60

Exploring business incubation from a family

perspective: How start-up family fi rms experience the

incubation process in two Australian incubators

Hermina HM Burnett

Murdoch University Business School

South St, Murdoch, 6150

Western Australia, Australia

Adela J McMurray

RMIT University College of Business

Melbourne

Victoria, Australia

Corresponding author: h.burnett@murdoch.edu.au

Abstract

This qualitative study explored how family start-up fi rms, housed in an incubator during their fi rst three

years of operation, experienced the business incubation process. There is limited research conducted on family

business experiences during the start-up phase when money is tight, entrepreneurial activity is basic and

business know-how is in its infancy (Dyer, 2003). Thus, the purpose of this study was to identify the reasons

why start-up entrepreneurs choose to locate their fi rms in an incubator setting and how two incubators

assisted the family fi rms to build their business going through the incubation process.

The research sample consisted of twelve start-up entrepreneurial family fi rms of which seven were located in

the Brunswick Business Incubator (BBI) and fi ve located within the Monash Enterprise Centre (MEC) in

Melbourne, Australia. Data were collected via semi-structured interviews then analysed using NVivo7

following a grounded theory approach. The fi ndings showed the majority of start-up family fi rms moved into

an incubator environment because they were not familiar with business practices, felt isolated working from

home, were hoping to share business ‘ know how’, to fi nd other family business entrepreneurs, and hoping to

fi nd a small business ‘community’ in which they could participate and network.

In addition, the fi ndings revealed that for family start-ups, the boundaries between personal relationships and

business relationships appeared to dissolve or overlap, and relationships with other tenants and the incubator

manager developed from a strong trust base and camaraderie.

The value of this study is threefold. First, the study’s fi ndings contribute to Habbershon, Williams and

MacMillan’s (2003) assertions that viewing family fi rms as a meta-system is meaningful, as it sheds light on

the organisational behaviour of small family fi rms based within incubator environments. Secondly, Chua,

Chrisman and Steier’s (2003) and Dyer’s (2003) concerns that family variables are regularly omitted from

the main stream management literature, and third, Hackett and Dilts’ (2004a:56) observation that there is

a shortage of variables “explaining how and why the incubation process leads to specifi c incubation outcomes”.

The analysis uncovered emerging themes which were similar to each of the family businesses, yet there were

subtle differences within each theme. These fi ndings support Melin and Nordqvist’s (2007) assertion that

whilst there is emphasis on similar characteristics displayed by family businesses, there are differences within

the categories that researchers often underestimate. Given the lack of studies addressing both the ‘within

family category’ research and ‘ family businesses located in incubators’ research, this fi eld study identifi es and

addresses a gap in the family business literature whilst also contributing to incubation research.

Keywords: Start-up family fi rms, business incubation, small business.

61

Exploring business incubation from a family perspective

Introduction

Incubation

The incubation literature shows a lack of family research studies conducted within incubator contexts.

Thus the aim of this study is to explore how 12 family start-up fi rms experience the incubation process

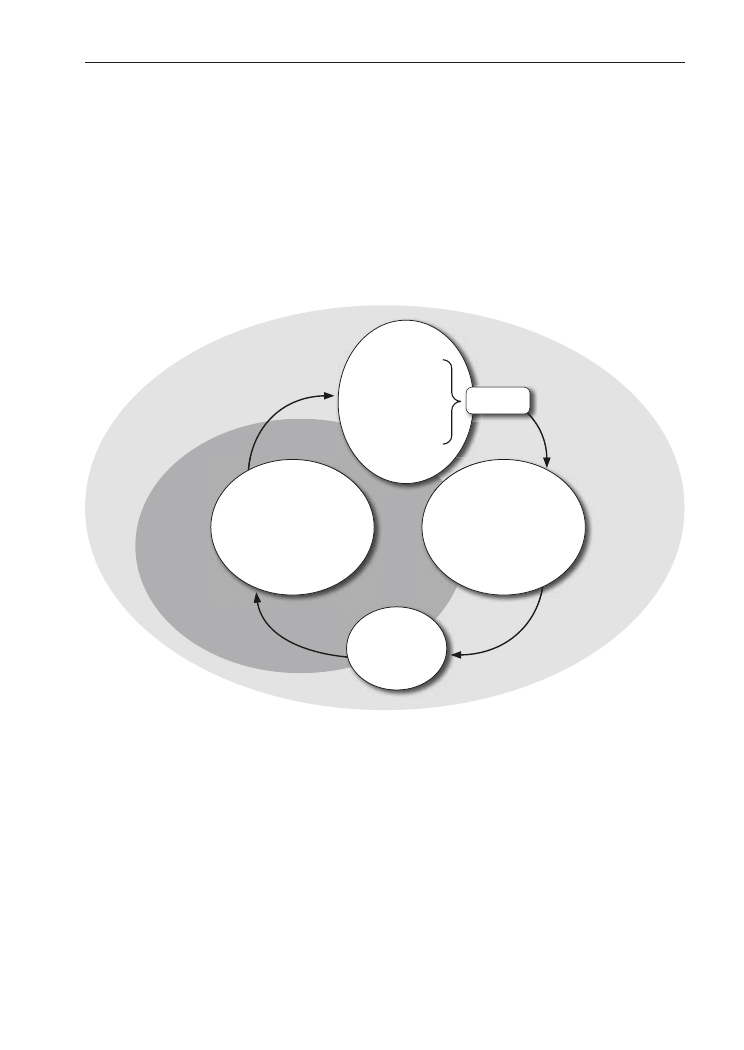

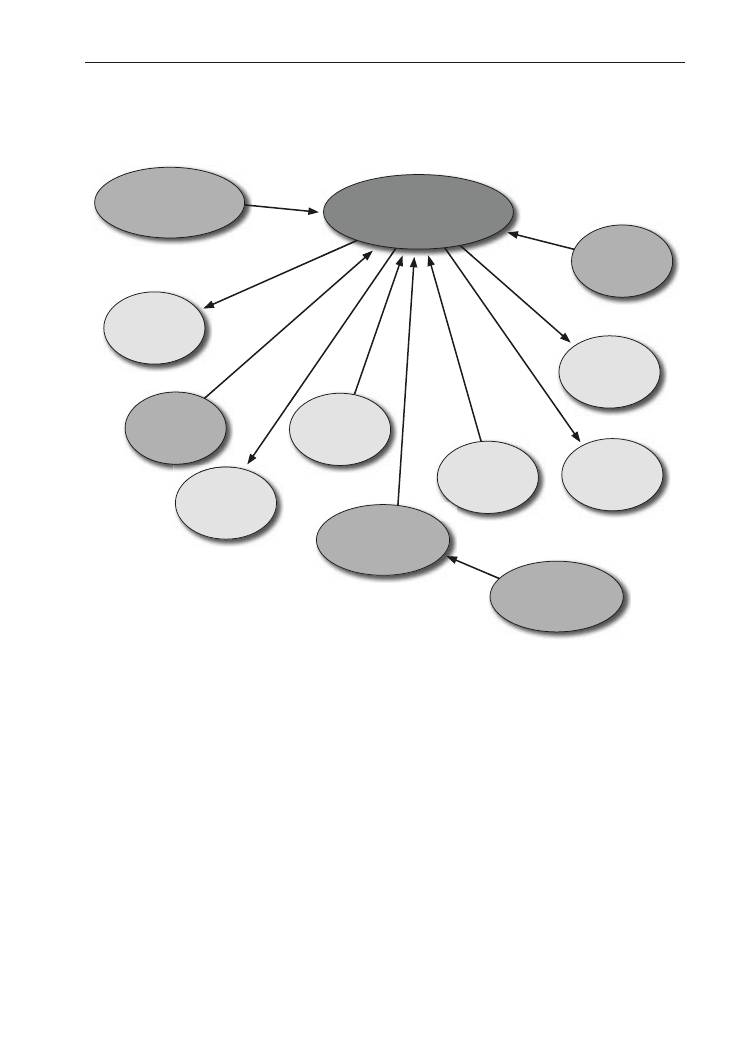

and why they choose that particular business environment. The incubator concept that was adopted in

this study is illustrated in Figure 1 below and shows an incubator as being a catalyst for business growth,

and functioning as a bridge between the internal ‘protected’ incubation environment and the external

‘exposed’ business environment.

