Pathophysiology of the

liver

Mechanisms of cholestasis

Stasis of bile flow may result from three processes:

a) failure to secrete bile into the canaliculi, due to injury to

hepatocytes and/or the canalicular membrane or altered

function of the canalicular bile salt transporter;

b) increased permeability of the canaliculi, cholangiocytes

and/or their tight junctions; and

c) mechanical obstruction of the biliary tree at any level.

Diffuse injury to canalicular membranes causes loss of

microvilli in dilated canaliculi which can be plugged by

inspissated bile. There is impaired secretion of all

components of bile.

Classification of cholestasis

1. Canalicular Cholestasis

a. In drug-induced cholestasis, (phenothiazines, sulfonylureas)

b. In steroid- induced cholestasis (normal pregnancy, or treatment with

synthetic estrogens, or with 17-a-alkyl anabolic steroids),

c. Postoperative cholestasis.

d. Other causes of canalicular cholestasis (severe infections with

endotoxemia and/or septicaemia, total parenteral nutrition, and sickle cell

anaemia crises).

2. Obstructive cholestasis

a. Obstructive intrahepatic cholestasis (primary biliary cirrhosis, sclerosing

cholangitis and intrahepatic lithiasis; granulomas, lymphomas, metastatic

nodules obstructing interlobular and larger intrahepatic bile ducts).

b. Obstructive extrahepatic cholestasis is most often caused by local lesions

such as carcinoma of the pancreas, or by common bile duct stones or

structures.

HYPERBILIRUBINEMIA

• Hyperbilirubinemia is defined as a total bilirubin level greater

than 1.5 mg/dL, an unconjugated level greater than 1 mg/dL,

or a conjugated bilirubin level greater than 0.3 mg/dL.

• The causes of hyperbilirubinemia can be divided into

problems of excess production and abnormal clearance. The

concentration of bilirubin in plasma is directly related to the

production rate of bilirubin and inversely related to hepatic

and renal removal rates.

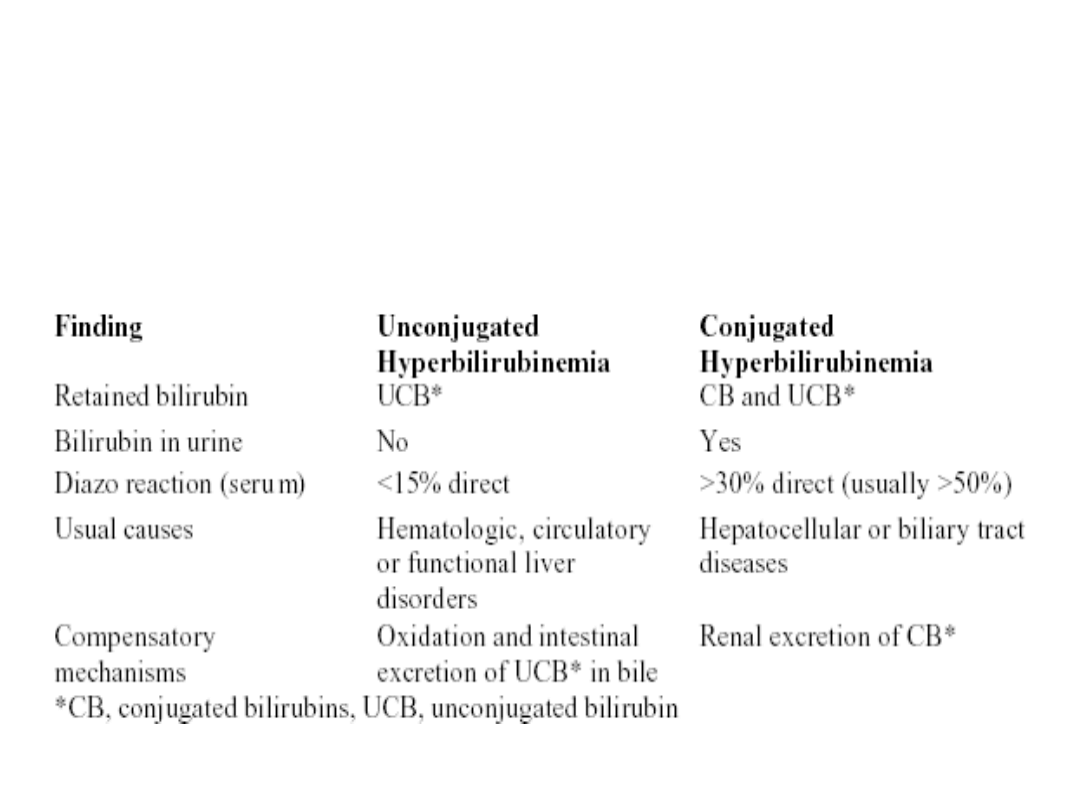

• In general, hyperbilirubinemia is separated into conjugated

and unconjugated bilirubin excess.

