ALUMINA

1

Alumina

1

Al

2

O

3

[1344-28-1]

Al

2

O

3

(MW 101.96)

InChI = 1/2Al.3O/rAl2O3/c3-1-5-2-4

InChIKey = TWNQGVIAIRXVLR-XYRCZMGDAJ

(a mildly acidic, basic, or neutral support for chromatographic

separations; a reagent for catalyzing dehydration, elimination, ad-

dition, condensation, epoxide opening, oxidation, and reduction

reactions)

Alternate Name: γ

-alumina.

Physical Data:

mp 2015

◦

C; bp 2980

◦

C; d 3.97 g cm

−3

.

Solubility:

slightly sol acid and alkaline solution.

Form Supplied in:

fine white powder, widely available in varying

particle size (50–200 m; 70–290 mesh), in acidic (pH 4), basic

(pH 10), and neutral (pH 7) forms.

Drying:

the activity of alumina has been classified by the Brock-

mann scale into five grades. The most active form, grade I, is

obtained by heating alumina to 200

◦

C while passing an inert

gas through the system, or heating to ∼400

◦

C in an open vessel,

followed by cooling in a dessicator. Addition of 3–4% (w/w)

water and mixing for several hours converts grade I alumina to

grade II. Other grades are similarly obtained (grade III, 5–7%;

grade IV, 9–11%; grade V, 15–19% water).

2,3

Handling, Storage, and Precautions:

inhalation of fine mesh alu-

mina can cause respiratory difficulties. Alumina is best handled

under a fume hood and stored under dry, inert conditions.

Introduction. Alumina is one of the most widely used packing

materials for adsorption chromatography and is available in acidic,

basic, and neutral forms. Use of the correct type is important to

avoid unwanted reactions of the substrate being purified.

1,3

Pos-

sessing both Lewis acidic and basic sites, alumina has been found

to catalyze a wide range of reactions, generally under conditions

that are milder and more selective than comparable homogeneous

reactions.

