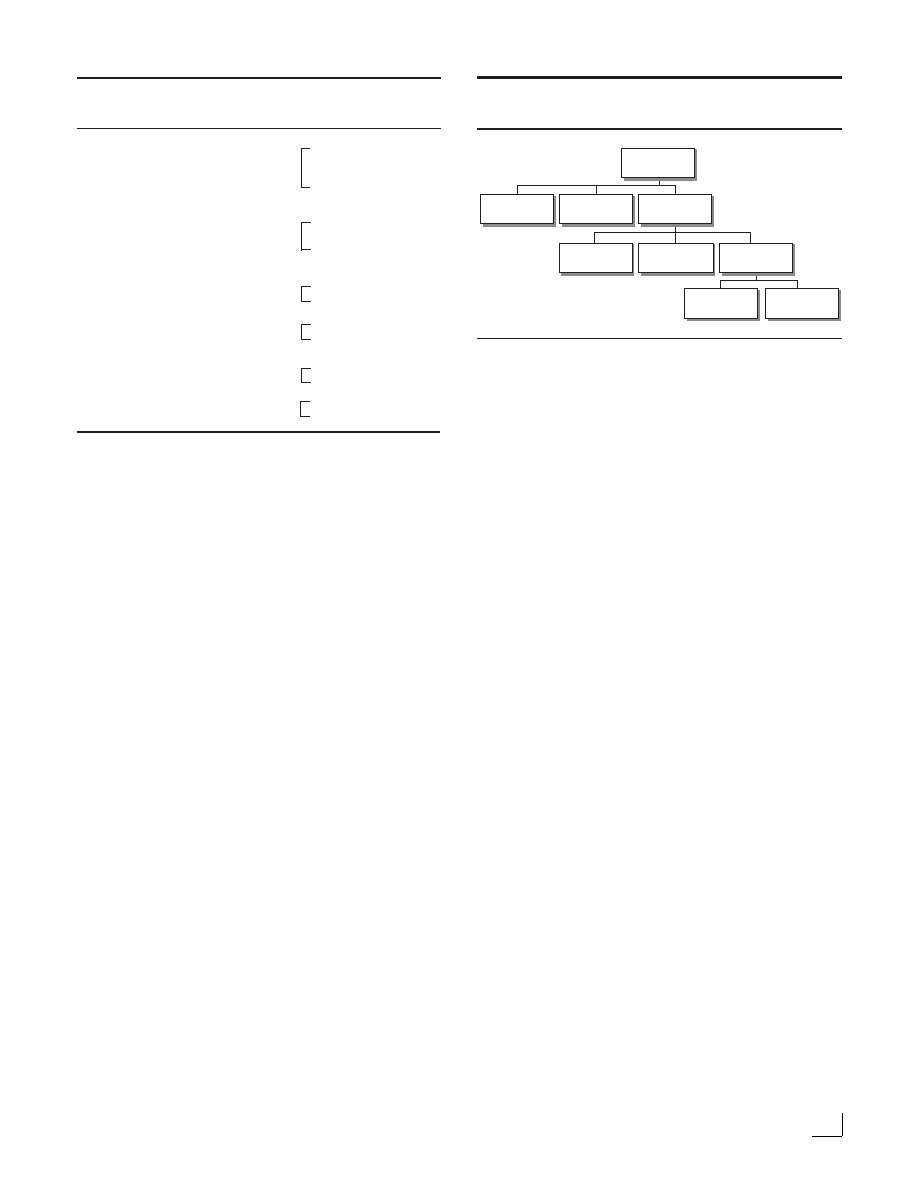

V O L U M E 17, N U M B E R 2

FALL 2002

J

ournal

B

usiness

mid-american

of

EDITORIAL

The Knowing-Doing Gap

3

Ashok Gupta

DEAN’S FORUM

Consumers and Expectations

5

James W. Schmotter, Dean, Western Michigan University

EXECUTIVE VIEWPOINT

After Enron: Government’s Role and Corporate Cultures

7

Carl Levin, United States Senator, Michigan

ARTICLES

The Social Impact of Business Failure: Enron

11

Uma V. Sridharan, Lori Dickes, and W. Royce Caines

Corporate Pension Plans: How Consistent are the Assumptions

in Determining Pension Funding Status?

23

Gale E. Newell, Jerry G. Kreuze, and David Hurtt

More Than Altruism: What Does the Cost of Fringe Benefits Say

about the Increasing Role of the Nonprofit Sector?

31

Rosemarie Emanuele and Walter O. Simmons

Subscription Supply Chains: The Ultimate Collaborative Paradigm

37

Robert L. Cook and Michael S. Garver

Selecting a Business College Major: An Analysis of Criteria and Choice Using

47

the Analytical Hierarchy Process

Sandra E. Strasser, Ceyhun Ozgur, and David L. Schroeder

BOOK REVIEWS

Business @ the Speed of Thought

57

Douglas M. Brown

Leading Quietly: An Unorthodox Guide to Doing the Right Thing

59

Alex Thompson

Mid-American Journal of Business

Subscriptions

All orders, inquiries, address changes, reprints etc. should be

addressed to:

Mid-American Journal of Business

Subscriber Service, Bureau of Business Research

Ball State University, Muncie, IN 47306

Telephone: 765-285-5926 FAX: 765-285-8024

www.bsu.edu/MAJB

Subscription prices in USA, Canada, and Mexico are:

$12 one year

$22 two years

$30 three years

All others add $5 per year for additional postage.

Permissions

For permission to quote, reprint, or translate Mid-American

Journal of Business materials, write or call: Judy A. Lane,

Managing Editor, Bureau of Business Research,

Ball State University, Muncie, IN 47306

email: jlane@bsu.edu, Telephone: 765-285-5926

Manuscripts

Send four manuscripts, $12.00, and editorial correspondence to:

Dr. Ashok Gupta

College of Business

Ohio University

Athens, OH 45701

Editorial Board

Ashok Gupta, Ph.D., Editor-in-Chief

College of Business

Ohio University

Athens, OH 45701

email: gupta@ohiou.edu

Cecil Bohanon, Ph.D.

College of Business

Ball State University

Muncie, IN 47306

email: cbohanon@bsu.edu

Richard Divine, Ph.D.

College of Business

Central Michigan University

Mt. Pleasant, MI 48859

email: divin1rl@cmich.edu

Laurence Fink, Ph.D.

College of Business Administration

University of Toledo

Toledo, OH 43606

email: lfink@pop3.utoledo.edu

Norman Hawker, Ph.D.

Haworth College of Business

Western Michigan University

Kalamazoo, MI 49008

email: norman.hawker@wmich.edu

Michael Hicks, Ph.D.

Lewis College of Business

Marshall University

Huntington, WV 25755

email: hicksm@marshall.edu

Curtis Norton, Ph.D.

College of Business

Northern Illinois University

DeKalb, IL 60115

email: nortonc@niu.edu

T.M. Rajkumar, Ph.D.

Richard T. Farmer School of

Business Administration

Miami University

Oxford, OH 45056

email: rajkumtm@muohio.edu

Judy A. Lane, Managing Editor

Bureau of Business Research

Ball State University

Muncie, IN 47306

email: jlane@bsu.edu

Board of Reviewers

Shaheen Borna

Ball State University

Larry Compeau

Clarkson University

Max Douglas

Indiana State University

William Dodds

Fort Lewis College

Ed Duplaga

Winona State University

Ray Gorman

Miami University

Mark Hanna

Georgia Southern University

Gary Kern

Indiana University at South Bend

Douglas Naffziger

Ball State University

Gale Newell

Western Michigan University

W. Rocky Newman

Miami University

Pamela Rooney

Western Michigan University

B. Kay Snavely

Miami University

Daniel Vetter

Central Michigan University

Leslie Wilson

University of Northern Iowa

Dale Young

Georgia College

The Mid-American Journal of Business provides a medium for business researchers and other

business professionals—executives, consultants, and teachers—to discuss research developments

and their practical implications. The Journal is sponsored by the following institutions:

Lynne Richardson, Dean

College of Business

Ball State University

John Schleede, Dean

College of Business Administration

Central Michigan University

Calvin A. Kent, Dean

Lewis College of Business

Marshall University

Roger Jenkins, Dean

School of Business Administration

Miami University

David Graf, Dean

College of Business

Northern Illinois University

Glenn Corlett, Dean

College of Business

Ohio University

Sonny Ariss, Interim Dean

College of Business Administration

The University of Toledo

James Schmotter, Dean

Haworth College of Business

Western Michigan University

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without written permission.

© 2002 by Ball State University ISSN: 0895-1772

Produced at the Bureau of Business Research, Ball State University, Sandra Burton, Publications Coordinator

www.bsu.edu/business/MAJB

1

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

The Social Impact of Business Failure: Enron

Sridharan et al. highlight the conflicts of interest

and discuss the social and financial impact of a

combined business and oversight failure at Enron.

Uma V. Sridharan, Lori Dickes, and

W. Royce Caines

11

BOOK REVIEWS

Business@ the Speed of Thought

by Bill Gates

Douglas M. Brown

57

EXECUTIVE VIEWPOINT

7

After Enron: Government’s Role and Corporate

Cultures

Levin maintains that what happened at Enron was

not just a failure of regulations and law, it was a

failure of corporate culture, a failure of values, a

failure of heart.

Carl Levin

37

Subscription Supply Chains: The Ultimate

Collaborative Paradigm

Cook and Garver argue that supply chain members

need to get closer to the end consumer by forming

collaborative relationships that center around

demand planning.

Robert L. Cook and Michael S. Garver

DEAN'S FORUM

5

Consumers and Expectations

Managing customer expectations starts with

realistic marketing.

James W. Schmotter

Fall 2002 Volume 17 Number 2

CONTENTS

3

EDITORIAL

The Knowing-Doing Gap

Discussing a problem, formulating decisions, and

crafting plans for action are not the same as actually

fixing the problem.

Ashok Gupta

Corporate Pension Plans: How Consistent are the

Assumptions in Determining Pension Funding

Status?

Pension plan assumptions regarding discount rates,

projected salary increases, and expected return on

plan assets are investigated in relation to the

funding status of a pension plan.

Gale E. Newell, Jerry G. Kreuze, and David Hurtt

23

47

Selecting a Business College Major: An Analysis

of Criteria and Choice Using the Analytical Hierarchy

Process

In this article, Strasser et al. use the Analytic

Hierarchy Process (AHP) technique to provide

insights into criteria used by students and the

decision process they follow in choosing a major.

Sandra E. Strasser, Ceyhun Ozgur, and

David L. Schroeder

31

More Than Altruism: What Does the Cost of Fringe

Benefits Say about the Increasing Role of the

Nonprofit Sector?

Emanuel and Simmons attribute the significantly

lower expenditure for fringe benefits by nonprofits

to more than altruism of the workers.

