CLASSROOMS AND

BARROOMS

DAVID J. JACKSON

CLASSROOMS AND BARROOMS

JACKSON

HAMILTON BOOKS

In Classrooms and Barrooms, David J. Jackson recounts his experiences during a

semester-long Fulbright Fellowship in Poland where he taught classes at the

university level and learned more about Poland and himself than he expected.

From the trepidation associated with learning he was assigned to teach in a city

considered by most to be an unpleasant wasteland to meeting American and

Polish colleagues for the first time, Jackson’s worries vanished as he quickly

learned to accept the challenges Poland presented. Halfway through his time

in Poland he stumbled into a bar populated with an ever-changing cast of

eccentric locals who welcomed him into their world. Each visit led him to

another revelation about Polish history and culture.Alternating among hilarious,

somber, and uplifting, Jackson’s experiences in the classrooms and barrooms of

Poland aim both to inform and entertain.

David J. Jackson

is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political

Science at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. From October 2007 to

February 2008, he was a Fulbright Fellow in the Department of American

Studies and Mass Media at the University of Lódz in Poland. Jackson is also

the author of Entertainment and Politics: The Influence of Pop Culture on Young

Adult Political Socialization and numerous articles in scholarly journals.

For orders and information please contact the publisher

HAMILTON BOOKS

A member of the Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200

Lanham, Maryland 20706

1-800-462-6420

www.hamilton-books.com

An American in Poland

ClassroomsBarroomsPODPBK.qxd 1/21/09 2:30 PM Page 1

Classrooms and Barrooms

An American in Poland

David J. Jackson

H A M I L T O N B O O K S

A member of

T H E R O W M A N & L I T T L E F I E L D P U B L I S H I N G G R O U P

Lanham

•

Boulder

•

New York

•

Toronto

•

Plymouth, UK

Copyright © 2009 by

Hamilton Books

4501 Forbes Boulevard

Suite 200

Lanham, Maryland 20706

Hamilton Books Acquisitions Department (301) 459-3366

Estover Road

Plymouth PL6 7PY

United Kingdom

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

British Library Cataloging in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008942001

ISBN: 978-0-7618-4383-2 (paperback : alk. paper)

eISBN: 978-0-7618-4384-9

⬁

™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum

requirements of American National Standard for Information

Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials,

ANSI Z39.48—1984

To My Family

v

Acknowledgments vii

Introduction: City of Colors

ix

1 Kresowa 1

2 Choosing

Łódź, Heading for Wrocław 7

3 Return to Kresowa

16

4 (Dis)Orientation 20

5 Friendly Fulbrighters

26

6 To Work in

Łódź 31

7 Meanwhile, Back at Kresowa

36

8 Poland for the First Time

42

9 Names and Pictures

47

10 Polka, Polka, Polka

51

11 A Great Day of Teaching

56

12 Warsaw, London, and Oxfordshire

61

13 Another Bar

67

14 A Day on Piotrkowska Street

70

15 Wigilia 74

16 My Grandfather’s People

80

Contents

17

Comments 84

18

Fitting In

88

19

Christmas and Boxing Day

94

20

Poland, Slovenia, and Austria

98

21

Fighting Poland

103

22

Three Good Classes

107

23

Zbyskuuuu . . .

114

24

Breaking Glass

118

25

Firsts and Lasts

121

Conclusion: Warsaw One More Time

127

References 131

vi

Contents

vii

There are many individuals and organizations I must thank for their positive

contributions to this work.

First, of course, I could not have had the experiences I write about in this

book without the Fulbright Grant, so I thank the Polish-U.S. Fulbright Com-

mission and the Council for the International Exchange of Scholars. I also

thank the Department of American Studies and Mass Media at the University

of

Łódź for inviting me to teach in their fine program. I especially thank

El

żbieta H. Oleksy and Wiesław Oleksy for helping to make my Fulbright

semester happen. I wouldn’t have thrived without the friendship and help

of colleagues in

Łódź as well, including Paulina Matera, Aleksandra M.

Ró

żalska, Dorota Golańska, Magdalena Marczuk-Karbownik, Beata Duchno-

wicz, and David LaFrance. Of course, there is no teaching without students,

so I thank the 132 students I had the pleasure to teach American politics to

for their curiosity and intelligence.

Many of my family and friends in the U.S. read chapters of the book in vari-

ous stages of completeness and offered helpful comments. These include my

parents Jim and Barb Jackson, as well as my brother and sister Jim and Jean

Jackson. My sister in law Kendra Jackson read them as well. Others who offered

insights include Candace Archer, Stefan Fritsch, Becky Mancuso, Jim Fracassa,

Moira Fracassa, Julie Jozwiak, Steve Florek, Elena Fracassa, Kathy Bruce,

Glen Biglaiser, John Fischer, Marc Simon, Maria Simon, Becky Lentz-Paskvan,

Mark Jakubowski, Fred Sampson, Randy Krajewski, Margaret Dramczyk, Su-

sana Peña, Tony Martinico, Steve Engel, Eleanor Lazowski, and Sherri Cherry.

David Wilson deserves special thanks for reading the completed manu-

script and making hundreds of helpful suggestions. He is a great editor and

friend. Becky Lentz-Paskvan read it all too, and made many helpful correc-

tions. Any errors are the fault of the author.

Acknowledgments

ix

From September, 2007 to February, 2008, I taught political science courses

in the Department of American Studies and Mass Media at the University

of

Łódź in Poland as a Fulbright Fellow. I found the experience incredibly

rewarding in terms of my teaching, my interactions with Polish colleagues

and other American Fulbrighters, and most importantly, the relationships I

developed with the Poles I met outside the classroom.

Fulbright awards are often misunderstood. I certainly misunderstood the

program before I applied for one. The majority of Fulbrights are given to

professors for the purpose of teaching. I had always thought that most of

them were research-oriented grants to go to another country and study it, but

I was wrong. I also didn’t know how difficult it is to win a Fulbright because

the commission is pretty secretive about the acceptance rates. But I do know

that the goals of the program are very noble. According to the Council for the

International Exchange of Scholars, which administers the program, Senator

Fulbright proposed the exchanges in order to promote “mutual understanding

between the people of the United States and the people of other countries of

the world.” I certainly tried to acquire and promote that understanding while

I was in Poland.

Eastern Europe is considered by some people to be something of a “conso-

lation prize” in the Fulbright sweepstakes, in that awards in Western Europe

are much more difficult to win. In other words, the Commission might say:

well, you wanted to go to Germany, England or France, but they couldn’t fit

you in, so how about Slovakia? I know something like that happened when

a professor from Ohio applied to teach in Finland, but was offered Estonia

instead. What the heck, the Fulbright Commission seems to have thought, the

Baltic is the Baltic.

Introduction: City of Colors

x

Introduction: City of Colors

On the other hand, none of the Fulbrighters I met in Poland had been sent

there as their second choice. In fact, each had specific reasons for wanting to

teach, do research, or make films in Poland. So, who knows?

