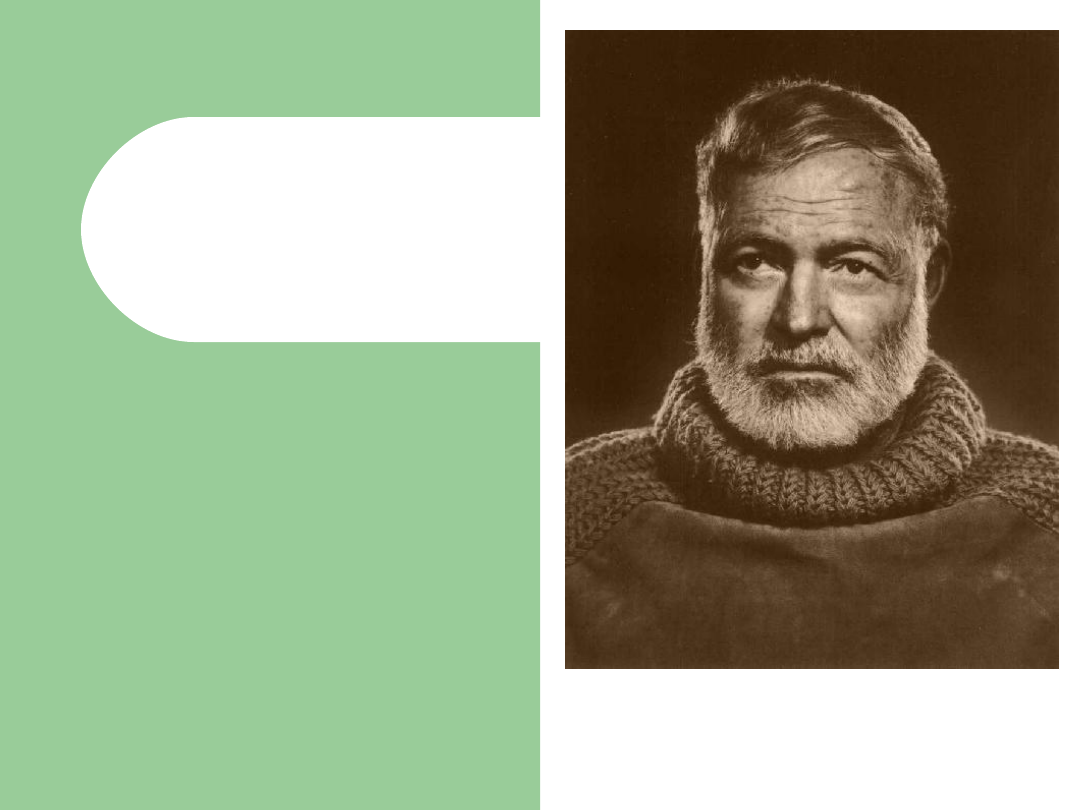

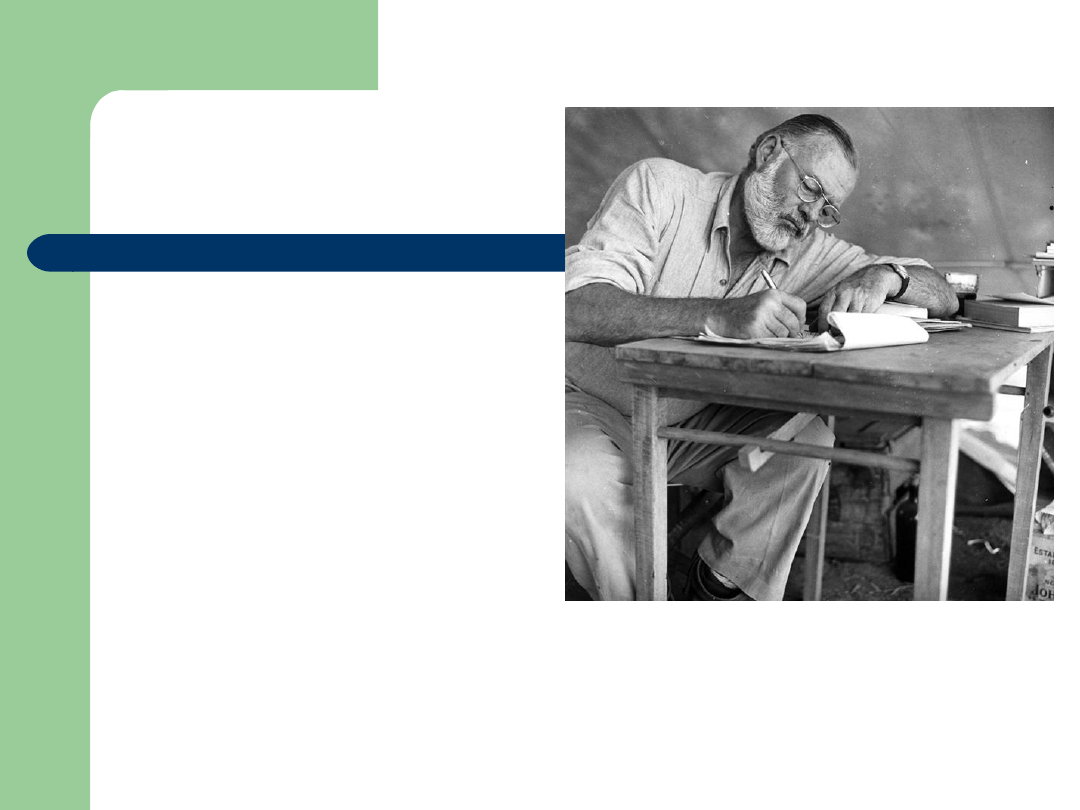

Ernest Miller

Hemingway

(1899-1961)

Life

Born in Oak Park, Illino

is

Educated at Oak Park

High School.

At 18 he became a

reporter for the

Kansas City Star.

