371 (18)

344

Dress Accessories

(ceramic phase 6), another from a deposit of the late 13th or early 14th century (ceramic phase 9), and a third from a deposit of the late 14th century (ceramic phase 11). The style of these purses is very simple but the way that they were cut out and stitched together differs, presumably dictated by the size of skin available.

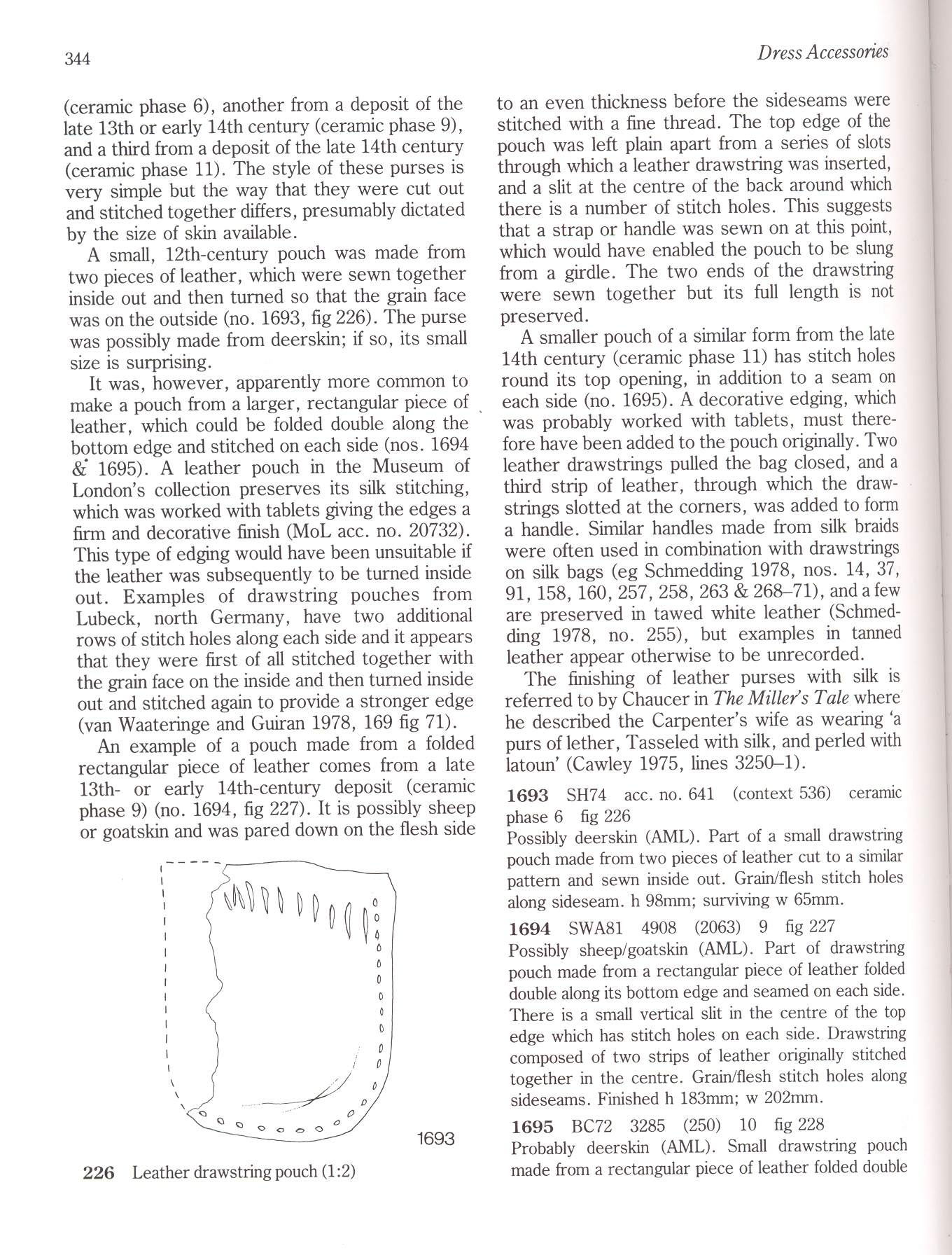

A smali, 12th-century pouch was madę from two pieces of leather, which were sewn together inside out and then tumed so that the grain face was on the outside (no. 1693, fig 226). The purse was possibly madę from deerskin; if so, its smali size is surprising.

