Diffusion of innovations through social

networks of children

Laurien Kunst and Jan Kratzer

Abstract

Purpose – The paper aims to examine the role of social networks of children on the diffusion of an

innovation.

Design/methodology/approach – The impact of social networks on the adoptive behavior of children is

measured in the study and then compared to more traditional marketing strategies. Therefore an

experiment was conducted on three primary public schools in The Netherlands, with children aged eight

to 12.

Findings – The paper finds that a child’s centrality in his/her social network was the most important

determinant for adoptive behavior. The higher a child’s centrality in his/her social network, the stronger a

child’s adoptive behavior. In addition the findings show that traditional marketing strategies such as

mass media appeared to have no impact on adoptive behavior at all.

Research limitations/implications – Results indicate that instead of focusing on traditional marketing

strategies for children, more attention should be paid to a child’s social network position.

Originality/value – The number of studies in the field of social networks and the impact on adoptive

behavior of children, is very small. The results of this study show that additional research on this subject

would be highly valuable, from both academically and business point of view.

Keywords Consumer behaviour, Product innovation, Social networks, Children (age groups)

Paper type Research paper

T

here is a growing interest in the children’s consumer market in the academic literature

as well from a business point of view. McNeal (1992) identified children as

representing three markets in one: a primary market spending its own savings or

allowances; a secondary market of ‘‘influencers’’ on mainly parental spending; and a future

market of potential adult consumers. Children have their own likes, dislikes, curiosities and

needs that are not the same as their parents or teachers (Druin, 2002). Although this seems

very obvious, designers, marketers and product-developers sometimes forget that young

people are not ‘‘just short adults’’ but an entirely different user population with their own

culture, norms and complexities (Berman, 1977).

Recently a wide range of marketing research has been done reflecting children’s growing

sophistication as consumers, including their knowledge of products, brands, advertising,

shopping, pricing, decision-making strategies, and parental influence and negotiation

approaches (Procter and Richards, 2002; Roedder, 1999). Also, research showed that peers

are an important socializing influence, increasing with age as parental influence decreases

(Roedder, 1999; Ward, 1974). Even though there is a growing interest in the field of child

marketing, one important marketing practice has been neglected when it comes to children.

PAGE 36

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007, pp. 36-51, Q Emerald Group Publishing Limited, ISSN 1747-3616

DOI 10.1108/17473610710733776

Laurien Kunst is a Research

Assistant and Jan Kratzer is

an Assistant Professor, both

at the Faculty for

Management and

Organization, University of

Groningen, Groningen,

The Netherlands.

Extensive research has been done in the field of diffusion of new products and services

(innovations) and what factors influence the speed of the diffusion process (Rogers, 1983;

Bass, 1969). Although diffusion theory has sparked considerable research among

consumer behavior, marketing management, sociology, political science (Wejnert, 2002;

Mahajan et al., 1990), with regard to young children a surprisingly small amount of research

exists on this topic (Hansen and Hansen, 2005; Procter and Richards, 2002; Roedder, 1999).

Diffusion of innovations refers to the spread of innovations within a social system, where the

spread denotes flow or movement from source to an adopter, typically through

communication and influence (Rogers, 1995). Such communication and influence alter an

adopter’s probability of adopting an innovation, where the adopter may be any societal

entity, including individuals, groups, organizations, or national polities. More and more

literature is concerned with the development of normative guidelines for how an innovation

should be diffused in a specific social system (Mahajan et al., 1990). As little attention has

been paid to children as ‘‘a specific social system’’, this study aims to provide insights about

factors that influence the diffusion process of innovations among children.

Researchers identified several factors that seem to influence the diffusion of an innovation

among members of a social system. There are many studies that investigated the role of

social networks in the diffusion of innovations (Rogers, 1962; Coleman et al., 1966;

Granovetter, 1973; Burt, 1987). Additionally Czepiel (1976) and Sheth (1971) claim that an

active, functioning informal communications network is one of the most important factors that

determine the successful diffusion of an innovation. In line with this Rogers (1995) claims that

in order to diffuse innovations, they need to be communicated through certain channels over

time (Rogers, 1995). For this reason communication plays a central role in most diffusion

theories (Larsen and Ballal, 2005).

In accordance to this we identify two types of diffusion theories: cohesion theory and

threshold theory (Larsen and Ballal, 2005). The former relates an actor’s position in his/her

network to the speed of adoption of an innovation. These studies highlight that actors who

possess a more central position in their social network, are often found to adopt an

innovation in an early stage of time. The thresholds theory argues that an actor engages to

behavior based on the ratio of actors in the social system already engaged in the behavior

(Granovetter, 1978).

In addition, it is claimed that thresholds of individuals vary (and therefore their adoptive

behavior as well) since they are influenced by some factors, like the use of mass media

(external influence). Other studies suggest that the involvement of customers with the

innovation process could influence an individual’s threshold. Involving customers with the

innovation process not only creates a better product, providing customers with the

experience of participating in the design of a product but also wins their loyalty and

stimulates word-of-mouth (WOM) communication, thereby speeding up the diffusion

process (McKenna, 1995; Brown et al., 2005). Although detailed research is done about

different roles children could play in the design of new technologies (Druin, 2002), little

attention is paid to the relation between the involvement of children into the new product

development (NPD)-process and the diffusion of innovations.

Accordingly, in this article we examine factors that determine the diffusion of innovations

among children. First the role of social networks in the diffusion process is emphasized. This

is followed by exploring two factors that could impact the adoptive behavior of a child

through influencing their personal thresholds, namely the use of mass-media

communication and the involvement of children into the NPD process. Next, the methods

used for the empirical research are presented. This is followed by an analysis of the

gathered data and results are presented. Finally the theoretical and practical implications

are discussed and suggestions for further research are made.

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

PAGE 37

Social networks and the diffusion of an innovation

The diffusion of an innovation traditionally has been defined as the process by which that

innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a

social system (Rogers, 1983). As Rogers (1962) points out:

. . . the diffusion process consists of (1) a new idea, (2) individual A who knows about the

innovation, and (3) individual B who does not yet know about the innovation. The social

relationship between A and B have a great deal to say about the conditions under which A will tell

B about the innovation and the results of this telling.

Different studies indicate that an active, functioning informal communications network plays

an important role, if not the most important role, in the diffusion of an innovation (Czepiel,

1976; Sheth, 1971). Thus, communication is central in most theories about the diffusion of

innovations (Larsen and Ballal, 2005), since innovations need to be communicated between

actors within a social system in order for them to start the diffusion process. How do

structural characteristics of social networks influence the communication between actors

and thereby the diffusion of innovations?

Cohesion theory: the strength of ties

The initial network approach to diffusion research was to count the number of times an

individual was nominated as network partner. In turn this variable was correlated with

innovativeness. Innovativeness is measured by an individual’s time-of-adoption of the

innovation under study (Rogers, 1962; Coleman et al., 1966). These cohesion theories argue

that informal communication networks provide a better map than formal communication

networks for successful diffusion. The understanding of the network is built around the

number of times an actor is nominated by other actors through survey or interview. These

nominations determine the centrality of an actor in a social system. This specific kind of

centrality refers to the number of ties a node has and is defined as degree centrality

(Freeman, 1979). The more ties the higher the degree centrality, which cohesion theory

argues has a direct impact upon their innovativeness (Coleman et al., 1966). The diffusion

literature reports a clear correlation between physical proximity and the strength and speed

of WOM spread, and thereby the speed of the innovation diffusion process (Baptista, 2000;

Case, 1991). The (central) position of an actor was thus found to have a direct impact on the

adoptive behavior of that actor. Cohesion is seen as a strong ties theory. It is based around

the centrality and closeness of actors and links this to their importance concerning

innovation diffusion (Larsen and Ballal, 2005).

The focus on strong ties was later changed to a focus on both strong and weak ties. This

resulted from a study conducted by Granovetter (1973), named the strength of weak ties

(Granovetter, 1973; Liu and Duff, 1972). The strength of weak ties indicates that an

innovation diffuses to a larger group of individuals and traverses a greater social distance

when it is passed through weak ties rather than strong ones. In any kind of situation, an

individual operates in a particular communication environment consisting of a number of

friends and acquaintances with whom a topic is discussed most frequently. These friends

are usually highly similar with the individual and with each other, and most of the individual’s

friends are friends of each other, thus constituting an interlocking network (Rogers, 1976).