Rosemarie Emanuele and Walter O. Simmons

ARTICLES

Leading Quietly: An Unorthodox Guide to Doing the

Right Thing

by Joseph L. Badaracco, Jr.

Alex Thompson

59

2

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

CALL FOR PAPERS

Call for Papers

The program committee invites you to submit:

•

Regular research papers: You can submit a

complete paper in this category. If your paper is

in an abstract form or in a proposal form, see the

categories listed below.

•

Work-in-progress or proposals: The MWDSI

Board of Directors has decided to create an

environment where academicians can discuss

their ideas for future research in all track areas.

Papers submitted in this category are encour-

aged to be of regular paper length.

•

Papers or reports on teaching-related issues: In

addition to an Innovative Education track,

sessions will be dedicated to instructional

issues in all track areas. Submissions in this

area are strongly encouraged.

•

Symposia, tutorials, workshops: Proposals for

symposia, tutorials and workshops are invited

in, but limited to the track areas listed.

•

Student Research Papers: Student research papers

may be submitted according to the track areas

listed.

•

Case Studies: Case studies will report on the

application of theory to actual business practices.

Submissions will be blind refereed. Student

papers will be incorporated into the regular

presentation sessions during the conference. By

submitting a manuscript, the author(s) certify

that it is not copyrighted, previously published,

presented, accepted, or currently under review for

presentation at another professional meeting.

Submission of a paper implies that an author will

register for the conference, attend the conference and

present the paper, if accepted.

Program Participation

Paper reviewers, discussants, and session chairs will

be needed. Please contact Program Chair Gene

Fliedner to indicate your interest. Participants may

be asked to serve in these capacities.

Membership Requirement

Awards will be given for Best Paper and Best

Student Paper at the meeting. Student Papers must

be authored by students only and identified as

eligible to compete.

Instructions for Contributors

Contributors should mail their submissions directly

to the Program Chair. All submissions must be

postmarked by December 1, 2002 to be considered

for publication in the proceedings. Papers submitted

after December 1, 2002 but before December 15,

2002 can still be reviewed and accepted for the

meeting, but will not be included in the Proceedings.

Papers submitted after December 15, 2002 will not

be accepted for the meeting. Authors may choose to

indicate their preference of time of day (i,e, a.m. or

p.m.) and the day of the meeting (i.e. Thursday,

Friday or Saturday) for their paper presentations.

These time and day requests will be honored on a first

come, first serve basis. Early submissions are encour-

aged to permit early acceptance notifications (roughly

within 60 days of submission). An advanced

registration fee for at least one author will be required

to guarantee publication of the accepted paper in the

Proceedings. Authors will be notified of publication

preparation guidelines upon acceptance. Contribu-

tors are asked to follow the following guidelines for

submissions:

•

Submit four (4) typed, double-spaced copies

of your paper, abstract or special session

proposal.

•

Include in your submission a separate title

page (on each copy) including author(s)’ names

and affiliations. The main body of the paper

must have a title but should not include

author(s)’ names and affiliations.

•

Include with your submission two 3x5 cards

listing: author(s), affiliations,complete mailing

addresses, telephone numbers, e-mail addresses,

title of submission, selected track, name of

corresponding author.

Submission Deadline: December 1, 2002

2003 Annual Meeting—Sponsored by Miami University

Miami University, Marcum Conference Center—Oxford, Ohio

March 27-29, 2003

MIDWEST

DECISION

SCIENCES

INSTITUTE

Submit to:

W. Rocky Newman

Department of Management

Miami University

Oxford, OH 45056

Receive $500 cash award and

opportunity to be published in

Mid-American Journal of Business.

B

EST

P

APER

A

WARD

Tracks:

Accounting and Finance

Global Business Management

and Strategy

Information Technology and

e-business

Operations Management—

Manufacturing

Operations Management—

Service

Quantitative Methods and

Statistics

Supply Chain and Marketing

Management

Student Papers

Program Chair

W. Rocky Newman

Tel: (513) 529-4219

newmanw@muohio.edu

Miami University

Oxford, OH 45056

Proceedings Editor

Tom Gattiker

(513) 529-8013

gattiktf@muohio.edu

Miami University

Oxford, OH 45056

Local Arrangements

Coordinator

Tim Krehbiel

(513) 529-4837

Krehbitc@muohio.edu

Miami University

Oxford, OH 45056

EDITORIAL

The Knowing-Doing Gap

Ashok Gupta

Editor-in-Chief

These days there is a crisis of confi-

dence all around, in corporations,

churches, colleges – who can we trust?

Corporate leaders are maximizing their

personal wealth rather than shareholder

value. Priests are advising others to

control their greed and lust while trapped

in the affairs of the world themselves.

College administrators swear to provide

relevant and rigorous education while

engaging in showmanship of innovative

pedagogical approaches and wasteful

expenditures on one hand and increasing

tuition and reducing faculty positions on

the other. Do these people not know what

is the right thing to do? I doubt if the

problem is lack of knowledge. They are

all smart people. They all know what to

do. There is just not enough doing. Why

do we still believe that setting up a

committee to examine an issue will solve

the problem? Why do we believe that

having Executive Advisory Boards in the

Colleges of Business will make our

education relevant to business needs?

Why do we believe that having policies

on key issues is equivalent to their

effective implementation? Perception of

action has become more important than

real action. Let’s not kid ourselves —

discussing a problem, formulating

decisions, and crafting plans for action

are not the same as actually fixing the

problem.

In this issue……

What happens when those trusted to

protect the integrity of the system for the

long-term interest of shareholders

become its destroyers? This first article

by Sridharan et al. highlights the conflicts

of interest that pervade the financial

system and discusses the social and

financial impact of a combined business

and oversight failure at Enron. The article

could be used as a pedagogical tool in

business ethics, business strategy, and

corporate governance.

Pension expense can be a significant

element in determining net income and

the funding status of the plan is important

in evaluating the financial risk of a firm.

The pension plan’s funding status can also

impact the financial health of large numbers

of employees in retirement. Newell et al.

investigate the relationship between

pension plan assumptions regarding

discount rates, projected salary increases,

and expected return on plan assets and the

funding status of a pension plan.

Although it is well established that

wages are significantly lower in the

nonprofit than in the for-profit sector, not

much is known about the cost of fringe

benefits in the nonprofit sector. In the third

article, Emanuele and Simmons report that

nonprofit organizations spend over 80

percent less on fringe benefits than compa-

rable for-profit firms and government

agencies. They attribute this differential

to more than altruism of the workers.

While great strides have been taken

toward forming collaborative partnerships

between business-to-business firms, the

end consumer is typically not viewed as a

supply chain partner. Cook and Garver

argue that supply chain members need to

get closer to the end consumer, resulting

in better demand planning, dramatic cost

reductions, superior customer value and

satisfaction through lower costs, in-

creased convenience, and improved

availability of products.

While students’ strengths and interests

are important in deciding their major field

of study, what other criteria might they

use in their decision making process?

Using the Analytic Hierarchy Process

(AHP) technique, Strasser et al. provide

insights about the criteria students use

and the decision process they follow in

choosing a major for their studies.

n

3

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

4

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

This special issue will explore the implications of social responsibility on

the practices of for-profit organizations. Articles will examine the various

effects on business practices.

Articles representing original research will examine various social and

economic themes, such as those listed below:

• E-commerce

(e.g., access, privacy, equality, employee benefits)

• Human resource management

• Environmental impacts

• Public policy and business taxation

• Responsible marketing

(e.g., targeting children, marketing dangerous products)

• International trade

(e.g., sweat shops, outsourcing, gray markets)

• Competition law, regulation and GATT/WTO

• Financial transparency

• Copyright and intellectual property

• Cost transfer from private sector to public sector

Social Impacts of Business Practices

Reprints of any article are available from the Managing Editor

or on-line at www.bsu.edu/MAJB.

To become a subscriber to the

Mid-American Journal of Business,

Please complete and mail this form to:

Bureau of Business Research

WB 149

Ball State University

Muncie, IN 47306

or go on-line at www.bsu.edu/MAJB.

The MAJB publishes original research of

interest to academics and practitioners

from all functional areas of business. The

Journal’s acceptance rate is approxi-

mately 15 percent.

Special Issue–Spring 2003

Name

Title

School/Business

Address

City

State

Zip

q

1 year–$12 U.S.

q

2 years–$22 U.S.

q

3 years–$30 U.S.

Managing Editor:

Judy Lane

(jlane@bsu.edu)

College of Business

Ball State University

Muncie, IN 47306

765.285.5926

Don’t miss the…

To Subscribe…

To Subscribe…

To Subscribe…

To Subscribe…

To Subscribe…

q

Check enclosed

q

Please bill me

Mid-American Journal of Business

Schmotter

5

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

James W. Schmotter, Dean

Western Michigan University

DEAN’S FORUM

Consumers and Expectations

All of us who labor in business col-

leges recognize the comments above.

Probably most of us have also participated

in the perennial debate about whether or

not students are customers, a debate not

likely to subside anytime soon. In fact,

various trends promise to increase the

consumerist viewpoint among our stake-

holders. The transparency of information

provided on the Internet and through

various other media has greatly increased

competition among our institutions. This

competition leads to more professional

marketing approaches, to more sophisti-

cated understandings of consumer needs,

and to more explicit promises in our

efforts to close the sale. Rising tuition and

costs of higher education everywhere also

increase the consumerist attitude; the

parent foregoing lifestyle amenities and

the student incurring debt both believe

that their investment entitles them to

special treatment as valued customers.

They are, after all, purchasing a very

expensive good. We ourselves in business

education have encouraged this attitude

through the stakeholder-oriented, continu-

ous improvement approach that AACSB

accreditation standards have mandated

since 1991. We in B-Schools know how to

do strategic planning, and our educational

models invariably include folks who look

a lot like customers.

However, we all know it is not that

simple. Unlike Wal-Mart or General

Electric, we provide our “customers” a

complex, intangible “product” that may

not satisfy all their preferences. Certainly

if those preferences include grades of at

least B with one hour of study per week

in “fun” courses always scheduled

between noon and 3 PM on Tuesdays and

Thursdays, they will be disappointed.

Likewise, we cannot guarantee a job

paying a stipulated starting salary in a

specific company or industry to all

graduates. We cannot even provide

assurance that they will be motivated in

all classes by equally dedicated profes-

sors resembling Richard Dreyfus in his

recent short-lived academic TV series.

Neither can we promise them they will

find love, happiness, and personal

gratification during their years with us.

Customers who come to us with such

expectations will be disappointed, and we

must manage these expectations.

Managing expectations starts with

realistic marketing. In the war for student

talent and ranking position, we often

overstate our achievements and capacity.