• This distinction is particularly helpful at low bilirubin

concentrations and assists in determining which set of

differential diagnoses should be sought.

Unconjugated versus Conjugated

Hyperbilirubinemia

1. Pathophysiology of Unconjugated

Hyperbilirubinemia

• Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, characterized by

retention exclusively of UCB in the serum, without

bilirubinuria, results from insufficient hepatic

clearance and/or conjugation of the load of the UCB

produced each day, and is subclassified according

to the step(s) in bilirubin metabolism that are

deranged.

• The most common aetiologies are:

overproduction of unconjugated bilirubin due to disorders

of red blood cells;

impaired delivery of unconjugated bilirubin due to

disturbances in hepatic circulation; and

functional or hereditary defects in uptake, storage, or

conjugation of bilirubin.

Pathophysiology of Unconjugated

Hyperbilirubinemia continued

a. Overproduction of bilirubin due to accelerated heme catabolism is a very

common cause of unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and often augments

jaundice of other causes. Most often caused by hemolytic anemias. Diagnosis

rests mainly on hematological studies.

b. Decreased delivery of bilirubin and other substances in plasma to the liver

cells is the most common form of unconjugated jaundice. It is most often due

to right-sided congestive heart failure and clears as the heart failure is

controlled. Another major cause is portosystemic shunting, due to either

cirrhosis or surgical anastomosis, which diverts the bilirubin formed in the

spleen past the liver directly into the systemic circulation.

c&d. Diminished clearance (uptake and storage) of UCB is often due to

competitive inhibition of these processes by drugs (e.g., rifampicin). The

jaundice usually resolves within 2-3 days after the drug is discontinued.

Hypothyroidism and febrile illnesses may impair hepatic storage capacity for

UCB. Impaired uptake of UCB and other organic anions is also present in most

patients with the hereditary disorder of conjugation, Gilbert's syndrome.

e. Impaired conjugation of bilirubin is usually due to hereditary defects, since

the activity of UGT1A1 is preserved in hepatobiliary diseases, except in end-

stage cirrhosis or acute hepatic failure.

Hereditary autosomal recessive

disorders of UCB conjugation

Gilbert's syndrome is characterized by a chronic, mild, fluctuating

unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, caused by a polymorphism in the

promoter of both gene alleles encoding UGT1A1. This very common

hereditary defect leads to a 70-80% decrease in the expression

and activity of UGT1A1. This, by itself, does not cause

hyperbilirubinemia unless combined with overproduction and/or

impaired uptake of bilirubin. Bilirubin production and/or clearance

are further (reversibly) altered during fasting and stress, often

unmasking or augmenting the severity of jaundice.

The Crigler-Najjar syndromes are two more severe, rare, hereditary,

recessive deficiencies of UGT1A1.

In Type I, there is no detectable activity of UGT1A1 in the liver, and

glucuronide conjugation of many drugs may be impaired also.

Jaundice is severe from the neonatal period, and bilirubin

encephalopathy is the rule if the patients are untreated.

In Type II, UGT1A1 activity is detectable but at less than 10% of

normal levels. Jaundice begins usually in late childhood, is less

severe, and seldom causes bilirubin encephalopathy.

2. Pathophysiology of Conjugated

Hyperbilirubinemia

Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is characterized by retention principally of

conjugated bilirubin in the serum.

Plasma UCB concentrations are elevated also, due in part to hydrolysis of retained

conjugated bilirubins by tissue ß-glucuronidases, as well as by contributions

from associated haemolysis and/or impairment of delivery, uptake, and storage

of UCB.

Conjugated hyperbilirubinemia results from impairment of the canalicular secretion

or biliary flow of conjugated bilirubins. Other organic anions, which share the

same transport system as conjugated bilirubin, are also excreted poorly.

