8589356912

362 THH SHORT WAVE MAGAZ1NE

A NOVEL

BAND-SWITCHED ATU

YESTERDAY’S APPROACH, BUT A HOME-BREWER’S DELIGHT-AND VERY EFFECTIYE, TOO

M. A. SANDYS, G3BGJ

THE type of aerial tuning unit known as the ‘Collins Coupler’ first becamc popular in amateur radio just before World War 2, although it had its origins somewhat earlier. Although the name ‘Collins Coupler’ seems to have been dropped, the Circuit is still widely used for feeding random length wires and has been described many times. The justification for yet another article is that the version to be described incorporates some unusual features not previously presented, as far as is known, in the amateur radio literaturę.

Of all the previous articles in Short Wave Magazine dealing with this type of ATU, possibly the best was “Aerial Hints, Tips and Ideas” by ‘Old Timer’, which appeared in the February, 1962 issue. Old Timer particularly stressed the importance of getting the number of turns in the link right, and correctly positioning the link for optimum output, something ignored in most articles on the subject. Old Timer’s reflections were summed up thus: “Now you will sce why I do not approve of band-switched ATUs .. . you can’t get the link in the right position for all conditions ... but if you use a separate coil for each band you can, by experiment, get the turns and position right for each coil”. To someone of a curious and cantankerous disposition Old Timer’s statement naturally invited the retort, “Why can’t one vary the number of turns in the link or alter its position in a band-switched atu?” it was jn the contemplation of this question that the design presented here first took shape. The answer, it would seem, is that it can be done but it requires extra effort on the mechanical side and should only be attempted by those who like doing things the hard way!

The Moving Link

On first examination there may seem to be a problem in placing a movable link on a band-switched coil because, if the link is wound around the outside of the coil in the traditional way, any attempt to slide the link along the coil will quite naturally be obstructed by the leads going away to the band-change switch. However there is no reason why the link should not move inside the coil in the manner of a piston in a cyclinder; neither is there any reason why the link coil itself should not be tapped and switched to provide a variable number of turns. The leads going to the link may be madę rigid and thereby serve as a rod to push the link into the coil. However, knowing what is required is one thing, finding a mechanical solution is quite another! How best to implement the scheme is left as an exercise for intending constructors (should there be any such adventurous spirits!) because it depends on a number of factors, ranging from the components available to one’s skill in metal-work. Only the generał principle of the coil mechanism is therefore given and this is shown in Fig. 1.

Although the actual unit contains some extra mechanical refinements to ensure smooth movement of the link, nothing was so complicated that it could not be done on the kitchen table using a hacksaw, file, and hand-drill. If assurance is required that the design is entirely practical, the writer’s unit was built as long ago as 1965 and is still in use today.

Mechanical Details

The Circuit diagram of the ATU is shown in Fig. 2. Morę will be said about this later, after the mechanical aspects have been considered. Those components of the Circuit diagram which play a part in the variable link may easily be recognised in the sketch of Fig. I as the numbering is the same in each case.

