Contents

lists

available

at

Resuscitation

j o

u

r n

a l

h o m

e p a g e

:

w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / r e s u s c i t a t i o n

Clinical

paper

Acute

coronary

angiography

in

patients

resuscitated

from

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest—A

systematic

review

and

meta-analysis

夽

Jacob

Moesgaard

Larsen

,

Jan

Ravkilde

Department

of

Cardiology

and

Centre

for

Cardiovascular

Research,

Aalborg

University

Hospital,

Hobrovej

18-22,

9000

Aalborg,

Denmark

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Article

history:

Received

22

June

2012

Received

in

revised

form

30

August

2012

Accepted

30

August

2012

Keywords:

Coronary

angiography

Heart

arrest

Outcome

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Introduction:

Out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

has

a

poor

prognosis.

The

main

aetiology

is

ischaemic

heart

disease.

Aim:

To

make

a

systematic

review

addressing

the

question:

“In

patients

with

return

of

spontaneous

circulation

following

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest,

does

acute

coronary

angiography

with

coronary

intervention

improve

survival

compared

to

conventional

treatment?”

Methods:

Peer

reviewed

articles

written

in

English

with

relevant

prognostic

data

were

included.

Compar-

ison

studies

on

patients

with

and

without

acute

coronary

angiography

were

pooled

in

a

meta-analysis.

Results:

Thirty-two

non-randomised

studies

were

included

of

which

22

were

case-series

without

patients

with

conservative

treatment.

Seven

studies

with

specific

efforts

to

control

confounding

had

statistical

evidence

to

support

the

use

of

acute

coronary

angiography

following

resuscitation

from

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

The

remaining

25

studies

were

considered

neutral.

Following

acute

coronary

angiography,

the

survival

to

hospital

discharge,

30

days

or

six

months

ranged

from

23%

to

86%.

In

patients

without

an

obvious

non-cardiac

aetiology,

the

prevalence

of

significant

coronary

artery

disease

ranged

from

59%

to

71%.

Electrocardiographic

findings

were

unreliable

for

identifying

angiographic

findings

of

acute

coronary

syndrome.

Ten

comparison

studies

demonstrated

a

pooled

unadjusted

odds

ratio

for

survival

of

2.78

(1.89;

4.10)

favouring

acute

coronary

angiography.

Conclusion:

No

randomised

studies

exist

on

acute

coronary

angiography

following

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

An

increasing

number

of

observational

studies

support

feasibility

and

a

possible

survival

benefit

of

an

early

invasive

approach.

In

patients

without

an

obvious

non-cardiac

aetiology,

acute

coronary

angiography

should

be

strongly

considered

irrespective

of

electrocardiographic

findings

due

to

a

high

prevalence

of

coronary

artery

disease.

© 2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

1.

Introduction

Out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

(OHCA)

has

a

poor

prognosis

and

is

a

leading

cause

of

death.

The

incidence

of

OHCA

treated

by

the

emergency

medical

service

in

Europe

has

been

estimated

to

be

approximately

275,000

persons

per

year

with

a

survival

of

10.7%

for

all

rhythms

and

21.2%

for

ventricular

fibrillation

arrest.

most

frequent

cause

of

OHCA

is

ischaemic

heart

disease.

coro-

nary

angiography

(CAG)

with

percutaneous

coronary

intervention

(PCI)

is

the

treatment

of

choice

in

patients

with

acute

coronary

syn-

drome

(ACS)

with

ST-segment

elevation

(STEMI)

or

new

left

bundle

branch

block

(LBBB)

in

the

electrocardiogram

(ECG)

without

pre-

ceding

cardiac

arrest.

prognostic

value

of

acute

CAG

following

夽 A

Spanish

translated

version

of

the

abstract

of

this

article

appears

as

Appendix

in

the

final

online

version

at

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.08.337

.

∗ Corresponding

author.

address:

(J.M.

Larsen).

return

of

spontaneous

circulation

(ROSC)

after

OHCA

is

less

clear,

especially

in

comatose

survivors.

The

topic

was

evaluated

in

the

2010

International

Consensus

on

Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation

and

Emergency

Cardiovascular

Care

Science

with

Treatment

Rec-

ommendations

(2010

recommendation

was:

acute

CAG

should

be

considered

in

STEMI

or

clinical

suspicion

of

coro-

nary

ischaemia

as

a

likely

cause

of

the

arrest,

and

that

it

may

be

reasonable

to

be

included

in

a

systematic

standardised

post

cardiac

arrest

protocol.

Several

new

studies

have

emerged.

The

aim

of

this

study

was

to

make

an

updated

systematic

review

of

the

evidence

on

performing

acute

CAG

following

ROSC

after

OHCA.

2.

Methods

The

study

was

conducted

in

accordance

with

the

principles

stated

by

the

Meta-analysis

Of

Observational

Studies

in

Epi-

demiology

(MOOSE)

group

and

the

Preferred

Reporting

Items

for

Systematic

Reviews

and

Meta-analysis

(PRISMA)

short,

we

defined

a

structured

question

describing

the

Population,

0300-9572/$

–

see

front

matter ©

2012 Elsevier Ireland Ltd. All rights reserved.

1428

J.M.

Larsen,

J.

Ravkilde

/

Resuscitation

83 (2012) 1427–

1433

Intervention,

Comparison

and

Outcome

(PICO).

This

was

followed

by

literature

search

and

critical

appraisal

of

the

evidence.

The

eli-

gible

studies

were

summarised

in

tables,

and

the

outcome

was

evaluated

in

a

meta-analysis.

2.1.

PICO

question

“In

patients

with

ROSC

following

OHCA

(P),

does

acute

CAG

with

coronary

intervention

(I),

compared

to

conventional

treatment

(C),

improve

survival

(O)?

2.2.

Literature

search

The

literature

search

was

performed

on

May

1st,

2012,

in

collab-

oration

with

experienced

research

librarians.

PubMed

search

terms

were:

“Heart

arrest”

[Mesh]

AND

(“Coronary

Angiography”

[Mesh]

OR

“Angioplasty,

Balloon,

Coronary”

[Mesh]).

Embase

search

terms

were:

“exp

heart

arrest”

AND

(“exp

angiocardiography”

OR

“exp

transluminal

coronary

angioplasty”).

SveMed+

search

terms

were:

“exp

Heart-Arrest”

AND

(“exp

Coronary-Angiography”

OR

“exp

Angioplasty,-Transluminal,

Percutaneous

Coronary”).

The

identi-

fied

records

were

managed

using

reference

management

software

(RefWorks

2.0,

ProQuest

LLC,

USA).

Duplicates

were

identified

and

deleted.

Screening

of

the

records

was

done

by

one

author

(Larsen

JM).

Reviews,

case

reports,

editorials,

letters,

comments,

conference

abstracts,

records

with

clearly

no

relevance

to

the

PICO

question,

and

articles

not

written

in

English

were

excluded.

Full

text

arti-

cles

were

evaluated

for

eligibility

by

both

authors.

Articles

without

prognostic

data

at

hospital

discharge,

30

days

or

six

months

for

patients

with

acute

CAG

or

with

double

publication

of

prognostic

data

were

excluded.