The retained conjugated bilirubins regurgitate through the hepatocytes,

cholangiocytes and their weakened tight junctions into the space of Disse and

thence via the lymph to the plasma.

The small fraction of retained conjugated bilirubins that is not bound to plasma

albumin filters at the glomerulus, producing bilirubinuria; this is not only

diagnostic of conjugated hyperbilirubinemia, but also constitutes the major

alternate pathway for excretion of conjugated bilirubin and other organic anions

in the face of reduced hepatobiliary excretion.

2. Pathophysiology of Conjugated

Hyperbilirubinemia continued

• In contrast to unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia, jaundice with bilirubinuria

almost always results from significant hepatobiliary disease, and is

classified further according to whether canalicular secretion or biliary flow

is primarily impaired.

• Specific defects in canalicular secretion of bilirubin conjugates and other

organic anions secreted by MRP2 are characteristic of the hereditary

Dubin-Johnson and Rotor's syndromes, and common in hepatocellular

diseases.

• Generalized defects in canalicular secretion, or biliary flow, produce

cholestasis, in which there is also marked retention of bile salts.

• In all cases, the canalicular transporters, BSEP and MRP2, are dislocated

into subapical vesicles where they can no longer export bile salts and other

organic anions into bile.

• Dislocation of alkaline phosphatase to the basolateral membrane leads to

regurgitation of this enzyme into the space of Disse and thence to plasma.

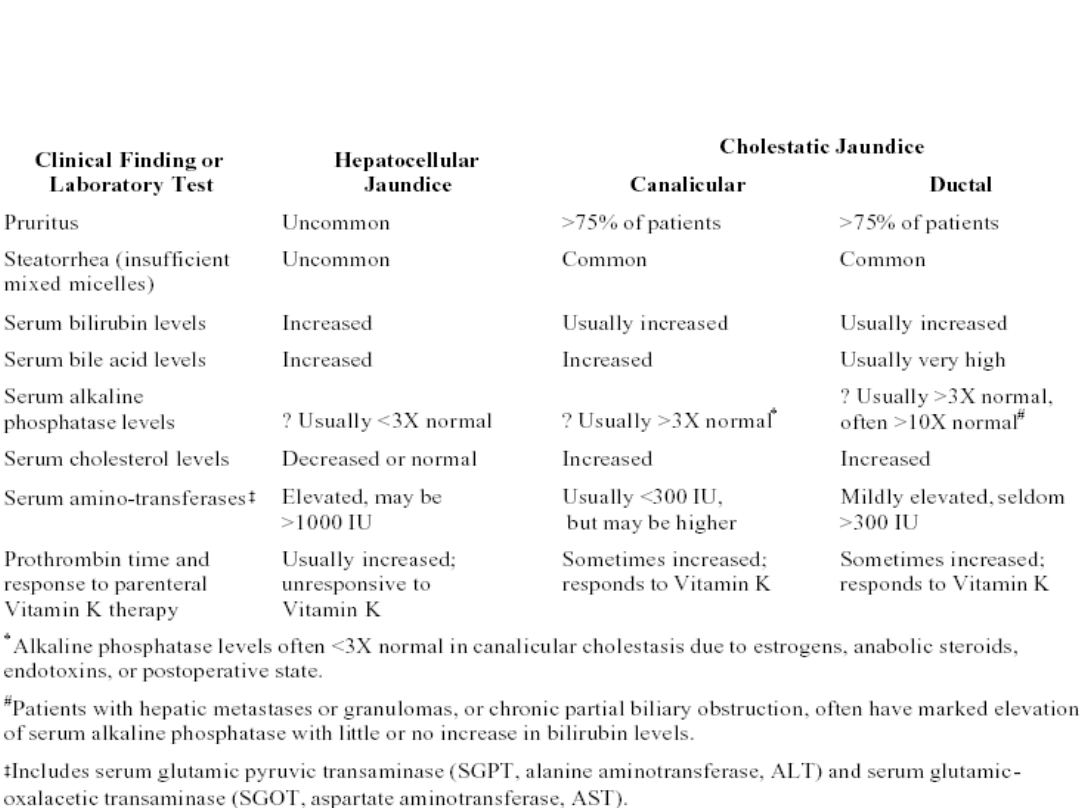

Differential Diagnosis of Conjugated

Hyperbilirubinemia –

Hepatocellular versus Cholestatic Jaundice

Effects of hyperbilirubinemia

• Kernicterus in infants

• Renal failure

• Increased postoperative mortality and morbidity

• Decreased cardiovascular response to vasopressors

• Decreased adsorption of fat-soluble vitamins

• Pigmented gallstones

Effects of cholestasis

• Impaired transport of bile salts, organic anions, and bile

components (e.g., lipids, bilirubin)