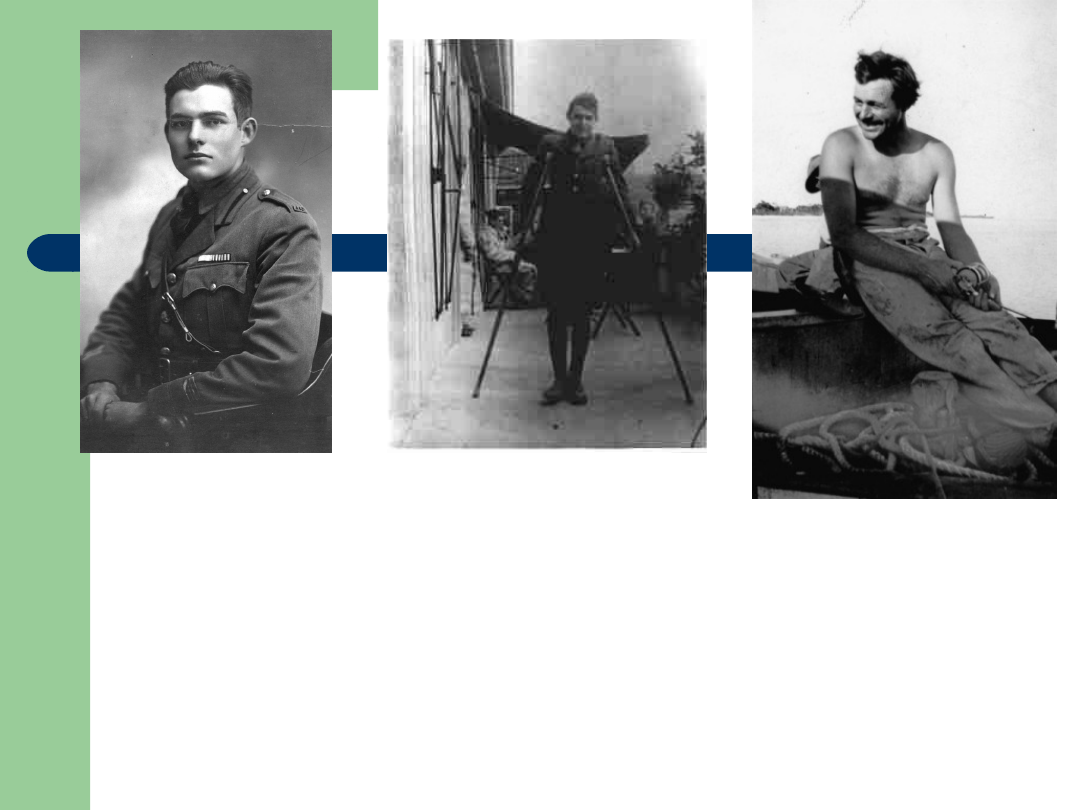

A volunteer

ambulance driver in

Italy during World War

I (1914-1918).

The Italian infantry, severely wounded.

After the war he settled in Paris. He was encouraged in