Liu and Duff (1972) showed that an innovation spread most easily within these interlocking

cliques (strong ties). The similarity of individuals stimulates and facilitates effective

communication inside such a network, but it acts like a barrier preventing new ideas from

entering the network. Central to previous theories is that behavior, opinion, and information

are more homogeneous within than between groups. Accordingly, to diffuse innovations

through a wider society both strong and weak ties are necessary.

Let us explain more about the so-called weak ties. People focus on activities inside their own

group, which creates holes in the information flow between groups, called the structural

holes (Burt, 1987). Actors whose networks span structural holes have early access to

diverse information, which provides them a competitive advantage in seeing good ideas and

early access to innovations. Actors who function as bridges between groups thus can be

identified as central actors as well, since they facilitate (communication) flow between

PAGE 38

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

groups. This kind of centrality does not refer to the number of ties (so, the actors are weak

ties), but refers to the extent to which an actor facilitates the flow of that-which-diffuses,

which is called ‘‘betweenness’’ centrality (Borgatti, 1995). Borgatti (1995) argues that

‘‘betweenness’’ centrality is one of the most important ways to assess an actor’s importance

in the diffusion process.

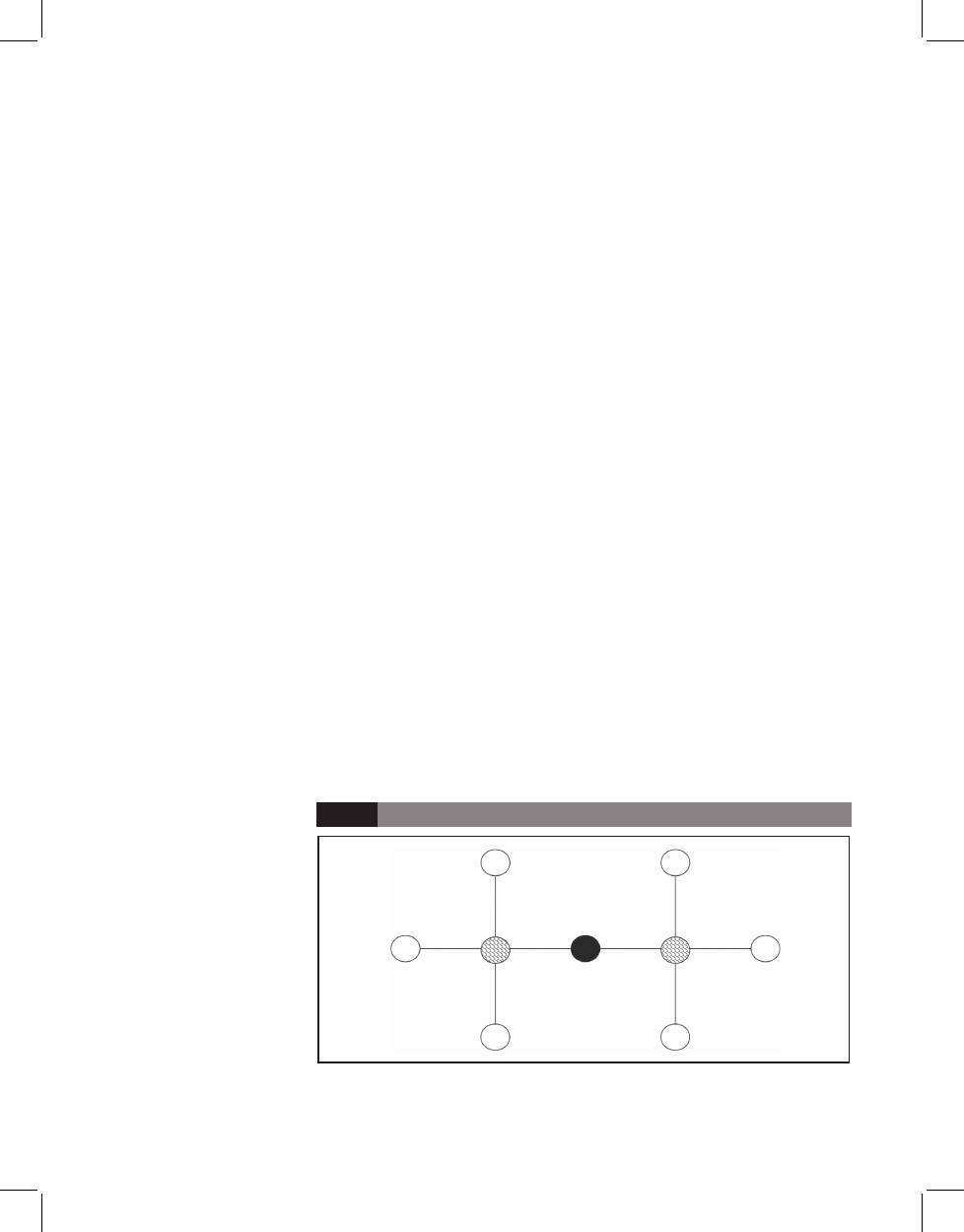

In Figure 1 the differences between the two centrality measures is visualized. The crammed

ovals present actors with a high degree centrality (the strong ties), the black oval presents an

actor with a high ‘‘betweenness’’ centrality (the weak ties).

To diffuse an innovation through a whole society both strong and weak ties are found to be

essential (Larsen and Ballal, 2005). To examine whether these arguments also count in the

case of ‘‘a child’s society’’, we hypothesize:

H1a.

The higher a child’s degree centrality in his/her social network, the stronger a child’s

adoptive behavior.

H1b.

The higher a child’s ‘‘betweenness’’ centrality in his/her social network, the stronger a

child’s adoptive behavior.

Thresholds theory

Theories concerning thresholds in the diffusion of an innovation claim that an individual

engages in a behavior based upon the proportion of individuals in the social system already

engaged in the behavior (Granovetter, 1978). Threshold models argue that individuals have

varying thresholds. Therefore individuals have varying times-of-adoption and thus thresholds

are seen as the cause for the S-shaped rate of adoption (Granovetter, 1978). There is a widely

accepted method of predicting the pattern of diffusion of an innovation, proposed by Rogers

(1983). When the cumulative adoption is plotted in terms of actual adoption per period of time

over the life of the product, the result is a normal distribution. By using the parameters of such a

distribution Rogers (1983) developed a system to classify adaptors of an innovation. The first

few people that adapt an innovation are considered the innovators (2.5 percent), followed by

the early adopters (13.5 percent). Then the majority is divided into early and late (34 percent

each) and the laggards make up the remaining 16 percent (Rogers, 1983).

Thresholds have been postulated as one explanation for the success or failure of collective

action and the diffusion of innovations (Valente, 1996). Threshold models can be used to

predict the diffusion of an innovation, since the adoption of an actor can be seen as a

function of the adoption behavior of the actor’s network (Valente, 1996). Considering this, it

seems very important to examine what exactly causes the varying thresholds among actors,

because the faster the first threshold is reached (the early adaptors), the faster other actors

Figure 1 Graphical presentation of degree and betweenness centrality

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

PAGE 39

start to adopt the innovation. We identify two factors that are assumed to influence the

thresholds of actors (and thus their adoptive behavior), namely external influence (Mahajan

et al., 1990) and the degree of involvement with new product development (McKenna, 1995;

Brown et al., 2005).

Thresholds: external influence

The rationale for the formation of adopter clusters is related to the role of WOM and imitation in

the diffusion of innovations (Garber et al., 2004). Following the diffusion paradigm that views the

communication process as the main driver of new product growth, one can identify two types of

communication effects: external and internal (Mahajan et al., 1990). The model assumes that

the adaptors of an innovation comprise two groups. One group is only influenced by the

mass-media communication (external influence) and the other group is only influenced by the

WOM communication (internal influence). Bass (1969) termed the first group innovators and

the second group imitators. Mahajan et al. (1990) provide an approach that develops adopter

categories using the same analytical logic as Rogers used and thereby show that the use of

mass media is related to a stronger adoptive behavior of an actor.

