CHRONOLOGY

CHRONOLOGY

reigned

17

years.

In this way the

of the years of

reign in the lines of Israel and Judah, according to the

synchronisms, would be increased in each case by two

years-for Jehoahaz would have reigned, according to

the synchronism, 16 years instead of

and Jehoash

39 instead of

the traditional numbers would

undergo no alteration.

Even without this slight

dation-adopted in the

edition of the

LXX,

and

demanded by Thenius,

and Kamphausen

-it is apparent that it is the sum of the

of reign that forms the basis on which the synchronistic

are calculated.

In this process, however,

though the individual

have not been disregarded,

it has been impossible, especially in the case of the

kings of

N.

Israel, to avoid important variations.

Care however has been taken not

to alter the synchronism of

I t is

of note that the following reqnirements

are satisfied :-Jerohoam’s reign runs parallel with those of

Rehohoam and Ahijah

(I

K. 14 15

7)

is king during

reign of Asa

(I

K.

survives Ahah

and Ahaziah and reigns contem

with Jehoram

of Israel

K.

3

the deaths of Jehoram of

Israel and Ahaziah of Judah fall

the same year

K.

Amaziah and Jehoash of Israel reign contemporaneously

( z

K.’

14

and

is a contemporary of Jotham and Ahaz

( z

K.

Although the synchronistic dates have thus not been

attained without regard to tradition, they are obviously,

as

to the youngest parts of the text,

not

a

standard for chronology. They apply to the past a

method of dating with which it was quite unacquainted.

This is true not only of the practice, which could never

be carried out in actual life, of connecting the years of

one kingdom with reigns of kings in a neighbouring

kingdom, but also of the methodical practice, pre-

supposed in such

a

of indicating in an exact

and regular way the years within one and the same

kingdom, by the years of reign of its king for the time

being. In such texts as we can, with any confidence,

assign to pre-exilic times, we find nothing but popular

chronologies associating an event with

some other important event contem-

porary with it (cp Is.

6

I

20

I

).

The few dates according to years of

kings given in

history (as,

I

K.

may be ignored.

They are too isolated, and must

rest

in the writings and portions which treat of the

latest pre-exilic times) on subsequent calculation, or be

due to interpolation (cp also the dates introduced by

the Chronicler in deference to the desire felt at a later

date for exacter definition of time, of which the Books

of Kings still knew nothing

:

Ch.

and

especially

16

1)-though it is perhaps possible that,

even without there being

a

settled system, some pro-

minent events might, occasionally and without set

purpose, be defined by years of reign.

In any case,

dating by native kings must be regarded

as

at least

older than the artificial synchronism between Judah and

Israel.

Dating by the years of kings was thus never

tematicallv used bv the Hebrews so

as

thev had

kings.

The;

this

useful method from the Babylonians,

and

introduced it into their

his-

~

~~~~

~~~

~.

~~~~~

~~~~~~

_ ~ ~ _

torical works compiled during the exile (cp Wi.

A T

especially pp. 87-94).

Thus

the question

how the

dealt with the year of a king’s death

whether they reckoned the fraction of a year that

remained before the beginning of the next year to the

deceased king, or made the first year of the new king

begin at once-disappears.

There can be no doubt

that the synchronisms, as well as the dates and years

of reign in general, presuppose the Babylonian method

(the only satisfactory one), according to which the rest

of the year in which any king died was reckoned to the

need take no account of the indeoendent narratives of

C

HRONICLES

traditional years

5);

they do not agree even with the

Whether the account

is

correct need not here be considered.

last of his reign, and the first year of the new king was

the year at the beginning of which he already wore

the crown,

By giving up the synchronisms we are thrown back

for the chronology of the monarchy

on

the sums of the

years of reign of the individual kings.

The hope of finding in these numbers

trustworthy material for chronology, and

thus solving the singular equation

about

242

Israelitish years represent

Judean years, could he

realised only on one condition. One might simply sub-

tract the

242

Israelitish years from the total for Judah, and

regard the

of 18

as

falling after the conquest

of Samaria.

Nor

is

there anything in the synchronism

to prevent this operation, for that may have started from

an incorrect calculation in putting the fall of Hoshea

as

late as the reign of

A

clear veto, however, is

laid

on

procedure on other grounds.

If we subtract

the superfluous 18 years ( 6 years of Hezekiah and the

last

of Ahaz) from the total for Judah, all that is left of

Ahaz’s reign parallel with the Israelitish years of reign

is the first 4 years. Therefore Pekah, who was murdered

nine years before the

of Samaria

K.

must, at

the accession of Ahaz, have been already five years dead,

which is impossible, since, according to

this

king was attacked by him.

The expedient of simple

subtraction, therefore, fails the embarrassing equation

remains, about

242

Israelitish years 260 Judean

:

nay,

since no objection can be raised against the contem-

poraneousness of the deaths of Jehoram of Israel and

Ahaziah of Judah,

Israelitish years=

165

Judean.

If the totals are thus unequal, very great inequalities

appear, naturally, in the details. Efforts have been

made to remove them but this has not been achieved

in any convincing way.

15 5

states that during the attack of leprosy from

his

Azariah suffered in the last years of his life,

Jotham was over the palace and judged the people of the land.’

Even

were we to found

this statement the theory that the

years of reign of father and son that ran parallel t o each

other

were counted twice over in the

and 16 assigned

to

their respective reigns, and also

to

suppose that during all

these

years the father was still alive, there would still remain

744

Israelitish

Judean.

Mistaken attempts of this kind are, moreover, the less

to be taken into consideration that, as will appear

even the lowest total of

years for the interval from

Jehu to the fall of Samaria is more than

years too high.

From

all this it results that the individual numbers of

years of reign, as well as the totals, are untrustworthyand

useless for the purposes of a certain chronology, even if

it be admitted

within certain limits or in some

points, they may agree with actual fact.

The untrustworthiness of the numbers

becomes plainer when the principle ac-

cording to which they are formed is

clearly exhibited.

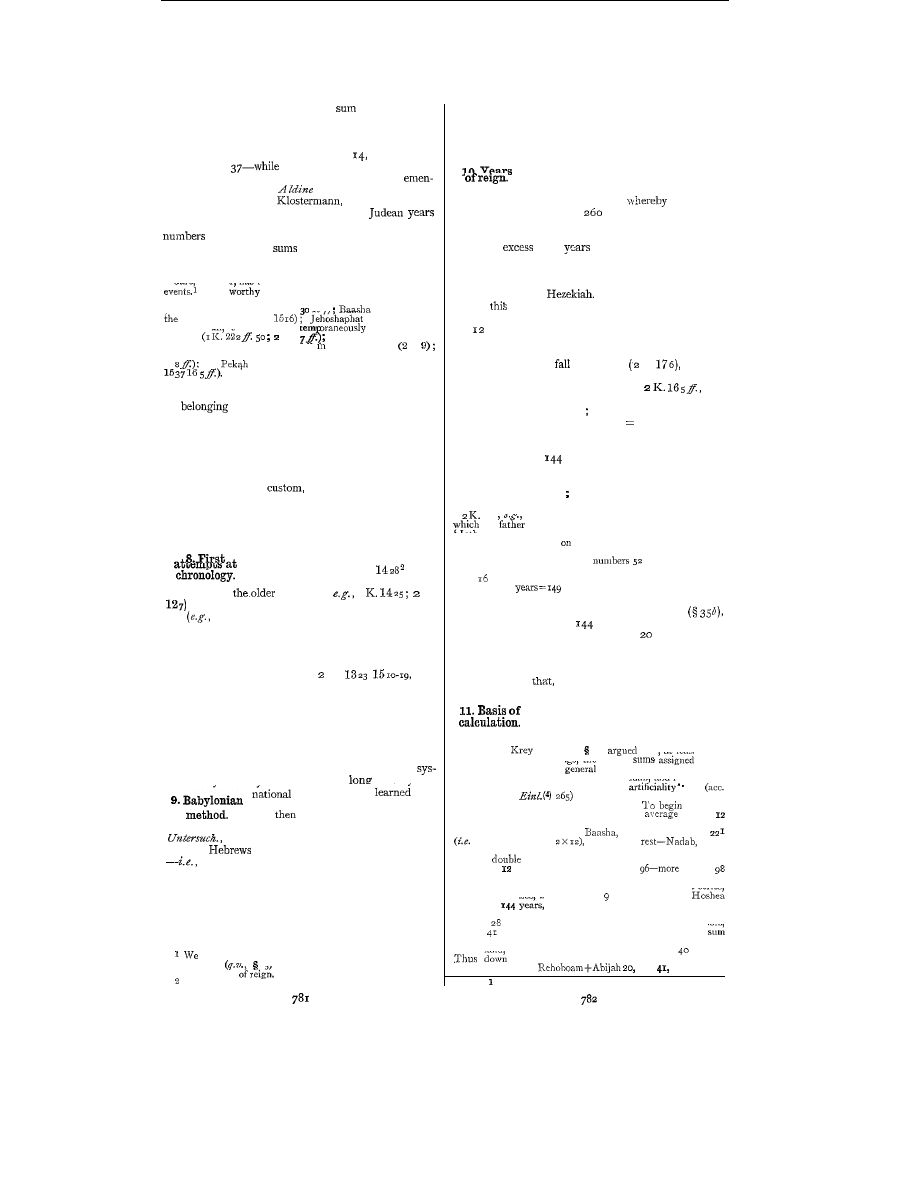

In 1887

E.

(see below

85)

that at least

in the

case of the Israelitish kings ’the several

to

the

respective. reigns rest in

on an artificial fiction.

H e

then thought that the series of kings of Jndah and indeed those

also of the house of Jehu, ‘show no such

hut

t o

Bleek-We.

he soon observed a playing with

figures

also

in the items for Judah.

with the

kings of Israel down to Jehoram, we find an

reign of

years. I n the case of Omri and Jehoram this is the exact

nnmher, whilst for Jerohoam,

and Ahab we ‘have

in round numbers

and for the

Elah

and’ Ahaziah (the immediate successors of the kings provided

with the

period)--2 years each. This is as if we had 8

kings with

years each, making a total of

exactly

years. Moreover, the totals for the first and the last four of

these are each almost exactly 48. In the next part of the series

as We.

emphasises we have for the kings from Jehu to

a

total of

which makes an average of 16 for each.

One might also urge the remarkable fact that, even

as

Jehu

with his

years reigned ahout as long as his two successors

so

the

years

of Jerohoam

11. also exactly equal the

of the reigns of his successors.

In the Judean line, on the

other

hand a similar role is played by the figures

and 80.

to

the destruction of Samaria in the 6th year of

Hezekiah, we have

Asa

Jehoshaphat

Strictly, Baasha has exactly 24 assigned him.

