www.optometry.co.uk

33

Adrian Parnaby-Price MA, MB, BChir (Cantab), FRCSEd

Neurology and the eye

Case histories

Module 2 part 12 is devoted to five case histories to demonstrate the real-life

clinical presentations of neuro-ophthlamic conditions and some of the

important features to aid diagnosis and management.

The College of

Optometrists has

awarded this

article 2 CET

credits. There are

12 MCQs with a

pass mark of 60%.

The College of

Optometrists

3

A 45-year-old female barrister presented to

her optometrist with a two week history of

intermittent diplopia and mild blurring of

vision in the left eye. A friend had

commented on her small right pupil at a

barbecue party six weeks earlier, but she

had not noticed this herself. On specific

questioning, she admitted to headaches

which were either bitemporal or

occasionally felt as a sharp stab over the

left temple. She only had a three year old

pair of reading glasses with +1.50DS

correction right and left.

On examination, vision was 6/6+1 right

with a +1.25DS correction, and 6/5 left

with a +1.50/-0.50 x 85 correction. She

had no manifest squint in the primary

position. Cover testing revealed a slight

exophoria in primary position which

became manifest on right gaze. There was

anisocoria with the right pupil slightly

smaller than the left. There was no RAPD,

but the left pupil was sluggish and did not

constrict well. The media were clear and

the discs were normal. There were two dot

haemorrhages in the right mid-peripheral

retina but none in the left.

Questions

1. Which is the abnormal eye?

2. Why has this been noticed by

a friend but not by the patient?

3. What is the squint?

4. What is the significance of the retinal

haemorrhages?

5. What should the optometrist do next?

Answers

1. Which is the abnormal eye?

The left eye is abnormal. Although vision is

subjectively reduced in the left eye, in fact

the astigmatism more than accounts for

this and vision is approximately normal and

equal in both eyes with appropriate

refractive correction. There is no afferent

defect as this condition is of efferent

pathways. However, the left pupil is

abnormal and fails to respond properly to

formal pupil testing and there is an

exotropia on right gaze suggesting a left

third nerve palsy rather than an esotropia

suggestive of a right sixth nerve palsy. The

retinal haemorrhages are not directly

related to the ocular problem but may be

related to systemic disease.

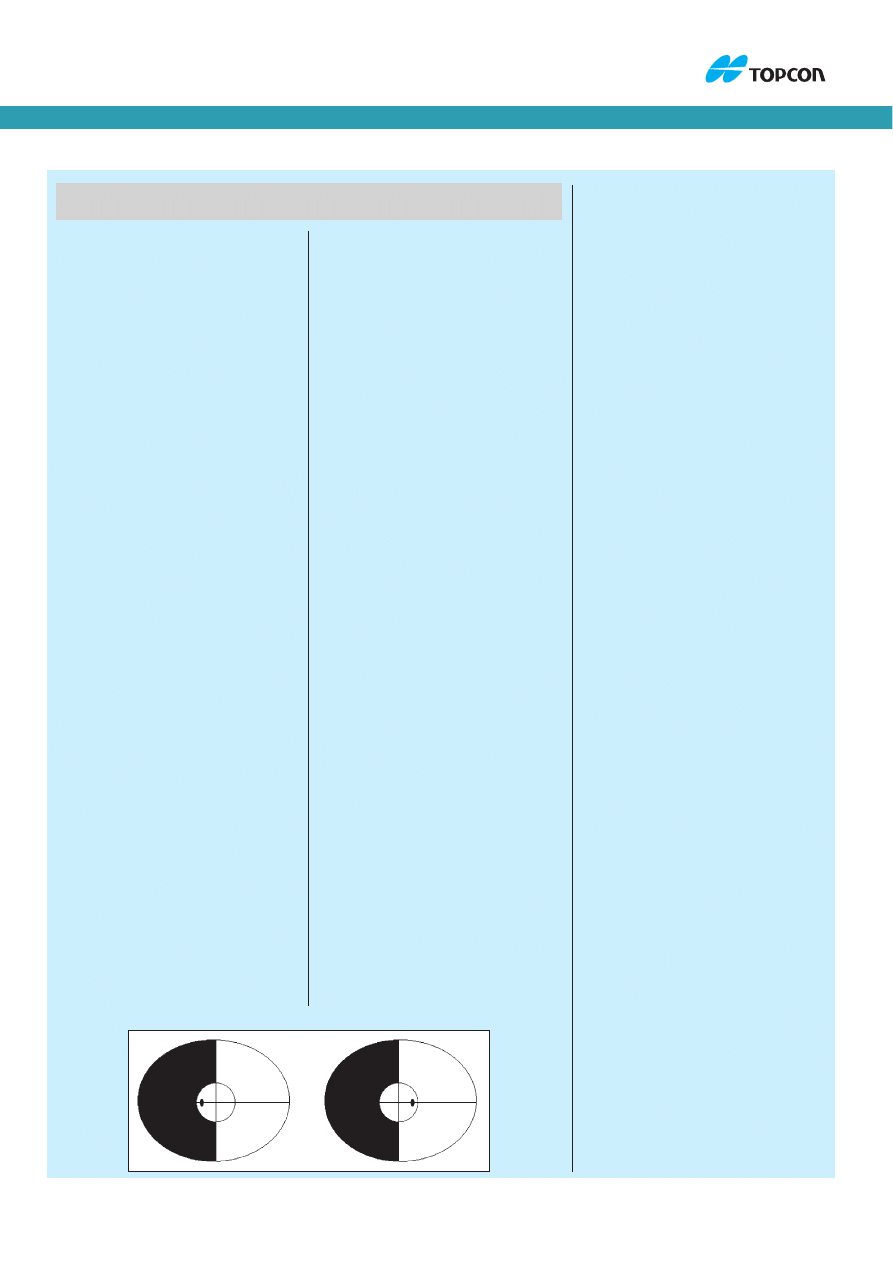

2. Why has this been noticed by

a friend but not by the patient?

The friend has noticed the anisocoria but

has mistaken the normal, smaller right

pupil as pathological instead of the larger,

abnormal left pupil. In the bright daylight

at the barbecue, parasympathetic pupil

constriction failure is more noticeable as

the affected pupil fails to constrict. In the

dimmer indoor light of the patient’s home

where she looks at herself in a mirror,

neither pupil is particularly constricted and

therefore parasympathetic anisocoria is

more difficult to see.

