www.elsevier.com/locate/cuor

MINI-SYMPOSIUM: THE PAEDIATRIC HIP

(iv) Legg Calv

!e Perthes’ disease

James B. Hunter*

Consultant Paediatric Orthopaedic Surgeon, Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham NG7 2GZ, UK

Summary Many controversies remain in Perthes’. These algorithms are presented as

a way through the maze of contradictory and incomplete evidence. Catterall has

emphasised the importance of clinical examination in the assessment of cases of

Perthes’ and this is particularly important in the younger group, many of whose hips

heal very round, despite rather adverse-looking X-rays early on, because they have

maintained an excellent, almost normal, range of movements. The older child or

early adolescent with Perthes’ requires urgent attention, as the femoral head lacks

the regenerative capacity of the younger child. Before any operation in Perthes’,

action must be taken to unstiffen the hip. Containment procedures will fail if

performed on a stiff hip and even salvage procedures are best performed on a hip

that has been loosened as much as possible. Surgeons need to recall that most

untreated Perthes’ do not require intervention until the age of 40. If our

interventions on the child result in hip replacement being required in the 20’s,

then we have not done that patient a service.

&

2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Perthes’ disease is idiopathic avascular necrosis of

the femoral head in childhood. It was described

independently by Legg in the USA, by Jacques Calv

!e

in France and by Georg Perthes’ in Austria during

the first decade of the 20th century. The descrip-

tion of Perthes’ disease followed rapidly after the

intervention of the radiograph. Prior to that, it had

been thought to be a self-limiting infection,

possibly tuberculosis. In many countries the disease

is known as Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes’ disease, or LCP. In

Britain the condition is generally referred to as

Perthes’ because he had recognised the fact that

this was a form of avascular necrosis.

Despite the fact that 2004 is the centenary of

Legg’s lecture at Hartford describing the condition,

there is more that is not known about Perthes’ than

is known. We do not know what causes Perthes’. We

certainly do not know what is the best way to treat

it. We are unsure of the outcome. These factors

have led to a heterogeneity of different treatment

modalities, ranging from the highly invasive to the

fully nihilistic. Very few studies are available that

give any insight into the long-term effects of the

condition.

Epidemiology

Even the incidence of Perthes’ disease is contro-

versial. Incidences are quoted per 100,000 of the

ARTICLE IN PRESS

KEYWORDS

Perthes’ disease;

Clinical features;

Investigation;

Treatment

*Tel.: þ 44-115-924-9924.

0268-0890/$ - see front matter & 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.cuor.2004.06.001

Current Orthopaedics (2004) 18, 273–283

population but also per 100,000 children.

It is

probably 1.5 to 4 cases per 100,000 of the popula-

tion, leading to a prevalence of between 6 and 12

per 100,000 of the child population. Higher inci-

dences of Perthes’ disease outside this range are

quoted, particularly for some urban areas.

The male

to female ratio is 6:1. The incidence of bilateral

Perthes’ disease is approximately 25% and in the

majority of these cases the disease does not occur

synchronously in each hip. If it does, alternative

causes should be considered, the most common of

which would be multiple epiphyseal dysplasia.

Aetiology

Theories on the aetiology of Perthes’ are multiple

and difficult to disentangle.

Growth patterns

A constant feature in papers that describe the

epidemiology and aetiology of Perthes’ is that

patients are relatively immature in that they have

delayed bone age. This was noted particularly by

Wynne-Davis and Gormley in Scotland, but also in

Birmingham and more recently in Coventry.

The

delayed bone age has been reflected in the short

stature of patients and some have found evidence

of reduced growth factors, such as somatomedins,

in patients with Perthes’ disease. Although true

bilaterality only occurs in 25%, some investigators

have found abnormalities of the contra-lateral hip,

which they believe represent the growth abnorm-

alities that cause the condition.

Genetic factors

The role of genetic factors is controversial. Wynne-

Davis originally felt that the factors affecting the

incidence of Perthes’ disease were environmental

rather than genetic. Clustering in families has,

however, been described on several occasions. It is

clear, however, that Perthes’ is not a straightfor-

ward genetic condition with a predictable mode of

inheritance.

Environment

A number of different environmental influences

have been suggested. In both Scotland and Liver-

pool, poverty has been suggested as an aetiological

factor and this came to be associated with an urban

environment.

More recently, it has been suggested

that a rural environment might be associated more

with poverty and Perthes’ disease.

Add to this that

there are several studies suggesting that there is no

relationship between the environment and Perthes’

disease and the situation is even more confusing. It

does seem to be true that the urban clustering

previously described is in fact a feature of popula-

tion density rather than true effect and this has

been most satisfactorily demonstrated in Northern

Ireland, where population mobility is more limited

and therefore long-term follow-up for epidemiol-

ogy more easy to achieve.

Trauma

The onset of symptoms is frequently associated in

the mind of patient and parent with a traumatic

episode. Until the 1950’s most aetiological theories

centred around trauma or repetitive trauma.

However, at the peak ages of Perthes’ there is no

difference in the amount and type of physical

activity taken by boys and girls, so other factors

would have to explain the discrepancy of inci-

dence.

Thrombosis and fibrinolysis

Over the last decade, interest has been focused on

abnormalities of thrombosis and fibrinolysis in the

genesis of Perthes’. Glueck originally described a

16-fold incidence of Protein C and S deficiency

(causes of thrombophilia) in patients with Perthes’

disease in Ohio, compared to controls.

Other

investigators, attempting to repeat this work,

found different abnormalities of clotting, not all

of which might be associated with a thrombotic

tendency.

Several groups have described an

association between Perthes’ and passive smoking.

Smoking has an effect on tissue plasminogen

activator levels supporting the thrombotic theory,

but is also potentially a cause of small stature and

delayed bone age. Perthes’-like changes can be

produced in the femoral head by vascular experi-

ments involving interruption of the blood supply,

particularly if this was done twice, the so-called

second infarction theory. Other investigators have

demonstrated increased blood viscosity in patients

with Perthes’ and also intra-osseous venous hyper-

tension.

Against this, a series of investigators have found

no abnormalities of the measurable parameters of

thrombosis and fibrinolysis and others have pointed

out that in the few histological specimens of

Perthes’ available, thrombosis was not a feature.

The current concept of clotting and fibrinolysis is

extremely complex. The clotting cascade is a

ARTICLE IN PRESS

274

J.B. Hunter

concept of the past and factors interact with each

other in a far from straightforward manner. Added

to this, are the considerable difficulties of perform-

ing investigations on clotting factors. Although the

jury remains out on the relationship between

thrombosis and fibrinolysis with Perthes’, further

study is definitely still merited.

Irritable hip

Episodes of transient synovitis were thought to be

associated with an increased incidence of Perthes’

disease. In fact, the relationship is the other way

round. The initial presentation of Perthes’ is that of

an irritable hip, sometimes with synovitis and

effusion. The synovitis is triggered by the subchon-

dral fracture and the initial collapse. It is certainly

not worthwhile following up all cases of transient

synovitis to see if they were early Perthes’ disease.

Natural history

The natural history of Perthes’ is normally de-

scribed in terms of the progression of the radi-

ological appearances. The clinical course of the

disease is very unpredictable. Some cases do not

present until they are well into the healing phase

and some restriction of movement or an awkward

gait has been noted, whereas others present with

pain and stiffness before any but the most subtle

radiological signs are visible.