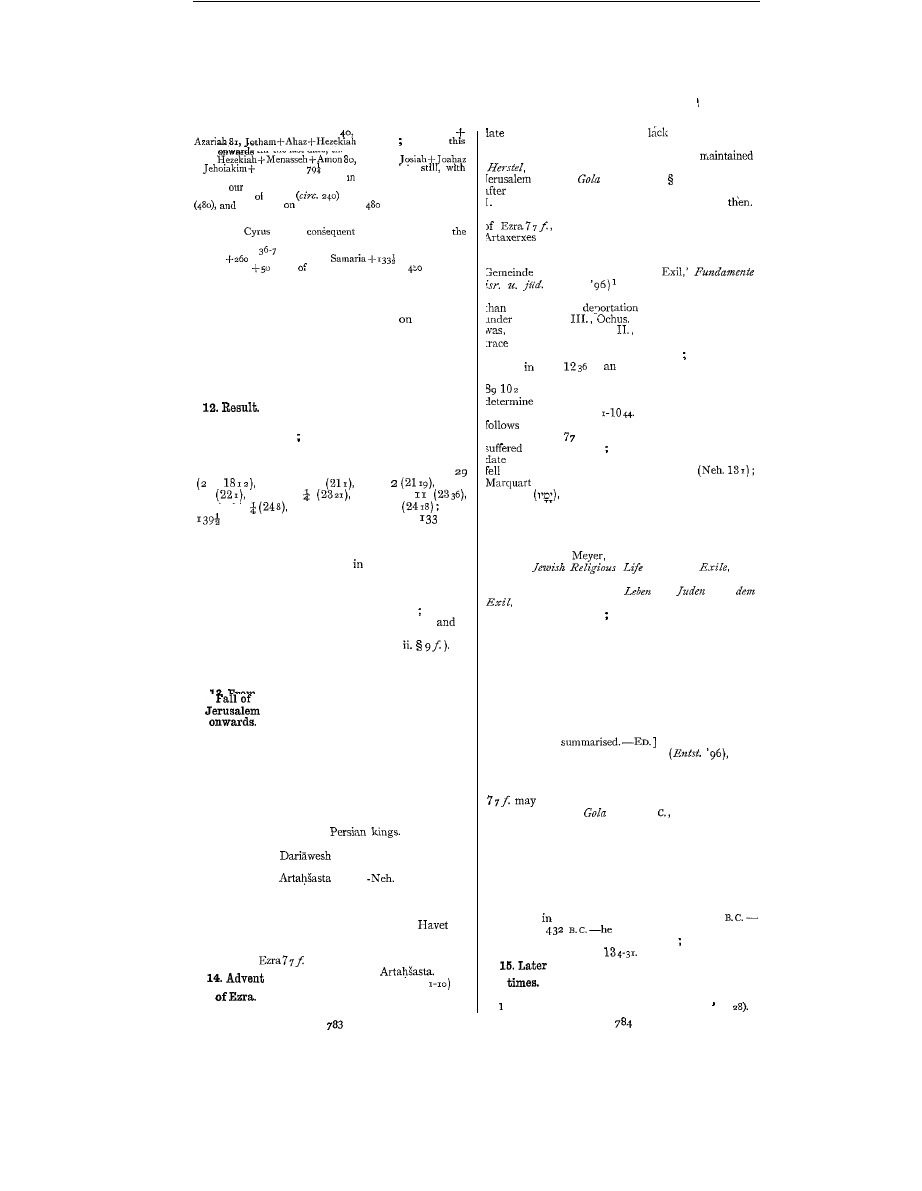

CHRONOLOGY

+

Jehoram

+

Ahaziah

+

Athaliah

Jehoash

40,

Amaziah

38

years and

from

point

till

the last date

the

37th year

of

Jehoiachin,

we

have

and

also

+

Jehoiachin

years:

If

we

might

Kamphausen,

be

inclined

to

find

all this only a

freak

of

chance,

suspicion would be raised

on comparing the

total

for

the kings

Israel

with the number

in

I

K.

6

I

still

more

observing

that

is also

the

total of

years

from the

building

of

the temple of Solomon

to

the begin-

ning of a new

epoch-the epoch that opens

with the

conquest

of

Babylon hy

and

the

possibility

of

founding

second

Theocracy and

setting

about

the

building

of the

second

temple. (The

years

of

Solomon from

t h e

building

of the

temple

years,

to

the

fall

of

years,

t o the

fall

of

Jerusalem

years

the

Exile, give exactly

years )

There ran hardly, then, be any mistake about the

artificiality

of

the total as well as of the various

items. If so, the origin of the present numbers for the

years of reign of the individual kings,

which the

synchronistic notices are founded, must fall in a

period later than the victory of Cyrus over Babylon,

and chronology cannot trust to the correctness of the

numbers.

For all that, it may be conjectured the numbers in

individual instances are correct; but which are such

cases, can be known only in some way

independent of the numbers. Sometimes,

indeed, the narrative of Kings or a prophetic writing

can

decide the point but without help from outside we

could not

go

far.

I n itself it cannot be more than

probable that the last kings of Judah appear with the

correct numbers. These numbers give Hezekiah

K.

Manasseh

55

Amon

Josiah

31

Jehoahaz

Jehoiakim

Jehoiachin

and Zedekiah

11

years

thus,

years in all, embodying

an

estimate

of

years

from the fall of Saniaria to the conquest of Jerusalem.

Thus, the earliest that the dates according to years of

kings can lay claim to consideration

is

in Jeremiah and

Ezekiel. Here grave mistakes

retrospective calcula-

tion (for even they rest

on

that) seem to be excluded by

the nearness of the time.

Naturally no account can be

taken of the statements of the Book of Daniel, which

did not originate till the second century

B.C.

it knows

the history of the fall of the kingdom of Judah

of

the exilic period only from tradition, and cannot be

acquitted of grave mistakes (see D

ANIEL

,

For the last period, reaching from the fall of Jerusalem

to the beginning of the Christian era, we have in the

Hebrew

O T

itself but few historical re-

cords. Beyond the introduction of the law

in the restored community the historical

narrative does not conduct

us.

For the

short interval preceding it we are referred

to the statements in the prophets Haggai and Zechariah

and in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah.

These, how-

ever, show that the Jews had learned in the interval

how to date exactly by years of reign.

The writings

mentioned give dates by years of the Persian kings.

All difficulties in the way of a chronology of this period,

however, are not thus removed.

The names Darius and

Artaxerxes leave us to choose between the several bearers

of these names among

the

Hence both

the first and the second of the three Dariuses have been

regarded as the

mentioned in the OT, and

even all three Artaxerxes have been brought into con-

nection with the

of Ezr.

Then, again,

the transpositions and actual additions that the Chronicler

allows himself to make increase the difficulty of knowing

the real order

of

events.

I n the case of Darius,

indeed, only the first can, after all (in spite of

and

Imbert), be seriously considered.

The chief interest, accordingly, lies in deciding as to

the date in

which sets the return of Ezra in

It is

to be noted that this passage

( 7

has

been revised by the Chronicler (see

E

ZRA

A

N

D

N

E

HE

M

I

A

H

,

Books of), and in both verses the

the seventh year of

C

H

RO

N

O

L

O

GY

is

open, from its position' or

of coniiection, to

he suspicion of not being original. Kosters accordingly,

eaving this datum wholly out of account,

'94) that Ezra made his first appearance in

with the

(see I

SRAEL

, 57) immediately

Nehemiah's second arrival there, while Artaxerxes

was still on the throne, and introduced the law

Jan Hoonacker,

on

the other hand, accepted the datum

but believed that it had reference to

II.,

and accordingly set down the date of

Ezra's arrival as in the seventh year of that king

397

B . c . ) .

[Marquart ( ' D i e Organisation der jiid.

nach dem sogenannten

Gesch.,

thinks that the careers of

Nehemiah and Ezra can fall only

a

few decades earlier

the reported

of Jews to Hyrcania

Artaxerxes

Nehemiah's Artaxerxes

he thinks, Artaxerxes

Mnemon.

He finds no

of Ezra's presence in Jerusalem during the

welve-years' governorship of Nehemiah the reference

to Ezra

Neh.

is

addition of the Chronicler.

Nehemiah, too, is nowhere mentioned in

Ezra

(Neh.

are interpolated).

Internal evidence alone can

the date of Ezra.

Neh.

13

is connected

naturally with Ezra

9

Ezra's arrival then

in the time after Nehemiah's return to Susa;

the text of Ezra

(which belongs to the redactor) has

in transmission

368

or

365 was the original

reported.

Nehemiah's second arrival, a t any rate,

after the promulgation of the Law

proposes to read in Neh. 136 ' a t the end of

his days'

implying a date between 367 (364) and

359. Cheyne, in

a

work almost devoid of notes, but

called ' t h e provisional summing up of . special re-

searches,' differs in some respects

in

his chronological

view of the events alike from the scholars just referred

to,

and from Ed.

who is about to be mentioned.

(See his

after

the

'98,

translated, after revision by the author, by H. Stocks

under the title

D a s religiose

der

nnch

'99).

Like Marquart he doubts the correctness

of the text of Neh.

514

but he is confident that the

Artaxerxes of Ezra-Nehemiah is Artaxerxes

I.,

and

that Nehemiah's return to Susa precedes the arrival

of Ezra with the Gola.

The incapacity of Nehemiah's

successor (the Tirshatha?) probably stimulated Ezra to

seek a firman from the king, though the terms of the

supposed firman in Ezra7 cannot be relied upon.

Ezra seems to have failed at the outset of his career,

and it was the news of this failure, according to

Cheyne, that drew Nehemiah

a

second time from Susa.

Klostermann's treatment

of

the chronology in Herzog

cannot be here

Ed. Meyer's thorough discussion

how-

ever, has convinced the present writer that we are not

entitled to call in question the arrival of Ezra before

Nehemiah, and consequently that the datum of Ezra

be right after all.

If

so,

Ezra returned to

Jerusalem with the

in 458

B.

having it for his

object to introduce the law there.

I n this, however, he

did not succeed. I t was not until after Nehemiah had

arrived in Jerusalem in 445

B.C.

clothed with ample

powers, and had in the same year restored the city walls

with his characteristic prudence and energy, that Ezra

was a t last able to come forward and introduce the law

under Nehemiah's protection

(445

B

.c.).

From this

date onwards till 433

B.C.

(cp Neh. 136) Nehemiah

continued

Jerusalem.

Shortly after 433

perhaps in

obtained a second furlough.

How long this lasted we do not know

but its import-

ance is clear from Neh.

The

O T

offers no further chronological

material for determining the dates of the

last

centuries before Christ.

But the essay was 'completed zgth

August 1895 (p.

CHRONOLOGY

CHRONOLOGY

The apocalypse of Daniel cannot he held to bridge over the

gap between Ezra and the time of the Maccabees with any

certainty, for it is the peculiarity of these apocalypses to point

to past events

a veiled way and it is in fact only what

we know otherwise of the

Syria and

Egypt and of the doings of Antiochus Epiphanes that makes

an unherstanding and an estimate of the

in the

Book of Daniel possible. Besides, its intimation (9

that

from

the destruction of Jerusalem

Nebuchadrezzar (586) to

the death of Antiochus Epiphanes

we are to reckon a

period of

years-shows how inaccurate

the chronological knowledge of the writer was, and how much

need we have to look

for other help.

Astronomy would furnish the surest means for deter-

mining the exact year and day of events, if the

OT

or

be tempted

to

go

so

as to suppose

a solar eclipse to explain the sign on the-sun-

dial of Ahaz given to Hezekiah by Isaiah

(Is.

perhaps also the ‘standing still of the sun at Gibeon’

(Josh.

Rationalistic

as

this

may seem, Ed. Mahler (see

38 for

title of work) has not been content to

stop here,

has discovered many solar eclipses in-

timated

the

OT

:

he even finds them in every pro-

phetic passage that speaks of

a

darkening of the sun.

In

this way he has been able to determine astronomically

a whole series of events. Before

we

can accept these

results, however, we must examine more carefully the

foundation on which they are reared.

For example, Mahler assigns the Exodus to the 27th March

B.C.

which was a Thursday, because fourteen days before

that day there occurred a central solar eclipse. This calculation

rests on Talmudic d a t a l that assign the darkness mentioned in

Ex.

to the

of Nisan, and explain that that day, and

therefore also the

of Nisan was a Thursday. In Ex. 10

indeed we

of a darkness

three days

;

hut Mahler argue:

that

note of duration really belongs not to

hut to

23,

and is

simply to explain how ‘intense and terrifying was

the impression which the darkness produced on the inhabitants

of

that no one dared for three days to leave his

house. I t is just as arbitrary to assume in Gen. 15

an eclipse

enabling Abraham to count the stars before sunset, and then to

use the eclipse for fixing the date of the covenant then con-

cluded

hen

The time a t which search

is

to he made for this eclipse Mahler reckons as’

years

before the Exodus, since

tradition thus explains the

number

assigned in Ex.

to the stay in Egypt, whilst on

the other hand it makes the 400 years assigned in Gen.

to the bondage begin with the birth of Isaac. The desired

eclipse Mahler finds on 8th Oct. 1764

about

years

before the Exodus

.

see above).

if possible is the

of Gen. 28

and

which

relies for the determination of the beginning and

the end of the twenty-years’ stay of

in Haran.

The

solar eclipse indicated

him in Gen. 28

(‘because

the sun was set must have been, he argues, in the evening, and

would thus

the eclipse that occurred on the 17th Feh.

B

.c.,

whilst Gen.3232 (‘and the sun rose upon him’) must

indicate a morning eclipse, which occurred on

May

B

.C.

