Promenade into the gap: Tokyo’s impossible void

Pedro Hormigo

1

*, Takao Morita

2

and Jean-Se´bastien Cluzel

1

1

Faculty of Engineering and Design, Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto, Japan

2

Faculty of Engineering and Design, Kyoto Institute of Technology, Kyoto, Japan

This paper discusses the importance of gaps in urban space and cityscape. It proposes that gaps are

particularly important in high-density urban areas, testifying of the options for urban densification and

presents the case study of Tokyo’s J.R. Yamanote railway and Shibuya district to support this idea. In the

case of the J.R. Yamanote line – a railway with a concentric layout serving Tokyo’s central districts – we see

how gaps initially created under elevated sections of this structure gradually disappeared and became

occupied by new urban tissues, allowing urban growth to continue taking place in the city centre. In

Shibuya, where no more land was available, gaps were used to support a strategy of space usage

intensification. While physically transportation and commercial infrastructures appeared absorbing all gaps

between them, some amusement facilities such as a cable-car or a planetarium were the devices created to

expand the visual horizon beyond the increasingly dense urban space. These findings reveal that in such

processes, gaps have appeared, disappeared and in some cases reappeared to promote continuous urban

intensification processes essential to the preservation of urban centrality.

URBAN DESIGN International (2007) 12, 3–19. doi:10.1057/palgrave.udi.9000181

Keywords:

intensification; gap; emptiness; density; Tokyo; Japan

Introduction

How can we translate urban densification? How

do spaces reserved for displacement, spaces

where one stays or spaces serving both functions

articulate and juxtapose? Are the relations be-

tween these spaces supported by principles of

continuity or rupture? In other words, which are

the concepts that the urban planner, acting on the

transformation of the city, should apply when

confronted with issues as diverse as the concep-

tion of new spaces, the forecast of their effect and

relations with existing spaces or even issues

related with the preservation of urban heritage?

This study, centred on an in situ urban observa-

tion and on the historic evolution of some of

Tokyo’s districts, tries to answer these questions.

Here the issue is to find the words that would

allow us to express certain rules inherent to urban

development. Our analysis can be inscribed

within the continuity of research that has as a

goal the definition of spatial articulations, that

is, ‘the competence to build’ (Choay, 1992). We

have chosen as a reference term the word gap in

order to show that the separation between two

spaces is an essential rule to any spatial develop-

ment, in the same way as the term threshold

(Bonnin, 2000) has contributed for an under-

standing of spatial articulations in dwelling space.

This term gap will also allow us to stress an

evolutional tendency followed by some fast-

growth Japanese cities in their conquest for

space; a tendency that we could synthesize as

‘from the infinitely big to the infinitely small’.

Finally, the term gap will also allow us to answer

certain questions regarding conservation in the

contemporary transformation of the Japanese

cityscape.

Gap

The word gap means open or empty space, a

hiatus, an interruption in the continuity between

things, a separation, interval or breach. In its

*Corresponding

author.

Kyoto-shi

Sakyo-ku,

Tanaka

Monzen-cho 8-1, Hyakumanben, Haitsu 301, 606-8225, Japan.

Tel: þ 81-90-9610-3522, E-mail: phormigo@yahoo.com

URBAN DESIGN

International (2007) 12, 3–19

r 2007 Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. 1357-5317/07 $30.00

www.palgrave-journals.co.uk/udi

primary sense, it is used to express the existence

of a physical separation between two elements.

When associated with another word, the term gap

can also be utilized to characterize subjective

types of separations, for example, the case of

human communication problems. In fact, the

expression generation gap testifies to a lack of

exchange, a psychological and/or temporal

distance causing a rupture in communication

due to a mutual incomprehension. This distance,

which can be physical, temporal or psychological

is regarded as a source of rupture; however,

it mostly interests us in that it is often perceived

in a negative way whereas it could instead

have, as a consequence, a positive result: that

distance actually allows the preservation of a

certain peace.

The study of these gaps can be particularly

interesting in the case of high-density urban

tissues, since in their sense of separation or

distance – such as they exist in human relations

– they become essential to all cohabitation of

urban space. They thus become important

options for urban intensification or densification.

Firstly, we will consider the evolution of the gaps

between the various buildings that compose the

Shibuya station in Tokyo. Secondly, we will focus

on gaps that were necessary to isolate high-speed

circulation roads from the urban tissue. For this

purpose, we have chosen the example of the

Yamanote line in Tokyo and the evolution of the

land plots under its elevated sections. We will see

that in Tokyo this type of land has been rapidly

utilized.

Finally, even if gaps are essential elements to

urban intensification and densification, we will

also attempt to demonstrate that in the Japanese

city they have a particular value. With this in

mind, we will return to the Shibuya district to

propose a hypothesis that the disappearance of

the two previously mentioned types of gap might

bring about their replacement by new ones, but in

a different form.

Empty spaces or gaps?

The City in History (Mumford, 1961) describes the

constantly growing need for space in cities as

characteristic of their development. In this work

of reference that deals essentially with urban

issues, Mumford shows in a duty-bound fashion

that the spatial expansion of cities followed two

main principles:

1

the occupation of a sprawling

urban territory and the multiplication of levels,

that is, a development in strata or layers. Today,

the observation of urban agglomerations reveals

that these two principles of expansion still

prevail, applied in different proportions accord-

ing to the type of urban area.

Mumford also stressed the correlation between

building density, territorial expansion and the

development of rapid transportation systems. His

work, more than showing that the conquest of

new territories went together with the densifica-

tion of urban centres, explains that both develop-

ment

principles

were

accompanied

by

a

transformation of the transportation networks at

a quantitative and qualitative level; a transforma-

tion that was ultimately brought about by the

development of new speeds of displacement.

The urban tissues dislocate as the opening of

roads for rapid circulation attempts to respond to

traffic congestion problems in the metropolis.

Mumford will give to this historical and global

reality the name ‘urban devastation’. With the

same tone, he criticizes certain new urban devel-

opment projects; road interchanges are called

‘space eaters’ – a term or argument that was

utilized by a great number of other critics.

On the race to urban decongestion of the past two

centuries, the great novelties were connected with

the development of circulation networks. The

more the metropolises were transformed into

megalopolises, the more those new developments

became detached from the original urban tissue,

that primary layer, in elevated or underground

secondary layers. Those secondary layers appear

with the construction of viaducts, depressed

roads or tunnels: a multitude of means allowing

the isolation of the different speeds of displace-

ment.

2

Today, all the megalopolises are equipped

1

In fact, Mumford insists mostly on the first principle.

2

In the layout of this infrastructure, the different speed levels

had, as a corollary, the creation of spatial gaps between the

different types of circulation roads. Thus, the roads brought

about new forms of space occupation and articulation. It

becomes clear that in the conception of these multilayer urban

spaces, the absence of analytical models or methodologies is

caused by the unavailability of any forecast for serious space

management, a fact that Mumford severely criticized, but a

task to which professors such as Bill Hillier (Hillier and

Hanson, 1984; Hillier and Furuyama, 2003) devote themselves

today.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

4

URBAN DESIGN International

with this type of network in secondary layers,

where the demand is for rapid circulation speeds.

It would thus seem that in this transformation

process – also characterized in La vitesse de

liberation (Virilio, 1995) – the layout of roads in

secondary elevated layers would lead to the

appearance of derelict or empty spaces on the

primary layer: ‘waste spaces’ (Lynch and South-

worth, 1990). Would then these new infrastruc-

tures also be worthy of the name Mumford

attributed to them: ‘space eaters’? It is only once

we give them a function that they finally lose that

image and start being considered true spaces.

However negative these denominations might

sound, we must nevertheless ask if they are

simply spaces to suppress from cities. When

Mumford looks into the future, he recognizes

wasted urban space potential, so finally do not

these ‘wasted spaces’ become transformed by

‘space eaters’ into something else? Should not

these spaces be studied to examine what funda-

mental interactions they carry out inside cities?

In urban development processes, the study of

interactions between layers or spaces could help

us understand the effect that the addition of these

elements can produce. We will try to show how

the secondary layers impact upon their immedi-

ate environment, or to put it more simply, what

are the impacts of a viaduct over a city’s primary

layer? Most of all, we will try to clarify what sort

of gaps this infrastructure induces, in which way

these gaps are preserved, how they disappear and

then reappear.

For this study, we have chosen Tokyo’s central

district – an area that counts among the world’s

highest for densities of occupation. Tokyo’s

complex road network – superimposing multiple

levels of road, railway and pedestrian passage-

way – achieves a paroxysm. This is a crucial

aspect of our study, considering that the relations

between spaces for circulation and other types of

spaces pose important questions regarding densi-

fication (Jacobs, 1961; Glaeser, 2000).

3

The gaps addressed by Mumford, upon which

Choay (1969) casts a theory, were those of the

Western cities. In The Hidden Dimension Hall

(1966) confronts some particularities of Japanese

space culture with those of the West. Two decades

later, The Hidden Order (Ashihara, 1989) attempted

to explain the logic and certain rules in Tokyo’s

urban tissue. The choice of the Japanese capital

might unveil some differences between its gaps

and those found in the West.

Promenade through some of Tokyo’s

gaps

In the following pages, we will walk through

several districts in Tokyo. From the start, we

proposed re-reading the main stages of urban

development in the great amusement district that

corresponds to Shibuya and its station area. We

will see how many gaps have been absorbed by

the construction of increasingly larger, taller and

therefore, denser building masses. As we exit the

Shibuya station, we will begin a promenade

through Tokyo, along the Yamanote railway

(Tokyo’s loop line). This line’s concentric layout

will allow us to identify the different qualities of

spaces below its viaduct sections and also to

perform a primary classification of the gaps

existing in those areas. Finally, we will walk back

to Shibuya and see that this district’s ‘places of

memory’, which are the secretion of history, are

themselves gaps. Finally, in a moment of pause

we will find ourselves facing the impossible void.

The ‘space eaters’:

4

the Shibuya station and the

department store.

Today, Shibuya is one of Tokyo’s main commercial

districts. In the first place, this centrality is

geographical, but Shibuya has been for a long

time the meeting point of roads and railways,

which rendered it suitable for a commercial

development that further accentuated its centrality.

In this district, we are particularly interested in

two aspects: its high density and its amusement,

information and commercial activities. Here,

where territorial expansion is no longer possible,

Shibuya has no option other than increasing its

3

Density-increase as a constructive approach to urban

problems particularly in the American city, is referred by Jane

Jacobs in The Death and Life of Great American Cities particularly

in the section ‘The need for concentration’.

4

We borrow again this expression from Mumford in its sense

of space consumption.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

5

URBAN DESIGN International

density. Within this context, the Shibuya district

as it stands today is a testament to developments

in infrastructure that serve the purpose of

optimizing the possibilities for spatial efficiency

and urban development.

Historically, even if Shibuya only became a

district of Tokyo in the beginning of the 20th

century, it was already an important crossing

point between the downtown Edo

5

and its

periphery. However, Shibuya was not merely an

important thoroughfare but also the place where

many agricultural goods were produced and

where their distribution was organized. Thus,

the Shibuya of the Edo period

6

was a dynamic

and developing area (Shibuya, 1952).

At that time, the high areas of Aoyama and

Setagaya were the base of samurai and other

residences for the nobility. Today, those areas are

the base for important companies and their

commercial activities.