The natural history was originally described by

Waldenstrom, whose classification is interesting, in

that the active stages of the disease were all

crammed into what he described as the evolu-

tionary stage of the disease. He felt that the

disease was prolonged in extent and this certainly

can be the case. More recently, Joseph’s group from

India have popularised the use of a classification

modified from the Elizabethtown classification,

which divides the condition into four stages;

sclerotic,

fragmentation,

healing

and

healed

(

and

This natural history study

also records the median duration of each stage and

the morphological changes as they occur, recording

the timing of epiphyseal extrusion, metaphyseal

widening and the appearance of adverse changes,

suggesting that deformation of the epiphysis occurs

during the late stage of fragmentation or in the

early stage of revascularisation. This has led to

their recommendation that any containment sur-

gery be performed before the late stage of

fragmentation. This is an important study and

together with its companion piece on the timing

of intervention for Perthes’ represents a major

contribution to the understanding of Perthes’.

Pathology

The information on the pathology of Perthes’ is

poor because it is a non-lethal condition with active

stages during childhood. Few full pathological

specimens are available and much of the informa-

tion comes from small biopsies and curettings.

It

was fairly well established that there is thickening

of the articular epiphyseal cartilage. The bony

epiphysis and the deep layers of epiphyseal

cartilage are affected by the ischaemic process

and infarct, whilst the superficial layers of the

articular cartilage continue to gain nourishment

from the joint and synovial fluid. In severe

Perthes’, the physis itself is disrupted with distor-

tion of the physeal columns and the formation of

irregular cell columns and cartilage. The physeal

distortion is seen radiologically as the metaphyseal

cysts and Gage sign. Both of these ‘‘cysts’’ in fact

contain unossified columns of cells from the

distortion of the physis. The fragmentation of the

bony epiphysis is the beginning of the repair

process, with infarcted and damaged structures

being removed prior to reossification.

Prognosis

The long-term complication for patients with

Perthes’ disease is osteoarthritis. The long-term

follow-up from Iowa shows that at 40 years of

follow-up (i.e. patients in their late 40’s and 50’s),

40% had had a joint replacement, 10% had disabling

arthritis that warranted a joint replacement and a

further 10% had Iowa hip scores less than 80.

Groups of patients followed up for less than 40

years appear to be functioning well. Between 20

and 40 years of follow-up, the majority of patients

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 1

Modified Elizabethtown classification of

disease natural history and median duration of

each stage.

Modified Elizabethtown classification

Days

I Sclerotic

220

A no loss height B height loss

II Fragmentation

240

A early B late

III Healing

550

A peripheral B41/3 epiphysis

IV Healed

Legg Calve

´ Perthes’ disease

275

ARTICLE IN PRESS

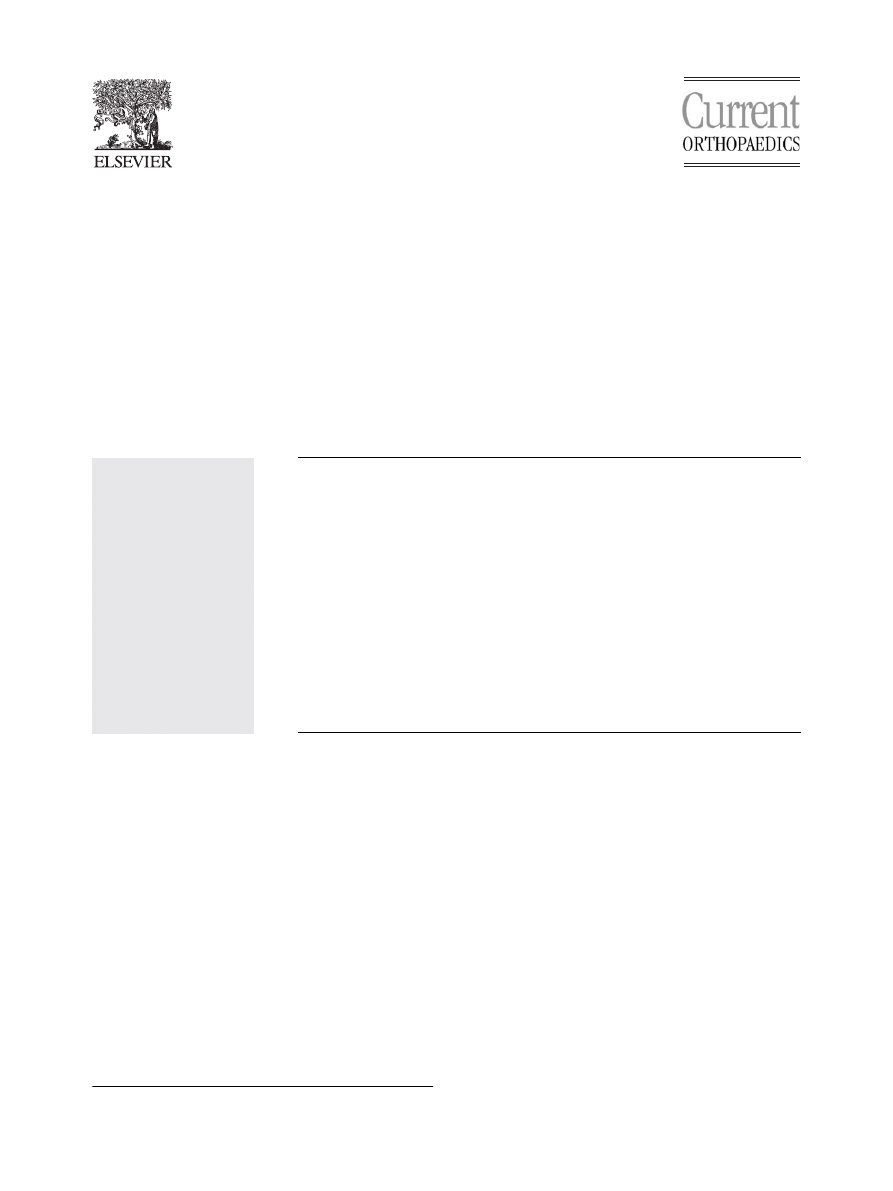

Figure 1 The stages of Perthes’ (a) Sclerotic with a sub-chondral fracture, (b) early fragmentation (femoral osteotomy

performed), (c) early healing, peripheral only, (d) late healing, (e) head healed, result is Stulberg 1, Mose good.

276

J.B. Hunter

(70–90% depending on the series) are functioning

well with little pain, despite abnormal X-rays.

The factors affecting the prognosis have histori-

cally been given as the age at onset and the shape

of the femoral head at maturity. Female gender

was thought to be a poor prognostic fracture, but

the evidence for this is limited and if the ages of

girls with Perthes’ are corrected for skeletal

maturity, their prognosis appears to be much the

same as boys. An onset of Perthes’ before the age

of 5 appears to have a good prognosis with an onset

after the age of 8 carrying a poor prognosis. This

leaves a considerable indeterminate area and

Snyder and others have reported poor results even

in very young patients with Perthes’.

