INTERNET USERS: PERSONALITY, PATHOLOGY, AND RELATIONSHIP

SATISFACTION

by

RUSSELL FARR SHEARER, JR.

(Under the Direction of Richard Marsh)

ABSTRACT

The current study tries to clarify what Axis I / Axis II symptoms are associated with different

types of internet use. Quality of life and relationship satisfaction were secondary measures of

association. Participants answered anonymous online questionnaires about their online

behaviors, Axis I symptoms, quality of life, personalities, relationship satisfaction, and internet

addiction. The questionnaires were disseminated via the internet through ads placed on blogs,

dating sites, message boards, and sex themed communities. The sample totaled 163 unique

users, some of whom did not complete all of the questionnaires, but were included in the

analyses of the questionnaires they completed. The current study was successful in showing that

as time spent on certain uses of the internet increases, so does the existence of more detrimental

Axis I symptoms and the existence of aspects of Axis II personality styles. The participants who

spend the most time on the internet involved in activities that could be carried out in real life

instead seem to have the most problematic personalities and symptom profiles. This may be due

to the ease with which they can exist on the internet rather than in real life. Implications of the

current study and future directions are discussed.

INDEX WORDS:

Internet users, Internet, Cybersex, Personality, Online Sexual Activities,

Internet Addiction, Quality of Life, Relationship Satisfaction

INTERNET USERS: PERSONALITY, PATHOLOGY, AND RELATIONSHIP

SATISFACTION

by

RUSSELL FARR SHEARER, JR.

B.S., The University of Georgia, 2000

M.S., The University of Georgia, 2004

A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial

Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

ATHENS, GEORGIA

2009

© 2009

Russell Farr Shearer, Jr.

All Rights Reserved

INTERNET USERS: PERSONALITY, PATHOLOGY, AND RELATIONSHIP

SATISFACTION

by

RUSSELL FARR SHEARER, JR.

Major Professor:

Richard Marsh

Committee:

Joshua Miller

Sarah Fisher

Electronic Version Approved:

Maureen Grasso

Dean of the Graduate School

The University of Georgia

May 2009

iv

DEDICATION

To my parents: Who always pushed me to fulfill my potential in all endeavors. Who

have always fostered my interests and ideas throughout my childhood and more recent

adulthood. I can always count on them to inspire me, support me, and listen. I want to thank

them for raising me in an environment rich with possibilities and appreciative of the search for

knowledge.

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I want to thank my major professor, Rich Marsh, who has stuck by me for many long

years as I progressed through graduate school. I would also like to thank Josh Miller and Sarah

Fischer, my committee members, for giving me their valuable time.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS......................................................................................................... v

LIST OF TABLES..........................................................................................................................vii

CHAPTER

1

INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 1

Purpose and Past Research..................................................................................... 1

2

INTERNET USERS: PERSONALITY, PATHOLOGY,

AND RELATIONSHIP SATISFACTION ............................................................... 14

The Current Study ............................................................................................... 14

3

RESULTS ............................................................................................................... 18

4

DISCUSSION.......................................................................................................... 32

REFERENCES ......................................................................................................................... 44

vii

LIST OF TABLES

Page

Table

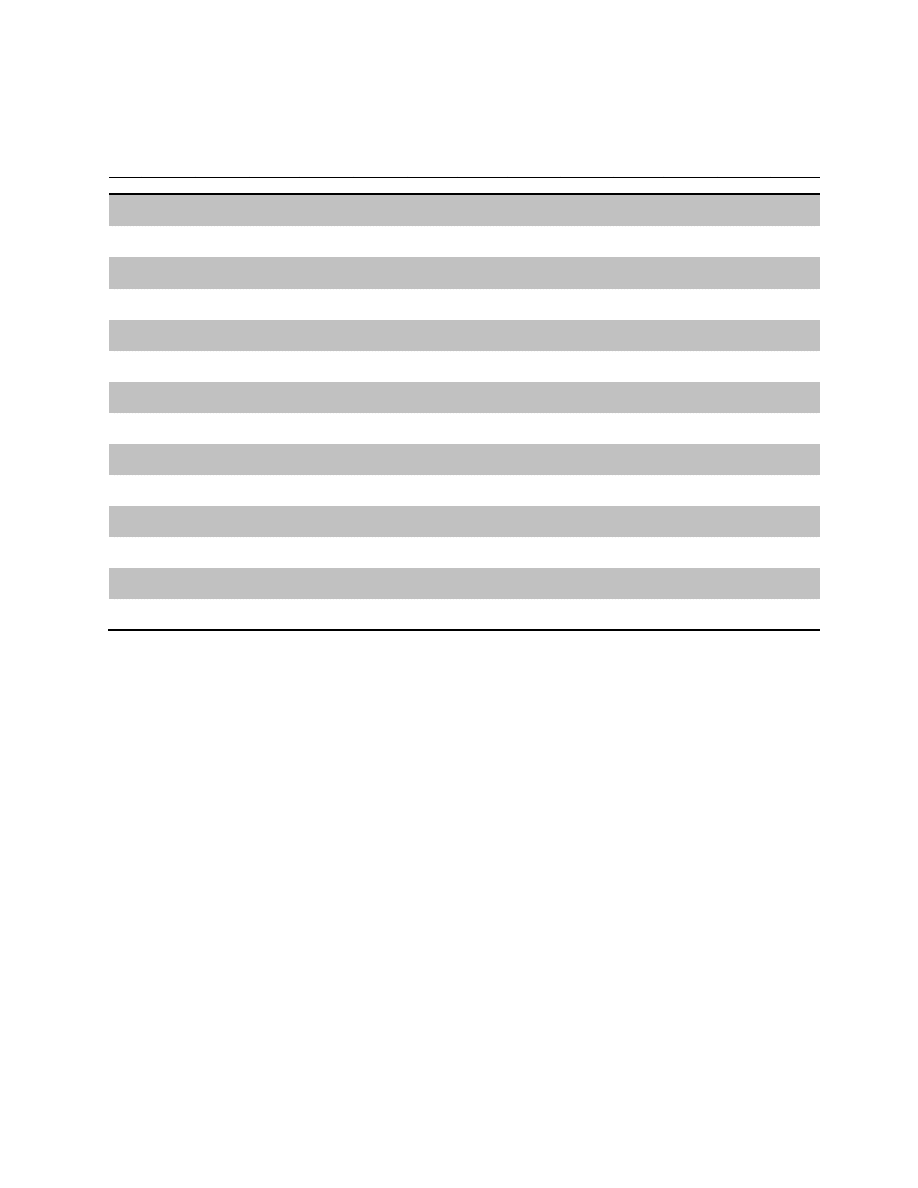

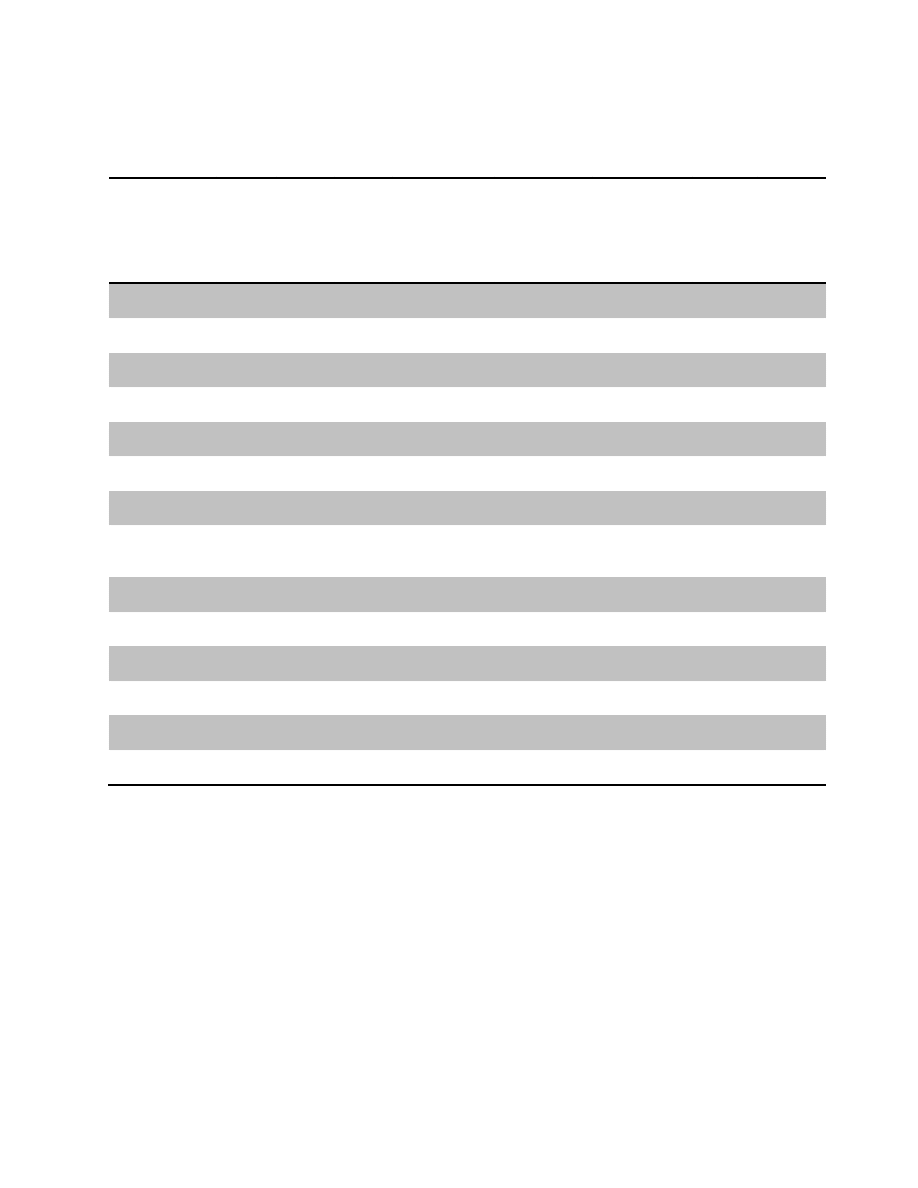

3.1: Correlations of Factors with Type of Online Activities (yes/no) ................................... 19

Table

3.2: Correlations of Facets with Types of Online Activities ................................................ 21

Table

3.3: Correlations of Factors with Hours Spent Engaged in Online Activities ....................... 23

Table

3.4: Correlations of Facets with Hours Spent Engaged in Online Activities ........................ 25

Table

3.5: Correlations of Behavioral Symptoms with Hours Spent Engaged in Online

Activities ...........................................................................................................

........... 27

Table

3.6: Correlations of Hours Spent Engaged in Online Activities with Quality of Life and

Relationship Satisfaction .................................................................................

.............. 28

Table

3.7: Correlations of Factors with Internet Addiction Test Scores......................................... 29

Table

3.8: Correlations of Facets with Internet Addiction Test Scores .......................................... 30

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

Purpose and Past Research

In the ever expanding world of communications, the internet has emerged as a major

method of connecting people along with other history making inventions such as the radio,

telegraph, telephone, television, and cell phone. As of December 2005, 203,824,428 people in

the United States are internet users based on Nielson ratings (http://www.internetworldstats.com/

america.htm#us). Thus, over half (e.g., 68%) of the U.S. population has access to the internet.