The road network dating back from the Edo

period would greatly contribute for the develop-

ment and expansion of Shibuya. As previously

mentioned, Shibuya’s important role as thorough-

fare originated in the Koˆshuˆ Road,

7

one of the

country’s five main roads. Originally created with

a military purpose, this road was in reality used

mostly for the transportation of goods and people

between the Setagaya hill and the centre of Edo

(Akai, 1976). Another important road crossing

Shibuya was the O

ˆ yama

8

road. In the Edo period,

the presence of these important roads attracted an

increasing population and more commercial

activities, not only in this district’s low and

central areas but also in other nearby areas such

as Yoyogi and Shinmachi.

In 1885, the opening of Shibuya station

9

acceler-

ated the development of activities in this district.

Meanwhile, that station assumes a primordial role

as part of an increasingly complex machine: the

train allowed the development of new commer-

cial activities that were themselves highly depen-

dent on the increase of user frequency. If in the

beginning of the 20th century, small factories and

workshops started concentrating in the central

area by the Shibuya river, they would later on

change location or disappear, as the number of

people frequenting this area was accompanied by

a larger number of services – Shibuya became the

centre of commercial activities (Hagawa, 2000).

The development of Shibuya’s urban tissue was,

as in the whole of Tokyo, completed in phases

following, for example, successive crises, fires or

rapid industrialization. In 1923, the great Kantoˆ

earthquake was a particularly devastating event

that was followed by an important period of

reconstruction.

The Second World War destroyed large portions of

Tokyo including part of the Shibuya district

(Ishikawa, 1992). Soon the whole city would be

the target of reconstruction and many areas would

be renovated. While the new buildings replaced

the old or destroyed ones, a great effort was put

into the city’s transportation infrastructures. In the

case of Shibuya, these infrastructures associated

with large-scale department-store-type commercial

facilities. The owners of these commercial giants

were in most cases the owners of the transporta-

tion companies.

10

After the implantation of these

first commercial facilities, a department store

boom would take place in Japan in the years

following the war. The pre-war department stores

and commercial facilities become bigger, more

complex and started offering, in the same space,

cultural and amusement activities. The accessibil-

ity to a multitude of services in a concentrated area

becomes the unrivalled image of Shibuya. The

developments in railway transportation assured, in

this area, support to the growing number of

commercial activities. In that sense, these struc-

tures naturally pushed for the concentration of

activities close to the stations and consequently to

an increase of the building volumes. At Shibuya,

for services and commerce, the station area was

‘the place to be’.

5

Old denomination for Tokyo until 1868, when it became the

capital of Japan.

6

Edo period: 1603–1868. Period corresponding to the

Tokugawa shogun’s rule.

7

Koˆshuˆ Kaidoˆ, road connecting Edo to Shimosuwa, located

in today’s Nagano prefecture.

8

O

ˆ yama Kaidoˆ, road connecting Edo to today’s Kanagawa

prefecture.

9

The first railway in this area belongs to the present J.R.

Yamanote line.

10

In Japan, other than the initially state-owned national

railway company, there are several other private companies

(Cf Aoki, 2002).

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

6

URBAN DESIGN International

For a long time, railway companies in Japan have

invested in domains other than mere transporta-

tion.

11

Undoubtedly, they soon realized that their

stations were strategic commercial locations and

that a financial investment in this commercial

segment could represent a substantial increase in

their revenue. Thus today in Japan, railway

companies are the owners of the majority of the

department stores and real-estate developments

adjoining the stations

12

(Tiry, 1997; Aveline, 2003).

In this sense, these companies play an important

role in Tokyo’s urbanization and in the creation of

a contemporary cityscape.

In Shibuya, the Toˆkyuˆ company had a prominent

role in the transformation of space and cityscape.

In 1934, this railway company opened its first

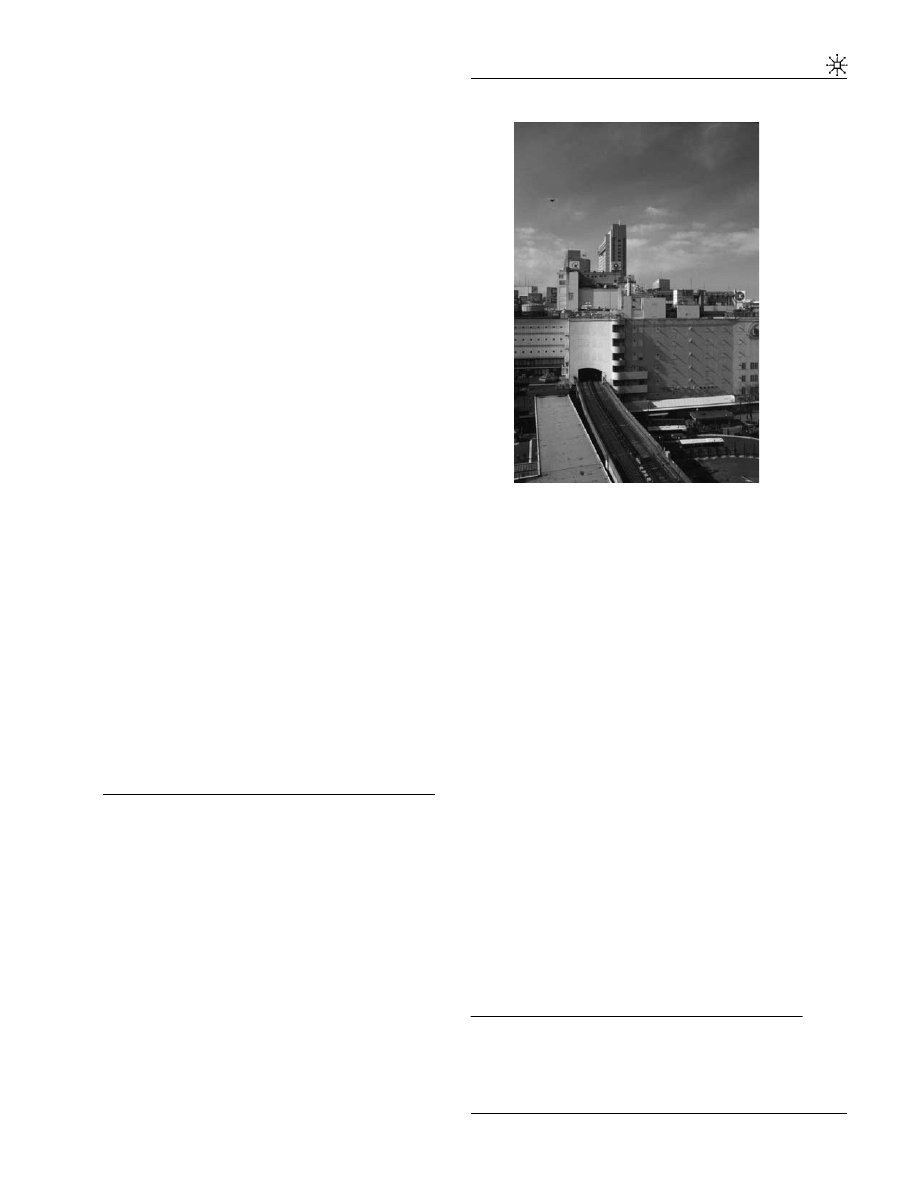

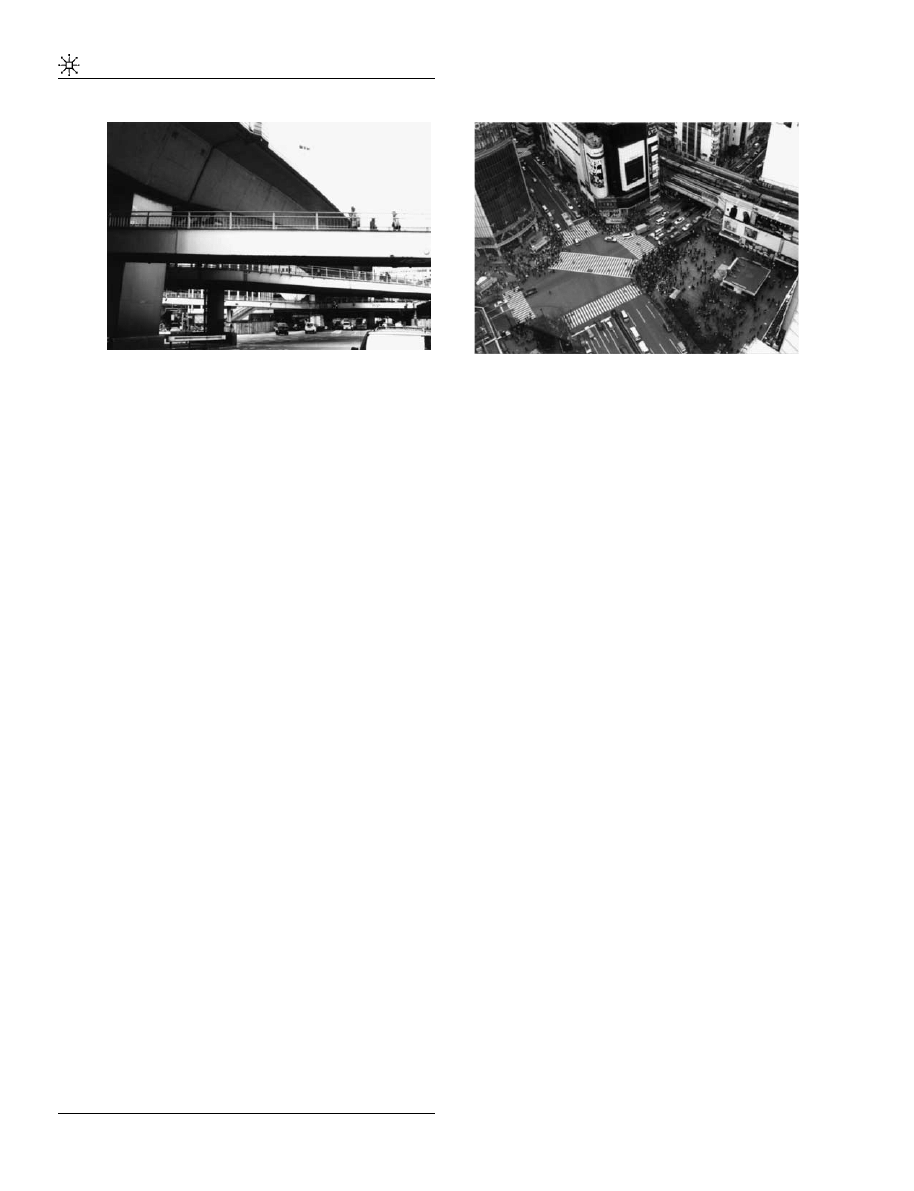

department store (Figure 1) adjoining the Shibuya

station.

13

From that initial building, the Toˆkyuˆ

company would gradually extend its commercial

activity and facilities. Other railway companies

established in Shibuya and all over Japan would

privilege the same successful model of growth,

building their own commercial facilities in the

areas adjoining their stations (Miyata and Haya-

shi, 1985). In 1954 Toˆkyuˆ opened its new building

that extends over the Ginza line station, which

itself opened in 1938 (1, 12 No. 1). We can suggest

that the new building ‘swallowed’ the Ginza line

station in the process.