Other

literature

sources

were

screening

of

the

reference

lists

of

the

included

articles

and

2010

CoSTR

and

the

peer

review

process.

2.3.

Evidence

appraisal

The

level

of

evidence

(LOE)

was

evaluated

by

both

authors:

LOE

1—randomised

controlled

trials

or

meta-analyses

of

randomised

controlled

trials;

LOE

2—studies

using

concurrent

controls

without

randomisation

for

comparison;

LOE

3—studies

using

retrospective

controls

for

comparison;

LOE

4—studies

without

a

control

group

for

comparison;

and

LOE

5—studies

not

directly

related

to

the

spe-

cific

population.

studies

without

matched

concurrent

controls

were

classified

as

LOE

4.

The

studies

were

categorised

as

prospective

or

retrospective

as

a

simple

evaluation

of

quality.

Stud-

ies

favouring

acute

CAG

in

a

propensity

score

analysis

or

reporting

a

significant

adjusted

odds

ratio

in

favour

of

acute

CAG

or

acute

PCI

were

classified

as

“supporting”

PICO.

Studies

with

non-significant

adjusted

results

were

classified

as

“neutral”

to

PICO.

Studies

with

significant

adjusted

results

favouring

conservative

treatment

were

classified

as

“opposing”.

To

be

conservative,

case-series

without

comparison

groups

were

classified

as

“neutral”

despite

high

sur-

vival

rates

due

to

possible

selection

bias.

2.4.

Statistics

The

statistical

analysis

was

performed

with

a

significance

level

of

p

<

0.05

(Stata

11,

StataCorp

LP,

USA).

Data

was

collected

from

the

result

sections

of

the

included

articles.

Comparison

studies

were

included

in

a

meta-analysis

estimating

an

unadjusted

pooled

OR

for

survival

using

a

random-effect

model.

The

heterogeneity

of

the

studies

was

evaluated

by

the

I-squared

measure,

which

describes

the

percentage

of

variation

across

the

studies

due

to

heterogeneity

rather

than

chance.

3.

Results

3.1.

Eligible

studies

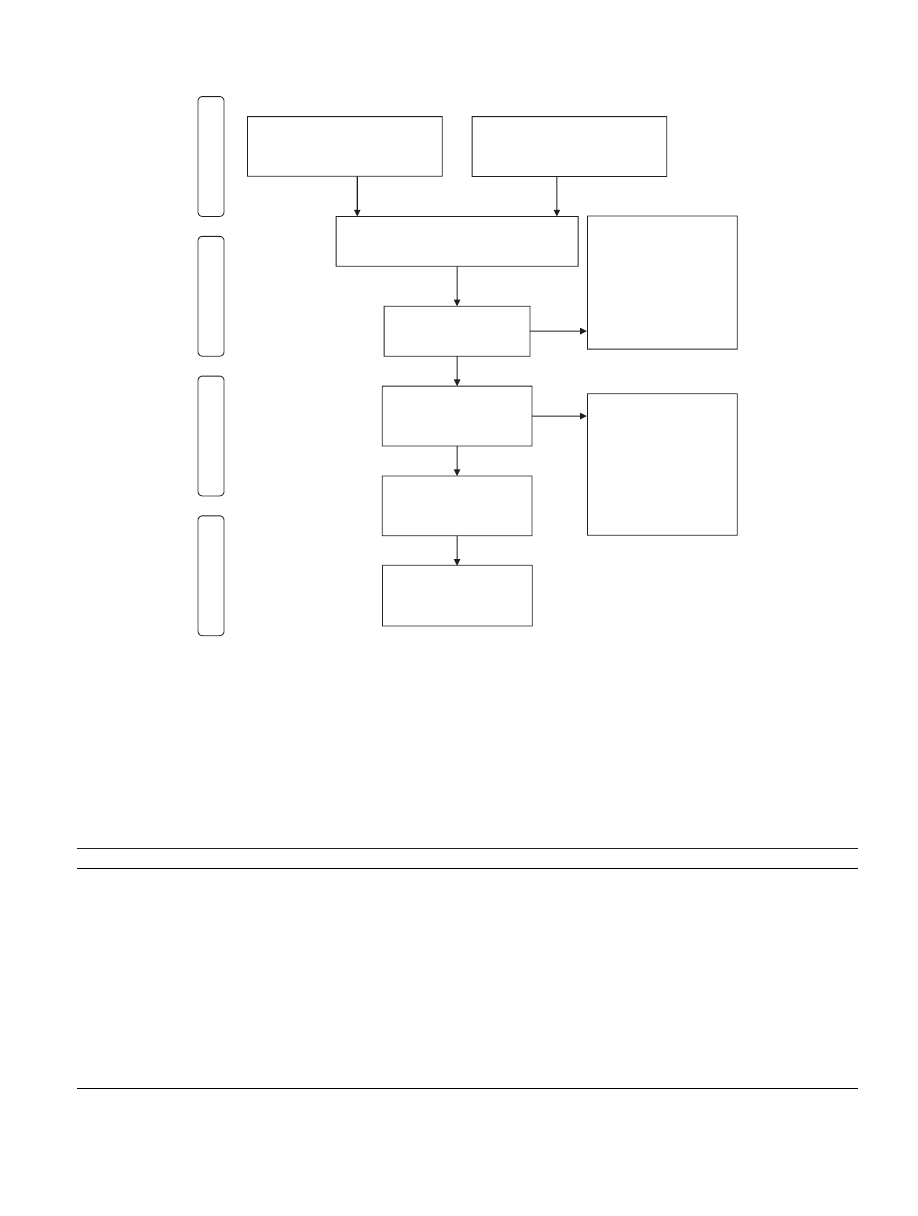

The

literature

search

is

illustrated

in

the

flow

diagram

in

Thirty-two

studies

met

the

criteria

for

inclusion

in

the

review.

Ten

were

included

in

the

meta-analysis.

Seven

studies

were

clas-

sified

as

supporting

acute

CAG

following

ROSC

after

OHCA,

and

the

remaining

25

studies

were

neutral.

Twelve

studies

were

not

considered

in

the

2010

CoSTR,

primarily

due

to

publication

after

completion

of

the

2010

CoSTR

evaluation

process.

marises

the

LOE

and

design

of

the

included

studies:

LOE

2

(one

study),

LOE

4

(22

studies)

and

LOE

5

(nine

studies).

In

all

cases,

LOE

5

was

due

to

inclusion

of

patients

with

in-hospital

cardiac

arrest

or

cardiac

arrest

without

specification

of

location.

Seventeen

studies

were

retrospective.

3.2.

Studies

on

acute

coronary

angiography

in

ST-segment

elevation

myocardial

infarction

summarises

the

characteristics

of

the

15

studies

on

acute

CAG

in

patients

with

STEMI

following

ROSC.

survival

ranged

from

41%

to

92%.

Common

characteristics

were

male

sex,

witnessed

cardiac

arrest,

OHCA

and

shockable

rhythm.