The internet is used for many different reasons by many different types of people, but little is

known about the personalities of the users themselves aside from a few studies on internet

addiction and problematic internet use (e.g., Amichai-Hamburger, Wainapel, & Fox, 2002;

Aviram, & Amichai-Hamburger, 2005; Benotsch, Kalichman, & Cage, 2002; Caplan, 2007;

Cooper, Delmonico, & Burg, 2000; Cooper, Delmonico, Griffin-Shelley, 2004; Young, 1996,

2001). The current study seeks to identify personality factors that characterize people who use

the internet for different activities such as users who go online for work, users who seek out non-

sexual recreation online, users who seek dating partners online, users who engage in online

sexual activities (OSAs), and users who meet people online and later engage in real life casual

(e.g., non-relationship / anonymous) sexual activities with them, both for compulsive users and

non-compulsive users within each online activity. A second goal of the current study is to

investigate the associated psychological symptoms, be they relationship difficulties, quality of

2

life problems, or experienced psychological symptoms, for internet users according to their

online activities in an effort to disambiguate many of the prior studies on internet users.

The internet is used in many different ways – websites offer entertainment and

information, e-mail and chat programs offer interpersonal communication, music and programs

are distributed via downloading, pictures are shared, videos are watched, finances are managed,

and relationships are formed. Communicating through electronic mail in order to maintain

personal relationships is the main way people use the internet (Bargh & McKenna, 2004).

Trends in internet use have recently changed. Along with e-mail, there are several other ways

people create and maintain personal relationships on the internet. Chat programs such as ICQ,

Yahoo Instant Messenger, mIRC, MSN messenger, and AOL instant messenger offer real time

interaction to users who type messages to each other. Websites such as web-logs or “blogs” now

allow people to stay in touch via comments on posts about topics ranging from personal journals,

politics, to human sexuality with almost any other unmentioned topic available somewhere.

Services such as facebook.com and myspace.com are being used by thousands of adults,

adolescents, and children as a networking community. Another large portion of the interpersonal

internet is devoted to dating and personal ads. Sites such as eHarmony.com, Match.com,

Friendfinder.com, Craigslist.com, and Adultfriendfinder.com allow people to post personal

information in hopes of finding dates, establishing relationships, or meeting others for

recreational sex.

Studies focusing on the possible detrimental effects of the internet have been conducted

by a handful of researchers. In 1998, Kraut and colleagues conducted a two-year longitudinal

study of the effects of internet usage on personal relationships. The initial conclusions reached

suggest that people who had no prior home access to the internet, but were given a computer and

3

internet access, had small increases in reported depression and loneliness. Thus, transitioning

from no internet use to accessing the internet in the home can result in personally detrimental

results.

A potentially dangerous aspect of the internet is the ability for individuals to remain

anonymous online. A person never knows for sure with whom they are interacting via email or a

chat program. It is relatively easy to use the internet to deceive others by relating false

information or sending fake pictures. Users can perpetuate any identity they wish in order to

deceive others. Usually this occurs when a person role-plays a fantasy, such as a middle-aged

man who poses as a woman in her teens to engage in OSAs with men in pedophilia themed chat

rooms, or a woman who pretends to be another user’s mother in incest themed chat rooms.

These activities often occur between fantasizing adults, but sometimes adults use this tactic to

interact with real life children in chat rooms, grooming them over time for real life meetings

(Young, 2001). An outcome of this can be viewed by watching any of the recent investigative

reports on television; there are many stories in the media about undercover operations designed

to ensnare potential pedophiles, rapists, and child molesters (

www.pervertedjustice.com

). The

program invariably shows a constant stream of adult internet users who arrive at a house with a

reporter inside. These men are under the false impression that a child or adolescent with whom

they have chatted online awaits their arrival for a sexual encounter.

The amount of time a user spends online and the degree to which use is compulsive are

important issues in researching online behavior. Behavioral addiction models (

Shaffer, 1996;

Orford, 2001; Lemon, 2002) allow for technology to be considered an addiction (Griffiths, 1996;

1998; Shotton, 1989).

Internet “addicts” are characterized as having an impulse control disorder,

which does not involve an intoxicant (Young, 1996). Similar to other dependencies and impulse

4

control disorders, they meet criteria such as preoccupation with using the internet, increasing the

amounts of time spent online, repeated failed attempts to control, cut back, and stop their online

behaviors, becoming irritable or anxious when attempting to decrease use or to stop using the

internet, using the internet to escape negative feelings such as anxiety, depression, guilt, and

helplessness, lying about their online behavior, and risking relationships, jobs, or education to

engage in online behaviors. Internet addiction also meets criteria of Dependence (American

Psychiatric Association, 2000) such as tolerance and withdrawal, spending more time online than

intended, great amounts of time are spent in attempts to engage in the behavior (i.e., using the

internet at work for the compulsive behavior), and the behavior is continued with an awareness

of its detrimental effects. “Dependent” internet users, as defined by Young and Rodgers (1998)

using modified DSM-IV criteria for Pathological Gambling, meet these criteria. The

personalities of internet users have been investigated in the context of internet addiction using

the above criteria. They were high in self-reliance, emotional sensitivity and reactivity,

vigilance, and they had low self-disclosure, and non-conformist characteristics using the 16PF.

Other studies have shown that “problematic internet use” or “excessive internet use” (Loytsker &

Aiello, 1997; Yang, Choe, Baity, Lee, & Cho, 2005) is associated with higher levels of boredom

proneness, loneliness, social anxiety, private self-consciousness, being affected by feelings,

emotional instability, imaginativeness, tendency to be absorbed in thought, self-sufficiency,

experimenting, and preferring to make their own decisions. There is some overlap between these

studies in regard to self-sufficiency, emotional sensitivity and reactivity, and self-reliance.

Finally, a study by Armstrong, Phillips, and Saling (2000) showed that low self-esteem predicted

increased internet use, while impulsivity did not. Thus the literature pertaining to the individual

5

differences associated with excessive internet usage is both sparse and conflicting; clearly further

study is warranted.

Research has been conducted in some specific areas in which the internet fosters

compulsive use, or “internet addiction,” such as gambling, gaming, and sexual gratification. A

random sample of 7,307 individual internet users yielded results suggesting that 10% of the

internet users went online primarily to fulfill sexual fantasies. These users reported that their

lives were disrupted by sexual thoughts. Compulsive use (i.e., “an irresistible urge to perform an

irrational sexual act” [Cooper, 1998], or “the loss of freedom to choose whether or not to stop or

engage in a behavior” [Schneider, 1994]) has been shown to be present in a small percentage of

this sample, too. Nearly one third of the sample reported a desire to reduce the amount of time

spent in online sexual activity. Within the same sample, 9.2% of users reported that their sexual

behaviors on the internet are “out of control,” and that they cannot stop using the internet even

though they wish to do so (Cooper, et al., 2004). Other studies confirm the percentages of

compulsive cybersex users (Cooper, Delmonico, & Burg, 2000; Cooper, Scherer, Boies, &

Gordon, 1999; Daneback, Cooper, & Mansson, 2005).

When compulsion leaves the cybersexual world and enters real life, there is a greater

likelihood of contracting a sexually transmitted disease among those who continue in online

relationships to the point of actual real life meetings for intercourse (McFarlane, Bull, &

Rietmeijer, 2000). Also, men who use the internet to find same-sex partners may be at increased

risk of contracting HIV due to a higher number of partners, higher rates of unprotected insertive

and receptive anal intercourse, and a higher incidence of methamphetamine use (Benotsch,

Kalichman, & Cage, 2002). While the consequences of sexual behaviors on the individual can

be dire, the real life partners can be affected by these compulsive behaviors, too. Fourteen

6

percent of Cooper’s sample reported that someone, such as a relative or romantic partner, had

complained to them about their online sexual behaviors. Online sexual activities, while not

caused by lower levels of dyadic satisfaction or problems within real life relationships (Aviram

& Amichai-Hamburger, 2005), become problematic when the partner of the cybersex user finds

out about the online infidelity (Schneider, 2000). Schneider’s survey revealed that learning

about a partner’s online sexual activities such as cybersex and viewing pornography led to

feeling hurt, ashamed, betrayed, rejected, isolated, humiliated, lonely, abandoned, jealous, and

angry. However, over half of the cybersex addicts had lost interest in sex with their partner and

the cybersex activities were a major contributing factor to these couples’ subsequent separation

and divorce. Finally, in Cooper’s sample, 10% of users endorsed using the internet for online

sexual activities that they do not commit or desire to commit in real life (see also Young, 2001).

This strengthens the claim made by the aforementioned men who are arrested in undercover

operations targeting child molesters who often say that they “have never done anything like this

before” and have only fantasized about the sex act using the internet (Young, 2000). Their arrest

records confirm that many are first-time offenders. So, the boundaries between the cyber-world

and real life may become blurred with continued online sexual activities.

A potential problem with the research thus far is that it does not take into account what

activities the internet users are engaged in, as opposed to other research on addiction in which

the substance of choice and the types of users (in alcohol research) are investigated and

disambiguated. Because of the many online activities that one can participate in online,

analogous to the many substance use disorders and other compulsive behaviors, there may be

different personality factors driving the goals of users online just as there are different

7

personality factors found across other addictions such as smoking, drinking alcohol, drug use,

gambling, and mobile phone use.

Bianchi and Phillips (2005) found that problematic mobile phone use was associated

negatively with age and extraversion, and positively with low self-esteem. Mobile phone use

was not associated with neuroticism. The users with these risk factors engaged in more illegal

and dangerous mobile phone uses such as using phones in banned areas or while driving,

incurred more debt due to their phone usage, and were more likely to harass or bully others with

their phones by text messaging and placing calls. In a study of pathological gambling, findings

contradict some of those of the mobile phone users in that gamblers had higher scores on

neuroticism, impulsivity and emotional vulnerability, and lower scores on conscientiousness,

self-discipline, and deliberation (Bagby, Bulmash, Costa, Quilty, Toneatto, & Vachon, 2007).

These two studies highlight just the beginning of findings that show that personality factors are

differentially associated with these various factors specific to problematic behaviors.

Substance use is another area of study that on the surface seems cohesive in the

personality literature until one begins to differentiate what types of specific SUDs are being

investigated. Substance use disorders are associated with antisociality, novelty seeking, low

agreeableness, low conscientiousness, disinhibition, conduct disorder, and negative affectivity,

with a more moderate association with overall neuroticism. The most consistent predictors of

substance use disorders (SUDs) are disinhibition or behavioral undercontrol, with extraversion

associated with alcohol use disorders in college age participants, and novelty seeking associated

with smoking (Bartholow, Sher, & Wood, 2000). The association between extraversion and

SUDs was weak, however, and Bartholow et al. posit that the social context in which alcohol use

occurred the most for their college sample is not the same social context the participants find

8

themselves in during adulthood. The findings that different personality factors are associated

with different substance use disorders have been shown in other research as well. Extraversion

and low openness to experience predict alcohol abuse symptoms, low Conscientiousness predicts

drug use, and Openness to experience and low Conscientiousness predict tobacco use (Grekin,

Sher, & Wood, 2006).

Furthermore, Sher, Trull, and Waudby (2004) conclude that cluster B symptom counts

were significant, unique predictors of alcohol and drug use diagnoses. Cluster A counts,

however, were more related to tobacco dependence with levels of oddness, eccentricity, and

introversion being the most significant predictors. Finally, alcohol use was most related to the

specific symptoms of antisocial and borderline personality disorders. AUDs were more strongly

related to borderline symptoms than to the much studied associations with impulsivity-

disinhibition and negative affectivity factors of all SUDs (Sher & Trull 1994; Burr, Durbin,

Minks-Brown, Sher, & Trull, 2000). Consistent with Sher et al., Bottlender, Preuss, and Soyka

(2006) found that there were features of different personality disorder clusters in two types of

alcohol-dependent participants. One type of alcohol user was found to have “an earlier onset of

more severe alcohol-related problems in the context of greater evidence of additional

psychopathology and additional substance use disorders.” These alcohol users had cluster A and

B personality disorders more often, and specifically more borderline, antisocial, and avoidant

disorders.