In the same way, through the 1960s important

urban modifications connected with the organiza-

tion of the 1964 Olympic games had a deep

impact over Tokyo’s cityscape in general and

particularly at Shibuya. An elevated highway

14

passing through the centre of Shibuya just beside

the south side of the station was a new infra-

structure addition to the already existing train

and subway lines.

15

This infrastructure, in the

shape of new viaducts, responded to saturation

problems at the primary layer. They demon-

strated that once the development at the ground

level became impossible, a growth potential

remained available in layers to be created above.

This conquest of secondary layers, which allowed

for an important increase in the flux of people and

goods, was accompanied by the Toˆkyuˆ company’s

devouring appetite for space around its stations.

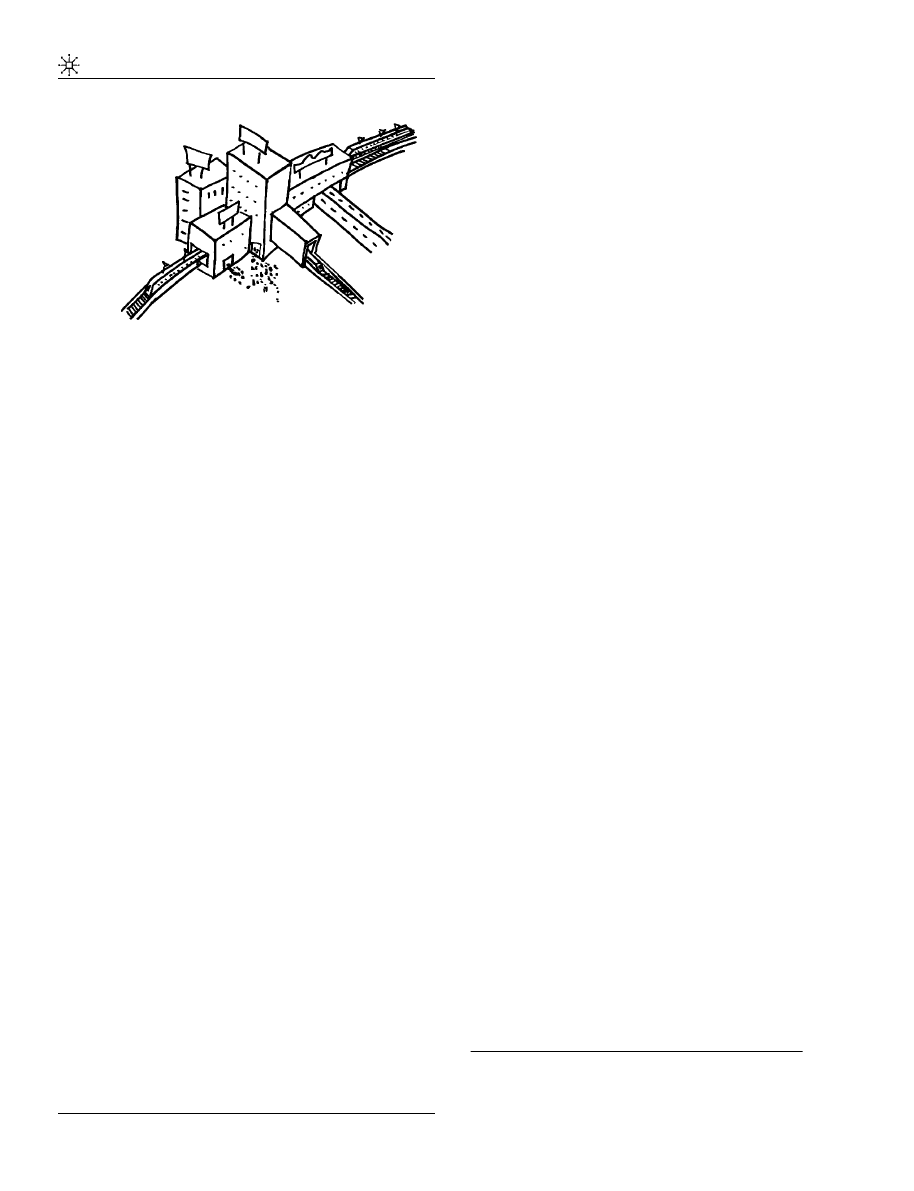

Concentration would be intensified by a densifi-

cation: the ‘space eaters’ (Figure 2) sat at the table,

there they would remain.

Recently, a 25-storey hotel and shopping centre

complex was added immediately west of Toˆkyuˆ’s

two buildings and over the Inokashira (Keioˆ) line.

These two last extensions, the Mark City and the

Figure 1. The Shibuya station and the department

store. View of the Ginza subway line entering the

Shibuya station, above which stands Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko

Department Store complex.

11

The diversity of activities undertaken by the same

company seems to be the result of a tradition in Japan. O

ˆ ta

shows that already in the Japanese medieval period, carpenter

guilds controlled the wood production network, a part of the

necessary infrastructures for its transportation and even entire

villages between the production territories and the places

where the wood was utilized (larger cities). For this aspect, see

in particular, the chapter 9 ‘Zojishi and mokuryoˆ’, chapter 16

‘Za, architecture guilds’ and chapter 25 ‘Master -builders in the

modern age’ in O

ˆ ta’s capital work in the history of Japanese

architecture: O

ˆ ta Hirotaroˆ, Nihon kenchiku-shi josetsu, Introduc-

tion to the history of Japanese architecture, Shoˆkokusha, Toˆkyoˆ,

first edition 1946, last edition 1989.

12

Please refer to the work of Natacha Aveline on real-estate

policy and the great railway companies in Japan. Also refer to

the research undertaken by Corinne Tiry on the real-estate

concentration developments around Japan’s largest train

stations.

13

The location of this store corresponds to today’s Toˆkyuˆ

Toˆyoko Department Store East Building.

14

Metropolitan Expressway No.3 (ME3).

15

Today, there are six train and subway lines operating in

Shibuya: the Yamanote line (J.R.), Saikyoˆ (J.R.), Toˆyoko

(Toˆkyuˆ), Inokashira (Keioˆ), Ginza and Hanzomon (subway).

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

7

URBAN DESIGN International

Excel Hotel Toˆkyuˆ tower were inaugurated in

2000.

Facilities such as the Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko Department

Store are punctual real-estate developments along

the train lines. The study of the evolution in this

kind of district and its buildings brings us some

clues to the relations between people and space in

Tokyo.

If we compare the Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko Department

Store’s West Building as it was in the 1950s and

now, we can see important changes. In the 1950s,

the buildings were connected by various bridges.

Such transition spaces appeared outside the

buildings, in open spaces: interstitial spaces. At

that time, there were gaps between the buildings

built in 1934 and 1954.

Today, for the users of Shibuya station, the

changes between trains from different companies

take place inside the buildings, without passages

through an outside space. However, the new

pedestrian circuits inside this giant station pre-

serve inside this territory a large number of gaps.

The transition between different trains from

different companies still requires a ticket change,

the passage through ticket control barriers, some

minutes walk and often the shift between many

levels – aspects that represent an immense variety

of gaps. These buildings would eventually be-

come themselves passageways, connecting all

sorts of functions. Even if they seem to form

now a ‘continuous space’, this continuity is but a

mere illusion since the gaps they envelop are

merely disguised. For the pedestrian, only the

climatic gap has disappeared: the need to ‘exit’, to

pass from the ‘inside’ to the ‘outside’ has ceased

to exist.

If we compare the past and present pictures of the

Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko Department Store and station

complex, we can see another important transfor-

mation in the gap between the inside and the

outside. For instance, in the past, the fac¸ades of

this store’s East and West buildings were origin-

ally designed with generously large windows. By

contrast, presently these fac¸ades became blind,

their windows were sealed and their volumes

closed in, often enveloped by large size bill-

boards; changes that impede any sort of visual

communication between the inside and outside.

This phenomenon corresponds to a final stage of

space consumption: the relation with the outside

is no longer fundamental. Architecture became

hermetic. Here the gap between inside and

outside is more clearly stated than ever before.

Today, the Shibuya station is a large-scale real-

estate complex composed of several buildings

connected by tunnels and pedestrian passage-

ways. The railways intersect in different elevated

or underground levels. Station platforms are

connected by escalators, passageways and tunnels

– interior streets in a true sense. Some station

platforms extend all the way south until they are

overlaid by the Metropolitan Expressway No. 3

(ME3). The surrounding streets are also equipped

with a series of infrastructures that overlay each

other. All these paths are marked by the presence

of devices providing all sorts of information that

help people understand the relationships between

the most diverse places and functions. The

information, which is superimposed onto the

urban functions, ends up further increasing the

intensificaction in the usage of space.

The transformation of lost spaces: 150 m apart

from the nodes of a concentric line

When describing nodes,

16

Lynch (1960) empha-

sized that they tend to form at the junctions of

significant roads. Rail transportation infrastruc-

tures that belong to secondary layers also have

important effects not only on the nodes they serve

but also on other less immediate areas.

Figure 2. The ‘space eaters’. Representation of the

Shibuya station and its department store.

16

Nodes such as railway stations or other places where

people come together.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

8

URBAN DESIGN International

Choay

17

suggested similarities between the effects

of a medieval town’s walls and those of a Parisian

elevated railway. Such similarities seem appro-

priate for this discussion. In today’s cities, barrier

effects caused by viaducts are particularly felt and

seen at the street level. Whether they constitute a

physical or visual barrier, elevated roads often

accentuate communication problems in the urban

tissue between its two sides, projecting over the

primary layer functionless empty spaces that

fragment the city.

The usages and functions attributable to these

residual spaces were subjects of discussion in a

period of reflection that followed great infrastruc-

ture development projects in many Western cities

(Halprin, 1966). Nevertheless the question of how

to use these empty spaces was always approached

in a critical way, denouncing the waste of space.

Indeed, until recently the discussions were mostly

focused on the shape of the infrastructures

themselves (Appleyard et al, 1964). Today, one

can criticize the designers of such structures for

not having considered sufficiently their interac-

tion with the city. This brief reminder on the

discussion topics concerning this subject shows

the way this infrastructure was conceived, or

better said, the way they were not, because the

problem of managing the interactions between

these structures and the city was not satisfactorily

addressed.

It is thus from these empty spaces – which are

somehow unexpected because they seem to

contradict the intensification process itself – that

we will try to see if the reason why they are empty

is not exactly because they are merely expectant

spaces, waiting to interact with the city.

To deem how a city can integrate residual spaces

created by viaducts, it seems necessary to identify

some of these empty spaces. The centre of Tokyo

is again the choice to perform this research; since

in this environment, it would seem that residual

spaces have in many cases found functions that

rehabilitate them to a status worthy of the title space.