Other studies confirm that external influence provide actors with earlier awareness of an

innovation (Becker, 1970; Weimann, 1982) and freedom from system norms (Menzel, 1960)

thereby enabling them to adopt an innovation earlier. In addition Valente (1996) found that

early adoption is associated with high external influence. Thus, we hypothesize:

H2.

The higher the degree of external influence, the stronger a child’s adoptive

behavior.

Thresholds: customer integration

Next to the use of mass media (a rather traditional marketing strategy), a considerably new field

of research could impact the thresholds of actors as well. This research deals with the

involvement of customers with the development of new products and services. Empirical

research shows that there is high risk associated with developing new products (Brockhoff,

1998).

The accurate understanding of customers needs has been shown near essential to the

development of commercially successful new products (Von Hippel, 1986). A way to reduce

the market risk of innovations, and a way to overcome the difficulties with designing new

products for children, is to integrate the customer into the innovation process (Cooper, 1979;

Chesbrough, 2003; Druin, 1999). To better understand the customer needs, customers need

to be provided with so called toolkits for user innovation (Von Hippel and Katz, 2002). A

toolkit for user innovation is defined as a technology that allows users to design a novel

product by trial-and-order experimentation. Furthermore it delivers immediate feedback on

the potential outcome of their design ideas (Von Hippel, 2001). Empirical research

additionally shows that customers are frequently the first to develop and use prototype

versions of what later became commercially significant new products and processes

(Von Hippel, 1976; Van der Werf, 1990).

Although not frequently mentioned in the diffusion literature, we can assume that (early)

customer involvement into the NPD process influences the threshold of an actor, in the sense

that it reinforces an actor’s adoptive behavior. In addition McKenna (1995) claims that the

integration of customers into the innovation process wins their loyalty and thereby speeds up

the diffusion of an innovation. This argument is in line with some recent studies on

intermediating antecedents of WOM intentions and behaviors. Brown et al. (2005) show that

customer involvement exerts significant influences on positive WOM intentions and

behaviors. Integrating customers into the innovation process (thereby creating commitment

of the customer) therefore can foster positive WOM by these actors. This would especially

apply for children as consumers since involving children as users, testers, informants or

design partners make children feel empowered (Druin, 2002). To consolidate the argument

above, the following hypothesis will be tested:

PAGE 40

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

H3.

The higher the degree of involvement with the NPD process, the stronger a child’s

adoptive behavior.

Methods used

In order to test whether our expectations were correct, different data were collected. We

made the decision to collect the data through examining school classes, since they can be

used easily to analyze social relationships between children (Defares et al., 1971). We used

a pre-experimental research design (Baarda and De Goede, 2001). This is done in

combination with a self-administered questionnaire.

To measure the differences in the adoptive behavior of children, on each school an

innovation, called Kijkradio, was introduced. Kijkradio is an interactive online tool, which

enables children to make their own news program. Kijkradio is a product of a Dutch

foundation Cinekid (positioned in Amsterdam), which aims to teach children how to use

media in a funny and sustainable way. Not only does Cinekid organize the world’s largest film

festival for children, they also provide free online tools such as Kijkradio. To examine the

effect of different situations on the adoptive behavior of the children, the innovation was

introduced in a different way on each school.

At the first school children were intensive involved with the new product development

process of Kijkradio. The roles which children can play in the design of a new technology is

studied in detail (Druin, 2002). Druin (2002) distinguishes four main roles: the child as user,

tester, informant and design partner. The children at the first school played the role of both

user and tester. The involvement of these children is done by taking into account research

methods that are suitable for both the user-role and the tester-role (Druin, 2002).

At the second school Kijkradio was introduced with a simulated mass-media campaign.

Three types of media were used, television, paper advertisement (including promotional

posters), and promotion via the internet. First the children saw a promotional video about

Kijkradio in their classroom. Additionally promotional posters, folders, and newspapers were

spread around the school. Further as children started to work with Kijkradio every child saw a

promotional message on the start page of the internet.

Finally at the third school Kijkradio was introduced with no additional attention. Children got

the possibility to work with Kijkradio when they wanted it. About two weeks after the

introduction of Kijkradio the children filled in a questionnaire.

Subjects and sample

Kijkradio is aimed at children with the age of eight till 12, which are the children in the four

highest grades of the primary school. The experiment is conducted on three public primary

schools in The Netherlands. In The Netherlands most schools are public schools, they are

accessible for children with various cultures and beliefs, and therefore representative for the

average ‘‘Dutch child’’. These schools were selected in adjacent school districts, to exclude

possible regional influences. Within each school two classes (‘‘group five’’ and ‘‘group

seven’’) were randomly selected.

We decided to use a cluster sample, containing the children in group five and group seven.

These groups contain children of all ages (eight till 12), as a result of recidivists. Moreover a

whole group can be used easily to analyze social relationships between children (Defares

et al., 1971). The final cluster sample contained three public primary schools, which means

three classes group five and three classes group seven. The total sample contained 141

children.

To collect data about children’s social networks we used a sociometric method, called

Seracuse-Amsterdam-Groningen Sociometrische Schaal (SAGS). This method uses a

specific questionnaire, which is designed as a complete list of actors (children in a specific

class) and ratings are gathered from each actor about their ties to other actors. The ratings

are made by choosing one of the five possible categories for the strength of each tie. SAGS

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

PAGE 41

has the advantage of being a reliable and valid instrument to examine the networks of

children (Defares et al., 1971). The SAGS questionnaire was filled in by 135 children.

As pointed out before, two weeks after the first introduction of Kijkradio the children filled in a

questionnaire. This questionnaire focused on the extent to which children adopted the

innovation (by asking how often they had used Kijkradio) and whether they had told their

classmates/friends about Kijkradio. The second questionnaire was used as back-up

instrument, to measure the adoptive behavior, in case the system failed to count the times a

child signed in on the website. Eventually there were 129 children who filled in both the SAGS

questionnaire and the second questionnaire properly.

Analysis and measures

H1a and H1b contain specific measures of social networks. To provide insight about the way

concepts are operationalized and data were analyzed, it is necessary to explain more about

social network analysis. The data that were gathered through the SAGS questionnaire

resulted in a matrix containing valued and directed relations between the children of each

class. There are different ways of collecting data on social networks, which results in different

ways of representing and measuring social networks. A model that presents a social network

with an undirected dichotomous relation is called a graph. So, a graph is a tie that is either

present or absent between each pair of actors (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). The data

gathered through SAGS thus contains more complicated (valued and directed) relations

between children.

To find out which network measures could be calculated, we analyzed whether the collected

data could be presented in a matrix containing undirected relations, thus as a symmetric

matrix. This was done for each class, using UCINET VI (Borgatti et al., 2002). First each data

matrix was transposed. The transpose of a matrix is constructed by interchanging the rows

and columns of the original matrix (Wasserman and Faust, 1994). To measure the value of

reciprocity between each pair of classmates, the correlation between the original and the

transposed matrix was computed. (A Pearson’s correlation coefficient greater than zero

implies a positive correlation between the two matrices).

The Pearson correlation coefficient for each transposed matrix was on average higher

than 0.50, which implies a strong positive relation. This correlation was significant at a

0.01 significance level. To make sure that a symmetrized matrix would not influence the

values of the network measures, both in- and out-degrees were calculated. The

differences in the in- and out-degrees of each actor were very small. In combination with

the high correlations, this was enough evidence to symmetrize the matrices. The matrices

were symmetrized using the minimum symmetrizing method, because friendship can be

defined as a feeling that needs to be mutual. If it is not (completely) mutual the lowest

score will represent the value of friendship between two actors.

To compute specific network measures, such as ‘‘betweenness’’ centrality, data was

dichotomized. In the SAGS questionnaire children valued their friendship relations from one

to five, where one refers to no friendship at all and five refers to best friends. When a child

valued the friendship with three, this means the child is not really a friend, but is closer

related to the child than children who are valued with one or two. Therefore the data was

recoded as follows: the values one, two, and three were recoded into zero, which means

there is no friendship between the children. Values four and five were recoded into one,

which implies there is a (strong) friendship between the children. After the preparation of the

data, the network measures could be calculated.

