YEAR TWO

Introduction to SLA

#6: The Significance of Learners' Errors

1. The theory of transfer - The paradigms of Charles Osgood

Osgood (1949) summarised two decades of research into the phenomenon of transfer in the three

'paradigms':

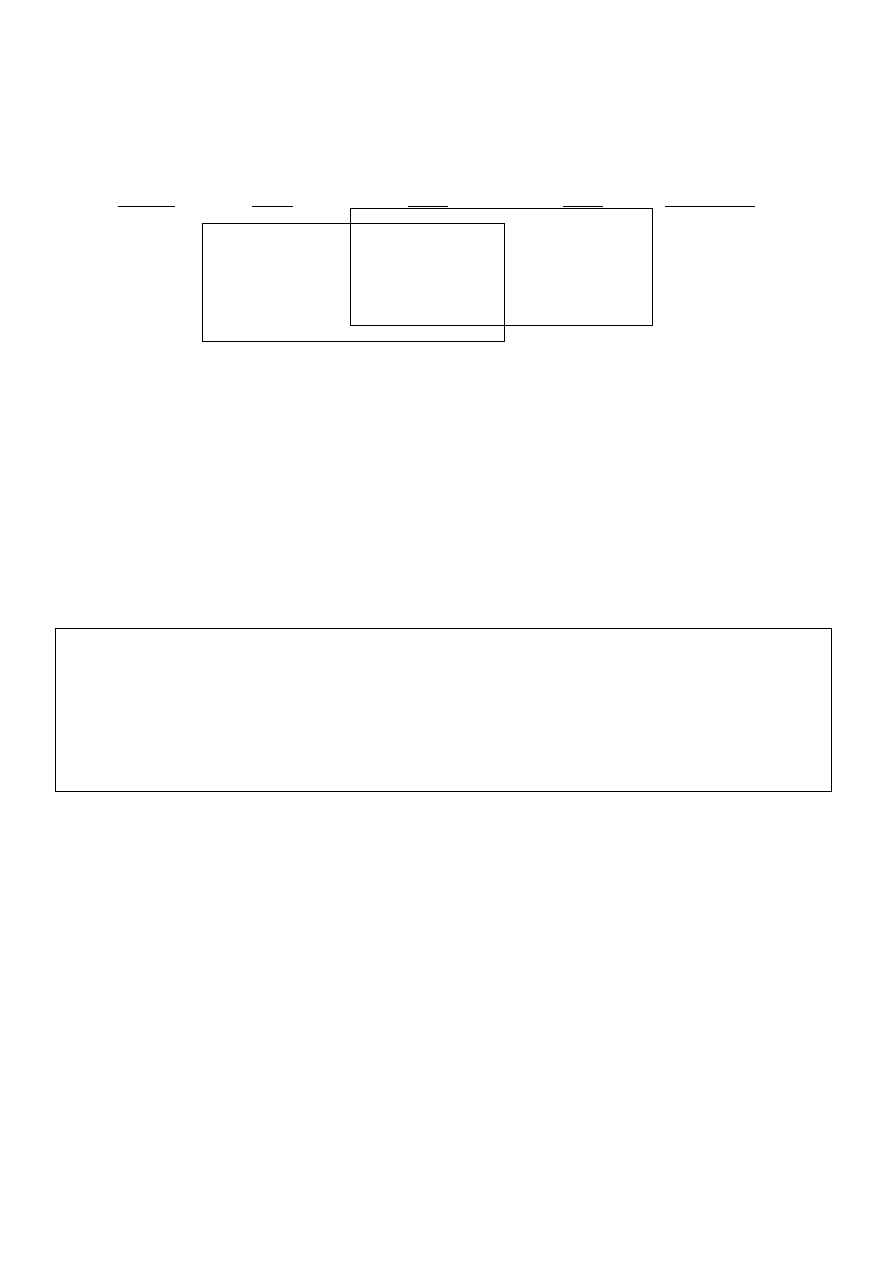

Paradigm

Task 1

Task 2

Task 3

Transfer-value

A

S1

-

R1

S2

-

R1

S1

-

R1

+T

B

S1

-

R1

S1

-

R2

S1

-

R1

-T

C

S1

-

R1

S2

-

R2

S1

-

R1

-T

RETROACTION

PROACTION

Osgood envisaged three learning tasks being set in sequence: notice that for each paradigm (A, B, C)