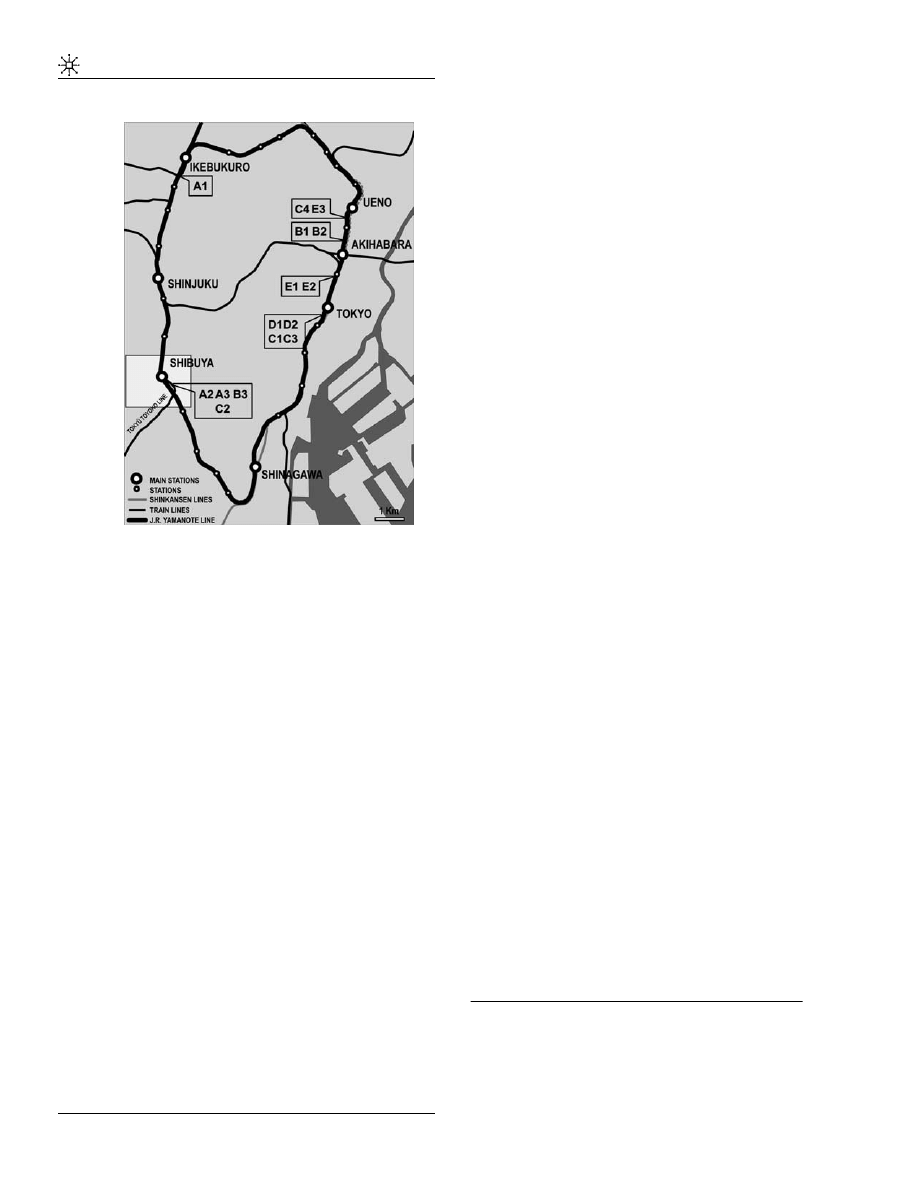

The geography of the promenade

In this Tokyoite promenade (Figures 3 and 4), we

have tried to identify the barrier and permeability

effects induced by the concentric J.R. Yamanote

line.

18

We have also extended our research to

crossing areas between this line and other rail-

ways and highways.

The Yamanote line will illustrate how the residual

spaces induced by the creation of an elevated line

were absorbed and what sort of interaction they

preserve today with the primary layer of the city.

To avoid any confusion with the nodes, the sites

chosen for analysis are located systematically

more than 150m apart from the stations.

This research took place from February 2001 to

December 2002. The data gathered and analysed

are based on notes, drawings, photographs and

maps. The promenade begins at the Shibuya station

and proceeds clock-wise towards the Shinjuku

station. As we have just mentioned, this walk does

not merely take into account the Yamanote line but

also junction and intersection areas with the

following lines: J.R. Sobu line at the Akihabara

station; Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko line at the Shibuya station;

J.R. Keihin Toˆhoku line close to Akihabara

station; J.R. Toˆkaidoˆ (Shinkansen) line at the Tokyo

station; J.R. Toˆhoku Joˆetsu (Shinkansen) line

between the Kanda and Yuraku-choˆ stations.

The selected railway sections rest over elevated

structures, sometimes decades old. It seems that

in many of those sections such a period of time

sufficed for these residual spaces to spin specific

urban relations with their surrounding areas.

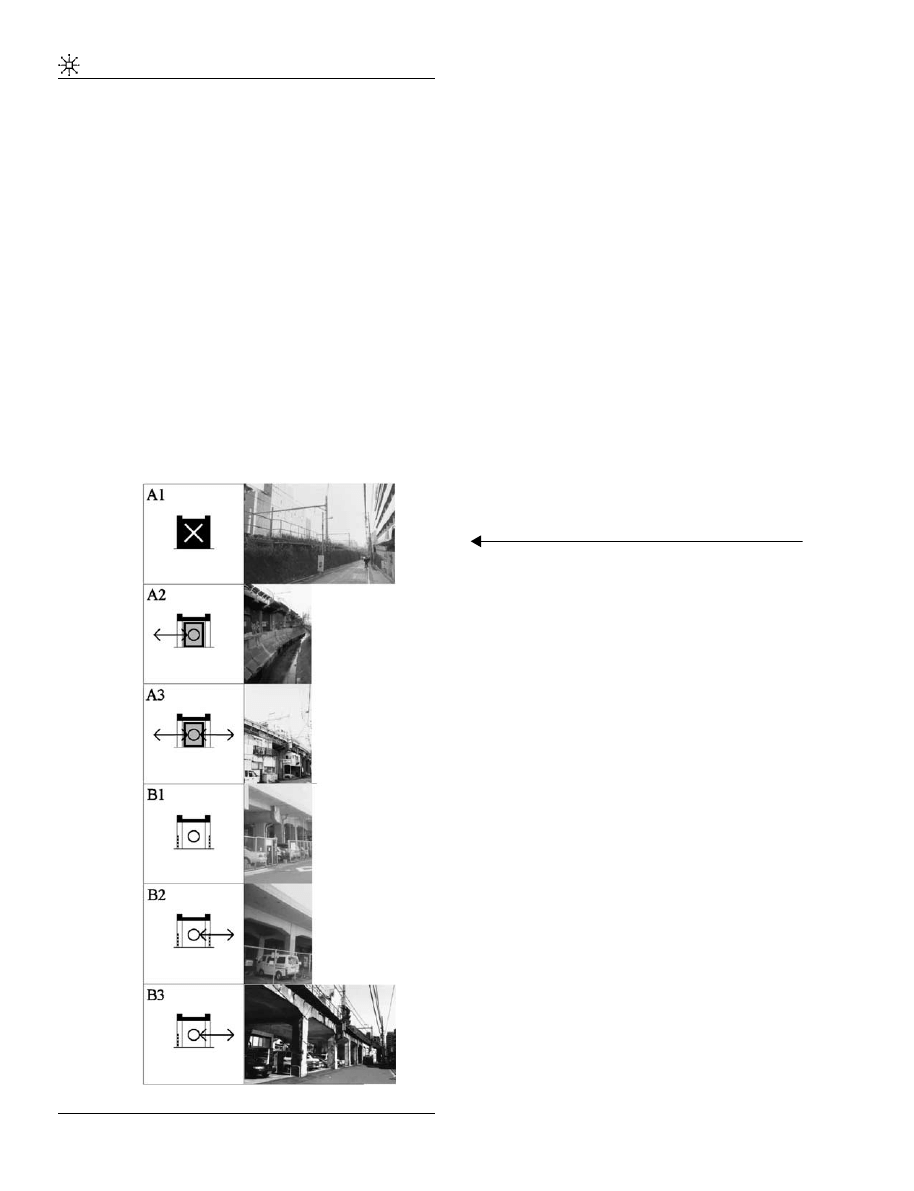

Each site is presented by the shape of a schematic

cross section (Figures 3-1, 3-2 and 3-3), allowing

the identification of the conditions between both

sides of the viaduct and thus – according to the

types of physical occupation, dimension and

function of these spaces – the level of urban

permeability under the viaducts.

From section A2 to B3 (see Figure 3-1), the spaces

below the viaduct are occupied by single units.

The land plots are sometimes fenced; however,

despite offering no physical permeability, they do

allow visual permeability. They are either acces-

sible from one or two sides. In some cases, visual

permeability is obstructed once a space is occupied

by a building. All sorts of activities take place:

offices, small shops or mere storage of goods

17

Choay (1969, op.cit).

18

This line will hereafter be referred to as Yamanote line.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

9

URBAN DESIGN International

inside buildings, while car parking or construction

material storage occurs on any open space.

From section C1 to C4 (Figure 3-2), the spaces

below the viaduct are also thoroughfares. For this

reason, they become strategic places for commer-

cial activities, attracting people and therefore

participating in the creation of a dynamic urban

life.

From section D1 to E3, the viaducts’ width allows

more complex occupation schemes such as gal-

leries. The viaduct assumes the role of axis in a

new urban development, initially liberating a

strip of land – limited in terms of occupation in

height – that later on attracts new commercial

activities allowing the revitalization of some areas

inside the city.

These diagrams clearly show that the viaducts

that initially have produced empty spaces, end by

supplying spaces to which it is possible to

attribute different functions. Accordingly, to those

functional variations – represented in the sche-

matic sections – they correspond to changes in

terms of interaction and permeability with the

existing urban tissue.

The Yamanote line shows us that in this case,

what appear to be residual spaces barely resist

occupation. For instance, immediately after the

completion of the Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko line’s elevated

sections, small industries and workshops started

occupying the spaces below the viaduct close to

the Shibuya station. A similar situation exists

under the Yamanote line. The occupation of these

land strips has never ceased to increase to this

day. Presently, the type of activities has shifted

mostly to backstage services such as express mail

companies, warehouses, garages and parking

lots or front stage services like clothes shops,

Figure 3. Types of urban interaction below the viaducts

of the J.R. Yamanote (loop) line. Circle marks corre-

spond to accessible spaces whereas cross marks

correspond to inaccessible ones. [Figure 3-1] A1 to

B3: simple units. The rampart: A1: Between the Mejiro

and Ikebukuro stations. This site is representative of a

rampart effect. No passage is possible between the two

sides of the railway, all views are obstructed by the

rampart. The viaduct: an empty space? A2 to E3

Sections A2 to E3 present different types of physical

and visual permeability. Here the height of the viaduct

allows the passage of pedestrians, cars or the construc-

tion of buildings. A2: The Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko line, approxi-

mately 150 m south of Shibuya station. The entrance

into the space below the viaduct is made from only the

entrance of the building that occupies it. A3: The Toˆkyuˆ

Toˆyoko line, approximately 250 m south of Shibuya

station. Entrance possible by both sides. Again the

building occupies the space obstructing the view to the

other side of the viaduct. B1: The Toˆhoku Joˆetsu

(Shinkansen) line, running parallel to the Yamanote

line, approximately 300 m north of the Akihabara station.

Limited physical permeability with only an entrance point

from one of the viaduct’s sides (door). The wired fence,

despite limiting physical permeability, assures visual

permeability. B2: The Toˆhoku Joˆetsu (Shinkansen) line,

running along the Yamanote line, approximately 250 m

north of the Akihabara. No entrance points, visual

permeability again assured by a wired fence. B3: The

Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko line, approximately 150 m south of

Shibuya station. Open access to the space, despite no

physical permeability to the opposite side of the viaduct.