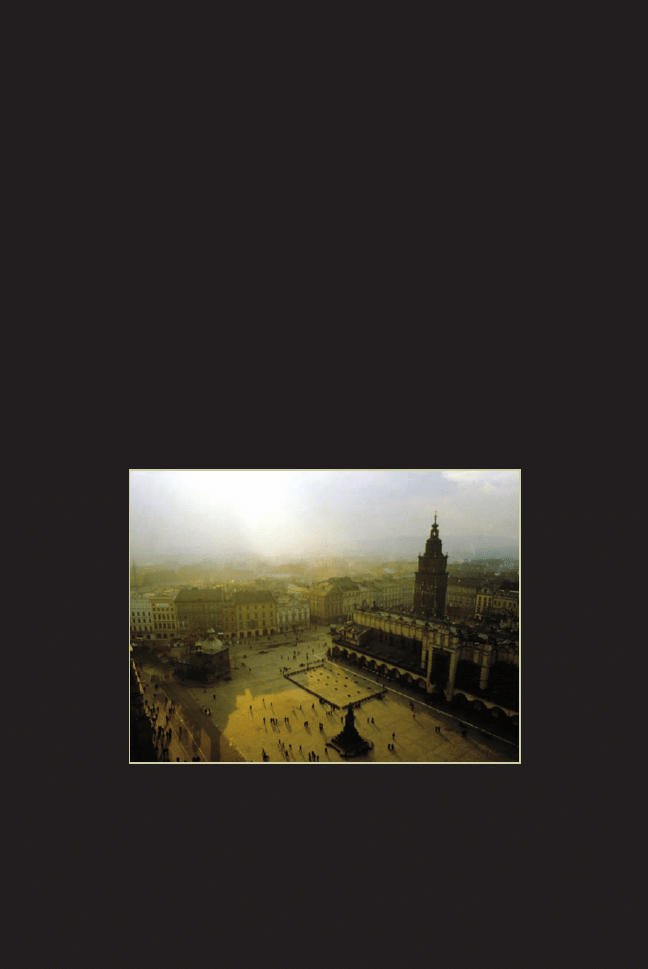

I do know that the Polish city I was offered a Fulbright is considered by

many to be the “booby prize” of that country because a former Fulbrighter

who taught there told me so. I know this also because I know something about

Poland’s cities. Kraków in the south is a charming, medieval university town

with Europe’s second oldest university; Warsaw is a bustling world capital;

Gda

ńsk in the north is a city rich in history, famously as the center of the

Solidarity movement that helped to topple communism; Pozna

ń in the west

is a thriving, business-driven city with more than a little German influence.

On the other hand,

Łódź is…well, none of the above.

The facts of

Łódź are pretty simple: Poland’s second largest city is the

down-on-its-luck former textile capital of the country. Over 800,000 people

live in this relatively young city that grew up with the industrial age. It is

not a medieval city; there is no central square. At one time it was known as

the city of the “four cultures”—Polish, German, Jewish and Russian. But no

more. Almost all of the city’s inhabitants are now ethnic Poles. Among the

last vestiges of its cosmopolitan past are a very large Jewish cemetery and

a few Russian Orthodox churches. Its architecture ranges from ghastly com-

munist-era apartment blocks to the charming Art Nouveau of the main street,

Piotrkowska.

Some less objective descriptions tell a bit more of the real story.

One of

Łódź’s most famous nicknames is the Manchester of Poland. Some

Americans have called it the Cleveland or Pittsburgh of Poland.

One guide book calls

Łódź gritty, sprawling and unpleasant.

A former Fulbrighter who actually liked the place said, “

Łódź is a city of

colors: grey, grayish, dark grey, light grey . . .”

A student I know who studied Polish there said, “It doesn’t give you much

to like, but I love it.”

For five months I lived and taught in this unique place called

Łódź, Poland.

While I was there I took notes about my experiences: from the sometimes

disorienting orientation in September, to the sad flight back to the States in

February; from the challenges presented by insane Polish bureaucracies, to

occasional triumphs in the classroom; from chance encounters with Poles and

Americans on the streets and in lines at kiosks, to the development of a real

friendship with the bartender at the most political pub I have ever frequented.

Those experiences and many more are recounted in these pages.

But first things first. The stories I present here are not at all literal transcrip-

tions of exactly what happened. While I made every attempt to accurately

write about my experiences in Poland, I did not record conversations or take

Introduction: City of Colors xi

notes as things happened. Often I recalled them days or weeks later. Some-

times I combined in one story events that in fact occurred over two or three

nights. Sometimes I changed names and minor details to protect people’s

identities. But these stories do accurately reflect the spirit if always the letter

of my time in Poland. So, while not a work of journalism, I believe this is a

work of truth nonetheless.

Also, I make no claims that these experiences are somehow reflective or

representative of the “real” Poland, whatever that might mean. Somebody

else going to the same places I visited in Poland will likely have very dif-

ferent experiences. These are just some very interesting things that I did,

and that I wanted to write down. In his excellent, and controversial, work A

Russian Journal, John Steinbeck cautions his readers that he has not written

“the” Russian story, but merely “a” Russian story. I believe that is true of my

stories of Poland.

Steinbeck also had to admit that his Russian Journal was a somewhat

superficial work, and I must confess the same thing. My time in Poland was

relatively short, and my lack of language skills limited me to certain kinds of

experiences. I believe many of them are very interesting and even insightful,

but I know they would have been very different had I stayed longer and been

able to speak the language. But Steinbeck was also limited by the communist

government in terms of who and where he was allowed to visit. I faced no

such limitations, and I made a real effort during my time in Poland to go to

places where I would find interesting people who might tell me the truth.

I should also note that while the stories presented here form a more or less

linear tale of what happened during my time in Poland as a Fulbright Lec-

turer, I have also included some material about my previous visits to Poland,

my ancestral connections with the place, as well as some thoughts concerning

sentimentality and coincidences that came up when I was just starting to write

about my time in

Łódź. If the book sometimes has more of an episodic rather

than thematic feel, it is because just about every chapter was written in such

a way that it could also stand alone as a vignette about some matter involving

my interpretation of things Polish.

It will be evident that I loved my time in Poland, so it is important to point

out that I am very far from an objective observer of things Polish and Pol-

ish-American (a distinction whose significance to me has grown greatly due

to my time in the Motherland). My mother’s ancestry is one hundred percent

Polish-American and I was raised in a family steeped in Polish-American

traditions: Sunday morning polka radio; home-made kie

łbasa at Christmas

and Easter; close attention to Poland’s struggle for independence, and much,

much more. So I went to Poland as a sympathetic friend, and I returned as

one as well.

xii

Introduction: City of Colors

This is not to suggest that everything that I did in Poland was an unadul-

terated joy or that I do not have some complaints. Of course not. But I was

perhaps fated to enjoy things in Poland more than an American without Pol-

ish connections might have been. Of course, it might be that my expectations

and hopes were higher because of my Polish connections. So disappointment

might have been a greater possibility for me than for other American Ful-

brighters going to Poland. This possibility of being disappointed may keep

many Polish-Americans from visiting Poland: I hope the stories presented

here will help convince more people, including Polish-Americans, to visit.

And, I was not disappointed; not in the least. In fact, I kept waiting for

something truly bad to happen to me, and it never did. After I returned to the

U.S., I ate lunch with a colleague and she asked me which aspects I didn’t like

very much. I had no ready answer. The internet connection in my apartment

was unreliable sometimes? The students who lived above me occasionally

threw loud parties and played god-awful pop music? A few of the students

cheated on the final exam? Night fell at 4:00 P.M. in December? These are

irritations, not problems. Sometimes I think I should have stayed longer than

for just one semester.

Regret, now that’s a problem. I doubt that it would have been very difficult

to get an extension of my time in Poland, but I elected not to apply for one,

and sometimes I regret it. I came back home when I did because by doing so

I would have seven months where I did not have to teach a single class. There

were also a lot of good reasons to stay, but I eventually rejected them all.

When I first returned I felt pretty bad about the decision. I really felt like

I should have asked to stay, to teach for another semester. While I did ev-

erything I said I would do, and even a bit more, I still felt like I was leaving

something important behind, and unfinished. But during the conversation

with my colleague about what I didn’t like, I came up with a simile for how

I felt about my return, which helped me process my mixture of feelings into

something useful: it felt like breaking up.

But it felt like breaking up with a great woman without falling out of love.

In fact, we still have a great deal of affection for each other and plan to see

one another again in the very near future. Once I had a simile, I felt better,

and I felt like I wanted to re-live, or at least preserve the memory of the ex-

periences, and that’s why I wrote down all of this. Of course, I also thought

other people might find these experiences at least a little bit enlightening and

entertaining. But that is for the reader to decide.

1

“Do you like Litzmannstadt?” the old man asked.

I couldn’t believe he’d said it. Nobody calls “Łódź” that. That’s the name

the Nazis gave it after the conquest in 1939, after the German general who

tried (and failed) to take the city during the First World War.

“Jeszcze raz?” I said (“One more time?”)

“Do you like it here in Litzmannstadt?” he repeated.