No business school can be all things to all

possible students, but many admissions

catalogues give that impression. Nearly

all of us can find a media ranking which

attaches some number, even if context-

Distinguished University President

“Students are our customers, and we must meet their needs. After all, we operate in a

competitive admissions marketplace.”

Outraged Senior Professor

“I’m appalled that we call our students “customers” (ugh!); that demeans everything that

the academy stands for!”

Aggrieved Undergraduate Parent

“Look, I’m paying (fill in the dollar amount) a year for my son to be here, and you had

better (fill in the blank)!”

Schmotter

6

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

• ABI/INFORM Global

• American Overseas Book Company

• The Business Index—(online) Ziff

• Business and Economics Research Directory

• Cabell’s Directory of Publishing Opportunities

in Management and Marketing

• EBSCO Subscription Service

• Emerald Reviews

• Gale Directory of Publications and

Broadcast Media

• Harrassowitz Booksellers & Subscription

Agents

• InfoTrac

• McGregor Subscription Service

• Omnifile (H. W. Wilson Company)

• Popular Subscription Service

• PsycINFO, PsycLIT, ClinPYSC, and

Psychological Abstracts

• Public Affairs Information Services (PAIS);

also online

• Publishers Consulting Corporation

• Readmore Subscription Service

• Reginald F. Fennell Subscription Service

• RoweCom

• The Serials Directory--EBSCO

• Standard Periodical Directory

• SWETS Blackwell Subscription Service

• SWETSNET

• Ulrich’s International Periodicals Directory

• Working Press of the Nation

www.bsu.edu/MAJB

Mid-American Journal of Business

Listings

The Journal is proud to be listed with several abstract-

ing, indexing, and subscription services that provide

educators and business practitioners access to the

Journal’s timely and informative research.

less, to our quality. Likewise, many of our institutions

suffer from serious mission-creep. Strong undergraduate

programs dilute their quality by expensive forays into the

MBA world. The drumbeat sounds on many campuses

for the establishment of new doctoral programs, but for

questionable reasons such as individual faculty ego or

inclusion in particular institutional taxonomies. Unhappy

customers are often the ultimate result of expectations

based on overly ambitious aspirations.

Setting sound expectations, on the other hand, is based

on equally sound information. Students and parents

should expect to know the qualifications of the faculty

who teach them. Course syllabi should be clear and

outline learning goals for individual courses. Information

on class size and ease of access to required courses

should be readily available. Student services personnel

should complement the academic mission, not replace or

hinder it with bureaucracy. Information about career

placement should be accurate and timely, even if it does

not confirm the claims of admissions recruiting materials.

Yet simply meeting these basic expectations does not

adequately address the dilemmas that increasing consum-

erism engenders. Our “customers” must have a better

understanding of what exactly it is that they are purchas-

ing. Here is one way to help them build that understanding.

Higher education, like many other professional

services, requires active participation by consumers to be

effective. The consumer must bring attention, engage-

ment, and effort in order for the product to add value. A

more passive approach, which I fear is common of

undergraduate education on most of our campuses, will

result in far less value added. It is not unlike buying a

gym membership and expecting to add muscle tone

without pumping iron or thinking that an expensive new

driver will lower your handicap without hours on the

practice tee. This is not smart consuming.

The importance of active engagement by students in

their education to ensure value added results returns us to

one of the traditional purposes of higher education, and

one upon which we call can agree, no matter if we use the

“C” word or not. This purpose is to fire the imagination

of young minds within the classroom, library, laboratory,

or late night residence hall bull session. It is up to us,

from the first day that students arrive on our campuses, to

demonstrate to them through instruction and personal

example, the special opportunity for intellectual growth

they possess during their time with us. They can watch

“Friends” or drink Budweiser the rest of their lives, but

they can only reap the rewards of smart consumption of

higher education during this unique time in their lives. If

the understanding of that reality is clear, our ability to

manage customer expectations in face of all of society’s

countertrends becomes far easier. And we become

recognized as the terrific bargain that we really are.

n

7

EXECUTIVE VIEWPOINT

While the events of 9-11 forced us to

rethink our sense of security in a troubled

and ever-shrinking world, on a somewhat

smaller scale but no less sudden and

dramatic, the collapse of the Enron

Corporation just a few months later has

raised troubling questions about our sense

of economic security and about the engine

of our economic stability and prosperity

— American corporations. While thou-

sands of Enron employees and sharehold-

ers saw their paychecks, their retirement

savings or the value of their investments

disappear overnight, countless millions of

Americans were wondering, could it

happen to me?

But that was not the only question

being asked in the wake of the largest

bankruptcy in American history. People

want to know how it happened. They want

to know how so many Enron executives

could walk away from the disaster they

created with tens of millions of dollars in

their pockets. They want to know, with all

the systems in place to protect employees

and consumers—the auditors, the Board

of Directors, the Securities and Exchange

Commission—how the sudden bankruptcy

of a company this large could happen.

And with more than 50 percent of Ameri-

can households now owning stock,

directly or indirectly, these questions are

being asked on Main Street, not just on

Wall Street.

Looking for answers to these and other

important questions, several Congres-

sional committees have begun to investi-

gate various aspects of the Enron disaster.

One of these investigations is being

conducted by the Permanent Subcommit-

tee on Investigations. This subcommittee

of the Governmental Affairs Committee

had its origins during World War II when

then Senator Harry Truman led an

investigation of price gouging and

contractor fraud in defense industries.

Later on it was the venue for labor

racketeering hearings, organized crime

hearings, and a wide variety of investiga-

tions into various criminal enterprises

from drug trafficking to the fraudulent

use of the student loan program to

insurance fraud. In recent years, we have

conducted an in-depth investigation into

money laundering and how drug traffick-

ers, terrorists, and other criminals try to

use our financial institutions against us.

As a result of this work, it was able to

adopt tough, new anti-money laundering

laws. Given the Subcommittee’s expertise

in issues related to financial institutions

and the international movement of

money, it could contribute to unraveling

the Enron mess.

To that end, in January, the Subcom-

mittee issued over fifty subpoenas to

Enron, Enron officers and board members,

and Arthur Andersen and, as a result, we

now have over one million pages of doc-

uments to review and digest. It is time

consuming and difficult work. A popular

phrase today is, “This isn’t rocket science.”

In some respects these elaborate financial

structures that Enron created are “rocket

science.” And what fueled that rocket is

not fiduciary duty but personal greed.

Enron was the largest energy trader in

the world, worth $80 billion, with 20,000

employees. It reached that point by the

tangled and deceptive use of a reported

3,000 affiliates, approximately 800 of

which were in offshore tax havens.

The Subcommittee found that when it

pared down the hundreds of incredibly

* Adapted from Remarks of Senator Carl Levin, to the Economic Club of Detroit,

Monday, April 22, 2002

After Enron:

Government’s Role and Corporate Cultures

US Senator Carl Levin

Michigan

“…what happened at

Enron was not just a

failure of regulations

and law, it was a

failure of corporate

culture, a failure of

values, a failure of

heart.”

Levin

8

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

complex financial transactions that were the hallmark of

Enron, many were nothing more than smoke and mirrors

bookkeeping tricks designed to artificially inflate earn-

ings rather than achieve economic objectives, to hide

losses rather than disclose business failures to the market,

to deceive more than inform. The decisions to engage in

these complex transactions were fueled by interlocking

conflicts of interest, a shocking disregard of investors,

and arrogance. Business managers are all familiar with

the concept of compound interest and how it allows

wealth to grow. Enron created a new concept—compound

conflicts of interest, which allowed deception to grow to

new heights or more appropriately... new lows.

Let us look at the ABCs of Enron—and this is meant

literally. That is, Enron was so creative at creating new

types of devious and deceptive business practices that

you can not keep track of them without using a scorecard

to sort it out.

Deception Type A…reporting the sale of an asset on

the company’s financial statement, despite a quiet

understanding that Enron will buy it back after the

financial statement is filed or despite a hidden guaran-

tee that the entity buying the asset will receive a

certain rate of return. Five of the seven assets sold that

way at the end of the last two quarters of 1999 had to

be bought back, within six months’ time. But those

guarantees did not show on the books as liabilities,

only the sale prices showed as income.

Deception Type B…making a loan look like a sale so

the company’s financial statement reflected the

transaction as income instead of debt. One $350

million example involves Mahonia, an Enron transac-

tion with an offshore company named appropriately

enough after a flower that grows in the dark. It was set

up as a complex, three-party transaction using multiple

energy derivatives. In the end, when the bare bones of

the transaction were exposed, it was nothing more than

a loan by a big investment bank to Enron. The invest-

ment banks not only knew what was going on in these

transactions, they actively marketed these schemes to

other investors.

Deception Type C…inflating the value of the assets

Enron held for sale. For example, Enron would buy a

power plant on day one for $30 million and within a

month or so they would begin carrying it on their

books as an asset worth $45 million.

Deception Type D…Enron using its own stock to

backstop a risk another entity was supposed to be

assuming for Enron. The infamous example occurred

in a set of transactions appropriately enough called the

Raptors. And, of course, the risk retained by Enron in

these transactions was not clearly disclosed on the

company’s financial statements. Even the most

sophisticated investors were misled.

Those are the types of deceptive transactions the

Subcomittee has identified so far in its investigation. We

may have to use the whole alphabet by the time we are

done. On top of the deceptions—and no doubt the reason

they went on without detection or objection—are the

conflicts of interest among the people and entities

involved.

Enron created a new concept—

compound conflicts of interest, which

allowed deception to grow to new

heights or more appropriately...

new lows.

The first conflict of interest involved Enron’s manage-

ment, the folks who spun this web of deception. Enron

hired aggressive, bright managers and paid them exorbi-

tantly. In fact, the company made some 2,000 millionaires.

Enron’s CEO earned $140 million in a single year. It also

handed out bonuses like candy at Halloween. Two execu-

tives who closed a deal on a power project in India, which

is now in trouble, got bonuses in the range of $50 million

just for closing the deal. The head of one Enron division

was moved out of the company and walked away with

more than $250 million in the year he was shown the door.

There is nothing inherently wrong with generous

compensation for a company’s managers, but when that

compensation is so completely divorced from the eco-

nomic realities of a company, it can constitute a conflict

of interest, and it certainly did in Enron. Those kinds of

compensation arrangements focus company managers on

today’s deal or today’s stock price and not on the long-

term value or growth of the company. That focus helped

run up the value of management’s own stock options in

the short run, but did nothing to protect the long-term

interest of employees and shareholders.

A particularly egregious variation on this type of

conflict of interest can be seen in the case of Andrew

Fastow. Fastow, Enron’s Chief Financial Officer, was

allowed to be the managing partner of an entity called

LJM that was used to buy assets from Enron no one else

would buy. LJM bought many of these assets and sold

pieces to outside investors because of Enron’s undis-

closed guarantees. Talk about a conflict. Enron was

basically negotiating the sales of these assets with its own

employees. And, to top it off, Fastow ended up making

well over $30 million from the partnership.