The

inclu-

sion

periods

were

generally

before

or

in

the

early

era

of

therapeutic

hypothermia

(TH),

and

the

use

of

TH

was

therefore

low

despite

a

high

prevalence

of

comatose

survivors

on

arrival

to

hospital.

The

largest

study

is

a

retrospective

case

series

of

186

consecutive

patients

undergoing

acute

CAG

due

to

ST-segment

elevation

or

Table

1

Evidence

level

and

design

of

the

studies

included

in

the

systematic

review.

Study

design

LOE

1

LOE

2

LOE

3

LOE

4

LOE

5

Studies

supporting

acute

CAG

following

OHCA

Prospective

–

–

–

Cronier

–

Dumas

Gräsner

Tömte

Spaulding

Retrospective

–

–

–

Merchant

Studies

neutral

to

acute

CAG

following

OHCA

Prospective

–

–

–

Bendz

Quintero-Moran

Kahn

Lettieri

Mooney

Möllmann

Nielsen

Peels

Pleskot

Retrospective

–

–

–

Anyfantakis

Garot

Hosmane

Knafelj

Hovdenes

Mager

Keelan

Reynolds

Markusohn

Richling

McCullough

Sideris

Wolfrum

Studies

opposing

acute

CAG

following

OHCA

Prospective

–

–

–

–

–

Retrospective

–

–

–

–

–

LOE

=

level

of

evidence

(1

– randomised

controlled

trials

or

meta-analyses

of

randomised

controlled

trials;

2

–

studies

using

concurrent

controls

without

ran-

domisation

for

comparison;

3

–

studies

using

retrospective

controls

for

comparison;

4

–

studies

without

a

control

group

for

comparison;

and

5

–

studies

not

directly

related

to

the

specific

population;

CAG

=

coronary

angiography;

OHCA

=

out-of-

hospital

cardiac

arrest.

a

Studies

not

evaluated

in

the

2010

International

Consensus

on

Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation

and

Emergency

Cardiovascular

CareScience

with

Treatment

Recom-

mendations

document.

J.M.

Larsen,

J.

Ravkilde

/

Resuscitation

83 (2012) 1427–

1433

1429

Records identified through

database searching

(n = 1484)

Screening

Included

Eligibility

Identification

Additional records identified

through other sources

(n = 5)

Records after duplicates removed

(n = 1313)

Records screened

(n = 1313)

Records excluded

(n = 1249)

Reviews; case reports;

editorials; letters;

comments; conference

abstracts; studies not

relevant to PICO; non-

English writing.

Full-text articles

assessed for eligibility

(n = 64)

Full-text articles

excluded

(n = 32)

Necessary prognostic

information not

available; double-

publication of prognostic

data; studies not

relevant to PICO.

Studies included in

the systematic review

(n = 32)

Studies included in

the meta-analysis

(n = 10)

Fig.

1.

Flow

chart

of

the

selection

of

articles

for

the

systematic

review

and

meta-analysis.

The

database

search

included

PubMed

(n

=

613

records),

Embase

(n

=

866

records)

and

SveMed+

(n

=

5).

The

records

from

other

sources

were

obtained

by

screening

reference

lists

of

the

included

studies

and

the

2010

International

Consensus

on

Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation

and

Emergency

Cardiovascular

Care

Science

with

Treatment

Recommendations

document

and

the

peer

review

process.

PICO

=

patient,

intervention,

comparison,

outcome.

presumed

new

LBBB

after

ROSC,

mainly

after

OHCA.

coronary

occlusion

was

found

in

74%.

The

remaining

patients

had

severe

chronic

stenosis.

The

survival

to

hospital

discharge

was

55%.

The

survival

at

six

months

was

54%,

primarily

with

a

good

neuro-

logical

status.

A

comparably

good

long-term

prognosis

was

seen

in

two

other

study,

comparing

direct

admittance

to

a

PCI

centre

and

transfer

from

a

referral

hospital,

demon-

strated

no

significant

difference

in

survival,

but

the

proportion

of

non-transferred

patients

with

preserved

left

ventricular

ejection

fraction

was

higher

(61%

vs

25%,

p

=

0.02).

comparison

of

Table

2

Characteristics

of

studies

on

acute

coronary

angiography

in

patients

with

ST-segment

elevation

myocardial

infarction.

Study

Inclusion

of

patients

N

OHCA

(%)

Witnessed

(%)

VF/VT

(%)

Unconscious

(%)

TH

(%)

Survival

Kahn

et

1989–1994

11

100

NA

100

64

0

51

McCullough

et

al.,

1989–1996

22

100

100

91

NA

0

41

Bendz

et

al.,

1998–2001

100

100

90

90

0

73

Quintero-Moran

et

al.,

2000–2003

63

43

100

81

NA

NA

68

(30

days)

Markusohn

et

al.,

1998–2006

25

100

92

84

72

8

76

Garot

et

1995–2005

186

84

67

NA

NA

18

55

Knafelj

et

al.,

2000–2005

72

NA

100

100

100

56

61

Richling

et

al.,

1991–2003

98

98

100

NA

37

55

(6

months)

Pleskot

et

al.,

Republic

2002–2004

100

NA

100

90

NA

70

Peels

et

Netherlands

2004–2005

44

100

NA

NA

NA

NA

50

Mager

et

al.,

2001–2006

21

NA

NA

NA

43

5

86

(30

days)

Wolfrum

et

2003–2006

33

100

NA

100

100

48

70

(6

months)

Lettieri

et

2005

100

70

90

NA

12

78

Szymanski

et

al.,

NA

NA

NA

100

NA

NA

92

(30

days)

Hosmane

et

al.,

2002–2006

98

68

90

NA

75

NA

64

Total

NA

792

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

64

(mean)

N

=

number

of

patients;

OHCA

=

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest;

VF/VT

=

ventricular

fibrillation

or

tachycardia;

TH

=

therapeutic

hypothermia;

NA

=

not

available.

a

Survival

to

hospital

discharge

unless

otherwise

stated.

b

Only

data

on

patients

with

acute

coronary

angiography

following

cardiac

arrest

is

reported

from

the

study.

1430

J.M.

Larsen,

J.

Ravkilde

/

Resuscitation

83 (2012) 1427–

1433

Table

3

Characteristics

of

studies

on

patients

with

systematic

acute

coronary

angiography

following

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

without

an

obvious

non-cardiac

aetiology.

