14. Empathy and Direct Discourse

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives

Perspectives

Perspectives

Perspectives

SUSUMU KUNO

SUSUMU KUNO

SUSUMU KUNO

SUSUMU KUNO

1

1

1

1 Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

This paper discusses two functional perspectives - the

EMPATHY

PERSPECTIVE

and the

DIRECT

DISCOURSE

PERSPECTIVE

- that are indispensable for the study of syntactic phenomena in natural language. These

perspectives, like other discourse-based perspectives, such as

PRESUPPOSITION

and

THEME

/

RHEME

, that

interact closely with syntactic constructions, help us distinguish what is non-syntactic from what is

syntactic and guard us from mistakenly identifying as syntactic the effects of non-syntactic factors on

the construction under examination.

2 The Empathy Perspective

2 The Empathy Perspective

2 The Empathy Perspective

2 The Empathy Perspective

2.1 The Empathy Principles

2.1 The Empathy Principles

2.1 The Empathy Principles

2.1 The Empathy Principles

Assume that John and Bill, who share a dormitory suite, had an argument, and John ended up hitting

Bill. A speaker, observing this event, can report it to a third party by uttering (1a-c) or (2a-b), but not

(2c):

(1) a. Then John hit Bill.

b. Then John

i

hit his

i

roommate.

c. Then Bill

j

's roommate hit him

j

.

(2) a. Then Bill was hit by John.

b. Then Billj was hit by hisj roommate.

c. ??/*Then John

i

's roommate was hit by him

i

.

These sentences are identical in their logical content, but it is generally felt that they are different

with respect to the speaker's attitude toward the event, or toward the participants of the event. It is

intuitively felt that in (1b), the speaker has taken a perspective that places him/her closer to John than

to Bill, whereas in (1c), the speaker is closer to Bill than to John. The notion of

EMPATHY

was proposed

in Kuno (1975), Kuno and Kaburaki (1977), and Kuno (1987) to formalize this intuitive feeling and

thus to account for the unacceptability of (2c) and many other related phenomena.

The following definitions, assumptions, and hypotheses are in order:

(3) a. E

MPATHY

: Empathy is the speaker's identification, which may vary in degree, with a

person/thing that participates in the event or state that he/she describes in a sentence.

b. Degree of Empathy: The degree of the speaker's empathy with x, E(x), ranges from 0 to 1,

with E(x) = 1 signifying his/her total identification with x and E(x) = 0 signifying a total lack of

identification.

Theoretical Linguistics

»

Pragmatics

discourse

10.1111/b.9780631225485.2005.00016.x

Subject

Subject

Subject

Subject

Key

Key

Key

Key-

-

-

-Topics

Topics

Topics

Topics

DOI:

DOI:

DOI:

DOI:

Page 1 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Blac...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

c. D

ESCRIPTOR

E

MPATHY

H

IERARCHY

: Given descriptor x (e.g.

John

) and another descriptor f(x) that

is dependent upon x (e.g.

John's roommate

), the speaker's empathy with x is greater than that

with f(x): E(x) > E(f(x))

d. S

URFACE

S

TRUCTURE

E

MPATHY

H

IERARCHY

: It is easier for the speaker to empathize with the

referent of the subject than with that of any other NP in the sentence: E(subject) > E(other NPs)

e. T

OPIC

E

MPATHY

H

IERARCHY

: Given an event or state that involves A and B such that A is

coreferential with the topic of the present discourse and B is not, it is easier for the speaker to

empathize with A than with B: E(topic) [] E(nontopic)

f. S

PEECH

A

CT

E

MPATHY

H

IERARCHY

: The speaker cannot empathize with someone else more than

with himself/herself:

E(speaker) > E(others)

g. H

UMANNESS

E

MPATHY

H

IERARCHY

: It is more difficult for the speaker to empathize with a non-

human animate object than with a human, and more difficult to empathize with an inanimate

object than with an animate object:

E(human) > E(non-human animate) > E(inanimate) h. T

RANSITIVITY

OF

E

MPATHY

R

ELATIONSHIPS

:

Empathy relationships are transitive.

i. B

AN

ON

C

ONFLICTING

E

MPATHY

F

OCI

: A single sentence cannot contain logical conflicts in

empathy relationships.

j. M

ARKEDNESS

P

RINCIPLE

FOR

D

ISCOURSE

R

ULE

V

IOLATIONS

: Sentences that involve marked (or

intentional) violations of discourse principles are unacceptable. On the other hand, sentences

that involve unmarked (or unintentional) violations of discourse principles go unpenalized and

are acceptable.

The Descriptor Empathy Hierarchy (EH) states that, given two descriptors

John

and

John's

/

his

roommate

in (1b), the speaker's empathy with John is greater than that with his roommate. The

Surface Structure EH says that, given

John

in subject position and

his roommate

in non-subject

position, the speaker's empathy with John is greater than that with his roommate. Since these two

empathy relationships are consistent, the sentence does not violate the Ban on Conflicting Empathy

Foci, hence the acceptability of the sentence. I will schematize the above two relationships and the

resulting conclusion in the following way:

(4) (1b) Then John

i

hit his

i

roommate.

Descriptor EH E(John

i

) > E(his

i

roommate=Bill)

Surface Structure EH E(subj=Johni) > E(non-subj=hisi roommate=Bill)

E(John) > E(Bill) [no conflict]

The acceptability of (1c), on the other hand, is accounted for in the following fashion. According to

the Descriptor EH, the use of the descriptor

Bill

to refer to Bill, and of

Bill's roommate

to refer to John

shows that the speaker's empathy with Bill is greater than that with John. However, the Surface

Structure EH says that the speaker's empathy with the referent of the subject (i.e.

Bill's roommate

=

John) should be greater than that with the referent of the non-subject (i.e.

him

= Bill). Therefore,

there is a logical conflict between these two empathy relationships. This conflict has been created

non-intentionally, however, by placing the agent NP

Bill's roommate

in subject position and the theme

NP

him

(

=Bill

) in object position, as dictated by the subcategorization requirement of the transitive

verb

hit

. That is, there is no intentional/marked violation of the Ban on Conflicting Empathy Foci.

Hence, there is no penalty for the violation. The above explanation is schematically summarized in (5):

(5) Then Bill

j

's roommate hit him

j

. (=1c)

Descriptor EH: E(Bill) > E(Bill's roommate = John)

Surface Structure EH: E(subject=Bill's roommate=John) > E(him=Bill) Transitivity: *E(Bill) > E

(John) > E(Bill)

Markedness Principle for Discourse Rule Violations: The above violation is unintentional ⇒ no

penalty

Now we can account for the marginality or unacceptability of (2c):

Page 2 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Blac...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

(6) ??/*Then John

i

's roommate was hit by him

i

. (=2c)

Descriptor EH: E(John) > E(John's roommate = Bill)

Surface Structure EH: E(subject = John's roommate = Bill) > E(him=John) Transitivity of

Empathy Relationships: *E(John) > E(Bill) > E(John) [a violation of the Ban on Conflicting

Empathy Foci]

Markedness Principle for Discourse Rule Violations: The above violation has been created by

the speaker's intentional use of a marked construction (i.e. the passive sentence construction)

⇒ a penalty

Note that the Markedness Principle for Discourse Rule Violations penalizes (2c) because the violation

of the Ban on Conflicting Empathy Foci that the sentence contains is intentional. That is, the conflict in

empathy foci has been created by the speaker's intentional use of the passive sentence construction,

which didn't have to be used.

The marginality or unacceptability of sentences with a first-person

by

-agentive, as in (7b), illustrates

the working of the Speech Act EH:

(7) a. Then I hit John.

Speech Act EH E(speaker=I) > E(John)

Surface Structure EH E(subject=I) > E(non-subject=John)

E(speaker) > E(John) [no conflict]

b. ??/*Then John was hit by me.