There were other conflicts of interests. Enron directors

were supposed to exercise their best business judgment

on behalf of shareholders. But Enron directors were

picked by management and were so extraordinarily well

paid, receiving cash and stock worth about $300,000 a

year, that their independence was jeopardized. They too

had so much to gain from the deceptions that passed for

Levin

9

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

accepted business practice at Enron that they were

content to accept whatever explanations and information

management gave them. They failed to look hard, ask

tough questions, and consider personal motivations of

management that prompted the deceptive transactions

that ultimately contributed to Enron’s downfall.

If Enron’s board was too compromised to bring

independent oversight to the company, what about its

auditors? Enron’s now infamous auditors, Arthur

Andersen, earned $52 million in fees from the company

in the year 2000, the last full year they worked for the

company. Enron was Andersen’s largest client. For two

years Andersen served as both Enron’s external and

internal auditor and for many years it also served as

Enron’s management consultant. Therefore, they were

auditing their own work. Employees of Andersen

routinely crossed over to work for Enron, and an

Andersen employee who actually questioned an Enron

practice while serving on an audit team was promptly

reassigned to another client at Enron’s urging. With so

much to gain from its relationship with Enron’s

management, there was too much temptation for Arthur

Andersen to avoid blowing the whistle.

Well then, how about the financial analysts? These

folks are supposed to give objective advice on stocks,

but the analysts are often employed by the investment

banks that earned huge fees for designing, promoting,

and actually becoming partners in Enron deals. New

York’s attorney general has shown how conflicted these

investment banks can be by revealing the recent e-mails

of financial analysts at Merrill Lynch, describing to each

other as “junk” the investments they were recommend-

ing to the public to “buy.” Four types of deception and a

variety of conflicts of interest allowed those deceptions

to take root and grow to a bankruptcy that at latest count

leaves Enron owing over $100 billion.

So now the question everyone might ask is what to

do about it? The answer to that question is in two

parts, with the first part focusing on what government

should do.

It is possible to draw a parallel between the new

threats to the nation’s security posed by 9-11 and the

new threats to economic security raised by the collapse

of Enron. The attacks on New York and Washington

changed the perception of Americans, the world around

them, and their own country. Americans began to see,

what they perhaps should have seen all along, that

government is not some distant alien force in our lives.

Government is the fireman running into a building from

which others are fleeing for their lives. It is the rescue

worker sifting through rubble long after others have

abandoned hope. And it is the civil servant quietly going

back to work in the Pentagon, just yards away from

where a colleague’s life was cut short by a senseless act

of terror. Government is the people, acting together for

the common good.

Over the last twenty-five years, with both Democratic

and Republican administrations in the White House, the

country moved steadily towards a less regulated economy

and few would argue that we should suddenly reverse

direction. But the challenge for America today, made

clear by the Enron fiasco, is to find the legitimate role for

government to play in this new, largely deregulated

economy.

When Franklin Roosevelt became president seventy

years ago he had more than his share of critics who were

convinced that his policies would spell the end of our free

enterprise system. But in the wake of the Great Depres-

sion, his reforms saved our economic system from its own

excesses and provided a foundation of economic security

that made this country the prosperous and free nation it is

today.

Today the challenge Americans face is different than

FDR’s. Increasingly Americans are both workers and

shareholders and as such, they are vulnerable to the kind

of manipulations and deceptions that left hundreds of

thousands of Enron employees and shareholders with

nothing but broken dreams for all their years of hard

work. This country needs to think boldly about what

economic security means in this new economy.

And in that spirit I have introduced legislation that

would establish a Shareholders’ Bill of Rights.

– This bill of rights would reform the way account-

ing standards get issued so that the board that

issues them is truly independent and accountable

to the public. To ensure its independence, the

board must have funding that is not connected to

the major accounting firms or their corporate

clients. The end result should be standards that

prevent any company from claiming that Enron-

like accounting contortions are within the rules.

– It would strengthen auditor independence by

preventing auditing firms from providing non-

auditing services, such as consulting, during the

course of an audit and for two years afterward.

– It would require shareholder approval of any stock

option compensation plan that will not be shown

on company financial statements as an expense.

– It would require prompt disclosure of company

loans to board members and officers.

In addition, Congress needs to strengthen the Securi-

ties and Exchange Commission so that this critical

watchdog agency is not hopelessly outgunned by those

companies it oversees.

As previously noted, the answer to the question what

to do to prevent further “Enron-type fiascos” required a

two part answer. The second part is not about government

at all, it is about the private sector. While there must be a

new role for government in the new economy, govern-

Levin

10

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

ment action cannot provide most of the answer. That is

because what happened at Enron was not just a failure of

regulations and law, it was a failure of corporate culture,

a failure of values, a failure of heart. And even the best

government policy cannot change that. That change will

come from the actions of leaders in the business commu-

nity who by their example promote a culture of openness,

of competency, and of candor.

Corporate boards and corporate officers have a

fiduciary duty to their stockholders. That duty, that

fiduciary duty, needs to be reinforced in this new century.

When business leaders ignore that duty, the results are

corrosive to our society as a whole. They undermine the

basic sense of fairness and honesty that binds us together

as a people. The pursuit of personal profit at any cost

cheapens the core values that make America the great

country it is. How can Americans tell their children to

play by the rules when con men disguised as corporate

managers walk away from an Enron with millions in their

pockets while leaving behind nothing but a trail of false

profits and broken dreams? Americans know what a

difference the right kind of business leadership can mean

for a community because this country has been blessed

with a number of business leaders who have exemplified

corporate citizenship at its best.

It is a much different world since September 11, but this

country should remember something that has not changed,

something that is as true today as it was fifty or a hundred

years ago. To realize its great potential as a nation

America must always strive to find the right balance

between the bottom line and the common good.

n

About the Author

Carl Levin is the chairman of the Senate Armed Services

Committee. He was an early and consistent advocate of efforts

to prepare the American military to combat terrorism and other

emerging threats of the post-Cold War world. Senator Levin

also serves as the chairman of the Permanent Subcommittee on

Investigations of the Governmental Affairs Committee. He is a

member of the Small Business Committee and the Senate Select

Committee on Intelligence.

Levin is perhaps best known for his efforts to make our

government both more effective and more ethical. He authored

the Competition in Contracting Act, which has led to significant

reductions in federal procurement costs. His Whistleblower

Protection Act protects federal employees who expose wasteful

practices.

In 1956 he graduated with honors from Swarthmore college

and from Harvard University Law School in 1959. He practiced

and taught law in Michigan until 1964 when he was appointed

an assistant attorney general of Michigan and the first general

counsel for the Michigan Civil Rights Commission. He has

represented Michigan in the U.S. Senate since 1978.

11

The Social Impact of Business Failure: Enron

Uma V. Sridharan,

Lander University

Lori Dickes,

Lander University

W. Royce Caines,

Lander University

Abstract

Between October and November 2001 the world

witnessed the collapse of Enron, a major US publicly

traded corporation with global operations. The Enron case

highlights the impact corporate failure has on American

society and capital markets and underscores the need for

better enforcement of regulations and ethical business

behavior. This paper discusses the role played by Enron’s

senior management, its board of directors, Enron’s audi-

tors, consultants, bankers, Wall Street and the government,

in the spectacular rise and fall of this corporate giant. It

also examines the impact of Enron’s failure on its

employees, the employees of Andersen, and on thousands

of ordinary Americans who invested in the stock via their

pensions and mutual funds. This paper highlights the

conflicts of interest that pervade the financial system

and discusses the social and financial impact of a com-

bined business and oversight failure. Students and

teachers of finance, corporate governance, and business

strategy may be interested in this paper as a pedagogical

tool to teach undergraduate finance, business ethics,

business strategy, and corporate governance.

Keywords: corporate governance, strategy, business

ethics, board of directors, mutual funds, social

impact, financial transparency, securities acts,

pension funds

Introduction

Enron, once the world’s largest energy company, was

ranked number seven by Fortune magazine in April 2001

in Fortune’s ranking by market capitalization of the five

hundred largest corporations in the United States. On

December 2, 2001, Enron filed for Chapter 11 bank-

ruptcy. The sudden and swift collapse in the market value

of this corporate giant has had major ramifications for

nearly all of its stakeholders including, but not limited to,

its shareholders, employees, creditors, and auditors. The

causes and consequences of the Enron bankruptcy filing

highlights the social impact of business failure, which is

the focus of this paper.

Before the collapse of Enron, many individuals and

institutions in the United States, including representatives

in the US Congress, were largely in favor of deregulation

of business. However, in the wake of huge losses at the

Enron Corporation, the debate on regulation vs. deregula-

tion has been revived and gained momentum. It has

become increasingly evident that corporate failure of the

magnitude of Enron causes serious economic, political,

and social dislocation.

Before the securities market crash of 1929 and the

Great Depression, there was very little support for

governmental regulation of securities markets. Many

individuals and institutions lost significant sums of

money in the 1929 crash, which also brought about a

steep decline in public confidence in securities markets.

To restore the investing public’s faith in capital markets,

Congress passed the Securities Act of 1933 and Securities

Exchange Act of 1934. These laws were designed to

restore investor confidence in U.S. capital markets by

providing for more structure and oversight.

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 created the US

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The primary

mission of the US Securities and Exchange Commission

is to protect investors and maintain the integrity of

securities markets. The SEC oversees corporate disclo-

sure of information to the investing public. Public

companies in the United States with more than $10

million in assets and whose securities are held by more

than 500 owners are required to file annual and quarterly

statements (Forms 10K and 10Q) with the SEC. These

forms are supposed to disclose information about such

public companies’ financial condition and business

practices. This disclosure is expected to help investors

make informed investment decisions. This SEC review

process is intended to check if firms are meeting their

disclosure requirements. The SEC seeks to improve the

…corporate failure of the magnitude of

Enron causes serious economic, political,

and social dislocation.

Sridharan, Dickes, and Caines

12

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

quality of the information disclosed and to help make a

company’s financial statements ‘transparent’, i.e., more

easily understood by the investing public. The rest of this

paper is organized in five sections. The first section

discusses the roles and responsibilities involved in the

financial reporting process. The second section covers a

brief history of Enron, including a summary of events

leading up to its bankruptcy filing. The third section

discusses the social impact of this corporate failure. The

fourth section discusses how and why the US corporate

governance system failed to prevent this corporate

collapse. It examines the role played by various agencies

including Enron’s consultants, its top management, its

board of directors, external auditors, Wall Street analysts,

and the government (SEC). The final section concludes

the paper with a discussion of reforms following the

Enron failure.