Independent variables

Degree centrality

In this article degree centrality is defined as the number of ties a node has (Freeman, 1979).

The more ties, the higher degree centrality. The degree centrality of each child is calculated

using UCINET VI (Borgatti et al., 2002). The valued and undirected relationships between

the children of each class were taken as input for this calculation.

PAGE 42

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

‘‘Betweenness’’ centrality. ‘‘Betweenness’’ centrality refers to the probability that a

‘‘communication’’ from actor j to actor k takes a particular route. Hereby it is assumed that

lines have equal weight and communications will travel along the shortest routes, and

therefore it is assumed that such a communication follows one of the geodesics (Wasserman

and Faust, 1994). If Bjk is the proportion of all geodesics linking actor j and actor k which

pass through actor i, the betweenness of actor i is the sum of all Bjk where i, j and k are

distinct (Borgatti et al., 2002). This measure proposed by Freeman (1979) and is calculated

with UCINET VI (Borgatti et al., 2002).

Degree of external influence

The degree of external influence is measured as follows. As previously mentioned we

conducted a pre-experiment on three public primary schools, in which we introduced

Kijkradio on three different ways. On the second school Kijkradio was introduced with a

simulated media campaign. The degree of external influence on the second school (42 of

the 129 children in the sample) therefore is presumed ‘‘high’’. The remaining children (the

control group) are presumed to have a low degree of external influence. This variable is

included as dummy, with low degree of external influence

¼ 0 and high degree of external

influence

¼ 1.

Degree of involvement with the NPD process

The degree of involvement with the NPD process is measured the same way as the degree of

external influence. Only the children on the first school (48 of the 129 children in the sample)

were involved with the NPD process. As mentioned before, this is done by using children in

the role of user and in the role of tester. The degree of involvement of each child on the first

school therefore is presumed as high. The remaining children (the control group) are

presumed to have a low degree of involvement. This variable again is included as dummy,

with low degree of involvement

¼ 0 and high degree of involvement ¼ 1.

Dependent variable

Adoptive behavior

The adoptive behavior of a child is measured through the number of times a child has used

Kijkradio. The use of each child is recorded through the number of times a child has signed

in on the web site.

Control variables

There are many other factors that have been shown or may be shown to influence social

networks of actors and the adoptive behavior of an actor. While it is not possible to include all

other variables in this study, we chose to include two variables that have been suggested to

affect the social networks of actors and the adoptive behavior of actors.

Gender

Boys and girls develop in the same way and have the same fundamental needs. In contrast

to this the way they express and satisfy their needs and feelings is different (Del Vecchio,

2002). Therefore differences in the adoptive behavior of children are likely to occur. Kalmijn

(2003) in addition reports that gender influences social networks, since women are likely to

have more frequent contacts with friends than men do. This variable is included as dummy,

where male

¼ 1 and female ¼ 2.

Age

Children of different ages have diverse likes and dislikes, as a child grows older the

thoughts, expectations and feelings of a child change (Craig and Baucum, 2003). Many

studies on consumer socialization of children report the differences in adoptive behavior as

a child grows older (Roedder, 1999). Additionally research shows that social networks are

not stable over time, since friendships tend to change as a child grows older (Craig and

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

PAGE 43

Baucum, 2003). Stages in the life course will influence the social networks of actors (Kalmijn,

2003) (see Table I).

Results

H1a and H1b are tested by conducting a regression analyses for adoptive behavior. H2 and

H3 are also tested by conducting a regression analysis for adoptive behavior, but are

presented separately from the first two hypotheses since they are assumed to be related to

innovation diffusion in a quite different way. Before we present the results of these regression

analyses, let us first show the bivariate correlations for each of the variables (see Table II).

As the correlations coefficients indicate, there is a significant positive relationship between

the adoptive behavior of a child and the degree centrality (0.383), the betweenness

centrality (0.342) and the age of a child (0.271). Another result is that degree centrality

positively relates in a statistically significant manner to betweenness centrality (0.434) and to

age (0.425).

The degree of involvement with the NPD process relates in a significant positive way to

degree centrality (0.309). Since the network data was gathered before we conducted the

experiment (the involvement of the children with the NPD process), this positive correlation

does not indicate that higher involvement of children causes a higher degree centrality. This

positive correlation simply indicates that the children on the first school have a significant

higher degree centrality than the children on the remaining two schools. The negative

relation between degree of external influence and degree of involvement (2 0.535) is a logic

consequence of the pre-experimental design, in which a high degree of external influence

was only present on the second school and a high degree of involvement was only present

on the first school. Finally the analysis shows a negative correlation between age and gender

(2 0.186), which implies that the sample contains more boys when the children have a higher

age.

Table II Bivariate correlations for variables

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Variables

1.

Adoptive behavior

–

2.

Degree centrality

0.383**

–

3.

Betweenness centrality

0.342**

0.434**

–

4.

Degree of external influence

0.077

0.013

2

0.015

–

5.

Degree of involvement into NPD

2

0.066

0.309**

2

0.092

0.535**

–

Control variables

6.

Gender

2

0.136

2

0.045

2

0.090

0.126

0.001

–

7.

