Associations among adolescent risk behaviours

and self-esteem in six domains

Lauren G. Wild,

1

Alan J. Flisher,

1

Arvin Bhana

2

and Carl Lombard

3

1

University of Cape Town, South Africa;

2

Human Sciences Research Council, Durban, South Africa;

3

Medical Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

Background: This study investigated associations among adolescents’ self-esteem in 6 domains (peers,

school, family, sports/athletics, body image and global self-worth) and risk behaviours related to

substance use, bullying, suicidality and sexuality. Method: A multistage stratified sampling strategy

was used to select a representative sample of 939 English-, Afrikaans- and Xhosa-speaking students in

Grades 8 and 11 at public high schools in Cape Town, South Africa. Participants completed the mul-

tidimensional Self-Esteem Questionnaire (SEQ; DuBois, Felner, Brand, Phillips, & Lease, 1996) and a

self-report questionnaire containing items about demographic characteristics and participation in a

range of risk behaviours. It included questions about their use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, solvents

and other substances, bullying, suicidal ideation and attempts, and risky sexual behaviour. Data was

analysed using a series of logistic regression models, with the estimation of model parameters being

done through generalised estimation equations. Results: Scores on each self-esteem scale were sig-

nificantly associated with at least one risk behaviour in male and female adolescents after controlling for

the sampling strategy, grade and race. However, specific self-esteem domains were differentially related

to particular risk behaviours. After taking the correlations between the self-esteem scales into account,

low self-esteem in the family and school contexts and high self-esteem in the peer domain were signi-

ficantly independently associated with multiple risk behaviours in adolescents of both sexes. Low body-

image self-esteem and global self-worth were also uniquely associated with risk behaviours in girls, but

not in boys. Conclusions: Overall, the findings suggest that interventions that aim to protect adoles-

cents from engaging in risk behaviours by increasing their self-esteem are likely to be most effective and

cost-efficient if they are aimed at the family and school domains. Keywords: Adolescence, bullying,

self-esteem, sexual behaviour, substance use, suicidal behaviour.

In recent years, researchers have begun to pay

increasing attention to adolescent risk behaviours.

The primary reason for this is that the major causes of

adolescent morbidity and mortality are not diseases

but preventable behaviours, in interaction with social

and environmental factors. Adolescent health prob-

lems are mainly related to sexual and reproductive

health and the use of substances such as tobacco,

alcohol and psychoactive drugs. Accidents (especially

traffic incidents), suicide and violence from others are

the leading causes of death in individuals aged be-

tween 10 and 19 (World Health Organization, 1993).

Risk behaviours do not only jeopardise physical

health, however. They also have psychological and

social outcomes, in that they can interfere with the

accomplishment of normal developmental tasks and

the fulfilment of expected social roles (Jessor, 1991).

There is considerable evidence that adolescent risk

behaviours

are

interrelated

(Flisher,

Ziervogel,

Chalton, Leger, & Robertson, 1996; Jessor, 1991;

McGee & Williams, 2000). This suggests that health-

compromising behaviours in adolescents may have

common underlying factors, and that the identifica-

tion of these aetiological factors is likely to have

important implications for designing effective inter-

vention programmes.

One possible antecedent of risk behaviours in

adolescence is low self-esteem. Self-esteem is gen-

erally used to refer to an individual’s evaluation of

him- or herself, including feelings of self-worth

(Coopersmith, 1967; Rosenberg, 1979). Several the-

orists have argued that individuals with low self-

esteem are predisposed to adopt risk behaviours,

although the reasons given for this vary. Kaplan

(1975) proposes that adolescents whose experiences

in their conventional, normative membership groups

have led to feelings of self-rejection lose motivation to

conform to the conventional group’s norms. This

increases the likelihood that they will turn instead to

delinquent peers and adopt risk behaviours that are

valued and considered to be appropriate within these

deviant groups (Jang & Thornberry, 1998). Other

theorists have argued that people low in self-esteem

may turn to risk behaviours such as substance

abuse as a way to cope with or escape from the neg-

ative feelings associated with low self-worth (Bau-

meister, 1990; Jessor, Van den Bos, Vanderryn,

Costa, & Turbin, 1995), because these are the only

means available to them to deal with stress (Koval &

Pederson, 1999), or because they are easily influ-

enced by others through ‘peer pressure’ (McGee &

Williams, 2000). Such theories suggest that raising

adolescents’ self-esteem will help to protect them

against adopting risk behaviours.

Empirical evidence for a relationship between self-

esteem and adolescent risk behaviours is, however,

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 45:8 (2004), pp 1454–1467

doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00330.x

Ó Association for Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2004.

Published by Blackwell Publishing, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148, USA

inconclusive. Several cross-sectional and longitud-

inal studies have linked low self-esteem with current

and/or future risk behaviours. For example, low

self-esteem (assessed as an overall tone of self-dis-

approval) has been significantly associated with

substance abuse (Gordon & Caltabiano, 1996), in-

cluding a greater frequency and quantity of alcohol

use and problem drinking (Scheier, Botvin, Griffin, &

Diaz, 2000), smoking (Carvajal, Wiatrek, Evans,

Knee, & Nash, 2000), using cannabis (Ho

¨fler et al.,

1999) and using inhalants (Howard & Jenson, 1999;

Howard, Walker, Walker, Cottler, & Compton, 1999).

Low self-esteem has also been linked with other

health risk behaviours such as problem eating

(McGee & Williams, 2000) and suicidal ideation or

behaviours (McGee & Williams, 2000; Neumark-

Sztainer, Story, French, & Resnick, 1997; Vella,

Persic, & Lester, 1996; Yoder, 1999).

Other researchers have found that associations

between low self-esteem and risk behaviours are

limited to certain demographic groups. For example,

four studies have linked smoking, problem drinking

and/or unhealthy weight loss behaviours with low

self-esteem for girls, but not for boys (Abernathy,

Massad, & Romano-Dwyer, 1995; Koval, Pederson,

Mills, McGrady, & Carvajal, 2000; Neumark-Sztain-

er et al., 1997; Pitka

¨nen, 1999). Berry, Shillington,

Peak, and Hohman (2000) found that lower self-

esteem in adolescence appeared to increase the odds

of a teen pregnancy for blacks and Hispanics, but

not for whites and Native Americans.

Still other studies have found that after controlling

for other highly correlated child and family back-

ground variables, low self-esteem is unrelated to

later alcohol intake or problem drinking (Poikolai-

nen, Tuulio-Henriksson, Aalto-Seta

¨la, Marttunen,

& Lo

¨nnqvist, 2001; Scheier et al., 2000), increased

smoking (Carvajal et al., 2000), substance use

in general (Koval & Pederson, 1999; McGee &

Williams, 2000; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 1997; West

& Sweeting, 1997), suicidality (Beautrais, Joyce, &

Mulder, 1999; Kingsbury, Hawton, Steinhardt, &

James, 1999; Roberts, Roberts, & Chen, 1998) or

early sexual activity and adolescent pregnancy

(Hockaday, Crase, Shelley, & Stockdale, 2000;

McGee & Williams, 2000; Neumark-Sztainer et al.,

1997; West & Sweeting, 1997). In fact, one study

(Paul, Fitzjohn, Herbison, & Dickson, 2000) found

that higher self-esteem was an independent predic-

tor of early sexual intercourse in females, but not in

males.

One probable reason for the inconsistencies in

these findings is that researchers have used different

operational definitions of self-esteem, and have var-

ied in the extent to which they have controlled for its

covariates. A study by Kawabata, Cross, Nishioka,

and Shimai (1999) suggests that one way of

approaching this issue might be to replace the uni-

dimensional measures of global self-esteem used in

most studies with a more specific, multidimensional

measure. These researchers found a trend for Jap-

anese adolescents who had ever smoked to report

lower perceived cognitive competence and lower

family self-esteem but higher perceived physical

competence than those who had never smoked.

Since interventions that address specific domains or

components of self-esteem appear to be more suc-

cessful than programmes that attempt to enhance

global self-esteem directly (Harter, 1998), further

exploration of possible differential relationships

between adolescent risk behaviours and different

domains of self-esteem is important.

Inconsistencies in previous research results might

also reflect sampling characteristics. The research

reviewed above has been conducted in a number of

different countries in North America, Europe and

Australasia, and the research findings might be

influenced by cultural variations in conceptions of,

and responses to, risk behaviours and mental health

(Poikolainen et al., 2001). Further research is

therefore needed to investigate links between specific

domains of self-esteem and a variety of risk behav-

iours in other cultures. In particular, we are not

aware of any published studies that examine these

relationships in developing countries.