• Pruritus

• Decreased amounts of bile acids in the intestinal lumen

Decreased absorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K)

Decreased calcium absorption

Osteoporosis

Coagulopathy

Steatorrhea

• Decreased secretion cholesterol into bile

Hypercholesterolemia, increased lipoprotein X

Xanthomas, increased phospholipids

Altered erythrocyte membrane with hemolysis

• Stimulation of secretion or synthesis of

Alkaline phosphatase

5´-Nucleotidase

gGlutamyltransferase

Cirrhosis of the Liver

• Cirrhosis of the liver is defined, pathologically, as

widely distributed, irregular hepatic fibrosis with

distortion of the lobular architecture and vasculature,

resulting from persistent inflammation and/or

parenchymal cell necrosis, combined with nodular

regeneration.

• Cirrhosis always has three basic features:

a) destruction of liver cells;

b) replacement of groups of lobules, entire lobules, or

parts of lobules with fibrous tissue;

c) nodular regeneration of the residual hepatic

parenchyma.

Cirrhosis of the Liver

• Cirrhosis is usually progressive, at a tempo which

may be variable and intermittent.

• In the earlier stages, this is due to persistent or

repeated damage to liver cells from the causative

agent, but resorption of fibrous tissue and

regeneration of hepatocytes may repair the

damage and reverse the process if the offending

agent is treated or removed.

• By contrast, in late stages of cirrhosis, the

secondary distortion of the hepatic circulation may

lead to chronic ischemia, with increasing fibrosis,

continued cell loss and eventually liver failure.

Clinical Consequences of Cirrhosis 1

a. Diminished hepatocytic synthetic capacity leads

to hypoalbuminemia, deficiency of clotting factors,

and (usually) hypocholesterolemia (except with

chronic cholestasis).

b. Impaired oestrogen metabolism causes palmar

erythema (red palms), spider angiomata,

amenorrhea in females, complicated by alcohol-

induced testicular atrophy and feminization in males.

c. Impaired detoxification/excretory function,

combined with shunting of blood around the liver,

causes jaundice, encephalopathy, and excessive

responses to administered drugs.

Clinical Consequences of Cirrhosis

2

d. Altered metabolism of vasoactive substances leads to

splanchnic vasodilatation, activation of the renin-

angiotensin-catecholamine system, sodium retention,

ascites and oedema, and functional renal failure (hepato-

renal syndromes).

e. Portal hypertension and the compensatory development

of portosystemic collateral circulation cause oesophageal

varices (often with GI haemorrhage), splenomegaly with

pancytopenia, and ascites (hypoalbuminemia contributes).

f. Bacterial overgrowth, with translocation of bacteria and

toxins through the congested bowel wall into the portal

system, leads to systemic infections and spontaneous

bacterial peritonitis (infected ascites).