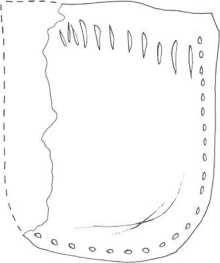

It was, however, apparently morę common to make a pouch from a larger, rectangular piece of leather, which could be folded double along the bottom edge and stitched on each side (nos. 1694 &* 1695). A leather pouch in the Museum of London’s collection preserves its silk stitching, which was worked with tablets giving the edges a firm and decorative finish (MoL acc. no. 20732). This type of edging would have been unsuitable if the leather was subseąuently to be tumed inside out. Examples of drawstring pouches from Lubeck, north Germany, have two additional rows of stitch holes along each side and it appears that they were first of all stitched together with the grain face on the inside and then tumed inside out and stitched again to provide a stronger edge (van Waateringe and Guiran 1978, 169 fig 71).

An example of a pouch madę from a folded rectangular piece of leather comes from a late 13th- or early 14th-century deposit (ceramic phase 9) (no. 1694, fig 227). It is possibly sheep or goatskin and was pared down on the flesh side

226 Leather drawstring pouch (1:2)

to an even thickness before the sideseams were stitched with a fine thread. The top edge of the pouch was left plain apart from a series of slots through which a leather drawstring was inserted, and a slit at the centre of the back around which there is a number of stitch holes. This suggests that a strap or handle was sewn on at this point, which would have enabled the pouch to be slung from a girdle. The two ends of the drawstring were sewn together but its fuli length is not preserved.

A smaller pouch of a similar form from the late 14th century (ceramic phase 11) has stitch holes round its top opening, in addition to a seam on each side (no. 1695). A decorative edging, which was probably worked with tablets, must there-fore have been added to the pouch originally. Two leather drawstrings pulled the bag closed, and a third strip of leather, through which the drawstrings slotted at the comers, was added to form a handle. Similar handles madę from silk braids were often used in combination with drawstrings on silk bags (eg Schmedding 1978, nos. 14, 37, 91, 158, 160, 257, 258, 263 & 268-71), and a few are preserved in tawed white leather (Schmedding 1978, no. 255), but examples in tanned leather appear otherwise to be unrecorded.

The finishing of leather purses with silk is referred to by Chaucer in The Mille/s Tale where he described the Carpenteris wife as wearing ‘a purs of lether, Tasseled with silk, and perled with latoun’ (Cawley 1975, lines 3250-1).

1693 SH74 acc. no. 641 (context 536) ceramic phase 6 fig 226

Possibly deerskin (AML). Part of a smali drawstring pouch madę from two pieces of leather cut to a similar pattem and sewn inside out. Grain/flesh stitch holes along sideseam. h 98mm; surviving w 65mm.

1694 SWA81 4908 (2063) 9 fig 227 Possibly sheep/goatskin (AML). Part of drawstring pouch madę from a rectangular piece of leather folded double along its bottom edge and seamed on each side. There is a smali vertical slit in the centre of the top edge which has stitch holes on each side. Drawstring composed of two strips of leather originally stitched together in the centre. Grain/flesh stitch holes along sideseams. Finished h 183mm; w 202mm.

1695 BC72 3285 (250) 10 fig 228 Probably deerskin (AML). Smali drawstring pouch madę from a rectangular piece of leather folded double

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

375 (18) 348 Dress Accessońes ribbon was then hemmed to the back of the pouch and the other oversewn

329a 302 Dress Accessories 201 Pins with different forms of solid heads from a&nbs

425 (10) 398 Dress Accessories surfaces. Many objects had evidence of tin coat-ing (colour pis 4G &a

84965 ms 034 RESEARCH HAS FAILED TO DISCLOSE ANOTHER METHOD CAPABLE OF THE SAME ASTOUNDING PHYSICAL

383 (13) 356Dress Accessońes early 14th century (Cook et al. 1969, 104 nos. L15-17). A further Engli

335 (29) 308 Dress Accessories 1517—21 TL74 (context 2515) ceramic phase 9:1516 Miscellaneous: Incom

343 (24) 316 Dress AccessońesTIN 1584 SWA81 acc. no. 2788 (context 2108) cera

420 (12) 393Metallurgical Analysis of the Dress Accessories Lead Lead Fig 266 Copper alloys c. 1270-

341 (27) 314 Dress Accessońes site acc. no. context ceramic hole diameter number

359 (16) 332 Dress Accessońes which to produce a finger ring, it is not a solitary example. Another

274 (42) Dress Accessońes 246 1078 805 1095 (A) mounts with fields of dots (1:1) (

276 (40) 248 Dress Accessońes because no indication has been recognized on them of the wearer’s adhe

278 (40) 250 Dress Accessories 1314 1311 SWA81 2186 (2055) 9 fig 160 Corroded

284 (41) 256 Dress Accessońes Hooked annular brooch Copper alloy 1338 SWA81 acc. no. 1493 (context

286 (34) 258 Dress Accessońes 166 Pentagonal, hexagonal and six-lobed brooches -odginał shapes resto

więcej podobnych podstron