421 (10)

394

IJress Accessories

Variations between/within object categories

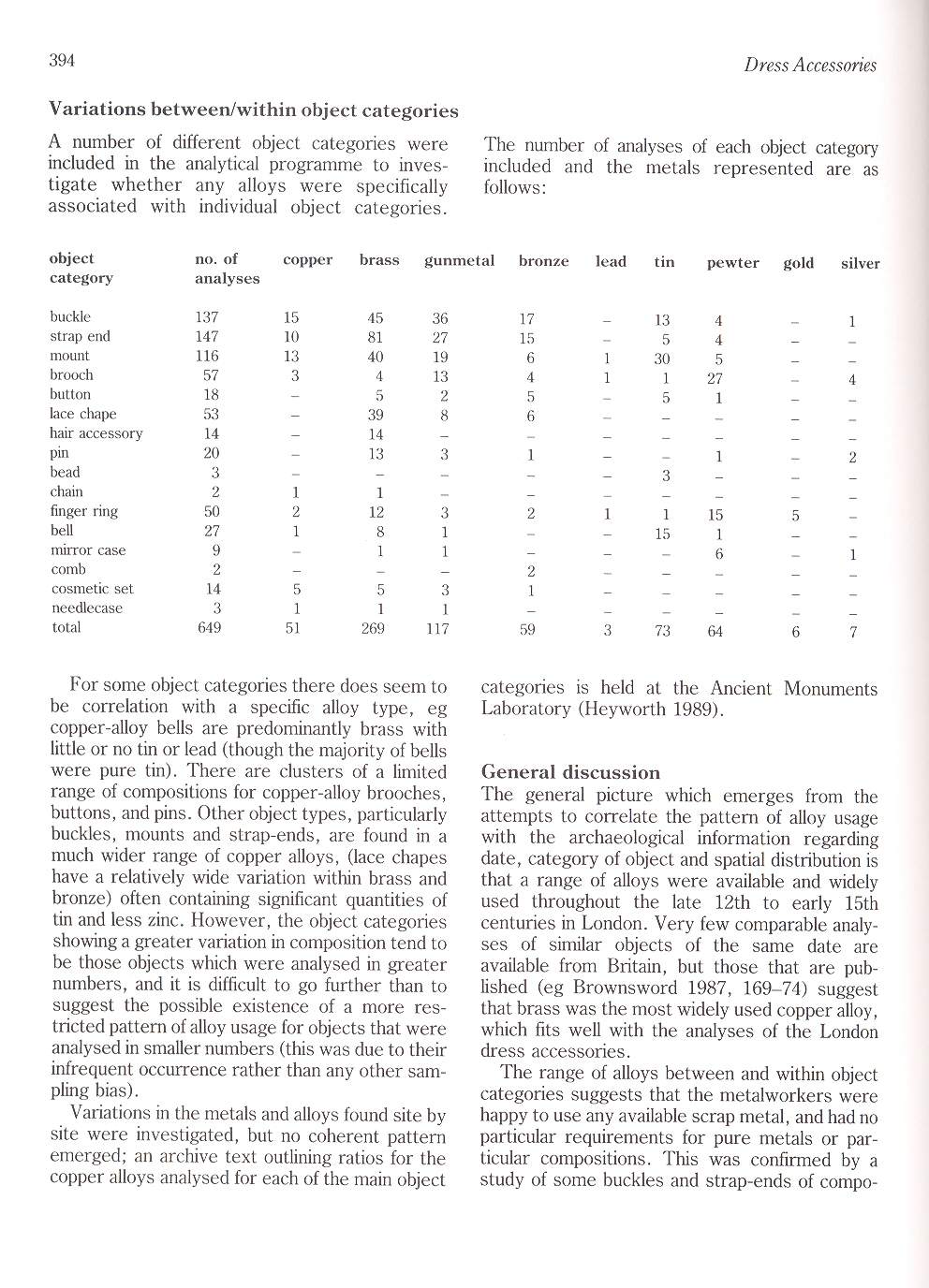

A number of different object categories were The number of analyses of each object category

included in the analytical programme to inves- included and the metals represented are as

tigate whether any alloys were specifically follows: associated with indiyidual object categories.