If we add that for the victory of Joshua a t Gibeon (Josh.

10 12-14) he has found a solar eclipse calculated to have occurred

on

Jan. 1296

B

.c.,

we have for the earliest period the following

items :-

E

ARLY

D

ATES

.

Abraham’s

(Gen. 15 5

1764

B

.C.

Jacob‘s journey to Haran (Gen. 28

.

.

return home (Gen. 32

.

.

.

1581

Exodus (Ex.

. .

.

27th March

Joshua’s victory a t Giheon (Josh.

10 12-14)

. .

1296

Even more artificial

The attempt to do justice to Is. 38 8

the assumption of a

solar eclipse is at least more interesting. According to this

theory all the requirements of the narrative would be met if a

solar

had occurred ten hours before sunset, since in that

case the index could have traversed over again the ten degrees

which owing to the eclipse, it had ‘gone down,’ and

would

have

made its usual indication. Such an eclipse has, more-

over, been found for 17th June 679

B

.c.,

whence since the sign in

question belongs to Hezekiah’s fourteenth

his reign must

have covered the years

B

.C.

The further calculations which

fix a whole series of dates on

the ground of misunderstood passages are likewise quite unsatis-

factory. Thus, Amos is made

to announce to Jerohoam

the solar eclipse of 5th May

B

.C.

Is.

163 and Micah36

are made to refer to that of the

Jan. 68

B

c.

in the time of

Hezekiah and Joel who is represented as

in the time of

Manasseh, is made

indicate no fewer than three solar eclipses

Tan. 662.

661.

and

B

.c.:

CD

2

I

O

4

4

further ’nrged

30 18 and 328 to the solar eclipses of

May

557

and

Nov.

556 ;

Nah.

1 8

to that of 16th March

; Jer. 4 23

2 8

to

that on

Sept. 582 (in the time of Josiah); and

Is.

to

that on 5th

March 702

(in the time of Ahaz); and, finally, that even the

fight against

can. accordins to

5

be with certaintv

-

-

fixed

Aug.

B.c.

Bv

these ‘results’ with the

of the O T

himself justified in

following

chronological table for the time of the Monarchy

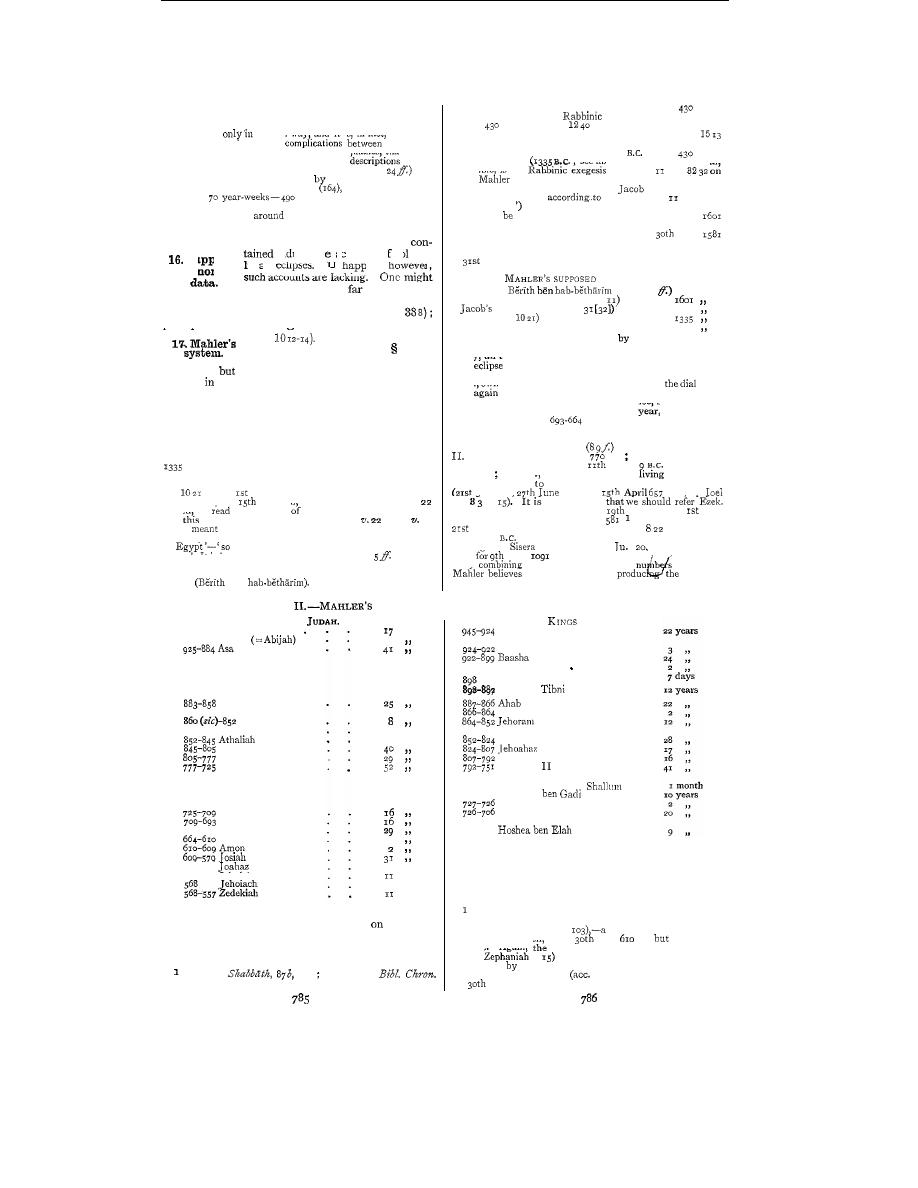

:-

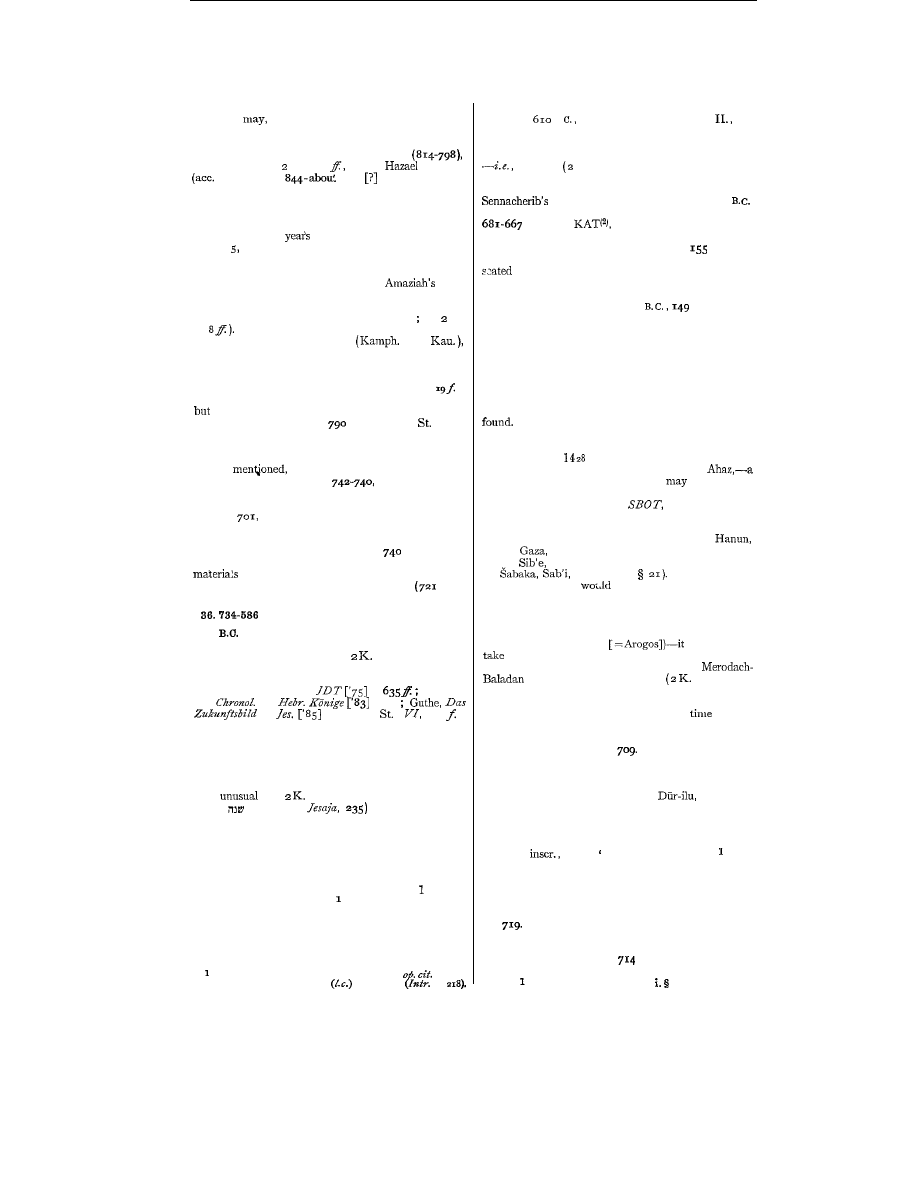

TABLE

REMARKABLE

C

HRONOLOGY

:

D

I

V

IDED

M

ONARCHY

.

K

I

NGS

O

F

945-928 Rehoboam

.

928-925 Ahijam

.

.

.

,

.

Jehoshaphat

.

,

Joram

. .

852

Ahaziah

.

. .

.

. .

Joash

. . .

Amaziah

. .

.

Uzziah

. .

.

. ...

Jotham

. .

.

Ahaz.

. . .

693-664 Hezekiah

. . .

Manasseh

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. ... .

579

.

.

.

579-568 Jehoiakim

. .

Jehoiachin

. .

.

.

.

years

3

I

year

7 years

55

3 months

years

3 months

years

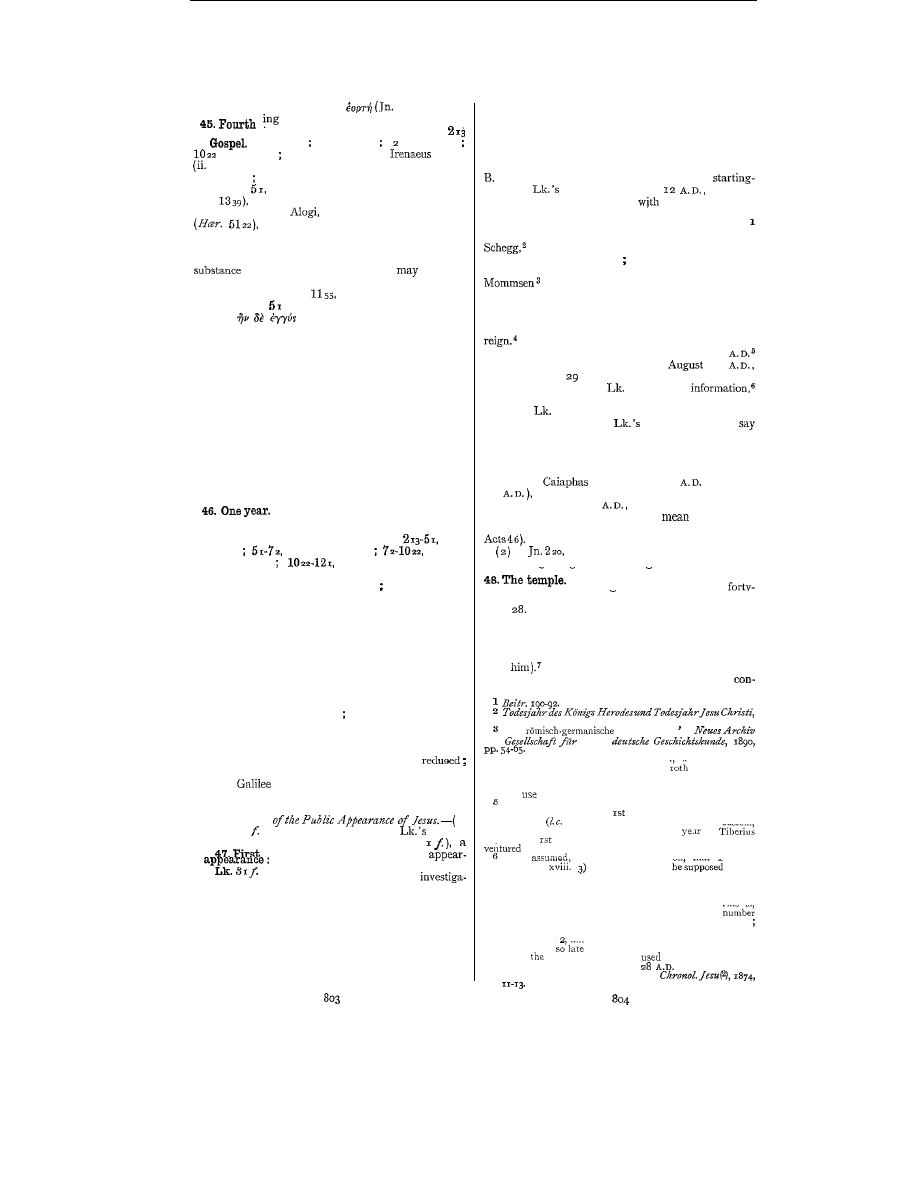

It is only

a

pity that the imposing edifice thus erected

in the name of astronomical science rests

a founda-

tion

so

unstable-an artificial phantom, dependent on

a

Rabbinical exegesis, itself a mere creation of fancy.