Figure 1: Basic Incubation Concept

Space, equipment,

Business services

Mentoring, advice,

networks

Monitoring tenant

performance

New

business

recruitment

New technologies,

products, services

New networks

Joint ventures,

partnerships

Inside

incubator

environment

Outside

incubator

environment

Local business

community

Civil society

Global environment

Graduation

Source: Burnett, 2009, p. 16.

A business incubator is viewed here as an entity, mostly incorporating a physical facility (offi ce, industrial

or factory space) that assists new business growth by providing incubator tenants (start-up entrepreneurs)

with access to internet access, shared equipment, administrative services and sometimes access to

fi nancial resources, including venture capital, during their fi rst years of operation (Mian, 1997).

Business incubators also provide a ‘nurturing’ context (European Commission, 2002; NBIA, 2004;

OECD, 1999; UKBI, 2007). They often offer business advice, business monitoring and facilitate

strategic networking and business seminars to the new start-ups (Allen and McCluskey, 1990; Barrow,

2001; Bøllingtoft and Ulhøi 2005; Burnett, 2009; Hansen et al, 2000; Smilor and Gill, 1986). The

incubator thus functions as a nurturing bridge between the inside, somewhat protected incubation

environment, and the outside real-world business environment.

Over the past 25 years, incubation has proved itself as being so successful in the assistance of start-ups

that the phenomenon has become a fast growing and popular ‘economic development tool’ for the

62

development and sustainment of local and regional economies, specifi cally in low socio-economic areas

(Allen and Rahman 1985; Barrow 2001; Bøllingtoft and Ulhøi 2005; Campbell and Allen, 1987;

European Commission, 2002; Hackett and Dilts, 2004a; Sherman and Chappell, 1998).

Incubation in an Australian context

There are approximately 80 small business incubators in Australia that are sponsored, in one form or

another, by the Australian Government. The incubators house approximately 1,200 start-up businesses

or incubator tenants (BIIA, 2009; TPIA, 2006). Most incubators are not-for-profi t entities and generally

classifi ed according to their fi nancial sponsors or stakeholders, such as (local) government, universities

or technology parks (Allen and McCluskey, 1990; Barrow, 2001; Hulsink and Elfring, 2001; Rice and

Matthews, 1995; OECD, 1999; Bhabra-Remedios and Cornelius, 2003). Space offered by the various

incubators ranges from light industrial, factory per square meter, or serviced offi ces of various sizes to

fully equipped laboratories, and their tenants range from light manufacturing, wholesaling, food

processing to Bio-technology, ICT and a variety of other business services and consultancies, including

building industry, medical, art and crafts and fashion design (Barrow, 2001; Pacholski, 1988; NBIA,

2004; OECD, 1999; Rice and Matthews, 1995).

Family fi rms and incubation

During the fi rst years of trading, start-up entrepreneurs are faced with tasks they may not have previously

encountered, such as building a customer base, developing and or selling products and services and

accessing resources such as capital, equipment and networks (Schaper and Volery, 2007; Timmons and

Spinelli, 2003; Wiklund, 1999). Therefore, the aim of this research is to contribute to a better

understanding of how start-up family fi rms experience and build new relationships and networks within

business incubators to facilitate the entrepreneurial process.

Family dynamics and family fi rm behaviour

A large number of successful businesses are run by family structures and over the past ten years family

business research, including the challenges of start-up family-controlled fi rms, has increased (Hoy and

Sharma, 2006) and is being recognised internationally and in Australia (Connolly and Jay 1996; Barrett

and Rajapakse (2003). In the US alone, family businesses comprise over 90% of businesses employing

59% of the workforce (Dyer, 2003). In the UK, 73% of businesses are defi ned as family businesses

(Poutziouris, Sitorus and Chittenden, 2002) and in Australia, 67% of businesses are family owned

(Smyrnios and Walker, 2003). These businesses generate over 50% of Australia’s employment growth

and thus contribute substantially to Australia’s economy and wealth creation (Smyrnios, Romano and

Tanewski, 1997).

Defi nitions, characteristics and social structure of a family business

Research views the defi nition of a family business as complex. Most defi nitions focus on the important

role the family plays in terms of the running of the business (Birley, 2001), or focus on family relationships

based on blood or marriage (Westhead and Cowling, 1998). Others focus on the control of the business,

for example, through a clear majority of the ordinary voting shares (Naldi et al., 2007). In studies

addressing the running of a business, defi nitions focus on vision, strategy, control of the business and

succession (Chua, Chrisman, and Sharma, 1999; Habbershon, Williams and MacMillan, 2003;

Astrachan, Zahra and Sharma, 2003). Many start-ups, particularly those located in a business incubator,

are the size of micro businesses with fewer than fi ve employees, hence, Westhead and Cowing (1998)

suggest if researchers decide to use a single family fi rm defi nition, they should consider utilising a

reasonably broad defi nition. For this reason, the authors utilised Westhead and Cowing’s (1998) broad

notion in the study in that start-up family fi rms were owned and personally managed by members of a

Small Enterprise Research 16: 2: 2008

63

family group, or groups of relatives and members who were related by blood or marriage.

The culture within a small family business is infl uenced by the values and norms of its founder and the

behaviour of other family member employees including their commitment to each other and the

organisation (Hall and Nordqvist, 2008; McMurray et al., 2004). Hence, the characteristics of family

businesses are unique, as the whole institution of family impacts on the business’ strategic plan and on

processes such as decision making, culture and organisational leadership (McMurray, 2003; Melin and

Nordqvist, 2006; Sharma, 2004).

Small family fi rms possess that unique mix of social, human, and fi nancial capital, which can combine

family matters and community building with the generating of income (Astrachan, Zahra and Sharma,

2003). It could be said that family fi rms are more ‘personal’ businesses than non-family fi rms and have

business objectives that differ from non-family fi rms, preferring to focus on the value and quality of

family relationships or particular forms of altruistic behaviour (Barrett and Rajapakse, 2003; Dyer,

2003; Gomez-Mejia, Nunez-Nickel and Gutierrez, 2001; Habbershon, Smyrnios and Walker, 2003;

Williams and MacMillan, 2003). An example of this would be an owner who does not particularly care

about performance appraisals, accepts a lower turnover or lower return on investment when it involves

a family member, or is reluctant to fi re or discipline a family member employee. This attitude may be in

contrast to non-family businesses, which predominantly focus on fi nancial capital, business growth and

separation between family relationships and business life. Hence, small businesses function within

complex social systems (Van der Sijde, Groen and Van Bentham, 2004).

The social structure of family businesses may therefore be defi ned as a ‘‘meta-system’’ comprising of

three broad subsystem components: i) the controlling family unit, made up of the history, traditions,

and life-cycle of the family, ii) the business entity, representing the strategies and structures utilised to

generate wealth, and iii) the individual family member, including their interests, business skills, and life

experience (Habbershon et al., (2003). These three components bestow the family individuals with

complex interactive psychodynamics as they endeavour to make meaning for themselves whilst

interacting with the family, employees and business (Kets de Vries, 1996). In this context, incubators

may be viewed as learning organisations or learning communities, encouraging the members of family

fi rms to fi nd a sense of belonging and ‘familiness’ (Chrisman, Chua and Steier, 2005)

In addition to exploring family meta systems, this study utilised a network framework developed from

Higgins and Kram’s (2001) network theory to uncover the way in which incubator networks play a key

role in successful incubation and the development of new ventures, including family fi rms (Hackett and

Dilts, 2004b). Studies addressing networks often research notions of strong and weak bonds or ties

(Granovetter, 1973). Higgins and Kram (2001) identifi ed four different types of networks: i)

entrepreneurial networks, which they found to be high diversity networks with a strong development of

relationships, ii) opportunistic networks, with high network diversity but weak relationship strength,

iii) traditional networks, with low network diversity, but strong relationship ties, and iv) receptive

networks, having both low network diversity and weak relationship strength.