Not all of the research supports only negative outcomes for internet use. In 2002, Kraut

et al. followed up with participants in the Internet Paradox study (1998) and found that after

three years of use the original negative effects had remitted (Kraut, Kiesler, Boneva, Cummings,

Helgeson, & Crawford, 2002). Instead, internet usage was associated with increases in positive

9

domains such as adjustment and involvement with family and friends. In another study, 95% of

respondents reported no decrease in time spent with family and friends due to internet use and

among the heavy users 88% reported no change in time spent involved in real life personal

relationships (Nie & Erbring, 2000). Other research supports the findings that internet usage in

general does not interfere with personal relationships. Internet users tend to have larger social

networks; can maintain communication with family and friends; and may actually decrease the

amount of time they spend watching television and reading newspapers, but not involved in

social interactions (Bargh & McKenna, 2004). This may be due to the increases in internet use

over the last several years. As more users go online, people are figuring out how to balance this

new technology with other important areas of life.

The potential for anonymous interactions can also lead to positive outcomes for users.

The internet allows people to interact anonymously and can, therefore, be useful and attractive to

those who are more socially anxious or unskilled (Amichai-Hamburger, Wainapel, & Fox, 2002;

Caplan, 2007). These users may be more willing to engage others on the internet because of the

way these relationships are formed. Rather than interactions based on “face to face” meetings,

where physical appearance is the most salient aspect of a first encounter, the internet allows

people to reveal their physical identities over time through the exchange of pictures or the

viewing of web-cams. Thus, the first impression of a person is created on the interaction itself;

the conversation and the exchange of ideas. Only later does the physical appearance of a person

become a factor in the relationship (Amichai-Hamburger, et al., 2002; Bargh, McKenna, and

Fitzsimons, 2002). For people who find real life interactions uncomfortable or anxiety

provoking, this initially anonymous outlet for social interacting can be attractive and promote

more revealing interactions in the future, as the person gains more confidence.

10

In order to maintain a consistent language for this study, defining the activities in which

users engage will be important information. “Work users” will be defined as those people using

the internet for work related activities such as business tasks and emails, school related activities,

and research. “Shopping” users are those people who shop online. “Recreational users” are

those people who use the internet for online gaming, non-sexual video watching, and recreational

reading. “Relationship-seeking users” are those who are online with the goal of finding a serious

dating partner or a future marriage partner. Online sexual activities, or using the medium to

engage in sexually gratifying activities (Cooper, Delmonico, Griffin-Shelley, & Mathy, 2004),

will be subcategorized into three categories. Users engaging in non-interactional OSAs (i.e.,

“Viewing Porn”) are those who view pornographic pictures, videos, and erotica online without

interacting with other users in real time (e.g., chat rooms and webcams) or via email. Internet

users who engage in OSAs that involve interactions with other users are “person to person

OSAs.” They partake in activities such as sexually explicit text based instant messaging (i.e.,

“cybering” or “cyber-sex”), viewing real time video streams of another user via webcam

messaging, or emailing another user sexually explicit messages. The final user type consists of

those individuals who use the internet to find casual sex partners for real life meetings (i.e.,

“seeking people online to meet in real life for sex”). Because various activities likely will be

endorsed by each internet user (i.e., no pure categories of internet use), the amount of time spent

on each activity will be an important aspect of internet usage. Thus, not only will the outcomes

of overall internet use be investigated (i.e., associations between pathology, personality, and

relationship satisfaction and whether a user engaged in a specific type of use), but the amount of

time spent engaged in each activity online will be quantified (average hours per week) and

associated with measures of personality and pathology, both positive and negative.

11

In order to measure the qualities of the users themselves, rather than the associated

psychological symptoms of using the internet alone, personality factors will be useful.

Personality has been found to be long-lasting behavioral patterns that make up the way a person

reacts to various situations, what a person seeks out for entertainment, how a person responds to

stressors, and how a person interacts with others socially. Assessments of general models of

personality such as Costa and McCrae’s NEO Personality Inventory-Revised (1992), based on

the Five Factor Model (FFM), can be used to account for both normal personality and

psychopathological personality disorders as categorized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

of Mental Disorders

(4

th

ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). First, the FFM

is comprised of the five major domains of personality: Neuroticism, Extraversion, Openness to

experience, Agreeableness, and Conscientiousness. According to Costa and McCrae (1992),

Neuroticism “contrasts adjustment or emotional stability with maladjustment or neuroticism.”

Negative affectivity is a primary component of a number of DSM diagnoses such as social

phobia, depression, and various personality disorders and can be represented by high scores on

this scale (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Degrees of sociability and agency are represented by the

Extraversion scale. Characteristics such as “liking people, preferring large groups and

gatherings. . .[being] assertive, active, and talkative” are indicative of high extraversion (Costa &

McCrae, 1992). Openness to Experience relates to curiosity, willingness to entertain new ideas

and values, and a preference for variety. Agreeableness describes interpersonal tendencies such

as altruism, sympathy for others, eagerness to help, and the belief that others will be helpful in

return. Last of the factors, Conscientiousness relates to one’s ability to plan, organize, and carry

out tasks effectively (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Another measure that has been validated against

Costa and McCrae’s NEO Personality Inventory is Johnson’s IPIP-NEO (2000), an online

12

measure allowing the five factors to be assessed as well as thirty facets. The facets of the IPIP-

NEO are named differently, but measure the same qualities as the NEO PI-R. The thirty facet

scales are separated into groups of six in order to make up each of the five factor scales. For

example, the neuroticism factor scale is made up of items that measure Anxiety, Anger,

Depression, Self-Consciousness, Immoderation, and Vulnerability to stress. The Extraversion

factor is broken down into Friendliness, Gregariousness, Assertiveness, Activity Level,

Excitement Seeking, and Cheerfulness. Openness is characterized by Imagination, Artistic

Interest, Emotionality, Adventurousness, Intellect, and Liberalism. Agreeableness relates to

Trust, Morality, Altruism, Cooperation, Modesty, and Sympathy. The Conscientiousness facets

are Self-efficacy, Orderliness, Dutifulness, Achievement Striving, Self-Discipline, and

Cautiousness (Goldberg, Johnson, Eber, Hogan, Ashton, Cloninger, & Gough, 2006).

Thus, the six user types may differ in associated personality factors depending on their

goal of internet use. Also, compulsive use may be associated with more severe or

psychopathological factors than regular, non-addicted users. In addition to the personality

factors under study, psychological symptoms need to be taken into account in order to assess

which users have the most negative psychological associations. In order to assess this,

behavioral symptoms will be useful to assess along with measures of relationship characteristics.

By collecting such data, the current study should help clarify associations of internet use that

have either been overlooked or studied on their own in the past literature (i.e., studies

investigating the association of internet use with depression symptoms solely). Characterizing

the various internet users according to DSM-IV axes I and II symptoms will provide more global

information about the internet users themselves.

13

The specific online activity an internet user engages in regardless of how much time is

spent online may be associated with certain factors and facets of personality; however, due to the

lack of research on non-compulsive internet use and non-sexual internet use, the analyses for

whether or not a user engages in a certain activity will be purely exploratory. The next set of

hypotheses will be made for the time a user spends engaged in each online activity. As time

maintaining relationships increases scores on the Extraversion factor scale will decrease,

consistent with studies targeting mobile phone users who employ cellular phones for the same

ends. As time spent online viewing pornography, engaged in person to person OSAs, and

seeking real life sexual partners online increases, extraversion will decrease; and scores for

immoderation, depression, self-consciousness, and imagination will increase. Quality of life will

likely decrease and psychological symptoms will increase (see studies by Young) as time spent

engage in sexual online activities increases. For work, shopping, and recreation, analyses will be

exploratory due to the lack of research on uses of the internet that are non-sexual in nature.

Finally, for the most studied area in the past, as IAT scores increase (a measure of compulsive

internet use) detrimental psychological symptoms will increase, and quality of life and

relationship satisfaction will decrease. Across user types it is hypothesized that the most

compulsive users (higher IAT scores) will have higher scores on measures of neuroticism and

lower scores of extraversion, similar to past studies of other addictive behaviors cited above. In

addition, facets of personality such as immoderation, depression, self-consciousness, and

imagination will likely be positively correlated with IAT score. There likely will be negative

associations between facets such as friendliness, gregariousness, assertiveness, activity level, and

cheerfulness (i.e., facets of Extraversion) similar to the findings on the 16PF in studies conducted

by Young and Roberts (1998).

14

CHAPTER 2

INTERNET USERS: PERSONALITY, PATHOLOGY,

AND RELATIONSHIP SATISFACTION

The Current Study

Participants

Participants were internet users who frequent web sites related to blogging, dating,

gaming, socialization, and sexual activities. These participants were asked to fill out surveys

upon accessing the participating web sites via advertisements placed on the websites.

The sample was composed of a total of 163 participants. Nineteen percent of participants

were over 40, 41% were between 30 and 40 years of age, and 40% were under 30 years of age.

The mean age of participants was 34 years of age. There were 107 males and 56 females.

Caucasians accounted for 89.6% of the sample, Asians for 1.2%, African Americans for 1.2%,

Latino/a for 1.8%, American Indians for 0.6%, Pacific Islanders for 0.6%, and “other” for 4.9%.

There were 158 participants from the United States of America, 1 from the UK, 2 from Australia,

1 from Italy, and 1 from South America. Heterosexuals accounted for 93.9% of participants,

bisexuals for 4.3%, and homosexuals for 1.8%. Twenty-seven participants were single, never

married, and not dating, 6 were dating multiple people, 25 were dating one person exclusively,

13 were living with an intimate partner but not married, 91 were married, 9 were divorced, 1 was

widowed, and 3 were separated. Four individuals identified as polyamorous (having multiple

romantic partners simultaneously). Participants’ whose incomes were less than $40,000

accounted for 30% of the sample, from $40,000 to $60,000 accounted for 25% of the sample,

15

and over $60,000 accounted for 45% of the sample. The sample ranged from 11 years in school

to 26 years in school, with a mean of 17.63 years in school and a standard deviation of 2.72.

Materials

Participants completed the IPIP-NEO, which is a free-to-use personality measure based

on the Five Factor Model and has been validated against the NEO-PI-R. They also completed a

brief survey of their internet usage, the Internet Addiction Test (IAT), the Dyadic Adjustment

Scale – Satisfaction Subscale (DAS), the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), the Quality of Life

Inventory (QOLI), and a brief demographic questionnaire. The survey data was collected with

computer surveys collected via dissemination on websites, message boards, and an appeal to

participants to send the link to other potential participants via email, blog postings, and through

social networking sites.

The short form IPIP-NEO was created to be an open source, free to use, internet based

personality assessment. It is based on the Five Factor Model and consists of five factors and

thirty facets scales (Johnson, 2000; Goldberg, et al., 2006), and has 120 questions regarding

different aspects of personality. Cronbach’s alpha for the current sample ranged from α = .61 to

α

= .89 for the facets, with a mean alpha of .78. Mean alpha level for the factor scales was 0.86

for the current study. Validity was assessed by correlating the IPIP-NEO with the NEO-PI-R.

