47284 S5004017

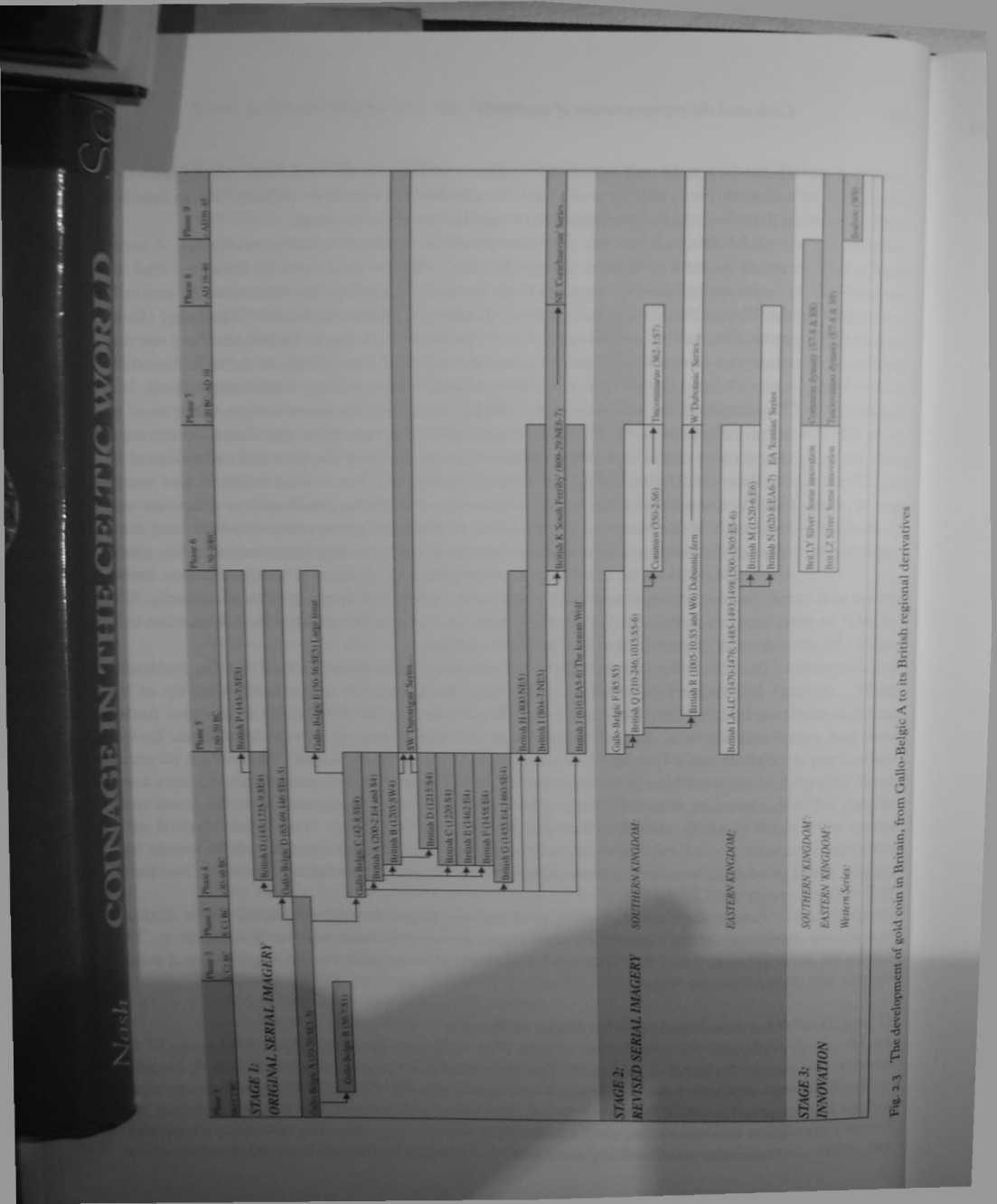

of progenitors and successors is rcpresented in Fig. 2.3. This is but one version, here ihe seąuence is based upon Allen’* original description of Galio-Belgie A-F and British A-R (Allen 1960), but the coins are placed into Haselgrove’s revised chrono-logical framework (Haselgrove 1987). As with all typologie* and classifications, there are competing ways of arranging these serie*. Variants have been published by Haselgrove (1987:86) and Van Arsdell (19893:34), but the akerations are generally in smali aspects of detail; what is important to the argument here is the broad picture.