Speech Act EH E(speaker=I) > E(John)

Surface Structure EH E(John) > E(me=speaker)

Transitivity: *E(speaker) > E(John) > E(speaker)

Markedness Principle: The above conflict has been created by the speaker's intentional use of

the passive sentence construction ⇒ a penalty

The marginality or unacceptability of discourses such as (8b) illustrates the importance of the role

that the Topic EH plays in the Empathy Perspective:

(8) a. Mary had quite an experience at the party she went to last week. √She slapped a drunken

reporter on the face.

Surface Structure EH E(she=Mary) > E(a drunken reporter)

Topic EH E(she=Mary) > E(a drunken reporter)

E(Mary) > E(a drunken reporter) [no conflict]

b. Mary had quite an experience at the party she went to last night. *A drunken reporter was

slapped on the face by her.

Surface Structure EH E(a drunken reporter) > E(her=Mary)

Topic EH E(she=Mary) > E(a drunken reporter)

Transitivity: *E(a drunken reporter) > E(Mary) > E(a drunken reporter) Markedness Principle:

The above conflict has been created by the speaker's intentional use of the passive sentence

construction ⇒ a penalty

Thus, (8b) is unacceptable because Passivization, which is an optional process, has been used

intentionally to create a conflict in empathy relationships.

1

Observe now the next discourse fragments:

(9) Mary had quite an experience at the party she went to last night.

a. She met a

New York Times

reporter.

b. *A

New York Times

reporter met her.

c. A

New York Times

reporter asked her about her occupation.

Both (9b) and (9c) have a non-topic NP in subject position and a topic NP in non-subject position, but

while there is nothing wrong with (9c), (9b) is totally unacceptable in the given context. The Empathy

Page 3 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Blac...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

Principle accounts for this fact by attributing it to the fact that

meet

is a reciprocal verb. If two people

(say, John and Mary) met, the speaker has the following four alternatives in reporting this event using

meet:

(10) a. John and Mary met.

b. Mary and John met.

c. John met Mary.

d. Mary met John.

The relationship that (10c, d) have with (10a, b) is similar to the one that passive sentences have with

their active counterparts in that they involve the speaker's intentional choice of

John

and

Mary

in

subject position, and

Mary

and

John

in non-subject position in (10c, d), respectively. That is, (10c, d)

can be characterized as the passive versions of (10a, b) and thus constitute marked constructions. In

contrast, if John asks Mary about her occupation, the subcategorization requirement of the verb

ask

automatically places the agent NP

John

in subject position and the theme NP

Mary

in object position.

This difference between

meet

and

ask

accounts for the contrast between the unacceptable (9b) and

the acceptable (9c). More schematically, the acceptability status of the three sentences in (9) is

accounted for in the following fashion:

(11)

Observe next the following sentences:

(12) a. John told Mary that Jane was seriously sick.

b. Mary heard from John that Jane was seriously sick.

a. She met a

New York Times

reporter. (=9a)

Topic EH

E(she=Mary) > E(a

NY

Times

reporter)

Surface Structure EH

E(she=Mary) > E(a NY

Times reporter)

E(Mary) > E(a

NY Times

reporter) [no conflict]

b. *A

New York Times

reporter met her. (=9b)

Topic EH

E(she=Mary) > E(a

NY

Times

reporter)

Surface Structure EH

E(a NY Times reporter)

> E(her=Mary)

Transitivity: *E(Mary) > E(a

NY Times

reporter) > E(Mary)

Markedness Principle: The above conflict has been created by

the speaker's intentional choice of a non-topic NP as subject of

meet

a penalty

c. A

New York Times

reporter asked her about her occupation.

(=9c)

Topic EH

E(she=Mary) > E(a

NY

Times

reporter)

Surface Structure EH

E(a NY Times reporter)

> E(her=Mary)

Transitivity: *E(Mary) > E(a

NY Times

reporter) > E(Mary)

Markedness Principle for Discourse Rule Violations: The above

violation is unintentional ⇒ no penalty

Page 4 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Blac...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

(13) a. John sent Mary a Valentine's Day present.

b. Mary received from John a Valentine's Day present.

Hear from

in (12b) and

receive from

in (13b) are marked verbs in the sense that they place non-agent

NPs in subject position and agent NPs in non-subject position. That is, they are like passive verbs in

that they represent the speaker's intentional choice of non-agent NPs in subject position. This fact

accounts for the acceptability status of the following sentences:

(14) a. I told Mary that Jane was seriously sick.

b. ??Mary heard from me that Jane was seriously sick.

(15) a. I sent Mary a Valentine's Day present.

b. ??Mary received from me a Valentine's Day present.

(14b) and (15b) are marginal out of context because they contain a conflict in empathy relationships

just as (7b) does, which conflict has been created by the speaker's use of the marked verbs

hear from

and

receive from

.

2

Now, we can account for the acceptability status of the following sentences:

(16) a. John

i

told Mary

j

what she

j

had told him

i

two days before.

b. John

i

told Mary

j

what he

i

had heard from her

j

two days before.

c. Mary

j

heard from John

i

what she

j

had told him

i

two days before.

d. ??Mary

j

heard from John

i

what he

i

had heard from her

j

two days before.

3

3

3

3

I give below the empathy relationships represented by the main clause and the embedded clause of

each of (16a-d). I use the notation “E(x) m> E(y)” if the empathy relationship is derived from the

Surface Structure EH due to the use of marked patterns (e.g. the passive construction and special

verbs such as

meet, hear from

, and

receive from

).

(17) a. John

i

told Mary

j

what she

j

had told him

i

two days before. (=16a) Surface Structure EH

Main Clause: E(John) > E(Mary)

Embedded Clause: E(she=Mary) > E(him=John)

Transitivity: *E(John) > E(Mary) > E(John)

Markedness Principle: No marked patterns are used no penalty

b. John

i

told Mary

j

what he

i

had heard from her

j

two days before. (=16b) Surface Structure EH

Main Clause: E(John) > E(Mary)

Embedded Clause: E(he=John) m> E(her=Mary) No conflict

c. Mary

j

heard from John

i

what she

j

had told him

i

two days before. (=16c) Surface Structure EH

Main Clause: E(Mary) m> E(John)

Embedded Clause: E(she=Mary) > E(him=John) No conflict

d. ??Mary

j

heard from John

i

what he

i

had heard from her

j

two days before. (=16d)

Surface Structure EH

Main Clause: E(Mary) m> E(John)

Embedded Clause: E(he=John) m> E(her=Mary)

Transitivity: *E(Mary) m> E(John) m> E(Mary)

Markedness Principle: The above conflict has been created by the intentional use of the marked

verb

hear from

penalty

The Markedness Principle for Discourse Rule Violations states that conflicts in empathy relationships

attributable to the speaker's intentional use of marked constructions result in unacceptability, but

when there is a good reason for using such a construction, an ensuing conflict in empathy

relationships does not result in a penalty. Observe, for example, the following exchange:

(18) A: John says he hasn't met you before.

B: That's not correct. He met me last year at Mary's party.

Page 5 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Blac...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

Empathy Relationships for “He met me last year …”

Speech Act EH E(speaker=me) > E(non-speaker=he)

Surface Structure EH E(subj=he) m> E(non-subj=me)

Transitivity: *E(I) > E(he) m> E(I)

The sentence

he met me last year at Mary's party

in Speaker B's answer involves the use of the marked

verb

meet

, and therefore, there should be a penalty for the conflict in the empathy relationships that

the sentence contains. In spite of this fact, the sentence is perfectly acceptable in the given context. I

attribute this to the application of the following principle:

(19) T

HE

C

ORRECTIVE

S

ENTENCE

P

ATTERN

R

EQUIREMENT

: In correcting a portion of a sentence uttered

by someone else maintain the same sentence pattern and change only that portion of the

sentence that needs to be corrected, together with necessary tense and personal pronoun

switches.

Speaker B wants to correct Speaker A's remark that “he [John] hasn't met you before.” In accordance

with the Corrective Sentence Pattern Requirement, Speaker B maintains the same sentence pattern,

keeping

he

(

John

) in subject position, but switching

you

in object position to

me

referring to the

speaker himself/herself. Thus, the conflict in empathy relationships contained in Speaker B's answer

in (18) is not by design, but is required by the Corrective Sentence Pattern Requirement. Thus there is

no intentionality in the conflict, and hence there is no penalty for the conflict.