Roles and Responsibilities

The United States’ securities laws and corporate

governance system requires that a board of directors

supervise the management of each public corporation.

Every director is expected to act in good faith and in the

best interests of the company. The director, in exercising

his or her duties, is expected to exercise skill and dili-

gence. A director may be sued for the failure to take

reasonable care, or for a breach of duty of care to the

firm, in circumstances where it can be shown that he or

she failed to exercise due care. If it can be shown that a

director was knowingly a party to conducting the firm’s

business in a reckless manner, the Courts may make the

director personally liable for any harm caused to the firm.

The role of the audit committee of the board of

directors is delineated in the charter of the audit commit-

tee. Generally, the audit committee of the board of

directors is responsible for recommending the selection of

the company’s external auditors and for recommending

the fees payable to external auditors. The audit committee

is also generally expected to review the audit plan

developed by management and the external auditors, and

to periodically review the performance of the external

auditors. The audit committee is required to review the

firm’s annual financial statements, including whether the

firm’s accounting and management systems and reports

comply with generally accepted accounting principles

(GAAP). The audit committee is expected to periodically

review the firm’s system of internal controls includ-ing

its risk management policy. The SEC views the firm’s

audit committee as playing a critical role in the financial

reporting system and requires extensive disclosures about

a public company’s audit committee and its interaction

with the company’s external auditors. The SEC requires

audit committees to state whether they have reviewed and

discussed the audited financial statements with the firm’s

management and the independent external auditors.

When a public company files its annual and quarterly

reports with the SEC, the firm’s management is required

to take responsibility for the integrity and objectivity of

the firm’s financial statements. Management is expected

to prepare the company’s financial statements in confor-

mity with GAAP. Management is also expected to have in

place a system of internal controls designed to provide

reasonable assurance of the reliability of financial

statements as well as the protection of the firm’s assets

from unauthorized acquisition, use, or disposition. The

internal control system is to be strengthened by having

written policies and guidelines that are to be implemented

by qualified personnel who are carefully selected and

trained for the task.

The public firm’s financial statements are to be

reviewed by independent external auditors. The firm’s

external auditors have a duty to be objective in their

review of the firm’s financial statements. While it is the

responsibility of the firm’s management to prepare the

financial reports, it is the responsibility of the firm’s

external auditors to express an opinion on these financial

statements based on their independent audit. The auditors

are expected to perform the audit to obtain reasonable

assurance that the financial statements are free from

material misstatement. The auditors are required to opine

if the financial statements prepared by management fairly

present, in all material respects, the financial position of

the firm and its subsidiaries on a given date. It is the

responsibility of Wall Street analysts to provide an honest

and unbiased evaluation of a firm’s performance and

prospects when they issue buy, sell, or hold recommenda-

tions on the stock of a firm.

Despite all the checks and balances provided for in the

U.S. corporate governance system as discussed above,

Enron collapsed under the burden of its accounting

scandals, just as its accountant Sherron Watkins warned

in internal memos to the CEO Kenneth Lay and its

external auditors, in August 2002 (Hamburger and Brown

2002). The Enron case exemplifies the great harm an

accounting scandal and a large corporate bankruptcy can

wreak upon society and its members.

Enron History

In July of 1985, Houston Natural Gas Inc. merged with

Inter North Inc., a natural gas company based in Omaha,

Nebraska, to form Enron an interstate and intrastate

natural gas pipeline company. In 1989, Enron began

trading natural gas commodities. In just a few years,

Enron became the largest natural gas merchant in North

America and the United Kingdom. Guided by the strate-

gic advice provided by world-renowned business consult-

ants McKinsey and Company (McKinsey), and the

leadership of its former CEO, Jeffrey Skilling (a former

employee of McKinsey), Enron transformed itself from

an energy company to a risk management firm that traded

Sridharan, Dickes, and Caines

13

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

everything from commodities to derivatives. Enron’s

consultants may have advised Enron to pursue a strategy

of building a large firm with very few real assets on its

balance sheet. The use of special purpose entities (SPEs)

allowed Enron to operate extensive undercover and risky

trading operations in a manner that did not properly

reflect their debt on its balance sheets. The ‘asset-light’

strategy, the SPEs, and the off-balance-sheet financing

they provided to Enron appear to be the root cause of

Enron’s eventual failure.

firm reported a $638 million third-quarter loss and

disclosed a $1.2 billion reduction in shareholder equity,

partly related to SPEs run by CFO Andrew Fastow. This

disclosure brought closer attention to the manner in which

Enron was financing its operations. Thereafter, a quick

downward spiral in the stock price of the firm ensued as

additional disclosures followed. On October 22, 2001,

Enron acknowledged that the SEC was inquiring into a

possible conflict of interest related to the company’s

dealings with its SPEs. On November 8, 2001, Enron

filed documents with the SEC revising its financial

statements for the past five years to account for $586

million in losses. Faced with the possibility of a down-

grade in its credit rating and a consequent cash shortage,

Enron’s management attempted to sell Enron to energy

rival, Dynegy, who initially agreed to buy Enron for over

$8 billion in stock. However, Dynegy backed out of the

merger agreement on November 28, 2001 shortly after

independent credit agencies downgraded Enron’s debt to

junk status to reflect Enron’s rapidly deteriorating

financial condition. This led to the final collapse in the

price of Enron stock that thereafter traded below one

dollar per share after trading as high as $90 per share.

Enron was forced to seek protection under Chapter 11 of

the US Bankruptcy code on December 2, 2001. The firm

was eventually de-listed from the prestigious New York

Stock Exchange.

Social Impact of the Enron Bankruptcy

As the value of Enron stock plunged in value, many

Enron employees lost their jobs and nearly all of their

retirement savings. In their testimony before Congress,

former Enron employees testified that while they had

retired with $700,000 to $2 million in Enron stock, they

now had virtually nothing except their social security

funds. To make matters worse, many of these employees

were restricted from selling their stock even as the stock

price declined in value, while senior officers of the firm

were able to sell their Enron stock without similar

restrictions (Schultz 2002). The issues of restricting stock

sales and the percentage of stock held in individual

401(K) plans are some of the many troubling issues to

emerge from the Enron crisis.

The steep financial losses and loss of jobs is not

limited to the employees of Enron. Over 28,000 employ-

ees at Andersen’s U.S. operations, many of whom were

completely uninvolved with the Enron audit, are at risk of

losing their jobs and thousands of Andersen employees

have already been laid off. Around 1,750 Andersen

partners may lose most of their entire life savings as the

ongoing financial viability of the auditing firm is in

jeopardy (Dugan and Spurgeon 2002; Bryan-Low 2002).

Following the release of the Powers Report, it appears the

Justice department focused immediate and greater

attention on the role of Andersen in this corporate

GAAP requires a firm to consolidate the financial

statements of an SPE with the firm’s own financial

statements unless the following two conditions are met:

a. The SPE has to have an independent owner with a

minimum of 3 percent equity capital at risk through-

out the transaction.

b. The independent owner has to exercise control of the

SPE (Hancock and Britt 2002).

Enron’s external auditors Andersen LLP (Andersen)

approved Enron’s use of SPEs. However, some of

Enron’s SPEs did not meet GAAP non-consolidation

rules. Enron’s use of SPEs and the manner in which

Enron accounted for them made Enron’s financial

statements very complex and difficult to understand. The

SPEs also provided rich rewards to some of its officers,

including the firm’s former Chief Financial Officer

(CFO), Andrew Fastow. Andersen performed both the

external and the internal audits for Enron and also served

Enron as a consultant in non-audit and tax matters.

Andersen’s three-way relationship with Enron created the

possibility for several conflicts of interest.

On the political front, Enron, its chairman Kenneth

Lay, and its auditors contributed generously to the

campaigns of many politicians in both major political

parties in the United States (Watts 2001; Adamson 2002;

Spain 2002a, b). Its political donations may have given

Enron some political power and some influence over the

formulation of a U.S. energy policy favorable to the

company. Despite its strong political connections and

high visibility, the hazardous nature of its capital struc-

ture strategy and its risk management business essen-

tially made Enron a firm built on very weak financial

foundations.

The first sign of weakness in the firm’s financial

structure became obvious on October 16, 2001 when the

The ‘asset-light’ strategy, the SPEs,

and the off-balance-sheet financing …

appear to be the root cause of Enron’s

eventual failure.

Sridharan, Dickes, and Caines

14

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

accounting scandal. In March 2002, the Justice depart-

ment indicted Andersen, the entire auditing firm, not just

individual auditors at Andersen, for obstruction of justice

when they shred documents relating to the Enron audit. It

is noteworthy that similar indictments have not yet been

issued for the top managers at Enron. Following this

indictment of Andersen, the trickle of corporate clients

dropping Andersen as their external auditor of choice

became a flood. By April 8, 2002, Andersen had lost

around 150 U.S. public clients, which will have an

immediate and severe negative impact on its revenues.

Andersen’s chances of winning a favorable settlement

with the Justice Department was greatly reduced when

David Duncan, the lead Andersen partner involved in the

Enron audit, pled guilty on April 9, 2002 to criminal

obstruction of justice charges due to his involvement in

Enron-related document shredding. On April 19, 2002,

Andersen broke off settlement talks with the Justice

Department. The case is expected to go to trial in Hous-

ton, Texas, on May 6, 2002. If Andersen is convicted of

obstruction of justice, it would be extremely difficult for

the firm to survive because the firm would be unable to

continue to audit publicly owned firms without obtaining

a waiver from the SEC. Even without a criminal convic-

tion, following the example set by the Arizona state

board, several other state accounting boards may revoke

Andersen’s licenses, without which Andersen will be

unable to practice in such states. Following the Justice

Department’s indictment of Andersen, several additional

lawsuits have been filed against Andersen by sharehold-

ers of Enron who seek to hold Andersen accountable for

Enron’s audits. The financial losses due to loss of

business with the departure of clients, the potential

liability from an SEC investigation and the Justice

Department’s indictment and numerous lawsuits raise the

odds that the Enron bankruptcy will bring about the

bankruptcy of its external auditor. This will clearly hurt

many Enron and Andersen stakeholders, including those

not directly involved with the accounting scandal.

The sharp and sudden decline in the value of Enron

stock adversely affected the retirement savings of thou-

sands of ordinary Americans who had no direct connec-

tion with the firm. Many Americans invest their retire-

ment savings in mutual funds and especially in index

funds because of their relative safety and reliable perfor-

mance. Enron was a member of the Standard and Poors

(S&P) 500 Index until November 29, 2001. All Index

funds seek to replicate the performance of their Index.