“I like Łódź,” I said.

And so went one of my first conversations in a bar that would become my

home away from home during my Fulbright Lectureship at the University of

Łódź.

The day had begun auspiciously enough, given that it was my busy teaching

day: three hour-and-a-half lectures between 11:20 and 6:00. For some reason

I felt really happy on my way to classes. I’d bought some tram tickets at the

green “Ruch” kiosk and felt my usual pleasure at getting the right kind and

proper number (I’m not blaming the clerks for the occasional failure. The

villain is my very faulty Polish). The tram ride was uneventful, and after I’d

disembarked I’d stopped at a little store that seemed more down-and-out than

those around it, especially the clean and shining Żabka-chain convenience

store across the street. The little store was cold and dark and far from well-

stocked, but I decided to buy some grapes for lunch.

I didn’t want a full kilogram of grapes and I’d forgotten how to say “half”

and had left my pocket dictionary back in my apartment. I asked for grapes

and after the very old woman behind the counter said “how much?” in Polish

I placed my hands about two feet apart and said, “kilo.” Then I moved them to

about a foot apart, and waited. She said, “poł kilo” (“half a kilo”). I repeated

it and resolved to remember it. She smiled and packed up my grapes.

Chapter One

Kresowa

2

Chapter One

As I crossed the park in front of my office it seemed like there was less

dog poop than usual on the sidewalks. The sun wasn’t shining, but everything

felt bright anyway. Normally I do not feel this good on my way to classes,

in Poland or the U.S.A. My neurotic personality, even after fifteen years of

teaching, causes me to repeat in my head, “I hate teaching. Why do I do this?”

It’s an unproductive response to nerves, I suppose, but it’s gotten me through

so far. Then I always feel great after classes are finished. Whether they went

well or not I feel an incredible sense of relief, and if they went well (which

is often), I feel triumphant. Feeling good and happy before classes is not a

normal feeling for me.

Classes went well in an unspectacular kind of way. No obvious light bulbs

going off over students’ heads or incredibly clever metaphors from me; just

three solid, content-rich lectures. After my final class of the day, one of my

students invited me to Wigilia, Polish Christmas Eve, at her parents’ home. I

thought that was very cool of her and I looked forward to experiencing a truly

special Christmas with a Polish family.

I made my way to what at the time was my favorite Polish restaurant in

Łódź, and it was busy with people attending the international film festival

there, a great event for the city. But what was especially gratifying to me that

night was that the wait staff I’d dealt with before appeared to be happy to see

me, because I actually tried to speak some Polish with them. And, during less

busy times in the restaurant, I paid close attention to their instructions and

incorporated some of what they taught me into subsequent “conversations.”

After dinner, I decided to visit a bar called Kresowa, located on Narutow-

icza Street, just off Piotrkowska, which is the main drag in Łódź. Estimates

vary about how many bars, pubs and clubs are located on or near the three

kilometer pedestrian section of Piotrkowska, but a number I’ve heard more

than once is 165, and it seems plausible. I wanted to visit this particular bar

for two reasons.

First, my friend and fellow Fulbrighter Tony had recently asked me a

rather pointed question about whether I was meeting any Poles. I offered my

students and colleagues as evidence that I was, but I knew that wasn’t what

he had meant. He’s been coming to Poland for close to thirty years, and he

counts the friends he’s made outside of the professional setting as one of the

great joys of having spent so much time in the country. Where better to meet

real Poles than in real local a bar, I thought?

The second reason I chose this particular bar was because it came highly

recommended by the usually reliable and always sarcastic In Your Pocket

guide. Here is what they wrote about the place:

A locals bar with a mixed clientele from the lower rung of the social ladder.

Stained and stinking from years of beer and cigarettes this is the drinking expe-

Kresowa

3

rience Polski style; watch barflies playing chess while telling the story behind

their latest street-battle injury. Trams roar by outside the glass windows and

framed pictures of Poland’s ceded Eastern territories hang from scabby wallpa-

per. A great place to prop up the bar and listen to local drunks rant and ramble

about all that is wrong with the world. We love it.

How could I resist such a recommendation?

I almost didn’t make it inside the bar. The heavy glass and steel door was

very difficult to open, and I was so embarrassed by my hard push, its refusal

to budge, and the heads of the few men at the bar turning to watch me fail

that I almost walked away. I pushed harder and propelled myself, stumbling a

little, into a very dark and cold bar. Again, I almost turned around and walked

out. But I summoned the courage and sat down on one of the rickety wooden

barstools.

I sat next to an older man, maybe 65 or 70, who had his cell phone out

and was playing a tinny version of “The Logical Song” by Supertramp, and

talking with the bartender.

When I was young, it seemed that life was so wonderful,

A miracle, oh it was beautiful, magical.

And all the birds in the trees, well they’d be singing so happily,

Joyfully, playfully watching me.

But then they sent me away to teach me how to be sensible,

Logical, responsible, practical.

I don’t speak much Polish, but the combination of content clues and what I

do know made it obvious the old guy really loved his Supertramp, especially

this particular song.

The bartender looked to be in his mid forties, with thinning salt and pepper

hair and a tough scowl that seemed to say, “I dare you to try to order a beer.”

I instantly thought he looked like a journeyman bass player who’s always

available for one more small arena tour with the remnants of some 1970s rock

band. His strikingly beautiful black-haired lady-friend sat at the corner of the

bar smoking cigarettes and agreeing with the Supertramp fan.

The barkeep’s girlfriend tried to pacify the old man when a group of young

men sitting at the heavy wooden picnic-style tables began to play some truly

awful music on the jukebox. The young men wanted the bartender to turn

up the jukebox, but the sound remained about the same after he visited the

volume switch behind the bar.

I sat there for quite a few minutes just taking it all in and waiting for the

bartender to ask me what I wanted to drink. When he finally did ask me, he

met my request with scowls and grunts as if he didn’t understand my Polish. I

know my Polish is terrible, but I also know that I know how to order my first

4

Chapter One

beer, how to properly ask for another beer, how to say, “I feel like a beer”

and “gimme a beer,” and so on. In other words, I know how to ask for a beer

in Polish. Finally he pointed to a tap, I nodded, and he poured me a half-liter

of Warka, which cost five złoty, or about two dollars.

Everyone in the bar kept their coats on because the place was so cold. The

young men who played the jukebox talked pretty loudly and drank a few

shots of wódka, but they didn’t seem like they were interested in making any

trouble.

Finally, the old Supertramp fan said something to me in rapid Polish. I

replied with, “Przepraszam, nie rozumiem” (“I’m sorry, I don’t understand”).

This phrase became my constant refrain in Poland.

He responded in broken English (much less broken than my Polish) that he

thought it was okay I didn’t understand. He asked me where I was from, and

after I replied that I was an American, he said, “America bad.”

“Good and bad,” I answered.

Then he asked me to name my favorite American President.

“Franklin Roosevelt,” I said.

I was being deliberately provocative. I was warned by a former Fublrighter

that I could expect to get in many arguments with Polish professors if I

brought up F.D.R. They would argue that the Allies had sold out Poland to

the Soviets at Potsdam and Yalta, while most Americans would respond that

Stalin had committed to free elections for Eastern Europe (whether or not he

ever intended actually to deliver them), and that the deals were the best we

could have expected. As a Polish-American my sympathies are almost always

with the Poles on these questions, even if logic suggests that the Allies’ mili-

tarily taking on the Soviets in 1945 might not have been the best idea. But I

felt like provoking the Supertramp fan.

“F.D.R. good for America,” he replied, “much bad for Poland.”

At that the bartender became as friendly as he had previously been surly.

He began translating for me and the Supertramp fan. His attitude flipped like

a switch, and I didn’t (and still don’t) know why.

“Who do you think will be the next president?” he asked on behalf of the

old man.

I told him Barack Obama, but I really hadn’t formed an opinion. In fact,

avoiding part of the longest presidential election in U.S. history had become

one of my favorite parts of my time in Poland.