3. What is the squint?

The patient is most likely to be exhibiting

the effects of a left partial third nerve

palsy for the reasons outlined earlier.

4. What is the significance

of the retinal haemorrhages?

The most common causes of retinal

haemorrhages seen as an isolated finding

are diabetes mellitus or vascular

hypertension. Both of these may be

associated with nerve lesions, in

particular third nerve palsies and pupil

abnormalities.

5. What should the

optometrist do next?

The symptoms and signs are those of a

painful third nerve palsy involving the

pupil. The most important diagnoses

include a structural/compressive lesion

such as an intracranial tumour or aneurysm

which constitute a medical emergency and

indicate immediate referral to hospital

services for an urgent CT or MRI scan.

At hospital this patient was found to be

hypertensive and had a blood pressure of

230/130. She had an aneurysm of the

carotid artery in the left cavernous sinus

which was treated neurosurgically the

morning following presentation to the

optometrist. She made an almost complete

recovery of pupil and nerve palsy and did

not suffer the potential progression of the

aneurysm to cerebro-vascular accident.

CASE 1

A 36-year-old female director of sales and

marketing presented to her General

Practitioner with a history of “droopy

eyelids” in the evenings which she first

noticed in photographs taken some 12

months earlier. This had been getting worse

for around the last 3-4 months.

She had worn soft contact lenses for

12 years without significant problems and

switched to daily disposable lenses

18 months earlier. The GP requested an

optometrist check-up to exclude lens

problems as the cause and she presented

for review early next morning before flying

to a series of business meetings in the US

later the same day.

On direct questioning she reported that

the lids might be droopy either as one or

both together and she was having

occasional blurring of vision and diplopia.

This could be remedied by putting cold

compresses over the eyes for 5 minutes.

She tended to wear her lenses from early

morning until late at night although her

optometrist had suggested at review six

months earlier that she should be cutting

down on the total wearing time due to

“minor overwear problems”. She was

otherwise well although has lost some

weight recently.