creative work by the American expatriate writers Ezra

Pound and Gertrude Stein.

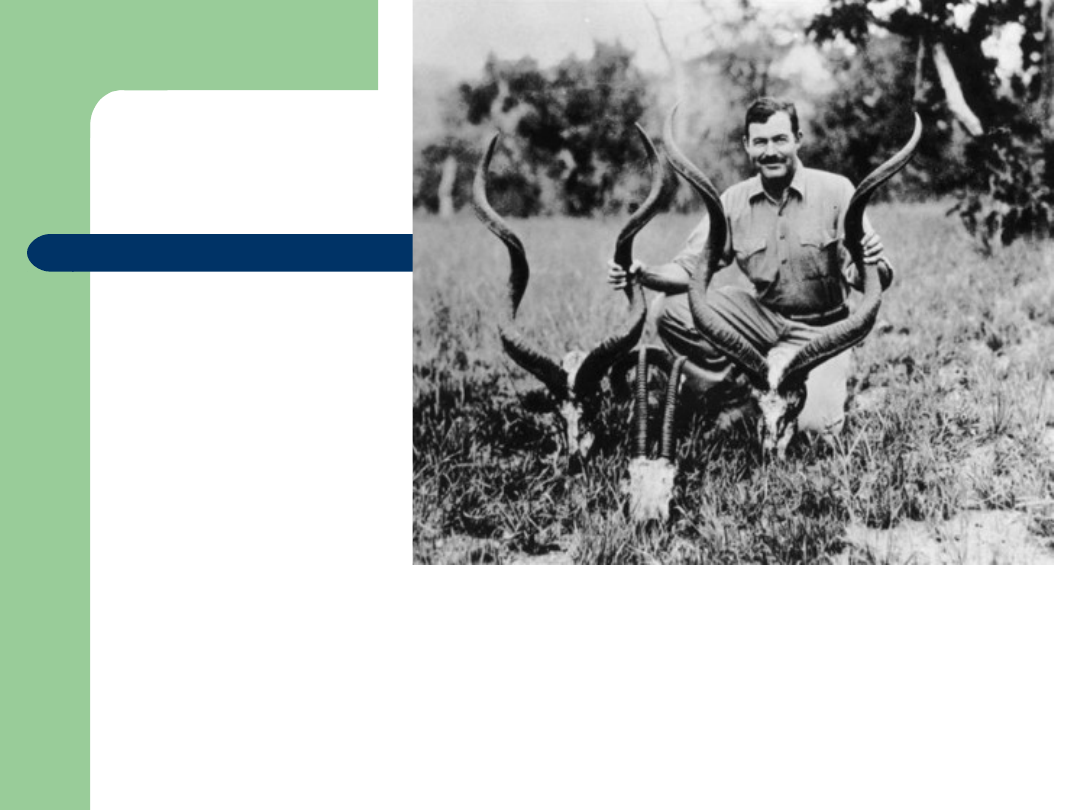

After 1927 Hemingway spent long periods of time in

Key West, Florida, in Spain and Africa.