Age

0.271**

0.425**

0.142

2

0.190

0.157

0.186*

–

Notes: * Significance at 0.05; ** Significance at 0.01

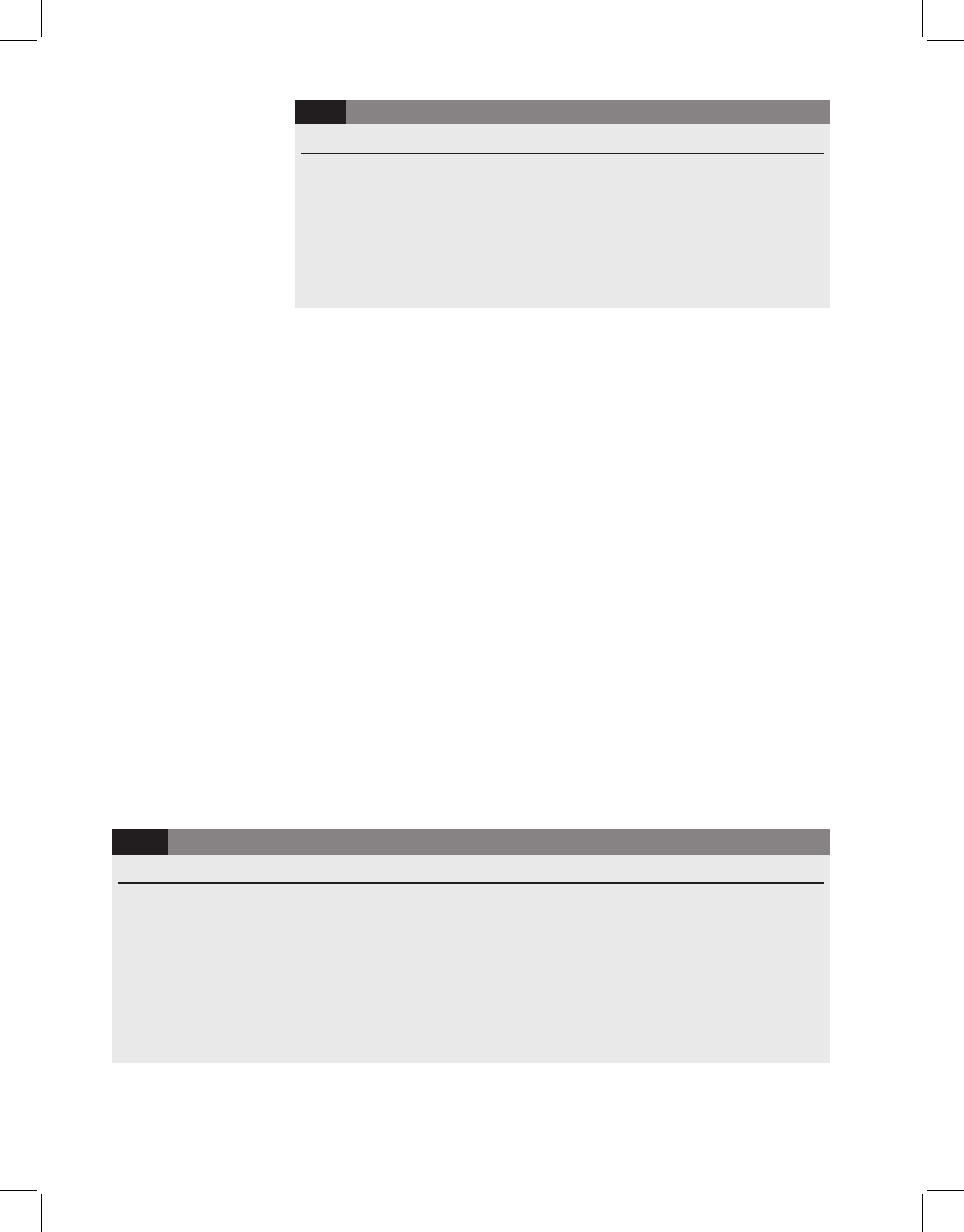

Table I Descriptive statistics

Minimum

Maximum

Mean

Std deviation

n

Variables

1.

Adoptive behavior

0

68

7.80

8.23

129

2.

Degree centrality

18

67

41.06

10.63

129

3.

Betweenness centrality

0

98.6

14.95

23.77

129

4.

Degree of external influence

0

1

0.67

0.47

129

5.

Degree of involvement into NPD

0

1

0.63

0.49

129

Control variables

6.

Gender

1

2

1.54

0.50

129

7.

Age

8

12

9.97

1.07

129

PAGE 44

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

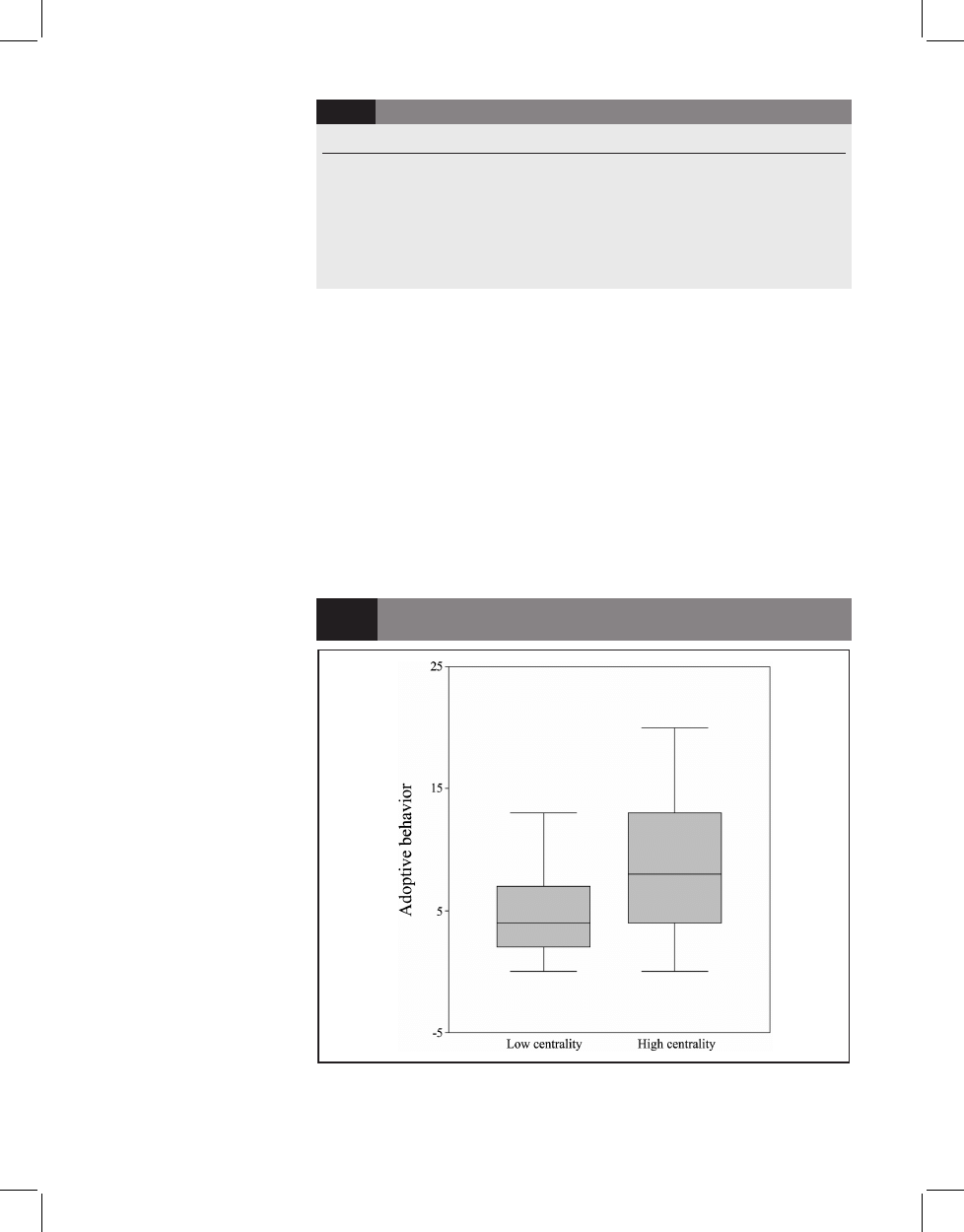

Table III shows the stepwise regression analysis for adoptive behavior. The suitability of the

regression analysis was examined testing for multicollinarity by checking the variable

inflation factor (VIF). These examinations did not reveal any violation for conducting a

multiple regression, since the VIF did not exceed 1.68.

The base model shows that age has a positive statistically significant relation to the adoptive

behavior of a child. This base model including the two control variables explains 6,6 percent

of the variance in the adoptive behavior of children. In the second step degree centrality is

included in the regression analysis. This improves the model’s fit, since degree centrality

explains 14.0 percent of the variance in adoptive behavior. When betweenness centrality is

included in the regression analysis (model 2) the explained variance rises to 17.2 percent.

Looking at the coefficients of both centrality variables, it follows that degree centrality and

betweenness centrality relate to adoptive behavior in a significant positive way. Figure 2

shows a boxplot, in which the differences in the adoptive behavior of children with varying

centralities becomes more visible. In the boxplot the two centrality measures are converted

into one centrality measure.

Figure 2 Boxplot that shows the relation between centrality and adoptive behavior of a

child

Table III Regression analysis for adoptive behavior (

H1a and H1b)