1

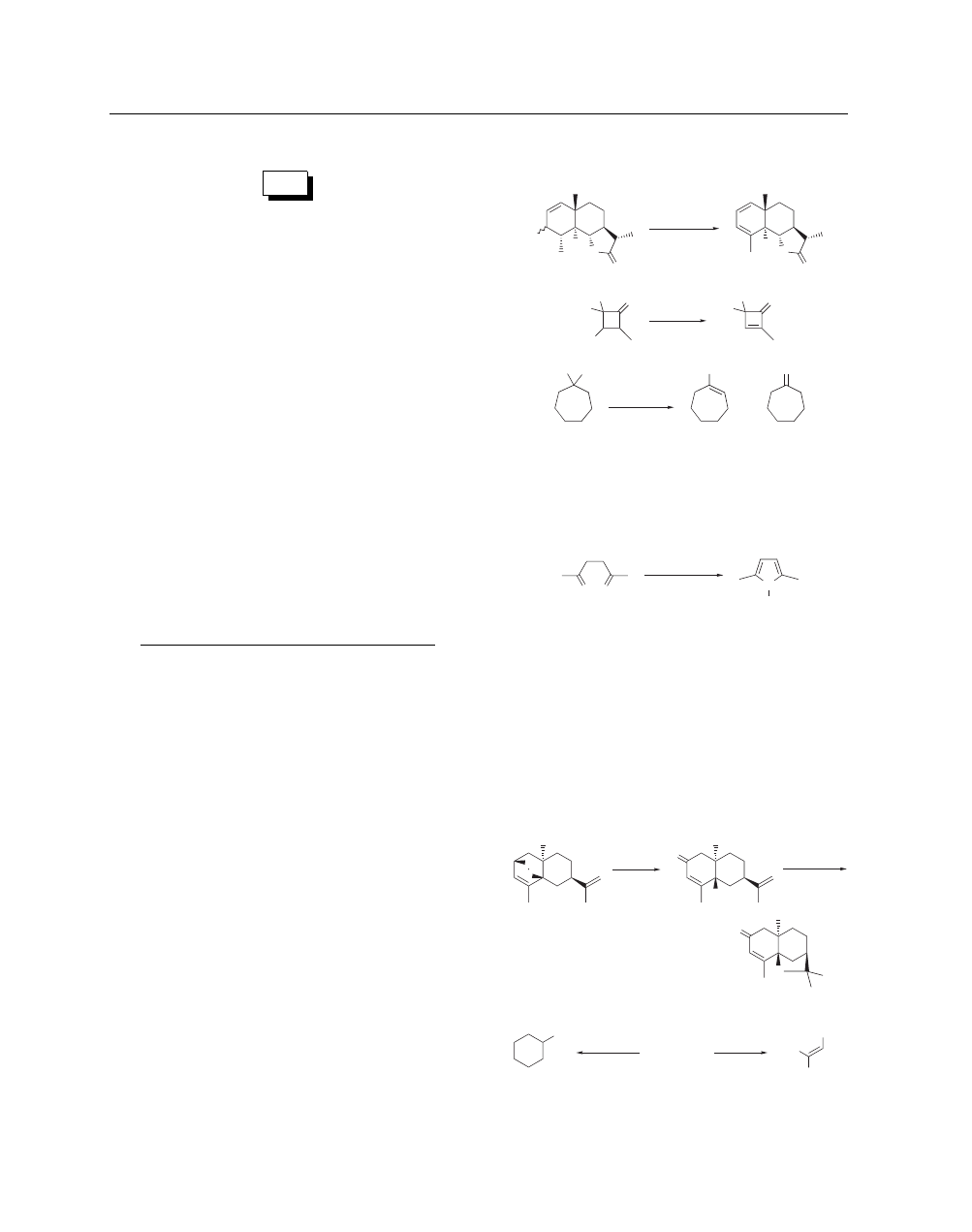

Dehydration and Eliminations. One of the earliest uses of

alumina as a catalyst was for the dehydration of alcohols.

4,5

These

reactions generally require high temperature and yield primarily

non-Saytzeff products. Complex terpenes have been dehydrated

with Pyridine or Quinoline doped alumina (eq 1).

6b

Numerous

other groups can be eliminated in the presence of alumina, in-

cluding OR, OAc, O

3

SR, O

2

SR, and halides.

1,7

Some of these

eliminations proceed under mild conditions,

1

often during chro-

matographic purification (eq 2).

7d

Sulfonates can be eliminated

in the presence of acid and base sensitive groups, without skele-

tal rearrangements. However, a large excess of properly acti-

vated alumina is required, and poor stereo- and regiocontrol are

observed.

7e

Dehydrohalogenations, particularly dehydrofluorina-

tions, occur readily over alumina (eq 3).

8

Stereoselective syn-

theses of vinyl halides have been developed that take advantage

of desilicohalogenation

9

or deborohalogenation

10

of vinylsilane

or vinylboronic acid derived dihalides. Benzol[c]thiophene has

been synthesized by dehydration of a sulfoxide precursor.

11

The

oxidation of selenides to selenoxides and their elimination to

alkenes can be accomplished in one step using basic alumina and

tert-Butyl Hydroperoxide in THF.

12

O

HO

H

(1)

O

O

H

O

alumina

pyridine

220–230 °C

44%

(2)

O

EtO

alumina

activity I

65–80%

O

Ph

Ph

Ph

Ph

(3)

alumina

CCl

4

, 25 °C

24 h

O

F

F

F

+

60%

<4%

Alumina has been used for various dehydration reactions,

including those leading to piperidines,

13

pyrroles (eq 4) and

pyrazoles,

14

and other heterocycles.

15

It is also an effective cat-

alyst for the selective protection of aldehydes in the presence of

ketones.

16

(4)