As a first step towards addressing this gap, Wild,

Flisher, Bhana, and Lombard (2002a) conducted a

pilot study examining links between the multidi-

mensional Self-Esteem Questionnaire (SEQ; DuBois,

Felner, Brand, Phillips, & Lease, 1996) and indica-

tors of substance use and suicidality in a sample of

116 adolescents enrolled in Grade 8 and Grade 11 at

independent (private) schools in Cape Town, South

Africa. Results of this study provided preliminary

evidence that specific domains of self-esteem are

differentially associated with particular risk behav-

iours. Family self-esteem showed the strongest

overall pattern of correlations with the risk behav-

iours assessed, and made a significant unique con-

tribution to predicting whether a student had ever

smoked a whole cigarette, used illicit drugs, and

thought about or attempted suicide. Lower school

self-esteem was also significantly associated with

smoking, and lower global self-esteem was signific-

antly associated with suicidality. In contrast, higher

sports/athletics self-esteem was significantly asso-

ciated with an increased probability of using alcohol

in the past month and smoking. Self-esteem with

respect to peers and body image did not make a

unique contribution to predicting any of the risk

behaviours assessed.

Adolescents attending independent schools are

not representative of high school students in Cape

Town since they have high socioeconomic status,

and it is not clear to what extent these findings can

be generalised to all adolescents. Moreover, the

sample size in this study was too small to stratify the

data by gender, although previous research has

suggested that predictors of risk behaviour may dif-

fer for boys and girls (Abernathy et al., 1995; Koval

Self-esteem and adolescent risk behaviours

1455

et al., 2000; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 1997; Pitka

¨nen,

1999). The present study was therefore designed to

extend this pilot work to a considerably larger,

representative sample of English-, Afrikaans- and

Xhosa-speaking public high-school students in Cape

Town. In particular, it aimed to explore associations

among adolescents’ self-evaluations in the contexts

of peers, school, family, sports/athletics and body

image and their feelings of global self-worth, and risk

behaviours related to substance use, bullying, suicid-

ality and sexuality.

Method

Participants

The study population was all students in Grades 8 and

11 attending public high schools in Cape Town. These

grade levels were selected in order to include as wide an

age range as possible, given that it was not financially

feasible to sample students in all grade levels. Grade 8

is the first year of high school in South Africa, and

Grade 11 is the penultimate year. Researchers are not

usually permitted access to Grade 12 students as they

are preparing for their final examinations.

Schools were stratified by postal code groupings, as

areas with the same postal code tend to be relatively

homogenous with regard to socio-economic status and

racial composition. We selected 39 schools such that

the proportion of the selected schools in a particular

stratum was directly proportional to the number of

students in that stratum. Within each stratum, the

selection probability of a school was proportional to the

number of students in that school. Two classes were

randomly selected from each participating grade, and

40 students were randomly selected from their com-

bined class lists. An additional 5 students were selected

as replacements for a maximum of 5 absent students.

This procedure yielded a total sample of 2,946 stu-

dents, of whom every third student in each class com-

pleted

the

self-esteem

measure.

The

remaining

students completed questionnaires assessing other

potential predictors of adolescent risk behaviour that

are not included in this report.

Of the participating students (N

¼ 939), 480 (51%)

were in Grade 8. The mean age of the 478 Grade 8

students who reported this information was 14.1 years

(range

¼ 12–24, SD ¼ 1.22), while the mean age of the

457 Grade 11s who provided this information was

17.4 years (range

¼ 15–26, SD ¼ 1.70). Five hundred

and nineteen of the 920 participants (56%) who pro-

vided information on their gender were female.

Of the 908 students who reported their racial classi-

fication, 459 (51%) described themselves as coloured

(derived from Asian, European and African ancestry),

241 (26%) as black, 205 (23%) as white, and 3 as Asian.

These race groups are as defined by the repealed popu-

lation registration act of 1950, and do not have

anthropological or scientific validity. However, they are

used because there are differences between the groups

for many indicators of health, mediated by political and

economic factors (Ellison, De Wet, Ijsselmuiden, &

Richter, 1996). Census figures suggest that blacks may

have been underrepresented in this sample, while

whites were overrepresented. Estimates of the racial

breakdown of 10- to 19-year-olds in Cape Town in 2001

were 53% coloured, 32% black, 14% white and 1%

Asian, although preliminary independent demographic

analyses suggest that these figures underestimate the

white population (Statistics South Africa, 2003). The

original English-language version of the questionnaire

was completed by 399 adolescents (42%), the Afrikaans

version by 384 adolescents (41%), and the Xhosa

version by 156 adolescents (17%).

Measures

Self-esteem.

Adolescents’ self-esteem was assessed

using the multidimensional Self-Esteem Questionnaire

(SEQ) developed by DuBois et al. (1996). The measure

consists of 42 items, each of which is rated on a 4-point

scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

Each item is scored 1 to 4, with higher values indicating

higher self-esteem. In order to guard against possible

bias associated with response style, ten items are

negatively worded and reverse scored.

The SEQ is divided into six subscales. One of these

contains items directly assessing adolescents’ global

self-worth (e.g., ‘I am happy with myself as a person’).

The remaining subscales assess adolescents’ self-evalu-

ations with respect to five salient contexts or domains of

adolescents’ experience: peers (e.g., ‘I am as popular

with kids my own age as I want to be’), school (e.g., ‘I am

good enough at math’), family (e.g., ‘I am happy with

how much my family loves me’), sports/athletics (e.g., ‘I

am as good at sports/physical activities as I want to be’)

and body image (e.g., ‘I like my body just the way it is’).

The SEQ was selected in preference to other possible

self-esteem measures for several reasons. DuBois

et al.’s (1996) use of an ecological-transactional theor-

etical framework greatly assists in the interpretation of

self-esteem data in relation to various risk behaviours,

and the scale is designed to measure self-esteem in the

domains centrally related to adolescent adaptation and

risk. The measure was also considered to be highly

suitable because it was developed on adolescents in the

age ranges for the current study.

In addition, few other measures of self-esteem have

been subjected to adequate programmes of validation

research, including social desirability bias. DuBois

et al. (1996) provide such data in the form of two studies

that examine the psychometric properties of the Self-

Esteem scale. They found that scores obtained on the

SEQ had good internal consistency (coefficient alphas

for each subscale ranging from .81 to .91) and test–

retest reliability (rs ranging from .74 to .84) for a com-

munity sample of American adolescents. They also

provided evidence for the factorial validity of the sub-

scale structure, and for the SEQ’s convergent and dis-

criminant validity across self-report, interview and

parent-report forms.

Wild, Flisher, Bhana, and Lombard (2002b) invest-

igated the reliability and factorial validity of the SEQ

with two samples of adolescents enrolled in Grade 8

and 11 at schools in Cape Town. Participants were 900

students attending public schools, and 116 students

attending independent (private) schools. Results pro-

vided general support for the 6-factor structure pro-

posed by DuBois et al. (1996) and indicated that the

1456

Lauren G. Wild et al.

SEQ scale scores have good internal consistency

(Cronbach alphas ranging from .75 to .92) and ade-

quate test–retest reliability (Pearson rs ranging from .73

to .83) for English-speaking South Africans. When

Afrikaans and Xhosa translations of the questionnaire

were included in the analyses, internal consistency re-

mained above the minimum level of .70 recommended

for research use (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) for all

subscales except the sports/athletics scale (a

¼ .67).

One item (28) which had an item-total correlation of .06

and a nonsignificant factor loading on the sports/ath-

letics self-esteem factor was consequently omitted from

the scale for this study, raising the alpha coefficient for

this scale to an acceptable .73. Since there is no abso-

lute cut-off point to identify ‘low’ self-esteem, we di-

chotomised

self-esteem

scores

by

distinguishing

between those adolescents with scores below the med-

ian in each domain and those with higher scores.

Demographic information and risk behaviours.