Three open research questions were designed to uncover why the family business chose to be located in

an incubator environment, their incubator experience, and the types of networks they used when

building incubator relationships.

The following broad research questions, accompanied by relevant sub-questions, underpinned this

study:

Research Q1:

Why do family start-up fi rms choose to grow their business in an incubator?

Sub questions regarding the move were broadly posed as:

How did the family fi rm experience business before they moved into the incubator?

What did the owners perceive were the advantages of moving into the incubator for their family?

Exploring business incubation from a family perspective

64

Research Q2:

How do family start-up fi rms experience the incubation process?

The sub questions regarding this research area was broadly posed as:

How would the family characteristics play a role in the incubator with regards to relationships?

Research Q3:

Which types of networks were used by family start-up fi rms when building relationships

within the incubator?

Sub questions regarding these research areas were broadly posed as follows:

What were their relationships like with other tenants in the incubator?

What were their relationships like with the incubator management?

Research Method

A qualitative case study approach, based on the personal nature of incubators, the research questions

and the absence of rich data addressing the research questions in the literature, was deemed as appropriate

to this study. In practical terms, this case study refers to the investigation of a phenomenon (family

fi rm) within its natural setting, by collecting detailed information about particular issues, frequently

including the accounts of subjects (Eisenhart, 1989; Yin, 2003). Two different incubators provided a

rich context within which to gather primary data from the relevant participants that met the criteria of

family business and incubators. The Brunswick Business Incubator (BBI), a large incubator in Victoria

based in the inner city of Melbourne and the Monash Enterprise Centre (MEC) a small incubator

located in an outer suburb 20km from CBD Melbourne. The BBI had facilities to house over 50 start-

ups and the smaller MEC had the capacity to house around 15 businesses at the time of research.

Operationalising Westhead and Cowing’s (1998) defi nition to identify family fi rms, and with the

support of incubator management, seven case organisations based at the Brunswick Business Incubator

(BBI) and fi ve case organisations based at the Monash Enterprise Centre (MEC) participated in the

study. Semi-structured interviews consisting of open ended questions guided the interview dialogue

which, as Witzel (2000) suggests, assists with familiarising both the researcher and participant with the

study’s key concepts and themes. In addition, the study followed grounded theory principles, which

seeks to methodically understand the context of what is being studied; investigating an organisation,

its managers or other actors, including their interactions and interrelationships (Glaser and Strauss,

1967).

Semi-structured interview questionnaire development

The concepts of reliability and validity of any measurement instrument, including an interview

schedule, are two fundamental aspects of the quality and rigor of measures (Hinkin 1995). This is

specifi cally so in qualitative research where the reliability is mainly achieved by describing carefully

which procedures have been used (Yin, 2003). Following a review of the incubation of start-up fi rms

conducted by the European Commission Enterprise Directorate-General (2002), the demographic

items were generated addressing family fi rm structure, age of fi rm, industry, age of owner, how long the

owner had been based in the incubator, the owner’s gender and number of staff.

Prior to conducting the main study, the study’s questions were pre-tested on four family businesses to

determine their appropriateness, content validity, and whether or not any additional items required

inclusion in the interview schedule. The main study followed where one hour semi-structured interviews

were underpinned by the study’s three main research questions, supported by sub questions to uncover

the themes of decision making, incubator experiences including services, and support, as shown in

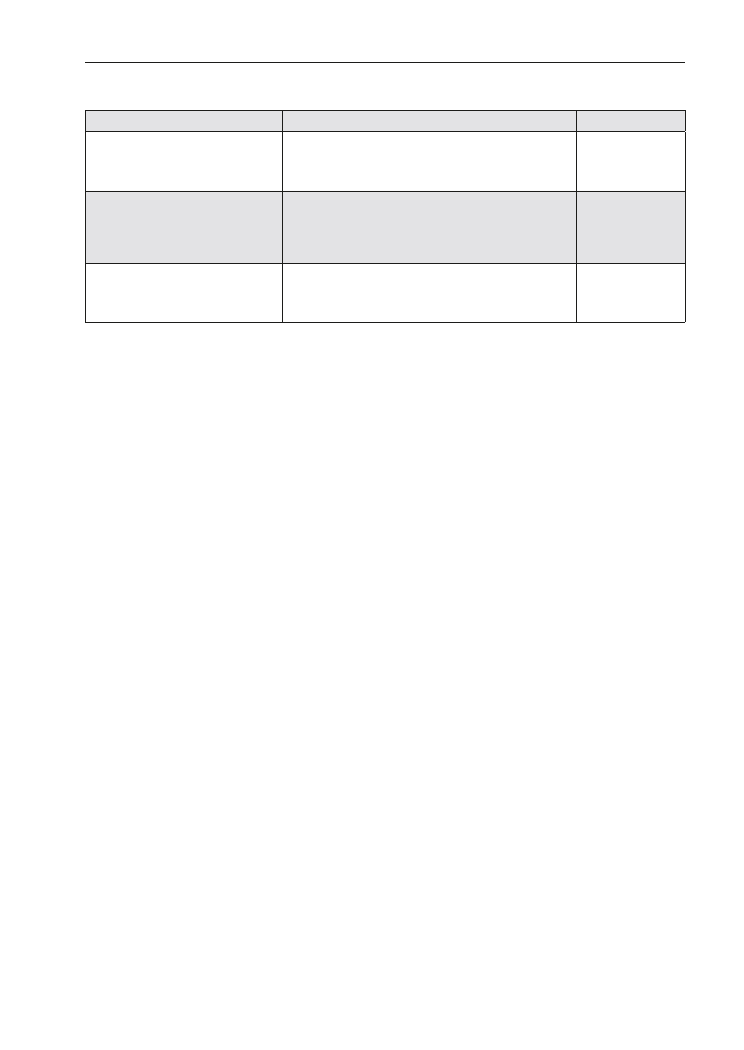

Table 1 below.

Small Enterprise Research 16: 2: 2008

65

Table 1: Research questions, sub questions and concepts.

Main Research Question

Sub Questions

Theme

Q1: Why do family start-up fi rms choose

to grow their business in an incubator?

1. How did the family fi rm experience business before they

moved into the incubator?

2. What were the advantages of moving into the incubator for

the family fi rm?

Decision making

Q2: How do family start-up fi rms

experience the incubation process?

1. What were the experiences of the owners using incubator

service and how was the incubator making a difference to their

family fi rm?

2. How would the family characteristics play a role in the

incubator with regards to relationships?

Incubator experiences

including services

Q3: Which types of networks were used

by family start-up fi rms when building

relationships within the incubator?

1. What were family fi rms’ relationships like with other tenants

in the incubator?

2. What were family fi rms’ relationships like with the incubator

management?

Networks and

support

Source: Authors

Being semi-structured in design, the questions were used as a guide or springboard, designed to elicit

dialogue discussing the advantages and disadvantages of previous business premises, reasons participants

moved into incubators and the types of relationships they formed. Further discussion addressed

networking and communication between the incubator tenants and incubator management and how

the participants rated the importance of the incubator to the survival of their business. In addition, data

was collected about internal trading or cross-selling and the development of joint ventures between

tenants to demonstrate incubator experiences based on mutual support and trust.

