the w ind and any ice

accum ulation on the ship and the exact position of the ship.

The Master must advise the Chief Engineer that they are approaching

ice as the vessel's

speed w ill have to be reduced.

One mate is required in the wheelhouse plotting continuous positions.

9.2 SAFETY CHECKS

Checks are crucial because the Master does not w ant to risk the ship in frozen sea until he

knows the precise conditions.

• W hat type of ice is it?

• How thick is it?

• How much is it moving?

The vessel's trim and ballast must be such that the propeller is kept below the water

surface.

20

All tanks should be no more than 90% full because if they are fu ll and freeze solid, they

could split.

Sea w ater strainers and filters m ust be kept clean.

The crew must have the appropriate w orking/survival clothing fo r the conditions. A

poorly equipped sailor w ill not last long and w ill not be able to carry out his duties or

survive emergency/abandon ship stations. Am bient temperatures can be -20° C, w ith a

w ind chill - the equivalent of -30° C.

Ice build-up on the ship's superstructure must be m onitored at all tim es to ensure it does

not become excessive. In gale or storm conditions where the am bient tem peratures are

below zero, the waves and spray can build up and severely affect the stability of the ship.

The Chief Engineer needs to be sure that, w hile the ship has an Ice Class and can handle

the ice, once in the ice, the ship can keep going and not become trapped.

9.3

ELIMINATE OR REDUCE POTENTIAL HAZARDS

Circumstances can change rapidly in ice zones. Temperatures can suddenly drop and

water that is free one m inute can very quickly become solid.

M axim um vigilance is needed fro m every Officer and crew m em ber to constantly

m o nito r conditions and th e ship's behaviour.

Officers on watch can be on the bridge fo r a long time. Even once the ice watch is

secured som ebody has to stand watch and that Officer w ill become tired from ice

operations.

Consideration should be given to ‘doubling up1 the bridge watchkeepers w ith the

M aster/ Chief Officer accompanied by the 2nd / 3rd Officer.

Never underestimate the hardness of ice. It can vary in thickness and the floes can be of

different sizes and therefore strengths. It can also be m oving in a current.

If ridging or hum m ocking is severe an alternative entry point should be found as ridged

ice may be far too deep and could severely damage the hull.

If the ice has a definite beginning, or an ice edge, that is the point of entry to the pack.

Always try and enter at 90°.

It is preferable, if possible, to enter on the leeward side as the w indw ard edge w ill be

more compact w ith greater wave action.

The Chief Engineer must be kept inform ed of the m om ent of entry so that he can respond

to demands fo r extra power immediately.

21

10. HOW TO ENSURE SAFE PASSAGE

10.1 SHIP-HANDLING RULES

It is vitally im portant to maintain freedom of manoeuvre.

The three basic ship-handling rules are:

• Keep m oving, even if very slowly.

• Try to w ork

with

the ice not against it.

• Excessive speed leads to ship damage.

In ice zones lookouts and radar operators must be

particularly alert and m ust reduce speed w ithout

hesitation if an iceberg is sighted w ith o u t w arning, or

signs warn that one may be close.

10.2 COMMUNICATION WITH ENGINE ROOM

Regular com m unications w ith the engine room should be m aintained at all tim es so that

the Chief Engineer and his staff are aware of the prevailing conditions and are ready to

increase and reduce power when necessary.

The Chief Engineer m ust ensure that the cooling water sea chests are working at

optim um efficiency.

10.3 ENTERING THE ICE

Entry into the ice m ust be at slow speed. Depending on conditions, it should then be

increased slow ly to maintain headway and control.

In an area of light d rift ice, lookouts should watch fo r large floes or fragm ents of old hard

ice that pose significant threats. These must be avoided. At night in these conditions all

searchlights must be used, w ith the helmsman in place ready to take evasive action.