Therefore, over twenty-five mutual funds listed in the

S&P 500 Index had to include Enron stock in their

investment portfolios until Enron was removed from the

S&P 500 Index. Because Enron was dropped so late from

the S&P 500 Index, many individual investors who

invested in index-funds lost money because by the time

Enron was dropped from the S&P 500 Index, the stock

had lost over 99 percent of its market value. To the extent

index funds reduced their holdings of Enron as the market

value of the firm fell, they would have been able to cut

their losses. However, they could not completely elimi-

nate their exposure to Enron as long as Enron was in the

Index. There were also many other actively managed

portfolios, including those of many university foundations

(such as the investment portfolio of the University of

California), which had substantial exposure to Enron.

Portfolio managers of some of these investment funds did

not in fact reduce their exposure to Enron as its stock

price fell. Some asset management companies even used

the price decline as an opportunity to add to their posi-

tions. For example, Alliance Capital Management

(Alliance), the investment manager for the Florida

Retirement System (FRS), bought 4.9 million shares of

Enron for FRS between August and November 2001.

Two days before Enron filed for bankruptcy, Alliance

sold 7.5 million shares of Enron. Alliance was the asset

management firm with the largest exposure to Enron

(see Table 2). Estimates of losses in FRS’ portfolio

holdings of Enron range from $281 million to $321

million. FRS fired Alliance in December 2001. The

American Federation of State, County and Municipal

Employees, one of the largest public employee unions in

the US, is currently investigating why the Florida State

Board permitted Alliance to continue buying Enron

shares even after the SEC investigation into Enron was

announced in October 2001.

Mutual funds are only required to release complete

lists of their holdings twice a year. Therefore, it is

difficult to precisely identify how many other actively

managed funds also held Enron stock in their portfolios.