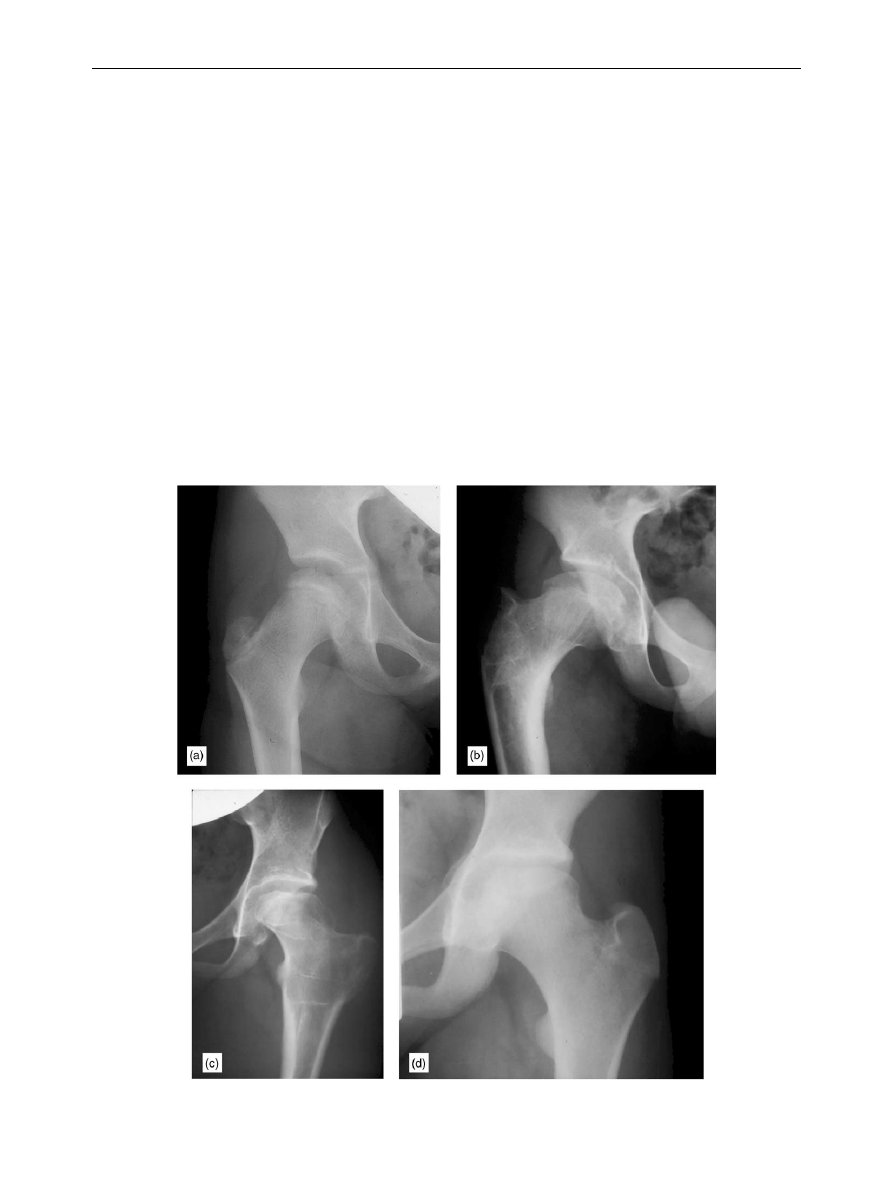

Much effort has focused on judging the shape of

the femoral head at maturity. Two methods are

commonly used, the classification of Stulberg et al

and the concentric ring method of Mose

). Neither is completely reliable.

Doubts have been cast on the intra- and inter-

observer reliability of the Stulberg classification

and in the Iowa series, even completely round

femoral heads, as judged by Mose, had severe

arthritis by the middle of their seventh decade,

although no arthritis in their 30’s.

The classic results of Catterall suggested that

less severe disease carried a better prognosis.

Follow-up was to six years (so not extensive) and

the outcome grade was that devised by Sundt,

which has not been widely used. The results suggest

that 50% or more of patients with Perthes’ do

extremely well with no intervention and this has

led to the development of severity gradings to be

applied during the course of the disease to select

appropriate patients for intervention.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

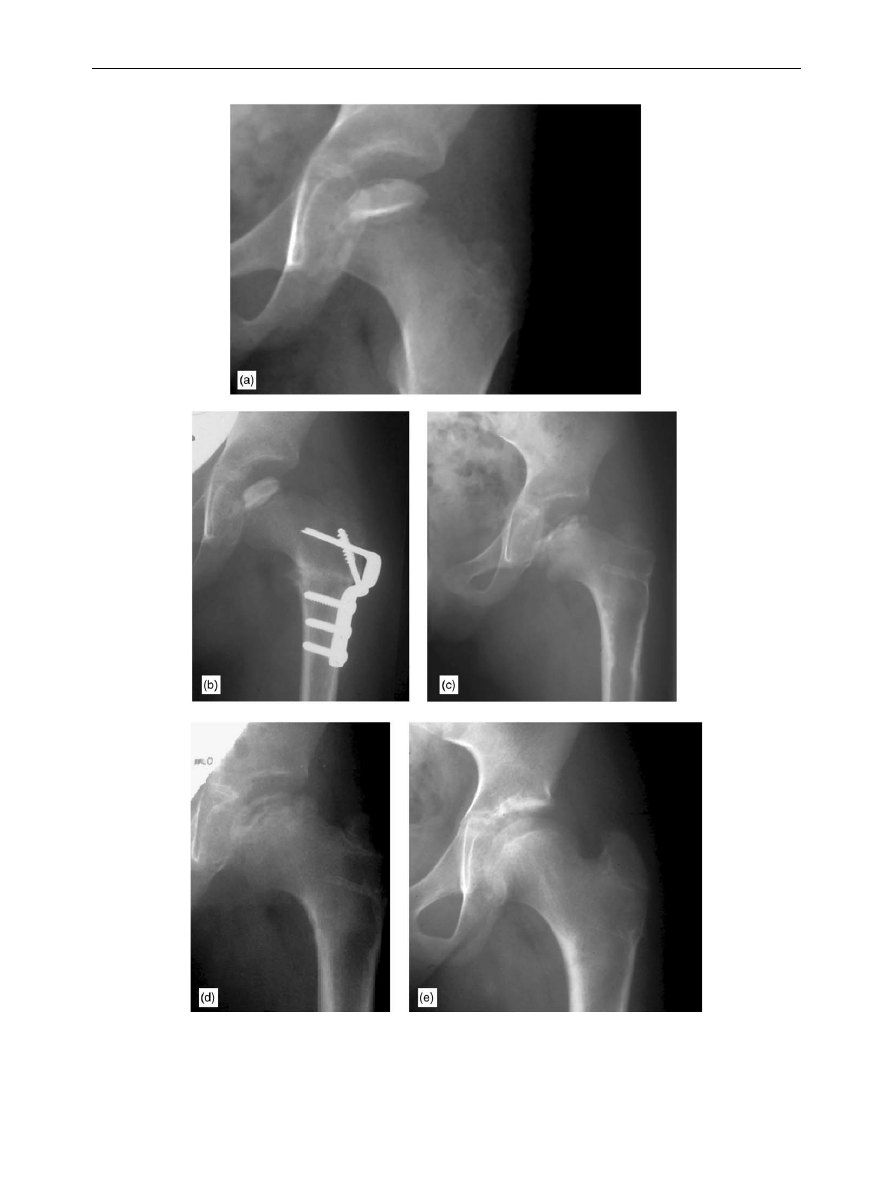

Figure 2 Example Stulberg outcome grades. (a) Grade 2, (b) Grade 3, (c) Grade 4, and (d) Grade 5.