If possible avoid large floes as they may have underwater spurs. If avoidance is

impossible, it

m a y

be possible to push it out of the way. Once it starts to swing to one

side, reduce power and allow it to pass clear.

If collision is unavoidable then hit the ice as squarely as possible. Do not hit it w ith a

glancing blow as this could damage bow plates and swing the ship so as to bring the

stern onto the floe and damage the propeller and rudder.

10.4 USE OF ENGINES AND RUDDER

The best speed to maintain depends on tw o factors:

1. The vessel's tonnage.

2. The density of the ice.

22

If concentrations of ice vary, so must the ship's speed. Faster speeds in light ice could

mean striking heavier ice w ith a greater way of the ship and cause damage. If a sudden

heavy section of ice is encountered and stops the ship, the engines must be prepared to

go full astern at any time.

Going astern must be done w ith great caution as the propeller and rudder are the most

vulnerable parts of the ship.

To go astern, the rudder must be put to amidships w ith the engines turning slow ly ahead.

This washes the ice astern clear. Crewmen should confirm that the stern is clear before

the ship can come astern.

Violent rudder movements should only be considered in emergencies as they may swing

the stern into the ice.

Frequent use of the rudder to the hard over positions can slow the vessel w ith o u t loss of

steerage way. However, too much rudder can bring the vessel to a complete stop, which

is very dangerous in freezing conditions.

10.5 RAMMING AND BACKING

Ramming the ice is very dangerous and acceptable only if the ship is in danger, and

forcing a passage through to open water or less heavy ice is the only alternative. It

requires great caution and you need to be certain that the bow w ill crack the ice rather

than the ice damage the ship.

The method is to ram the ice to break it by sheer impact and w eight and then reverse and

try again. This action needs to be repeated until access to clear water is made. If progress

is slight and the channel created is not considerably w ider than the beam, then the

procedure should be stopped. Extensive damage could prove fatal even if the ship

reached clear water.

Avoid getting trapped in the ice.

10.6 FREEING A TRAPPED SHIP

When a ship becomes trapped, an icebreaker w ill usually be required. However, there are

a few methods the ship can try to free itself.

If the propellers are not com pletely embedded the ship can try going full ahead and then

full astern, alternating full helm in both directions, which may swing the ship and loosen

the ice grip to allow m ovem ent ahead.

Shifting the ballast from side to side may also help, and the ship's anchor chains and

winches can be used.

23

11. WORKING W ITH AN ICEBREAKER

The need fo r icebreaker assistance is becoming more

and more frequent as interest in operating tankers in ice-

infested waters increases. This trend could well increase

as exports from the North Baltic are set to double w ithin

the next 5 years and there is increasing interest in the

large oil and gas reserves in the Arctic and Far Eastern

areas of Russia.

11.1 COMMUNICATIONS

When w orking w ith an icebreaker, the Master of the icebreaker is in overall command and

directs all operations.

All Officers on the bridge m ust be thoroughly fam iliar w ith icebreaker signals as shown in

the International Code of Signals.

All instructions from the icebreaker m ust be acknowledged and executed immediately.

The ship must continuously watch and listen fo r icebreaker's signals and fo r those of

other ships that may be being sim ultaneously assisted. The agreed VHF channel m ust be

continuously m onitored.

11.2 HOW THE ICEBREAKER BREAKS THE ICE

Modern icebreakers are built to the highest Ice

Classification. Icebreaker hulls are designed to withstand

the immense pressure of ice and shaped so they can

crack it, w ith the power of the engines. The shape of the

hull is such that it can create a wide channel in the ice

fo r larger ships to follow.

The size of the channel depends largely on the thickness

of the ice. In thin ice the icebreaker can move quickly and create a large channel by using

the stern wave.

In thicker ice she w ill push more slow ly and may create a channel about a third w ider

than her beam.

It may also be necessary to attack the ice in particular form ations. A 'herring-bone attack'

creates a large channel suitable fo r most vessels - but it can take time.