Vision was 6/5+ in both eyes with

lenses. The lenses were equivalent to

spectacle correction of –5.50/-1.00 x 60

right and –4.50/-1.50 x 100 left. There

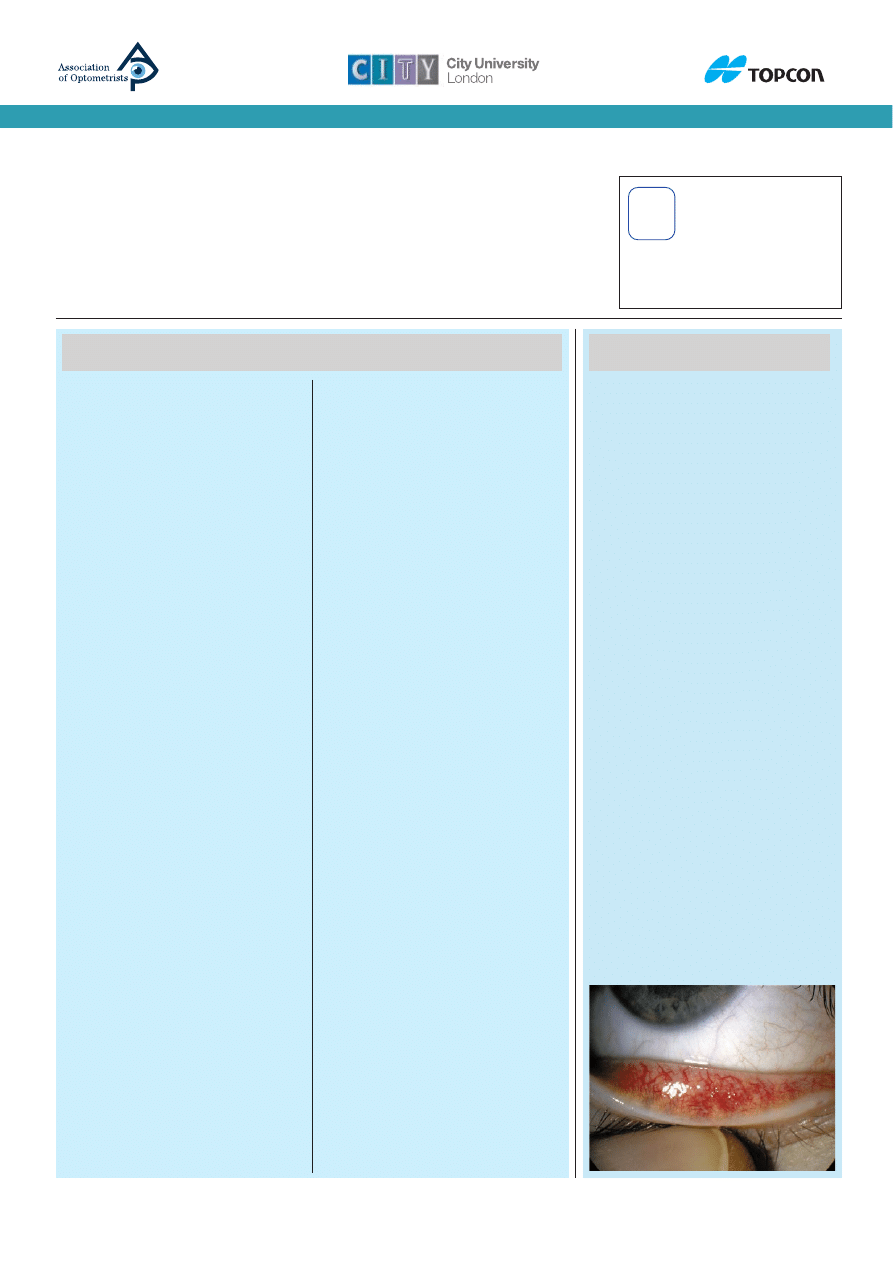

were numerous follicles and moderate

injection of the palpebral conjunctiva in

both eyes (Figure 1). Both corneae had

CASE 2

Figure 1 Conjunctival follicles

sponsored by

34

o

t

December 1, 2000 OT

www.optometry.co.uk

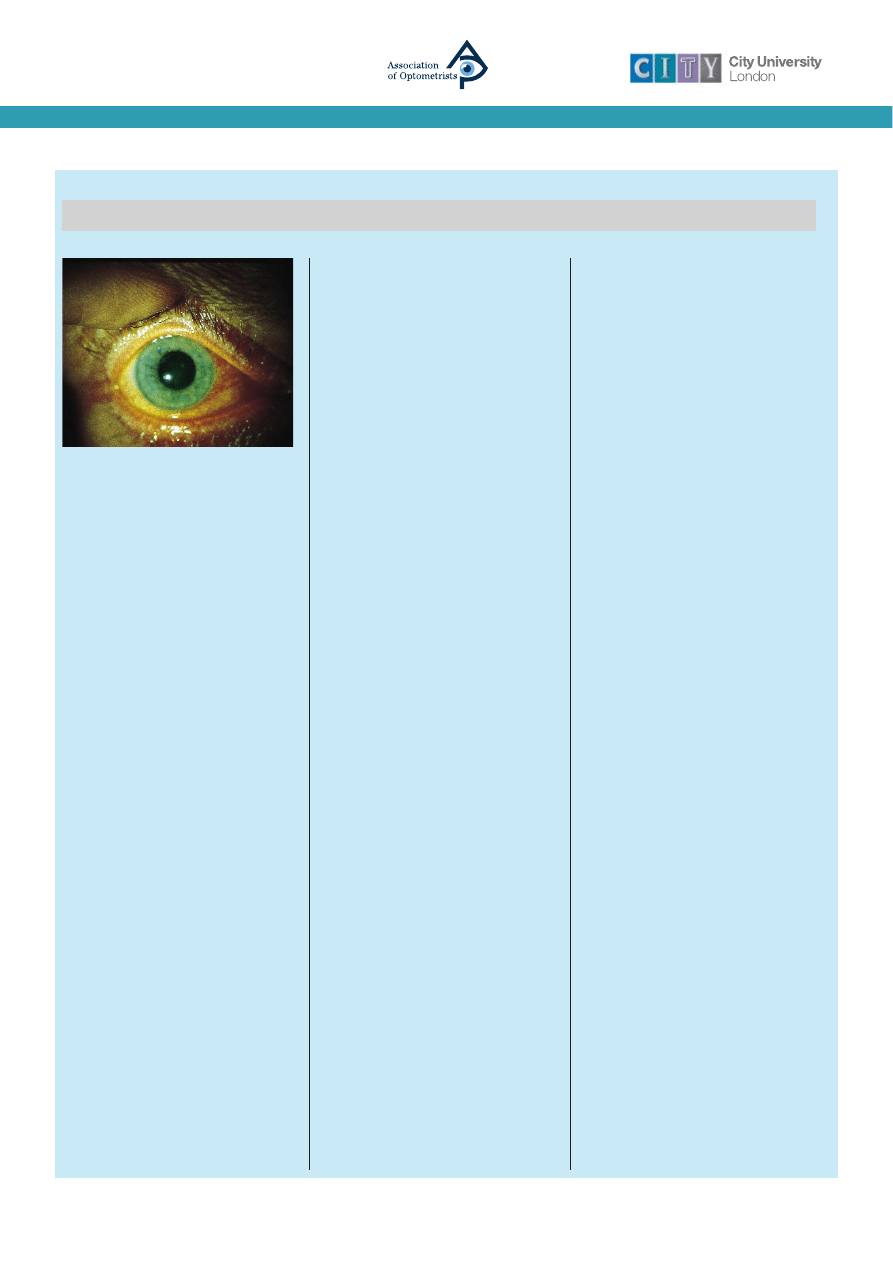

mild vessel infiltration of the cornea and

mild scleral injection consistent with

overwear (Figure 2). The eyes appeared

slightly prominent with very mild

thickening of the lids. The upper lid

margins appeared at normal position and

equal on both eyes, cutting the cornea

just below the upper limbus. There were

no afferent or efferent pupil defects.

The optometrist diagnosed a mild

overwear problem and gave appropriate

advice suggesting a review in one month’s

time.

Late in the afternoon 4 days later, she

returned to the optometrist with

significant increase in symptoms of

diplopia and lid problems since returning

to the UK the day before. She insisted

that she had reduced her lens wearing

time to only a few hours each day during

meetings.

Vision was 6/5+ in both eyes with no

pupil abnormalities. There was

improvement in the palpebral conjunctival

injection, although there were still some

follicles and the corneal vessels were less

prominent but the scleral vessels

appeared to be more full than normal,

more so on the right. The upper lids

appeared to be slightly fuller and bisected

the cornea 1.5-2mm below the upper

limbus in the right eye. Ocular motility

testing revealed diplopia in all extremes

of gaze, particularly on upgaze. There was

the suggestion of a right third nerve

weakness with abnormal abduction of the

left eye, but this was not consistent with

an internuclear ophthalmoplegia and was

not clearly apparent on cover testing. The

optometrist noted ptosis towards the end

of testing, more noticeable in the right

eye. The patient complained of discomfort

and was offered a paper napkin with cold

water to use as a compress which

appeared to reduce the ptosis and allow

re-examination after a few minutes.

Figure 2 The result of overwear

This time ocular motility appeared to

have returned to normal although

prolonged upgaze induced a slight return

of the 1-2mm ptosis of the right eyelid

which again recovered with the

application of a cold compress.

The patient was referred to a hospital

specialist for assessment.

Questions

1. What is the diagnosis and what

is the cause of the condition?

2. Why has the patient deteriorated

3. Why do the cold compresses

improve symptoms

4. What associated condition

might exhibit ocular signs?

5. What is internuclear

ophthalmolplegia?

6. What is the management

of the primary condition?

Answers

1. What is the diagnosis and what

is the cause of the condition?

Myaesthenia gravis, caused by impaired

neuromuscular transmission from the

production of auto-antibodies to

acetylcholine receptors in the motor

endplates of striated muscles.

2. Why has the patient deteriorated?

Although it is usually physical activity

which causes increase in severity of the

condition, tiredness (including that from

jet-lag) can worsen symptoms

significantly. Symptoms are characterised

by their extremely rapid variability, often

within minutes and are described by

patients as “failure to move” rather than

“tiredness and aching” such as a fatigue

following exercise.

3. Why do the cold compresses improve

symptoms?