The

OT

itself having thus failed to give sufficient

B.

Talm.

etc. see Mahler,

4 8

O

F

I

SRAEL

.

Jerohoam.

. . . .

Nadab

. .

.

.

.

. .

. . .

899-898 E l a h .

. .

.

. .

Zimri

.

.

. . .

Omri

Omri and

} .

.

.

. . . . .

Ahaziah

.

.

. . .

. . .

.

.

J e h u .

. . . . .

.

. . . .

Joash

. . .

.

.

Jerohoam

.

.

.

.

739

Zechariah 6 months,

.

738-728 Menahem

. . .

Pekahiah

. . .

.

.

Pekah hen Remaliah

.

.

697-688

.

. .

....

....

Mahler finds here a reference to the fall of Nineveh. H e

argues that the battle against the Lydians in which the day

became night (cp Herod. 1

battle which preceded the

fall of Nineveh-fell not

on

Sept.

B

.C.

on 28th May

585

B

.C.

Again

solar eclipse with the announcement of

which

(1

connects an allusion to the expedition

undertaken

Phraortes against Nineveh a t least twenty-five

years before its final fall is

to Mahler) one that happened

on

July 607.

CHRONOLOGY

CHRONOLOGY

cording to

8

(var.

foreign nations, which

so

often come

contact with Israel, can help

us.

In

so

doing we must consider in the first

place the Egyptians.

It

to Egypt that the narrative

of the origin of the people of Israel points; thither

escaped the remnant of the community of Gedaliah

and in the interval between these times, as also later,

the fortunes

of

Palestine were often intertwined with

those of Egypt.

The Egyptians themselves possessed no continuous

era for the quite unique mention, on a

stele

from

of the

year of the king

(accord-

'"

*'

ing to Steindorff probably none other than

the god Set of Tanis), is too obscure and

uncertain, and would not help

us

at all even were it

more intelligible. Nor yet does the

Sothis-period

help

us

much. This was a period of 1461 years, at each

recurrence of which the first days of the solar year and

of the ordinary year of 365 days once again coincided

for four years, or, what amounts to the same thing, the

Dog-star, from whose rising the solar year was reckoned,

again appeared on the

of Thoth.

The period was

never used for chronological

Nor have the

monuments fulfilled the expectation, not unreasonable in

itself, that by the help of inscriptions giving dates accord-

ing to two methods it would be possible, by calculation,

to reach

a

more exact chronology for Egyptian history.

The most learned Egyptologists, indeed, can themselves

determine Egyptian chronology only through combina-

tion with data from outside sources. The conquest

of

Egypt by Cambyses

the year

525

B.C.

furnishes

their cardinal point.

From this event, the years of

reign of the kings of the 26th dynasty

may be fixed with certainty by the help

of the data supplied by the monuments,

Herodotus, and

What lies before Psamtik I.,

the first pharaoh of this dynasty, however, is in the

judgment of Egyptologists more or less uncertain, and

therefore for other chronological determinations the

records of that earlier time are either not to be used ai

all or to be used with the greatest caution.

Still, even this short period, from

(the accessior

of Psamtik I.

)

to

is a help to

us

by supplying

points of reference. Through synchronisms of

and Judean history several events of the time are to

certain extent fixed. Thus Necho

11.

(middle of

B

.

C.

to beginning of 594

B

.c.)

is admitted to be

king who fought the battle at Megiddo that cost

his life. So mention is made in the O T of

(Apries), who reigned 588-569

B

.c.,

and was even dowr

to

564 nominally joint ruler with

(see

E

GYPT

,

69). Thus we get fixed points for the contemporarie:

of Necho

Jehoahaz, and Jehoiakim

for the contemporaries of Hophra-Jeremiah, and

Jews

Egypt (Jer.

neither for

battle of Megiddo nor for that of Carchemish can

year be determined from Egyptian data.

On the othe

hand, these Egyptian data are sufficient to prove tha

the astronomical edifice

of

Mahler is quite impossible.

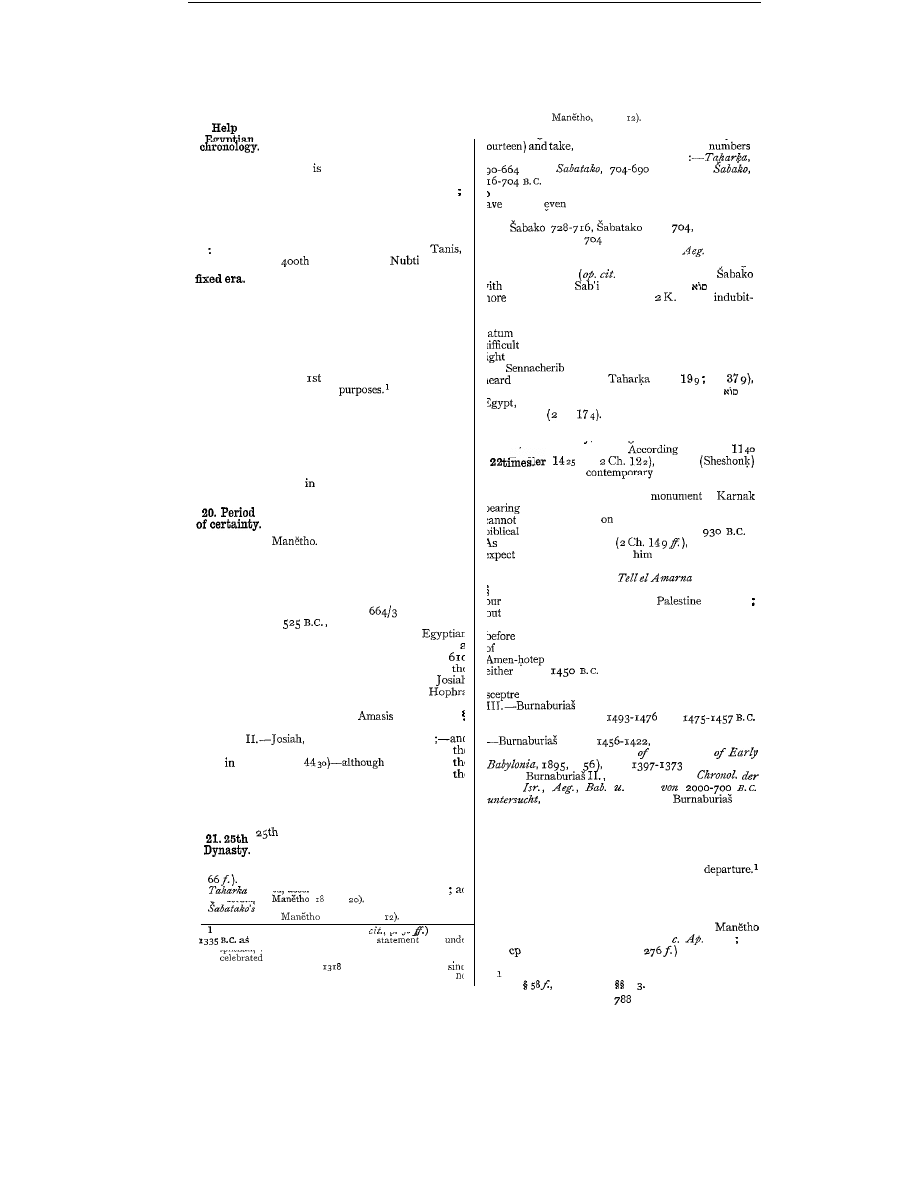

For the time before Psamtik

I.

the rulers of th

dynasty may be fixed approximately

Tanutamon ruled alone only a short time

and therefore may fall out of account.

T h

data for his three predecessors do not agree (cp

E

GYPT

§

reigned according to the monuments, 26 years

reign, according to the monuments, was uncertain

The confirmation that Mahler (of.

p. 56

seeks fc

the date of the Exodus in the

that

Menephthah whom he holds to be the pharaoh of the Exodus

was

the beginning of a Sothic period, which ma

have happened in the year

B

.c.,

is

certainly weak,

the pharaoh who according to Ex. 14 was drowned could

have reigned after that for

17

years.

cording to

(var.

according to

it was 14 (var.

See

E

X

O

DUS

.

787

as our basis for the rest, the

. the monuments, we get the following

B.C.,

B.C.,

and

Still, according to the view of Steindorff,

whom we are indebted for these data, Taharka may

reigned

longer than twenty-six years, perhaps

long with Sabatalco.

Since, however, Ed. Meyer

ives

circ.

and makes

'aharka as early as

real master, although not till

89 official ruler, of Egypt (cp

Gesch.

343

&),

11

sure support is already gone. Besides, although

ccording to Meyer

344) the identity of

the Assyrian

and the Hebrew

( S o ' ,

or,

correctly, Save' or Seweh) in

17

4

is

ble, Steindorff has grave doubts as to the phonetic

quivalence of these names, and finds no Egyptian

for the battle of Altaku.

It is, therefore, very

to get from Egyptian chronology any certain

on two O T statements relating to Egypt-viz.,

hat

sent messengers to Hezekiah when he

of the expedition of

( 2

K.

Is.

.nd that Hoshea of Israel had dealings with

of

and was therefore bound and put into prison by

ihalmaneser

K.

For the chronology of the O T in still earlier times,

here is. unfortnnatelv. nothing at all to be pained from

Egyptology.

to-

I

K.

(cp

Shishak

was a

of Solomon. and in

he fifth year of Rehoboam went up against Jerusalem.

n spite, however, of the Egyptian

at

the list of cities conquered by him, his date

be determined

Egyptological grounds

(on

grounds it is usually given as about

).

to 'Zerah the Cushite'

we need not

to find any mention of

in Egyptian sources

Z

ERAH

).

The clay tablets found at

(see

I

SRAEL

,

6 ) , indeed, make some important contributions to

knowledge of the relations of

to Egypt

for the chronology they afford nothing certain.

We must get help from the chronology of Babylonia

we can, even approximately, determine the date

the correspondence. Then it seems probable that

111.

and Amen-hotep IV. reigned in Egypt

about

or

about 1380

B.c.,

at which

time, therefore, Palestine must have stood under the

of Egypt : the contemporaries of Amen-hotep

I. and Kurigalzu

I. of

Babylon-axe

assigned by Winckler to

and

respectively, and the contemporary of Amen-hotep IV.

11.-to

whilst R. W. Rogers,

on the other hand

(Outlines

the History

p.

gives

as

the probable

date of

and C. Niebuhr

(

Gesch.

Ass.

1896) accepts only one

and

places him and his contemporary Amen-hotep IV. in

the beginning of the fourteenth century

B.C.

As

in

these tablet inscriptions the name of the Hebrews has

not

so

far been certainly discovered,

so,

in the Egyptian

monuments generally, we cannot find any reminiscence

of a stay of Israel in Egypt or of their

Theories about the pharaoh of the oppression and the

pharaoh of the Exodus remain, therefore, in the highest

degree uncertain.