“No way,” he said through the bartender. Then, literally, “Sir wants you to

know America won’t elect a black man.”

“Please tell him I disagree,” I said, and the bartender complied. The drunk

dismissed me with a wave of his hand and a roll of his eyes.

Kresowa

5

“He says history will not change overnight,” the bartender said.

Then the bartender asked me why I was in Łódź. I answered that I was

a visiting professor at the University of Łódź. He wanted to know what

I teach and in what language: Political science and English, of course, I

answered.

Then a very fat man with a grey beard and blue suspenders walked in. The

barkeep told me he’s the boss man, the owner of the bar. The owner disap-

peared into the darker back section of the place, and a few minutes later some

lights came on and I could see the whole thing. The In Your Pocket guide

hadn’t been entirely correct. The pictures on the wall were not maps of lands

Poland had ceded after World War Two. They were pictures of Marshall

Józef Piłsudski, numerous prints of Piłsudski’s portrait, and one of the Mar-

shall on horseback. There was also a bronze relief of the great leader, a few

drawings and even a black and white photograph.

“Lewo or prawo?” the old man asked me, in reference to my politics—left

or right?

“Lewo,” I said.

“Don’t tell him,” he said and nodded across the bar to where the owner had

sat down to a cup of hot tea and a plate of steaming pierogi. He drank his tea

from a mug with the letters “PiS” printed on it—“Prawo i Sprawiedliwość” or

“Law and Justice,” the right-of-center political party defeated in the October

parliamentary elections.

“I won’t,” I said.

“It’s okay. You can,” the bartender assured me.

Then he wanted me to know that there was much more to him than just

tending bar in this Polish nationalist tavern: he is a musician, and he writes

and sings in English.

“I want to sing songs even better than Bob Dylan,” he said.

He even sang a couple of his songs for me. He just belted them out from

behind the bar. I thought he was pretty good, in a rough and bluesy way.

Sometimes it was hard to understand all of the lyrics, but his passion for his

songs was infectious, and so I liked them very much.

He asked me if I wanted a copy of his CD. I answered that of course I did.

He ran out to his car and got me the recording. His name was written on the

disc: Zbyszek Nowacki. I said his name out loud. He seemed very pleased

with my pronunciation, which is actually quite good, and often gets me in

trouble. Poles sometimes quite reasonably expect that I can speak more Pol-

ish than I can. His attitude was a 180 degree turnaround from less than an

hour before. Maybe this is why they say if you have two Poles, then you will

have at least three opinions. Each has so many of his own.

6

Chapter One

While Zbyszek was out at his car, I’d put seven złoty in the jukebox—this

bought ten songs. I chose Leonard Cohen’s “Dance Me to the End of Love,”

a Polish sea shanty, Led Zeppelin’s “Rock ‘n’ Roll,” Cohen’s “Everybody

Knows,” and some Supertramp, of course.

When I sat back down at the bar, the old man asked me, “Do you like

Litzmannstadt?”

7

When I applied for the Fulbright Lectureship during the Fall of 2006 I was

required to answer a question about which university I preferred. Specifically,

I could rank up to three. Since I had a previously existing relationship with

the American Studies and Mass Media program at Łódź, having attended

conferences there in 2001 and 2006 and having stayed in e-mail contact with

the leaders of the program, including it in my choices should not have been a

difficult decision. But it was.

Before the closing party of the 2006 conference, I had dinner with the

chair of American Studies at Warsaw University. He’d made it clear to me

that I should consider applying there, and he described what sounded like

a dynamic program, with productive colleagues and excellent students. His

description of the apartment I could use as just a tram ride, then a bus ride,

and finally a short walk from the program office was a little unnerving, but

at the time the excitement of Warsaw had the grimness of Łódź beaten hands

down in my mind.

But I put neither Łódź nor Warsaw as my first choice of destinations.

Instead, even though I knew no one there, I listed Jagellonian University in

Kraków as my first preference, for what seemed like several good reasons.

First, Jagellonian is the second oldest university in Europe, with a great repu-

tation in Poland and elsewhere. Also, and most importantly, it’s located in

Kraków, my favorite city in Poland. I ranked Warsaw second and Łódź third.

I felt a little guilty about this ranking, given that the University of Łódź had

provided the reason for two of my visits to Poland, but I really love Kraków

and Warsaw.

When I received notification that I was assigned to Łódź for a year I was

only a little disappointed because, deep down, I had known it was coming.

My mother thought it made good sense to return to Łódź because from my

Chapter Two

Choosing Łódz´,

Heading for Wrocław

8

Chapter Two

description she said it sounded a lot like Detroit, where I’d done my B.A. and

Ph.D. I knew that was true, and that I really didn’t belong at the Harvard of

Poland, but still . . .

Before formally accepting my assignment, I decided to do a little further re-

search on the American Studies program at Łódź. Their website proved quite

handy for this because it lists the names and American university affiliations

of the past half-dozen or so Fulbrighters who taught there. I “cold-emailed” a

few of them, and was scared to death by what some of them had to say.

The first former Fulbrighter to return my e-mail was far from satisfied with

his time in Łódź. He informed me that the classes are too large (over 80 stu-

dents in each); the students talk or do pretty much anything else they feel like

throughout lectures; they cheat brazenly, and justify it because they take too

many classes. In fact, he said, cheating is ingrained in the academic culture,

and there is an adversarial relationship between students and professors. He

complained that the Polish university bureaucracy is a tremendous burden,

and giving out grades will take away days of your life. He also claimed that

Poles are thieves, racists, and prone to violence—any polite outward appear-

ances to the contrary. Anyone who initiates contact with you is not to be

trusted because he is doing so just to get something from the rich American.

Naturally these comments substantially dampened my enthusiasm for spend-

ing a year in Łódź.

He also suggested that I read a series of articles that were published in the

Chronicle of Higher Education

, written by a Fulbrighter who’d spent a year

teaching in the American Studies program at Łódź. These thoughtful and

well-written pieces confirmed much of what the first former Fulbrighter had

said about the academic culture and class sizes. On the plus side, he didn’t

mention thievery and violence, and indicated that his wife and children

seemed to get along well in Poland. In our e-mail exchanges he suggested

that I sign up for the year—he certainly didn’t want his comments to stop me

from having what could be a very different experience—and if I didn’t like

it just to leave after a semester. That seemed to me like a shifty thing to do,

but he assured me that such selfish behavior was very much in keeping with

the Polish way.

These communications left me devastated. Something I thought I’d wanted

suddenly seemed like the worst idea in the world. Luckily, two more former

Łódź Fulbrighters painted a slightly better picture. An historian informed me

that, in his opinion, too many Fulbrighters view the award as an “academic

vacation.” He said he viewed it as an opportunity to work, which he said he

most assuredly had done while he taught at Łódź. He said curtailing poor

classroom behavior, which he didn’t believe was much more rampant in Łódź

than at most U.S. universities, was as simple as briefly stopping class and

Choosing Łódz´, Heading for Wrocław

9

reminding the offenders that attending class was a voluntary activity. I took

his point. I hate these classroom confrontations, but in my experiences they

are almost always successful.

Finally I talked with a fairly prominent American scholar, who also hap-

pens to be the editor of a political science journal to which some colleagues

and I had recently submitted a paper. When she returned my phone call,

she thought I’d called to discuss the submission, and seemed pretty relieved

when I said I’d called to talk about Łódź. She told me that she’d loved it. She

found the students intelligent and engaged, enjoyed the apartment she’d been

provided, and was pleased with the social interactions she’d had with her col-

leagues in the semester she’d spent there.

Well, that settled it for me: I’d spend only a semester instead of a year, but

I’d ask officially for the reduction in time, and not just leave my hosts hang-

ing. It was readily granted.

With profound ambivalence I departed for Poland. In retrospect, it’s a little

embarrassing how much stock I put in other people’s opinions of Poland. But

by committing myself for only one semester I believed I’d done something

smart. I’d reduced the probability of the worst possible outcome: being stuck

for a whole year in a place and situation I hated. Of course I also reduced the

probability of the best possible outcome: spending a year in a place I loved.