Once more a wired fence assures visual permeability.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

10

URBAN DESIGN International

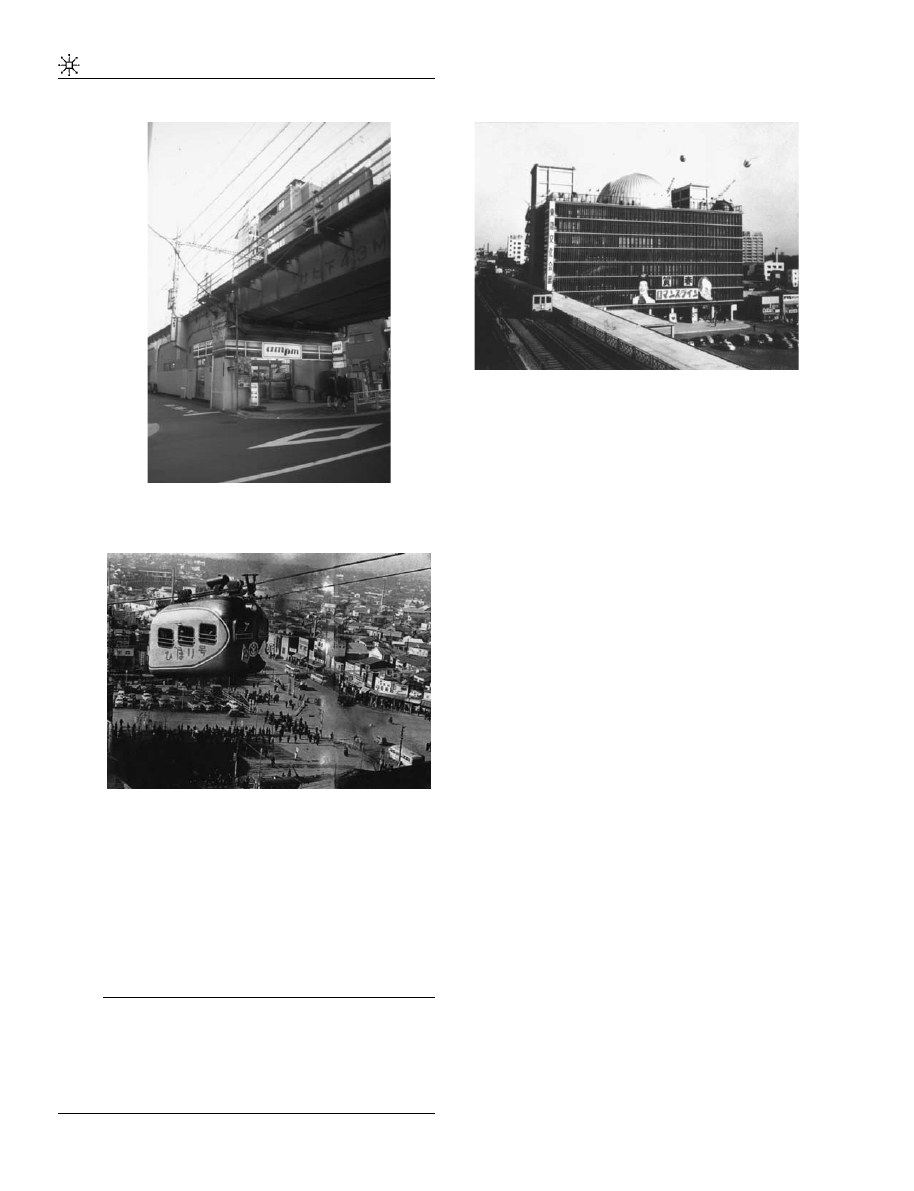

convenience stores (Figures 5 and 6 No. 2) or even

bars that now occupy some of these spaces.

In Tokyo, if a viaduct’s width allows it, new urban

formations can take place. Even if some of these

spaces continue resisting intensification of activ-

ity, their occupation is foreseeable in the near

future. This disappearance will naturally be

accompanied by a decrease in visual permeability

– similar to the effect of a town’s wall – but not

forcefully by a decrease in physical permeability

as we have seen.

The case of Tokyo revealed that these ‘empty

spaces’, born from problems of cohabitation

between different types of circulation, have a

great potential for development. In addition,

Figure 3-2. Continued C1 to C4. Thoroughfares and

their

additional

functions:

simple

units.

C1:

The

Yamanote line running along the Toˆkaidoˆ (Shinkansen)

line, approximately 100 m south of Tokyo station.

Thoroughfare for cars and pedestrians, visual perme-

ability. C2: The Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko line approximately 400 m

south of Shibuya station. Thoroughfare for cars and

pedestrians, visual permeability, a shop is installed

below the viaduct. C3: The Yamanote line running along

the Toˆkaidoˆ (Shinkansen) line, approximately 50 m

south of Yurakuchoˆ station. Pedestrian thoroughfare.

Initially, the thoroughfare offered visual and circulation

permeability. Meanwhile, a construction appeared occu-

pying half of the open space and that permeability was

reduced. C4: The Yamanote line running along the

Keihin Toˆhoku line, approximately 150 m south of Ueno

station. Identical to that of C1, however in this case, the

thoroughfare is limited to pedestrian circulation.

Figure 3-3. Continued D1 to E3. The development of a

new urban tissue: multiple units. D1 and D2: The

Toˆkaidoˆ (Shinkansen) line, running along the Yamanote

line, approximately 500 m south of the Tokyo station. A

pedestrian street runs below the viaduct. Buildings with

2–3 storeys high are aligned along that street. There is

no visual permeability between the two sides of the

viaduct. Buildings can be accessed from both under and

outside of the viaduct (D1) or merely from under it (D2).

E1 and E2: The Yamanote line running along the

Toˆkaidoˆ, the Joˆetsu and the Keihin Toˆhoku lines,

between the Akihabara and Tokyo stations. E3: The

Yamanote line running along the Keihin Toˆhoku line,

approximately 100 m south of Ueno station. E1, E2 and

E3: A street crosses the viaduct, allowing visual

permeability between its two sides. Interior service

streets along the viaduct allow the passage of pedes-

trians and cars.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

11

URBAN DESIGN International

if in Tokyo the spaces under viaducts were

deemed differently from those in the West, this

is also due to a specific real-estate policy under-

taken by the railway companies, who by all

possible means – for instance by renting these

spaces

19

– attempt to maximize the profitability of

these assets.

The ‘places of memory’ of Shibuya

Some years ago, Nora (1997) reminded us that the

places of memory were the secretion of history.

Today, memoirs and descriptions by travellers

who came to Shibuya remind the historians,

which were the places and attractions that

marked the development of this commercial and

amusement district. Two such places seem to

clearly show the particularities of Shibuya’s

development throughout the second-half of the

20th century: the cable-car and the planetarium.

Until now, we have seen that the intensification of

space occupation by buildings has restricted

visual permeability– as in the case of the devel-

opments under the elevated railways – however,

with the gradual development of a hermetic

architecture, another gap gained importance: that

of the separation between the inside and outside.

It seemed to us that here the places of memory –

the cable-car and the planetarium – and the gaps

they bring into play, might reveal the devices

utilized as attempts to escape a saturated physical

space (Tuan, 1998).

The streets of Shibuya are today a succession of

ramparts, railways, highways and pedestrian pas-

sageways. At the same time, an advertising

strategy that encourages the commercial develop-

ment of this district contributes to the affirmation of

Shibuya’s identity as an urban centre. It was only

recently that electronic screens showing commer-

cials the size of entire fac¸ades began invading the

city; however, their impact was immediate in that

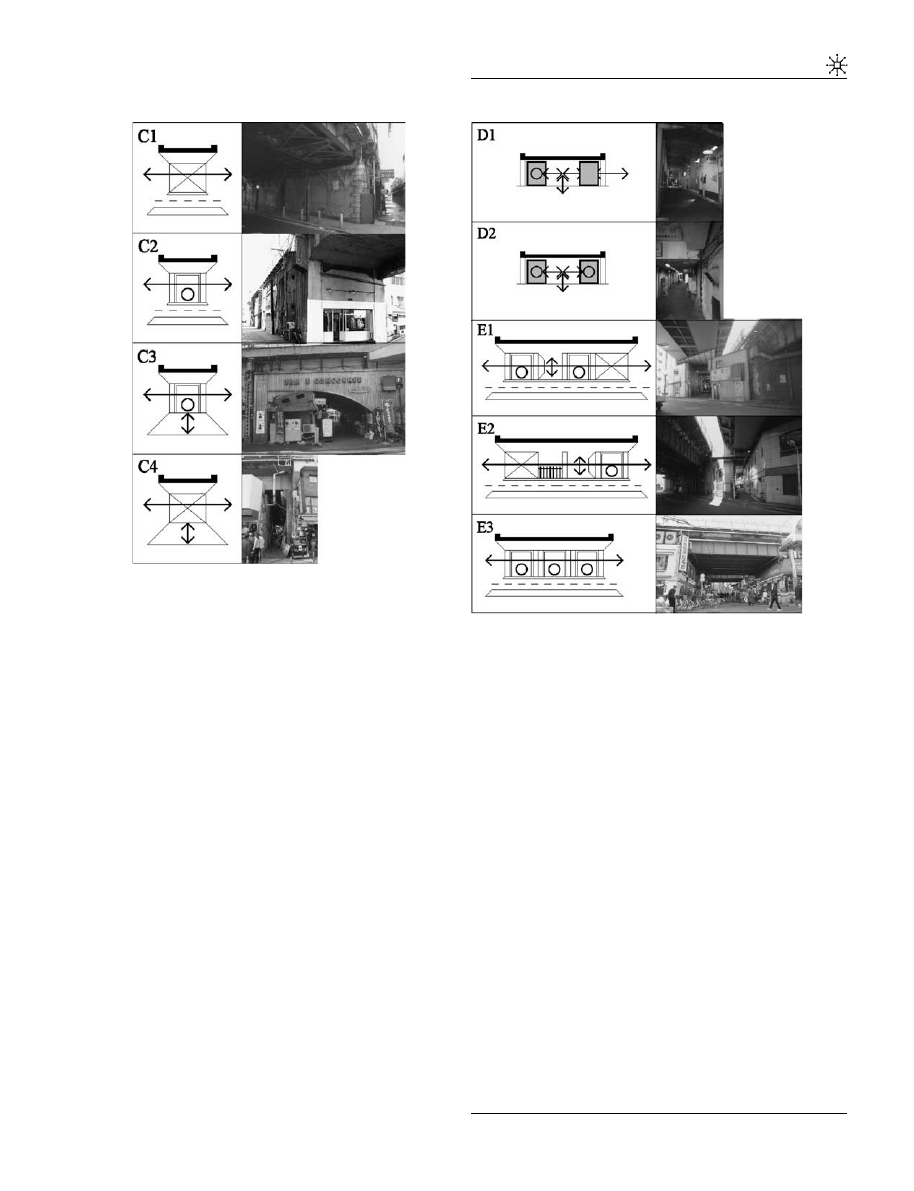

Figure 5. The cable-car, 1952.

Figure 6. The planetarium. The Toˆkyuˆ Bunka Kaikan

building, 1956.

Figure 4. Convenience store, Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko line, 2002.