EtNH

2

, alumina

0 to 20 °C

96%

O O

N

Et

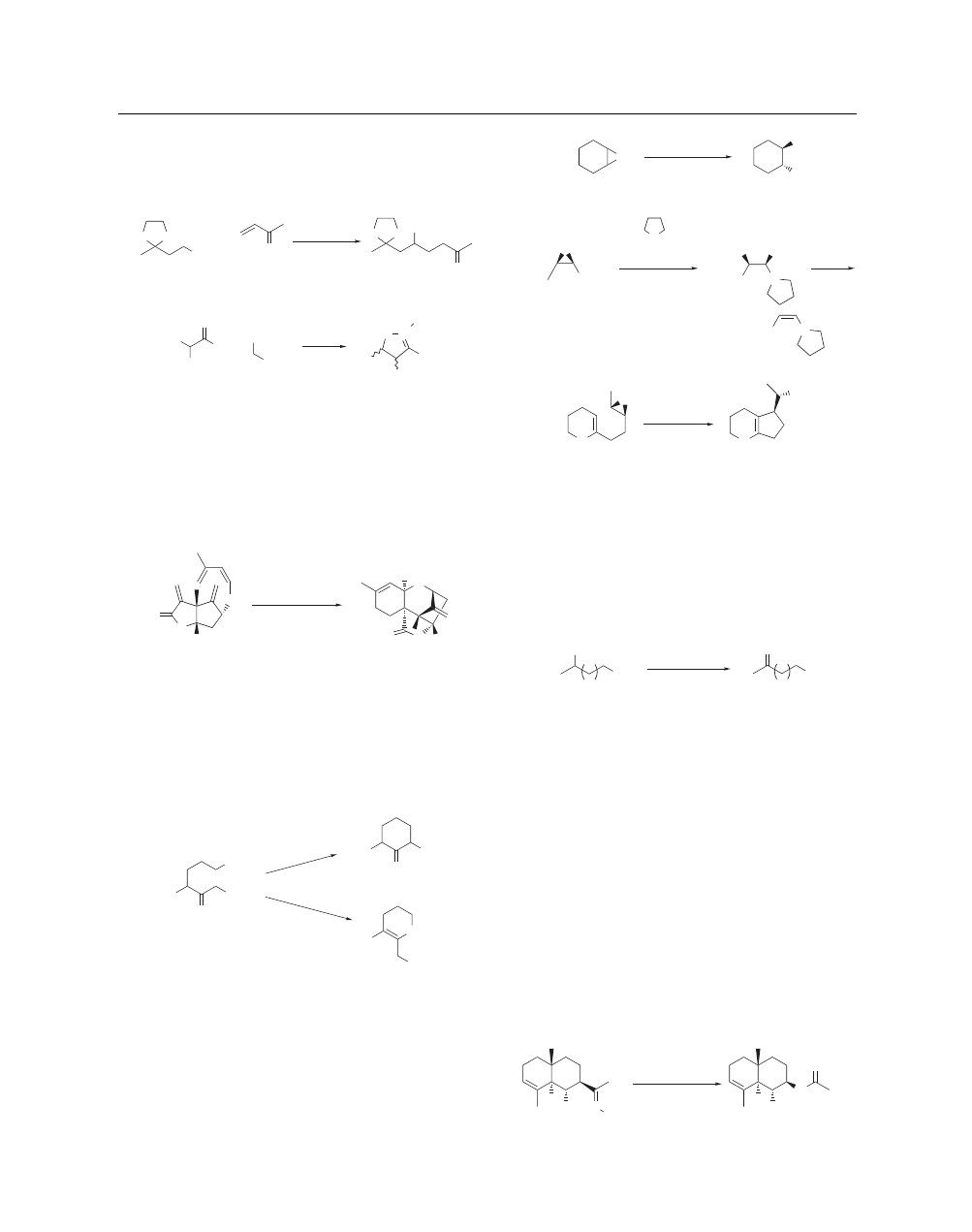

Addition and Condensation Reactions.

Alumina pro-

motes the addition of various heteroatom species, whether by

electrophilic or nucleophilic processes. In contrast to the elimi-

nation reactions described earlier, alumina also promotes the in-

tramolecular addition of OH and OR groups to isolated (eq 5)

6c

and carbonyl-activated alkenes.

17

It is also reported to catalyze

the conjugate addition of other nucleophiles, such as amines.

18

In

the presence of alumina, Iodine can be used to iodinate aromat-

ics, hydroiodinate alkenes, and diiodinate alkynes (eq 6).

19

Hy-

drochlorinations and hydrobrominations of alkenes and alkynes

give the Markovnikov products, with good stereoselectivity.

20

O

O

(5)

O

OH

O

O

basic

alumina

84%

acidic

alumina

PhH, 75 °C

72%

(6)

I

2

activated

alumina

cyclohexene

pet ether

35 °C, 2 h

85%

1-hexyne

pet ether

rt, 4 h

92%

I

Bu

I

I

Aldol-type condensations between aldehydes and various ac-

tive methylene compounds,

21

Michael reactions (eq 7),

22

as well

Avoid Skin Contact with All Reagents

2

ALUMINA

as Wittig-type reactions

23

can be carried out on alumina under

mild conditions, often without a solvent. An interesting nitroaldol

reaction–cyclization sequence gives 2-isoxazoline 2-oxides with

good diastereoselectivity (eq 8).

24

NO

2

O

O

O

O

O

NO

2

O

(7)

+

basic alumina

rt, 5–8 h

88%

(8)

H

O

Br

Ph

NO

2

CO

2

Et

O N

+

O

–

OH

Ph

CO

2

Et

+

Al

2

O

3

24 h

62%

trans

:cis = 9:1

Orbital symmetry controlled reactions that have been promoted

by alumina include the Diels–Alder,

25

the ene,

26

and the Carroll

rearrangement.