Any lid swelling due to contact lens

problems will be aided by cold but in this

case it is more likely that simply the

resting of the extra-ocular muscles during

eye closure allowed recovery. The extreme

variability of phorias or tropias during the

same examination is very suggestive of

myaesthenia. Myaesthenia gives rise to

generalised muscle weakness, which can

mimic any of the patterns of the ocular

nerve palsies or central lesions including

gaze palsies, INO and nystagmus but the

pupils are not affected.

4. What associated condition might

exhibit ocular signs?

Patients with myaesthenia gravis have an

increased risk of other autoimmune

diseases and thyroid dysfunction is

present in 5-8% of myaesthenic patients.

Other features of thyroid eye disease

include prominent globes and orbital

congestion with injection of conjunctival

and scleral vessels and mild lid swelling

with ptosis. Extraocular muscle

involvement can mimic mild or early

nerve palsies.

5. What is internuclear

ophthalmolplegia?

Internuclear ophthalmoplegia is caused by

a lesion in the medial longitudinal

fasciculus (a neural tract running through

the brainstem carrying impulses from the

vestibular nuclei to the cranial nuclei). It

is characterised by limitation of adduction

in one eye with ataxic nystagmus in the

abducting eye and may be bilateral. The

pupils are not involved in the lesion.

Causes of lesions in this area include

multiple sclerosis, tumours and vascular

events.

6. What is the management of the

primary condition?

Ocular involvement is present in 90% of

myaesthenic patients and is the

presenting complaint in 75% with most

progressing to systemic symptoms within

two years. Diagnosis is made by

identifying acetylcholine receptor

antibodies in the blood although only

30% of myaesthenic patients have these.

If indicated, intravenous edrophonium

chloride (Tensilon) relieves symptoms and

signs immediately (particularly of ptosis)

and is diagnostic. Electromyelography can

be helpful but is rarely used in clinical

practice.

Ocular myaesthenia alone may be

managed by ocular occlusion, prism

spectacles, oral pyridostigmine and

systemic steroids. Surgical thymectomy

may be indicated and plasmaphoresis

has been used. It is important to

monitor thyroid status after

diagnosis.

In this patient treatment with oral

pyridostigmine and reduction in contact

lens wear time did not significantly

improve the scleral and episcleral

injection although the corneal vessels

regressed somewhat. Symptoms of

diplopia were completely alleviated

and the ptosis has resolved. She

remains well two years after initial

presentation.

CASE 2

continued

www.optometry.co.uk

35

Module 2 Part 12

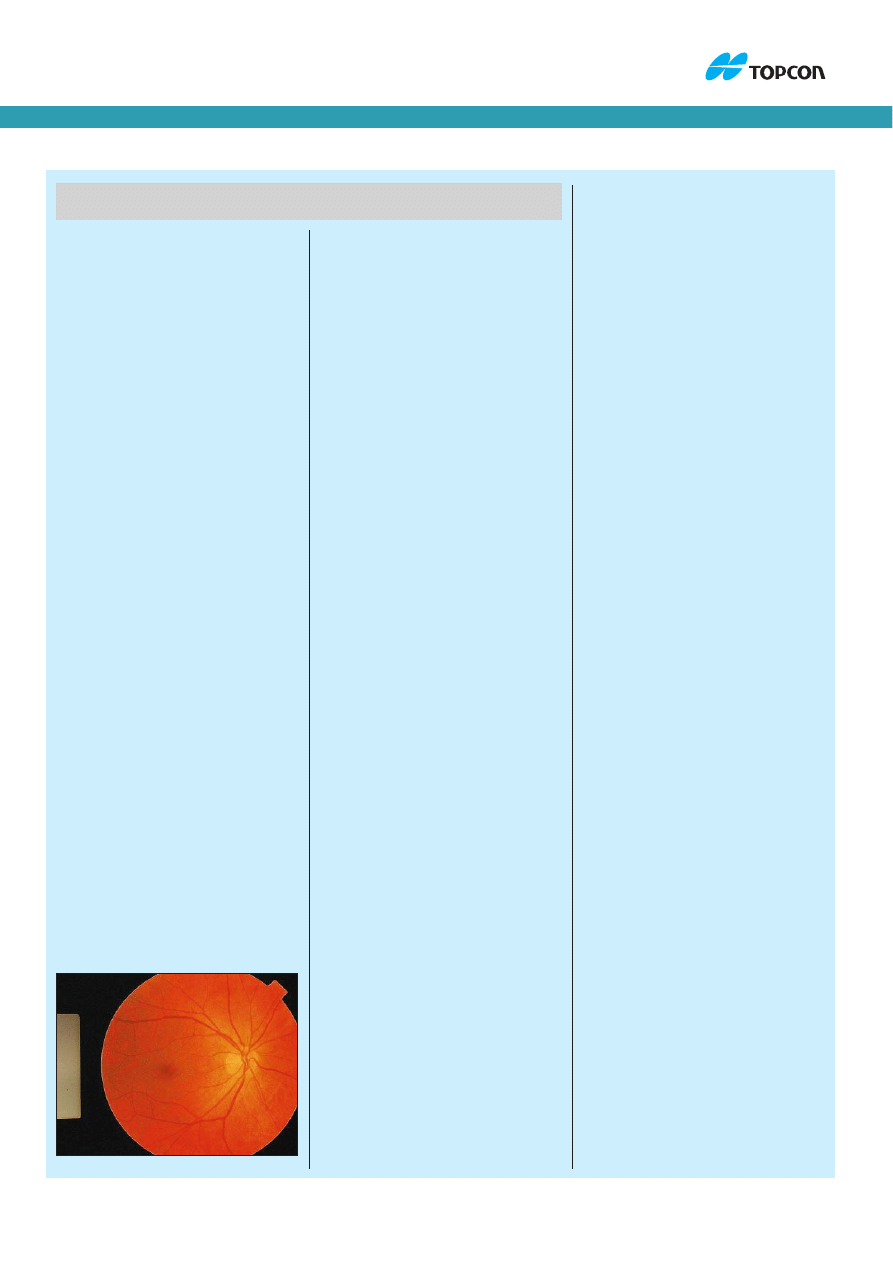

Figure 3 Optic atrophy

A 23-year-old fifth year medical student

presented to his ophthalmology lecturer

during a clinical attachment. He complained

of a left retrobulbar ache over the previous

four days and some blurring of vision in the

left eye over the last 24-48 hours. He was

otherwise fit and well.