Variables

Base model

Model 1

Model 2

Constant

2

12.905

6.558

2

4.373

2.691

2

2.505

2.751

Gender

2

1.449

1.431

2

1.644

1.365

2

1.353

1.345

Age

2.078**

0.654

0.858

0.701

0.973

0.689

Degree centrality

0.297**

0.063

0.224**

0.069

Betweenness centrality

0.075*

0.031

Adjusted R

2

0.066

0.140

0.172

D

R

2

0.074**

0.147**

0.038*

Notes: * Significance at 0.05; ** Significance at 0.01

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

PAGE 45

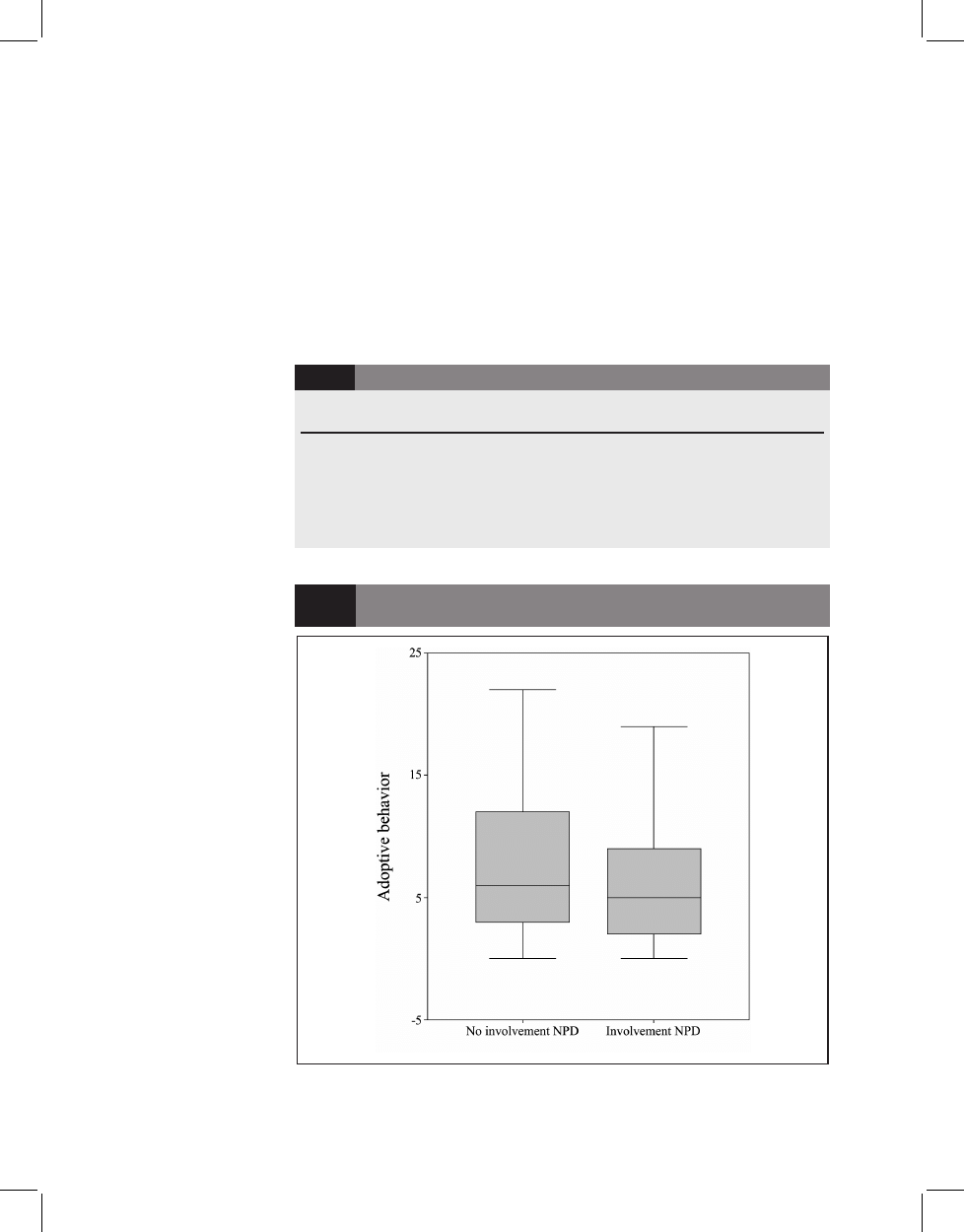

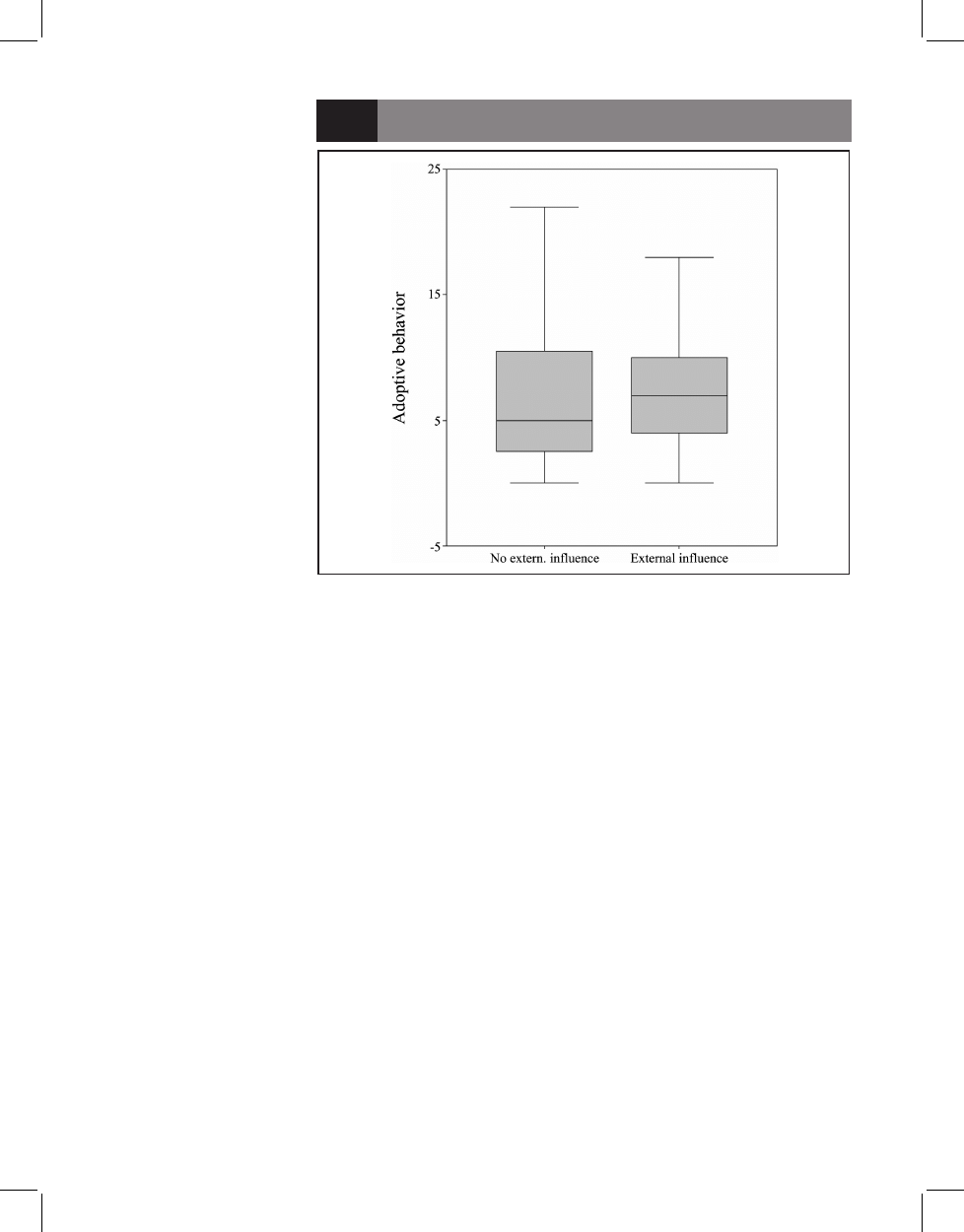

To test H2 and H3 another regression analysis for adoptive behavior was conducted. The

regression analysis started with the same base model, presented in Table III. As pointed out

before the base model explains 6.6 percent of the variance in adoptive behavior. However,

the stepwise regression analysis showed that the explained variance in adoptive behavior

did not improved when the independent variables degree of external influence, degree of

involvement and satisfaction were included in the model. This suggests that none of these

variables relate in a significant way to adoptive behavior. The correlation analysis in Table II

supports this idea, since the table shows no significant correlations between the three

independent variables and adoptive behavior.

However, to draw proper conclusions about the hypotheses, we conducted an independent

samples t test for H2 and H3. The results of these analyses are presented in Table IV. The

table shows that both the degree of external influence and the degree of involvement did not

cause for significant differences in the average adoptive behavior. These results confirm the

previous findings. Figures 3 and 4 show the boxplots that visualize these outcomes.

Table IV Independent samples

t-test for H2 and H3

Adoptive behavior

Variables

Mean

SD

t

df

Sig.