Legg Calve

´ Perthes’ disease

277

Severity gradings in Perthes’ disease

Although the form and duration of interventions is

unclear, there is merit in trying to judge the

severity of the disease early in its natural history,

in order to spare those patients, for whom the

prognosis is good, the inconvenience of any inter-

vention whatsoever. There are three classification

systems in current use, all with their own advan-

tages and disadvantages. It is useful to determine

early in the disease whether more or less than 50%

of the femoral head is involved and especially to

determine whether a very large proportion is

involved. When less than 50% of the head is

involved the intact portion of head acts as

scaffolding for the repair process, maintaining

femoral head height and shape. This is not the

case when a larger proportion of the head is

involved

Fsevere collapse, extrusion and defor-

mity follow. A working knowledge of each of the

classification systems is useful because at different

times in the evolution of the disease each of the

systems is more applicable.

Early in the disease the most useful classification

is that of Salter and Thompson (

). This is

based on the extent of the subchondral fracture

that occurs in the sclerotic phase of the disease.

If the subchondral fracture indicates that more

than 50% of the head is going to be involved, then

early action may be indicated. The subchondral

fracture, however, is only seen in about 40% of

cases with Perthes’ and frequent X-rays may need

to be taken at the commencement of the condition

in order to visualise it at its fullest extent. My

personal practice, as regards the subchondral

fracture, is to take X-rays at six-week intervals in

the early stages of Perthes’ in order to obtain early

guidance as to the extent of the disease.

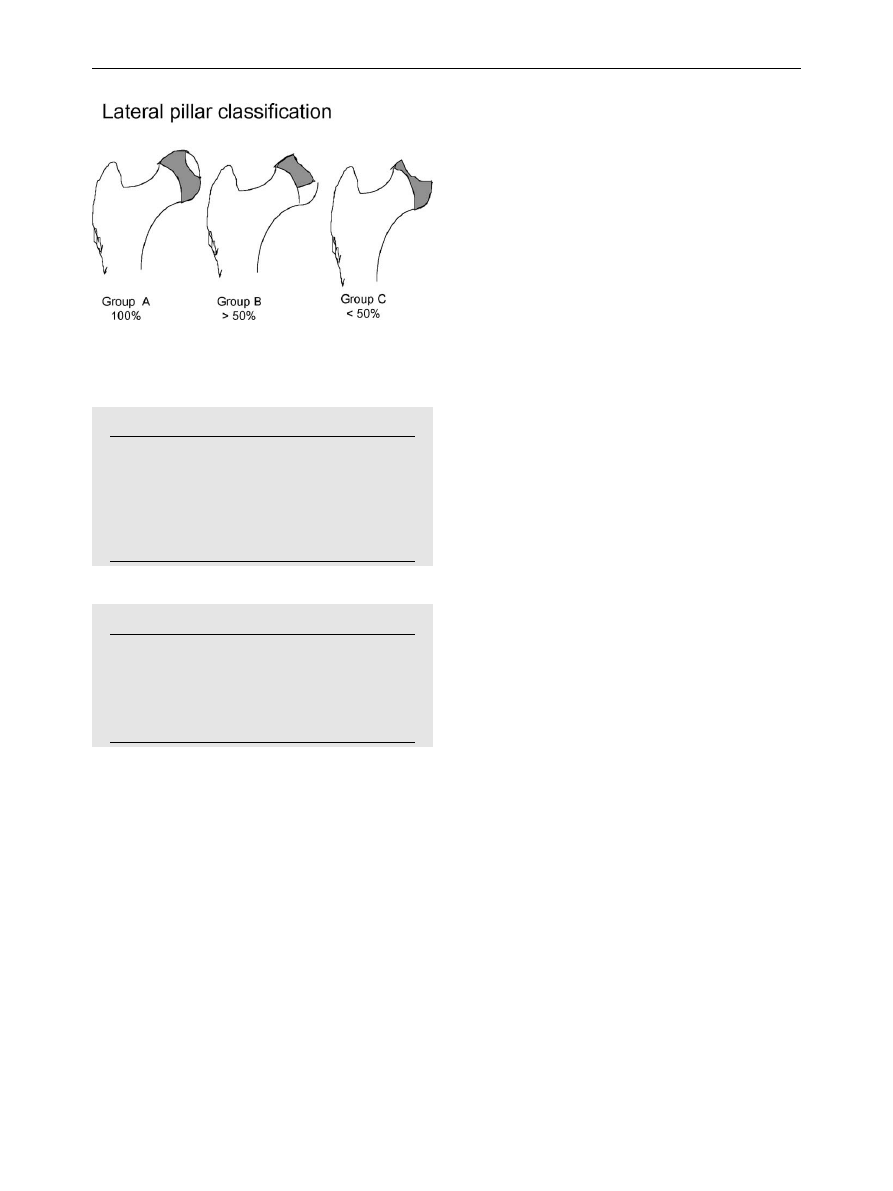

The lateral pillar classification of Herring was

published in 1992.

Femoral heads are classified

into three groups, depending on the maintenance

of height of the lateral pillar of the femoral head,

compared to the height of the lateral pillar on the

opposite normal side (

). Many investigators

have demonstrated that maintenance of lateral

femoral head height is associated with a reduction

in deformity and prevention of extrusion. The

advantages of the lateral pillar classification is that

it requires only an AP radiograph and the measure-

ments are easy to perform and to understand. The

disadvantages are that the definitive measurement

must be made at the fullest extent of fragmenta-

tion (i.e. well into the course of the disease and

therefore after the most suitable time for inter-

vention), that it is not suitable for bilateral

disease, and that femoral heads may progress from

one category to the other. Added to this, Herring

has recently presented work which has blurred the

edges of his categories making the classification

less easy to understand and to apply.

The Catterall classification was introduced in his

paper of 1971. Femoral heads are classified into

four groups and this classification too must be done

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Figure 3

Mose’s method of grading result with con-

centric circles.

Table 2

Stulberg outcome grades. There is an

increased tendency to premature osteoarthritis

with increasing grade.

Stulberg outcome grades.