11.3 FOLLOWING THE ICEBREAKER'S PATH

The escorted vessel m ust fo llo w the path cleared by the icebreaker. It is im portant to

maintain the same speed as the icebreaker, which may be 6-7 knots in open ice, but less

in thicker concentrations and no more than 5 knots in close ice.

24

It is often better to travel in convoy and in this case the icebreaker Master w ill issue

instructions on the order of ships and the m inim um distance between them. The

m inim um distance is that required fo r an emergency stop w ith the engines full astern.

However, the distance may be less if the pressure in the ice pack is so great that the

channel w ill not remain open fo r long enough fo r the ship to pass.

In this case, the icebreaker may need to hit the ice at speed to crack it and force a path.

The vessels follow ing must then proceed w ith o u t delay before the gap closes again.

All signals m ust be im m ediately and precisely repeated to the ship behind and passed

down the line.

11.4 EMERGENCIES

The icebreaker decides when a ship needs to be taken into tow. The ship must be

prepared w ith rigged tow ing gear at all tim es in case tow ing is necessary. A ship that is

being towed by an icebreaker m ust use its engines only in accordance w ith the orders

given by the icebreaker.

Any damage or suspected damage must be reported to the icebreaker immediately.

If the assisted vessel stops because of ice conditions and the searchlight has been in use,

it must be switched o ff as long as the ship is stationary.

If the ice conditions deteriorate during the icebreaker assistance, tow in g m ight be the

only safe and prudent way to continue the assistance. Towing should be done in the

norm al manner, using (so-called) fo rk to w in g . In this case, the vessel's bow is taken

inside the tow ing fork and tw o cables from the icebreaker are attached to the assisted

vessel's bitts, which are designed to w ithstand the stresses of tow ing.

If trouble cannot be avoided, it is often better to ram the ice and embed the bow than

collide w ith another ship or the icebreaker.

Ramming the ice is also the best option if there is any danger of the propeller and rudder

hitting the ice.

When a ship is trapped, the engine should be kept running and the propeller turning,

if possible, to prevent ice form ing at the stern.

12. TH E CONSEQUENCES OF

POOR SEAMANSHIP

• Loss of ship and crew stranding

• Drifting w ith the ice and going aground

• Damage to hull, rudder and propeller

• Increased wear to engine and machinery

• Towing costs, repairs and salvage

13. QUESTIONS

Q1.

W hat are the tw o prim ary forces th a t affect the m otion of pack ice?

a. Formation and grow th

b. W ind stress and water stress

c. Deform ation and disintegration

02.

W hat is the typical size of icebergs in the Arctic?

About 45 m tall and 180 m long.

About 30 m tall and 250 m long.

About 75 m tall and 100 m long.

Q3.

If it is established th a t th e vessel w ill be entering an ice zone the M aster needs to

call his Officers tog e the r fo r a voyage briefing. Identify six item s th a t need to be

determ ined during the briefing.

Risk assessment

Num ber of crew onboard

Time of year and expected conditions

State of hull, m achinery and equipm ent

The Vessel's stability and ability to control 'icing up'

The am ount of stores onboard

Ice experience of the Officers and crew

Area of operation and access to icebreakers

Q4.

W hich areas/organisations require an Ice Class?

Coastal states w ith seasonal or year-round ice-covered oceans and seas. T/F

The UK MCA. T/F

The IMO. T/F

Specific oceans and sea areas as w ell as applicable Ice Classes. T/F

Q5.

During ice navigation, w h a t should the vessel's draught be?

As agreed w ith the local authorities.

Between the load line and the ballast line.

In respect of the thickness of the ice to be encountered.

Q6.

In calm conditions, radar is reliable fo r large icebergs (dow n to small growlers) at

w h a t ranges?

From up to 5 to 10 miles.

From up to 10 to 15 miles.

From up to 15 to 20 miles.

Q7.

When ice is confirm ed, identify fo u r procedures th a t need to be follow ed.