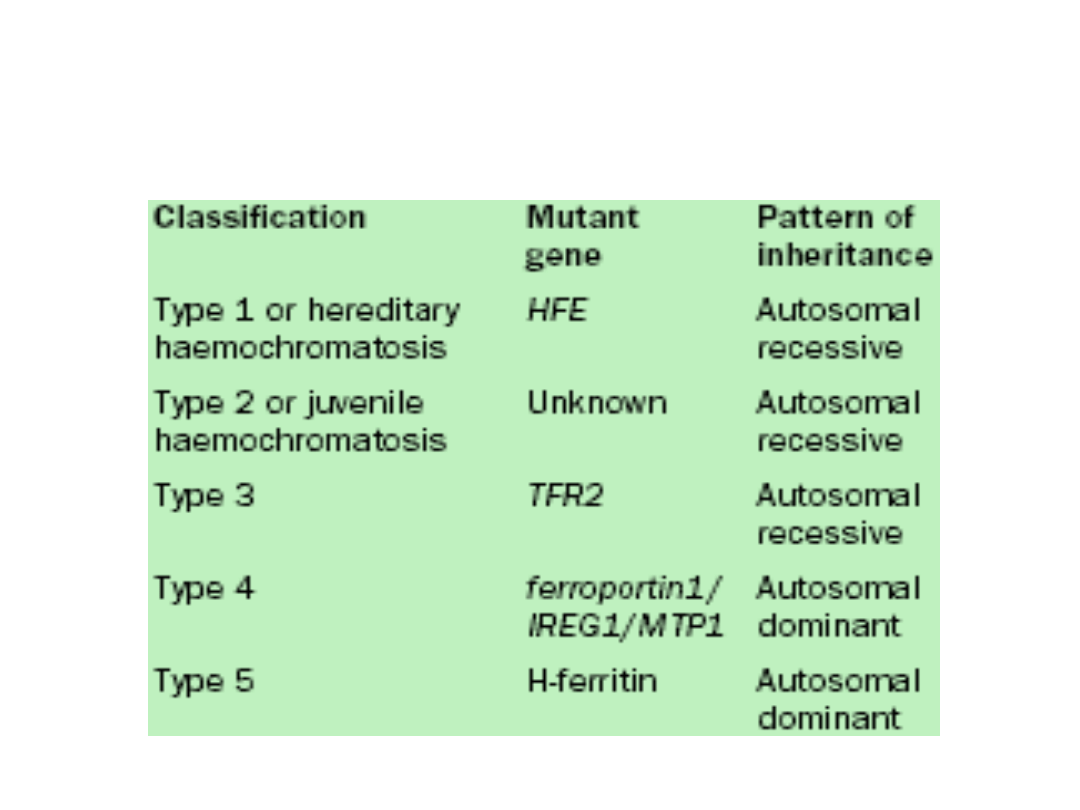

Haemochromatosis

• Haemochromatosis is the commonest inherited liver disease in

the United Kingdom.

• It affects about 1 in 200 of the population and is 10 times more

common than cystic fibrosis.

• Haemochromatosis produces iron overload, and patients

usually present with cirrhosis or diabetes due to excessive iron

deposits in the liver or pancreas.

• The genetic defect responsible is a single base change at a

locus of the HFE gene on chromosome 6, with this defect

responsible for over 90% of cases in the United Kingdom.

• Genetic analysis is now available both for confirming the

diagnosis and screening family members.

Genes mutated in hereditary

haemochromatosis

Haemochromatosis

• In haemochromatosis, iron accumulates first in the

transferrin pool, manifested by a rise in serum

transferrin saturation, and subsequently in tissue

stores—especially the hepatic parenchyma—which is

accompanied by a progressive increase in

concentrations of serum ferritin.

• The clinical features of the disease arise as a result of

the progressive accumulation of iron in the

parenchymal cells of the liver, pancreas, heart, and

anterior pituitary.

• In the absence of treatment to reduce iron

concentrations, a characteristic pattern of tissue injury

and organ failure can develop.

Haemochromatosis

• In its most extreme form, the disease manifests as cirrhosis,

hepatocellular cancer, diabetes mellitus, sexual dysfunction

due to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, cardiomyopathy, a

destructive arthritis, and generalised skin pigmentation.

• This phenotype is now less frequently seen, however, than

previously because of:

increased awareness of iron overload and early diagnosis,

genotyping done for family studies and screening

programmes .

• There is an average delay of 10 years between onset of

symptoms (lethargy, arthralgia) and diagnosis of

haemochromatosis, because of the non-specific nature of

the symptoms and because of the unfounded belief among

health professionals that haemochromatosis is rare.

Haemochromatosis

• Excess iron damages the liver, and presumably

other parenchymal organs, by induction of

oxidative stress and expression of cytokines, such

as transforming growth factor (TGF), which

promote hepatic fibrosis.

• The chemical nature of the reactive iron species

in cells is not known, but the presence of iron in

the circulation in excess of that bound by plasma

transferrin is well documented and is assumed to

promote oxidative damage to the lipid component

of cell membranes and intracellular organelles.

Haemochromatosis

• The disease typically affects middle aged men.

Menstruation and pregnancy probably account for

the lower presentation in women.

• Patients who are homozygous for the mutation

should have regular venesection to prevent

further tissue damage. Heterozygotes are

asymptomatic and do not require treatment.