19

On real-estate policies by railway companies in Japan,

particularly for the case of the ‘koˆka’ (elevated railways) see

Aveline op. cit. ‘La location immobilie`re’, p. 99. On the topic of

spaces under elevated highways whose design has been target

of more participation from local communities, refer Yamamoto,

(1995).

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

12

URBAN DESIGN International

they changed the way people visually perceive

Shibuya’s contemporary cityscape.

In the following examples, we will find that the

increase in building volumes was accompanied

by the appearance of new gaps utilized to escape

the restrictions on the visual range. This type of

action/reaction had been suggested by Paul

Virilio (1984).

The cable-car

In the first years that followed the Second World

War, the centre of Shibuya, also affected by

the air raids was in fast recovery. Surrounding

the Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko Department Store and the

station, which had been spared by these attacks,

the crowds seethed in (black) markets that

popped out close to many of the railway stations

(Figure 7 and 12 No. 3).

In 1950, in the midst of a city in reconstruction,

the Toˆkyuˆ Toˆyoko Department Store inaugurated

a new attraction: a cable-car connecting this

department store’s terrace

20

to the Tamaden

Building.

21

The cable-car nicknamed Hibari-go

performed a round trip covering a distance of

approximately 350m (Figure 7).

The accessory quality of this means of locomotion

is clear and pertinent in this discussion: neither

distance nor time spent to reach it were signifi-

cantly gained by comparison with the speed and

time taken by a pedestrian on the street for the

same distance. The investment involved in its

construction testifies the importance that these

attractions had for the increase of visitors in these

shopping centres. During a short period of three

years, after which this cable-car attraction was

closed, only a generation of young travellers – this

attraction was limited to children use – could

have a foretaste of what Shibuya’s future citys-

capes would look like. This facility was one of the

first where one could experience an aerial

perspective. Also it should be of interest to note

that it was the creation of a gap that was chosen to

attract the crowds. This separation in height

spatially corresponds to a physical gap: the

distance from the cabin to the ground. This in

turn allowed for a visual gap: the offer of an

‘extraordinary’ view that allowed the spectator to

escape from his/her ‘ordinary’ everyday view of

the city.

At that time, the density and volume of construc-

tion was increasingly connected with Shibuya’s

image. It is quite easy to imagine that Shibuya was

therefore one of the districts where visual escapes

became more difficult to find. It is in this con-

text that the Toˆkyuˆ company, undoubtedly aware

that this issue could provoke a general feeling

of claustrophobia on its customers, attempted to

avoid that possibility through the opening of a new

horizon offered from the cable-car. Shibuya was

the place of all contrasts: from a densification taken

to a paroxysm, one could come in search of a

panoramic view of all Tokyo.

The planetarium

In Shibuya, the race for devices that allowed the

reinvention of gaps between people and the

world had therefore been set in motion. In 1953,

a new attraction was inaugurated in the new

Toˆkyuˆ Department Store’s building

22

(Figure 8

and 12 No. 4): the Gotoˆ Planetarium. This

attraction followed the directions of the cable-car

Figure 7. Electronic screen at the Q-front building,

Shibuya station’s North exit, 2002.

20

Today referred to as the Toˆkyuˆ Department Store East

Building.

21

Today’s Toˆkyuˆ Department Store West Building.

22

The ‘Toˆkyuˆ Bunka Kaikan’ (Toˆkyuˆ Culture Hall) building.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

13

URBAN DESIGN International

device, whose purpose was to offer a panoramic

view of the city.

The cable-car invited its young passengers to move

from a dense physical space – the streets and the

interior space of buildings – to the contemplation

of an immense extension. With the Planetarium,

however, the travellers departed from everyday

spaces to experience the infinitely big.

From a limited real space, to the limitlessness of a

virtual one, this time the trip was available to all.

Elsewhere, as in Japan, the planetarium probably

marks an age when we try to draw away the

physical limits of our territories. If we compare

the planetarium with the cable-car, it is note-

worthy that while the physical gaps did not cease

to decrease, the gaps between the real and the

virtual were continuously multiplied. The trips

proposed in the planetarium were free from the

physical variables on which the cable-car de-

pended – all movement was abolished and the

spectator was still.

Once again, by the use of contrast against a

density that had reached a paroxysm, this new

dimension contributed for the establishment of

Shibuya’s future image: only here such a new

range of universes could be available. From

inside Shibuya we could now have access to

views of an outer space.

The success of these two initial attractions would

definitely contribute to turn Shibuya into the

breeding ground for new devices devoted to

territorial production – territories whose limits

went beyond mere physical constraints.

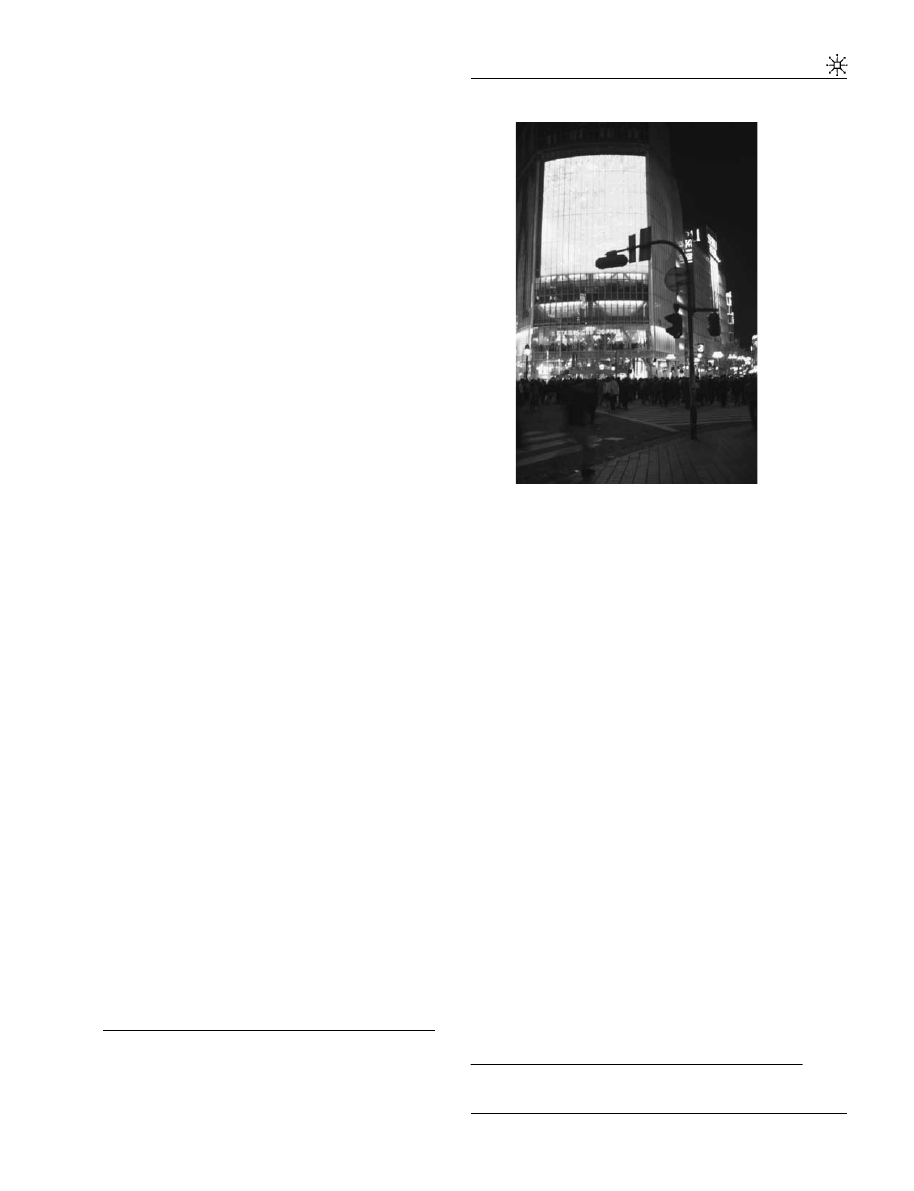

The electronic screens

Previously, we have seen that the department

stores were responsible for the absorption of the

gaps surrounding the stations. To compensate for

that physical space absorption and visual ob-

struction, they were also responsible for the

creation of visual escapes such as the cable-car

and the planetarium. We have underlined that the

fac¸ades of more recent buildings at the Toˆkyuˆ

Toˆyoko Department Store had become blind and

later wrapped in billboards.

Today, these billboards have come to be replaced

in many cases by electronic screens. A building

such as the Q-front (Figures 9 and 6 No. 5),

located at the North exit of the Shibuya station is

equipped with one such screen as its main fac¸ade.

The images on the screen, at a maximum speed of

30 per second, offer new horizons beyond those

cluttered by the physical elements that compose

the city – horizons that would otherwise remain

inaccessible.

In a similar way to that of the planetarium, these

screens are the best devices existing today for the

creation of spaces unavailable in the city. The use

of these devices is probably connected with the

continuously growing density of construction. As

a consequence and in an ironic way, these screens,

the devices of today, do not show so much the

infinitely big spaces but mostly consumable

Figure 8. Pedestrian passageways. Shibuya station’s

South crossing, 2002.

Figure 9. The Shibuya crossing. Shibuya station’s

North exit, 2002.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

14

URBAN DESIGN International

goods, or small products. The screens send us

back to the saturated inner space of the depart-

ment stores, to the purchasable item. For this

reason, the trips into the unknown proposed by

the first amusement devices, those of the new

landscapes, are preserved, incarnated in the

novelty of the products displayed on the screen.

It should be noted that in this passage from the

infinitely big to the infinitely small, the conquest

of physical space persists. In fact the streets of

today have replaced spaces like the planetarium’s

projection room, which ultimately were not more

than mere lost spaces.