Study

Inclusion

of

patients

n

ST-segment

elevation

or

LBBB

(%)

Significant

CAD

(%)

Angiographic

ACS

(%)

PCI

(%)

VF/VT

(%)

Unconscious

(%)

TH

(%)

Survival

Spaulding

et

al.,

1994–1996

84

63

71

69

33

93

NA

0

38

Anyfantakis

et

al.,

2001–2006

72

49

64

45

33

50

94

NA

49

Dumas

et

2003–2008

435

70

46

41

68

NA

86

39

Sideris

et

2002–2008

165

50

59

36

30

51

99

76

31

Möllmann

et

al.,

2003–2005

65

NA

NA

58

NA

NA

NA

81

(6

months)

Total

1994–2008

821

42

NA

NA

39

NA

NA

NA

41

(mean)

N

=

number

of

patients;

LBBB

=

left

bundle

branch

block;

CAD

=

coronary

artery

disease;

angiographic

ACS

=

recent

occlusion

or

irregular

lesion

at

angiography

in

resuscitated

patients;

PCI

=

percutaneous

coronary

intervention;

VF/VT

=

ventricular

fibrillation

or

tachycardia;

TH

=

therapeutic

hypothermia;

NA

=

not

available.

a

Survival

to

hospital

discharge

unless

otherwise

stated.

b

Only

data

on

patients

with

acute

coronary

angiography

following

cardiac

arrest

is

reported

from

the

study.

c

Unconscious

and

intubated.

d

ST-segment

elevation

but

not

left

LBBB

was

reported

in

study.

thrombolysis

and

acute

CAG

demonstrated

no

significant

difference

in

survival

at

six

months

(68%

vs

55%,

p

=

Two

studies

indicated

TH

to

be

feasible

in

STEMI

patients

undergo-

ing

acute

CAG

with

a

probable

positive

effect

on

good

neurological

3.3.

Studies

on

systematic

acute

coronary

angiography

in

selected

patients

with

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

of

mixed

aetiology

illustrates

five

studies

on

systematic

acute

CAG

in

patients

following

ROSC

after

OHCA

without

an

obvious

non-

cardiac

aetiology.

reported

survival

ranged

from

31%

to

81%.

The

patient

characteristics

were

more

varied

compared

to

the

pure

STEMI

studies.

TH

was

used

in

the

majority

of

the

patients

in

the

two

largest

prevalence

of

significant

coro-

nary

artery

disease

(CAD)

was

high

ranging

from

59%

to

71%.

Angiographic

signs

comparable

to

acute

myocardial

infarction

with

recent

occlusion

or

irregular

lesions

varied

from

36%

to

69%.

ST-

segment

elevation

or

LBBB

was

seen

in

31–63%.

Shockable

rhythms

ranged

from

50%

to

93%.

The

pioneering

prospective

study

by

Spaulding

et

al.

included

84

patients

with

systematic

acute

CAG

following

OHCA

without

obvious

non-cardiac

aetiology.

positive

and

negative

pre-

dictive

values

for

recent

coronary

occlusion

on

angiography

of

chest

pain

and/or

ST-segment

elevation

were

63%

and

74%,

respec-

tively.

Survival

to

hospital

discharge

was

38%.

Successful

PCI

was

an

independent

predictor

of

survival

(adjusted

OR

5.2,

p

=

0.04).

The

largest

study

including

435

patients

from

a

prospective

reg-

istry

also

demonstrated

suboptimal

but

slightly

better

diagnostic

predictive

values

of

ST-segment

elevation,

and

successful

PCI

was

an

independent

predictor

of

survival

(adjusted

OR

2.1,

p

=

0.01).

Similar

suboptimal

diagnostic

values

of

ST-segment

elevation

for

identifying

angiographic

lesions

comparable

to

ACS

were

also

seen

in

two

retrospective

newest

of

these

stud-

ies

suggested

an

extended

ECG

criterion

of

ST-segment

elevation

and/or

depression

and/or

LBBB

and/or

unspecific

wide

QRS

and/or

right

bundle

branch

block.

extended

criterion

demonstrated

a

lower

positive

predictive

value

of

48%

but

a

negative

predic-

tive

value

of

100%

with

a

potential

to

reduce

the

needed

acute

procedures.

Table

4

Studies

including

patients

with

and

without

acute

coronary

angiography

following

cardiac

arrest.

Study

Inclusion

of

patients

N

OHCA

(%)

ST-segment

elevation

or

LBBB

(%)

Acute

CAG

(%)

PCI

(%)

VF/VT

(%)

Unconscious

(%)

TH

(%)

Survival

with

and

without

acute

CAG

Bulut

et

al.,

Netherlands

NA

72

100

NA

14

11

69

69

0

40

vs

37

p

=

1.00

Merchant

et

al.,

2000–2005

110

0

12

27

15

100

NA

NA

80

vs

54

p

=

0.02

Nielsen

et

al.,

2004–2008

986

100

NA

49

30

70

100

100

63

vs

50

p

<

0.001

Reynolds

et

2005–2007

241

56

19

26

NA

39

NA

33

52

vs

p

=

0.004

Aurore

et

al.,

2000–2006

445

100

28

30

16

42

NA

NA

23

vs

10

p

<

0.001

Cronier

et

2003–2008

111

100

54

82

42

100

NA

70

59

vs

30

p

=

0.02

Gräsner

et

2004–2010

584

100

NA

26

NA

42

NA

31

52

vs

p

<

0.001

Mooney

et

al.,

2006–2009

140

100

49

72

40

76

100

100

62

vs

38

p

=

0.01

Tömte

et

al.,

2003–2009

174

100

NA

83

45

49

78

NA

52

vs

p

=

0.04

Strote

et

al.,

1999–2002

240

100

34

25

16

98

NA

0

72

vs

49

p

=

0.003

Total

NA

3103

92

NA

41

NA

62

NA

NA

56

vs

32

(means)

p

<

0.001

N

=

number

of

patients;

OHCA

=

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest;

LBBB

=

left

bundle

branch

block;

CAG

=

coronary

angiography;

PCI

=

percutaneous

coronary

intervention;

VF/VT

=

ventricular

fibrillation

or

tachycardia;

TH

=

therapeutic

hypothermia;

NA

=

not

available.

a

Survival

to

hospital

discharge

unless

otherwise

stated

with

calculated

p-values

by

Fischer’s

exact

test

or

Chi-square

test.

b

Survival

to

hospital

discharge

with

good

neurology.

J.M.

Larsen,

J.