27

These reactions proceeded under milder condi-

tions and with greater stereoselectivity. In a spectacular exam-

ple, chromatographic purification promoted a diastereoselective

intramolecular Diels–Alder that produced the verrucarol skeleton

(eq 9).

25b

O

O

H

O

O

H

O

O

H

(9)

neutral alumina (I)

column, rt

83%

Alkylation reactions that have been induced by alumina in-

clude per-C-methylation of phenol,

28

intramolecular alkylation

to yield a spiro-fused cyclopropane,

29

and S-

30

and O-alkylations

(eq 10).

31

The activation of Diazomethane by alumina has pro-

vided methods for the conversion of ketones to epoxides

32

and

for the selective monomethylation of dicarboxylic acids.

33

Basic

alumina has been used for the generation and trapping of

dichlorocarbene.

34

SO

2

Ph

Br

Ph

O

O

Ph

SO

2

Ph

Ph

O

SO

2

Ph

(10)

LDA

glyme

90%

neutral alumina

toluene

rt

95%

Epoxides.

Epoxides can be opened under mild, selective

conditions using alumina impregnated with a variety of nucle-

ophiles, such as alcohols, thiols, selenols, amines, carboxylic acids

(eq 11),

35

and peroxides.

36

Use is made of this process in a route to

(Z)-enamines (eq 12).

37

Formation of C–C bonds by intramolec-

ular opening of epoxides has been reported (eq 13),

38

as have

alumina catalyzed epoxide formations

23,39

and rearrangements.

40

(11)

O

OH

XR

4% RXH

neutral alumina

Et

2

O, 25 °C, 1 h

RX = MeO, 66%; PhS, 70%, PhSe, 95%; n-BuNH, 73%

n

-Hex

SiMe

3

O

N

N

n

-Hex

n

-Hex

SiMe

3

HO

(12)

neutral alumina

85 °C, 4 d

63%

N

H

KH

THF, rt

(13)

O

O

O

1. basic

alumina (I)

hexanes

rt, 24 h

2. Ac

2

O, py

90–100%

OAc

Oxidations and Reductions. Posner has shown that Oppe-

nauer oxidations, with Cl

3

CCHO or PhCHO as the hydrogen

acceptors, are greatly accelerated in the presence of activated

alumina.

41

Secondary alcohols are oxidized selectively over pri-

mary alcohols (eq 14) and groups susceptible to other oxidants

(sulfides, selenides, and alkenes) are unaffected. Even cyclobu-

tanol, which is prone to fragmentation with one-electron oxidants,

can be oxidized to cyclobutanone in 92% yield.

8

OH

OH

OH

O

(14)

8

2 equiv PhCHO

alumina

25 °C, 24 h

65%

The

complementary

reduction

reaction

(Meerwein–

Ponndorf–Verley), using isopropanol as the hydride donor,

is also facilitated by alumina and allows the selective reduction

of aldehydes over ketones.

42

Functional groups that survive these

conditions include alkene, nitro, ester, amide, nitrile, primary and

secondary iodides, and benzylic bromide.

Air oxidation of a fluoren-9-ol to the fluoren-9-one and thiols

to disulfides are accelerated on the alumina surface.

43

Alumina

has also been used as a solid support for a variety of inorganic

reagents,

44

and for immobilizing chiral catalysts.