Cardiac function is often improved by venesection

but diabetes, arthritis, and hepatic fibrosis do not

improve.

Presenting conditions in

haemochromatosis

• Cirrhosis (70%)

• Diabetes (adult onset) (55%)

• Cardiac failure (20%)

• Arthropathy (45%)

• Skin pigmentation (80%)

• Sexual dysfunction (50%)

Wilson's disease

• Wilson's disease is a rare autosomal recessive cause

of liver disease due to excessive deposition of copper

within hepatocytes.

• Abnormal copper deposition also occurs in the basal

ganglia and eyes.

• The defect lies in a decrease in production of the

copper carrying enzyme ferroxidase.

• Unlike most other causes of liver disease, it is

treatable and the prognosis is excellent provided that

it is diagnosed before irreversible damage has

occurred.

Wilson’s disease

• Patients may have a family history of liver or

neurological disease and a greenish brown

corneal deposit of copper (a Kayser Fleischer

ring), which is often discernible only with a

slit lamp.

• Most patients have a low caeruloplasmin

level and low serum copper and high urinary

copper concentrations.

• Liver biopsy confirms excessive deposition

of copper.

Risk factors associated with formation

of cholesterol gallstones

• Age > 40 years

• Female sex (twice risk

in men)

• Genetic or ethnic

variation

• High fat, low fibre diet

• Obesity

• Pregnancy (risk

increases with number

of pregnancies)

• Hyperlipidaemia

• Bile salt loss (ileal

disease or resection)

• Diabetes mellitus

• Cystic fibrosis

• Antihyperlipidaemic

drugs (clofibrate)

• Gallbladder dysmotility

• Prolonged fasting

• Total parenteral

nutrition

Charcot's triad of symptoms in severe

cholangitis

• Pain in right upper quadrant

• Jaundice

• High swinging fever with rigors and

chills

HELLP

• HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver tests, low platelets) syndrome and

acute fatty liver of pregnancy should be considered in the differential

diagnosis of abnormal liver tests in the second half of pregnancy,

usually in the third trimester.

• In HELLP syndrome, patients have signs of pre-eclampsia as well as

thrombocytopenia.

• Pre-eclampsia affects 3–10% of pregnancies, and HELLP syndrome

occurs in 20% of patients with severe pre-eclampsia.

• The most common symptom is abdominal pain, but it occurs in only

65% of affected patients.

• Many patients have no specific symptoms, and the condition is

diagnosed when laboratory tests are done on patients with pre-

eclampsia.

• Renal failure or seizures (eclampsia) may complicate the pre-

eclampsia.

• As many as 30% of patients with HELLP present, or are diagnosed,

after delivery.

• As with pre-eclampsia, the pathogenesis of this condition is unknown.

HELLP

• Aminotransferase elevations are the hallmark of this

syndrome, with AST elevations ranging from 70 to 6,000,

with a mean of 250 in a large series.

• This is not a true hepatic failure, and the prothrombin time is

normal except in the most severe cases complicated by

disseminated intravascular coagulation.

• The thrombocytopenia may be modest to very severe.

• Most patients are not jaundiced, and the hemolysis is

manifested as schistocytes and burr cells on peripheral

smear.

• The liver biopsy shows the findings typical of pre-eclampsia:

periportal hemorrhage and fibrin deposition. The severity of

the histological changes is not uniformly reflected in the

laboratory abnormalities, and biopsy is not usually needed

for diagnosis.

• The differential diagnosis includes viral hepatitis or, rarely,

ITP. Viral serologies are useful.