Analysis and Outcomes

Rich primary data benefi t greatly from using an ordered theory-based approach during the coding

process. This is why grounded theory was used as a method of analysis. The method is based on Glaser

and Strauss’ (1967) discovery of grounded theory, which was aimed to provide insights on how to

generate new theory from research that was grounded in data, rather than through the deduction of

hypotheses from existing theories. Glaser (1992) defi nes grounded theory as:

“…a general methodology of analysis linked with data collection that uses a systematically applied set

of methods to generate an inductive theory about a substantive area” (Glaser, 1992: 16).

In this case, this was an open coding process (coding text into so called free ‘nodes’ or ‘meaning units’),

followed by axial coding (identifying relationships between the open coded or free nodes) and selective

coding (selecting core variables and dependent variables) process. In practice, this meant that the coding

process consisted of sifting through text identifying experiences and labelling coded passages, words or

paragraphs either as specifi c nodes (independent variables) or as dependent variables under those specifi c

nodes. In line with the grounded theory approach, the research database was examined through a

continuous and cyclical process of familiarising, coding, conceptualising, cataloguing, re-coding and

evaluating of the data, until the researchers were able to identify distinct themes that described the

experiences and behaviours of family business partners in relation to the incubator process.

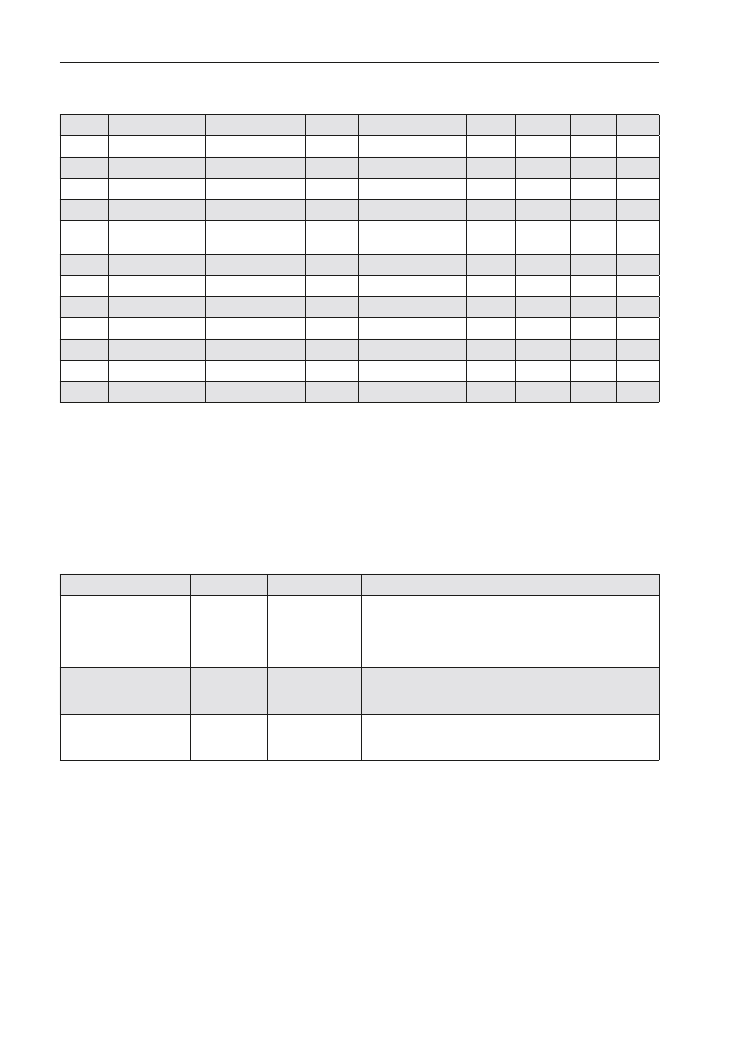

Family Firm Demographics

Table 2 shows the demographics of the participants by type of business, family structure, age of business,

how long the owners had been based in the incubator, gender and age group and the number of

employees including the owner (s). Besides the participants, no other family members were actively

involved in the business and there were no family fi rm participants representing age groups between

18-25 years and 51-65 years.

Exploring business incubation from a family perspective

66

Table 2: Firm Demographics

Type of Business

Family Structure

Firm Age

Time in Incubator

Gender

Age

Loc.

Staff

1

IT

Married

0.7

<12

months

M

26-35

BBI

6

2

Software design

Father / son

2.9

<12 months

M

36-50

BBI

8

3

Printing

Mother /daughter

1.5

>12 months

F

26-35

BBI

2

4

Apparel

Married

2.8

>12 months

M

26-35

BBI

3

5

Management

consultants

Married

1 <12

months

F

36-50

BBI

2

6

IT search engine

Brothers

2.6

<12 months

M

36-50

BBI

2

7

Graphic Design

Married

1.7

>12 months

M

26-35

BBI

2

8

Building

2 married couples

1

<12 months

F

36-50

MEC

4

9

Business Services

Married

3

>12months

F

26-35

MEC

2

10

Vocational training

Married

1.6

>12 months

F

36-50

MEC

3

11

Building

Married

1.8

<12 months

M

26-35

MEC

4

12

Recruitment

Mother and son

2.6

>12 months

M

26-35

MEC

5

Source: Authors

Outcome of the three interview questions

The three core nodes representing the research questions: ‘Why Incubation’, the ‘Use of Services’, and

the types of ‘Networks and Relationships’ were answered by all participants (sources). This was

uncovered several times and from various angles using different words or phrases. Table 3 below

describes the meanings given to each theme.

Table 3: Tree nodes (Variables)

Outcome Coding Process

No of sources

No of references

Node Description (Meaning Unit)

Why Incubation

12

34

Reasons for moving into the incubator. These could be fi nancial

reasons, (e.g., words like cheaper, economical) business

assistance or other mental reasons, such as wanting to leave

home, looking for other start-ups or networks or personal

reasons.

Use of Services

12

26

Covers words or phrases that represent incubator services such

as equipment, admin support, networks, access to seed capital,

business training, events.

Relationships

12

21

Types of relationships existing in the incubator and with whom

(e.g., making friends, visits, networking, mentoring, socialising,

and doing business with.

Source: Authors

Findings and discussion on the why of incubation

To gain an understanding of research question one: what drove the start-up family fi rms to move from

home or previous premises into an incubator environment; related nodes were identifi ed and labelled in

relation to their meaning (why). These were then modelled by frequency (number of times mentioned

by participant) and signifi cance (is it important). If they were mentioned by many sources and mentioned

several times, they were labelled ‘parent’ node (important) and if they were mentioned by less than half

the sources and few times they were labelled ‘child’ node, which meant they were of less importance. If

they were mentioned by fi ve to seven sources, but only once, they were labelled ‘sibling’, meaning they

were important, but not the overriding reason to move into the incubator. Any words or meaning units