Such is the nature of compromise.

Having been to Poland several times, I know my preferred flight: KLM from

Detroit to Amsterdam, then Amsterdam to Warsaw. As a Fulbrighter this op-

tion was not available to me.

Fulbrighters are subject to a law called the Fly America Act. It means we

must use U.S. carriers to and from our host countries. The law was written

in 1974, and it might need a little updating. It is perfectly within the law for

me to pay an American airline to put me on a Lot Polish Airlines flight, but

I may not pay the Polish airline directly. So that’s what I did: I paid $1,300

to United to put me on their partner’s plane when I could have paid $800 to

fly KLM.

My flights over were easy ones: Detroit to Chicago, then Chicago to War-

saw. The hours on the planes were even relatively pleasant, except that during

the Detroit to Chicago run I sat next to a toddler who cried all the way. I tried

to sympathize with the little girl, imagining how baffling and unpleasant a

flight must be for a young child. I also knew that I was about to experience

five months of new and sometimes unpleasant experiences, so not letting the

first small irritation get to me seemed like a good idea.

Surprisingly, the Chicago to Warsaw flight even took off on time. It was

a very full flight, and we were jammed in tight. I had requested an aisle seat,

10

Chapter Two

but even that was of little benefit. I pitied the poor folks in the center and

middle seats, including the Polish woman seated to my right. She was small

in stature, so that helped. She was also very kind to the big American seated

next to her. For example, she told the flight attendant before I could that I did

not speak Polish when the attendant asked me what kind of wine I wanted

with my dinner. But how had she known?

The most interesting experience on the flight probably shouldn’t have hap-

pened, and wouldn’t have happened if I’d have minded my own business.

Two young Polish women were seated in front of me (I guessed they were

returning home after summer jobs in the States), and between the gap in the

seats I could see what the girl to my right was doing with her cell phone. She

was clearing out her text messages, which appeared to be of two varieties.

One set was from someone named James, while the other group came from

“Mazurkas,” clearly a screen name. James wrote his messages in English,

and they were all about how he’s still in love with her, how he’s “sorry for

everything,” wishes she’d forgive him, and just wants to see her just one more

time. She glanced at each, and then coolly deleted them one after another. The

messages from “Mazurkas” were in Polish, and she appeared to save them

all. It seemed the summer fling was being deleted in favor of the boyfriend

back in Poland. I felt sorry for James, for what he thought he’d lost, and for

“Mazurkas,” for what it appeared he was getting back.

The other interesting feature of the flight didn’t require any surreptitious

peering. Everyone on the airplane, except maybe those sitting in first class,

could hear the drinking Poles seated a few rows in front of me. The airline

brought the trouble on themselves when the flight attendants rolled the little

cart of duty-free items down the aisle. What looked to be a father and son pur-

chased a big bottle of vodka after dinner and decided to finish it on the flight.

As the other passengers slowly drifted off to sleep, and the lights over the

other seats went out one by one, the light over the vodka drinkers’ seat stayed

on. Of course their conversation became louder as they drank more, and the

flight attendants came around once in a while to ask them to be quiet. There

had been complaints, they said. The drinkers were polite and full of smiles

when being chastised, but they went right back to their bottle and their loud

conversation when the flight attendants left. I fell asleep before they did, but

when the cabin lights went on for breakfast, I noticed the bottle was empty.

The drinkers woke up and ate their breakfast, apparently none the worse for

wear. I remembered some advice from the first guidebook to Poland I’d ever

read: never, under any circumstances, try to out drink a Pole!

September 18, 2007 was my first day in Poland as a Fulbrighter. I arrived

in Warsaw mid-morning and took a taxi to my hotel. I was pleased with my-

self for being savvy enough to reject the offers of the corrupt cabbies who

Choosing Łódz´, Heading for Wrocław

11

snare unsuspecting tourist into paying five times the normal rate for a ride

downtown. Of course, I’d become savvy only through experience, but more

on that later.

Normally I stay at the MDM Hotel in Warsaw, which is located on Plac

Konstytucji and is surrounded by some of the best social realist architecture

in Poland. The housing “estate” was one of the first big new economic de-

velopments built by the Polish communist government after the war, and it

opened in 1952. Of course, every inch of the ground floors of the communist

era buildings is now filled with commercial capitalism at its neon finest, but it

makes an interesting mix. The staid stone and imposing facades of the 1950s

buildings, replete with much larger than life reliefs of workers, teachers and

peasants, mix surprisingly well with the bright lights of KFC and Samsung.

Before leaving for Poland this time, though, a great thing had happened,

which caused me to switch hotels. Most of the friends I’d harangued over the

years with arguments about why they just had to visit Poland, and do so soon,

were actually planning to come this time, especially those with any Polish

roots at all. So I decided to stay in a different hotel in a different section of the

city as a sort of scouting mission. It seemed to me that the MDM had gotten

a little big for its britches lately, often asking just a little less for a night than

the posh Marriott hotel just a few blocks north.

The cab ride felt a suspiciously long, but I couldn’t be sure because I

wasn’t exactly clear about where the hotel I’d chosen, the Ibis Stare Miasto

(Old Town), was located. I knew it was near the Old Town, but I wasn’t sure

just how close. The route we took felt a little circuitous, but it cost only 30

złoty (the ride to the MDM usually costs about 25), so I decided I probably

hadn’t been ripped off. And, in retrospect, I suppose the suspicion that I might

be being ripped off was probably a product of the high level of doubt about

Poles that I’d acquired from the paranoid writings and conversations I’d had

with former Fulbrighters about Łódź. I decided it would be crucial to over-

come that if I were to enjoy my time in Poland.

As it turns out, the Ibis Stare Miasto is actually closer to Warsaw’s New

Town, but it was an easy walk to both. I had a night to myself, before a day

of meetings and receptions at the U.S. Embassy. I checked into my room, laid

down on the bed and went to sleep. I know this is the worst thing to do for

jet lag, but I did it anyway. I woke up several hours later, and knew I would

have a hard time getting to sleep that night. I decided to walk through the

New and Old Towns, find some dinner, and visit a bar in the basement of

the Adam Mićkiewicz museum that I like. I figured a few beers would help

chase away the jet lag.

I ate at a restaurant called “Boruta,” which is Polish slang for the devil (and

which was the surname of one of our parish priests when I was growing up!).

12

Chapter Two

The middle-aged woman who usually works behind the bar in the basement

of the museum was there when I came in, and she corrected my Polish pro-

nunciation, just as she’d done on a few previous occasions. Then she played

comedian. I asked for a “duże” (“large”) beer. First she held up a very small

glass and I said no. Then she held up a half-liter glass, and I said no again.

Then she held up a liter glass, and I said yes. But then she pointed at the entire

keg and laughed, and I said, “nie dzię kuje!” (“no thanks!”).

Back in my hotel room after dinner and drinks I wrote the following in my

journal: “Well, even if nothing else good happens, at least I had a good meal

in the New Town area of Warsaw: delicious bowl of żurek and green-colored

pierogi with cabbage and mushrooms. Best pierogi ever. They played odd,

moody, echo-filled Polish rock, including a shuffling sixties-rock version of

‘Głęboka Studzienka’ that had great vocal harmonies.”

A few things came to mind after reading that entry written nearly at the

time the events happened. The pierogi and soup were, in fact, great. The ver-

sion of Głęboka Studzienka’, which is usually performed as a waltz by polka

bands in the United States, was indeed terrific. More importantly, the nega-

tive tone of my comments was pretty shocking to me in retrospect. I guess I

really feared the possibility of an unrelentingly negative semester in Poland

and had decided to accept whatever few good things happened as surprising

gifts. I knew part of the pessimism came from some of the bad things I’d been

told about Łódź, but I knew there was a deeper source of it as well, which

made it a little less embarrassing.