The

participants completed a self-report risk questionnaire

containing items about demographic characteristics

and asking about their participation in a range of health

risk behaviours. It included questions about their use of

tobacco, alcohol, cannabis (‘dagga’), solvents and other

substances, bullying, suicidality and sexuality. The full

items used to assess these risk behaviours are included

as an appendix. While it is recognised that these items

do not cover the full range of adolescent risk behaviours

(e.g., extreme eating behaviour, road-related beha-

viour), they were selected because they represent

behaviours that are of particular concern in the popu-

lation under study. The risk behaviours were defined as

clearly as possible to reduce the likelihood of ambiguity,

and the level of language was appropriate for both

Grades 8 and 11. This questionnaire was subject to

extensive pilot testing both in small groups and a

classroom context, and similar versions of this ques-

tionnaire have been used in other school-based epi-

demiological studies in South Africa (Flisher, 1998).

Flisher, Evans, Muller, and Lombard (in press) have

shown that this instrument has an adequate level of

test–retest reliability. Kappa values for the eight indi-

vidual items included in the analysis were moderate to

almost perfect, ranging from 52.0 (for telling someone

they intended to commit suicide) to 85.4 (for having ever

smoked a whole cigarette). It was not possible to cal-

culate kappa coefficients for the remaining seven items,

either because the marginal proportions were not

homogenous or because the prevalence rates were too

low. However, the observed agreement for each of these

items was higher than 92%.

The following health-compromising behaviours were

included as binary outcome measures in this study: (a)

having used alcohol (other than a few sips) in the pre-

vious month; (b) having smoked cigarettes in the pre-

vious month; (c) ever having used any illicit drug or

inhalants; (d) having bullied somebody at school during

the previous 12 months; (e) having been bullied at

school during the previous 12 months; (f) having

thought about committing suicide, threatened to do so,

or attempted to do so in the previous 12 months; (g)

having had more than 2 sexual partners in the previous

12 months, known their most recent partner for less

than 7 days before intercourse, and/or not used any

form of contraception or protection against disease on

the last occasion they had sexual intercourse (risky

sexual behaviour).

Procedure

The questionnaires were translated from English into

Xhosa and Afrikaans, and then back-translated into

English by other people who had these languages as

home language.

The back-translated versions were compared with the

original version, and any discrepancies were resolved

by negotiation between the original translators and

those doing the back-translations. Translated versions

of the questionnaire were then piloted in small groups

and classrooms in order to ensure that the translations

were adequate.

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from

the Western Cape Education Department and the

principals of the selected schools. Questionnaires were

administered in the classroom by members of the re-

search team, and participants were assured that their

responses would be anonymous and confidential. No

members of the school staff were present during the

administration of the questionnaires, and care was

taken to ensure that the students were seated such that

they could not see the responses of their classmates.

Students were informed that they could choose not to

participate in the study as a whole or to omit selected

questions.

Statistical analysis

Preliminary analyses were conducted using the Survey

Data Analysis (SUDAAN) program. We calculated

means and proportions with 95% confidence intervals

(CI’s) taking the multistage stratified design into ac-

count. We used the without replacement design option.

The design stages were postal code area, school and

grade. We computed sampling weights using the num-

ber of students in the school, the number of students in

the grade (in a specific school) and the number of stu-

dents sampled from the grade. We compared the results

for each gender (within each grade) and for each grade

(within each gender). In comparing two groups, if the

95% CI’s do not overlap, there is a significant (p < .025)

difference between the groups. If the CI’s overlap but

not to the extent that the point estimate of one group is

contained within the CI of the other group, there is a

significant (p < .05) difference between the groups. If

they overlap to the extent that the point estimate of one

group is contained within the CI of the other group, we

cannot draw any conclusions as to whether there is a

significant difference between the groups.

The relationships between the independent variables

and the adolescent risk behaviours were investigated

through a series of logistic regression models, using

generalized estimation equations (GEE; Zeger & Liang,

1986) to estimate the model parameters. The GEE ap-

proach takes account of the clustering due to students

being sampled within schools. The binary dependent

variable for each model was modelled with the logit link

function. Results are presented as odds ratios (with

95% Confidence Intervals) that compare the odds

of reporting an outcome for the different levels of a

Self-esteem and adolescent risk behaviours

1457

particular independent variable, all other factors being

held constant. Two sets of regression results are

reported for each of the seven risk behaviour outcomes,

using the following predictor variables: (1) the relevant

self-esteem scale and the covariates of sex, grade and

race; and (2) all the self-esteem scales and demographic

variables. The data were stratified by gender for all

these analyses.

Biases associated with excluding participants with

incomplete responses were reduced by replacing miss-

ing data on the SEQ subscales with the mean of the

participants’ scores on the remaining items in that

subscale, provided that at least one half of the subscale

items had been completed. Following this procedure,

226 adolescents (24%) were still missing data on at

least one variable. Preliminary analyses indicated that

black adolescents were nearly twice as likely as the

reference group of coloureds to be missing data

(p < .01). However, the presence of missing responses

was unrelated to self-esteem or to any of the risk be-

haviours assessed. It was also unrelated to gender,

grade level or the adolescent’s average mark at school in

the previous year. Because the patterns of missing data

appeared to be unrelated to the primary study vari-

ables, listwise deletion procedures were therefore ap-

plied when the outcome or predictor variables were not

completed, resulting in a 4–17% loss in participants per

GEE model employed. Alpha was set at .05 for all

statistical analyses.

Results

Self-esteem subscales

Table 1 presents means and 95% confidence inter-

vals for the SEQ scales, stratified by gender and

grade, and using appropriate sampling weights.

Grade 8 boys scored significantly higher than grade

8 girls on the body image, sports/athletics and glo-

bal self-esteem scales, and Grade 11 boys scored

significantly higher than Grade 11 girls on all sub-

scales except school self-esteem. Grade 8 girls

scored significantly higher than Grade 11 girls on all

the self-esteem scales, and Grade 8 boys scored

significantly higher than Grade 11 boys on the

school self-esteem scale.

Prevalence of risk behaviours

Prevalence rates for the risk behaviours selected as

criterion variables for this study are displayed in

Table 2. Prevalence rates are presented in the form of

percentages (and 95% confidence intervals), strati-

fied by gender and grade and using appropriate

sampling weights. Grade 8 boys were significantly

more likely than Grade 8 girls to report having bul-

lied another student or been bullied at school and

having engaged in risky sexual behaviour, but were

significantly less likely to report suicidal ideation or

behaviour. Smoking, drinking alcohol, using drugs,

bullying another student and risky sexual behaviour

were all significantly more prevalent in Grade 11

boys than Grade 11 girls. However, Grade 11 girls

were more likely than Grade 11 boys to report

suicidal ideation or behaviour.

Grade 11 girls were significantly more likely than

Grade 8 girls to report alcohol and drug use, suicid-

ality, and risky sexual behaviour. Smoking, alcohol

and drug use, risky sexual behaviour and suicidality

were all significantly more common in Grade 11 boys

than Grade 8 boys. However, Grade 11 boys were

significantly less likely than Grade 8 boys to report

having been bullied at school in the previous year.