I Completely normal

II Spherical with coxa magna/short neck/steep

acetabulum

III Not spherical but not flat ie umbrella or

mushroom shaped

IV Flat head with abnormal head/neck/acetabulum

V Flat head with normal head/neck/acetabulum

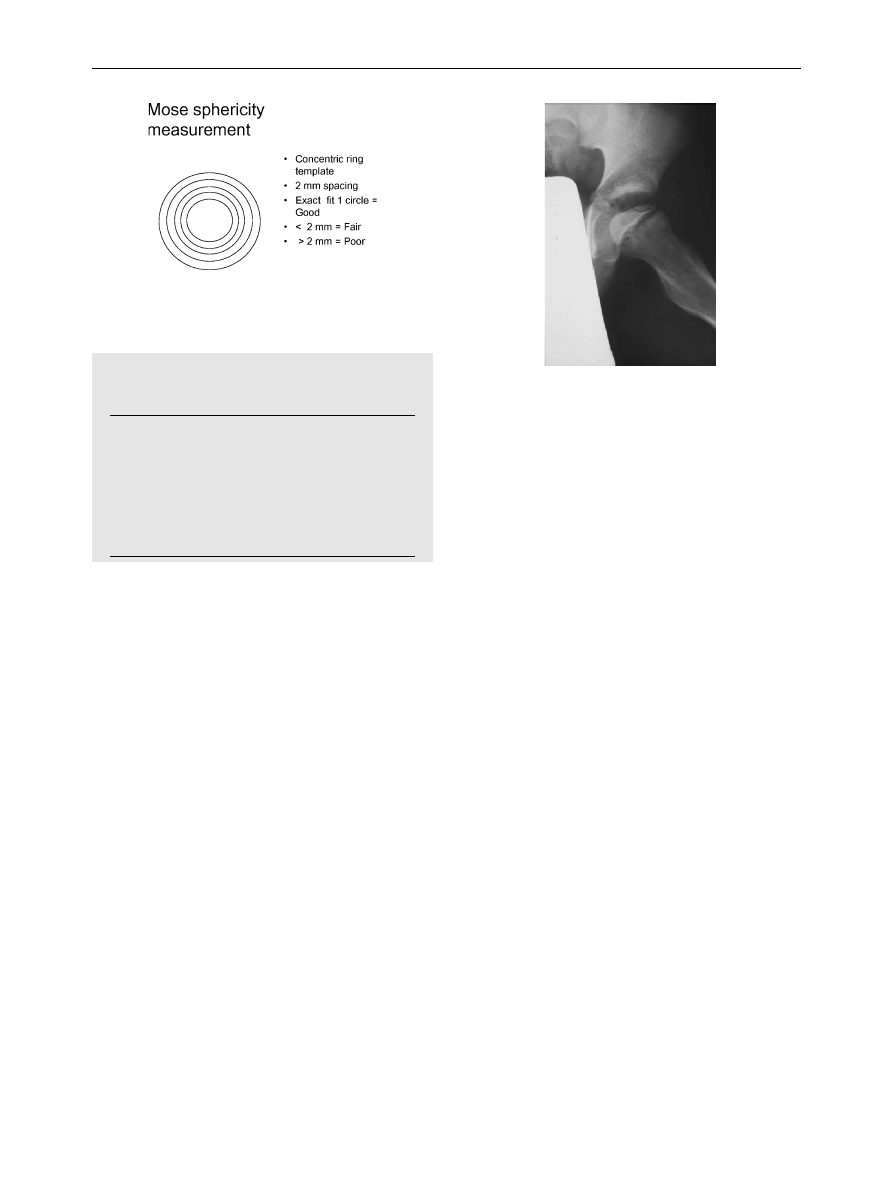

Figure 4

The sub-chondral fracture line which is the

basis of the Salter Thompson classification of severity.

This is Grade B, the more severe, as more than 50% of the

head is fractured.

278

J.B. Hunter

during the fragmentation stage, when the fullest

extent of epiphyseal involvement has been estab-

lished. Essentially, groups 1 and 2 have less than

50% head involvement and groups 3 and 4 greater

than 50% head involvement and thus the classifica-

tion can be used if no subchondral fracture line has

been visualised. Paediatric orthopaedic surgeons

have not universally found this an easy classifica-

tion to use and there have been some doubts cast

on its intra- and inter-observer reliability. The

classification puts considerable emphasis on meta-

physeal involvement and this certainly seems

appropriate as metaphyseal involvement is asso-

ciated with premature growth plate fusion and the

presence of final deformity.

In addition to the basic classification, Catterall

has introduced the clinical and radiological signs of

the head at risk (

). The clinical signs

of the head at risk are extremely important,

because although research papers on Perthes’ focus

considerably on radiological appearances, the

management of the child with Perthes’ needs to

be guided, particularly in the younger age group, by

the clinical state. Of the radiological signs, it was

originally stated that the presence of two or more

of these signs was an indicator of a poor prognosis

and therefore, since the signs appeared to be

reversible, an indication for intervention.

Investigations

Plain X-rays

AP and lateral X-rays of the hips are the mainstay of

investigation for Perthes’. Perthes’ is a protracted

disease and the repeatability of plain X-rays

enables the course of the disease to be charted.

MRI

Several classifications of Perthes’ disease based on

MRI appearances have been proposed. At this stage,

none has gained acceptance, because they have not

proved definitively prognostic and the necessity for

repeated imaging studies in Perthes’ is inconveni-

ent and expensive in the context of Perthes’.

Bone Scan

Many groups have described the benefits of using

isotope bone scanning in Perthes’. The groups in

Montpelier and Chicago suggest that pinhole colli-

mation (which provides a far more detailed picture)

is useful in recording the viability of the lateral

column of the epiphysis. This in turn may predict

deformity. Conventional bone scanning without

collimation would appear to have no role.

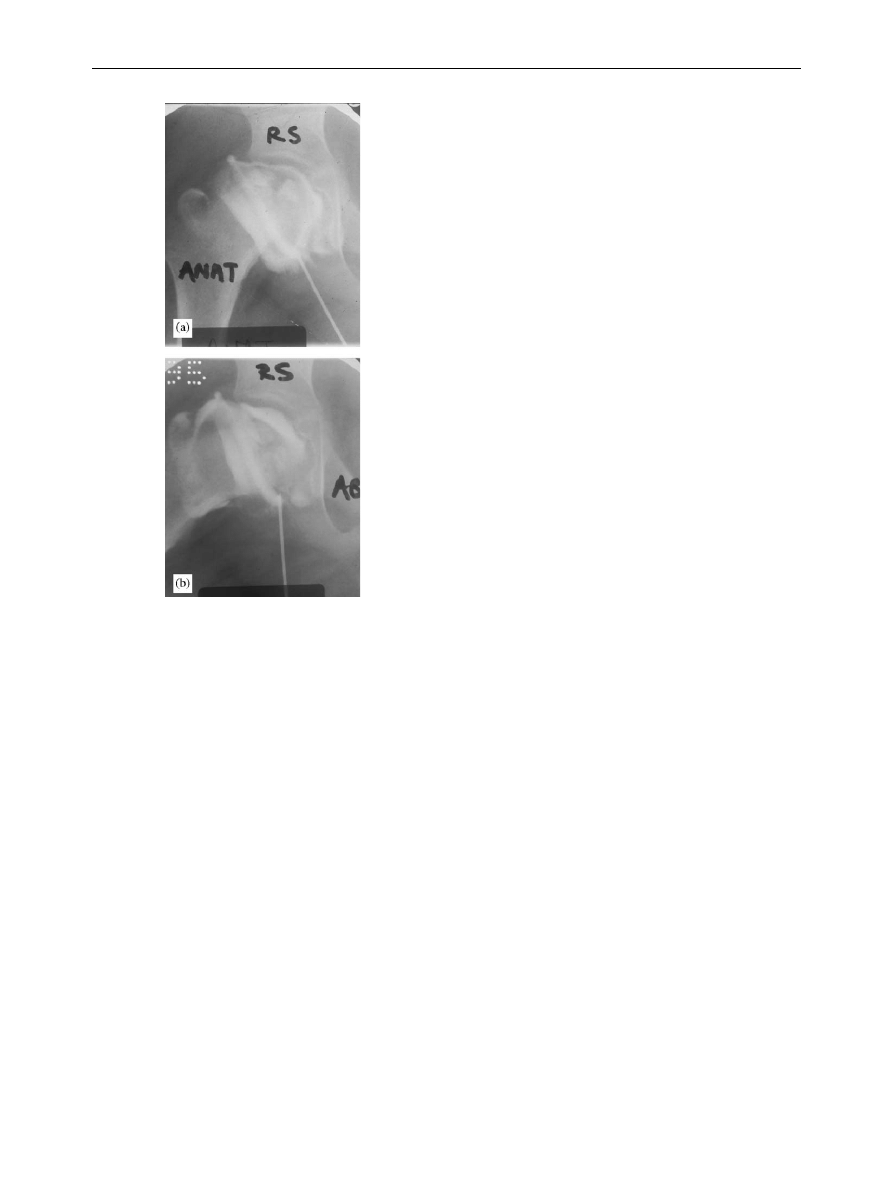

Arthrography

The arthrogram is an important investigation of the

child for whom intervention is being considered.