In 1984, when I was 15 years old, I’d volunteered to work on my first presi-

dential campaign—for Walter Mondale. Well, we all know what a failure that

campaign turned out to be: a 49 state loss! However, I remember reading in

one of the news magazines how Mondale had steeled himself for defeat. They

said he imagined the worst possible outcome, and this made anything short of

pure tragedy feel more like success. I’ve thought about a lot of other things

in my life that way too. It gives a sense of control—a sense that I can handle

anything but the absolute worst, which, mercifully, life rarely provides. So

Walter Mondale’s realism influenced my approach to Poland as well.

The first day of the orientation was interesting and fun. It took place at the

U.S. Embassy, located on Ujazdowskie Street. I had brief chats with most of

the other Fulbrighters and found out they were in Poland for myriad reasons:

some filmmakers were going to Łódź; some graduate students were staying

in Warsaw, while others were spreading out around the country. One was

writing her dissertation about oscypek—smoked sheep’s cheese from the

Tatra Mountain Poles, called Górale—and one of my favorite Polish foods.

A few were recently-minted B.A.s there to be teaching assistants in English

Choosing Łódz´, Heading for Wrocław

13

programs, while a few were, like me, professors there just to teach. The ori-

entation consisted mostly of a series of “do’s and don’t’s” related to different

aspects of Polish life as seen by the American Embassy.

Health

: drink the water, but at the very least let the taps run for a while

before filling your glass, and consider boiling it. Bottled water is cheap and

good, so it might be a good idea to buy that. Food from street vendors is

dangerous (e-coli), but most restaurants and supermarkets can be trusted. I

thought of Anthony Bourdain’s comment that you’re more likely to be poi-

soned by the hotel breakfast buffet than the street food, but I let it pass.

We were given health insurance cards and telephone numbers to call if we

needed assistance. We were told Polish dentistry is quite good and inexpen-

sive. Someone asked why he’d seen so many people with terrible teeth, and

another Fulbrighter commented, with some contempt, that even if it’s cheap

not everybody can afford it. I offered that even if it’s cheap some people are

still afraid of the dentist. That got a little laugh.

Politics

: There’s an election in October. Stay out of it. All current Polish

political parties have roots in Solidarity or in the old Communist Party. The

governing right-leaning party, Law and Justice, called early elections to so-

lidify their power. Their social democratic opposition, Left and Democratic,

has image problems because of all the former communists in their midst.

Civic Platform is right of center and very neo-liberal in its economic leanings.

There are others, such as the nationalist and sometimes anti-Semitic League

of Polish families, but these three are expected to be the top vote getters.

Poles will ask us about why the U.S. requires them to get visas in order to

visit. It is because of the high rejection rate: about 26 percent of applicants

are turned down. Until the rejection rate comes down, an expedited process

cannot be implemented, even if Poland was part of the “coalition of the will-

ing” in Iraq and might have expected some favorable treatment in return. No

one from the Embassy actually said that last part.

Safety

: Crime rates in Poland and the U.S. are about the same. If you get

drunk in a bar and get a chair broken over your head, the Embassy can only

do so much to help you out. Stay out of the bars.

The security chief admitted he’d only been on the job for a few months.

It was a mistake for him to admit that. Some of the Fulbrighters have been

coming to Poland for extended stays for more than 20 years. His claim about

the crime rates elicited howls of disapproval and clarification. Property

crime might be as high, but violent crime is much lower, they argued, and

he agreed.

After the orientation, a few of us went to a bar located in the former Pewex

store complex that one of the more Polish-seasoned Fulbrighters knew about.

During the course of our conversations, I admitted that I’d put together a

14

Chapter Two

fairly poor paper on Canadian women’s attitudes toward the U.S. just so I

could attend a gender studies conference in Poland in 2006. While my com-

panion was a serious feminist scholar, my intrusion into her area of expertise

didn’t offend her all that much, and as a future professor she liked seeing how

we could use the resources at our disposal to travel where we wanted. We

made it an early night because we had to get on the bus early the next morning

for the long ride to Wrocław.

The next day I rolled out of bed at 5:45 to catch a cab to the Etap Hotel

where we were to meet the bus for the trip to the southwestern Polish city

of Wrocław (formerly the German city of Breslau), where the major orienta-

tion was to take place. We departed at 7:00, and it took until 1:30 to get to

Wrocław, with only one stop. Polish roads and Polish traffic!

On the way to Wrocław Andrzej Dakowski, the director of the Polish-

American Fulbright Commission, showed us a movie: Andrzej Wajda’s

“Man of Marble.” It is a fascinating movie about a young film-maker played

by the beautiful Krystyna Janda, who is trying to make her student film in

the 1970s about a bricklayer who once was lauded by the communist govern-

ment, but eventually was removed from history. After his downfall they put

his statue in storage, thus the title. Showing the film was a smart move on

Dakowski’s part: it made the trip go more quickly and it put some of us in a

more sympathetic frame of mind.

At our one stop, I talked with two of the Fulbrighters, each with more than

20 years of experience with Poland. They discussed the fact they were both

in Poland when Chernobyl happened and how difficult it had been to get any

good information from the government about what they should do, and then

they’d learned that the government was recommending against taking the

form of treatment that they were secretly taking themselves, and administer-

ing to their families. How much better things are now, I thought.

We arrived in Wrocław and discovered pretty quickly that we were staying

in dorms. They were pretty spartan accommodations: bedroom, half-kitchen

(sink, no stove), and toilet with shower. I feared this might be what I was go-

ing to get in Łódź, but decided it would be adequate for 15 weeks.

During the first day of meetings in Wrocław, we heard a lecture by the

Rektor of University of Wrocław on the current condition of Polish universi-

ties. In Poland the Rektor is elected by the faculty. I could only imagine how

destructive a fight that could produce among our faculty. He told us there are

just too many students and not enough faculty and physical space. Where

have I heard that before, I thought. Students who pass the entry exam pay

no fees, while students who do not may attend the university if they pay. I’d

never before heard of doing things that way.

Choosing Łódz´, Heading for Wrocław

15

Then the Rektor mentioned the articles from the Chronicle of Higher Edu-

cation

that had been very critical of the students and of the American Studies

program at the University of Łódź. He said he was happy the columns had

been written, and that they had served as a wake-up call for Łódź and should

serve as a wake-up call for the rest of Polish higher education. It was disheart-

ening to hear confirmation of the criticism, but good to hear that Łódź might

have changed some of its ways because of it.

After the discussions, a few of us walked to a very nice hotel bar for a drink

before dinner. I brought up the critical columns, and Dakowski said the worst

of what I’d heard about Łódź was untrue. He said I would have to see for

myself. He seemed a little surprised that I had contacted former Fulbrighters

at the department in Łódź, and he said that a particularly disgruntled former

Fulbrighter was actually unhappy because he’d racked up a $10,000 phone

bill that he hadn’t wanted to pay. That was news to me. I began to realize that

was how my five months in Poland was going to be: a slow revelation.

16

Kresowa had caught my imagination, and I so liked the bartender Zbyszek

and the odd cast of characters that I decided to return for another visit a few

days after my first.

When Zbyszek had told me during my first visit that he wanted to write and

record songs better than Bob Dylan’s I’d told him that somebody already had:

Phil Ochs. There was something about Kresowa that seemed to encourage the

passionate expression of opinions, and I clearly wasn’t immune to it. I’m not

even sure I believe the claim, but I would have been willing to defend it to

the end at Kresowa. Zbyszek had said he’d never even heard of Phil Ochs,

and I’d promised to return with a disc.

So when I returned to Kresowa, I brought with me a compilation of Phil’s

music I’d burned from my collection. I own nearly every recording Ochs ever

produced. I walked in around 8:00, and Zbyszek was behind the bar and he

greeted me with a sort of “touchdown” hello: both hands up, but palms out.

A little odd, I thought, but I greeted him with enthusiasm too. The place was

packed, warm and bright, which was quite a contrast from my first visit. I sat

down at the bar, and after a few minutes he poured me a beer and I gave him

the disc.

At first he looked baffled by the spelling of the name, “Phil Ochs,” but

then after a few seconds he understood it and said it like this: “Feel Oaks.”

He wanted me to tell him about Phil, so I did, sparing no happy or grim detail.