Neither Joseph nor Moses is to be

found in Egyptian sources : supposed points of contact

(a seven-years famine, and the narrative of

about Osarsiph-Moses in Josephus,

12728

on

this

Ed. Meyer, Gesch.

Aeg.

have proved,

on

On the inscription of Menephthah discovered

in

1896, see

E

GYPT

,

and

E

X

O

D

U

S

,

I

,

CHRONOLOGY

nearer

Apart, therefore, from

the dates of the rulers of the twenty-fifth and the twenty-

sixth dynasties, there is very little to be gained for O T

chronology from Egyptology. On Egyptian Chronology

see

also

E

GYPT

,

It is

much better supplied with chronological material, since

Assyriology offers much more extensive help.

CHRONOLOGY

Eponym year of

(Schr.

the thirteenth of

Sargon’s

rule in

Hence we

may identify this

year of

(the thirteenth year of Sargon’s reign in Assyria) likewise

with the year

B.C.

as the series is uninter-

rupted, all its dates become

W e can, then,

obtain astronomical confirmation of the correctness of

this combination (and

so

also of

trustworthiness of

the Ptolemaic Canon and the Assyrian

lists) in

the way hinted at already.

For,

if the

year of

is the year

the Eponym

year of

to which, as we saw above, there is

assigned a solar eclipse, must be the year 763 B

.c.;

and astronomers have computed that

on

the

June

of that year a solar eclipse occurred that would be

almost total for Nineveh and its neighbourhood. Thus

the Assyrian Eponym list may safely be used for

chrono-

logical purposes.

On the ground of the statements of this list, then,

we have, for the years 893-666

fixed points not to

called in question by which to date

the events of this period in Israel; for

the Assyrian inscriptions not only supply direct informa-

tion concerning certain events in Israel’s own history,

but also in other cases fix the date of contemporaneous

events which the narrative of the

OT

presupposes.

Then the Ptolemaic Canon, which from 747

on-

wards accompanies the Assyrian Eponym list, continues

when the Eponym list stops (in 666

and conducts

us

with certainty down to Roman times.

W e are thus enabled to determine beyond all doubt

the background of the history of Israel and Judah

893 downwards, and obtain down to Alexander the

Great the following valuable dates :-

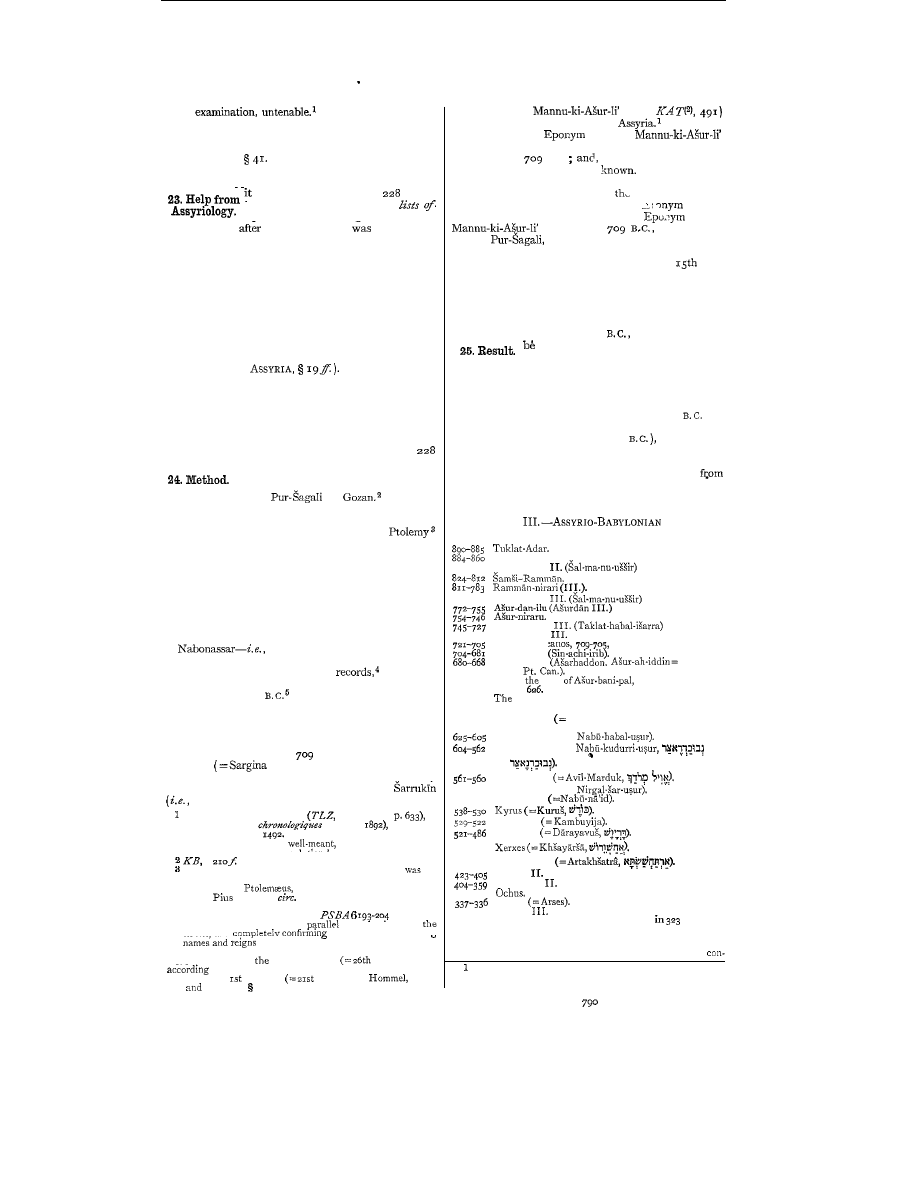

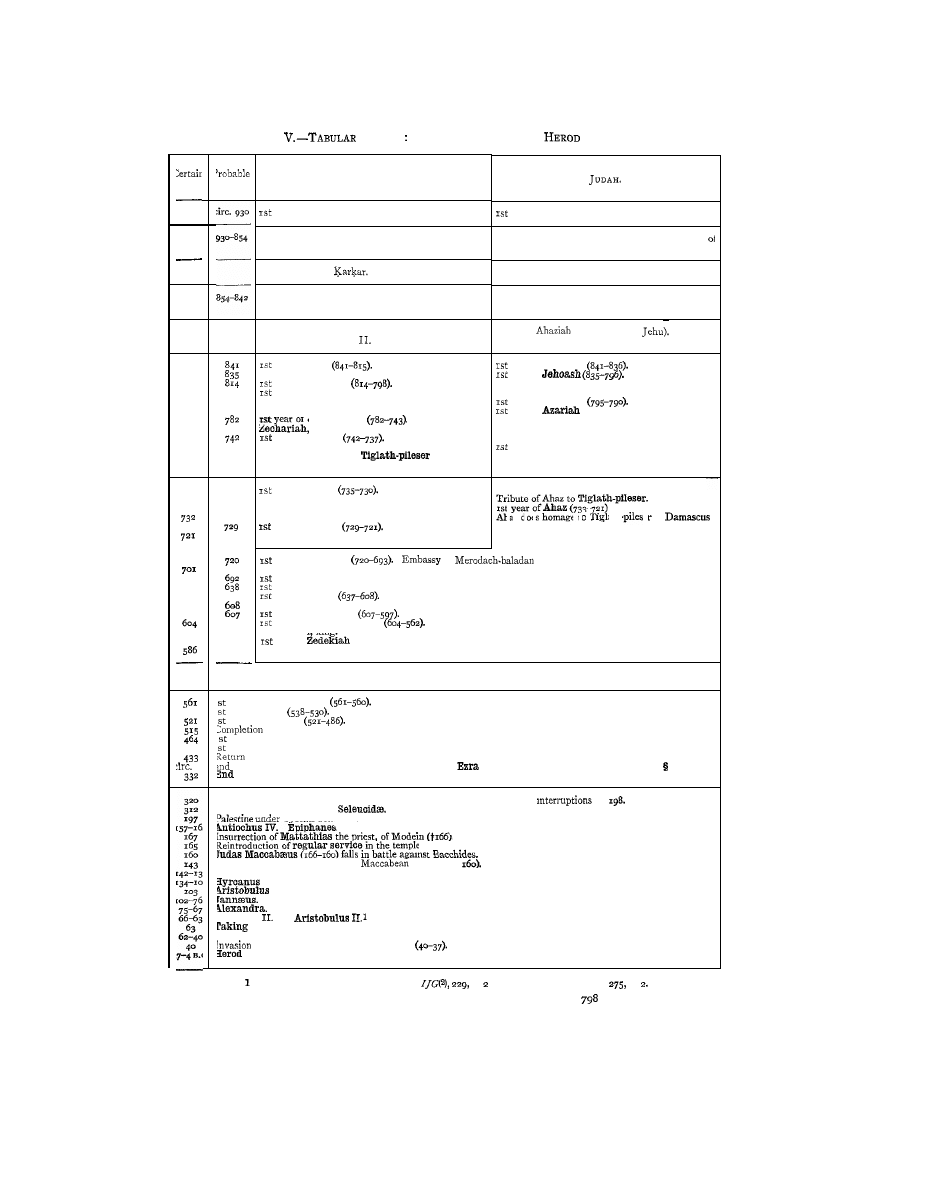

TABLE

DATES

893

B.C. TO

A

LEXANDER

THE

G

REAT

Abr-niisir-pal.

859-825

Shalmaneser

782-773

Shalmaneser

Tiglat-pileser

726-722

Shalmaneser

Sargon (Arkeaiios

king of Babylon).

Sennacherib

Esarhaddon

Asaridinos

possesses, for

a

series of

years,

inscriptions containing careful

Eponyms,

lists, that is, giving the name

of the officer

whom the year

called, and

mentioning single important events falling within the

year. These brief notes alone are quite enough to give

the lists an extraordinary importance. Their value is

further increased, however, by the fact that the office

of

Eponym had to be held in one of his first years,

commonly the second full year of his reign, by each

king.

Hence the order of succession of the Assyrian

kings and the length of their ’reign can be determined

with ease, especially as names of kings are distinguished

from those of other Eponyms by the addition of the

royal title and of a line separating them from those that

precede them (cp

The monumental

character, too,

of

these documents, exempting them, as

it does, from the risk of alteration attaching to notes in

books, gives assurance of their trustworthiness.

Nor is

the incompleteness of the list supposed by Oppert a

fact. In regard to the order of succession no doubt is

possible.

The establishment of this uninterrupted series of

years can be accomplished with absolute certainty (as

we shall see below) by the help of an

eclipse of the sun assigned by the list to

the Eponym year of

of

In order

to be able to determine the eclipse intended, however,

and thus to fix the year astronomically, we have first to

bring into consideration the so-called Canon of

-next to these Assyrian Eponym lists, perhaps the

most important chronological monument of antiquity.

This Canon is a list giving the names of the rulers of

Babylon-Babylonian, Assyrian, and Persian-from

Nabonassar to Alexander the Great (the Egyptian

Ptolemies and the Romans are appended at the end),

with the number of years each

of

them reigned, and the

eclipses observed by the Babylonians and the Alex-

andrians-the years being reckoned according to the era

of

from that prince’s accession. The

trustworthiness of this document is proved, once for all,

by the astronomical observations it

from which

we learn that the beginning of the era of Nabonassar

falls in the year 747

The Canon can be combined with the Assyrian

Eponym lists, and the establishment of the latter with

certainty effected in the following way.

On

the one

hand, the Ptolemaic Canon assigns to the year 39 of

the era of Nabonassar.

B

.c., the accession of

Arkeanos

on the fragment of the Babylonian

list of kings); and,

on

the other hand, Assyrian clay

tablets identify this year, the first of the rule of

Sargon or Arkeanos) over Babylon with the

Cp also Wiedemann’s review

1894,

No. 25,

of

Laroche’s Questions

(Angers,

where the

Exodus is assigned to

The judgment of this competent

reviewer is that ‘the book is

but brings the question

of the Exodus no nearer to a solution.

1

I t bears the name ‘Ptolemaic Canon’ because it

in-

cluded in his astronomical work by the geographer and mathe-

matician Claudius

the contemporary of the Emperor

Antoninus

(therefore

150

A

.D.).