The correlations ranged from .78 to .86 for the factors and .64 to .81 for the facets (Johnson,

2000).

The Brief Symptom Inventory (Derogatis & Spencer, 1982) is a 53-item inventory

assessing psychological symptoms found in clinical and nonclinical populations. The test has

nine scales: Somatization, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Phobic

Anxiety, Paranoid Ideation, and Psychoticism. The internal reliability of the BSI measured with

16

Cronbach's alphas range from α = .75 to α = .89 (Boulet and Boss, 1991). Test–retest reliability

coefficients range from r = .68 to r = .91 (Derogatis and Spencer, 1982). The current study

showed alpha levels at 0.96 for the BSI.

The Quality of Life Inventory (Frisch, 1994) consists of 16 items that include domains of

life that have been empirically associated with overall life satisfaction and subjective well-being

(e.g., love, work, play, finances, relationships, recreation, and surroundings). Respondents use a

3-point Likert-type response scale to rate how important each of the 16 domains are to his or her

overall happiness and satisfaction followed by a 7-point Likert-type response scale rating of how

satisfied they are in the area. The QOLI score reflects satisfaction only in those areas of life that

the person considers important. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79 and two-week test–retest reliability

was 0.73 (Frisch, 1994). The alpha reliability measure for the current study was 0.87.

The Dyadic Adjustment Scale – Satisfaction Subscale was validated as a comparable

alternative to the full DAS (Hunsley, Pinsent, Lefebvre, James-Tanner, and Vito, 1995). It

includes ten items related to relationship satisfaction areas such as regret about the relationship,

thoughts of divorce, commitment to one’s partner, and how much partners get along with one

another rated on a Likert-type scale. The Satisfaction Subscale has an alpha coefficient of 0.82.

Chronbach’s alpha for the current study was found to be 0.80.

The Internet Addiction Test was created by Kimberly Young (1996) and investigated

psychometrically by Widyanto and McMurran (2004). It consists of 20 items which participants

are asked to rate on a five-point Likert scale. The items focus on the degree to which internet use

affects participants’ activities of daily living, social life, sleep, productivity, and feelings. As a

person’s score increases, so do the problems the participant experiences as a result of internet

17

use. Scores ranging from 40 – 69 signify frequent problems and 70 – 100 identify participants

with significant problems. Chronbach’s alpha for the IAT of the current study was found to be

0.89.

Procedure

The entirety of the procedure was carried out online via the surveymonky.com survey

hosting website. The participants were instructed to follow a link to the online surveys. Internet

Protocol addresses were catalogued to ensure that answers could be assigned to unique, though

anonymous, participants. The participants first completed a brief demographic questionnaire

detailing their age, race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and chosen major of study. Next, the

participants detailed their internet usage patterns by answering questions about the types of web

sites they frequent, the categories of their internet use (e.g., business, email, dating, sexual

activities, non-sexual social activities, and blogging), time spent on internet use, and any

negative outcomes of usage they perceive. Then, the participants completed the IAT, DAS, BSI,

and QOLI forms. Finally, participants completed the IPIP-NEO.

Analyses

Analyses will be conducted to see if the type of internet use in which a participant

engages (6 user types) and the time spent using the internet are associated with negative

pathology on the BSI, poor relationship satisfaction on the DAS, and unsatisfactory quality of

life on the QOLI. Compulsive use, as reported by participants on the IAT, will be correlated

with user types in order to assess which group of users has a greater likelihood of experiencing

problematic use. Also, compulsive use will be correlated with the BSI, DAS, and QOLI in order

to assess the associations with negative pathology, negative relationship satisfaction, and poor

quality of life.

18

CHAPTER 3

RESULTS

A majority of Ps used the internet for work (96%), shopping (80%), recreation (83%),

and maintaining personal relationships (85%). The other uses investigated in this study were less

frequent; relationship seeking (41%), viewing pornography (50%), person to person OSAs

(39%), and seeking people online to meet in real life for sex (39%).

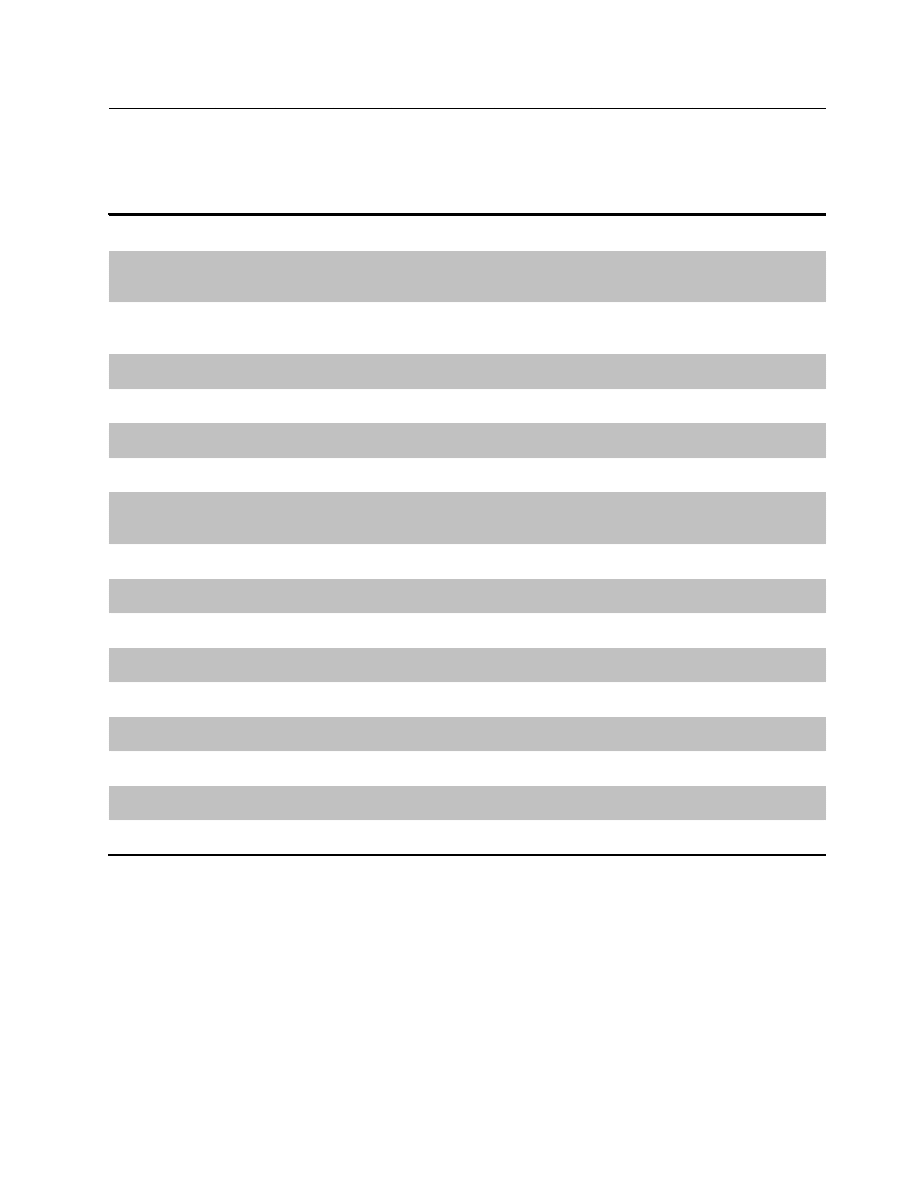

First, correlations between the number of users engaging in each online activity and the

FFM were conducted. This was done to investigate whether or not each use, no matter how

many hours of use were endorsed, was correlated with certain personality factors or facets.

Thus, a participant who endorsed any amount of internet use was coded 1 (yes) for that type of

use, while those denying use in the same category were coded 0 (no) and that variable (yes/no)

was correlated to the factors and facets of personality. The user types were correlated to

determine which activities are significantly related to one another. Also, personality factors were

correlated with one another to investigate the associations between them.

No associations were found for shopping, relationship seeking, or seeking people for sex.

Work use was positively correlated with conscientiousness (r(162) = .23, p < .01). Recreation

was negatively correlated with agreeableness (r(162) = -.289, p < .01). Maintaining personal

relationships was correlated positively with openness (r(162) = .26, p < 01) and negatively with

conscientiousness (r(162) = -.20, p < .01). Viewing pornography was associated negatively with

agreeableness (r(162) = -.20, p < .01) and conscientiousness (r(162) = -.21, p < .01). Person to

Person OSAs was associated negatively with extraversion (r(162) = -.20, p < .01).

19

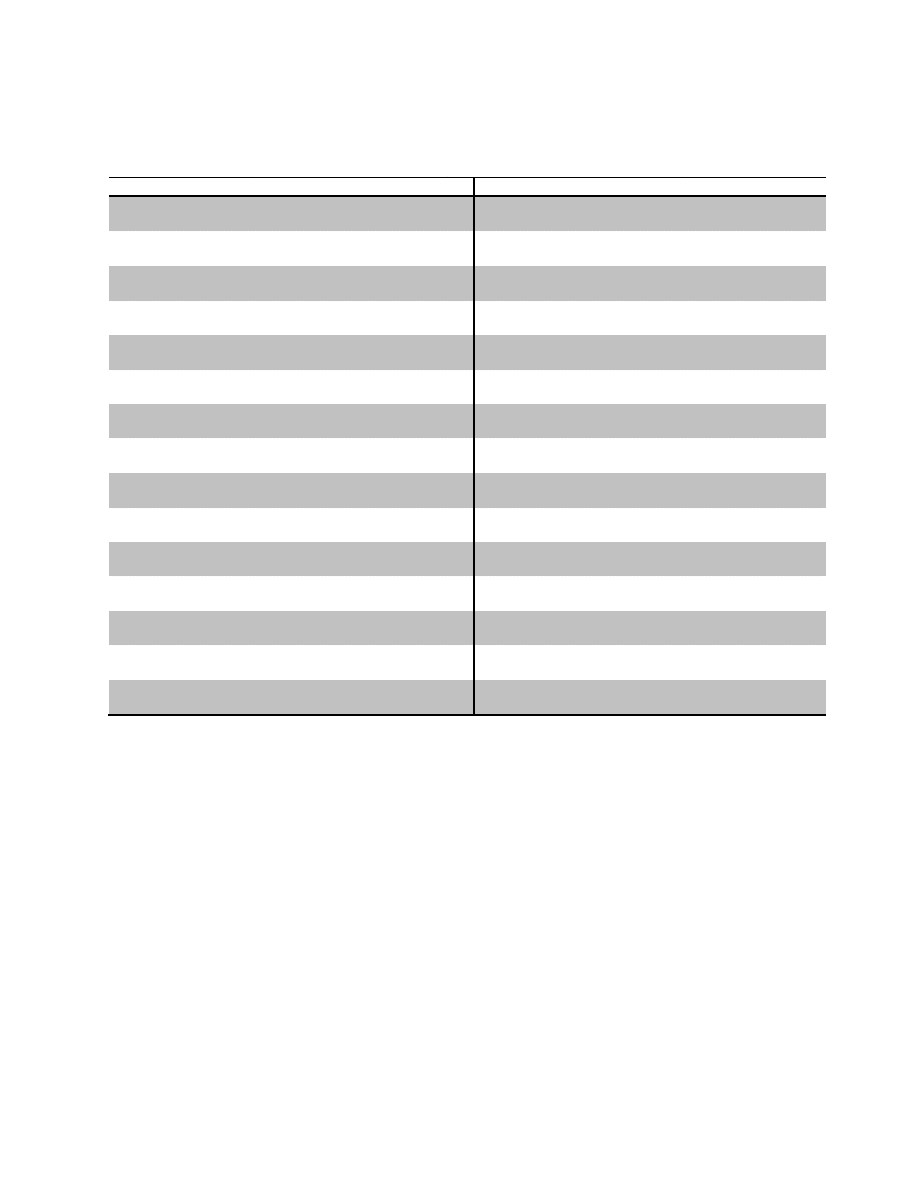

Table 3.1

Correlations of Factors with Type of Online Activities (yes/no)