I told him all about how Ochs had been the king of the 1960s politically-

oriented folk underground in Greenwich Village and that he’d killed himself

in 1976, with a few highlights in between: the 1968 Chicago Democratic

Convention, after which Ochs had had his tombstone carved; his 1973 con-

cert for Salvador Allende—a concert that Dylan saved from ruin just by

agreeing to perform at it. I told him how Dylan had once admitted that neither

Chapter Three

Return to Kresowa

17

Chapter Three

he nor anybody else could match Ochs’s topical song output, and also about

the famous incident where Phil criticized Dylan’s music while they were rid-

ing in a taxicab and Dylan threw him out of the car and said, “you’re not a

folksinger, you’re a journalist.” I told him about Ochs’s descent into alcohol-

ism and madness. Zbyszek listened—really listened—to it all, between his

duties pouring drinks for the rowdy crowd.

“Wow,” he said after each twist and turn of the Ochs story, which in some

ways is the American story of the 1960s and 70s.

“It was a real life,” he said.

“Yes, it was,” I replied.

“I am looking forward to hearing this,” he said and put the disc in a duffle

bag he kept behind the bar.

Then I told him that I had really enjoyed listening to his music, and that

I’d sent some songs to my friends in the U.S. and they had all reacted favor-

ably too. He made two fists, pounded one lightly on the bar and said, “yes!” I

quoted some of his lyrics that I liked, and pointed out which songs my friends

in the U.S. had liked the most. He seemed very pleased, which was cool be-

cause I wasn’t sure he’d have wanted me to disseminate his recording. Then

he disappeared through the kitchen behind the bar for about twenty minutes

and his girlfriend Ania took over. I drank two beers while he was gone.

When he returned he gave me a cigar. He said it cost one złoty, 30 groszy

— about 50 U.S. cents, but he wasn’t asking me to pay for it. It tasted better

than it should have, but I’m pretty sure I was smoking shredded communist-

era newspapers.

Then a small object hit me on the shoulder. It bounced off me and landed

on the bar and I picked it up: it was a broken cigarette lighter decorated with

a cartoon of a very erect penis wearing a condom. The woman who threw it

looked like quite a wreck, with greasy blonde hair and several broken teeth.

Her tight blue top revealed too much of her sagging breasts. I put two and two

together and told her “nie dzię kuje” (“no thank you”), and her smile disap-

peared as she angrily retrieved the lighter.

“Never mind her,” said Zbyszek, “only trouble.”

Then one of the most beautiful women I’d ever seen in Łodź walked into

the bar and sat down next to a strong-looking bald guy who looked like he

wanted to kick someone’s ass—anyone would do. She was young, maybe

twenty five, and she had long brown hair and big brown eyes. Her eyes had a

twinkle that I instantly recognized as both playfulness and trouble. Her thick

sweater couldn’t completely conceal the fact that she had enormous breasts.

She spoke flirtatiously with the bald man and he bought her a half-litre of

Warka and a shot of vodka. I thought this girl likes to drink, as she threw back

the shot and made pretty short work of the beer.

Return to Kresowa

18

After a few minutes the big man walked over and sat down next to me.

“I hear you speak English,” he said.

I told him I did.

He told me he worked in Warsaw in public relations for Media Markt, an

electronics store. He said he really wanted to be a journalist. Even though he

was big and brutal looking and he gestured pretty wildly when he talked, he

also seemed really sincere, and almost kind. He apologized frequently for his

English, but I assured him I understood everything he was saying.

He told me he commuted two hours each way from Łodź to Warsaw every

day, but he did it so he could spend more time with his sons, who were six and

twelve years old. He said he very much loved his sons, but he very much did

not love his wife. They stay together for the children. He admitted to a very

strong attraction to the beautiful brown-haired woman, and I agreed with him

that she was well worth a try. I was pretty sure he’d take one before I did.

We chatted for a while and it became clear that this fellow had been in

trouble with the law for “anger management” issues. He said he gets in fights

at football and rugby matches, but he teaches his sons to be both thinkers

and fighters (“Platonic guardians?” I offered. He wisely let it pass). He said

he had served six months in the French Foreign Legion but chose not to sign

up for the standard five year commitment. I believed him. He got really mad

when some men he did not like started talking to the beautiful young woman.

He said, “We call them ‘lefties’ because they shake your hand with the right

hand, but steal from you with the left.” He demonstrated the move by shaking

my hand and pulling my hat out of my coat pocket.

I told him I understood. We drank a few beers that I bought, and then he

said, “Poles disgust me.” I asked him what he meant.

“Everyone now is anti-communist. No way it is possible,” he said.

“I’m not sure I understand,” I said.

“Now people remember they were anti-communist,” he said, “even party

members.”

“Aha,” I said, “People want to remember themselves as they wish they had

been.”

“Yes! Yes! That is it,” he said excitedly.

I wished we could have talked some more, but it was approaching 10:30,

and I didn’t want to miss the last tram. I said my goodbyes to Zbyszek and my

new friend. I left a five złoty tip as I was leaving, and my new friend picked

it up and gave it back to me as if I’d dropped it accidentally. I told him it

was a tip for good service, and he seemed to understand. Zbyszek seemed to

understand too, even though good tips are uncommon in Poland.

Then another prostitute threw an empty Marlboro box at us. The big man

yelled at her in Polish, but she just laughed.

19

Chapter Three

“She is nothing,” he said.

His name is Dariusz, but he goes by Darek. He followed me out of the bar

onto the street, and walked with me as far west as Piotrkowska. As he was

putting my Polish phone number into his cell-phone, a car ran the red light

on Narutowicza and smashed into another. He laughed and yelled, “Polish

drivers!”

He was really insistent that we should drink together again. I told him I

would like that very much. But we never did. In fact, no one I met in Poland

when he was drunk in a bar who said we should get together again ever

called, or came back to Kresowa. I was not offended by this at all. The great

Polish poet Czesław Miłosz explains it best:

Perhaps . . . Polish men dislike themselves so intensely, in their heart of hearts,

because they remember themselves in their drunken states?

If Miłosz is right, why would a Polish man want to phone up and drink again

with a stranger? Poland was beginning to make perfect sense to me, on its

own terms.

20

At the orientation in Wrocław our rooms were located in identical fifteen-

story cement dormitory towers built in the 1980s. They are named “kredka”

and “ołówek,” “chalk” and “pencil,” and, not surprisingly, they are not beau-

tiful buildings. But we each had our own little suite, with two bedrooms, a

small kitchen, and a bathroom. They appeared to be built for four inhabitants

during the school year. The rooms were spartan and utilitarian, but they soon

felt like home sweet home, especially after the Herculean efforts of our stu-

dent guides from the University of Wrocław achieved internet connections

for each of us.

The trams that run in the center of the major street next to the dorms pro-

duced a good deal of racket as they banged over some imperfection in the

track. Because it was still warm, the rooms felt much more comfortable with

the windows open, which, of course, didn’t make it any quieter. Dogs barked

nearly constantly too, and students living on the higher floors threw a few

loud parties. I decided these were the kinds of small annoyances, like the cry-

ing child on the flight over, that I couldn’t allow to get to me if my time in

Poland was to be successful, so I tried to ignore them.

The street on which the trams run was built over an airfield the Nazis

constructed with slave labor near the end of World War II. Breslau, as the

Germans knew Wrocław, was supposed to be a final holdout against the Red

Army’s approach from the east. Tens of thousands of slave laborers died

from exhaustion, Nazi bullets and Allied bombing during construction of the

airfield, and one of the only uses to which it was ever put was for the flight

out for the Nazi general who was supposed to lead the defense of the city. So,

in Wrocław, as in so many places in Poland, history often lives right under

your feet.