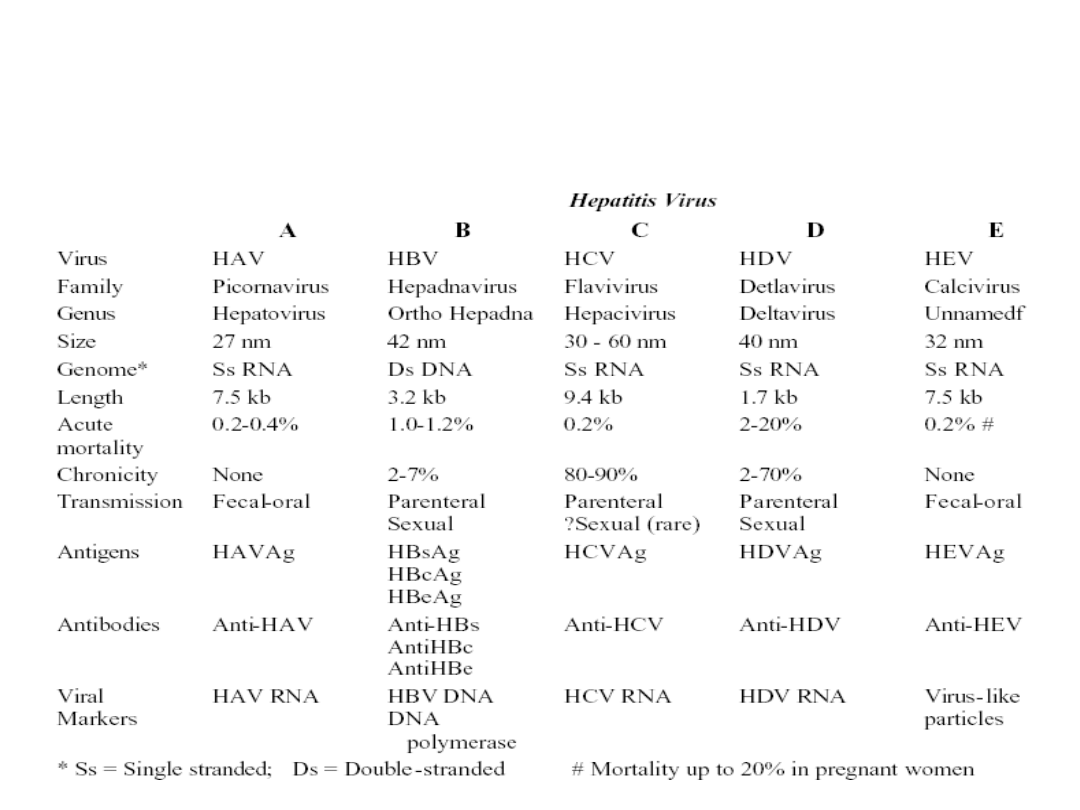

Summary of main viral hepatitis

characteristics

Common symptoms of acute viral

hepatitis

• Myalgia

• Nausea and vomiting

• Fatigue and malaise

• Change in sense of smell or taste

• Right upper abdominal pain

• Coryza, photophobia, headache

• Diarrhoea (may have pale stools and

dark urine)

Variations in the clinical course of

acute viral hepatitis

• Normal Convalescence: This is by far the most frequent

course in Hepatitis A, B, and E. Recovery occurs in only

about 15%-20% of patients with Hepatitis C.

• Acute, Fulminant, Massive Necrosis: Massive loss of

hepatocytes with collapse of residual structures.

• Submassive Necrosis

• Chronic Hepatitis : common with HCV, but not a sequela of

Hepatitis A or E. Occasionally, the acute hepatitis subsides

but never totally heals and may even show intermittent

acute relapses. Scattered focal liver cell death continues to

occur, especially in the periportal region (piecemeal

necrosis).

Other biochemical or haematological

abnormalities seen in acute hepatitis

• Leucopoenia is common ( < 5 x 10

9

/l

in 10% of patients)

• Anaemia and thrombocytopenia

• Immunoglobulin titres may be raised

Liver enzyme activity in liver disease

Hepatitis

Cholestasis or obstruction

“Mixed”