N

E

O

A

C

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

N

1.000

-.393

**

.098

-.415

**

-.578

**

-.126

.000

.163

.095

.110

.087

.180

.117

E

-.393

**

1.000

.329

**

.337

**

.452

**

.172

-.144

-.140

.021

.005

-.095

-.200

**

-.170

O

.098

.329

**

1.000

.248

**

-.027

.096

-.047

.044

.262

**

.034

.096

.087

.063

A

-.415

**

.337

**

.248

**

1.000

.434

**

.032

-.099

-.286

**

.053

-.104

-.202

**

-.011

.047

C

-.578

**

.452

**

-.027

.434

**

1.000

.231

**

-.034

-.178

-.197

**

-.077

-.209

**

-.128

.001

1

N=157

1.000

.432

**

.099

.196

-.146

.097

-.065

-.106

2

N=131

.432

**

1.000

.166

.177

.035

-.021

-.014

.043

3

N=136

.099

.166

1.000

-.006

.131

.072

-.039

.108

4

N=138

.196

.177

-.006

1.000

-.006

.266

.885

**

.147

5

N=67

-.146

.035

.131

-.006

1.000

.032

-.024

-.017

6

N=81

.097

-.021

.072

.266

.032

1.000

.124

.398

**

7

N=64

-.065

-.014

-.039

.885

**

-.024

.124

1.000

-.023

8

N=64

-.106

.043

.108

.147

-.017

.398

**

-.023

1.000

R2

.24

.05

.17**

.19**

.07

.12**

.38

.12

**p < .01, N=163

N=Neuroticism, E=Extraversion, O=Openness, A=Agreeableness, C=Conscientiousness

1=Work, 2=Shopping, 3=Recreation, 4=Maintaining Relationships, 5=Seeking Relationships, 6=Viewing

Pornography, 7=Person to Person OSAs, 8=Seeking Sex

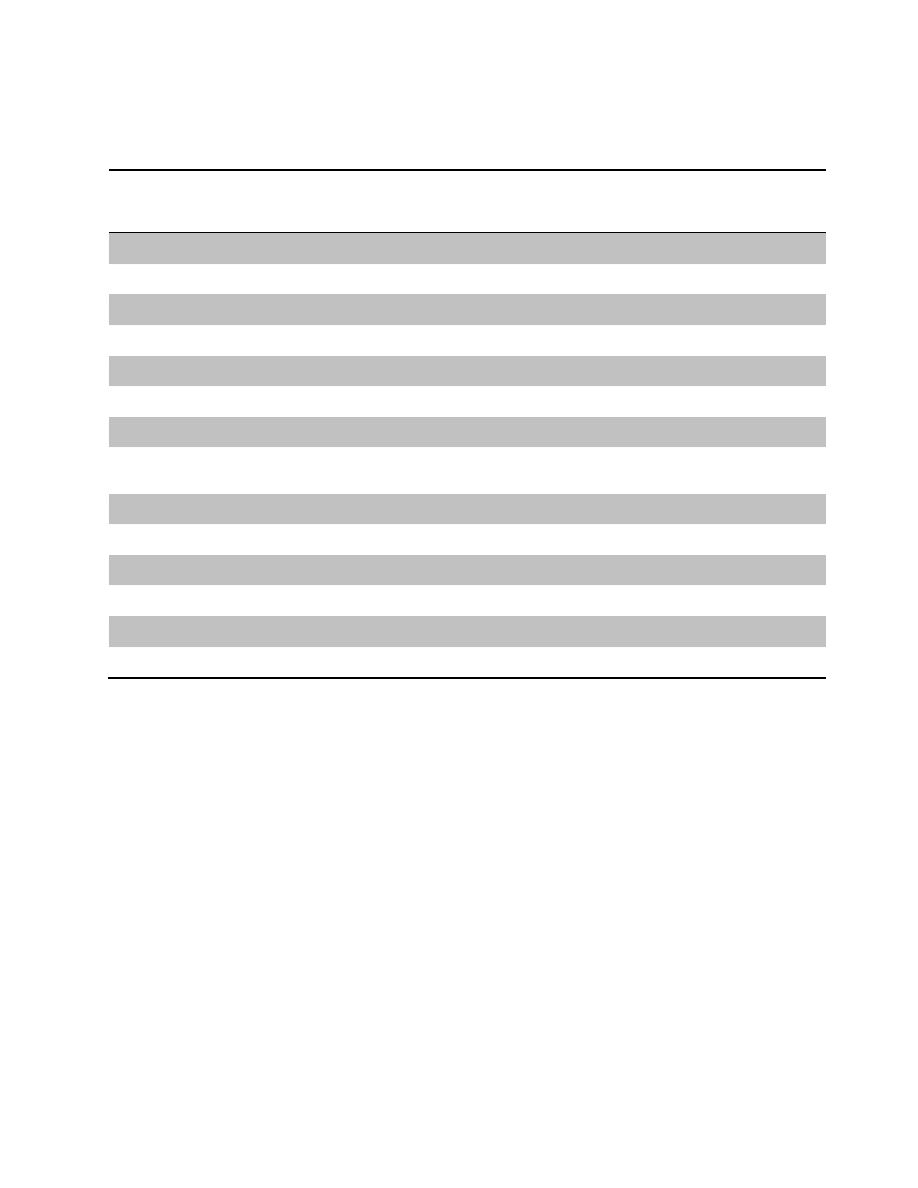

Facet scores were correlated with types of internet use (yes/no). Relationship seeking

was not significantly associated with any facet scores. Work use was positively correlated with

self-efficacy (r(162) = .32, p < .01), assertiveness (r(162) = .21, p < .01), activity level (r(162) =

.19, p < .01), adventurousness (r(162) = .21, p < .01), cooperation (r(162) = .20, p < .01),

achievement striving (r(162) = .27, p < .01), and cheerfulness (r(162) = .19, p < .01). Shopping

was negatively correlated with emotionality (r(162) = -.19, p < .01) and altruism (r(162) = -.29, p

< .01). Recreation was positively correlated with depression (r(162) = .21, p < .01),

immoderation (r(162) = .22, p < .01), and liberalism (r(162) = .19, p < .01); and negatively

20

correlated with friendliness (r(162) = -.22, p < .01), trust (r(162) = -.25, p < .01), altruism (r(162)

= -.18, p < .01), achievement striving (r(162) = -.21, p < .01), modesty (r(162) = -.19, p < .01),

self-discipline (r(162) = -.21, p < .01), cheerfulness (r(162) = -.20, p < .01), and sympathy

(r(162) = -.23, p < .01). Maintaining relationships was positively related to imagination (r(162)

= .20, p < .01), artistic interest (r(162) = .23, p < .01), and emotionality (r(162) = .233, p < .01);

and negatively with orderliness (r(162) = -.25, p < .01). Viewing pornography was positively

correlated with liberalism (r(162) = .25, p < .01); and negatively correlated with morality (r(162)

= -.19, p < .01), achievement striving (r(162) = -.20, p < .01), and self-discipline (r(162) = -.25, p

< .01). Person to person OSAs was positively associated with self-consciousness (r(162) = .21, p

< .01), vulnerability (r(162) = .26, p < .01), and liberalism (r(162) = .20, p < .01); and negatively

correlated to friendliness (r(162) = -.26, p < .01), and self-efficacy (r(162) = -2.1, p < .01).

Seeking people online in order to have real life sex was positively correlated with immoderation

(r(162) = .21, p < .01), and modesty (r(162) = .23, p < .01).