Vision was 6/12 right, 6/9 left unaided

with no improvement in acuity with pinhole.

Subjective red appreciation was reduced in

the right eye but normal in the left. Ishihara

colour vision was 10/16 + test plate right,

16/16 + test plate left. Ocular movements

were full with no diplopia or obvious

restriction of movement although there was

a slight increase in the retrobulbar ache in

the left eye on extreme version. The right

eye was white with no anterior segment

pathology, but there was moderate injection

of the scleral and conjunctival vessels of the

left eye with cells and flare in the anterior

chamber. There was a right RAPD. After

dilation, the right optic disc was pale

(Figure 3) although the left disc was

normal.

After more careful questioning, the

patient gave a history of a temporary loss of

vision in the right eye some 4 years earlier

which had apparently recovered without

treatment. The ophthalmologist who had

seen him during that episode at the

student’s home town had not offered a

specific diagnosis but seemed confident that

there would be no sequelae. He also reported

an episode of mild weakness of his left hand

and lower arm about six months earlier

which had again resolved after 2-3 weeks for

which he did not seek medical advice. On

physical examination the tendon reflexes of

the arms were asymmetrical with increased

responses on the left (upper motor neurone

pattern).

Questions

1. What is the diagnosis in the left eye?

2. What is the treatment

for this condition?

3. What is the likely pathology

in the right eye?

CASE 3

4. Are the two conditions associated?

5. What investigations might be

helpful in establishing a diagnosis

for the right eye?

6. What are the management options for

the right eye and was the previous

ophthalmologist justified in not

venturing likely underlying diagnostic

possibilities?

Answers

1. What is the diagnosis in the left eye?

Anterior uveitis (iritis)

2. What is the treatment for this

condition?

Topical steroids to suppress inflammation

and mydriatics to relieve pain and prevent

posterior synaechiae. Posterior synaechiae

results in a ‘fixed’ pupil caused by leakage of

protein-rich serum and cells into the

aqueous blocking the area between the pupil

margin and the anterior lens.

3. What is the likely pathology in the

right eye?

Optic atrophy. In view of the suspicion of

other neurological abnormalities in this age

group the most likely underlying diagnosis is

multiple sclerosis suggesting that the optic

atrophy is secondary to old optic neuritis.

Optic neuritis can affect any part of the

optic nerve but will only produce clinical

changes if the portion immediately adjacent

to the globe is involved. This is only the

case in a minority of cases. In an acute

attack, macular exudates are relatively

frequent if the disc is involved as protein

and lipid-rich fluid leaks through diseased

vessel walls, forming linear streaks (macular

star) as deposits track along the nerve fibre

layer. In addition, the cerebrospinal fluid

(CSF) may contain inflammatory cells.

Other important differential diagnoses in

this patient include other inflammatory

conditions such as Behcet’s disease,

congenital and hereditary optic atrophy (but

not likely in view of the recovery of this eye

and the normal fellow eye), choroiditis and

retinitis pigmentosa (again, unlikely in view

of the absence of other findings). Optic

nerve compression of the right eye and toxic

or infective conditions also seem unlikely.

4. Are the two conditions associated?

Yes. Demyelinating disease (multiple

sclerosis) is the result of aberrant leucocyte

activity in the CNS, which is embryologically

and immunologically similar to the eye.

Uveitis and multiple sclerosis are therefore

likely to represent differing targets of a

similar malfunction in the immune system

and there is a strong association of uveitis

in patients with multiple sclerosis. Because

uveitis can be treated and can result in

severe ocular pathology, it is very important

to actively exclude uveitis in any patient

with multiple sclerosis who complains of

visual loss, even in those with previous optic

neuritis and during relapses at other sites.

5. What investigations might be helpful

in establishing a diagnosis for the right

eye?

During acute CNS inflammation, lumbar

puncture to obtain CSF samples can show

antibodies and cells characteristic of disease.

In old disease or in remission this is unlikely

to yield a positive result. MRI scanning will

show current or old areas of demyelination

and is the most reliable diagnostic tool.

What are the management options for the

right eye and was the previous

ophthalmologist justified in not venturing

likely underlying diagnostic possibilities?

Up to approximately 60% of patients with

optic neuritis will go on to develop other

clinical signs of multiple sclerosis in later

life. However, the diagnosis of multiple

sclerosis is made only when two or more CNS

lesions can be demonstrated, separated by

time and anatomical site. In this patient, a

single episode of optic neuritis does not

meet the diagnostic requirements and even

speculation must be restricted. Even when

clearly diagnosed, use of specific

prophylactic and acute anti-inflammatory

treatments in multiple sclerosis is extremely

limited. During acute relapse, high dose

intravenous steroids will shorten the

duration of the attack but have no influence

on the severity of residual disability later on.

Interferon may influence the incidence of

relapse in certain subtypes of multiple

sclerosis in specific patients but there is

currently no clinical test to identify whether

a patient would benefit and the potential

costs and side-effects currently limit its use.

In this patient it would not be reasonable to

commence prophylactic interferon treatment

on the basis of a single episode of optic

neuritis.

In the absence of a firm diagnosis and in

the absence of a reliable prophylactic

treatment, the first ophthalmologist was

probably fully justified in not discussing the

potential underlying condition.

Six months later this patient suffered an

acute episode of paralysis of the right leg at

which time an MRI scan revealed multiple

areas of demyelination throughout the CNS.

He was not treated for the acute attack but

was subsequently commenced on interferon.

He has had specific career counselling and is

continuing with his career in medicine but

has decided to enter radiology as a speciality

as it was considered to be the area in which

any physical disability is least likely to affect

his career.

sponsored by

A 52 year old company director presented to

his optometrist with a two week history of

“blurring” of vision on looking to the right.

The optometrist noted that this was not

causing significant symptoms but suspected

that the patient was adopting a head turn

to the right to compensate. The optometrist

advised the patient to visit his GP as soon

as possible and gave a referral letter to the

patient to take with him which is

summarised as follows:

Vision right 6/12 unaided improving to

6/6 with +0.50/+0.50 x 75. Vision left 6/9

unaided improving to 6/6 with 0.00/+0.50 x

100. There is a right sixth nerve weakness

giving horizontal diplopia of two weeks’

duration. History of hypertension – on

treatment. Suggest urgent referral to

ophthalmologist for assessment.