4

The proof is strengthened by the fragments of a Babylonian

list of kings published by Pinches in

[May, ’841,

part of which constitute an exact

to the beginning of

Greek list. and

its statements concerning

the

of the rulers.

5

More exactly (since the dates are reduced to the common

Egyptian year) on

first of Thoth

Feb.), not (as

to Babylonian official usage might have been ex-

pected)

on the

of Nisan

March) (cp

GBA,

488,

see below 26).

in

till

667

=first year of

reign

who perhaps reigned

.

.

.

.

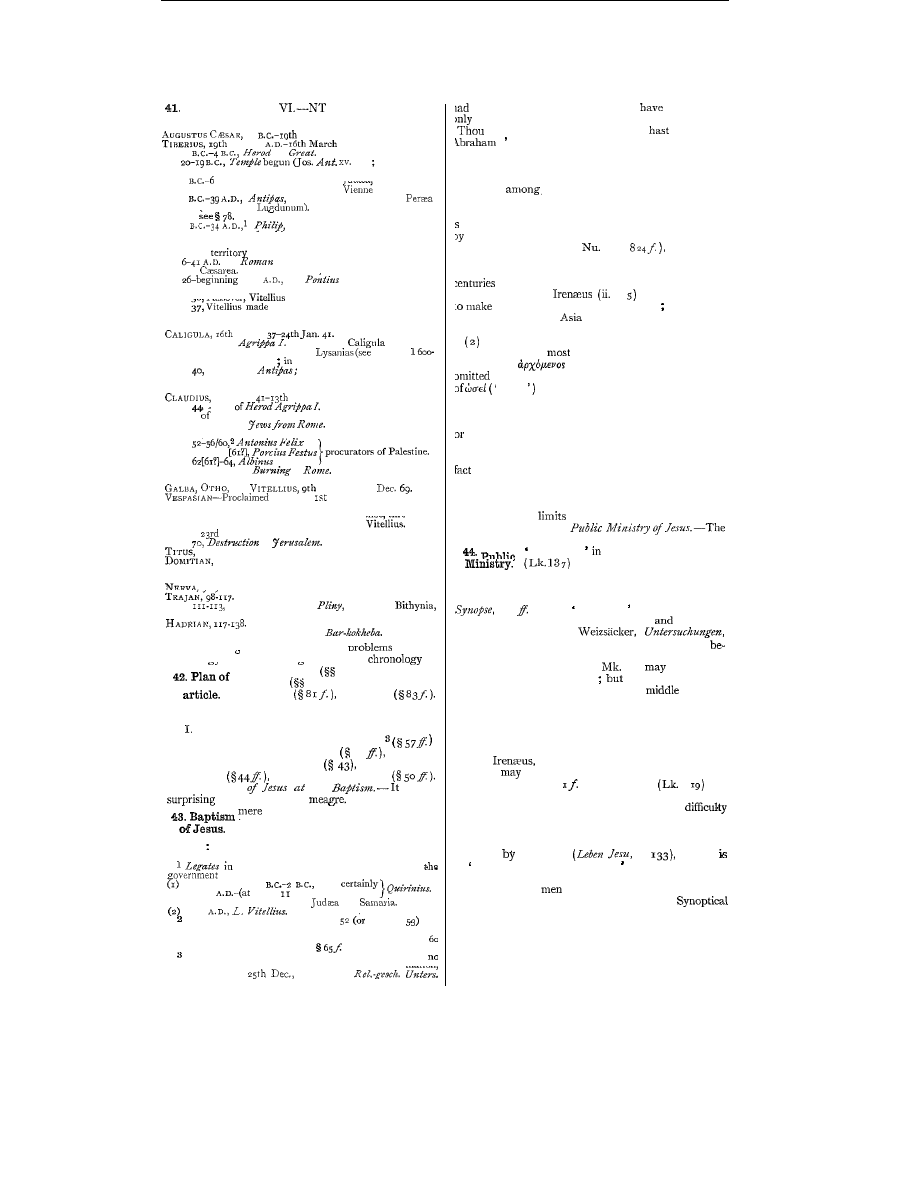

continuation is supplied by the Ptolemaic Canon

which specifies the rulers of Babylon :-

667-648

Saosduchinos

Sam&-Sum-ukin).

674-626

Kinilanadanos.

Nabopolassaros (=

Nabokolassaros (=

and

Illoarudamos

559-556

Nerigasolasaros (=

555-539

Nabonadios

Kambyses

Dareios

I.

485-465

464-424

Artaxerxes

I.

Dareios

Artaxerxes

358-338

Arogos

335-332

Dareios

Here follows Alexander the Great, who died

B.C.

With regard to this summary it is to be noted that (as is a

matter of course in any rational dating by years ‘of reign-it

is certainlv the case in the Ptolemaic Canon) the vear

From the thirteenth year of his reign down to his death in

the seventeenth (and so, as the Ptolemaic Canon states, for

five

years) Sargon must have reigned over Babylon also.

789

CHRONOLOGY

CHRONOLOGY

as the first of any king is the earliest year at the begin-

ning of which he was already really reigning

:

in the preceding

year he had

to

reign on his predecessor's death. Short

reigns, accordingly, which did not reach the beginning of the

new year had to remain unnoticed, as that of

chad

in the year 556 which according to

lasted

nine

It

is

26.

Beginning

further to he noted that the beginning of

the year did not fall in the two lists on the

same day.

The Eponym lists make the

year begin on the first of Nisan, the

of March, while

the Ptolemaic Canon follows the reckoning of the ordinary

Egyptian year of 365 days, the beginning of which, as compared

with

mode of reckoning falls one day earlier every four

years. Thus, if in the

747,

as

was indeed already the

case in 748, the beginning of the year fell on the 26th of

February, the year 744 would

on

25th. For a period

of a hundred years this difference would amount to twenty-five

days. Thus the beginning of the year 647

B.C.

would fall

on

the

of February and so on. Therefore for the period

323

B.C.

the beginning of the year would always fall somewhat

near the beginning of

ours.

If, then, the chronological data of the O T were trust-

worthy, as soon

as

one cardinal point where the two series

-that of the O T and that just obtained

-came into contact could be established

with certainty, the whole chronology of the

O T would be at once determined, and the insertion of

the history of Israel into the firm network of this general

background would become possible. In the uncertainty,

however, in which the chronological data of the O T

involved, this simple method can lead to no satisfactory

result.

All points of coincidence must be separately

attended to and, although we may start out from a

fixed point in drawing our line, we must immediately

see to it that we keep the next point of contact in view.

Unfortunately, in going backwards from the earliest

ascertainable date to a remoter antiquity such

a

check

is not available.

The earliest date available,

as

being certain beyond

doubt, for an attempt to set the chronology of the O T

on a firm basis is the year

854

B

.c.,

in

which Ahab king of Israel was one of

the confederates defeated by

11.

(859-825) at

(Schr.

and

Since, how-

ever, the

O T

contains no reference to the event, it is

of no use for the purpose of bringing the history of

Israel into connection with general history till we take

into consideration also the next certain date, 842

in

which year presents were offered to the same Assyrian

king, Shalmaneser II., by Jehu

Within these thirteen years (854-842) must fall the death

of Ahab, the reigns of Ahaziah and Jehoram, and the

accession of Jehu.

Of this period the most that need

be assigned to Jehu is the last year, which may have

been at the same time also the year of Jehoram's death

for it may be regarded as quite probable that it would

be immediately after his accession that Jehu would send

presents to the Assyrian king to gain his recognition

and favour. On the

the traditional values

of the reigns require for Ahaziah two years

(

I

K.

and for Jehoram alone twelve years

K.

31)

:

so

there

appears to be no time left for Ahab after

854.

The

death of Ahab, however, cannot be assigned to

so

early

a

date as

The reigns of Ahaziah and Jehoram,

therefore, must be curtailed by more than one year.

The course of events from 854 to the death of Ahab in

the struggle with the Syrians has, accordingly, been

ranged in different ways.

Wellhausen

supposes that in consequence

of

universal defeat in 854 Ahab ahanboned the relation o

vassalage to Aram that

lasted till then and thus provokec

a Syrian attack' on Israel. Then, by the

a t Aphek

the second year and the capture of Benhadad he compelled tht

Syrians to conclude peace and to promise

deliver up

cities

had won from Israel

(I

K.

20).

As

Victor Floigl

1882,

94-96), indeed, supposes t h a

Ahah fell before Karkar

854)

and not before Ramoth

Gilead

to accomplish

he

to treat the narratives o

the Syrian wars

(I

K.

20

38-43

22

as quite

worthy.

of

year.

did not keep their promise he undertook in the third

rear of the peace the unfortunate

for the conquest of

in which he met his death

(I

K.

22).

Thus the

of Ahah

fall ahout the year 851. Schrader on the'

hand, sees in Ahab's taking part in the battle of

consequence of the conclusion of peace with Aram that

hllowed the battle of Aphek, and

it thus possible to

death to

so early a date as 853. Even if we

nclined to follow the representation of Schrader (Wellhausen's

much more attractive) the Assyrian notice of the battle of

in 854

least one point, that the beginning

Jehu's reign cannot be earlier than 842,

and the traditional

lumbers must he curtailed.

On

the question just discussed see

A

HAB

.

The year 842

B

.C.

may, therefore, be assigned

as

that

the accession of

In the same year also perished

king of Israel,

and

Ahaziah,

king of Judah, whilst Athaliah seized

.

the reins of government in Jerusalem.

If

from this

for

both

kingdoms, we try to go back;

with approximate certainty the year of the division of

the monarchy. The years of reign of the Israelitish

kings down to the death of Jehoram make up the

sum

of

ninety-eight, and those of the kings of Jndah down to

the death of Ahaziah the

of ninety-five whilst the

synchronisms of the Books of Kings allow only

eight years. Since the reigns of Ahaziah and Jehoram

of Israel must be curtailed

if we assume ninety

years as the interval that had elapsed since the partition

of the kingdoms this will be too high rather than too

low

an estimate.

The death of Solomon may, accord-

ingly, be assigned to

B.C.

Wellhausen

indeed, raises an objection against this, on the

ground of a statement in the inscription of Mesha but

the expression in the doubtful passage is too awkward

and obscure to lead us, on its account, to push back

the death of Solomon to

or even farther.'

In this connection it is not unimportant that the

statements of Menander of

in regard to the

Tyrian list of kings confirm the

assignment of

B

.C.

as

the

.-

mate date

of

the de&

of

According to the careful discussion that

Riihl has

devoted to this statement (see below

85

end), preserved to us

in three forms (first, in

second, in the

Chron. of Euseh., and third, in Theophilnsad

iii.

we may, assuming

Gutschmid's date of 814

B.C.

for the

foundation

of

fix on

as

the period of reign

of

or Hiram and on 878-866

B.C.

that of

or

Ethha'al. Now

was son-in-law of Ethha'al

(

I

K. 16

and since

at his accession in the year 878

B

.C.

was

thirty-six years old be could quite well have had a marriageable

daughter a few

later when Ahab

according to

I

16

reigned twenty-two

(about

B

.c.),

ascended

the throne. Moreover, Menander mentions a one-year famine

under Eithobalos, which even Josephns

with the three-year famine that, according to

17,

fell

in the beginning

the rei

of Ahah. Further, Eiromos

936)

may he identified

Hiram, the friend of Solomon (cp

I

K.

5

18 24

32 9

IO

and, whether we adopt the opinion

that Hiram the contemporary of David

S. 5

was the same

person as

Solomon's, or suppose that the name of

the better-known contemporary of Solomon has simply been

transferred to the

king who bad relations with David.

the year

930

B

.C.

for the death of Solomon, agrees excellently

with this

synchronism.

We. translates lines

thus

Omri conquered

whole

land of Medaha, and Israel dwelt there during his days and

half the days of his son forty years, and Kamos recovered it

in my days.

H e thus

a t an estimate

of

at least sixty

years for Omri's and Ahab's combined reigns since only by

adding the half of Ahab's

to

the part of

reign during

which Moab was tributary

the total of forty years attained.