21

Table 3.2

Correlations of Facets with Types of Online Activities

Work

Shop

Rec

Maintaining

Relationships

Relationship

Seeking

Viewing

Pornography

Person

to

Person

OSAs

Seeking

Sex

Anxiety

-.138

.010

.070

.126

.072

.071

.156

.064

Friendliness

.093

-.127

-.224

**

.011

.013

-.129

-.260

**

-.116

Imagination

-.065

.032

.109

.201

**

.116

.080

.073

.043

Trust

-.019

-.017

-.246

**

-.050

-.059

-.122

-.098

-.080

Self Efficacy

.316

**

-.044

-.069

-.154

-.043

-.106

-.213

**

-.053

Anger

-.086

-.083

.109

-.067

.112

-.030

.000

-.029

Gregarious

.024

-.092

-.089

.021

.044

-.022

-.161

-.107

Artistic

Interest

.029

-.063

-.109

.225

**

.014

-.067

.024

.030

Morality

-.036

.001

-.181

.037

-.029

-.192

**

.050

-.019

Orderliness

.106

.055

-.140

-.246

**

-.007

-.154

-.103

.042

Depression

-.074

-.003

.213

**

.108

.156

.172

.177

.179

Assertiveness

.208

**

-.084

-.073

-.081

-.107

-.084

-.146

-.061

Emotionality

-.067

-.188

**

-.085

.233

**

.000

-.178

.100

.143

Altruism

.051

-.291

**

-.184

**

.081

-.089

-.177

.000

.001

**p < .01; N=163; Shop = Shopping, Rec = Recreation

22

Work

N=163

Shop

N=163

Rec

N=163

Maintaining

Relationships

N=163

Relationship

Seeking

N=163

Viewing

Pornography

N=163

Person

to

Person

OSAs

N=163

Seeking

Sex

N=163

Dutifulness

.109

-.081

-.090

-.114

-.031

-.163

-.017

-.097

Self

Conscious

-.116

.131

.092

.024

-.045

-.035

.205

**

.092

Activity

Levity

.188

**

-.058

-.070

.044

.037

-.174

-.047

-.142

Adventurous

.211

**

-.037

-.026

.108

.006

.117

-.093

-.044

Cooperation

.197

**

.054

-.098

-.041

-.070

-.099

.028

.023

Achievement

.267

**

-.022

-.210

**

-.095

-.138

-.202

**

-.119

-.012

Immoderation

.009

.086

.219

**

.113

.092

.141

-.003

.211

**

Excitement

Seeking

.056

-.161

.078

.068

.106

.174

-.071

-.130

Intellect

.138

-.062

.036

.051

-.069

.103

-.051

-.029

Modesty

-.097

-.030

-.191

**

.113

-.080

-.073

-.003

.227

**

Self Discipline

.171

-.063

-.208

**

-.101

-.082

-.247

**

-.164

-.031

Vulnerability

-.134

-.110

.004

.109

.062

.048

.255

**

.006

Cheerfulness

.185

**

-.102

-.197

**

.035

-.074

-.151

-.152

-.179

Liberalism

.102

.111

.194

**

.100

.039

.246

**

.204

**

.068

Sympathy

.016

-.150

-.228

**

.084

-.081

-.154

-.012

.024

Cautiousness

.057

-.027

-.032

-.112

-.031

-.030

.042

.105

R-Square

.27**

.46**

.47**

.41

.32**

.42**

.17

.12

**p < .01; Shop = Shopping, Rec = Recreation

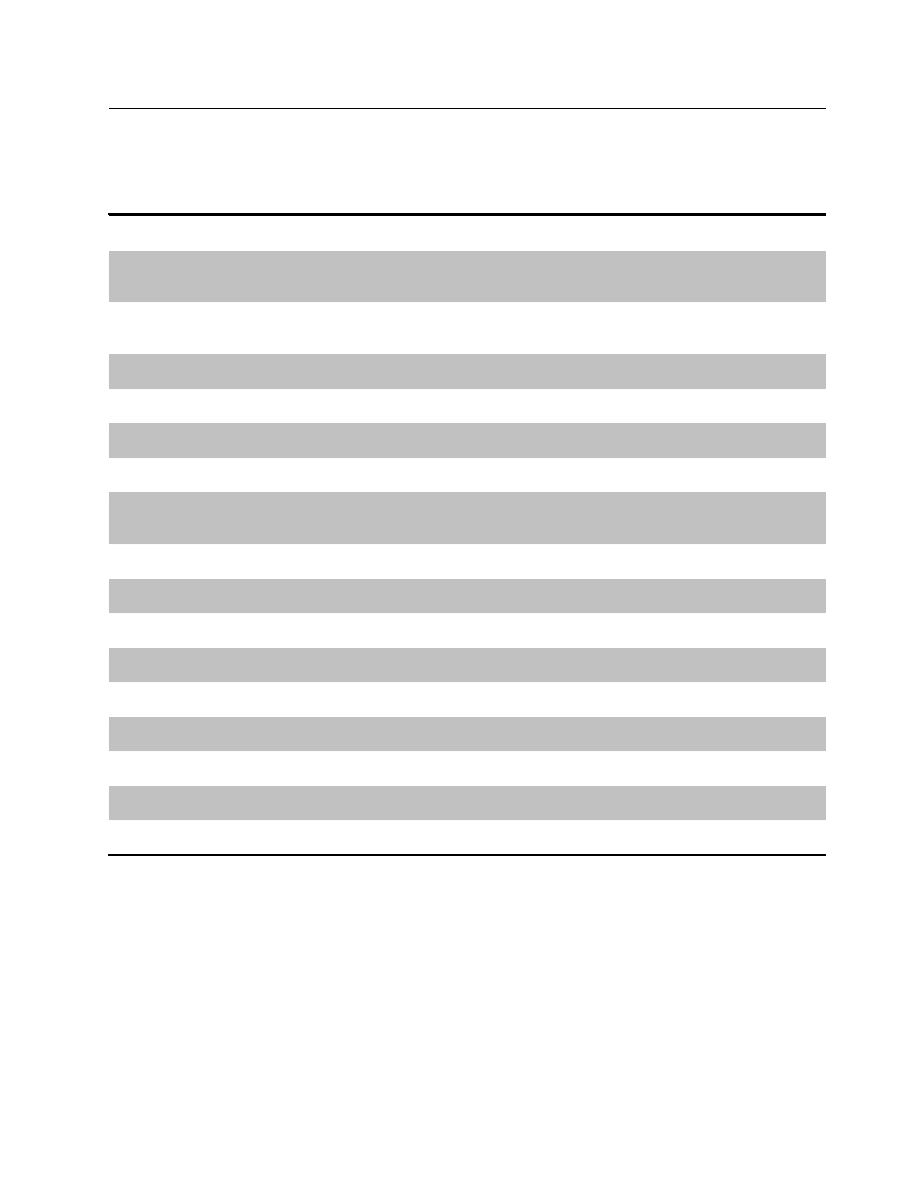

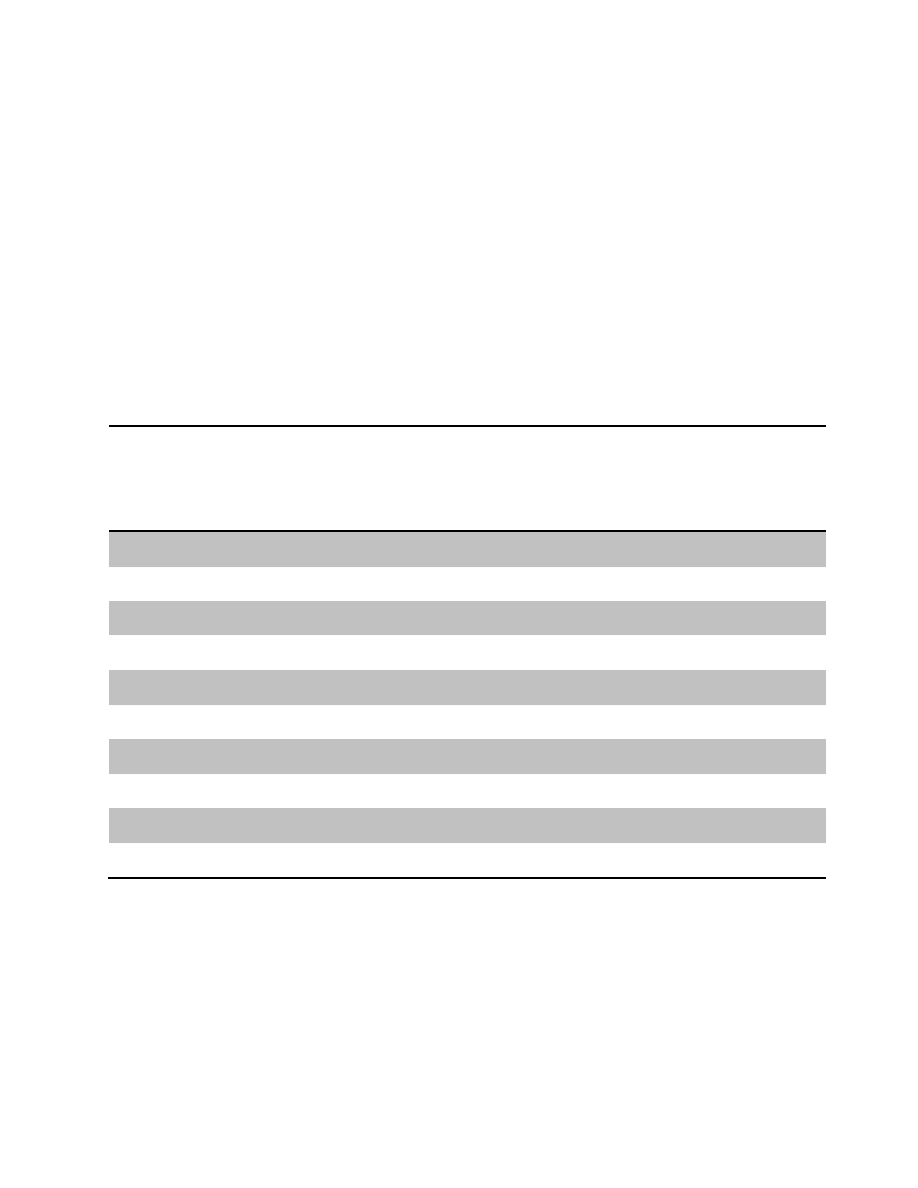

Second, associations between the five factors of personality and the amount of time users

within each user type spent online were analyzed via correlations (i.e., out of people using the

internet for work, the hours they spent online were correlated with personality factors). Time

spent using the internet for work, shopping, viewing pornography, and finding real life sex

23

partners did not significantly correlate with any of the five factors of personality. Users spending

time engaged in recreation online had lower conscientiousness scores (r(135) = -.20, p < .01).

Time spent online maintaining relationships was associated positively with neuroticism (r(137) =

.24, p < .01), negatively with extraversion (r(137) = -.21, p < .01), and negatively with

conscientiousness (r(137) = -.22, p < .01). Time spent seeking relationships online was

associated with higher neuroticism scores (r(66) = .29, p < .01) and lower agreeableness scores

(r(66) = -.38, p < .01). Those who spent more time using the internet for person to person

interactions of a sexual nature were more neurotic (r(63) = .30, p < .01) and less extraverted

(r(63) = -.39, p < .01).

Table 3.3

Correlations of Factors with Hours Spent Engaged in Online Activities

Work

N=157

Shopping

N=131

Recreation

N=136

Maintaining

Relationships

N=138

Relationship

Seeking

N=67

Viewing

Pornography

N=81

Person

to

Person

OSAs

N=64

Seeking

Sex

N=64

N

-.031

.039

.156

.239

**

.285

**

.211

.303

**

.056

E

.010

.116

-.168

-.210

**

-.224

-.197

-.386

**

-.094

O

.155

.002

.036

.012

-.119

.068

-.016

.083

A

.003

.042

-.126

-.043

-.381

**

-.035

-.079

.157

C

.001

.111

-.203

**

-.220

**

-.281

-.222

-.273

.090

R-

Square

.035

.042

.056

.085

.18

.084

.18

.067

**p < .01

N=Neuroticism, E=Extraversion, O=Openness, A=Agreeableness, C=Conscientiousness

Facets of personality were correlated with the hours users spent on each online activity.

Time spent shopping was not correlated significantly with any facets. Time spent working

online was positively correlated with the imagination facet (r(156) = .20, p < .01). Recreation

24

hours were correlated positively with the imagination facet (r(135) = .26, p < .01) and negatively

with self-discipline (r(135) = -.23, p < .01). Time spent maintaining personal relationships was

correlated positively with anxiety (r(137) = .23, p < .01), depression (r(137) = .23, p < .01),

vulnerability (r(137) = .30, p < .01) and negatively with friendliness, (r(137) = .22, p < .01), self-

efficacy (r(137) = -.34, p < .01), achievement striving (r(137) = -.21, p < .01), self-discipline

(r(137) = -.24, p < .01), and cheerfulness (r(137) = -.21, p < .01). Time spent online seeking

romantic relationships was associated negatively with altruism (r(66) = -.44, p < .01),

achievement striving (r(66) = -.36, p < .01), cooperation (r(66) = -.29, p < .01), and sympathy

(r(66) = -.29, p < .01) and positively with imagination (r(66) = .32, p < .01) and depression (r(66)

= .33, p < .01). Hours spent viewing pornography was associated positively with depression

(r(80) = .30, p < .01) and negatively with self-efficacy (r(80) = -.32, p < .01). Time spent

engaged in person to person OSAs was positively correlated with self-consciousness (r(63) = .30,

p < .01) and vulnerability (r(63) = .42, p < .01); and negatively correlated with friendliness (r(63)

= -.43, p < .01), self-efficacy (r(63) = -.46, p < .01), adventurousness (r(63) = -.30, p < .01), self-

discipline (r(63) = -.35, p < .01), and cheerfulness (r(63) = -.31, p < .01). Seeking people online

to meet in real life for sex correlated positively with modesty (r(63) = .32, p < .01).