The patient visited his GP two days later.

The GP countersigned the referral, asked the

patient to make an appointment at the local

hospital Early Referral Clinic and checked

the blood pressure which he found to be

slightly high at 170/100. He increased the

strength of the patient’s medication and

made an appointment to re-check the blood

pressure in 3 weeks. On contacting the

hospital, the patient was given an

appointment for 10 days which he missed as

he was away on business. He was first seen

at the hospital almost a month after the

optometrist’s consultation.

The duty SHO examined the patient. The

diplopia had subjectively improved over the

previous 2-3 weeks and was not causing

significant problems. The SHO confirmed a

right sixth nerve palsy which appeared fairly

marked, but was influenced by the history

CASE 4

of recent improvement and previous

hypertension. A diagnosis of ischaemic sixth

nerve palsy secondary to hypertension was

made. His notes also recorded normal

movement in the left eye, no pupil

abnormalities and normal optic discs with a

0.3 cup to disc ratio. The patient was given

an appointment in the orthoptic clinic for a

Hess chart to quantify the defect and a

return visit to the general clinic was made

for 1 month’s time.

The Hess chart revealed a fairly marked

right abduction deficit and a mild left

adduction weakness.

At the general clinic one month later, the

patient complained of worsening diplopia

and an alteration in the appearance of the

right side of the face. The diplopia was

particularly marked on right gaze and he

was no longer able to overcome this by

head turn to the right. The ophthalmologist

on this occasion found almost complete

right sixth nerve palsy and a marked left

adduction weakness. There was a mild right

facial nerve weakness but no other cranial

nerve signs. The site of the lesion was

re-diagnosed and MRI scans and neuro-

vascular studies performed.

Questions

1. Where is the lesion?

2. Why is the left medial

rectus involved?

3. What is the likely

underlying diagnosis?

4. Why is the clinical

condition changing?

5. What should be the advice to this

patient about driving?

Answers

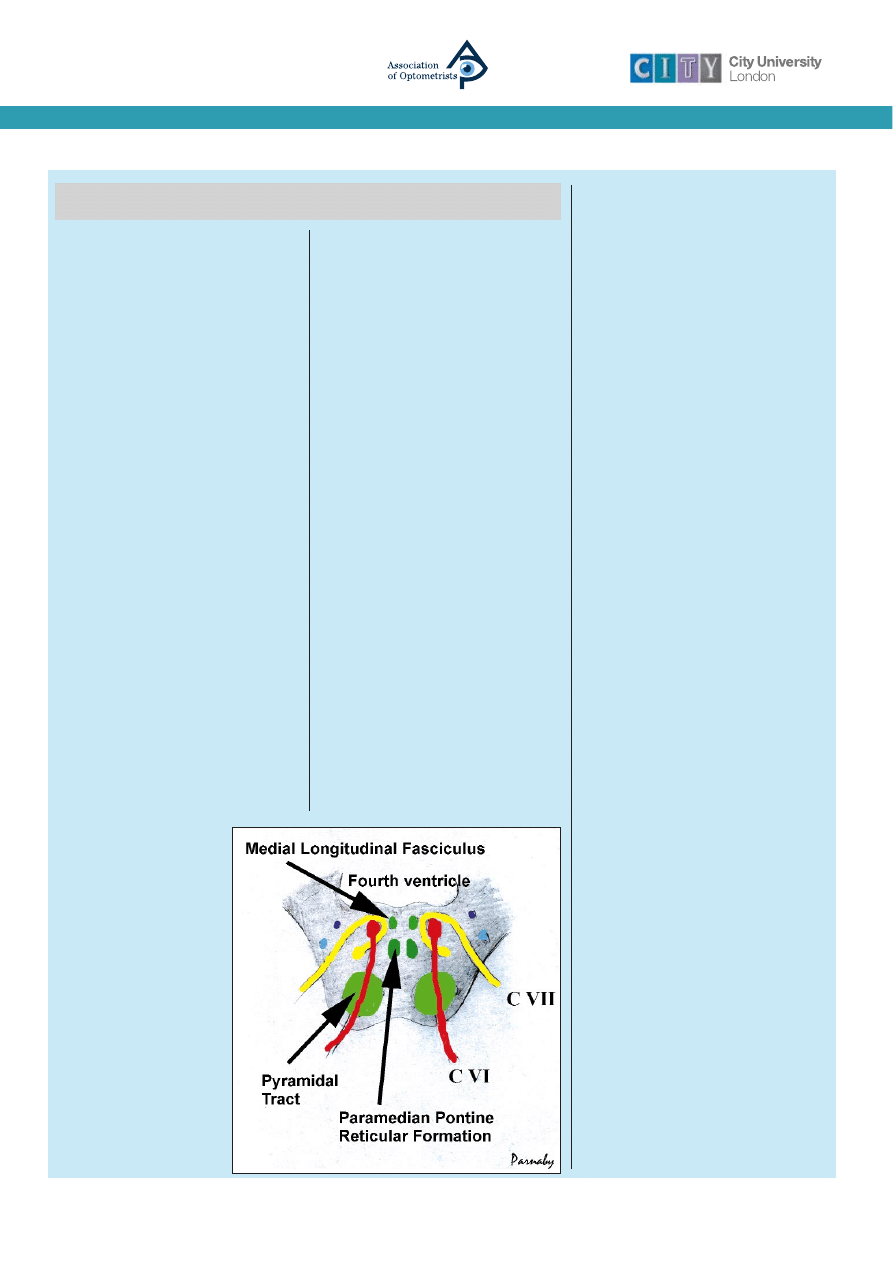

1. Where is the lesion?

Right sixth nerve nucleus. After exiting the

nucleus, there is no anatomical site which

would permit involvement of the

contralateral third nerve. The ipsilateral

seventh nerve passes backwards from its

nucleus and passes around and behind the

sixth nucleus allowing early involvement of

the seventh nerve (see Figure 4).

2. Why is the left medial rectus involved?

40% of the sixth nerve cell bodies project to

the contralateral medial rectus to cause

adduction of the fellow eye and facilitate

consensual gaze movement. Loss of this

projection therefore contributes to a gaze

palsy.

3. What is the likely underlying

diagnosis?