task 1 and task 3 are identical. When considering the effects on task 2 of having already done task 1, we

speak of Proaction, whereas Retroaction is concerned with the effect of having done task 2 on a

previously learned activity. In fact, there are only

two learning tasks, not three: task 3 is in reality a

performance task. CAH is concerned with proaction of course, seeing task 1 as the learning of L1 and

task 2 as the learning of L2. Retroaction is of potential interest to CAH in two ways: first, it could handle

effects of L2 upon performance in L1, known as backlash. Secondly, it is concerned with forgetting. It

would have to be invoked in any attempt to explain why L1 is not usually forgotten when a L2 is learned.

Here, we shall only be concerned with proaction.

Osgood assigns Transfer values to each paradigm: +T is positive transfer or 'facilitation' while -T is

negative transfer or 'interference'. The amount of +T or -T generated by each paradigm will depend, of

course, on how similar the stimuli (Ss) are with identity of the responses (Rs) or how similar Rs are with

identity of Ss.

The native language of learners exerts a strong influence on the acquisition of the target language

system.

While the native system will exercise both facilitating and interfering effects on the

production and comprehension of the new language, the interfering effects are likely to be

most salient. […] Errors are windows to a learner's internalized understanding of [L2], and

therefore they give teachers something observable to react to.

Student non-errors - the

facilitating effect - certainly do not need to be treated. Don't try to fix something that isn't

broken.

(Brown 2000: 66;

emphasis added)

2. Criticisms of the Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis and the emergence of Error Analysis

empirical: doubts concerning the ability of CAH to predict errors arose when researchers began to

examine language-learner language in depth

theoretical: there were a number of theoretical reservations concerning the feasibility of comparing

languages and the methodology of CAH

practical: there were doubts about whether CAH had anything relevant to offer to language teaching

Gradually, in the heyday of the audiolingual approach to foreign language teaching in the 1960s, which

advocated avoiding errors at all cost, researchers (e.g. Corder 1967) began to realise not only that

mistakes were a natural and inevitable outcome of learning, but that a

systematic study of learners'

errors could help us discover the processes underlying second-language acquisition. The new approach

paved the way for Error Analysis (EA for short).

The procedure for EA, spelled out by Corder (1974a), is as follows:

i. a corpus of language-learner language is selected (with regard for the size, the written vs.

spoken medium, the learners' age, L1 background and level of proficiency)

ii. the errors in the corpus are identified (e.g. performance slips vs. errors of competence)

iii. the errors are classified (e.g. according to a linguistic typology)

iv. the errors are explained (e.g. the psycholinguistic causes of errors are given)

v. the errors are evaluated (e.g. by assigning the seriousness of each error in order to take the

principal teaching decision, but only if a given EA is pedagogic; if it serves L2 acquisition

research, this stage is redundant)

From an EA perspective, the foreign-language learner is no longer perceived as a passive recipient of

input, but rather as playing an active role, processing input, generating and testing hypotheses.

According to EA, learners' errors are crucial because they indicate progress in developing the system of

L2.

3. Empirical research and the predictability of errors

The criticisms levelled against CAH in the late 1960s and early 1970s triggered off more interest in L2

learner errors. Some of the conclusions drawn from the findings of empirical research were so extreme

that they invalidated the predictions made earlier by contrastive studies. For example, Dulay & Burt

(1973; 1974) identified types of error according to their psycholinguistic origins:

85%: first-language developmental errors, i.e. those that do not reflect L1 structure but are found in

first-language acquisition data

12%: unique errors, i.e. those that do not reflect L1 structure and also are not found in first-

language acquisition data

3%: interference-like errors, i.e. those that reflect L1 structure and are not found in first-language

acquisition data

However, other research did not bear out Dulay & Burt's findings: in the studies relevant for EA and

published in the 1970s and early 1980s, the percentage of interference (i.e. negative transfer) errors

varies from 30 to 50%.