Alkaline

Phosphatase

Normal

Raised

Raised

γ glutamyl-

transferase

Normal

Raised

Raised

Alanine

transaminase Raised

Normal

Raised

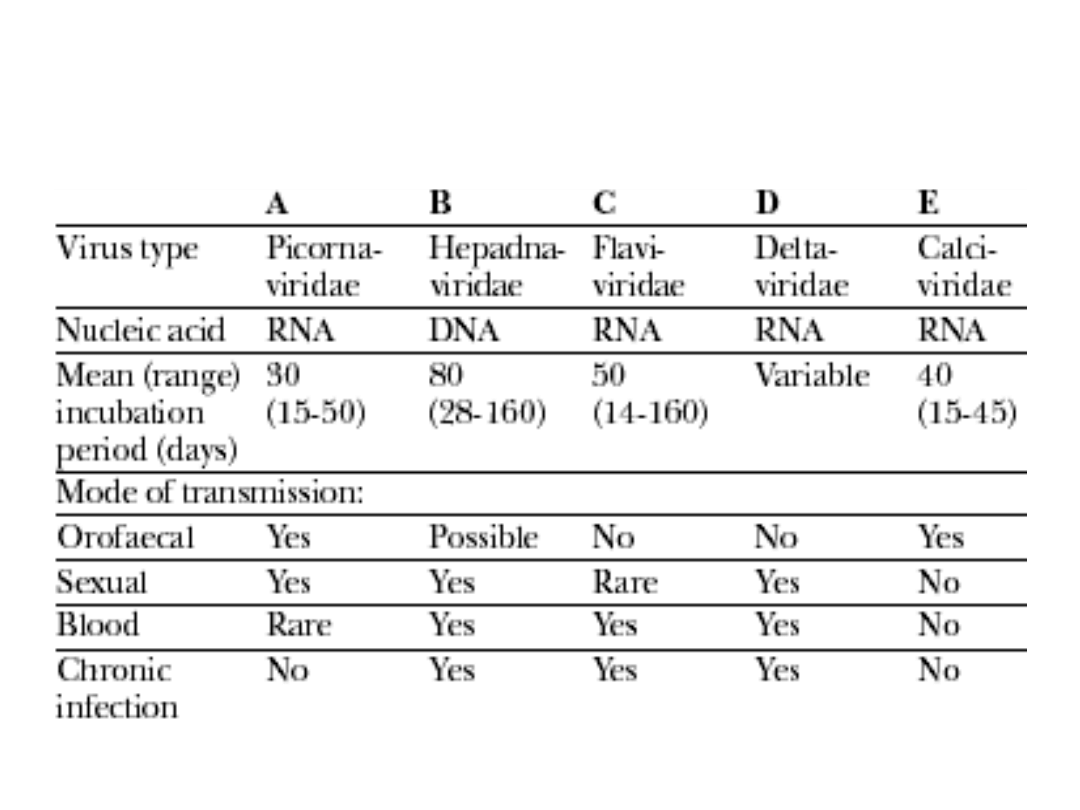

Types and modes of transmission of

human hepatitis viruses

Document Outline

- Slide 1

- Slide 2

- Slide 3

- Slide 4

- Slide 5

- Slide 6

- Slide 7

- Slide 8

- Slide 9

- Slide 10

- Slide 11

- Slide 12

- Slide 13

- Slide 14

- Slide 15

- Slide 16

- Slide 17

- Slide 18

- Slide 19

- Slide 20

- Slide 21

- Slide 22

- Slide 23

- Slide 24

- Slide 25

- Slide 26

- Slide 27

- Slide 28

- Slide 29

- Slide 30

- Slide 31

- Slide 32

- Slide 33

- Slide 34

- Slide 35

- Slide 36

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

ABC Transplantation of the liver and pancreas

Aspden THE CREATION OF THE PROTON (2005)

Investigating the Afterlife Concepts of the Norse Heathen A Reconstuctionist's Approach by Bil Linz

16 Changes in sea surface temperature of the South Baltic Sea (1854 2005)

0262033291 The MIT Press Paths to a Green World The Political Economy of the Global Environment Apr

2005 10 Dawn of the Uber Distro

Mordwa, Stanisław Religious Minorities of the Internet the Case of Lodz, Poland (2005)

Faculty of Theology operates on the basis of the Act of 27 July 2005 Law on Higher Education

Marilyn Yalom Birth of the Chess Queen A History (2005)

Publications of The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1964 2005 A Bibliography

Communist League Basic Principles of the Communist League (2005)

0791464539 State University of New York Press The Gathering Of Reason May 2005

148 Bitwa o brzuchy Battle of the Bulge, Jay Friedman, Jun 8, 2005

07 WoW War Of The Ancients Trilogy 03 The Sundering (2005 07)

Mansour Pasupathi The wisdom of experience Autobiographical narratives International Journal of Beha

BS EN ISO 1133 2005 Plastics Determination of the melt mass flow rate (MFR) and the melt volume flow

WarCraft (2005) War of the Ancients Trilogy 03 The Sundering Richard A Knaak

Falcon Aristotle and the Science of Nature (Cambridge, 2005)

The Modern Scholar David S Painter Cold War On the Brink of Apocalyps, Guidebook (2005)

więcej podobnych podstron