It

is to be noted however

Israel

'

We. (so also

and Socin,

1886,

p . 13)

supplies as the subject to 'dwelt'

is lacking in the

inscription, and that even with this insertion the construction is

not beyond criticism.

Is it in the undoubted awkwardness of

the passage, not possible to

thus-' Omri conquered the

whole land of Medaba and held it in possession as long as he

reigned, and during

half of

years of

reign

son,

in all forty years.

But

yet in my reign

recovered it.'

In that case

is

no

ground for ascribing so many as sixty

years to

reigns of Omri and Ahab. Nay, the pocsibility is

not excluded, that

K.

3

5

is right in making the revolt of Moah

follow the death of Ahah, and then the futile expedition of

Jehoram of Israel and Jehoshaphat

of

Judah against Moab

could he taken as marking the

of the forty years.

792

CHRONOLOGY

CHRONOLOGY

If it has been difficult to attain sure ground in the

early period of the divided

it is even less

.

possible to determine anything with

certainty about the period preceding

Solomon's death.

If the data of the

concerning the reigns of Solomon and David (40

years each,

I

1142)

have any value, David must

have attained to power about the year

B

.C.

Concerning Saul, even

I

gives

us

no real in-

formation, and regarding the premonarchic period the

most that can be said is that, according to the

discoveries at Tell-el-Amarna the Hebrews were, about

the middle of the fifteenth century

not yet settled

in

For the time, therefore, from the partition of the

kingdom down to the year 842

B.c.,

we must be content with the following

estimate :-

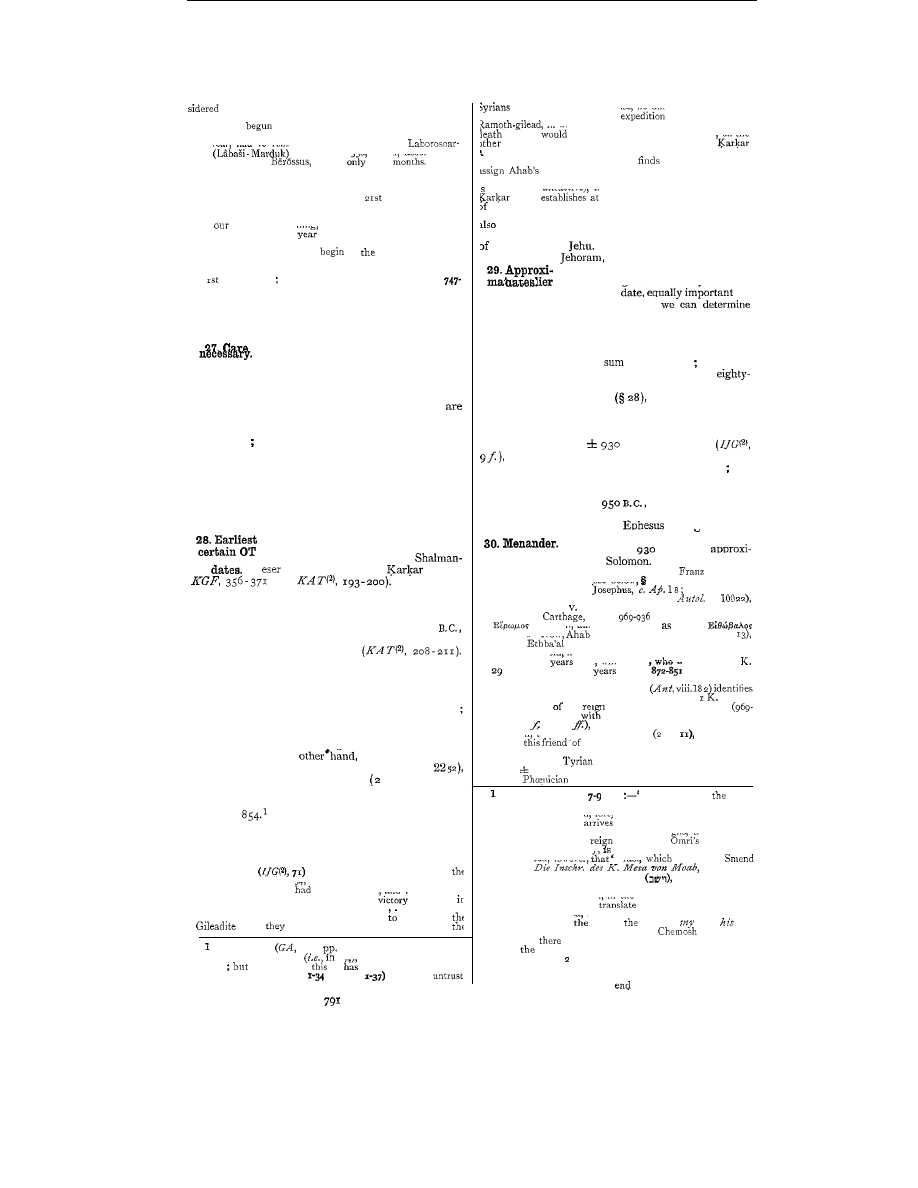

TABLE

~ ~ . - E

S

T

I

MA

T E

O F

R

EIGNS

:

D

E

A

TH

OF

S

OLOMON TO

A

CCESSION

OF

J

EHU

.

K

I

N

GS O

F

K

I

N

GS

OF

I

SRAEL

.

(?) -854 Jerohoam of Israel and his contemporaries Rehohoam and Ahijah in Judah.

Nadab

Ba'asha

of Judah certainly Contemporary with

Elah

Zimri

Omri

Ahab

Jehoshaphat, king of Judah, contemporary with Ahab,

Ahab at

Ahaziah, and Jehoram.

Ahaziah, king of Israel

Jehoram

Jehoram, king of Judah.

Death of

Israel

Ahab's death

Death

of

Ahaziah of Judah.

From 842

B.C.

onwards, there is no fixed point till

Then we have one in

we come to the eighth century.

the eighth year of the Assyrian king

Tiglath-pileser

738

B

.C.

In

that year, according to the cunei-

form inscriptions, this king of Assyria

received the tribute of

of

When-the

OT

tells of this

15

it calls the Assyrian king

although elsewhere

( 2

K.

it uses the

other name, Tiglath-pileser.

Of the identity of the two

names, however, there can be no doubt

223

C O T ,

1

and we are not to think of the reference

being to a Babylonian king, or an Assyrian rival king,

or to assume that Tiglath-pileser himself, at an earlier

period, twenty years or more before he became king

over Assyria, while still bearing the name of Pul, made

an expedition against the land of Israel (so Klo.

p.

496). If we add that Ahaz of

procured for himself through a payment of tribute the

help of Tiglath pileser against the invading kings,

Pekah

of

Israel and Rezin of Damascus that, accord-

ingly, the Assyrian king took the field against Philistia

and, Damascus in 734 and 733 and that in

after

the

of Damascus, Ahaz

also

appeared in

to do homage to Tiglath pileser, there

remains to be mentioned only the equally certain date

of the beginning of the year 721

(Hommel,

676) for the conquest of Saniaria, to complete the list

of assured dates between 842 and 721.

The attempt to arrange the kings of North Israel

during this period is hampered by fewer difficulties in the

interval

than are to be found in

that between 738 and 721. If we assume

that Menahem died soon after paying

tribute, we shall still have in the 113 years

reckoned by the traditionary account from the accession

of Jehu to the death of Menahem a slight excess, since

for the period

we need only

years.

Still,

we can here give an approximate date for the individual

reigns. The latest results of

(in substantial

agreement with Brandes,

and Riehm)

are the following

Jehoahaz

Jehoash

Jeroboam

11.

782-743 (or before

Zechariah and

perhaps also in 743, Menaheni

(or

745 to after 738).

For the last

period,

on

the other hand, from the death of Menahem

to the conquest of Samaria, the traditional reckoning

gives thirty-one years, whilst from 737 to 721 we have

hardly sixteen. The necessary shortening of the reigns

We modify them only to the extent of giving as the first

year of a reign the year at the beginning of which the king was

already

power, and adding in parentheses the figures of We.,

in so far as they are

to

he found in his

793

is accomplished by Kautzsch in this way

:

Pekahiah

736, Pekah

Hoshea

Wellhausen

has abandoned his former theory that Pekahiah and

Pekah are identical, and makes the latter begin to

reign in

735.

To

Hoshea, the last king of Israel,

he assigns an actual reign of at least ten years, although

he assumes that according to

2

K.

he came

under the power of Assyria before the fall of Samaria.

For the Judean line of kings the starting-point is

likewise the year 842

in which Ahaziah of Judah

met his death at the

Jehu, and

,

Athaliah assumed the direction of the

government.

On the other hand, we do

not find, for the next hundred years, a single event

independently determined

perfect exactness by

years of the reigning king of Judah. W e must come

down as far as 734

B.C.

before we attain certainty.

know that at that time Ahaz had already come

to power, and we can only suppose (according to

he

not long before this succeeded

his father,' during whose lifetime Pekah of Israel and

Rezin of Damascus were already preparing for war.

The presents of King Ahaz to Tiglath-pileser in the

year 734

B

.C.

delivered Judah from the danger

that threatened it, and in

the conquered

Damascus the same king did homage to the victorious

Assyrian, and offered him his thanks (cp

K.

16

and

Schrader,

It is still difficult, however,

to allot the intervening time to the several kings of

Judah

for the traditional values for the reigns require

no

less than

years from the first year of Athaliah

to the death of Jotham, whilst between 842

B

.C.

and

734

B.C.

there are only

years at our

It is, therefore, necessary to reduce several of the

items by a considerable amount, and it is not to be

wondered at that different methods of adjustment have

been employed. The synchronism of events between

the history of Israel and that of Judah is too inadequate

to secure unanimity, and the mention (not quite certain)

of Azariah of Judah in Assyrian inscriptions for the

years

(cp Schr.

does not make

up the lack.

On

one point, however, there is agree-

ment: that it is in the cases

of

Amaziah, Azariah

(Uzziah), and Jotham that the deductions are to be

made.

The years

B

.c.,

for Athaliah are rendered

tolerably certain by the data concerniug Jehoash, the

infant son of Ahaziah

K .

1 1

I

Then we

need have no misgivings about giving Jehoash, who

was raised to the throne at

so

young an age, about

forty years.

If we take these years fully, we obtain

On early traces of certain elements afterwards forming part

of

Israel, see I

SRAEL

,

:

794

CHRONOLOGY

CHRONOLOGY

for the reign

of

Jehoash

835-796

B.C.

The date of

his death

indeed, be pushed still farther back;

but in any case his time as determined by these data

cannot be far wrong, for he must have been a con-

temporary of Jehoahaz the king of Israel

and, according to

K. 1218

also of

of Aram

to Winckler

804

).

From

795

to

734

there are left only

61

years, and in this interval

room must be found for Amaziah with twenty-nine

years, Azariah with fifty-two, and Jotham with sixteen

-no

less than ninety-seven years.

Even

if

we allow

the whole sixteen

of Jotham, who, according to

2

K.

15 conducted the government during the last

illness of his father, to be merged

in

the fifty-two years

of Azariah, we do not escape the necessity of seeking

other ways of shortening the interval.

reign

is estimated too high at twenty-nine years. The only

thing that is certain about him is that he was

a

contemporary of Jehoash of Israel

(797-783

cp

K.

14

It

is

pure hypothesis to assign him nine

years (We.), or nineteen years

and

instead of twenty-nine. The smaller number has the

greater probability, since the defeat that he brought on

himself by his wanton challenge of Jehoash of Israel

best explains the conspiracy against him

(2

K. 14

),

and he would therefore hardly survive his conqueror,

much more probably meet his death by assassination

a t Lachish not long after

B

.C.

(cp also

GVZ,

1559).

From the death of Amaziah to

734

reigned

Azariah and Jotham. T o discover the boundary between

the two, we must bear in mind the Assyrian inscriptions

already

which apparently represent Azariah

as

still reigning in the years

and must keep in

view that Isaiah, who cannot be thought of

as

an old

man when Sennacherib marched against Jerusalem in

the year

received his prophetic call in the year of

the death of Uzziah

(Isa.

6

I

) .

Accordingly, we cannot

be far wrong in assigning the death of Azariah and the

accession of Jotham as sole ruler to

B

.C.

