IMGx47

266 The Origin oj Civffisation

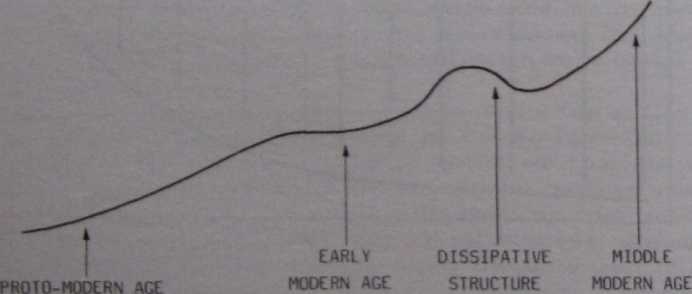

began to interact norę wigorously. coincident with Łhe expanding internation-alisn generated by the Renaissance mowement. Although this was undoubtedly a true civilising spurt, as we have clearly seen, yet it was essentially a sectiona1 process, and not a fuli genesis consistent with the dynamie test criteria we are using. If the Renaissance is part of the dawning modern age, as I believe it to be, we could, perhaps regard it as the 'proto-modern' stage, the first step on the stepped ascent to a fully modern ciwilisation. Throughout the ensuing fiue hundred years, (1378-1878), a wide geographical arena was the focus for this accelerating scalę of interactiwity as the critical culture mass approached the lewel to generate a true ciwilisation ewent. This takes us to the explosiwe burst, as identified by Norman Stone, AO 1878-1919. This was the birth of the modern age, the early modern era. International ciwilisation might then hawe been poised to make a major consolidation at this juncture, but the First World War was a sewere setback and the tragedy of the peace becoraes morę understandable when we retrace its progress as a series of ill considered actions and trenchant reactions that led, almost inewitably through the operation of dynamie Chain reactions, to the unmitigating horror of a second total war within one generation. Detailed study along these lines might reweal the dismal downward spiral of radiating Chain reactions inwolwed in this sorry sequence. Finally, our generation has undergone the same breathtaking crystallisation that enabled Classical Greece to emerge from a former Dark Age, and the new ciwilisation thus generated is clearly morę adwanced than the earlier burst that began around one hundred years ago.

Figurę 5.3 The Stepped Ascent of International Civiłisation

Italian

Renaissance

1300 AD 1878 1919 1940 1980

TIME

Within this last Fiue hundred year period seueral empires have risen and fallen following the classie life cycle curwe, but western ciwilisation itself has come to assume a morę detached, International aspect. Has it now an inner resilience to enable it to surwiwe despite the many wicissitudea to which its foremost members may be exposed? Our ciwilisation has become a global phenomenon with an aura of its own, albeit heawily influenced by its most dominant protagonists of the moment, no matter who they be. Perhaps each ascendant nation will leawe a lasting legacy of its finest contribut lons to allow the integrated whole to adapt and surwiwe. But can this international ciwilisation surmount the fragmentation which threatens to destroy it?

The time has surely come when a localised, parochial approach will no longer suffice. Unique new ciwilisations were not exclusiwe to antiquity, but in a world of fiue billion restless people, a global free-for-all could be a recipe for disaster. It is the elear operation of a far-from-equilibrium system lurching dangerously out of control. We need to see ourselwes within the wider setting of a uniwersał perspectiwe, a topie which brings us first to the unique identity of culture itself.

The Theoretical Evolution of Culture

To datę the discussion has taken culture to be the adaptiwe expression of human surwiwal patterns, charting the story of mankind through the phased sequences of his ewident cultural ewolution. Many experts refute the idea of progress in the story of man. The notion that people rushed through the Neolithic in order to reach the Bronze Age is patently absurd. Yet today, Julian Huxley's claim that we are poised on the threshold of the critical step of a self-conscious phase in human ewolution does make sense. The sheer weight of ewidence, some of which has been presented here, must alone dispute the charge that man is not making a modest headway towards a genuinely better structured existence for the species. But the pace of progress is agonisingly hesitant. And what can we say of human culture itself? If culture is a system it will be, in euery respect a walid corporate entity in its own right. Thus, it should hawe a theoretical origin, closely aligned to its emergence in the archaeological records. From this origin it should hawe undergone a sequence of ewolutionary growth and change which is detectable both on examination and analysis. While we cannot study either man or culture in isolation, as their destinies hawe been so thoroughly intertwined, a unique identity for culture as a system offers us piwotal new insights. We hawe concentrated almost ex-clusiuely, so far, on the cultural ewolution of man, but if human culture has its own discrete history, we can learn about its direct impact upon man by assessing culture theoretically. In chapter 7 this idea is taken further, to wiew culture in a broad biological context. Here, the entire discussion is turned around to examine the ewolution of culture per se - man's Totai Culture System - to show its unigue expansion and dewelopment through time.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

114 Krzysztof Waliszewski The origination of a new subdiscipline in financial science is connected w

na35?ck Deod. He wos deod. How the heli wos she supposed to do CPR on a man with two hearts? There s

Warsaw University of Technology

PAULHARVEY Ytmng-Peóple^Are^lderDerom! To The Ciliicm OJ Mafiic Yolley Toesday. Sepłember 19. IW Al

IMGx45 262 The Origin of CiviLisation from the capitulation of Damascus (AO 635) to the wic tory eas

Agreement") lub część Changes to the Original Leaming Agreement (w zależności od rodzaju wyjazd

226 United Nations — Treaty Series 1972 product originating in or consigned to the territory of

522 M. Daszykowski eł al. To illustrate this, Fig. la shows the original chromatogram of sample 12 (

56530 IMGx53 27$ The Origin of Cmlisation subsystem, functioning as a world state, probably on a fed

74085 IMGx56 284 The Origin of Civilisation In theory, there musi be sonę limit to the number of ris

270 REYIEWS proper to examine the original expression from the Rgveda (X. 14.8 punar astam ehi....ta

CCF20110611�052 A tongue slip „law”. „the target and the origin of a tongue-slip are both located In

więcej podobnych podstron