It is known that many reputable mutual fund companies

including Janus, Alliance, Putnam, Aim, Fidelity, and

Vanguard families of mutual funds held substantial

amounts of Enron stock (See Tables 1 and 2, and Wiser

2001). Enron stock formed part of the investment portfo-

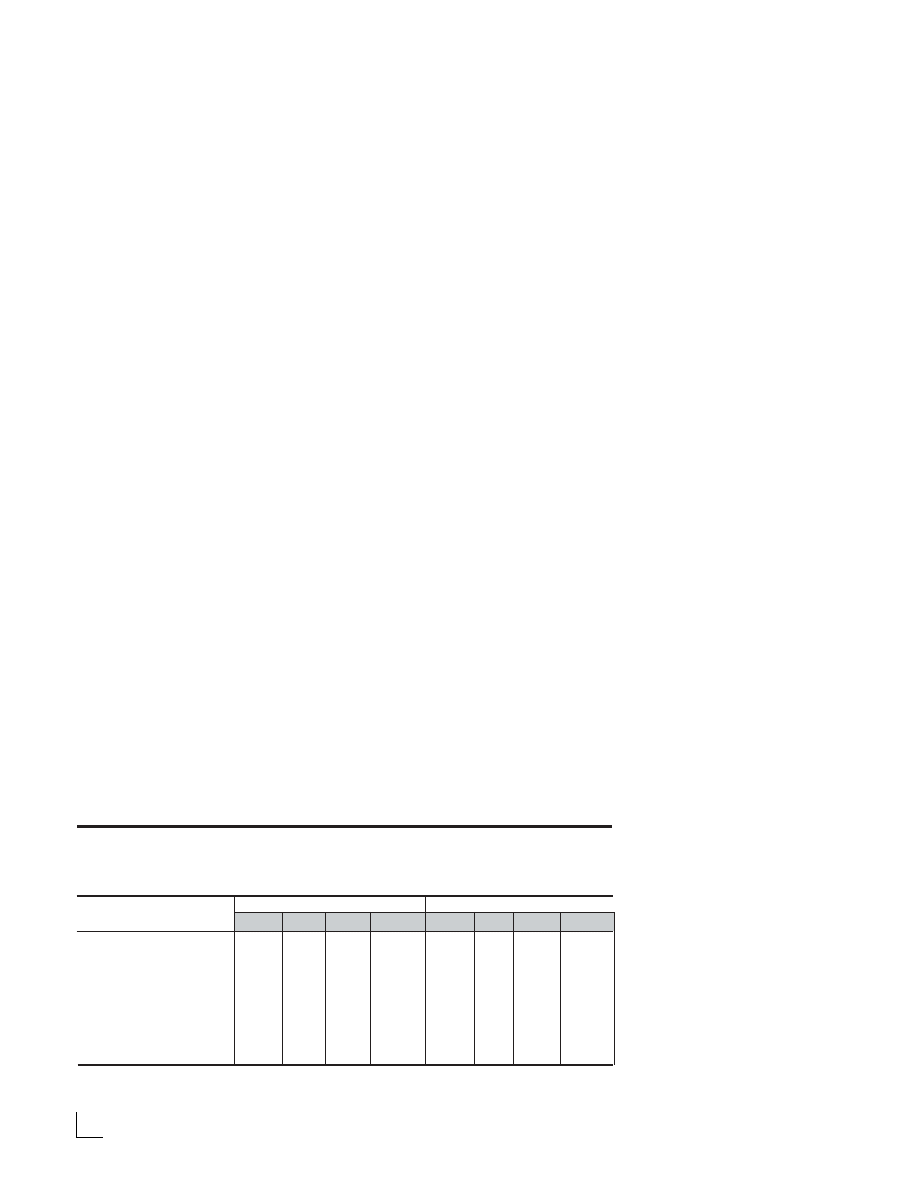

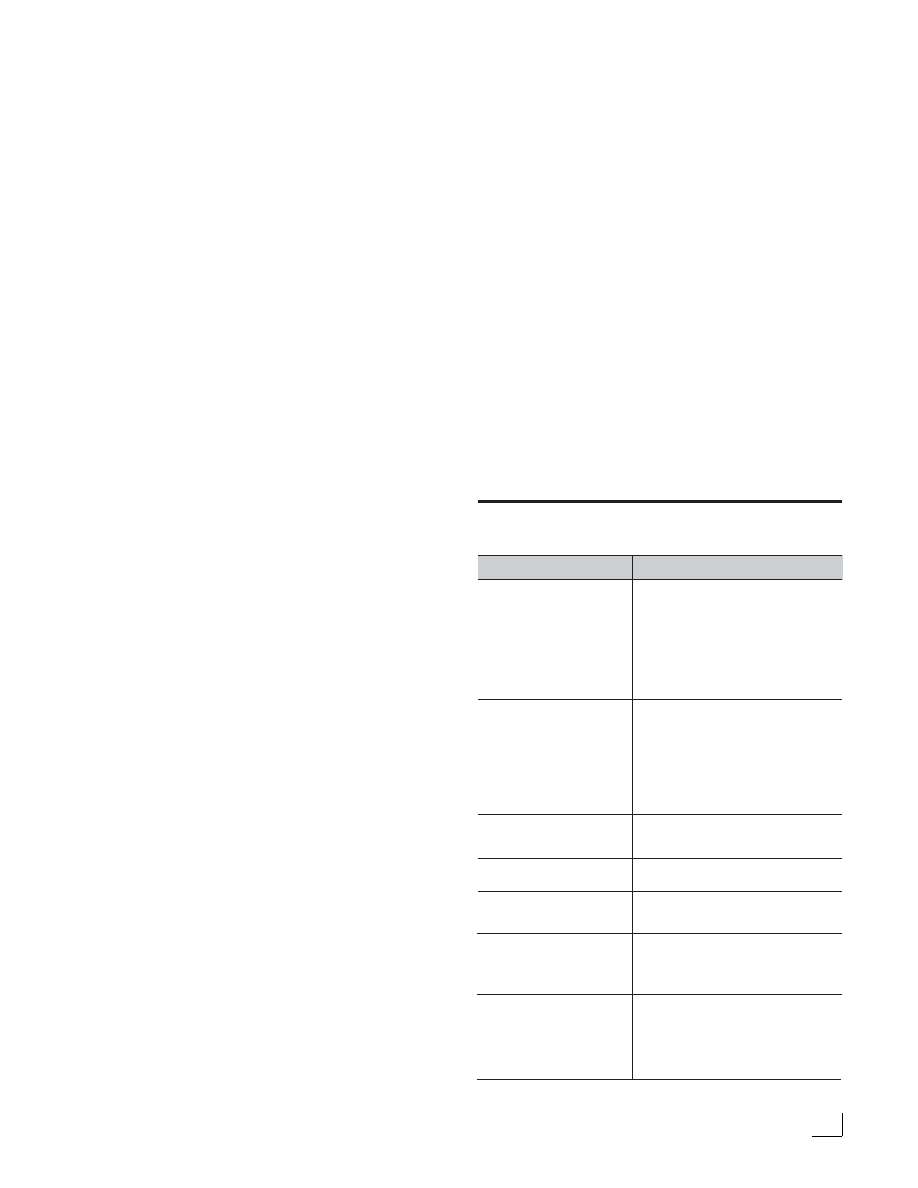

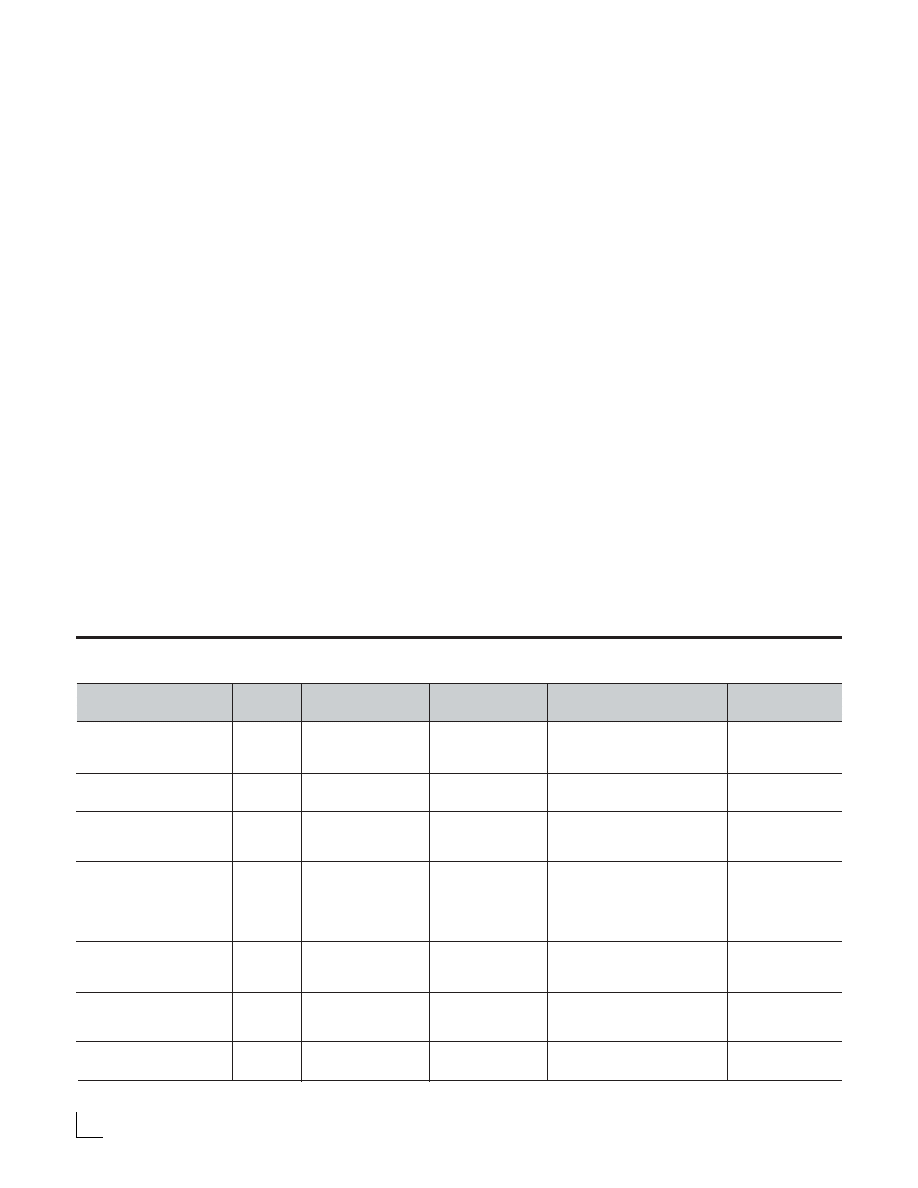

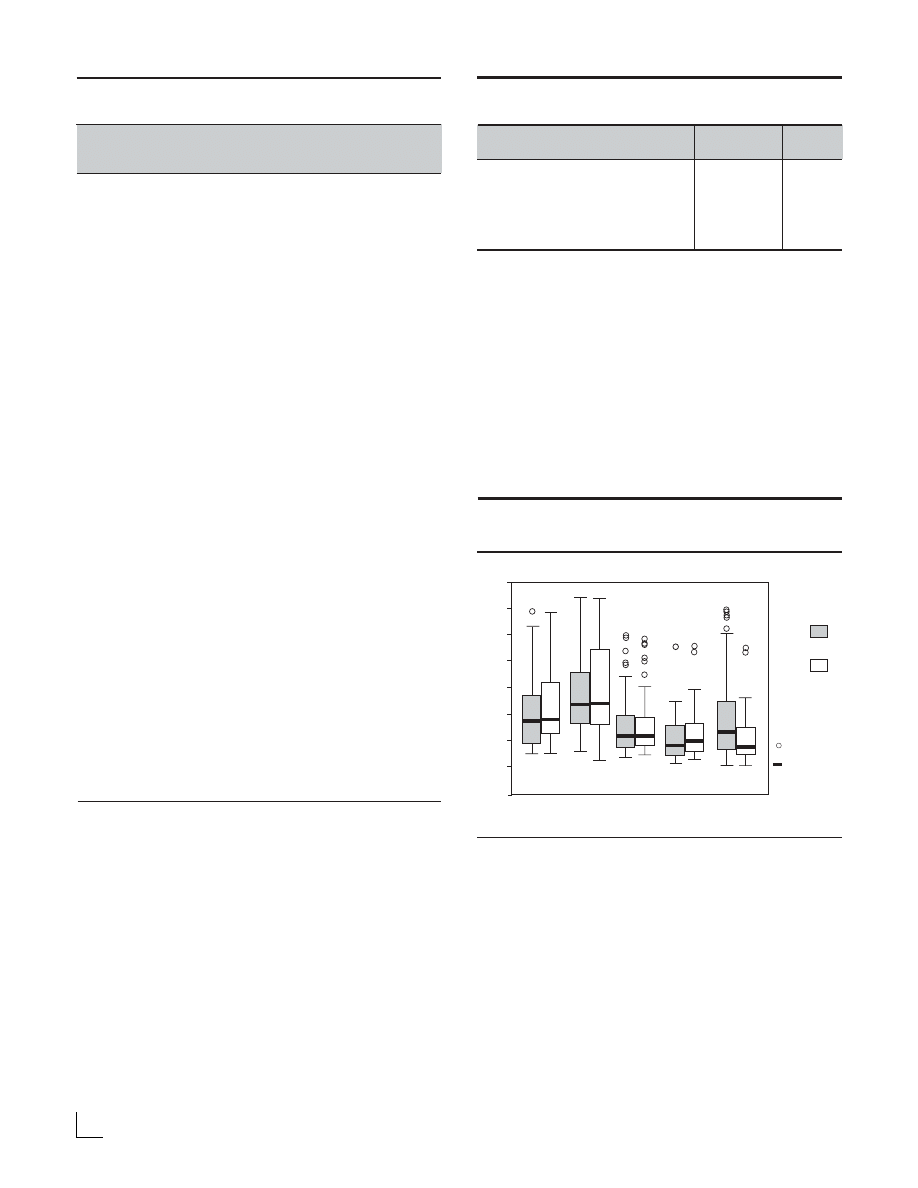

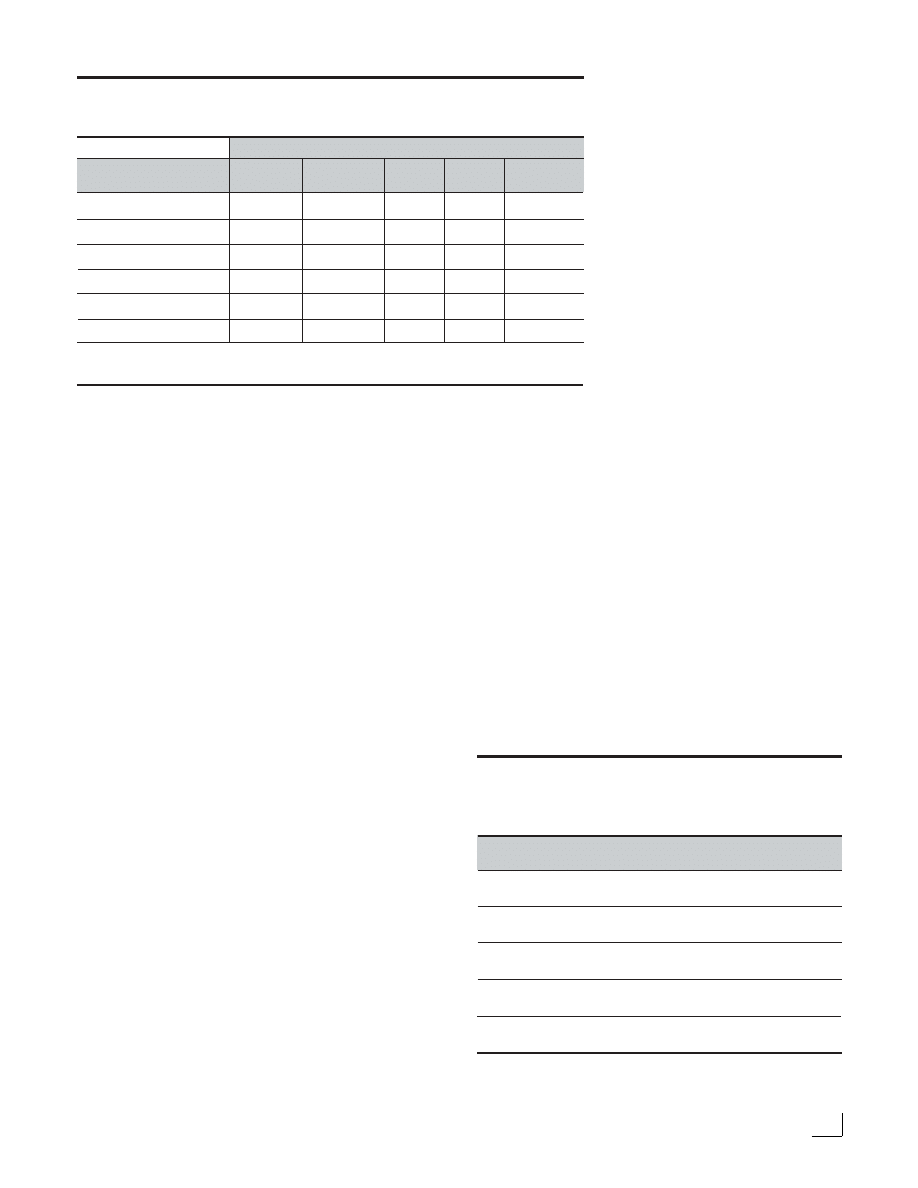

Table 1

Mutual Fund Holdings of Enron as of August 31, 2001

Galaxy II Utility Index

Utility

6.97

iShares Dow Jones U.S. Utilities

Utility

6.51

Fidelity Select Natural Gas

Natural Resources

5.69

AIM Global Infrastructure

Global

4.02

Goldman Sachs Research Select

Large-Cap Growth

3.43

MFS Utilities

Utility

2.17

SM&R Growth

Large-Cap Core

2.15

Federated Utility

Utility

1.50

Morgan Stanley Global Utilities

Utility

1.40

Deutsche Top 50 U.S.

Large-Cap Growth

1.40

Source: Lipper, based on annual and semi-annual reports

as of Aug. 31, 2001

Lipper Fund

Enron as % of

Funds

Classification

Fund’s Assets, 8/31

Sridharan, Dickes, and Caines

15

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

lios of several state pension plans, university and other

non-profit foundations. As of June 20, 2001, the Teachers

Retirement System of Texas owned 2.2 million shares and

CALPERS held 3 million shares (Wiser 2001.)

Portfolio managers of the funds that held Enron had a

fiduciary responsibility to make safe and knowledgeable

investments. In order to accomplish this, portfolio

managers had an additional responsibility to adequately

scrutinize all documents a firm files with the SEC before

they invest in the firm. Although financial statements

provided by Enron were allegedly lacking in financial

transparency, a prudent financial manager should have

refrained from investing in any firm whose financial

statements he/she did not fully comprehend. Portfolio

managers failed in their fiduciary responsibility to keep

individual investors’ funds safe when they invested in

Enron if they did not properly understand how the firm

made the profits it reported. The social impact of this

failure in fiduciary responsibility is reflected in the

millions of dollars lost in Enron stock investments by

individual and institutional investors. Many of Enron’s

trading partners such as Citigroup and J.P. Morgan also

suffered steep losses because of the Enron collapse and

within days of the Enron bankruptcy filing provided the

public and their stakeholders with preliminary estimates

of their Enron exposure (See Table 3).