In Key West,

1928

The Spanish Civil War (1936-

1939), a newspaper

correspondent.

In World War II (1939-1945), a

correspondent and a reporter

for the United States First

Army; participated in several

battles.

After the war Hemingway

settled in Cuba.

In 1958 he moved to Ketchum,

Idaho.

An avid fisherman, hunter, and bullfight

enthusiast

Fishing at

Horton's

Creek

(1904)

Close to death

several times:

in World War II when he was struck by a taxi

during a blackout;

in 1954 when his airplane crashed in Africa.

in the

Spanish

Civil War

when shells

burst inside

his hotel

room;

The lost generation

Character types:

Men and women deprived, by World War I, of

faith in the moral values in which they had

believed, and who lived with cynical disregard

for anything but their own emotional needs.

Men of simple character and primitive

emotions, such as bullfighters involved in

courageous and usually futile battles against

circumstances.

the "Hemingway hero"

- a boy named Nick Adams, subtly exposed to

a world of violence and evil through a series

of unsettling adventures, which are

epitomized by his being wounded in World

War I. This boy matures as a very masculine,

though sensitive, person, given to outdoor

activity and physical pleasure; but as a

result of his experiences he appears as well

as a wary, even at times extremely nervous,

figure.

the "Hemingway heroine"

- a selfless, compliant, and idealized

woman who is mistress to the hero, as

the British Catherine of A Farewell to

Arms, the Spanish Maria of For Whom

the Bell Tolls, and the Italian Renata of

Across the River and into the Trees.

the "Hemingway code"

- a set of principles having to do with honor,

courage, and endurance. In a highly compromising

world of tension and pain these principles enable a

man to conduct himself well in the losing battle

that is life and to show "grace under pressure."

Old Santiago, of The Old Man and the Sea,

behaves perfectly while losing his great fish. This

figure is Hemingway’s chief means of saying that

what counts most in existence is the dignity and

courage with which we conduct ourselves in the

process of being destroyed by life and the world.

A world at war, conditions imposed by war; a

narrow and highly distinctive world.

Works

The Sun Also Rises (1926)

A Farewell to Arms (1929)

Death in the Afternoon (1932)

Green Hills of Africa (1935)

To Have and Have Not (1937)

Best short stories: “The Killers,” “The Short

Happy Life of Francis Macomber,” and “The

Snows of Kilimanjaro”

For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940)

Men at War: The Best War Stories of All Time

(1942)

The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

In 1954 Hemingway

was awarded the

Nobel Prize in

literature.

He committed

suicide in Ketchum,

Idaho, in 1961.

in Kenya, 1953

Hemingway's economical writing

style:

detached descriptions of action, using simple nouns and verbs

avoided describing his characters' emotions and thoughts

directly

eliminated the authorial point of view

made the reading of a text approximate the actual experience

as closely as possible

his style is characterized by crispness, laconic dialogue, and

emotional understatement.

essentially a colloquial style, but spare, objective,

unemotional, and often ironic

played a substantial role in ridding modern fiction of literary

embellishment, superficial artfulness, padding, sentimentality,

and, generally, the worst aspects of the romantic heritage.

"You haven't been around much, have you?"

"Yes, my dear. I have been around very much. I have been

around a very great deal."

"Drink your wine," said Brett. "We've all been around. I dare say

Jake here has seen as much as you have."

"My dear, I am sure Mr. Barnes has seen a lot. Don't think I don't

think so, sir. I have seen a lot, too."

"Of course you have, my dear," Brett said. "I was only ragging."

"I have been in seven wars and four revolutions," the count

said.

"Soldiering?" Brett asked.

"Sometimes, my dear. And I have got arrow wounds. Have you

ever seen arrow wounds?"

"Let's have a look at them."

The count stood up, unbuttoned his vest, and opened his shirt.

He pulled up the undershirt onto his chest and stood, his chest

black, and big stomach muscles bulging under the light.

"You see them?"

Below the line where his ribs stopped were two raised white

welts.

"See on the back where they come out.„

Above the small of the back were the same two scars, raised

as thick as a finger.