Ravkilde

/

Resuscitation

83 (2012) 1427–

1433

1431

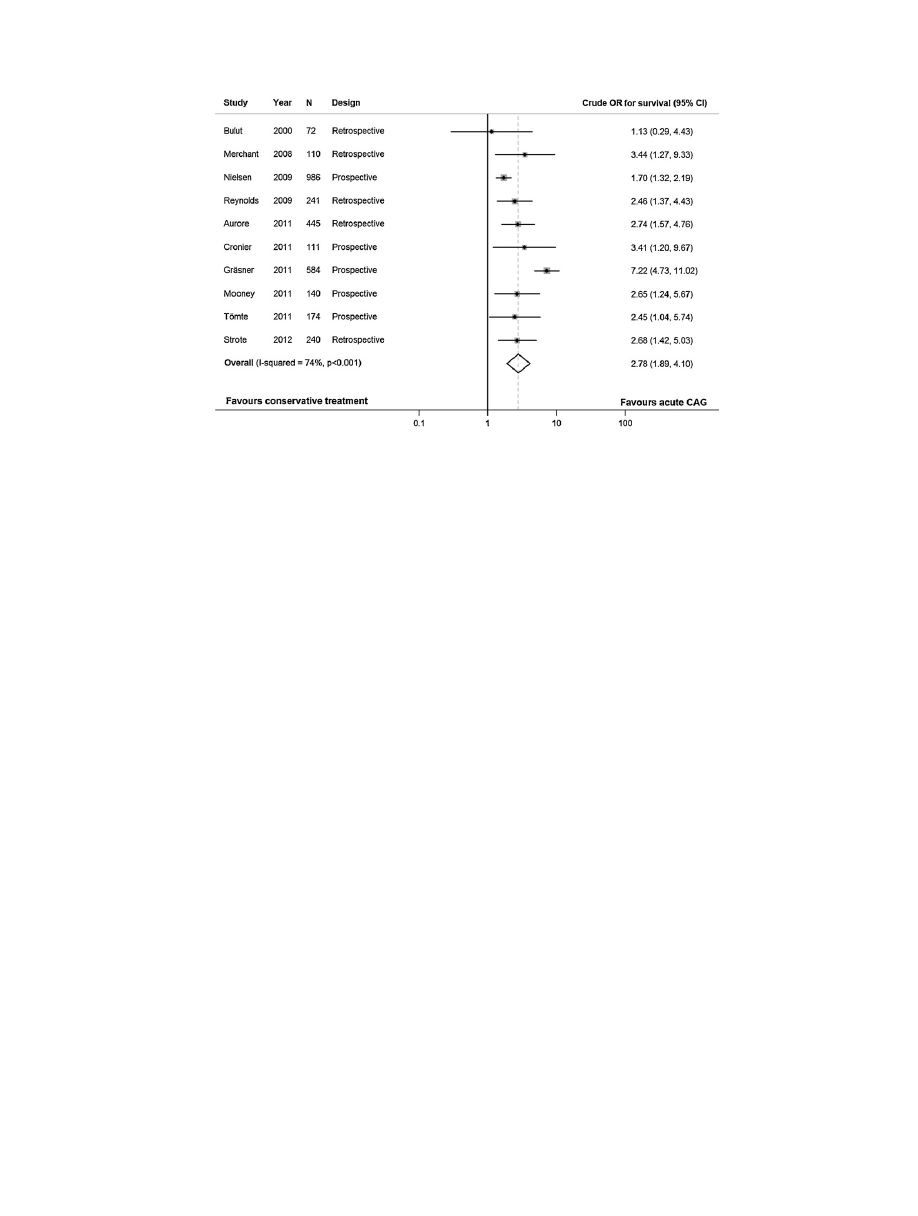

Fig.

2.

Forest

plot

from

a

meta-analysis

of

studies

including

patients

with

and

without

acute

coronary

angiography.

The

odds

ratios

are

unadjusted

for

possible

selection

bias

and

should

be

interpreted

with

caution.

The

grey

boxes

covering

the

point

estimate

of

the

odds

ratio

illustrate

the

weight

of

the

individual

study

in

the

pooled

odds

ratio.

These

weights

were

defined

by

a

random

effect

model

due

to

heterogeneity

of

the

studies

as

illustrated

by

a

high

I-squared.

N

=

number

of

patients;

OR

=

odds

ratio;

CI

=

confidence

interval;

CAG

=

coronary

angiography.

Two

small

studies

with

systematic

acute

CAG

following

OHCA

with

ventricular

fibrillation

were

not

included

in

to

more

selective

inclusion

criteria.

One

of

the

studies

included

15

patients

with

a

survival

to

hospital

discharge

of

73%.

other

study

included

50

comatose

haemodynamic

unstable

patients

and

demonstrated

an

impressive

six-month

survival

of

82%.

3.4.

Comparison

studies

including

patients

with

and

without

acute

coronary

angiography

10

studies

on

patients

resuscitated

from

car-

diac

arrest

of

mixed

aetiology

with

acute

CAG

only

performed

in

selected

indication

for

performing

acute

CAG

was

not

specified

in

most

of

the

studies.

The

use

of

acute

CAG

was

very

heterogeneous

in

the

studies

ranging

from

14%

to

83%.

Overall,

the

patients

undergoing

acute

CAG

had

a

better

survival.

The

character-

istics

of

patients

in

the

studies

were

heterogeneous,

e.g.

shockable

rhythms

ranged

from

39%

to

100%.

The

prevalence

of

comatose

sur-

vivors

was

only

sparsely

reported,

but

TH

was

generally

used

more

common

than

in

the

pure

STEMI-studies.

The

largest

study

prospectively

included

986

patients

resus-

citated

from

OHCA

at

38

centres

in

seven

countries

admitted

to

intensive

care

units

treated

with

percent

of

the

patients

presented

with

acute

myocardial

infarction,

but

only

49%

underwent

acute

CAG,

30%

PCI,

5%

thrombolytic

treatment

and

1%

coronary

artery

bypass

grafting.

Initial

shockable

rhythm

was

predictive

of

a

favourable

outcome

if

acute

CAG

was

performed

(p

<

0.001),

whereas

asystole

was

only

predictive

of

a

bad

outcome

if

acute

CAG

was

not

performed

(p

<

0.001).

Bleeding

requiring

trans-

fusion

was

more

common

in

patients

with

acute

CAG

(6.2%

vs

2.8%,

p

=

0.02).

In

three

other

studies,

acute

CAG

was

found

to

be

an

inde-

pendent

predictor

of

survival

with

adjusted

OR

of

3.8

(p

<

0.05),

5.7

(p

<

0.001)

and

11.2

(p

<

0.001),

study

only

demonstrated

a

significant

independent

predictive

value

on

sur-

vival

with

good

neurology

of

performing

CAG

before

discharge,

but

not

acute

CAG.

study

found

a

significant

independent

predictive

value

of

acute

PCI,

but

not

acute

CAG.

The

newest

and

only

LOE2

study

by

Strote

et

al.

included

240

resuscitated

OHCA

patients

and

compared

acute

CAG

(

≤6

h)

to

later

CAG

(>6

h)

or

no

CAG

before

was

performed

in

61%

with

acute

CAG,

which

more

often

had

ST-segment

elevation

and

pre-arrest

symptoms

indicating

ACS.

PCI

before

discharge

was

only

performed

in

7%

of

patients

without

acute

CAG.

The

crude

survival

to

hospital

discharge

was

better

in

patients

with

acute

CAG

(72%

vs

49%,

p

=

0.003).

To

address

possible

selection

bias,

matching

with

propensity

score

analysis

was

done

indicating

a

survival

benefit

of

acute

CAG

in

the

patients

with

propensity

scores

with

middle

to

high

likelihood

of

undergoing

acute

CAG.

No

multivariate

analysis

of

the

prognostic

effect

of

acute

CAG

including

the

propensity

score

was

reported

in

the

study.

The

crude

prognostic

information

from

the

ten

studies

was

com-

piled

in

a

meta-analysis

as

illustrated

in

the

forest

plot

in

studies,

except

the

smallest

and

oldest,

had

a

significant

unadjusted

OR

for

survival

favouring

acute

CAG.

The

pooled

unadjusted

OR

was

2.78,

95%

confidence

interval

(1.89;

4.10).

The

high

I-squared

illustrates

heterogeneity

in

the

studies.

4.

Discussion

The

high

rate

of

mortality

associated

with

OHCA

calls

for

opti-

mised

treatment

both

before

and

after

ROSC.