Associations between self-esteem and risk

behaviours

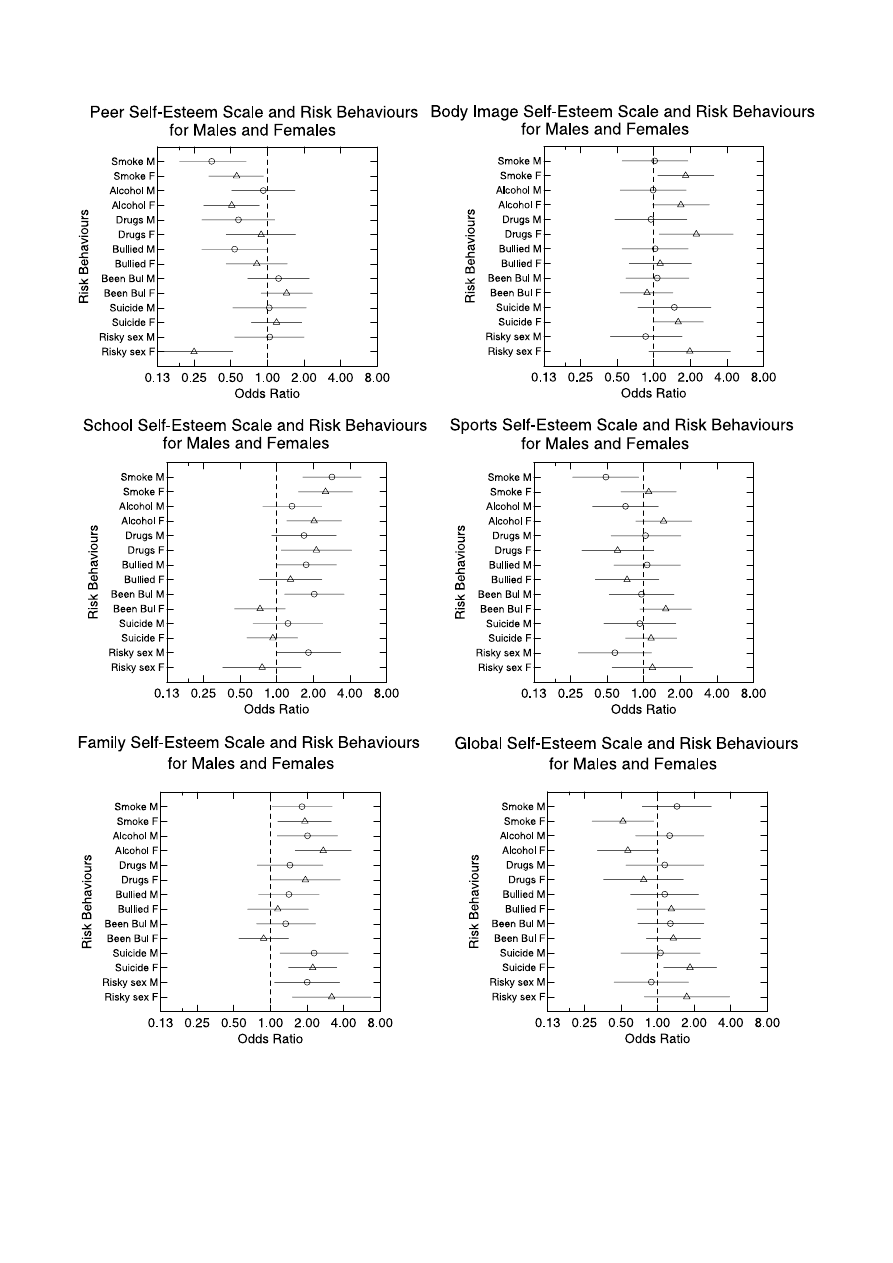

Peer self-esteem. Odds Ratios (and 95% Confidence

Intervals) between the risk behaviours and the SEQ

scales are presented in Table 3, and displayed

graphically in Figure 1. Odds ratios adjusted for the

clustering according to school, grade and race indic-

ated that for both sexes, individuals who scored be-

low the median on the peer self-esteem scale were

significantly more likely than those with higher self-

Table 1 Means (and 95% Confidence Intervals) for Self-Esteem Questionnaire (SEQ) scale scores, stratified by gender and grade

SEQ scale

Females

Males

Grade 8

Grade 11

Grade 8

Grade 11

n

M (CI)

n

M (CI)

n

M (CI)

n

M (CI)

Peers (8 items)

250

22.18

239

21.14

185

22.83

175

23.68

(21.73–22.63)

(20.68–21.60)

(21.93–23.73)

(23.33–24.03)

School (8 items)

250

21.65

239

19.81

186

21.83

175

20.64

(20.92–22.37)

(19.28–20.33)

(20.90–22.76)

(19.58–21.71)

Family (8 items)

251

23.89

238

23.14

185

24.68

175

25.00

(23.46–24.33)

(22.50–23.78)

(23.74–25.63)

(24.14–25.85)

Body image (4 items)

253

10.75

239

9.89

186

11.95

175

11.69

(10.26–11.24)

(9.44–10.34)

(11.57–12.32)

(11.28–12.10)

Sports/athletics (5 items)

248

12.75

239

11.56

184

14.18

175

14.02

(12.27–13.22)

(11.09–12.02)

(13.67–14.69)

(13.63–14.41)

Global (8 items)

251

22.09

238

21.09

185

23.62

175

23.35

(21.53–22.64)

(20.49–21.68)

(22.86–24.39)

(22.67–24.04)

1458

Lauren G. Wild et al.

esteem in the peer domain to report having been

bullied at school in the previous 12 months. For

girls, low peer self-esteem was also significantly

associated with an increased likelihood of suicidal

ideation or behaviour, and marginally significantly

(p < .06) associated with a decreased likelihood of

risky sexual behaviour.

After controlling for the other self-esteem scales as

well as grade and race, low peer self-esteem was no

longer significantly associated with an increased

likelihood of any of the risk behaviours for either sex.

However, it was independently associated with a

decreased likelihood of cigarette use for both sexes

and of risky sexual behaviour and alcohol use for

girls. There was also a marginally significant

association (p < .06) between low peer self-esteem

and a decreased likelihood of having bullied another

student at school for boys.

School self-esteem. Odds ratios controlling for the

clustering according to school, grade and race indic-

ated that low self-esteem with respect to school was

associated with an increased risk of alcohol and

cigarette use and of suicidality for both sexes, and

with an increased risk of drug use for girls. Boys with

scores below the median on the school self-esteem

scale were also more likely than those with higher

scores on this scale to report having bullied another

student, been bullied, and engaged in risky sexual

behaviour.

After controlling for the other self-esteem scales as

well as the demographic variables, low self-esteem in

the school context remained independently associ-

ated with an increased likelihood of cigarette use and

having been bullied for boys, and was marginally

significantly associated with an increased likelihood

of risky sexual behaviour and having bullied another

student at school. For girls, low school self-esteem

remained independently associated with an in-

creased likelihood of cigarette, drug and alcohol use.

Family self-esteem. After controlling for the clus-

tering of data according to school, grade and race,

low self-esteem in the family context was associated

with an increased likelihood of suicidality, alcohol

use and risky sexual behaviour for both sexes. It was

also associated with an increased likelihood of hav-

ing been bullied at school for boys, and with an in-

creased likelihood of cigarette and drug use for girls.

When the other self-esteem scales were also taken

into account, low family self-esteem was independ-

ently associated with an increased likelihood of sui-

cidality, risky sexual behaviour, and alcohol and

cigarette use for both sexes, and showed a margin-

ally significant association with an increased risk of

drug use for girls.

Body-image self-esteem. After controlling for the

clustering according to school, grade and race, boys

with low self-esteem with respect to their body-image

were significantly more likely to be suicidal and to

have been bullied at school than boys with higher

scores on the body-image self-esteem scale. How-

ever, body-image self-esteem was not independently

related to any of the risk behaviours for boys after

controlling for the other self-esteem scales.

For girls, low self-esteem with respect to body-

image was significantly associated with an increased

likelihood of suicidality, drug, alcohol and cigarette

use and risky sexual behaviour after controlling for

the clustering according to school, grade and race.

After controlling for the other self-esteem scales, girls

with scores below the median on the body image self-

esteem scale remained significantly more likely than

those with higher scores to report drug and cigarette

use, and marginally significantly (p < .06) more

likely to report alcohol use and suicidality.

Sports/athletics self-esteem. Low self-esteem with

respect to sports/athletics was significantly associ-

ated with an increased risk of having been bullied for

boys when the clustering according to school, grade

and race were controlled for. When the other self-

esteem scales were taken into account, low sports/

athletics self-esteem was significantly independently

associated only with a decreased likelihood of

cigarette use in boys.

For girls, low sports/athletics self-esteem was

associated with an increased risk of suicidality,

alcohol use and having been bullied after controlling

for the clustering according to school, grade and

race. However, after controlling for the other self-

esteem scales low sports/athletics self-esteem was

not independently associated with any of the risk

behaviours for girls.

Global self-worth. When the clustering according to

school, grade and race were controlled for, low global

self-worth was significantly associated with an in-

creased likelihood of suicidality in both sexes, of

having been bullied and used alcohol in boys, and of

risky sexual behaviour in girls.