Catterall emphasises the importance of the arthro-

gram being dynamic. The surgeon must certainly

view how the hip moves, as medial pooling occurs

both with a flattened head that moves congruently

and with hinge abduction (

). An arthrogram

may demonstrate whether the hip is containable

(i.e. the area of disease can be located satisfacto-

rily within the acetabulum) or in non-containable

hips may demonstrate the position of best fit prior

to valgus or valgus extension osteotomy.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 4

The signs of the head at risk, clinical.

Clinical ‘‘At risk’’ signs

Older child

Heavy child

Progressive loss of movement

Adduction contracture

Flexion with adduction

Table 3

The signs of the head at risk, radiological.

‘‘At risk’’ signs

Radiological

Gage sign

Calcification lateral to the epiphysis

Subluxation

Epiphyseal angle

Diffuse metaphyseal reaction

Figure 5

The lateral pillar classification. Children in

Group A and younger children in Group C had a good

result.

Legg Calve

´ Perthes’ disease

279

Theories of treatment

Relief from weight-bearing

Because the natural history of the condition

indicates collapse and extrusion to be associated

with femoral head deformity and therefore it is

assumed a poor result, the earliest treatments

available involved prolonged relief of weight-

bearing whilst healing was allowed to progress. In

some cases this resulted in many years of bed rest

with or without an abduction frame.

Other

methods of relief of weight-bearing involved trac-

tion and the use of the Snyder sling, which kept the

affected leg in the Long John Silver position.

Containment

The main theory proposed for the treatment of

Perthes’ disease is that of containment. Essentially,

the injured femoral head is secured within the

socket and kept moving in order that after

regeneration it should be round and fully mobile.

The methods used to achieve this have varied from

plaster casts, various forms of orthotic braces to

operations. The theoretical basis of containment

was supported by animal experiments performed

on pigs.

Femoral heads subjected to an ischaemic

insult but then contained within the acetabulum of

the pig reformed a satisfactory shape, whilst those

that were not contained did not. There are some

important differences between the hips of pigs and

men; most notably the pig’s acetabulum is suffi-

ciently large to contain the entire femoral head,

which is not possible in the human. However, it is

probably

that

effective

containment

can

be

achieved if redirection into the socket is combined

with effective movement.

Containment can be achieved by orthotics or

plasters that go below the knee to effectively

control both abduction and rotation of the femur.

There is plenty of evidence to show that orthotics

that remain above the knee do not effectively

contain the hip. The use of above knee braces has

been demonstrated to be ineffective.

The

prolonged use of below knee plasters does not

allow free movement of the hip and may be

instrumental in promoting uniplanar movement of

the joint. Given the psychological problems asso-

ciated with prolonged wearing of a brace and the

dangers of missing the opportunity of surgical

intervention in the older age group, surgery seems

to be the best way to obtain containment in the

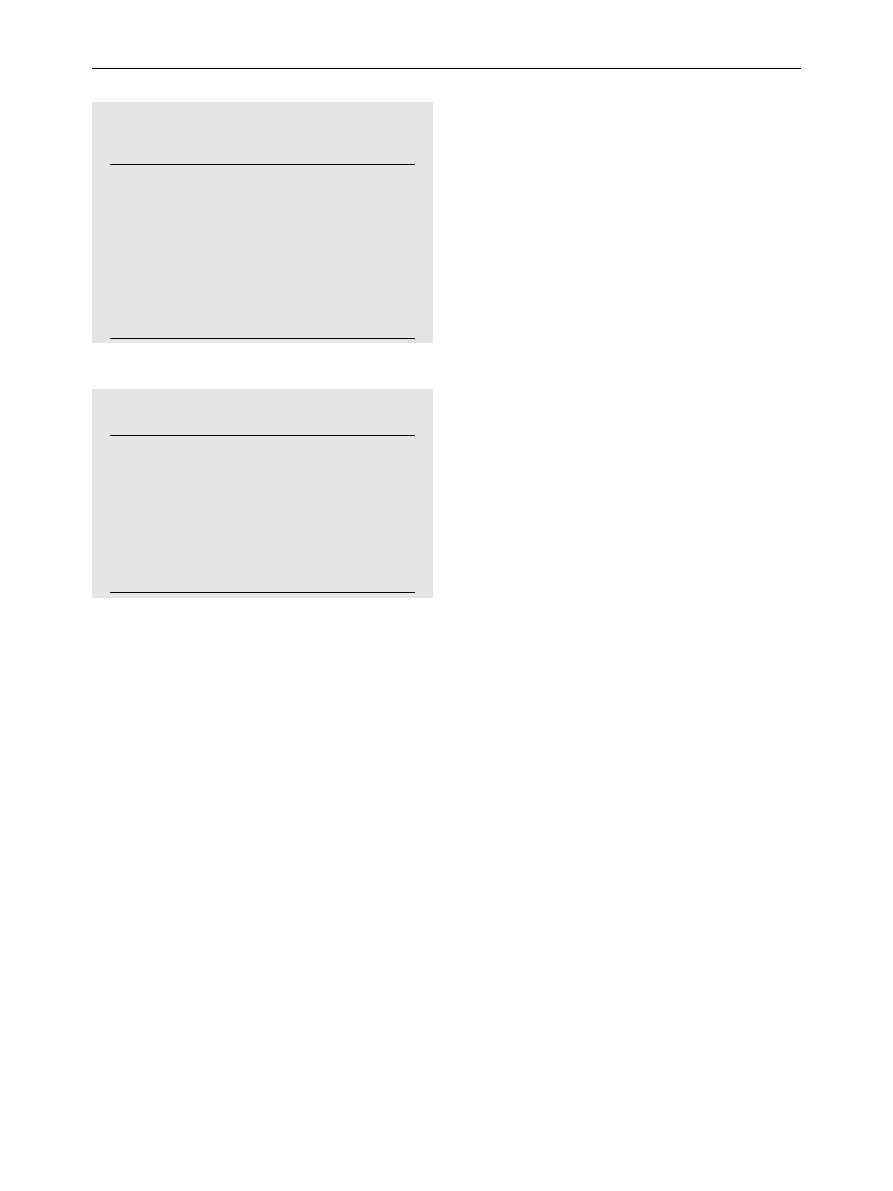

21st century. Surgical containment can be achieved

by operating either on the proximal femur or the

pelvis or indeed both.