No

randomised

trials

exist

evaluating

the

use

of

acute

CAG

following

successful

resusci-

tation

from

OHCA

(

4.1.

Acute

coronary

angiography

in

ST-segment

elevation

myocardial

infarction

following

resuscitation

from

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

Acute

CAG

with

subsequent

PCI

compared

to

fibrinolysis

in

STEMI

patients

without

preceding

cardiac

arrest

is

favourable

for

survival

and

morbidity,

when

the

transfer

time

to

a

PCI

cen-

tre

is

short.

arrest

survivors

are

frequently

excluded

from

randomised

studies

because

of

unconsciousness

and

unsta-

ble

circulation

due

to

post-cardiac

arrest

syndrome

and

potential

irreversible

brain

optimal

management

of

espe-

cially

the

comatose

survivors

of

OHCA

with

a

proper

balance

between

action

and

withdrawal

of

treatment

is

very

challenging

both

for

the

interventional

cardiologist

and

the

intensivist.

The

1432

J.M.

Larsen,

J.

Ravkilde

/

Resuscitation

83 (2012) 1427–

1433

recommendation

in

the

2010

CoSTR

and

2010

European

guide-

lines

for

resuscitation

is

that

acute

CAG

should

be

considered

in

resuscitated

OHCA

patients

with

ST-segment

elevation

or

new

case

series

on

selected

resuscitated

patients

with

ST-segment

elevation

or

new

LBBB

demonstrate

acute

CAG

to

be

feasible

and

with

a

relatively

good

survival

(

The

studies

have

poor

evidence

levels

most

often

including

patients

with

wit-

nessed

arrests

and

shockable

rhythms.

This

selection

of

patients

probably

results

in

overoptimistic

survival

rates,

but

the

studies

do

demonstrate

that

acute

CAG

with

coronary

intervention

indeed

is

feasible

in

the

post

cardiac

arrest

setting.

A

small

retrospective

study

comparing

acute

fibrinolysis

and

acute

CAG

following

OHCA

demonstrated

no

significant

difference

in

survival,

but

actually

a

non-significant

trend

favouring

fibri-

nolysis

probably

due

to

time

delay

before

start

of

the

invasive

delay

can

also

explain

poorer

left

ventricu-

lar

ejection

fraction

in

patients

transfer

from

referral

hospital

compared

to

direct

admittance

to

a

PCI

centre

for

acute

CAG

fol-

lowing

emphasises

the

need

for

speed

in

treatment

of

patients

with

an

acute

coronary

occlusion.

If

transfer

to

a

PCI

centre

is

not

possible

in

a

reasonable

time,

an

alternative

reperfusion

strat-

egy

with

acute

fibrinolysis

should

still

be

considered

in

resuscitated

patients

with

STEMI

despite

preceding

chest

compressions.

4.2.

Acute

coronary

angiography

in

patients

following

resuscitation

from

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

The

2010

CoSTR

and

European

guidelines

on

resuscitation

rec-

ommend

acute

CAG

to

be

considered

in

selected

resuscitated

OHCA

patients

irrespective

of

ECG

findings,

if

coronary

ischaemia

is

suspected

to

be

the

aetiology

for

cardiac

arrest,

and

it

may

be

rea-

sonable

to

include

acute

CAG

as

part

of

a

standardised

post-cardiac

arrest

recommendation

is

based

on

observational

studies

with

poor

evidence

levels.

In

our

review,

we

identified

sev-

eral

mainly

newer

but

still

low

evidence

level

studies

on

patients

with

cardiac

arrest

of

mixed

aetiology

not

evaluated

in

the

2010

CoSTR,

adding

further

evidence

on

the

topic.

Systematic

acute

CAG

in

patient

without

an

obvious

non-cardiac

aetiology

has

demonstrated

a

high

prevalence

of

significant

CAD

and

a

favourable

survival

(

Studies

with

systematic

acute

CAG

in

patients

resuscitated

from

OHCA

with

shockable

rhythms

also

demonstrate

very

high

survival

studies

have

examined

the

diagnostic

properties

of

ST-segment

elevation

fol-

lowing

OHCA

compared

to

angiographic

findings

with

variable

results.

In

general,

the

diagnostic

values

were

suboptimal,

espe-

cially

the

negative

predictive

one

study,

the

negative

predictive

value

was

increased

to

100%

on

behalf

of

a

much

poorer

positive

predictive

value

by

using

an

extended

ECG

criterion

for

triage

with

ST-segment

elevation

and/or

depression

and/or

LBBB

and/or

unspecific

wide

QRS

and/or

right

bundle

branch

However,

the

author

is

cautious

to

recommend

implementation

of

this

strategy

for

triage

before

completion

of

prospective

studies,

as

it

is

well

known

that

the

ECG

can

be

without

ischaemic

findings

despite

an

acute

occlusion

in

patients

without

preceding

cardiac

arrest.

Our

meta-analysis

comparing

patients

with

and

without

acute

CAG

in

populations

with

mixed

aetiology

to

the

cardiac

arrest

demonstrated

a

significant

crude

positive

association

between

acute

CAG

and

survival.

Unfortunately,

no

data

is

available

for

an

adjusted

analysis

to

control

for

selection

bias

Therefore,

the

pooled

OR

in

the

meta-analysis

should

be

inter-

preted

with

caution.

The

risk

of

selection

bias

is

emphasised

by

the

only

LOE2

study

in

which

age,

bystander

cardiopulmonary

resus-

citation,

daytime

presentation,

history

of

PCI

or

stroke

and

acute

ST-segment

elevation

in

ECG

were

positively

associated

to

receiv-

ing

an

acute

CAG.

study

did

however

indicate

a

survival

benefit

of

acute

CAG

when

adjusting

for

selection

bias

by

propensity

score

analysis.

Six

other

studies

of

our

review

also

demonstrated

significant

adjusted

odds

ratios

in

favour

of

either

acute

CAG

or

acute

The

poor

diagnostic

properties

of

the

ECG

in

resuscitated

OHCA

patients

with

a

high

prevalence

of

CAD

emphasises

the

routine

use

of

systematic

acute

CAG

as

part

of

a

standard

post-cardiac-arrest

protocol.

The

use

of

routine

acute

CAG

in

conscious

survivors

is

not

very

controversial

as

most

interventional

cardiologists

will

con-

sider

this

as

high

risk

acute

coronary

syndrome.

Routine

acute

CAG

in

comatose

survivors

is

more

debatable

due

to

the

poor

evidence,

possible

irreversible

brain

injury

and

an

inherent

slightly

higher

risk

of

bleeding

complications

with

concurrent

TH.

the

studies

in

our

review

exclusively

including

comatose

survivors

mainly

treated

with

TH

and

acute

CAG

with

coronary

intervention

did

show

relatively

good

survival

recommend

future

randomised

studies

including

comatose

survivors

of

OHCA

without

STEMI

or

new

LBBB

undergoing

TH.

This

will

be

clinical

feasible

and

of

importance

both

for

the

intensive

care

and

inter-

ventional

cardiology

communities.

5.

Limitations

The

search

strategy

only

included

three

databases.