Ischaemia or tumour (glioma or leukaemia

deposits). In a younger age group multiple

sclerosis is also an important cause and in

children 50% of sixth nerve palsies overall

are attributable to neoplasm if trauma is

excluded.

4. Why is the clinical condition changing?

The apparent progression of the condition

strongly suggests a progressive aetiology.

The history is consistent with an early pure

right sixth nerve palsy at the presentation to

the optometrist with an early left medial

rectus weakness by the time he was first

seen in the early referral clinic which would

reduce diplopia on right gaze. As the muscle

weakness became worse, the further

reduction in right gaze and dyskinesis caused

increased symptoms. As the nuclear lesion

enlarged, the seventh nerve has become

involved.

5. What should be the advice to this

patient about driving?

The DVLC requirements for driving stipulate

that someone with diplopia may not drive a

car in the UK. Failure to contact the DVLC

with such a condition would invalidate any

insurance policies rendering the patient

liable to legal proceedings regarding fitness

to drive and driving without insurance.

In spite of an accurate anatomical

diagnosis, MRI and neurovascular imaging

failed to identify a specific lesion. A

presumptive diagnosis was made of

brainstem microvascular occlusion (limited

cerebrovascular accident (CVA)). The patient

was treated aggressively for hypertension

and hypercholesterolaemia (a risk factor for

atherosclerosis) with dietary advice and

medication including cholesterol lowering

drugs and aspirin. Six months later there has

been a slight improvement in his condition

although he remains unable to meet the

requirements for driving.

o

t

December 1, 2000 OT

www.optometry.co.uk

Figure 4

Diagram of cross-section

through lower pons

showing relationship of

sixth and seventh cranial

nerve nuclei and fascicles

36

www.optometry.co.uk

37

Module 2 Part 12

A 74-year-old retired County Council

workman presented to an optometrist after

noticing that his vision had reduced. He had

never visited an optometrist before, but was

using a pair of his late wife’s glasses.

There was some difficulty in examining

the patient due to severe spondylosis of the

neck from ankylosing spondylitis and

apparent illiteracy, but a refraction of right

+1.50/+1.00 x 90, left +2.00 DS gave an

approximate acuity of 6/12 right, 6/24 left.

Non-contact tonometry gave a reading of

22 mmHg right, 26 mmHg left. The red

reflexes were poor and the optometrist

was unable to visualise the fundus on

ophthalmoscopy. She referred the patient to

an ophthalmologist for further assessment

re glaucoma and cataracts.

There were no previous notes available in

the clinic and a routine visual field was

performed prior to clinical assessment as

shown in Figure 5. The patient stated that

he had a “cast” in the left eye as a child, but

had not noticed any problems with his

vision. He said that he had been ‘a

sharpshooter’ in the army until about 2-3

years earlier, when he had been admitted to

hospital with an illness which had “knocked

him off his feet” for a few weeks. He took no

regular medication, smoked roll-up cigarettes

and drank around 2 pints of beer daily.

Physical examination showed a thin and

frail gentleman with severe cervical

spondylosis and deep nicotine staining of

the fingers of the right hand. Goldman

tonometry was 20 mmHg right, 24 mmHg

left with moderately deep anterior

chambers, open irido-corneal angles and no

pupil defects. There was marked nuclear

sclerotic cataract in both eyes, worse in

the left, but the optic discs appeared

normal with good neural rims and small,

non-glaucomatous cups of 0.2. There was

mild retinal pigment epithelial changes in

both maculae, but clinical assessment

showed no visual defect arising from this.

Questions

1. Does the patient have glaucoma?

2. What do the visual fields show

(Figure 5) and is this consistent with

glaucoma?

CASE 5

3. Where is the lesion and what is the

likely underlying pathology?

4. Would cataracts or amblyopia in the

left eye affect the visual fields?

5. What tests would help to assess the

foveal function?

Answers

1. Does the patient have glaucoma?

No. Glaucoma is a diagnosis reached by

considering several factors including the

intraocular pressure, the integrity of the

retinal nerve fibre layer, the optic disc

neural rim (and cup extent if neural rim is

being lost) and visual fields (dependent on

the nerve fibre integrity). However,

glaucoma can be diagnosed from the

assessment of the optic disc alone, as visual

field changes are not usually evident until

substantial changes have occurred to the

disc.

Although this patient has high

intraocular pressure, there is no apparent

damage to the optic discs and the visual

fields appear not to show any defects

consistent with glaucomatous field loss. The

diagnosis in this case is of ocular

hypertension but he has a risk of about 10%

per year of progression to outright glaucoma

and will require yearly assessment to ensure

that this does not occur.

2. What do the visual fields show

(Figure 5) and is this consistent

with glaucoma?

The fields show a left homonymous

hemianopia with sparing of the left half of

the macular fields. This appearance is not

consistent with glaucoma which typically

produces arcuate scotomata arising from the

disc (=blind spot on fields). The defects

associated with glaucoma are independent

in each eye. Disc pathology (including

glaucoma) would therefore be centered

around the blind spot and would not

specifically spare the macular field. These

fields are congruous between each eye and

observe the midline based on fixation,

consistent with CNS pathology.

3. Where is the lesion and what is the

likely underlying pathology?

The field loss is to the left consistent with a

visual pathway or cortical lesion on the

right side, behind the chiasm. The macular

sparing is the critical localising feature

suggesting that the visual cortex serving the

macula (occipital tip) is spared (i.e. the

middle cerebral artery is intact) whilst the

visual cortex serving midperipheral and

peripheral fields (mesial surface of the

occipital lobe) have been compromised.

These are supplied by the middle cerebral

and posterior cerebral artery respectively,

suggesting that this patient has experienced

occlusion of his right posterior cerebral

artery, possibly during his illness two-three

years earlier (which may have been a

stroke). Smoking is a particular risk factor

for all kinds of vascular problems and poor

healthcare suggests that hypertension and

hypercholesterolaemia need to be excluded.

4. Would cataracts or amblyopia in the

left eye affect the visual fields?

Cataracts reduce perceived brightness but

the relatively good acuity suggests that

they are not seriously interfering with vision

in this patient. In other cases, severe

cataract and amblyopia may both affect the

absolute values of the test but the relative

loss of sensitivity in the visual field of each

eye individually should be able to show

visual defects clearly. In this instance, with

dense field defects, the problem should be

easy to identify. The history of good vision

in the army previously cannot be relied

upon unless corroborated by a reliable

examiner in writing. Marksmen use their

right eyes for sighting and even a relatively

dense amblyopia in the left may be missed

completely!