25

Table 3.4

Correlations of Facets with Hours Spent Engaged in Online Activities

Work

N=157

Shop

N=131

Rec

N=136

Maintaining

Relationships

N=138

Relationship

Seeking

N=67

Viewing

Pornography

N=81

Person

to

Person

OSAs

N=64

Seeking

Sex

N=64

Anxiety

-.049

-.009

.138

.229

**

.143

.227

.276

-.034

Friendliness

-.057

.146

-.123

-.215

**

-.257

-.244

-.426

**

-.004

Imagination

.197

**

.116

.256

**

.030

.317

**

.164

-.007

-.039

Trust

-.032

.001

-.189

-.139

-.135

-.117

-.229

.033

Self Efficacy

.034

.133

-.183

-.342

**

-.184

-.319

**

-.455

**

.112

Anger

-.017

.072

-.060

.093

.282

.080

.106

-.173

Gregarious

-.091

-.011

-.118

-.066

-.165

-.060

-.233

-.074

Artistic

Interest

.158

.011

.026

.029

-.055

-.012

-.038

.096

Morality

.028

.083

-.093

.091

-.220

-.044

.139

.039

Orderliness

.051

.013

-.135

-.103

-.171

-.167

-.184

.156

Depression

.046

.039

.187

.267

**

.326

**

.302

**

.288

.081

Assertiveness

.006

.034

-.200

-.191

-.156

-.206

-.279

.047

Emotionality

.034

.098

.032

.121

-.146

.015

.147

.182

Altruism

.014

.050

-.185

-.046

-.436

**

-.129

-.074

.063

**p < .01; Shop = Shopping, Rec = Recreation

26

Work

N=157

Shop

N=131

Rec

N=136

Maintaining

Relationships

N=138

Relationship

Seeking

N=67

Viewing

Pornography

N=81

Person

to

Person

OSAs

N=64

Seeking

Sex

N=64

Dutifulness

.054

.148

-.059

-.023

-.194

-.136

.007

-.079

Self

Conscious

.035

-.044

.150

.152

.111

.007

.304

**

.251

Activity

Levity

.071

.179

-.185

-.152

-.030

-.075

-.138

-.115

Adventurous

.036

-.110

-.113

-.176

-.182

-.100

-.304

**

-.043

Cooperation

.036

-.032

.034

-.051

-.288

**

.012

-.014

-.030

Achievement

.048

.166

-.193

-.210

**

-.358

**

-.168

-.245

.101

Immoderation

-.009

.160

.098

-.003

.195

.146

-.092

.214

Excitement

Seeking

.071

.113

.044

-.096

-.033

-.021

-.218

-.210

Intellect

.147

.029

-.058

-.131

-.229

.033

-.178

.004

Modesty

-.095

.110

.095

.008

-.131

.119

-.076

.318

**

Self Discipline

.003

.163

-.232

**

-.242

**

-.283

-.213

-.353

**

-.081

Vulnerability

-.037

-.046

.178

.299

**

.172

.118

.423

**

-.024

Cheerfulness

.078

.052

-.126

-.205

**

-.273

-.228

-.311

**

-.038

Liberalism

-.012

-.115

-.018

.128

-.129

.130

.252

.080

Sympathy

.063

-.035

-.157

-.019

-.288

**

.006

-.032

.173

Cautiousness

-.159

-.107

-.066

-.041

.016

-.006

.084

.114

R-Square

.22

.33

.30

.34**

.66**

.31

.69

.66

**p < .01; Shop = Shopping, Rec = Recreation

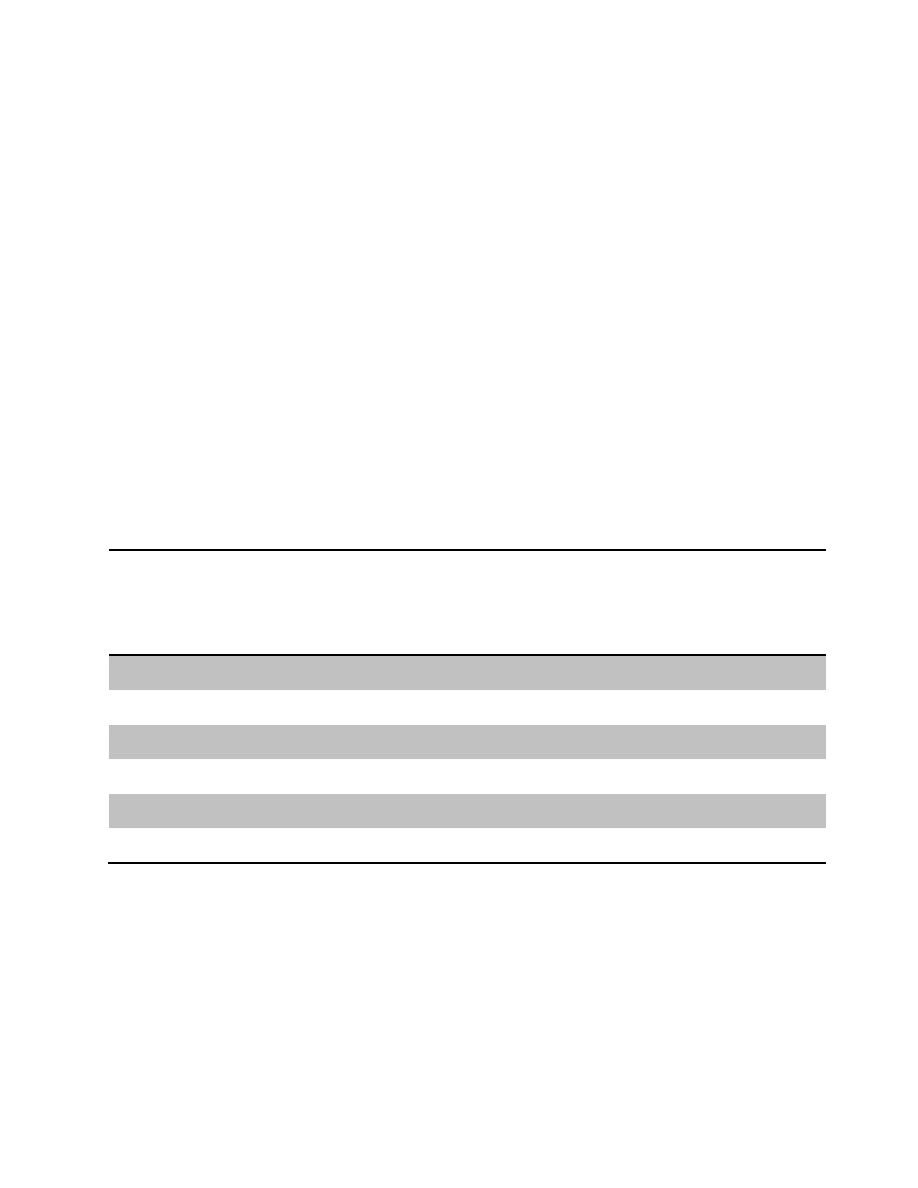

Behavioral symptoms did not correlate with users’ work hours online, hours spent

maintaining relationships, person to person OSAs hours, or hours spent seeking people online to

meet in real life for sex. Time spent on shopping correlated positively with phobic anxiety

(r(130) = .21, p < .01). Hours spent on recreation was positively associated with depression

27

symptoms (r(135) = .26, p < .01), anxiety symptoms (r(135) = .20, p < .01), and phobic anxiety

symptoms (r(135) = .21, p < .01). Time spent seeking relationships online was positively related

to depression (r(66) = .35, p < .01). Hours spent viewing pornography was positively correlated

with interpersonal sensitivity (r(80) = .39, p < .01), depression symptoms (r(80) = .38, p < .01),

and psychoticism (r(80) = .28, p < .01), as well as the Global Severity Index (r(80) = .26, p <

.01).

Table 3.5

Correlations of Behavioral Symptoms with Hours Spent Engaged in Online Activities

Work

N=157

Shop

N=131

Rec

N=136

Maintaining

Relationships

N=138

Relationship

Seeking

N=67

Viewing

Pornography

N=81

Person

to

Person

OSAs

N=64

Seeking

Sex

N=64

SOM

-.062

-.012

-.065

.027

.049

.033

.083

-.057

OC

-.004

-.018

.083

.108

.232

.217

.160

-.092

SENS

-.006

.048

.160

.173

.274

.389

**

.195

.285

DEP

-.099

-.018

.259

**

.192

.354

**

.384

**

.167

.106

ANX

-.039

.141

.201

**

.004

.086

.136

-.044

-.079

HOS

.021

-.007

.010

.027

.236

.165

.072

-.131

PA

.055

.210

**

.205

**

.151

.232

.258

.216

.014

PAR

.041

.087

.052

-.069

.163

.065

-.084

-.078

PSY

-.088

.009

.170

.102

.262

.275

**

.140

.119

GSI

-.036

-.005

.111

.026

.158

.262

**

.028

.049

**p < .01

SOM = Somatic, OC = Obsessive/Compulsive, SENS = Interpersonal sensitivity, DEP = Depression, ANX =

Anxiety, HOS = Hostility, PA = Phobic Anxiety, PAR = Paranoid Anxiety, PSY = Psychoticism, GSI = Global

Severity Index

28

Quality of life was lower as users spent more time engaging in recreation (r135) = -.27, p

< .01) and viewing pornography (r(80) = -.35, p < .01). Relationship satisfaction (DAS) was not

significantly associated with time spent engaged in any types of internet use.

Table 3.6

Correlations of Hours Spent Engaged in Online Activities with Quality Of Life and Relationship Satisfaction

Quality of Life Index

Dyadic Adjustment Scale

Work

-.115

-.029

Shopping

-.104

.083

Recreation

-.265**

.034

Maintaining Relationships

-.192

-.019

Relationship Seeking

-.135

.329

Viewing Pornography

-.347

**

.121

Person to Person OSAs

-.215

-.118

Seeking Sex

-.167

.027

**p < .01

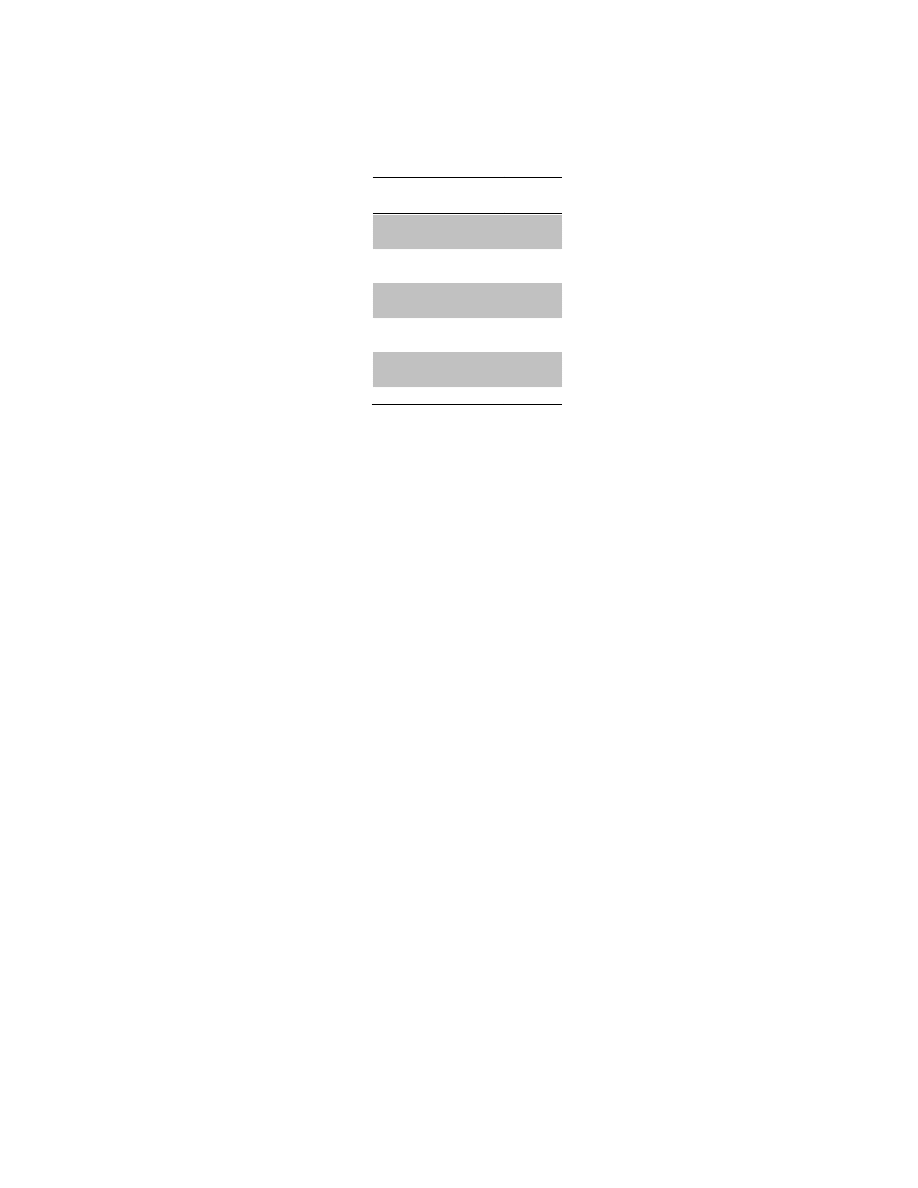

Compulsive use of the internet was measured by the IAT (Young, 1996) and correlated

with the personality factors, facets, BSI, QOLI, and DAS to investigate the associations between

subjective excessive use of the internet and other variables. Overall IAT score, the degree to

which Ps identified themselves as having problems resulting from internet use, were positively

correlated with the neuroticism factor (r(162) = .27, p < .01) of personality. Participants IAT

scores were negatively correlated with extraversion (r(162) = -.27, p < .01), agreeableness

(r(162) = -.29, p < .01), and conscientiousness (r(162) = -.39, p < .01).