Non-English

articles

were

excluded.

Relevant

articles

could

be

missing

in

the

review,

but

this

is

less

likely

as

the

reference

lists

of

the

included

articles

and

the

2010

CoSTR

were

screened.

The

classification

of

the

studies

as

supporting,

neutral

and

opposing

PICO

is

debat-

able.

We

have

used

a

more

conservative

approach

than

in

the

2010

CoSTR

evaluation

process

by

only

allowing

studies

to

be

classified

as

supporting

if

adjusted

statistical

evidence

was

present

in

order

to

reduce

confounding.

The

definition

of

acute

CAG

differed

between

the

studies

from

less

than

6

h

up

to

less

than

24

h.

This

contributes

to

the

heterogeneity

of

the

reported

prognosis

in

the

studies.

It

would

have

been

clinically

relevant

to

make

a

separate

more

thorough

prognostic

analysis

of

conscious

and

comatose

survivors,

as

their

prognosis

differ.

This

was

not

feasible

with

the

available

data.

The

meta-analysis

was

based

on

prognostic

data

from

heterogeneous

studies.

This

was

evident

by

the

high

I-squared

value.

A

pooled

OR

seemed

fair

as

the

individual

odds

ratios

all

were

pointing

in

the

same

direction.

A

random

effect

model

was

used

due

to

the

hetero-

geneity.

The

meta-analysis

was

not

adjusted

for

possible

selection

bias

as

the

necessary

data

was

not

available.

Therefore,

the

meta-

analysis

should

be

interpreted

with

caution,

but

several

individual

studies

with

adjusted

analysis

do

support

the

use

of

acute

CAG

in

the

post

cardiac

arrest

setting.

6.

Conclusions

No

randomised

studies

exist

on

acute

CAG

following

OHCA.

An

increasing

number

of

observational

studies

support

feasibility

and

a

possible

survival

benefit

of

an

early

invasive

approach.

Acute

CAG

is

associated

to

a

better

survival

in

studies

on

resuscitated

patients

with

heterogeneous

aetiology

to

OHCA.

Systematic

acute

CAG

fol-

lowing

OHCA

without

an

obvious

non-cardiac

aetiology

should

be

strongly

considered

irrespective

of

electrocardiographic

findings

due

to

a

high

prevalence

of

CAD

and

unreliable

diagnostic

proper-

ties

of

the

electrocardiographic

findings.

Randomised

multicentre

studies

with

acute

CAG

following

OHCA

are

warranted

especially

in

comatose

survivors

for

optimising

the

diagnostic

and

therapeutic

strategy.

Conflict

of

interest

statement

None.

J.M.

Larsen,

J.

Ravkilde

/

Resuscitation

83 (2012) 1427–

1433

1433

Acknowledgements

The

authors

thank

chief

librarian

Conni

Skrubbeltrang

and

librarian

assistant

Jacob

Borg

Andersen

from

the

Medical

Library

at

Aalborg

University

Hospital

for

valuable

help

on

performing

the

database

search.

We

thank

research

secretary

Hanne

Madsen

from

the

Department

of

Cardiology

at

Aalborg

University

Hospital

for

assisting

in

the

final

preparation

of

the

manuscript.

Funding:

No

external

funding

was

used

in

the

preparation

of

the

manuscript.

References

1. Atwood

C,

Eisenberg

MS,

Herlitz

J,

Rea

TD.

Incidence

of

EMS-treated

out-of-

hospital

cardiac

arrest

in

Europe.

Resuscitation

2005;67:75–80.

2. Davies

MJ.

Anatomic

features

in

victims

of

sudden

coronary

death.

Coronary

artery

pathology.

Circulation

1992;85:19–24.

3.

Van

de

Werf

F,

Bax

J,

Betriu

A,

et

al.

Management

of

acute

myocardial

infarction

in

patients

presenting

with

persistent

ST-segment

elevation:

the

task

force

on

the

management

of

ST-segment

elevation

acute

myocardial

infarction

of

the

European

Society

of

Cardiology.

Eur

Heart

J

2008;29:2909–45.

4.

Bossaert

L,

O’Connor

RE,

Arntz

HR,

et

al.

Part

9:

acute

coronary

syndromes:

2010

International

Consensus

on

Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation

and

Emergency

Cardiovascular

Care

Science

with

Treatment

Recommendations.

Resuscitation

2010;81(Suppl.

1):175–212.

5.

Stroup

DF,

Berlin

JA,

Morton

SC,

et

al.

Meta-analysis

of

observational

studies

in

epidemiology:

a

proposal

for

reporting.

Meta-analysis

Of

Observational

Studies

in

Epidemiology

(MOOSE)

group.

JAMA

2000;283:2008–12.

6.

Moher

D,

Liberati

A,

Tetzlaff

J,

Altman

DG.

Preferred

reporting

items

for

sys-

tematic

reviews

and

meta-analyses:

the

PRISMA

statement.

J

Clin

Epidemiol

2009;62:1006–12.

7.

Morley

PT,

Atkins

DL,

Billi

JE,

et

al.

Part

3:

evidence

evaluation

process:

2010

International

Consensus

on

Cardiopulmonary

Resuscitation

and

Emergency

Cardiovascular

Care

Science

with

Treatment

Recommendations.

Resuscitation

2010;81(Suppl.

1):32–40.

8. Kahn

JK,

Glazier

S,

Swor

R,

Savas

V,

O’Neill

WW.

Primary

coronary

angioplasty

for

acute

myocardial

infarction

complicated

by

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

Am

J

Cardiol

1995;75:1069–70.

9.

McCullough

PA,

Prakash

R,

Tobin

KJ,

O’Neill

WW,

Thompson

RJ.

Application

of

a

cardiac

arrest

score

in

patients

with

sudden

death

and

ST

segment

elevation

for

triage

to

angiography

and

intervention.

J

Intervent

Cardiol

2002;15:257–61.

10.

Bendz

B,

Eritsland

J,

Nakstad

AR,

et

al.

Long-term

prognosis

after

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

and

primary

percutaneous

coronary

intervention.

Resuscitation

2004;63:49–53.

11. Quintero-Moran

B,

Moreno

R,

Villarreal

S,

et

al.

Percutaneous

coronary

inter-

vention

for

cardiac

arrest

secondary

to

ST-elevation

acute

myocardial

infarction.

Influence

of

immediate

paramedical/medical

assistance

on

clinical

outcome.

J

Invasive

Cardiol

2006;18:269–72.

12. Markusohn

E,

Roguin

A,

Sebbag

A,

et

al.

Primary

percutaneous

coronary

inter-

vention

after

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest:

patients

and

outcomes.

Isr

Med

Assoc

J

2007;9:257–9.

13. Garot

P,

Lefevre

T,

Eltchaninoff

H,

et

al.

Six-month

outcome

of

emer-

gency

percutaneous

coronary

intervention

in

resuscitated

patients

after

cardiac

arrest

complicating

ST-elevation

myocardial

infarction.

Circulation

2007;115:1354–62.

14.

Knafelj

R,

Radsel

P,

Ploj

T,

Noc

M.