There is another discourse principle that makes sentences involving empathy relationship conflicts

acceptable. Observe first the following sentences:

(20) a. John read

War and Peace

last night.

b. ??

/*War and Peace

was read by John last night.

The unacceptability of (20b) is due to the fact that an inanimate NP is in subject position in a passive

sentence construction:

(21) Empathy Relationships for (20b)

Humanness EH E(John) > E(

War and Peace

)

Surface Structure EH E(War and Peace) m> E(John)

Transitivity: *E(John) > E(

War and Peace

) m> E(John)

Markedness Principle: The above conflict has been created by the speaker's intentional use of

the passive sentence construction a penalty

The above accounting for the unacceptability of (20b) predicts that the following sentences should be

as marginal or unacceptable as (20b), but these sentences are perfectly acceptable:

(22) a.

War and Peace

was written by Tolstoy.

b.

War and Peace

has been read by millions of people all over the world.

c.

War and Peace

has been read even by Bill.

The difference between the unacceptable (20b) and the acceptable (22a-c) lies in the fact that while

the latter sentences characterize what kind of book

War and Peace

is, the former does not have such a

characterizational property. That is, the fact that Tolstoy wrote

War and Peace

gives a robust

characterization of the novel. The fact that millions and millions of people all over the world have read

the novel says what kind of book it is. Likewise, the fact that even Bill -apparently someone who

doesn't ordinarily read books - has read the book implicates that many other people have read it, and

characterizes what kind of book it is. In contrast, (20b) cannot be interpreted as a characterizational

sentence: a single event of John's reading the novel doesn't characterize what kind of book it is.

Given that passive sentences with inanimate subjects and human by-agentives are acceptable if they

robustly characterize the referents of the subject NPs, we still need to explain why the empathy

Page 6 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Blac...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

relationship conflicts created by the use of the marked sentence pattern (i.e. Passivization) that (22a-

c) contain do not make them unacceptable. It seems that this is due to the fact that sentences that

characterize or define the referent of an NP are the most felicitous when that NP is placed in subject

position. For example, observe the following sentences:

(23) a. Whales are mammals.

b. Mammals include whales.

The above sentences are logically identical, but they are different in respect to what they characterize

or define. That is, (23a) is a sentence that characterizes or defines whales, whereas (23b) is a

sentence that characterizes or defines mammals. This observation leads to the following hypothesis:

(24) S

UBJECT

P

REFERENCE

FOR

C

HARACTERIZING

S

ENTENCES

: Sentences that characterize/define X are

most felicitous if X is placed in subject position. (Kuno 1990: 50)

We can now account for the acceptability of (22a-c) by saying that the empathy relationship conflicts

that these sentences contain have been forced by the Subject Preference for Characterizing Sentences,

and thus have not been created intentionally by the speaker.

There is another discourse phenomenon that seems to be explained in a principled way only by the

Empathy Perspective. When two NPs are conjoined, they must be arranged in a fixed order if the

descriptor for one NP is dependent on the descriptor for the other. Observe, for example, the

following sentences:

(25) a. John

i

and his

i

brother went to Paris.

b.

*

John

i

's brother and he

i

/John

i

went to Paris.

This fact can be accounted for by hypothesizing the following empathy principle:

(26) W

ORD

O

RDER

E

MPATHY

H

IERARCHY

: It is easier for the speaker to empathize with the referent

of a left-hand NP in a coordinate NP structure than with that of a right-hand NP.

E(left-hand NP) > E(right-hand NP)

Considering the fact the left-hand position in a coordinate structure is more prominent than the

right-hand position, and considering the fact that, given the subject and non-subject NPs, the former

is the more prominent position, the Surface Structure EH and the Word Order EH can be considered to

be two different manifestations of the same principle:

(27) S

YNTACTIC

P

ROMINENCE

E

MPATHY

H

IERARCHY

: Give syntactic prominence to a person/object

that you are empathizing with.

The Surface Structure EH deals with the manifestation of syntactic prominence in terms of structural

configuration, while the Word Order EH deals with the manifestation of syntactic prominence in terms

of linear order.

Let us examine some more examples relevant to the Word Order EH:

(28) a. I saw John and a policeman walking together yesterday.

b. ??I saw a policeman and John walking together yesterday.

(29) a. I saw you and a policeman walking together yesterday.

b. ??I saw a policeman and you walking together yesterday.

(30) a. John and someone else will be there.

b. *Someone else and John will be there.

The marginality of (28b) and (29b) arises from the conflict between the Word Order EH and the Topic

Page 7 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Blac...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

EH. The unacceptability of (30b) arises from the conflict between the Word Order EH and

Descriptor/Topic Empathy Hierarchies. Note that

someone else

in the sentence is a descriptor that is

dependent upon

John

.

Recall now that I mentioned previously that since

meet

is a reciprocal verb, if John and Mary met,

there are four ways to describe this event:

(10) a. John and Mary met.

b. Mary and John met.

c. John met Mary.

d. Mary met John.

I have already explained the difference between (10c) and (10d) by saying that the former involves the

speaker's intentional placement of

John

in subject position, while the latter involves his/her

intentional choice of

Mary

in that position. The Word Order EH can account for the difference between

(10a) and (10b): the speaker's empathy with John is greater than that with Mary in (10a), and the

speaker's empathy with Mary is greater than that with John in (10b).

The Word Order EH interacts in an interesting way with a “modesty” principle taught in prescriptive

grammar. For example, observe the following sentences:

(31) a. ??I and John are good friends.

b. John and I are good friends.

(31b) involves the following empathy hierarchy conflicts:

(32) Empathy Relationships of (31b):

Speech Act EH E(I) > E(John)

Word Order EH E(John) m> E(I)

Transitivity: *E(I) > E(John) m> E(I)

Markedness Principle: The above conflict is intentional because the speaker has intentionally

placed

John

in the left-hand position, and

I

in the right-hand position a penalty

That is, from the point of view of the Empathy Perspective, (31b) should be unacceptable, and (31a)

acceptable. However, prescriptive grammar says that the first person nominative pronoun should be

placed at the end of a list. I will refer to this artificial rule as the Modesty Principle:

(33) T

HE

M

ODESTY

P

RINCIPLE

: In the coordinate NP structure, give the least prominence to the

first person pronoun.

We can now account for the acceptability of (31b) by stating that the choice of the expression

John

and I

, which is instrumental in creating an empathy relationship conflict, is not intentional, but is

forced on the speaker by the Modesty Principle. Therefore, there is no penalty for the violation.

4

2.2 More on the Markedness Principle for

2.2 More on the Markedness Principle for

2.2 More on the Markedness Principle for

2.2 More on the Markedness Principle for Discourse Rule Violations

Discourse Rule Violations

Discourse Rule Violations

Discourse Rule Violations

The contrast in the acceptability status of the following two sentences seems to be unexplainable

without resorting to the Markedness Principle for Discourse Rule Violations:

(34) a. *At the gate were John

i

's brother and John

i

/he

i

smiling at me.

b. At the top of the rank list were Johni's brother and Johni in that order.

Both (34a) and (34b) contain a conflict between the Descriptor EH (i.e. E(John) > E(John's brother)) and

the Word Order EH (i.e. E(John's brother) > E(John)). (34a) is unacceptable because the placement of

John's brother

to the left of

John

in the NP coordination is by the speaker's design. In contrast, (34b) is

acceptable because the placement of

John's brother

to the left of

John

has been forced on the speaker

by the relative ranking of the two siblings. That is, the empathy relationship conflict that (34b)

Page 8 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Blac...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

involves was forced upon the speaker and was not intentional, and therefore, there is no penalty for

the violation.

Observe next the following sentences:

(35) a. John gave a book to the girl.

b. John gave the book to a girl.