When the other self-esteem scales were taken into

account, however, low global self-esteem did not make

a significant independent contribution to predicting

any of the risk behaviours for boys. Girls with low

Table 2 Prevalence rates (and 95% Confidence Intervals) for

risk behaviours, stratified by gender and grade

Risk

behaviour

Females

Males

Grade 8

M (CI)

Grade 11

M (CI)

Grade 8

M (CI)

Grade 11

M (CI)

Smoke

27 (19–34) 30 (23–37) 28 (20–35) 45 (35–54)

Alcohol

21 (15–26) 32 (24–39) 22 (16–28) 52 (43–62)

Drugs

10 (5–15)

16 (11–20) 12 (9–16)

38 (30–46)

Bullied

16 (11–20) 15 (10–21) 31 (22–40) 28 (20–35)

Been bullied 28 (24–33) 24 (18–31) 45 (37–53) 26 (21–31)

Suicide

30 (24–35) 41 (35–46) 16 (10–21) 25 (20–30)

Risky sex

5 (3–8)

19 (14–24) 18 (12–25) 39 (31–47)

Self-esteem and adolescent risk behaviours

1459

Table 3 Results of generalized estimating equations predicting risk behaviours from self-esteem

SEQ scale

Gender

Risk

behaviour

Adjusted for grade and race

Adjusted for grade, race and

other SEQ scales

n

OR

(95% CI )

n

OR

(95% CI )

Peers (<23)

Male

Smoke

342

.67

(.41–1.09)

339

.35**

(.19–.67)

Alcohol

337

1.37

(.84–2.24)

333

.93

(.51–1.69)

Drugs

348

.87

(.50–1.53)

344

.58

(.29–1.15)

Bullied

336

.82

(.50–1.35)

332

.54

(.29–1.01)

Been bullied

336

1.88**

(1.17–3.01)

332

1.24

(.69–2.21)

Suicide

346

1.70

(.97–3.00)

342

1.04

(.52–2.09)

Risky sex

337

1.34

(.79–2.29)

333

1.05

(.54–2.01)

Female

Smoke

466

.88

(.58–1.35)

463

.56*

(.33–.93)

Alcohol

454

.95

(.62–1.46)

451

.51*

(.30–.86)

Drugs

466

1.25

(.71–2.21)

463

.89

(.46–1.71)

Bullied

458

.96

(.59–1.59)

455

.82

(.46–1.46)

Been bullied

457

1.60*

(1.05–2.43)

454

1.44

(.89–2.34)

Suicide

466

2.19***

(1.47–3.27)

463

1.19

(.74–1.92)

Risky sex

451

.56

(.31–1.01)

448

.25***

(.12–.52)

School (<21)

Male

Smoke

343

2.11**

(1.32–3.37)

339

2.85***

(1.64–4.96)

Alcohol

338

1.61*

(1.00–2.59)

333

1.34

(.77–2.34)

Drugs

349

1.57

(.93–2.65)

344

1.68

(.91–3.09)

Bullied

337

1.64*

(1.00–2.69)

332

1.75

(.99–3.10)

Been bullied

337

2.56***

(1.57–4.17)

332

2.04*

(1.16–3.59)

Suicide

347

1.76*

(1.00–3.10)

342

1.24

(.64–2.39)

Risky sex

338

1.74*

(1.03–2.92)

333

1.83

(.99–3.36)

Female

Smoke

466

2.54***

(1.64–3.93)

463

2.52***

(1.51–4.20)

Alcohol

454

2.37***

(1.52–3.68)

451

2.03**

(1.21–3.41)

Drugs

466

2.45**

(1.37–4.38)

463

2.12*

(1.09–4.13)

Bullied

458

1.33

(.81–2.20)

455

1.30

(.72–2.35)

Been bullied

457

.99

(.65–1.49)

454

.73

(.45–1.18)

Suicide

466

1.95**

(1.32–2.89)

463

.93

(.57–1.49)

Risky sex

451

1.15

(.64–2.08)

448

.76

(.36–1.59)

Family (<24)

Male

Smoke

342

1.51

(.94–2.43)

339

1.82*

(1.03–3.22)

Alcohol

337

2.14**

(1.31–3.49)

333

2.02*

(1.14–3.56)

Drugs

348

1.39

(.81–2.36)

344

1.45

(.78–2.70)

Bullied

336

1.45

(.89–2.38)

332

1.42

(.80–2.52)

Been bullied

336

1.99**

(1.24–2.30)

332

1.34

(.77–2.35)

Suicide

346

2.87***

(1.64–5.05)

342

2.29*

(1.20–4.37)

Risky sex

337

1.84*

(1.09–3.11)

333

2.01*

(1.08–3.71)

Female

Smoke

466

1.84**

(1.20–2.81)

463

1.92*

(1.15–3.18)

Alcohol

454

2.50***

(1.61–3.87)

451

2.72***

(1.60–4.62)

Drugs

466

2.23**

(1.26–3.96)

463

1.94

(1.00–3.76)

Bullied

458

1.29

(.78–2.13)

455

1.15

(.65–2.05)

Been bullied

457

1.10

(.73–1.65)

454

.88

(.55–1.41)

Suicide

466

3.31***

(2.21–4.96)

463

2.23**

(1.41–3.51)

Risky sex

451

2.53**

(1.39–4.61)

448

3.19**

(1.52–6.69)

Body (<11)

Male

Smoke

343

1.01

(.62–1.64)

339

1.02

(.55–1.91)

Alcohol

338

1.32

(.79–2.19)

333

.99

(.53–1.85)

Drugs

349

1.11

(.63–1.95)

344

.95

(.48–1.87)

Bullied

337

1.19

(.72–1.99)

332

1.03

(.55–1.92)

Been bullied

337

1.64*

(1.01–2.68)

332

1.07

(.59–1.95)

Suicide

347

1.88*

(1.07–3.32)

342

1.48

(.74–2.95)

Risky sex

338

1.00

(.57–1.73)

333

.86

(.44–1.71)

Female

Smoke

469

1.88**

(1.22–2.89)

463

1.83*

(1.08–3.12)

Alcohol

457

1.88**

(1.22–2.92)

451

1.67

(.98–2.86)

Drugs

469

2.36**

(1.31–4.25)

463

2.24*

(1.11–4.49)

Bullied

461

1.32

(.80–2.16)

455

1.13

(.63–2.04)

Been bullied

460

1.08

(.71–1.63)

454

.88

(.53–1.44)

Suicide

469

2.53***

(1.71–3.76)

463

1.59

(.99–2.56)

Risky sex

454

1.82*

(1.01–3.29)

448

1.98

(.91–4.27)

Sports (<13)

Male

Smoke

341

.71

(.43–1.20)

339

.49*

(.26–.91)

Alcohol

336

1.03

(.61–1.74)

333

.71

(.38–1.32)

Drugs

347

1.17

(.66–2.08)

344

1.04

(.54–2.02)

Bullied

335

1.29

(.76–2.20)

332

1.07

(.57–2.01)

Been bullied

335

1.71*

(1.03–2.84)

332

.96

(.52–1.78)

Suicide

345

1.60

(.89–2.87)

342

.93

(.47–1.84)

Risky sex

336

.78

(.43–1.39)

333

.58

(.29–1.16)

Female

Smoke

464

1.36

(.88–2.11)

463

1.10

(.65–1.86)

Alcohol

452

1.69*

(1.08–2.63)

451

1.46

(.86–2.49)

1460

Lauren G. Wild et al.

global self-worth were more likely to report sui-

cidal ideation or behaviours than girls with higher

global self-esteem scores, but were less likely to

report smoking and (marginally significantly) using

alcohol.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore associations among

adolescents’ self-esteem in the context of peers,

school, family, sports/athletics and body image,

feelings of global self-worth, and risk behaviours

related to substance use, bullying, suicidality and

sexuality. Results indicated that after controlling for

the clustering according to school, grade and race,

scores on each self-esteem scale were significantly

associated with at least one risk behaviour in male

and female adolescents. However, specific domains

of self-esteem were differentially related to particular

risk behaviours.

Low global self-esteem was significantly associated

with an increased likelihood of suicidality in both

sexes, of having been bullied and used alcohol in

boys, and of risky sexual behaviour in girls after

controlling for the clustering of schools, grade, and

race. These findings provide some support for sev-

eral recent cross-sectional and prospective studies

conducted in North America, Europe and Austral-

asia which have linked low self-esteem (assessed as

a global, unidimensional measure) with risk behav-

iours such as suicidality (Neumark-Sztainer et al.,

1997; Vella et al., 1996; Yoder, 1999) and substance

abuse (Gordon & Caltabiano, 1996), including a

greater frequency and quantity of alcohol use and

problem drinking (Scheier et al., 2000).