More

than this cannot be made out with the help of the

at our disposal up to the present time.

If now the year of the conquest of Samaria

B

.c.)

were fixed with certainty according to the year of the

king then reigning in Judah, this would

appear the next resting-point after

734

B.

c.

The data of the

OT

do not agree, how-

ever, and none of them is to be relied upon.

This

is true even of the datum in

1813, lately much

favoured by critics, that Sennacherib’s expedition against

Palestine in the year 701

B.

C

.

was in the fourteenth

year of Hezekiah

(so

We.

p.

Kamph.

Die

der

p. 28

des

p.

37,

and

G

1606

).

In order to maintain the datum, it

is

not enough to say,

‘

The people of Judah are more likely to have preserved

the year of Hezekiah in which- their whole land was laid

waste and their capital, Jerusalem, escaped destruction

only through enduring the direst distress, than to have

preserved the year of Hezekiah in which Samaria fell.’

The

(cp

181 9) prefixing of the numeral

before

(cp Duhm,

of itself indicates a

later origin, and this is confirmed by what we have already

found as to these chronological data not belonging to

the original narrative. The number fourteen is based,

not upon historical facts, but upon an exegetical inference

from Is. 385, and a consideration of the twenty-nine

years traditionally assigned to Hezekiah, and must there-

fore rank simply with the scribe’s note Am.

I

:

‘

two

years before the earthquake.’

Even when we come to the seventh century, the

expectation that at least the death of Josiah in the battle

of Megiddo would admit of being dated with complete

accuracy by material from inscriptions is not fulfilled.

From Egyptian chronology, which does not mention

This

is forcibly urged

by

Kau. (cp. Kamph.

94)

and

has received the

assent

of

Duhm

and

Cheyne

Is.

795

the date of the battle, we gather only that it must have

been after

B.

since the conqueror, Necho

did

not begin to reign till that year. There is, therefore,

nothing left but to take as our fixed point the conquest

of Jerusalem in the nineteenth year of Nebuchadrezzar

586

B

.C.

K.

253

8).

For

the intervening time

we have to take into consideration, besides the death of

Josiah, the data supplied by Assyriology, which place

expedition against Hezelciah in

701

and imply Manassehs being king of Judah in the years

(cp Schr.

p.

466).

For the whole time from the death of Jotham to the

conquest of Jerusalem, tradition requires

years of

reign, whilst from

734

B

.c.,

when Ahaz was already

on the throne of Jerusalem--which year, if not

that of his accession, must have been at least the first

of his reign-to 586

B

.c.,

we have only

148,

or, since

we may reckon also the year

734

years. ’The

smallness of the difference of seven years, however,

shows that we have now to do with a better tradition.

Where the mistake lies we cannot tell beforehand. All

we can say is that it

is not to

be sought between the

death of Josiah and the fall of Jerusalem, since for this

interval twenty-two years are required by tradition, and

this agrees with our datum that Josiah must have died

shortly after

610

B

.C.

Let

us

see wnether another cardinal point can be

In

701

Hezekiah was reigning in Jerusalem.

When it was that he came to the throne, whether

before or after the fall of Samaria

(721

B.C.),

is the

question. In

Is.

we have an oracle against Philistia,

dated from the year of the death of king

chronological note which, like Is.

6

I

,

have import-

ance, if the oracle really belongs to Isaiah.

Winckler

and Cheyne [but cp Isaiah,

Addenda] regard

it as possible that the oracle may refer to agitation

in Syria and Palestine, in which the Philistines shared,

on

the accession of Sargon

(721

B

.c.),

when

king of

induced them to rebel, in reliance on the

help of

one of the Egyptian petty kings (cp above

on

So’,

Seweh,

On

this theory

the death of Ahaz

have to be set down about

the year

720

B.C.

As,

however, the authenticity of

the oracle

is

not certain,-in fact hardly probable (cp

Duhm, who even conjectures that originally there may

have stood, instead of Ahaz, the name of the second

last Persian king, Arses

is not safe to

it as fixing the death-year of Ahaz.

Of greater

value is the section relating to the embassy of

of Babylon to Hezelciah

20=

Is.

39).

Merodach-Baladan was king of Babylon from

721

to

710.

When, later, he attempted to recover his

position, he held Babylon for so short a

that an

embassy

to

the west would be impossible.

Thus,

Merodach-Baladan must have sought relations with

Hezekiah between

721

and

The beginning of the

reign of Merodach-Baladan, when in the year

721

or

720

he obtained possession of Babylon and held it

against Sargon. commends itself as the point of time

most suitable. After the battle of

which both

parties regarded as a victory for themselves,

it

must

have seemed natural to hope that the overthrow of the

Assyrian kingdom would be possible, if the west joined

in

the attack. Moreover, Sargon once describes himself

(Nimriid

1 8 )

as

the subduer of Judah,’ which

seems to mean that, on the suppression of the revolt in

Philistia, Hezekiah resumed the payment of the tribute

that had been imposed. In view of this, Winckler seems

to be justified in placing the appearance of the embassy

of Merodach-Baladan before Hezelciah in the year

720

or

Approximately, then, the year

721

may he

regarded

as

assured for the year of the death of Ahaz.

The first year of Hezekiah‘s reign is thus

720

B

.

C.

rather than

728

(Kau.), or

(We, and others). The

discrepancy of four years, which is all that now remains

For

fuller details

see

I

S

AI

A

H

,

6,

S

A

R

G

O

N

.

796

CHRONOLOGY

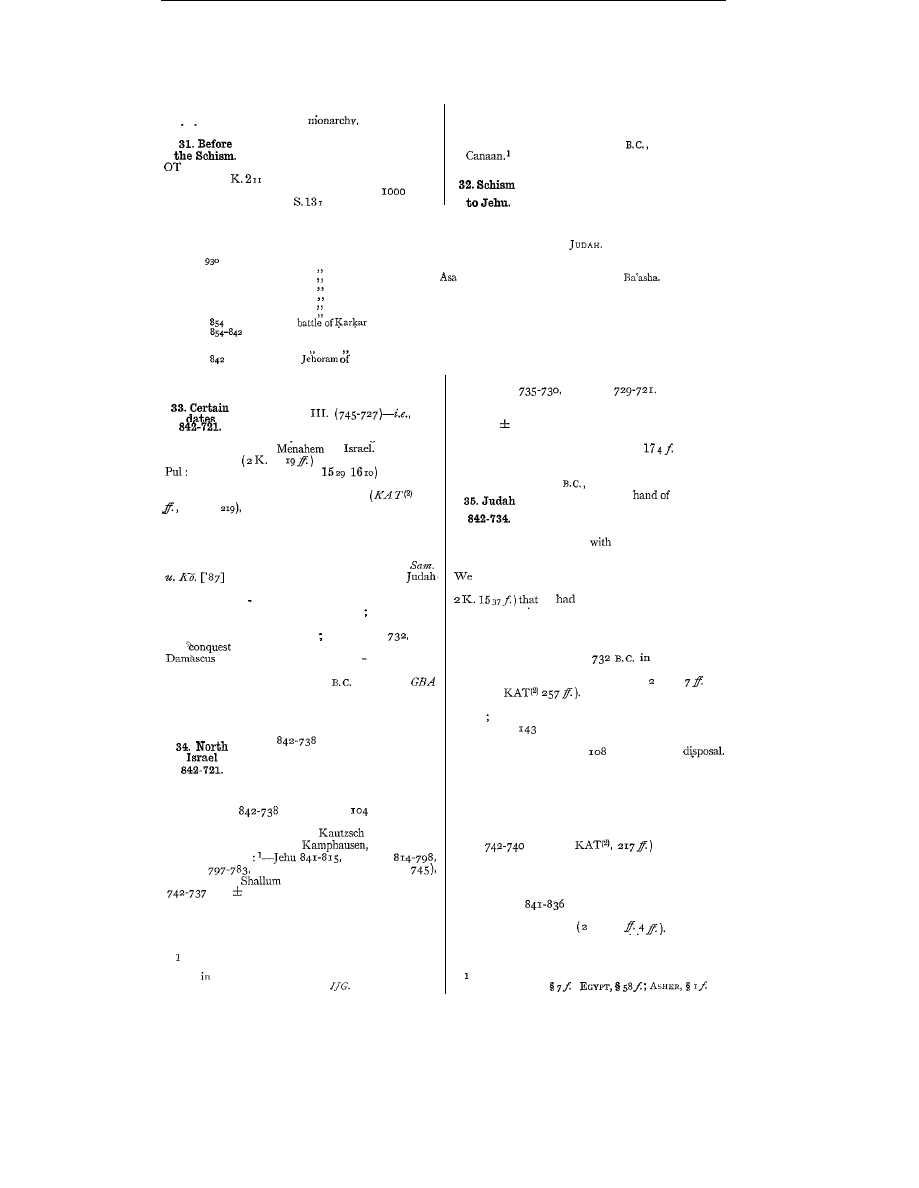

TABLE

SURVEY

D

EATH OF

SOLOMON

TO

THE

G

REAT

.

Dates.

854

842

738

734

Dates.

538

445

43

Dates.

797

795

789

743

739

736

735

733

637

597

596

I

S

R

A

EL

.

year

of

Jeroboam.

Reigns of Jeroboam,

Nadab, Baasha, Elah, Zimri,

Omri,

part

of reign of

Ahab.

Ahab at battle of

Rest of reign of

Ahah: reigns of

Ahaziah

and

Jehoram.

Death of Jehoram (at the hands of Jehu).

Tribute of

Jehu to Shalmaneser

year of

Jehu

year of

Jehoahaz

year of

Jehoash

(797-783).

ear of

Jeroboam

II.

Shallum.

year

Menahem

Tribute of Menahem to

III.

Pekahiah.

year

of

Pekah

year of

Hoshea

Fall

of

Samaria.

year of

Rehoboam.

Reigns of Rehoboam,

Abijah, Asa,

part

of

reign

Jehoshaphat.

Rest of reign of Jehoshaphat : reigns of

Jehoram

and

Ahaziah.

Death of

(at the hands of

year of

Athaliah

year

of

year

of

Amaziah

year of

(789740).

year

Jotham

(739734).

at

year of

Hezekiah

Sennacherib's army before Jerusalem.

year of

Manasseh

(692-639).

year of

Amon

(638).

year of

Josiah

Battle of

Megiddo. Jehoahaz,

king.

year of

Jehoiakim

year of

Nebuchadrezzar

Jehoiachin

king.

year of

(596-586).

FALL

OF

JERUSALEM.

of

from Babylon.

The more important dates of the succeeding centuries.

year of

Evil-Meroclach

year of Cyrus

year of

Darius

I.

of

building of second temple.

year of

Artaxerxes

I.

(464-424).

visit

of

Nehemiah

to Jerusalem. Building

of

city-wall.

of Nehemiah.

visit of Nehemiah

to

Jerusalem. On

the

advent of

and the Introduction

of the law see above,

14.

of

Persian

Power :

Alexander the Great.

Liberator

of

Jehoiachin from prison.

Beginning of

Ptolemaic

dominion in Palestine, which continued with short

till

Beginning of the

Era of the

Svrian

dominion.

Execution of

Jonathan

(leader of

revolt since

limon

High-priest and

Prince.

I.

I.

king.

Xyrcanus

and

of

Jerusalem by Pompey.

Palestine a part of the Roman Province

of

Syria.

Xyrcanus

11.

under Roman sovereignty.

of Parthians.

Antigonus

made king

the Great.

On the dates of

the

Maccabees cp We.

n.

; 2nd ed. 263, n. 3 ;

3rd

ed.

n.

797

CHRONOLOGY

CHRONOLOGY

between the sum of the years of reign from the death

of

Ahaz to the conquest of Jerusalem, and the interval

586

B

.

between 139 years of reign and

actual

years-cannot be removed otherwise than by shortening

the reign of one or more of the kings.

The account

of

the closing portion of the line of kings has already been

found to merit our confidence. The shortening must

therefore be undertaken somewhere near the beginning

of the line of kings from Hezelciah to Josiah. The most

obvious course is to reduce the long reign of Manasseh

from fifty-five years to fifty-one (We., indeed, assigns him