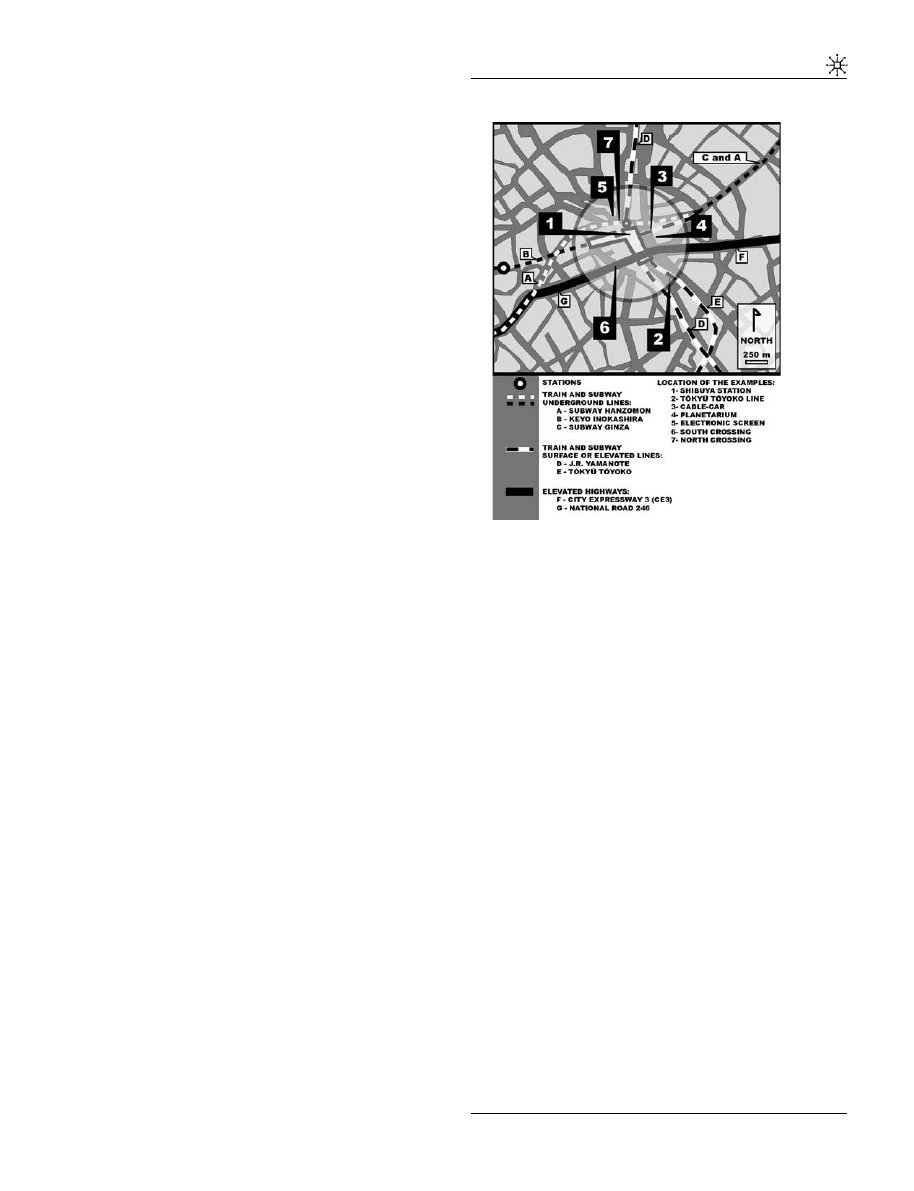

The impossible void or the Shibuya crossing

The excess of pedestrian and car circulation at a

crossing point is at the origin of saturation

problems; problems such as those we find at

Shibuya. The solutions for these issues aim at an

improved circulation fluidity in that same space,

through the reduction of obstacles to that flux.

At the Shibuya station’s South crossing, the

Tamagawa road, elevated pedestrian passage-

ways and the ME3 (Figures 10 and 6 No. 6)

expressway superposed each other, representing

the complexity of these circulation problems. At

this location, all the different types of circulation

have their own network installed over distinct

layers that stress a certain number of physical,

temporal and mental gaps.

Nevertheless, the creation of layers where circula-

tion flows uninterruptedly did not suffice to

liberate the primary layer, the ground level, from

the mandatory stops and interruptions demanded

by a single-layer urban tissue, a layer where

pedestrians and cars meet each other.

We will now try to analyse one such crossing – the

Shibuya station’s North crossing – concentrating

our analysis on one its aspects, its emptiness.

At first it might be difficult to imagine an empty

space at a crossing area such as this one, a place

which is constantly being used by both pedes-

trians and cars. Nevertheless, the fact is that

everyday, for a period of approximately one-and–

a-half hours this space is emptyy unoccupied.

This crossing is a gap trapped between two types

of circulation that can only take place by taking

turns, intermittently. Both car and pedestrian

circulation utilize this place, but demand distinct

spaces. For this reason there is not one but two

crossings. Their coexistence is regulated by a

device, the traffic light, which allows the alterna-

tion and intermittence between circulations and

means of locomotion. Thus, one after the other the

crossings appear and disappear temporally. But

for one of these crossings to give place to the

following one, space must be emptied of its

occupants. A period of 10 seconds is determined

to evacuate with all urgency the pedestrians and

cars in delay, for whom their crossing is about to

be replaced (Figure 11 and 12 No. 7).

For a very short time interval, while none of the

crossings are functional, a new space is created:

an empty space necessary to the cohabitation of

the two crossings: a gapspace.

The analysis of functions in relation with time

allows us to deduce that the Shibuya crossing is

Figure 10. Gap formation model and types of spatial

expansion.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

15

URBAN DESIGN International

not one but a sum of three spaces: pedestrian

crossing, car crossing and empty space. This

empty space is perhaps a no man’s land, a space

that allows the other two to exist. This decom-

position seems to show us again that a gap – here

a temporary void – is mandatory in urban

intensification processes, for it allows two func-

tionally and formally distinct spaces to coexist in

the same place.

But does this temporarily empty space remain

empty? Could any empty space in Shibuya resist

intensification? At this crossing in particular, a

space with a high user frequency, numerous

screens invade the fac¸ades. Here, the sidewalks

have become spaces identical to those of movie

theatres; information spaces that perhaps resem-

ble the planetarium room.

This information appearing on the screens, when

overlaid onto the urban functions, ends by

increasing the intensity of space usage. The

proportions of such electronic screens are in

direct relation with those of the crossing’s empty

space; that is, they intend to fill the void left

between them and the pedestrian who waits for

his/her turn to fill the Shibuya crossing. Thus

they suggest the impossibility of even the most

tenuous of voids intermittently trapped between

two spaces.

Depaule (Depaule and Bonnin dir., 2002)

23

re-

cently insisted on the impossibility of the void in

the dwelling space portrayed in literary fictions.

In Bachelard’s (1958) words,

24

‘For to great drea-

mers of corners and holes nothing is ever empty,

the dialectics of full and empty only correspond to

two geometrical non-realities. The function of

inhabiting constitutes the link between full and

empty’. At this crossing of paths we have just

come from catching a void and describing it, a

void rich in sense, nevertheless a void erased by

the density of information. So, even if we have

made this void appear by the differentiation and

division of a space in time intervals, how can we

now continue designating this place as void, if we

have managed to identify it, inhabit it with words,

if we have attributed to it the values that

characterize its usage?

Below the screens is indicated the time in New

York, Beijing, London and Paris. The projected

images range from the infinitesimal to the infinite.

Which place without a fixed dimension or date is

this? When Borges (1952) reminds us that ‘For a

man, for Giordano Bruno, the rupture of the vaults

of the sky was a liberation’, he underlines that the

enthusiasm with which Bruno wrote The Ash

Wednesday supper

25

would not survive: ‘[y] sixty

years later, not a mere reflection of that fervour

remained; men felt lost in time and space. In time,

because if the future and the past are infinite, any

date is illusory; in space because any being is at an

equal distance from infinite and infinitesimal, thus

there is no more place. Nothing is at a day, at a

certain place, no one knows its face’.

26

Conclusion

Conservation of empty spaces: Japan and the West

If the case of Tokyo refutes the idea that the spaces

below viaducts are doomed to remain ‘lost’ or

‘empty’ spaces, the largest gaps that modern

people could impose over their cities, then perhaps

their survival is the proof of an unconscious or

unconfessed desire for their conservation.

Figure 11. Map of Tokyo, Yamanote line.

23

pp. 233–243.

24

pp. 140.

25

Giordano Bruno, original tittle La cena de le ceneri, 1584.

26

Borges, op.cit., id. pp. 17–18.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

16

URBAN DESIGN International

Today, the discussions on these residual spaces,

beyond the mere issue of their positive or

negative effects, seem to add up to one sole fact:

the importance of these spaces is the indicator of a

problematic in a time in a society: gaps.

In the West, the once critical attitude towards

these spaces has begun a process of retraction.

Now, we admit more easily that there is an

interest in their preservation. In recent debates on

urban space, particularly, when it comes to the

topic of urban ecology, gaps are more than ever at

the centre of discussion. Many attribute to them a

growing importance, for instance, the status of

spaces to be preserved, particularly in areas

where urbanization assumed a ‘totalitarian’ as-

pect, that is, where all spaces seem to have

developed a function.

What can we reply to those who go as far as to

propose the preservation of empty areas for their

historical value as no man’s lands (Koolhaas and

Mau, 1995)? If some authors attach to them the

value of cultural heritage, it is because the urban

voids are considered a testimony to a stage of

urban development that grants them a value as

memorial spaces (Cluzel and Nishida, 2007). In

this case, we may ask ourselves if these interstitial

spaces are not monuments in that they testify to

the articulations and separations, the necessary

relations for the cohabitation of entities that can

only find their own identity when confronted

with each other.

The point is, we are no longer discussing the

conservation neither of the old stones so dear to

Ruskin nor of an empty space. In this case, we are

asked how to conserve spaces that exist only in

relation to the gaps that induced them – gaps that

are in perpetual transformation.

This study allows us to conclude that in Shibuya,

the conservation of spaces as necessary gaps

between urban entities did not even have time

to be discussed. As suddenly as they appeared in

the city so were these open spaces almost entirely

occupied, pregnant with new functions.

In Japan, this result can be explained by the

particularities of the real-estate policy undertaken

by railway companies, private investors owning

land below their train lines, land that is one more

source of revenue. Shibuya’s centrality is an asset.

Not even the smallest land plot will be wasted.

The proximity of an elevated road or railway does

not seem, under these conditions, to be regarded

merely from its negative impacts such as noise

and air pollution. But does this fact suffice to

explain this apparent better tolerance to the

proximity of an elevated road in Japan? What

are the means by which Japanese escape from a

feeling of space cluttering and high density? Can

the study of proxemics, to which Edward T. Hall

(1963) was devoted, explain such tendencies in

Japan? Do other non-physical forms of gap exist

in Japan?

In the case of Shibuya, we believe that the

saturation of physical space was coupled with a

search for new horizons and new landscapes.

First a cable-car, offering ‘extraordinary’ panora-

mic views, attempted to transcend the district’s

space saturation. Further on, a planetarium is

itself the proof of this search for increasingly

wider landscapes that proceed as the cityscape

becomes denser. Finally, the unknown is no

longer searched for in the infinitely big but

instead in the infinitely small – the consumable

item

displayed

on

the

electronic

screens.

Spatial saturation finds a path for expansion

inside itself.