Degree of external influence

High (n

¼ 42)

8.71

10.63

2

0.87

127

0.386

Low (n

¼ 87)

7.37

6.81

Degree of involvement

High (n

¼ 48)

7.10

7.81

0.744

127

0.458

Low (n

¼ 81)

8.22

8.48

Figure 3 Boxplot that shows the relation between the degree of involvement into NPD and

adoptive behavior of a child

PAGE 46

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

Discussion of the results

The way the results are presented, one could say there has been made a distinction between

the hypotheses in part one. H1a and H1b deal explicitly with the role of social networks on

the adoptive behavior of a child, these hypotheses are based on cohesion theories which

emphasize the role of weak ties (Granovetter, 1973; Burt, 1987) and strong ties (Coleman

et al., 1966) in the diffusion of innovations. The remaining hypotheses (H2 and H3) relate to

innovation diffusion (adoptive behavior) in a different way. The variables used in these latter

hypotheses are presumed to impact the thresholds of children, and therefore impact their

adoptive behavior. Hence, these hypotheses were based on threshold theories that point out

that innovation diffusion depends on the varying thresholds of actors (Rogers, 1983).

The results presented in Table III confirm H1a and H1b. The base model showed that age

was significant related to adoptive behavior in a positive way. However with stepwise

regression degree centrality and betweenness centrality were brought in, which significantly

improved the model’s fit (model 1 and model 2). This result implies that the central position of

a child impacts the adoptive behavior of a child, and this central position is better at

predicting the adoptive behavior of a child than is the age of a child. Table III shows that

degree centrality, with 14 percent causes for the greatest explained variance in adoptive

behavior. Betweenness centrality causes for the additional, but much smaller 3.2 percent of

explained variance in adoptive behavior. It follows, that these findings support the cohesion

theories. Especially those who emphasize the important role of strong ties (Coleman et al.,

1966) in the diffusion of innovations, since the results show the higher the degree centrality of

children (a way of measuring strong ties) the higher their adoptive behavior. The weaker

relation between betweenness centrality and adoptive behavior suggests that weak ties play

a smaller role in the diffusion of innovations among children than strong ties do.

Becker (1970) found that when an innovation is relatively safe and uncontroversial, central

figures (strong ties) are the first to adopt an innovation, otherwise the weak ties (high

Figure 4 Boxplot that shows the relation between the degree of external influence and

adoptive behavior of a child

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

PAGE 47

betweenness centrality) would lead in its adoption. Since Kijkradio is a free online

application, the innovation is very safe and uncontroversial. This could explain why degree

centrality seems to impact the adoptive behavior of a child in a stronger way than

betweenness centrality does.

In addition to previous results, the correlation analysis presented in Table II shows that

degree centrality is statistically significant related to the age of a child in a rather positive way

(0.271). This indicates that as children grow older their social networks tend become more

concentrated, in the sense that older children seem to have more ties than younger children

have. This result corresponds with the social cognitive development theory and theories

about friendships development of children, which point out that as children grow older they

feel the need to have more steady friendships and they want belong to a group (Craig and

Baucum, 2003). Nevertheless, although the relation between age and degree centrality is

significant, it is also a small one. So the implications should be interpreted with caution.

The regression analysis for H2 and H3 showed that the explained variance of adoptive

behavior did not improved by the inclusion of the independent variables degree of external

influence, degree of involvement and satisfaction with Kijkradio. This result was confirmed

again, since the independent samples t test for H2 and H3 (Table IV) show that there is no

statistical evidence to prove that degree of external influence and degree of involvement

lead to significant stronger adoptive behavior. The results thus disconfirm both H2 and H3.

The rejection of H2 implies that the use of mass media does not influence the adoptive

behavior of a child in a significant way and hence does not support the Bass model (Mahajan

et al., 1990). Taking into account the confirmation of H1a and H1b and the disconfirmation of

H2, the results confirm theories who claim that internal effects (word of mouth

communication within and between social networks) are the driving force of innovation

diffusion, because it exceeds the influence of external marketing efforts such as advertising

(Goldenberg et al., 2001; Rogers, 1995).

The disconfirmation H3 indicates that the degree of involvement is not statistically significant

related to the adoptive behavior of a child. The involved children were expected to feel more

empowered, therefore more committed to Kijkradio, which should result in stronger adoptive

behavior. Instead the correlation analysis in Table II and the regression analysis shows a

(very small) negative relation between the involvement of children into the NPD process and

the adoptive behavior (2 0.066). However this negative relation is not statistically significant,

and thus the results imply there is no relation between the two variables at all. Therefore the

arguments of McKenna (1995) and Brown et al. (2005) are not supported, it follows that the

involvement of children with the NPD process does not lead to a stronger adoptive behavior.

All in all, the results show that the most important factors affecting the diffusion of innovations

among children are the centrality variables, and thus the centrality of children in their social

networks. In practice this means that more traditional marketing strategies to affect an

actor’s threshold, such as the use of mass media, do not seem to have major impact on the

adoptive behavior of children. Although research on these more traditional marketing

strategies might be valuable for marketers as well, the results of this study suggest that more

research is needed in the field social networks of children since these seem to play a more

important role in the diffusion of innovations. Beside that it is argued that innovation diffusion

through social networks is more effective (Brown and Reingen, 1987; Goldenberg et al.,

2001; Rogers, 1995), it is cheaper than most traditional marketing approaches as well.

Limitations and suggestions for further research

There are some limitations of this study. First of all, the examination of social networks of

children in this study, which is done within school classes. School classes can be used easily

to analyze social relationships between children (Defares et al., 1971). However some

children have social relationships with children outside their school class. Hence, further

examination of these social networks could provide additional insights about the way social

networks of children are related to their adoptive behavior. Furthermore the sample size was

not very high (n

¼ 129). The children with the age of eight till 12 are in the same cognitive

PAGE 48

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

development stage (Piaget, 1971), which makes the population more homogeneous and

thus it is presumable that children of these ages will approximately answer questions

equally. Nevertheless, the larger the sample size the better (with a higher confidence) the

findings in the sample will correspond the findings in the population.

Finally to examine the adoptive behavior of children we used a safe and uncontroversial

innovation, namely Kijkradio, which is a free and online application. As we mentioned in the

discussion of the results, it is not likely that the properties of this innovation can be isolated

from the adoptive behavior of a child. Therefore the results of this study could have been

different, if we had used a more risky and controversial innovation. Further research should

prove or disprove this argument. Besides there are not many studies that attempt to

investigate social networks of children in relation to adoptive behavior and innovation

diffusion among children. In this sense the current study is exploratory and further

examination is desirable, even more since the social networks of children seem to play a

major role in the adoptive behavior of a child.

References

Baarda, D.B. and De Goede, M.P.M. (2001), Basisboek Methoden en Technieken, Wolters-Noordhoff,

Groningen/Houten.

Baptista, R. (2000), ‘‘Do innovations diffuse foster within geographical clusters?’’, International Journal

of Industrial Organizations, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 515-35.

Bass, F.M. (1969), ‘‘A new product growth model for consumer durables’’, Management Science, Vol. 15

No. 5, pp. 215-27.

Becker, M. (1970), ‘‘Sociometric location and innovativeness’’, American Sociological Review, Vol. 35,

April, pp. 267-82.

Berman, R. (1977), ‘‘Preschool knowledge of language: what five year olds know about language

structure and language use’’, in Pontecorvo, C. (Ed.), Writing Development: An Interdisciplinary View,

John Benjamin Publishing, Amsterdam, pp. 61-76.

Borgatti, S.P. (1995), ‘‘Centrality and AIDS’’, Connections, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 112-5.

Borgatti, S.P., Everett, M.G. and Freeman, L.C. (2002), Ucinet 6 for Windows, Analytic Technologies,

Needham, MA.

Brockhoff, K. (1998), ‘‘Technology management as part of strategic planning – some empirical results’’,

R&D Management, Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 129-38.

Brown, J. and Reingen, P.H. (1987), ‘‘Social ties and word-of-mouth referral behavior’’, Journal of

Consumer Research, Vol. 14, pp. 350-62.

Brown, T.J., Barry, T.E., Dacin, P.A. and Gunst, R.F. (2005), ‘‘Spreading the word: investigating

antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context’’,

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 33 No. 2, pp. 123-38.