The crucial point here is that all of the earły gold of Britain derived from one ancestor, in this case starting with Ga 11 o-Belgie A (called Stage 1 in Fig. 2.3). This family of imagery lasted until the Roman annexation in some areas, such as in the SW (the Durotriges), and in the NE (the Corieltauvi). Each new issue closeły followed its predecessor until related coinage* covered much of lowland Britain. Aspects of this development in these two regions are shown in Fig. 2.4. In the case of the NE coin serie*, the coins condnued to be madę of gold, and the image went through a serie* of incremental changes. Apollo’* head slowly became increasingly abstract until only the wreath survived, while the horse became disjointed until it was rcpresented only by a senes of crescents. In the later stages, when inscriptions appeared on the coin they still fitted in with the origmal conception of the imagery, remaining subserrient to it. In the SW senes, in the territory commonły ascribed to the Durotriges, the image again changed by subtle degrees until the head and horse were rcpresented by an abstract collection of dots and lines. Just as the image changed, so did the afloy that madę up the coin. Whilst the coins started with a high gold content, the alloy ąuickly deteriorated with the addition of morę and morę silver, until this too was debased with the addition of morę and morę base metal. Finalły, the last coins in this series were madę from cast bronze. Yet throughout this period, the change in the imagery and alloy proceeded gradualły. Even though the finał image of a few dots and a linę is completely unintelligible, its lineal descent from Galio-Belgie C can be traced. Given this, I wonder if those familiar with the local visual language were able to tell if it still rcpresented a horse and a face?

The key thing to notę here is the incremental change that took place from issue to issue. Each clearly refers back to the last, whilst also displaying a tiny but łimited degree of innovation. The coinage represents one long, related series. I cali this form of aesthetic ‘serial imagery’. This particular family of serial imagery condnued right up to AD 43 in the NE and SW coin series (Stage 1). However in the south-east this imagery gave way to a new series based on British L and Q, around the dme of the Gallic w ars (Stage 2). In the late first centry BC, this imagery also gave way, in its tum, to a totally new aesthedc dominated by innovadon and classical and naturalisdc imagery (Stage 3).

This earły tremendous degree of conservadsm has rarely been discussed per u. It b as if copying an original and then slightly modifying it, as one would in a gamę of Chinese whispers, requires no explanation. But it needs to be discussed. This degree of uniformity was totally alien to the innovauon which occured in Stage 3. In order to understand this change, we need to try to comprehcnd the different aesthetic valucs in society, and how they altered. How did people look at coins and perceive them?

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

00270 d021c6388981baccfa088288e9ff089 272 Montgomery Choice of Factors and Levels As noted in Table

Fall Obj Missing 1 Parts of w bole and labelPart is missingName_ ww.speechfun.com A iX /I M Myf 4

1 Introduction The topie of standardisation and customisation is an interesting issue which mixes th

32 LIBOR STEPANEK The excessive use of ICT and multimedia is also supported by the community-of-prac

29 (466) 52 The Viking Age in Denmark We have already mentioned the expansion of grasses, and it is

Its a Battle of Wills . . . AND LoVE Is ON THE Li ne! Rural switchboard operator Georgie Gaił is pro

4[1] Errors and Warnings Here is list of errors and warnings:!_VCD_mpeg�1 .mpv -* This is a Iow qual

362 (20) 335 FingerRings the form of a sexfoil, and which is likewise from London, forms part of the

Audit as a method of control and quality management evaluation In the management system of enterpris

Silberman�9 546 P5YCH0L0GY OF RELIGION AND APPLIED AREAS jective. In R. M. Sorrentino Sc E.T. Higgin

Voł 13 *V<? S, p 45-51)FATTY ACIDS COMPOSITION OF DROMEDARY AND BACTRIAN CAMEL MILK IN KAZAKHSTAN

więcej podobnych podstron