In contrast to some of these studies, however

(Carvajal et al., 2000; Ho

¨fler et al., 1999; Howard &

Jenson, 1999; Howard et al., 1999), we did not find

any significant associations between global self-

esteem and an increased likelihood of cigarette or

drug use for either sex. Moreover, when the corre-

lations between global self-worth and the other self-

esteem scales were taken into account, low global

self-worth did not make a significant independent

contribution to predicting any of the risk behav-

iours in boys. For girls, it was independently asso-

ciated only with an increased risk of suicidality and

a decreased risk of cigarette and (marginally signi-

ficantly) alcohol use.

This does not mean that self-esteem is unimpor-

tant in predicting adolescent risk behaviours. Ra-

ther, the results of this study suggest that different

risk behaviours are more strongly related to certain

domains of self-esteem than others. Overall, the

findings of this study suggest that low self-esteem

with respect to family and school are the most per-

tinent predictors of risk behaviours in adolescents.

After controlling for the clustering according to

school, grade and race and the other self-esteem

scales, low family self-esteem was independently

associated with an increased likelihood of suicid-

ality, risky sexual behaviour, and alcohol and

cigarette use for both sexes, and with a marginally

significant increased risk of drug use for girls. This

finding is interesting in light of the widespread

assumption that peer relationships increasingly re-

place family relationships in adolescence, at least in

Western societies (Grotevant, 1998). However, it is

consistent with a body of recent theory and research

which recognizes that while time spent with family

Table 3 Continued

SEQ scale

Gender

Risk

behaviour

Adjusted for grade and race

Adjusted for grade, race

and other SEQ scales

n

OR

(95% CI )

n

OR

(95% CI )

Drugs

464

1.03

(.58–1.82)

463

.61

(.31–1.21)

Bullied

456

.88

(.53–1.47)

455

.73

(.40–1.33)

Been bullied

455

1.59*

(1.04–2.43)

454

1.52

(.93–2.47)

Suicide

464

2.04**

(1.36–3.06)

463

1.15

(.71–1.87)

Risky sex

449

1.21

(.66–2.20)

448

1.18

(.55–2.52)

Global (<22)

Male

Smoke

343

1.37

(.84–2.21)

339

1.45

(.75–2.78)

Alcohol

337

1.65*

(1.01–2.71)

333

1.26

(.66–2.40)

Drugs

348

1.26

(.73–2.19)

344

1.15

(.55–2.41)

Bullied

336

1.32

(.80–2.19)

332

1.15

(.60–2.18)

Been bullied

336

2.10**

(1.29–3.41)

332

1.28

(.69–2.40)

Suicide

346

2.02*

(1.15–3.55)

342

1.06

(.50–2.25)

Risky sex

336

1.17

(.68–2.02)

333

.89

(.44–1.80)

Female

Smoke

466

1.10

(.72–1.67)

463

.52*

(.29–.93)

Alcohol

454

1.31

(.86–2.01)

451

.57

(.32–1.02)

Drugs

466

1.60

(.92–2.81)

463

.77

(.36–1.63)

Bullied

458

1.36

(.83–2.24)

455

1.30

(.68–2.46)

Been bullied

457

1.42

(.95–2.14)

454

1.35

(.81–2.26)

Suicide

466

3.36***

(2.24–5.04)

463

1.85*

(1.12–3.06)

Risky sex

451

2.14*

(1.17–3.90)

448

1.74

(.78–3.91)

Note: OR

¼ odds ratio; CI ¼ confidence interval. All odds ratios are adjusted for the clustering of data according to school.

p < .06; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Self-esteem and adolescent risk behaviours

1461

typically decreases during adolescence and that

spent with friends increases, family relationships

remain important, and are significantly associated

with adolescents’ emotional health and competent

behaviour (e.g., Sweeting, West, & Richards, 1998;

for a review see Grotevant, 1998).

Figure 1 Odds ratios for males and females adjusted for clustering according to school, grade, race and other SEQ

scales

1462

Lauren G. Wild et al.

After controlling for the other self-esteem scales as

well as the demographic variables, low school self-

esteem remained independently associated with an

increased likelihood of cigarette use and having been

bullied for boys, and was marginally significantly

associated with an increased likelihood of risky

sexual behaviour and having bullied another stu-

dent at school. For girls, low school self-esteem re-

mained independently associated with an increased

likelihood of cigarette, drug and alcohol use. This

finding contrasts with McGee and Williams’ (2000)

study, in which academic self-esteem assessed in

preadolescence was unrelated to risk behaviour at

age 15 amongst adolescents in New Zealand. On the

other hand, it is consistent with Kawabata et al.’s

(1999) finding of an association between lower per-

ceived cognitive competence and ever having smoked

for young Japanese adolescents. Although the

reasons for these differences are unclear, it may be

that academic or school self-esteem is more closely

associated with current rather than future risk

behaviours, or that school self-esteem becomes a

stronger predictor of risk behaviour in adolescence

(when academic performance is often salient and

associated with class placement, selection of courses

and future career plans) than is the case in preado-

lescence. Alternatively, the strength of these associ-

ations may be affected by cultural variations in the

meaning and importance given both to academic

achievement and to the use of various psychoactive

substances in different countries.

When the other self-esteem scales were controlled

for, low self-esteem with respect to body-image did

not make a significant independent contribution to-

wards explaining any of the risk behaviours for boys,

but was significantly associated with an increased

likelihood of cigarette and drug use for girls, and

marginally significantly associated with alcohol use

and suicidality. This finding is consistent with evid-

ence that female adolescents react more negatively to

increases in body fat and weight gain and are typic-

ally more dissatisfied with their appearance than are

males (Harter, 1998). According to Harter, this

probably reflects the fact that although society and

the media tend to emphasise the importance of

physical attractiveness for both sexes, standards

regarding desirable bodily characteristics (such as

thinness) are particularly narrow and unrealistic for

women.

In contrast to the general pattern of results linking

low self-esteem with an increased likelihood of risk

behaviours, low self-esteem in some domains was

associated with a decreased likelihood of risk

behaviours when the remaining self-esteem scales

were held constant. Low peer self-esteem was inde-

pendently associated with a decreased likelihood of

cigarette use for both sexes and of risky sexual

behaviour and alcohol use for girls. There was also a

marginally significant association (p < .06) between

low peer self-esteem and a decreased likelihood of

having bullied another student at school for boys.

Low sports/athletics self-esteem was also associated

with a decreased likelihood of smoking in boys, while

low global self-worth was independently associated

with a decreased risk of cigarette and (marginally

significantly) alcohol use in girls.

One possible explanation for this apparent pro-

tective effect of low self-esteem in some domains is

that given equivalent levels of self-esteem with re-

spect to domains such as the school and family,

adolescents who are lower in self-esteem, and par-

ticularly those who perceive themselves as less

accepted by their peer group, may be less likely to

spend time with peers and to become involved in

romantic partnerships. They may therefore be less

likely to experience opportunities, temptation or

pressure to engage in behaviours such as smoking,

drinking and sexual intercourse. This explanation

would be consistent with West and Sweeting’s (1997)

finding that although global self-esteem was unre-

lated to risk behaviours in Glaswegian 15-year-olds,

adolescents who spent more time in unsupervised,

‘street-oriented’ peer activities were more likely to

smoke, drink, have used drugs and to be more sex-

ually experienced than their peers who were not in-

volved in this lifestyle. An alternative possibility (also

suggested by West & Sweeting, 1997) is that if be-

haviours such as smoking, drinking, sexual inter-

course and even bullying peers are valued or

admired by the peer group, engaging in these beha-

viours and adopting an identity as a ‘rebel’ may

actually increase adolescents’ self-esteem, partic-

ularly in the peer domain.

This raises an important limitation of the study

that must be taken into account when interpreting

the results. Although the analyses provide evidence

that certain domains of self-esteem are associated

with adolescent risk behaviours, the cross-sectional

nature of the data means that we cannot infer

causal or even temporal relationships among these

variables. It may be that in at least some cases,

adolescents’ risk behaviours affect their self-esteem

in particular domains as well as vice versa. For

example, substance use may lead to conflict with

parents and school authorities and to poorer aca-

demic performance at school, and hence to lower

feelings of self-esteem in these domains. Prospect-

ive, longitudinal studies in which measures of self-

esteem are taken prior to the risk behaviours in

question would be better equipped to examine the

direction of effect.

A second caveat with respect to these results is

that they were based on information provided by the

adolescent only. This raises the possibility that some

of the findings may be overstated because of shared

method variance. Although adolescents are likely to

be the most reliable reporters of both their feelings of

self-esteem and their risk behaviours, further re-

search obtaining information from multiple sources

would help to boost confidence in these results.