"I say. Those are something."

"Clean through."

The count was tucking in his shirt.

"Where did you get those?" I asked.

"In Abyssinia. When I was twenty-one years old."

"What were you doing?" asked Brett. "Were you in the army?"

"I was on a business trip, my dear."

"I told you he was one of us. Didn't I?" Brett turned to me.

“I love you, count. You're a darling."

"You make me very happy, my dear. But it isn't true."

"Don't be an ass."

"You see, Mr. Barnes, it is because I have lived very much that

now I can enjoy everything so well. Don't you find it like that?"

"Yes. Absolutely."

"I know," said the count. "That is the secret. You must get to

know the values."

"Doesn't anything ever happen to your values?" Brett asked.

"No. Not any more."

"Never fall in love?"

"Always," said the count. "I am always in love."

"What does that do to your values?"

"That, too, has got a place in my values."

"You haven't any values. You're dead, that's all."

"No, my dear. You're not right. I'm not dead at all."

We drank three bottles of the champagne and the count left

the basket in my kitchen. We dined at a restaurant in the Bois.

It was a good dinner. Food had an excellent place in the

count's values. So did wine. The count was in fine form during

the meal. So was Brett. It was a good party.

"Where would you like to go?" asked the count after dinner.

We were the only people left in the restaurant. The two waiters

were standing over against the door. They wanted to go home.

"We might go up on the hill," Brett said. "Haven't we had a

splendid party?"

The count was beaming. He was very happy.

"You are very nice people," he said. He was smoking a cigar

again. "Why don't you get married, you two?"

"We want to lead our own lives," I said.

"We have our careers," Brett said. "Come on. Let's get out of

this."

"Have another brandy," the count said.

"Get it on the hill."

"No. Have it here where it is quiet."

"You and your quiet," said Brett. "What is it men feel about

quiet?"

"We like it," said the count. "Like you like noise, my dear."

"All right," said Brett. "Let's have one."

"Sommelier!" the count called.

"Yes, sir."

"What is the oldest brandy you have?"

"Eighteen eleven, sir."

"Bring us a bottle."

"I say. Don't be ostentatious. Call him off, Jake."

"Listen, my dear. I get more value for my money in old

brandy than in any other antiquities."

"Got many antiquities?"

"I got a houseful."

Finally we went up to Montmartre. Inside Zelli's it was

crowded, smoky, and noisy. The music hit you as you went

in. Brett and I danced. It was so crowded we could barely

move. The nigger drummer waved at Brett. We were

caught in the jam, dancing in one place in front of him.

"Hahre you?"

"Great."

"Thaats good."

He was all teeth and lips.

"He's a great friend of mine," Brett said. "Damn good

drummer."

The music stopped and we started toward the table where

the count sat. Then the music started again and we

danced. I looked at the count. He was sitting at the table

smoking a cigar. The music stopped again.

Document Outline

- Slide 1

- Slide 2

- Slide 3

- Slide 4

- Slide 5

- Slide 6

- Slide 7

- Slide 8

- Slide 9

- Slide 10

- Slide 11

- Slide 12

- Slide 13

- Slide 14

- Slide 15

- Slide 16

- Slide 17

- Slide 18

- Slide 19

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Hemingway For Whom The?ll Tolls

Clean Well Lighted Place by Hemingway

Tok Show-Hemingway, język polski w gimnazjum

Hotchner Papa Heminguey 424906

Hemingway A?rewell To Arms

Hemingway E Stary czlowiek i morze

E. Hemingway - Stary człowiek i morze, Gimnazjum

E. Hemingway STARY CZŁOWIEK I MORZE, Lektury gimnazjum

Hemingway The Snows of Kilimanjaro

Hemingway The Old Man and the Sea

Ernest Hemingway Stary czlowiek i morze

Hemingway Ernest Stary czlowiek i morze

Hemingway, wstep do BN

Hemingway Ernest Wiosenne wody

Hemingway Ernest 49 opowiadań

więcej podobnych podstron