(36) a. John gave the girl a book.

b. ??John gave a girl the book.

(35a, b) are examples of the periphrastic dative sentence pattern, whereas (36a, b) are examples of

the incorporated dative sentence pattern. What needs to be explained is the marginality of (36b). It is

reasonable to assume that (36b) is marginal because it violates the well-known discourse principle

given below:

5

(37) F

ROM

-O

LD

-T

O

-N

EW

P

RINCIPLE

: In languages in which word order is relatively free, the

unmarked word order of constituents is old, predictable information first and new,

unpredictable information last.

Let us assume that the above principle applies to English in places where there is freedom of word

order. In (36b),

a girl

, which represents new information, appears before

the book

, whose anaphoric

nature marks that it represents old information. Therefore, the marginality or unacceptability of (36b)

can be attributed to its violation of the

From-Old-To-New Principle

. However, once one adopts this

approach to account for the marginality of (36b), the acceptability of (35a), repeated below, becomes

a puzzle:

(35) a. √John gave a book to the girl.

New Old

(36) b. ??John gave a girl the book.

New Old

As shown above, (35a) violates the From-Old-To-New Principle as much as (36b) does.

The above dilemma can be resolved by assuming that the periphrastic dative pattern represents the

underlying pattern for giving verbs, and that the incorporated dative pattern is derived by applying

D

ATIVE

INCORPORATION

to the underlying periphrastic dative pattern.

6

According to this hypothesis, the

violation of the From-Old-To-New Principle that (35a) involves is non-intentional because the

speaker simply used the underlying sentence pattern, and placed the theme NP

a book

in verb object

position and the goal NP

the girl

in prepositional object position. Therefore, there is no penalty for the

violation. In contrast, the violation of the Principle that (36b) involves is intentional because the

speaker has chosen to apply Dative Incorporation, an optional transformation. Therefore, the resulting

violation of the From-Old-To-New Principle cannot go unpenalized, and the unacceptability of the

sentence results.

7

2.3 Empathy and reflexive pronouns

2.3 Empathy and reflexive pronouns

2.3 Empathy and reflexive pronouns

2.3 Empathy and reflexive pronouns

There are languages (e.g. Japanese, Korean, and Chinese) that require that the antecedents of

reflexive pronouns be animate and, most preferably, human. This suggests that the reflexive

pronoun, at least in these languages, requires a high degree of the speaker's empathy with its

referent. The fact that sentences such as (38b) below are acceptable might give a false impression

that English reflexives are free from such a requirement, but the fact that (39b) is unacceptable shows

that they are subject to an empathy requirement, albeit to a lesser degree.

(38) a. John criticized himself.

b. Harvard overextended itself in natural sciences in the sixties.

(39) John wrote to his friends about himself.

b. *Harvard wrote to its alumni about itself.

8

8

8

8

Page 9 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Blac...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

The unacceptability of (39b) shows that English reflexive pronouns in oblique case position require a

high degree of the speaker's empathy with their referents. (39b) is unacceptable because it is not

possible for the speaker to empathize to a high degree with inanimate objects like Harvard University.

Empathy factors influence the interpretation of reflexive pronouns even when their referents are

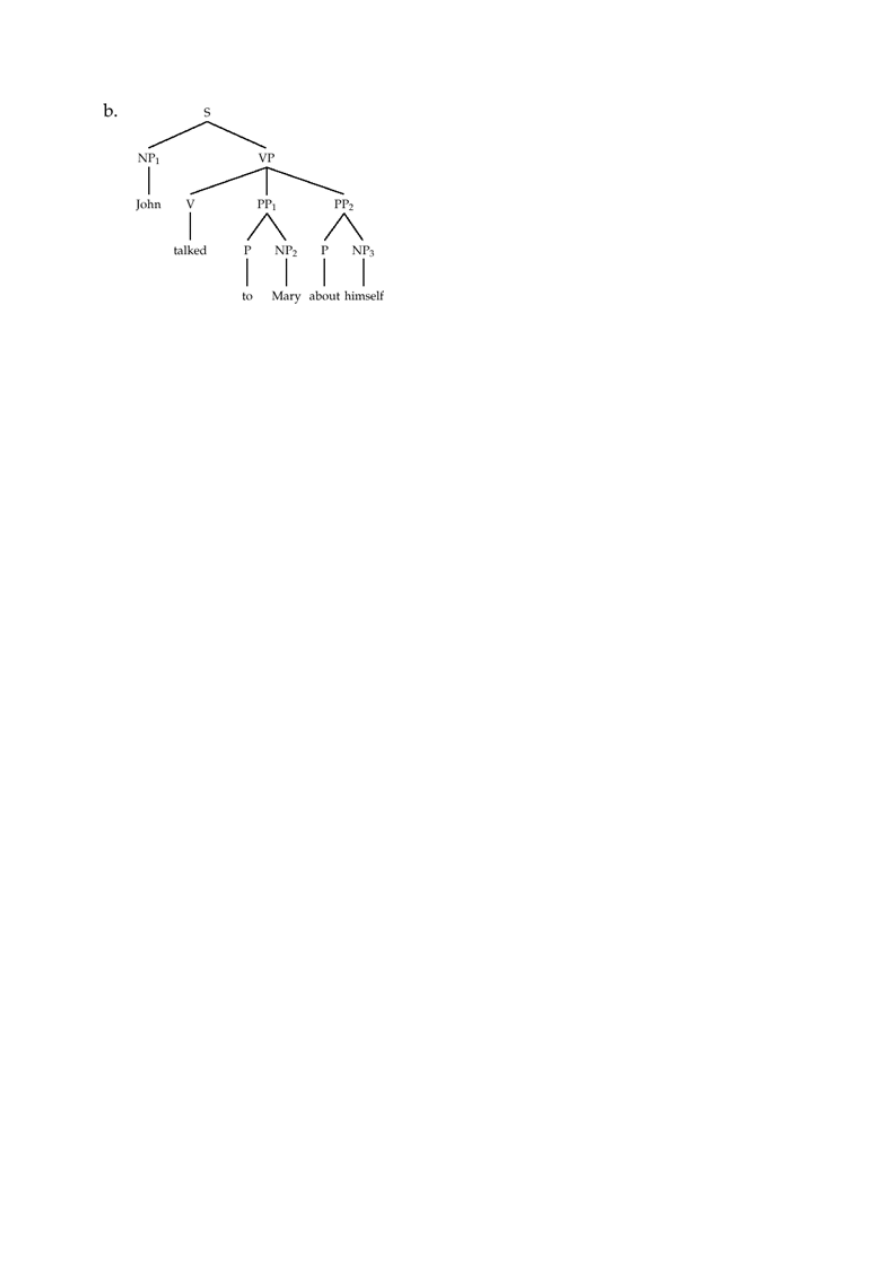

human. Observe first the following sentences:

(40) a. John talked to Mary about himself.

b. √/?/??Mary talked to Bill about himself.

While all speakers accept (40a), some speakers consider (40b) awkward or marginal. This fact can be

explained by assuming that a sentence containing a reflexive pronoun in oblique position is most

felicitous when the referent of the reflexive receives the highest degree of empathy in the sentence.

There is no problem with (40a) because the subject NP is the sentence's unmarked empathy focus (cf.

the Surface Structure EH) and the reflexive pronoun has that NP as its antecedent. In contrast, (40b) is

problematic in that the antecedent of the reflexive pronoun is not the highest-ranked candidate in the

empathy hierarchy on the unmarked interpretation of the sentence. Likewise, observe the following

sentences:

(41) a. √/?/??Mary talked to Bill about himself. (=40b)

b. ?/??/*I talked to Bill about himself.

There are many speakers who consider (41b) less acceptable than (41a). This can be attributed to the

fact that the subject NP in (41b), because it is a first person pronoun, is even stronger than

Mary

in

(41a) in its qualification as the focus of the speaker's empathy, and hence as the antecedent of the

reflexive. This makes the

Bill

of (41b) less qualified to be the antecedent of a reflexive pronoun than

the

Bill

in (41a), and makes (41b) less acceptable than (41a).