45

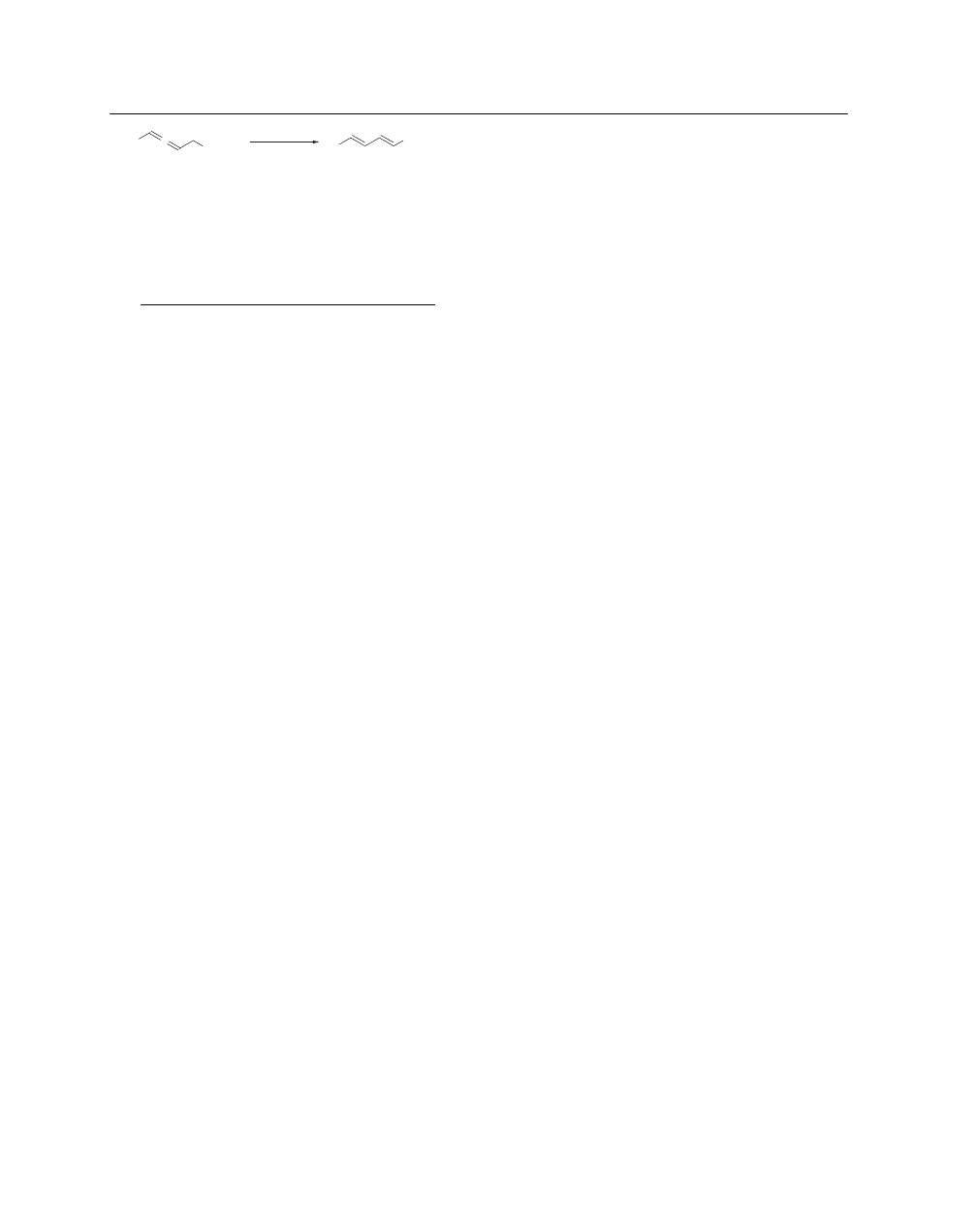

Miscellaneous Reactions.

Many rearrangements are cat-

alyzed by alumina.

1

The Beckmann rearrangement

46

of the O-

sulfonyloxime shown gives the expected amide with activated

alumina, and the corresponding oxazoline with basic alumina

(eq 15).

46d

Alumina has long been used for isomerization of β,γ-

unsaturated ketones to the conjugated ketones.

47

Isomerizations

of alkynes to allenes,

48

and allenes to conjugated dienoates

49

have

also been reported (eq 16).

N

H

OH

N

H

H

OH

O

(15)

OSO

2

Ar

activated alumina

80%

A list of General Abbreviations appears on the front Endpapers

ALUMINA

3

CO

2

Me

Et

•

(16)

alumina

PhH, reflux, 5 h

82%

Et

CO

2

Me

Alumina promotes the hydrolysis of acetates of primary

alcohols,

50

the deacylation of imides,

51

the hydrolysis of

sulfonylimines,

52

and the decarbalkoxylation of β-keto esters and

carbamates.

53

It can also be used for acylations and esterifica-

tions, with high selectivity for primary alcohols over secondary

alcohols.

54

1.

Posner, G. H. , Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1978, 17, 487.

2.

Perrin, D. D.; Armarego, W. L. F. Purification of Laboratory Chemicals;

Pergamon: New York, 1988; pp 20, 310.

3.

(a) Furniss, B. S.; Hannaford, A. J.; Smith, P. W. G.; Tatchell, A. R.

Vogel’s Textbook of Practical Organic Chemistry

; Longman-Wiley:New

York, 1989; p 212. (b) Fieser & Fieser 1967, 1, 19.

4.

Knözingery, H., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1968, 7, 791.

5.