Chapter Four

(Dis)Orientation

(Dis)Orientation

21

In Wrocław we mostly attended lectures and language classes. But we did

have a day set aside for tourism, and in typical Polish fashion we got much

more than our money’s worth: the day was long and filled with detailed expla-

nations of every site we visited. Wrocław is located in Lower Silesia, Śląsk in

Polish. The area became part of the modern Polish state only after World War

II, when eight million Germans were moved out, and six million Poles, many

from what is now part of Ukraine, were moved in. Many of the Poles came

from the city of Lwów (in Ukrainian, Lviv), and they brought their cultural

treasures with them, including a panoramic painting of the Polish defeat of

the Russians at the Battle of Raclawica in the Kościuśko Uprising of 1794.

The Panorama is one of the most popular cultural tourist attractions for Poles,

behind only Częstochowa we were told. We did not visit the Panorama on our

day of tourism, however. That was saved for later.

First we visited a huge wooden Evangelical church in Świdnica. It is called

The Peace Church because it was built in honor of the peace of Westphalia of

1648, which had permitted Lutherans to build a small number of churches in

the Catholic portions of the Holy Roman Empire, although the church itself

is only about 300 years old. Not surprisingly, in a country where less than

one percent of the population is Protestant, there are not many members of

the congregation, and now the church is used mainly for special events and

as a tourist attraction.

The best part of the visit was learning from my new friend Tony, a profes-

sor of architecture, some of the details of how such a massive wooden struc-

ture could have been built three hundred years ago, and built very quickly

with the use of almost no nails. It seems some of the techniques are not that

different from those used by post and beam barn builders in the 19

th

century

in the U.S., who also used no metal in the framing of their buildings.

We were served a sack lunch on the bus on our way to our next destina-

tion: Włodarz. The night before our day of tourism we were warned by our

student guides to bring a jacket, because we would be spending some time in

a cool place. Rumors circulated among the Fulbrighters, and we concluded

we would be visiting either a shady place in higher elevation, or going down

into caves. Worrisome to me, given my mild-to-medium claustrophobia (I

can ride in elevators easily, but I don’t like small airplanes, and I hate caves),

the consensus was that we would be going underground. And the consensus

turned out to be correct.

The group had begun to bond sufficiently that gentle fun could be made

of my fear of caves and their impending presence in my life. Some of the

women sympathized with my condition and assured me it would be perfectly

acceptable if I chose to stay outside while everybody else went in. I told them

I appreciated their sympathy, but I wanted to test myself. What a fool I was.

22

Chapter Four

The caves at Włodarz were built by the Nazis in the Sudeten Mountains,

and it turns out that nobody is quite certain why they did it. Well, more ac-

curately, nobody is quite certain why the Nazis forced slave laborers to dig

these caves. Somewhere on Earth somebody might know the answer, because

the Red Army confiscated the contents of the cave and shipped them back to

the Soviet Union at the end of the war. Modern day visitors who do not know

anything about the caves are not told before they enter that nobody knows

what they were used for.

We were given hard hats at the creaking steel door that covers the entrance.

Once the door is closed, the only light comes from incandescent light bulbs

strung from the ceiling every twenty feet or so. The walls are rough and

damp, and you can hear the sound of dripping water coming from many dif-

ferent directions where secondary and tertiary pathways break off from the

central tunnel. It was quickly apparent that it would be very easy to get very

lost in this complex.

Our English-speaking tour guide began with a joke.

“Are any of you afraid of ghosts?” he asked us.

We murmured a bit, and a few of us said we weren’t.

“Good,” he said, “because my name is Casper.”

During the tour of the caves, we went from one unfinished or semi-fin-

ished room to another, while Casper asked us why we thought it might have

been built. The shape of the first of these rooms reminded me of the first

gas chamber at Auschwitz, and I feared the worst about why they were not

telling us what the caves were used for. I surmised they wanted to wait until

we were back outside to tell us we had visited an underground death camp.

Deep within the complex, there is a small monument to the thousands who

died building it, but there is no mention of its being used as a death factory,

so about halfway through our visit I rejected my theory about how the Nazis

had used the caves. I also quickly gave up caring very much.

As we moved more deeply within the facility, the passage narrowed and

the ceilings got lower. I was forced to duck at a number of junctures, as were

people much shorter than my six feet one. The tour had become monotonous

and annoying. Each new room with its accompanying question about its use

irritated me more than the previous one. Clearly my claustrophobia was mani-

festing itself as anger. I tried to keep my breathing deep and even; I didn’t

want to hyperventilate.

Then we reached a dock, with several aluminum rowboats moored to it.

Yes, a dock.

Part of the complex has flooded, and evidently the climax of the tour in-

volves cramming too many people into each boat and paddling down a very

narrow tunnel. I don’t know why I agreed to get into the boat. Smarter people

(Dis)Orientation

23

than I stayed at the dock saying, “No thanks. We’ll just wait for you here.”

How wise they were.

The first several hundred feet of the boat ride were the worst. One passen-

ger seated at the rear of the boat was given a small paddle to control direction.

This seemed unnecessary since the narrowness of the tunnel barely allowed

the boats room to move more than a few inches from side to side. Forward

progress was made by pulling on ropes which were hung next to the electric

lines that fed the bulbs. To prevent electrocution, we were warned not to pull

on the electric line, only the rope. At several points in the tunnel the clearance

was so low that nearly everyone had to lean as far back as they could, or put

their heads between their legs.

Then after a few hundred feet of the most miserably claustrophobic ex-

perience of my life, our little over-full boats popped out of the tunnel into a

flooded room with forty or fifty feet of clearance to the ceiling, and enough

surface space for our boats to float and not come within ten or twenty feet

of each other. To say I found this room a welcome respite is a serious un-

derstatement, but then I remembered we had to go out the same way we had

come in. As we recovered from the journey, Casper asked us what we thought

the big flooded room could possibly have been used for, but by this point I

don’t think any of us was very much interested.

“Nazi swimmin’ hole?” I muttered.

As we made our way back through the narrows, I was euphoric because I

knew that the cave visit was nearly over, save for the retracing of our steps

out. I was so relieved, I felt like singing. I possess a deep, if flat, baritone, and

it rang off the walls of our narrow tunnel as I sang out:

The legend lives on from the Chippewa on down

Of the big lake they called ‘Gitche Gumee’

The lake, it is said, never gives up her dead

When the skies of November turn gloomy

With a load of iron ore twenty-six thousand tons more

Than the Edmund Fitzgerald weighed empty.

That good ship and true was a bone to be chewed

When the gales of November came early.

The reaction of the other Fulbrighters was just what I’d expected: much

laughter and a little singing along. It was also generational. The more sea-

soned among us knew the song well. They were the ones who sang along, and

encouraged me to sing more verses.

“We should sing to where the boat sinks,” said one.

“We have to at least meet the old cook,” said another.

24

Chapter Four

I think the younger ones might have thought we were singing a sea shanty

from the 18

th

century, and later that night I thought about my choice of songs,

wishing I’d chosen the “Gilligan’s Island” theme instead. Even though it

predates the “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” it would have had more uni-

versal appeal. “Next time,” I thought, and laughed about the unlikelihood of

repeating the singular experience of forty Fulbrighters in a flooded cave.

We ate our second lunch at a massive German house in Morawa. We were

the guests of a very gracious 80 year-old German woman. She was born in

the house when the land it sits on was still part of Germany, but she fled as

the Red Army approached in 1945, and she was able to return only in 1989,

after the fall of communism. The communists had used the house for, among

other things, military purposes, and there’s a stone carving of a Polish eagle

in the back yard. Because the communists carved the eagle, it lacks the royal

crown, but when the system fell, someone painted the crown back on. A bit

of the red paint is still visible.

The house is now used for many purposes, primarily in service to the local

community. In order to regain limited possession of the house, the old Ger-

man had to negotiate a deal with the new Polish government. She’s allowed

to live there now—I don’t think she owns the place -- and she runs a kinder-

garten in it. When communism ended so did free kindergarten, so she and her

staff provide a vital service for the local community.

Our final destination was a railroad and Harley Davidson Motorcycle mu-

seum in Jaworzyna Śląska. The man who owns it is really passionate about

his bikes and trains, but his operation is severely underfunded. He owns doz-

ens of train engines and other rolling stock. The buildings he stores them in