Small Enterprise Research 16: 2: 2008

67

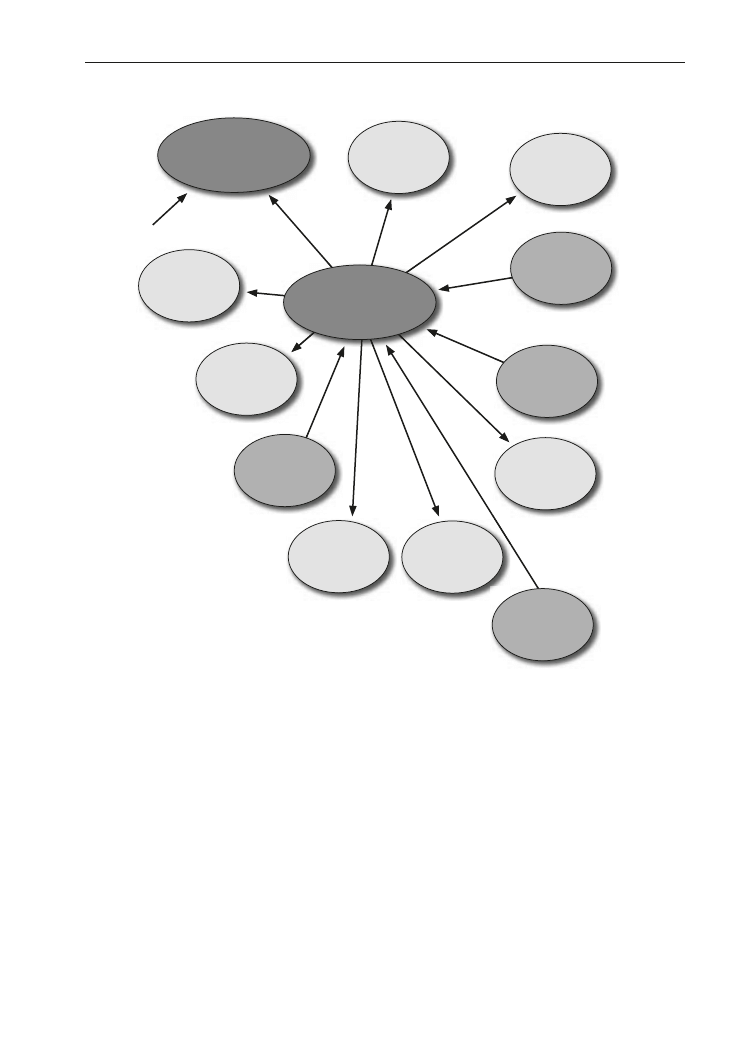

mentioned fewer than three times were excluded from the research. Figure 2 shows the fi rst research

question as identifi ed in the NVivo7 analysis process model.

Figure 2: Why Incubation?

Why of incubation

Location advantages

Local business

comes into

incubator

BI services

Role models

Economical

Sibling

Child

Parent

Child

Parent

Parent

Sibling

Sibling

Sibling

Child

Parent

Networking

Joint business

ventures

(Better)

survival rate

Access to

funds

Business

expansion

Isolation in

previous premises

Source: Authors

As can been seen from Figure 2, there were 11 reasons to move into an incubator according to the

participants, but there were three main reasons (parents). The fi rst reason and predominant one was the

feeling of being isolated from others whilst working from home; this led to the second reason, the

opportunity to network with others; and the third

reason, access to the various incubator services. Isolation was mentioned more than once by seven

different sources during the interview. Networking was mentioned by all participants and access to

incubator services was also raised by all participants. The opportunity to expand the business and the

incubator location were viewed as being a particular incubator advantage by half of the participants.

Several extracts from interviews are introduced here to provide a true sense of the gathered data and to

illustrate how the needs of the fi rm are driven by the owners’ circumstances during the start-up phase

of the fi rm’s lifecycle, moreover, how the various components within mega system interact (Habbershon

et al., 2003). In addition, they illustrate the difference in meaning from one family fi rm to the other, as

noted by Melin’s and Nordqvist’s (2006) assertions that whilst there are similarities within the family

fi rm, there are differences within categories.

Exploring business incubation from a family perspective

68

Participant 11:

“We were doing very well working from home. We each have a different role in the business,

but my wife was struggling after a few months and told me that we did not network enough. She needed more

and looking back she was right, because our (marketing) ideas were drying up. Sitting at home working was

not enough for her. I used to go out visiting customers, but she did the books and the phone and did not really

get out much, other than to pick up the kids from school and doing the shopping. Our lives changed after we

moved into the incubator and she loves it here.” The participant appears to imply that there was a ‘family’

as well as ‘business team’ with both partners attending to family as well as business matters. He also

implies that the incubator environment and networks were assisting with bringing relationships and

creativity back into the business.

The importance to keep home and business lives balanced triggered other responses.

Participant 4:

“After the baby was born, we felt very isolated and wanted to meet with other business owners

in our position. We were forever working in our business and changing nappies, our relationship suffered, our

business suffered and I said: we need to get out of here…” Also these participants felt isolated. However,

this time it was a male rather than female owner who seemed to lack a business environment. A similar

perspective was provided by Participant 7 stating: “…Another advantage of this incubator is that we are

clustered together with other companies that are probably sharing the same teething trouble. That has given

us confi dence … a home based family business can be stifl ing. Being here (the incubator) has provided our

business but also ourselves with an outward focus…”

Finally, Participant 1 a software engineer sums up the ‘why’ “…..Support, I actually went out and looked

at how we could get some more business advice and support. We had three employees working in our house

and we had little privacy. I looked at service offi ces, but they were way too expensive. I also realised that if I

went with the normal offi ce scenario, I was dislocating myself from any support, like my neighbours, my

parents, everything, so what I did was to put myself into a situation where we had more instead of less support

to run the business.”

These fi ndings suggest that the small family teams were feeling isolated in different ways and were

seeking new ideas and support from others. However, each was driven by different motivators. Within

the households of participants 11 and 4, the work/life balance was at stake, while participants 1 and 7

were more successfully functioning family wise, but lacked space, motivation and being engaged with

other business owners. This fi nding supports Melin and Nordqvist’s (2006) assertions that there are

differences within theme categories when analysing family fi rm data, but also sheds new light on why

family businesses might not necessarily be better off working from home during the start-up phase and

how incubators provide another perspective.

Findings and discussion on the use of incubator services

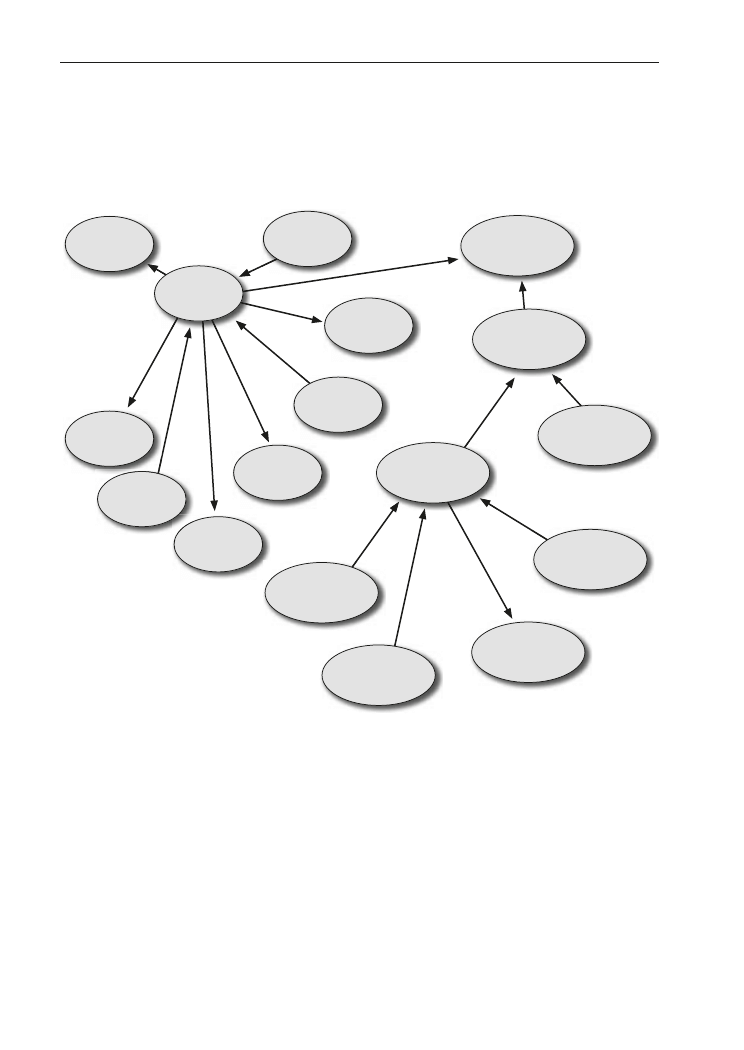

Figure 2 sheds light on research question two as various advantages and services were mentioned by all

participants as reasons for relocating into an incubator. Incubators were found to be more economical;

the location (e.g., close to home or school) played a role, and the provision of fl exible spaces and internal

expansion was also appreciated. However, incubator services are discussed in more detail in Figure 3

which shows the specifi c analysis in relation to the use of incubator services.