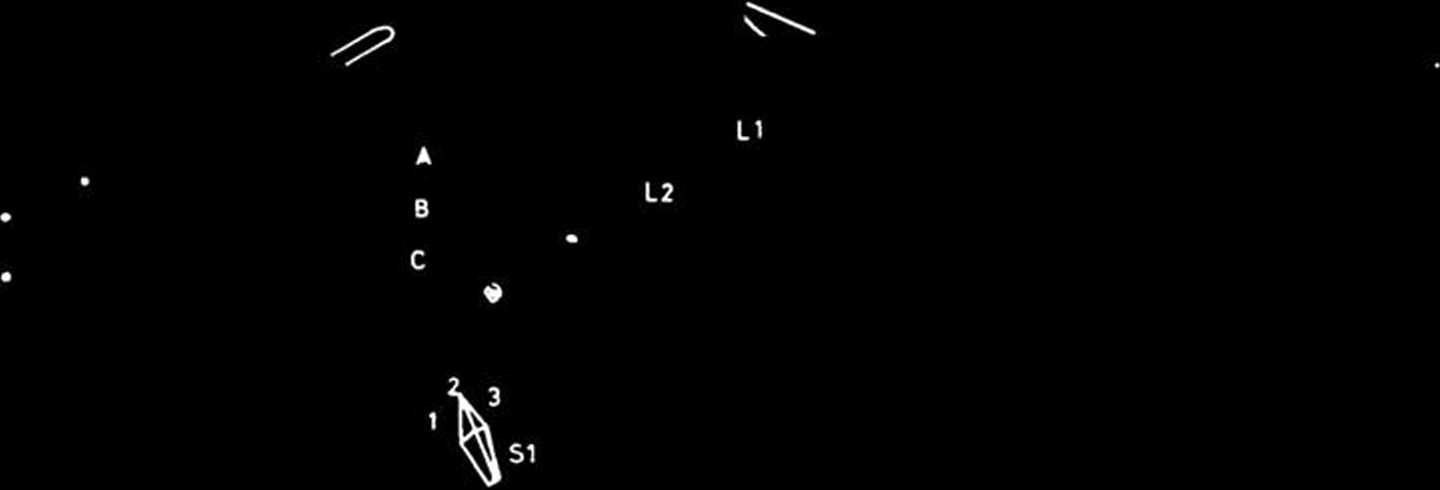

Referring to Fig. 1, the three rods A, B, and C which make contact with, and support, the link are free to slide in the holes drilled in two insulated brackets which are placed sufficiently far apart to prevent the link from sagging when fully extended. The brackets are of V*" thick perspex. Ordinary bicycle spokes are used for the rods, as they have the necessary rigidity and have a convenient thread at one end. The link coil, of 14 s.w.g. copper wire, is shaped to just fit into the main coil, and the turns are threaded through three smali perspex separators, which make it impossible for the link and the main coil turns to come into contact. The centre rod B goes to a tap

Fig. 1 MECHANICAL DETAILS OF THE VARIABLE LINK

Fig. 1. Showing how the link is moved by the sliding control, while the number of turns in the link is varied by SI.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

March, 1980 THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZ1NESouth Midlands HAIMTS - YORKS - DERBYS - LINCSYAESU MUSEN UK

Volume XLI THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZ1NE 363 Volume XLI THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZ1NE 363 from the met

372 THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZ1NE September, 1983 372 THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZ1NE September, 1983 ,i

September, 1983 THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZ1NE FOR THE BEST IN AMATEUR RADIO 116 DARUNGTON STREET EAST,

12 IHE SHORT WAVE MACAZINE March, 1980trancoM /T S HE AND SHOULD BY NOW BE EX

18 THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINE March, 1980 DATOIUG ELECTRONICS LIMITED• YOURDXPO 3

Yolume XXXVIII THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINELOWE ELECTRONICS Ltd Morse Keys-HK 708

Volume XXXVIII THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINE37CLIJBS ROUNDUPBy *C/ub Secretary* HOW nice ii is 10 tum to o

Yolume XXXVIII THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINE39 Names and A ddresses of Club Secretaries reporting in this

Volume XXVII THE SHORT WAVE M A G A Z I N E45 I mAT LAST!! A two-metre FM handy Talkie from the famo

March, 1980 THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINEC.B. ELECTRONICSUNIT 3, 771 ORMSKIRK ROAD, PEMBERTON, WIGAN, WN5

Yolume XXXVIII THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINE7 UNITED KINGDOM WATERS & STANTON ELECTRONICS FDK

835 857 P0835 Clutch pedał position (CPP) switch B - high input Wiring short to positive, CPP switch

September, 1983 THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINE - f2 . i * U8C318988 •r -- ...ńlhebrandtlialgiwei ToutlKbeit

Volume XLl THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINE 347 I* •J ^ ^ » vac«u •• ****** YAESU a • • o *

THE SHORT WAVE MACAZINE Sepiember, 1983 (OR DOWN)YOUR FREOUENCY! OUR RANGĘ OF SOUD-STATE LINEAR

Volume XLl THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINE 349 wMAIL«S5P^he brIdhurst way THE EASY WAY IXJ

Volume XL! THE SHORT WAVE MAGAZINE 353 FOR THE RADIO AMATEUR AND AMATEUR RADIO / EDITORIALBelgi

II THE SHORT WAVE MACAZINE Sepiember, 1983LOWE SHOPS LOWE ELECTRONICS IN MATLOCK, located on the Che

więcej podobnych podstron