Burt, R.S. (1987), ‘‘Social contagion and innovation: cohesion versus structural equivalence’’, American

Journal of Sociology, Vol. 92 No. 6, pp. 1287-335.

Case, A.C. (1991), ‘‘Spatial patterns in household demand’’, Econometrica, Vol. 59 No. 4, pp. 953-65.

Chesbrough, H.W. (2003), ‘‘The era of open innovation’’, MIT Sloan Management Review, Vol. 44 No. 3,

pp. 35-41.

Craig, G.J. and Baucum, D. (2003), Human Development, 9th ed., Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River,

NJ.

Coleman, J.S., Katz, E. and Menzel, H. (1966), Medical Innovation: A Diffusion Study, Bobbs Merrill,

New York, NY.

Cooper, R.G. (1979), ‘‘Identifying industrial new product success: project new-prod’’, Industrial

Marketing Management, Vol. 8, May, pp. 124-35.

Czepiel, J.A. (1976), ‘‘Word-of-mouth processes in the diffusion of a major technological innovation’’,

Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 11, May, pp. 172-80.

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

PAGE 49

Defares, P.B., Kema, G.N., Van Praag, E. and Van der Werf, J.J. (1971), Syracuse-Amsterdam-

Groningen Sociometrische Schaal, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen: Subfaculteit der Pedagogische en

Andragogische Wetenschappen, Groningen.

Del Vecchio, G, (2002), Creating Ever-Cool: A Marketer’s Guide to a Kid’s Heart, 3rd ed., Pelican,

Gretna, LA.

Druin, A. (1999), ‘‘Cooperative inquiry: developing new technologies for children with children’’,

Proceedings of the ACM CHI 99 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, May, pp. 592-9.

Druin, A. (2002), ‘‘The role of children in the design of new technology’’, Behaviour & Information

Technology, Vol. 21 No. 1, pp. 1-25.

Freeman, L.C. (1979), ‘‘Centrality in social networks: conceptual clarification’’, Social Networks, Vol. 1,

pp. 215-39.

Garber, T., Goldenberg, J., Libai, B. and Muller, E. (2004), ‘‘From desity to density: using spatial

dimension of sales data for early prediction of new product success’’, Marketing Science, Vol. 23 No. 3,

pp. 419-28.

Goldenberg, J., Libai, B. and Muller, E. (2001), ‘‘Talk of the network: a complex system look at the

underlying process of word of mouth’’, Marketing Letters, Vol. 12, pp. 209-21.

Granovetter, M. (1973), ‘‘The strength of weak ties’’, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 78 No. 6,

pp. 1360-80.

Granovetter, M. (1978), ‘‘Threshold models of collective behaviour’’, American Journal of Sociology,

Vol. 83 No. 6, pp. 1420-43.

Hansen, F. and Hansen, H. (2005), ‘‘Children as innovators and opinion leaders’’, Young Consumers,

January, pp. 44-59.

Kalmijn, M. (2003), ‘‘Shared friendship networks and the life course: an analysis of survey data on

married and cohabiting couples’’, Social Networks, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 231-49.

Larsen, G.D. and Ballal, T.M.A. (2005), ‘‘The diffusion of innovations within a UKCI context:

an explanatory framework’’, Construction Management and Economics, Vol. 23, January, pp. 81-91.

Liu, W.T. and Duff, R.W. (1972), ‘‘The strength of weak ties’’, Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 36, Fall,

pp. 361-6.

McKenna, R. (1995), ‘‘Real-Time marketing’’, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 73 No. 4, pp. 87-95.

McNeal, J. (1992), Kids as Consumers, Lexington, New York, NY.

Mahajan, V., Muller, E. and Bass, F.M. (1990), ‘‘New product diffusion models in marketing: a review and

directions for research’’, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54 No. 1, pp. 1-26.

Menzel, H. (1960), ‘‘Innovation, integration and marginality: a survey of physicians’’, American

Sociological Review, Vol. 25 No. 5, pp. 704-13.

Piaget, J. (1971), Psychology and Epistemology: Towards a Theory of Knowledge, Viking Press,

New York, NY.

Procter, J. and Richards, M. (2002), ‘‘Word-of-mouth marketing: beyond pester power’’, International

Journal of Advertising & Marketing to Children, April/June, pp. 3-11.

Roedder, D. (1999), ‘‘Consumer socialization of children’’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 26,

December, pp. 183-213.

Rogers, E.M. (1962), Diffusion of Innovations, The Free Press, New York, NY.

Rogers, E.M. (1976), ‘‘New product adoption and diffusion’’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 2 No. 3,

pp. 290-301.

Rogers, E.M. (1983), Diffusion of Innovations, 3rd ed., The Free Press, New York, NY.

Rogers, E.M. (1995), Diffusion of Innovations, 4th ed., The Free Press, New York, NY.

Sheth, J.N. (1971), ‘‘Word-of-mouth in low-risk innovations’’, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 11

No. 3, pp. 15-18.

PAGE 50

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

Valente, T.W. (1996), ‘‘Social network thresholds in the diffusion of innovations’’, Social Networks, Vol. 18,

pp. 69-86.

Van der Werf, P. (1990), ‘‘Product tying and innovation in US wire preparation equipment’’, Research

Policy, Vol. 19 No. 1, pp. 83-96.

Von Hippel, E. (1976), ‘‘The dominant role of users in the scientific instrument innovation process’’,

Research Policy, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 212-39.

Von Hippel, E. (1986), ‘‘Lead-users: a source of novel product concepts’’, Management Science, Vol. 32

No. 7, pp. 791-805.

Von Hippel, E. (2001), ‘‘Perspective: user toolkits for innovation’’, Journal of Product Innovation

Management, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 247-57.

Von Hippel, E. and Katz, R. (2002), ‘‘Shifting innovation to users via toolkits’’, Management Science,

Vol. 48 No. 7, pp. 821-34.

Ward, S. (1974), ‘‘Consumer socialization’’, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 1, September, pp. 1-14.

Wasserman, S. and Faust, K. (1994), Social Network Analysis, Cambridge University Press, New York,

NY.

Weimann, G. (1982), ‘‘On the importance of marginality: one more step into the two-step flow of

communication’’, American Sociological Review, Vol. 47 No. 6, pp. 764-73.

Wejnert, B. (2002), ‘‘Integrating models of diffusion of innovations: a conceptual framework’’, Annual

Review of Sociology, Vol. 28, pp. 297-326.

Further reading

Crawford, C.M. (1994), New Products Management, Irwin, Burr Ridge IL.

About the authors

Laurien Kunst is Research Assistant at the Faculty of Management and Organization at the

University of Groningen, The Netherlands. Her main research interests concern human

networks in new product development processes. Laurien Kunst is the corresponding

author and can be contacted at: L.Kunst@rug.nl

Jan Kratzer is Assistant Professor at the Faculty for Management and Organization at the

University of Groningen, The Netherlands. His main research interests concern human

factors and human networks in new product development processes.

VOL. 8 NO. 1 2007

j

YOUNG CONSUMERS

j

PAGE 51

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com

Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

Wyszukiwarka

Podobne podstrony:

examining information behavior through social networks

THE IMPACT OF SOCIAL NETWORK SITES ON INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION

The effects of social network structure on enterprise system success

social networks and planned organizational change the impact of strong network ties on effective cha

Kaasa A Effects of different dimensions of social capital on innovation

the state of organizational social network research today

van leare heene Social networks as a source of competitive advantage for the firm

Grosser et al A social network analysis of positive and negative gossip

social networks and the performance of individualns and groups

Harrison C White Status Differentiation and the Cohesion of Social Network(1)

Petkov ON THE POSSIBILITY OF A PROPULSION DRIVE CREATION THROUGH A LOCAL MANIPULATION OF SPACETIME

A social network perspective on organizational psychology

Adaptive learning networks developing resource management knowledge through social learning forums

8 Advantages and Disadvantages of Social Networking

A social network perspective on industrial organizational psychology

The impact of network structure on knowledge transfer an aplication of

Harrison C White A Model of Robust Positions in Social Networks

social networks and the performance of individuals and groups

więcej podobnych podstron