Observe next the following sentences:

(42) a. √/?/??John talked to Mary about herself.

b. *John talked about Mary to herself.

The fact that (42a) (and (40b)) is acceptable or nearly so for many speakers has been a problem in the

framework of Chomsky's (1981) theory of grammar because the reflexive pronoun is not c-

commanded by its intended antecedent

Mary

. According to Chomsky's binding theory, a reflexive

must be c-commanded by a co-indexed NP in a local context.

9

Chomsky (1981) circumvented this

problem by claiming that

talk to

in (42a) is reanalyzed as a single V, with a resulting loss of the PP

node dominating to

Mary

. Thus,

Mary

becomes the direct object of the V, and it c-commands the

reflexive pronoun. Chomsky argued that (42b) is unacceptable because reanalysis of

talk about

does

not take place, apparently because

about Mary

is not base-generated next to

talk

.

There is, however, a serious problem with the above account of the acceptability of (42a) and the

unacceptability of (42b). Observe the following sentence:

(43) ??/*John discussed Mary with herself.

There is no doubt that the reflexive pronoun in the above sentence is c-commanded by a co-indexed

NP (i.e.

Mary

) in its local domain. In spite of this fact, (43) is marginal or unacceptable. Observe,

however, that (43) and (42b) are more or less synonymous. Therefore, the unacceptability of (42b)

seems to be a non-syntactic phenomenon, rather than a syntactic one. In comparing the acceptable

(42a) with the unacceptable (42b), we note that while the antecedent of the reflexive pronoun in the

former is Mary as a human being, the antecedent of the reflexive in (42b) and (43) is semantically

inanimate; that is, the antecedent is what Mary is or what she has done. Thus, the unacceptability of

(43) is automatically accounted for in the framework of the Empathy Perspective via the requirement

that the referents of the antecedents of the reflexive pronouns in oblique position in English must

Page 10 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Bl...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

receive a high degree of the speaker's empathy. That is, (42b) and (43) are unacceptable because

Mary

, the antecedent of the reflexive pronouns, cannot receive a high degree of the speaker's

empathy because it is semantically inanimate.

Finally, observe the following picture-noun sentences involving reflexive pronouns:

(44) a. Mary cost John a picture of himself in the paper.

Intended Interpretation: “In order to impress Mary, John paid for a picture of himself to be

printed in the newspaper.” or “John was adversely affected by the fact that what Mary had done

caused his picture to appear in the newspaper.”

b. *Mary cost John a picture of herself in the paper.

Intended Interpretation: “In order to impress Mary, John paid for her picture to be printed in the

newspaper.”

Note that in these sentences

John

is semantically human because it represents the experiencer of the

cost or damage, whereas

Mary

is semantically inanimate because it represents notions such as “what

Mary had done,” “(John's) desire to impress Mary,” and so on. These sentences also show that reflexive

pronouns in picture nouns are also empathy expressions, and as such require a high degree of the

speaker's empathy with their referents. There are several other factors that conspire to produce the

acceptability judgments for these sentences; see Kuno 1987: Chap. 4.5) for details.

3 Direct Discourse Perspective

3 Direct Discourse Perspective

3 Direct Discourse Perspective

3 Direct Discourse Perspective

3.1 Logophoric NP constraint

3.1 Logophoric NP constraint

3.1 Logophoric NP constraint

3.1 Logophoric NP constraint

Observe the following sentences:

(45) a. John said, “I am a genius.”

b. Johni said that he

i

was a genius.

(46) a. John said to Mary, “You are a genius.”

b. John said to Mary

j

that shej was a genius.

(47) a. John said about Maryj, “Mary

j

/Shej is a genius.

b. John said about Mary

j

that she

j

was a genius.

(45a), (46a), and (47a) contain direct discourse quotations, whereas (45b), (46b), and (47b) contain

indirect discourse clauses. In the indirect discourse clauses in (45b), (46b), and (47b), the pronouns

are coreferential with main-clause NPs. However, there is a significant difference between the

pronouns in (45b) and (46b) and the pronoun in (47b). That is, in the former, the pronouns

correspond to the first and second person pronouns in the corresponding direct quotations: they

cannot correspond to non-pronominal NPs because the following sentences are unacceptable:

10

(48) a. *John

i

said, “John

i

is a genius.”

b. *John said to Mary

j

, “Mary

j

is a genius.”

Let us refer to saying and asking verbs as l

OGOPHORIC

VERBS

(abbreviated as LogoV), and to their

complement clauses as

LOGOPHORIC

COMPLEMENTS

(abbreviated as LogoComp). Given a sentence with a

logophoric complement, I will use the term Logo-1 NP (or the abbreviation Logo-1) to refer to the NP

in the main clause that refers to the speaker of the utterance represented by the logophoric

complement. Likewise, I will use the term Logo-2 NP (or the abbreviation Logo-2) to refer to the

hearer of the utterance. These terms are illustrated in (49):

(49) John

i

said to Mary

j

that she

j

was a genius.

Logo-1 LogoV Logo-2 LogoComp

I assume that even sentences with complements that do not have direct discourse counterparts are

logophoric complements if they represent the thoughts, feelings, or realization of the referent of the

Page 11 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Bl...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

main-clause Logo-1 or Logo-2 NP:

(50) a. John thinks that he is a genius.

Logo-1 LogoV LogoComp

b. Hypothetical Structure: [John thinks, “[I am a genius.]”]

(51) a. John heard from Mary that she was sick.

Logo-2 LogoV Logo-1 LogoComp

b. Hypothetical Structure: [John heard from Mary, “[I am sick]”]

I will refer to an analytical framework that makes use of the notions described above as a direct

discourse perspective, or alternately as a

LOGOPHORIC

perspective.

Kuno (1987: Chap. 3) has shown that an NP in a logophoric complement (in an extended sense, as

shown above) that is intended to be coreferential with the main-clause Logo-1 or Logo-2 NP behaves

very differently from those NPs that are not coreferential with either of them. I will illustrate this

difference by using a few examples from (Kuno 1987) and add a new set of data from Kuno (1997)

that further illustrates the importance of the direct discourse perspective. Observe, first, the following

sentences:

(52) a. The remark that Churchill

i

was vain was often made about him

i

.

b. *The remark that Churchill

i

was vain was often made to him

i

.

While (52a) is acceptable on the interpretation in which the non-pronominal full NP

Churchill

in the

embedded clause is coreferential with the pronoun

him

in the main clause, such an interpretation is

ruled out for (52b). This contrast can be explained only by paying attention to who said what. I will

represent what was said using a direct discourse representation:

(53) a. [People often made about Churchill the remark “[Churchill is vain]”]

Logo-1 -Logo-1/2

b. [People often made to Churchill the remark “[You are vain]”]

Logo-1 Logo-2

Observe that

Churchill

in the matrix clause of (53a) is marked as -Logo-1/2 because it is neither the

speaker NP nor the hearer NP of the proposition represented by the direct discourse quotation. The

subject of the direct discourse quotation is

Churchill

, and not

you

, because, again, Churchill was not

the hearer of the remark. In contrast,

Churchill

in the matrix clause of (53b) is marked as Logo-2

because it is the hearer NP of the direct discourse quotation, which has

you

, and not

Churchill

, in

subject position. The fact that (52a) is acceptable but (52b) is not suggests that a full NP (i.e. a non-

reflexive and non-pronominal NP) in the direct discourse representation of a logophoric complement

can remain as a full NP if other conditions are met, as in (52a), but a second person pronoun in the

direct discourse representation of a logophoric complement cannot be realized as a full NP. That is, a

second person pronoun

you

must remain pronominal in indirect discourse formation.

Likewise, observe the following sentences:

(54) a. The allegation that John

i

was a spy was vehemently denied by himi.

b. *The claim that John

i

was a genius was made by him

i

.

While (54a) is acceptable on the interpretation whereby the full NP

John

in the embedded clause is

coreferential with the pronoun

him

in the main clause, such an interpretation is ruled out for (54b).