4. Error typology and error sources

An error can be defined in a number of ways. For example, George (1972) describes it as a form

unwanted by the teacher; a more recent definition, on the other hand, describes it as "a deviation from

the norms of the target language" (Ellis, 1994: 51). Early attempts at error typology, such as those

based on CAH and behaviourism, were rather simplified and distinguished roughly between negative

transfer (interference) and positive transfer (no error, despite the effect of the old habit on new

learning).

A distinction is often made between errors "of competence" and mistakes "of performance", whereby

the former are instances of genuine gaps in linguistic knowledge or noticeable and consistent

dissentions from the grammar of an adult native speaker, while the latter are mere random guesses or

slips, i.e. failures "to utilize a known system correctly" (Brown, 1994: 205). A third option has been

suggested by Edge (1989), who came up with the notion of attempts - efforts by learners who are

experimenting with the interlanguage system and predicting the rules and forms that they have not yet

studied formally.

Interlingual sources of errors refer to differences between L1 and L2 (Johnson, 2001: 66). In simpler

terms, these errors occur as a result of using some elements from one language while speaking another.

They can be further subdivied into:

overextension of analogy, in which the learner misues some item because it shares features with an

item in L1 (e.g. English *

process to mean ‘trial’, as in Polish proces);

transfer of structure, which arises when the learner utilises some L1 feature (phonological,

grammatical, lexical or pragmatic) rather than that of the target language. This is what is generally

understood by transfer;

Intralingual errors fall into the following categories (Johnson, 2001: 66):

overgeneralisation errors, which occur when the learner creates an incorrect structure on the basis

of other structures in the target language. It often involves one deviant structure in place of two L2

structures, e.g. *

He can sings coming from He sings and He can sing;

ignorance of rule restriction, which is closely related to the previous category and involves the

application of rules to contexts where they cannot apply, e.g. *

He made me to do it;

incomplete application of rules, which involves a failure to fully develop a structure. Thus, learners

of English as a L2 can use the wrong word order, e.g. in questions such as

You want to dance?, where

intonation questions (i.e. declarative statements with rising intonation) are used instead of

yes-no

questions;

false concepts hypothesised when the learner does not fully understand a distinction in L2 and may

come to believe that e.g. past time is marked in English with Aux

be and produce a sentence such as

*

One day I was danced with her.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

Year II SLA #5 The Contrastive Analysis Hypothesis

Year II SLA #3 Theories of First Language Acquisition

Year II SLA #19 Language Anxiety, Classroom Dynamics & Learner Beliefs

Year II SLA #11 Gender

Year II SLA #7 Error Analysis & Interlanguage

Dragonlance Tales II 01 The Reign of Istar # edited by Margaret Weis & Tracy Hickman

Year II SLA #17 Learning Strategies & Ambiguity Tolerance(1)

Year II SLA #2 First Language Acquisition

Year II SLA #18 Motivational Factors & Attributions

Tim Crane The significance of emergence

Year II SLA #16 Neurolinguistic Factors

The World War II Air War and the?fects of the P 51 Mustang

Analysis of Nazism, World War II, and the Holocaust

by the time of world war ii NZRMQ22WVNW73JEDUAEMIMBG2CLONPKSGVQGVJA

The Cycle of the Year as Breathing

Legg Calve Perthes disease The prognostic significance of the subchondral fracture and a two group c

Shakespeare The Comedy of Errors

The Extermination of Psychiatrie Patients in Latvia During World War II

Age of Empires II The Age of the Kings Single Player poradnik do gry

więcej podobnych podstron