Small Enterprise Research 16: 2: 2008

69

Figure 3: Incubator services

Incubator services

The incubator

enterprise

Business

assistance

Business

training

Economies

of scale

Parent

Parent

Parent

Parent

Parent

Parent

Child

Child

Child

Child

Child

Child

Child

Access to

business

professionals

IP protection

and search

Access to other

(global) partners

Access to

funds

Physical Space

Mentoring

Access to

markets

Access to

networks

Source: Authors

Figure 3 shows 11 identifi ed nodes in relation to services that were of importance to the family start-ups.

However, four nodes particularly were prominent. These were; accessibility to markets, the participant’s

access to internal networks, the physical space that the incubator was offering, and the access to in-

house mentoring. The access to networks and business mentoring scored high, yet business assistance

such as help with books and records or administrative assistance did not. In all cases, the incubator size

appeared to be irrelevant, although two participants in the smaller incubator used the term ‘intimate

atmosphere’ and ‘like a home’. The access to other business markets was mentioned in the light that

incubator seminars provided access to other professionals and new customers. Networks and mentoring

are further discussed later in this paper.

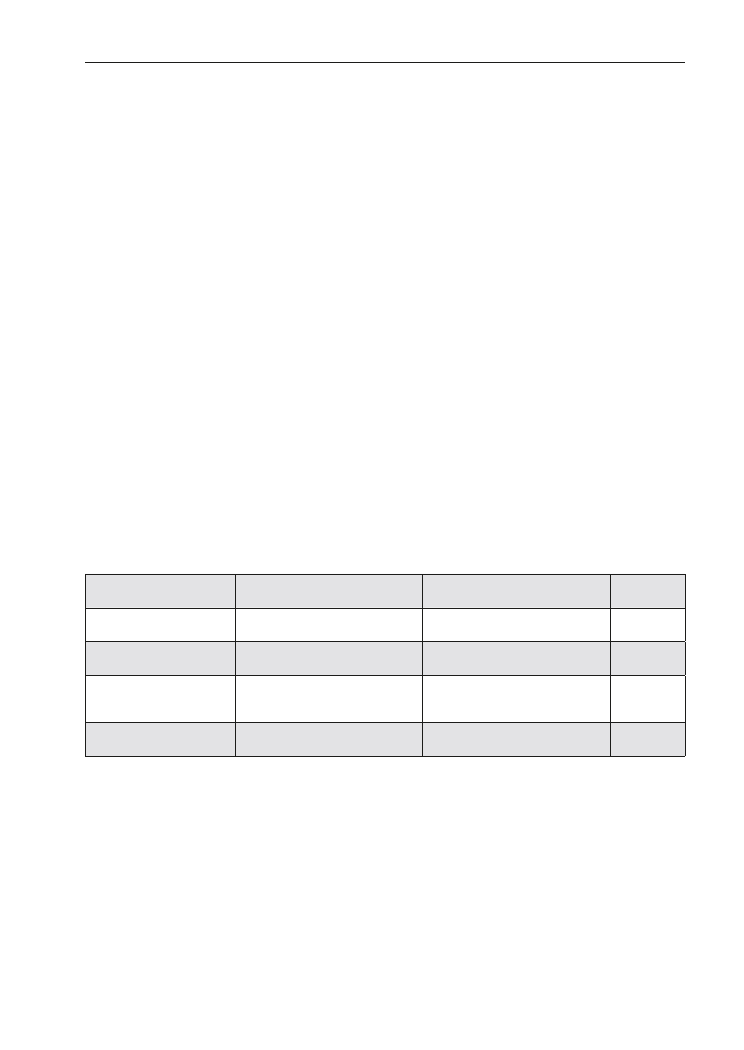

Findings and discussion on family fi rm relationships

Family fi rms rated a mentor or personal business advisor as highly important to the survival of their

business. The type of mentoring that occurred in both incubators embraced a variety of business issues,

for example, help with marketing strategies, such as identifying a market and developing a marketing

plan, IP protection, and other areas of business planning. Eight family fi rms regarded relationships with

their mentors with high levels of trust and indicated they encountered no problems disclosing personal

Exploring business incubation from a family perspective

70

challenges or fi nancial issues to their mentors. This was particularly indicated in the husband and wife

family fi rm partnerships. Analysis of the discourse addressing the item ‘Could you tell me about the

relationship you have with your mentor?’ generated data shown in Figure 4 and addresses the second

part of research question three pertaining to relationships.

Figure 4: Internal BI relationships

Source: Authors

Analysis in Figure 4 uncovered two related concepts in relation to the incubator process for family fi rm

relationships. These were networking and trust. NVivo revealed four nodes identifying major

relationships. Of these, three were labelled as most important. The fi rst being the relationships with the

incubator manager; the second being the relationships between particular tenants; and the third being

the internal fi rm relationships. In both incubators the incubator manager was seen as highly important

and both incubator managers were discussed as being mentor and friend of the family fi rms. Participants

clearly differentiated between the participation in ‘networking’ with other tenants and the making of

real ‘friends’. Extracts are as follows. Participant 10 states: “There are many events and networks here

such as the innovation group, who organise business lunches as part of their network events, but you also need

operational business owner networks just talking about business and how to do it”. Also Participant 2 feels

that, “We’ve built a small group of network contacts who are more than happy to be mentors for us, which is

very important”. Once there seemed to be a basis of trust, new relationships grew into friendships of

which some were perceived as becoming ‘part of the family’.

Collaboration

Friendship

Trust

Comfortability

Closeness

Familiarity

Respect

Belonging

Safe

Incubator

process

Incubator

relationships

External

relationships

Relationships with

BI manager

Relationships with

BI team

Family fi rm internal

relationships

Tenant to tenant

Internal BI

relationships

Parent

Parent

Parent

Parent

Parent

Parent

Parent

Parent

Child

Child

Child

Child

Child

Sibling

Sibling

Sibling

Small Enterprise Research 16: 2: 2008

71

Participant 12

(son of mother/son business) tells the story: “John (another incubator tenant, viewed by

participant as peer and mentor) has been a real mate…he has looked after my business on and off when my

father was very sick and is always there for us. I owe John …thanks to him my business is still here and making

money…”

To further illustrate similarities, yet differences, in these categories, Participant 3 discussed the

infl uence business mentors can have on family business partnerships. As the daughter of a mother/

daughter business stated: “Mum and I see our business advisor every month. It’s the time I feel I can really

talk about new ideas I have for the business. Shirley has become more a family friend than a mentor and she

knows that my mother bosses me around in the offi ce (laughs) …mum normally disagrees when I want to

change things like printing layouts for customers or try something new … she can so behind at times … so

now, when we get together with Shirley, I talk about anything. I feel Shirley is a bit like a buffer between my

mother and me and when she says it’s a great idea, my mother gives in.”

And a last example from Participant 11: “There’s a couple who I’m really good friends with, I invited them

to my kid’s fi rst birthday.” According to this participant, networks are: “Absolutely number one criteria. A

lot of people who start a business from home don’t have networks and coming into an incubator gives them

those networks. For any business, no matter how established it is, networking is always the key. I now give

seminars on strategic networking inside and outside the incubator.”

These statements reveal how business relationships turn into friendships and may possibly create

incubator communities with small family businesses at the centre of this development.

Findings and discussion on which types of networks

In answering the last research question: which types of networks were used by family start-up fi rms

when building relationships within the incubator, Table 3 provides an overview of the Higgings and

Kram (2001) networks that were identifi ed in the study.