This contrast can also be explained by observing the direct discourse representation of what was said

by whom:

(55) a. [John denied the allegation “[John is a spy]”]

b. [John made the claim “[I am a genius]”]

Page 12 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Bl...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

Note that John was neither the “speaker” nor necessarily the hearer of the allegation. This explains

why

John

, and not

I

or

you

, appears in subject position of the direct discourse representation in

(55a).

11

In contrast, John was necessarily the “speaker” of the claim, and therefore, the subject of the

direct discourse representation in (55b) must be a first person pronoun. The fact that (54b) is

unacceptable suggests that a first person pronoun in the direct discourse representation of a

logophoric complement cannot be realized as a full NP in the derived surface sentences. That is, the

first person “I” in a direct discourse representation has to remain pronominal in indirect discourse

formation. I should hasten to add that if Passivization does not apply to (52a) and (54a), there is no

way to pronominalize the main clause NPs

Churchill

and

John

and keep

Churchill

and

John

in the

embedded clause unpronominalized:

(56) a. *People often made about him

i

the remark that Churchilli was vain.

b. *He

i

vehemently denied the allegation that John

i

was vain.

But the unacceptability of (56a, b) can be attributed to violation of Principle C (see section 3.2 of this

paper) of my version of the Binding Theory, which says that an R-expression (a full NP) cannot be c-

commanded by a co-indexed NP (with PP nodes not counting for the purpose of delimiting the c-

command domain of a given node).

Let us depart from the account given above, which is based on the direct discourse representation of

logophoric complement clauses, and move to one which assumes that indirect discourse logophoric

complements are base-generated as such. In that framework, the constraint that we have observed

above can be restated in the following manner:

(57) L

OGOPHORIC

NP C

ONSTRAINT

: Given a sentence with a matrix Logo-1/2 NP and a logophoric

complement attributable to that Logo-1/2 NP, a full NP in the logophoric complement cannot

be coreferential with the Logo-1/2 NP in the main clause. (cf. Kuno 1987: 109)

According to this constraint, the acceptability status of the sentences in (52) and (54) can be

accounted for in the following manner:

(58) a. The remark that [Churchill

i

was vain] was often made about him

i

.

LogoComp -Logo-1/2

b. *The remark that [Churchill

i

was vain] was often made to him

i

.

LogoComp Logo-2

(59) a. The allegation that [John

i

was a spy] was vehemently denied by him

i

.

LogoComp -Logo-1/2

b. *The claim that [John

i

was a genius] was made by him

i

.

LogoComp Logo-1

(58a) and (59a) are acceptable because full NPs in their logophoric complements are co-indexed with

main clause NPs that represent neither the speaker nor the hearer of the propositions that the

logophoric complements represent. In contrast, (58b) and (59b) are unacceptable because full NPs in

their logophoric complement clauses are co-indexed with the main clause hearer/speaker NPs that

the logophoric complements are attributable to. Observe next the following sentences:

(60) a. *The claim [

LogoComp1

that John

i

said [

LogoComp2

that Bill

j

was a spy]] was made by him

i

.

cf. John made the claim:

“I

said that Bill is a spy.”

b. *The claim [

LogoComp1

that John

i

said [

LogoComp2

that Billj was a spy]] was made by him

j

.

cf. Bill made the claim: “John said that

I

am a spy.”

The fact that the sentence is unacceptable on the

him = Bill

interpretation shows that the Logophoric

NP Constraint applies between a full NP (e.g.

Bill

in (60b)) in a logophoric complement and a Logo-1/2

NP (e.g.

him

in (60b)) in a higher clause, even if there is an intervening Logo-1/2 NP (e.g.

John

in

(60b)) between the two.

Page 13 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Bl...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

There are many phenomena that can be accounted for only in the Logophoric Perspective. They are

discussed in detail in Kuno (1987: Chap. 3).

3.2 The Logophoric NP

3.2 The Logophoric NP

3.2 The Logophoric NP

3.2 The Logophoric NP Constraint and the Binding Theory

Constraint and the Binding Theory

Constraint and the Binding Theory

Constraint and the Binding Theory

I will now show that the Logophoric NP Constraint can resolve the puzzle given in (61) that has defied

attempts at explanation by scholars working in the framework of Chomsky's

BINDING

THEORY

(see also

Huang, this volume).

(61) a. *Which claim that John

i

was asleep was he

i

willing to discuss? (Chomsky 1993)

b. Which claim that John

i

made did he

i

later deny? (Lebeaux 1992)

The problem here is at what stage the unacceptability of these sentences can be captured as involving

a violation of Principle C of the Binding Theory:

(62) Principle C: An R-expression cannot be co-indexed with a c-commanding NP.

12

12

12

12

C-command: A c-commands B iff the branching node α1 most immediately dominating A

either dominates B or is immediately dominated by a node α

2

that dominates B, and α

2

is of

the same category type as α

1

. (Reinhart 1976)

For those readers who are not familiar with the notion of c-command and Chomsky's Binding Theory,

it is sufficient for the purpose of this paper to interpret Principle C in a much more limited sense as

meaning that, given a sentence with NP

1

in subject position and NP

2

elsewhere in the same sentence,

NP

2

cannot be interpreted as coreferential with NP

1

, as illustrated below:

(63) a. *John

i

/*He

i

hates

Johni's

mother.

b. *John

i

/*He

i

hated the man that

John

i

shared an office with.

c. *John

i

/*He

i

thinks that

John

i

is a genius.

The above sentences are all unacceptable because the italicized

John

is intended to be coreferential

with the main clause subject, in violation of Principle C.

Returning to (61a), it has been assumed that Principle C applies to the open sentence portion of the

abstract representation (called the LF representation) of the structure of the sentence informally

shown in (64):

(64) LF representation of (61a):

[Which x [he was willing to discuss [x claim that John was asleep]]]

{______Open sentence______}

That is, it has been assumed, in essence, that the LF representation given in (64) is illicit on the

coreferential interpretation of

he

and

John

because it violates Principle C in the same way that the

following sentence does:

(65) *He

i

was willing to discuss which claim that John

i

was asleep.

The above account of the unacceptability of (61a) immediately runs into difficulty, however, because it

predicts that (61b) should also be unacceptable because it violates Principle C in the same way that

(67) does:

(66) LF representation of (61b):

[Which x [he did later deny [x claim that John made]]]

(67) *He

i

did later deny the claim that John

i

made.

Attempts have been made in the framework of the Minimalist Program (Freidin 1986, 1994, 1997;

Lebeaux 1988, 1992, 1995; Chomsky 1993) to resolve the above puzzle and account for the

Page 14 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Bl...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

acceptability of (61b) and the unaccept-ability of (61a) by attributing it to the difference in the ways

that complements and adjuncts are introduced into sentence structures. Noting that the embedded

clause in (61a) is a complement clause of the noun

claim

, whereas the embedded clause in (61b) is an

adjunct relative clause of the noun, minimalist theorists have claimed that the contrast in acceptability

status between these two sentences can be accounted for by assuming the following:

(68) (i) The introduction of complements into sentence structures must be cyclic.

(ii) The introduction of adjuncts into sentence structures can be cyclic or non-cyclic.

Thus, they have assumed that Principle C applies to the LF representations that are informally shown

below:

(69) a. LF representation of (61a):

[Which claim that John was asleep [he was willing to discuss {which claim that John was

asleep}]]

b. LF representation of (61b)

[Which claim that John made [he was willing to discuss {which claim}]]

In the above LF representations, the copy of a fronted wh-expression is shown in curly brackets. Note

that the complement clause

that John was asleep

in (69a) is adjoined to the noun

claim

before the

syntactic fronting of the

wh

-expression, whereas the adjunct clause

that John made

in (69b) is

adjoined to the fronted

which claim

, and not to the expression before

wh

-movement takes place.

Principle C disallows the co-indexing of the full NP

John

with the c-commanding

he

in the open

sentence part (i.e.