(a) Hershberg, E. B.; Ruhoff, J. R., Org. Synth. 1937, 17, 25. (b) Newton,

L. W.; Coburn, E. R., Org. Synth., Coll. Vol. 1955, 3, 312. (c) Sawyer,

R. L.; Andrus, D. W., Org. Synth., Coll. Vol. 1955, 3, 276.

6.

(a) von Rudloff, E., Can. J. Chem. 1961, 39, 1860. (b) Corey, E. J.;

Hortmann, A. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 5736. (c) Barrett, H. C.;

Büchi, G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967, 89, 5665.

7.

(a) Kobayashi, S.; Shinya, M.; Taniguchi, H. , Tetrahedron 1971, 71.

(b) Ishii, H.; Tozyo, T.; Nakamura, M.; Funke, E., Chem. Pharm. Bull.

1972, 20, 203. (c) Gotthardt, H.; Hammond, G. S., Chem. Ber. 1974,

107

, 3922. (d) Mayr, H.; Huisgen, R., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl.

1975, 14, 499. (e) Posner, G. H.; Gurria, G. M.; Babiak, K. A., J. Org.

Chem. 1977

, 42, 3173. (f) Vidal, J.; Huet, F., Tetrahedron 1986, 27,

3733.

8.

(a) Strobach, D. R.; Boswell, G. A., Jr., J. Org. Chem. 1971, 36, 818. (b)

Boswell, G. A., Jr., J. Org. Chem. 1966, 31, 991.

9.

(a) Miller, R. B.; McGarvey, G., J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 4424. (b) Miller,

R. B.; McGarvey, G., Synth. Commun. 1977, 7, 475.

10.

Sponholtz, W. R., III; Pagni, R. M.; Kabalka, G. W.; Green, J. F.; Tan,

L. C., J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 5700.

11.

Cava, M. P.; Pollack, N. M.; Mamer, O. A.; Mitchell, M. J., J. Org. Chem.

1971, 36, 3932.

12.

Labar, D.; Hevesi, L.; Dumont, W.; Krief, A., Tetrahedron 1978, 1141.

13.

(a) Bourns, A. N.; Embleton, H. W.; Hansuld, M. K., Org. Synth., Coll.

Vol. 1963

, 4, 795. (b) Glacet, C.; Adrian, G., C.R. Hebd. Seances Acad.

Sci., Ser. C 1969

, 269, 1322.

14.

(a) Texier-Boullet, F.; Klein, B.; Hamelin, J., Synthesis 1986, 409.

(b) Tolstikov, G. A.; Galin, F. Z.; Makaev, F. Z., Zh. Org. Khim. 1989,

25

, 875.

15.

(a) LeBlanc, R. J.; Vaughan, K., Can. J. Chem. 1972, 50, 2544.

(b) Higashino, T.; Suzuki, K.; Hayashi, E., Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1978,

26

, 3485. (c) Bladé-Font, A., Tetrahedron 1980, 21, 2443. (d) Hooper,

D. L.; Manning, H. W.; LaFrance, R. J.; Vaughan, K., Can. J. Chem.

1986, 65, 250. (e) Hull, J. W., Jr.; Otterson, K.; Rhubright, D., J. Org.

Chem. 1993

, 58, 520.

16.

Kamitori, Y.; Hojo, M.; Masuda, R.; Yoshida, T., Tetrahedron 1985, 26,

4767.

17.

McPhail, A. T.; Onan, K. D., Tetrahedron 1973, 4641.

18.

(a) Pelletier, S. W.; Venkov, A. P.; Finer-Moore, J.; Mody, N. V.,

Tetrahedron 1980

, 21, 809. (b) Pelletier, S. W.; Gebeyehu, G.; Mody, N.

V., Heterocycles 1982, 19, 235. (c) Dzurilla, M.; Kutschy, P.; Kristian,

P., Synthesis 1985, 933.

19.

Pagni, R.; Kabalka, G. W.; Boothe, R.; Gaetano, K.; Stewart, L. J.;

Conaway, R.; Dial, C.; Gray, D.; Larson, S.; Luidhardt, T., J. Org. Chem.

1988, 53, 4477.

20.

Kropp, P. J.; Daus, K. A.; Tubergen, M. W.; Kepler, K. D.; Wilson,

V. P.; Craig, S. L.; Baillargeon, M. M.; Breton, G. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc.

1993, 115, 3071, and references cited therein.Addition of HN

3

:Breton,

G. W.; Daus, K. A.; Kropp, P. J., J. Org. Chem. 1992, 57, 6646.

21.

