87 (108)

168 The Viking Age in Denmark

North Sea and thc Baltic, and also of craft activities. In these towns the first Christian churches datę from some time in the ninth century.

The towns rcceived supplies from the countryside, which bccame morę necessary in the tenth and eleventh centuries, when towns were established further to the north and to thc cast, and turned into regional centres with institutions such as bishoprics and mints. In the tenth century fortresses of thc Trelleborg type were erected; apart from being military strongholds around what we consider to be the west Danish State centrcd on Jelling in mid-Jylland, they may have served, among other things, as toll-stations and as sites for the manufacture of artefacts of costly metals.

These economic institutions, of course, were not functioning in a social limbo. The carly Iron Age societies were apparcntly chiefdoms, sometimes quite extensive but with limited social stratification, though the magnates held many prerogatives. In 8(X), in a still morę stratified society, the central Danish provinces apparently held the leadership, for instance in the warfare against the Franks. In these areas the germ of land rights is apparent, these no longer being only part of the traditional family structure. For instance, folio wers may have received grants from the king in return for military services, and a petty system of Łvassalage’ was established. Other royal ‘ofFicials’ comprised the counts of the towns and the commandants of the fortresses.

In the tenth century the system of vassalage was expanding, as is shown by the runestones, which demonstrated publicly the new rights of land; vassalage is also elear from certain types of burials which follow the border around the State in west Denmark with its town economy and magnate farm economy. With the breakdown ot traditional leaderships and their economic foundations, caused by the strength of the kingship and its dependents, the stage was set for thc old magnates to enter the new social system, turning corporate rights into morę private ones. This development may have been facilitated already by the development in the ninth century of the idea of one supremę kingship for the whole country.

The strength of the king of Denmark, of the Jelling dynasty, is demonstrated in 1000 A.D. in the expansion of military settlements towards the eastern provinces. But the apparatus directed itselfat even larger enterprises, culminating in the conqucst of England, even if this was only an episode. Soon the runestone documents disappear, and rights of land are in the hands of a new establishment, set apart from the rest of the population. In the State, these personages, along with the Christian institutions, themselves major owners of land, kept a check on the royal power.

The regulated village and magnate farm economy was well suited to the devclopment of the towns, with their need both for foodstuffs and for a wealthy outlet for their products. International connections, on the level of intemational trade, may have played a considerable role herc. For instance, criscs in the supply of silvcr, a crucial means of payment for services, may have increascd the numbcr of grants ofland and have thereby added, albeit unwittingly, to the changes in Danish society that occurred in the Viking Age. The first crisis in the supply corrcsponds to the raids in western Europę of the late ninth century, and herc the social system is attempting to ‘export’ its problem, perhaps also under pressure of a minor ninth-century climatic re-cession. The serious crises of the mid-tenth century, however, did not lead to such measures. Instead, a new society was being created based on stable rural institutions and with fortresses and towns serving as centres of control and supply. This society of the tenth century, expanding to all provinces in about 1000 A.D., we cali the State of Denmark. The germs of its institutions are already found in the ninth century, and perhaps even earlicr, but the system did not function as a whole until a later datę.

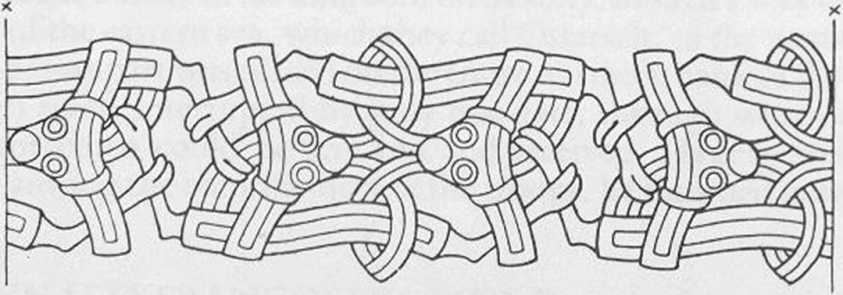

We have attempted to describe this ‘sccondary’ State development as fully as possible. The available data is measured against a wride array of factors seen in conjunction and in relation to the functions of society. But in spite of all reductions the picture is both complex and open to discussion. Ironically, the Vikings themselves would never have considered their age complex. They seem to have been a practically minded people, though they possessed a strong interest in anta-gonisms. Their art, or whatever they might have called it, always fills up the whole space available with dynamie shapes (cf. Fig. 57).1 No room is left for the uncertain, apart from what is really uncertain in the fate of man and of the world. Christianity, however, attempted to close this mental door.

Figurę 57 Animal-ornament from whip-shank (silver) in the Ladby ship-burial. Scalę 2:1. (After Thorvildsen)

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

57 (213) 108 The Viking Age in Denmark Platę IV. Silvcr and copper dccorated spurs, length about 21

58 (195) 110 The Viking Age in Denmark Platę VI. Sample from late tenth-century silver-hoard at Taru

60 (189) 114 The Viking Age in Denmark Platc X. Ship-sctting and runestonc (on smali mound) at Glave

62 (179) 118 The Viking Age in Denmark Plato XIV. Iron tools from a tenth-ccntury hoard atTjclc, nor

63 (170) 120 The Viking Age in Denmark % Platę XVI Pagc with illustration of an English manuscript f

64 (171) 122 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurc 30 Distribution of wealth in three cemeteries as measu

66 (160) 126 The Viking Age in Denmark have becn fouhd (Figs 32-3).7 They stem from thc same provinc

68 (153) 130 The Viking Age in Denmark two tortoise bucklcs to reprcsent wornen of high standing, th

69 (151) 132 The Viking Age in Denmark heavy cavalry burials, fincr wcapon graves of thc simple type

70 (150) 134 The Viking Age in Denmark cemetcry at Lejre on Sjaelland a dccapitatcd and ticd man was

74 (134) 142 The Viking Age in Denmark 5C~ł silver 800 900 kxx) A.D. Figurę 37 Fluctuations in che r

75 (129) 144 The Viking Age in Denmark Figurę 38 Average weight ofthesilver-hoardsofthe period 900 t

27 (504) 48 The Viking Age in Denmark Europcan meteorological data for earlier per

29 (466) 52 The Viking Age in Denmark We have already mentioned the expansion of grasses, and it is

30 (454) 54 The Viking Age in Denmark touch, so the political developmcnt we have described in previ

31 (444) 56 The Viking Age in Denmark pig SO- A horse B 50- 50 cattle 50" sheep (Qoat) Figurę 1

32 (433) 58 The Viking Age in Denmark and from a rurąl scttlemcnt, Elisenhof, less than fifty kilome

78 (124) 150 The Viking Age in Denmark Figuro 41 Danish coins, c. 800 to 1035 A.D. (1) = ‘Hcdeby’ co

79 (124) 152 The Viking Age in Denmark Roskilde, in the newly won provinces, were the most important

więcej podobnych podstron