The Master must be inform ed and his presence on the

bridge is necessary.

The Master must make a report to the local authorities, and this w ould apply if

26

the vessel was in an ice zone and iceberg had been sighted.

All crew must be awoken and a m uster taken.

The Master must advise the Chief Engineer that they are approaching ice as the

vessel's speed w ill have to be reduced.

All crew must be issued w ith special rations.

The helmsman should be steering from the bridge, 1 hour on and 1 hour off,

because of the cold and the am ount of m anoeuvring necessary.

Q8.

W hy should all tanks be 90% full?

To allow air to circulate.

To prevent friction.

Because if they were full and froze solid, they could split.

Q9.

Identify th e three basic ship-handling rules.

Keep m oving, even if very slow ly

Stop if necessary

Always work against the ice

Try to w ork w ith the ice not against it

Excessive speed leads to ship damage

Q10. If collision is unavoidable how should the ice be hit?

As squarely as possible.

W ith a glancing blow.

At an angle of 45°.

Q11. The best speed to m aintain depends on w h a t tw o factors?

The vessel's course and w ind speed.

The vessel's tonnage and the density of the ice.

The weather conditions and the vessel's tonnage.

Q12. When the escorted vessel is fo llo w in g a path cleared by an icebreaker it is

im p o rta n t to m aintain th e same speed as the icebreaker. W hat is th is speed likely

to be?

4-5 knots

5-6 knots

6-7 knots

Q13. If th e ice conditions deteriorate during th e icebreaker assistance w h a t m ig h t be

the only safe and prudent w ay to continue the assistance?

Towing in the normal manner, using the so-called fork tow ing.

Towing using a single line.

Stop and assess the conditions.

Q14. Identify fo u r consequences of poor seamanship.

27

p.RODuemioNS:

14. LEGISLATION

Local regulations of authorities such as the US and Canadian Coast Guards, and the

Finnish M aritim e Authority.

IMO

28

* -

NAVilG^ATiING

QDOOC3S

ANSWERS TO T E S T QUESTIONS

1.

b

2.

a

3.

a,c,d,e,g,h

4.

a and d true

5.

b

6.

c

7.

a,b,d,f

8.

c

9.

a,d,e

10.

a

11.

b

12.

c

13.

a

29

m

V IP E O T E L

V I D E O T E L P R O D U C T I O N S

8 4 N E W M A N S T R E E T

L O N D O N W I T 3 E U , U K

T : + 4 4 ( 0 ) 2 0 7 2 9 9 1 8 0 0

F: + 4 4 ( 0 ) 2 0 7 2 9 9 1 8 1 8

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

VA 023 1 Navigation in Ice, STW

I DD18 F01 Brdige check list navigation in ice

I-DD16-F01 Bridge check list navigation in heavy weather or, AM SZCZECIN, INSPEKCJE MORSKIE, Inspekc

I DD16 F01 Bridge check list navigation in heavy weather or

Nora Roberts Concannon Sisters Trilogy 02 Born In Ice

Navigation in heavy weather

ROBERTS, Nora BORN IN 02 Born In Ice

Concannon Sisters 02 Born In Ice

Lokki T , Gron M , Savioja L , Takala T A Case Study of Auditory Navigation in Virtual Acoustic Env

Monocular SLAM–Based Navigation for Autonomous Micro Helicopters in GPS Denied Environments

3 5E D&D Adventure 09 Tower in the Ice

Diana Castilleja Ice Cream in the Snow (pdf)(1)

Victor Appleton Tom Swift in the Caves of Ice

One Night 2 One Night in the Ice Storm Noelle Adams

An Assessment of the Efficacy and Safety of CROSS Technique with 100% TCA in the Management of Ice P

Tom Swift in the Caves of Ice by Victor Appleton

terrestrial foraging by polar bears during ice free period in hudson bay

Education in Poland

więcej podobnych podstron