|

object category |

no. of analyses |

copper |

brass |

gunmetal |

bronze |

lead |

tin |

pewter |

gold |

silver |

|

buckie |

137 |

15 |

45 |

36 |

17 |

_ |

13 |

4 |

- |

1 |

|

strap end |

147 |

10 |

81 |

27 |

15 |

- |

5 |

4 |

- |

- |

|

mount |

116 |

13 |

40 |

19 |

6 |

1 |

30 |

5 |

- |

- |

|

brooch |

57 |

3 |

4 |

13 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

27 |

- |

4 |

|

button |

18 |

- |

5 |

2 |

5 |

- |

5 |

1 |

- |

- |

|

lace chape |

53 |

- |

39 |

8 |

6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

hair accessory |

14 |

- |

14 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

pin |

20 |

- |

13 |

3 |

1 |

- |

- |

1 |

- |

2 |

|

bead |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

3 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Chain |

2 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

finger ring |

50 |

2 |

12 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

15 |

5 |

- |

|

beli |

27 |

1 |

8 |

1 |

- |

- |

15 |

1 |

- |

- |

|

mirror case |

9 |

- |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

6 |

- |

1 |

|

comb |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

2 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

cosmetic set |

14 |

5 |

5 |

3 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

needlecase |

3 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

total |

649 |

51 |

269 |

117 |

59 |

3 |

73 |

64 |

6 |

7 |

For some object categories there does seem to be correlation with a specific alloy typc, eg copper-alloy bells are predominantly brass with little or no tin or lead (though the majority of bells were pure tin). There are clusters of a limited rangę of compositions for copper-alloy brooches, buttons, and pins. Other object types, particularly buckles, mounts and strap-ends, are found in a much wider rangę of copper alloys, (lace chapes havc a relatively wide variation within brass and bronze) often containing significant ąuantities of tin and less zinc. However, the object categories showing a greater variation in composition tend to be those objects which were analysed in greater numbers, and it is difficult to go further than to suggest the possible existence of a morę res-trictcd pattern of alloy usage for objects that were analysed in smaller numbers (this was due to their infrequent occurrence rather than any other sam-pling bias).

Variations in the metals and alloys found site by site were investigated, but no coherent pattern emerged; an archive text outlining ratios for the copper alloys analysed for each of the rnain object categories is held at the Ancient Monuments Laboratory (Heyworth 1989).

General discussion

The generał picture which emerges from the attempts to correlate the pattern of alloy usage with the archaeological information regarding datę, category of object and spatial distribution is that a rangę of alloys were available and widely used throughout the late 12th to early 15th centuries in London. Very few comparable analyses of similar objects of the same datę are available from Britain, but those that are pub-lished (eg Brownsword 1987, 169-74) suggest that brass was the most widely used copper alloy, which fits well with the analyses of the London dress accessories.

The rangę of alloys between and within object categories suggests that the metalworkers were happy to use any available scrap metal, and had no particular reąuirements for pure metals or par-ticular compositions. This was confirmed by a study of some buckles and strap-ends of compo-

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Using MySQL and memcached with Ruby There are a number of different modules for interfacing to memca

QUESTION NO: 10 When files are transferred between a host and an FTP server, the data is divided int

421 2 10.3. Dualność 421 Znaleźć minimum wyrażenia giy)=yti> yTA >cT. (10.3.4) przy

425 (10) 398 Dress Accessories surfaces. Many objects had evidence of tin coat-ing (colour pis 4G &a

431 (10) 404 Dress Accessońes —, 1987 ‘Report on the Composition of the Ingots and Axle-Cap’, in Mea

421 2 10.5. NASTAWNIE BLOKOWE I TECHNOLOGICZNE wskaźniki (mierniki). Na pulpicie sterowniczym odwzor

403 (10) 376 Dress Accessońes only 6d per lb (Staniland 1986, 240). The painting and gilding of boxw

407 (10) 380 Dress Accessońes -scoop soldered seamline TYPE I Type II - as above but with a bevelled

419 (10) 392 Dress Accessories cases, though it is likely to have been present. Brass mount no. 935

28582 page28 (2) Lubrication and Maintenance Services An interval of 10 000 km (6000 miles) between

PRODUCT RANGĘ 2021 Up to +10% IW b KART ACCESSORIES O RECOVERY TANK CHASSIS PR0TECT10N PRODUCT

When comparing and contrasting the similarities and differences between bridges and switches, which

IMG#10 22 Associative Principles and Democratic Reform public power and of the devolved associationa

więcej podobnych podstron