Table 4: Network types sought by family business owners

Network Types

Network Description

Family

Number of

Participants

Entrepreneurial Networks

high diversity networks with strong

development of relationships

Looking for new business and new

relationships

5

Opportunistic Networks

high network diversity but weak

relationship strength

Looking for new business but keep to

the family relationships

1

Traditional Networks

low network diversity, but strong

relationship ties

Looking for other family businesses/

friends

4

husband /

wife teams

Receptive Networks

low network diversity and weak

relationship strength

Looking predominantly for clients and

relationships from inner circle

2

Source: Table developed from Higgins and Kram, 2001, pp. 264-288.

Analysis revealed that even though most start-up family fi rms sought ‘networking’ relationships, more

in-depth probing uncovered that the driving motivators were varied. Five sets of family businesses had

developed diverse networks with high interaction and four husband and wife teams were part of the

more traditional networks. Of these four, three couples emphasized the importance of meeting other

business ‘couples’, who could share their family business experience. What both groups had in common

however was that they were looking for strong ties within the networks; be it connected to a diversity of

contacts in a number of networks or just few specifi c business relations within one or two networks. The

emphasis was on the strength of the connection.

Exploring business incubation from a family perspective

72

Conclusion

Although this paper presents an explorative case study, the three research questions addressing why

family start-up fi rms choose to locate their businesses in an incubator, what services they seek and what

types of relationships they establish, sheds light on family behaviour in incubators and thus provides a

contribution to the literature.

The family businesses felt more isolated at home, were looking for other families to exchange business

experiences with and were obtaining business and also ‘family’ coaching. In this research sample, the

two incubators signifi cantly encouraged networking, the building of interpersonal relationships and

mentoring processes.

The study supports researchers such as Dyer (2003), Smyrnios and Walker (2003) and Barrett and

Rajapakse (2003) in asserting that family variables provide insights into small business team dynamics,

particularly family fi rms. However, these previous studies were not conducted on start-up family fi rms

during their fi rst years of trading and within incubator environments. It is in this way that the current

study provides an original contribution to the incubator and family literature.

The study’s fi ndings also support Melin and Nordqvist’s (2006) assertions that whilst there is emphasis

on characteristics displayed by family businesses, there are differences that are underestimated within

family business categories. This study confi rms differences in a specifi c Australian context and shows

that small family start-ups relocate into incubators for a variety of family circumstances; for example to

avoid isolation and to seek out different types of business networks, support and personal friendships.

Future research into this area may consist of using larger population samples and exploring family and

community entrepreneurship in different incubator settings.

Small Enterprise Research 16: 2: 2008

73

References

Allen, D N., and McCluskey, R. 1990, ‘Structure, policy, services and performance in the business incubator industry’,

Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 61–77.

Allen, D. N., and Rahman, S. 1985, ‘Small business incubators: A positive environment for entrepreneurship’, Journal of Small

Business Management, vol. 23, no. 3, pp. 12-22.

Axtell, C.M., Holman, D.J., Unsworth, K.L., Wall, T.D, Waterson, P.E., and Harrington, E. 2002, ‘Shopfl oor Innovation:

Facilitating the suggestion and implementation of ideas’, Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, Vol. 73, pp.265-

285.

Astrachan, JH, Zahra, S. A., and Sharma, P. 2003, ‘Family-Sponsored Ventures’, presented at the First Annual Global

Entrepreneurship Symposium: ‘The Entrepreneurial Advantage of Nations’ on 29th April 2003, New York, USA.

Barrett, R., and Rajapakse, T. 2003, ‘What is a ‘family business’ and why does it matter?’, Refereed paper, 16th SEAANZ

Conference 28th September – 1st October 2003, University of Ballarat, Vic, Australia.

Barrow, C. 2001, Incubators: A realist’s guide to the world’s new business accelerators, John Wiley & Sons Chichester (West

Sussex), UK.

BIIA – Business Innovation and Incubation Australia, June 2009, http://www.abbreviations.com/b1.aspx?KEY=346259.

Bell, S. and Smith, F. 2003, ‘La Trobe University R&D Park: a case study’, refereed paper, XX IASP World Conference on

Science and Technology Parks, 1st – 4 th June- Lisboa, Portugal.

Bergek, A. and Norrek, C. 2008 ‘Incubator best practice: A framework’, Technovation Vol. 28 pp. 20–28

Bhabra-Remedios, R. K. and Cornelius, B. 2003, ‘Crack in the Egg: Improving performance measures in business incubator

research’, Refereed paper, 16th SEAANZ Conference 28th September – 1st October University of Ballarat, Vic, Australia.

Birley, S. 2001, ‘Owner-manager attitudes to family and business issues: A 16 country study’, Entrepreneurship: Theory and

Practice, Vol. 26, no.2, pp.63-76.

Bøllingtoft, A. and Ulhøi, J. P. 2005, ‘The networked business incubator—leveraging entrepreneurial agency?’ Journal of

Business Venturing, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 265-90.

Burnett, H. H. M. 2009, ‘Exploring the parameters for the optimum funding of Australian incubators from an incubator

manager perspective’. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Australia, Swinburne University, Graduate School of Entrepreneurship.

Burnett, H.M. and McMurray, A.J. 2003, ‘Exploring the infl uence of communication on small business innovation and

readiness for change’, Journal of New Business Ideas and Trends, November 2004, Volume 2, No 2, pp. 1-11

Burnett, H.M. and McMurray, A.J. 2004, ‘Guidance and networking in a small business incubator environment for new

entrepreneurs: a study on entrepreneurship, mentoring and networking processes. 17th Annual SEAANZ Conference

‘Entrepreneurship as the Way of the Future’, 26 – 29th of September, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane

Burnett, H.M. and McMurray, A.J. 2005 ‘Innovation in small business incubators: how idea generation, networking and client

interaction lead to innovative practices in start-ups, 2nd Annual conference AGSE, 10th -12th February Swinburne University of

Technology, Hawthorn, Australia

Campbell, C. and Allen, D.N. 1987, ‘The Small Business Incubator Industry: Micro-level Economic Development,’ Economic

Development Quarterly, Vol. 1, No.2, pp. 178–191.

Chua, J.H., Chrisman, J., and Sharma, P. 1999, ‘Defi ning the family business by behaviour’, Entrepreneurship: Theory and

Practice, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 19-39.

Chrisman, J.J., Chua, J.H. and Steier, L. 2005, ‘Sources and consequences of distinctive familiness: An introduction’,

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 237-47.

Chua, J.H., Chrisman, J.J. and Steier, L.P. 2003, ‘Extending the theoretical horizons of family business research’,

Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 331-8.

Clarysse, B., Wright, M., Lockett, A., Van der Velde, E. and Vohora, A. 2005, ‘Spinning out new ventures: a Typology of

incubation strategies from European research institutions’, Journal of Business venturing, Vol. 20, pp. 183-216.

Connolly, G., and Jay, C. 1996, The Private World of Family Business. Melbourne: Pitman.

Dyer, W.G. Jr. 2003, ‘The Family: The Missing Variable in Research’, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 27, N. 4, pp.

401- 416.

Eisenhardt, K.M. 1989, ‘Building Theories from Case Study Research’, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp.532–

550.

Exploring business incubation from a family perspective

74

European Commission, (Enterprise Directorate General) 2002 ‘Benchmarking of Business Incubators’, Brussels.

Giorgi, A. 1985, ‘Sketch of a Phenomenological Method’ in Phenomenology and Psychological Research. Duquesne University

Press.

Glaser, B.G. 1992, Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis, Sociology Press, California, USA.

Glaser, B.G. and Strauss, A.L. 1967, The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research, Aldine Publishing Co.,

Chicago, USA.

Gomez-Mejia, L.R., Nuñez-Nickel, M. and Gutierrez, I. 2001, ‘The role of family ties in agency contracts’, Academy of

Management Journal, vol. 44. no. 1, pp. 81-95.

Granovetter, M. 1973, ‘The strength of weak ties’, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 78, No. 6, pp. 1360–1380.