Proximal femoral osteot-

omy is a simple and effective procedure, but in

older children may result in some shortening and an

overriding trochanter.

More and more involved

acetabular surgery has been proposed for Perthes’

over the years and provided these procedures can

be done effectively and without complication, they

are more or less equally effective

(

).

Surgical methods that do not require extensive

and prolonged immobilisation are to be preferred

because a stiff hip is never a good result. The

timing of surgery may be crucial. Certainly, opera-

tions should be done as soon as possible after it is

decided they are required. In the older child or

early adolescent this should be before there is

significant collapse of the femoral head. Early

surgery may accelerate the natural history and

indeed the fragmentation stage may be avoided

altogether after appropriate early surgery.

Although this is the centenary of Perthes’, there

are no good quality comparative studies of treat-

ment modalities. The older studies contained very

little information on the severity of the Perthes’

that was being treated and there are no modern

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Figure 6 Hinge abduction of the femoral head demon-

strated on arthrogram.

280

J.B. Hunter

randomised studies. Over the last decade an

American multi-centre study, which is essentially

a set of synchronous case series, has been

conducted under the auspices of Dr Herring.

Publication is awaited. The initial presentation

suggested that all conservative methods performed

the same as each other, as did all operative

methods.

In the age group 8 and over, there

appeared to be clear benefit from being treated by

surgery. Surgery reduces the duration of the disease

and results in rounder femoral heads.

Salvage procedures

Children who have had Perthes’ and present with

deformed femoral heads, difficulties walking, stiff-

ness and pain, require treatment, even if that

treatment cannot be with the objective of creating

a round femoral head at maturity. The most

frequent cause of pain and stiffness is hinge

abduction, when the extruded lateral segment of

epiphysis impinges on the lateral border of the

acetabulum.

Abduction osteotomy

This osteotomy is designed to remove the impinging

segment of epiphysis from the lateral wall, allowing

the foot to be placed comfortably underneath the

pelvis and a more normal gait. It is effective at

reducing pain. In the best circumstances, because

of the restoration of movement, remodelling of the

femoral head occurs and very good results have

been reported for this procedure from Catterall. It

is important that this procedure not be performed

too early. Healing needs to have started before

abduction osteotomy is performed. There is a

conflict in the literature as to whether the

abduction should be combined with flexion or

extension. The former would better remove the

affected segment from the acetabulum, the latter

deal better with any fixed flexion.

Cheilectomy/recreation of offset

An alternative approach to the extruded fragment

is to remove it surgically. As originally proposed this

operation was done through an anterolateral

approach with simple excision of the fragment.

Many orthopaedic surgeons have had poor experi-

ences with this procedure. Stiffness of the hip joint

has been a frequent sequela and more seriously,

removal of the perichondral ring, together with the

fragment, has resulted in slipped upper femoral

epiphysis of the remaining epiphysis. This operation

had fallen into disuse until repopularised by the

Bern group, who have performed it in association

with trochanteric distalisation and surgical disloca-

tion of the hip.

When performed on a hip with an

open physis they have always stabilised the

epiphysis to prevent slipped upper femoral epiphy-

sis. Reshaping of the femoral head and recreating

the femoral offset in the manner they describe is

certainly a more thorough approach than ‘‘bum-

pectomy’’ and the long-term results of this are

awaited.

Hip Arthroscopy

Occasionally in Perthes’, healing of the epiphysis is

incomplete and patients complain of symptoms

suggestive of a loose body. If this is truly the case,

then hip arthroscopy can be very useful. It should

be noted that sometimes the ‘‘loose body’’ is not

loose at all and detaching it from the femoral head

arthroscopically can be extremely difficult.

Conclusion

Many controversies remain in Perthes’. These

algorithms are presented as a way through the

maze of contradictory and incomplete evidence

(

). Catterall has emphasised the

importance of clinical examination in the assess-

ment of cases of Perthes’ and this is particularly

important in the younger group, many of whose

hips heal very round, despite rather adverse-

looking X-rays early on, because they have main-

tained an excellent, almost normal, range of

movements. The older child or early adolescent

with Perthes’ requires urgent attention, as the

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Figure 7

Lateral augmentation acetabuloplasty for

severe Perthes’.

Legg Calve

´ Perthes’ disease

281

femoral head lacks the regenerative capacity of the

younger child. Before any operation in Perthes’,

action must be taken to unstiffen the hip. Contain-

ment procedures will fail if performed on a stiff hip

and even salvage procedures are best performed on

a hip that has been loosened as much as possible.

Surgeons need to recall that most untreated

Perthes’ do not require intervention until the age

of 40. If our interventions on the child result in hip

replacement being required in the 20’s, then we

have not done that patient a service.

References

1. Kealey WD, Moore AJ, Cook S, Cosgrove AP. Deprivation,

urbanisation and Perthes’ disease in Northern Ireland. J

Bone Joint Surg Br 2000;82(2):167–71.

2. Hall AJ, Barker DJ, Dangerfield PH, Taylor JF. Perthes’

disease of the hip in Liverpool. Br Med J Clin Res

1983;287(6407):1757–9.

3. Wynne-Davies R, Gormley J. The aetiology of Perthes’

disease. Genetic, epidemiological and growth factors in

310 Edinburgh and Glasgow patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br

1978;60(1):6–14.

4. Harrison MH, Turner MH, Jacobs P. Skeletal immaturity in

Perthes’ disease. J Bone Jt Surg Br 1976;58(1):37–40.

5. Barker DJ, Hall AJ. The epidemiology of Perthes’ disease.

Clin Orthopaed Relat Res 1986;209:89–94.

6. Glueck CJ, Glueck HI, Greenfield D, et al. Protein C and S

deficiency, thrombophilia, and hypofibrinolysis: pathophy-

siologic

causes

of

Legg-Perthes

disease.

Pediat

Res

1994;35(4 Pt 1):383–8.

7. Glueck CJ, Crawford A, Roy D, Freiberg R, Glueck H, Stroop

D. Association of antithrombotic factor deficiencies and

hypofibrinolysis with Legg-Perthes disease. J Bone Jt Surg

Am 1996;78(1):3–13.

8. Kealey WD, Mayne EE, McDonald W, Murray P, Cosgrove AP.

The role of coagulation abnormalities in the development of

Perthes’ disease. J Bone Jt Surg Br 2000;82(5):744–6.

9. Glueck CJ, Freiberg RA, Crawford A, et al., Secondhand

smoke, hypofibrinolysis, and Legg-Perthes disease. Clin

Orthop 1998;352:159–167.

10. Hresko MT, McDougall PA, Gorlin JB, Vamvakas EC, Kasser JR,

Neufeld EJ. Prospective reevaluation of the association

between thrombotic diathesis and Legg-Perthes disease.

J Bone Jt Surg Am 2002;84-A(9):1613–8.

11. Joseph B, Varghese G, Mulpuri K, Narasimha Rao KL, Nair NS.

Natural evolution of Perthes disease: a study of 610 children

under 12 years of age at disease onset. J Pediatr Orthop

2003;23(5):590–600.

12. Joseph B, Nair NS, Narasimha Rao KL, Mulpuri K, Varghese G.

Optimal timing for containment surgery for Perthes disease.