5. What tests would help to assess the

foveal function?

Foveal function is assessed by a variety of

measurements including acuity, colour vision

(including Ishihara colour charts) and

central fields. Specific tests include the

ability to see a red laser aiming dot when it

is focused on the fovea and the Watske-

Allen test where a slit lamp beam is

centered on the fovea and the subject is

asked whether it is complete or whether

there is a central break or distortion

consistent with abnormality, failure or loss

of the fovea (e.g. in macular oedema or

macular hole).

The patient proceeded to left cataract

surgery which improved acuity to 6/12

unaided at first postoperative visit. He

seemed pleased with the result although the

field loss remained. He defaulted from a

second follow-up appointment. His GP

visited him at home and wrote that the

patient has declined further ophthalmic

attention, as he is “most satisfied with his

position”.

Figure 5 Visual fields of patient of the patient

sponsored by

1. Which one of the following medical

conditions is a likely cause of a

retinal haemorrhage?

a. Diabetes mellitus

b. Diabetes insipidus

c.

Clotting factor 8 deficiency (von

Willebrand’s disease)

d. Platelet deficiency

2. Which one of the following

statements is incorrect?

Patients with myaesthenia gravis:

a. Have an increased risk of other

autoimmune diseases

b. Have antibodies against acetylcholine

receptors in the end-plates of sensory

nerve fibres

c.

May require surgery to control disease

d. Are likely to present initially to an

eye specialist

3. Which one of the following

statements is correct?

Patients with multiple sclerosis:

a. Are more likely to suffer with

episcleritis

b. May improve their prognosis with

aggressive immunosuppression during

acute attacks (relapses)

c.

May suffer peri-ocular pain during

relapses

d. Often become acutely photophobic

with acute optic neuritis

4. Which one of the following

statements is incorrect?

a. A pupil sparing third nerve palsy is

likely to be due to a compressive

lesion

b. Consensual eye movements are aided

by sixth nucleus projections to the

contralateral medial rectus

c.

An esotropia may be caused by a

sixth nerve palsy

d. A third nerve lesion with early

involvement of the pupil is likely to

be compressive

5. Which one of the following

statements is correct?

Parasympathetic anisocoria

is most easily seen:

a. in dim indoor light

b. in bright indoor light

c.

in daylight

d. at night-time

6. Which one of the following

statements is correct?

With regard to glaucoma:

a. An intraocular pressure of more than

40mmHg alone is diagnostic of

glaucoma

b. Can be diagnosed from assessment of

the optic disc alone

c.

Is unlikely to be severe if the visual

fields are unaffected

d. 1% of ocular hypertensives will

progress to outright glaucoma

7. Which one of the following

statements is incorrect?

In optic neuritis:

a. There is usually disc swelling,

hyperaemia and haemorrhages

b. There may be macular exudates

c.

The disc may be normal

d. There may be an associated

alteration in CSF composition

8. Which one of the following

statements regarding uveitis is

incorrect?

a. Uveitis can affect pupil movements

b. Uveitis is associated with multiple

sclerosis

c.

Topical steroids reduce the

inflammation that occurs in

uveitis

d. Miotics should be prescribed to

prevent posterior synaechiae

9. Which one of the following

statements regarding the seventh

nerve is incorrect?

a. Lower Motor Neurone involvement of

the seventh nerve will result in facial

hemiparesis.

b. The seventh nerve passes backwards

from its nucleus

c.

Anatomically, the seventh nerve is in

close proximity to the sixth nucleus

d. Pathology of the seventh nerve will

result in deafness

10. Which one of the following

statements is incorrect?

a. Internuclear ophthalmoplegia may be

mimicked by myaesthenia gravis

b. Multiple sclerosis is a cause of

internuclear ophthalmoplegia

c.

Pupil abnormalities are a common

feature of internuclear

ophthalmoplegia

d. The pupils are normal in myaesthenia

gravis

11. Which one of the following

statements is incorrect?

a. In children, 10% of sixth nerve palsies

are attributable to neoplasm if trauma

is excluded

b. 40% of the sixth nerve cell bodies

project to the contralateral medial

rectus

c.

Multiple sclerosis is a cause of sixth

nerve palsies

d. Disc swelling and peripapillary

haemorrhage are early features of

raised intracranial pressure

12. Which one of the following

statements is correct?

a. Macular sparing in occipital CVA

(stroke) suggests involvement of the

middle cerebral artery

b. Cataracts rarely give rise to formal

visual field defects

c.

Visual acuity is usually significantly

reduced in a CVA affecting the tip of

the right occipital lobe

d. A left hemianopia may be caused by a

glaucomatous loss of the temporal

right optic disc

Multiple choice questions -

Neurology and the eye - Case histories

An answer return form is included in this issue.

It should be completed and returned to:

CPD Initiatives (NOE12),

OT, Victoria House, 178–180 Fleet Road, Fleet,

Hampshire, GU13 8DA by January 10, 2001.

Please note there is only ONE correct answer

38

o

t

December 1, 2000 OT

www.optometry.co.uk

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Adrian Parnaby-Price is a

Consultant in Ophthalmic Surgery

at St George’s Hospital, London

sponsored by

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Botox, Migraine, and the American Academy of Neurology

Gods Eye Aerial Photography and the Katyn

Mettern S P Rome and the Enemy Imperial Strategy in the Principate

More Than Meets The Eye New Feats

Diet, Weight Loss and the Glycemic Index

Ziba Mir Hosseini Towards Gender Equality, Muslim Family Laws and the Sharia

pacyfic century and the rise of China

Danielsson, Olson Brentano and the Buck Passers

Japan and the Arctic not so Poles apart Sinclair

Pappas; Routledge Philosophy Guidebook to Plato and the Republic

Legions of the Eye

Pragmatics and the Philosophy of Language

Haruki Murakami HardBoiled Wonderland and the End of the World

SHSBC388?USE LEVEL OT AND THE PUBLIC

Doping in Sport Landis Contador Armstrong and the Tour de Fran

drugs for youth via internet and the example of mephedrone tox lett 2011 j toxlet 2010 12 014

Nouns and the words they combine with

więcej podobnych podstron