Habbershon, T.G, Williams, M and MacMillan, I.C., 2003, ‘A unifi ed systems perspective of family fi rm performance’, ‘Journal

of Business Venturing’ Vol. 18, pp. 451–465.

Hackett, S.M. and Dilts, D.M. 2004a, ‘A Systematic Review of Business Incubation Research’, Journal of Technology Transfer,

Vol. 29, No 1, pp. 55-82.

Hackett, S.M. and Dilts, D.M. 2004b, ‘A Real Options-Driven Theory of Business Incubation’, Journal of Technology Transfer,

Vol. 29, No 1, pp. 41–54.

Hall, A., and Nordqvist, M. 2008, ‘Professional Management in Family Businesses: Toward an Extended Understanding,.

Family Business Review, Vol XXI (1), pp 51-69.

Hansen, M.T., Chesbrough, H.W., Nohria, N. and Sull, D.N., ‘Networked Incubators’, 2000, ‘Harvard Business Review, Sep/

Oct 2000, Vol. 78, No.5, pp.74-84.

Higgins, M.C. and Kram, K.E. 2001, ‘Reconceptualizing mentoring at work: a developmental network perspective’, Academy

of Management Review, April 2001, Vol. 26, No 2, pp. 264-288.

Hinkin, T.R. 1995, ‘A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations’, Journal of Management. Vol 21, No.5,

pp. 967-988.

Hoy, F. and Sharma, P. 2006, ‘Navigating the Family Business Education Maze’, in P. Poutziouris, K. Smyrnios and S. Klein

(eds) Handbook of Research on Family Business, pp11-24, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Hulsink, W. and Elfring, T. 2001, ‘Much Ado About Nothing? The Role and Contribution of Incubators in Promoting

Entrepreneurship and Fostering New Companies’. RENT XV Research in Entrepreneurship and Small Business, Small Business

Institute, Turku, Finland.

Kets de Vries, M. 1996, Family Business: Human Dilemmas in the Family Firm, International Thomson Business Press, London,

England

McMurray, A.J. 2003, ‘The Relationship Between Organizational Climate and Organizational Culture’, The Journal of

American Academy of Business, Vol 3, No 1, September. Pp 1-8.

McMurray, A.J,, Scott, D. and Pace, R.W. 2004, ‘The Relationship between Organizational commitment and Organizational

Climate in Manufacturing’, Human Resource Development Quarterly, Vol 15, No 4, December, pp. 473-488.

Melin, L. and Nordqvist, M. 2006, ‘The Practice of Strategic Planning in the Context of Family Firms’. Paper to be considered

for presentation at The Crafts of Strategy: Strategic Planning in Defferent Contexts, Toulouse, pp. 22-23 May.

Melin, L. and Nordqvist, M..2007, ‘The Refl exive Dynamics of Institutionalization: The Case of the Family Business, Strategic

Organization, Vol 5, No.3, pp. 321-333.

Mian, S.A., 1997 ‘Assessing and managing the university technology business incubator: an integrative framework’, Journal of

Business Venturing, Vol. 12, pp.251–285.

Naldi, L., Nordqvist, M., Sjoberg, K., Wiklund, J. 2007, ‘Entrepreneurial Orientation, Risk Taking, and Performance in

Family Firms’, Family Business Review, Vol XX, No. 1, pp. 33-47.

NBIA, 2004 http://www.nbia.org/resource_center/what_is/index.php viewed 20/4/04

OECD 1999. Business Incubation- International Case Studies, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development

Publications, Paris, France.

O’Neal, T. 2005, ‘Assessing The Impact Of University Technology Incubator Practices On Client Performance, Unpublished

Dissertation, Orlando: University of Central Florida, USA.

Pacholski, R.I. 1988, ‘Hatching an incubator; obtaining recognition of section 510 (c) 3 status for incubator organisations’, The

tax magazine, Vol. 66, No. 4, pp. 273-283.

Small Enterprise Research 16: 2: 2008

75

Poutziouris, P., Sitorus, S. and Chittenden, F. 2002 ‘The Financial affairs of family companies’, ISNB: 090380-838. Available

from P. Poutziouris, Manchester Business School, Manchester, UK

Rice, M.P. and Matthews, J.M. 1995, ‘Growing new ventures creating new jobs; Principles & practices of successful business

incubation’ Quorum, Westport, Connecticut, USA

Schaper, M. and Volery, T. 2007, Entreprneurship and Small Business: a Pacifi c Rim perspective, (2nd ed) John Wiley & Sons,

Milton, Australia

Schmitt, N.W. and Klimoski, R.J. 1991, Research methods in human management, South western publisher, Cincinnati.

Sharma, P.2004 ‘An Overview of the Field of Family Business Studies: Current Status and Direction for the Future’, Family

Business Review 16 (1): pp. 1-35.

Sherman, H. and Chappell, D.S. 1998, ‘Methodological challenges in evaluating business incubator outcomes’, Economic

Development Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 313–321.

Smilor R.W. and Gill M.D. Jr. 1986, The New Business Incubator: Linking Talent, Technology, Capital, and Know-How, Free

press, NY, USA

Smyrnios, K.X., Romano, C. and Tanewski, G.A. 1997, The Australian & Private Family Business Survey: 1997. Kosmas

Smyrnios, School of Marketing, RMIT University, Australia.

Smyrnios, K.X. and Walker, R.H. 2003, Australian Family and Private Business Survey, Boyd Partners Unlimited, Melbourne,

Australia

Strauss, A.L and Corbin, J.M. 1998, Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, Sage

Publications Inc, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA

Timmons, J.A. and Spinelli, S 2003, New Venture Creation; entrepreneurship for the 21stCentury’, sixth (international) ed.,

McGraw-Hill / Irvin, NY, USA.

TPIA – Technical Parks Incubation Australia </http://www.tpia.org.au> viewed 2005, 2006, last viewed 02/02/08

UK Business Incubation 2007 <http://www.ukbi.co.uk/?sid=104&pgid=105> last viewed, 18/04/08

Van der Sijde, P., Groen, A. and Benthem, J. 2004,‘ Academishc ondernemen aan de Universiteit Twente’. In W. Hulsink, D.

Manuel and E. Stam (eds), ‘Ondernemen in netwerken: nieuwe en groeiende bedrijven in de informatie samenleving’, Koninklijke

Van Gorcum, Assen, The Netherlands.

Westhead, P. and Cowling, M. 1998, ‘Family fi rm research: The need for a methodological rethink’ Entrepreneurship Theory &

Practice Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 31-56.

Wiklund, J. 1999, ‘The Sustainability of the Entrepreneurial Orientation--Performance Relationship’, Entrepreneurship: Theory

and Practice , Vol. 24, No.1 (Fall 1999), pp. 37-48

Witzel, A. 2000, ‘The problem-centered interview’, Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research [On-

line Journal], 27 paragraphs. Available at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/fqs-texte/1-00/1-00witzel-e.htm, Date of

Access: 27/06/07

Exploring business incubation from a family perspective

Copyright of Small Enterprise Research is the property of Small Enterprise Association of Australia & New

Zealand and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the

copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for

individual use.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

big profits from a very dirty business

big profits from a very dirty business

Family Business

#0956 Running a Family Owned Business

Smile and other lessons from 25 years in business

Financial Times Prentice Hall, Executive Briefings, Business Continuity Management How To Protect Y

Calero, Dennis Family Business

Sitesell Make Great Money With This Free Affiliate Program From Home Business Ebook

Escaping from Microsoft’s Protected Mode Internet Explorer

Peter Earnest, Maryann Karinch Business Confidential, Lessons for Corporate Success from Inside the

An%20Analysis%20of%20the%20Data%20Obtained%20from%20Ventilat

Bmw 01 94 Business Mid Radio Owners Manual

Biomass Fired Superheater for more Efficient Electr Generation From WasteIncinerationPlants025bm 422

Overview of Exploration and Production

Bleaching Water Stains from Furniture

Business Language

więcej podobnych podstron