29

Table 3.7

Correlations of Factors with Internet Addiction Test Scores

IAT

N=163

Neuroticism

.270**

Extraversion

-.265

**

Openness

.123

Agreeableness

-.292

**

Conscientiousness

-.392

**

R-square

.23**

**p < .01

Overall IAT scores correlated positively with personality facets imagination(r(162) = .29,

p < .01), depression (r(162) = .31, p < .01), self-consciousness (r(162) = .23, p < .01), and

immoderation (r(162) = .24, p < .01). IAT scores were negatively associated with friendliness

(r(162) = -.33, p < .01), trust (r(162) = -.30, p < .01), self-efficacy (r(162) = -.31, p < .01),

gregariousness (r(162) = -.20, p < .01), morality (r(162) = -.22, p < .01), orderliness (r(162) = -

.32, p < .01), altruism (r(162) = -.27, p < .01), activity level (r(162) = -.20, p < .01), achievement

striving (r(162) = -.31, p < .01), self-discipline (r(162) = -.42, p < .01), cheerfulness (r(162) = -

.22, p < .01), and sympathy (r(162) = -.21, p < .01).

30

Table 3.8

Correlations of Facets with Internet Addiction Test Scores

IAT

IAT

Anxiety

.159

Self Conscious

.230

**

Friendliness

-.326

**

Activity Levity

-.200

**

Imagination

.291

**

Adventurous

-.048

Trust

-.297

**

Cooperation

-.159

Self Efficacy

-.314

**

Achievement

-.309

**

Anger

.074

Immoderation

.240

**

Gregarious

-.196

**

Excitement Seeking

-.008

Artistic Interest

.008

Intellect

.034

Morality

-.218

**

Modesty

-.016

Orderliness

-.320

**

Self Discipline

-.415

**

Depression

.305

**

Vulnerability

.176

Assertiveness

-.152

Cheerfulness

-.223

**

Emotionality

-.030

Liberalism

.143

Altruism

-.266

**

Sympathy

-.214

**

Dutifulness

-.151

Cautiousness

-.159

**p < .01, N=163

R-square = .40**

Behavioral symptoms (BSI) were correlated with the IAT scores of participants to see if

higher IAT scores were associated with higher numbers of symptoms. IAT scores were

correlated positively with obsessive compulsive symptoms (r(162) = .21, p < .01), interpersonal

sensitivity (r(162) = .30, p < .01), depression symptoms (r(162) = .34, p < .01), phobic anxiety

symptoms (r(162) = .20, p < .01), paranoia (r(162) = .22, p < .01), psychoticism (r(162) = .40, p

< .01), and the Global Severity Index (r(162) = .22, p < .01).

31

Finally, IAT scores were correlated with quality of life (QOLI) and dyadic adjustment

(DAS). IAT scores negatively correlated with quality of life (r(162) = -.36, p < .01), but not with

dyadic adjustment.

The IAT can also be split into three groups (Widyanto & McMurran, 2004) according to

the range of scores the Ps indicate on the survey (i.e., low IAT score (IAT1), frequent problems

due to internet use (IAT2), and significant problems due to internet use (IAT3)). ANOVA

designs were utilized to investigate whether or not there are differences between the three groups

of IAT scores and factors, quality of life, dyadic adjustment, and behavioral symptoms.

No main effects were found for IAT categories across dyadic adjustment score (DAS) or

for any of the behavioral symptom scores (BSI symptom indices). Thus, no further comparisons

were conducted.

IAT categories were compared across factors of personality. There was a main effect for

agreeableness (F(161) = 4.34, p < .01), and conscientiousness (F(161) = 9.92, p < .01).

Significant differences for agreeableness were found between IAT1 (x = 95.27) and IAT2

(x = 88.76) but not between IAT1 and IAT3, or IAT2 and IAT3. For conscientiousness,

significant differences were found between IAT1 (x = 94.68) and IAT2 (x = 85.39), IAT1 (x =

94.68) and IAT3 (x = 66), and IAT2 (x = 85.39) and IAT3 (x = 66).

For quality of life, a main effect was found for IAT score (F(161) = 8.26, p < .01).

Differences were found between IAT1 (x = 3.04) and IAT2 (x = 2.21), IAT1 (x = 3.04) and

IAT3 (x = -.28), and IAT2 (x = 2.21) and IAT3 (x = -.28).

32

CHAPTER 4

DISCUSSION

This study attempted to examine the personality factors and facets that are associated

with the various uses of the internet. Another objective of the study was to investigate what

behavioral pathologies are associated with each type of internet use and if the time spent

involved in each internet activity was associated with quality of life and relationship satisfaction.

The five factor model was used in order to measure the associations between time spent using the

internet for work, shopping, recreation, maintaining personal relationships, relationship seeking,

viewing pornography, person to person OSAs, and seeking people to meet in real life for sex

with each of five factors of personality (e.g., neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness,

and conscientiousness) and each of 30 facets. In the past, many studies have investigated

internet use with the intention of associating overall use with various problems such as

introversion, depression, addiction, infidelity, loneliness, and sexual compulsion. However, little

research has been done on the users themselves or what people are using the internet for, only on

the supposed outcomes of using the internet. The current study sought to add to this body of

research by seeing what types of people are engaging in each online behavior and what

behavioral symptoms, life adjustment outcomes, and relationship repercussions, are associated

with each use. If certain personality factors and facets are associated significantly with certain

types of online behaviors and the degree to which users are engaged in those activities, and if

those behaviors are also associated with negative symptoms (behavioral, quality of life, and

33

relationship satisfaction), more knowledge about who is using the internet for what purpose and

at what cost will be available.

Addiction researchers have only recently begun to think about internet use and the

potential for abuse or addiction (Young, 1996, 2000, 2001; Yang, et al., 2005; Young, &

Rodgers, 1998; and Young, et al., 2000). Indeed, there is much controversy regarding internet

use as a potential addictive medium, but studies suggest that increased internet use is associated

with increased sexual problems, relationship problems, and negative psychological symptoms

similar to the research on other addictive behaviors, such as alcohol use, drug use, and gambling.

Again, these findings are narrow in their scope regarding the types of internet use they

investigate (i.e., only asking about overall internet use or sexually themed internet use). This

study sought to disambiguate the types of internet use as well as if the degree to which one

reports difficulties in daily life due to internet use (IAT) are associated with other negative

factors and certain factors of personality.

First, there were significant positive associations between people who endorsed using the

internet for work (not dependent on amount of hours used for work), the internet use endorsed by

the largest percentage of users, and the factor conscientiousness. Work use was also correlated

positively with facets such as self-efficacy, assertiveness, activity level, adventurousness,

cooperation, achievement striving, and cheerfulness. Therefore, using the internet for work

seems to be correlated with aspects of personality that are subjectively positive and helpful.

Work users, as compared to people who do not use the internet for work (although this number

was found to be very minimal), have traits stereotypically indicative of successful employees and

good careers. Hours spent working online (i.e., the hours spent using the internet for work by

people who endorsed using the internet for work) was not associated with any factors of facets,

34

any behavioral symptoms, quality of life, or relationship satisfaction. One can conclude, then,

that using the internet for work is indicative of certain positive aspects of personality, but the

amount of time spent using the internet for work does not differentiate low hour users from users

online for great amounts of time in terms of personality, quality of life, or relationship

satisfaction.

Using the internet for shopping (i.e., shopping versus not shopping, not dependent on

time spent shopping) did not correlate with any factors of personality. However, shopping did

correlate negatively with facets such as emotionality and altruism. Within those who endorsed

shopping online, the amount of time spent shopping was not significantly associated with any

factors or facets of personality. Quality of life and relationship satisfaction was not associated

with time spent shopping. However, shopping hours were associated with higher levels phobic

anxiety symptoms. This is interesting in that no facets targeting anxiety were significantly

correlated with shopping, but users who shop endorsed higher levels of phobic anxiety symptoms

in their lives. One possible explanation is that phobic anxiety could manifest in these

individuals’ lives and result in more time spent away from the public (i.e., people who shop

online the most are anxious and avoid crowds, stores, and public places), however the current

study does not investigate the causal relationship. It is logically consistent, though, to conclude

that people who are at the extreme high end of time spent shopping online engage in the behavior

as an avoidance strategy; namely, they can have goods delivered to their house instead of

venturing out for them.

Users who sought recreation online were less agreeable than those who did not engage in

recreation online. This online behavior was also associated with less friendliness, trust, altruism,

achievement striving, modesty, self-discipline, cheerfulness, and sympathy. Recreation users

35

had higher scores for facets of depression, immoderation, and liberalism. As time spent online

for recreation increased, conscientiousness scores decreased significantly. More recreation hours

online were associated with higher scores on the imagination facet and lower scores on the self-

discipline facet. The behavioral symptoms of depression and anxiety were endorsed more as

users spent more time involved in recreation. Quality of life was also lower as users spent more

time engaged in recreation online. The higher levels of depression could account for why these

internet users spend more time inside online. The internet may allow them to feel involved in the

world without actually experiencing the real world. Interestingly, their quality of life is lower,

which indicates that their “real world” lives are less satisfying and they may use the internet as a

distraction or an avoidance strategy. Conversely, if these users are less agreeable in personality,

no matter the environment, then they may not be motivated to engage in real life activities and

may pass time online as a function of their anhedonia. This is striking in comparison to the users

who work online. Those who engage in recreation, especially those who engage in the most

recreation hours, appear almost opposite in personality to the work users (i.e., less self-discipline,

less cheerfulness, less achievement striving) and experience more symptoms of negative valence.

Maintaining personal relationships online was associated with higher openness scores and

lower conscientiousness scores. Users who maintain relationships online had higher imagination

scores, artistic interest scores, and emotionality scores. They had lower orderliness scores. As

users who maintained relationships online spent more time doing so, they had higher neuroticism

scores, and lower extraversion and conscientiousness scores. The facets positively associated

with hours spent maintaining relationships were depression and vulnerability; negative

associations included friendliness, self-efficacy, achievement striving, self-discipline, and