Causes and Consequences of Multiple

Failures

The failure of Enron was a result of a combined failure

on several fronts. It was a failure of the high-risk, asset-

light business and financial strategy pursued by Enron

presumably under the advisement of its business consult-

ants, McKinsey and Company. The Wall Street Journal

reports that McKinsey and Company, in an internal

document, praised Enron’s use of “off balance sheet

funds using institutional investment money [which]

fostered its securitization skills and granted it access to

capital at below the hurdle rates of major oil companies”

(Hwang 2002, B1). The consultants deny being involved

in the review of decisions made about Enron’s invest-

ments, yet McKinsey and Company served as advisors to

Enron’s board of directors in the year preceding Enron’s

bankruptcy filing and at least one senior partner from the

consulting firm attended six board meetings at Enron

from October 2000 to October 2001. At these board

meetings, the former Enron CEO Jeffrey Skilling report-

edly emphasized the need for SPEs to help bolster the

firm’s growth (Hwang 2002). If Enron’s balance sheet

had contained a greater proportion of tangible and

especially fixed assets with stable market values, the

market value of the firm may not have collapsed as it did,

and the fixed assets could have been sold to meet its

financial obligations.

There are many levels of blame in this corporate crisis.

Enron’s top managers are clearly responsible for poor

business decisions and mismanagement of the corpora-

tion. Not surprisingly, when required to testify before the

U.S. Congress on the reasons for Enron’s collapse, most

of Enron’s managers sought refuge under the Fifth

Amendment. Decisions that individuals and corporations

make often have multiple, systemic effects. Often,

individual decision makers underestimate the conse-

quences that follow from their decisions. When the

governing bodies of corporations do not understand, or

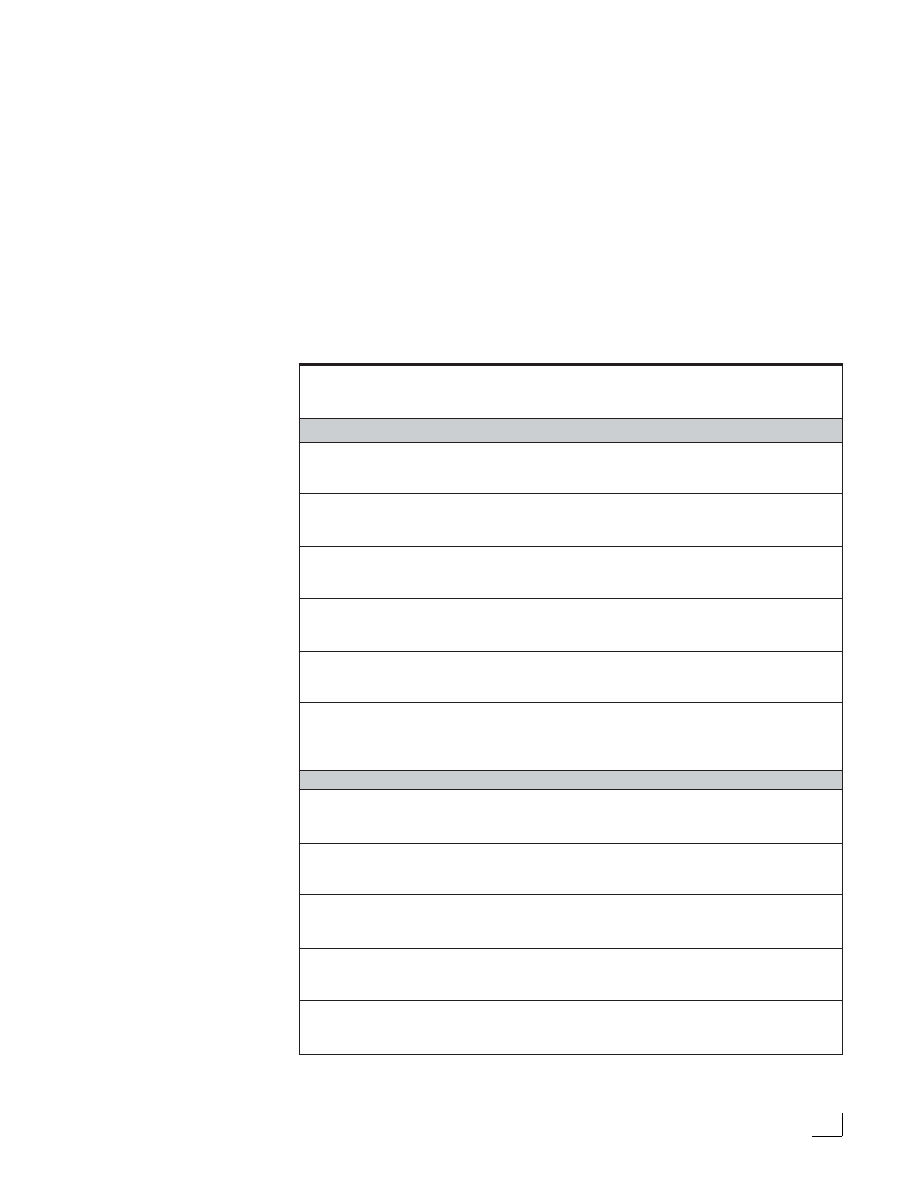

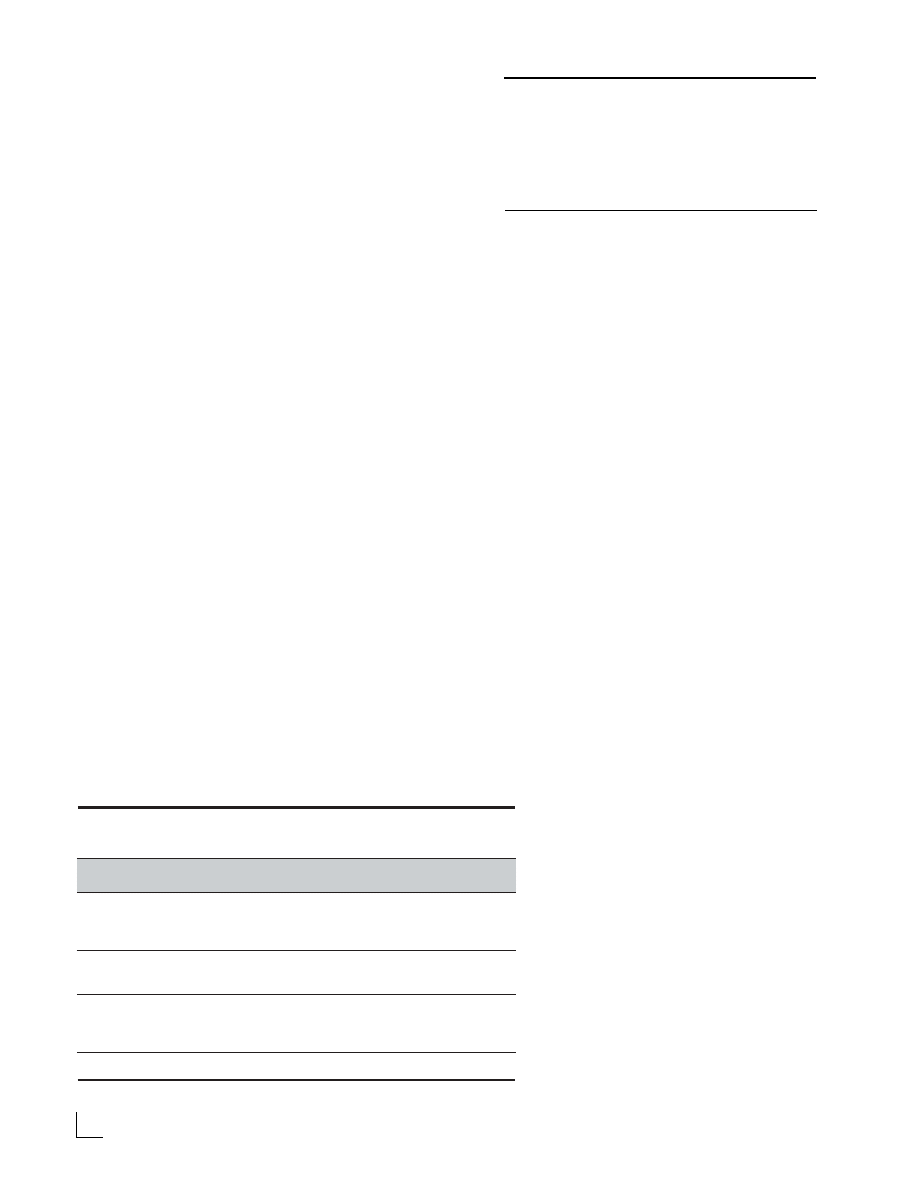

Table 2

Selected Institutional Holdings of Enron

as of September 30, 2001

Alliance Capital

42.94 million

Janus Capital

41.4 million

Putnam

23.1 million

Barclays Global

23.1 million

Fidelity

20.8 million

Smith Barney

19.4 million

State Street

16.1 million

Aim

14.0 million

Vanguard

11.4 million

Morgan Stanley

10.1 million

Source: CBS Marketwatch.com, November 28, 2001

Number of Enron Shares

Institutions

Held 9/30/2001

Bear Stearns

$69 million

ABN Amro

110 million Euro

ING Barings

$195 million

PPL

$10 million

Chubb

$220 million

Aegon

$300 million

Candian Imperial Bank

$215 million

of Commerce CIBC

Credit Lyonnais

$259 million

Duke Power

$100 million

Centrica

$30 million

Deutsche Bank

less than $ 100 million

RWE Trading

10-11 million Euro

Sempra

less than $15 million

J P Morgan

$2.6 billion

Citigroup

$260 million or more

American Electric Power

$50 million

ONEOK

$40 million

Source: Wall Street Journal Reports, October to December 2001

Table 3

Number of Enron Shares Held

Preliminary Estimates of Exposure to Enron

Exposure to Enron

Amount

Sridharan, Dickes, and Caines

16

Mid-American Journal of Business, Vol. 17, No. 2

take account of all future consequences, serious moral

hazards result. Messick and Bazerman (1996) argue that

potential consequences are often ignored because of five

possible biases: ignoring low probability events, limiting

the search for stakeholders, ignoring the possibility that

the public will find out, discounting the future, and

undervaluing collective outcomes. It now appears that

Enron management and the Board maintained all of the

five biases to some extent. The many decision makers

involved with Enron would have better served all stake-

holders if they had considered the full spectrum of

consequences associated with their decisions (Messick

and Bazerman 1996, p.3).

2002). According to the Powers Report, some of the

involvement of the Enron officers in some SPEs may not

have been fully disclosed to either Enron’s Chairman and

CEO, Kenneth Lay, or to the Board of Directors. The

Board approved the CFO’s participation in the SPEs with

full knowledge of the potential conflict of interest.

However, the Enron Board believed that the conflict of

interest and the risks associated with it could be moni-

tored effectively by oversight provided by senior manage-