[he was willing to discuss {which claim that John was asleep}]

). In contrast, Principle

C does not apply to the open sentence portion of the LF representation in (69b) because there is no

full NP there. Principle C does not apply to

John

in the fronted wh-expression because it is not in the

open sentence part of the LF representation (and

he

does not c-command

John

anyway).

The above account of the contrast between (61a) and (61b) appears to be credible when coupled with

the contrast between (70a) and (70b), which also appears to show an

ARGUMENT

/

ADJUNCT

ASYMMETRY

:

(70) a. ??/*Which pictures of John

i

did he

i

like? (Lebeaux 1992)

b. Which pictures near John

i

did he

i

look at? (Lebeaux 1992)

Observing that

of John

in (70a) is a complement of

pictures

, but

near John

in (70b) is an adjunct,

Lebeaux (1992) attempts to account for the marginality/unacceptability of (70a) and the acceptability

of (70b) on the coreferential interpretation of

John

and

he

in the following way:

(71) a. LF representation of (70a)

[Which pictures of John [he did like {which pictures of John}]]

b. LF representation of (70b):

[Which pictures near John [he did look at {which pictures}]]

The introduction of

of John

in (70a) takes place before the fronting of the

wh

-expression

which

pictures

because it is a complement of

pictures

. Therefore, a copy of the fronted

wh

-expression

which pictures of John

is in the object position of the verb

like

, as shown in (71a). Thus, Principle C

disallows the co-indexing of

John

with the c-commanding

he

. This explains the unacceptability of

(70a) on the coreferential interpretation of

John

and

he

. In contrast, the introduction of

near John

in

(70b) can take place after the

wh

-movement of

which pictures

because it is an adjunct, not a

complement, of

pictures

. Therefore, the copy of

John

is absent in the open sentence part of the LF

representation of the sentence, as shown in (71b). Principle C is inapplicable to the open sentence

part of (71b), and hence Principle C does not mark (70b) unacceptable on the coreferential

interpretation of

John

and

he

.

The above account of the contrast between (61a) and (61b) and between (70a) and (70b), based on

the claimed asymmetry in the ways that arguments and adjuncts are introduced into sentence

Page 15 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Bl...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

structures, does not go far beyond these four sentences, however. Once the database of sentences

with the same patterns is only slightly extended, it becomes clear that the claimed asymmetry is an

illusion. Observe the following sentences:

(72) a. Whose allegation that Johni was less than truthful did he

i

refute vehemently?

b. Whose opinion that Weld

i

was unfit for the ambassadorial appointment did he

i

try to refute

vehemently?

c. Whose claim that the Senator

i

had violated the campaign finance regulation did he

i

dismiss

as politically motivated?

d. Which psychiatrist's view that John

i

was schizophrenic did he

i

try to get expunged from the

trial records?

The embedded clauses in the above sentences are all complement clauses. Therefore, a Minimalist

analysis based on argument/adjunct asymmetry predicts that they should all be unacceptable. In spite

of this prediction, however, most speakers consider these sentences acceptable, and even those

speakers who judge them as less than acceptable report that they are far better than (61a).

The argument/adjunct asymmetry-based analysis of the contrast between (70a) and (70b) fares as

poorly, as witnessed by the acceptability of sentences such as the following:

(73) a. Which witness's attack on John

i

did he

i

try to get expunged from the trial records?

b. Which artist's portrait of Nixon

i

do you think he

i

liked best?

c. Whose criticism of John

i

did he

i

choose to ignore?

(73) a. Which doctor's evaluation of John

i

's physical fitness did he

i

use when he

i

applied to

NASA for space training?

b. Which psychiatrist's evaluation of John

i

's mental state did he

i

try to get expunged from the

trial records?

The PPs in the above sentences are all complements of the nouns (i.e.

attack, portrait, criticism,

evaluation

) and therefore, Freidin (1986), Lebeaux (1988) and Chomsky (1993) all predict that their LF

representations violate Principle C. But these sentences are all perfectly acceptable. The acceptability

of the sentences in (72)–(74) shows not only that an argument/adjunct-asymmetry-based account of

the contrast between (61a) and (61b) and between (70a) and (70b) is untenable, but also that to the

extent that the account is derived from the theoretical framework of the Minimalist Program, there is

something wrong with the theory itself.

3.3 Logophoric

3.3 Logophoric

3.3 Logophoric

3.3 Logophoric analysis

analysis

analysis

analysis

Observe now the contrast in acceptability status of the following sentences:

(75) a. *Which claim that John

i

had helped develop new technologies did he

i

make at last year's

national convention?

b. Which claim that John

i

made did he

i

later deny? (Lebeaux 1992)

The Logophoric NP Constraint can automatically account for the contrast between these two

sentences: (75a) involves a logophoric complement that is attributable to the matrix subject NP

he

.

The sentence violates the Logophoric NP Constraint because a full NP (i.e.

John

) in the logophoric

complement is co-indexed with the matrix Logo-1 NP (i.e.

he

). (75b), in contrast, does not involve a

logophoric complement, and therefore, the Logophoric NP Constraint has nothing to do with this LF

representation, hence the acceptability of this sentence.

The acceptability of the sentences in (72) can be accounted for in the same fashion. For example,

observe the following:

(72) a. Whose allegation that John

i

was less than truthful did he

i

refute vehemently?

The above sentence has a logophoric complement (i.e.

that John was less than truthful

), but the Logo-

Page 16 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Bl...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

1 NP of this complement is not

he

(=

John

), but

whose

. Therefore, the Logophoric NP Constraint does

not disallow the co-indexing of

John

and

he

.

Now let us re-examine (61a), the sentence that Chomsky, Lebeaux, and Freidin have all considered

unacceptable:

(61) a. *Which claim that John

i

was asleep was he

i

willing to discuss? (Chomsky 1993)

It seems that the sentence is potentially ambiguous with respect to whether the claim that John was

asleep is to be interpreted as John's claim or someone else's claim. As must be clear to the reader by

this time, the Logophoric NP Constraint predicts that the sentence is unacceptable if the claim is

interpreted as John's, but acceptable if it is interpreted as someone else's claim. This prediction is

consistent with the judgments that most, if not all, native speakers make about the sentence.

The above observations show that the account of the contrast between (61a) and (61b) that is based

on argument/adjunct asymmetry is untenable. That is, there is no justification for assuming that

arguments and adjuncts are different with respect to when they must or must not be introduced into

sentence structures. Let us assume that they are both introduced cyclically. According to this

hypothesis, (72a), (61b), and (75a) have the structures shown below:

(76) a. LF representation of (72a)

[Whose allegation that John was less than truthful [he did refute vehemently {whose allegation

that John was less than truthful}]]

b. LF representation of (61b)

[Which claim that John made [he did later deny {which claim that John made}]]

c. LF representation of (75a)

[[Which claim that John had helped develop new technologies] [he did make {which claim that

John had helped develop new technologies} at last year's national convention]]

The way that the Binding Theory (cf. Chomsky 1981) is organized, Principle C applies to the open

sentence part of these LF representations, and marks them as unacceptable. But (72a) and (61b) are

perfectly acceptable. Therefore, the Binding Theory needs to be re-examined to see if it has been

properly organized. The problem with its current organization is that it is based on the assumption

that since there are three types of NPs (i.e. anaphors, pronominals, and R-expressions), there should

be one rule for each NP type. I have proposed a different organization of the binding theory in Kuno

(1987). I show below first the overall difference in organization and then present revised binding

principles:

(77) Chomsky's Organization of the Binding Theory

a. anaphors in a local domain [coreference]

b. pronominals in a local domain [disjoint reference]

c. R-expressions in all domains [disjoint reference]

(78) Kuno (1987)'s Organization of the Binding Theory

a. anaphors in a local domain [coreference]

b. non-anaphors (pronominals and R-expressions) in a local domain [disjoint reference]

c. R-expressions in all domains [disjoint reference]

(79) Kuno (1987)'s Binding Principles

Principle A': An anaphor may receive a coreferential interpretation only with a c-commanding

NP within its local domain. N.B. An LF representation that contains an anaphor which is not

interpreted coreferentially with any NP in it is unacceptable.