(a) Rosan, A.; Rosenblum, M., J. Org. Chem. 1975, 40, 3621. (b) Texier-

Boullet, F.; Foucaud, A., Tetrahedron 1982, 23, 4927. (c) Rosini, G.;

Ballini, R.; Sorrenti, P., Synthesis 1983, 1014. (d) Varma, R. S.; Kabalka,

G. W.; Evans, L. T.; Pagni, R. M., Synth. Commun. 1985, 15, 279. (e)

Nesi, R.; Stefano, C.; Piero, S.-F., Heterocycles 1985, 23, 1465. (f)

Rosini, G.; Ballini, R.; Petrini, M.; Sorrenti, P., Synthesis 1985, 515.

(g) Foucaud, A.; Bakouetila, M., Synthesis 1987, 854. (h) Moison, H.;

Texier-Boullet, F.; Foucaud, A., Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 537.

22.

(a) Rosini, G.; Marotta, E.; Ballini, R.; Petrini, M., Synthesis 1986, 237.

(b) Ballini, R.; Petrini, M.; Marcantoni, E.; Rosini, G., Synthesis 1988,

231.

23.

Texier-Boullet, F.; Villemin, D.; Ricard, M.; Moison, H.; Foucaud, A.,

Tetrahedron 1985

, 41, 1259.

24.

Isoxazoline:Rosini, G.; Galarini, R.; Marotta, E.; Righi, P., J. Org. Chem.

1990, 55, 781.Rosini, G.; Marotta, E.; Righi, E.; Seerden, J. P., J. Org.

Chem. 1991

, 56, 6258.

25.

(a) Parlar, H.; Baumann, R., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1981, 20, 1014

(b) Koreeda, M.; Ricca, D. J.; Luengo, J. I., J. Org. Chem. 1988, 53,

5586.

26.

(a) Tietze, L. F.; Beifuss, U.; Ruther, M., J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 3120.

(b) Tietze, L. F.; Beifuss, U., Synthesis 1988, 359.

27.

Pogrebnoi, S. I.; Kalyan, Y. B.; Krimer, M. Z.; Smit, W. A., Tetrahedron

1987, 28, 4893.

28.

Cullinane, N. M.; Chard, S. J.; Dawkins, C. W. C., Org. Synth., Coll. Vol

1963, 4, 520.

29.

Baird, R.; Winstein, S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 567.

30.

Villemin, D., J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1985, 870.

31.

(a) Ogawa, H.; Chihara, T.; Teratani, S.; Taya, K., Bull. Chem. Soc.

Jpn. 1986

, 59, 2481. (b) Cooke, F.; Magnus, P., J. Chem. Soc., Chem.

Commun. 1976

, 519.

32.

Hart, P. A.; Sandmann, R. A., Tetrahedron 1969, 305.

33.

Ogawa, H.; Chihara, T.; Taya, K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 1365.

34.

Sarratosa, F., J. Chem. Educ. 1964, 41, 564.

35.

(a) Posner, G. H.; Rogers, D. Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 8208.

(b) Posner, G. H.; Rogers, D. Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 8214. (c)

Evans, D. A.; Golob, A. M.; Mandel, N. S.; Mandel, G. S., J. Am. Chem.

Soc. 1978

, 100, 8170.

36.

Kropf, H.; Amirabadi, H. M.; Mosebach, M.; Torkler, A.; von Wallis,

H., Synthesis 1983, 587.

37.

Hudrlik, P. F.; Hudrlik, A. M.; Kulkarni, A. K., Tetrahedron 1985, 26,

139.

38.

(a) Boeckman, R. K., Jr.; Bruza, K. J.; Heinrich, G. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc.

1978, 100, 7101. (b) Niwa, M.; Iguchi, M.; Yamamura, S., Tetrahedron

1979, 4291.

39.

(a) Dhillon, R. S.; Chhabra, B. R.; Wadia, M. S.; Kalsi, P. S., Tetrahedron

1974, 401. (b) Antonioletti, R.; D’Auria, M.; De Mico, A.; Piancatelli,

G.; Scettri, A., Tetrahedron 1983, 39, 1765.

40.

(a) Tsuboi, S.; Furutani, H.; Takeda, A., Synthesis 1987, 292. (b)

Harigaya, Y.; Yotsumoto, K.; Takamatsu, S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Onda, M.,

Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1981

, 29, 2557.

41.

(a) Posner, G. H.; Perfetti, R. B.; Runquist, A. W., Tetrahedron 1976,

3499. (b) Posner, G. H.; Chapdelaine, M. J., Synthesis 1977, 555. (c)

Posner, G. H.; Chapdelaine, M. J., Tetrahedron 1977, 3227.

42.