J Pediatr Orthop 2003;23(5):601–6.

13. Catterall A, Pringle J, Byers PD, et al. A review of the

morphology of Perthes’ disease. J Bone Jt Surg Br 1982;

64(3):269–75.

14. McAndrew MP, Weinstein SL. A long-term follow-up of

Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease. J Bone Jt Surg Am 1984;

66(6):860–9.

15. Snyder C. Legg-Perthes disease in the young hip: does it

necessarily do well? J Bone Jt Surg 1975;57-A:751–9.

16. Fabry K, Fabry G, Moens P. Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease in

patients under 5 years of age does not always result in a

good outcome. Personal experience and meta-analysis of

the literature. J Pediatr Orthop B 2003;12(3):222–7.

17. Stulberg SD, Cooperman DR, Wallensten R. The natural

history of Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease. J Bone Jt Surg Am

1981;63(7):1095–108.

18. Mose K. Methods of measuring in Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease

with special regard to the prognosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res

1980;150:103–9.

19. Neyt JG, Weinstein SL, Spratt KF, et al. Stulberg classifica-

tion system for evaluation of Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease:

intra-rater and inter-rater reliability. J Bone Jt Surg Am

1999;81(9):1209–16.

20. Weinstein SL. Natural history, treatment outcomes of child-

hood hip disorders. Clin Orthop 1997(344):227–42.

21. Catterall A. The Natural History of Perthes’ Disease. J Bone

Jt Surg 1971;53-B(1):37–53.

22. Salter RB, Thompson GH. Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease. The

prognostic significance of the subchondral fracture and a

two-group classification of the femoral head involvement.

J Bone Jt Surg Am 1984;66(4):479–89.

23. Herring JA, Neustadt JB, Williams JJ, Early JS, Browne RH.

The lateral pillar classification of Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes dis-

ease. J Pediat Orthop 1992;12(2):143–50.

24. Herring JA, Kim HK, Browne R. Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease: a

multicenter trial of five treatment methods. In: POSNA;

2003; Amelia Island, Florida: Paediatric Orthopaedic Society

of North America. Rosemont, Illinois; 2003. p. 26.

25. Catterall A. Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes syndrome. Clin Orthop

1981(158):41–52.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Table 6

Algorithm for management of younger

child with Perthes.

Algorithm: Age 7 and below

Stage and percentage involvement

Clinically good

Fconservative with regular

review

Clinically bad/head at risk: arthrogram

If containable operation

If not

Make containable and operate

Conservative and salvage

Table 5

Algorithm for management of older child

with Perthes’. Operation should be performed early

before any fragmentation and collapse.

Algorithm: Age 8 and above

Assess Elizabethtown stage and degree of

involvement (50%)

If healing; conservative Rx or salvage

If sclerotic or fragmented; arthrogram

If containable operation

If not

Make containable (soft tissue releases) and

operate

Conservative and salvage

282

J.B. Hunter

26. Comte F, De Rosa V, Zekri H, et al. Confirmation of the early

prognostic value of bone scanning and pinhole imaging of

the hip in Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease. J Nucl Med 2003;

44(11):1761–6.

27. Tsao AK, Dias LS, Conway JJ, Straka P. The prognostic value

and significance of serial bone scintigraphy in Legg-Calv

!e-

Perthes disease. J Pediatr Orthop 1997;17(2):230–9.

28. Brotherton BJ, McKibbin B. Perthes’ disease treated by

prolonged recumbency and femoral head containment: a

long-term appraisal. J Bone Jt Surg Br 1977;59(1):8–14.

29. Salter RB, Bell M. The pathogenesis of deformity in

Legg-Perthes’

disease:

an

experimental

investigation.

J Bone Jt Surg 1968;50B:436.

30. Martinez AG, Weinstein SL, Dietz FR. The weight-bearing

abduction brace for the treatment of Legg-Perthes disease.

J Bone Jt Surg Am 1992;74(1):12–21.

31. Meehan PL, Angel D, Nelson JM. The Scottish Rite abduction

orthosis for the treatment of Legg-Perthes disease. A

radiographic analysis. J Bone Jt Surg Am 1992;74(1):2–12.

32. Olney BW, Asher MA. Combined innominate and femoral

osteotomy for the treatment of severe Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes

disease. J Pediatr Orthop 1985;5(6):645–51.

33. Axer A, Gershuni DH, Hendel D, Mirovski Y. Indications for

femoral osteotomy in Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease. Clin

Orthop 1980(150):78–87.

34. Kumar D, Bache CE, O’Hara JN. Interlocking triple pelvic

osteotomy in severe Legg-Calv

!e-Perthes disease. J Pediatr

Orthop 2002;22(4):464–70.

35. Kim HT, Wenger DR. Surgical correction of ‘‘functional

retroversion’’ and ‘‘functional coxa vara’’ in late Legg-

Calv

!e-Perthes disease and epiphyseal dysplasia: correction

of deformity defined by new imaging modalities. J Pediatr

Orthop 1997;17(2):247–54.

36. Quain S, Catterall A. Hinge abduction of the hip. Diagnosis

and treatment. J Bone Jt Surg Br 1986;68(1):61–4.

37. Garceau G. Surgical treatment of coxa plana. J. Bone Jt Surg

1964;46-B(4):779–80.

38. Ganz R, Gill TJ, Gautier E, Ganz K, Krugel N, Berlemann U.

Surgical dislocation of the adult hip a technique with full

access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk

of avascular necrosis. J Bone Jt Surg Br 2001;83(8):1119–24.

39. Bowen JR, Kumar VP, Joyce JJ, 3rd, Bowen JC. Osteochon-

dritis dissecans following Perthes’ disease. Arthroscopic-

operative treatment. Clin Orthop 1986(209):49–56.

ARTICLE IN PRESS

Legg Calve

´ Perthes’ disease

283

Document Outline

- (iv) Legg CalvÕ Perthes’ disease

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Osteochondritis dissecans in association with legg calve perthes disease

Interruption of the blood supply of femoral head an experimental study on the pathogenesis of Legg C

Modified epiphyseal index for MRI in Legg Calve Perthes disease (LCPD)

Hip Arthroscopy in Legg Calve Perthes Disease

Legg Calve Perthes’ disease

Legg Calve Perthes disease The prognostic significance of the subchondral fracture and a two group c

Computerized gait analysis in Legg Calve´ Perthes disease—Analysis of the frontal plane

Coxa magna quantification using MRI in Legg Calve Perthes disease

Osteochondritis dissecans in association with legg calve perthes disease

Interruption of the blood supply of femoral head an experimental study on the pathogenesis of Legg C

Intertrochanteric osteotomy in young adults for sequelae of Legg Calvé Perthes’ disease—a long term

Legg Calvé Perthes Disease in Czech Archaeological Material

Legg Calvé Perthes disease multipositional power Doppler sonography of the proximal femoral vascular

Multicenter study for Legg Calvé Perthes disease in Japan

Femoral head vascularisation in Legg Calvé Perthes disease comparison of dynamic gadolinium enhanced

A recurrent mutation in type II collagen gene causes Legg Calvé Perthes disease in a Japanese family

Acute chondrolysis complicating Legg Calvé Perthes disease

Legg Perthes disease in three siblings, two heterozygous and one homozygous for the factor V Leiden

Perthes Disease

więcej podobnych podstron