Self-esteem and adolescent risk behaviours

1463

A further limitation of this study is that the

measures of risk behaviour used do not take the

quantity or severity of the risk behaviour into ac-

count. For example, the measure of alcohol use

made no distinction between drinking that may be

normative and that which constitutes a health risk.

Similarly, the suicidality index did not distinguish

between adolescents who had made serious and life-

threatening attempts, youngsters whose attempts

are very mild or of limited lethality potential, and

those who have thought or talked about committing

suicide, but never actually attempted to do so.

Buster and Rodgers (2000) reported that self-esteem

accounted for a significant proportion of the variance

in heavy drinking behaviour in adolescents, but was

not significantly associated with light drinking.

Thus, future research is needed to examine the

possibility of differential relationships between self-

esteem and different levels of the risk behaviours

included in this study. Further research is also

needed to determine whether there is a cut-off point

beyond which changes in self-esteem are no longer

associated with increased risk or protection, in order

to determine which adolescents should be targeted

in intervention programmes.

Finally, it is important to note that low self-esteem

alone is unlikely to provide an adequate aetiological

explanation for the range of risk behaviours adoles-

cents may engage in. As Jessor (1991) argues, any

complete and responsible explanation of adolescent

risk behaviour needs to be complex, and to incor-

porate multiple domains (for example, the social

environment, the perceived environment, biology/

genetics, personality and [other] behaviour) as well

as their interactions. Moreover, this research was

conducted in the Cape Town metropolitan area, and

black adolescents may have been underrepresented

in the sample. As a result, generalisations to ado-

lescents in rural areas, other parts of South Africa

and other countries must be made with appropriate

caution.

Despite these caveats, this study has made a sig-

nificant contribution to the research literature in

demonstrating that investigating links between spe-

cific domains of self-esteem and adolescent risk

behaviours is likely to provide information that

cannot be obtained from global measures of self-

worth alone. First, it has shown that the likelihood of

adolescents engaging in a particular risk behaviour

(e.g., smoking cigarettes) may increase with low self-

esteem in particular domains (e.g., family and

school) and decrease with low self-esteem in other

areas (e.g., peers). Second, it has shown that the

links between self-esteem domains and risk behav-

iours may vary to some extent according to gender,

with body-image and global self-worth being inde-

pendent predictors of risk behaviours among girls,

but not boys. These findings are not only of theor-

etical interest, but have important implications for

designing effective interventions aimed at preventing

adolescents

from

adopting

dysfunctional

risk

behaviours.

Risky sexual behaviour among adolescents is of

particular concern in South Africa, as it contributes

towards the high prevalence of HIV/AIDS: data from

a national antenatal prevalence survey conducted in

1999 estimated that 16.5% of South African women

under the age of 20 were infected with HIV (Dickson-

Tetteh & Ladha, 2000). Previous research has found

that low self-esteem (assessed as a global construct)

may undermine abstinence, monogamy and condom

use amongst South African youth (for a review, see

Eaton, Flisher, & Aarø, 2003). The findings of this

study suggest that low self-esteem in the family

context is a stronger correlate of risky sexual beha-

viour for both boys and girls than low global self-

worth or low self-esteem in other domains. Improv-

ing the relationships and communication between

adults and adolescents in the home may therefore

have a role to play in helping to reduce sexual risk

behaviour amongst young people. Although current

interventions aimed at reducing the rates of HIV

infection pay little attention to the home setting, the

potential utility of targeting the family as a whole in

prevention programmes is supported by other re-

search reporting that many South African adoles-

cents experience poor communication with parents

about sexual matters, which in turn may contribute

to unsafe sexual behaviour (Eaton et al., 2003).

Overall, the results of this study suggest that

interventions that aim to protect adolescents from

engaging in risk behaviours by increasing their self-

esteem are likely to be most effective and cost-effi-

cient if they are aimed at the family and school do-

mains. Attempts to raise adolescents’ self-esteem by

providing them with opportunities and encourage-

ment to excel in other areas such as sports or peer

relationships may have several benefits for adoles-

cents, but the findings of this research suggest that

reducing the likelihood of engaging in risk behav-

iours is unlikely to be one of them.

Author notes

Lauren G. Wild and Alan J. Flisher, Department of

Psychiatry and Mental Health; Arvin Bhana, Child,

Youth and Family Development; Carl Lombard,

Biostatistics Unit.

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this research was provided by

the WHO Programme on Substance Abuse, the Uni-

ted Nations Development Programme, the South

African Medical Research Council, and the Medical

Faculty Research Committee of the University of

Cape Town. The authors would like to thank the

Western Cape Education Department, the prin-

cipals, staff and students of the schools that parti-

1464

Lauren G. Wild et al.

cipated in the study, Janet Evans and Lisa Wegner

for assistance with the fieldwork, and Martie Muller

for her contributions to data management.

Correspondence to

Lauren G. Wild, Department of Psychology, Univer-

sity of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa;

Fax: (+2721) 650 4104; Email: lwild@humanities.

uct.ac.za

References

Abernathy, T.J., Massad, L., & Romano-Dwyer, L.

(1995). The relationship between smoking and self-

esteem. Adolescence, 30, 899–907.

Baumeister, R.F. (1990). Suicide as escape from self.

Psychological Review, 97, 90–113.

Beautrais, A.L., Joyce, P.R., & Mulder, R.T. (1999).

Personality traits and cognitive styles as risk factors

for serious suicide attempts among young people.

Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 29, 37–47.

Berry, E.H., Shillington, A.M., Peak, T., & Hohman,

M.M. (2000). Multi-ethnic comparison of risk and

protective factors for adolescent pregnancy. Child and

Adolescent Social Work Journal, 17, 79–96.

Buster, M.A., & Rodgers, J.L. (2000). Genetic and

environmental influences on alcohol use: DF analysis

of NLSY kinship data. Journal of Biosocial Science, 32,

177–189.

Carvajal, S.C., Wiatrek, D.E., Evans, R.I., Knee, C.R.,

& Nash, S.G. (2000). Psychosocial determinants of

the onset and escalation of smoking: Cross-sec-

tional

and

prospective

findings

in

multiethnic

school samples. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27,

255–265.

Coopersmith, S. (1967). The antecedents of self-esteem.

San Francisco: Freeman.

Dickson-Tetteh, K., & Ladha, S. (2000). Youth health.

In A. Ntuli, N. Crisp, E. Clarke, & P. Barron (Eds.),

South African health review 2000. Durban: Health

Systems Trust.

DuBois, D., Felner, R.D., Brand, S., Phillips, R.S.C., &

Lease, A.M. (1996). Early adolescent self-esteem: A

developmental-ecological framework and assessment

strategy. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 6, 543–

579.

Eaton, L., Flisher, A.J., & Aarø, L. (2003). Unsafe sexual

behaviour in South African youth. Social Science and

Medicine, 56, 149–165.

Ellison, G.T.H., De Wet, T., Ijsselmuiden, C.B., &

Richter, L. (1996). Desegregating health statistics

and health research in South Africa. South African

Medical Journal, 86, 1257–1262.

Flisher, A.J. (1998). Guiding aspirations of epidemio-

logical research in adolescent risk behaviour in the

Department of Psychiatry, University of Cape Town.

Southern African Journal of Child and Adolescent

Mental Health, 10, 140–154.

Flisher, A.J., Evans, J., Muller, M., & Lombard, C. (in

press). Test–retest reliability of self-reported adoles-

cent risk behavior. Journal of Adolescence.

Flisher, A.J., Ziervogel, C.F., Chalton, D.O., Leger,

P.H., & Robertson, B.A. (1996). Risk-taking beha-

viour of Cape Peninsula high-school students: Part

IX. Evidence for a syndrome of adolescent risk

behaviour.

South

African

Medical

Journal,

86,

1090–1093.

Gordon, W.R., & Caltabiano, M.L. (1996). Urban–rural

differences

in

adolescent

self-esteem,

leisure

boredom, and sensation-seeking as predictors of

leisure-time usage and satisfaction. Adolescence,

31, 883–901.

Grotevant, H.D. (1998). Adolescent development in

family contexts. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of

child psychology (5th edn): Vol. 3. Social, emotional

and personality development (pp. 1097–1149). New

York: John Wiley & Sons.