Posner, G. H.; Runquist, A. W.; Chapdelaine, M. J., J. Org. Chem.

1977, 42, 1202.Also see:Suginome, H.; Kato, K., Tetrahedron 1973,

4143.

43.

(a) Pan, H.-L.; Cole, C.-A.; Fletcher, T. L., Synthesis 1975, 716. (b) Liu,

K.-T.; Tong, Y.-C., Synthesis 1978, 669.

44.

Review:Laszlo, P., Comprehensive Organic Synthesis 1991, 7, 839.

Recent examples: (a) Singh, S.; Dev, S., Tetrahedron 1993, 49, 10959.

Avoid Skin Contact with All Reagents

4

ALUMINA

(b) Lee, D. G.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z., J. Org. Chem. 1993, 58, 2918.

(c) Morimoto, T.; Hirano, M.; Iwasaki, K.; Ishikawa, T., Chem. Lett.

1994, 53. (d) Santaniello, E.; Ponti, F.; Manzocchi, A., Synthesis 1978,

891.

45.

Soai, K.; Watanabe, M.; Yamamoto, A., J. Org. Chem. 1990, 55, 4832.

46.

(a) Craig, J. C.; Naik, A. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962, 84, 3410. (b)

Gonzalez, A.; Galvez, C., Synthesis 1982, 946. (c) Luh, T.-Y.; Chow,

H.-F.; Leung, W. Y.; Tam, S. W., Tetrahedron 1985, 41, 519. (d) Nagano,

H.; Masunaga, Y.; Matsuo, Y.; Shiota, M., Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1987,

60

, 707.See also: (e) Métayer, A.; Barbier, M., Bull. Soc. Chem. Fr. 1972,

3625.

47.

(a) Marshall, J. A.; Roebke, H., J. Org. Chem. 1966, 31, 3109. (b)

Hudlicky, T.; Srnak, T., Tetrahedron 1981, 22, 3351. (c) Reetz, M. T.;

Wenderoth, B.; Urz, R., Chem. Ber. 1985, 118, 348. (d) Hatzigrigoriou,

E.; Schmitt, M.-C.; Wartski, L., Tetrahedron 1988, 44, 4457. Also see: (e)

Scettri, A.; Piancatelli, G.; D’Auria, M.; David, G., Tetrahedron 1979,

35

, 135.

48.

(a) Larock, R. C.; Chow, M.-S.; Smith, S. J., J. Org. Chem. 1986, 51,

2623. (b) Manning, D. T.; Coleman, H. A. J., J. Org. Chem. 1969, 34,

3248.

49.

Tsuboi, S.; Matsuda, T.; Mimura, S.; Takeda, A., Org. Synth., Coll. Vol

1993, 8, 251.

50.

Johns, W. F.; Jerina, D. M., J. Org. Chem. 1963, 28, 2922.

51.

Boar, R. B.; McGhie, J. F.; Robinson, M.; Barton, D. H. R.; Horwell,

D. C.; Stick, R. V., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1 1975, 1237.

52.

Coutts, I. G. C.; Culbert, N. J.; Edward, M.; Hadfield, J. A.; Musto,

D. R.; Pavlidis, V. H.; Richards, D. J., J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1

1985, 1829.

53.

(a) Greene, A. E.; Cruz, A.; Crabbé, P. , Tetrahedron 1976, 2707.

(b) van Leusen, A. M.; Strating, J., Org. Synth., Coll. Vol 1988, 6,

981.

54.

(a) Posner, G. H.; Oda, M., Tetrahedron 1981, 22, 5003. (b) Rana,

S. S.; Barlow, J. J.; Matta, K. L., Tetrahedron 1981, 22, 5007. (c) Posner,

G. A.; Okada, S. S.; Babiak, K. A.; Miura, K.; Rose, R. K., Synthesis

1981, 789. (d) Nagasawa, K.; Yoshitake, S.; Amiya, T.; Ito, K., Synth.

Commun. 1990

, 20, 2033.

Viresh H. Rawal, Seiji Iwasa, Alan S. Florjancic, & Agnes Fabre

The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA

A list of General Abbreviations appears on the front Endpapers

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

aluminum eros ra075

potassium on alumina eros rp192

aluminum chloride eros ra079

aluminium ethoxide eros ra081

aluminium amalgam eros ra076

aluminium isopropoxide eros ra084

Aluminum i miedź Mateusz Bednarski

benzyl chloride eros rb050

hydrobromic acid eros rh031

chloroform eros rc105

magnesium eros rm001

więcej podobnych podstron