Primary

percutaneous

coronary

intervention

and

mild

induced

hypothermia

in

comatose

survivors

of

ventricular

fibrillation

with

ST-elevation

acute

myocardial

infarction.

Resuscitation

2007;74:227–34.

15.

Richling

N,

Herkner

H,

Holzer

M,

Riedmueller

E,

Sterz

F,

Schreiber

W.

Thrombolytic

therapy

vs

primary

percutaneous

intervention

after

ventricular

fibrillation

cardiac

arrest

due

to

acute

ST-segment

elevation

myocardial

infarc-

tion

and

its

effect

on

F

outcome.

Am

J

Emerg

Med

2007;25:545–50.

16.

Pleskot

M,

Babu

A,

Hazukova

R,

et

al.

Out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrests

in

patients

with

acute

ST

elevation

myocardial

infarctions

in

the

East

Bohemian

region

over

the

period

2002–2004.

Cardiology

2008;109:41–51.

17.

Peels

HO,

Jessurun

GA,

van

der

Horst

IC,

Arnold

AE,

Piers

LH,

Zijlstra

F.

Outcome

in

transferred

and

nontransferred

patients

after

primary

percutaneous

coronary

intervention

for

ischaemic

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

Catheter

Cardiovasc

Interv

2008;71:147–51.

18.

Mager

A,

Kornowski

R,

Murninkas

D,

et

al.

Outcome

of

emergency

percutaneous

coronary

intervention

for

acute

ST-elevation

myocardial

infarction

complicated

by

cardiac

arrest.

Coron

Artery

Dis

2008;19:615–8.

19.

Wolfrum

S,

Pierau

C,

Radke

PW,

Schunkert

H,

Kurowski

V.

Mild

therapeutic

hypothermia

in

patients

after

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

due

to

acute

ST-

segment

elevation

myocardial

infarction

undergoing

immediate

percutaneous

coronary

intervention.

Crit

Care

Med

2008;36:1780–6.

20.

Lettieri

C,

Savonitto

S,

De

Servi

S,

et

al.

Emergency

percutaneous

coronary

inter-

vention

in

patients

with

ST-elevation

myocardial

infarction

complicated

by

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest:

early

and

medium-term

outcome.

Am

Heart

J

2009;157:569–75.

21.

Szymanski

FM,

Grabowski

M,

Karpinski

G,

Hrynkiewicz

A,

Filipiak

KJ,

Opolski

G.

Does

time

delay

between

the

primary

cardiac

arrest

and

PCI

affect

outcome?

Acta

Cardiol

2009;64:633–7.

22. Hosmane

VR,

Mustafa

NG,

Reddy

VK,

et

al.

Survival

and

neurologic

recovery

in

patients

with

ST-segment

elevation

myocardial

infarction

resuscitated

from

cardiac

arrest.

J

Am

Coll

Cardiol

2009;53:409–15.

23.

Spaulding

CM,

Joly

L,

Rosenberg

A,

et

al.

Immediate

coronary

angiography

in

survivors

of

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

N

Engl

J

Med

1997;336:1629–33.

24.

Anyfantakis

ZA,

Baron

G,

Aubry

P,

et

al.

Acute

coronary

angiographic

findings

in

survivors

of

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

Am

Heart

J

2009;157:312–8.

25.

Dumas

F,

Cariou

A,

Manzo-Silberman

S,

et

al.

Immediate

percutaneous

coro-

nary

intervention

is

associated

with

better

survival

after

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest:

insights

from

the

PROCAT

(Parisian

Region

Out

of

Hospital

Cardiac

Arrest)

registry.

Circ

Cardiovasc

Interv

2010;3:200–7.

26.

Sideris

G,

Voicu

S,

Dillinger

JG,

et

al.

Value

of

post-resuscitation

electrocardio-

gram

in

the

diagnosis

of

acute

myocardial

infarction

in

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

patients.

Resuscitation

2011;82:1148–53.

27.

Mollmann

H,

Szardien

S,

Liebetrau

C,

et

al.

Clinical

outcome

of

patients

treated

with

an

early

invasive

strategy

after

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

J

Int

Med

Res

2011;39:2169–77.

28.

Keelan

PC,

Bunch

TJ,

White

RD,

Packer

DL,

Holmes

DR.

Early

direct

coro-

nary

angioplasty

in

survivors

of

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

Am

J

Cardiol

2003;91:1461–3.

29. Hovdenes

J,

Laake

JH,

Aaberge

L,

Haugaa

H,

Bugge

JF.

Therapeutic

hypother-

mia

after

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest:

experiences

with

patients

treated

with

percutaneous

coronary

intervention

and

cardiogenic

shock.

Acta

Anaesthesiol

Scand

2007;51:137–42.

30. Bulut

S,

Aengevaeren

WRM,

Luijten

HJE,

Verheugt

FWA.

Successful

out-

of-hospital

cardiopulmonary

resuscitation:

What

is

the

optimal

in-hospital

treatment

strategy?

Resuscitation

2000;47:155–61.

31.

Merchant

RM,

Abella

BS,

Khan

M,

et

al.

Cardiac

catheterization

is

underutilized

after

in-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

Resuscitation

2008;79:398–403.

32.

Nielsen

N,

Hovdenes

J,

Nilsson

F,

et

al.

Outcome,

timing

and

adverse

events

in

therapeutic

hypothermia

after

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest.

Acta

Anaesthesiol

Scand

2009;53:926–34.

33. Reynolds

JC,

Callaway

CW,

El

Khoudary

SR,

Moore

CG,

Alvarez

RJ,

Rittenberger

JC.

Coronary

angiography

predicts

improved

outcome

following

cardiac

arrest:

propensity-adjusted

analysis.

J

Intensive

Care

Med

2009;24:179–86.

34.

Aurore

A,

Jabre

P,

Liot

P,

Margenet

A,

Lecarpentier

E,

Combes

X.

Predictive

factors

for

positive

coronary

angiography

in

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

patients.

Eur

J

Emerg

Med

2011;18:73–6.

35.

Cronier

P,

Vignon

P,

Bouferrache

K,

et

al.

Impact

of

routine

percutaneous

coronary

intervention

after

out-of-hospital

cardiac

arrest

due

to

ventricular

fibrillation.

Crit

Care

2011;15:R122.

36. Grasner

JT,

Meybohm

P,

Caliebe

A,

et

al.

Postresuscitation

care

with

mild

therapeutic

hypothermia

and

coronary

intervention

after

out-of-hospital

cardiopulmonary

resuscitation:

a

prospective

registry

analysis.

Crit

Care

2011;15:R61.

37.

Mooney

MR,

Unger

BT,

Boland

LL,

et

al.

Therapeutic

hypothermia

after

out-of-

hospital

cardiac

arrest:

evaluation

of

a

regional

system

to

increase

access

to

cooling.

Circulation

2011;124:206–14.

38.

Tomte

O,

Andersen

GO,

Jacobsen

D,

Draegni

T,

Auestad

B,

Sunde

K.

Strong

and

weak

aspects

of

an

established

post-resuscitation

treatment

protocol—a

five-

year

observational

study.

Resuscitation