Principle B': A non-anaphor (pronominal or R-expression) is obligatorily assigned disjoint

indexing

vis-à-vis

a c-commanding NP within its local domain.

Principle C': An R-expression is barred from receiving coreferential interpretation

vis-à-vis

a c-

commanding non-anaphor NP in either A- or A'-position.

13

13

13

13

N.B. Principle C does not apply to the reconstructed portion of the LF representation. (That is,

in a theoretical framework in which the binding theory applies to syntactic structures rather

Page 17 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Bl...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

than to LF representations, Principles A' and B' apply cyclically, and Principle C' applies post-

cyclically.)

C-command: A c-commands B iff the non-PP branching node α

1

most immediately dominating

A either dominates B or is immediately dominated by a node α

2

that dominates B, and α

2

is of

the same category type as α

1

.

With the above revised binding theory, (76a-c) pose no problem. In these LF representations, since

the non-anaphor

John

is in the embedded clause and the c-commanding NP

he

in the main clause

(that is, since

he

is not in

John's

local domain), Principle B' does not apply. Therefore, they are not

assigned disjoint indexing. Furthermore, Principle C' does not apply to an R-expression which is in

the reconstructed portion of the LF representation, and therefore, it is not assigned disjoint indexing

vis-à-vis

the c-commanding

he

. (The

John

in the fronted portion of the LF representation is not

assigned disjoint indexing with

he

either, because the latter does not c-command the former.) Thus,

there are no binding principles that block the coreferential interpretation of

he

and

John

. The

Logophoric NP Constraint does not apply to (76a) because

he

is not the Logo-1 NP of the complement

clause. It does not apply to (76b), either, because that sentence does not involve a logophoric

complement at all. Hence the acceptability of (72a) and (61b). On the other hand, the Logophoric NP

Constraint applies to (76c) because

he

is the Logo-1 NP of the complement clause and disallows a

coreferential interpretation of

he

and

John

, hence the unacceptability of (75a).

The above revised binding principles can also account for the contrast among the following three

sentences:

(70) a. ??/*Which pictures of John did he like? (Lebeaux 1992)

(73) a. Which witness's attack on John did he try to get expunged from the trial records?

(70) b. Which pictures near John did he look at? (Lebeaux 1992)

These sentences have the following LF representations:

(80) a. LF representation of (70a)

[Which pictures of John [

he

did like {which pictures of

John

}]]

b. LF representation of (73a)

[Which witness's attack on John [

he

did try to get {which witness's attack on

John

} expunged

from the trial records]]

c. LF representation of (70b)

[Which pictures near John [

he

did look at {which pictures near

John

}]]

Note in (80a) that the non-anaphor

John

is c-commanded by

he

in its local domain. Therefore,

Principle B' obligatorily assigns disjoint indexing to

he

and

John

. Hence the unacceptability of (70a). In

contrast, in (80b),

John

is not c-commanded by

he

in its local domain because

John's

local domain is

which witness's attack on John

. Hence Principle B' does not assign disjoint indexing to

he

and

John

.

Principle C does not apply to

John

in the reconstructed portion of the LF representation. (It applies to

John

in the fronted wh-expression, but it is not c-commanded by

he

, and thus no disjoint indexing

takes place.) Therefore, there is no binding principle that disallows the co-indexing of

he

and

John

.

Furthermore, the Logophoric NP Constraint does not apply to

he

and

John

either, because no

logophoric complement is involved. Therefore, it does not disallow the co-indexing of the two NPs,

hence the acceptability of (73a). Finally, in (80c), the c-commanding

he

is not in

John's

local domain

because there is a clause boundary between

he

and

John

, as witnessed by the fact that

John

is not in a

reflexive context:

(81) a. *He looked at pictures near himself.

b. *[He did look at [pictures [PRO near himself]]]

(82) a. *Mary talked with people angry about herself.

b. *[Mary talked with people [PRO angry about herself]]

Page 18 of 21

14. Empathy and Direct Discourse Perspectives : The Handbook of Pragmatics : Bl...

28.12.2007

http://www.blackwellreference.com/subscriber/uid=532/tocnode?id=g9780631225485...

Therefore, Principle B' does not apply to (80c), and consequently, there is no obligatory disjoint-

indexing of

he

and

John

by Principle B'. Principle C does not apply to

John

in the reconstructed portion

of the LF. (It applies to

John

in the fronted

wh

-expression, but since that is not c-commanded by

he

,

it does not bar co-indexing of the two NPs.) The Logophoric NP Constraint does not apply because

the sentence does not contain a logophoric complement. Thus, there is no rule that disallows the co-

indexing of the two NPs, hence the acceptability of (80c).

4 Concluding Remarks

4 Concluding Remarks

4 Concluding Remarks

4 Concluding Remarks

In this paper, I have examined various syntactic constructions in English and shown how syntactic and

non-syntactic constraints interact with one another to produce the acceptability status of sentences

that employ those constructions. Given a contrast in acceptability status like the one in (61), the

linguist who is unaware of the existence of various non-syntactic factors that interact with syntax

assumes that the contrast is due to syntactic factors and proposes syntax-based hypotheses to

account for it. In contrast, the linguist who is aware of various non-syntactic factors that closely

interact with syntax begins his/her analysis bearing in mind that the contrast might be due to one or

more such non-syntactic factors. I hope I have amply demonstrated in this paper which approach is

more productive in arriving at the correct generalizations on such constructions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am indebted to Karen Courtenay, Nan Decker, Tatsuhiko Toda, and Gregory Ward for their numerous

invaluable comments on earlier versions of this paper. I am also greatly indebted to Bill Lachman for

providing me with the phrase structure representation in note 9.

1 It is possible for a speaker to take a detached view of an event involving the referent of a topic NP. This is

why the Topic EH E(topic) ≥ E(non-topic) has “≥” rather than

“>”

.

2 Sentences of the same pattern as (14b) are acceptable if they are used as corrective sentences:

(i) Speaker A: Mary heard from Bill that Jane was seriously sick. Speaker B: No, she heard it from ME. I will

discuss empathy principle violations in corrective sentences later in this section. Likewise, sentences of the

same pattern as (15b) become acceptable if placed in contexts in which the time and location of the receipt

of the thing the speaker sent are at issue. For example, observe the following sentence:

(ii) When Bill

received from me

a package containing a maternity dress for his wife, they had already broken

up. Note that (ii) is not synonymous with (iii):

(iii) When

I sent

Bill a package containing a maternity dress for his wife, they had already broken up. It is

clear that while the mailing-out time of the package is at issue in (iii), the receipt time of the package is at

issue in (ii). That is, the speaker's use of the marked expression

receive from

in (ii) has been forced on the

speaker because of the necessity to refer to the receipt time rather than the mailing-out time. Therefore,

there is no intentionality in the speaker's use of the expression

receive from

in (ii), nor is there a penalty for

the conflict in empathy relationships that the sentence contains.

3 (16d) is acceptable if the pronouns are stressed, as shown in (ib) below. But note that (ii), which has the

same relative order of full names and pronouns, is acceptable without stress on the pronouns.

(i)a. ?? Maryi heard from Johnj what hej had heard from heri two days before. (=16d)

b. Mary

i

heard from John

j

what HE

j

had heard from HER

i

two days before.

c. Mary

i

told John

j

what he

j

had told her

i

two days before. The above phenomenon is similar to the

pronominalization phenomenon with possessive NPs as antecedents. First note that (ii) is perfectly

acceptable:

(ii) Billi's brother is visiting him

i

. But when two such sentences are juxtaposed as in (iiia), unacceptability

results:

(iii)a. *Bill

i

's brother is visiting him

i

, and John

j

's uncle is visiting him

j

.

b. Bill

i

's brother is visiting HIM

i

, and John

j

's uncle is visiting HIM

j

.