Figure 12. Map of central Shibuya.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

17

URBAN DESIGN International

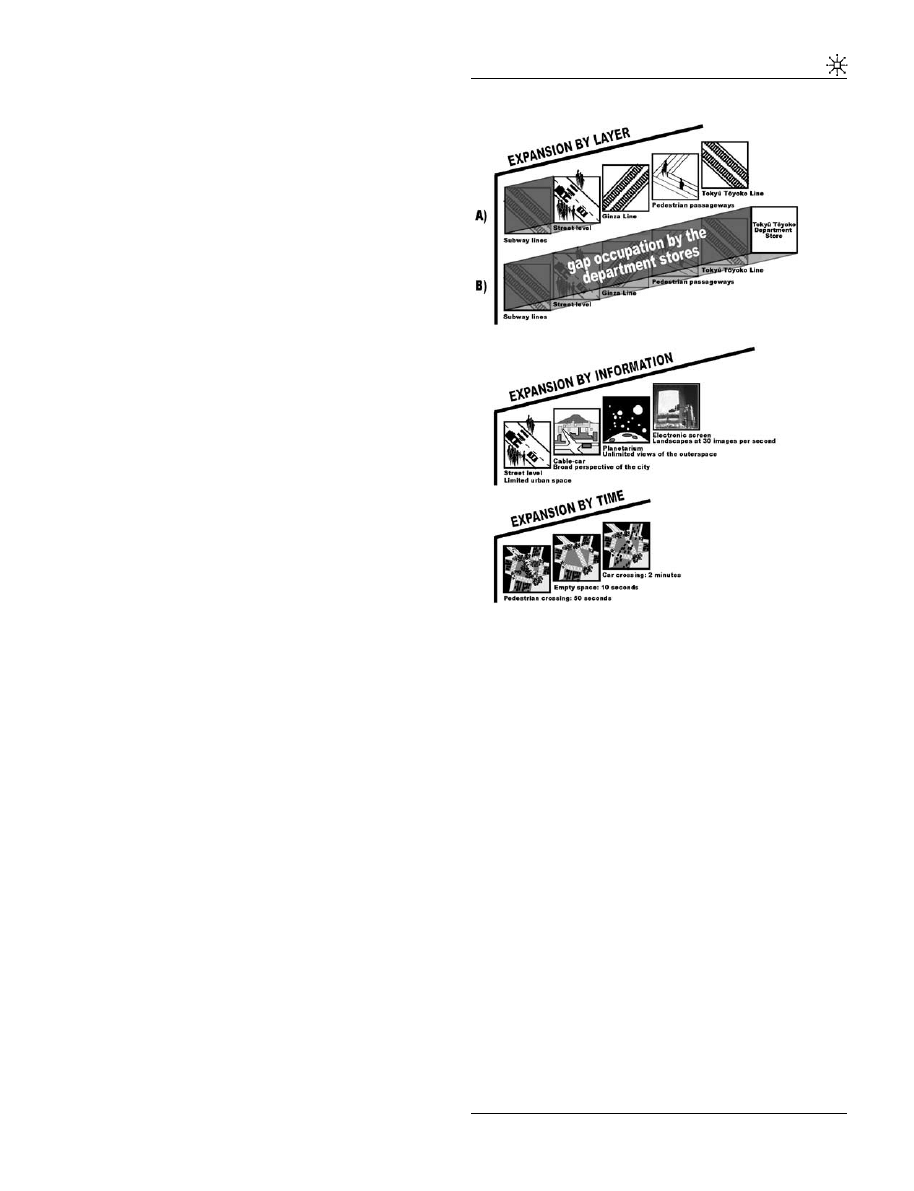

The diagrams here proposed (Figure 12) represent

formation models for the appearance and disap-

pearance of gaps. Three types of spatial expansion

are represented: an expansion by layer (super-

position of physical infrastructures), another by

the adding of information and finally one by the

use of time regulators (various functions alternate

in the same crossing space).

After observing these diagrams we might ask: are

these devices the means through which intensity

was allowed to increase? To answer this question

we are forced to ask another: would Shibuya be

bearable without its electronic screens and amu-

sement facilities? So instead of stating that

Japanese tolerate excessive intensity and density,

one should perhaps state that the Japanese have

taken the time to explore and reinvent certain

physical gaps through the use of visual and

temporal devices.

References

Appleyard, D., Lynch, K. and Myer, J. (1964) The View

from the Road. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Akai, T. (1976) Edo jidai zushi, Edo san, ni [Illustrated

Maps from the Edo Period: Edo Volumes Three and

Four]. Tokyo: Chikuma Shoboˆ.

Aoki, M. (2002) Railway operators in Japan 4, central

Tokyo, Japan Railway & Transport Review, 30: 42–53.

Ashihara, Y. (1989) The Hidden Order. Tokyo and New

York: Kondansha International.

Aveline, N. (2003) La ville et le rail au Japon: L’expansion

des groupes ferroviaires prive´s a` Toˆkyoˆ et Osaka. Paris:

CNRS E´ditions.

Bachelard, G. (1958) La poe´tique de l’espace. Paris: Presses

Universitaires de France, The Poetics of Space.

Boston: Beacon Press (English edition) 1994.

Bonnin, P. (2000) Dispositifs et rituels du seuil: une

topologie sociale, De´tour japonais [Communications],

70

: 65–92.

Borges, J. (1st edn. 1952, 1986) Enqueˆtes, Be´nichou, P.

and Be´nichou, S. (trans.) Paris: Collection N.R.F.,

Gallimard, pp. 15–24.

Choay, F. (1969) Espacements: Essai sur L’e´volution de

L’espace Urbain en France. Paris, (Re-edition) 2003

Milano: Skira editore.

Choay, F. (1992) L’alle´gorie du patrimoine. Paris: Seuil.

Cluzel, J. and Nishida, M. (2007) Le temps des

monuments face au temps de l’histoire, Bulletin de

l’E´cole Franc¸aise d’ExtreˆmeOrient (in press).

Depaule, J. and Bonnin, P.dir. (2002) L’impossibilite´ du

vide: fiction litte´raire et espaces habite´s, Commu-

nications, Manie´res d’habiter, 73: 233–243.

Glaeser, E. (2000) Demand for density? The functions of

the city in the 21st century, The Brookings Review,

18

(3): 10–13.

Hagawa, T. (2000) Shibuya Eki to sono shuˆhen: Natsukashi

no densha to kasha [Shibuya Station and its Environs:

The Memories of Trains and Locomotives]. Kawazaki:

Tamagawa Shinbunsha.

Hall, E. (1963) A system for the notation of proxemic

behavior, American Anthropologist, New Series

65

(5): 1003–1026.

Hall, E. (1966) The Hidden Dimension. New York:

Doubleday.

Halprin, L. (1966) Freeways. New York: Reinhold

Publishing Corporation.

Hillier, B. and Furuyama, M. (2003) L’architecture

comme interface environnementale entre les cul-

tures, Symposium Franco-Japonais, E´cole d’archi-

tecture La Villette. Paris.

Hillier, B. and Hanson, J. (1984) The Social Logic of Space.

Cambridge (New York): Cambridge University Press.

Ishikawa, K. (1992) Toˆkyoˆ daikuˆshuˆ no zenkiroku [Complete

Records of Tokyo’s Great Air Raids]. Tokyo: Iwanami

Shoten.

Jacobs, J. (1961) The Death and Life of Great American

Cities. New York: Vintage Books.

Koolhaas, R. and Mau, B. (1995) Small, Medium, Large,

Extra-Large. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

Lynch, K. (1960) The image of the city. Cambridge: MIT

Press.

Lynch, K. and Southworth, M. (1990) Wasting Away. San

Francisco: Sierra Club Books.

Miyata, M. and Hayashi, J. (1985) Tetsudoˆ to machi,

Shibuya eki [Railways and the City, Shibuya Station].

Tokyo: Taisho Bansha.

Mumford, L. (1961) The City in History. New York,

Harcourt: Brace & World.

Nora, P.dir. (1997) Les lieux de me´moire vol. 3. Paris:

Gallimard.

O

ˆ ta Hirotaroˆ. (1946) Nihon kenchiku-shi josetsu [Introduc-

tion to the History of Japanese Architecture]. Tokyo:

Shoˆkokusha, last edition (1989).

Shibuya, K. (1952) Shibuyakushi: Zen [The History of

the Shibuya District: Complete]. Tokyo: Shibuya

Kuyakusho Hen.

Tiry, C. (1997) Impact of railways on Japanese Society &

Culture, Tokyo Yamanote Line – Cityscape Muta-

tions, Japan Railway & Transport Review, 13: 4–11.

Tuan, Y. (1998) Escapism. Baltimore and London: The

Johns Hopkins Press.

Virilio, P. (1995) La vitesse de libe´ration. Paris: E´ditions

Galille´e.

Virilio, P. (1984) L’espace Critique. Paris: Christian

Bourgois Ed.

Yamamoto, Y. (1995) Koˆka tetsudoˆ to machizukuri (ke).

Koˆka kenchikubutsu no kankyoˆ dezain to shimin sanka;

Elevated railways and urban design (under) [Environ-

mental Design of Elevated Roads and the Participation

of the Population]. Tokyo: Chiiki Kagaku Kenkyuˆkai.

Suggested reading on Tokyo’s urban

and transportation history and space

use in Japan

Adachi, F. and Bonnin, P. (2000) Esthe´tique et urbanite´:

aperc¸u japonais, Espaces et Socie´te´s, 100: 127–156.

Bel, J. (1980) L’espace dans la socie´te´ urbaine japonaise.

Paris: Publications orientalistes de France.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

18

URBAN DESIGN International

Berque, A. (1976) Le Japon, gestion de l’espace et

changement social. Paris: Flamarion.

Berque, A. (1993) Du geste a` la cite´: formes urbaines et lien

social au Japon. Paris: Gallimard.

Berque, A. dir. (1994) La maıˆtrise de la ville: urbanite´

franc¸aise, urbanite´ nippone. Paris: E´cole des Hautes

E´tudes en Sciences Sociales.

Buci-Glucksman, C. (2001) L’esthe´tique du temps au Japon,

Du zen au virtuel. Paris: Galile´e.

Fie´ve´, N. and Waley, P. (2003) Japanese capitals

in historical perspective, place, power and memory

in Kyoto, Edo and Tokyo. London: Routledge

Curzon.

Goto, T. (2001) New stations based on philosophical

reunion of diversed Technologies, Japan Railway &

Transport Review, 28: 32–41.

Kitagawa, D. (2000) Visual aspects of urban railways

in Paris and Tokyo during the early railway period,

Japan Railway & Transport Review, 23: 32–35.

Koyama, Y. (1997) Railway technology today 1. Railway

construction in Japan, Japan Railway &Transport

Review, 14: 36–41.

Maeda, T. (1999) Railway technology today 9. Protect-

ing the trackside environment, Japan, Railway &

Transport Review, 22: 48–57.

Miura, S., Takai, H., Uchida, M. and Fukada, Y. (1998)

Railway technology today 2, The mechanism of

railway tracks, Japan Railway & Transport Review, 15:

38–45.

Pons, P. (1988) D’Edo a` Tokyo. Me´moires et modernite´s.

Paris: Gallimard.

Toˆkyoˆshi Shibuya Kuyakusho. (1982) Shibuya wa, ima

[Shibuya, now]. Tokyo: Dainippon Insatsu Kabush-

ikigaisha.

Tomioka, K. (1992) Kieta machikado: Toˆkyoˆ [Vanished city

corners: Tokyo]. Kamakura: Gendosha.

Tomioka, K. (1991) Watashitachi no Shibuya [Our

Shibuya]. Tokyo: Aihara Insatsu Kabushikigaisha.

Promenade into the gap

P. Hormigo et al

19

URBAN DESIGN International

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Promenedetyka kultury, Nauka, Kulturoznawstwo, Semestr II

promenades

FACMF500S TOKYO

[architecture ebook] H Style Furniture Store, Omotesando, Tokyo, Kazuyo Sejima & Associates dg2005

introducing tokyo

Promenedetyka kultury, Nauka, Kulturoznawstwo, Semestr II

Blaupunkt RDM169 Tokyo, Radia samoch. - PDF

Bebe promenade

Se promener

for the pleasure for people promenades

Tokyo Tea

Deep Purple Woman From Tokyo

RADIOACTIVE CONTAMINATED WATER LEAKS UPDATE FROM THE EMBASSY OF SWITZERLAND IN JAPAN SCIENCE AND TEC

Richard Clayderman Promenade Dans Les Bois

Hamao And Hasbrouck Securities Trading In The Absence Of Dealers Trades, And Quotes On The Tokyo St

TOKYO DOC

Steve Hackett The Tokyo Tapes

061 Darcy Emma Weekend w Tokyo

więcej podobnych podstron