Harter, S. (1998). The development of self-representa-

tions. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child

psychology (5th edn): Vol. 3. Social, emotional and

personality development (pp. 553–617). New York:

John Wiley & Sons.

Hockaday, C., Crase, S.J., Shelley, M.C. II, & Stockdale,

D.F. (2000). A prospective study of adolescent preg-

nancy. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 423–438.

Ho

¨fler, M., Lieb, R., Perkonigg, A., Schuster, P., Sonn-

tag, H., & Wittchen, H.-U. (1999). Covariates of

cannabis use progression in a representative popula-

tion sample of adolescents: A prospective examina-

tion of vulnerability and risk factors. Addiction, 94,

1679–1694.

Howard, M.O., & Jenson, J.M. (1999). Inhalant use

among antisocial youth: Prevalence and correlates.

Addictive Behaviors, 24, 59–74.

Howard, M.O., Walker, R.D., Walker, P.S., Cottler, L.B.,

& Compton, W.M. (1999). Inhalant use among urban

American Indian youth. Addiction, 94, 83–95.

Jang, S.J., & Thornberry, T.P. (1998). Self-esteem,

delinquent peers, and delinquency: A test of the

self-enhancement

thesis.

American

Sociological

Review, 63, 586–598.

Jessor, R. (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: A

psychosocial

framework

for

understanding

and

action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12, 597–605.

Jessor, R., Van den Bos, J., Vanderryn, J., Costa, F.M.,

& Turbin, M.S. (1995). Protective factors in adoles-

cent problem behavior: Moderator effects and devel-

opmental change. Developmental Psychology, 31,

923–933.

Kaplan, H.B. (1975). Self-attitudes and deviant behav-

ior. Pacific Palisades, CA: Goodyear.

Kawabata, T., Cross, D., Nishioka, N., & Shimai, S.

(1999). Relationship between self-esteem and smok-

ing behavior among Japanese early adolescents:

Initial results from a three-year study. Journal of

School Health, 69, 280–284.

Kingsbury, S., Hawton, K., Steinhardt, K., & James, A.

(1999). Do adolescents who take overdoses have

specific psychological characteristics? A comparative

study with psychiatric and community controls.

Journal of the American Academy of Child and

Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 1125–1131.

Koval, J.J., & Pederson, L.L. (1999). Stress-coping and

other psychosocial risk factors: A model for smoking

in Grade 6 students. Addictive Behaviors, 24, 207–

218.

Self-esteem and adolescent risk behaviours

1465

Koval, J.J., Pederson, L.L., Mills, C.A., McGrady, G.A.,

& Carvajal, S.C. (2000). Models of the relationship of

stress, depression, and other psychosocial factors to

smoking behavior: A comparison of a cohort of

students in Grades 6 and 8. Preventive Medicine,

30, 463–477.

McGee, R., & Williams, S. (2000). Does low self-esteem

predict health compromising behaviors among ado-

lescents? Journal of Adolescence, 23, 569–582.

Neumark-Sztainer, D., Story, M., French, S.A., &

Resnick, M.D. (1997). Psychosocial correlates of

health compromising behaviors among adolescents.

Health Education Research, 12, 37–52.

Nunnally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric

theory (3rd edn). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Paul, C., Fitzjohn, J., Herbison, P., & Dickson, N.

(2000). The determinants of sexual intercourse before

age 16. Journal of Adolescent Health, 27, 136–147.

Pitka

¨nen, T. (1999). Problem drinking and psycholo-

gical well-being: A five-year follow-up study from

adolescence to young adulthood. Scandinavian Jour-

nal of Psychology, 40, 197–207.

Poikolainen, K., Tuulio-Henriksson, A., Aalto-Seta

¨la

¨, T.,

Marttunen, M., & Lo

¨nnqvist, J. (2001). Predictors of

alcohol intake and heavy drinking in early adulthood:

A 5-year follow-up of 15–19-year-old Finnish adoles-

cents. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 36, 85–88.

Roberts, R.E., Roberts, C.R., & Chen, Y.R. (1998).

Suicidal thinking among adolescents with a history

of attempted suicide. Journal of the American Aca-

demy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 1294–

1300.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York:

Basic Books.

Scheier, L.M., Botvin, G.J., Griffin, K.W., & Diaz, T.

(2000). Dynamic growth models of self-esteem and

adolescent alcohol use. Journal of Early Adolescence,

20, 178–209.

Statistics South Africa (2003). Census 2001 databases.

[On-line]. Retrieved October 10, 2003, from http://

www.statssa.gov.za/SpecialProjects/Census2001/

Census/Database/Census%202001/Municipality%20

Level/Persons/Persons.asp.

Sweeting, H., West, P., & Richards, M. (1998). Teenage

family life, lifestyles and life chances: Associations

with family structure, conflict with parents and joint

family activity. International Journal of Law, Policy

and the Family, 12, 15–16.

Vella, M.L., Persic, S., & Lester, D. (1996). Does self-

esteem predict suicidality after controls for depres-

sion? Psychological Reports, 79, 1178.

West, P., & Sweeting, H. (1997). ‘Lost souls’ and ‘rebels’:

A challenge to the assumption that low self-esteem

and unhealthy lifestyles are related. Health Educa-

tion, 5, 161–167.

Wild, L.G., Flisher, A.J., Bhana, A., & Lombard, C.

(2002a). Reliability of the Self-Esteem Questionnaire

for use with South African adolescents (Abstract).

South African Journal of Psychiatry, 8, 50–51.

Wild, L.G., Flisher, A.J., Bhana, A, & Lombard, C.

(2002b). Self-esteem and risk behaviours in South

African adolescents (Abstract). South African Journal

of Psychiatry, 8, 51.

World Health Organization (WHO). (1993). The health of

young people: A challenge and a promise. Geneva:

Author.

Yoder, K.A. (1999). Comparing suicide attemptors,

suicide ideators, and nonsuicidal homeless and

runaway adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening

Behavior, 29, 25–36.

Zeger, S.L., & Liang, K.Y. (1986). Longitudinal data

analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Bio-

metrics, 42, 121–130.

Manuscript accepted 23 October 2003

Appendix: Items assessing risk behaviours

This part of the questionnaire is concerned with the use of tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs.

1.

Have you ever smoked a whole cigarette?

IF YES:

a.

How old were you when you smoked a whole cigarette for the first time?

b.

In the past year have you smoked a whole cigarette?

c.

During the past month, on how many days did you smoke cigarettes?

d.

During the past month, on the days you smoked, how many cigarettes did you smoke per day?

2.

Have you ever used alcohol (including beer and wine), other than a few sips?

IF YES:

a.

How old were you when you used alcohol for the first time, other than a few sips?

b.

In the past year, did you use alcohol other than a few sips?

c.

During the past month, on how many days did you have at least one drink of alcohol?

d.

During the past 14 days, on how many days did you have 5 or more drinks on one occasion?

3.

Have you ever smoked dagga on its own?

IF YES:

a.

How old were you when you smoked dagga on its own for the first time?

b.

In the past year, did you smoke dagga on its own?

c.

During the past month, on how many days did you smoke dagga on its own?

4.

Have you ever smoked dagga and Mandrax together (‘white pipes’, ‘buttons’)?

IF YES:

1466

Lauren G. Wild et al.

a.

How old were you when you smoked dagga and Mandrax together for the first time?

b.

In the past year, did you smoke dagga and Mandrax together?

c.

During the past month, on how many days did you smoke dagga and Mandrax together?

5.

Have you ever sniffed glue, petrol or thinners?

IF YES:

a.

How old were you when you sniffed glue, petrol or thinners for the first time?

b.

In the past year, did you sniff glue, petrol or thinners?

c.

During the past month, on how many days did you sniff glue, petrol or thinners?

6.

Have you ever used crack cocaine?

IF YES:

a.

How old were you when you used crack cocaine for the first time?

b.

In the past year, did you ever use crack cocaine?

c.

During the past month, on how many days did you use crack cocaine?

7.

Have you ever used Ecstasy?

IF YES:

a.

How old were you when you used Ecstasy for the first time?

b.

In the past year, did you ever use Ecstasy?

c.

During the past month, on how many days did you use Ecstasy?

8.

Have you ever used any other type of illegal drug, such as cocaine, heroin, stimulants, hallucinogenics

such as LSD, Nexus, MMDA?

9.

Have you ever injected any illegal drug (i.e., mainlining)?