essentÊrving°76

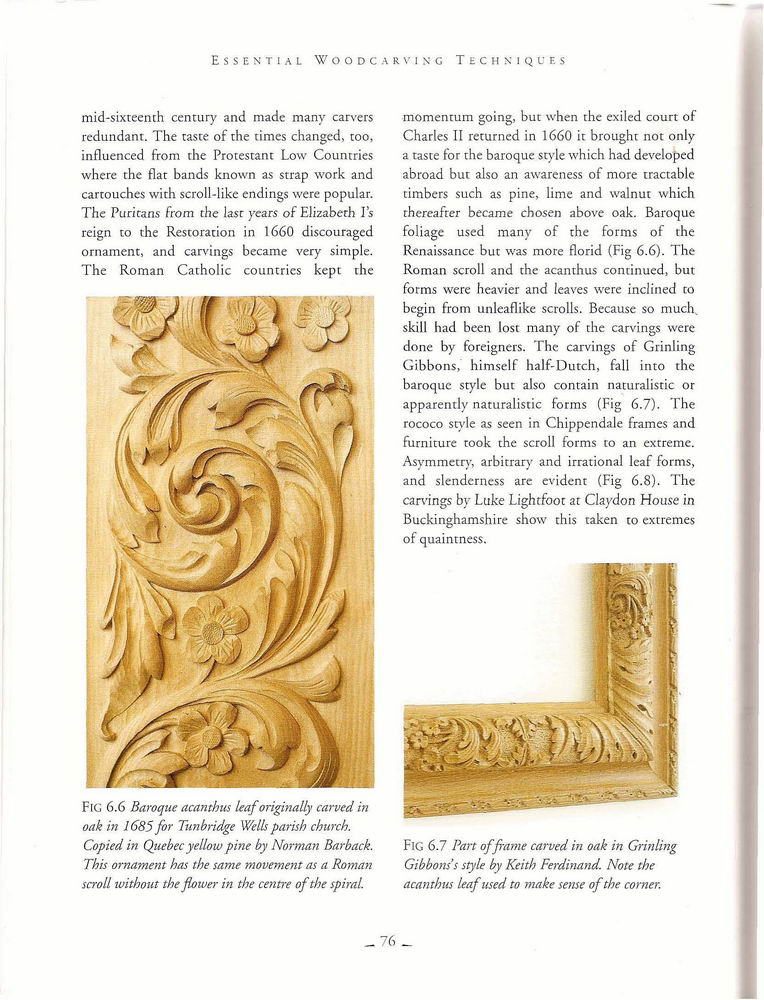

Fig 6.6 BaroÄ ue acanthus leaf originally carved in oak in 1685for Tunbridge Wells parish church. Copied in Quebec yellow pine by Norman Barback. This ornament has the same mooement as a Roman scroll without the floiuer in the centre of the spiral.

mid-sixteenth century and madc many carvÄrs redundanc. The taste of the timcs changcd, too, influenced from the Protestant Low Countries whcre the fiat bands known as strap work and carrouchcs wirh scroll-likc endings wcrc popular. The Puricans from the lasr years of Elizabeth Is reign to the Restoracion in 1660 discouragcd ornament, and carvings became very simple. The Roman Catholic countries kept the

momentum going, but when the exiled court of Charles II returned in 1660 it brought not only a taste for the baroque style which had developcd abroad but also an awareness of morÄ tractable timbers such as pine, limÄ and walnut which thcrcafrer became chosen above oak. BaroÄ ue foliage used many of the forms of the Renaissancc but was morÄ florid (Fig 6.6). The Roman scroll and the acanthus continued, but forms were hcavier and ieaves were inclined to begin from unleaflike scrolls. Because so much. skill had been lost many of the carvings were done by foreigners. The carvings of Grinling Gibbons, himself half-Dutch, fali into the baroÄ ue style but also contain naturalistic or apparently naturalistic forms (Fig 6.7). The rococo style as seen in Chippendale frames and furniture took the scroll forms to an extremc. Asy m metry, arbitrary and irrational leaf forms, and slendcrncss arc evident (Fig 6.8). The camngs by LukÄ Lightfoot at Claydon House in Buckinghamshire show this taken to extremes of Ä uaintness.

Fig 6.7 Part offrame carved in oak in Grinling Gibbonss style by Keith Ferdinand NotÄ the acanthus leaf used to make sense of the corner.

_ 76 _

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

essent?rving?75 C a r vin c Traditional Foliace Fic. 6.4 Copy offijteenth-century vine leaf running

carving?ce2 32 RangÄ of Expressions These studies show a grinning face carved in wal-nut, Fig. 65, a

essent?rving?74 E S S E N T I A L W O O D C A R V I N G T E C H N I Q U F. S Fig 6.2 Oak leaf copied

essent?rving?04 E S S E N T I A L W O O D C A R V I N G T E C H N I Q V E S (Fig 9.20) bur could hav

essent?rving?15 Fig 10.16 The smali beech bowl being held in a caruers chops with a bar across its m

essent?rving?31 C a r v i n c; i he HumaÅ Figur f. Fic; 12.7 Muscles at the back of the body Fig 12.

fig 6 1 e FigurÄ 6-1 Hospitalizations for eating disorders1 in generaÅhospitals per 100,000 by age g

fig 6 2 e FigurÄ 6-2 Hospitalizations for eating disorders in generaÅ hospitals per 100,000 by contr

image001 The most ezdting fiction of our time! *13 in âThe most celebrated âAll-OriginaP senes in Sc

image001 11 IN âTHE MOST CELEBRATED ALL-ORIGINALâ SERIES IN SCIENCE FICTION!â Science Fiction Book

Fig. 1 Age distribution of 73 butchers in western Sweden 1981 Neck £ Åbowi Low

S5002146 gp c [1 frag., Fig. 20:6), D [4 1 Fig. 20:2,3], H [1 frag.]. >n was carried out in the a

S5002146 gp c [1 frag., Fig. 20:6), D [4 1 Fig. 20:2,3], H [1 frag.]. >n was carried out in the a

10 Fig. 2. Degree of food self-supply in surveyed households Source: Authorsâ

calibre cover (73) NATURAL ACTSA SIDELONG VIEW OF SCIENCE AND NATURÄ âA TOUR DE FORCE OF ORIGINAL TH

522 M. Daszykowski eÅ al. To illustrate this, Fig. la shows the original chromatogram of sample 12 (

wiÄcej podobnych podstron